Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Parody

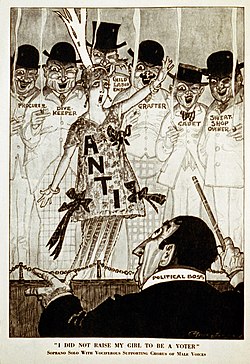

View on WikipediaA parody is a creative work designed to imitate, comment on, and/or mock its subject by means of satirical or ironic imitation. Often its subject is an original work or some aspect of it (theme/content, author, style, etc), but a parody can also be about a real-life person (e.g. a politician), event, or movement (e.g. the French Revolution or 1960s counterculture). Literary scholar Professor Simon Dentith defines parody as "any cultural practice which provides a relatively polemical allusive imitation of another cultural production or practice".[1] The literary theorist Linda Hutcheon said "parody ... is imitation, not always at the expense of the parodied text." Parody may be found in art or culture, including literature, music, theater, television and film, animation, and gaming.

The writer and critic John Gross observes in his Oxford Book of Parodies, that parody seems to flourish on territory somewhere between pastiche ("a composition in another artist's manner, without satirical intent") and burlesque (which "fools around with the material of high literature and adapts it to low ends").[2] Meanwhile, the Encyclopédie of Denis Diderot distinguishes between the parody and the burlesque, "A good parody is a fine amusement, capable of amusing and instructing the most sensible and polished minds; the burlesque is a miserable buffoonery which can only please the populace."[3] Historically, when a formula grows tired, as in the case of the moralistic melodramas in the 1910s, it retains value only as a parody, as demonstrated by the Buster Keaton shorts that mocked that genre.[4]

Terminology

[edit]A parody may also be known as a spoof, a satire, a send-up, a take-off, a lampoon, a play on (something), or a caricature.

Origins

[edit]According to Aristotle (Poetics, ii. 5), Hegemon of Thasos was the inventor of a kind of parody; by slightly altering the wording in well-known poems he transformed the sublime into the ridiculous. In ancient Greek literature, a parodia was a narrative poem imitating the style and prosody of epics "but treating light, satirical or mock-heroic subjects".[5] Indeed, the components of the Greek word are παρά para "beside, counter, against" and ᾠδή oide "song". Thus, the original Greek word παρῳδία parodia has sometimes been taken to mean "counter-song", an imitation that is set against the original. The Oxford English Dictionary, for example, defines parody as imitation "turned as to produce a ridiculous effect".[6] Because par- also has the non-antagonistic meaning of beside, "there is nothing in parodia to necessitate the inclusion of a concept of ridicule."[7]

In Greek Old Comedy even the gods could be made fun of. The Frogs portrays the hero-turned-god Heracles as a glutton and the God of Drama Dionysus as cowardly and unintelligent. The traditional trip to the Underworld story is parodied as Dionysus dresses as Heracles to go to the Underworld, in an attempt to bring back a poet to save Athens. The Ancient Greeks created satyr plays which parodied tragic plays, often with performers dressed like satyrs.

Parody was used in early Greek philosophical texts to make philosophical points. Such texts are known as spoudaiogeloion, a famous example of which is the Silloi by Pyrrhonist philosopher Timon of Phlius which parodied philosophers living and dead. The style was a rhetorical mainstay of the Cynics and was the most common tone of the works made by Menippus and Meleager of Gadara.[8]

In the 2nd century CE, Lucian of Samosata created a parody of travel texts such as Indica and The Odyssey. He described the authors of such accounts as liars who had never traveled, nor ever talked to any credible person who had. In his ironically named book True History Lucian delivers a story which exaggerates the hyperbole and improbable claims of those stories. Sometimes described as the first science fiction, the characters travel to the Moon, engage in interplanetary war with the help of aliens they meet there, and then return to Earth to experience civilization inside a 200-mile-long creature generally interpreted as being a whale. This is a parody of Ctesias' claims that India has a one-legged race of humans with a single foot so huge it can be used as an umbrella, Homer's stories of one-eyed giants, and so on.

Related terms

[edit]Parody exists in the following related genres: satire, travesty, pastiche, skit, burlesque.

Satire

[edit]Satires and parodies are both derivative works that exaggerate their source material(s) in humorous ways.[9][10][11] However, a satire is meant to make fun of the real world, whereas a parody is a derivative of a specific work ("specific parody") or a general genre ("general parody" or "spoof"). Furthermore, satires are provocative and critical as they point to a specific vice associated with an individual or a group of people to mock them into correction or as a form of punishment.[11][12] In contrast, parodies are more focused on producing playful humor and do not always attack or criticize its targeted work and/or genre.[11][13] Of course, it is possible for a parody to maintain satiric elements without crossing into satire itself, as long as its "light verse with modest aspirations" ultimately dominates the work.[11]

Travesty

[edit]A travesty imitates and transforms a work, but focuses more on the satirization of it. Because satire is meant to attack someone or something,[11] the harmless playfulness of parody is lost.[13]

Pastiche

[edit]A pastiche imitates a work as a parody does, but unlike a parody, pastiche is neither transformative of the original work, nor is it humorous.[13][14] Literary critic Fredric Jameson has referred to the pastiche as a "blank parody", or "parody that has lost its sense of humor".[14]

Skit

[edit]Skits imitate works "in a satirical regime". But unlike travesties, skits do not transform the source material.[13]

Burlesque

[edit]The burlesque primarily targets heroic poems and theater to degrade popular heroes and gods, as well as mock the common tropes within the genre.[11] Simon Dentith has described this type of parody as "parodic anti-heroic drama".[13]

Spoof

[edit]A parody imitates and mocks a specific, recognizable work (e.g. a book, movie, etc.) or the characteristic style of a particular author. A spoof mocks an entire genre by exaggerating its conventions and cliches for humorous effect.[13]

Music

[edit]In classical music, as a technical term, parody refers to a reworking of one kind of composition into another (for example, a motet into a keyboard work as Girolamo Cavazzoni, Antonio de Cabezón, and Alonso Mudarra all did to Josquin des Prez motets).[15] More commonly, a parody mass (missa parodia) or an oratorio used extensive quotation from other vocal works such as motets or cantatas; Victoria, Palestrina, Lassus, and other composers of the 16th century used this technique. The term is also sometimes applied to procedures common in the Baroque period, such as when Bach reworks music from cantatas in his Christmas Oratorio.

The musicological definition of the term parody has now generally been supplanted by a more general meaning of the word. In its more contemporary usage, musical parody usually has humorous, even satirical intent, in which familiar musical ideas or lyrics are lifted into a different, often incongruous, context.[16] Musical parodies may imitate or refer to the peculiar style of a composer or artist, or even a general style of music. For example, "The Ritz Roll and Rock", a song and dance number performed by Fred Astaire in the movie Silk Stockings, parodies the rock and roll genre. Conversely, while the best-known work of "Weird Al" Yankovic is based on particular popular songs, it also often utilises wildly incongruous elements of pop culture for comedic effect.

English term

[edit]

The first usage of the word parody in English cited in the Oxford English Dictionary is in Ben Jonson, in Every Man in His Humour in 1598: "A Parodie, a parodie! to make it absurder than it was." The next citation comes from John Dryden in 1693, who also appended an explanation, suggesting that the word was in common use, meaning to make fun of or re-create what you are doing.

Modernist and post-modernist parody

[edit]Since the 20th century, parody has been heightened as the central and most representative artistic device, the catalysing agent of artistic creation and innovation.[17][18] This most prominently happened in the second half of the century with postmodernism, but earlier modernism and Russian formalism had anticipated this perspective.[17][19] For the Russian formalists, parody was a way of liberation from the background text that enables to produce new and autonomous artistic forms.[20][21]

Historian Christopher Rea[22] writes that "In the 1910s and 1920s, writers in China's entertainment market parodied anything and everything.... They parodied speeches, advertisements, confessions, petitions, orders, handbills, notices, policies, regulations, resolutions, discourses, explications, sutras, memorials to the throne, and conference minutes. We have an exchange of letters between the Queue and the Beard and Eyebrows. We have a eulogy for a chamber pot. We have 'Research on Why Men Have Beards and Women Don't,' 'A Telegram from the Thunder God to His Mother Resigning His Post,' and 'A Public Notice from the King of Whoring Prohibiting Playboys from Skipping Debts.'"[23][24]

Jorge Luis Borges's (1939) short story "Pierre Menard, Author of the Quixote", is often regarded as predicting postmodernism and conceiving the ideal of the ultimate parody.[25][26] In the broader sense of Greek parodia, parody can occur when whole elements of one work are lifted out of their context and reused, not necessarily to be ridiculed.[27] Traditional definitions of parody usually only discuss parody in the stricter sense of something intended to ridicule the text it parodies. There is also a broader, extended sense of parody that may not include ridicule, and may be based on many other uses and intentions.[27][28] The broader sense of parody, parody done with intent other than ridicule, has become prevalent in the modern parody of the 20th century.[28] In the extended sense, the modern parody does not target the parodied text, but instead uses it as a weapon to target something else.[29][30] The reason for the prevalence of the extended, recontextualizing type of parody in the 20th century is that artists have sought to connect with the past while registering differences brought by modernity.[31][page needed] Major modernist examples of this recontextualizing parody include James Joyce's Ulysses, which incorporates elements of Homer's Odyssey in a 20th-century Irish context, and T. S. Eliot's The Waste Land,[29] which incorporates and recontextualizes elements of a vast range of prior texts, including Dante's The Inferno.[citation needed] The work of Andy Warhol is another prominent example of the modern "recontextualizing" parody.[29] According to French literary theorist Gérard Genette, the most rigorous and elegant form of parody is also the most economical, that is a minimal parody, the one that literally reprises a known text and gives it a new meaning.[32][33]

Blank parody, in which an artist takes the skeletal form of an art work and places it in a new context without ridiculing it, is common.[14] Pastiche is a closely related genre, and parody can also occur when characters or settings belonging to one work are used in a humorous or ironic way in another, such as the transformation of minor characters Rosencrantz and Guildenstern from Shakespeare's drama Hamlet into the principal characters in a comedic perspective on the same events in the play (and film) Rosencrantz and Guildenstern Are Dead.[citation needed] Similarly, Mishu Hilmy's Trapped in the Netflix uses parody to deconstruct contemporary Netflix shows like Mad Men providing commentary through popular characters. Don Draper mansplaining about mansplaining, Luke Danes monologizing about a lack of independence while embracing codependency.[34] In Flann O'Brien's novel At Swim-Two-Birds, for example, mad King Sweeney, Finn MacCool, a pookah, and an assortment of cowboys all assemble in an inn in Dublin: the mixture of mythic characters, characters from genre fiction, and a quotidian setting combine for a humor that is not directed at any of the characters or their authors. This combination of established and identifiable characters in a new setting is not the same as the post-modernist trope of using historical characters in fiction out of context to provide a metaphoric element.[citation needed]

Reputation

[edit]Sometimes the reputation of a parody outlasts the reputation of what is being parodied. For example, Don Quixote, which mocks the traditional knight errant tales, is much better known than the novel that inspired it, Amadis de Gaula (although Amadis is mentioned in the book). Another case is the novel Shamela by Henry Fielding (1742), which was a parody of the gloomy epistolary novel Pamela, or Virtue Rewarded (1740) by Samuel Richardson. Many of Lewis Carroll's parodies of Victorian didactic verse for children, such as "You Are Old, Father William", are much better known than the (largely forgotten) originals. Stella Gibbons's comic novel Cold Comfort Farm has eclipsed the pastoral novels of Mary Webb which largely inspired it.

In more recent times, the television sitcom 'Allo 'Allo! is perhaps better known than the drama Secret Army which it parodies.

Some artists carve out careers by making parodies. One of the best-known examples is that of "Weird Al" Yankovic. His career of parodying other musical acts and their songs has outlasted many of the artists or bands he has parodied. Yankovic is not required under law to get permission to parody; as a personal rule, however, he does seek permission to parody a person's song before recording it. Several artists, such as rapper Chamillionaire and Seattle-based grunge band Nirvana stated that Yankovic's parodies of their respective songs were excellent, and many artists have considered being parodied by him to be a badge of honor.[35][36]

In the US legal system the point that in most cases a parody of a work constitutes fair use was upheld in the case of Rick Dees, who decided to use 29 seconds of the music from the song When Sonny Gets Blue to parody Johnny Mathis' singing style even after being refused permission. An appeals court upheld the trial court's decision that this type of parody represents fair use. Fisher v. Dees 794 F.2d 432 (9th Cir. 1986)

Film parodies

[edit]This section possibly contains original research. (May 2009) |

Some genre theorists, following Bakhtin, see parody as a natural development in the life cycle of any genre; this idea has proven especially fruitful for genre film theorists. Such theorists note that Western movies, for example, after the classic stage defined the conventions of the genre, underwent a parody stage, in which those same conventions were ridiculed and critiqued. Because audiences had seen these classic Westerns, they had expectations for any new Westerns, and when these expectations were inverted, the audience laughed.

An early parody film was the 1922 movie Mud and Sand, a Stan Laurel film that made fun of Rudolph Valentino's film Blood and Sand. Laurel specialized in parodies in the mid-1920s, writing and acting in a number of them. Some were send-ups of popular films, such as Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde—parodied in the comic Dr. Pyckle and Mr. Pryde (1926). Others were spoofs of Broadway plays, such as No, No, Nanette (1925), parodied as Yes, Yes, Nanette (1925). In 1940 Charlie Chaplin created a satirical comedy about Adolf Hitler with the film The Great Dictator, following the first-ever Hollywood parody of the Nazis, the Three Stooges' short subject You Nazty Spy!.

About 20 years later Mel Brooks started his career with a Hitler parody as well. After his 1967 film The Producers won both an Academy Award and a Writers Guild of America Award for Best Original Screenplay,[37] Brooks became one of the most famous film parodists and created spoofs in multiple film genres. Blazing Saddles (1974) is a parody of western films, History of the World, Part I (1981) is a historical parody, Robin Hood Men in Tights (1993) is Brooks' take on the classic Robin Hood tale, and his spoofs in the horror, sci-fi and adventure genres include Young Frankenstein (1974), and Spaceballs (1987, a Star Wars spoof).

The British comedy group Monty Python is also famous for its parodies, for example, the King Arthur spoof Monty Python and the Holy Grail (1974), and the religious satire Life of Brian (1979). In the 1980s the team of David Zucker, Jim Abrahams and Jerry Zucker parodied well-established genres such as disaster, war and police movies with the Airplane!, Hot Shots! and Naked Gun series respectively. There is a 1989 film parody from Spain of the TV series The A-Team called El equipo Aahhgg directed by José Truchado.

More recently, parodies have taken on whole film genres at once. One of the first was Don't Be a Menace to South Central While Drinking Your Juice in the Hood and the Scary Movie franchise. Other recent genre parodies include Shriek If You Know What I Did Last Friday the 13th, Not Another Teen Movie, Date Movie, Epic Movie, Meet the Spartans, Superhero Movie, Disaster Movie, Vampires Suck, and The 41-Year-Old Virgin Who Knocked Up Sarah Marshall and Felt Superbad About It, all of which have been critically panned.[citation needed]

Copyright

[edit]Many parody films have as their target out-of-copyright or non-copyrighted subjects (such as Frankenstein or Robin Hood) whilst others settle for imitation which does not infringe copyright, but is clearly aimed at a popular (and usually lucrative) subject. The spy film craze of the 1960s, fuelled by the popularity of James Bond is such an example. In this genre a rare, and possibly unique, example of a parody film taking aim at a non-comedic subject over which it actually holds copyright is the 1967 James Bond spoof Casino Royale. In this case, producer Charles K. Feldman initially intended to make a serious film, but decided that it would not be able to compete with the established series of Bond films. Hence, he decided to parody the series.[38]

Poetic parodies

[edit]Kenneth Baker considered poetic parody to take five main forms.[39]

- The first was to use parody to attack the author parodied, as in J K Stephen's mimicry of Wordsworth, "Two voices are there: one is of the deep....And one is of an old half-witted sheep."[40]

- The second was to pastiche the author's style, as with Henry Reed's parody of T. S. Eliot, Chard Whitlow: "As we get older we do not get any younger...."[41]

- The third type reversed (and so undercut) the sentiments of the poem parodied, as with Monty Python's All Things Dull and Ugly.

- A fourth approach was to use the target poem as a matrix for inserting unrelated (generally humorous) material – "To have it out or not? That is the question....Thus dentists do make cowards of us all."[42]

- Finally, parody may be used to attack contemporary/topical targets by utilizing the format of a well-known piece of verse: "O Rushdie, Rushdie, it's a vile world" (Cat Stevens).[43]

A further, more constructive form of poetic parody is one that links the contemporary poet with past forms and past masters through affectionate parodying – thus sharing poetic codes while avoiding some of the anxiety of influence.[44]

More aggressive in tone are playground poetry parodies, often attacking authority, values and culture itself in a carnivalesque rebellion:[45] "Twinkle, Twinkle little star,/ Who the hell do you think you are?"[46]

Self-parody

[edit]A subset of parody is self-parody in which artists parody their own work (as in Ricky Gervais's Extras).

Copyright issues and other legal issues

[edit]Although a parody can be considered a derivative work of a pre-existing, copyrighted work, some countries have ruled that parodies can fall under copyright limitations such as fair dealing, or otherwise have fair dealing laws that include parody in their scope.

United States

[edit]Parodies are protected under the fair use doctrine of United States copyright law, but the defense is more successful if the usage of an existing copyrighted work is transformative in nature, such as being a critique or commentary upon it.

In Campbell v. Acuff-Rose Music, Inc., the Supreme Court ruled that a rap parody of "Oh, Pretty Woman" by 2 Live Crew was fair use, as the parody was a distinctive, transformative work designed to ridicule the original song, and that "even if 2 Live Crew's copying of the original's first line of lyrics and characteristic opening bass riff may be said to go to the original's 'heart,' that heart is what most readily conjures up the song for parody, and it is the heart at which parody takes aim."

In 2001, the Eleventh Circuit Court of Appeals, in Suntrust v. Houghton Mifflin, upheld the right of Alice Randall to publish a parody of Gone with the Wind called The Wind Done Gone, which told the same story from the point of view of Scarlett O'Hara's slaves, who were glad to be rid of her.

In 2007, the Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals denied a fair use defense in the Dr. Seuss Enterprises v. Penguin Books case. Citing the Campbell v. Acuff-Rose decision, they found that a satire of the O.J. Simpson murder trial and parody of The Cat in the Hat had infringed upon the children's book because it did not provide a commentary function upon that work.[47][48]

Canada

[edit]Parts of this article (those related to Changes from the Copyright Modernization Act, 2012) need to be updated. (September 2012) |

Under Canadian law, although there is protection for Fair Dealing, there is no explicit protection for parody and satire. In Canwest v. Horizon, the publisher of the Vancouver Sun launched a lawsuit against a group which had published a pro-Palestinian parody of the paper. Alan Donaldson, the judge in the case, ruled that parody is not a defence to a copyright claim.[49]

As of the implementation of the Copyright Modernization Act 2012, "Fair dealing for the purpose of research, private study, education, parody or satire does not infringe copyright."[50]

United Kingdom

[edit]In 2006 the Gowers Review of Intellectual Property recommended that the UK should "create an exception to copyright for the purpose of caricature, parody or pastiche by 2008".[51] Following the first stage of a two-part public consultation, the Intellectual Property Office reported that the information received "was not sufficient to persuade us that the advantages of a new parody exception were sufficient to override the disadvantages to the creators and owners of the underlying work. There is therefore no proposal to change the current approach to parody, caricature and pastiche in the UK."[52]

However, following the Hargreaves Review in May 2011 (which made similar proposals to the Gowers Review) the Government broadly accepted these proposals. The current law (effective from 1 October 2014), namely Section 30A[53] of the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988, now provides an exception to infringement where there is fair dealing of the original work for the purpose of parody (or alternatively for the purpose of caricature or pastiche). The legislation does not define what is meant by "parody", but the UK IPO – the Intellectual Property Office (United Kingdom) – suggests[54] that a "parody" is something that imitates a work for humorous or satirical effect. See also Fair dealing in United Kingdom law.

Jail

[edit]Some countries do not like parodies and the parodies can be considered insulting. The person who makes the parody can be fined or even jailed. For instance in the UAE[55] and North Korea,[56] this is not allowed.

Internet culture

[edit]Parody is a prominent genre in online culture, thanks in part to the ease with which digital texts may be altered, appropriated, and shared. Japanese kuso and Chinese e'gao are emblematic of the importance of parody in online cultures in Asia. Video mash-ups and other parodic memes, such as humorously altered Chinese characters, have been particularly popular as a tool for political protest in the People's Republic of China, the government of which maintains an extensive censorship apparatus.[57] Chinese internet slang makes extensive use of puns and parodies on how Chinese characters are pronounced or written, as illustrated in the Grass-Mud Horse Lexicon.

Computer-generated parodies

[edit]Parody generators are computer programs which generate text that is syntactically correct, but usually meaningless, often in the style of a technical paper or a particular writer. They are also called travesty generators and random text generators.

Their purpose is often satirical, intending to show that there is little difference between the generated text and real examples.

Many work by using techniques such as Markov chains to reprocess real text examples; alternatively, they may be hand-coded. Generated texts can vary from essay length to paragraphs and tweets. (The term "quote generator" can also be used for software that randomly selects real quotations.)Social and political uses

[edit]

Parody is often used to make a social or political statement. Examples include Swift's "A Modest Proposal", which satirized English neglect of Ireland by parodying emotionally disengaged political tracts; and, recently, The Daily Show, The Larry Sanders Show and The Colbert Report, which parody a news broadcast and a talk show to satirize political and social trends and events.

On the other hand, the writer and frequent parodist Vladimir Nabokov made a distinction: "Satire is a lesson, parody is a game."[58]

Some events, such as a national tragedy, can be difficult to handle. Chet Clem, Editorial Manager of the news parody publication The Onion, told Wikinews in an interview the questions that are raised when addressing difficult topics:

I know the September 11 issue was an obviously very large challenge to approach. Do we even put out an issue? What is funny at this time in American history? Where are the jokes? Do people want jokes right now? Is the nation ready to laugh again? Who knows. There will always be some level of division in the back room. It's also what keeps us on our toes.[59]

Parody is by no means necessarily satirical, and may sometimes be done with respect and appreciation of the subject involved, without being a heedless sarcastic attack.

Parody has also been used to facilitate dialogue between cultures or subcultures. Sociolinguist Mary Louise Pratt identifies parody as one of the "arts of the contact zone", through which marginalized or oppressed groups "selectively appropriate", or imitate and take over, aspects of more empowered cultures.[60]

Shakespeare often uses a series of parodies to convey his meaning. In the social context of his era, an example can be seen in King Lear where the fool is introduced with his coxcomb to be a parody of the king.

Examples

[edit]Historic examples

[edit]- Sir Thopas in Canterbury Tales, by Geoffrey Chaucer

- Morgante by Luigi Pulci

- The Nymph's Reply to the Shepherd by Sir Walter Raleigh

- La secchia rapita by Alessandro Tassoni

- Don Quixote by Miguel de Cervantes

- Beware the Cat by William Baldwin

- The Knight of the Burning Pestle by Francis Beaumont and John Fletcher

- Dragon of Wantley, an anonymous 17th century ballad

- Hudibras by Samuel Butler

- "MacFlecknoe", by John Dryden

- A Tale of a Tub by Jonathan Swift

- The Rape of the Lock by Alexander Pope

- Namby Pamby by Henry Carey

- Northanger Abbey by Jane Austen

- Gulliver's Travels by Jonathan Swift

- The Dunciad by Alexander Pope

- Memoirs of Martinus Scriblerus by John Gay, Alexander Pope, John Arbuthnot, et al.

- Mozart's A Musical Joke (Ein musikalischer Spaß), K.522 (1787) – parody of incompetent contemporaries of Mozart, as assumed by some theorists

- Sartor Resartus by Thomas Carlyle

- Ways and Means, or The aged, aged man, by Lewis Carroll. Much of Alice in Wonderland and Through the Looking-Glass is parodic of Victorian schooling.

- Batrachomyomachia (battle between frogs and mice), an Iliad parody by an unknown ancient Greek author

- A Century of Parody and Imitation by Walter Jerrold and R. Maynard Leonard

Internet examples

[edit]- Punt nua, a parody currency and internet meme (2011)

- "After Ever After" a capella series by YouTube personality Jon Cozart, parody of various Disney songs

Modern television examples

[edit]- Saturday Night Live parodies of Sarah Palin

- Saturday Night Live parodies of Donald Trump

- Square One TV parodies of Dragnet

- Southpaw Regional Wrestling, WWE's parody of 80s territory-style professional wrestling

- On Cinema and spin-off Decker parody film review shows and political action thrillers, respectively.

- "Handyman Corner" and "Handyman Tip" segments on The Red Green Show by Steve Smith and Rick Green, parodying home improvement and do-it-yourself shows

- The "Get the Belt" sketch on A Black Lady Sketch Show parodies the genre of dance movies like Step Up and Save the Last Dance.

- Yonderland, parody of the medieval European fantasy genre.

Anime and manga

[edit]- The 100 Girlfriends Who Really, Really, Really, Really, Really Love You, parody of the harem genre

- Attack on Titan: Junior High and Spoof on Titan, official parodies of the Attack on Titan series

- Bobobo-bo Bo-bobo, parody of shōnen manga

- Cromartie High School, parody of the yankī genre

- Detroit Metal City, parody of the death metal scene and the music industry

- Excel Saga, parody of various anime genres and tropes

- Gintama, parody of shōnen manga and Japanese pop culture

- KonoSuba, parody of the isekai genre

- Monthly Girls' Nozaki-kun, parody of shōjo manga

- Mr. Osomatsu, parody of modern Japanese society and anime clichés

- One-Punch Man, parody of the superhero genre

- Pani Poni, parody of school-life anime and pop culture

- Panty & Stocking with Garterbelt, parody of American cartoons and magical girl tropes

- Pop Team Epic, parody of otaku culture, anime conventions, and internet memes

Western animation

[edit]- Animaniacs – parody of Hollywood, history, and pop culture

- BoJack Horseman – parody of Hollywood and celebrity culture

- Drawn Together – parody of reality TV and animation archetypes

- Family Guy – parody of films, celebrities, and other TV shows

- Futurama – parody of science fiction and futurism tropes

- Looney Tunes and Merrie Melodies – parody of fairy tales, Hollywood, and popular culture

- The Rocky and Bullwinkle Show – parody of Cold War politics, serialized dramas, and advertising

- Robot Chicken – parody of films, cartoons, video games, and toys

- Rick and Morty – parody of science fiction, especially Back to the Future and multiverse concepts

- South Park – parody of politics, celebrities, and current events

- The Simpsons – parody of American family life and popular culture

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ Dentith (2000) p.9

- ^ J.M.W. Thompson (May 2010). "Close to the Bone". Standpoint magazine. Archived from the original on 2016-04-16. Retrieved 2011-02-26.

- ^ "Parody". Encyclopedia of Diderot & d'Alembert - Collaborative Translation Project. June 2007. hdl:2027/spo.did2222.0000.811. Retrieved 3 October 2018.

- ^ Balducci, Anthony (28 November 2011). The Funny Parts: A History of Film Comedy Routines and Gags. McFarland. ISBN 978-0-7864-8893-3. Retrieved 3 October 2018 – via Google Books.

- ^ (Denith, 10)

- ^ Quoted in Hutcheon, 32.

- ^ (Hutcheon, 32)

- ^ Fain 2010, p. 201.

- ^ Davis, Evan R.; Nace, Nicholas D. (2019). "Introduction". Teaching Modern British and American Satire. New York: Modern Language Association of America. pp. 1–34.

- ^ Stevens, Anne H. (2019). "Parody". In Evan R. Davis; Nicholas D. Nace (eds.). Teaching Modern British and American Satire. New York: Modern Language Association of America. pp. 44–49.

- ^ a b c d e f Greenberg, Jonathan (2019). The Cambridge Introduction to Satire. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-107-68205-4.

- ^ Griffin, Dustin (1994). Satire: A Critical Reintroduction. University Press of Kentucky. ISBN 0-8131-1844-1.

- ^ a b c d e f Dentith, Simon (2000). Parody: The New Critical Idiom. Routledge. ISBN 0-415-18221-2.

- ^ a b c Jameson, Fredric (1983). "Postmodernism and Consumer Society". In Hal Foster (ed.). The Anti-Aesthetic: Essays on Postmodern Culture. Bay Press. pp. 111–125.

- ^ Tilmouth, Michael and Richard Sherr. "Parody (i)"' Grove Music Online, Oxford Music Online, accessed 19 February 2012 (subscription required)

- ^ Burkholder, J. Peter. "Borrowing", Grove Music Online, Oxford Music Online, accessed 19 February. 2012 (subscription required)

- ^ a b Sheinberg (2000) pp.141, 150

- ^ Stavans (1997) p.37

- ^ Bradbury, Malcolm No, not Bloomsbury p.53, quoting Boris Eikhenbaum:

Nearly all periods of artistic innovation have had a strong parodic impulse, advancing generic change. As the Russian formalist Boris Eichenbaum once put it: "In the evolution of each genre, there are times when its use for entirely serious or elevated objectives degenerates and produces a comic or parodic form....And thus is produced the regeneration of the genre: it finds new possibilities and new forms."

- ^ Hutcheon (1985) pp.28, 35

- ^ Boris Eikhenbaum Theory of the "Formal Method" (1925) and O. Henry and the Theory of the Short Story (1925)

- ^ "Christopher Rea". Department of Asian Studies, The University of British Columbia. Archived from the original on Aug 3, 2019.

- ^ Rea, Christopher (2 March 2016). "From the Year of the Ape to the Year of the Monkey". The China Story. Archived from the original on 2020-04-11. Retrieved 2019-02-17.

- ^ Christopher Rea, The Age of Irreverence: A New History of Laughter in China (Oakland, CA: University of California Press, 2015), pp. 52, 53.

- ^ Stavans (1997) p.31

- ^ Elizabeth Bellalouna, Michael L. LaBlanc, Ira Mark Milne (2000) Literature of Developing Nations for Students: L-Z p.50

- ^ a b Elices (2004) p.90 quotation:

From these words, it can be inferred that Genette's conceptualisation does not diverge from Hutcheon's, in the sense that he does not mention the component of ridicule that is suggested by the prefix paros. Genette alludes to the re-interpretative capacity of parodists in order to confer an artistic autonomy to their works.

- ^ a b Hutcheon (1985) p.50

- ^ a b c Hutcheon (1985) p.52

- ^ Yunck 1963

- ^ Hutcheon (1985)

- ^ Gérard Genette (1982) Palimpsests: literature in the second degree p.16

- ^ Sangsue (2006) p.72 quotation:

Genette individua la forma "piú rigorosa" di parodia nella "parodia minimale", consistente nella ripresa letterale di un testo conosciuto e nella sua applicazione a un nuovo contesto, come nella citazione deviata dal suo senso

- ^ Willett, Bec (17 December 2017). "Trapped in the Netflix at iO". Performink. Retrieved 23 March 2018.

- ^ Ayers, Mike (24 July 2014). "'Weird Al' Yankovic Explains His Secret Formula for Going Viral and Hitting No. 1". The Wall Street Journal. Retrieved 12 September 2015.

- ^ Hamersly, Michael. ""Weird Al" Yankovic brings his masterful musical parody to South Florida". Miami Herald. Archived from the original on March 30, 2024. Retrieved 12 September 2015.

- ^ "The Producers (1967)". imdb.com. 10 November 1968. Retrieved 17 October 2020.

- ^ Barnes, A. & Hearn, M. (1997) Kiss kiss bang bang: the unofficial James Bond film companion, Batsford, p. 63 ISBN 978-0-7134-8182-2

- ^ K. Baker ed., Unauthorized Versions (London 1990) Introduction p. xx–xxii

- ^ K. Baker ed., Unauthorized Versions (London 1990) p. 429

- ^ K. Baker ed., Unauthorized Versions (London 1990) p. 107

- ^ K. Baker ed., Unauthorized Versions (London 1990) p. 319

- ^ K. Baker ed., Unauthorized Versions (London 1990) p. 355

- ^ S. Cushman ed., The Princeton Encyclopedia of Poetry and Poetics (Princeton 2012) p. 1003

- ^ J. Thomas, Poetry's Playground (2007) p. 45–52

- ^ Quoted in S. Burt ed., The Cambridge History of American Poetry (Cambridge 2014)

- ^ Richard Stim (4 April 2013). "Summaries of Fair Use Cases". Stanford Copyright and Fair Use Center.

- ^ "Dr. Seuss Enterprises, LP v. Penguin Books". Google Scholar.

- ^ "The Tyee – Canwest Suit May Test Limits of Free Speech". The Tyee. 11 December 2008.

- ^ "Copyright Modernization Act (S.C. 2012, c. 20)". Justice Laws Website. 2019-11-15. Retrieved 2023-03-06.

- ^ The Stationery Office. (2006) Gowers Review of Intellectual Property. [Online]. Available at official-documents.gov.uk (Accessed: 22 February 2011).

- ^ UK Intellectual Property Office. (2009) Taking Forward the Gowers Review of Intellectual Property: Second Stage Consultation on Copyright Exceptions. [Online]. Available at ipo.gov.uk Archived 2011-05-17 at the Wayback Machine (Accessed: 22 February 2011).

- ^ "The Copyright and Rights in Performances (Quotation and Parody) Regulations 2014". Legislation.gov.uk. Retrieved 3 October 2018.

- ^ "Exceptions to copyright: Guidance for creators and copyright owners" (PDF). Gov.uk. Retrieved 3 October 2018.

- ^ "American begins one-year prison sentence in UAE for satirical video". the Guardian. 2013-12-23. Retrieved 2023-01-11.

- ^ "North Korea Furious Over Kim Jong Un Parody Dance Video". www.nbcnews.com. 2014-07-23. Retrieved 2023-07-06.

- ^ Christopher Rea, "Spoofing (e'gao) Culture on the Chinese Internet." In Humour in Chinese Life and Culture: Resistance and Control in Modern Times. Jessica Milner Davis and Jocelyn Chey, eds. Hong Kong: Hong Kong University Press, 2013, pp. 149–172

- ^ Appel, Alfred Jr.; Nabokov, Vladimir (1967). "An Interview with Vladimir Nabokov". Wisconsin Studies in Contemporary Literature. VIII (2): 127–152. doi:10.2307/1207097. JSTOR 1207097. Retrieved 28 Dec 2013.

- ^ An interview with The Onion, David Shankbone, Wikinews, November 25, 2007.

- ^ Pratt (1991)

References

[edit]- Dentith, Simon (2000). Parody (The New Critical Idiom). Routledge. ISBN 0-415-18221-2.

- Elices Agudo, Juan Francisco (2004) Historical and theoretical approaches to English satire

- Hutcheon, Linda (1985). "3. The Pragmatic Range of Parody". A Theory of Parody: The Teachings of Twentieth-Century Art Forms. New York: Methuen. ISBN 0-252-06938-2.

- Mary Louise Pratt (1991). "Arts of the Contact Zone". Profession. 91. New York: MLA: 33–40. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2008-10-26.

archived at University of Idaho, English 506, Rhetoric and Composition: History, Theory, and Research

. From Ways of Reading, 5th edition, ed. David Bartholomae and Anthony Petroksky (New York: Bedford/St. Martin's, 1999 - Sangsue, Daniel (2006) La parodia

- Sheinberg, Esti (2000) Irony, Satire, Parody and the Grotesque in the Music of Shostakovich

- Stavans, Ilan and Jesse H. Lytle, Jennifer A. Mattson (1997) Antiheroes: Mexico and its detective novel

- Ore, Johnathan (2014) Youtuber Shane Dawsons fans revolt after Sony pulls his Taylor Swift parody video

Further reading

[edit]- Bakhtin, Mikhail (1981). Michael Holquist (ed.). The Dialogic Imagination: Four Essays. Translated by Caryl Emerson. Austin and London: University of Texas Press. ISBN 0-292-71527-7.

- Gates, Henry Louis Jr. (1988). The Signifying Monkey: A Theory of Afro-American Literary Criticism. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-503463-5.

- David Bartholomae; Anthony Petroksky, eds. (1999). Ways of Reading (5th ed.). New York: Bedford/St. Martin's. ISBN 978-0-312-45413-5.

An anthology including Arts of the Contact Zone

- Rose, Margaret (1993). Parody: Ancient, Modern and Post-Modern. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-41860-7.

- Caponi, Gena Dagel (1999). Signifyin(g), Sanctifyin', & Slam Dunking: A Reader in African American Expressive Culture. University of Massachusetts Press. ISBN 1-55849-183-X.

- Harries, Dan (2000). Film Parody. London: BFI. ISBN 0-85170-802-1.

- Pueo, Juan Carlos (2002). Los reflejos en juego (Una teoría de la parodia). Valencia (Spain): Tirant lo Blanch. ISBN 84-8442-559-2.

- Gray, Jonathan (2006). Watching with The Simpsons: Television, Parody, and Intertextuality. New York: Routledge. ISBN 0-415-36202-4.

- John Gross, ed. (2010). The Oxford Book of Parodies. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-954882-8.

- Fain, Gordon L. (2010). Ancient Greek Epigrams: Major Poets in Verse Translation. Berkeley: University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-26579-0.

External links

[edit]Parody

View on GrokipediaDefinition and Terminology

Etymology and Core Elements

The term "parody" originates from the Ancient Greek word parōidía (παρῳδία), composed of pará (παρά, meaning "beside" or "counter") and ōidḗ (ᾠδή, meaning "song" or "ode"), denoting a "burlesque song" or a composition performed alongside an original ode for mocking effect.[3][11] This etymological root reflects parody's initial function in classical antiquity as a parallel or counterpoint to serious poetic forms, often involving rhythmic imitation with altered content to evoke ridicule.[4] The word entered Latin as parodia before being adopted into English around the late 16th century, with the Oxford English Dictionary tracing its earliest recorded use to Ben Jonson's 1598 play Every Man in His Humour, where it describes a satirical verse imitation.[3] At its core, parody constitutes a creative imitation that replicates the stylistic, structural, or thematic elements of an original work, genre, or author, but distorts them through exaggeration, inversion, or absurdity to generate humor or critique.[1] This imitation targets recognizable conventions—such as linguistic patterns, narrative tropes, or performative quirks—amplifying their flaws or inherent ridiculousness to expose pretensions, without requiring the parodist's endorsement of the original's viewpoint.[2] Unlike mere pastiche, which emulates admiringly, parody inherently employs irony or satire, often subverting the source material's intent to highlight its absurdities or societal implications, as evidenced in classical examples like the Hellenistic Batrachomyomachia, a mock epic mimicking Homer's heroic style in a trivial frog-mouse war.[12] Essential to parody is the audience's familiarity with the target, enabling the comedic recognition of divergence, which distinguishes it from unrelated spoofs lacking systematic stylistic mimicry.[1]Distinctions from Related Forms

Parody is distinguished from satire primarily by its reliance on direct imitation of a specific work's style, structure, or content to evoke ridicule or critique of that work itself, whereas satire employs humor, irony, or exaggeration to target broader societal vices, follies, or institutions without requiring such targeted mimicry.[13][14] This distinction holds in literary analysis, where parody functions through "echoic mention" of the original—replicating its markers to subvert them—while satire often uses pretense or indirect sarcasm to expose human weaknesses.[13] For instance, Alexander Pope's The Rape of the Lock (1712) parodies epic conventions to mock aristocratic triviality by mimicking heroic form, but its satirical aim extends to class pretensions beyond mere stylistic echo.[15] In contrast to pastiche, parody incorporates a critical edge that undermines or mocks the imitated source, rather than assembling stylistic elements from multiple influences as a neutral homage or collage without ridicule.[16] Pastiche, as defined in literary theory, evokes admiration for the source styles—often flattening them into a composite without the transformative mockery essential to parody's "repetition with critical difference."[16][15] John Ashbery's poetry, for example, employs pastiche by blending modernist and postmodern styles reverentially, whereas parody, like Max Beerbohm's caricatured imitations of Victorian authors in A Christmas Garland (1912), deliberately distorts to highlight pretensions. Burlesque differs from parody in its grotesque exaggeration of either high subjects in low styles (Hudibrastic) or low subjects in elevated ones, aiming for comic debasement rather than precise stylistic replication for targeted critique.[17] Parody maintains closer fidelity to the original's markers before subverting them, as in Jonathan Swift's A Modest Proposal (1729), which parodies economic treatises' dispassionate tone to mock policy discourse, unlike burlesque's broader inversion of dignity levels, such as Samuel Butler's Hudibras (1663–1678), which travesties heroic couplets to ridicule Puritanism through vulgarity.[17] Spoofs, often lighter and more accessible than parodies, imitate genres or conventions broadly for humorous effect without the depth of critique or necessary reference to a singular work, functioning as playful send-ups rather than interrogative distortions.[1] This makes spoofs akin to general lampoons, as in films like Airplane! (1980), which spoofs disaster movie tropes collectively, whereas parody, such as The Wind Done Gone (2001) by Alice Randall, specifically reworks Gone with the Wind's narrative and style to challenge its racial portrayals. Parody transcends mere imitation by infusing ridicule into the replication, distinguishing it from homage-like mimicry that flatters or pays tribute without subversion; imitation alone, as in neoclassical exercises, lacks parody's ironic intent to expose flaws in the source.[18] Similarly, while caricature exaggerates physical or stylistic traits visually for distortion, parody operates textually or multimodally through structural and linguistic fidelity turned against the original, not mere feature amplification.[19]Historical Development

Ancient and Classical Origins

The term parōidía (παρῳδία) in ancient Greek denoted a burlesque song or poem that imitated another work alongside it, often for mock-heroic or satirical effect, derived from para- ("beside" or "mock") and ōidḗ ("song" or "ode").[3] This form emerged in the archaic period, with the Margites—a poem featuring a bumbling anti-hero in epic style, attributed to Homer and referenced by Archilochus around 670 BCE—serving as an early exemplar of parody targeting Homeric conventions.[20] Hipponax, active in the mid-6th century BCE, incorporated parodic imitation into iambic poetry, exaggerating epic grandeur to ridicule pretension.[20] By the 5th century BCE, parody proliferated in Old Comedy, particularly through Aristophanes (c. 446–386 BCE), whose plays systematically mimicked and distorted tragic styles for amusement. In The Frogs (405 BCE), Dionysus judges a contest between the ghosts of Aeschylus and Euripides, parodying their grandiose language and metrics—Aeschylus with bombastic compounds, Euripides with colloquial realism—to critique dramatic decline.[21][20] Aristophanes also parodied philosophers like Socrates in The Clouds (423 BCE), portraying him as a sophist suspended in a basket, inverting intellectual pursuits into absurdity.[22] Hegemon of Thasos, contemporary in the early 5th century BCE, composed direct parodies of Homer, blending epic form with trivial or grotesque subjects.[20] The pseudo-Homeric Batrachomyomachia (Battle of the Frogs and Mice), likely composed between the 5th and 3rd centuries BCE but circulated as archaic, epitomized mock-epic by narrating an animal skirmish in Iliad-like dactylic hexameter, complete with divine interventions and heroic similes.[21] In Roman literature, parody lacked the formalized Greek tradition but manifested in comedic adaptations and verse satire, influenced by Hellenistic models. Plautus (c. 254–184 BCE) and Terence (c. 185–159 BCE) infused Roman adaptations of Greek New Comedy with exaggerated imitations of stock characters and plots, often heightening farcical elements for ridicule.[22] Horace's Satires (c. 35–30 BCE) employed parodic echoes of earlier poetry to lampoon social affectations, such as mimicking Lucilian invective while adopting a conversational tone to undercut pretentiousness.[23] Later works like Petronius' Satyricon (c. 60 CE) included parodic vignettes, such as the Cena Trimalchionis, which travestied epic banquets and philosophical dialogues with vulgar excess. Roman emphasis on satura—a broader, indigenous satirical mode—often subsumed parody into moral critique rather than stylistic imitation alone.[24]Medieval to Enlightenment Periods

In the medieval period, parody often intertwined with carnivalistic folk traditions, employing imitation and exaggeration to subvert authority and highlight societal absurdities, as theorized in analyses of the era's literary practices. Beast epics like the Reynard the Fox cycle, circulating from the 12th century in Low Countries vernaculars, used anthropomorphic animals to parody chivalric romances and courtly hierarchies, portraying the cunning fox Reynard as a trickster outwitting noble beasts representing clergy and nobility.[25] These tales critiqued feudal power structures through inverted moral lessons, with Reynard's deceptions mirroring real-world corruption among elites.[26] Fabliaux and mock-heroic poems further exemplified parody, ridiculing epic conventions and religious piety. The early 14th-century Battle of Anesin, a 49-line Old French poem by Thumas of Bailloel preserved in British Library manuscript Royal 20 A XVII, mimicked grandiose chronicles of battles like Bouvines (1214) by depicting chaotic peasant skirmishes escalating to absurd multinational warfare, resolved not by valor but by a pilgrim's wine-induced truce, thereby exposing the futility and brutality of chivalric glorification.[27] Late medieval religious parodies, including liturgical spoofs, inverted sacred rites and hymns to lampoon clerical hypocrisy and monastic excesses, often circulating anonymously to evade censure.[28] Transitioning into the Renaissance and Enlightenment, parody refined as a tool for intellectual critique, adopting neoclassical imitation of classical forms to target pedantry and fanaticism. Jonathan Swift's A Tale of a Tub (1704) parodied allegorical religious tracts and modern philosophy through fragmented, digressive narratives mimicking Puritan and enthusiast writings, exposing sectarian divisions in post-Reformation England.[29] Similarly, Swift's Gulliver's Travels (1726) imitated 17th- and early 18th-century voyage accounts, such as William Dampier's A New Voyage Round the World (1697), by exaggerating exploratory tropes into fantastical critiques of European governance, science, and human vice.[30] Alexander Pope's The Dunciad (1728, with major expansion in 1742) employed mock-epic parody, inverting Virgilian grandeur to deride Grub Street hacks and cultural decline, allotting dunces heroic quests in a underworld of dullness ruled by the goddess Dulness.[29] These works leveraged parody's imitative precision to dismantle pretensions, aligning with Enlightenment emphases on reason over superstition, though often risking charges of libel amid era-specific censorship constraints.[31]19th and 20th Centuries

In the nineteenth century, parody solidified as a literary tool for subverting poetic and narrative conventions amid Romantic individualism and Victorian propriety. Lord Byron's Don Juan (1819–1824), composed in ottava rima, parodied epic traditions exemplified by Ariosto and Tasso, juxtaposing heroic form with prosaic adventures to ironize the Byronic hero and societal hypocrisies.[32] Lewis Carroll's Alice's Adventures in Wonderland (1865) incorporated explicit parodies of moralistic verse, transforming Isaac Watts's "Against Idleness and Mischief" (1715) into the Caterpillar's anarchic "How doth the little crocodile," thereby critiquing rote pedagogy and imperial didacticism.[33] Periodicals advanced visual parody through caricature, as in Punch (established 1841), where illustrators like John Tenniel exaggerated politicians' features and mannerisms to mock parliamentary debates and class pretensions, reaching circulations exceeding 100,000 by mid-century.[34] The twentieth century witnessed parody's migration from print to emergent mass media, amplifying its reach via film, comics, and periodicals while retaining literary roots. Max Beerbohm's A Christmas Garland (1912) comprised seventeen vignettes parodying contemporaries—such as Henry James's convoluted syntax in "The Mote in the Middle Distance" and Rudyard Kipling's imperialism in "P.C. X 36"—to expose stylistic affectations without descending into mere ridicule.[35] Silent cinema rapidly adopted parody, with comedians exploiting rapid production cycles; Stan Laurel's Mud and Sand (1922), released mere months after Rudolph Valentino's Blood and Sand, mimicked the bullfighter drama's poses and intertitles for slapstick effect, grossing comparably at the box office.[12] Mad magazine (debuting 1952 under editor Harvey Kurtzman) initially targeted horror comics like EC's Tales from the Crypt before broadening to skewer television, advertising, and Cold War conformity, selling over 2 million copies monthly by 1956 and spawning imitators that eroded Comics Code restrictions.[36] Parody's institutionalization reflected technological democratization, enabling rapid imitation of cultural artifacts; by the 1940s, animated shorts like the Warner Bros. Dover Boys at Pimento University (1942) travestied boys' adventure serials such as the Rover Boys (1899–1926), substituting bumbling Ivy League cadets for heroic exploits to lampoon juvenile escapism. This era's parodies often balanced homage with critique, as in musical deconstructions by Spike Jones, whose 1940s orchestra mangled classics like Tchaikovsky's Nutcracker Suite with gunshots and whoopee cushions, selling millions of records while challenging orchestral pretensions.[37] Legal tensions emerged, with parodists invoking transformative intent against copyright claims, presaging doctrinal shifts.[38]Postmodern and Digital Eras

In the postmodern era, parody shifted from primarily ridiculing imitation to a more ambivalent form of intertextual repetition with critical distance, emphasizing self-reflexivity and the interrogation of cultural narratives rather than outright mockery. Linda Hutcheon, in her 1985 book A Theory of Parody: The Teachings of Twentieth-Century Art Forms, defined parody as "repetition with difference," a mode that both honors and critiques its targets, thereby exposing ideological contradictions without fully endorsing or rejecting them.[39] This framework positioned parody as central to postmodern aesthetics, where it blurred boundaries between homage, pastiche, and satire, often serving to deconstruct grand narratives in literature, art, and media.[40] For instance, Thomas Pynchon's 1966 novel The Crying of Lot 49 parodies detective fiction and conspiracy tropes by layering absurd entropy onto conventional plots, undermining reader expectations of resolution and authority.[41] Similarly, Kurt Vonnegut's Slaughterhouse-Five (1969) employs non-linear parody of war narratives and science fiction to critique linear historicity and human absurdity, integrating alien perspectives to highlight temporal fragmentation.[42] The digital era, beginning with widespread internet access in the 1990s, accelerated parody's proliferation through accessible, user-generated formats that democratized creation and dissemination. Richard Dawkins coined the term "meme" in 1976 to describe cultural replicators analogous to genes, but digital memes emerged as visual and textual parodies around 1982 with early emoticons like ":-)", evolving into viral phenomena by the mid-2000s on platforms such as 4chan and early social media.[43] The 1996 "Dancing Baby" animation, a 3D-rendered cherub performing to music, exemplified early digital parody by mimicking infantile novelty while satirizing emerging CGI hype in media.[44] By 2007, meme culture exploded with formats like image macros on sites like Reddit, parodying celebrities, politics, and trends through ironic juxtaposition, such as "Advice Animals" templates that exaggerated stereotypes for humorous critique.[45] This era's parodies often thrived on remixability, with platforms enabling rapid iteration—evident in the 2020s surge of TikTok duets and reaction videos that layer user commentary over originals, amplifying subversive reinterpretations at scale.[46] Advancements in artificial intelligence since the early 2020s have introduced automated parody generation, leveraging tools like text-to-video models to produce synthetic imitations that mimic styles with minimal human input. For example, AI-generated country songs parodying traditional genres, such as the 2025 viral track "Country Girls Make Do," replicate twangy vocals and lyrics to satirize rural tropes, often blending explicit content with algorithmic novelty.[47] These developments enable hyper-personalized parodies but raise causal concerns over authenticity, as AI's pattern-matching can inadvertently propagate biases from training data or enable deceptive deepfakes, as seen in 2025 political videos mimicking leaders for satirical effect.[48] Empirical analyses indicate that while AI parodies enhance creative output— with over 1 million AI-assisted videos uploaded monthly to platforms like YouTube by mid-2025— they challenge traditional parody's intentionality, shifting emphasis from human critique to machine recombination.[49] This evolution underscores parody's adaptation to technological affordances, prioritizing viral dissemination over depth, though legal frameworks lag in addressing ownership of AI-derived derivatives.[50]Techniques and Forms Across Media

Literary and Poetic Techniques

Parody in literature relies on the deliberate imitation of an established author's style, tone, narrative structure, or thematic conventions, amplified through exaggeration to elicit humor or expose absurdities.[2] This technique presupposes audience familiarity with the target, allowing the parody to subvert expectations by distorting recognizable elements such as syntax, diction, or plot devices.[2] Unlike mere pastiche, which emulates without ridicule, literary parody inherently critiques by highlighting stylistic excesses or logical inconsistencies in the original.[19] Key methods include hyperbole, where traits of the source material are overstated to ridiculous proportions, as in Seth Grahame-Smith's Pride and Prejudice and Zombies (2009), which infuses Jane Austen's restrained Regency prose with grotesque zombie violence to mock sentimental romance tropes.[2] Inversion reverses conventional patterns, such as William Shakespeare's Sonnet 130 (1609), which parodies Petrarchan love poetry by denying hyperbolic flattery—"My mistress' eyes are nothing like the sun"—to deflate idealized beauty standards through blunt realism.[19] Trivialization diminishes epic or grave subjects to the banal, evident in Alexander Pope's The Rape of the Lock (1712), a mock-heroic poem that elevates a petty society scandal to Homeric scale with supernatural machinery and battles over a lock of hair.[19] These devices often overlap, as in Miguel de Cervantes' Don Quixote (1605–1615), which hyperbolically inverts chivalric romance ideals, portraying a delusional knight tilting at windmills in imitation of outdated heroic quests.[2] In poetry, parody emphasizes formal replication of meter, rhyme schemes, and prosodic patterns while injecting incongruous or absurd content to undermine solemnity. For example, Kenneth Koch's "Variations on a Theme by William Carlos Williams" (1962) apes Williams' terse, imagistic free verse—short lines focused on everyday objects—but applies it to the improbable act of demolishing a house with an ax, exaggerating minimalism into surreal disruption.[2][19] Parodists targeting structured forms like sonnets or ballads preserve iambic rhythms or couplets but warp diction or logic; Lewis Carroll's "You Are Old, Father William" (1865) mirrors the didactic moralism and alternating rhyme of Robert Southey's "The Old Man's Comforts and How He Gained Them" (1799) yet inverts it with acrobatic feats and gluttony to satirize paternal advice. Such techniques exploit poetry's rigidity, where metrical fidelity heightens the comedic clash between form and folly, as seen in parodies of Henry Wadsworth Longfellow's trochaic tetrameter in The Song of Hiawatha (1855), often mimicked to lampoon its repetitive, chant-like cadence with trivial narratives.[51] Stella Gibbons' Cold Comfort Farm (1932) extends these to prose poetry parody, trivializing rural gothic excess through parodic inversion of overwrought pastoral idioms.[19] Overall, these methods prioritize precision in imitation to ensure the parody's critique lands through recognizable distortion rather than invention.Visual, Film, and Theatrical Forms

Parody in visual arts utilizes exaggeration, distortion, and ironic imitation to critique societal vices, often via paintings, illustrations, and caricatures. Caricature techniques originated in ancient Egypt, Greece, and Rome through exaggerated sculptures and drawings, evolving into a distinct form by the 16th century in Europe amid the Reformation's anti-clerical satires.[52][53] By the 17th century, artists like Jan Brueghel the Younger employed these methods in works such as Satire on Tulip Mania (c. 1640), depicting monkeys frenziedly trading oversized tulip bulbs to ridicule the speculative bubble that peaked in 1637, symbolizing human folly in economic excess.[54] In the 19th century, Honoré Daumier's lithographs caricatured French political figures and bourgeoisie, amplifying physical traits and absurd scenarios to expose corruption and class pretensions.[52] Film parody, a comedy subgenre, lampoons specific movies, genres, or tropes through hyperbolic imitation, irony, and satirical reversal of expectations. Techniques include visual gags, anachronistic elements, and escalation of clichés to absurdity, as defined in cinematic analysis.[55] Early examples appeared in silent era shorts, but the form proliferated post-1940s with spoofs like the Marx Brothers' Duck Soup (1933), mocking diplomacy via chaotic sequences.[55] The 1970s-1980s marked a peak with Mel Brooks' productions, such as Young Frankenstein (1974), which parodies Universal horror films through deliberate genre mimicry and sight gags, and Airplane! (1980), directed by Jim Abrahams and others, satirizing disaster films like Airport (1970) with nonstop verbal and visual non-sequiturs.[55] These works critique formulaic storytelling while relying on audience familiarity for humor. Animation contributed visual-film hybrids, exemplified by Warner Bros.' The Dover Boys at Pimento University (1942), a Chuck Jones-directed short parodying boys' adventure serials like the Rover Boys books through frantic pacing, simplified character designs, and ironic narration.[55] Theatrical parody stages exaggerated imitations of dramatic conventions, scripts, or performances to underscore inherent absurdities or cultural targets. Historical roots lie in ancient Greek comedy, where Aristophanes parodied tragedians like Euripides in plays such as The Frogs (405 BCE), using burlesque elements to debate artistic merit.[29] In 18th-19th century burlesque, troupes like England's Adelphi Theatre mocked high opera and Shakespeare via low comedy, cross-dressing, and topical allusions, as in Robert Brough's adaptations.[12] 20th-century American theater saw self-referential spoofs proliferate in the 1920s, with works lampooning Broadway excesses through meta-theatrical devices.[56] Modern instances include Michael Frayn's Noises Off (1982), which parodies farce rehearsals by revealing backstage pandemonium mirroring onstage chaos, performed in over 1,500 productions worldwide by 2023.[12] These forms maintain parody's core by transforming solemnity into ridicule, often without musical integration.Musical and Auditory Parodies

Musical parody entails the imitation of an existing composition's melody, rhythm, harmony, or stylistic elements, typically with altered lyrics or thematic content to evoke humor, satire, or commentary, distinguishing it from serious contrapuntal reuse in earlier eras.[57] In auditory parodies, this extends to non-musical soundscapes, such as exaggerated vocal inflections, sound effects, or spoken-word mimicry that lampoons original audio sources.[38] Unlike literal covers, parodies rely on recognizable distortion for effect, often preserving core hooks while subverting expectations through incongruous substitutions or amplifications.[37] The technique traces to Renaissance "parody masses," where composers like Josquin des Prez repurposed secular chansons into polyphonic sacred works, a method peaking in the 15th and 16th centuries with over 100 documented examples by 1540, prioritizing contrapuntal elaboration over humor.[57] By the Classical period, satirical intent emerged, as in Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart's A Musical Joke (K. 522, composed 1782), which caricatures amateur string quartets through deliberate discords, botched entries, and errant horn calls, critiquing dilettante performers of the era.[58] Johann Sebastian Bach employed parody non-humorously, adapting secular cantatas into sacred ones for his Mass in B Minor (completed 1749), recycling melodies like "Quoniam tu solus sanctus" from a 1733 birthday cantata.[59] In the 20th century, popular music amplified humorous parody via lyric overhauls on familiar tunes, exemplified by "Weird Al" Yankovic's Eat It (1984), a food-obsessed rewrite of Michael Jackson's Beat It that sold over 500,000 copies and earned platinum certification, demonstrating commercial viability through stylistic fidelity and absurd topical shifts.[37] Techniques include rhythmic preservation for singability, rhyme scheme adherence, and thematic inversion—e.g., Yankovic's Amish Paradise (1996) transposes Coolio's gangsta rap Gangsta's Paradise into rural Amish life, peaking at No. 53 on Billboard Hot 100.[60] Auditory extensions appear in satirical ensembles like Spike Jones's 1940s orchestra, which mangled classics such as Der Fuehrer's Face (1942), using kazoos, washboards, and gunshot effects to mock fascism, selling millions during World War II.[60] Key methods encompass reiteration (repeating motifs with ironic twists), inversion (flipping emotional tone, e.g., upbeat melody for morbid lyrics), and exaggeration (amplifying instrumentation, as in PDQ Bach's pseudohistorical spoofs by Peter Schickele, parodying Baroque excesses since 1958).[61] These preserve recognizability—essential for efficacy—while causal critique arises from juxtaposing original gravitas against triviality, as in Jacques Offenbach's opéras bouffes (1850s–1870s), which lampooned Wagnerian grandeur through burlesque orchestration.[62] Empirical success metrics, like Yankovic's 16 top-40 singles from 1983–2014, underscore parody's role in cultural digestion without supplanting originals, often requiring artist permissions to mitigate disputes.[38]Digital, Internet, and AI-Generated Variants

Digital parodies proliferated with the rise of Web 2.0 platforms in the mid-2000s, enabling user-generated content through easy video editing and subtitle overlays. One prominent example is the "Downfall" parodies, which originated from a 2004 German film depicting Adolf Hitler's final days; creators began subtitling the bunker's rant scene in 2008 to satirize modern events, such as Hitler's fictional reaction to being banned from Xbox Live, amassing millions of views on YouTube before some were removed in 2010 due to copyright claims by the filmmakers.[63][64][65] These edits transformed dramatic footage into humorous critiques of technology, politics, and pop culture, illustrating how digital tools democratized parody by requiring minimal technical skill beyond basic software like Adobe Premiere or free online editors. Internet memes emerged as a concise, image-based parody form, often repurposing templates from stock photos, films, or advertisements to mock societal trends or public figures through caption overlays and ironic juxtaposition. Early instances trace to the late 1990s, such as "All Your Base Are Belong to Us" from a 1989 game mistranslation, but proliferation accelerated post-2005 with sites like 4chan and Reddit, where memes parody via exaggeration and intertextuality, as seen in formats like "Distracted Boyfriend" (2017 origin) applied to political scandals.[66] Scholars note memes' parodic essence lies in their transformative reuse, evolving rapidly through viral sharing—e.g., over 1 billion daily TikTok views by 2020 for parody challenges—while evading traditional media gatekeeping.[66] Remix culture further expanded digital parody via mashups, where audio, video, and images from disparate sources are recombined for satirical effect, facilitated by software like Audacity or Final Cut Pro. This "read-write" approach, prominent since the early 2000s on platforms like YouTube, includes music-video parodies blending pop tracks with absurd visuals, such as early G.I. Joe PSA edits mocking 1980s public service announcements for over-the-top seriousness.[67] By 2015, remix parodies were defended as commentary akin to quotation, though frequent DMCA takedowns highlighted tensions between creativity and IP enforcement.[68] AI-generated variants, enabled by large language and diffusion models since 2022, automate parody creation, producing text, images, or videos that mimic and distort originals for humor or critique. Tools like ChatGPT and Midjourney have yielded satirical outputs, such as AI-scripted skits parodying corporate jargon or generated artwork exaggerating celebrity features, often shared on social media for viral mockery.[69] A 2024 example involved Will Smith recreating an AI-deepfake video of himself ineptly eating spaghetti—originally viral in 2023 for its eerie uncanniness—to highlight generative AI's limitations in realistic motion and expression.[70] These variants raise distinct challenges, as AI's pattern-matching can amplify biases in training data, yet they extend parody's reach by lowering barriers for non-experts, with outputs like deepfake political satires proliferating on platforms by 2025 despite ethical concerns over misinformation.[69]Legal and Ethical Frameworks

United States Fair Use Doctrine

The fair use doctrine in United States copyright law, codified at 17 U.S.C. § 107, permits limited use of copyrighted material without the owner's permission for purposes such as criticism, comment, news reporting, teaching, scholarship, or research.[71] Parody qualifies as a potential fair use when it transforms the original work by adding new expression, meaning, or message, particularly through humorous imitation that critiques or comments on the original itself.[9] Courts evaluate fair use on a case-by-case basis using four statutory factors, with parody often favoring the user under the first factor if it is transformative rather than merely derivative.[72] The first factor assesses the purpose and character of the use, weighing whether it is commercial or nonprofit and, crucially, transformative. In parody contexts, commercial nature does not preclude fair use; the Supreme Court in Campbell v. Acuff-Rose Music, Inc. (1994) ruled that 2 Live Crew's rap parody of Roy Orbison's "Oh, Pretty Woman"—which altered lyrics to comment on the original's themes of romance and beauty—constituted fair use despite its commercial release, as it added new satirical expression without supplanting the market for the original.[73] Transformative parodies that target the original work for criticism weigh more heavily in favor of fair use than those using it merely as a vehicle for broader satire, which may fail if they do not critique the source material directly.[8] The second factor examines the nature of the copyrighted work, favoring fair use less for highly creative expressions like songs or novels compared to factual works. Parodies of expressive works, such as in Campbell, still often succeed if the other factors support transformation.[72] The third factor considers the amount and substantiality of the portion used in relation to the whole, both quantitatively and qualitatively; parodies may borrow the "heart" of the original if necessary to evoke it for critique, as the Court permitted in Campbell by allowing use of the song's recognizable opening riff and chorus.[73] Excessive borrowing without sufficient transformation, however, can undermine a fair use claim.[9] The fourth factor evaluates the effect of the use on the potential market for or value of the original, prohibiting uses that serve as substitutes. Parodies typically do not harm the market if they critique rather than compete with the original, though superseding demand—such as a parody so effective that audiences prefer it over the source—could weigh against fair use.[72] In Campbell, the Court found no significant market harm, emphasizing that parody's critical purpose distinguishes it from market-replacing derivatives.[73] Overall, while parody enjoys strong fair use protection, outcomes depend on balanced application of the factors, with courts rejecting claims where imitation lacks meaningful commentary or excessively exploits the original without adding value.[71]International Exceptions and Fair Dealing

In international copyright law, exceptions for parody are typically narrower than the United States' fair use doctrine, often requiring the use to serve a specific permitted purpose such as criticism, review, or humor, and subjecting it to a fairness assessment or the Berne Convention's three-step test.[74] The Berne Convention for the Protection of Literary and Artistic Works (1886, as amended) does not mandate a parody exception but permits limitations on exclusive rights under Article 9(2), provided they meet three criteria: the exception applies to special cases, does not conflict with the normal exploitation of the work, and does not unreasonably prejudice the rights holder's legitimate interests. This test, incorporated into treaties like the TRIPS Agreement (1994), constrains parody defenses globally, emphasizing balance between creators' rights and public interests in expression.[75] In the European Union, Directive 2001/29/EC on the harmonization of certain aspects of copyright in the information society (InfoSoc Directive) provides an optional exception under Article 5(3)(k) for "parody, pastiche and caricature," allowing member states to implement it without requiring prior permission from rights holders, though application must align with the three-step test.[76] The European Court of Justice in Deckmyn v Vandersteen (2014) clarified that for the exception to apply, a parody must evoke the original work, display noticeable differences, and constitute an expression of humor or mockery, while avoiding discrimination or harm to the work's original message.[77] National implementations vary; for instance, France recognizes parody as a longstanding exception rooted in case law, requiring it to be humorous, transformative, and non-substitutive of the original.[76] Commonwealth jurisdictions employ fair dealing regimes, which enumerate specific purposes unlike the open-ended U.S. approach. In the United Kingdom, the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988 (as amended by the Digital Economy Act 2010, effective 2014) introduced Section 30A, permitting fair dealing for caricature, parody, or pastiche without specifying a need for criticism of the original work, provided the use is fair and acknowledges the source where practicable.[78] Canada's Copyright Act, updated via the Copyright Modernization Act 2012, explicitly includes "parody or satire" among fair dealing purposes, expanding from prior categories like criticism and review; courts assess fairness via factors such as purpose, amount copied, alternatives available, and market impact, as established in CCH Canadian Ltd. v. Law Society of Upper Canada (2004).[79] Australia's Copyright Act 1968 lacks a dedicated parody provision but accommodates it under fair dealing for criticism or review, with courts evaluating on a case-by-case basis under similar fairness criteria, though parodists face higher evidentiary burdens than under U.S. fair use.[80] These exceptions reflect a causal tension between incentivizing original creation through strong protections and enabling satirical expression to foster discourse, but empirical analyses indicate fair dealing's enumerated limits result in fewer successful parody defenses compared to fair use, particularly for commercial works.[81] Jurisdictions without explicit parody carve-outs, such as Japan, rely on general quotation or transformative use clauses, often leading to stricter enforcement favoring rights holders.[80] Overall, international frameworks prioritize non-conflicting, limited uses, with ongoing debates in bodies like the World Intellectual Property Organization (WIPO) advocating for clearer harmonization to support parody's role in cultural critique without eroding economic incentives.[82]Recent Developments and Landmark Cases