Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Bengalis

View on Wikipedia

Key Information

| Part of a series on |

| Bengalis |

|---|

|

| Part of a series on the |

| Culture of Bengal |

|---|

|

| History |

| Cuisine |

Bengalis (Bengali: বাঙ্গালী, বাঙালি [baŋgali, baŋali] ⓘ), also rendered as endonym Bangalee,[56][57] are an Indo-Aryan ethnolinguistic group originating from and culturally affiliated with the Bengal region of South Asia. The current population is divided between the sovereign country Bangladesh and the Indian regions of West Bengal, Tripura, Barak Valley of Assam, Andaman and Nicobar Islands, and parts of Meghalaya, Manipur and Jharkhand.[58] Most speak Bengali, a classical language from the Indo-Aryan language family.

Bengalis are the third-largest ethnic group in the world, after the Han Chinese and Arabs.[59] They are the largest ethnic group within the Indo–European linguistic family and the largest ethnic group in South Asia. Apart from Bangladesh and the Indian states of West Bengal, Tripura, Manipur, and Assam's Barak Valley, Bengali-majority populations also reside in India's union territory of Andaman and Nicobar Islands, with significant populations in the Indian states of Arunachal Pradesh, Delhi, Odisha, Chhattisgarh, Jharkhand, Mizoram, Nagaland and Uttarakhand as well as Nepal's Province No. 1.[60][61] The global Bengali diaspora have well-established communities in the Middle East, Pakistan, Myanmar, the United Kingdom, the United States, Malaysia, Italy, Singapore, Maldives, Canada, Australia, Japan and South Korea.

Bengalis are a diverse group in terms of religious affiliations and practices. Approximately 70% are adherents of Islam with a large Hindu minority and sizeable communities of Christians and Buddhists. Bengali Muslims, who live mainly in Bangladesh, primarily belong to the Sunni denomination. Bengali Hindus, who live primarily in West Bengal, Tripura, Assam's Barak Valley, Jharkhand and Andaman and Nicobar Islands, generally follow Shaktism or Vaishnavism, in addition to worshipping regional deities.[62][63][64] There exist small numbers of Bengali Christians, a large number of whom are descendants of Portuguese voyagers, as well as Bengali Buddhists, the bulk of whom belong to the Bengali-speaking Barua group in Chittagong and Rakhine. There is also a Bengali Jain caste named Sarak residing in Rarh region of West Bengal and Jharkhand.[65]

Bengalis have influenced and contributed to diverse fields, notably the arts and architecture, language, folklore, literature, politics, military, business, science and technology.

Etymology

[edit]

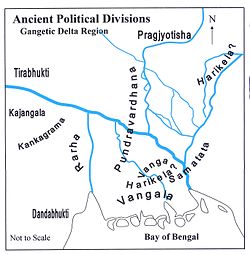

The term Bengali is generally used to refer to someone whose linguistic, cultural or ancestral origins are from Bengal. The Indo-Aryan Bengalis are ethnically differentiated from the non-Indo-Aryan tribes inhabiting Bengal. Their ethnonym, Bangali, along with the native name of the Bengali language and Bengal region, Bangla, are both derived from Bangālah, the Persian word for the region. Prior to Muslim expansion, there was no unitary territory by this name as the region was instead divided into numerous geopolitical divisions. The most prominent of these were Vaṅga or Vaṅgāla (from which Bangālah is thought to ultimately derive from) in the south, Rāṛha in the west, Puṇḍravardhana and Varendra in the north, and Samataṭa and Harikela in the east.[citation needed]

The historic land of Vaṅga (bôngô in Bengali), situated in present-day Barisal,[66] is considered by early historians of the Abrahamic and Dharmic traditions to have originated from a man who had settled in the area though it is often dismissed as legend. Early Abrahamic genealogists had suggested that this man was Bang, a son of Hind who was the son of Ham (son of Noah).[67][68][69] In contrast, the Mahabharata, Puranas and the Harivamsha state that Vaṅga was the founder of the Vaṅga kingdom and one of the adopted sons of King Vali. The land of Vaṅga later came to be known as Vaṅgāla (Bôngal) and its earliest reference is in the Comilla copperplates (720 CE) of earlier Buddhist Deva King Anandadeva where he was mentioned in the title of Sri Vaṅgāla Mrigānka, means the moon of Bengal.[70][71] Another reference is the Nesari plates (805 CE) of Govinda III which speak of Dharmapāla as its king. The records of Rajendra Chola I of the Chola dynasty, who invaded Bengal in the 11th century, speak of Govindachandra as the ruler of Vaṅgāladeśa (a Sanskrit cognate to the word Bangladesh, which was historically a synonymous endonym of Bengal).[72][73] 16th-century historian Abu'l-Fazl ibn Mubarak mentions in his ʿAin-i-Akbarī that the addition of the suffix "al" came from the fact that the ancient rajahs of the land raised mounds of earth 10 feet high and 20 in breadth in lowlands at the foot of the hills which were called "al".[74] This is also mentioned in Ghulam Husain Salim's Riyāz us-Salāṭīn.[67]

In 1352, Muslim nobleman Shamsuddin Ilyas Shah united the region into a single political entity known as the Bengal Sultanate. Proclaiming himself as Shāh-i-Bangālīyān,[75] it was in this period that the Bengali language gained state patronage and corroborated literary development.[76][77] Ilyas Shah had effectively unified the region into one country.[78]

History

[edit]Ancient history

[edit]

Archaeologists have discovered remnants of a 4,700-year-old Neolithic and Chalcolithic civilisation such as Dihar[79] and Pandu Rajar Dhibi[80] in the greater Bengal region, and believe the finds are one of the earliest signs of settlement in the region.[81] However, evidence of much older Palaeolithic human habitations were found in the form of a stone implement and a hand axe in the upper Gandeshwari, Middle Dwarakeswar, Upper Kangsabati, Upper Tarafeni and Middle Subarnarekha valleys of the Indian state West Bengal,[82] and Rangamati and Feni districts of Bangladesh.[83] Evidence of 42,000 years old human habitation has been found at the foothills of the Ajodhya Hills in West Bengal.[84][85][86] Hatpara on the west bank of Bhagirathi River has evidence of human settlements dating back to around 15,000-20,000 years.[87]

Artefacts suggest that the Chandraketugarh, which flourished in present-day North 24 Parganas, date as far back as 600 BC to 300 BC,[88] and Wari-Bateshwar civilisation, which flourished in present-day Narsingdi, date as far back as 400 BC to 100 BC.[89][90] Not far from the rivers, the port city of Wari-Bateshwar, and the riverside port city of the Chandraketugarh,[91] are believed to have been engaged in foreign trade with Ancient Rome, Southeast Asia and other regions.[91] The people of this civilisation live in bricked homes, walked on wide roads, used silver coins[92] and iron weaponry among many other things. The two cities are considered to be the oldest cities in Bengal.[93]

It is thought that a man named Vanga settled in the area around 1000 BCE founding the Vanga kingdom in southern Bengal. The Atharvaveda and the Hindu epic Mahabharata mentions this kingdom, along with the Pundra kingdom in northern Bengal. The spread of Mauryan territory and promotion of Buddhism by its emperor Ashoka cultivated a growing Buddhist society among the people of present-day Bengal from the 2nd century BCE. Mauryan monuments as far as the Great Stupa of Sanchi in Madhya Pradesh mentioned the people of this region as adherents of Buddhism. The Buddhists of the Bengal region built and used dozens of monasteries, and were recognised for their religious commitments as far as Nagarjunakonda in South India.[94]

One of the earliest foreign references to Bengal is the mention of a land ruled by the king Xandrammes named Gangaridai by the Greeks around 100 BCE. The word is speculated to have come from Gangahrd ('Land with the Ganges in its heart') in reference to an area in Bengal.[95] Later from the 3rd to the 6th centuries CE, the kingdom of Magadha served as the seat of the Gupta Empire.

Middle Ages

[edit]

One of the first recorded independent kings of Bengal was Shashanka,[96] reigning around the early 7th century, who is generally thought to have originated from Magadha, Bihar, just west of Bengal.[97] After a period of anarchy, a native ruler called Gopala came into power in 750 CE. He originated from Varendra in northern Bengal,[98] and founded the Buddhist Pala Empire.[99] Atiśa, a renowned Buddhist teacher from eastern Bengal, was instrumental in the revival of Buddhism in Tibet and also held the position of Abbot at the Vikramashila monastery in Bihar.

The Pala Empire enjoyed relations with the Srivijaya Empire, the Tibetan Empire, and the Arab Abbasid Caliphate. Islam first appeared in Bengal during Pala rule, as a result of increased trade between Bengal and the Middle East.[100] The people of Samatata, in southeastern Bengal, during the 10th century were of various religious backgrounds. Tilopa was a prominent Buddhist from modern-day Chittagong, though Samatata was ruled by the Buddhist Chandra dynasty. During this time, the Arab geographer Al-Masudi and author of The Meadows of Gold, travelled to the region where he noticed a Muslim community of inhabitants residing in the region.[101] In addition to trade, Islam was also being introduced to the people of Bengal through the migration of Sufi missionaries prior to conquest. The earliest known Sufi missionaries were Syed Shah Surkhul Antia and his students, most notably Shah Sultan Rumi, in the 11th century. Rumi settled in present-day Netrokona, Mymensingh where he influenced the local ruler and population to embrace Islam.

The Pala dynasty was followed by a shorter reign of the Hindu Sena Empire. Subsequent Muslim conquests helped spread Islam throughout the region.[102] Bakhtiyar Khalji, a Turkic general, defeated Lakshman Sen of the Sena dynasty and conquered large parts of Bengal. Consequently, the region was ruled by dynasties of sultans and feudal lords under the Bengal Sultanate for the next few hundred years. Many of the people of Bengal began accepting Islam through the influx of missionaries[citation needed] following the initial conquest. Sultan Balkhi and Shah Makhdum Rupos settled in the present-day Rajshahi Division in northern Bengal, preaching to the communities there. A community of 13 Muslim families headed by Burhanuddin also existed in the northeastern Hindu city of Srihatta (Sylhet), claiming their descendants to have arrived from Chittagong.[103] By 1303, hundreds of Sufi preachers led by Shah Jalal, who some biographers claim was a Turkistan-born Bengali,[104] aided the Muslim rulers in Bengal to conquer Sylhet, turning the town into Jalal's headquarters for religious activities. Following the conquest, Jalal disseminated his followers across different parts of Bengal to spread Islam, and became a household name among Bengali Muslims.

The establishment of a single united Bengal Sultanate in 1352 by Shamsuddin Ilyas Shah finally gave rise to the name Bangala for the region, and the development of Bengali language.[75] The Ilyas Shahi dynasty acknowledged Muslim scholarship, and this transcended ethnic background. Usman Serajuddin, also known as Akhi Siraj Bengali, was a native of Gaur in western Bengal and became the Sultanate's court scholar during Ilyas Shah's reign.[105][106][107] Alongside Persian and Arabic, the sovereign Sunni Muslim nation-state also enabled the language of the Bengali people to gain patronage and support, contrary to previous states which exclusively favoured Sanskrit, Pali and Persian.[76][77] The born-Hindu Sultan Jalaluddin Muhammad Shah funded the construction of Islamic institutions as far as Mecca and Madina in the Middle East. The people of Arabia came to know these institutions as al-Madaris al-Bangaliyyah (Bengali madrasas).

Mughal era

[edit]

The Mughal Empire conquered Bengal in the 16th century, ending the independent Sultanate of Bengal and defeating Bengal's rebellion Baro-Bhuiyan chieftains. Mughal general Man Singh conquered parts of Bengal including Dhaka during the time of Emperor Akbar and a few Rajput tribes from his army permanently settled around Dhaka and surrounding lands, integrating into Bengali society.[108] Akbar's preaching of the syncretic Din-i Ilahi, was described as a blasphemy by the Qadi of Bengal, which caused huge controversies in South Asia. In the 16th century, many Ulama of the Bengali Muslim intelligentsia migrated to other parts of the subcontinent as teachers and instructors of Islamic knowledge such as Ali Sher Bengali to Ahmedabad, Shah Manjhan to Sarangpur, Usman Bengali to Sambhal and Yusuf Bengali to Burhanpur.[109]

By the early 17th century, Islam Khan I had conquered all of Bengal and was integrated into a province known as the Bengal Subah. It was the largest subdivision of the Mughal Empire, as it also encompassed parts of Bihar and Odisha, between the 16th and 18th centuries.[citation needed] Described by some as the "Paradise of Nations"[110] and the "Golden Age of Bengal",[111] Bengalis enjoyed some of the highest living standards and real wages in the world at the time.[112] Singlehandedly accounting for 40% of Dutch imports from Asia,[113] eastern Bengal was globally prominent in industries such as textile manufacturing and shipbuilding,[114] and was a major exporter of silk and cotton textiles, steel, saltpetre, and agricultural and industrial produce in the world.

Mughal Bengal eventually became a quasi-independent monarchy state ruled by the Nawabs of Bengal in 1717. Already observing the proto-industrialization, it made direct significant contribution to the first Industrial Revolution[115][116][117][118] (substantially textile manufacture during the Industrial Revolution).

Bengal became the basis of the Anglo-Mughal War.[119][120] After the weakening of the Mughal Empire with the death of Emperor Aurangzeb in 1707, Bengal was ruled independently by three dynasties of Nawabs until 1757, when the region was annexed by the East India Company after the Battle of Plassey.

British colonisation

[edit]In Bengal, effective political and military power was transferred from the Afshar regime to the British East India Company around 1757–65.[121] Company rule in India began under the Bengal Presidency. Calcutta was named the capital of British India in 1772. The presidency was run by a military-civil administration, including the Bengal Army, and had the world's sixth earliest railway network. Great Bengal famines struck several times during colonial rule, notably the Great Bengal famine of 1770 and Bengal famine of 1943, each killing millions of Bengalis.

Under British rule, Bengal experienced deindustrialisation.[117] Discontent with the situation, numerous rebellions and revolts were attempted by the Bengali people. The Indian Rebellion of 1857 was initiated on the outskirts of Calcutta, and spread to Dhaka, Jalpaiguri and Agartala, in solidarity with revolts in North India. Havildar Rajab Ali commanded the rebels in Chittagong as far as Sylhet and Manipur. The failure of the rebellion led to the abolishment of the Mughal court completely and direct rule by the British Raj.

Many Bengali labourers were taken as coolies to the British colonies in the Caribbean during the 1830s. Workers from Bengal were chosen because they could easily assimilate to the climate of British Guyana, which was similar to that of Bengal.

Swami Vivekananda is considered a key figure in the introduction of Vedanta and Yoga in Europe and America,[122] and is credited with raising interfaith awareness, and bringing Hinduism to the status of a world religion during the 1800s.[123] On the other hand, Ram Mohan Roy led a socio-Hindu reformist movement known as Brahmoism which called for the abolishment of sati (widow sacrifice), child marriage, polytheism and idol worship.[124][125] In 1804, he wrote the Persian book Tuḥfat al-Muwaḥḥidīn (A Gift to the Monotheists) and spent the next two decades attacking the Kulin Brahmin bastions of Bengal.[126]

Independence movement

[edit]Bengal played a major role in the Indian independence movement, in which revolutionary groups such as Anushilan Samiti and Jugantar were dominant. Many of the early proponents of the independence struggle, and subsequent leaders in the movement were Bengalis such as Shamsher Gazi, Chowdhury Abu Torab Khan, Hada Miah and Mada Miah, the Pagal Panthis led by Karim Shah and Tipu Shah, Haji Shariatullah and Dudu Miyan of the Faraizi movement, Titumir, Ali Muhammad Shibli, Alimuddin Ahmad, Prafulla Chaki, Surendranath Banerjee, Maulana Abdul Hamid Khan Bhashani, Bagha Jatin, Khudiram Bose, Sarojini Naidu, Aurobindo Ghosh, Rashbehari Bose, and Sachindranath Sanyal.

Leaders such as Subhas Chandra Bose did not subscribe to the view that non-violent civil disobedience was the best way to achieve independence, and were instrumental in armed resistance against the British. Bose was the co-founder and leader of the Japanese-aligned Indian National Army (distinct from the British Indian Army) which fought against Allied forces in the Burma campaign. He was also the head of state of a parallel regime, the Azad Hind. A number of Bengalis died during the independence movement and many were imprisoned in the notorious Cellular Jail in the Andaman Islands.

Partitions of Bengal

[edit]The first partition in 1905 divided the Bengal region in British India into two provinces for administrative and development purposes. However, the partition stoked Hindu nationalism. This in turn led to the formation of the All India Muslim League in Dhaka in 1906 to represent the growing aspirations of the Muslim population. The partition was annulled in 1912 after protests by the Indian National Congress and Hindu Mahasabha.

The breakdown of Hindu-Muslim unity in India drove the Muslim League to adopt the Lahore Resolution in 1943, calling the creation of "independent states" in eastern and northwestern British India. The resolution paved the way for the Partition of British India based on the Radcliffe Line in 1947, despite attempts to form a United Bengal state that was opposed by many people.

Bangladesh Liberation War

[edit]The rise of self-determination and Bengali nationalism movements in East Bengal, led by Sheikh Mujibur Rahman. This eventually culminated in the 1971 Bangladesh Liberation War against the Pakistani military junta. The war caused millions of East Bengali refugees to take shelter in neighbouring India, especially the Indian state of West Bengal, with Calcutta, the capital of West Bengal, becoming the capital-in-exile of the Provisional Government of Bangladesh. The Mukti Bahini guerrilla forces waged a nine-month war against the Pakistani military. The conflict ended after the Indian Armed Forces intervened on the side of Bangladeshi forces in the final two weeks of the war, which ended with the surrender of East Pakistan and the liberation of Dhaka on 16 December 1971. Thus, the newly independent People's Republic of Bangladesh was born from what was previously the East Pakistan province of Pakistan.

Geographic distribution

[edit]- Bangladesh (61.3%)

- India (37.2%)

- Other Countries (1.50%)

Bengalis constitute the largest ethnic group in Bangladesh, at approximately 98% of the nation's inhabitants.[127] The Census of India does not recognise racial or ethnic groups within India,[128] the CIA Factbook estimated that there are 100 million Bengalis in India constituting 7% of the country's total population. In addition to West Bengal, Bengalis form the demographic majority in Assam's Barak Valley and Lower region as well as parts of Manipur.[58] The state of Tripura as well as the Andaman and Nicobar Islands union territory, which lies in the Bay of Bengal, are also home to a Bengali-majority population, most of whom are descendants of Hindus from East Bengal (now Bangladesh) that migrated there following the 1947 Partition of India.[129]: 3–4 [130][131] Bengali migration to the latter archipelago was also boosted by subsequent state-funded Colonisation Schemes by the Government of India.[132][133]

Bengali ethnic descent and emigrant communities are found primarily in other parts of the subcontinent, the Middle East and the Western World. Substantial populations descended from Bengali immigrants exist in Saudi Arabia, Pakistan and the United Kingdom where they form established communities of over 1 million people. The majority of the overseas Bengali diaspora are Muslims as the act of seafaring was traditionally prohibited in Hinduism; a taboo known as kala pani (black/dirty water).[134]

The introduction of Islam to the Bengali people has generated a connection to the Arabian Peninsula, as Muslims are required to visit the land once in their lifetime to complete the Hajj pilgrimage. Several Bengali sultans funded Islamic institutions in the Hejaz, which popularly became known by the Arabs as Bengali madrasas. As a result of the British conquest of Bengal, some Bengalis decided to emigrate to Arabia.[135] Notable examples include Mawlana Murad, an instructor of Islamic sciences based in Mecca in the early 1800s,[136] and Najib Ali Choudhury, a participant of the Battle of Shamli.[137] Notable people of Bengali-origin in the Middle East include the renowned author and journalist Ahmad Abd al-Ghafur Attar of Saudi Arabia and Qur'an translator Zohurul Hoque from Oman. The family of Princess Sarvath al-Hassan, wife of Jordanian prince Hassan bin Talal, are descended from the Suhrawardy family of Midnapore.[138]

Earliest records of Bengalis in the European continent date back to the reign of King George III of England during the 16th century. One such example is I'tisam-ud-Din, a Bengali Muslim cleric from Nadia in western Bengal, who arrived to Europe in 1765 with his servant Muhammad Muqim as a diplomat for the Mughal Empire.[139] Another example during this period is of James Achilles Kirkpatrick's hookah-bardar (hookah servant/preparer) who was said to have robbed and cheated Kirkpatrick, making his way to England and stylising himself as the Prince of Sylhet. The man, presumably from Sylhet in eastern Bengal, was waited upon by the Prime Minister of Great Britain William Pitt the Younger, and then dined with the Duke of York before presenting himself in front of the King.[140] Today, the British Bangladeshis are a naturalised community in the United Kingdom, running 90% of all South Asian cuisine restaurants and having established numerous ethnic enclaves across the country – most prominent of which is Banglatown in East London.[141]

Language

[edit]An important and unifying characteristic of Bengalis is that most of them use Bengali as their native tongue, which belongs to the Indo-Aryan language family.[142] With about 242 million native and about 284 million total speakers worldwide, Bengali is one of the most spoken languages, ranked sixth in the world,[143][144] and is also used a lingua franca among other ethnic groups and tribes living within and around the Bengal region. Bengali is generally written using the Bengali script and evolved circa 1000–1200 CE from Magadhi Prakrit, thus bearing similarities to ancient languages such as Pali. Its closest modern relatives are other Eastern Indo-Aryan languages such as Assamese, Odia and the Bihari languages.[145] Though Bengali may have a historic legacy of borrowing vocabulary from languages such as Persian and Sanskrit,[146] modern borrowings primarily come from the English language.

Various forms of the language are in use today and provide an important force for Bengali cohesion. These distinct forms can be sorted into three categories. The first is Classical Bengali (সাধু ভাষা Śadhu Bhaśa), which was a historical form restricted to literary usage up until the late British period. The second is Standard Bengali (চলিত ভাষা Čôlitô Bhaśa or শুদ্ধ ভাষা Śuddho Bhaśa), which is the modern literary form, and is based upon the dialects of the divided Nadia region (partitioned between Nadia and Kushtia). It is used today in writing and in formal speaking, for example, prepared speeches, some radio broadcasts, and non-entertainment content. The third and largest category by speakers would be Colloquial Bengali (আঞ্চলিক ভাষা Añčôlik Bhaśa or কথ্য ভাষা Kôththô Bhaśa). These refer to informal spoken language that varies by dialect from region to region.

Social stratification

[edit]Bengali people may be broadly classified into sub-groups predominantly based on dialect but also other aspects of culture:

- Bangals: This is a term used predominantly in Indian West Bengal to refer to East Bengalis – i.e. Bangladeshis as well as those whose ancestors originate from Eastern Bengal. The East Bengali dialects are known as Bangali. This group constitutes the majority of ethnic Bengalis. They originate from the mainland Bangladeshi regions of Dhaka, Mymensingh, Comilla, Sylhet, Barisal and Chittagong.

- Among Bangals, there are four subgroups that maintain distinct identities in addition to having a (Eastern) Bengali identity.[147][148] Chittagonians are natives of the Chittagong region (Chittagong District and Cox's Bazar District) of Bangladesh and speak Chittagonian. The people of Cox's Bazar are closely related to the Rohingyas of the Rakhine State in Myanmar. Sylhetis originate from the Sylhet Division of Bangladesh and they speak Sylheti. Noakhailla speakers can be found in greater Noakhali region and southern Tripura. The Dhakaiya Kuttis are a small urban Bengali Muslim community residing in Old Dhaka city that noticeably differ from the rest of the people of Dhaka Division by culture.

- Ghotis: This is the term favoured by the natives of West Bengal to distinguish themselves from other Bengalis.

- The region of North Bengal, which hosts Varendri and Rangpuri speakers, is divided between both West Bengal and Bangladesh, and they are normally categorised into the former two main groups depending on which side of the border they reside in even though they are culturally similar to each other regardless of international borders. The categorisation of North Bengalis into Ghoti or Bangal is contested. Rangpuri speakers can also be found in parts of Lower Assam, while the Shershahabadia community extend into Bihar. Other northern Bengali communities include the Khotta and Nashya Shaikh.

Bengalis Hindus are socially stratified into four castes, called chôturbôrṇô. The caste system derived from Hindu system of bôrṇô (type, order, colour or class) and jāti (clan, tribe, community or sub-community), which divides people into four colours: White, Red, Yellow and Black. White people are Brahmôṇ, who are destined to be priests, teachers and preachers; Red people are Kkhôtriyô, who are destined to be kings, governors, warriors and soldiers; Yellow people are Bôiśśô, who are born to be cattle herders, ploughmen, artisans and merchants; and Black people are Shūdrô, who are born to be labourers and servants to the people of twice-born caste.[150][151] People from all caste denominations exist among Bengali Hindus. Ram Mohan Roy, who was born Hindu, founded the Brahmo Samaj which attempted to abolish the practices of casteism, sati and child marriage among Hindus.[124]

Religion

[edit]

The largest religions practised in Bengal are Islam and Hinduism.[155] Among all Bengalis, more than two-thirds are Muslims. The vast majority follow the Sunni denomination though there are also a small minority of Shias. The Bengali Muslims form a 90.4% majority in Bangladesh,[156] and a 30% minority among the ethnic Bengalis in the entirety of India.[157][158][159][160][161] In West Bengal, Bengali Muslims form a 66.88% majority in Murshidabad district, the former seat of the Shia Nawabs of Bengal, a 51.27% majority in Malda, which contains the erstwhile capitals of the Sunni Bengal Sultanate, and they also number over 5,487,759 in the 24 Parganas.[162]

Just less than a third of all Bengalis are Hindus (predominantly, the Shaktas and Vaishnavists),[62] and as per as 2011 census report, they form a 70.54% majority in West Bengal, 50% plurality in Southern Assam's Barak Valley region,[163] 60% majority in the India's North Eastern state of Tripura,[164] 28% plurality in Andaman and Nicobar Islands, 9% significance population in India's Eastern state of Jharkhand[165] and 7.95% minority in Bangladesh.[166][160] In Bangladesh, Hindus are mostly concentrated in Sylhet Division where they constitute 13.51% of the population, and are mostly populated in Dhaka Division where they number over 2.7 million. Hindus form a 54.46% majority in Dacope Upazila. In terms of population, Bangladesh is the third largest Hindu populated country of the world, just after India and Nepal. The total Hindu population in Bangladesh exceeds the population of many Muslim majority countries like Yemen, Jordan, Tajikistan, Syria, Tunisia, Oman, and others.[167] Also the total Hindu population in Bangladesh is roughly equal to the total population of Greece and Belgium.[168] Bengali Hindus also worship regional deities.[62][63][64]

Other religious groups include Buddhists (comprising around 1% of the population in Bangladesh) and Christians.[155][161] A large number of the Bengali Christians are descendants of Portuguese voyagers. The bulk of Bengali Buddhists belong to the Bengali-speaking Baruas who reside in Chittagong and Rakhine.[citation needed]

Culture

[edit]Festivals

[edit]

Bengalis have a rich cultural diversity in celebrating festivals throughout the year, suggesting the phrase - ''Baro Mashe Tero Parbon''. Along with major festivals, every month in the Bengali calendar has rituals for the well-being and prosperity for the family members, often called as brotos (vow).[169]

Durga Puja is the most significant festival of Bengali Hindus, celebrated annually, worshiping Hindu goddess Durga. In 2021, Durga Puja in Kolkata has been inscribed on the list of 'Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity' by UNESCO.[170] Kali Puja is another significant festival, celebrated with great fervour in the Hindu month of Kartit.[171][172] Worshiping Lakkhmi Puja has a unique tradition in every Bengali households.[173][174] Shakta Rash is the most celebrated festival and uniquely observed in Nabadwip.[175] Bengali Muslims have Islamic holidays Eid al-Adha and Eid al-Fitr. Relatives, friends, and neighbours visit and exchange food and sweets in those occasions.[176]

Pohela Boishakh is a celebration of the new year and arrival of summer in the Bengali calendar and is celebrated in April. Most of households and business establishments worship Lakshmi-Ganesh in this particular day for their success and prosperity.[177] It features a funfair, music and dance displays on stages, with people dressed in colourful traditional clothes, parading through the streets.[178] Festivals like Pahela Falgun (spring) are also celebrated regardless of their faith. The Bengalis of Dhaka celebrate Shakrain, an annual kite festival. The Nabanna is a Bengali celebration akin to the harvest festivals in the Western world. Language Movement Day is observed in Bangladesh and India. In 1999, UNESCO declared 21 February as International Mother Language Day, in tribute to the Language Movement and the ethnolinguistic rights of people around the world.[179] Kolkata Book Fair is the world's largest non-trade and the most attended book fair, where people from different countries gather together.[180]

Fashion and arts

[edit]Visual art and architecture

[edit]The recorded history of art in Bengal can be traced to the 3rd century BCE, when terracotta sculptures were made in the region. The architecture of the Bengal Sultanate saw a distinct style of domed mosques with complex niche pillars that had no minarets. Ivory, pottery and brass were also widely used in Bengali art.

Attire and clothing

[edit]Bengali attire shares similarities with North Indian attire. In rural areas, older women wear the shari while the younger generation wear the selwar kamiz, both with simple designs. In urban areas, the selwar kamiz is more popular, and has distinct fashionable designs. Traditionally Bengali men wore the jama, though the costumes such as the panjabi with selwar or pyjama have become more popular within the past three centuries. The popularity of the fotua, a shorter upper garment, is undeniable among Bengalis in casual environments. The lungi and gamcha are a common combination for rural Bengali men. Islamic clothing is also very common in the region. During special occasions, Bengali women commonly wear either sharis, selwar kamizes or abayas, covering their hair with hijab or orna; and men wear a panjabi, also covering their hair with a tupi, toqi, pagri or rumal.

Mughal Bengal's most celebrated artistic tradition was the weaving of Jamdani motifs on fine muslin, which is now classified by UNESCO as an intangible cultural heritage. Jamdani motifs were similar to Iranian textile art (buta motifs) and Western textile art (paisley). The Jamdani weavers in Dhaka received imperial patronage.[181]

The traditional attire of Bengali Hindus is dhoti and kurta for men, and saree for women.

Performing arts

[edit]

Bengal has an extremely rich heritage of performing arts dating back to antiquity. It includes narrative forms, songs and dances, performance with scroll paintings, puppet theatre and the processional forms like the Jatra and cinema. Performing of plays and Jatras were mentioned in Charyapada, written in between the 8th and 12th centuries.[182] Chhau dance is a unique martial, tribal and folk art of Bengal. Wearing an earthy and theatrical Chhau mask, the dance is performed to highlight the folklore and episodes from Shaktism, Ramayana – Mahabharata and other abstract themes.[183][184] In 2010 the Chhau dance was inscribed in the UNESCO's Representative List of the Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity.[185]

Bengali film is a glorious part of the history of world cinema. Hiralal Sen, who is considered a stalwart of Victorian era cinema, sowed the first seeds of Bengali cinema.[183][186] In 1898, Sen founded the first film production company, named Royal Bioscope Company in Bengal, and possibly the first in India.[187] Along with Nemai Ghosh, Tapan Sinha and others, the golden age of Bengali cinema begins with the hands of Satyajit Ray, Mrinal Sen and Rittwik Ghatak.[188] Chinnamul was recognised as the first neo-realist film in India that deals with the partition of India.[189][190] Ray's first cinema Pather Panchali (1955) achieved the highest-ranking Indian film on any Sight & Sound poll at number 6 in the 1992 Critics' Poll.[191] It also topped the British Film Institute's user poll of Top 10 Indian Films of all time in 2002.[192] In the same year, Titash Ekti Nadir Naam, directed by Ritwik Ghatak with the joint production of India and Bangladesh, got the honour of best Bangladeshi films in the audience and critics' polls conducted by the British Film Institute.[193]

Gastronomy

[edit]Bengali cuisine is the culinary style of the Bengali people. It has the only traditionally developed multi-course tradition from South Asia that is analogous in structure to the modern service à la russe style of French cuisine, with food served course-wise rather than all at once. The dishes of Bengal are often centuries old and reflect the rich history of trade in Bengal through spices, herbs, and foods. With an emphasis on fish and vegetables served with rice as a staple diet, Bengali cuisine is known for its subtle flavours, and its huge spread of confectioneries and milk-based desserts. One will find the following items in most dishes; mustard oil, fish, panch phoron, lamb, onion, rice, cardamom, yogurt and spices. The food is often served in plates which have a distinct flowery pattern often in blue or pink. Common beverages include shorbot, borhani, ghol, matha, lachhi, falooda, Rooh Afza, natural juices like Akher rosh, Khejur rosh, Aamrosh, Dudh cha, Taler rosh, Masala cha, as well as basil seed or tukma-based drinks.

Bangladeshi and West Bengali cuisines have many similarities, but also many unique traditions at the same time. These kitchens have been influenced by the history of the respective regions. The kitchens can be further divided into the urban and rural kitchens. Urban kitchens in Bangladesh consist of native dishes with foreign Mughal influence, for example the Haji biryani and Chevron Biryani of Old Dhaka.

Traditional Bengali Dishes:

Shorshe ilish, Biryani, Mezban, Khichuri, Macher Paturi, Chingri Malai Curry, Mishti Doi, etc. are some of the traditional dishes of the Bengali's.

Literature

[edit]Bengali literature denotes the body of writings in the Bengali language, which has developed over the course of roughly 13 centuries. The earliest extant work in Bengali literature can be found within the Charyapada, a collection of Buddhist mystic hymns dating back to the 10th and 11th centuries. They were discovered in the Royal Court Library of Nepal by Hara Prasad Shastri in 1907. The timeline of Bengali literature is divided into three periods − ancient (650–1200), medieval (1200–1800) and modern (after 1800). Medieval Bengali literature consists of various poetic genres, including Islamic epics by the likes of Abdul Hakim and Syed Sultan, secular texts by Muslim poets like Alaol and Vaishnava texts by the followers of Krishna Chaitanya. Bengali writers began exploring different themes through narratives and epics such as religion, culture, cosmology, love and history. Royal courts such as that of the Bengal Sultanate and the kingdom of Mrauk U gave patronage to numerous Bengali writers such as Shah Muhammad Saghir, Daulat Qazi and Dawlat Wazir Bahram Khan.

The Bengali Renaissance refers to a socio-religious reform movement during the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, centered around the city of Calcutta and predominantly led by upper-caste Bengali Hindus under the patronage of the British Raj who had created a reformed religion known as the Brahmo Samaj. Historian Nitish Sengupta describes the Bengal renaissance as having begun with Raja Ram Mohan Roy (1775–1833) and ended with Asia's first Nobel laureate Rabindranath Tagore (1861–1941).[118]

Though the Bengal Renaissance was predominantly representative to the Hindu community due to their relationship with British colonisers,[194] there were, nevertheless, examples of modern Muslim littérateurs in this period. Mir Mosharraf Hossain (1847–1911) was the first major writer in the modern era to emerge from the Bengali Muslim society, and one of the finest prose writers in the Bengali language. His magnum opus Bishad Shindhu is a popular classic among Bengali readership. Kazi Nazrul Islam (1899–1976), notable for his activism and anti-British literature, was described as the Rebel Poet and is now recognised as the National poet of Bangladesh. Begum Rokeya (1880–1932) was the leading female Bengali author of this period, best known for writing Sultana's Dream which was subsequently translated into numerous languages.

Marriage

[edit]

A marriage among Bengalis often consists of multiple events rather than just one wedding. Arranged marriages are arguably the most common form of marriage among Bengalis and are considered traditional in society.[195] Marriage is seen as a union between two families rather than just two people,[196][197] and they play a large part in developing and maintaining social ties between families and villages. The two families are facilitated by Ghotoks (mutual matchmakers), and the first event is known as the Paka Dekha/Dekhadekhi where all those involved are familiarised with each other over a meal at the bride's home. The first main event is the Paan-Chini/Chini-Paan, hosted by the bride's family. Gifts are received from the groom's family and the marriage date is fixed in this event.[198] An adda takes place between the families as they consume a traditional Bengali banquet of food, paan, tea and mishti. The next event is the mehndi (henna) evening also known as the gaye holud (turmeric on the body). In Bengali Muslim weddings, this is normally followed by the main event, the walima, hosting thousands of guests. An aqd (vow) takes place, where a contract of marriage (Kabin nama) and is signed. A qazi or imam is usually present here and would also recite the Qur'an and make dua for the couple. The groom is required to pay mohor (dowry) to the bride. For Bengali Hindu weddings, a Hindu priest is present, and the groom and bride follow Hindu customs culminating in the groom putting sindoor (vermillion) on the head of the bride to indicate that she is now a married woman. The Phirajatra/Phirakhaowa consists of the return of the bride with her husband to her home, which then becomes referred to as Naiyor, and payesh and milk are served. Other post-marriage ceremonies include the Bou Bhat which takes place in the groom's home.

Arranged marriages are arguably the most common form of marriage among Bengalis and are considered traditional in society.[195] Though polygamy is rarity among Bengalis today, it was historically prevalent among both Muslims and Hindus prior to British colonisation and was a sign of prosperity.[199]

Science and technology

[edit]The contribution of Bengalis to modern science is pathbreaking in the world's context. Qazi Azizul Haque was an inventor who is credited for devising the mathematical basis behind a fingerprint classification system that continued to be used up until the 1990s for criminal investigations. Abdus Suttar Khan invented more than forty different alloys for commercial application in space shuttles, jet engines, train engines and industrial gas turbines. In 2006, Abul Hussam invented the Sono arsenic filter and subsequently became the recipient of the 2007 Grainger challenge Prize for Sustainability.[200] Another biomedical scientist, Parvez Haris, was listed among the top 1% of 100,000 scientists in the world by Stanford University.[201] Rafiqul Islam was the first to discover food saline (Orsaline) for the treatment of diarrhoea. The Lancet considered this discovery to be "the most important medical discovery of the 20th century".[202]

Fazlur Rahman Khan was a structural engineer responsible for making many important advancements in high rise designs.[203] He was the designer of Willis Tower, the tallest building in the world until 1998. Khan's seminal work of developing tall building structural systems are still used today as the starting point when considering design options for tall buildings.[204] In 2023, the billion-dollar Stable Diffusion deep learning text-to-image model was developed by Stability AI founded by Emad Mostaque.[205][206][207]

Jagadish Chandra Bose was a polymath: a physicist, biologist, botanist, archaeologist, and writer of science fiction[208] who pioneered the investigation of radio and microwave optics, made significant contributions to plant science, and laid the foundations of experimental science in the subcontinent.[209] He is considered one of the fathers of radio science,[210] and is also considered the father of Bengali science fiction. He first practicalised the wireless radio transmission but Guglielmo Marconi got recognition for it due to European proximity. Bose also described for the first time that "plants can respond", by demonstrating with his crescograph and recording the impulse caused by bromination of plant tissue.

Satyendra Nath Bose was a physicist, specialising in mathematical physics. He is best known for his work on quantum mechanics in the early 1920s, providing the foundation for Bose–Einstein statistics and the theory of the Bose–Einstein condensate. He is honoured as the namesake of the boson. He made first calculations to initiate Statistical Mechanics. He first hypothesised a physically tangible idea of photon. Bose's contemporary was Meghnad Saha, an astrophysicist and politician who contributed to the theorisation of thermal ionization. The Saha ionization equation, which was named after him, is used to describe chemical and physical conditions in stars.[211][212] His work allowed astronomers to accurately relate the spectral classes of stars to their actual temperatures.[213]

Economics and poverty alleviation

[edit]Several Bengali economists and entrepreneurs have made pioneering contributions in economic theories and practices supporting poverty alleviation. Amartya Sen is an economist and philosopher, who has made contributions to welfare economics, social choice theory, economic and social justice, economic theories of famines, decision theory, development economics, public health, and measures of well-being of countries. He was awarded the Nobel Memorial Prize in Economic Sciences[214] in 1998 and India's Bharat Ratna in 1999 for his work in welfare economics. Muhammad Yunus is a social entrepreneur, banker, economist and civil society leader who was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize for founding the Grameen Bank and pioneering the concepts of microcredit and microfinance. Abhijit Banerjee is an economist who shared the 2019 Nobel Memorial Prize in Economic Sciences with Esther Duflo and Michael Kremer "for their experimental approach to alleviating global poverty".[215][216]

Sport and games

[edit]

Traditional Bengali sports consisted of various martial arts and various racing sports, though the British-introduced sports of cricket and football are now most popular among Bengalis.

Lathi khela (stick-fighting) was historically a method of duelling as a way to protect or take land and others' possessions. The Zamindars of Bengal would hire lathials (trained stick-fighters) as a form of security and a means to forcefully collect tax from tenants.[217] Nationwide lathi khela competitions used to take place annually in Kushtia up until 1989, though its practice is now diminishing and being restricted to certain festivals and celebrations.[218] Chamdi is a variant of lathi khela popular in North Bengal. Kushti (wrestling) is also another popular fighting sport and it has developed regional forms such as boli khela, which was introduced in 1889 by Zamindar Qadir Bakhsh of Chittagong. A merchant known as Abdul Jabbar Saodagar adapted the sport in 1907 with the intention of cultivating a sport that would prepare Bengalis in fighting against British colonials.[219][220] In 1972, a popular contact team sport called Kabadi was made the national sport of Bangladesh. It is a regulated version of the rural Hadudu sport which had no fixed rules. The Amateur Kabaddi Federation of Bangladesh was formed in 1973.[221] Butthan, a 20th-century Bengali martial arts invented by Grandmaster Mak Yuree, is now practised in different parts of the world under the International Butthan Federation.[222]

The Nouka Baich is a Bengali boat racing competition which takes place during and after the rainy season when much of the land goes under water. The long canoes were referred to as khel nao (meaning playing boats) and the use of cymbals to accompany the singing was common. Different types of boats are used in different parts of Bengal.[223] Horse racing was patronised most notably by the Dighapatia Rajas in Natore, and their Chalanbeel Horse Races have continued to take place annually for centuries.

Football is the most popular sports among Bengalis.[224] Bengal is the home to Asia's oldest football league, Calcutta Football League and the fourth oldest cup tournament in the world, Durand Cup. East Bengal and Mohun Bagan are the biggest clubs in the region and subsequently India, and among the biggest in Asia. East Bengal and Mohun Bagan participate in Kolkata Derby, which is the biggest sports derby in Asia. Mohun Bagan, founded in 1889, is the oldest native football club of Bengal. The club is primarily supported by the Ghotis, who are the native inhabitants of West Bengal. East Bengal, on the contrary, was founded on 1 August 1920 and is a club Primarily supported by the ethnic eastern Bengalis. Mohun Bagan's first major victory was in 1911, when the team defeated an English club known as the Yorkshire Regiment to win the IFA Shield. In 2003, East Bengal became the first Indian club to win a major international trophy in the form of ASEAN Club Championship. While Mohun Bagan currently holds the most amount of national titles (6 in total), East Bengal is the stronger side in the Kolkata derby, having won 138 out of a total of 391 matches in which these two teams participited. East Bengal also takes the crown for having won the most major trophies in India (109 compared to the 105 of Mohun Bagan). Mohammed Salim of Calcutta became the first South Asian to play for a European football club in 1936.[225] In his two appearances for Celtic F.C., he played the entire matches barefoot and scored several goals.[226] In 2015, Hamza Choudhury became the first Bengali to play in the Premier League and is predicted to be the first British Asian to play for the England national football team.[227]

Bengalis are very competitive when it comes to board and home games such as Pachisi and its modern counterpart Ludo, as well as Latim, Carrom Board, Chor-Pulish, Kanamachi and Chess. Rani Hamid is one of the most successful chess players in the world, winning championships in Asia and Europe multiple times. Ramnath Biswas was a revolutionary soldier who embarked on three world tours on a bicycle in the 19th century.

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ "Bangladesh wants Bangla as an official UN language: Sheikh Hasina". The Times of India. PTI. 19 February 2012. Archived from the original on 29 September 2023. Retrieved 10 September 2023.

- ^ "General Assembly hears appeal for Bangla to be made an official UN language". UN.org. 27 September 2010. Archived from the original on 1 June 2022. Retrieved 1 June 2022.

- ^ "Hasina for Bengali as an official UN language". Ummid.com. Indo-Asian News Service. 28 September 2010. Archived from the original on 2 November 2022. Retrieved 1 June 2022.

- ^ "Ethnic population in 2022 census" (PDF).

- ^ "Census of India Website : Office of the Registrar General & Census Commissioner, India". Censusindia.gov.in. Archived from the original on 7 March 2022. Retrieved 27 February 2022.

- ^ "Scheduled Languages in descending order of speaker's strength – 2011" (PDF). Registrar General and Census Commissioner of India. 29 June 2018. Archived (PDF) from the original on 14 November 2018. Retrieved 28 June 2018.

- ^ "Saudi Arabia 2022 Census" (PDF). General Authority for Statistics (GASTAT), Kingdom of Saudi Arabia. Archived from the original (PDF) on 28 April 2024. Retrieved 14 October 2024.

- ^ "Stateless and helpless: The plight of ethnic Bengalis in Pakistan". Al Jazeera. Archived from the original on 20 September 2022. Retrieved 17 December 2022.

Ethnic Bengalis in Pakistan – an estimated two million – are the most discriminated ethnic community.

- ^ "Non-Saudi Population". Saudi Census 2022. Retrieved 18 March 2024.

- ^ "Migration Profile – UAE" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 6 February 2017. Retrieved 1 January 2020.

- ^ "Abuse of Bangladeshi Workers: Malaysian rights bodies for probe". The Daily Star. 10 December 2018. Archived from the original on 5 June 2021. Retrieved 3 June 2021.

- ^ "Bangladeshis top expatriate force in Oman". Gulf News. 12 July 2018. Archived from the original on 5 June 2021. Retrieved 4 June 2021.

- ^ Ethnic group and main language (detailed) Office for National Statistics. 28 March 2023. Retrieved on 4 November 2024.

- ^ "Ethnic group, England and Wales: Census 2021". Office for National Statistics. Retrieved 29 November 2022.

- ^ "Scotland's Census 2022 - Ethnic group, national identity, language and religion - Chart data". Scotland's Census. National Records of Scotland. 21 May 2024. Retrieved 21 May 2024. Alternative URL 'Search data by location' > 'All of Scotland' > 'Ethnic group, national identity, language and religion' > 'Ethnic Group'

- ^ "Census 2021 Ethnic group - full detail MS-B02". Northern Ireland Statistics and Research Agency. Retrieved 31 May 2023.

- ^ "Population of Qatar by nationality - 2019 report". Priya Dsouza. 15 August 2019. Archived from the original on 7 September 2019. Retrieved 4 June 2021.

- ^ a b Monem, Mobasser (November 2017). "Engagement of Non-resident Bangladeshis (NRBs) in National Development: Strategies, Challenges and Way Forward" (PDF). United Nations Development Programme.

- ^ "Bangladeshi Workers: Around 2 lakh may have to leave Kuwait". The Daily Star. 15 July 2020. Archived from the original on 11 June 2021. Retrieved 3 June 2021.

- ^ "Over 400 Bangladeshis murdered in South Africa in 4yrs". Dhaka Tribune. Agence France-Presse. 1 October 2019. Archived from the original on 15 May 2021. Retrieved 3 June 2021.

- ^ "B16001: Language Spoken at Home by ..." United States Census Bureau.

- ^ "More illegal Bangladeshi workers enter Bahraini labor market". Xinhua News Agency. 12 March 2017. Archived from the original on 24 May 2021. Retrieved 4 June 2021.

- ^ "Economic crisis in Lebanon: job losses, low pay hit expats". The Daily Star. 8 February 2020. Archived from the original on 16 May 2021. Retrieved 11 June 2021.

- ^ "Help at hand for Bangladeshi workers in Middle East". Arab News. 11 April 2020. Archived from the original on 22 September 2020. Retrieved 11 June 2021.

- ^ "Bangladeshis in Singapore". The Straits Times. 15 February 2020. Archived from the original on 11 June 2021. Retrieved 11 June 2021.

- ^ Shamsi, Tasdidaa; Al-Din, Zaheed (December 2015). Lifestyle of Bangladeshi Workers in Maldives. 13th Asian Business Research Conference. Bangladesh. Archived from the original on 5 October 2021. Retrieved 1 January 2020.

- ^ "Ethnic or cultural origin by gender and age: Canada, provinces and territories, census metropolitan areas and census agglomerations with parts". 26 October 2022.

- ^ "2021 People in Australia who were born in Bangladesh, Census Country of birth QuickStats | Australian Bureau of Statistics".

- ^ a b c Monem, Mobasser (July 2018). "Engagement of Nonresident Bangladeshis in National Development: Strategies, Challenges and Way Forward" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 27 August 2021. Retrieved 25 July 2021.

- ^ "Bangladeshi immigrants now at forefront at Portugal's Lisbon neighbourhood".

- ^ "Momen urges Portugal to open mission in Dhaka".

- ^ "Imigrantes da Índia e Bangladesh contestam alterações à lei de estrangeiros".

- ^ "Comunidade do Bangladesh em Portugal: três décadas de luta pela integração".

- ^ Mahmud, Jamil (3 April 2020). "Bangladeshis in Spain suffering". The Daily Star. Archived from the original on 16 May 2021. Retrieved 11 June 2021.

- ^ Mahbub, Mehdi (16 May 2016). "Brunei, a destination for Bangladeshi migrant workers". The Financial Express. Archived from the original on 16 May 2021. Retrieved 11 June 2021.

- ^ "令和5年末現在における在留外国人数について" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 16 October 2021. Retrieved 30 March 2024.

- ^ "Bangladeshi workers facing difficulty in sending money from Mauritius". The Daily Star. 4 May 2021. Archived from the original on 9 July 2021. Retrieved 20 July 2021.

- ^ Mahmud, Ezaz (17 April 2021). "South Korea bans issuing visas for Bangladeshis". The Daily Star. Archived from the original on 19 October 2021. Retrieved 12 October 2021.

- ^ "Fighting in Libya: Condition of thousands of Bangladeshis gets worse, says Bangladesh ambassador". Dhaka Tribune. 19 November 2019. Archived from the original on 16 May 2021. Retrieved 11 June 2021.

- ^ "Poland is cocking up migration in a very European way". The Economist. 22 February 2020. Archived from the original on 19 July 2021. Retrieved 20 July 2021.

- ^ "Bevölkerung und Erwerbstätigkeit" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 4 February 2021. Retrieved 4 June 2021.

- ^ "Stay in safer places". The Daily Star. 17 August 2013. Archived from the original on 1 November 2020. Retrieved 25 July 2021.

- ^ "Étrangers – Immigrés : pays de naissance et nationalités détaillés". Institut national de la statistique et des études économiques. Archived from the original on 23 February 2021. Retrieved 29 August 2021.

- ^ "Sweden: Asian immigrants by country of birth 2020". February 2021. Archived from the original on 24 May 2021. Retrieved 20 July 2021.

- ^ "Finland – A country of curiosity". The Daily Star. 14 October 2016. Archived from the original on 16 May 2021. Retrieved 25 July 2021.

- ^ "Livelihoods of Bangladeshis at stake in Covid-19 hit Brazil". The Daily Star. 19 May 2021. Archived from the original on 25 July 2021. Retrieved 25 July 2021.

- ^ "Bangladeshi Migrants in Europe 2020" (PDF). International Organization for Migration. Archived from the original (PDF) on 4 July 2021. Retrieved 26 July 2021.

- ^ "2018 Census ethnic group summaries | Stats NZ".

- ^ Mannan, Kazi Abdul; Kozlov, V.V. (1995). "Socio-economic life style of Bangladeshi man married to Russian girl: An analysis of migration and integration perspective". doi:10.2139/ssrn.3648152. SSRN 3648152.

- ^ Datta, Romita (13 November 2020). "The great Hindu vote trick". India Today. Archived from the original on 17 February 2023. Retrieved 4 October 2022.

Hindus add up to about 70 million in Bengal's 100 million population, of which around 55 million are Bengalis.

- ^ Ali, Zamser (5 December 2019). "EXCLUSIVE: BJP Govt plans to evict 70 lakh Muslims, 60 lakh Bengali Hindus through its Land Policy (2019) in Assam". Sabrang Communications. Archived from the original on 3 October 2022. Retrieved 4 October 2022.

Hence, about 70 lakh Assamese Muslims and 60 lakh Bengali-speaking Hindus face mass evictions and homelessness if the policy is allowed to be passed in the Assembly.

- ^ a b "Bengali speaking voters may prove crucial in the second phase of Assam poll". The News Web. April 2021. Archived from the original on 3 June 2021. Retrieved 9 March 2023.

- ^ "Census 2022: Number of Muslims increased in the country". Dhaka Tribune. 27 July 2022. Archived from the original on 26 March 2023. Retrieved 1 October 2022.

- ^ a b "Religions in Bangladesh | PEW-GRF". Archived from the original on 9 April 2022. Retrieved 9 March 2023.

- ^ a b Khan, Mojlum (2013). The Muslim Heritage of Bengal: The Lives, Thoughts and Achievements of Great Muslim Scholars, Writers and Reformers of Bangladesh and West Bengal. Kube Publishing Ltd. p. 2. ISBN 978-1-84774-052-6.

Bengali-speaking Muslims as a group consists of around 200 million people.

- ^ "Part I: The Republic – The Constitution of the People's Republic of Bangladesh". Ministry of Law, Justice and Parliamentary Affairs. 2010. Archived from the original on 10 November 2019. Retrieved 9 September 2017.

- ^ "Bangalees and indigenous people shake hands on peace prospects". Dhaka Tribune. Archived from the original on 31 October 2020. Retrieved 16 April 2017.

- ^ a b Khan, Muhammad Chingiz (15 July 2017). "Is MLA Ashab Uddin a local Manipuri?". Tehelka. 14: 36–38.

- ^ roughly 163 million in Bangladesh and 100 million in India (CIA Factbook 2014 estimates, numbers subject to rapid population growth); about 3 million Bangladeshis in the Middle East, 2 million Bengalis in Pakistan, 0.4 million British Bangladeshi.

- ^ "Bengali - Worldwide distribution". Worlddata.info. Retrieved 7 January 2024.

- ^ "50th Report of the Commissioner for Linguistic Minorities in India" (PDF). nclm.nic.in. Ministry of Minority Affairs. Archived from the original (PDF) on 8 July 2016. Retrieved 2 November 2018.

- ^ a b c McDermott, Rachel Fell (2005). "Bengali religions". In Lindsay Jones (ed.). Encyclopedia of Religion. Vol. 2 (2nd ed.). MacMillan Reference USA. p. 826. ISBN 0-02-865735-7.

- ^ a b Frawley, David (18 October 2018). What Is Hinduism?: A Guide for the Global Mind. Bloomsbury Publishing. pp. 26. ISBN 978-93-88038-65-2.

- ^ a b Tagore, Rabindranath (1916). The Home and the World ঘরে বাইরে [The Home and the World] (in Bengali). Dover Publications. p. 320.

- ^ Ghosh, Binay (2010) [1957]. Pashchimbanger Samskriti [The Culture of West Bengal] (in Bengali). Vol. 1 (2nd ed.). Kolkata: Prakash Bhawan. pp. 447–449.

- ^ Thaker, Jayant Premshankar, ed. (1970). Laghuprabandhasaṅgrahah. Oriental Institute. p. 111.

- ^ a b Ghulam Husain Salim (1902). RIYAZU-S-SALĀTĪN: A History of Bengal. Calcutta: The Asiatic Society. Archived from the original on 15 December 2014.

- ^ Firishta (1768). Dow, Alexander (ed.). History of Hindostan. pp. 7–9.

- ^ Trautmann, Thomas (2005). Aryans and British India. Yoda Press. p. 53.

- ^ Friedberg, Arthur L.; Friedberg, Ira S. (12 April 2025). Gold coins of the World. Coin & Currency Institute. ISBN 978-0-87184-308-1.

- ^ "Copperplates". Banglapedia. Retrieved 12 April 2025.

- ^ Keay, John (2000). India: A History. Atlantic Monthly Press. p. 220. ISBN 978-0-87113-800-2.

In C1020 ... launched Rajendra's great northern escapade ... peoples he defeated have been tentatively identified ... 'Vangala-desa where the rain water never stopped' sounds like a fair description of Bengal in the monsoon.

- ^ Sen, Sailendra Nath (1999) [First published 1988]. Ancient Indian History and Civilization. New Age International. p. 281. ISBN 978-81-224-1198-0.

- ^ Land of Two Rivers, Nitish Sengupta

- ^ a b Ahmed, ABM Shamsuddin (2012). "Iliyas Shah". In Sirajul Islam; Miah, Sajahan; Khanam, Mahfuza; Ahmed, Sabbir (eds.). Banglapedia: the National Encyclopedia of Bangladesh (Online ed.). Dhaka, Bangladesh: Banglapedia Trust, Asiatic Society of Bangladesh. ISBN 984-32-0576-6. OCLC 52727562. OL 30677644M. Retrieved 29 October 2025.

- ^ a b "What is more significant, a contemporary Chinese traveler reported that although Persian was understood by some in the court, the language in universal use there was Bengali. This points to the waning, although certainly not yet the disappearance, of the sort of foreign mentality that the Muslim ruling class in Bengal had exhibited since its arrival over two centuries earlier. It also points to the survival, and now the triumph, of local Bengali culture at the highest level of official society." (Eaton 1993:60)

- ^ a b Rabbani, AKM Golam (7 November 2017). "Politics and Literary Activities in the Bengali Language during the Independent Sultanate of Bengal". Dhaka University Journal of Linguistics. 1 (1): 151–166. Archived from the original on 11 October 2017. Retrieved 7 November 2017 – via www.banglajol.info.

- ^ Murshid, Ghulam (2012). "Bangali Culture". In Sirajul Islam; Miah, Sajahan; Khanam, Mahfuza; Ahmed, Sabbir (eds.). Banglapedia: the National Encyclopedia of Bangladesh (Online ed.). Dhaka, Bangladesh: Banglapedia Trust, Asiatic Society of Bangladesh. ISBN 984-32-0576-6. OCLC 52727562. OL 30677644M. Retrieved 29 October 2025.

- ^ Chattopadhyay et al. 2013, p. 97.

- ^ "Pandu Rajar Dhibi". Banglapedia. Retrieved 27 March 2024.

- ^ "4000-year old settlement unearthed in Bangladesh". Xinhua. 12 March 2006. Archived from the original on 10 May 2007.

- ^ Gourav Debnath (2022). "South Asian History, Culture and Archaeology - "The Evolution of Stone Tool Technology of Pre-Historic West Bengal: A Renewed Archaeological Approach"" (PDF). ESI Journals. 2. ESI Publications: 55–67. Retrieved 9 August 2023.

- ^ "History of Bangladesh". Bangladesh Student Association @ TTU. Archived from the original on 26 December 2005. Retrieved 26 October 2006.

- ^ Gautam Basumallik (30 March 2015). ৪২০০০ বছর আগে অযোধ্যা পাহাড় অঞ্চলে জনবসবাসের নিদর্শন মিলেছে [42,000 years ago, evidence of human habitation has been found in the Ayodhya Hills region]. Ei Samay (Editorial) (in Bengali). Retrieved 26 March 2024.

- ^ Bishnupriya Basak; Pradeep Srivastava; Sujit Dasgupta; Anil Kumar; S. N. Rajaguru (10 October 2014). "Earliest dates and implications of Microlithic industries of Late Pleistocene from Mahadebbera and Kana, Purulia district, West Bengal". Current Science. 107: 1167–1171.

- ^ Sebanti Saarkar (21 October 2014). "Bengal just got older by 22000 yrs". The Telegraph. India. Retrieved 26 March 2024.

- ^ Sebanti Sarkar (27 March 2008). "History of Bengal just got a lot older". The Telegraph. India. Retrieved 26 March 2024.

- ^ Sen et al. & September 2015, p. 19.

- ^ Rahman, Mizanur; Castillo, Cristina Cobo; Murphy, Charlene; Rahman, Sufi Mostafizur; Fuller, Dorian Q. (2020). "Agricultural systems in Bangladesh: the first archaeobotanical results from Early Historic Wari-Bateshwar and Early Medieval Vikrampura". Archaeological and Anthropological Sciences. 12 (1). Springer Science and Business Media LLC: 37. Bibcode:2020ArAnS..12...37R. doi:10.1007/s12520-019-00991-5. ISSN 1866-9557. PMC 6962288. PMID 32010407.

- ^ Rahman, SS Mostafizur. "Wari-Bateshwar". Banglapedia. Dhaka: Asiatic Society of Bangladesh. Retrieved 26 March 2024.

- ^ a b Sen et al. & September 2015, p. 59.

- ^ Sen et al. & September 2015, p. 28.

- ^ বেলাব উপজেলার পটভূমি [Belabo Upazila's Background]. Belabo Upazila (in Bengali). Archived from the original on 30 September 2021. Retrieved 24 February 2022.

- ^ (Eaton 1993)

- ^ Chowdhury, AM (2012). "Gangaridai". In Sirajul Islam; Miah, Sajahan; Khanam, Mahfuza; Ahmed, Sabbir (eds.). Banglapedia: the National Encyclopedia of Bangladesh (Online ed.). Dhaka, Bangladesh: Banglapedia Trust, Asiatic Society of Bangladesh. ISBN 984-32-0576-6. OCLC 52727562. OL 30677644M. Retrieved 29 October 2025.

- ^ Bhattacharyya, PK (2012). "Shashanka". In Sirajul Islam; Miah, Sajahan; Khanam, Mahfuza; Ahmed, Sabbir (eds.). Banglapedia: the National Encyclopedia of Bangladesh (Online ed.). Dhaka, Bangladesh: Banglapedia Trust, Asiatic Society of Bangladesh. ISBN 984-32-0576-6. OCLC 52727562. OL 30677644M. Retrieved 29 October 2025.

- ^ Sinha, Bindeshwari Prasad (1977). Dynastic History of Magadha. India: Abhinav Publications. pp. 131–133. Archived from the original on 18 November 2022. Retrieved 16 September 2019.

- ^ Insight, Apa Productions (November 1988). South Asia. APA Publications. p. 317.

- ^ Sen, Sailendra Nath (1999) [First published 1988]. Ancient Indian History and Civilization. New Age International. pp. 277–. ISBN 978-81-224-1198-0.

- ^ Raj Kumar (2003). Essays on Ancient India. Discovery Publishing House. p. 199. ISBN 978-81-7141-682-0.

- ^ Al-Masudi, trans. Barbier de Meynard and Pavet de Courteille (1962). "1:155". In Pellat, Charles (ed.). Les Prairies d'or [Murūj al-dhahab] (in French). Paris: Société asiatique.

- ^ Abdul Karim (2012). "Islam, Bengal". In Sirajul Islam; Miah, Sajahan; Khanam, Mahfuza; Ahmed, Sabbir (eds.). Banglapedia: the National Encyclopedia of Bangladesh (Online ed.). Dhaka, Bangladesh: Banglapedia Trust, Asiatic Society of Bangladesh. ISBN 984-32-0576-6. OCLC 52727562. OL 30677644M. Retrieved 29 October 2025.

- ^ Qurashi, Ishfaq (December 2012). "বুরহান উদ্দিন ও নূরউদ্দিন প্রসঙ্গ" [Burhan Uddin and Nooruddin]. শাহজালাল(রঃ) এবং শাহদাউদ কুরায়শী(রঃ) [Shah Jalal and Shah Dawud Qurayshi] (in Bengali).

- ^ Misra, Neeru (2004). Sufis and Sufism: Some Reflections. Manohar Publishers & Distributors. p. 103. ISBN 978-81-7304-564-6.

- ^ 'Abd al-Haqq al-Dehlawi. Akhbarul Akhyar.

- ^ Abdul Karim (2012). "Shaikh Akhi Sirajuddin Usman (R)". In Sirajul Islam; Miah, Sajahan; Khanam, Mahfuza; Ahmed, Sabbir (eds.). Banglapedia: the National Encyclopedia of Bangladesh (Online ed.). Dhaka, Bangladesh: Banglapedia Trust, Asiatic Society of Bangladesh. ISBN 984-32-0576-6. OCLC 52727562. OL 30677644M. Retrieved 29 October 2025.

- ^ Hanif, N (2000). Biographical Encyclopaedia of Sufis: South Asia. Prabhat Kumar Sharma, for Sarup & Sons. p. 35.

- ^ Taifoor, Syed Muhammed (1965). Glimpses of Old Dhaka (2 ed.). S.M. Perwez. pp. 104, 296.

- ^ Chattopadhyay, Bhaskar (1988). Culture of Bengal: Through the Ages: Some Aspects. University of Burdwan. pp. 210–215.

- ^ Steel, Tim (19 December 2014). "The paradise of nations". Op-ed. Dhaka Tribune. Archived from the original on 17 May 2019. Retrieved 17 May 2019.

- ^ Islam, Sirajul (1992). History of Bangladesh, 1704–1971: Economic history. Asiatic Society of Bangladesh. ISBN 978-984-512-337-2. Archived from the original on 18 November 2022. Retrieved 5 July 2021.

- ^ M. Shahid Alam (2016). Poverty From The Wealth of Nations: Integration and Polarization in the Global Economy since 1760. Springer Science+Business Media. p. 32. ISBN 978-0-333-98564-9. Archived from the original on 18 November 2022. Retrieved 16 May 2021.

- ^ Prakash, Om (2006). "Empire, Mughal". In McCusker, John J. (ed.). History of World Trade Since 1450. Vol. 1. Macmillan Reference USA. pp. 237–240. ISBN 0-02-866070-6. Archived from the original on 18 November 2022. Retrieved 3 August 2017.

- ^ Indrajit Ray (2011). Bengal Industries and the British Industrial Revolution (1757–1857). Routledge. pp. 57, 90, 174. ISBN 978-1-136-82552-1. Archived from the original on 18 November 2022. Retrieved 16 May 2021.

- ^ Junie T. Tong (2016). Finance and Society in 21st Century China: Chinese Culture Versus Western Markets. CRC Press. p. 151. ISBN 978-1-317-13522-7.

- ^ Esposito, John L., ed. (2004). "Great Britain". The Islamic World: Past and Present. Vol. 1. Oxford University Press. p. 174. ISBN 978-0-19-516520-3. Archived from the original on 16 January 2023. Retrieved 16 May 2021.

The sale of exports from these regions helped to support the Industrial Revolution in Britain

- ^ a b Indrajit Ray (2011). Bengal Industries and the British Industrial Revolution (1757-1857). Routledge. pp. 7–10. ISBN 978-1-136-82552-1. Archived from the original on 18 November 2022. Retrieved 20 January 2019.

- ^ a b Nitish Sengupta (2001). History of the Bengali-speaking People. UBS Publishers' Distributors. p. 211. ISBN 978-81-7476-355-6.

The Bengal Renaissance can be said to have started with Raja Ram Mohan Roy (1775-1833) and ended with Rabindranath Tagore (1861-1941).

- ^ Hasan, Farhat (1991). "Conflict and Cooperation in Anglo-Mughal Trade Relations during the Reign of Aurangzeb". Journal of the Economic and Social History of the Orient. 34 (4): 351–360. doi:10.1163/156852091X00058. JSTOR 3632456.

- ^ Vaugn, James (September 2017). "John Company Armed: The English East India Company, the Anglo-Mughal War and Absolutist Imperialism, c. 1675–1690". Britain and the World. 11 (1).

- ^ Baten, Jörg (2016). A History of the Global Economy. From 1500 to the Present. Cambridge University Press. p. 251. ISBN 978-1-107-50718-0.

- ^ Georg, Feuerstein (2002). The Yoga Tradition. Motilal Banarsidass. p. 600. ISBN 978-3-935001-06-9.

- ^ Clarke, Peter Bernard (2006). New Religions in Global Perspective. Routledge. p. 209. ISBN 978-0-7007-1185-7.

- ^ a b Soman, Priya. "Raja Ram Mohan and the Abolition of Sati System in India" (PDF). International Journal of Humanities, Art and Social Studies. 1 (2): 75–82. Archived (PDF) from the original on 12 July 2018. Retrieved 18 June 2021.

- ^ Source: The Gazetteer of India, Volume 1: Country and people. Delhi, Publications Division, Government of India, 1965. CHAPTER VIII – Religion. HINDUISM by C.P.Ramaswami Aiyar, Nalinaksha Dutt, A.R.Wadia, M.Mujeeb, Dharm Pal and Fr. Jerome D'Souza, S.J.

- ^ Syed, M. H. "Raja Rammohan Roy" (PDF). Himalaya Publishing House. Archived (PDF) from the original on 8 December 2015. Retrieved 29 November 2015.

- ^ "Bānlādēśakē jānuna" জানুন [Discover Bangladesh] (in Bengali). National Web Portal of Bangladesh. Archived from the original on 16 February 2015. Retrieved 13 February 2015.

- ^ Kumar, Jayant. Census of India. 2001. 4 September 2006. Indian Census Archived 19 June 2006 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "The state of human development" (PDF). Tripura human development report 2007. Government of Tripura. 2007. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2 May 2013. Retrieved 19 March 2012.

- ^ Karmakar, Rahul (27 October 2018). "Tripura, where demand for Assam-like NRC widens gap between indigenous people and non-tribal settlers". The Hindu. Archived from the original on 9 November 2020. Retrieved 27 June 2021.

- ^ Shekhar, Sidharth (19 April 2019). "When Indira Gandhi said: Refugees of all religions must go back". Times Now news. Archived from the original on 23 January 2021. Retrieved 27 June 2021.

- ^ Sekhsaria, Pankaj. "How a statist vision of development has brought Andaman's tribals close to extinction". Scroll.in. Archived from the original on 29 November 2020. Retrieved 21 November 2020.

- ^ Lorea, Carola Erika (2017). "Bengali settlers in the Andaman Islands: the performance of homeland". International Institute for Asian Studies. Archived from the original on 24 June 2021. Retrieved 19 June 2021.

- ^ "Crossing the Kala Pani to Britain for Hindu Workers and Elites". American Historical Association. 4 January 2012. Archived from the original on 26 February 2015. Retrieved 2 February 2012.

- ^ Majid, Razia (1987). শতাব্দীর সূর্য শিখা [The solar flame of the century] (in Bengali). Islamic Foundation Bangladesh. pp. 45–48.

- ^ The Muslim Society and Politics in Bengal, A.D. 1757–1947. University of Dacca. 1978. p. 76.

Maulana Murad, a Bengali domicile

- ^ Rahman, Md. Matiur; Bhuiya, Abdul Musabbir (2009). Teaching of Arabic language in Barak Valley: a historical study (14th to 20th century) (PDF). Silchar: Assam University. pp. 59–60. Archived (PDF) from the original on 26 March 2023. Retrieved 30 December 2022.

- ^ "Majlis El Hassan :: Sarvath El Hassan :: Biography". Archived from the original on 19 July 2011. Retrieved 25 May 2017.

- ^ C.E. Buckland, Dictionary of Indian Biography, Haskell House Publishers Ltd, 1968, p.217

- ^ Colebrooke, Thomas Edward (2011) [1884]. "First Start in Diplomacy". Life of the Honourable Mountstuart Elphinstone. Cambridge University Press. pp. 34–35. ISBN 978-1-108-09722-2. Archived from the original on 18 November 2022. Retrieved 16 May 2021.

- ^ Khaleeli, Homa (8 January 2012). "The curry crisis". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 16 May 2021. Retrieved 16 May 2021.

- ^ "...Comparing seven Indo-Aryan languages – Hindi, Punjabi, Sindhi, Gujarati, Marathi, Oriya and Bengali – are also significant contributions to New Indo-Aryan (NIA) studies.(Cardona 2007:627)

- ^ "Statistical Summaries". Ethnologue. 2012. Archived from the original on 2 February 2013. Retrieved 23 May 2012.

- ^ Huq, Mohammad Daniul; Sarkar, Pabitra (2012). "Bangla Language". In Sirajul Islam; Miah, Sajahan; Khanam, Mahfuza; Ahmed, Sabbir (eds.). Banglapedia: the National Encyclopedia of Bangladesh (Online ed.). Dhaka, Bangladesh: Banglapedia Trust, Asiatic Society of Bangladesh. ISBN 984-32-0576-6. OCLC 52727562. OL 30677644M. Retrieved 29 October 2025.

- ^ "Within the Eastern Indic language family the history of the separation of Bangla from Odia, Assamese, and the languages of Bihar remains to be worked out carefully. Scholars do not yet agree on criteria for deciding if certain tenth century AD texts were in a Bangla already distinguishable from the other languages, or marked a stage at which Eastern Indic had not finished differentiating." (Cardona 2007:352)

- ^ Bari, Sarah Anjum (12 April 2019). "A Tale of Two Languages: How the Persian language seeped into Bengali". The Daily Star (Bangladesh). Archived from the original on 21 June 2020. Retrieved 25 June 2021.

- ^ Tanweer Fazal (2012). Minority Nationalisms in South Asia: 'We are with culture but without geography': locating Sylheti identity in contemporary India, Nabanipa Bhattacharjee. pp.59–67.

- ^ A community without aspirations Archived 7 October 2019 at the Wayback Machine Zia Haider Rahman. 2 May 2007. Retrieved on 7 March 2018.

- ^ Marginal Muslim Communities in India edited by M.K.A Siddiqui pages 295-305

- ^ Mahabharata (12.181)

- ^ Hiltebeitel, Alf (2011). Dharma : its early history in law, religion, and narrative. Oxford University Press. pp. 529–531.ISBN 978-0-19-539423-8

- ^ Datta, Romita (13 November 2020). "The great Hindu vote trick". India Today. Archived from the original on 17 February 2023. Retrieved 4 October 2022.

Hindus add up to about 70 million in Bengal's 100 million population, of which around 55 million are Bengalis.

- ^ Ali, Zamser (5 December 2019). "EXCLUSIVE: BJP Govt plans to evict 70 lakh Muslims, 60 lakh Bengali Hindus through its Land Policy (2019) in Assam". Sabrang Communications. Archived from the original on 3 October 2022. Retrieved 4 October 2022.

Hence, about 70 lakh Assamese Muslims and 60 lakh Bengali-speaking Hindus face mass evictions and homelessness if the policy is allowed to be passed in the Assembly.

- ^ "Census 2022: Number of Muslims increased in the country". Dhaka Tribune. 27 July 2022. Archived from the original on 26 March 2023. Retrieved 1 October 2022.

- ^ a b McDermott, Rachel Fell (2005). "Bengali religions". In Lindsay Jones (ed.). Encyclopedia of Religion. Vol. 2 (2nd ed.). MacMillan Reference USA. p. 824. ISBN 0-02-865735-7.

- ^ 2014 US Department of State estimates

- ^ Comparing State Polities: A Framework for Analyzing 100 Governments By Michael J. III Sullivan, pg. 119

- ^ "Bangladesh 2015 International Religious Freedom Report" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 14 November 2020. Retrieved 30 December 2019.

- ^ Andre, Aletta; Kumar, Abhimanyu (23 December 2016). "Protest poetry: Assam's Bengali Muslims take a stand". Aljazeera. Aljazeera. Archived from the original on 2 February 2017. Retrieved 26 January 2017.

Total Muslim population in Assam is 34.22% of which 90% are Bengali Muslims according to this source which puts the Bengali Muslim percentage in Assam as 29.08%

- ^ a b Bangladesh Archived 30 July 2021 at the Wayback Machine- CIA World Factbook

- ^ a b "C-1 Population By Religious Community – West Bengal". census.gov.in. Archived from the original on 25 August 2015. Retrieved 2 December 2019.

- ^ Population by religious community: West Bengal Archived 10 September 2016 at the Wayback Machine. 2011 Census of India.

- ^ "Assam Assembly Election 2021: In Barak Valley, Congress battles religious fault lines; local factors bother BJP-India News". Firstpost. April 2021. Archived from the original on 4 September 2022. Retrieved 14 September 2022.

- ^ "BJP eyes 2.2 m Bengali Hindus in Tripura quest". Daily Pioneer. Archived from the original on 14 September 2022. Retrieved 14 September 2022.

- ^ Sengupta 2002, p. 98.