Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Liquid crystal

View on Wikipedia

| Condensed matter physics |

|---|

|

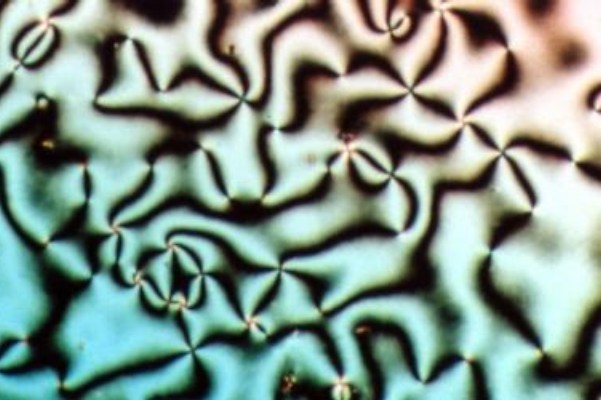

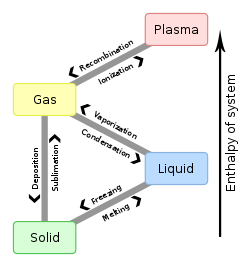

Liquid crystal (LC) is a state of matter whose properties are between those of conventional liquids and those of solid crystals. For example, a liquid crystal can flow like a liquid, but its molecules may be oriented in a common direction as in a solid. There are many types of LC phases, which can be distinguished by their optical properties (such as textures). The contrasting textures arise due to molecules within one area of material ("domain") being oriented in the same direction but different areas having different orientations. An LC material may not always be in an LC state of matter (just as water may be ice or water vapour).

Liquid crystals can be divided into three main types: thermotropic, lyotropic, and metallotropic. Thermotropic and lyotropic liquid crystals consist mostly of organic molecules, although a few minerals are also known. Thermotropic LCs exhibit a phase transition into the LC phase as temperature changes. Lyotropic LCs exhibit phase transitions as a function of both temperature and concentration of molecules in a solvent (typically water). Metallotropic LCs are composed of both organic and inorganic molecules; their LC transition additionally depends on the inorganic-organic composition ratio.

Examples of LCs exist both in the natural world and in technological applications. Lyotropic LCs abound in living systems; many proteins and cell membranes are LCs, as well as the tobacco mosaic virus.[1] LCs in the mineral world include solutions of soap and various related detergents, and some clays. Widespread liquid-crystal displays (LCD) use liquid crystals.

History

[edit]In 1888, Austrian botanical physiologist Friedrich Reinitzer, working at the Karl-Ferdinands-Universität, examined the physico-chemical properties of various derivatives of cholesterol which now belong to the class of materials known as cholesteric liquid crystals. Previously, other researchers had observed distinct color effects when cooling cholesterol derivatives just above the freezing point, but had not associated it with a new phenomenon. Reinitzer perceived that color changes in a derivative cholesteryl benzoate were not the most peculiar feature.

He found that cholesteryl benzoate does not melt in the same manner as other compounds, but has two melting points. At 145.5 °C (293.9 °F) it melts into a cloudy liquid, and at 178.5 °C (353.3 °F) it melts again and the cloudy liquid becomes clear. The phenomenon is reversible. Seeking help from a physicist, on March 14, 1888, he wrote to Otto Lehmann, at that time a Privatdozent in Aachen. They exchanged letters and samples. Lehmann examined the intermediate cloudy fluid, and reported seeing crystallites. Reinitzer's Viennese colleague von Zepharovich also indicated that the intermediate "fluid" was crystalline. The exchange of letters with Lehmann ended on April 24, with many questions unanswered. Reinitzer presented his results, with credits to Lehmann and von Zepharovich, at a meeting of the Vienna Chemical Society on May 3, 1888.[2]

By that time, Reinitzer had discovered and described three important features of cholesteric liquid crystals (the name coined by Otto Lehmann in 1904): the existence of two melting points, the reflection of circularly polarized light, and the ability to rotate the polarization direction of light.

After his accidental discovery, Reinitzer did not pursue studying liquid crystals further. The research was continued by Lehmann, who realized that he had encountered a new phenomenon and was in a position to investigate it: In his postdoctoral years he had acquired expertise in crystallography and microscopy. Lehmann started a systematic study, first of cholesteryl benzoate, and then of related compounds which exhibited the double-melting phenomenon. He was able to make observations in polarized light, and his microscope was equipped with a hot stage (sample holder equipped with a heater) enabling high temperature observations. The intermediate cloudy phase clearly sustained flow, but other features, particularly the signature under a microscope, convinced Lehmann that he was dealing with a solid. By the end of August 1889 he had published his results in the Zeitschrift für Physikalische Chemie.[3]

Lehmann's work was continued and significantly expanded by the German chemist Daniel Vorländer, who from the beginning of the 20th century until he retired in 1935, had synthesized most of the liquid crystals known. However, liquid crystals were not popular among scientists and the material remained a pure scientific curiosity for about 80 years.[4]

After World War II, work on the synthesis of liquid crystals was restarted at university research laboratories in Europe. George William Gray, a prominent researcher of liquid crystals, began investigating these materials in England in the late 1940s. His group synthesized many new materials that exhibited the liquid crystalline state and developed a better understanding of how to design molecules that exhibit the state. His book Molecular Structure and the Properties of Liquid Crystals[5] became a guidebook on the subject. One of the first U.S. chemists to study liquid crystals was Glenn H. Brown, starting in 1953 at the University of Cincinnati and later at Kent State University. In 1965, he organized the first international conference on liquid crystals, in Kent, Ohio, with about 100 of the world's top liquid crystal scientists in attendance. This conference marked the beginning of a worldwide effort to perform research in this field, which soon led to the development of practical applications for these unique materials.[6][7]

Liquid crystal materials became a focus of research in the development of flat panel electronic displays beginning in 1962 at RCA Laboratories.[8] When physical chemist Richard Williams applied an electric field to a thin layer of a nematic liquid crystal at 125 °C, he observed the formation of a regular pattern that he called domains (now known as Williams Domains). This led his colleague George H. Heilmeier to perform research on a liquid crystal-based flat panel display to replace the cathode ray vacuum tube used in televisions. But the para-azoxyanisole that Williams and Heilmeier used exhibits the nematic liquid crystal state only above 116 °C, which made it impractical to use in a commercial display product. A material that could be operated at room temperature was clearly needed.

In 1966, Joel E. Goldmacher and Joseph A. Castellano, research chemists in Heilmeier group at RCA, discovered that mixtures made exclusively of nematic compounds that differed only in the number of carbon atoms in the terminal side chains could yield room-temperature nematic liquid crystals. A ternary mixture of Schiff base compounds resulted in a material that had a nematic range of 22–105 °C.[9] Operation at room temperature enabled the first practical display device to be made.[10] The team then proceeded to prepare numerous mixtures of nematic compounds many of which had much lower melting points. This technique of mixing nematic compounds to obtain wide operating temperature range eventually became the industry standard and is still used to tailor materials to meet specific applications.

In 1969, Hans Keller succeeded in synthesizing a substance that had a nematic phase at room temperature, N-(4-methoxybenzylidene)-4-butylaniline (MBBA), which is one of the most popular subjects of liquid crystal research.[11] The next step to commercialization of liquid-crystal displays was the synthesis of further chemically stable substances (cyanobiphenyls) with low melting temperatures by George Gray.[12] That work with Ken Harrison and the UK MOD (RRE Malvern), in 1973, led to design of new materials resulting in rapid adoption of small area LCDs within electronic products.

These molecules are rod-shaped, some created in the laboratory and some appearing spontaneously in nature. Since then, two new types of LC molecules have been synthesized: disc-shaped (by Sivaramakrishna Chandrasekhar in India in 1977)[13] and cone or bowl shaped (predicted by Lui Lam in China in 1982 and synthesized in Europe in 1985).[14]

In 1991, when liquid crystal displays were already well established, Pierre-Gilles de Gennes working at the Université Paris-Sud received the Nobel Prize in physics "for discovering that methods developed for studying order phenomena in simple systems can be generalized to more complex forms of matter, in particular to liquid crystals and polymers".[15]

Design of liquid crystalline materials

[edit]A large number of chemical compounds are known to exhibit one or several liquid crystalline phases. Despite significant differences in chemical composition, these molecules have some common features in chemical and physical properties. There are three types of thermotropic liquid crystals: discotic, conic (bowlic), and rod-shaped molecules. Discotics are disc-like molecules consisting of a flat core of adjacent aromatic rings, whereas the core in a conic LC is not flat, but is shaped like a rice bowl (a three-dimensional object).[16][17] This allows for two dimensional columnar ordering, for both discotic and conic LCs. Rod-shaped molecules have an elongated, anisotropic geometry which allows for preferential alignment along one spatial direction.

- The molecular shape should be relatively thin, flat or conic, especially within rigid molecular frameworks.

- The molecular length should be at least 1.3 nm, consistent with the presence of long alkyl group on many room-temperature liquid crystals.

- The structure should not be branched or angular, except for the conic LC.

- A low melting point is preferable in order to avoid metastable, monotropic liquid crystalline phases. Low-temperature mesomorphic behavior in general is technologically more useful, and alkyl terminal groups promote this.

An extended, structurally rigid, highly anisotropic shape seems to be the main criterion for liquid crystalline behavior, and as a result many liquid crystalline materials are based on benzene rings.[18]

Liquid-crystal phases

[edit]The various liquid-crystal phases (called mesophases together with plastic crystal phases) can be characterized by the type of ordering. One can distinguish positional order (whether molecules are arranged in any sort of ordered lattice) and orientational order (whether molecules are mostly pointing in the same direction). Liquid crystals are characterized by orientational order, but only partial or completely absent positional order. In contrast, materials with positional order but no orientational order are known as plastic crystals.[19] Most thermotropic LCs will have an isotropic phase at high temperature: heating will eventually drive them into a conventional liquid phase characterized by random and isotropic molecular ordering and fluid-like flow behavior. Under other conditions (for instance, lower temperature), a LC might inhabit one or more phases with significant anisotropic orientational structure and short-range orientational order while still having an ability to flow.[20][21]

The ordering of liquid crystals extends up to the entire domain size, which may be on the order of micrometers, but usually not to the macroscopic scale as often occurs in classical crystalline solids. However some techniques, such as the use of boundaries or an applied electric field, can be used to enforce a single ordered domain in a macroscopic liquid crystal sample.[22] The orientational ordering in a liquid crystal might extend along only one dimension, with the material being essentially disordered in the other two directions.[23][24]

Thermotropic liquid crystals

[edit]Thermotropic phases are those that occur in a certain temperature range. If the temperature rise is too high, thermal motion will destroy the delicate cooperative ordering of the LC phase, pushing the material into a conventional isotropic liquid phase. At too low temperature, most LC materials will form a conventional crystal.[20][21] Many thermotropic LCs exhibit a variety of phases as temperature is changed. For instance, a particular type of LC molecule (called a mesogen) may exhibit various smectic phases followed by the nematic phase and finally the isotropic phase as temperature is increased. An example of a compound displaying thermotropic LC behavior is para-azoxyanisole.[25]

Nematic phase

[edit]

The simplest liquid crystal phase is the nematic. In a nematic phase, calamitic (rod-like) organic molecules lack a crystalline positional order, but do self-align with their long axes roughly parallel. The molecules are free to flow and their center of mass positions are randomly distributed as in a liquid, but their orientation is constrained to form a long-range directional order.[26]

The word nematic comes from the Greek νήμα (Greek: nema), which means "thread". This term originates from the disclinations: thread-like topological defects observed in nematic phases.

Nematics also exhibit so-called "hedgehog" topological defects. In two dimensions, there are topological defects with topological charges +1/2 and -1/2. Due to hydrodynamics, the +1/2 defect moves considerably faster than the -1/2 defect. When placed close to each other, the defects attract; upon collision, they annihilate.[27][28]

Most nematic phases are uniaxial: they have one axis (called a directrix) that is longer and preferred, with the other two being equivalent (can be approximated as cylinders or rods). However, some liquid crystals are biaxial nematic, meaning that in addition to orienting their long axis, they also orient along a secondary axis.[29] Nematic crystals have fluidity similar to that of ordinary (isotropic) liquids but they can be easily aligned by an external magnetic or electric field. Aligned nematics have the optical properties of uniaxial crystals and this makes them extremely useful in liquid-crystal displays (LCD).[8]

Nematic phases are also known in non-molecular systems: at high magnetic fields, electrons flow in bundles or stripes to create an "electronic nematic" form of matter.[30][31]

Smectic phases

[edit]

The smectic phases, which are found at lower temperatures than the nematic, form well-defined layers that can slide over one another in a manner similar to that of soap. The word "smectic" originates from the Latin word "smecticus", meaning cleaning, or having soap-like properties.[32] The smectics are thus positionally ordered along one direction. In the Smectic A phase, the molecules are oriented along the layer normal, while in the Smectic C phase they are tilted away from it. These phases are liquid-like within the layers. There are many different smectic phases, all characterized by different types and degrees of positional and orientational order.[20][21] Beyond organic molecules, Smectic ordering has also been reported to occur within colloidal suspensions of 2-D materials or nanosheets.[33][34] One example of smectic LCs is p,p'-dinonylazobenzene.[35]

Chiral phases or twisted nematics

[edit]

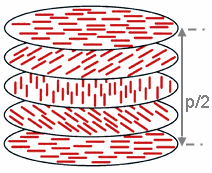

The chiral nematic phase exhibits chirality (handedness). This phase is often called the cholesteric phase because it was first observed for cholesterol derivatives. Only chiral molecules can give rise to such a phase. This phase exhibits a twisting of the molecules perpendicular to the director, with the molecular axis parallel to the director. The finite twist angle between adjacent molecules is due to their asymmetric packing, which results in longer-range chiral order. In the smectic C* phase (an asterisk denotes a chiral phase), the molecules have positional ordering in a layered structure (as in the other smectic phases), with the molecules tilted by a finite angle with respect to the layer normal. The chirality induces a finite azimuthal twist from one layer to the next, producing a spiral twisting of the molecular axis along the layer normal, hence they are also called twisted nematics.[21][23][24]

The chiral pitch, p, refers to the distance over which the LC molecules undergo a full 360° twist (but note that the structure of the chiral nematic phase repeats itself every half-pitch, since in this phase directors at 0° and ±180° are equivalent). The pitch, p, typically changes when the temperature is altered or when other molecules are added to the LC host (an achiral LC host material will form a chiral phase if doped with a chiral material), allowing the pitch of a given material to be tuned accordingly. In some liquid crystal systems, the pitch is of the same order as the wavelength of visible light. This causes these systems to exhibit unique optical properties, such as Bragg reflection and low-threshold laser emission,[36] and these properties are exploited in a number of optical applications.[4][23] For the case of Bragg reflection only the lowest-order reflection is allowed if the light is incident along the helical axis, whereas for oblique incidence higher-order reflections become permitted. Cholesteric liquid crystals also exhibit the unique property that they reflect circularly polarized light when it is incident along the helical axis and elliptically polarized if it comes in obliquely.[37]

Blue phases

[edit]Blue phases are liquid crystal phases that appear in the temperature range between a chiral nematic phase and an isotropic liquid phase. Blue phases have a regular three-dimensional cubic structure of defects with lattice periods of several hundred nanometers, and thus they exhibit selective Bragg reflections in the wavelength range of visible light corresponding to the cubic lattice. It was theoretically predicted in 1981 that these phases can possess icosahedral symmetry similar to quasicrystals.[39][40]

Although blue phases are of interest for fast light modulators or tunable photonic crystals, they exist in a very narrow temperature range, usually less than a few kelvins. Recently the stabilization of blue phases over a temperature range of more than 60 K including room temperature (260–326 K) has been demonstrated.[41][42] Blue phases stabilized at room temperature allow electro-optical switching with response times of the order of 10−4 s.[43] In May 2008, the first blue phase mode LCD panel had been developed.[44]

Blue phase crystals, being a periodic cubic structure with a bandgap in the visible wavelength range, can be considered as 3D photonic crystals. Producing ideal blue phase crystals in large volumes is still problematic, since the produced crystals are usually polycrystalline (platelet structure) or the single crystal size is limited (in the micrometer range). Recently, blue phases obtained as ideal 3D photonic crystals in large volumes have been stabilized and produced with different controlled crystal lattice orientations.[45]

Discotic phases

[edit]Disk-shaped LC molecules can orient themselves in a layer-like fashion known as the discotic nematic phase. If the disks pack into stacks, the phase is called a discotic columnar. The columns themselves may be organized into rectangular or hexagonal arrays. Chiral discotic phases, similar to the chiral nematic phase, are also known.

Conic phases

[edit]Conic LC molecules, like in discotics, can form columnar phases. Other phases, such as nonpolar nematic, polar nematic, stringbean, donut and onion phases, have been predicted. Conic phases, except nonpolar nematic, are polar phases.[46]

Lyotropic liquid crystals

[edit]

A lyotropic liquid crystal consists of two or more components that exhibit liquid-crystalline properties in certain concentration ranges. In the lyotropic phases, solvent molecules fill the space around the compounds to provide fluidity to the system.[47] In contrast to thermotropic liquid crystals, these lyotropics have another degree of freedom of concentration that enables them to induce a variety of different phases.

A compound that has two immiscible hydrophilic and hydrophobic parts within the same molecule is called an amphiphilic molecule. Many amphiphilic molecules show lyotropic liquid-crystalline phase sequences depending on the volume balances between the hydrophilic part and hydrophobic part. These structures are formed through the micro-phase segregation of two incompatible components on a nanometer scale. Soap is an everyday example of a lyotropic liquid crystal.

The content of water or other solvent molecules changes the self-assembled structures. At very low amphiphile concentration, the molecules will be dispersed randomly without any ordering. At slightly higher (but still low) concentration, amphiphilic molecules will spontaneously assemble into micelles or vesicles. This is done so as to 'hide' the hydrophobic tail of the amphiphile inside the micelle core, exposing a hydrophilic (water-soluble) surface to aqueous solution. These spherical objects do not order themselves in solution, however. At higher concentration, the assemblies will become ordered. A typical phase is a hexagonal columnar phase, where the amphiphiles form long cylinders (again with a hydrophilic surface) that arrange themselves into a roughly hexagonal lattice. This is called the middle soap phase. At still higher concentration, a lamellar phase (neat soap phase) may form, wherein extended sheets of amphiphiles are separated by thin layers of water. For some systems, a cubic (also called viscous isotropic) phase may exist between the hexagonal and lamellar phases, wherein spheres are formed that create a dense cubic lattice. These spheres may also be connected to one another, forming a bicontinuous cubic phase.

The objects created by amphiphiles are usually spherical (as in the case of micelles), but may also be disc-like (bicelles), rod-like, or biaxial (all three micelle axes are distinct). These anisotropic self-assembled nano-structures can then order themselves in much the same way as thermotropic liquid crystals do, forming large-scale versions of all the thermotropic phases (such as a nematic phase of rod-shaped micelles).

For some systems, at high concentrations, inverse phases are observed. That is, one may generate an inverse hexagonal columnar phase (columns of water encapsulated by amphiphiles) or an inverse micellar phase (a bulk liquid crystal sample with spherical water cavities).

A generic progression of phases, going from low to high amphiphile concentration, is:

- Discontinuous cubic phase (micellar cubic phase)

- Hexagonal phase (hexagonal columnar phase) (middle phase)

- Lamellar phase

- Bicontinuous cubic phase

- Reverse hexagonal columnar phase

- Inverse cubic phase (Inverse micellar phase)

Even within the same phases, their self-assembled structures are tunable by the concentration: for example, in lamellar phases, the layer distances increase with the solvent volume. Since lyotropic liquid crystals rely on a subtle balance of intermolecular interactions, it is more difficult to analyze their structures and properties than those of thermotropic liquid crystals.

Similar phases and characteristics can be observed in immiscible diblock copolymers.

Metallotropic liquid crystals

[edit]Liquid crystal phases can also be based on low-melting inorganic phases like ZnCl2 that have a structure formed of linked tetrahedra and easily form glasses. The addition of long chain soap-like molecules leads to a series of new phases that show a variety of liquid crystalline behavior both as a function of the inorganic-organic composition ratio and of temperature. This class of materials has been named metallotropic.[48]

Laboratory analysis of mesophases

[edit]Thermotropic mesophases are detected and characterized by two major methods, the original method was use of thermal optical microscopy,[49][50] in which a small sample of the material was placed between two crossed polarizers; the sample was then heated and cooled. As the isotropic phase would not significantly affect the polarization of the light, it would appear very dark, whereas the crystal and liquid crystal phases will both polarize the light in a uniform way, leading to brightness and color gradients. This method allows for the characterization of the particular phase, as the different phases are defined by their particular order, which must be observed. The second method, differential scanning calorimetry (DSC),[49] allows for more precise determination of phase transitions and transition enthalpies. In DSC, a small sample is heated in a way that generates a very precise change in temperature with respect to time. During phase transitions, the heat flow required to maintain this heating or cooling rate will change. These changes can be observed and attributed to various phase transitions, such as key liquid crystal transitions.

Lyotropic mesophases are analyzed in a similar fashion, though these experiments are somewhat more complex, as the concentration of mesogen is a key factor. These experiments are run at various concentrations of mesogen in order to analyze that impact.

Biological liquid crystals

[edit]Lyotropic liquid-crystalline phases are abundant in living systems, the study of which is referred to as lipid polymorphism. Accordingly, lyotropic liquid crystals attract particular attention in the field of biomimetic chemistry. In particular, biological membranes and cell membranes are a form of liquid crystal. Their constituent molecules (e.g. phospholipids) are perpendicular to the membrane surface, yet the membrane is flexible.[51] These lipids vary in shape (see page on lipid polymorphism). The constituent molecules can inter-mingle easily, but tend not to leave the membrane due to the high energy requirement of this process. Lipid molecules can flip from one side of the membrane to the other, this process being catalyzed by flippases and floppases (depending on the direction of movement). These liquid crystal membrane phases can also host important proteins such as receptors freely "floating" inside, or partly outside, the membrane, e.g. CTP:phosphocholine cytidylyltransferase (CCT).

Many other biological structures exhibit liquid-crystal behavior. For instance, the concentrated protein solution that is extruded by a spider to generate silk is, in fact, a liquid crystal phase. The precise ordering of molecules in silk is critical to its renowned strength. DNA and many polypeptides, including actively-driven cytoskeletal filaments,[52] can also form liquid crystal phases. Monolayers of elongated cells have also been described to exhibit liquid-crystal behavior, and the associated topological defects have been associated with biological consequences, including cell death and extrusion.[53] Together, these biological applications of liquid crystals form an important part of current academic research.

Mineral liquid crystals

[edit]Examples of liquid crystals can also be found in the mineral world, most of them being lyotropic. The first discovered was vanadium(V) oxide, by Zocher in 1925.[54] Since then, few others have been discovered and studied in detail.[55] The existence of a true nematic phase in the case of the smectite clays family was raised by Langmuir in 1938,[56] but remained an open question for a very long time and was only confirmed recently.[57][58]

With the rapid development of nanosciences, and the synthesis of many new anisotropic nanoparticles, the number of such mineral liquid crystals is increasing quickly, with, for example, carbon nanotubes and graphene. A lamellar phase was even discovered, H3Sb3P2O14, which exhibits hyperswelling up to ~250 nm for the interlamellar distance.[33]

Pattern formation in liquid crystals

[edit]Anisotropy of liquid crystals is a property not observed in other fluids. This anisotropy makes flows of liquid crystals behave more differentially than those of ordinary fluids. For example, injection of a flux of a liquid crystal between two close parallel plates (viscous fingering) causes orientation of the molecules to couple with the flow, with the resulting emergence of dendritic patterns.[59] This anisotropy is also manifested in the interfacial energy (surface tension) between different liquid crystal phases. This anisotropy determines the equilibrium shape at the coexistence temperature, and is so strong that usually facets appear. When temperature is changed one of the phases grows, forming different morphologies depending on the temperature change.[60] Since growth is controlled by heat diffusion, anisotropy in thermal conductivity favors growth in specific directions, which has also an effect on the final shape.[61]

Theoretical treatment of liquid crystals

[edit]Microscopic theoretical treatment of fluid phases can become quite complicated, owing to the high material density, meaning that strong interactions, hard-core repulsions, and many-body correlations cannot be ignored. In the case of liquid crystals, anisotropy in all of these interactions further complicates analysis. There are a number of fairly simple theories, however, that can at least predict the general behavior of the phase transitions in liquid crystal systems.

Director

[edit]As we already saw above, the nematic liquid crystals are composed of rod-like molecules with the long axes of neighboring molecules aligned approximately to one another. To describe this anisotropic structure, a dimensionless unit vector n called the director, is introduced to represent the direction of preferred orientation of molecules in the neighborhood of any point. Because there is no physical polarity along the director axis, n and -n are fully equivalent.[21]

Order parameter

[edit]

The description of liquid crystals involves an analysis of order. A second rank symmetric traceless tensor order parameter, the Q tensor is used to describe the orientational order of the most general biaxial nematic liquid crystal. However, to describe the more common case of uniaxial nematic liquid crystals, a scalar order parameter is sufficient.[62] To make this quantitative, an orientational order parameter is usually defined based on the average of the second Legendre polynomial:

where is the angle between the liquid-crystal molecular axis and the local director (which is the 'preferred direction' in a volume element of a liquid crystal sample, also representing its local optical axis). The brackets denote both a temporal and spatial average. This definition is convenient, since for a completely random and isotropic sample, S = 0, whereas for a perfectly aligned sample S=1. For a typical liquid crystal sample, S is on the order of 0.3 to 0.8, and generally decreases as the temperature is raised. In particular, a sharp drop of the order parameter to 0 is observed when the system undergoes a phase transition from an LC phase into the isotropic phase.[63] The order parameter can be measured experimentally in a number of ways; for instance, diamagnetism, birefringence, Raman scattering, NMR and EPR can be used to determine S.[24]

The order of a liquid crystal could also be characterized by using other even Legendre polynomials (all the odd polynomials average to zero since the director can point in either of two antiparallel directions). These higher-order averages are more difficult to measure, but can yield additional information about molecular ordering.[20]

A positional order parameter is also used to describe the ordering of a liquid crystal. It is characterized by the variation of the density of the center of mass of the liquid crystal molecules along a given vector. In the case of positional variation along the z-axis the density is often given by:

The complex positional order parameter is defined as and the average density. Typically only the first two terms are kept and higher order terms are ignored since most phases can be described adequately using sinusoidal functions. For a perfect nematic and for a smectic phase will take on complex values. The complex nature of this order parameter allows for many parallels between nematic to smectic phase transitions and conductor to superconductor transitions.[21]

Onsager hard-rod model

[edit]A simple model which predicts lyotropic phase transitions is the hard-rod model proposed by Lars Onsager. This theory considers the volume excluded from the center-of-mass of one idealized cylinder as it approaches another. Specifically, if the cylinders are oriented parallel to one another, there is very little volume that is excluded from the center-of-mass of the approaching cylinder (it can come quite close to the other cylinder). If, however, the cylinders are at some angle to one another, then there is a large volume surrounding the cylinder which the approaching cylinder's center-of-mass cannot enter (due to the hard-rod repulsion between the two idealized objects). Thus, this angular arrangement sees a decrease in the net positional entropy of the approaching cylinder (there are fewer states available to it).[64][65]

The fundamental insight here is that, whilst parallel arrangements of anisotropic objects lead to a decrease in orientational entropy, there is an increase in positional entropy. Thus in some case greater positional order will be entropically favorable. This theory thus predicts that a solution of rod-shaped objects will undergo a phase transition, at sufficient concentration, into a nematic phase. Although this model is conceptually helpful, its mathematical formulation makes several assumptions that limit its applicability to real systems.[65] An extension of Onsager Theory was proposed by Flory to account for non entropic effects.

Maier–Saupe mean field theory

[edit]This statistical theory, proposed by Alfred Saupe and Wilhelm Maier, includes contributions from an attractive intermolecular potential from an induced dipole moment between adjacent rod-like liquid crystal molecules. The anisotropic attraction stabilizes parallel alignment of neighboring molecules, and the theory then considers a mean-field average of the interaction. Solved self-consistently, this theory predicts thermotropic nematic-isotropic phase transitions, consistent with experiment.[66][67][68] Maier-Saupe mean field theory is extended to high molecular weight liquid crystals by incorporating the bending stiffness of the molecules and using the method of path integrals in polymer science.[69]

McMillan's model

[edit]McMillan's model, proposed by William McMillan,[70] is an extension of the Maier–Saupe mean field theory used to describe the phase transition of a liquid crystal from a nematic to a smectic A phase. It predicts that the phase transition can be either continuous or discontinuous depending on the strength of the short-range interaction between the molecules. As a result, it allows for a triple critical point where the nematic, isotropic, and smectic A phase meet. Although it predicts the existence of a triple critical point, it does not successfully predict its value. The model utilizes two order parameters that describe the orientational and positional order of the liquid crystal. The first is simply the average of the second Legendre polynomial and the second order parameter is given by:

The values zi, θi, and d are the position of the molecule, the angle between the molecular axis and director, and the layer spacing. The postulated potential energy of a single molecule is given by:

Here constant α quantifies the strength of the interaction between adjacent molecules. The potential is then used to derive the thermodynamic properties of the system assuming thermal equilibrium. It results in two self-consistency equations that must be solved numerically, the solutions of which are the three stable phases of the liquid crystal.[24]

Elastic continuum theory

[edit]In this formalism, a liquid crystal material is treated as a continuum; molecular details are entirely ignored. Rather, this theory considers perturbations to a presumed oriented sample. The distortions of the liquid crystal are commonly described by the Frank free energy density. One can identify three types of distortions that could occur in an oriented sample: (1) twists of the material, where neighboring molecules are forced to be angled with respect to one another, rather than aligned; (2) splay of the material, where bending occurs perpendicular to the director; and (3) bend of the material, where the distortion is parallel to the director and molecular axis. All three of these types of distortions incur an energy penalty. They are distortions that are induced by the boundary conditions at domain walls or the enclosing container. The response of the material can then be decomposed into terms based on the elastic constants corresponding to the three types of distortions. Elastic continuum theory is an effective tool for modeling liquid crystal devices and lipid bilayers.[71][72]

External influences on liquid crystals

[edit]Scientists and engineers are able to use liquid crystals in a variety of applications because external perturbation can cause significant changes in the macroscopic properties of the liquid crystal system. Both electric and magnetic fields can be used to induce these changes. The magnitude of the fields, as well as the speed at which the molecules align are important characteristics industry deals with. Special surface treatments can be used in liquid crystal devices to force specific orientations of the director.

Electric and magnetic field effects

[edit]The ability of the director to align along an external field is caused by the electric nature of the molecules. Permanent electric dipoles result when one end of a molecule has a net positive charge while the other end has a net negative charge. When an external electric field is applied to the liquid crystal, the dipole molecules tend to orient themselves along the direction of the field.[73]

Even if a molecule does not form a permanent dipole, it can still be influenced by an electric field. In some cases, the field produces slight re-arrangement of electrons and protons in molecules such that an induced electric dipole results. While not as strong as permanent dipoles, orientation with the external field still occurs.

The response of any system to an external electrical field is

where , and are the components of the electric field, electric displacement field and polarization density. The electric energy per volume stored in the system is

(summation over the doubly appearing index ). In nematic liquid crystals, the polarization, and electric displacement both depend linearly on the direction of the electric field. The polarization should be even in the director since liquid crystals are invariants under reflexions of . The most general form to express is

(summation over the index ) with and the electric permittivity parallel and perpendicular to the director . Then density of energy is (ignoring the constant terms that do not contribute to the dynamics of the system)[74]

(summation over ). If is positive, then the minimum of the energy is achieved when and are parallel. This means that the system will favor aligning the liquid crystal with the externally applied electric field. If is negative, then the minimum of the energy is achieved when and are perpendicular (in nematics the perpendicular orientation is degenerated, making possible the emergence of vortices[75]).

The difference is called dielectrical anisotropy and is an important parameter in liquid crystal applications. There are both and commercial liquid crystals. 5CB and E7 liquid crystal mixture are two liquid crystals commonly used. MBBA is a common liquid crystal.

The effects of magnetic fields on liquid crystal molecules are analogous to electric fields. Because magnetic fields are generated by moving electric charges, permanent magnetic dipoles are produced by electrons moving about atoms. When a magnetic field is applied, the molecules will tend to align with or against the field. Electromagnetic radiation, e.g. UV-Visible light, can influence light-responsive liquid crystals which mainly carry at least a photo-switchable unit.[76]

Surface preparations

[edit]In the absence of an external field, the director of a liquid crystal is free to point in any direction. It is possible, however, to force the director to point in a specific direction by introducing an outside agent to the system. For example, when a thin polymer coating (usually a polyimide) is spread on a glass substrate and rubbed in a single direction with a cloth, it is observed that liquid crystal molecules in contact with that surface align with the rubbing direction. The currently accepted mechanism for this is believed to be an epitaxial growth of the liquid crystal layers on the partially aligned polymer chains in the near surface layers of the polyimide.

Several liquid crystal chemicals also align to a 'command surface' which is in turn aligned by electric field of polarized light. This process is called photoalignment.

Fréedericksz transition

[edit]The competition between orientation produced by surface anchoring and by electric field effects is often exploited in liquid crystal devices. Consider the case in which liquid crystal molecules are aligned parallel to the surface and an electric field is applied perpendicular to the cell. At first, as the electric field increases in magnitude, no change in alignment occurs. However at a threshold magnitude of electric field, deformation occurs. Deformation occurs where the director changes its orientation from one molecule to the next. The occurrence of such a change from an aligned to a deformed state is called a Fréedericksz transition and can also be produced by the application of a magnetic field of sufficient strength.

The Fréedericksz transition is fundamental to the operation of many liquid crystal displays because the director orientation (and thus the properties) can be controlled easily by the application of a field.

Effect of chirality

[edit]As already described, chiral liquid-crystal molecules usually give rise to chiral mesophases. This means that the molecule must possess some form of asymmetry, usually a stereogenic center. An additional requirement is that the system not be racemic: a mixture of right- and left-handed molecules will cancel the chiral effect. Due to the cooperative nature of liquid crystal ordering, however, a small amount of chiral dopant in an otherwise achiral mesophase is often enough to select out one domain handedness, making the system overall chiral.

Chiral phases usually have a helical twisting of the molecules. If the pitch of this twist is on the order of the wavelength of visible light, then interesting optical interference effects can be observed. The chiral twisting that occurs in chiral LC phases also makes the system respond differently from right- and left-handed circularly polarized light. These materials can thus be used as polarization filters.[77]

It is possible for chiral LC molecules to produce essentially achiral mesophases. For instance, in certain ranges of concentration and molecular weight, DNA will form an achiral line hexatic phase. An interesting recent observation is of the formation of chiral mesophases from achiral LC molecules. Specifically, bent-core molecules (sometimes called banana liquid crystals) have been shown to form liquid crystal phases that are chiral.[78] In any particular sample, various domains will have opposite handedness, but within any given domain, strong chiral ordering will be present. The appearance mechanism of this macroscopic chirality is not yet entirely clear. It appears that the molecules stack in layers and orient themselves in a tilted fashion inside the layers. These liquid crystals phases may be ferroelectric or anti-ferroelectric, both of which are of interest for applications.[79][80]

Chirality can also be incorporated into a phase by adding a chiral dopant, which may not form LCs itself. Twisted-nematic or super-twisted nematic mixtures often contain a small amount of such dopants.

Applications of liquid crystals

[edit]

Liquid crystals find wide use in liquid crystal displays, which rely on the optical properties of certain liquid crystalline substances in the presence or absence of an electric field. In a typical device, a liquid crystal layer (typically 4 μm thick) sits between two polarizers that are crossed (oriented at 90° to one another). The liquid crystal alignment is chosen so that its relaxed phase is a twisted one (see Twisted nematic field effect).[8] This twisted phase reorients light that has passed through the first polarizer, allowing its transmission through the second polarizer (and reflected back to the observer if a reflector is provided). The device thus appears transparent. When an electric field is applied to the LC layer, the long molecular axes tend to align parallel to the electric field thus gradually untwisting in the center of the liquid crystal layer. In this state, the LC molecules do not reorient light, so the light polarized at the first polarizer is absorbed at the second polarizer, and the device loses transparency with increasing voltage. In this way, the electric field can be used to make a pixel switch between transparent or opaque on command. Color LCD systems use the same technique, with color filters used to generate red, green, and blue pixels.[8] Chiral smectic liquid crystals are used in ferroelectric LCDs which are fast-switching binary light modulators. Similar principles can be used to make other liquid crystal based optical devices.[81]

Liquid crystal tunable filters are used as electro-optical devices,[82][83] e.g., in hyperspectral imaging.

Thermotropic chiral LCs whose pitch varies strongly with temperature can be used as crude liquid crystal thermometers, since the color of the material will change as the pitch is changed. Liquid crystal color transitions are used on many aquarium and pool thermometers as well as on thermometers for infants or baths.[84] Other liquid crystal materials change color when stretched or stressed. Thus, liquid crystal sheets are often used in industry to look for hot spots, map heat flow, measure stress distribution patterns, and so on. Liquid crystal in fluid form is used to detect electrically generated hot spots for failure analysis in the semiconductor industry.[85]

Liquid crystal lenses converge or diverge the incident light by adjusting the refractive index of liquid crystal layer with applied voltage or temperature. Generally, the liquid crystal lenses generate a parabolic refractive index distribution by arranging molecular orientations. Therefore, a plane wave is reshaped into a parabolic wavefront by a liquid crystal lens. The focal length of liquid crystal lenses could be continuously tunable when the external electric field can be properly tuned. Liquid crystal lenses are a kind of adaptive optics. Imaging systems can benefit from focusing correction, image plane adjustment, or changing the range of depth-of-field or depth of focus. The liquid crystal lens is one of the candidates to develop vision correction devices for myopia and presbyopia (e.g., tunable eyeglass and smart contact lenses).[86][87] Being an optical phase modulator, a liquid crystal lens feature space-variant optical path length (i.e., optical path length as the function of its pupil coordinate). In different imaging system, the required function of optical path length varies from one to another. For example, to converge a plane wave into a diffraction limited spot, for a physically-planar liquid crystal structure, the refractive index of liquid crystal layer should be spherical or paraboloidal under paraxial approximation. As for projecting images or sensing objects, it may be expected to have the liquid crystal lens with aspheric distribution of optical path length across its aperture of interest. Liquid crystal lenses with electrically tunable refractive index (by addressing the different magnitude of electric field on liquid crystal layer) have potentials to achieve arbitrary function of optical path length for modulating incoming wavefront; current liquid crystal freeform optical elements were extended from liquid crystal lens with same optical mechanisms.[88] The applications of liquid crystals lenses includes pico-projectors, prescriptions lenses (eyeglasses or contact lenses), smart phone camera, augmented reality, virtual reality etc.

Liquid crystal lasers use a liquid crystal in the lasing medium as a distributed feedback mechanism instead of external mirrors. Emission at a photonic bandgap created by the periodic dielectric structure of the liquid crystal gives a low-threshold high-output device with stable monochromatic emission.[36][89]

Polymer dispersed liquid crystal (PDLC) sheets and rolls are available as adhesive backed Smart film which can be applied to windows and electrically switched between transparent and opaque to provide privacy.[90]

Many common fluids, such as soapy water, are in fact liquid crystals. Soap forms a variety of LC phases depending on its concentration in water.[91]

Liquid crystal films have revolutionized the world of technology. Currently they are used in the most diverse devices, such as digital clocks, mobile phones, calculating machines and televisions. The use of liquid crystal films in optical memory devices, with a process similar to the recording and reading of CDs and DVDs may be possible.[92][93]

Liquid crystals are also used as basic technology to imitate quantum computers, using electric fields to manipulate the orientation of the liquid crystal molecules, to store data and to encode a different value for every different degree of misalignment with other molecules.[94][95]

See also

[edit]- Biaxial nematic

- Columnar phase

- LCD classification

- Liquid-crystal display – Display that uses the light-modulating properties of liquid crystals

- Liquid crystal on silicon – Type of display technology

- Liquid-crystal polymer – Class of extremely unreactive, inert and fire-resistant polymers

- Liquid crystal tunable filter

- Lyotropic liquid crystal – Solution of amphiphilic molecules which has both fluid and crystalline properties

- Pattern formation – Study of how patterns form by self-organization in nature

- Plastic crystal

- Smart glass – Glass with electrically switchable opacity

- Thermochromism – Property of substances to change colour due to a change in temperature

- Thermotropic crystal

- Twisted nematic field effect – Type of liquid-crystal display technology

- Nematicon

- Liquid crystal thermometer

- Mood ring – Ring that contains a thermochromic element

- Active fluid

References

[edit]- ^ Bawden, F. C.; Pirie, N. W.; Bernal, J. D.; Fankuchen, I. (December 1, 1936). "Liquid Crystalline Substances from Virus-infected Plants". Nature. 138: 1051–1052. doi:10.1038/1381051a0. ISSN 0028-0836.

- ^ Reinitzer F (1888). "Beiträge zur Kenntniss des Cholesterins". Monatshefte für Chemie. 9 (1): 421–441. doi:10.1007/BF01516710. S2CID 97166902. Archived from the original on November 4, 2022. Retrieved September 8, 2021.

- ^ Lehmann O (1889). "Über fliessende Krystalle". Zeitschrift für Physikalische Chemie. 4: 462–72. doi:10.1515/zpch-1889-0434. S2CID 92908969.

- ^ a b Sluckin TJ, Dunmur DA, Stegemeyer H (2004). Crystals That Flow – classic papers from the history of liquid crystals. London: Taylor & Francis. ISBN 978-0-415-25789-3.

- ^ Gray GW (1962). Molecular Structure and the Properties of Liquid Crystals. Academic Press.

- ^ Stegemeyer H (1994). "Professor Horst Sackmann, 1921 – 1993". Liquid Crystals Today. 4: 1–2. doi:10.1080/13583149408628630.

- ^ "Liquid Crystals". King Fahd University of Petroleum & Minerals. Archived from the original on August 5, 2012.

- ^ a b c d Castellano JA (2005). Liquid Gold: The Story of Liquid Crystal Displays and the Creation of an Industry. World Scientific Publishing. ISBN 978-981-238-956-5.

- ^ US 3540796, Goldmacher JE, Castellano JA, "Electro-optical Compositions and Devices", issued November 17, 1970, assigned to RCA Corp

- ^ Heilmeier GH, Zanoni LA, Barton LA (1968). "Dynamic Scattering in Nematic Liquid Crystals". Applied Physics Letters. 13 (1): 46–47. Bibcode:1968ApPhL..13...46H. doi:10.1063/1.1652453.

- ^ Kelker H, Scheurle B (1969). "A Liquid-crystalline (Nematic) Phase with a Particularly Low Solidification Point". Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 8 (11): 884. doi:10.1002/anie.196908841.

- ^ Gray GW, Harrison KJ, Nash JA (1973). "New family of nematic liquid crystals for displays". Electronics Letters. 9 (6): 130. Bibcode:1973ElL.....9..130G. doi:10.1049/el:19730096.

- ^ Chandrasekhar S, Sadashiva BK, Suresh KA (1977). "Liquid crystals of disc-like molecules". Pramana. 9 (5): 471–480. Bibcode:1977Prama...9..471C. doi:10.1007/bf02846252. S2CID 98207805.

- ^ Collyer AA (2012). Liquid Crystal Polymers: From Structures to Applications. Springer Science & Business Media. p. 21. ISBN 978-94-011-1870-5.

The names pyramidic or bowlic were proposed, but eventually it was decided to adopt the name conic.

- ^ de Gennes PG (1992). "Soft Matter(Nobel Lecture)". Angewandte Chemie International Edition. 31 (7): 842–845. doi:10.1002/anie.199208421.

- ^ Lam L (1994). "Bowlics". In Shibaev VP, Lam L (eds.). Liquid Crystalline and Mesomorphic Polymers. Partially Ordered Systems. New York: Springer. pp. 324–353. doi:10.1007/978-1-4613-8333-8_10. ISBN 978-1-4613-8333-8.

- ^ Lei L (1987). "Bowlic Liquid Crystals". Molecular Crystals and Liquid Crystals. 146 (1): 41–54. Bibcode:1987MCLC..146...41L. doi:10.1080/00268948708071801.

- ^ "Chemical Properties of Liquid Crystals". Case Western Reserve University. Archived from the original on November 25, 2012. Retrieved June 13, 2013.

- ^ Gennes, Pierre-Gilles de (1974). The physics of liquid crystals. Oxford [Eng.] Clarendon Press. p. 2. ISBN 978-0-19-851285-1.

- ^ a b c d Chandrasekhar S (1992). Liquid Crystals (2nd ed.). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-41747-1.[permanent dead link]

- ^ a b c d e f de Gennes PG, Prost J (1993). The Physics of Liquid Crystals. Oxford: Clarendon Press. ISBN 978-0-19-852024-5.

- ^ Carroll, Gregory T.; Lee, Kyung Min; McConney, Michael E.; Hall, Harris J. (2023). "Optical control of alignment and patterning in an azobenzene liquid crystal photoresist". Journal of Materials Chemistry C. 11 (6): 2177–2185. doi:10.1039/D2TC04869H. S2CID 256151872. Archived from the original on April 20, 2023. Retrieved April 16, 2023.

- ^ a b c Dierking I (2003). Textures of Liquid Crystals. Weinheim: Wiley-VCH. ISBN 978-3-527-30725-8.

- ^ a b c d Collings PJ, Hird M (1997). Introduction to Liquid Crystals. Bristol, PA: Taylor & Francis. ISBN 978-0-7484-0643-2.

- ^ Shao Y, Zerda TW (1998). "Phase Transitions of Liquid Crystal PAA in Confined Geometries". Journal of Physical Chemistry B. 102 (18): 3387–3394. doi:10.1021/jp9734437.

- ^ Rego JA, Harvey JA, MacKinnon AL, Gatdula E (January 2010). "Asymmetric synthesis of a highly soluble 'trimeric' analogue of the chiral nematic liquid crystal twist agent Merck S1011" (PDF). Liquid Crystals. 37 (1): 37–43. doi:10.1080/02678290903359291. S2CID 95102727. Archived from the original (PDF) on October 8, 2012.

- ^ Géza T, Denniston C, Yeomans JM (February 26, 2002). "Hydrodynamics of Topological Defects in Nematic Liquid Crystals". Physical Review Letters. 88 (10) 105504. arXiv:cond-mat/0201378. Bibcode:2002PhRvL..88j5504T. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.88.105504. PMID 11909370. S2CID 38594358.

- ^ Géza T, Denniston C, Yeomans JM (May 21, 2003). "Hydrodynamics of domain growth in nematic liquid crystals". Physical Review E. 67 (5) 051705. arXiv:cond-mat/0207322. Bibcode:2003PhRvE..67e1705T. doi:10.1103/PhysRevE.67.051705. PMID 12786162. S2CID 13796254.

- ^ Madsen LA, Dingemans TJ, Nakata M, Samulski ET (April 2004). "Thermotropic biaxial nematic liquid crystals". Physical Review Letters. 92 (14) 145505. Bibcode:2004PhRvL..92n5505M. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.92.145505. PMID 15089552.

- ^ Kivelson SA, Fradkin E, Emery VJ (June 11, 1998). "Electronic liquid-crystal phases of a doped Mott insulator" (PDF). Letters to Nature. Nature. 393 (6685). Macmillan: 550–553. arXiv:cond-mat/9707327. Bibcode:1998Natur.393..550K. doi:10.1038/31177. S2CID 4392009.

- ^ Fradkin E, Kivelson SA, Lawler MJ, Eisenstein JP, Mackenzie AP (May 4, 2010). "Nematic Fermi Fluids in Condensed Matter Physics". Annual Review of Condensed Matter Physics. 1: 153–178. arXiv:0910.4166. Bibcode:2010ARCMP...1..153F. doi:10.1146/annurev-conmatphys-070909-103925. S2CID 55917078. Archived from the original on September 14, 2020. Retrieved August 5, 2022.

- ^ "smectic". Merriam-Webster Dictionary. Archived from the original on July 31, 2013. Retrieved April 26, 2013.

- ^ a b Gabriel JC, Camerel F, Lemaire BJ, Desvaux H, Davidson P, Batail P (October 2001). "Swollen liquid-crystalline lamellar phase based on extended solid-like sheets" (PDF). Nature. 413 (6855): 504–8. Bibcode:2001Natur.413..504G. doi:10.1038/35097046. PMID 11586355. S2CID 4416985. Archived (PDF) from the original on July 15, 2021. Retrieved September 8, 2021.

- ^ Davidson P, Penisson C, Constantin D, Gabriel JP (June 2018). "Isotropic, nematic, and lamellar phases in colloidal suspensions of nanosheets". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 115 (26): 6662–6667. Bibcode:2018PNAS..115.6662D. doi:10.1073/pnas.1802692115. PMC 6042086. PMID 29891691.

- ^ Vertogen, Ger; Jeu, Wim H. de (December 6, 2012). Thermotropic Liquid Crystals, Fundamentals. Springer Science & Business Media. p. 13. ISBN 978-3-642-83133-1. OCLC 851375789. Archived from the original on October 17, 2023. Retrieved March 21, 2023.

- ^ a b Kopp VI, Fan B, Vithana HK, Genack AZ (November 1998). "Low-threshold lasing at the edge of a photonic stop band in cholesteric liquid crystals". Optics Letters. 23 (21): 1707–9. Bibcode:1998OptL...23.1707K. doi:10.1364/OL.23.001707. PMID 18091891.

- ^ Priestley EB, Wojtowicz PJ, Sheng P (1974). Introduction to Liquid Crystals. Plenum Press. ISBN 978-0-306-30858-1.

- ^ Kazem-Rostami M (2019). "Optically active and photoswitchable Tröger's base analogs". New Journal of Chemistry. 43 (20): 7751–7755. doi:10.1039/C9NJ01372E. S2CID 164362391.

- ^ Kleinert H, Maki K (1981). "Lattice Textures in Cholesteric Liquid Crystals" (PDF). Fortschritte der Physik. 29 (5): 219–259. Bibcode:1981ForPh..29..219K. doi:10.1002/prop.19810290503. Archived (PDF) from the original on April 26, 2020. Retrieved October 7, 2011.

- ^ Seideman T (1990). "The liquid-crystalline blue phases" (PDF). Rep. Prog. Phys. 53 (6): 659–705. Bibcode:1990RPPh...53..659S. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.397.3141. doi:10.1088/0034-4885/53/6/001. S2CID 250776819. Archived (PDF) from the original on March 30, 2012. Retrieved October 7, 2011.

- ^ Coles HJ, Pivnenko MN (August 2005). "Liquid crystal 'blue phases' with a wide temperature range". Nature. 436 (7053): 997–1000. Bibcode:2005Natur.436..997C. doi:10.1038/nature03932. PMID 16107843. S2CID 4307675.

- ^ Yamamoto J, Nishiyama I, Inoue M, Yokoyama H (September 2005). "Optical isotropy and iridescence in a smectic 'blue phase'". Nature. 437 (7058): 525–8. Bibcode:2005Natur.437..525Y. doi:10.1038/nature04034. PMID 16177785. S2CID 4432184.

- ^ Kikuchi H, Yokota M, Hisakado Y, Yang H, Kajiyama T (September 2002). "Polymer-stabilized liquid crystal blue phases". Nature Materials. 1 (1): 64–8. Bibcode:2002NatMa...1...64K. doi:10.1038/nmat712. PMID 12618852. S2CID 31419926.

- ^ "Samsung Develops World's First 'Blue Phase' Technology to Achieve 240 Hz Driving Speed for High-Speed Video". Archived from the original on March 15, 2012. Retrieved April 23, 2009.

- ^ Otón E, Yoshida H, Morawiak P, Strzeżysz O, Kula P, Ozaki M, Piecek W (June 2020). "Orientation control of ideal blue phase photonic crystals". Scientific Reports. 10 (1): 10148. Bibcode:2020NatSR..1010148O. doi:10.1038/s41598-020-67083-6. PMC 7311397. PMID 32576875.

- ^ Wang L, Huang D, Lam L, Cheng Z (2017). "Bowlics: history, advances and applications". Liquid Crystals Today. 26 (4): 85–111. doi:10.1080/1358314X.2017.1398307. S2CID 126256863.

- ^ Liang Q, Liu P, Liu C, Jian X, Hong D, Li Y (2005). "Synthesis and Properties of Lyotropic Liquid Crystalline Copolyamides Containing Phthalazinone Moieties and Ether Linkages". Polymer. 46 (16): 6258–6265. doi:10.1016/j.polymer.2005.05.059.

- ^ Martin JD, Keary CL, Thornton TA, Novotnak MP, Knutson JW, Folmer JC (April 2006). "Metallotropic liquid crystals formed by surfactant templating of molten metal halides". Nature Materials. 5 (4): 271–5. Bibcode:2006NatMa...5..271M. doi:10.1038/nmat1610. PMID 16547520. S2CID 35833273.

- ^ a b Tomczyk W, Marzec M, Juszyńska-Gałązka E, Węgłowska D (2017). "Mesomorphic and physicochemical properties of liquid crystal mixture composed of chiral molecules with perfluorinated terminal chains". Journal of Molecular Structure. 1130: 503–510. Bibcode:2017JMoSt1130..503T. doi:10.1016/j.molstruc.2016.10.039.

- ^ Juszyńska-Gałązka E, Gałązka M, Massalska-Arodź M, Bąk A, Chłędowska K, Tomczyk W (December 2014). "Phase Behavior and Dynamics of the Liquid Crystal 4'-butyl-4-(2-methylbutoxy)azoxybenzene (4ABO5*)". The Journal of Physical Chemistry B. 118 (51): 14982–9. doi:10.1021/jp510584w. PMID 25429851.

- ^ Templer, Richard; Seddon, John (May 18, 1991). "The World of Liquid Crystals". New Scientist. Archived from the original on December 15, 2023. Retrieved December 15, 2023.

You might be surprised to find out that cell membranes are liquid crystals. In fact, the first recorded observations of the liquid crystalline phase were of myelin, the material that coats nerve fibres.

- ^ Wensink HH, Dunkel J, Heidenreich S, Drescher K, Goldstein RE, Löwen H, Yeomans JM (September 2012). "Meso-scale turbulence in living fluids". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 109 (36): 14308–13. Bibcode:2013PNAS..110.4488S. doi:10.1073/pnas.1215368110. PMC 3607014. PMID 22908244.

- ^ Saw TB, Doostmohammadi A, Nier V, Kocgozlu L, Thampi S, Toyama Y, et al. (April 2017). "Topological defects in epithelia govern cell death and extrusion". Nature. 544 (7649): 212–216. Bibcode:2017Natur.544..212S. doi:10.1038/nature21718. PMC 5439518. PMID 28406198.

- ^ Zocher H (1925). "Uber freiwillige Strukturbildung in Solen. (Eine neue Art anisotrop flqssiger Medien)". Z. Anorg. Allg. Chem. 147: 91. doi:10.1002/zaac.19251470111.

- ^ Davidson P, Gabriel JC (2003). "Mineral Liquid Crystals from Self-Assembly of Anisotropic Nanosystems". Top Curr Chem. 226: 119. doi:10.1007/b10827.

- ^ Langmuir I (1938). "The role of attractive and repulsive forces in the formation of tactoids, thixotropic gels, protein crystals and coacervates". J Chem Phys. 6 (12): 873. Bibcode:1938JChPh...6..873L. doi:10.1063/1.1750183.

- ^ Gabriel JC, Sanchez C, Davidson P (1996). "Observation of Nematic Liquid-Crystal Textures in Aqueous Gels of Smectite Clays". J. Phys. Chem. 100 (26): 11139. doi:10.1021/jp961088z.

- ^ Paineau E, Philippe AM, Antonova K, Bihannic I, Davidson P, Dozov I, et al. (2013). "Liquid–crystalline properties of aqueous suspensions of natural clay nanosheets". Liquid Crystals Reviews. 1 (2): 110. doi:10.1080/21680396.2013.842130. S2CID 136533412.

- ^ Buka A, Palffy-Muhoray P, Rácz Z (October 1987). "Viscous fingering in liquid crystals". Physical Review A. 36 (8): 3984–3989. Bibcode:1987PhRvA..36.3984B. doi:10.1103/PhysRevA.36.3984. PMID 9899337.

- ^ González-Cinca R, Ramirez-Piscina L, Casademunt J, Hernández-Machado A, Kramer L, Katona TT, et al. (1996). "Phase-field simulations and experiments of faceted growth in liquid crystal". Physica D. 99 (2–3): 359. Bibcode:1996PhyD...99..359G. doi:10.1016/S0167-2789(96)00162-5.

- ^ González-Cinca R, Ramırez-Piscina L, Casademunt J, Hernández-Machado A, Tóth-Katona T, Börzsönyi T, Buka Á (1998). "Heat diffusion anisotropy in dendritic growth: phase field simulations and experiments in liquid crystals". Journal of Crystal Growth. 193 (4): 712. Bibcode:1998JCrGr.193..712G. doi:10.1016/S0022-0248(98)00505-3.

- ^ Chaikin, P. M.; Lubensky, T. C. (1995). Principles of condensed matter physics. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. p. 168. ISBN 978-0-521-79450-3.

- ^ Ghosh SK (1984). "A model for the orientational order in liquid crystals". Il Nuovo Cimento D. 4 (3): 229. Bibcode:1984NCimD...4..229G. doi:10.1007/BF02453342. S2CID 121078315.

- ^ Onsager L (1949). "The effects of shape on the interaction of colloidal particles". Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 51 (4): 627. Bibcode:1949NYASA..51..627O. doi:10.1111/j.1749-6632.1949.tb27296.x. S2CID 84562683.

- ^ a b Vroege GJ, Lekkerkerker HN (1992). "Phase transitions in lyotropic colloidal and polymer liquid crystals" (PDF). Rep. Prog. Phys. 55 (8): 1241. Bibcode:1992RPPh...55.1241V. doi:10.1088/0034-4885/55/8/003. hdl:1874/22348. S2CID 250865818.

- ^ Maier W, Saupe A (1958). "Eine einfache molekulare theorie des nematischen kristallinflussigen zustandes". Z. Naturforsch. A (in German). 13 (7): 564. Bibcode:1958ZNatA..13..564M. doi:10.1515/zna-1958-0716. S2CID 93402217.

- ^ Maier W, Saupe A (1959). "Eine einfache molekular-statistische theorie der nematischen kristallinflussigen phase .1". Z. Naturforsch. A (in German). 14 (10): 882. Bibcode:1959ZNatA..14..882M. doi:10.1515/zna-1959-1005. S2CID 201840526.

- ^ Maier W, Saupe A (1960). "Eine einfache molekular-statistische theorie der nematischen kristallinflussigen phase .2". Z. Naturforsch. A (in German). 15 (4): 287. Bibcode:1960ZNatA..15..287M. doi:10.1515/zna-1960-0401. S2CID 97407506.

- ^ Ciferri A (1991). Liquid crystallinity in polymers: principles and fundamental properties. Weinheim: VCH Publishers. ISBN 3-527-27922-9.

- ^ McMillan W (1971). "Simple Molecular Model for the Smectic A Phase of Liquid Crystals". Phys. Rev. A. 4 (3): 1238. Bibcode:1971PhRvA...4.1238M. doi:10.1103/PhysRevA.4.1238.

- ^ Leslie FM (1992). "Continuum theory for nematic liquid crystals". Continuum Mechanics and Thermodynamics. 4 (3): 167. Bibcode:1992CMT.....4..167L. doi:10.1007/BF01130288. S2CID 120908851.

- ^ Watson MC, Brandt EG, Welch PM, Brown FL (July 2012). "Determining biomembrane bending rigidities from simulations of modest size". Physical Review Letters. 109 (2) 028102. Bibcode:2012PhRvL.109b8102W. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.109.028102. PMID 23030207.

- ^ Takezoe H (2014). "Historical Overview of Polar Liquid Crystals". Ferroelectrics. 468 (1): 1–17. Bibcode:2014Fer...468....1T. doi:10.1080/00150193.2014.932653. S2CID 120165343.

- ^ Oswald P, Pieranski P (2005). Nematic and Cholesteric Liquid Crystals: Concepts and Physical Properties Illustrated by Experiments. CRC Press. ISBN 978-0-415-32140-2. Archived from the original on May 15, 2019. Retrieved May 15, 2019.

- ^ Barboza R, Bortolozzo U, Assanto G, Vidal-Henriquez E, Clerc MG, Residori S (October 2012). "Vortex induction via anisotropy stabilized light-matter interaction". Physical Review Letters. 109 (14) 143901. Bibcode:2012PhRvL.109n3901B. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.109.143901. hdl:10533/136047. PMID 23083241.

- ^ Kazem-Rostami M (2017). "photoswitchable liquid crystal design". Synthesis. 49 (6): 1214–1222. doi:10.1055/s-0036-1588913. S2CID 99913657.

- ^ Fujikake H, Takizawa K, Aida T, Negishi T, Kobayashi M (1998). "Video camera system using liquid-crystal polarizing filter toreduce reflected light". IEEE Transactions on Broadcasting. 44 (4): 419. doi:10.1109/11.735903.

- ^ Achard MF, Bedel JP, Marcerou JP, Nguyen HT, Rouillon JC (February 2003). "Switching of banana liquid crystal mesophases under field". The European Physical Journal E. 10 (2): 129–34. Bibcode:2003EPJE...10..129A. doi:10.1140/epje/e2003-00016-y. PMID 15011066. S2CID 35942754.

- ^ Baus M, Colot JL (November 1989). "Ferroelectric nematic liquid-crystal phases of dipolar hard ellipsoids". Physical Review A. 40 (9): 5444–5446. Bibcode:1989PhRvA..40.5444B. doi:10.1103/PhysRevA.40.5444. PMID 9902823. Archived from the original on April 27, 2021. Retrieved March 4, 2021.

- ^ Uehara H, Hatano J (2002). "Pressure-Temperature Phase Diagrams of Ferroelectric Liquid Crystals". J. Phys. Soc. Jpn. 71 (2): 509. Bibcode:2002JPSJ...71..509U. doi:10.1143/JPSJ.71.509.

- ^ Alkeskjold TT, Scolari L, Noordegraaf D, Lægsgaard J, Weirich J, Wei L, Tartarini G, Bassi P, Gauza S, Wu ST, Bjarklev A (2007). "Integrating liquid crystal based optical devices in photonic crystal". Optical and Quantum Electronics. 39 (12–13): 1009. doi:10.1007/s11082-007-9139-8. S2CID 54208691.

- ^ Ciofani G, Menciassi A (2012). Piezoelectric Nanomaterials for Biomedical Applications. Springer Science & Business Media. ISBN 978-3-642-28044-3.

- ^ A.D. Chandra & A. Banerjee (2020). "Rapid phase calibration of a spatial light modulator using novel phase masks and optimization of its efficiency using an iterative algorithm". Journal of Modern Optics. 67 (7). Journal of Modern Optics, Volume 67, Issue 7, 18 May 2020: 628–637. arXiv:1811.03297. Bibcode:2020JMOp...67..628C. doi:10.1080/09500340.2020.1760954. S2CID 219646821. Archived from the original on April 10, 2022. Retrieved January 7, 2021.

- ^ US 4738549, Plimpton RG, "Pool thermometer", issued April 19, 1988

- ^ "Hot-spot detection techniques for ICs". acceleratedanalysis.com. Archived from the original on February 11, 2009. Retrieved May 5, 2009.

- ^ Sato S (1979). "Liquid-Crystal Lens-Cells with Variable Focal Length". Japanese Journal of Applied Physics. 18 (9): 1679–1684. Bibcode:1979JaJAP..18.1679S. doi:10.1143/JJAP.18.1679. S2CID 119784753.

- ^ Lin YH, Wang YJ, Reshetnyak V (2017). "Liquid crystal lenses with tunable focal length". Liquid Crystals Reviews. 5 (2): 111–143. doi:10.1080/21680396.2018.1440256. S2CID 139938136.

- ^ Wang, Yu-Jen; Lin, Yi-Hsin; Cakmakci, Ozan; Reshetnyak, Victor (2020). "Phase modulators with tunability in wavefronts and optical axes originating from anisotropic molecular tilts under symmetric electric field II: Experiments". Optics Express. 28 (6): 8985–9001. Bibcode:2020OExpr..28.8985W. doi:10.1364/OE.389647. PMID 32225513. S2CID 214734642.

- ^ Dolgaleva K, Wei SK, Lukishova SG, Chen SH, Schwertz K, Boyd RW (2008). "Enhanced laser performance of cholesteric liquid crystals doped with oligofluorene dye". Journal of the Optical Society of America. 25 (9): 1496–1504. Bibcode:2008JOSAB..25.1496D. doi:10.1364/JOSAB.25.001496.

- ^ Agarwal, Shikha; Srivastava, Swastik; Joshi, Suraj (2024). "A Comprehensive Review on Polymer-Dispersed Liquid Crystals: Mechanisms, Materials, and Applications". ACS Materials Au. doi:10.1021/acsmaterialsau.4c00122.

- ^ Luzzati V, Mustacchi H, Skoulios A (1957). "Structure of the Liquid-Crystal Phases of the Soap–water System: Middle Soap and Neat Soap". Nature. 180 (4586): 600. Bibcode:1957Natur.180..600L. doi:10.1038/180600a0. S2CID 4163714.

- ^ Silva MC, Sotomayor J, Figueirinhas J (September 2015). "Effect of an additive on the permanent memory effect of polymer dispersed liquid crystal films". Journal of Chemical Technology & Biotechnology. 90 (9): 1565–9. Bibcode:2015JCTB...90.1565S. doi:10.1002/jctb.4677.

- ^ da Silva MC, Figueirinhas JL, Sotomayor JC (January 2016). "Improvement of permanent memory effect in PDLC films using TX-100 as an additive". Liquid Crystals. 43 (1): 124–30. doi:10.1080/02678292.2015.1061713. S2CID 101996816.

- ^ Padavic-Callaghan, Karmela (August 19, 2022). "Computer made from liquid crystals would ripple with calculations". Science Advances. 8 (33) eabp8371. New Scientist. doi:10.1126/sciadv.abp8371. hdl:1721.1/145669. PMC 9390992. PMID 35984880. Archived from the original on August 24, 2022. Retrieved August 24, 2022.

- ^ "Researchers claim that ripples and imperfections in liquid crystals like those found in LCD TVs could be used to build a new type of computer". Engineering and Technology. August 22, 2022. Archived from the original on August 26, 2022. Retrieved August 24, 2022.

External links

[edit]- "History and Properties of Liquid Crystals". Nobelprize.org. Archived from the original on August 30, 2009. Retrieved June 6, 2009.

- Definitions of basic terms relating to low-molar-mass and polymer liquid crystals (IUPAC Recommendations 2001) Archived October 3, 2009, at the Wayback Machine

- An intelligible introduction to liquid crystals from Case Western Reserve University

- Liquid Crystal Physics tutorial Archived August 5, 2007, at the Wayback Machine from the Liquid Crystals Group, University of Colorado

- Liquid Crystals & Photonics Group – Ghent University (Belgium) Archived June 13, 2007, at the Wayback Machine, good tutorial

- Simulation of light propagation in liquid crystals, free program

- Liquid Crystals Interactive Online Archived March 18, 2021, at the Wayback Machine

- Liquid Crystal Institute Archived September 20, 2017, at the Wayback Machine Kent State University

- Liquid Crystals Archived January 22, 2004, at the Wayback Machine a journal by Taylor&Francis

- Molecular Crystals and Liquid Crystals a journal by Taylor & Francis

- Hot-spot detection techniques for ICs

- What are liquid crystals? from Chalmers University of Technology, Sweden

- Progress in liquid crystal chemistry Archived June 16, 2010, at the Wayback Machine Thematic series in the Open Access Beilstein Journal of Organic Chemistry

- DoITPoMS Teaching and Learning Package- "Liquid Crystals" Archived August 4, 2010, at the Wayback Machine

- Bowlic liquid crystal Archived May 18, 2015, at the Wayback Machine from San Jose State University

- Phase calibration of a Spatial Light Modulator Archived October 29, 2021, at the Wayback Machine

Liquid crystal

View on GrokipediaHistory

Early discoveries

In 1888, Austrian botanist Friedrich Reinitzer discovered the first example of liquid crystal behavior while studying cholesteryl benzoate, a derivative of cholesterol extracted from plants. Upon heating, the compound transitioned at approximately 145.5°C from a crystalline solid to a cloudy, viscous fluid that displayed birefringence—double refraction of light—and vivid, temperature-dependent color changes under polarized light. Further heating to about 178.5°C cleared the fluid into an isotropic liquid, revealing two distinct melting points rather than the typical single transition observed in ordinary substances. Puzzled by these optical anomalies, Reinitzer corresponded with physicist Otto Lehmann, marking the initial recognition of an intermediate state between solid and liquid.[10][11] Lehmann, based in Aachen, Germany, replicated Reinitzer's experiments in 1889 using polarizing microscopy, which allowed detailed visualization of the material's internal structure. He confirmed the intermediate phase's dual nature—flowing like a liquid yet scattering light anisotropically like a crystal—and coined the term "liquid crystals" (Flüssige Kristalle) to describe it, initially calling variants "flowing crystals" or "crystalline fluids." Through extensive observations of numerous organic compounds, Lehmann distinguished two primary types based on microscopic textures: a more ordered, layered form resembling soap films, which he termed "smectic" (from the Greek for soap, noting its fan-shaped and focal conic patterns), and a less ordered, fluid form showing thread-like defects, later associated with nematic behavior. These empirical classifications highlighted the phase's sensitivity to temperature and shear, laying the groundwork for understanding mesomorphic transitions.[10][12][13] In 1922, French crystallographer Georges Friedel advanced this early work by formalizing the nomenclature for these intermediate phases in a seminal review, defining "nematic" (from the Greek nēma, meaning thread) for the fluid, orientationally ordered phase with linear defects, and "smectic" for the positionally ordered, layered variants Lehmann had described. Friedel's analysis, drawing on X-ray diffraction and microscopy, emphasized the mesophases' structural analogies to soaps and threads, providing a rigorous framework that resolved ambiguities in prior observations and propelled systematic study.[10][13][14]Theoretical and experimental developments