Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Ether

View on Wikipedia

In organic chemistry, ethers are a class of compounds that contain an ether group, a single oxygen atom bonded to two separate carbon atoms, each part of an organyl group (e.g., alkyl or aryl). They have the general formula R−O−R′, where R and R′ represent the organyl groups. Ethers can again be classified into two varieties: if the organyl groups are the same on both sides of the oxygen atom, then it is a simple or symmetrical ether, whereas if they are different, the ethers are called mixed or unsymmetrical ethers.[1] A typical example of the first group is the solvent and anaesthetic diethyl ether, commonly referred to simply as "ether" (CH3−CH2−O−CH2−CH3). Ethers are common in organic chemistry and even more prevalent in biochemistry, as they are common linkages in carbohydrates and lignin.[2]

Structure and bonding

[edit]Ethers feature bent C−O−C linkages. In dimethyl ether, the bond angle is 111° and C–O distances are 141 pm.[3] The barrier to rotation about the C–O bonds is low. The bonding of oxygen in ethers, alcohols, and water is similar. In the language of valence bond theory, the hybridization at oxygen is sp3.

Oxygen is more electronegative than carbon, thus the alpha hydrogens of ethers are more acidic than those of simple hydrocarbons. They are far less acidic than alpha hydrogens of carbonyl groups (such as in ketones or aldehydes), however.

Ethers can be symmetrical of the type ROR or unsymmetrical of the type ROR'. Examples of the former are dimethyl ether, diethyl ether, dipropyl ether etc. Illustrative unsymmetrical ethers are anisole (methoxybenzene) and dimethoxyethane.

Vinyl- and acetylenic ethers

[edit]Vinyl- and acetylenic ethers are far less common than alkyl or aryl ethers. Vinylethers, often called enol ethers, are important intermediates in organic synthesis. Acetylenic ethers are especially rare. Di-tert-butoxyacetylene is the most common example of this rare class of compounds.

Nomenclature

[edit]In the IUPAC Nomenclature system, ethers are named using the general formula "alkoxyalkane", for example CH3–CH2–O–CH3 is methoxyethane. If the ether is part of a more-complex molecule, it is described as an alkoxy substituent, so –OCH3 would be considered a "methoxy-" group. The simpler alkyl radical is written in front, so CH3–O–CH2CH3 would be given as methoxy(CH3O)ethane(CH2CH3).

Trivial name

[edit]IUPAC rules are often not followed for simple ethers. The trivial names for simple ethers (i.e., those with none or few other functional groups) are a composite of the two substituents followed by "ether". For example, ethyl methyl ether (CH3OC2H5), diphenylether (C6H5OC6H5). As for other organic compounds, very common ethers acquired names before rules for nomenclature were formalized. Diethyl ether is simply called ether, but was once called sweet oil of vitriol. Methyl phenyl ether is anisole, because it was originally found in aniseed. The aromatic ethers include furans. Acetals (α-alkoxy ethers R–CH(–OR)–O–R) are another class of ethers with characteristic properties.

Polyethers

[edit]Polyethers are generally polymers containing ether linkages in their main chain. The term polyol generally refers to polyether polyols with one or more functional end-groups such as a hydroxyl group. The term "oxide" or other terms are used for high molar mass polymer when end-groups no longer affect polymer properties.

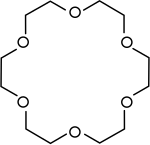

Crown ethers are cyclic polyethers. Some toxins produced by dinoflagellates such as brevetoxin and ciguatoxin are extremely large and are known as cyclic or ladder polyethers.

| Name of the polymers with low to medium molar mass | Name of the polymers with high molar mass | Preparation | Repeating unit | Examples of trade names |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Paraformaldehyde | Polyoxymethylene (POM) or polyacetal or polyformaldehyde | Step-growth polymerisation of formaldehyde | –CH2O– | Delrin from DuPont |

| Polyethylene glycol (PEG) | Polyethylene oxide (PEO) or polyoxyethylene (POE) | Ring-opening polymerization of ethylene oxide | –CH2CH2O– | Carbowax from Dow |

| Polypropylene glycol (PPG) | Polypropylene oxide (PPOX) or polyoxypropylene (POP) | anionic ring-opening polymerization of propylene oxide | –CH2CH(CH3)O– | Arcol from Covestro |

| Polytetramethylene glycol (PTMG) or Polytetramethylene ether glycol (PTMEG) | Polytetrahydrofuran (PTHF) | Acid-catalyzed ring-opening polymerization of tetrahydrofuran | −CH2CH2CH2CH2O− | Terathane from Invista and PolyTHF from BASF |

The phenyl ether polymers are a class of aromatic polyethers containing aromatic cycles in their main chain: polyphenyl ether (PPE) and poly(p-phenylene oxide) (PPO).

Related compounds

[edit]Many classes of compounds with C–O–C linkages are not considered ethers: Esters (R–C(=O)–O–R′), hemiacetals (R–CH(–OH)–O–R′), carboxylic acid anhydrides (RC(=O)–O–C(=O)R′).

There are compounds which, instead of C in the C−O−C linkage, contain heavier group 14 chemical elements (e.g., Si, Ge, Sn, Pb). Such compounds are considered ethers as well. Examples of such ethers are silyl enol ethers R3Si−O−CR=CR2 (containing the Si−O−C linkage), disiloxane H3Si−O−SiH3 (the other name of this compound is disilyl ether, containing the Si−O−Si linkage) and stannoxanes R3Sn−O−SnR3 (containing the Sn−O−Sn linkage).

Physical properties

[edit]Ethers have boiling points similar to those of the analogous alkanes. Simple ethers are generally colorless.

| Selected data about some alkyl ethers | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ether | Structure | m.p. (°C) | b.p. (°C) | Solubility in 1 liter of H2O | Dipole moment (D) |

| Dimethyl ether | CH3–O–CH3 | −138.5 | −23.0 | 70 g | 1.30 |

| Diethyl ether | CH3CH2–O–CH2CH3 | −116.3 | 34.4 | 69 g | 1.14 |

| Tetrahydrofuran | O(CH2)4 | −108.4 | 66.0 | Miscible | 1.74 |

| Dioxane | O(C2H4)2O | 11.8 | 101.3 | Miscible | 0.45 |

Reactions

[edit]

The C-O bonds that comprise simple ethers are strong. They are unreactive toward all but the strongest bases. Although generally of low chemical reactivity, they are more reactive than alkanes.

Specialized ethers such as epoxides, ketals, and acetals are unrepresentative classes of ethers and are discussed in separate articles. Important reactions are listed below.[4]

Cleavage

[edit]Although ethers resist hydrolysis, they are cleaved by hydrobromic acid and hydroiodic acid. Hydrogen chloride cleaves ethers only slowly. Methyl ethers typically afford methyl halides:

- ROCH3 + HBr → CH3Br + ROH

These reactions proceed via onium intermediates, i.e. [RO(H)CH3]+Br−.

Some ethers undergo rapid cleavage with boron tribromide (even aluminium chloride is used in some cases) to give the alkyl halide.[5] Depending on the substituents, some ethers can be cleaved with a variety of reagents, e.g. strong base.

Despite these difficulties the chemical paper pulping processes are based on cleavage of ether bonds in the lignin.

Peroxide formation

[edit]When stored in the presence of air or oxygen, ethers tend to form explosive peroxides, such as diethyl ether hydroperoxide. The reaction is accelerated by light, metal catalysts, and aldehydes. In addition to avoiding storage conditions likely to form peroxides, it is recommended, when an ether is used as a solvent, not to distill it to dryness, as any peroxides that may have formed, being less volatile than the original ether, will become concentrated in the last few drops of liquid. The presence of peroxide in old samples of ethers may be detected by shaking them with freshly prepared solution of a ferrous sulfate followed by addition of KSCN. Appearance of blood red color indicates presence of peroxides. The dangerous properties of ether peroxides are the reason that diethyl ether and other peroxide forming ethers like tetrahydrofuran (THF) or ethylene glycol dimethyl ether (1,2-dimethoxyethane) are avoided in industrial processes.

Lewis bases

[edit]

Ethers serve as Lewis bases. For instance, diethyl ether forms a complex with boron trifluoride, i.e. borane diethyl etherate (BF3·O(CH2CH3)2). Ethers also coordinate to the Mg center in Grignard reagents. Tetrahydrofuran is more basic than acyclic ethers. It forms with many complexes.

Alpha-halogenation

[edit]This reactivity is similar to the tendency of ethers with alpha hydrogen atoms to form peroxides. Reaction with chlorine produces alpha-chloroethers.

Synthesis

[edit]Dehydration of alcohols

[edit]The dehydration of alcohols affords ethers:[7]

- 2 R–OH → R–O–R + H2O at high temperature

This direct nucleophilic substitution reaction requires elevated temperatures (about 125 °C). The reaction is catalyzed by acids, usually sulfuric acid. The method is effective for generating symmetrical ethers, but not unsymmetrical ethers, since either OH can be protonated, which would give a mixture of products. Diethyl ether is produced from ethanol by this method. Cyclic ethers are readily generated by this approach. Elimination reactions compete with dehydration of the alcohol:

- R–CH2–CH2(OH) → R–CH=CH2 + H2O

The dehydration route often requires conditions incompatible with delicate molecules. Several milder methods exist to produce ethers.

Electrophilic addition of alcohols to alkenes

[edit]Alcohols add to electrophilically activated alkenes. The method is atom-economical:

- R2C=CR2 + R–OH → R2CH–C(–O–R)–R2

Acid catalysis is required for this reaction. Commercially important ethers prepared in this way are derived from isobutene or isoamylene, which protonate to give relatively stable carbocations. Using ethanol and methanol with these two alkenes, four fuel-grade ethers are produced: methyl tert-butyl ether (MTBE), methyl tert-amyl ether (TAME), ethyl tert-butyl ether (ETBE), and ethyl tert-amyl ether (TAEE).[4]

Solid acid catalysts are typically used to promote this reaction.

Epoxides

[edit]Epoxides are typically prepared by oxidation of alkenes. The most important epoxide in terms of industrial scale is ethylene oxide, which is produced by oxidation of ethylene with oxygen. Other epoxides are produced by one of two routes:

- By the oxidation of alkenes with a peroxyacid such as m-CPBA.

- By the base intramolecular nucleophilic substitution of a halohydrin.

Many ethers, ethoxylates and crown ethers, are produced from epoxides.

Williamson and Ullmann ether syntheses

[edit]Nucleophilic displacement of alkyl halides by alkoxides

- R–ONa + R′–X → R–O–R′ + NaX

This reaction, the Williamson ether synthesis, involves treatment of a parent alcohol with a strong base to form the alkoxide, followed by addition of an appropriate aliphatic compound bearing a suitable leaving group (R–X). Although popular in textbooks, the method is usually impractical on scale because it cogenerates significant waste.

Suitable leaving groups (X) include iodide, bromide, or sulfonates. This method usually does not work well for aryl halides (e.g. bromobenzene, see Ullmann condensation below). Likewise, this method only gives the best yields for primary halides. Secondary and tertiary halides are prone to undergo E2 elimination on exposure to the basic alkoxide anion used in the reaction due to steric hindrance from the large alkyl groups.

In a related reaction, alkyl halides undergo nucleophilic displacement by phenoxides. The R–X cannot be used to react with the alcohol. However phenols can be used to replace the alcohol while maintaining the alkyl halide. Since phenols are acidic, they readily react with a strong base like sodium hydroxide to form phenoxide ions. The phenoxide ion will then substitute the –X group in the alkyl halide, forming an ether with an aryl group attached to it in a reaction with an SN2 mechanism.

- C6H5OH + OH− → C6H5–O− + H2O

- C6H5–O− + R–X → C6H5OR

The Ullmann condensation is similar to the Williamson method except that the substrate is an aryl halide. Such reactions generally require a catalyst, such as copper.[8]

Important ethers

[edit]

|

Ethylene oxide | A cyclic ether. Also the simplest epoxide. |

| Dimethyl ether | A colourless gas that is used as an aerosol spray propellant. A potential renewable alternative fuel for diesel engines with a cetane rating as high as 56–57. | |

| Diethyl ether | A colourless liquid with sweet odour. A common low boiling solvent (b.p. 34.6 °C) and an early anaesthetic. Used as starting fluid for diesel engines. Also used as a refrigerant and in the manufacture of smokeless gunpowder, along with use in perfumery. | |

| Dimethoxyethane (DME) | A water miscible solvent often found in lithium batteries (b.p. 85 °C): | |

|

Dioxane | A cyclic ether and high-boiling solvent (b.p. 101.1 °C). |

|

Tetrahydrofuran (THF) | A cyclic ether, one of the most polar simple ethers that is used as a solvent. |

|

Anisole (methoxybenzene) | An aryl ether and a major constituent of the essential oil of anise seed. |

|

Crown ethers | Cyclic polyethers that are used as phase transfer catalysts. |

|

Polyethylene glycol (PEG) | A linear polyether, e.g. used in cosmetics and pharmaceuticals. |

|

Polypropylene glycol | A linear polyether, e.g. used in polyurethanes. |

|

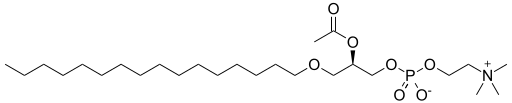

Platelet-activating factor | An ether lipid, an example with an ether on sn-1, an ester on sn-2, and an inorganic ether on sn-3 of the glyceryl scaffold. |

See also

[edit]- Ester

- Ether lipid

- Ether addiction

- History of general anesthesia

- Inhalant

- Chemical paper pulping processes: Kraft process (and Soda pulping), Organosolv pulping process and the Sulfite process

References

[edit]- ^ IUPAC, Compendium of Chemical Terminology, 5th ed. (the "Gold Book") (2025). Online version: (2006–) "ethers". doi:10.1351/goldbook.E02221

- ^ Saul Patai, ed. (1967). The Ether Linkage. PATAI'S Chemistry of Functional Groups. John Wiley & Sons. doi:10.1002/9780470771075. ISBN 978-0-470-77107-5.

- ^ Vojinović, Krunoslav; Losehand, Udo; Mitzel, Norbert W. (2004). "Dichlorosilane–Dimethyl Ether Aggregation: A New Motif in Halosilane Adduct Formation". Dalton Trans. (16): 2578–2581. doi:10.1039/b405684a. PMID 15303175.

- ^ a b Wilhelm Heitmann, Günther Strehlke, Dieter Mayer "Ethers, Aliphatic" in Ullmann's Encyclopedia of Industrial Chemistry Wiley-VCH, Weinheim, 2002. doi:10.1002/14356007.a10_023

- ^ J. F. W. McOmie and D. E. West (1973). "3,3′-Dihydroxylbiphenyl". Organic Syntheses; Collected Volumes, vol. 5, p. 412.

- ^ F.A.Cotton; S.A.Duraj; G.L.Powell; W.J.Roth (1986). "Comparative Structural Studies of the First Row Early Transition Metal(III) Chloride Tetrahydrofuran Solvates". Inorg. Chim. Acta. 113: 81. doi:10.1016/S0020-1693(00)86863-2.

- ^ Clayden; Greeves; Warren (2001). Organic chemistry. Oxford University Press. p. 129. ISBN 978-0-19-850346-0.

- ^ Frlan, Rok; Kikelj, Danijel (29 June 2006). "Recent Progress in Diaryl Ether Synthesis". Synthesis. 2006 (14): 2271–2285. doi:10.1055/s-2006-942440.

.svg/250px-Ether-(general).svg.png)

.svg/2000px-Ether-(general).svg.png)