Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Trade union

View on Wikipedia

| Part of a series on |

| Organized labour |

|---|

|

A trade union (British English) or labor union (American English), often simply referred to as a union, is an organization of workers whose purpose is to maintain or improve the conditions of their employment,[1] such as attaining better wages and benefits, improving working conditions, improving safety standards, establishing complaint procedures, developing rules governing status of employees (rules governing promotions, just-cause conditions for termination) and protecting and increasing the bargaining power of workers.

Trade unions typically fund their head office and legal team functions through regularly imposed fees called union dues. The union representatives in the workforce are usually made up of workplace volunteers who are often appointed by members through internal democratic elections. The trade union, through an elected leadership and bargaining committee, bargains with the employer on behalf of its members, known as the rank and file, and negotiates labour contracts (collective bargaining agreements) with employers.

Unions may organize a particular section of skilled or unskilled workers (craft unionism),[2] a cross-section of workers from various trades (general unionism), or an attempt to organize all workers within a particular industry (industrial unionism). The agreements negotiated by a union are binding on the rank-and-file members and the employer, and in some cases on other non-member workers. Trade unions traditionally have a constitution which details the governance of their bargaining unit and also have governance at various levels of government depending on the industry that binds them legally to their negotiations and functioning.

Originating in the United Kingdom, trade unions became popular in many countries during the Industrial Revolution when employment (rather than subsistence farming) became the primary mode of earning a living. Trade unions may be composed of individual workers, professionals, past workers, students, apprentices or the unemployed. Trade union density, or the percentage of workers belonging to a trade union, is highest in the Nordic countries.[3][4]

Definition

[edit]

Since the publication of the History of Trade Unionism (1894) by Sidney and Beatrice Webb, the predominant historical view is that a trade union "is a continuous association of wage earners for the purpose of maintaining or improving the conditions of their employment".[1] Karl Marx described trade unions thus: "The value of labour-power constitutes the conscious and explicit foundation of the trade unions, whose importance for the ... working class can scarcely be overestimated. The trade unions aim at nothing less than to prevent the reduction of wages below the level that is traditionally maintained in the various branches of industry. That is to say, they wish to prevent the price of labour-power from falling below its value" (Capital V1, 1867, p. 1069). Early socialists also saw trade unions as a way to democratize the workplace, in order to obtain political power.[5]

A modern definition by the Australian Bureau of Statistics states that a trade union is "an organisation consisting predominantly of employees, the principal activities of which include the negotiation of rates of pay and conditions of employment for its members".[6]

Recent historical research by Bob James puts forward the view that trade unions are part of a broader movement of benefit societies, which includes medieval guilds, Freemasons, Oddfellows, friendly societies, and other fraternal organizations.[7]

History

[edit]Trade guilds

[edit]A collegium was any association in ancient Rome that acted as a legal entity. Following the passage of the Lex Julia during the reign of Julius Caesar (49–44 BC), and their reaffirmation during the reign of Caesar Augustus (27 BC–14 AD), collegia required the approval of the Roman Senate or the Roman emperor in order to be authorized as legal bodies.[8] Ruins at Lambaesis date the formation of burial societies among Roman Army soldiers and Roman Navy mariners to the reign of Septimius Severus (193–211) in 198 AD.[9] In September 2011, archaeological investigations done at the site of the artificial harbor Portus in Rome revealed inscriptions in a shipyard constructed during the reign of Trajan (98–117) indicating the existence of a shipbuilders guild.[10] Rome's La Ostia port was home to a guildhall for a corpus naviculariorum, a collegium of merchant mariners.[11] Collegium also included fraternities of Roman priests overseeing Sacrificium Romanam (ritual sacrifices), practising augury, keeping scriptures, arranging festivals, and maintaining specific religious cults.[12]

Modern trade unions

[edit]While a commonly held mistaken view holds modern trade unionism to be a product of Marxism, the earliest modern trade unions predate Marx's Communist Manifesto (1848) by almost a century (and Marx's writings themselves frequently address the prior existence of the workers' movements of his time.) The first recorded labour strike in the United States was by Philadelphia printers in 1786, who opposed a wage reduction and demanded $6 per week in wages.[13][14] The origins of modern trade unions can be traced back to 18th-century Britain, where the Industrial Revolution drew masses of people, including dependents, peasants and immigrants, into cities. Britain had ended the practice of serfdom in 1574, but the vast majority of people remained as tenant-farmers on estates owned by the landed aristocracy. This transition was not merely one of relocation from rural to urban environs; rather, the nature of industrial work created a new class of "worker". A farmer worked the land, raised animals and grew crops, and either owned the land or paid rent, but ultimately sold a product and had control over his life and work. As industrial workers, however, the workers sold their work as labour and took directions from employers, giving up part of their freedom and self-agency in the service of a master. The critics of the new arrangement would call this "wage slavery",[15] but the term that persisted was a new form of human relations: employment. Unlike farmers, workers often had less control over their jobs; without job security or a promise of an on-going relationship with their employers, they lacked some control over the work they performed or how it impacted their health and life. It is in this context that modern trade unions emerge.

In the cities, trade unions encountered much hostility from employers and government groups. In the United States, unions and unionists were regularly prosecuted under various restraint of trade and conspiracy laws, such as the Sherman Antitrust Act.[16][17] This pool of unskilled and semi-skilled labour spontaneously organized in fits and starts throughout its beginnings,[1] and would later be an important arena for the development of trade unions. Trade unions have sometimes been seen as successors to the guilds of medieval Europe, though the relationship between the two is disputed, as the masters of the guilds employed workers (apprentices and journeymen) who were not allowed to organize.[18][19]

Trade unions and collective bargaining were outlawed from no later than the middle of the 14th century, when the Ordinance of Labourers was enacted in the Kingdom of England, but their way of thinking was the one that endured down the centuries, inspiring evolutions and advances in thinking which eventually gave workers more power. As collective bargaining and early worker unions grew with the onset of the Industrial Revolution, the government began to clamp down on what it saw as the danger of popular unrest at the time of the Napoleonic Wars. In 1799, the Combination Act was passed, which banned trade unions and collective bargaining by British workers. Although the unions were subject to often severe repression until 1824, they were already widespread in cities such as London. Workplace militancy had also manifested itself as Luddism and had been prominent in struggles such as the 1820 Rising in Scotland, in which 60,000 workers went on a general strike, which was soon crushed. Sympathy for the plight of the workers brought repeal of the acts in 1824, although the Combination Act 1825 restricted their activity to bargaining for wage increases and changes in working hours.[20]

By the 1810s, the first labour organizations to bring together workers of divergent occupations were formed. Possibly the first such union was the General Union of Trades, also known as the Philanthropic Society, founded in 1818 in Manchester. The latter name was to hide the organization's real purpose in a time when trade unions were still illegal.[21]

National general unions

[edit]

The first attempts at forming a national general union in the United Kingdom were made in the 1820s and 30s. The National Association for the Protection of Labour was established in 1830 by John Doherty, after an apparently unsuccessful attempt to create a similar national presence with the National Union of Cotton-spinners. The Association quickly enrolled approximately 150 unions, consisting mostly of Textile and clothing trade unions|textile related unions, but also including mechanics, blacksmiths, and various others. Membership rose to between 10,000 and 20,000 individuals spread across the five counties of Lancashire, Cheshire, Derbyshire, Nottinghamshire and Leicestershire within a year.[22] To establish awareness and legitimacy, the union started the weekly Voice of the People publication, having the declared intention "to unite the productive classes of the community in one common bond of union."[23]

In 1834, the Welsh socialist Robert Owen established the Grand National Consolidated Trades Union. The organization attracted a range of socialists from Owenites to revolutionaries and played a part in the protests after the Tolpuddle Martyrs' case, but soon collapsed.

More permanent trade unions were established from the 1850s, better resourced but often less radical. The London Trades Council was founded in 1860, and the Sheffield Outrages spurred the establishment of the Trades Union Congress in 1868, the first long-lived national trade union center. By this time, the existence and the demands of the trade unions were becoming accepted by liberal middle-class opinion. In Principles of Political Economy (1871) John Stuart Mill wrote:

If it were possible for the working classes, by combining among themselves, to raise or keep up the general rate of wages, it needs hardly be said that this would be a thing not to be punished, but to be welcomed and rejoiced at. Unfortunately the effect is quite beyond attainment by such means. The multitudes who compose the working class are too numerous and too widely scattered to combine at all, much more to combine effectually. If they could do so, they might doubtless succeed in diminishing the hours of labour, and obtaining the same wages for less work. They would also have a limited power of obtaining, by combination, an increase of general wages at the expense of profits.[24]

Beyond this claim, Mill also argued that, because individual workers had no basis for assessing the wages for a particular task, labour unions would lead to greater efficiency of the market system.[25]

Legalization, expansion and recognition

[edit]

British trade unions were finally legalized in 1872, after a Royal Commission on Trade Unions in 1867 agreed that the establishment of the organizations was to the advantage of both employers and employees.

This period also saw the growth of trade unions in other industrializing countries, especially the United States, Germany and France.

In the United States, the first effective nationwide labour organization was the Knights of Labor, in 1869, which began to grow after 1880. Legalization occurred slowly as a result of a series of court decisions.[26] The Federation of Organized Trades and Labor Unions began in 1881 as a federation of different unions that did not directly enrol workers. In 1886, it became known as the American Federation of Labor or AFL.

In Germany, the Free Association of German Trade Unions was formed in 1897 after the conservative Anti-Socialist Laws of Chancellor Otto von Bismarck were repealed.

In France, labour organisation was illegal until the 1884 Waldeck Rousseau laws. The Fédération des bourses du travail was founded in 1887 and merged with the Fédération nationale des syndicats (National Federation of Trade Unions) in 1895 to form the General Confederation of Labour.

In a number of countries during the 20th century, including in Canada, the United States and the United Kingdom, legislation was passed to provide for the voluntary or statutory recognition of a union by an employer.[27][28][29]

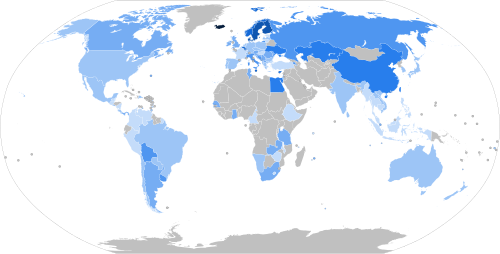

Prevalence worldwide

[edit]

Union density has been steadily declining from the OECD average of 35.9% in 1998 to 27.9% in the year 2018.[3] The main reasons for these developments are a decline in manufacturing, increased globalization, and governmental policies.

The decline in manufacturing is the most direct influence, as unions were historically beneficial and prevalent in the sector; for this reason, there may be an increase in developing nations as OECD nations continue to export manufacturing industries to these markets. The second reason is globalization, which makes it harder for unions to maintain standards across countries. The last reason is governmental policies. These come from both sides of the political spectrum. In the UK and US, it has been mostly right-wing proposals that make it harder for unions to form or that limit their power. On the other side, there are many social policies such as minimum wage, paid vacation, parental leave, etc., that decrease the need to be in a union.[30]

The prevalence of labour unions can be measured by "union density", which is expressed as a percentage of the total number of workers in a given location who are trade union members.[31] The table below shows the percentage across OECD members.[3]

| Country | 2020 | 2018 | 2017 | 2016 | 2015 | 2000 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Australia | .. | 13.7 | 14.7 | .. | .. | 24.9 |

| Austria | .. | 26.3 | 26.7 | 26.9 | 27.4 | 36.9 |

| Belgium | .. | 50.3 | 51.9 | 52.8 | 54.2 | 56.6 |

| Canada | 27.2 | 25.9 | 26.3 | 26.3 | 29.4 | 28.2 |

| Chile | .. | 16.6 | 17.0 | 17.7 | 16.1 | 11.2 |

| Czech Republic | .. | 11.5 | 11.7 | 12.0 | 12.0 | 27.2 |

| Denmark | .. | 66.5 | 66.1 | 65.5 | 67.1 | 74.5 |

| Estonia | .. | 4.3 | 4.3 | 4.4 | 4.7 | 14.0 |

| Finland | .. | 60.3 | 62.2 | 64.9 | 66.4 | 74.2 |

| France | .. | 8.8 | 8.9 | 9.0 | 9.0 | 10.8 |

| Germany | .. | 16.5 | 16.7 | 17.0 | 17.6 | 24.6 |

| Greece | .. | .. | .. | 19.0 | .. | .. |

| Hungary | .. | 7.9 | 8.1 | 8.5 | 9.4 | 23.8 |

| Iceland | 92.2 | 91.8 | 91.0 | 89.8 | 90.0 | 89.1 |

| Ireland | 26.2 | 24.1 | 24.3 | 23.4 | 25.4 | 35.9 |

| Israel | .. | .. | 25.0 | .. | .. | 37.7 |

| Italy | .. | 34.4 | 34.3 | 34.4 | 35.7 | 34.8 |

| Japan | .. | 17.0 | 17.1 | 17.3 | 17.4 | 21.5 |

| Korea | .. | .. | 10.5 | 10.0 | 10.0 | 11.4 |

| Latvia | .. | 11.9 | 12.2 | 12.3 | 12.6 | .. |

| Lithuania | .. | 7.1 | 7.7 | 7.7 | 7.9 | .. |

| Luxembourg | .. | 31.8 | 32.1 | 32.3 | 33.3 | .. |

| Mexico | 12.4 | 12.0 | 12.5 | 12.7 | 13.1 | 16.7 |

| Netherlands | .. | 16.4 | 16.8 | 17.3 | 17.7 | 22.3 |

| New Zealand | .. | .. | 17.3 | 17.7 | 17.9 | 22.4 |

| Norway | .. | 49.2 | 49.3 | 49.3 | 49.3 | 53.6 |

| Poland | .. | .. | .. | 12.7 | .. | 23.5 |

| Portugal | .. | .. | .. | 15.3 | 16.1 | .. |

| Slovak Republic | .. | .. | .. | 10.7 | 11.7 | 34.2 |

| Slovenia | .. | .. | .. | 20.4 | 20.9 | 44.2 |

| Spain | .. | 13.6 | 14.2 | 14.8 | 15.2 | 17.5 |

| Sweden | .. | 65.5 | 65.6 | 66.9 | 67.8 | 81.0 |

| Switzerland | .. | 14.4 | 14.9 | 15.3 | 15.7 | 20.7 |

| Turkey | .. | 9.2 | 8.6 | 8.2 | 8.0 | 12.5 |

| United Kingdom | .. | 23.4 | 23.2 | 23.7 | 24.2 | 29.8 |

| United States | 10.3 | 10.1 | 10.3 | 10.3 | 10.6 | 12.9 |

Structure and politics

[edit]

Unions may organize a particular section of skilled workers (craft unionism, traditionally found in Australia, Canada, Denmark, Norway, Sweden, Switzerland, the UK and the US[2]), a cross-section of workers from various trades (general unionism, traditionally found in Australia, Belgium, Canada, Denmark, Netherlands, the UK and the US), or attempt to organize all workers within a particular industry (industrial unionism, found in Australia, Canada, Germany, Finland, Norway, South Korea, Sweden, Switzerland, the UK and the US).[citation needed] These unions are often divided into "locals", and united in national federations. These federations themselves will affiliate with Internationals, such as the International Trade Union Confederation. However, in Japan, union organisation is slightly different due to the presence of enterprise unions, i.e. unions that are specific to a plant or company. These enterprise unions, however, join industry-wide federations which in turn are members of Rengo, the Japanese national trade union confederation.

In Western Europe, professional associations often carry out the functions of a trade union. In these cases, they may be negotiating for white-collar or professional workers, such as physicians, engineers or teachers. In Sweden the white-collar unions have a strong position in collective bargaining where they cooperate with blue-colar unions in setting the "mark" (the industry norm) in negotiations with the employers' association in manufacturing industry.[32][33]

A union may acquire the status of a "juristic person" (an artificial legal entity), with a mandate to negotiate with employers for the workers it represents. In such cases, unions have certain legal rights, most importantly the right to engage in collective bargaining with the employer (or employers) over wages, working hours, and other terms and conditions of employment. The inability of the parties to reach an agreement may lead to industrial action, culminating in either strike action or management lockout, or binding arbitration. In extreme cases, violent or illegal activities may develop around these events.

In some regions, unions may face active repression, either by governments or by extralegal organizations, with many cases of violence, some having led to deaths, having been recorded historically.[35]

Unions may also engage in broader political or social struggle. Social Unionism encompasses many unions that use their organizational strength to advocate for social policies and legislation favourable to their members or to workers in general. As well, unions in some countries are closely aligned with political parties. Many Labour parties were founded as the electoral arms of trade unions.

Unions are also delineated by the service model and the organizing model. The service model union focuses more on maintaining worker rights, providing services, and resolving disputes. Alternately, the organizing model typically involves full-time union organizers, who work by building up confidence, strong networks, and leaders within the workforce; and confrontational campaigns involving large numbers of union members. Many unions are a blend of these two philosophies, and the definitions of the models themselves are still debated. Informal workers often face unique challenges when trying to participate in trade union movements as formal trade union organizations recognized by the state and employers may not accommodate for the employment categories common in the informal economy. Simultaneously, the lack of regular work locations and loopholes relating to false self-employment add barriers and costs for the trade unions when trying to organize the informal economy. This has been a significant threshold to labour organizing in low-income countries, where the labour force mostly works in the informal economy.[36]

In the United Kingdom, the perceived left-leaning nature of trade unions (and their historical close alignment with the Labour Party) has resulted in the formation of a reactionary right-wing trade union called Solidarity which is supported by the far-right BNP. In Denmark, there are some newer apolitical "discount" unions who offer a very basic level of services, as opposed to the dominating Danish pattern of extensive services and organizing.[37]

In contrast, in several European countries (e.g. Belgium, Denmark, the Netherlands and Switzerland), religious unions have existed for decades. These unions typically distanced themselves from some of the doctrines of orthodox Marxism, such as the preference of atheism and from rhetoric suggesting that employees' interests always are in conflict with those of employers. Some of these Christian unions have had some ties to centrist or conservative political movements, and some do not regard strikes as acceptable political means for achieving employees' goals.[2] In Poland, the biggest trade union Solidarity emerged as an anti-communist movement with religious nationalist overtones[38] and today it supports the right-wing Law and Justice party.[39]

Although their political structure and autonomy varies widely, union leaderships are usually formed through democratic elections.[40] Some research, such as that conducted by the Australian Centre for Industrial Relations Research and Training,[41] argues that unionized workers enjoy better conditions and wages than those who are not unionized.

International unions

[edit]The oldest global trade union organizations include the World Federation of Trade Unions created in 1945.[42] The largest trade union federation in the world is the Brussels-based International Trade Union Confederation (ITUC), created in 2006,[43] which has approximately 309 affiliated organizations in 156 countries and territories, with a combined membership of 166 million. National and regional trade unions organizing in specific industry sectors or occupational groups also form global union federations, such as UNI Global, IndustriALL, the International Transport Workers' Federation, the International Federation of Journalists, the International Arts and Entertainment Alliance and Public Services International.

Labour law

[edit]Union law varies from country to country, as does the function of unions. For example, German and Dutch unions have played a greater role in management decisions through participation in supervisory boards and co-determination than other countries.[44] Moreover, in the United States, collective bargaining is most commonly undertaken by unions directly with employers, whereas in Austria, Denmark, Germany or Sweden, unions most often negotiate with employers associations, a form of sectoral bargaining.

Concerning labour market regulation in the EU, Gold (1993)[45] and Hall (1994)[46] have identified three distinct systems of labour market regulation, which also influence the role that unions play:

- "In the Continental European System of labour market regulation, the government plays an important role as there is a strong legislative core of employee rights, which provides the basis for agreements as well as a framework for discord between unions on one side and employers or employers' associations on the other. This model was said to be found in EU core countries such as Belgium, France, Germany, the Netherlands and Italy, and it is also mirrored and emulated to some extent in the institutions of the EU, due to the relative weight that these countries had in the EU until the EU expansion by the inclusion of 10 new Eastern European member states in 2004.

- In the Anglo-Saxon System of labour market regulation, the government's legislative role is much more limited, which allows for more issues to be decided between employers and employees and any union or employers' associations which might represent these parties in the decision-making process. However, in these countries, collective agreements are not widespread; only a few businesses and a few sectors of the economy have a strong tradition of finding collective solutions in labour relations. Ireland and the UK belong to this category, and in contrast to the EU core countries above, these countries first joined the EU in 1973.

- In the Nordic System of labour market regulation, the government's legislative role is limited in the same way as in the Anglo-Saxon system. However, in contrast to the countries in the Anglo-Saxon system category, this is a much more widespread network of collective agreements, which covers most industries and most firms. This model was said to encompass Denmark, Finland, Norway and Sweden. Here, Denmark joined the EU in 1973, whereas Finland and Sweden joined in 1995."[47]

The United States takes a more laissez-faire approach, setting some minimum standards but leaving most workers' wages and benefits to collective bargaining and market forces. Thus, it comes closest to the above Anglo-Saxon model. Also, the Eastern European countries that have recently entered into the EU come closest to the Anglo-Saxon model.

In contrast, in Germany, the relation between individual employees and employers is considered to be asymmetrical. In consequence, many working conditions are not negotiable due to a strong legal protection of individuals. However, the German flavor or works legislation has as its main objective to create a balance of power between employees organized in unions and employers organized in employers' associations. This allows much wider legal boundaries for collective bargaining, compared to the narrow boundaries for individual negotiations. As a condition to obtain the legal status of a trade union, employee associations need to prove that their leverage is strong enough to serve as a counterforce in negotiations with employers. If such an employee's association is competing against another union, its leverage may be questioned by unions and then evaluated in labour court. In Germany, only very few professional associations obtained the right to negotiate salaries and working conditions for their members, notably the medical doctor's association Marburger Bund and the pilots association Vereinigung Cockpit. The engineer's association Verein Deutscher Ingenieure does not strive to act as a union, as it also represents the interests of engineering businesses.[citation needed]

Beyond the classification listed above, unions' relations with political parties vary. In many countries unions are tightly bonded, or even share leadership, with a political party intended to represent the interests of the working class. Typically, this is a left-wing, socialist, or social democratic party, but many exceptions exist, including some of the aforementioned Christian unions.[2] In the United States, trade unions are almost always aligned with the Democratic Party with a few exceptions. For example, the International Brotherhood of Teamsters has supported Republican Party candidates on a number of occasions and the Professional Air Traffic Controllers Organization (PATCO) endorsed Ronald Reagan in 1980.[citation needed]

In the United Kingdom, the trade union movement's relationship with the Labour Party frayed as the party leadership embarked on privatization plans at odds with what unions see as the worker's interests. However, it strengthened after the Labour party's election of Ed Miliband, who defeated his brother David Miliband to become leader of the party. Additionally, in the past, there was a group known as the Conservative Trade Unionists, or CTU, formed of people who sympathized with right-wing Conservative policy but were Trade Unionists.[48]

Shop types

[edit]Companies that employ workers with a union generally operate on one of several models:

- A closed shop (US) or a "pre-entry closed shop" (UK) employs only people who are already union members. The compulsory hiring hall is an example of a closed shop—in this case the employer must recruit directly from the union, as well as the employee working strictly for unionized employers.

- A union shop (US) or a "post-entry closed shop" (UK) employs non-union workers as well but sets a time limit within which new employees must join a union.

- An agency shop requires non-union workers to pay a fee to the union for its services in negotiating their contract. This is sometimes called the Rand formula.

- An open shop does not require union membership in employing or keeping workers. Where a union is active, workers who do not contribute to a union may include those who approve of the union contract (free riders) and those who do not. In the United States, state level right-to-work laws mandate the open shop in some states. In Germany only open shops are legal; that is, all discrimination based on union membership is forbidden. This affects the function and services of the union.

An EU case concerning Italy stated that, "The principle of trade union freedom in the Italian system implies recognition of the right of the individual not to belong to any trade union ("negative" freedom of association/trade union freedom), and the unlawfulness of discrimination liable to cause harm to non-unionized employees."[49]

In the United Kingdom, previous to this EU jurisprudence, a series of laws introduced during the 1980s by Margaret Thatcher's government restricted closed and union shops. All agreements requiring a worker to join a union are now illegal. In the United States, the Taft–Hartley Act of 1947 outlawed the closed shop.

In 2006, the European Court of Human Rights found Danish closed-shop agreements to be in breach of Article 11 of the European Convention on Human Rights and Fundamental Freedoms. It was stressed that Denmark and Iceland were among a limited number of contracting states that continue to permit the conclusion of closed-shop agreements.[50]

Impact

[edit]The examples and perspective in this article deal primarily with the United States and do not represent a worldwide view of the subject. (October 2021) |

Economics

[edit]

The academic literature shows substantial evidence that trade unions reduce economic inequality.[52][53][54][55][56][57] The economist Joseph Stiglitz has asserted that, "Strong unions have helped to reduce inequality, whereas weaker unions have made it easier for CEOs, sometimes working with market forces that they have helped shape, to increase it." Evidence indicates that those who are not members of unions also see higher wages. Researchers suggest that unions set industrial norms as firms try to stop further unionization or losing workers to better-paying competitors.[57][56] The decline in unionization since the 1960s in the United States has been associated with a pronounced rise in income and wealth inequality and, since 1967, with loss of middle class income.[58][59][60][61] Right-to-work laws have been linked to greater economic inequality in the United States.[62][63]

Research from Norway has found that high unionization rates lead to substantial increases in firm productivity, as well as increases in workers' wages.[64] Research from Belgium also found productivity gains, although smaller.[65] However, other research in the United States has found that unions can harm profitability, employment and business growth rates.[66][67] UK research on employment, wages, productivity, and investment found union density improved all metrics - but only until a limit. Forming U-shaped curves, after an optimal density, more unionisation worsened employment, wages, etc.[68][69] Research from the Anglosphere indicates that unions can provide wage premiums and reduce inequality while reducing employment growth and restricting employment flexibility.[70] Some trade unions oppose approaches which increase productivity, such as automation.[71]

In the United States, the outsourcing of labour to Asia, Latin America, and Africa has been partially driven by increasing costs of union partnership, which gives other countries a comparative advantage in labour, making it more efficient to perform labour-intensive work there.[72] Trade unions have been accused of benefiting insider workers and those with secure jobs at the cost of outsider workers, consumers of the goods or services produced, and the shareholders of the unionized business.[73] Economist Milton Friedman sought to show that unionization produces higher wages (for the union members) at the expense of fewer jobs, and that, if some industries are unionized while others are not, wages will tend to decline in non-unionized industries.[74] Friedrich Hayek criticized unions in chapter 18 of his publication The Constitution of Liberty.[75]

Trade unions frequently advocate for seniority-based compensation and against meritocracy.[76]

Politics

[edit]In the United States, the weakening of unions has been linked to more favourable electoral outcomes for the Republican Party.[77][78][79] Legislators in areas with high unionization rates are more responsive to the interests of the poor, whereas areas with lower unionization rates are more responsive to the interests of the rich.[80] Higher unionization rates increase the likelihood of parental leave policies being adopted.[81] Republican-controlled states are less likely to adopt more restrictive labour policies when unions are strong in the state.[82]

Research in the United States found that American congressional representatives were more responsive to the interests of the poor in districts with higher unionization rates.[83] Another 2020 American study found an association between US state level adoption of parental leave legislation and trade union strength.[84]

In the United States, unions have been linked to lower racial resentment among whites.[85] Membership in unions increases political knowledge, in particular among those with less formal education.[86]

Public-sector trade unions have been associated with increased cost of government.[87]

Health

[edit]In the United States, higher union density has been associated with lower suicide/overdose deaths.[88] Decreased unionization rates in the United States have been linked to an increase in occupational fatalities.[89]

See also

[edit]- Critique of work

- Digital Product Passport

- Excess profits tax

- Global labor arbitrage

- Labor federation competition in the United States

- Labor Management Reporting and Disclosure Act

- Labour inspectorate

- List of trade unions

- Police union

- Profit margin

- Progressive Librarians Guild

- Project Labor Agreement

- Salt (union organizing)

- Union busting

- Workplace politics

References

[edit]- ^ a b c Webb & Webb 1920.

- ^ a b c d Poole, M., 1986. Industrial Relations: Origins and Patterns of National Diversity. London UK: Routledge.

- ^ a b c d "Trade Union". stats.oecd.org. Retrieved 11 May 2021.

- ^ "Industrial relations". ILOSTAT. Retrieved 9 October 2018.

- ^ Botz, Dan La (2013). "The Marxist View of the Labor Unions: Complex and Critical". WorkingUSA. 16 (1): 5–42. doi:10.1111/wusa.12021. ISSN 1743-4580.

- ^ "Trade Union Census". Australian Bureau of Statistics. Retrieved 27 July 2011.

- ^ James 2001.

- ^ de Ligt, L. (2001). "D. 47,22, 1, pr.-1 and the Formation of Semi-Public "Collegia"". Latomus. 60 (2): 346–349. ISSN 0023-8856. JSTOR 41539517.

- ^ Ginsburg, Michael (1940). "Roman military clubs and their social functions". Transactions and Proceedings of the American Philological Association. 71: 149–156. doi:10.2307/283119. JSTOR 283119.

- ^ Welsh, Jennifer (23 September 2011). "Huge Ancient Roman Shipyard Unearthed in Italy". Live Science. Future. Retrieved 23 June 2021.

- ^ Epstein, Steven A. (1995). Wage Labor and Guilds in Medieval Europe. Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina Press. pp. 10–49. ISBN 978-0807844984.

- ^ Lintott, Andrew (1999). The Constitution of the Roman Republic. Oxford: Oxford University Press. pp. 183–186. ISBN 978-0198150688.

- ^ Perlman, Selig (1922). A History of Trade Unionism in the United States. New York: MacMillan. pp. 1–3.

- ^ "Strike: Strikes in the United States". infoplease.com. Retrieved 9 August 2023.

- ^ Tomich, Dale W. (2004). Through the prism of slavery : labor, capital, and world economy. Lanham: Rowman & Littlefield. ISBN 1417503572. OCLC 55090137.

- ^ Clark, O. L. (January 1948). "Application of the Sherman Anti-Trust Act to Unions since the Apex Case". SMU Law Review. 1 (1): 94–103.

- ^ "Restraint of Trade. Sherman Anti-Trust Law. Liability of Labor Unions". Harvard Law Review. 21 (6): 450. 1908. doi:10.2307/1325438. JSTOR 1325438.

- ^ C. M. N. (3 March 1928). "The Guild and the Trade Union". The Age. p. 25 – via Google News Archive.

- ^ Kautsky, Karl (April 1901). "Trades Unions and Socialism". International Socialist Review. 1 (10). Retrieved 27 July 2011.

- ^ Frank, Christopher (January 2005). ""Let But One of Them Come before Me, and I'll Commit Him": Trade Unions, Magistrates, and the Law in Mid-Nineteenth-Century Staffordshire". Journal of British Studies. 44 (1): 76–77. doi:10.1086/426157. JSTOR 10.1086/426157.

- ^ Cole 2010, p. 3.

- ^ Webb, Sidney; Webb, Beatrice (1894). History of Trade Unionism. London: Longmans Green and Co. pp. 120–124.

- ^ Webb & Webb 1894, p. 122.

- ^ Principles of Political Economy (1871)Book V, Ch.10 Archived 6 November 2014 at the Wayback Machine, para. 5

- ^ King, John T.; Yanochik, Mark A. (2011). "John Stuart Mill and the Economic Rationale for Organized Labor". The American Economist. 56 (2): 28–34. doi:10.1177/056943451105600205. ISSN 0569-4345. JSTOR 23240389. S2CID 157935634.

- ^ "Trade union". Encyclopædia Britannica. 13 March 2024.

- ^ Townshend-Smith, R (1981). "Trade union recognition legislation – Britain and America compared". Legal Studies. 1 (2): 190–212. doi:10.1111/j.1748-121X.1981.tb00120.x. S2CID 145725063.

- ^ Briggs, C. (2007). "Statutory Union Recognition in North America and the UK: Lessons for Australia?". The Economic and Labour Relations Review. 17 (2): 77–97. doi:10.1177/103530460701700205. S2CID 153980466.

- ^ Goodard, J. (2013). "Labour Law and Union Recognition in Canada: A Historical-Institutionalist Perspective". Queen's Law Journal. 38 (2): 391–417.

- ^ E.H. (29 September 2015). "Why trade unions are declining". The Economist. ISSN 0013-0613. Retrieved 11 May 2021.

- ^ "Industrial relations" (PDF). International Labour Organisation. Archived from the original (PDF) on 9 October 2018. Retrieved 9 October 2018.

- ^ Kjellberg, Anders (2023) "Trade unions in Sweden: still high union density, but widening gaps by social category and national origin". In Jeremy Waddington & Torsten Mueller & Kurt Vandaele (eds.) Trade unions in the European Union. Picking up the pieces of the neoliberal challenge. Brussels: Peter Lang and Etui. Series: Travail et Société / Work and Society, Volume 86, 2023, chapter 28, pp. 1051–1092.

- ^ Kjellberg, Anders (2023) The Nordic Model of Industrial Relations: comparing Denmark, Finland, Norway and Sweden. Department of Sociology, Lund University and Max Planck Institute for the Study of Societies, Cologne.

- ^ "The 10 Biggest Strikes in American History Archived 2 December 2013 at the Wayback Machine". Fox Business. 9 August 2011

- ^ Amnesty International report 23 September 2005 – fear for safety of SINALTRAINAL member José Onofre Esquivel Luna

- ^ Schminke, Tobias Gerhard; Fridell, Gavin (2021). "Trade Union Transformation and Informal Sector Organising in Uganda: The Prospects and Challenges for Promoting Labour-led Development". Global Labour Movement. 12 (2). doi:10.15173/glj.v12i2.4394. Retrieved 24 July 2024.

- ^ "See the website of the Danish discount union "Det faglige Hus"". Danish.

- ^ Poland, Professor Jacek Tittenbrun of Poznan University (18 July 2005). "The economic and social processes that led to the revolt of the Polish workers in the early eighties". www.marxist.com. Retrieved 16 January 2018.

- ^ Solidarność popiera Kaczyńskiego jak kiedyś Wałęsę Archived 9 February 2014 at the Wayback Machine at news.money.pl (in Polish)

- ^ See E McGaughey, 'Democracy or Oligarchy? Models of Union Governance in the UK, Germany and US' (2017) ssrn.com

- ^ "Australian Centre for Industrial Relations Research and Training report" (PDF). Acirrt.com. Archived from the original (PDF) on 22 July 2011. Retrieved 27 July 2011.

- ^ "WFTU » History". 21 January 2014. Retrieved 25 January 2022.

- ^ "International Trade Union Confederation". www.ituc-csi.org. Retrieved 25 January 2022.

- ^ Bamberg, Ulrich (June 2004). "The role of German trade unions in the national and European standardisation process" (PDF). TUTB Newsletter. 24–25. Archived from the original (PDF) on 26 July 2011. Retrieved 27 July 2011.

- ^ Gold, M., 1993. The Social Dimension – Employment Policy in the European Community. Basingstoke England UK: Macmillan Publishing

- ^ Hall, M., 1994. Industrial Relations and the Social Dimension of European Integration: Before and after Maastricht, pp. 281–331 in Hyman, R. & Ferner A., eds.: New Frontiers in European Industrial Relations, Basil Blackwell Publishing

- ^ Wagtmann, M. A. (2010), Module 3, Maritime & Port Wages, Benefits, Labour Relations. International Maritime Human Resource Management

- ^ Short, Richard (6 June 2025). "Why must Conservatives embrace trades unionism? Because they always have". ConservativeHome. Retrieved 14 August 2025.

- ^ "Freedom of Association/Trade Union Freedom". Eurofound website. Archived from the original on 17 April 2011. Retrieved 3 March 2012.

- ^ "ECHR rules against Danish closed-shop agreements". Eurofound website. Archived from the original on 30 July 2014. Retrieved 5 January 2013.

- ^ Leonhardt, David (7 July 2023). "How Elba Makes a Living Wage". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 8 July 2023.

- ^ Ahlquist, John S. (2017). "Labor Unions, Political Representation, and Economic Inequality". Annual Review of Political Science. 20 (1): 409–432. doi:10.1146/annurev-polisci-051215-023225.

- ^ Farber, Henry S; Herbst, Daniel; Kuziemko, Ilyana; Naidu, Suresh (2021). "Unions and Inequality over the Twentieth Century: New Evidence from Survey Data*". The Quarterly Journal of Economics. 136 (3): 1325–1385. doi:10.1093/qje/qjab012. ISSN 0033-5533.

- ^ Collins, William J.; Niemesh, Gregory T. (2019). "Unions and the Great Compression of wage inequality in the US at mid-century: evidence from local labour markets". The Economic History Review. 72 (2): 691–715. doi:10.1111/ehr.12744. ISSN 1468-0289.

- ^ "Unions and American Income Inequality at Mid-Century". The Long Run. 12 February 2019. Archived from the original on 7 November 2020.

- ^ a b Rosenfeld, Jake (2014). What Unions No Longer Do. Cambridge: Harvard University. ISBN 9780674726215.

- ^ a b Western, Bruce; Rosenfeld, Jake (August 2011). "Unions, Norms, and the Rise in U.S. Wage Inequality" (PDF). American Sociological Review. 76 (4): 513–537. doi:10.1177/0003122411414817. ISSN 0003-1224. S2CID 18351034. Archived from the original (PDF) on 11 January 2024.

- ^ Doree Armstrong (12 February 2014). Jake Rosenfeld explores the sharp decline of union membership, influence. UW Today. Retrieved 6 March 2015. See also: Jake Rosenfeld (2014) What Unions No Longer Do. Harvard University Press. ISBN 0674725115

- ^ Keith Naughton, Lynn Doan and Jeffrey Green (20 February 2015). As the Rich Get Richer, Unions Are Poised for Comeback. Bloomberg. Retrieved 6 March 2015.

- "A 2011 study drew a link between the decline in union membership since 1973 and expanding wage disparity. Those trends have since continued, said Bruce Western, a professor of sociology at Harvard University who co-authored the study."

- ^ Stiglitz, Joseph E. (4 June 2012). The Price of Inequality: How Today's Divided Society Endangers Our Future (Kindle Locations 1148–1149). Norton. Kindle Edition.

- ^ Barry T. Hirsch, David A. Macpherson, and Wayne G. Vroman, "Estimates of Union Density by State", Monthly Labor Review, Vol. 124, No. 7, July 2001.

- ^ VanHeuvelen, Tom (1 March 2020). "The Right to Work, Power Resources, and Economic Inequality". American Journal of Sociology. 125 (5): 1255–1302. doi:10.1086/708067. ISSN 0002-9602. S2CID 219517711.

- ^ Western, Bruce; Rosenfeld, Jake (1 August 2011). "Unions, Norms, and the Rise in U.S. Wage Inequality". American Sociological Review. 76 (4): 513–537. doi:10.1177/0003122411414817. ISSN 0003-1224. S2CID 18351034.

- ^ Barth, Erling; Bryson, Alex; Dale-Olsen, Harald (16 October 2020). "Union Density Effects on Productivity and Wages". The Economic Journal. 130 (631): 1898–1936. doi:10.1093/ej/ueaa048. hdl:11250/2685607. ISSN 0013-0133.

- ^ Van den Berg, Annette, Arjen van Witteloostuijn, and Olivier Van der Brempt. "Employee workplace representation in Belgium: Effects on firm performance." International Journal of Manpower (2017).

- ^ Hirsch, Barry T. "What do unions do for economic performance?." Journal of Labor Research 25, no. 3 (2004): 415–455.

- ^ Vedder, Richard, and Lowell Gallaway. "The economic effects of labor unions revisited." Journal of labor research 23, no. 1 (2002): 105–130.

- ^ Monastiriotis, Vassilis (17 February 2003). "Union retreat and regional economic performance: the UK in the 1990s" (PDF). Research Papers in Environmental and Spatial Analysis. 77. Archived from the original on 11 January 2024 – via ResearchGate.

- ^ Monastiriotis, Vassilis (15 March 2007). "Union Retreat and Regional Economic Performance: The UK Experience". Regional Studies. 41 (2): 143–156. Bibcode:2007RegSt..41..143M. doi:10.1080/00343400601149915. S2CID 154851210 – via Taylor and Francis online.

- ^ Bryson, Alex. "Union wage effects." IZA World of Labor (2014).

- ^ Eavis, Peter (2 September 2024). "Will Automation Replace Jobs? Port Workers May Strike Over It". The New York Times. Retrieved 8 September 2024.

- ^ Kramarz, Francis (19 October 2006). "Outsourcing, Unions, and Wages: Evidence from data matching imports, firms, and workers" (PDF). Retrieved 22 January 2007.

- ^ Card David, Krueger Alan. (1995). Myth and measurement: The new economics of the minimum wage. Princeton, NJ. Princeton University Press.

- ^ Friedman, Milton (2007). Price theory ([New ed.], 3rd printing ed.). New Brunswick, NJ: Transaction Publishers. ISBN 978-0202309699.

- ^ Kusunoki, S. Hayek on labor unions and restraint of trade. Const Polit Econ (2023). doi:10.1007/s10602-023-09396-y

- ^ Tracy, Joseph (1986). Seniority Rules and the Gains from Union Organization (Report). Cambridge, MA: National Bureau of Economic Research. doi:10.3386/w2039.

- ^ Abdul-Razzak, Nour; Prato, Carlo; Wolton, Stephane (1 October 2020). "After Citizens United: How outside spending shapes American democracy". Electoral Studies. 67 102190. doi:10.1016/j.electstud.2020.102190. ISSN 0261-3794.

- ^ Macdonald, David (25 June 2020). "Labor Unions and White Democratic Partisanship". Political Behavior. 43 (2): 859–879. doi:10.1007/s11109-020-09624-3. ISSN 1573-6687. S2CID 220512676.

- ^ Hertel-Fernandez, Alexander (2018). "Policy Feedback as Political Weapon: Conservative Advocacy and the Demobilization of the Public Sector Labor Movement". Perspectives on Politics. 16 (2): 364–379. doi:10.1017/S1537592717004236. ISSN 1537-5927.

- ^ Becher, Michael; Stegmueller, Daniel (2020). "Reducing Unequal Representation: The Impact of Labor Unions on Legislative Responsiveness in the U.S. Congress". Perspectives on Politics. 19 (1): 92–109. doi:10.1017/S153759272000208X. ISSN 1537-5927. S2CID 204825962.

- ^ Engeman, Cassandra (2020). "When Do Unions Matter to Social Policy? Organized Labor and Leave Legislation in US States". Social Forces. 99 (4): 1745–1771. doi:10.1093/sf/soaa074.

- ^ Bucci, Laura C.; Jansa, Joshua M. (2020). "Who passes restrictive labour policy? A view from the States". Journal of Public Policy. 41 (3): 409–439. doi:10.1017/S0143814X20000070. ISSN 0143-814X. S2CID 216258517.

- ^ Becher, Michael; Stegmueller, Daniel (2020). "Reducing Unequal Representation: The Impact of Labor Unions on Legislative Responsiveness in the U.S. Congress". Perspectives on Politics. 19 (1): 92–109. doi:10.1017/S153759272000208X. ISSN 1537-5927.

- ^ Engeman, Cassandra (2020). "When Do Unions Matter to Social Policy? Organized Labor and Leave Legislation in US States". Social Forces. 99 (4): 1745–1771. doi:10.1093/sf/soaa074.

Event history analysis of state-level leave policy adoption from 1983 to 2016 shows that union institutional strength, particularly in the public sector, is positively associated with the timing of leave policy adoption.

- ^ Frymer, Paul; Grumbach, Jacob M. (2020). "Labor Unions and White Racial Politics". American Journal of Political Science. 65 (1): 225–240. doi:10.1111/ajps.12537. ISSN 1540-5907. S2CID 221245953.

- ^ Macdonald, David (29 April 2019). "How Labor Unions Increase Political Knowledge: Evidence from the United States". Political Behavior. 43 (1): 1–24. doi:10.1007/s11109-019-09548-7. ISSN 1573-6687. S2CID 159071392.

- ^ Anzia, Sarah F.; Moe, Terry M. (2015). "Public Sector Unions and the Costs of Government". The Journal of Politics. 77 (1): 114–127. doi:10.1086/678311. ISSN 0022-3816.

- ^ Eisenberg-Guyot, Jerzy; Mooney, Stephen J.; Hagopian, Amy; Barrington, Wendy E.; Hajat, Anjum (2020). "Solidarity and disparity: Declining labor union density and changing racial and educational mortality inequities in the United States". American Journal of Industrial Medicine. 63 (3): 218–231. doi:10.1002/ajim.23081. ISSN 1097-0274. PMC 7293351. PMID 31845387.

Results – Overall, a 10% increase in union density was associated with a 17% relative decrease in overdose/suicide mortality (95% confidence interval [CI]: 0.70, 0.98), or 5.7 lives saved per 100 000 person‐years (95% CI: −10.7, −0.7). Union density's absolute (lives‐saved) effects on overdose/suicide mortality were stronger for men than women, but its relative effects were similar across genders. Union density had little effect on all‐cause mortality overall or across subgroups, and modeling suggested union‐density increases would not affect mortality inequities. Conclusions - Declining union density (as operationalized in this study) may not explain all‐cause mortality inequities, although increases in union density may reduce overdose/suicide mortality.

- ^ Zoorob, Michael (1 October 2018). "Does 'right to work' imperil the right to health? The effect of labour unions on workplace fatalities". Occupational and Environmental Medicine. 75 (10): 736–738. doi:10.1136/oemed-2017-104747. ISSN 1351-0711. PMID 29898957. S2CID 49187014. Retrieved 31 January 2022.

The Local Average Treatment Effect of a 1% decline in unionisation attributable to RTW is about a 5% increase in the rate of occupational fatalities. In total, RTW laws have led to a 14.2% increase in occupational mortality through decreased unionisation.

Bibliography

[edit]- Braunthal, Gerard (1956). "The German Free Trade Unions during the Rise of Nazism". Journal of Central European Affairs. 14 (4): 339–353.

- Cole, G. D. H. (2010). Attempts at General Union. Taylor & Francis. ISBN 978-1136885167.

- James, Robert Noel (2001). Craft, Trade or Mystery. Tighes Hill.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Moses, John A. (December 1973). "The Trade Union Issue In German Social Democracy 1890–1900". Internationale Wissenschaftliche Korrespondenz zur Geschichte der Deutschen Arbeiterbewegung (19/20): 1–19.

- Schneider, Michael (1991). A brief history of the German trade unions. Bonn: JHW Dietz Nachfolger.

- Webb, Sidney; Webb, Beatrice (1920). "Chapter I". History of Trade Unionism. Longman.

Further reading

[edit]- Docherty, James C. (2004). Historical Dictionary of Organized Labor.

- Docherty, James C. (2010). The A to Z of Organized Labor.

- Kaplan, Ethan; Naidu, Suresh (2025). "Between Government and Market: The Political Economics of Labor Unions". Annual Review of Economics.

- St. James Encyclopedia of Labor History Worldwide : Major Events in Labor History and Their Impact ed by Neil Schlager (2 vol. 2004)

Britain

[edit]- Aldcroft, D. H. and Oliver, M. J., eds. Trade Unions and the Economy, 1870–2000. (2000).

- Campbell, A., Fishman, N., and McIlroy, J. eds. British Trade Unions and Industrial Politics: The Post-War Compromise 1945–64 (1999).

- Clegg, H.A. (1964). 1889–1910. A History of British Trade Unions Since 1889. Vol. I.

- Clegg, H.A. (1985). 1911–1933. A History of British Trade Unions Since 1889. Vol. II.

- Clegg, H.A. (1994). 1934–1951. A History of British Trade Unions Since 1889. Vol. III.

- Davies, A. J. (1996). To Build a New Jerusalem: Labour Movement from the 1890s to the 1990s.

- Laybourn, Keith (1992). A history of British trade unionism c. 1770–1990.

- Minkin, Lewis (1991). The Contentious Alliance: Trade Unions and the Labour Party. p. 708.

- Pelling, Henry (1987). A history of British trade unionism.

- Wrigley, Chris, ed. British Trade Unions, 1945–1995 (Manchester University Press, 1997)

- Zeitlin, Jonathan (1987). "From labour history to the history of industrial relations". Economic History Review. 40 (2): 159–184. doi:10.2307/2596686. JSTOR 2596686.

- Directory of Employer's Associations, Trade unions, Joint Organisations. Her Majesty's Stationery Office. 1986. ISBN 0113612508.

Europe

[edit]- Berghahn, Volker R., and Detlev Karsten. Industrial Relations in West Germany (Bloomsbury Academic, 1988).

- European Commission, Directorate General for Employment, Social Affairs & Inclusion: Industrial Relations in Europe 2010.

- Gumbrell-McCormick, Rebecca, and Richard Hyman. Trade unions in western Europe: Hard times, hard choices (Oxford UP, 2013).

- Kjellberg, Anders. "The Decline in Swedish Union Density since 2007", Nordic Journal of Working Life Studies (NJWLS) Vol. 1. No 1 (August 2011), pp. 67–93.

- Kjellberg, Anders (2017) The Membership Development of Swedish Trade Unions and Union Confederations Since the End of the Nineteenth Century (Studies in Social Policy, Industrial Relations, Working Life and Mobility). Research Reports 2017:2. Lund: Department of Sociology, Lund University.

- Kjellberg, Anders (2025) ”Changes in union density in the Nordic countries”, Nordic Economic Policy Review, pp. 124–129 (Nordregio and the Nordic Council of Ministers)

- Markovits, Andrei. The Politics of West German Trade Unions: Strategies of Class and Interest Representation in Growth and Crisis (Routledge, 2016).

- McGaughey, Ewan, 'Democracy or Oligarchy? Models of Union Governance in the UK, Germany and US' (2017) ssrn.com

- Misner, Paul. Catholic Labor Movements in Europe. Social Thought and Action, 1914–1965 (2015). online review

- Mommsen, Wolfgang J., and Hans-Gerhard Husung, eds. The development of trade unionism in Great Britain and Germany, 1880–1914 (Taylor & Francis, 1985).

- Ribeiro, Ana Teresa. "Recent Trends in Collective Bargaining in Europe." E-Journal of International and Comparative Labour Studies 5.1 (2016). online Archived 11 January 2017 at the Wayback Machine

- Upchurch, Martin, and Graham Taylor. The Crisis of Social Democratic Trade Unionism in Western Europe: The Search for Alternatives (Routledge, 2016).

United States

[edit]- Arnesen, Eric, ed. Encyclopedia of U.S. Labor and Working-Class History (2006), 3 vol; 2064pp; 650 articles by experts excerpt and text search

- Beik, Millie, ed. Labor Relations: Major Issues in American History (2005) over 100 annotated primary documents excerpt and text search

- Boris, Eileen, and Nelson Lichtenstein, eds. Major Problems In The History Of American Workers: Documents and Essays (2002)

- Brody, David. In Labor's Cause: Main Themes on the History of the American Worker (1993) excerpt and text search

- Guild, C. M. (2021). Union Library Workers Blog: The Years 2019–2020 in Review. Progressive Librarian, 48, 110–165.

- Dubofsky, Melvyn, and Foster Rhea Dulles. Labor in America: A History (2004), textbook, based on earlier textbooks by Dulles.

- Osnos, Evan, "Ruling-Class Rules: How to thrive in the power elite – while declaring it your enemy", The New Yorker, 29 January 2024

- Taylor, Paul F. The ABC-CLIO Companion to the American Labor Movement (1993) 237pp; short encyclopedia

- Zieger, Robert H., and Gilbert J. Gall, American Workers, American Unions: The Twentieth Century(3rd ed. 2002) excerpt and text search

Other

[edit]- Alexander, Robert Jackson, and Eldon M. Parker. A history of organized labor in Brazil (Greenwood, 2003).

- Dean, Adam. 2022. Opening Up By Cracking Down: Labor Repression and Trade Liberalization in Democratic Developing Countries. Cambridge University Press.

- Hodder, A. and L. Kretsos, eds. Young Workers and Trade Unions: A Global View (Palgrave-Macmillan, 2015). Review: Holgate, Jane (9 July 2016). "Book review: A Hodder and L Kretsos (eds), Young Workers and Trade Unions: A Global View". Work, Employment and Society. 31 (3): 561–562. doi:10.1177/0950017015614214. ISSN 0950-0170. S2CID 155792641.

- Kester, Gérard. Trade unions and workplace democracy in Africa (Routledge, 2016).

- Lenti, Joseph U. Redeeming the Revolution: The State and Organized Labor in Post-Tlatelolco Mexico (University of Nebraska Press, 2017).

- Levitsky, Steven, and Scott Mainwaring. "Organized labor and democracy in Latin America". Comparative Politics (2006): 21–42, JSTOR 20434019, doi:10.2307/20434019.

- Lipton, Charles (1967). The Trade Union Movement of Canada: 1827–1959. (3rd ed. Toronto, Ont.: New Canada Publications, 1973).

- Orr, Charles A. "Trade Unionism in Colonial Africa" Journal of Modern African Studies, 4 (1966), pp. 65–81

- Panitch, Leo & Swartz, Donald (2003). From consent to coercion: The assault on trade union freedoms (third edition. Ontario: Garamound Press).

- Taylor, Andrew. Trade Unions and Politics: A Comparative Introduction (Macmillan, 1989).

- Visser, Jelle. "Union membership statistics in 24 countries." Monthly Labor Review. 129 (2006): 38+ online

- Visser, Jelle. "ICTWSS: Database on institutional characteristics of trade unions, wage setting, state intervention and social pacts in 34 countries between 1960 and 2007". Institute for Advanced Labour Studies, AIAS, University of Amsterdam, Amsterdam (2011). online Archived 28 April 2020 at the Wayback Machine

External links

[edit]- Australian Council of Trade Unions

- LabourStart international trade union news service

- RadioLabour

- New Unionism Network Archived 6 January 2011 at the Wayback Machine

- Trade union membership 1993–2003 Archived 7 April 2022 at the Wayback Machine – European Industrial Relations Observatory report on membership trends in 26 European countries

- Trade union membership 2003–2008 Archived 12 April 2022 at the Wayback Machine – European Industrial Relations Observatory report on membership trends in 28 European countries

- Trade Union Ancestors – Listing of 5,000 UK trade unions with histories of main organisations, trade union "family trees" and details of union membership and strikes since 1900.

- TUC History online – History of the British union movement

- Short history of the UGT in Catalonia

- Younionize Global Union Directory

- "Retaliation for Union Activity and Collection Action Rights", Workplace Fairness

- Labor Notes magazine

- A History of Labor Unions from Colonial Times to 2009, from the Mises Institute

Trade union

View on GrokipediaA trade union, also known as a labor union, is a workers' organization formed to further and defend the economic and social interests of its members through collective bargaining with employers, strikes, and other forms of industrial action.[1] These associations emerged prominently during the Industrial Revolution as responses to harsh working conditions, long hours, and low pay in factories and mines, enabling workers to negotiate improvements in wages, hours, and safety standards that individual employees could not achieve alone.[2] Key historical achievements include advocacy for the eight-hour workday, as pursued by early groups like the National Labor Union founded in 1866, and contributions to legislation curbing child labor and establishing workplace protections.[3] Empirical evidence indicates that trade unions raise wages and benefits for their members—often by 10-20%—but these gains frequently come at the expense of reduced employment opportunities, lower firm profitability, and diminished productivity in unionized sectors, as higher labor costs can lead to outsourcing, automation, or business closures.[4] Strikes, a primary tool of unions, have secured concessions in some cases but also caused significant economic disruptions, including lost output and inflation pressures, while internal corruption scandals have repeatedly undermined their legitimacy, with leadership sometimes prioritizing personal gain over member interests.[5] Membership has declined sharply in many advanced economies; in the United States, the unionization rate stood at 9.9% of wage and salary workers in 2024, down from peaks above 30% mid-century, reflecting shifts toward service economies, globalization, and legal reforms favoring worker choice.[6] Despite these challenges, unions continue to wield influence through political lobbying and remain concentrated in public sectors, where they negotiate against taxpayer-funded entities rather than private employers.[7]

Definition and Characteristics

Core Definition and Purpose

A trade union, also known as a labor union, is a workers' organization constituted for the purpose of furthering and defending the economic and social interests of its members, typically through collective representation and negotiation with employers.[1] This structure enables workers, who individually possess limited bargaining power due to the asymmetry between single employees and firms, to act as a unified entity in addressing workplace issues.[8] The primary purpose of trade unions is to secure improvements in terms and conditions of employment, including higher wages, reduced working hours, enhanced safety standards, and benefits such as health insurance or pensions, often achieved via collective bargaining agreements that set binding terms for covered workers. Unions also represent members in grievances, disciplinary actions, and disputes, providing legal assistance and advocacy to mitigate employer abuses or unilateral changes. Beyond immediate workplace gains, unions historically aim to promote broader labor market stability and mutual aid among members, such as through strike funds or training programs, though empirical studies indicate that realized outcomes vary by context, with stronger unions correlating to higher wage premiums but potential trade-offs in employment levels.[9][10]Types of Unions and Legal Variations

Trade unions are categorized primarily by the scope of their membership and organizational focus. Craft unions organize workers with specialized skills or trades, such as electricians or plumbers, typically across multiple industries, emphasizing the preservation of skill-based bargaining power and apprenticeships. Industrial unions, by contrast, encompass all employees within a specific industry—skilled, semi-skilled, and unskilled—regardless of individual trade, aiming to standardize wages and conditions across broader production lines, as seen in sectors like automotive or mining. General unions recruit a diverse cross-section of workers, often including unskilled laborers from various trades, prioritizing broad solidarity over specialization. White-collar unions represent professional or office-based employees, such as teachers, nurses, or financial workers, focusing on issues like salary scales and workplace policies distinct from manual labor concerns.[11][12][13] Additional structural types emerge from national contexts. Enterprise unions, predominant in Japan, are company-specific organizations representing all employees within a single firm, fostering firm-level negotiations and long-term employment stability but limiting cross-firm coordination. Occupational or industrial unions in countries like Germany organize by profession or sector across enterprises, enabling centralized bargaining at industry levels through frameworks like the Metalworkers' Union (IG Metall), which covers millions in manufacturing. These models reflect causal differences in labor markets: enterprise unions align with Japan's lifetime employment norms, reducing adversarial conflict but constraining wage compression across competitors, while occupational models in export-oriented economies like Germany's support coordinated wage policies to maintain competitiveness.[14][15][16] Legal variations in union operations stem from national statutes governing recognition, security agreements, and rights. In the United States, the National Labor Relations Act of 1935 mandates secret-ballot elections via the National Labor Relations Board for certification, prohibiting closed shops—where only union members can be hired—since the Taft-Hartley Act of 1947, while permitting union shops (requiring membership post-hire) unless overridden by state right-to-work laws in 27 states as of 2023, which ban compulsory dues and have correlated with lower union density in those jurisdictions. The United Kingdom's Trade Union and Labour Relations (Consolidation) Act 1992 allows voluntary recognition or statutory processes through the Central Arbitration Committee if 10% of workers support and 50%+1 vote yes in a ballot, with recent 2024 Employment Rights Bill proposals easing access rights and disclosure requirements to bolster organizing. In continental Europe, such as Germany, the Works Constitution Act of 1952 integrates unions into co-determination boards for larger firms, emphasizing sectoral collective agreements over firm-level ones, contrasting with the U.S.'s enterprise-focused model and contributing to higher union coverage rates exceeding 50% via extension mechanisms. Japan's Trade Union Act of 1949 protects enterprise unions with minimal government intervention, prohibiting strikes in public sectors and favoring consensus-based shunto wage rounds, which has sustained low strike rates but enterprise-specific outcomes. These frameworks causally influence union efficacy: restrictive security rules in right-to-work U.S. states reduce free-rider problems but empirically link to 5-10% lower membership, per labor economics analyses, while Europe's extension of agreements to non-union firms amplifies coverage without proportional density gains.[17][18][19]Historical Development

Pre-Industrial Precursors and Guilds

In ancient Egypt, organized groups of craftsmen, such as those at Deir el-Medina who built royal tombs, engaged in the first recorded strike around 1157 BCE during the reign of Ramesses III, halting work due to delayed grain payments and securing concessions through petition to pharaohs.[20] These associations provided mutual support among skilled laborers but operated under state oversight, focusing on communal welfare rather than bargaining autonomy.[21] In the Roman Republic and Empire, collegia served as voluntary associations for artisans, merchants, and laborers, encompassing trades like weaving, dyeing, and shoemaking; they facilitated burial funds, festive banquets, and professional networking while occasionally influencing local politics or petitioning authorities on economic grievances.[22] Unlike modern unions, Roman collegia emphasized religious and social rituals alongside trade regulation, with membership often stratified by status and subject to periodic state suppression under emperors like Trajan to curb potential unrest.[23] Medieval European guilds emerged as structured precursors, beginning with merchant guilds in the 11th century that monopolized local commerce, secured trading privileges from feudal lords, and enforced standards to limit competition; for instance, the Guild of St. George in Norwich, England, obtained a royal charter in 1197 regulating textile exports.[24] Craft guilds followed in the 12th century, organizing specific occupations like blacksmithing or tailoring within towns, where they controlled entry via lengthy apprenticeships—typically seven years—to transmit skills and maintain quality, advancing trainees from apprentice to journeyman and eventually master upon producing a masterpiece.[24] These guilds functioned through collective rules on pricing, workmanship, and labor supply, often providing mutual aid such as aid for the sick, widows, or orphans, and mediating disputes between masters and workers; however, their monopolistic practices, including bans on innovation or subcontracting, prioritized member rents over broader labor mobility. In cities like Florence and Paris by the 13th century, guilds wielded quasi-governmental power, inspecting goods and fining violators, yet their exclusivity—requiring capital for mastery—limited access and foreshadowed tensions with emerging wage labor in proto-industrial settings.[24] While sharing unions' emphasis on group solidarity and interest protection, guilds embedded craft hierarchies and market controls that modern trade unions later rejected in favor of industrial-scale wage negotiations.Emergence During Industrialization

The mechanized factory system of the British Industrial Revolution, accelerating from the 1760s onward, displaced skilled craft work with mass wage labor, exposing workers to grueling 12- to 16-hour shifts, subsistence wages averaging 10-15 shillings weekly for adults, rampant child exploitation, and machinery hazards causing frequent injuries and deaths without compensation.[25] This structural shift eroded pre-industrial guild bargaining power, fostering conditions where individual workers lacked leverage against employers controlling production means, thus necessitating collective organization for mutual aid, wage defense, and safety demands.[26] Early combinations—precursors to formal unions—arose among artisans in sectors like wool and cotton by the late 1700s, often as benefit societies pooling funds for strikes or unemployment, but faced severe legal suppression under the Combination Acts of 1799 and 1800, which criminalized any worker agreement to raise wages or shorten hours, treating them as seditious conspiracies punishable by imprisonment or transportation.[27] Repeal of the Combination Acts in 1824, driven by reformer Francis Place's lobbying and parliamentary testimony from workers demonstrating combinations' limited efficacy without legality, enabled open union formation and sparked immediate strikes in London and provincial trades, though a follow-up Combinations of Workmen Act in 1825 curtailed picketing and collective bargaining, confining unions to "peaceful" persuasion.[28] Union density grew modestly in skilled crafts like engineering and printing, with groups such as the Journeymen Steam Engine Makers' Society (founded 1824) negotiating rudimentary agreements, while broader general unions like Robert Owen's Grand National Consolidated Trades Union (1833-1834) briefly attracted 800,000 members before collapsing amid employer blacklists and internal disputes.[29] Repression persisted, exemplified by the 1834 Tolpuddle Martyrs case, where six Dorset farm laborers were convicted under an obsolete 1797 Unlawful Oaths Act for swearing loyalty in a friendly society protesting 10% wage reductions to 7 shillings weekly; sentenced to seven years' transportation to Australia, their plight mobilized 100,000-signature petitions, leading to royal pardons by 1836 and symbolizing state overreach against rural organizing amid urban industrial focus.[30] As industrialization diffused, union emergence mirrored Britain's pattern elsewhere, driven by factory concentration enabling rapid mobilization against analogous employer monopsony. In the United States, where textile mills proliferated post-1810s, the first documented strike occurred in Pawtucket, Rhode Island, in 1824, with 1,000 women and children protesting a 25% wage cut and longer hours, marking proto-union action in the world's second major industrial hub.[31] By the 1830s, craft unions coalesced into federations in cities like Philadelphia and New York, advocating ten-hour days amid rapid urbanization that swelled the non-agricultural workforce from 5% in 1800 to 40% by 1860, though lacking legal protections until state reforms in the 1840s.[32] Continental Europe lagged due to slower mechanization and absolutist regimes, but French mutual aid societies evolved into strikes post-1830 Revolution, while German unions formed clandestinely in the 1840s amid Zollverein trade liberalization, expanding post-1871 unification as coal and steel output surged tenfold by 1900.[33] These early unions prioritized defensive tactics—benefit funds covering 5-10 shillings weekly during lockouts—over revolutionary aims, yielding incremental gains like localized wage floors but often provoking violent clashes, as employers deployed private militias or state troops to break assemblies.[34]Legal Recognition and Expansion (19th-20th Centuries)

The repeal of the UK's Combination Acts in 1824 ended prior prohibitions on workers combining for collective action, thereby permitting the formation of trade unions without automatic criminalization under conspiracy doctrines.[35] This shift followed persistent worker agitation and parliamentary inquiries into industrial conditions, though unions remained vulnerable to civil liabilities for actions like strikes. The Trade Union Act 1871 further solidified recognition by declaring unions lawful entities capable of owning property and suing or being sued, while exempting their funds from liability for torts committed by members during disputes.[36] The subsequent Conspiracy and Protection of Property Act 1875 legalized peaceful picketing and strikes, narrowing the scope of criminal conspiracy charges against union activities, which facilitated organizational expansion amid rapid industrialization.[37] In the United States, early 19th-century common-law precedents treated union activities as restraints of trade, leading courts to issue injunctions against organizing and strikes; the Sherman Antitrust Act of 1890 exacerbated this by enabling federal prosecutions of unions as monopolistic combinations.[38] Partial relief came with the Clayton Antitrust Act of 1914, which explicitly exempted labor unions from antitrust scrutiny and affirmed workers' rights to organize, boycott, and strike as non-violative of federal law.[39] The Norris-LaGuardia Act of 1932 curtailed judicial injunctions in labor disputes, promoting voluntary arbitration, while the National Labor Relations Act (Wagner Act) of July 5, 1935, mandated employer neutrality toward unionization, established the National Labor Relations Board to oversee elections and unfair labor practices, and enshrined collective bargaining as a protected right, spurring union membership from 3 million in 1933 to over 9 million by 1941.[40][41] Across continental Europe, legal frameworks evolved unevenly but trended toward recognition by the late 19th century, often in response to socialist pressures and industrial unrest. In Germany, the repeal of the Anti-Socialist Laws on October 1, 1890, lifted bans on union activities, enabling the growth of free trade unions under the General German Trade Union Federation, which reached 2.5 million members by 1912. In France, the Waldeck-Rousseau law of July 21, 1884, authorized union formation without prior government approval, reversing Napoleonic-era restrictions and allowing syndicates to negotiate contracts, though employer resistance persisted until interwar reforms. These national developments intersected with international efforts; the International Labour Organization, established in 1919, advanced global standards through Convention No. 87 (1948), which ratified freedom of association and union independence from state interference, influencing ratification by over 150 countries by the late 20th century and embedding union rights in post-World War II constitutions and labor codes.[42][43] By the mid-20th century, legal expansions correlated with welfare state formations, granting unions roles in co-determination (e.g., Germany's Works Constitution Act of 1951) and mandatory bargaining in sectors like manufacturing, though empirical analyses indicate that such protections often amplified wage pressures without proportionally sustaining long-term employment gains, as evidenced by varying membership densities post-1945.[44] This era's statutes, while empowering unions, also introduced regulatory oversight to curb excesses like indefinite strikes, reflecting causal trade-offs between worker leverage and economic stability.Post-World War II Growth and Modern Decline