Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Lead dioxide

View on Wikipedia | |

| |

| Names | |

|---|---|

| IUPAC name

Lead(IV) oxide

| |

| Other names

Plumbic oxide

Plattnerite | |

| Identifiers | |

3D model (JSmol)

|

|

| ChemSpider | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.013.795 |

| EC Number |

|

PubChem CID

|

|

| RTECS number |

|

| UNII | |

| UN number | 1872 |

CompTox Dashboard (EPA)

|

|

| |

| |

| Properties | |

| PbO2 | |

| Molar mass | 239.1988 g/mol |

| Appearance | dark-brown, black powder |

| Density | 9.38 g/cm3 |

| Melting point | 290 °C (554 °F; 563 K) decomposes |

| insoluble | |

| Solubility | soluble in acetic acid insoluble in alcohol |

Refractive index (nD)

|

2.3 |

| Structure | |

| hexagonal | |

| Hazards | |

| GHS labelling: | |

| |

| Danger | |

| H272, H302, H332, H360, H372, H373, H410 | |

| P201, P202, P210, P220, P221, P260, P261, P264, P270, P271, P273, P280, P281, P301+P312, P304+P312, P304+P340, P308+P313, P312, P314, P330, P370+P378, P391, P405, P501 | |

| NFPA 704 (fire diamond) | |

| Flash point | Non-flammable |

| Safety data sheet (SDS) | External MSDS |

| Related compounds | |

Other cations

|

Carbon dioxide Silicon dioxide Germanium dioxide Tin dioxide |

| Lead(II) oxide Lead(II,IV) oxide | |

Related compounds

|

Thallium(III) oxide Bismuth(III) oxide |

Except where otherwise noted, data are given for materials in their standard state (at 25 °C [77 °F], 100 kPa).

| |

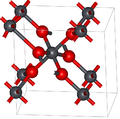

Lead(IV) oxide, commonly known as lead dioxide, is an inorganic compound with the chemical formula PbO2. It is an oxide where lead is in an oxidation state of +4.[1] It is a dark-brown solid which is insoluble in water.[2] It exists in two crystalline forms. It has several important applications in electrochemistry, in particular as the positive plate of lead acid batteries.

Properties

[edit]Physical

[edit]

Lead dioxide has two major polymorphs, alpha and beta, which occur naturally as rare minerals scrutinyite and plattnerite, respectively. Whereas the beta form had been identified in 1845,[3] α-PbO2 was first identified in 1946 and found as a naturally occurring mineral 1988.[4]

The alpha form has orthorhombic symmetry, space group Pbcn (No. 60), Pearson symbol oP12, lattice constants a = 0.497 nm, b = 0.596 nm, c = 0.544 nm, Z = 4 (four formula units per unit cell).[4] The lead atoms are six-coordinate.

The symmetry of the beta form is tetragonal, space group P42/mnm (No. 136), Pearson symbol tP6, lattice constants a = 0.491 nm, c = 0.3385 nm, Z = 2[5] and related to the rutile structure and can be envisaged as containing columns of octahedra sharing opposite edges and joined to other chains by corners. This contrasts with the alpha form where the octahedra are linked by adjacent edges to give zigzag chains.[4]

Chemical

[edit]Lead dioxide decomposes upon heating in air as follows:

The stoichiometry of the end product can be controlled by changing the temperature – for example, in the above reaction, the first step occurs at 290 °C, second at 350 °C, third at 375 °C and fourth at 600 °C. In addition, Pb2O3 can be obtained by decomposing PbO2 at 580–620 °C under an oxygen pressure of 1,400 atm (140 MPa). Therefore, thermal decomposition of lead dioxide is a common way of producing various lead oxides.[6]

Lead dioxide is an amphoteric compound with prevalent acidic properties. It dissolves in strong bases to form the hydroxyplumbate ion, [Pb(OH)6]2−:[2]

- PbO2 + 2 NaOH + 2 H2O → Na2[Pb(OH)6]

It also reacts with basic oxides in the melt, yielding orthoplumbates M4[PbO4].

Because of the instability of its Pb4+ cation, lead dioxide reacts with hot acids, converting to the more stable Pb2+ state and liberating oxygen:[6]

- 2 PbO2 + 2 H2SO4 → 2 PbSO4 + 2 H2O + O2

- 2 PbO2 + 4 HNO3 → 2 Pb(NO3)2 + 2 H2O + O2

- PbO2 + 4 HCl → PbCl2 + 2 H2O + Cl2

However these reactions are slow.

Lead dioxide is well known for being a good oxidizing agent, with an example reactions listed below:[7]

- 2 MnSO4 + 5 PbO2 + 6 HNO3 → 2 HMnO4 + 2 PbSO4 + 3 Pb(NO3)2 + 2 H2O

- 2 Cr(OH)3 + 10 KOH + 3 PbO2 → 2 K2CrO4 + 3 K2PbO2 + 8 H2O

Electrochemical

[edit]Although the formula of lead dioxide is nominally given as PbO2, the actual oxygen to lead ratio varies between 1.90 and 1.98 depending on the preparation method. Deficiency of oxygen (or excess of lead) results in the characteristic metallic conductivity of lead dioxide, with a resistivity as low as 10−4 Ω·cm and which is exploited in various electrochemical applications. Like metals, lead dioxide has a characteristic electrode potential, and in electrolytes it can be polarized both anodically and cathodically. Lead dioxide electrodes have a dual action, that is both the lead and oxygen ions take part in the electrochemical reactions.[8]

Production

[edit]Chemical processes

[edit]Lead dioxide is produced commercially by several methods, which include oxidation of red lead (Pb3O4) in alkaline slurry in a chlorine atmosphere,[6] reaction of lead(II) acetate with "chloride of lime" (calcium hypochlorite),[9][10] The reaction of Pb3O4 with nitric acid also affords the dioxide:[2][11]

- Pb3O4 + 4 HNO3 → PbO2 + 2 Pb(NO3)2 + 2 H2O

PbO2 reacts with sodium hydroxide to form the hexahydroxoplumbate(IV) ion [Pb(OH)6]2−, soluble in water.

Electrolysis

[edit]An alternative synthesis method is electrochemical: lead dioxide forms on pure lead, in dilute sulfuric acid, when polarized anodically at electrode potential about +1.5 V at room temperature. This procedure is used for large-scale industrial production of PbO2 anodes. Lead and copper electrodes are immersed in sulfuric acid flowing at a rate of 5–10 L/min. The electrodeposition is carried out galvanostatically, by applying a current of about 100 A/m2 for about 30 minutes.

The drawback of this method for the production of lead dioxide anodes is its softness, especially compared to the hard and brittle PbO2 which has a Mohs hardness of 5.5.[12] This mismatch in mechanical properties results in peeling of the coating which is preferred for bulk PbO2 production. Therefore, an alternative method is to use harder substrates, such as titanium, niobium, tantalum or graphite and deposit PbO2 onto them from lead(II) nitrate in static or flowing nitric acid. The substrate is usually sand-blasted before the deposition to remove surface oxide and contamination and to increase the surface roughness and adhesion of the coating.[13]

Applications

[edit]Lead dioxide is used in the production of matches, pyrotechnics, dyes and the curing of sulfide polymers. It is also used in the construction of high-voltage lightning arresters.[6]

Lead dioxide is used as an anode material in electrochemistry. β-PbO2 is more attractive for this purpose than the α form because it has relatively low resistivity, good corrosion resistance even in low-pH medium, and a high overvoltage for the evolution of oxygen in sulfuric- and nitric-acid-based electrolytes. Lead dioxide can also withstand chlorine evolution in hydrochloric acid. Lead dioxide anodes are inexpensive and were once used instead of conventional platinum and graphite electrodes for regenerating potassium dichromate. They were also applied as oxygen anodes for electroplating copper and zinc in sulfate baths. In organic synthesis, lead dioxide anodes were applied for the production of glyoxylic acid from oxalic acid in a sulfuric acid electrolyte.[13]

Lead acid battery

[edit]The most important use of lead dioxide is as the cathode of lead acid batteries. Its utility arises from the anomalous metallic conductivity of PbO2. The lead acid battery stores and releases energy by shifting the equilibrium (a comproportionation) between metallic lead, lead dioxide, and lead(II) salts in sulfuric acid.

- Pb + PbO2 + 2 HSO−4 + 2 H+ → 2 PbSO4 + 2 H2O E° = +2.05 V

Safety

[edit]Lead compounds are poisons. Chronic contact with the skin can potentially cause lead poisoning through absorption, or redness and irritation in the short term.[14]

PbO2 is not combustible, but it enhances flammability of other substances and the intensity of the fire. In case of a fire it gives off irritating and toxic fumes.[15][better source needed]

Lead dioxide is poisonous to aquatic life, but because of its insolubility it usually settles out of water.[16][15]

References

[edit]- ^ Meek, Terry L.; Garner, Leah D. (2005-02-01). "Electronegativity and the Bond Triangle". Journal of Chemical Education. 82 (2): 325. Bibcode:2005JChEd..82..325M. doi:10.1021/ed082p325. ISSN 0021-9584.

- ^ a b c Eagleson, Mary (1994). Concise Encyclopedia of Chemistry. Walter de Gruyter. p. 590. ISBN 978-3-11-011451-5.

- ^ Haidinger, W. (1845). "Zweite Klasse: Geogenide. II. Ordnung. Baryte VII. Bleibaryt. Plattnerit.". Handbuch der Bestimmenden Mineralogie (PDF) (in German). Vienna: Braumüller & Seidel. p. 500.

- ^ a b c Taggard, J. E. Jr.; et al. (1988). "Scrutinyite, natural occurrence of α-PbO2 from Bingham, New Mexico, U.S.A., and Mapimi, Mexico" (PDF). Canadian Mineralogist. 26: 905.

- ^ Harada, H.; Sasa, Y.; Uda, M. (1981). "Crystal data for β-PbO2" (PDF). Journal of Applied Crystallography. 14 (2): 141. doi:10.1107/S0021889881008959.

- ^ a b c d Greenwood, Norman N.; Earnshaw, Alan (1997). Chemistry of the Elements (2nd ed.). Butterworth-Heinemann. p. 386. doi:10.1016/C2009-0-30414-6. ISBN 978-0-08-037941-8.

- ^ Kumar De, Anil (2007). A Textbook of Inorganic Chemistry. New Age International. p. 387. ISBN 978-81-224-1384-7.

- ^ Barak, M. (1980). Electrochemical power sources: primary and secondary batteries. IET. pp. 184 ff. ISBN 978-0-906048-26-9.

- ^ M. Baulder (1963). "Lead(IV) Oxide". In G. Brauer (ed.). Handbook of Preparative Inorganic Chemistry, 2nd Ed. Vol. 1. NY, NY: Academic Press. p. 758.

- ^ Wiberg, Nils (2007). Lehrbuch der Anorganischen Chemie [Textbook of Inorganic chemistry] (in German). Berlin: de Gruyter. p. 919. ISBN 978-3-11-017770-1.

- ^ Sutcliffe, Arthur (1930). Practical Chemistry for Advanced Students (1949 ed.). London: John Murray.

- ^ "Plattnerite: Plattnerite mineral information and data". www.mindat.org. Retrieved 12 April 2018.

- ^ a b François Cardarelli (2008). Materials Handbook: A Concise Desktop Reference. Springer. p. 574. ISBN 978-1-84628-668-1.

- ^ "LEAD DIOXIDE". hazard.com. Archived from the original on 13 April 2021. Retrieved 12 April 2018.

- ^ a b PubChem. "Lead dioxide". pubchem.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov. Retrieved 2022-12-15.

- ^ "Product and Company Identification" (PDF). ltschem.com. Retrieved 29 February 2024.