Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

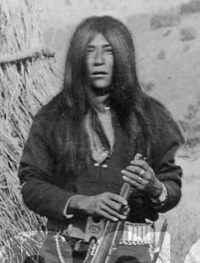

Massai

View on Wikipedia

Key Information

Massai (also known as: Masai, Massey, Massi, Mah–sii, Massa, Wasse, Wassil, Wild, Sand Coyote or by the nickname "Big Foot" Massai) was a member of the Mimbres/Mimbreños local group of the Chihenne band of the Chiricahua Apache. He was a warrior who was captured, but escaped from a train that was sending the scouts and renegades to Florida to be held with Geronimo and Chihuahua.

It is possible that Massai's true Apache name was Nogusea (meaning "crazy", according to Jason Betzinez and James Kaywaykla); he was enlisted as a member of Chatto's band as known as Ma-Che.[1]

Life

[edit]Born to White Cloud and Little Star at Mescal Mountain, Arizona, near Globe.[2][3] He later married a local Chiricahua and they had two children.[4]

Massai later met Geronimo, who was recruiting Apache to fight American settlers and soldiers. Massai and a Tonkawa named Gray Lizard agreed to join Geronimo, who instructed them to lay in supplies of arms, food, and ammunition.[5] Other sources state that Massai also served the United States government on two occasions, once in 1880 and the other in 1885, as an Apache Scout.[6] Upon traveling to meet Geronimo's forces, the two were informed that Geronimo had been arrested.[5] Both men were arrested by Chiricahua Apache Scouts and disarmed. Massai was placed onto a prison train as a prisoner of war along with Gray Lizard, who voluntarily agreed[7] to accompany Massai, together with the remaining Chiricahua Apache who had either been captured or had surrendered to the army. This included the Apache Scouts, who were now deemed expendable and undesirable.[5]

Massai and Gray Lizard later escaped from the prison train near Saint Louis, Missouri.[5] The two men walked some 1,200 miles back to the Mescalero Apache tribal area, crossing the Pecos River, and Capitan Gap. Near Sierra Blanca, New Mexico, the two men encountered a group of Mescalero Apache. Several days later, the two parted at Three Rivers, never to see each other again. Gray Lizard departed for Mescal Mountain and the San Carlos Indian Reservation near present-day Globe, Arizona, while Massai stayed on the run, raiding along what is today the New Mexico-Arizona border, and periodically taking refuge across the border in Mexico. His name appeared in San Carlos Agency reports from 1887 to 1890.[8] He later kidnapped and married (c. 1887) a Mescalero Apache girl named Zan-a-go-li-che and took her home to his family at Mescal Mountain. Massai and Zanagoliche had six children together.[9]

Massai was among those pursued during the April-June Apache Campaign of 1896, the final United States Army operation against the Chiricahua Apaches.

Demise

[edit]In 1959, historian Eve Ball of Ruidoso interviewed Alberta Begay, Massai’s last surviving child. Through this interview, Ball learned many previously unknown details about Massai’s life during his final years. These insights were published by Ball in her 1980 book, Indeh: An Apache Odyssey. As a token of gratitude, Alberta gave Ball Massai's belt buckle that was passed on to her by Zanagoliche, after she found it among his burned remains.

On 4 September 1906, Massai, a Chiricahua Apache warrior often confused with the infamous Apache Kid, was killed near Chloride, New Mexico. On September 4, rancher Charlie Anderson discovered that his home had been ransacked and his horses stolen. Believing that Apaches were responsible, Anderson approached his friend Walter Hearn for assistance. Together, they attempted to organize a posse to track the culprits.[10] However, many locals were unwilling to participate. Eventually, Anderson and Hearn recruited a group of men that included Bill Keene, Harry James, Mike Sullivan, Burt Slinkard, Charley Yaples, Ben Kemp, Ed and John James, Sebe Sorrells, Wesley Burris, and Anderson’s brother-in-law, Jim Hiller. After gathering supplies, such as cheese, crackers, and sardines, the posse began tracking the suspected raiders through the San Mateo Mountains. After several days, the posse discovered Anderson’s stolen horses near a recently abandoned campsite. Believing they were close to catching the raiders, they decided to stake out the area. At dawn, a man and a boy approached the campsite. Without warning, the posse opened fire, killing the man. The boy managed to escape. Initially, the posse believed they had killed a well-armed Apache renegade. However, a search of the camp revealed that the man was unarmed and had no ammunition for his rifle. Burt Slinkard, one of the posse members, later expressed regret for his role in the killing, stating that ambushing an unarmed man was against his principles.[11] Among the items recovered from the camp were Saunders’ gold watch and other goods believed to have been stolen during the recent raids. The aftermath of the ambush took a darker turn. Massai’s family, who were hiding nearby, heard the gunfire and saw the posse build an unusually large fire. After the posse left, Massai’s wife, Zanagoliche, and their children returned to the site and discovered Massai’s charred remains among the ashes, along with his belt buckle.[12] Reports soon surfaced that the posse had decapitated Massai’s body and taken his head as a trophy. Ben Kemp later claimed that Bill Keene was seen boiling the head on his property, and Ed James admitted to being involved in the decapitation. There are conflicting accounts about what happened to Massai’s severed head. Some sources suggest that it was taken as a trophy and eventually gifted to Yale University’s Skull and Bones society. However, these claims remain unverified. The Tucson Daily Citizen expressed skepticism, noting that similar stories had been told about the Apache Kid and other prominent Apache figures. The newspaper even joked that skulls attributed to the Apache Kid could be acquired in Arizona at “wholesale rates,” casting doubt on the authenticity of such relics.[13] Despite the controversy surrounding Massai’s death, the posse members reportedly agreed to a vow of secrecy. This decision was likely influenced by concerns over the legality of their actions and the mutilation of Massai’s body.[14] Some members, such as Slinkard, denied any involvement in the decapitation, while others, like Ed James, openly admitted to it.[15]

After Massai's death, Zanagoliche took her children, including Alberta Begay, to the Mescalero Reservation. There, Zanagoliche was reunited with family members she hadn't seen since her abduction. Sadly, within the first year of life on the reservation, three of Begay's siblings died from disease. Mrs. A. E. Thomas, a former teacher at the Mescalero Indian School, remarked, "The older children, accustomed to a free, animal-like existence, pined away and died." Begay’s brother, Clifford, was later murdered as a teenager. Alberta Begay spent her final years in a retirement home in Alamogordo, New Mexico.[16]

Another account states that Massai escaped over the border to Mexico, eventually settling in the Sierra Madre mountains with a group of rebellious Chiricahuas who had refused to surrender with Geronimo.

In popular culture

[edit]Massai was portrayed (in brownface) by Burt Lancaster in the 1954 film Apache.

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Alicia Delgadillo, Miriam Perrett, From Fort Marion to Fort Sill: A Documentary History of the Chiricahua Apache Prisoners of War, 1886–1913, University of Nebraska Press, ISBN 978-0803243798, 2013, pp. 178–179

- ^ Ball, Eve, Indeh, An Apache Odyssey, Norman OK: University of Oklahoma Press, ISBN 978-0-8061-2165-9 (1988), pp. 248–261

- ^ Begay, Alberta, Eve Ball, and Sherry Robinson, Apache Voices: Their Stories of Survival as Told to Eve Ball, Albuquerque, NM: University of New Mexico Press, ISBN 978-0826321633(2003), pp. 87–102

- ^ Begay, pp. 248–261

- ^ a b c d Ball, pp. 249–252

- ^ Begay, pp. 89–90

- ^ Begay, p. 90: As a Tonkawa, Gray Lizard was not compelled to join the Chiricahuan prisoners being deported.

- ^ Begay, p. 94

- ^ Begay, pp. 96–97

- ^ Hearn, Killing of the Apache Kid, p. 17

- ^ Lee, They Also Served, p. 53

- ^ Ball and Begay, Indeh, p. 258–259

- ^ “Apache Kid Killed Once More,” 1.

- ^ Leibson, “Rancher Reveals 40-Year Secret.”

- ^ "The Last Apache 'Broncho': The Apache Outlaw in the Popular Imagination, 1886-2013" (2014) by Leah Candolin

- ^ Robinson, Apache Voices, 100