Recent from talks

Contribute something

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Travel visa

View on Wikipedia

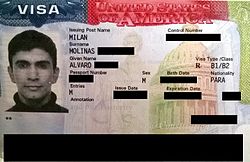

A travel visa (from Latin charta visa 'paper that has been seen';[1] also known as visa stamp) is a conditional authorization granted by a polity to a foreigner that allows them to enter, remain within, or leave its territory. Visas typically include limits on the duration of the foreigner's stay, areas within the country they may enter, the dates they may enter, the number of permitted visits, or if the individual can work in the country in question. Visas are associated with the request for permission to enter a territory and thus are, in most countries, distinct from actual formal permission for an alien to enter and remain in the country. In each instance, a visa is subject to border control at the time of actual entry and can be revoked at any time. Visa evidence most commonly takes the form of a sticker endorsed in the applicant's passport or other travel document but may also exist electronically. Some countries no longer issue physical visa evidence, instead recording details only in border security databases.

Some countries require that their citizens, and sometimes foreign travelers, obtain an exit visa in order to be allowed to leave the country. Until 2004, foreign students in Russia were issued only an entry visa on being accepted to University there, and had to obtain an exit visa to return home. This policy has since been changed, and foreign students are now issued multiple entry (and exit) visas.

Historically, border security officials were empowered to permit or reject entry of visitors on arrival at the frontiers. If permitted entry, the official would issue a visa, when required, which would be a stamp in a passport. Today, travellers wishing to enter another country must often apply in advance for what is also called a visa, sometimes in person at a consular office, by post, or over the Internet. The modern visa may be a sticker or a stamp in the passport, an electronic record of the authorization, or a separate document which the applicant can print before entering and produce on entry to the visited polity. Some countries do not require visitors to apply for a visa in advance for short visits.

Visa applications in advance of arrival give countries a chance to consider the applicant's circumstances, such as financial security, reason for travel, and details of previous visits to the country. Visitors may also be required to undergo and pass security or health checks upon arrival at the port of entry.

Uniquely, the Norwegian special territory of Svalbard is an entirely visa-free zone under the terms of the Svalbard Treaty. Some countries—such as those in the Schengen Area—have agreements with other countries allowing each other's citizens to travel between them without visas. In 2015, the World Tourism Organization announced that the number of tourists requiring a visa before travelling was at its lowest level ever.[2][3]

History

[edit]The history of passports dates back several centuries, originating from early travel documents used to ensure safe passage across regions. One of the earliest known references to a passport-like document comes from 445 BCE in Persia, where officials were provided letters by the king for safe travel. Similarly, during the Han Dynasty in China, documents were required at checkpoints to verify travelers' identities. In medieval Europe, rulers issued "safe conduct" letters that protected travelers. In 1414, during the reign of King Henry V of England, passports became more formalized, allowing foreigners and citizens to travel safely within England. The 19th century saw an increase in international travel due to the Industrial Revolution, which led to the widespread adoption of passports, particularly for managing the movement of migrant workers.

In Western Europe in the late 19th century and early 20th century, passports and visas were not generally necessary for moving from one country to another. The relatively high speed and large movements of people travelling by train would have caused bottlenecks if regular passport controls had been used.[4]

After World War I, passports and visas became essential for international travel.[5] The League of Nations convened conferences in the 1920s to standardise passports, setting the foundation for modern versions. The International Civil Aviation Organization (ICAO) took over regulation in 1947, leading to machine-readable passports and, eventually, biometric passports in the late 20th century, offering enhanced security and speed in processing travelers.[6][7][8]

Issuing authorities

[edit]

Some visas can be granted on arrival or by prior application at the country's embassy or consulate, or through a private visa service specialist who is specialized in the issuance of international travel documents. These agencies are authorized by the foreign authority, embassy, or consulate to represent international travellers who are unable or unwilling to travel to the embassy and apply in person. Private visa and passport services collect an additional fee for verifying customer applications, supporting documents, and submitting them to the appropriate authority. If there is no embassy or consulate in one's home country, then one would have to travel to a third country (or apply by post) and try to get a visa issued there. Alternatively, in such cases visas may be pre-arranged for collection on arrival at the border. The need or absence of need of a visa generally depends on the citizenship of the applicant, the intended duration of the stay, and the activities that the applicant may wish to undertake in the country he or she visits; these may delineate different formal categories of visas, with different issue conditions.

The issuing authority, usually a branch of the country's interior ministry or foreign ministry, or a subordinated agency (Population and Immigration Authority in Israel), and typically consular affairs officers, may request appropriate documentation from the applicant. This may include proof that the applicant has enough money to be self-supporting (or to establish themselves, if the visa is for a long stay or permanent residence), proof that the person or hotel hosting the applicant in his or her home really exists and has sufficient room for hosting the applicant, proof that the applicant has obtained health and evacuation insurance, etc. Some countries ask for proof of health status, especially for long-term visas; some countries deny such visas to persons with certain illnesses, such as HIV/AIDS. The exact conditions depend on the country and category of visa. Notable examples of countries requiring HIV tests of long-term residents are Russia[9] and Uzbekistan.[10] In Uzbekistan, however, the HIV test requirement is sometimes not strictly enforced.[10] Other countries require a medical test that includes an HIV test, even for a short-term tourism visa. For example, Cuban citizens and international exchange students require such a test approved by a medical authority to enter Chilean territory.[citation needed]

The issuing authority may also require applicants to attest that they have no criminal convictions, or that they do not participate in certain activities (like prostitution or drug trafficking). Some countries will deny visas if passports show evidence of citizenship of, or travel to, a country that is considered hostile by that country. For example, some Arabic-oriented countries will not issue visas to nationals of Israel and those whose passports bear evidence of visiting Israel.[citation needed]

Many countries frequently demand strong evidence of intent to return to the home country, if the visa is for a temporary stay, due to potential unwanted illegal immigration. Proof of ties to the visa applicant's country of residence is often demanded to demonstrate a sufficient incentive to return. This can include things such as documented evidence of employment, bank statements, property ownership, and family ties.[citation needed]

Visa politics

[edit]The main reasons states impose visa restrictions on foreign nationals are to curb illegal immigration, security concerns, and reciprocity for visa restrictions imposed on their own nationals. Typically, nations impose visa restrictions on citizens of poorer countries, along with politically unstable and undemocratic ones, as it is considered more likely that people from these countries will seek to illegally immigrate. Visa restrictions may also be imposed when nationals of another country are perceived as likelier to be terrorists or criminals, or by autocratic regimes that perceive foreign influence to be a threat to their rule.[11][12] According to Professor Eric Neumayer of the London School of Economics:

The poorer, the less democratic, and the more exposed to armed political conflict the target country is, the more likely that visa restrictions are in place against its passport holders. The same is true for countries whose nationals have been major perpetrators of terrorist acts in the past.[11]

The public support on immigration ranges between fully open borders and fully closed borders.[13]

Some countries apply the principle of reciprocity in their visa policy. Visa reciprocity is a principle in international relations where two countries agree to give each other's citizens similar treatment when it comes to visa requirements.[14] For example visa reciprocity is a central principle of the EU's common visa policy. The EU aims to achieve full visa reciprocity with non-EU countries whose citizens can travel to the EU without a visa.[15] For example, when in 2009, Canada reintroduced visa requirements for Czech nationals, arguing it was necessary due to a surge in asylum applications, it raised concerns within the EU about the implications for the common visa policy, the importance of reciprocity in maintaining good relations and ensuring equal treatment for citizens of member states.[16][17]

Some polities which restrict emigration require individuals to possess an exit visa to leave the polity.[18] These exit visas may be required for citizens, foreigners, or both, depending on the policies of the polity concerned. Unlike ordinary visas, exit visas are often seen[by whom?] as an illegitimate intrusion on individuals' right to freedom of movement.[citation needed] The imposition of an exit visa requirement may be seen to violate customary international law, as the right to leave any country is provided for in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights.[citation needed]

Visa policies

[edit]Government authorities usually impose administrative entry restrictions on foreign citizens in three ways – countries whose nationals may enter without a visa, countries whose nationals may obtain a visa on arrival, and countries whose nationals require a visa in advance. Nationals who require a visa in advance are usually advised to obtain them at a diplomatic mission of their destination country. Several countries allow nationals of countries that require a visa to obtain them online.[citation needed]

The following table lists visa policies of all countries by the number of foreign nationalities that may enter that country for tourism without a visa or by obtaining a visa on arrival with normal passport. It also notes countries that issue electronic visas to certain nationalities. Symbol "+" indicates a country that limits the visa-free regime negatively by only listing nationals who require a visa, thus the number represents the number of UN member states reduced by the number of nationals who require a visa and "+" stands for all possible non-UN member state nationals that might also not require a visa. "N/A" indicates countries that have contradictory information on its official websites or information supplied by the government to IATA. Some countries that allow visa on arrival do so only at a limited number of entry points. Some countries such as the European Union member states have a qualitatively different visa regime between each other as it also includes freedom of movement.[citation needed]

The following table is current as of 3 October 2019[update]. Source:[19]

| Country | Total (excl. electronic visas) |

Visa-free | Visa on arrival | Electronic visas | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | |||||

| 88 | 88 | ||||

| 7 | 7 | ||||

| 71 | 10 | 61 | |||

| 106 | 106 | All | |||

| 90 | 89+1 | ||||

| 129 | 66 | 63 | |||

| 1 | 1 | 0 | All-1 | ||

| 25 | 11+1 | 13 | 95 | ||

| 120 | 120 | ||||

| 73 | 5 | 68 | 120+ | ||

| 173+ | 23 | All-23-25 | 33[20][21] | Limited VOA locations. | |

| 180 | 180 | ||||

| 92 | 28+64 | ||||

| 107 | 107 | ||||

| 194+ | 59 | All others | |||

| 3 | 3 | ||||

| 176+ | 54 | All-54-22 | |||

| 102 | 102 | ||||

| 103 | 103 | ||||

| 102 | 101+1 | 3 | |||

| 63 | 56 | 7 | |||

| 70 | 19 | 51 | |||

| 6 | 6 | ||||

| 194+ | 10 | All others | All-10 | ||

| 6 | 6 | ||||

| 54 | 54 | ||||

| 194+ | 61 | All others | |||

| 17 | 17 | ||||

| 15 | 14 | 1 | |||

| 92 | 92 | ||||

| 21 | 21 | ||||

| 99 | 98+1 | ||||

| 194+ | 0 | All | |||

| 15 | 5 | 10 | |||

| 7 | 4 | 3 | |||

| 96 | 96 | ||||

| 194+ | 24 | All-24 | |||

| 19 | 19 | ||||

| 194+ | 1 | All-1 | |||

| 193+ | All-2 | ||||

| 108 | 108 | ||||

| 164+ | All-34 | ||||

| 194+ | 8 | All-81 | 78 | ||

| 87 | 87 | ||||

| 10 | 10 | ||||

| 3 | 1 | 2 | |||

| 94 | 94 | ||||

| 94 | 2 | 92 | All-2 | Limited VOA locations. | |

| 110 | 110 | ||||

| 59 | 11 | 48 | All | ||

| 114 | 113 | 1 | |||

| 94 | 94 | 62 | |||

| 58 | 30 | 28 | |||

| 119 | 108 | 11 | |||

| 86 | 86 | ||||

| 22 | 22 | ||||

| 194+ | 14 | All-14 | All-14 | ||

| 59 | 57 | 2 | |||

| 188+ | All-10 | ||||

| 85 | 85 | ||||

| 148 | 148 | ||||

| 6 | 3 | 3 | 156 | Limited e-Tourist Visa locations. | |

| 86 | 9 | 77 | |||

| 183+ | 16 | All-16 | |||

| 44 | 0 | 7+37 | |||

| 89+ | 89+ | +31 EU/EEA/CH citizens. | |||

| 101 | 101 | ||||

| 132 | 101+5 | 25+1 | |||

| 68 | 68 | ||||

| 139 | 12 | 127 | Limited VOA locations. | ||

| 76 | 76 | ||||

| 43 | 43 | 0 | All-12 | ||

| 73 | 73 | ||||

| 0 | |||||

| 112 | 110+2 | ||||

| 58 | 5 | 53 | 53 | ||

| 82 | 78 | 4 | All | ||

| 194+ | 15 | All-32 | |||

| 103 | 7 | 80+16 | |||

| 70 | 70 | All | |||

| 14 | 14 | ||||

| 7 | 7 | 2 countries are Conditional visa-free access | |||

| 194+ | 83 | All-6 | |||

| 84 | 84 | ||||

| 194+ | 0 | All | All | ||

| 194+ | 33 | All-33-48 | |||

| 162 | 162 | 10 | |||

| 194+ | 3 | All-3 | |||

| 25 | 25 | ||||

| 96 | 32 | 63+1 | |||

| 194+ | 8 | All-8 | |||

| 194+ | 114 | All-17 | |||

| 65 | 65 | 3 | |||

| 194+ | All | ||||

| 104 | 104 | ||||

| 64 | 27+1 | 36 | 36 | ||

| 97 | 96+1 | ||||

| 72 | 72 | 5 | |||

| 194+ | 11 | All-11 | Limited VOA locations. | ||

| 21 | 8 | 13 | 102 | ||

| 98 | 55 | 42+1 | |||

| 16 | 0 | 14+2 | |||

| 186+ | 1 | 185+ | Limited VOA locations. | ||

| 1 | 0 | 0 | 60 | ||

| 165 | 90+1 | 74 | |||

| 19 | 19 | ||||

| 18 | 17 | 1 | |||

| 103 | 102+1 | 72 | |||

| 5 | 5 | All-4 | |||

| 194+ | 36 | All-36 | |||

| 118 | 118 | ||||

| 71 | 0 | 71 | 71+25 | ||

| 67 | 65 | 2 | |||

| 100 | 100 | ||||

| 160 | 160 | ||||

| 92 | 89 | 3 | All-3 | Limited VOA locations. | |

| 66 | 63+3 | ||||

| 194+ | 24 | All-24 | All | ||

| 125 | 125 | All | |||

| 160 | 96+14 | 50 | |||

| 191+ | All-9 | ||||

| 194+ | All | ||||

| 59 | 56 | 3 | All | ||

| 5 | 5 | 52 | |||

| 93 | 62+31 | 31 EU/EEA/CH citizens. | |||

| 194+ | 61 | All-4 | |||

| 93 | 93 | ||||

| 195+ | 33 | All-33-1 | |||

| 137 | 14 | 123 | |||

| 162+ | 162+ | ||||

| 74 | 32 | 42 | |||

| 194+ | Limited VOA locations. | ||||

| 83 | 83 | 14 | |||

| 4 | 4 | ||||

| 194+ | 0 | 3 | All-3-20 | ||

| 8 | 4+1 | 3 | |||

| 80 | 24+7 | 49 | |||

| 0 | |||||

| 87 | 62 | 25 | 120 | ||

| 169+ | 46+23 | All-69-29 | |||

| 83 | 65 | 18 | |||

| 194+ | 33 | All-33 | Limited VOA locations. | ||

| 194+ | 15 | All-15 | |||

| 69 | 33 | 36 | |||

| 103 | 100 | 3 | |||

| 95 | 95 | +11 for organised groups. | |||

| 91 | 90+1 | 29 | e-Visas can also be obtained on arrival for a higher cost. | ||

| 0 | |||||

| 194+ | 31 | All-31 | |||

| 194+ | 36 | All-36 | All | ||

| 82 | 82 | 45 | |||

| 81 | 81 | ||||

| 89 | 89 | 6 | +31 EU/EEA/CH citizens. | ||

| 45 | 40+5 | ||||

| 85 | 84+1 | ||||

| 93 | 93 | 51 | |||

| 121 | 121 | ||||

| 70 | 70 | ||||

| 25 | 25 | 81 | |||

| 12 | 1 | 11 | |||

| 160+ | 83+16 | 61 | All | ||

| 149+ | 41+4 | 102+2 | All |

Visa exemption agreements

[edit]Possession of a valid visa is a condition for entry into most countries. However, bilateral exemption schemes exist that permit free movement between participating states and addition many states permit visa-free entry – known as a visa waiver – for short-term tourist visits.

Some countries have reciprocal agreements such that a visa is not needed under certain conditions, e.g., when the visit is for tourism and for a relatively short period. Such reciprocal agreements may stem from common membership in international organizations or a shared heritage:

- All citizens of European Union (EU) and EFTA member countries can travel to and stay in all other EU and EFTA countries without a visa. See Four Freedoms (European Union) and Citizenship of the European Union.

- British and Irish citizens are entitled the right to travel to and live in each other's countries without visas or restrictions under the Common Travel Area (CTA). Citizens of territories in the CTA do not need visas to travel to and stay in other countries in the CTA.

- The United States Visa Waiver Program allows citizens of 41 countries to travel to the United States without a visa (although a pre-trip entry permission, ESTA, is needed).[25]

- Citizens of Canada and the United States do not require a visa to travel between the two countries. Historically, verbal declaration of citizenship, or, if requested by an officer, the presentation of one of over 8,000 different types of documents indicating US or Canadian citizenship was sufficient in order to cross the border.[26] Since the Western Hemisphere Travel Initiative came into effect in 2009, a passport, border crossing card, or enhanced driver's license is now required in order to enter the US from Canada by land, or a passport by air.

- Any Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) citizen can enter and stay as long as required in any other GCC member state.

- All citizens of members of the Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS), excluding those defined by law as undesirable aliens, may enter and stay without a visa in any member state for a maximum period of 90 days. The only requirement is a valid travel document and international vaccination certificates.[27]

- Nationals of the East African Community member states do not need visas for entry into any of the member states.[28][29][30]

- Some countries in the Commonwealth do not require tourist visas of citizens of other Commonwealth countries.

- Citizens of member states of the Association of Southeast Asian Nations do not require tourist visas to visit another member state, with the exception of Malaysia and Myanmar; both countries require citizens of the other country to have an eVisa to visit. Until 2009, Burmese citizens were required to have visas to enter all other ASEAN countries. Following the implementation of visa exemption agreements with the other ASEAN countries, in 2016 Burmese citizens are only required to have visas to enter Malaysia.

- Commonwealth of Independent States (CIS) member states mutually allow their citizens to enter visa-free, at least for short stays. There are exceptions between Tajikistan and Uzbekistan, and between Armenia and Azerbaijan.

- Nepal and India allow their citizens to enter, live, and work in each other's countries due to the Indo-Nepal friendship treaty of 1951. Indians do not require a visa or passport to travel to Bhutan and are only required to obtain passes at the border checkpoints, whilst Bhutan nationals holding a valid Bhutanese passport are authorized to enter India without a visa.

- Citizens of Mercosur full member and associate countries can enter without a visa in any of the member and associate countries, just needing to present the ID card.[31][32]

In some cases visa-free entry may be granted to holders of diplomatic passports even as visas are required by normal passport holders (see: Passport).

Other countries may unilaterally grant visa-free entry to nationals of certain countries to facilitate tourism, promote business, or even to cut expenses on maintaining consular posts abroad.

Some of the considerations for a country to grant visa-free entry to another country include (but are not limited to):[citation needed]

- being a low security risk for the country potentially granting visa-free entry

- diplomatic relationship between two countries

- conditions in the visitor's home country as compared to the host country

- having a low risk of overstaying or violating visa terms in the country potentially granting visa-free entry

To have a smaller worldwide diplomatic staff, some countries rely on other country's (or countries') judgments when issuing visas. For example, Mexico allows citizens of all countries to enter without Mexican visas if they possess a valid American visa that has already been used. Costa Rica accepts valid visas of Schengen/EU countries, Canada, Japan, South Korea, and the United States (if valid for at least three months on date of arrival). The ultimate example of such reliance is the microstate of Andorra, which imposes no visa requirements of its own because it has no international airport and is inaccessible by land without passing through the territory of either France or Spain and is thus "protected" by the Schengen visa system.

Visa-free travel between countries also occurs in all cases where passports (or passport-replacing documents such as laissez-passer) are not needed for such travel. (For examples of passport-free travel, see International travel without passports.)

As of 2019, the Henley & Partners passport index ranks the Japanese, Singaporean, and South Korean passports as the ones with the most visa exemptions by other nations, allowing holders of those passports to visit 189 countries without obtaining a visa in advance of arrival.[33]

Common area visas

[edit]Normally, visas are valid for entry only into the country that issued the visa. Countries that are members of regional organizations or party to regional agreements may, however, issue visas valid for entry into some or all of the member states of the organization or agreement:

- The Schengen Visa is a visa for the Schengen Area, which consists of most of the European Economic Area, plus several other adjacent countries. The visa allows visitors to stay in the Schengen Area for up to 90 days within a 180-day period[citation needed]. The visa is valid for tourism, family visits, and business.

- The Central American Single Visa (Visa Única Centroamericana) is a visa for Guatemala, El Salvador, Honduras, and Nicaragua. It was implemented by the CA-4 agreement. It allows citizens of those four countries free access to other member countries. It also allows visitors to any member country to enter another member country without having to obtain another visa.

Possible common visa schemes

[edit]Potentially, there are new common visa schemes:

- An ASEAN common visa scheme has been considered with Thailand and the "CLMV" countries of Cambodia, Laos, Myanmar, and Vietnam opting in earlier. After talk arose of a CLMV common visa,[34] with Thailand being omitted, Thailand initiated and began implementation of a trial common visa with Cambodia, but cited security risks as the major hurdle. The trial run was delayed,[35] but Thailand implemented a single visa scheme with Cambodia beginning on 27 December 2012 on a trial basis.[36]

- A Gulf Cooperation Council single visa has been recommended as a study submitted to the council.[37]

- The Pacific Alliance, which currently consists of Chile, Colombia, Mexico, and Peru, offer a common visa for tourism purposes only in order to make it easier for nationals from countries outside of the alliance to travel through these countries by not having to apply for multiple visas.[38]

- An East African Single Tourist Visa is under consideration by the relevant sectoral authorities under the East African Community (EAC) integration program. If approved the visa will be valid for all five partner states in the EAC (Kenya, Tanzania, Uganda, Rwanda, and Burundi). Under the proposal for the visa, any new East African single visa can be issued by any partner state's embassy. The visa proposal followed an appeal by the tourist boards of the partner states for a common visa to accelerate promotion of the region as a single tourist destination and the EAC Secretariat wants it approved before November's World Travel Fair (or World Travel Market) in London.[39] When approved by the East African council of ministers, tourists could apply for one country's entry visa, which would then be applicable in all regional member states as a single entry requirement initiative.[40] This is considered also by COMESA.

- The SADC UNIVISA (or Univisa) has been in development since Southern African Development Community (SADC) members signed a Protocol on the Development of Tourism in 1998. The Protocol outlined the Univisa as an objective so as to enable the international and regional entry and travel of visitors to occur as smoothly as possible.[citation needed] It was expected to become operational by the end of 2002.[41] Its introduction was delayed and a new implementation date, the end of 2006, was announced. The univisa was originally intended to only be available, initially, to visitors from selected "source markets" including Australia, the Benelux countries, France, Germany, Italy, Japan, Portugal, Spain, the United Kingdom, and the United States.[41] It is now expected that when the Univisa is implemented, it will apply to non-SADC international (long-haul) tourists travelling to and within the region and that it will encourage multi – destination travel within the region. It is also anticipated that the Univisa will enlarge tourist market for transfrontier parks by lowering the boundaries between neighbouring countries in the parks. The visa is expected to be valid for all the countries with trans frontier parks (Botswana, Lesotho, Mozambique, Namibia, South Africa, and Zimbabwe) and some other SADC countries (Angola and Swaziland).[42] As of 2017, universal visa is implemented by Zambia and Zimbabwe. Nationals of 65 countries and territories are eligible for visa on arrival that is valid for both countries. This visa is branded KAZA Uni-visa programme after Kavango–Zambezi Transfrontier Conservation Area (KAZA). It is expected that other SADC countries will join the program in the future.[43]

Previous common visa schemes

[edit]These schemes no longer operate.

- The CARICOM Visa was introduced in late 2006 and allowed visitors to travel between 10 CARICOM member states (Antigua & Barbuda, Barbados, Dominica, Grenada, Guyana, Jamaica, St. Kitts & Nevis, St. Lucia, St. Vincent & the Grenadines, and Trinidad and Tobago). These ten member countries had agreed to form a "Single Domestic Space" in which travellers would only have their passport stamped and have to submit completed, standardized entry and departure forms at the first port and country of entry. The CARICOM Visa was applicable to the nationals of all countries except CARICOM member states (other than Haiti) and associate member states, Canada, France, Germany, Ireland, Italy, Japan, the Netherlands, South Africa, the United Kingdom, the United States of America, and the overseas countries, territories, or departments of these countries. The CARICOM Visa could be obtained from the Embassies/Consulates of Barbados, Jamaica, and Trinidad & Tobago and in countries that have no CARICOM representatives, the applications forms could be obtained from the embassies and consulates of the United Kingdom. The common visa was only intended for the duration of the 2007 Cricket World Cup and was discontinued on 15 May 2007. Discussions are ongoing into instituting a revised CARICOM visa on a permanent basis in the future.

- A predecessor of the Schengen common visa was the Benelux visa. Visas issued by Belgium, Netherlands, and Luxembourg were valid for all the three countries.

Entry and duration period

[edit]Visas can also be single-entry, which means the visa is cancelled as soon as the holder enters the country; double-entry; or multiple-entry, which permits double or multiple entries into the country with the same visa. Countries may also issue re-entry permits that allow temporarily leaving the country without invalidating the visa. Even a business visa will normally not allow the holder to work in the host country without an additional work permit.

Once issued, a visa will typically have to be used within a certain period of time.

In some countries, the validity of a visa is not the same as the authorized period of stay. The visa validity then indicates the time period when the entry is permitted into the country. For example, if a visa has been issued to begin on 1 January and to expire on 30 March, and the typical authorized period of stay in a country is 90 days, then the 90-day authorized stay starts on the day the passenger enters the country (entrance has to be between 1 January and 30 March). Thus, the latest day the traveller could conceivably stay in the issuing country is 1 July (if the traveller entered on 30 March). This interpretation of visas is common in the Americas.

With other countries, a person may not stay beyond the period of validity of their visa, which is usually set within the period of validity of their passport. The visa may also limit the total number of days the visitor may spend in the applicable territory within the period of validity. This interpretation of visa periods is common in Europe.

Once in the country, the validity period of a visa or authorized stay can often be extended for a fee at the discretion of immigration authorities. Overstaying a period of authorized stay given by the immigration officers is considered illegal immigration even if the visa validity period is not over (i.e., for multiple entry visas) and a form of being "out of status" and the offender may be fined, prosecuted, deported, or even blacklisted from entering the country again.

Entering a country without a valid visa or visa exemption may result in detention and removal (deportation or exclusion) from the country. Undertaking activities that are not authorized by the status of entry (for example, working while possessing a non-worker tourist status) can result in the individual being deemed liable for deportation—commonly referred to as an illegal alien. Such violation is not a violation of a visa, despite the common misuse of the phrase, but a violation of status – hence the term "out of status".

Even having a visa does not guarantee entry to the host country. The border crossing authorities make the final determination to allow entry, and may even cancel a visa at the border if the alien cannot demonstrate to their satisfaction that they will abide by the status their visa grants them.

Some countries that do not require visas for short stays may require a long-stay visa for those who intend to apply for a residence permit. For example, the EU does not require a visa of citizens of many countries for stays under 90 days, but its member states require a long-stay visa of such citizens for longer stays.

By method of issue

[edit]Normally visa applications are made at and collected from a consulate, embassy, or other diplomatic mission.

On-arrival visas

[edit]

Also known as visas on arrival (VOA), they are granted at a port of entry. This is distinct from visa-free entry, where no visa is required, as the visitor must still obtain the visa on arrival before proceeding to immigration control.

- Almost all countries will consider issuing a visa (or another document to the same effect) on arrival to a visitor arriving in unforeseen exceptional circumstances, for example:

- Under provisions of article 35 of the Schengen Visa Code,[44] a visa may be issued at a border in situations such as the diversion of a flight causing air passengers in transit to pass through two or more airports instead of one. In 2010, Iceland's Eyjafjallajökull volcano erupted, causing significant disruption of air travel throughout Europe, and the EU responded by announcing that it would issue visas at land borders to stranded travellers.

- Under section 212(d)(4) of the Immigration and Naturalization Act,[45] visa waivers can be issued to travellers arriving at American ports of entry in emergency situations or under other conditions.

- Certain international airports in Russia have consuls on-duty, who have the power to issue visas on the spot.

- Some countries issue visas on arrival to special categories of travellers, such as seafarers or aircrew.

- Some countries issue them to regular visitors. There often are restrictions – for example:

Belarus issues visas on arrival in Minsk international airport only to nationals of countries where there is no consular representation of Belarus.

Belarus issues visas on arrival in Minsk international airport only to nationals of countries where there is no consular representation of Belarus. Thailand only issues visas on arrival at certain border checkpoints. The most notable crossing where visas on arrival are not issued is the Padang Besar checkpoint for passenger trains between Malaysia and Thailand. As of May 2025, individuals applying for a tourist visa to Thailand must provide financial evidence of sufficient resources.[46]

Thailand only issues visas on arrival at certain border checkpoints. The most notable crossing where visas on arrival are not issued is the Padang Besar checkpoint for passenger trains between Malaysia and Thailand. As of May 2025, individuals applying for a tourist visa to Thailand must provide financial evidence of sufficient resources.[46]

| Country | Universal eligibility | Electronic visa alternative | Limited ports of entry | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| X | ✓ | X | ||

| X | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| X | ✓ | X | ||

| ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| X | X | X | ||

| X | X | X | ||

| X | X | X | ||

| X | ✓ | X | ||

| ✓ | X | X | ||

| X | X | X | ||

| ✓ | X | X | ||

| X | X | X | ||

| X | X | X | ||

| ✓ | ✓ | X | ||

| X | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| X | X | X | ||

| X | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| X | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| X | X | X | ||

| X | X | X | ||

| X | X | X | ||

| ✓ | ✓ | X | ||

| X | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| X | X | ✓ | [47] | |

| X | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| X | X | ✓ | ||

| X | X | X | ||

| X | X | X | ||

| X | ✓ | X | ||

| X | ✓ | X | ||

| X | X | ✓ | ||

| X | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| X | X | X | ||

| X | X | X | ||

| ✓ | ✓ | X | ||

| X | X | X | ||

| ✓ | X | X | ||

| X | X | X | ||

| ✓ | X | ✓ | ||

| X | X | X | ||

| X | X | ✓ | ||

| ✓ | X | X | ||

| X | X | ✓ | ||

| X | X | X | ||

| ✓ | X | X | ||

| ✓ | X | X | ||

| X | X | X | ||

| X | ✓ | X | ||

| ✓ | X | X | ||

| X | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| X | X | ✓ | ||

| ✓ | ✓ | X | ||

| X | X | X | ||

| ✓ | ✓ | X | ||

| X | ✓ | X | ||

| ✓ | X | X | ||

| X | X | X | ||

| X | X | X | ||

| X | ✓ | X | ||

| X | X | X | ||

| X | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| X | ✓ | X | ||

| X | X | ✓ | ||

| ✓ | X | ✓ | ||

| ✓ | X | X | ||

| X | X | X | ||

| X | X | X | ||

| ✓ | X | X | ||

| ✓ | ✓ | X | ||

| X | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| X | X | X | ||

| X | X | X | ||

| X | ✓ | X | ||

| X | ✓ | X |

Electronic visas

[edit]

An electronic visa (e-Visa or eVisa) is stored in a computer and is linked to the passport number so no label, sticker, or stamp is placed in the passport before travel. The application is done over the internet, and the receipt acts as a visa, which can be printed or stored on a mobile device.

Visa extensions

[edit]Many countries have a mechanism to allow the holder of a visa to apply to extend a visa. In Denmark, a visa holder can apply to the Danish Immigration Service for a Residence Permit after they have arrived in the country. In the United Kingdom, applications can be made to UK Visas and Immigration.

In certain circumstances, it is impossible for the holder of the visa to do this, either because the country does not have a mechanism to prolong visas or, most likely, because the holder of the visa is using a short stay visa to live in a country.

Visa run

[edit]

Some foreign visitors engage in what is known as a visa run: leaving a country—usually to a neighboring country—for a short period just before the permitted length of stay expires, then returning to the first country to get a new entry stamp in order to extend their stay ("reset the clock"). Despite the name, a visa run is usually done with a passport that can be used for entry without a visa.

Visa runs are frowned upon by immigration authorities as they may signify that the foreigner wishes to reside permanently and might also work in that country – purposes that are prohibited and that usually require an immigrant visa or a work visa. Immigration officers may deny re-entry to visitors suspected of engaging in prohibited activities, especially when they have done repeated visa runs and have no evidence of spending reasonable time in their home countries or countries where they have the right to reside and work.

To combat visa runs, some countries have limits on how long visitors can spend in the country without a visa, as well as how much time they have to stay out before "resetting the clock". For example, Schengen countries impose a maximum of 90 days in any 180-day period. Some countries do not "reset the clock" when a visitor comes back after visiting a neighboring country. For example, the United States does not give visitors a new period of stay when they come back from visiting Canada, Mexico, or the Caribbean; instead they are re-admitted to the United States for the remaining days granted on their initial entry.[48]

In some cases, a visa run is necessary to activate new visas or change the immigration status of a person. An example would be leaving a country and then returning immediately to activate a newly issued work visa before a person can legally work.

Exit visas

[edit]Exit visas may be required to leave some countries. Many countries limit the ability of individuals to leave in certain circumstances, such as those with outstanding legal proceedings or large government debts.[49][50][51] Despite this, the term exit visa is generally limited to countries that systematically restrict departure, where the right to leave is not automatic. Imposing a systematic requirement for exit permission may be seen to violate the right to freedom of movement, which is found in the UDHR and forms part of customary international law.[52]

Countries implementing exit visas vary in who they require to obtain one. Some countries permit the free movement of foreign nationals while restricting their own citizens.[53][54] Others may limit the exit visa requirement to resident foreigners in the country on work visas, such as in the kafala system.[55][56][57][58]

Asia

[edit]Iraq, Kuwait, Lebanon, Oman, Saudi Arabia, and the United Arab Emirates all have an exit visa requirement for alien foreign workers. This is part of their kafala work visa sponsorship system. Consequently, at the end of a foreign worker's employment period, the worker must secure clearance from their employer stating that the worker has satisfactorily fulfilled the terms of their employment contract or that the worker's services are no longer needed. The exit visa can also be withheld if there are pending court charges that need to be settled or penalties that have to be meted out. In September 2018, Qatar lifted the exit visa requirement for most workers.[59] Persons are generally free to leave Israel, except for those who are subject to a stay of exit order.[60]

Nepal requires its citizens emigrating to the United States on an H-1B visa to present an exit permit issued by the Nepali Ministry of Labour. This document is called a work permit and needs to be presented to Nepali immigration to leave Nepal.[61]

Uzbekistan was the last remaining country of the former USSR that required an exit visa, which was valid for a two-year period. The practice was abolished in 2019.[62] There had been an explicit United Nations complaint about this practice.[63]

North Korea requires that its citizens obtain an exit visa stating the traveller's destination country and time to be spent abroad before leaving the country.[citation needed] Additionally, North Korean authorities also require North Korean citizens to obtain a re-entry visa from a North Korean embassy or North Korean mission abroad before being allowed back into North Korea.[citation needed]

The government of the People's Republic of China requires its citizens to obtain a Taiwan Travel Permit issued by the People's Republic of China's authorities with a valid endorsement prior to visiting the Republic of China if they depart from the mainland (besides Chongqing, Nanchang or Kunming if they leave for the Republic of China for transit[64]). The endorsement is a de facto exit visa for ROC-bound trips for mainland citizens of China.[65]

Singapore operates an Exit Permit scheme in order to enforce the national service obligations of its male citizens and permanent residents.[66] Requirements vary according to age and status:[67]

| Status | Time overseas | Requirements |

|---|---|---|

| Pre-enlistment: 13 – 16.5 years of age | 3+ months | Exit permit |

| 2+ years | Exit permit + bond | |

| Pre-enlistment: 16.5 years of age and older | 3+ months | Registration, exit permit + bond[68] |

| Full-time National Service | 3+ months | Exit permit |

| Operationally-ready National Service | 14+ days | Overseas notification |

| 6+ months | National service unit approval + exit permit | |

| Regular servicemen | 3+ months | Exit permit, where Minimum Term of Engagement is not complete |

| 6+ months | Exit permit |

Iran, Taiwan[69] and South Korea also require male citizens who are older than a certain age but have not fulfilled their military duties to register with local Military Manpower Administration office before they pursue international travels, studies, business trips, and/or performances. Failure to do so is a felony in those countries and violators would face up to three years of imprisonment.

Europe

[edit]

During the Fascist period in Italy, an exit visa was required from 1922 to 1943. Nazi Germany required exit visas from 1933 to 1945.[70]

The Soviet Union and its Warsaw Pact allies required exit visas both for emigration and for those who wanted to leave the Soviet Union for a shorter period.

Some countries require that an alien who needs a visa on entry be in possession of a valid visa upon exit. To satisfy this formal requirement, exit visas sometimes need to be issued.

Russia requires an exit visa if a visitor stays past the expiration date of their visa. They must then extend their visa or apply for an exit visa and are not allowed to leave the country until they show a valid visa or have a permissible excuse for overstaying their visa (e.g., a note from a doctor or a hospital explaining an illness, missed flight, lost or stolen visa). In some cases, the Ministry of Foreign Affairs can issue a return-Home certificate that is valid for ten days from the embassy of the visitor's native country, thus eliminating the need for an exit visa.

A foreign citizen granted a temporary residence permit in Russia needs a temporary resident visa to take a trip abroad (valid for both exit and return). It is also colloquially called an exit visa. Not all foreign citizens are subject to that requirement. Citizens of Germany, for example, do not require this exit visa.

In March 2021, during the COVID-19 pandemic, the United Kingdom required everyone leaving England to fill out an exit form detailing their address, passport number, destination, and reason to travel.[71] Permitted reasons to travel included for work or volunteering, education, medical or compassionate reasons such as weddings and funerals.[72] Travellers may have been required to carry evidence to support their reason to travel.[73]

Americas

[edit]Cuba dropped its exit visa requirement in January 2013.[74]

Guatemala requires any foreigner who is a permanent resident to apply for a multiple 5-year exit visa.

United States

[edit]The United States of America does not require exit visas. Since 1 October 2007, however, the U.S. government requires all foreign and U.S. nationals departing the United States by air to hold a valid passport (or certain specific passport-replacing documents). Even though travellers might not require a passport to enter a certain country, they will require a valid passport booklet (booklet only, U.S. Passport Card not accepted) to depart the United States in order to satisfy the U.S. immigration authorities.[75] Exemptions to this requirement to hold a valid passport include:

- U.S. Permanent Resident/Resident Alien Card (Form I-551);

- U.S. Military ID Cards when travelling on official orders;

- U.S. Merchant Mariner Card;

- NEXUS Card;

- U.S. travel document:

- Refugee Travel Document (Form I-571); or

- Permit to Re-Enter (Form I-327)

- Emergency Travel Document (e.g. Consular Letter) issued by a foreign embassy or consulate specifically for the purpose of travel to the bearer's home country.

- Nationals of Mexico holding one of the following documents:

- (expired) "Matricula Consular"; or

- Birth certificate with consular registration; or

- Certificate of Nationality issued by a Mexican consulate abroad; or

- Certificate of Military Duty (Cartilla Militar); or

- Voter's Certificate (Credencial IFE or Credencial para Votar).

In addition, green card holders and certain other aliens must obtain a certificate of compliance (also known as a "sailing permit" or "departure permit") from the Internal Revenue Service proving that they are up-to-date with their US income tax obligations before they may leave the country.[76] While the requirement has been in effect since 1921, it has not been stringently enforced, but in 2014 the House Ways and Means Committee considered beginning to enforce the requirement as a way to increase tax revenues.[77]

Australia

[edit]Australia, citing COVID-19 concerns, in 2020 banned outward travel by both Australian citizens and permanent residents, unless they requested and were granted an exemption. In August 2021 this ban was extended to people who are ordinarily resident in countries other than Australia as well. Exceptions apply to business travel and travel for "compelling reasons" for three months or longer, among others.[78][79]

On 1 November 2021, after 20 months, the exit permit system was scrapped and New South Wales and Victoria officially re-opened their borders in addition to ending quarantine requirements on arrival for fully vaccinated individuals. However, on 27 November 2021, 72-hour quarantine requirements were reinstated over concerns about the SARS-CoV-2 Omicron variant.

Visa refusal

[edit]In general, an applicant may be refused a visa if they do not meet the requirements for admission or entry under that country's immigration laws. More specifically, a visa may be denied or refused when the applicant:

- has committed fraud, deception, or misrepresentation in his or her current application as well as in a previous application

- has obtained a criminal record, has been arrested, or has criminal charges pending

- is considered to be a threat to national security

- does not have a good moral character

- has previous visa/immigration violations (even if the violations did not happen in the country the applicant is seeking a visa for)

- had their previous visa application(s) or application for immigration benefits refused and cannot prove that the reasons for the previous refusals no longer exist or are not applicable any more (even if the refusals did not previously happen in the country the applicant is seeking a visa for)

- cannot prove to have strong ties to their current country of nationality or residence (for those who are applying for temporary or non-immigrant visas)

- intends to reside or work permanently in the country she/he will visit if not applying for an immigrant or work visa respectively

- fails to demonstrate intent to return (for non-immigrants)

- fails to provide sufficient evidence/documents to prove eligibility for the visa sought after

- does not have a legitimate reason for the journey

- does not have adequate means of financial support for themselves or family

- does not have adequate medical insurance, especially if engaging in high risk activities (e.g. rock climbing, skiing, etc.)

- does not have travel arrangements (i.e. transport and lodging) in the destination country

- does not have health/travel insurance valid for the destination and the duration of stay

- is a citizen of a country to which the destination country is hostile or at war with

- has previously visited, or intends to visit, a country to which the destination country is hostile

- has a communicable disease, such as tuberculosis or ebola, or a sexually transmitted disease

- has a passport that expires too soon

Even if a traveller does not need a visa, the aforementioned criteria can also be used by border control officials to refuse the traveller's entry into the country in question.

Types

[edit]

Each country typically has a multitude of categories of visas with various names. The most common types and names of visas include:

By purpose

[edit]Transit visas

[edit]For passing through the country of issue to a destination outside that country. Validity of transit visas are usually limited by short terms such as several hours to ten days depending on the size of the country or the circumstances of a particular transit itinerary.

- Airside transit visa, required by some countries for passing through their airports even without going through passport control.

- Crew member, steward, or driver visa, issued to persons employed or trained on aircraft, vessels, trains, trucks, buses, and any other means of international transportation, or ships fishing in international waters.

Short-stay or visitor visas

[edit]For short visits to the visited country. Many countries differentiate between different reasons for these visits, such as:

- Private visa, for private visits by invitation from residents of the visited country.

- Tourist visa, for a limited period of leisure travel, no business activities allowed.

- Medical visa, for undertaking diagnostics or a course of treatment in the visited country's hospitals or other medical facilities.

- Business visa, for engaging in commerce in the country. These visas generally preclude permanent employment, for which a work visa would be required.

- Working holiday visa, for individuals travelling between nations offering a working holiday program, allowing young people to undertake temporary work while travelling.

- Athletic or artistic visa, issued to athletes and performing artists (and their supporting staff) performing at competitions, concerts, shows, and other events.

- Cultural exchange visa, usually issued to athletes and performing artists participating in a cultural exchange program.

- Refugee visa, issued to persons fleeing the dangers of persecution, a war or a natural disaster.

- Pilgrimage visa: this type of visa is mainly issued to those intending to visit religious destinations and/or to take part in particular religious ceremonies. Such visas can usually be obtained relatively quickly and at a low cost; those using them are usually permitted to travel only as a group, however. The most well-known example is Saudi Arabia's Hajj visa.[80]

Long-stay visas

[edit]Visas valid for long term stays of a specific duration include:

- Student visa (F-1 in the United States), which allows its holder to study at an institution of higher learning in the issuing country. The F-2 visa allows the student's dependents to accompany them in the United States.

- Research visa, for students doing fieldwork in the host country.

- Temporary worker visa, for approved employment in the host country. These are generally more difficult to obtain but valid for longer periods of time than a business visa. Examples of these are the United States' H-1B and L-1 visas. Depending on a particular country, the status of temporary worker may or may not evolve into the status of permanent resident or to naturalization.

- Journalist visa, which some countries require of people in that occupation when travelling for their respective news organizations. Countries that insist on this include Cuba, China, Iran, Japan, North Korea, Saudi Arabia, the United States (I-visa), and Zimbabwe.

- Residence visa, granted to people obtaining long-term residence in the host country. In some countries, such as New Zealand, long-term residence is a necessary step to obtain the status of a permanent resident.

- Asylum visa, issued to people who have suffered or reasonably fear persecution in their own country due to their political activities or opinion, or features, or association with a social group; or were exiled from their own country.

- Dependent visa, issued to certain family members of holder of a long-stay visa of certain other types (e.g., to spouse and children of a qualified employee holding a temporary worker visa).

- Self-employment visa, for self-employed people or entrepreneurs; see self-employment visa for more information.

- Digital nomad visa, for digital nomads who want to temporarily reside in a country while performing remote work. Thailand launched its SMART Visa, targeted at high expertise foreigners and entrepreneurs to stay a longer time in Thailand, with online applications for the visa being planned for late 2018.[81] Estonia has also announced plans for a digital nomad visa, after the launch of its e-Residency program.[82]

Immigrant visas

[edit]Granted for those intending to settle permanently in the issuing country (obtain the status of a permanent resident with a prospect of possible naturalization in the future):

- Spouse visa or partner visa, granted to the spouse, civil partner or de facto partner of a resident or citizen of a given country to enable the couple to settle in that country.

- Family member visa, for other members of the family of a resident or citizen of a given country. Usually, only the closest ones are covered:

- Parents, often restricted to helpless ones, i.e. those who, due to their elderly age or state of health, need supervision and care;

- Children (including adopted ones), often restricted to those who have not reached the age of maturity or helpless ones;

- Often also extended to grandchildren or grandparents, where their immediate parents or children, respectively, are for whichever reason unable to take care of them;

- Often also extended to helpless siblings.

- Marriage visa, granted for a limited period before intended marriage or conclusion of a civil partnership based on a proven relationship with a citizen of the destination country. For example, a German woman wishing to marry an American man would obtain a Fiancée Visa (also known as a K-1 visa) to allow her to enter the United States. A K1 Fiancée Visa is valid for four months from the date of its approval.[83]

- Pensioner visa (also known as retiree visa or retirement visa), issued by a limited number of countries (Australia, Argentina, Thailand, Panama, etc.), to those who can demonstrate a foreign source of income and who do not intend to work in the issuing country. Age limits apply in some cases.

Official visas

[edit]These are granted to officials doing jobs for their governments, or otherwise representing their countries in the host country, such as the personnel of diplomatic missions.

- A diplomatic visa in combination with a regular or diplomatic passport.[84]

- A courtesy visa is issued to representatives of foreign governments or international organizations who do not qualify for diplomatic status but do merit expedited, courteous treatment – an example of this is Australia's special purpose visa.

Visa openness

[edit]Henley Passport Index

[edit]The Henley Passport index ranks passports according to the number of destinations that can be reached using a particular country's ordinary passport without the need of a prior visa ("visa-free").[85][86][87] The survey ranks 199 passports against 227 destination[88] countries, territories, and micro-states.[89][90][91]

The IATA maintains a database of travel information worldwide and all destinations that are in the IATA database are considered by the index.[92] However, because not all territories issue passports, there are far fewer passports ranked than destinations about which queries are made.[93]

As of 16 July 2024, the Singaporean passport offers holders visa-free or visa-on-arrival access to a total of 195 countries[94] and territories,[95] followed by the Japanese, French, German, Italian, and Spanish passports offer holders visa-free or visa-on-arrival access to a total of 192 countries followed by the Austrian, Finnish, Irish, Luxembourgish, Dutch, South Korean and Swedish passports, each offering 191 visa-free or visa-on-arrival countries and territories to its holders.[96] These rankings were subsequently followed by the Belgian, Danish, New Zealand, Norwegian, Swiss, and British passports, each offering visa-free or visa-on-arrival travel to 190 countries and territories.[97] While the 2024 Henley Passport Index shows a worldwide improvement in access to visa-free travel, the gap between the top and the bottom ranked countries has widened.[98]

Asian countries like Japan and Singapore have dominated the top position in the Index for the last five years.[99]

The Afghan passport has once again been labelled by the index as the least powerful passport in the world, with its nationals only able to visit 28 destinations visa-free.[100][101] This was followed by the Syrian passport at 29 destinations, the Iraqi passport at 31 destinations and the Pakistani and Yemini passports at 34 destinations. Among African countries, the Somali passport is the weakest passport according to the index.[102]World Tourism Organization

[edit]The World Tourism Organization (UNWTO) of the United Nations has issued various Visa Openness Reports.

Non-visa restrictions

[edit]Blank passport pages

[edit]Many countries require a minimum number of blank pages to be available in the passport being presented, typically one or two pages.[103] Endorsement pages, which often appear after the visa pages, are not counted as being valid or available.

Vaccination

[edit]

The African countries of Angola, Benin, Burkina Faso, Burundi, Cameroon, Central African Republic, Chad, Democratic Republic of the Congo, Republic of the Congo, Côte d'Ivoire, Equatorial Guinea, Gabon, Gambia, Ghana, Guinea-Bissau, Kenya, Liberia, Mali, Mauritania, Niger, Rwanda, Senegal, Sierra Leone and Togo, South Sudan, Uganda, and Zambia, require all incoming passengers older than nine months to one year[104] to have a current International Certificate of Vaccination or Prophylaxis, as does the South American territory of French Guiana.[105]

Some other countries require vaccination only if the passenger is coming from an infected area or has visited one recently or has transited for 12 hours in those countries: Algeria, Botswana, Cabo Verde, Chad, Djibouti, Egypt, Eswatini, Ethiopia, Gambia, Ghana, Guinea, Lesotho, Libya, Equatorial Guinea, Eritrea, Madagascar, Malawi, Mauritania, Mauritius, Mozambique, Namibia, Nigeria, Papua New Guinea, Seychelles, Somalia, South Africa, Sudan, Tunisia, Uganda, United Republic of Tanzania, Zambia and Zimbabwe.[106][107]

Passport validity length

[edit]Very few countries, such as Paraguay, just require a valid passport on arrival.

However many countries and groupings now require only an identity card – especially from their neighbours. Other countries may have special bilateral arrangements that depart from the generality of their passport validity length policies to shorten the period of passport validity required for each other's citizens[108][109] or even accept passports that have already expired (but not been cancelled).[110]

Some countries, such as Japan,[111] Ireland and the United Kingdom,[112] require a passport valid throughout the period of the intended stay.

In the absence of specific bilateral agreements, countries requiring passports to be valid for at least 6 more months on arrival include Afghanistan, Algeria, Anguilla, Bahrain,[113] Bhutan, Botswana, British Virgin Islands, Brunei, Cambodia, Cameroon, Cape Verde, Cayman Islands, Central African Republic, Chad, Comoros, Costa Rica, Côte d'Ivoire, Curaçao, Ecuador, Egypt, El Salvador, Equatorial Guinea, Fiji, Gabon, Guinea Bissau, Guyana, Haiti, India, Indonesia, Iran, Iraq, Israel,[114] Jordan, Kenya, Kiribati, Kuwait, Laos, Madagascar, Malaysia, Marshall Islands, Mongolia, Myanmar, Namibia, Nepal, Nicaragua, Nigeria, Oman, Palau, Papua New Guinea, Peru,[115] Philippines,[116] Qatar, Rwanda, Samoa, Saudi Arabia, Singapore, Solomon Islands, Somalia, Sri Lanka, Sudan, Suriname, Tanzania, Thailand, Timor-Leste, Tokelau, Tonga, Turkey, Tuvalu, Uganda, United Arab Emirates, Vanuatu, Venezuela, and Vietnam.[117]

Countries requiring passports valid for at least 4 months on arrival include Micronesia and Zambia.

Countries requiring passports with a validity of at least 3 months beyond the date of intended departure include Azerbaijan, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Honduras, Montenegro, Nauru, Moldova and New Zealand. Similarly, the EEA countries of Iceland, Liechtenstein, Norway, all European Union countries (except Ireland) together with Switzerland also require 3 months validity beyond the date of the bearer's intended departure unless the bearer is an EEA or Swiss national.

Countries requiring passports valid for at least 3 months on arrival include Albania, North Macedonia, Panama, and Senegal.

Bermuda requires passports to be valid for at least 45 days upon entry.

Countries that require a passport validity of at least one month beyond the date of intended departure include Eritrea, Hong Kong, Lebanon, Macau, the Maldives[118] and South Africa.

Maximum passport age

[edit]Countries of the Schengen area require non-EU passports to be less than 10 years old upon entry.[119] A number of holders of British passports, which until September 2018 could be issued with a validity period of up to 10 years and nine months if the previous passport was not expired, were unable to travel to the EU subsequent to Brexit due to this restriction.[120]

Criminal record

[edit]Some countries, including Australia, Canada, Fiji, New Zealand and the United States,[121] routinely deny entry to non-citizens who have a criminal record, while others impose restrictions depending on the type of conviction and the length of the sentence.

Persona non grata

[edit]The government of a country can declare a diplomat persona non grata, banning them from entering the country or expelling them if they have already entered. In non-diplomatic use, the authorities of a country may also declare a foreigner persona non grata permanently or temporarily, usually because of unlawful activity.[122]

Israeli stamps

[edit]Kuwait,[123] Lebanon,[124] Libya,[125] and Yemen[126] do not allow entry to people with passport stamps from Israel or whose passports have either a used or an unused Israeli visa, or where there is evidence of previous travel to Israel such as entry or exit stamps from neighbouring border posts in transit countries such as Jordan and Egypt.

To circumvent this Arab League boycott of Israel, the Israeli immigration services have now mostly ceased to stamp foreign nationals' passports on either entry to or exit from Israel (unless the entry is for some work-related purposes). Since 15 January 2013, Israel no longer stamps foreign passports at Ben Gurion Airport. Passports are still (as of 22 June 2017[update]) stamped at Erez when passing into and out of Gaza.[citation needed]

Iran refuses admission to holders of passports containing an Israeli visa or stamp that is less than 12 months old.

Biometrics

[edit]Several countries mandate that all travellers, or all foreign travellers, be fingerprinted on arrival and will refuse admission to or even arrest travellers who refuse to comply. In some countries, such as the United States, this may apply even to transit passengers who merely wish to change planes rather than go landside.[127]

Fingerprinting countries/regions include Afghanistan,[128][129] Argentina,[130] Brunei, Cambodia,[131] China,[132] Ethiopia,[133] Ghana, Guinea,[134] India, Japan,[135][136] Kenya (both fingerprints and a photo are taken),[137] Malaysia upon entry and departure,[138] Mongolia, Saudi Arabia,[139] Singapore, South Korea,[140] Taiwan, Thailand,[141] Uganda,[142] the United Arab Emirates and the United States.

Many countries also require a photo be taken of people entering the country. The United States, which does not fully implement exit control formalities at its land frontiers (although long mandated by its own legislation),[143][144][145] intends to implement facial recognition for passengers departing from international airports to identify people who overstay their visa.[146]

Together with fingerprint and face recognition, iris scanning is one of three biometric identification technologies internationally standardised since 2006 by the International Civil Aviation Organization (ICAO) for use in e-passports[147] and the United Arab Emirates conducts iris scanning on visitors who need to apply for a visa.[148][149] The United States Department of Homeland Security has announced plans to greatly increase the biometric data it collects at US borders.[150] In 2018, Singapore began trials of iris scanning at three land and maritime immigration checkpoints.[151][152]

See also

[edit]- Vienna Convention on Consular Relations

- Visa fraud

- Electronic Travel Authority (Australia)

- Electronic System for Travel Authorization (US)

- Entry certificate

- List of citizenships refused entry to foreign states

- Non-visa travel restrictions

- Travel document

- Van Der Elst visa

- Commonwealth Register of Institutions and Courses for Overseas Students (Australia)

References

[edit]- ^ "visa | Origin and meaning of visa by Online Etymology Dictionary". www.etymonline.com.

- ^ "Visa requirements for tourism eased around the world: UN agency". torontosun. 15 January 2016.

- ^ Visa Openness Report 2015 January 2016. 2016. doi:10.18111/9789284417384. ISBN 9789284417384.

- ^ "History of passports – Passport Canada". 3 June 2013. Archived from the original on 3 June 2013. Retrieved 26 June 2018.

- ^ Benedictus, Leo (17 November 2006). "A brief history of the passport". the Guardian. Retrieved 26 June 2018.

- ^ Robertson, Craig (29 November 2012), ""The Passport Nuisance"", The Passport in America, Oxford University Press, pp. 215–244, doi:10.1093/acprof:osobl/9780199927579.003.0012, ISBN 978-0-19-992757-9, retrieved 29 September 2024

- ^ T, T. (23 July 2023). "A History of the Passport: Travel Document Evolution | by Tom Topol". Passport-collector.com. Retrieved 29 September 2024.

- ^ Mangion, Nicola; Insider, Investment Migration (2 June 2020). "The Passport Throughout History – The Evolution of a Document". IMI – Investment Migration Insider. Retrieved 29 September 2024.

- ^ "International.gc.ca". Gouvernement du Canada, Affaires étrangères et Commerce international Canada.

- ^ a b "Affaires mondiales Canada – international.gc.ca". Gouvernement du Canada, Affaires étrangères et Commerce international Canada. 17 September 2020.

- ^ a b "Eprints.lse.ac.uk" (PDF).

- ^ "Study Finds Global Visa Curbs Increasingly Restrictive, Imbalanced" (Press release).

- ^ Magris, Francesco; Russo, Giuseppe (2005). "Voting on Mass Immigration Restriction". Rivista Internazionale di Scienze Sociali. 113 (1): 67–92. ISSN 0035-676X.

- ^ Derrick, Khadija (12 January 2024). "What is visa reciprocity? | Scott Legal, P.C." Scott Legal, P.C. Immigration and Business Law |. Archived from the original on 20 January 2025. Retrieved 23 March 2025.

- ^ "EU visa reciprocity mechanism - Questions and Answers - EU monitor". www.eumonitor.eu. Retrieved 23 March 2025.

- ^ The Canada-Czech Republic Visa Affair: A test for visa reciprocity and fundamental rights in the European Union

- ^ Carrera, Sergio; Guild, Elspeth; Merlino, Massimo (October 2011). "The Canada-Czech Republic visa dispute two years on-Implications for the EU's migration and asylum policies. CEPS Liberty and Security in Europe, October 2011". shop.ceps.eu. Retrieved 23 March 2025.

- ^ B. S. Prakash (31 May 2006). "Only an exit visa". Retrieved 10 May 2008.

- ^ "Visa and passport". Timatic. International Air Transport Association through Emirates.

- ^ "22 Visa Free Countries for Bangladeshi Passport Holders". visaguide.world. Retrieved 18 April 2024.

- ^ "Bangladesh Online MRV Portal". visa.gov.bd. Retrieved 18 April 2024.

- ^ "Visit Visa / Entry Permit Requirements for the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region | Immigration Department". www.immd.gov.hk.

- ^ "Indian Tourist Visa On Arrival". Retrieved 7 January 2015.

- ^ Encompasses Schengen member states – Austria, Belgium, Czech Republic, Denmark, Estonia, Finland, France, Germany, Greece, Hungary, Iceland, Italy, Latvia, Liechtenstein, Lithuania, Luxembourg, Malta, Netherlands, Norway, Poland, Portugal, Slovakia, Slovenia, Spain, Sweden and Switzerland as well as Bulgaria, Croatia, Cyprus and Romania and countries without border controls – Monaco, San Marino, Vatican and a country accessible only via Schengen area – Andorra.

- ^ "Esta.cbp.dhs.gov". Archived from the original on 9 December 2014. Retrieved 15 September 2014.

- ^ "Background: U.S. Land Border Crossing Updated Procedures". United States Department of Homeland Security. 31 January 2008. Retrieved 13 September 2020.

- ^ "ECOWAS Official Site". Archived from the original on 19 May 2007. Retrieved 1 November 2006.

- ^ "Tanzanian Embassy in France". Archived from the original on 24 November 2006. Retrieved 1 November 2006.

- ^ "Ugandan Visa". Archived from the original on 18 November 2006. Retrieved 1 November 2006.

- ^ "Kenyahighcommission.net".

- ^ "Residir no Mercosul" (in Brazilian Portuguese). Mercosur. Retrieved 26 July 2021.

- ^ "Turismo" (in Brazilian Portuguese). Mercosur. Retrieved 26 July 2021.

- ^ "The Henley & Partners Passport Index" (PDF). Henley & Partners Holdings Ltd. 26 March 2019. Retrieved 6 June 2019.

This graph shows the full Global Ranking of the 2019 Henley Passport Index. As the index uses dense ranking, in certain cases, a rank is shared by multiple countries because these countries all have the same level of visa-free or visa-on-arrival access.

- ^ "CLMV bloc inks tourism pact, mulls over single tourist visa – TTG Asia – Leader in Hotel, Airlines, Tourism and Travel Trade News". TTG Asia. Archived from the original on 14 September 2014. Retrieved 22 October 2013.

- ^ "Thailand-Cambodia joint visa delayed | Bangkok Post: news". Bangkok Post. 23 November 2012. Retrieved 22 October 2013.

- ^ "Thai-Cambodia single visa for visitors". Yahoo News Maktoob. En-maktoob.news.yahoo.com. IANS. 27 December 2012. Retrieved 22 October 2013.

- ^ "Single GCC tourism visa will boost visitor numbers — study". GulfNews.com. 18 November 2012. Retrieved 22 October 2013.

- ^ "México, Colombia, Chile y Perú crean la visa Alianza del Pacífico – CNN en Español: Ultimas Noticias de Estados Unidos, Latinoamérica y el Mundo, Opinión y Videos – CNN.com Blogs". Cnnespanol.cnn.com. 24 May 2013. Retrieved 22 October 2013.

- ^ "Single East African visa for tourists coming in November". Archived from the original on 31 May 2008.

- ^ "East Africa geared for single tourist entry visa program". Archived from the original on 5 March 2009.

- ^ a b "SA teams vs local schools | Namibia Economist".

- ^ "Single visa proposed for southern Africa for 2010". sagoodnews.co.za. Archived from the original on 24 September 2006.

- ^ "Zim, Zambia revive Kaza Uni-Visa – The Chronicle". www.chronicle.co.zw. 22 December 2016.

- ^ "Regulation (EC) No 810/2009 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 13 July 2009 establishing a Community Code on Visas (Visa Code)". Archived from the original on 17 November 2009.

- ^ "Act 212(b) | USCIS". www.uscis.gov. Retrieved 14 February 2019.

- ^ VisasNews (16 May 2025). "Thailand: financial evidence once again required for tourist visas". VisasNews. Retrieved 17 September 2025.

- ^ "Embassy of the Republic of Indonesia – Visa On Arrival". www.kemlu.go.id. Archived from the original on 25 March 2019. Retrieved 25 March 2019.

- ^ "Visa Waiver Program | Embassy of the United States Canberra, Australia". 2 March 2012. Archived from the original on 2 March 2012. Retrieved 1 May 2020.

- ^ Jill Elaine Hasday (16 June 2014). Family Law Reimagined. Harvard University Press. pp. 58–. ISBN 978-0-674-36985-6.

- ^ Robert, Stuartt (24 October 2019). "Media release: Child Support and welfare debt". servicesaustralia.gov.au. Australian Government Services. Retrieved 9 February 2021.

- ^ "Essential information for New Zealanders travelling overseas" (PDF). safetravel.govt.nz. New Zealand Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade. Retrieved 9 February 2021.

- ^ Harvey, Colin; Barnidge, Robert P. Jr. (September 2005). The right to leave ones own country under international law (PDF) (Report). Global Commission on International Migration. Archived from the original (PDF) on 6 April 2021. Retrieved 30 April 2021.

- ^ "Cuba/United States: Families Torn Apart: II. Cuba's Restrictions on Travel". www.hrw.org. Retrieved 30 April 2021.

- ^ Rolando García Quiñones, Director del Centro de Estudios Demográficos (CEDEM), Cuba: International Migrations in Cuba: persisting trends and changes Archived 5 October 2006 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Saudi Arabia: Labor Reforms Insufficient". Human Rights Watch. 25 March 2021. Retrieved 30 April 2021.

- ^ Montague, James (1 May 2013). "Desert heat: World Cup hosts Qatar face scrutiny over 'slavery' accusations". CNN. Archived from the original on 20 December 2017. Retrieved 30 March 2021.

- ^ "The Middle East's migrant workers: Forget about rights". The Economist. 10 August 2013.

- ^ Commissioner for Human Rights (October 2013). The right to leave a country (Report). France: Council of Europe.

- ^ "Qatar lifts controversial exit visa system for most workers". Reuters. 4 September 2018.

- ^ Gad, Ben Zion (27 December 2021). "Man Banned From Leaving Israel For 8,000 Years Over Child Support Payments". The Jerusalem Post. Retrieved 3 January 2022.

- ^ "Department of Labour and Occupational Safety". www.dol.gov.np.

- ^ "Uzbekistan Scraps Exit Visas – Transitions Online". www.tol.org. Archived from the original on 3 June 2019. Retrieved 8 January 2019.

- ^ "NGO REPORT On the implementation of the ICCPR" (PDF). April 2009. Retrieved 29 April 2010. Freedom of Movement (article 12): "Exit visas and propiska violate not only international law such as the ICCPR, but also the Constitution of the Republic of Uzbekistan"

- ^ "China to allow mainlanders to make transit stops in Taiwan". Reuters. 6 January 2016. Retrieved 26 October 2024.

- ^ Yu, Hsiao-han; Pan, Hsin-tung; Sunny, Lai (22 August 2024). "China lifts restrictions on Fujian residents traveling to Taiwan-held Matsu". Focus Taiwan – CNA English News. Central News Agency. Retrieved 26 October 2024.

- ^ Enlistment Act (25, s. 32). 1970.

- ^ "National Service: Exit permit requirements". ecitizen.gov.sg. Archived from the original on 8 January 2017. Retrieved 11 November 2016.

- ^ Amount equal to SGD 75,000 or 50% of the parents' combined annual income (whichever is greater), covered by a banker's guarantee.

- ^ "內政部役政署役男線上申請短期出境". www.ris.gov.tw.

- ^ Encarta.msn.com. Archived from the original on 11 October 2008. Retrieved 12 November 2008.

- ^ "Declaration to Travel: Government Reveals New 'Exit' Permit Required to Leave England". Independent.co.uk. 10 March 2021.

- ^ "Travel abroad from England during coronavirus (COVID-19)". GOV.UK. 5 April 2023.

- ^ "COVID-19 Travel Restrictions: Standard Documentation Requirements". 23 July 2021.

- ^ Human Rights Watch (17 December 2013), "World Report 2014: Cuba", English, retrieved 1 August 2023