Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Mobile, Alabama

View on Wikipedia

Mobile (/moʊˈbiːl/ moh-BEEL, French: [mɔbil] ⓘ) is a city and the county seat of Mobile County, Alabama, United States. The population was 187,041 at the 2020 census[7] and estimated at 204,689 following an annexation in 2023, making it the second-most populous city in Alabama. The Mobile metropolitan area, with an estimated 412,000 people, is the third-most populous metropolitan area in the state.[10]

Key Information

Alabama's only saltwater port, Mobile is located on the Mobile River at the head of Mobile Bay on the north-central Gulf Coast.[11] The Port of Mobile has always played a key role in the economic health of the city, beginning with the settlement as an important trading center between the French colonists and Native Americans, and now to its current role as the 12th-largest port in the United States.[12][13] During the American Civil War, the city surrendered to Federal forces on April 12, 1865,[14] after Union victories at two forts protecting the city.

Considered one of the Gulf Coast's cultural centers, Mobile has several art museums, a symphony orchestra, professional opera, professional ballet company, and a large concentration of historic architecture.[15][16] Mobile is known for having Mardi Gras, the oldest organized Carnival celebration in the United States. Alabama's French Creole population celebrated this festival from the first decade of the 18th century. Beginning in 1830, Mobile was home to the first organized Carnival mystic society to celebrate with a parade in the United States.[17]

History

[edit]Etymology

[edit]The city named after the Mobile tribe that the French colonists encountered living around Mobile Bay.[18] Although it is debated by Alabama historians, they may have been descendants of the Native American tribe from the small fortress town, Mabila, in central Alabama.[19] The Mobile tribe became allies with the French colonists and suggested the location for the original town of Mobile and a river fort.[20] The tribe's language was the basis for Mobilian Jargon, a Choctaw-derived lingua franca widely used to facilitate trade among the various Gulf Coast peoples.[21] About seven years after the founding of the French Mobile settlement, the Mobile tribe, along with the Tohomé, gained permission from the colonists to settle near the fort.[22]

Colonial

[edit]

In 1702, French colonists founded the Old Mobile Site south of existing Native American villages on the Mobile River. The Fort Louis de la Louisiane was built on a bluff that today is 27 miles (43 km) upriver from the Mobile River's mouth. The original town of Mobile was built on lower ground just downriver from the fort.[21] French Canadian brothers Pierre Le Moyne d'Iberville and Jean-Baptiste Le Moyne, Sieur de Bienville founded the site to establish control over France's claims to La Louisiane. From 1702 to 1711, it was the French colonial capital.[23] Mobile's Roman Catholic parish was established on July 20, 1703, by Jean-Baptiste de la Croix de Chevrières de Saint-Vallier, Bishop of Quebec, and was the first French Catholic parish established on the Gulf Coast.[24] In 1704, the ship Pélican delivered 23 Frenchwomen to the colony, but passengers had contracted yellow fever at a stop in Havana; though most recovered, many colonists and neighboring Native Americans contracted the disease and died. African slaves were transported to Mobile on a supply ship from the French colony of Saint-Domingue in the Caribbean.[25]

Disease and flooding plagued French colonists at the Old Mobile Site.[26] The colony grew to 279 persons by 1708 but shrank to 178 persons two years later.[24] Bienville ordered the settlement to relocate downriver and Mobile moved to its present location at the confluence of the Mobile River and Mobile Bay in 1711.[26] According to anthropologist Greg Waselkov, French colonists burned the Old Mobile Site to the ground, likely to prevent their enemies from occupying it.[27] An earth-and-palisade Fort Louis was constructed at the new site.[28] The capital of La Louisiane was moved in 1720 to Biloxi,[28] and Mobile became a regional military and trading center. In 1723 the construction of a new brick fort with a stone foundation began[28] and it was renamed Fort Condé in honor of Louis Henri, Duke of Bourbon.[29]

In 1763, Britain defeated France in the Seven Years' War. The Treaty of Paris ceded French territories east of the Mississippi River to Britain, including Mobile. The city became part of the expanded British West Florida colony.[30] The British changed the name of Fort Condé to Fort Charlotte, after Queen Charlotte.[31]

The British promised religious tolerance to the French colonists, and 112 French colonists remained in Mobile.[32] The first permanent Jewish settlers came to Mobile in 1763 as a result of the new British rule and religious tolerance; Jews were not allowed to officially reside in colonial French Louisiana due to the Code Noir. Most colonial-era Jews in Mobile were merchants and traders from Sephardic Jewish communities in Savannah, Georgia and Charleston, South Carolina.[33] By 1766, the town's population was estimated to be 860 people, although the borders were smaller than during the French colonial period.[32] During the American Revolutionary War, West Florida and Mobile became a refuge for loyalists fleeing the other colonies.[34]

While the British were fighting rebellious colonists along the Atlantic coast, the Spanish entered the war in 1779.[35] The Spanish wished to eliminate any British threat to their Louisiana colony west of the Mississippi River, which they had received from France in the 1763 Treaty of Paris.[34] Bernardo de Galvez, the Spanish Governor of Louisiana,[35] captured Mobile during the Battle of Fort Charlotte in 1780. Their actions were condoned by the revolting American colonies, partially evidenced by the presence of Oliver Pollack, representative of the American Continental Congress. Due to strong trade ties, many residents of Mobile and West Florida remained loyal to the British Crown.[34][35] The Spanish renamed the fort as Fortaleza Carlota, and held Mobile as a part of Spanish West Florida until 1813, when it was seized by United States General James Wilkinson during the War of 1812.[36]

19th century

[edit]

When Mobile was included in the Mississippi Territory in 1813, the population had dwindled to roughly 300 people. The territory was split in 1817, and the eastern half, including the Mobile Bay area, became the Alabama Territory for two years before being admitted to the union as the state of Alabama. Mobile's population had increased to 809 by that time.[37] Mobile was well situated for trade, as its location tied it to a river system that served as the principal navigational access for most of Alabama and a large part of Mississippi. River transportation was aided by the introduction of steamboats in the early decades of the 19th century.[38] By 1822, the city's population had risen to 2,800.[37]

The Industrial Revolution in Great Britain created shortages of cotton, increasing prices on world markets.[39] Much land well suited to growing cotton lies in the vicinity of the Mobile River, and its main tributaries the Tombigbee and Alabama Rivers. A plantation economy using slave labor developed in the region and Mobile's population quickly grew.[37] From the 1830s onward, Mobile expanded into a city of commerce focused on the cotton and slave trades. Slaves were transported by ship in the coastwise slave trade from the Upper South. Many businesses in the city were related to the slave trade, and the city's booming businesses attracted merchants from the North; by 1850 10% of its population was from New York City, which was deeply involved in the cotton industry.[40]

Mobile was the slave-trading center of the state until the 1850s, when it was surpassed by Montgomery.[41] The prosperity stimulated a building boom that was underway by the mid-1830s. This was cut short in part by the Panic of 1837 and yellow fever epidemics.[42] The waterfront was developed with wharves, terminal facilities, and fireproof brick warehouses. The exports of cotton grew in proportion to the amounts being produced in the Black Belt; by 1840 Mobile was second only to New Orleans in cotton exports in the nation.[37] Mobile slaveholders owned relatively few slaves compared to planters in the upland plantation areas, but many households had domestic slaves, and many other slaves worked on the waterfront and on riverboats. The last slaves to enter the United States from the African trade were brought to Mobile on the slave ship Clotilda, including Cudjoe Lewis, who was the last survivor of the slave trade.[43]

By 1860 Mobile's population within the city limits had reached 29,258 people; it was the 27th-largest city in the United States and 4th-largest in what would soon be the Confederate States of America.[44] The free population in the whole of Mobile County, including the city, consisted of 29,754 citizens, of which 1,195 were free people of color.[45] Additionally, 1,785 slave owners in the county held 11,376 people in bondage, about one-quarter of the total county population of 41,130 people.[45]

During the American Civil War, Mobile was a Confederate city. The H. L. Hunley, the first submarine to sink an enemy ship, was built in Mobile.[46] One of the most famous naval engagements of the war was the Battle of Mobile Bay, resulting in the Union taking control of Mobile Bay on August 5, 1864.[47] On April 12, 1865, three days after Robert E. Lee's surrender at Appomattox Courthouse, the city surrendered to the Union army to avoid destruction after Union victories at nearby Spanish Fort and Fort Blakeley.[47]

On May 25, 1865, the city suffered great loss when some three hundred people died as a result of an explosion at a federal ammunition depot on Beauregard Street. The explosion left a 30-foot (9 m) deep hole at the depot's location, and sank ships docked on the Mobile River; the resulting fires destroyed the northern portion of the city.[48]

Federal Reconstruction in Mobile began after the Civil War and effectively ended in 1874 when the local Democrats gained control of the city government.[49] The last quarter of the 19th century was a time of economic depression and municipal insolvency for Mobile. One example can be provided by the value of Mobile's exports during this period of depression. The value of exports leaving the city fell from $9 million in 1878 to $3 million in 1882.[50]

20th century before WWII

[edit]

The turn of the 20th century brought the Progressive Era to Mobile. The economic structure developed with new industries, generating new jobs and attracting a significant increase in population.[51] The population increased from around 40,000 in 1900 to 60,000 by 1920.[51] During this time the city received $3 million in federal grants for harbor improvements to deepen the shipping channels.[51] During and after World War I, manufacturing became increasingly vital to Mobile's economic health, with shipbuilding and steel production being two of the most important industries.[51]

During this time, social justice and race relations in Mobile worsened.[51] The state passed a new constitution in 1901 that disenfranchised most blacks and many poor whites; and the white Democratic-dominated legislature passed other discriminatory legislation. In 1902, the city government passed Mobile's first racial segregation ordinance, segregating the city streetcars. It legislated what had been informal practice, enforced by convention.[51] Mobile's African-American population responded to this with a two-month boycott, but the law was not repealed.[51] After this, Mobile's de facto segregation was increasingly replaced with legislated segregation as whites imposed Jim Crow laws to maintain supremacy.[51]

In 1911 the city adopted a commission form of government, which had three members elected by at-large voting. Considered to be progressive, as it would reduce the power of ward bosses, this change resulted in the elite white majority strengthening its power, as only the majority could gain election of at-large candidates. In addition, poor whites and blacks had already been disenfranchised. Mobile was one of the last cities to retain this form of government, which prevented smaller groups from electing candidates of their choice. But Alabama's white yeomanry had historically favored single-member districts in order to elect candidates of their choice.[52]

The red imported fire ant was first introduced into the United States via the Port of Mobile. Sometime in the late 1930s they came ashore off cargo ships arriving from South America. The ants were carried in the soil used as ballast on those ships.[53] They have spread throughout the South and Southwest.[54]

During World War II, the defense buildup in Mobile shipyards resulted in a considerable increase in the city's white middle-class and working-class population, largely due to the massive influx of workers coming to work in the shipyards and at Brookley Army Air Field.[55] Between 1940 and 1943, more than 89,000 people moved into Mobile to work for war effort industries.[55]

Mobile was one of eighteen United States cities producing Liberty ships. Its Alabama Drydock and Shipbuilding Company (ADDSCO) supported the war effort by producing ships faster than the Axis powers could sink them. ADDSCO also churned out a copious number of T2 tankers for the War Department.[55] Gulf Shipbuilding Corporation, a subsidiary of Waterman Steamship Corporation, focused on building freighters, Fletcher-class destroyers, and minesweepers.[55] The rapid increase of population in the city produced crowded conditions, increasing social tensions in the competition for housing and good jobs.[56]

In May 1943, a race riot broke out between whites and blacks. ADDSCO management had long maintained segregated conditions at the shipyards, although the Roosevelt administration had ordered defense contractors to integrate facilities. That year ADDSCO promoted 12 blacks to positions as welders, previously reserved for whites; and whites objected to the change by rioting on May 24. The mayor appealed to the governor to call in the National Guard to restore order, but it was weeks before officials allowed African Americans to return to work.[57]

Post-WWII

[edit]In the late 1940s, the transition to the postwar economy was hard for the city, as thousands of jobs were lost at the shipyards with the decline in the defense industry. Eventually the city's social structure began to become more liberal. Replacing shipbuilding as a primary economic force, the paper and chemical industries began to expand. No longer needed for defense, most of the old military bases were converted to civilian uses. Following the war, in which many African Americans had served, veterans and their supporters stepped up activism to gain enforcement of their constitutional rights and social justice, especially in the Jim Crow South. During the 1950s the City of Mobile integrated its police force and Spring Hill College accepted students of all races. Unlike in the rest of the state, by the early 1960s the city buses and lunch counters voluntarily desegregated.[55]

The Alabama legislature passed the Cater Act in 1949, allowing cities and counties to set up industrial development boards (IDB) to issue municipal bonds as incentives to attract new industry into their local areas. The city of Mobile did not establish a Cater Act board until 1962. George E. McNally, Mobile's first Republican mayor since Reconstruction, was the driving force behind the founding of the IDB. The Mobile Area Chamber of Commerce, believing its members were better qualified to attract new businesses and industry to the area, considered the new IDB as a serious rival. After several years of political squabbling, the Chamber of Commerce emerged victorious. While McNally's IDB prompted the Chamber of Commerce to become more proactive in attracting new industry, the chamber effectively shut Mobile city government out of economic development decisions.[58]

In 1963, three African-American students brought a case against the Mobile County School Board for being denied admission to Murphy High School.[59] This was nearly a decade after the United States Supreme Court had ruled in Brown v. Board of Education (1954) that segregation of public schools was unconstitutional. The federal district court ordered that the three students be admitted to Murphy for the 1964 school year, leading to the desegregation of Mobile County's school system.[59]

The civil rights movement gained congressional passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and Voting Rights Act of 1965, which increased the percentage of black residents able to vote,[60] ended multiple forms of segregation, and allowed the NAACP to return to Mobile.[61] However, the city's commission form of government with at-large voting resulted in all positions being elected by the white majority, as African Americans could not command a majority for their candidates in the informally segregated city.[62] Many forms of de facto segregation persisted for decades.[63]

In 1969, the Department of Defense closed Brookley Air Force Base, dealing a blow to Mobile's economy. It affected about 10% of workers in the city.[64] In total, 16,000 people lost their jobs.[65]

Mobile's city commission form of government was challenged and finally overturned in 1982 in City of Mobile v. Bolden, which was remanded by the United States Supreme Court to the district court. Finding that the city had adopted a commission form of government in 1911 and at-large positions with discriminatory intent, the court proposed that the three members of the city commission should be elected from single-member districts, likely ending their division of executive functions among them. Mobile's state legislative delegation in 1985 finally enacted a mayor-council form of government, with seven members elected from single-member districts. This was approved by voters.[52] As white conservatives increasingly entered the Republican Party in the late 20th century, African-American residents of the city have elected members of the Democratic Party as their candidates of choice. Since the change to single-member districts, more women and African Americans were elected to the council than under the at-large system.[52]

Beginning in the late 1980s, newly elected mayor Mike Dow and the city council began an effort termed the "String of Pearls Initiative" to make Mobile into a competitive city.[66] The city initiated construction of numerous new facilities and projects, and the restoration of hundreds of historic downtown buildings and homes.[66] City and county leaders also made efforts to attract new business ventures to the area.[67]

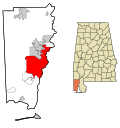

Geography

[edit]Mobile is located in the southwestern region of the U.S. state of Alabama.[68]

According to the United States Census Bureau, the city has a total area of 180.07 square miles (466.4 km2), with 139.48 square miles (361.3 km2) of it being land, and 40.59 square miles (105.1 km2), or 22.5% of the total, being covered by water.[4] The elevation in Mobile ranges from 10 feet (3 m) on Water Street in downtown[6] to 211 feet (64 m) at the Mobile Regional Airport.[69]

Neighborhoods

[edit]

Mobile has a number of notable historic neighborhoods. These include Ashland Place, Campground, Church Street East, De Tonti Square, Leinkauf, Lower Dauphin Street, Midtown, Oakleigh Garden, Old Dauphin Way, Spring Hill, and Toulminville.[70][71][72]

Climate

[edit]

Mobile's geographical location on the Gulf of Mexico provides a mild subtropical climate (Köppen Cfa), with hot, humid summers and mild, rainy winters. The record low temperature was −1 °F (−18 °C), which was set on February 13, 1899.[73] The record high temperature is 106 °F (41 °C), which was set on 26 August 2023.[74]

A 2007 study determined that Mobile is the wettest city in the contiguous 48 states, with 66.3 inches (1,680 mm) of average annual rainfall over a 30-year period.[75] Mobile averages 120 days per year with at least 0.01 inches (0.3 mm) of rain. Precipitation is heavy year-round. On average, July and August are the wettest months, with frequent and often-heavy shower and thunderstorm activity. October is slightly drier than other months. Snow is rare in Mobile. From 1996 to 2017, the city did not see snowfall.[76] The most recent snowfall event occurred January 21, 2025, which produced record-breaking accumulations of up to 8.5 inches within the city and near-blizzard conditions.[77][78] The snowfall event previous to this one was on December 8, 2017.[79]

Mobile has been affected by major tropical storms and hurricanes.[16] The city suffered a major natural disaster on the night of September 12, 1979, when Category-3 Hurricane Frederic passed over the heart of the city. The storm caused tremendous damage to Mobile and the surrounding area.[80] Mobile had moderate damage from Hurricane Opal on October 4, 1995, and Hurricane Ivan on September 16, 2004.[81]

Mobile suffered millions of dollars in damage from Hurricane Katrina on August 29, 2005, which damaged many Gulf Coast cities. A storm surge of 11.45 feet (3.49 m), topped by higher waves, damaged eastern sections of the city with extensive flooding in downtown, the Battleship Parkway, and the elevated Jubilee Parkway.[82]

In 2020, on the 16th anniversary of Ivan, Hurricane Sally became the first Hurricane since Ivan to directly hit Alabama. Although a Category-2, Sally moved slowly through Alabama causing significant damage in its path. While the area was still recovering from Sally, a month later Hurricane Zeta struck the area as a Category-3.[83]

| Climate data for Mobile, Alabama (Mobile Regional Airport, 1991–2020 normals,[b] extremes 1872–present) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °F (°C) | 84 (29) |

85 (29) |

91 (33) |

94 (34) |

100 (38) |

103 (39) |

104 (40) |

105 (41) |

103 (39) |

98 (37) |

88 (31) |

85 (29) |

105 (41) |

| Mean maximum °F (°C) | 75.7 (24.3) |

77.6 (25.3) |

83.0 (28.3) |

86.3 (30.2) |

92.2 (33.4) |

95.4 (35.2) |

96.7 (35.9) |

96.2 (35.7) |

93.8 (34.3) |

89.1 (31.7) |

82.0 (27.8) |

77.6 (25.3) |

97.8 (36.6) |

| Mean daily maximum °F (°C) | 61.5 (16.4) |

65.6 (18.7) |

71.8 (22.1) |

77.8 (25.4) |

84.9 (29.4) |

89.4 (31.9) |

90.9 (32.7) |

90.8 (32.7) |

87.5 (30.8) |

79.7 (26.5) |

70.2 (21.2) |

63.5 (17.5) |

77.8 (25.4) |

| Daily mean °F (°C) | 51.1 (10.6) |

55.0 (12.8) |

60.9 (16.1) |

66.9 (19.4) |

74.4 (23.6) |

80.1 (26.7) |

82.0 (27.8) |

81.9 (27.7) |

78.1 (25.6) |

69.0 (20.6) |

58.9 (14.9) |

53.3 (11.8) |

67.6 (19.8) |

| Mean daily minimum °F (°C) | 40.7 (4.8) |

44.4 (6.9) |

50.0 (10.0) |

56.0 (13.3) |

63.8 (17.7) |

70.8 (21.6) |

73.1 (22.8) |

72.9 (22.7) |

68.8 (20.4) |

58.2 (14.6) |

47.7 (8.7) |

43.0 (6.1) |

57.4 (14.1) |

| Mean minimum °F (°C) | 22.7 (−5.2) |

26.9 (−2.8) |

31.9 (−0.1) |

40.0 (4.4) |

50.0 (10.0) |

63.2 (17.3) |

68.6 (20.3) |

67.3 (19.6) |

56.8 (13.8) |

40.5 (4.7) |

30.8 (−0.7) |

27.3 (−2.6) |

21.0 (−6.1) |

| Record low °F (°C) | 3 (−16) |

−1 (−18) |

21 (−6) |

32 (0) |

43 (6) |

49 (9) |

62 (17) |

57 (14) |

42 (6) |

30 (−1) |

22 (−6) |

8 (−13) |

−1 (−18) |

| Average precipitation inches (mm) | 5.66 (144) |

4.47 (114) |

5.44 (138) |

5.71 (145) |

5.39 (137) |

6.55 (166) |

7.69 (195) |

6.87 (174) |

5.30 (135) |

3.95 (100) |

4.60 (117) |

5.45 (138) |

67.08 (1,704) |

| Average snowfall inches (cm) | 0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.1 (0.25) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.1 (0.25) |

0.2 (0.51) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 0.01 in) | 9.9 | 9.2 | 8.7 | 7.6 | 8.0 | 12.4 | 14.9 | 13.2 | 9.2 | 6.9 | 7.7 | 9.4 | 117.1 |

| Average snowy days (≥ 0.1 in) | 0.1 | 0.0 | 0.1 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.1 | 0.3 |

| Average relative humidity (%) | 74 | 72 | 72 | 71 | 74 | 76 | 78 | 78 | 77 | 73 | 75 | 75 | 75 |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 158 | 155 | 211 | 255 | 300 | 287 | 246 | 254 | 233 | 254 | 193 | 145 | 2,691 |

| Source 1: NOAA (humidity 1981–2010)[84][85][86][87] | |||||||||||||

| Source 2: Danish Meteorological Institute (sun, 1931–1960)[88] | |||||||||||||

| Climate data for Mobile, Alabama (Mobile Downtown Airport), 1991–2020 normals, extremes 1948–present | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °F (°C) | 81 (27) |

86 (30) |

87 (31) |

90 (32) |

99 (37) |

102 (39) |

102 (39) |

102 (39) |

101 (38) |

98 (37) |

89 (32) |

82 (28) |

102 (39) |

| Mean maximum °F (°C) | 74.5 (23.6) |

76.8 (24.9) |

81.5 (27.5) |

85.1 (29.5) |

92.2 (33.4) |

95.2 (35.1) |

96.7 (35.9) |

96.2 (35.7) |

94.2 (34.6) |

89.1 (31.7) |

82.4 (28.0) |

76.7 (24.8) |

97.8 (36.6) |

| Mean daily maximum °F (°C) | 62.1 (16.7) |

65.8 (18.8) |

71.8 (22.1) |

77.9 (25.5) |

85.0 (29.4) |

90.0 (32.2) |

91.7 (33.2) |

91.9 (33.3) |

88.8 (31.6) |

81.3 (27.4) |

71.6 (22.0) |

64.3 (17.9) |

78.5 (25.8) |

| Daily mean °F (°C) | 52.3 (11.3) |

55.9 (13.3) |

61.8 (16.6) |

68.3 (20.2) |

75.7 (24.3) |

81.5 (27.5) |

83.5 (28.6) |

83.6 (28.7) |

80.3 (26.8) |

71.1 (21.7) |

60.8 (16.0) |

54.6 (12.6) |

69.1 (20.6) |

| Mean daily minimum °F (°C) | 42.5 (5.8) |

46.1 (7.8) |

51.8 (11.0) |

58.6 (14.8) |

66.3 (19.1) |

73.1 (22.8) |

75.3 (24.1) |

75.3 (24.1) |

71.8 (22.1) |

61.0 (16.1) |

49.9 (9.9) |

44.9 (7.2) |

59.7 (15.4) |

| Mean minimum °F (°C) | 24.0 (−4.4) |

29.5 (−1.4) |

34.1 (1.2) |

42.5 (5.8) |

51.7 (10.9) |

65.6 (18.7) |

69.9 (21.1) |

68.5 (20.3) |

59.1 (15.1) |

43.3 (6.3) |

32.7 (0.4) |

28.6 (−1.9) |

22.9 (−5.1) |

| Record low °F (°C) | 8 (−13) |

13 (−11) |

23 (−5) |

36 (2) |

43 (6) |

55 (13) |

63 (17) |

60 (16) |

48 (9) |

34 (1) |

24 (−4) |

12 (−11) |

8 (−13) |

| Average precipitation inches (mm) | 5.19 (132) |

3.77 (96) |

5.11 (130) |

4.86 (123) |

4.42 (112) |

5.78 (147) |

6.57 (167) |

7.14 (181) |

4.47 (114) |

3.80 (97) |

4.13 (105) |

5.28 (134) |

60.52 (1,537) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 0.01 in) | 11.3 | 11.5 | 11.4 | 9.1 | 8.5 | 12.7 | 14.4 | 14.0 | 8.9 | 9.2 | 10.4 | 12.0 | 133.4 |

| Source: NOAA[84][89] | |||||||||||||

Christmas Day tornado

[edit]

In December 2012, the city suffered two major tornadoes. One touched down on December 20, and the other five days later.[90] On December 20, an EF1 tornado touched down near Davidson High School and took a path ending in Prichard.[91] On December 25, 2012, at 4:54 pm, a large wedge tornado touched down.[90] It rapidly intensified as it moved north-northeast at speeds of up to 50 mph (80 km/h), causing damage or destruction to at least 100 structures in Midtown. The heaviest damage to houses was along Carlen Street, Rickarby Place, Dauphin Street, Old Shell Road, Margaret Street, Silverwood Street, and Springhill Avenue.[90] The second tornado was classified as an EF2 tornado by the National Weather Service on December 26.[90] As a result of the significant damage from the tornado, Murphy High School students were transferred to nearby Clark-Shaw Magnet School to finish out the school year as repairs were being made to Murphy High. This increased the student body at the Clark-Shaw campus from 700 students to almost 3,000 students.[92]

Demographics

[edit]| Year | Pop. | ±% |

|---|---|---|

| 1785 | 746 | — |

| 1788 | 1,468 | +96.8% |

| 1820 | 1,500 | +2.2% |

| 1830 | 3,194 | +112.9% |

| 1840 | 12,672 | +296.7% |

| 1850 | 20,515 | +61.9% |

| 1860 | 29,258 | +42.6% |

| 1870 | 32,034 | +9.5% |

| 1880 | 29,132 | −9.1% |

| 1890 | 31,076 | +6.7% |

| 1900 | 38,469 | +23.8% |

| 1910 | 51,521 | +33.9% |

| 1920 | 60,777 | +18.0% |

| 1930 | 68,202 | +12.2% |

| 1940 | 78,720 | +15.4% |

| 1950 | 129,009 | +63.9% |

| 1960 | 202,779 | +57.2% |

| 1970 | 190,026 | −6.3% |

| 1980 | 200,452 | +5.5% |

| 1990 | 196,278 | −2.1% |

| 2000 | 198,915 | +1.3% |

| 2010 | 195,111 | −1.9% |

| 2020 | 187,041 | −4.1% |

| 2022 (est.) | 183,289 | −2.0% |

| U.S. Decennial Census[93][94][95] 2020 Census[7] 2022 Estimate[8] | ||

As of the 2020 census, there were 187,041 people, 77,772 households, and 45,953 families residing in the city.[96] The population density was 1,341.0 inhabitants per square mile (517.8/km2).[97] There were 89,215 housing units. The racial makeup of the city was 40.12% White, 51.06% Black or African American, 0.27% Native American, 1.80% Asian, 0.06% Pacific Islander, and 3.13% from two or more races. Hispanic or Latino people of any race were 3.23% of the population.[98] After annexing areas west of the city in July 2023, Mobile's population increased to 204,689 residents, making it the second-most populous city in Alabama with only Huntsville having a larger population.[99] The annexation shifted racial demographics; Mobile became a majority-minority city with Black or African American residents remaining the largest racial group.[100]

According to American Values Atlas data published in 2014, the majority of the population were Christians, with 36% identifying as white evangelical Protestant, 18% identifying as black Protestant, 13% as mainline Protestant, and 7% as Catholic. 14% of the population identified as unaffiliated with any religion.[101] According to the 2024 American Community Survey estimates, 19.7% of the population was under 18. The median age was 38.6. The average family size was 3.13 people. The median household income in Mobile was $50,156, while the median income for a family was $73,717. 15.2% of the population were living below the poverty line.[102]

| Race / Ethnicity (NH = Non-Hispanic) | Pop 2000[103] | Pop 2010[104] | Pop 2020[105] | % 2000 | % 2010 | 2020 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| White alone (NH) | 98,965 | 85,613 | 75,043 | 49.75% | 43.88% | 40.12% |

| Black or African American alone (NH) | 91,660 | 98,202 | 95,505 | 46.08% | 50.33% | 51.06% |

| Native American or Alaska Native alone (NH) | 463 | 572 | 513 | 0.23% | 0.29% | 0.27% |

| Asian alone (NH) | 3,011 | 3,409 | 3,369 | 1.51% | 1.75% | 1.80% |

| Native Hawaiian or Pacific Islander alone (NH) | 41 | 57 | 106 | 0.02% | 0.03% | 0.06% |

| Other race alone (NH) | 193 | 219 | 622 | 0.10% | 0.11% | 0.33% |

| Mixed race or Multiracial (NH) | 1,754 | 2,439 | 5,849 | 0.88% | 1.25% | 3.13% |

| Hispanic or Latino (any race) | 2,828 | 4,600 | 6,034 | 1.42% | 2.36% | 3.23% |

| Total | 198,915 | 195,111 | 187,041 | 100.00% | 100.00% | 100.00% |

Economy

[edit]

Aerospace, steel, ship building, retail, services, construction, medicine, and manufacturing are Mobile's major industries. After several decades of economic decline, Mobile's economy began to rebound in the late 1980s. Between 1993 and 2003 roughly 13,983 new jobs were created as 87 new companies were founded and 399 existing companies were expanded.[106]

Defunct companies that had been founded or based in Mobile included Alabama Drydock and Shipbuilding Company, Delchamps, and Gayfers.[107][108][109] Current companies that were formerly based in the city include Checkers, Minolta-QMS, Morrison's, and the Waterman Steamship Corporation.[110][111] In addition to those discussed below, AlwaysHD, Foosackly's, Integrity Media, and Volkert, Inc. are headquartered in Mobile.[112][113][114][115]

Major industry

[edit]

Port of Mobile and shipyards

[edit]In 2005, Mobile's Alabama State Docks completed the largest expansion in its history, increasing its container processing and storage facility, and its container storage at the docks by over 1,000% at a cost of over $300 million.[116] Despite the expansion and addition of two massive new cranes, the port went from 9th largest to the 12th largest by tonnage in the nation from 2008 to 2010.[13][117]

Shipbuilding increased substantially in 1999 with the founding of Austal USA,[118] expanding its production facility for United States defense and commercial aluminum shipbuilding on Blakeley Island in 2005.[119] Atlantic Marine operated a major shipyard at the former Alabama Drydock and Shipbuilding Company site on Pinto Island. It was acquired by British defense conglomerate BAE Systems in May 2010 and renamed BAE Systems Southeast Shipyards. The company operates the site as a full-service shipyard, employing approximately 600 workers.[107][120][121]

Mobile Aeroplex at Brookley

[edit]The Mobile Aeroplex at Brookley is an industrial complex and airport located 3 miles (5 km) south of the central business district of the city. It is the largest industrial and transportation complex in the region with more than 70 companies, many of which are aerospace, spread over 1,650 acres (668 ha).[122] Notable employers at Brookley include Airbus North America Engineering (Airbus Military North America's facilities are at the Mobile Regional Airport), VT Mobile Aerospace Engineering (a division of ST Engineering), and Continental Motors.[123]

An Airbus A320 family aircraft assembly plant, their first in the United States, was opened in Mobile in 2015 for the assembly of the A319, A320 and A321 aircraft. In 2017 it produced up to 50 aircraft per year.[124][125][126] In August 2019, the assembly plant began production on the Airbus A220 model.[127][128]

Top employers

[edit]

According to the City's 2024 Comprehensive Annual Financial Report, the largest employers in the city are:[129]

| # | Employer | # of Employees | Percentage |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | University of South Alabama | 11,500 | 6.02% |

| 2 | Mobile County Public School System | 7,200 | 3.77% |

| 3 | Infirmary Health Systems | 4,700 | 2.46% |

| 4 | Austal USA | 3,000 | 1.57% |

| 5 | Airbus U.S. Manufacturing | 2,000 | 1.05% |

| 6 | City of Mobile | 2,000 | 1.05% |

| 7 | AltaPointe | 1,700 | 0.89% |

| 8 | AM/NS Calvert | 1,600 | 0.84% |

| 9 | Springhill Medical Center | 1,600 | 0.84% |

| 10 | County of Mobile | 1,600 | 0.84% |

| — | Total | 36,900 | 19.33% |

Unemployment rate

[edit]The United States Department of Labor's Bureau of Labor Statistics unemployment rate (not seasonally adjusted).[130][131]

| Mobile | Mobile County |

Mobile Metropolitan Statistical Area |

Alabama | United States | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Jan. 2025 | 4.2 | 4.2 | 4.2 | 3.3 | 4.0 |

| Feb. 2025 | 4.2 | 4.2 | 4.2 | 3.3 | 4.1 |

| March 2025 | 4.1 | 4.1 | 4.2 | 3.3 | 4.2 |

| April 2025 | 3.4 | 3.4 | 3.4 | 3.3 | 4.2 |

| May 2025 | 3.7 | 3.3 | 3.3 | 3.3 | 4.2 |

| June 2025 | 4.0 | 3.7 | 3.7 | 3.2 | 4.1 |

| July 2025 | 3.7 | 3.4 | 3.4 | 3.0 | 4.2 |

Arts and culture

[edit]

Unlike other Alabama cities, Mobile's French and Spanish colonial history has given it a culture distinguished by French, Spanish, Creole, African, and Catholic heritage, in addition to later British and American influences. The annual Carnival celebration, Mardi Gras, is an example of its differences. Mobile has the longest history of celebrating Mardi Gras in the United States, dating to the early 18th century during the French colonial period.[132] Carnival in Mobile evolved over 300 years from a sedate French Catholic tradition to a mainstream multi-week celebration.[133] Mobile's official cultural ambassadors are the Azalea Trail Maids, meant to embody the ideals of Southern hospitality.[134]

Carnival and Mardi Gras

[edit]

The Carnival season has expanded throughout the late fall and winter: balls in the city may be scheduled as early as November, with the parades beginning after January 5 and the Twelfth Day of Christmas or Epiphany on January 6.[135][136] Carnival celebrations end at midnight on Mardi Gras, which falls on the Tuesday before Ash Wednesday.[137] During the Carnival season, mystic societies build floats, parade through downtown, and toss small gifts to spectators.[138] They also hold formal masquerade balls, usually by invitation only.[136]

Carnival was first celebrated in Mobile in 1703 when colonial French Catholic settlers carried out their traditional celebration at the Old Mobile Site.[17] Mobile's first Carnival society was established in 1711 with the Boeuf Gras Society (Fatted Ox Society).[139] In 1830 Mobile's Cowbellion de Rakin Society was the first formally organized and masked mystic society in the United States to celebrate with a parade.[17][137] The Cowbellions began their parade with rakes, hoes, and cowbells.[137] They introduced horse-drawn floats in 1840. The Striker's Independent Society, formed in 1843, is the oldest surviving mystic society in the United States.[139] Carnival celebrations were canceled during the American Civil War.[140]

Mardi Gras parades were revived by Joe Cain in the 1860s. He paraded as a fictional "undefeated Chickasaw chief" supported by a band of "Lost Cause Minstrels" in defiance of Union-led Reconstruction.[141] Founded in 2004, the Conde Explorers in 2005 were the first integrated Mardi Gras society to parade in downtown Mobile. The Explorers were featured in the documentary, The Order of Myths (2008), by Margaret Brown about Mobile's Mardi Gras.[142][143]

Archives and libraries

[edit]

The National African American Archives and Museum features the history of African-American participation in Mardi Gras, slavery-era artifacts, and portraits and biographies of famous African Americans.[144] The Doy Leale McCall Rare Book and Manuscript Library at the University of South Alabama are open to the public and house primary sources relating to the history of the university, Mobile, and southern Alabama.[145][146] The Mobile Municipal Archives contains the extant city records, dating from the Mississippi Territory period.[147] The Mobile Genealogical Society Library and Media Center features handwritten manuscripts and published materials that are available for use in genealogical research.[148]

The Mobile Public Library system serves Mobile and consists of eight branches across Mobile County. Its local history and genealogy division is located near the Ben May Main Library on Government Street.[149] The Saint Ignatius Archives, Museum and Theological Research Library contains primary sources, artifacts, documents, photographs and publications that pertain to the history of Saint Ignatius Church and School, the Catholic history of the city, and the history of the Roman Catholic Church.[150]

Arts and entertainment

[edit]

The Mobile Museum of Art features permanent exhibits that span several centuries of art and culture. The museum was expanded in 2002 to approximately 95,000 square feet (8,826 m2).[151] The Centre for the Living Arts is an organization that operates the historic Saenger Theatre and Space 301, a contemporary art gallery. The Saenger Theatre opened in 1927 as a movie palace. Today it is a performing arts center, a small concert venue, and home to the Mobile Symphony Orchestra.[152] The Crescent Theater in downtown Mobile has shown arthouse films since 2008.[153]

The Mobile Civic Center contains three facilities under one roof. The 400,000 sq ft (37,161 m2) building has an arena, a theater, and an exposition hall. It is the primary concert venue for the city and home to the Mobile Opera and Mobile Ballet.[16] A variety of events are held at the Arthur C. Outlaw Convention Center.[154]

The city has hosted the Greater Gulf State Fair, each October since 1955.[155] The city hosted BayFest, an annual three-day music festival, from 1995–2015.[156] Mobile also holds the Ten Sixty Five free music festival.[157]

The Mobile Chamber Music hosts various chamber musicians at the Laidlaw Performing Arts Center on the campus of the University of South Alabama and the Central Presbyterian Church.[158][159]

The Mobile Theatre Guild is a nonprofit community theatre that has served the city since 1947. It is a member of the Mobile Arts Council,[160] an umbrella organization for the arts in Mobile.[161] Mobile is also host to the Joe Jefferson Players, Alabama's oldest continually running community theatre. The group debuted on December 17, 1947, and was named in honor of comedic actor Joe Jefferson, who spent part of his teenage years in Mobile.[162]

Museums

[edit]

Battleship Memorial Park is a military park on the shore of Mobile Bay. It features the World War II era battleship USS Alabama, the World War II era submarine USS Drum, Korean War and Vietnam War Memorials, and historical military equipment.[163] The Fort of Colonial Mobile is a reconstruction of the city's original Fort Condé, built on the original fort's footprint. It serves as the official welcome center and a colonial-era living history museum.[28]

The History Museum of Mobile showcases centuries of local history in the Old City Hall.[164] The Phoenix Fire Museum in the restored Phoenix Volunteer Fire Company Number 6 building covers fire companies dating to 1838.[165] The Mobile Police Department Museum chronicles the history of the city's law enforcement.[166] The Mobile Medical Museum in the French colonial-style Vincent-Doan House chronicles the history of medicine in the city.[167] The Mobile Carnival Museum houses the city's Mardi Gras history and memorabilia.[168]

The Bragg-Mitchell Mansion (1855), Richards DAR House (1860), and the Condé-Charlotte House (1822) are antebellum house museums.[169][170][171] The Oakleigh Historic Complex are three house museums that portray the daily lives of enslaved, working class, and upper class people during the 19th century.[172]

The Gulf Coast Exploreum Science Center is a non-profit science center located in downtown.[173] The Dauphin Island Sea Lab is located south of the city, on Dauphin Island near the mouth of Mobile Bay.[174] On the University of South Alabama campus is the USA Archaeology Museum hosting artifacts from throughout the Gulf Coast region.[175] Airbus has an aerospace museum named Flightworks.[176] In the old Press-Register building, there is the Alabama Contemporary Art Center, which contains artworks by living artists.[177][178]

Historic architecture

[edit]

Mobile has surviving antebellum architectural examples of the Creole cottage, Greek Revival, Gothic Revival, and Italianate styles.[179] The earliest homes and fortifications were simple wooden structures, elevated on pilings driven into the frequently soaked soil. Early cottages, similar to those in other French settlements, were built as rows of two or three separate rooms each with a front and rear door that often opened onto an external porch running the length of the home. Kitchens were separate buildings. Some of these wooden structures rotted away in the 1700s.[180] Fires in 1827 and 1839 destroyed the city's remaining wooden colonial architecture.[181]

Wood continued to be used for nearly all homes in the 1800s, and the colonial cottages evolved into what became known as the Creole cottage in the 1840s. Creole cottages, such as the Carlen House, have front and rear porches covered by the roof. They run parallel to the street, often with a chimney at either end.[180] The 1827 fire and an economic boom in the 1830s allowed much of the city to be rebuilt, often in the optimistic and then-popular Greek Revival style. Structures like the Mobile City Hospital were built on an imposing scale with round doric columns in their facades.[182] A simplified Gothic Revival style gained popularity in the 1850s, with cresting along some rooflines and simple tracery framing the windows.[183] The Italianate style emerged before the Civil War and thrived after it. Italianate detailing can be seen in surviving examples such as the Martin Horst House, with its cast iron rails, elaborate exterior molding, bracketed eaves, and parapet around the hipped roof.[184] Italianate storefronts became common in downtown Mobile until they were surpassed by the Victorian style in the late 1800s.[185] Victorian cottages with board-and-batten siding also became popular in the late 1800s, but few survive.[186] The city's lone example of the Egyptian Revival style is the Scottish Rite Temple, with Egyptian motifs, including obelisks and sphinxes.[187] Other architectural styles in the city include shotgun houses, Colonial Revival, Tudor Revival, Spanish Colonial Revival, and Beaux-Arts.[179]

The city's historic districts include: Old Dauphin Way, Oakleigh Garden, Lower Dauphin Street, Leinkauf, De Tonti Square, Church Street East, Ashland Place, Campground, and Midtown.[179] Many storefronts from the 1800s still stand along Lower Dauphin Street. Renovations to the ground floors of some buildings often leave the upper floors untouched.[188] The Oakleigh Garden District is centered around the most photographed house in Mobile, Oakleigh. Many bracketed Italianate residences were later built around it.[189]

The Cathedral Basilica of the Immaculate Conception was built on the colonial-era Campo Santo cemetery, of which no trace remains.[190] Several historic cemeteries were established shortly after the colonial era. The Church Street Graveyard contains above-ground tombs and monuments spread over 4 acres (2 ha) and was founded in 1819.[191] The nearby 120-acre (49 ha) Magnolia Cemetery was established in 1836 and served as Mobile's primary burial site during the 19th and early 20th centuries.[192] Mobile's Jewish community dates back to the 1820s, and the city has two historic Jewish cemeteries, Sha'arai Shomayim Cemetery and Ahavas Chesed Cemetery. Sha'arai Shomayim is the older of the two.[193]

Sports

[edit]

Football

[edit]Football is the most popular spectator sport in the state.[194] Alabama has never had a top-level professional football team in the NFL,[195] but Mobile is one of several Alabama cities with a college football tradition.[196] Mobile has been home to the Senior Bowl since 1951, featuring the best college seniors in NCAA football.[197]

Mobile is the home of two football stadiums. The Ladd-Peebles Stadium opened in 1948 and has a current capacity of 40,646, making it the fourth-largest stadium in the state.[198] Hancock Whitney Stadium opened in 2020 on the campus of University of South Alabama and has a current capacity of 25,450.[199]

The 68 Ventures Bowl, originally known as the Mobile Alabama Bowl and later the GMAC Bowl, GoDaddy.com Bowl, Dollar General Bowl, and LendingTree Bowl, has been played at Hancock Whitney Stadium since 2021. The game was originally played at Ladd–Peebles Stadium from 1999 to 2020. It features opponents from the Sun Belt and Mid-American conferences.[200] Since 1988, Ladd–Peebles Stadium has hosted the Alabama-Mississippi All-Star Classic. The top graduating high school seniors from their respective states compete each June.[201]

The University of South Alabama in Mobile established a football team in 2007, which went undefeated in its 2009 inaugural season. Their program moved to Division I/FBS in 2013 as a member of the Sun Belt Conference. The team currently plays at Hancock Whitney Stadium, after playing at Ladd-Peebles Stadium prior to the start of the 2020 Season.[202]

Other sports and facilities

[edit]

Mobile has been home to Minor League Baseball teams from the late nineteenth century to 2019. Three Southern League teams operated out of Mobile intermittently in the nineteenth century: the Swamp Angels, Blackbirds, and Bluebirds. In the twentieth century, several teams, each called the Bears, operated at different times.[203] Mobile's Hank Aaron Stadium was the home of the Minor League Mobile BayBears from 1997 to 2019.[204]

South Alabama basketball is a mid-major team in the Sun Belt Conference. They play their home games at the Mitchell Center.[205] The Archbishop Lipscomb Athletic Complex is home of AFC Mobile, which is a National Premier Soccer League team.[206] The public Mobile Tennis Center includes over 50 courts, all lighted and hard-court.[207]

For golfers, Magnolia Grove, part of the Robert Trent Jones Golf Trail, has 36 holes. The Falls course was recently named the best par 3 course in America.[208] The Mitchell Company Tournament of Champions was played annually at Magnolia Grove from 1999 through 2007. The Mobile Bay LPGA Classic took its place in 2008, also held at Mobile's Magnolia Grove.[209]

Mobile is home to the Azalea Trail Run, which races through historic midtown and downtown Mobile. This 10k run has been an annual event since 1978.[210] The Azalea Trail Run is one of the premier 10k road races in the United States, attracting runners from all over the world.[211]

Parks and recreation

[edit]

The Mobile Botanical Gardens feature a variety of flora spread over 100 acres (40 ha). It contains the Millie McConnell Rhododendron Garden with 1,000 evergreen and native azaleas and the 30-acre (12 ha) Longleaf Pine Habitat.[212] Bellingrath Gardens and Home, located on Fowl River, is a 65-acre (26 ha) botanical garden and historic 10,500-square-foot (975 m2) mansion that dates to the 1930s.[213] The 5 Rivers Delta Resource Center is a facility that allows visitors to learn about and access the Mobile, Tensaw, Apalachee, Middle, Blakeley, and Spanish rivers.[214] It was established to serve as an easily accessible gateway to the Mobile-Tensaw River Delta.[215] It offers boat and adventure tours, a small theater, an exhibit hall, meeting facilities, walking trails, and a canoe and kayak landing.[216]

Mobile has more than 45 public parks within its limits, with some that are of special note.[217] Bienville Square is a historic park in the Lower Dauphin Street Historic District. It assumed its current form in 1850 and is named for Mobile's founder, Jean-Baptiste Le Moyne, Sieur de Bienville.[218] It was once the principal gathering place for residents, when the city was smaller, and remains popular today. Cathedral Square is a one-block performing arts park, also in the Lower Dauphin Street Historic District, which is overlooked by the Cathedral Basilica of the Immaculate Conception.[219]

Spanish Plaza is a downtown park that honors the Spanish phase of the city between 1780 and 1813. It features the Arches of Friendship, a fountain presented to Mobile by the city of Málaga, Spain.[220] Langan Park, the largest of the parks at 720 acres (291 ha), features lakes, natural spaces, and contains the Mobile Museum of Art, Azalea City Golf Course, Mobile Botanical Gardens and Playhouse in the Park.[217]

Government

[edit]

Since 1985 the government of Mobile has consisted of a mayor and a seven-member city council.[221] The council members are elected from each of the seven city council single-member districts (SMDs). A supermajority of five votes is required to conduct most council business.[222]

This form of city government was chosen by the voters after the previous form of government, which had three city commissioners, each elected at-large, was ruled in 1975 to substantially dilute the minority vote and violate the Voting Rights Act in Bolden v. City of Mobile. The three at-large commissioners each required a majority vote to win. Due to appeals, the case took time to reach settlement and establishment of a new electoral system.[223] Municipal elections are held every four years and are nonpartisan.[224]

Sam Jones was elected in 2005 as the first African-American mayor of Mobile. He was re-elected for a second term in 2009 without opposition.[225] His administration continued the focus on downtown redevelopment and bringing industries to the city. He ran for a third term in 2013 but was defeated by Sandy Stimpson. Stimpson took office on November 4, 2013, and was re-elected on August 22, 2017 and again on August 24, 2021.[226][227] Spiro Cheriogotis was elected to become mayor when Stimpson's term ends on November 2, 2025.[228]

Mobile city has 2,167 employees. Of the property tax paid in the city, 11% goes to the city, 32% goes to the county, 10% goes to the state, and 47% goes to the school districts. The city has a 5% sales tax. For 2024, the city received $281.7 million in sales tax, $34.5 million in property tax, and $90.1 million dollars for services such as business licenses. The total revenue for the city was $514.3 million, and the total expenditures was $455.3 million for 2024.[229]

Education

[edit]

Public schools

[edit]Public schools in Mobile are operated by the Mobile County Public School System (MCPSS). MCPSS has an enrollment of approximately 52,000 students at 92 schools, employs approximately 7,200 public school employees,[230][231] and had a budget in 2024–2025 of $843 million.[232] The State of Alabama operates the Alabama School of Mathematics and Science on Dauphin Street in Mobile, which boards advanced Alabama high school students. It was founded in 1989 to identify, challenge, and educate future leaders.[233]

Private schools

[edit]UMS-Wright Preparatory School is an independent co-educational preparatory school.[234] It assumed its current configuration in 1988, when the University Military School (founded 1893) and the Julius T. Wright School for Girls (1923) merged to form UMS-Wright.[235] Many parochial schools belong to the Roman Catholic Archdiocese of Mobile, including McGill-Toolen Catholic High School.[234] Protestant schools include St. Paul's Episcopal School and Faith Academy.[234]

Universities and colleges

[edit]The University of South Alabama is a public, doctoral-level university established in 1963.[236] Faulkner University is a four-year private Church of Christ-affiliated university based in Montgomery, Alabama. Faulkner founded the Mobile campus in 1975 and offers bachelor's degrees[237] and associate degrees.[238] Spring Hill College, chartered in 1830, was the first Catholic college in the southeastern United States and is the third oldest Jesuit college in the country.[239] Spring Hill College is a four-year private college with graduate programs[240] and undergraduate divisions.[241]

Founded in 1927, Bishop State Community College is a public, historically African American, community college with four campuses in Mobile.[242] Several post-secondary vocational institutions have a campus in Mobile including Fortis College, Virginia College, ITT Technical Institute and Remington College.[243]

Media

[edit]Mobile's Press-Register is Alabama's oldest active newspaper, first published in 1813.[244] The paper focuses on Mobile and Baldwin counties and the city of Mobile, but also serves southwestern Alabama and southeastern Mississippi.[244] Mobile's alternative newspaper is the Lagniappe which was founded on the 24th of July 2002.[245] Visit Mobile is a marketing agency website that is focused on tourism in Mobile.[246]

Mobile is served locally by several over-the-air television stations including WKRG 5 (CBS), WALA 10 (Fox), WPMI 15 (Roar), WMPV 21 (religious), WDPM 23 (religious), WEIQ 42 (PBS), and WFNA 55 (The CW).[247] The region is also served by WEAR 3 (ABC, with NBC on DT2), WSRE 31 (PBS), WHBR 34 (religious), WFGX 35 (MyNetworkTV), WJTC 44 (independent), WFBD 48 (America One), WPAN 53 (Jewelry Television), and WAWD 58 (independent), all out of the Pensacola, Florida area.[247] Mobile is part of the Mobile–Pensacola–Fort Walton Beach designated market area, as defined by Nielsen Media Research. The Mobile-Pensacola-Fort Walton Beach market is ranked 57th in the nation for the 2024–25 television season.[248]

A total of 43 FM radio stations and 12 AM radio stations are located around the Mobile area and provide signals sufficiently strong to serve Mobile.[249] Fourteen FM radio stations transmit from Mobile: WAVH, WBHY, WBLX, WDLT, WHIL, WKSJ, WKSJ-HD2, WLVM, WMXC, WMXC-HD2, WQUA, WRKH, WRKH-HD2, and WZEW. Nine AM radio stations transmit from Mobile: WBHY, WABF, WGOK, WIJD, WLPR, WMOB, WNGL, WNTM, and WXQW. The content ranges from Christian Contemporary to Hip hop to Top 40.[250] In fall 2025, Nielsen ranked Mobile's radio market as the 101st in the US.[251]

Infrastructure

[edit]Transportation

[edit]

Air

[edit]Local airline passengers are served by the Mobile Regional Airport, with direct connections to four major hub airports.[252] It is served by American Eagle, with service to Dallas/Fort Worth International Airport and Charlotte/Douglas International Airport; United Express, with service to George Bush Intercontinental Airport and Delta Connection, with service to Hartsfield-Jackson International Airport.[252] The Mobile Downtown Airport at the Brookley Aeroplex serves corporate, cargo, and private aircraft.[252]

Rail

[edit]Mobile is served by four Class I railroads, including the Canadian National Railway (CNR), CSX Transportation (CSX), the Kansas City Southern Railway (KCS), and the Norfolk Southern Railway (NS).[253] The Alabama and Gulf Coast Railway (AGR), a Class III railroad, links Mobile to the Burlington Northern and Santa Fe Railway (BNSF) at Amory, Mississippi. These converge at the Port of Mobile, which provides intermodal freight transport service to companies engaged in importing and exporting. Other railroads include the CG Railway (CGR), a rail ship service to Coatzacoalcos, Veracruz, and the Terminal Railway Alabama State Docks (TASD), a switching railroad.[253]

The city was served by Amtrak's Sunset Limited passenger train service until 2005, when the service was suspended due to the effects of Hurricane Katrina.[254][255] However, efforts to restart passenger rail service between Mobile and New Orleans were revived in 2019 by the 21-member Southern Rail Commission after receiving a $33 million Federal Railroad Administration grant in June of that year.[256] Louisiana quickly dedicated its $10 million toward the project, and Mississippi initially balked before committing its $15 million sum but Governor Kay Ivey resisted committing the estimated $2.7 million state allocation from Alabama because of concerns regarding long-term financial commitments and potential competition with freight traffic from the Port of Mobile.[257]

The Winter of 2019 was marked by repeated postponement of votes by the Mobile City Council as it requested more information on how rail traffic from the port would be impacted and where the Amtrak station would be built as community support for the project became more vocal, especially among millennials.[258] A day before a deadline in the federal grant matching program being used to fund the project, the city council committed about $3 million in a 6–1 vote.[259]

About $2.2 million was still needed for infrastructure improvements and the train station must still be built before service begins. Potential locations for the station include at the foot of Government Street in downtown and in the Mobile Aeroplex at Brookley, which was favored by the Port of Mobile.[260] Eventually, it was determined that a pocket track and a platform would be constructed for service to resume.[261] On July 1, 2025, Amtrak announced that the new train, dubbed the Mardi Gras Service, would begin on August 18, 2025, with two daily return trips.[262]

Roadways, bus and cycling

[edit]

Two major interstate highways and a spur converge in Mobile. Interstate 10 runs northeast to southwest across the city, while Interstate 65 starts in Mobile at Interstate 10 and runs north. Interstate 165 connects to Interstate 65 north of the city in Prichard and joins Interstate 10 in downtown Mobile.[263] Mobile is well served by many major highway systems. US Highways US 31, US 43, US 45, US 90, and US 98 radiate from Mobile traveling east, west, and north. Mobile has three routes east across the Mobile River and Mobile Bay into neighboring Baldwin County. Interstate 10 leaves downtown through the George Wallace Tunnel under the river and then over the bay across the Jubilee Parkway to Spanish Fort and Daphne. US 98 leaves downtown through the Bankhead Tunnel under the river, onto Blakeley Island, and then over the bay across the Battleship Parkway into Spanish Fort. US 90 travels over the Cochrane–Africatown USA Bridge to the north of downtown onto Blakeley Island, where it becomes co-routed with US 98.[263]

Mobile's public transportation is the Wave Transit System which features buses with 18 fixed routes and neighborhood service.[264] Baylinc is a public transportation bus service provided by the Baldwin Rural Transit System in cooperation with the Wave Transit System that provides service between eastern Baldwin County and downtown Mobile. Baylinc operates Monday through Friday.[265] Greyhound Lines provides intercity bus service between Mobile and many locations throughout the United States. Mobile is served by several taxi and limousine services.[266]

To leverage Mobile's waterways for recreational use, The Three Mile Creek Greenway Trail is being designed and implemented under the instruction of the City Council. The linear park will ultimately span seven miles, from Langan (Municipal) Park to Dr. Martin Luther King Junior Avenue, and include trailheads, sidewalks, and bike lanes. The existing greenway is centered at Tricentennial Park.[267]

The Wave Transit System provides fixed-route bus and demand-response service in Mobile.[268]

Water

[edit]The Port of Mobile has public deepwater terminals with direct access to 1,500 miles (2,400 km) of inland and intracoastal waterways serving the Great Lakes, the Ohio and Tennessee river valleys (via the Tennessee-Tombigbee Waterway), and the Gulf of Mexico.[253] The Alabama State Port Authority owns and operates the public terminals at the Port of Mobile.[253] The public terminals handle containerized, bulk, breakbulk, roll-on/roll-off, and heavy-lift cargoes.[253] The port is also home to private bulk terminal operators, as well as a number of highly specialized shipbuilding and repair companies with two of the largest floating dry docks on the Gulf Coast.[253]

The city was a home port for cruise ships from Carnival Cruise Lines.[269] The first cruise ship to call the port home was the Holiday, which left the city in November 2009 so that a larger and newer ship could take its place. The Carnival Fantasy operated from Mobile from then on until the Carnival Elation arrived in May 2010.[270] In early 2011, Carnival announced that despite fully booked cruises, the company would cease operations from Mobile in October 2011. This cessation of cruise service left the city with an annual debt service of around two million dollars related to the terminal.[271] In September 2015, Carnival announced that the Carnival Fantasy was relocating from Miami, Florida, to Mobile and would offer four- and five-night cruises to Mexico that started in November 2016 through November 2017.[272] Her first departure from Mobile left on November 9, 2016, on a five-night cruise to Cozumel and Progreso. Carnival Fascination will be replacing Carnival Fantasy in 2022.[273]<

Utilities

[edit]

Natural gas has been used in Mobile since 1836 when natural gas was used for lighting. Between 1933 and 2016 natural gas was provided by Mobile Gas.[274] In 2016, Spire Inc. bought EnergySouth, Inc, the parent company of Mobile Gas and has been provide the service to the surrounding community since then.[275][276]

The water for Mobile is provided by Mobile Area Water and Sewer System (MAWSS). When MAWSS was founded in 1814, it used Three-Mile Creek to provide water to the city.[277] In 1952, MAWSS constructed a dam at Tanner Williams road to block Big Creek stream creating Big Creek Lake, a water reservoir for the city and the surrounding area.[278]

In 1884 with the demonstration of an incandescent lightbulb, Mobile Electric Company began providing electricity to the city as an alternative lighting method. In 1925, Alabama Power bought the Mobile Electric Company.[279] Electricity is still available from Alabama Power to this day.[275] Alabama Power owns and operates James M. Barry Electric Generating Plant, fueled by coal and natural gas, and Theodore Cogen Facility, fueled by natural gas. These two power plants generate a total capacity of 3,519,870 kW for the surrounding communities.[280]

Healthcare

[edit]

Mobile serves the central Gulf Coast as a regional center for medicine.[281] The 200-year-old Mobile County Health Department (MCHD) provides education and preventive health services to Mobile and surrounding areas.[282] Infirmary Health is Alabama's largest nonprofit, non-governmental health care system. It includes their flagship hospital Mobile Infirmary, two emergency centers and three outpatient surgery centers. Mobile Infirmary is the largest nonprofit hospital in the state.[283][284]

University of South Alabama Health (USA Health) operates 30 locations in the Mobile area, including three hospitals: USA Health Providence Hospital, the Children's & Women's Hospital, and University Hospital.[283] Providence Hospital was founded in 1854 by the Daughters of Charity.[284] In 2023, USA Health acquired Providence Hospital from its private Catholic ownership.[285] The University of South Alabama Medical Center was founded in 1830 as the old city-owned Mobile City Hospital and associated medical school. A teaching hospital, it is designated as Mobile's only level I trauma center by the Alabama Department of Public Health[284][286][287] and is also a regional burn center.[288] Children's & Women's Hospital is dedicated exclusively to the care of women and minors.[288] In 2008, the University of South Alabama opened the Mitchell Cancer Center Institute, which includes the first academic cancer research center in the central Gulf Coast region.[289]

BayPointe Hospital and Children's Residential Services is the city's only psychiatric hospital. It houses a residential unit for children, an acute unit for children and adolescents, and an age-segregated involuntary hospital unit for adults undergoing evaluation ordered by the Mobile Probate Court.[290] Springhill Medical Center was founded in 1975 and is Mobile's only for-profit facility.[288]

Notable people

[edit]- Sanford Bishop (born 1947) – U.S. representative for Georgia[291]

- Jerry Carl (born 1958) – U.S. representative for Alabama[292]

- Rick Crawford (born 1958) – racing driver[293]

- Anne Haney Cross (born 1956) – neurologist[294]

- George Washington Dennis (c. 1825 – 1916) – former slave, entrepreneur, real estate developer, and advocate for Black rights[295][296][297]

- Michael Figures (1947–1996) – lawyer and politician[298]

- Shomari Figures (born 1985) – U.S. representative[299]

- Thomas Figures (1944–2015) – first African American assistant district attorney and assistant United States Attorney[300]

- Cale Gale (born 1985) – racing driver[301]

- Dorothy E. Hayes (1935–2015) – graphic designer, educator[302][303]

- Vivian Malone Jones (1942–2005) – director in the EPA, integrated the University of Alabama and was its first black graduate[304]

- Charles Keller (1868–1949) – U.S. Army Brigadier General and oldest Army officer to serve on active duty during World War II[305][306]

- Antonio Lang (born 1972) – professional basketball player and coach[307]

- Anne Bozeman Lyon (1860–1936) – writer[308]

- Alexander Lyons (1867–1939) – rabbi[309]

- Flo Milli (born 2000) – musician[310]

- William Moody (1954–2013) – professional wrestling manager known for his time in WWE under the name "Paul Bearer"[311]

- Dan Povenmire (born 1963) – animator and co-creator of Phineas and Ferb[312]

- Bubba Wallace (born 1993) – racing driver[313]

Sister cities

[edit]Mobile has nine sister cities:[314]

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ "Municipalities of Alabama Incorporation Dates" (PDF). Alabama League of Municipalities. Archived from the original (PDF) on March 26, 2024. Retrieved March 17, 2024.

- ^ "An Act to provide for Government of the Town of Mobile. —Passed January 20, 1814". A Digest of the Laws of the State of Alabama: Containing The Statutes and Resolutions in Force at the end of the General Assembly in January 1823. New-York: Ginn & Curtis. 1828. Title 62. ch. XII. pp. 780–781 – via Internet Archive.

- ^ "An Act to incorporate the City of Mobile. —Passed December 17, 1819". A Digest of the Laws of the State of Alabama: Containing The Statutes and Resolutions in Force at the end of the General Assembly in January 1823. New-York: Ginn & Curtis. 1828. Title 62. ch. XVI. pp. 784–791 – via Internet Archive.

- ^ a b "2023 U.S. Gazetteer Files". United States Census Bureau. Mobile City. Retrieved March 17, 2024.

- ^ United States Census Bureau (December 29, 2022). "2020 Census Qualifying Urban Areas and Final Criteria Clarifications". Federal Register.

- ^ a b c "Mobile, Alabama". Geographic Names Information System. United States Geological Survey, United States Department of the Interior.

- ^ a b c "Explore Census Data". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved March 17, 2024.

- ^ a b "City and Town Population Totals: 2020–2022". United States Census Bureau. March 14, 2024. Retrieved March 17, 2024.

- ^ "Zip Code Lookup". USPS. Retrieved March 17, 2024.

- ^ "P1. Race: Total Population". 2020 Census. U.S. Census Bureau. Retrieved April 19, 2022.

- ^ "Mobile Alabama". Britannica Online. Retrieved October 19, 2007.

- ^ Drechsel, Emanuel (1997). Mobilian Jargon: Linguistic and Sociohistorical Aspects of a Native American Pidgin. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-824033-3.

- ^ a b "Waterborne Commerce Statistics: Calendar Year 2010" (PDF). United States Army Corps of Engineers. Archived from the original (PDF) on February 16, 2013. Retrieved November 23, 2010.

- ^ Bunn, Mike (May 8, 2017). "Battle of Fort Blakeley". Encyclopedia of Alabama. Retrieved July 23, 2019.

- ^ "General Information". Mobile Museum of Art. Archived from the original on September 28, 2007. Retrieved October 23, 2007.

- ^ a b c "About Region". SeniorsResourceGuide.com. Archived from the original on September 28, 2007. Retrieved May 5, 2007.

- ^ a b c "Mobile Mardi Gras Timeline". The Museum of Mobile. Archived from the original on December 5, 2008. Retrieved November 14, 2007.

- ^ Thomason, Michael (2001). Mobile: The New History of Alabama's First City. Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press. pp. 17–20. ISBN 0-8173-1065-7.

- ^ "The Mobilian Indians" (PDF). The Old Mobile Project Newsletter. University of South Alabama Center for Archaeological Studies. Fall 1998. pp. 1–4. Archived from the original (PDF) on November 27, 2007. Retrieved November 19, 2007.

- ^ Turner-Neal, Chris (August 30, 2022). "Old Mobile". 64 Parishes. Louisiana Endowment for the Humanities.

- ^ a b Waselkov, Gregory (2005). Old Mobile Archaeology. Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Books. pp. 1–5, 37. ISBN 978-0-8173-8473-9.

- ^ Thomason (2001), Mobile, pp. 20 and 24

- ^ "National Historic Landmark Nomination – Old Mobile Site" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on August 24, 2003.

- ^ a b Higginbotham, Jay (1977). Old Mobile: Fort Louis de la Louisiane, 1702–1711. Museum of the City of Mobile. pp. 106–107. ISBN 0-914334-03-4..

- ^ Thomason (2001), Mobile, pp. 20–21.

- ^ a b Thomason, Michael (2001). Mobile: The New History of Alabama's First City. Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press. pp. 17–27. ISBN 0-8173-1065-7.

- ^ Hoffman, Roy (February 24, 2002). "Digging old Mobile". Mobile Press-Register. Archived from the original on September 17, 2002.

- ^ a b c d "History Museum of Mobile". Museumofmobile.com. Retrieved March 4, 2022.

- ^ "Historic Fort Conde". Museum of Mobile. Retrieved October 18, 2007.

- ^ "Early European Conquests and the Settlement of Mobile". Alabama Department of Archives and History. Archived from the original on July 16, 2011. Retrieved October 20, 2007.

- ^ "Mobile: Alabama's Tricentennial City". Alabama Department of Archives and History. Archived from the original on August 10, 2007. Retrieved October 20, 2007.

- ^ a b Thomason (2001), Mobile, pp. 44–45

- ^ Zietz, Robert (1994). The Gates of Heaven: Congregation Sha'arai Shomayim, the first 150 years, Mobile, Alabama, 1844–1994. Mobile, Alabama: Congregation Sha'arai Shomayim. pp. 7–39.

- ^ a b c Delaney, Caldwell (1981) [1953]. The Story of Mobile. Mobile, Alabama: Gill Press. p. 45. ISBN 0-940882-14-0.

- ^ a b c David P. Ogden (January 2005). The Fort Barrancas Story. Eastern National Parks. p. 2. ISBN 978-1-888213-15-7.

- ^ "James Wilkinson". War of 1812. Archived from the original on November 3, 2007. Retrieved October 20, 2007.

- ^ a b c d Thomason, Michael (2001). Mobile: the new history of Alabama's first city. Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press. p. 65. ISBN 0-8173-1065-7.

- ^ Taylor, George Rogers (1969). The Transportation Revolution, 1815–1860. Rinehart. ISBN 978-0873321013.

- ^ Beckert, Sven (2014). Empire of Cotton: A Global History. US: Vintage Books Division Penguin Random House. ISBN 978-0-375-71396-5.

- ^ Eugene R. Dattel, "Cotton in a Global Economy: Mississippi (1800–1860)" Archived June 15, 2019, at the Wayback Machine, October 2006, Mississippi History Now, online publication of the Mississippi Historical Society

- ^ Thomason, Michael (2001). Mobile: The New History of Alabama's first city. Tuscaloosa, Alabama: University of Alabama Press. pp. 79–80. ISBN 0-8173-1065-7.

- ^ Thomason, Michael (2001). Mobile: the new history of Alabama's first city. Tuscaloosa, Alabama: University of Alabama Press. pp. 69–71. ISBN 0-8173-1065-7.

- ^ Hurston, Zora Neal (October 1927). "Cudjo's Own Story of the Last African Slaver". The Journal of Negro History. 12 (4): 648–663. doi:10.2307/2714041. JSTOR 2714041.

- ^ "Population of the 100 Largest Urban Places: 1860". United States Bureau of the Census. Archived from the original on November 26, 2001. Retrieved November 2, 2007.

- ^ a b "Census Data for the Year 1860". Inter-University Consortium for Political and Social Research. Archived from the original on May 6, 2007. Retrieved November 13, 2007.

- ^ "H. L. Hunley". Naval Historical Center. Archived from the original on October 14, 2007. Retrieved October 20, 2007.

- ^ a b Thomason, Michael (2001). 'Mobile: the new history of Alabama's first city. Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press. p. 113. ISBN 0-8173-1065-7.

- ^ Delaney, Caldwell (1981) [1953]. The Story of Mobile. Mobile, Alabama: Gill Press. pp. 144–146. ISBN 0-940882-14-0.

- ^ Thomason, Michael (2001). Mobile: the new history of Alabama's first city. Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press. p. 153. ISBN 0-8173-1065-7.

- ^ Thomason, Michael (2001). Mobile: the new history of Alabama's first city. Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press. p. 145. ISBN 0-8173-1065-7.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Thomason, Michael (2001). Mobile: The New History of Alabama's First City. Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press. pp. 154–169. ISBN 0-8173-1065-7.

- ^ a b c James Blacksher, Edward Still, Nick Quinton, Cullen Brown, and Royal Dumas, "Voting Rights in Alabama 1982–2006", July 2006, RenewtheVRA.org, accessed March 12, 2015

- ^ "Red Imported Fire Ants". Defense Centers for Public Health. Defense Health Agency. September 26, 2024. Retrieved July 6, 2025.

- ^ "History of the Red Imported Fire Ant". Texas Imported Fire Ant Research and Management Project. Texas A&M. Retrieved May 22, 2025.

- ^ a b c d e Thomason, Michael (2001). Mobile: The New History of Alabama's First City. Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press. pp. 213–217. ISBN 0-8173-1065-7.

- ^ "The Four Towns: Mobile". The War | Ken Burns | PBS. Retrieved December 20, 2024.

- ^ Scotty E. Kirkland, "Alabama Drydock and Shipbuilding Company (ADDSCO)". Encyclopedia of Alabama online, 2008, update August 10, 2015

- ^ Bill Patterson, "The Founding of the Industrial Development Board of the City of Mobile: The Port City's Reluctant Use of Subsidies", Gulf South Historical Review 2000 15(2): 21–40,

- ^ a b Thomason (2001), Mobile, pp. 260–261

- ^ Levins, Angela (August 6, 2015). "Voting Rights Act turns 50: What did it change?". AL.com.

- ^ Kirkland, Scott E. (2021). "Toward Equal Justice: A Legacy of Resistance, Sacrifice, and Service" (PDF). Mobile Museum of Art. Retrieved May 24, 2025.

- ^ "Bolden v. Mobile". Encyclopedia of Alabama.

- ^ Zickgraf, Ryan (February 28, 2022). "Segregation Is Still Alive in Mardi Gras's Birthplace". Jacobin.

- ^ "Mobile Aeroplex at Brookley". Mobile Port Authority. Retrieved May 22, 2025.

- ^ Mitchell, Garry (February 11, 2007). "Mobile's Economy Thrives; Port City Also Seeks Aircraft, Steel Mill Deals". The Tuscaloosa News. The Associated Press.

- ^ a b "Mobile Wins Title of All American City". City of Mobile. Archived from the original on October 17, 2007. Retrieved November 15, 2007.

- ^ "2005 State of the City". City of Mobile. Retrieved November 15, 2007.

- ^ "US Gazetteer files: 2010, 2000, and 1990". United States Census Bureau. February 12, 2011. Retrieved April 23, 2011.