Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Isles of Scilly

View on Wikipedia

The Isles of Scilly (/ˈsɪli/ SIL-ee; Cornish: Syllan) are a small archipelago off the southwestern tip of Cornwall. One of the islands, St Agnes, is over four miles (six kilometres) further south than the most southerly point of the British mainland at Lizard Point, and has the southernmost inhabited settlement in Cornwall, Troy Town.

Key Information

The total population of the islands at the 2021 United Kingdom census was 2,100 (rounded to the nearest 100).[6] A majority live on one island, St Mary's, and close to half live in Hugh Town; the remainder live on four inhabited "off-islands". Scilly forms part of the ceremonial county of Cornwall, and some services are combined with those of Cornwall. However, since 1890, the islands have had a separate local authority. Since the passing of the Isles of Scilly Order 1930, this authority has held the status of county council, and today it is known as the Council of the Isles of Scilly.

The adjective "Scillonian" is sometimes used for people or things related to the archipelago. The Duchy of Cornwall owns most of the freehold land on the islands. Tourism is a major part of the local economy along with agriculture, particularly the production of cut flowers.

Name

[edit]Scilly was known to the Romans as Sil(l)ina, a Latinisation of a Brittonic name represented by Cornish Sillan. The name is of unknown origin, but has been speculatively linked to the goddess Sulis.[7] The English name Scilly first appears in 1176, in the form Sully. The unetymological c was added in the 16th century in order to distinguish the name from the word "silly", whose meaning was shifting at this time from "happy" to "foolish".[8]

The islands are known in the Standard Written Form of Cornish as Syllan or Enesek Syllan.[9] In French, they are called the Sorlingues, from Old Norse Syllingar (incorporating the suffix -ingr). Mercator used this name on his 1564 map of Britain, causing it to spread to several European languages.[7]

History

[edit]| History of the British Isles |

|---|

|

Early history

[edit]

The islands may correspond to the Cassiterides ("Tin Isles"), believed by some to have been visited by the Phoenicians and mentioned by the Greeks. While Cornwall is an ancient tin-mining region,[11] there is no evidence of this having taken place substantially on the islands.[12]

During the Late Roman Empire, the islands may have been a place of exile. At least one person, one Tiberianus from Hispania, is known to have been condemned c. 385 to banishment on the isles, as well as the bishop Instantius, as part of the prosecution of the Priscillianists.[13]

The isles were off the coast of the Brittonic Celtic kingdom of Dumnonia (and its future offshoot of Kernow\, or Cornwall). Later, c. 570, when the modern Midlands—and, in 577, the Severn Valley—fell to Anglo-Saxon control, the remaining Britons were split into three separate regions: the West (Cornwall), Wales and Cumbria–Ystrad Clyd (Strathclyde).

The islands may have been a part of these polities until a short-lived conquest, by the English, in the 10th century was cut short by the Norman Conquest.[12]

It is likely that, until relatively recent times, the islands were much larger, and perhaps conjoined into one island named Ennor. Rising sea levels flooded the central plain around 400–500 AD, forming the current 55 islands and islets (if an island is defined as "land surrounded by water at high tide and supporting land vegetation").[12] The word Ennor is a contraction of the Old Cornish[14] En Noer (Doer, mutated to Noer), meaning 'the land'[14] or 'the great island'.[15]

Evidence for the older, large island includes:

- A description, written during Ancient Roman times, designates Scilly "Scillonia insula" in the singular, indicating either a single island or an island much bigger than any of the others.[16][dubious – discuss]

- Remains of a prehistoric farm have been found on Nornour (now a small, rocky skerry far too small for farming).[17][18] There once was an Iron Age British community here that continued into Roman times.[18] This community was likely formed by immigrants from Brittany—probably the Veneti—who were active in the tin trade that originated in mining activity in Cornwall and Devon.[19][20]

- At certain low tides, the sea becomes shallow enough for people to walk between some of the islands.[21] This is possibly one of the sources for stories of "drowned lands", e.g. Lyonesse.[12]

- Ancient field walls are visible below the high tideline off some of the islands, such as Samson.[22]

- Some of the Cornish-language place names also appear to reflect historical shorelines and former land areas.[23]

- The whole of southern England has been steadily sinking, in opposition to post-glacial rebound in Scotland: this has caused the rias (drowned river valleys) on the southern Cornish coast, e.g. River Fal and the Tamar Estuary.[18]

Offshore, midway between Land's End and the Isles of Scilly, is the supposed location of the mythical lost land of Lyonesse, referred to in Arthurian literature (of which Tristan is said to have been a prince). This may be a folk memory of inundated lands, but this legend is also common among the Brythonic peoples; the legend of Ys is a parallel and cognate legend in Brittany, as is that of Cantre'r Gwaelod in Wales.[12]

Norse and Norman period

[edit]

In 995, Olaf Tryggvason became King Olaf I of Norway. Born c. 960, Olaf had raided various European cities and fought in several wars. In 986 he met a Christian seer on the Isles of Scilly. He was probably a follower of Priscillian and part of the tiny Christian community that was exiled here from Spain by Emperor Maximus for Priscillianism.[citation needed] In Snorri Sturluson's Royal Sagas of Norway, it is stated that this seer told him:

Thou wilt become a renowned king, and do celebrated deeds. Many men wilt thou bring to faith and baptism, and both to thy own and others' good; and that thou mayst have no doubt of the truth of this answer, listen to these tokens. When thou comest to thy ships many of thy people will conspire against thee, and then a battle will follow in which many of thy men will fall, and thou wilt be wounded almost to death, and carried upon a shield to thy ship; yet after seven days thou shalt be well of thy wounds, and immediately thou shalt let thyself be baptised.[24]

The legend continues that, as the seer foretold, Olaf was attacked by a group of mutineers upon returning to his ships. As soon as he had recovered from his wounds, he let himself be baptised. He then stopped raiding Christian cities, and lived in England and Ireland. In 995, he used an opportunity to return to Norway. When he arrived, the Haakon Jarl was facing a revolt. Olaf Tryggvason persuaded the rebels to accept him as their king, and Jarl Haakon was murdered by his own slave, while he was hiding from the rebels in a pig sty.[citation needed]

With the Norman Conquest, the Isles of Scilly came more under centralised Norman control. About 20 years later, the Domesday survey was conducted. The islands would have formed part of the "Exeter Domesday" circuit, which included Cornwall, Devon, Dorset, Somerset, and Wiltshire.[citation needed]

In the mid-12th century, there was reportedly a Viking attack on the Isles of Scilly, called Syllingar by the Norse,[25] recorded in the Orkneyinga saga—Sweyn Asleifsson "went south, under Ireland, and seized a barge belonging to some monks in Syllingar and plundered it."[25] (Chap LXXIII)

... the three chiefs—Swein, Þorbjörn and Eirik—went out on a plundering expedition. They went first to the Suðreyar [Hebrides], and all along the west to the Syllingar, where they gained a great victory in Maríuhöfn on Columba's-mass [9 June], and took much booty. Then they returned to the Orkneys.[25]

"Maríuhöfn" literally means "Mary's Harbour/Haven". The name does not make it clear if it referred to a harbour on a larger island than today's St Mary's, or a whole island.[citation needed]

It is generally considered that Cornwall, and possibly the Isles of Scilly, came under the dominion of the English Crown for a period until the Norman conquest, late in the reign of Æthelstan (r. 924–939). In early times one group of islands was in the possession of a confederacy of hermits. King Henry I (r. 1100–1135) gave it to the abbey of Tavistock who established a priory on Tresco, which was abolished at the Reformation.[26]

Later Middle Ages and early modern period

[edit]

At the turn of the 14th century, the Abbot and convent of Tavistock Abbey petitioned the king,

stat[ing] that they hold certain isles in the sea between Cornwall and Ireland, of which the largest is called Scilly, to which ships come passing between France, Normandy, Spain, Bayonne, Gascony, Scotland, Ireland, Wales and Cornwall: and, because they feel that in the event of a war breaking out between the kings of England and France, or between any of the other places mentioned, they would not have enough power to do justice to these sailors, they ask that they might exchange these islands for lands in Devon, saving the churches on the islands appropriated to them.[27]

William le Poer, coroner of Scilly, is recorded in 1305 as being worried about the extent of wrecking in the islands, and sending a petition to the King. The names provide a wide variety of origins, e.g. Robert and Henry Sage (English), Richard de Tregenestre (Cornish), Ace de Veldre (French), Davy Gogch (possibly Welsh, or Cornish), and Adam le Fuiz Yaldicz (possibly Spanish).[citation needed]

It is not known at what point the islanders stopped speaking the Cornish language, but the language seems to have gone into decline in Cornwall beginning in the Late Middle Ages; it was still dominant between the islands and Bodmin at the time of the Reformation, but it suffered an accelerated decline thereafter. The islands appear to have lost the old Brythonic (Celtic P) language before parts of Penwith on the mainland, in contrast to its Welsh sister language. Cornish is not directly linked to Irish or Scottish Gaelic which falls into the Celtic Q group of languages.[citation needed]

During the English Civil War, the Parliamentarians captured the isles, only to see their garrison mutiny and return the isles to the Royalists. By 1651 the Royalist governor, Sir John Grenville, was using the islands as a base for privateering raids on Commonwealth and Dutch shipping. The Dutch admiral Maarten Tromp sailed to the isles and on arriving on 30 May 1651 demanded compensation. In the absence of compensation or a satisfactory reply, he declared war on England in June. It was during this period that the disputed Three Hundred and Thirty Five Years' War started between the isles and the Netherlands.[12]

In June 1651, Admiral Robert Blake recaptured the isles for the Parliamentarians. Blake's initial attack on Old Grimsby failed, but the next attacks succeeded in taking Tresco and Bryher. Blake placed a battery on Tresco to fire on St Mary's, but one of the guns exploded, killing its crew and injuring Blake. A second battery proved more successful. Subsequently, Grenville and Blake negotiated terms that permitted the Royalists to surrender honourably. The Parliamentary forces then set to fortifying the islands. They built Cromwell's Castle—a gun platform on the west side of Tresco—using materials scavenged from an earlier gun platform further up the hill. Although this poorly sited earlier platform dated back to the 1550s, it is now referred to as King Charles's Castle.[12]

The Isles of Scilly served as a place of exile during the English Civil War. Among those exiled there was Unitarian Jon Biddle.[28]

During the night of 22 October 1707, the isles were the scene of one of the worst maritime disasters in British history, when out of a fleet of 21 Royal Navy ships headed from Gibraltar to Portsmouth, six were driven onto the cliffs. Four of the ships sank or capsized, with at least 1,450 dead, including the commanding admiral Sir Cloudesley Shovell.[12]

There is evidence of inundation by the tsunami caused by the 1755 Lisbon earthquake.[29]

Geography

[edit]

The Isles of Scilly form an archipelago of five inhabited islands (six if Gugh is counted separately from St Agnes) and numerous other small rocky islets (around 140 in total) lying 45 kilometres (24+1⁄2 nautical miles) off Land's End.[30] Troy Town Farm (Troytown Farm) on the southern part of the southernmost inhabited isle, St Agnes, is the southernmost settlement of the United Kingdom.

The islands' position produces a place of great contrast; the ameliorating effect of the sea, greatly influenced by the North Atlantic Current, means they rarely have frost or snow, which allows local farmers to grow flowers well ahead of those in mainland Britain. The chief agricultural product is cut flowers, mostly daffodils. Exposure to Atlantic winds also means that spectacular winter gales lash the islands from time to time.[citation needed] This is reflected in the landscape, most clearly seen on Tresco where the lush Abbey Gardens on the sheltered southern end of the island contrast with the low heather and bare rock sculpted by the wind on the exposed northern end.[31]

Natural England has designated the Isles of Scilly as National Character Area 158.[32] As part of a 2002 marketing campaign, the plant conservation charity Plantlife chose sea thrift (Armeria maritima) as the "county flower" of the islands.[17][33]

| Island | Population (Census 2001) |

Area [citation needed] |

Density [citation needed] |

Main settlement [citation needed] | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| km2 | sq mi | per km2 | per sq mi | |||

| St Mary's | 1,666 | 6.58 | 2.54 | 253.2 | 656 | Hugh Town |

| Tresco | 180 | 2.97 | 1.15 | 60.6 | 157 | New Grimsby |

| St Martin's (with White Island) | 142 | 2.37 | 0.92 | 60.0 | 155 | Higher Town |

| St Agnes (with Gugh) | 73 | 1.48 | 0.57 | 49.3 | 128 | Middle Town |

| Bryher (with Gweal) | 92 | 1.32 | 0.51 | 70.0 | 181 | The Town |

| Samson | –(1) | 0.38 | 0.15 | - | ||

| Annet | – | 0.21 | 0.08 | - | ||

| St. Helen's | – | 0.20 | 0.08 | - | ||

| Teän | – | 0.16 | 0.06 | - | ||

| Great Ganilly | – | 0.13 | 0.05 | - | ||

| Remaining 45 islets | – | 0.57 | 0.22 | - | ||

| Isles of Scilly | 2,153 | 16.37 | 6.32 | Hugh Town | ||

(1) Inhabited until 1855.[34]

In 1975 the islands were designated as an Area of Outstanding Natural Beauty. The designation covers the entire archipelago, including the uninhabited islands and rocks, and is the smallest such area in the UK. The islands of Annet and Samson have large terneries and the islands are well populated by seals. The Isles of Scilly are the only British habitat of the lesser white-toothed shrew (Crocidura suaveolens), where it is known locally as a "teak" or "teke".[35]

Tidal influx

[edit]The tidal range at the Isles of Scilly is high for an open sea location; the maximum for St Mary's is 5.99 m (19 ft 8 in). Additionally, the inter-island waters are mostly shallow, which at spring tides allows for dry land walking between several of the islands. Many of the northern islands can be reached from Tresco, including Bryher, Samson and St Martin's (requires very low tides). From St Martin's White Island, Little Ganilly and Great Arthur are reachable. Although the sound between St Mary's and Tresco, The Road, is fairly shallow, it never becomes totally dry, but according to some sources it should be possible to wade at extreme low tides. Around St Mary's several minor islands become accessible, including Taylor's Island on the west coast and Tolls Island on the east coast. From Saint Agnes, Gugh becomes accessible at each low tide, via a tombolo.[citation needed]

Climate

[edit]The Isles of Scilly have an oceanic climate (Köppen: Cfb).[36] The average annual temperature is 12.0 °C (53.6 °F), the warmest place in the British Isles.[37] Winters are, by far, the warmest in the UK due to the moderating effects of the North Atlantic Drift of the Gulf Stream.[38][39] Despite being on exactly the same latitude as Winnipeg in Canada, snow and frost are extremely rare. The maximum snowfall was 23 cm (9 in) on 12 January 1987.[40]

The climate has mild winters and cool summers, moderated by the Atlantic Ocean, thus summer temperatures are not as warm as on the mainland. However, the Isles are one of the sunniest areas in the southwest with an average of seven hours per day in May. The lowest temperature ever recorded was −7.2 °C (19.0 °F) and the highest was 27.8 °C (82.0 °F).[41] The isles have never recorded a temperature below freezing in the months from May to November inclusive. Precipitation (the overwhelming majority of which is rain) averages about 35 in (890 mm) per year. The wettest months are from October to January, while April and May are the driest months.[42]

| Climate data for St Mary's Airport WMO ID: 03803; coordinates 49°54′52″N 6°17′45″W / 49.91451°N 6.29578°W; elevation: 10 m (33 ft); 1991–2020 averages | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 15.1 (59.2) |

15.0 (59.0) |

18.5 (65.3) |

20.8 (69.4) |

23.6 (74.5) |

26.1 (79.0) |

27.8 (82.0) |

26.8 (80.2) |

26.3 (79.3) |

24.0 (75.2) |

20.9 (69.6) |

15.3 (59.5) |

27.8 (82.0) |

| Mean daily maximum °C (°F) | 9.9 (49.8) |

10.0 (50.0) |

10.9 (51.6) |

12.6 (54.7) |

14.7 (58.5) |

17.3 (63.1) |

19.3 (66.7) |

19.7 (67.5) |

18.3 (64.9) |

15.0 (59.0) |

12.2 (54.0) |

10.6 (51.1) |

14.2 (57.6) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | 8.2 (46.8) |

8.2 (46.8) |

8.8 (47.8) |

10.1 (50.2) |

12.1 (53.8) |

14.7 (58.5) |

16.6 (61.9) |

17.0 (62.6) |

15.7 (60.3) |

12.9 (55.2) |

10.5 (50.9) |

8.9 (48.0) |

12.0 (53.6) |

| Mean daily minimum °C (°F) | 6.4 (43.5) |

6.3 (43.3) |

6.7 (44.1) |

7.5 (45.5) |

9.5 (49.1) |

12.0 (53.6) |

13.8 (56.8) |

14.3 (57.7) |

13.1 (55.6) |

10.8 (51.4) |

8.7 (47.7) |

7.1 (44.8) |

9.7 (49.4) |

| Record low °C (°F) | −7.2 (19.0) |

−4.3 (24.3) |

−1.6 (29.1) |

−0.4 (31.3) |

3.5 (38.3) |

6.8 (44.2) |

9.7 (49.5) |

8.6 (47.5) |

8.4 (47.1) |

5.5 (41.9) |

2.3 (36.1) |

−0.8 (30.6) |

−7.2 (19.0) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 93.2 (3.67) |

75.6 (2.98) |

57.4 (2.26) |

49.6 (1.95) |

47.6 (1.87) |

50.4 (1.98) |

68.5 (2.70) |

76.8 (3.02) |

71.1 (2.80) |

89.0 (3.50) |

100.0 (3.94) |

100.1 (3.94) |

879.3 (34.61) |

| Average precipitation days | 15.1 | 13.3 | 11.7 | 10.3 | 8.6 | 8.7 | 8.8 | 10.3 | 9.6 | 13.8 | 15.6 | 15.9 | 141.7 |

| Average relative humidity (%) (daily average) | 82 | 81 | 83 | 85 | 86 | 86 | 86 | 85 | 86 | 85 | 82 | 81 | 84 |

| Average dew point °C (°F) | 6 (43) |

5 (41) |

6 (43) |

7 (45) |

10 (50) |

12 (54) |

14 (57) |

14 (57) |

13 (55) |

11 (52) |

8 (46) |

6 (43) |

9 (49) |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 58.3 | 83.4 | 131.6 | 195.2 | 220.6 | 211.0 | 205.0 | 196.6 | 165.1 | 116.9 | 72.1 | 52.1 | 1,707.9 |

| Source 1: Met Office[43] | |||||||||||||

| Source 2: Time and Date (dewpoints and humidity, between 2005-2015)[44] | |||||||||||||

Geology

[edit]

All the islands of Scilly are all composed of granite rock of Early Permian age, an exposed part of the Cornubian batholith.[45][46] The Irish Sea Glacier terminated just to the north of the Isles of Scilly during the last ice age.[47][48]

Ancient monuments and historic buildings

[edit]

Historic sites on the Isles of Scilly include:[citation needed]

- Bant's Carn, a Bronze Age entrance grave

- Halangy Down Ancient Village

- Porth Hellick Down Burial Chamber

- Innisidgen Lower and Upper Burial Chambers

- The Old Blockhouse

- The St Agnes Troy Town (stone labyrinth)

- King Charles's Castle

- Harry's Walls, an unfinished artillery fort

- Garrison Tower

- Cromwell's Castle

Flora

[edit]The Isles of Scilly have been a famous location for flower farming for centuries, and in that time horticultural flora has become a mainstay of the Scillonian economy. Due to the oceanic climate found on the Isles of Scilly the isles have the unique ability to grow a multitude of plants found around the world. Perhaps the most prominently grown flower on the Isles are the scented Narcissi or Narcissus, commonly known as the daffodil. There are flower farms on the isles of St. Agnes, St. Mary's, as well as St. Martin's and Bryher. The scented Narcissi are grown October through April, scented pinks or Dianthus are the second most notably grown flower on the isles which are in full bloom from May through September. Summer time on the Isles provides the temperate conditions for the blossom of many more types of plant. Bermuda Buttercup or Oxalis pes-caprae are very often found growing in bulb fields. In early summer, Digitalis colloquially known as foxgloves grow amongst hedgerows and bramble.

Other common sprouting plants throughout the summer season include:

In saturated areas you might observe:

- Lysimachia tenella, syn. Anagallis tenella

- Mentha aquatica

- Stellaria alsine

- Triadenum

Hedgerows were planted a century ago as windbreaks to protect the crop fields and to survive battering from storms and sea spray. To thrive there, plants need sturdy roots and the ability to withstand salt and gusty winds.

A many species of exotic plants have been brought in over the years including some trees; however there are still few remaining native tree species on the Isles of Scilly: these include elm, elder, hawthorn and grey sallow.

Fauna

[edit]This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (March 2024) |

Scilly is situated far into the Atlantic Ocean, so many North American vagrant birds will make first European landfall in the archipelago. Scilly is responsible for many firsts for Britain, and is particularly good at producing vagrant American passerines. The islands are famous among birdwatchers for the large variety of rare and migratory birds that visit the islands, and when an extremely rare bird turns up, the islands see a significant increase in numbers of birders. The peak time of year for sightings is generally in the autumn.[50]

Important Bird Area

[edit]The archipelago has been designated an Important Bird Area (IBA) by BirdLife International because it supports breeding populations of several species of seabirds, including European storm-petrels, European shags, lesser and great black-backed gulls, and common terns. Ruddy turnstones visit in winter.[51]

Government

[edit]

Governors of Scilly

[edit]Historically, the Isles of Scilly were primarily ruled by a Proprietor/Governor. The governor was a military commission made by the monarch in consultation with the Admiralty in recognition of the islands' strategic position. The office of Governor was pre-eminent in military law but not in civil law, where the magistracy was vested in the Proprietor, who had a leasehold from the Duchy of Cornwall of the islands' land area. Usually the Proprietor served as Governor, although, according to Robert Heath, a Major Bennett was Governor for a short time before Proprietor Francis Godolphin, 2nd Earl of Godolphin was commissioned on 7 July 1733. The Proprietor/Governor was non-resident, delegating the military functions to a Lieutenant-Governor and the civil functions to a Council of twelve residents.[52]

An early governor of Scilly was Thomas Godolphin, whose son Francis received a lease on the Isles in 1568. The Godolphins and their Osborne relatives held this position until 1831, when George Osbourne, 6th Duke of Leeds surrendered the lease to the islands, with them then returning to direct rule from the Duchy of Cornwall. In 1834 Augustus Smith acquired the lease from the Duchy for £20,000, and created the title Lord Proprietor of the Isles of Scilly. The lease remained in his family until it expired for most of the Isles in 1920 when ownership reverted to back to the Duchy of Cornwall. Today, the Dorrien-Smith family still holds the lease for the island of Tresco.[53]

National government

[edit]Politically, the islands are part of England, one of the four countries of the United Kingdom.[54] They are represented in the UK Parliament as part of the St Ives constituency. As part of the United Kingdom, the islands were part of the European Union and were represented in the European Parliament as part of the multi-member South West England constituency.[55]

Local government

[edit]Historically, the Isles of Scilly were administered as one of the hundreds of Cornwall, although the Cornwall quarter sessions had limited jurisdiction there. For judicial purposes, shrievalty purposes, and lieutenancy purposes, the Isles of Scilly are "deemed to form part of the county of Cornwall".[56]

The Local Government Act 1888 allowed the Local Government Board to establish in the Isles of Scilly "councils and other local authorities separate from those of the county of Cornwall"... "for the application to the islands of any act touching local government." Accordingly, in 1890 the Isles of Scilly Rural District Council (the RDC) was formed as a sui generis unitary authority, outside the administrative county of Cornwall. Cornwall County Council provided some services to the Isles, for which the RDC made financial contributions. The Isles of Scilly Order 1930[57] granted the council the "powers, duties and liabilities" of a county council. Section 265 of the Local Government Act 1972 allowed for the continued existence of the RDC, but renamed as the Council of the Isles of Scilly.[58][59] This unusual status also means that much administrative law (for example relating to the functions of local authorities, the health service and other public bodies) that applies in the rest of England applies in modified form in the islands.[60]

With a total population of just over 2,000, the council represents fewer inhabitants than many English parish councils, and is by far the smallest English unitary council. As of 2015[update], 130 people are employed full-time by the council[61] to provide local services (including water supply and air traffic control). These numbers are significant, in that almost 10% of the adult population of the islands is directly linked to the council, as an employee or a councillor.[62]

The Council consists of 16 elected councillors, 12 of whom are returned by the ward of St Mary's, and one from each of four "off-island" wards (St Martin's, St Agnes, Bryher, and Tresco). The latest elections took place on 6 May 2021; all 15 councillors elected were independents.[63] One seat, for the island of Bryher, received no nominations and remained vacant until filled by a further independent councillor on 28 May.[64]

The council is headquartered at Town Hall, by The Parade park in Hugh Town, and also performs the administrative functions of the AONB Partnership[65] and the Inshore Fisheries and Conservation Authority.[66]

Some aspects of local government are shared with Cornwall, including health, and the Council of the Isles of Scilly together with Cornwall Council form a Local Enterprise Partnership. In July 2015 a devolution deal was announced by the government under which Cornwall Council and the Council of the Isles of Scilly are to create a plan to bring health and social care services together under local control. The Local Enterprise Partnership is also to be bolstered.[67]

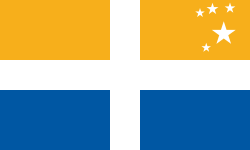

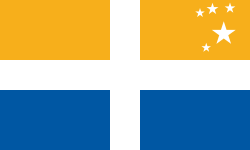

Flags

[edit]

Two flags are used to represent Scilly, The Scillonian Cross, selected by readers of Scilly News in a 2002 vote and then registered with the Flag Institute as the flag of the islands,[68][69][70] and the flag of the Council of the Isles of Scilly, which incorporates the council's logo and represents the council.[68] An adapted version of the old Board of Ordnance flag has also been used, after it was left behind when munitions were removed from the isles. The "Cornish Ensign" (the Cornish cross with the Union Jack in the canton) has also been used.[68][71]

Emergency services

[edit]The Isles of Scilly form part of the Devon and Cornwall Police force area. There is a police station in Hugh Town.[72]

The Cornwall Air Ambulance helicopter provides cover to the islands.[73]

The islands have their own independent fire brigade – the Isles of Scilly Fire and Rescue Service – which is staffed entirely by retained firefighters on all the inhabited islands.[74]

The emergency ambulance service is provided by the South Western Ambulance Service with full-time paramedics employed to cover the islands working with emergency care attendants.[75]

Administration

[edit]The Isles of Scilly altogether is a local government district, administered by a sui generis unitary authority, Council of the Isles of Scilly,[76] which is independent from Cornwall Council.

Education

[edit]

Education is available on the islands up to age 16. There is one school, the Five Islands Academy, which provides primary schooling at sites on St Agnes, St Mary's, St Martin's and Tresco, and secondary schooling at a site on St Mary's, with secondary students from outside St Mary's living at a school boarding house (Mundesley House) during the week.[77] Sixteen- to eighteen-year-olds are entitled to a free sixth form place at a state school or sixth form college on the mainland, and are provided with free flights and a grant towards accommodation.[78]

Economy

[edit]Historical context

[edit]Since the mid-18th century the Scillonian economy has relied on trade with the mainland and beyond as a means of sustaining its population. Over the years the nature of this trade has varied, due to wider economic and political factors that have seen the rise and fall of industries, such as kelp harvesting, pilotage, smuggling, fishing, shipbuilding and, latterly flower farming. In a 1987 study of the Scillonian economy, Neate found that many farms on the islands were struggling to remain profitable due to increasing costs and strong competition from overseas producers, with resulting diversification into tourism. Statistics suggest that agriculture on the islands now represents less than 2% of all employment.[79][80][81]

Tourism

[edit]

Today, tourism is estimated to account for 85% of the islands' income. The islands have been successful in attracting this investment due to their special environment, favourable summer climate, relaxed culture, efficient co-ordination of tourism providers and good transport links by sea and air to the mainland, uncommon in scale to similar-sized island communities.[82][83]

The islands' economy is highly dependent on tourism, even by the standards of other island communities. "The concentration [on] a small number of sectors is typical of most similarly sized UK island communities. However, it is the degree of concentration, which is distinctive along with the overall importance of tourism within the economy as a whole and the very limited manufacturing base that stands out".[80]

Tourism is also a highly seasonal industry owing to its reliance on outdoor recreation, and the lower number of tourists in winter results in a significant constriction of the islands' commercial activities. However, the tourist season benefits from an extended period of business in October when many birdwatchers ("twitchers") arrive.[citation needed]

Ornithology

[edit]Because of its position, Scilly is the first landing for many migrant birds, including extreme rarities from North America and Siberia. Scilly is situated far into the Atlantic Ocean, so many American vagrant birds will make first European landfall in the archipelago.[84]

If an extremely rare bird turns up, the island will see a significant increase in numbers of birdwatchers. This type of birding, chasing after rare birds, is called "twitching".[citation needed]

The islands are home to ornithologist Will Wagstaff.[citation needed]

Employment

[edit]The predominance of tourism means that "tourism is by far the main sector throughout each of the individual islands, in terms of employment... [and] this is much greater than other remote and rural areas in the United Kingdom". Tourism accounts for approximately 63% of all employment.[80]

Businesses dependent on tourism, with the exception of a few hotels, tend to be small enterprises typically employing fewer than four people; many of these are family run, suggesting an entrepreneurial culture among the local population.[80] However, much of the work generated by this, with the exception of management, is low skilled and thus poorly paid, especially for those involved in cleaning, catering and retail.[85]

Because of the seasonality of tourism, many jobs on the islands are seasonal and part-time, so work cannot be guaranteed throughout the year. Some islanders take up other temporary jobs 'out of season' to compensate for this. Due to a lack of local casual labour at peak holiday times, many of the larger employers accommodate guest workers.[citation needed]

Taxation

[edit]The islands were not subject to income tax until 1954, and there was no motor vehicle excise duty levied until 1971.[86] The Council Tax is set by the Local Authority in order to meet their budget requirements. The Valuation Office Agency values properties for the purpose of council tax.[87] The amount of council tax paid depends on the band of the property as shown below. The valuation is based on what the property would have been worth in 1991.[87]

| Band | Property Valuation | Average Tax |

|---|---|---|

| A | ≤ £40,000 | £1,087 |

| B | £40,001 - £52,000 | £1,268 |

| C | £52,001 - £68,000 | £1,450 |

| D | £68,001 - £88,000 | £1,631 |

| E | £88,001 - £120,000 | £1,993 |

| F | £120,001 - £160,000 | £2,356 |

| G | £160,001 - £320,000 | £2,718 |

| H | > £320,000 | £3,262 |

Source 1: Council of the Isles of Scilly

Source 2: Isles of Scilly Council Tax

Transport

[edit]

St Mary's is the only island with a significant road network and the only island with classified roads - the A3110, A3111 and A3112. St Agnes and St Martin's also have public highways adopted by the local authority.[88] In 2005 there were 619 registered vehicles on the island. The island also has taxis and a tour bus. Vehicles on the islands are exempt from annual MOT tests.[89][90]

Fixed-wing aircraft services, operated by Isles of Scilly Skybus, operate from Land's End, Newquay and Exeter to St Mary's Airport.[91] A scheduled helicopter service has operated from a new Penzance Heliport to both St Mary's Airport and Tresco Heliport since 2020. The helicopter is the only direct flight to the island of Tresco.[92]

By sea, the Isles of Scilly Steamship Company provides a passenger and cargo service from Penzance to St Mary's, which is currently operated by the Scillonian III passenger ferry, supported until summer 2017 by the Gry Maritha cargo vessel and now by the Mali Rose. The other islands are linked to St. Mary's by a network of inter-island launches.[93] St Mary's Harbour is the principal harbour of the Isles of Scilly, and is located in Hugh Town.[94]

Tenure

[edit]A majority of the freehold land of the islands is the property of the Duchy of Cornwall, with a few exceptions, including much of Hugh Town on St Mary's, which was sold to the inhabitants in 1949. The duchy also holds 3,921 acres (1,587 hectares) as duchy property, part of the duchy's landholding.[95] All the uninhabited islands, islets and rocks and much of the untenanted land on the inhabited islands is managed by the Isles of Scilly Wildlife Trust, which leases these lands from the Duchy for the rent of one daffodil per year.[96]

Limited housing availability is a contentious yet critical issue for the Isles of Scilly, especially as it affects the feasibility of residency on the islands. Few properties are privately owned, with many units being let by the Duchy of Cornwall, the council and a few by housing associations. The management of these subsequently affects the possibility of residency on the islands.[97]

Housing demand outstrips supply, a problem compounded by restrictions on further development designed to protect the islands' unique environment and prevent the infrastructural carrying capacity from being exceeded. This has pushed up the prices of the few private properties that become available and, significantly for the majority of the islands' populations, it has also affected the rental sector where rates have likewise drastically increased.[98][99]

High housing costs pose significant problems for the local population, especially as local incomes (in Cornwall) are only 70% of the national average, whilst house prices are almost £5,000 higher than the national average. This in turn affects the retention of 'key workers' and the younger generation, which consequently affects the viability of schools and other essential community services.[82][99]

The limited access to housing provokes strong local politics. It is often assumed that tourism is to blame for this, attracting newcomers to the area who can afford to outbid locals for available housing. Many buildings are used for tourist accommodation which reduces the number available for local residents. Second homes are also thought to account for a significant proportion of the housing stock, leaving many buildings empty for much of the year.[100]

In December 2021, the Council bought a property to ease the housing crisis, which would be converted into 3 affordable homes.[101] The council also, in January 2022, declared a housing crisis, due to the housing crisis placing the islands in "real danger of putting essential services at risk, such as the hospital and school". The council also highlighted that 15 households would be homeless by March and would face having to move from the Islands.[102]

Utilities

[edit]Starting in the 1960s, a public electricity supply was provided on St Mary's by installing successive diesel generators in a power station on the island, eventually totalling 5 MW. Other islands had no public electricity supply and consumers generated their own electricity.[103] In 1985–86, 11 kV submarine cables were installed to connect St Agnes, Tresco, St Martin's and Bryher to St Mary's, and in 1988-89 the islands were connected to the mainland by a 33 kV submarine cable of 7.5 MW capacity running from Whitesand Bay near Land's End to Porthcressa Bay on St Mary's.[104] The power station is maintained but is now used only when the cable is unavailable. There are also 200 kVA generators on Bryher and St Agnes for use when the inter-island cables are unavailable.[103]

Water comes from boreholes and, on St Mary's, a desalination plant at Mount Todden providing 40-50% of demand,[105] with only a small amount of surface water collection.[103]

On St Mary's, Hugh Town and Old Town have piped foul drainage systems, discharging the eventual effluent into the sea. Tresco has a sewage treatment plant. All other properties have septic tanks.[103]

Notable people

[edit]- John Godolphin (1617–1678), an English jurist and writer, and Judge of the High Court of Admiralty.[106]

- Sam Llewellyn (born 1948 in Tresco), a British author of literature for children and adults.

Culture

[edit]People

[edit]According to the 2001 UK census, 97% of the population of the islands are white British,[4] with nearly 93% of the inhabitants born in the islands, in mainland Cornwall or elsewhere in England.[107] Following EU enlargement in 2004, a number of central Europeans moved to the island, joining the Australians, New Zealanders and South Africans who traditionally made up most of the islands' overseas workers. In 2005, their numbers were estimated at nearly 100 out of a total population of just over 2,000.[108] The Isles have also been referred to as "the land that crime forgot", reflecting lower crime levels than national averages.[109]

Sport

[edit]One continuing legacy of the isles' past is gig racing, wherein fast rowing boats ("gigs") with crews of six (or in one case, seven) race between the main islands. Gig racing has been said to derive from the race to collect salvage from shipwrecks on the rocks around Scilly, but the race was actually to deliver a pilot onto incoming vessels, to guide them through the hazardous reefs and shallows. (The boats are correctly termed "pilot gigs"). The World Pilot Gig Championships are held annually over the May Day bank holiday weekend. The event originally involved crews from the Islands and a few crews from mainland Cornwall, but in the intervening years the number of gigs attending has increased, with crews coming from all over the South-West and further afield.[110]

The Isles of Scilly is home to what is reportedly the smallest football league in the world, the Isles of Scilly Football League.[111]

In December 2006, Sport England published a survey which revealed that residents of the Isles of Scilly were the most active in England in sports and other fitness activities. 32% of the population participate at least three times a week for 30 minutes or more.[112]

There is a golf club with a nine-hole course (each with two tees) situated on the island of St Mary's, near Porthloo and Telegraph, which was founded in 1904.[113]

Media

[edit]The islands are served by the Halangy Down radio and television transmitter on St Mary's north of Telegraph at 49°55′57″N 6°18′19″W / 49.932505°N 6.305358°W. It is a relay of the main transmitter at Redruth (Cornwall) that broadcasts BBC South West, ITV West Country, BBC Radio 1, 2, 3, 4 and BBC Radio Cornwall and the range of Freeview television and BBC radio channels on the public service broadcast multiplexes. Radio Scilly, a community radio station, was launched in September 2007. In January 2020, Radio Scilly was rebranded as Islands FM.[114][115]

The Isles of Scilly were featured on the TV programme Seven Natural Wonders as one of the wonders of South West England. Since 2007 the islands have featured in the BBC series An Island Parish, following various real-life stories and featuring in particular the newly appointed Chaplain to the Isles of Scilly. A 12-part series was filmed in 2007 and first broadcast on BBC2 in January 2008.[116] After Reverend David Easton left the islands in 2009, the series continued under the same name but focused elsewhere.[117]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ "New appointments for Councillors 2019 | Council of the ISLES OF SCILLY". scilly.gov.uk. Retrieved 10 February 2023.

- ^ "Mark Boden appointed Interim Chief Executive | Council of the ISLES OF SCILLY". scilly.gov.uk.

- ^ "Mid-Year Population Estimates, United Kingdom, June 2024". Office for National Statistics. 26 September 2025. Retrieved 26 September 2025.

- ^ a b "Isles of Scilly ethnic groups". Office for National Statistics. Archived from the original on 28 July 2013. Retrieved 6 December 2012.

- ^ "Isles of Scilly". Ramsar Sites Information Service. Retrieved 25 April 2018.

- ^ "Build a custom area profile - Census 2021, ONS". www.ons.gov.uk. Retrieved 27 March 2024.

- ^ a b Rivet, A. L. F.; Smith, Colin (1979). The Place-Names of Roman Britain. Princeton University Press. pp. 457–459. ISBN 0-691-03953-4.

- ^ Watts, Victor, ed. (2010). The Cambridge Dictionary of English Place-Names. Cambridge University Press. p. 531. ISBN 978-0-521-16855-7.

- ^ "Scilly". Gerlyver Kernewek: Cornish Dictionary. Akademi Kernewek. Retrieved 9 April 2025.

- ^ Barnett, Robert L.; Charman, Dan J.; Johns, Charles; Ward, Sophie L.; Bevan, Andrew; Bradley, Sarah L.; Camidge, Kevin; Fyfe, Ralph M.; Gehrels, W. Roland; Gehrels, Maria J.; Hatton, Jackie; Khan, Nicole S.; Marshall, Peter; Maezumi, S. Yoshi; Mills, Steve; Mulville, Jacqui; Perez, Marta; Roberts, Helen M.; Scourse, James D.; Shepherd, Francis; Stevens, Todd (4 November 2020). "Nonlinear landscape and cultural response to sea-level rise". Science Advances. 6 (45) eabb6376. doi:10.1126/sciadv.abb6376. PMC 7673675. PMID 33148641.

- ^ Champion, Timothy (2001). "The appropriation of the Phoenicians in British imperial ideology". Nations and Nationalism. 7 (4): 451–465. doi:10.1111/1469-8219.00027.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Bowley, Rex Lyon; Bowley, Ernest Lyon (2004). The Fortunate Islands: The Story of the Isles of Scilly (ninth ed.). St. Mary's, Isles of Scilly: Bowley Publications. ISBN 978-0-900184-40-6. Originally written by Ernest Lyon Bowley and published in 1945 by W. P. Kennedy.

- ^ Chadwick, Henry (1976). Priscillian of Avila. Oxford: Oxford University Press. pp. 144–145. ISBN 9780198266433.

- ^ a b Duncan, Steve (1 January 2000). "Scillonian Dictionary". Retrieved 23 December 2016.

- ^ Thomas, Charles (1985). Exploration of a Drowned Landscape: Archaeology and History of the Isles of Scilly. London: Batsford. ISBN 978-0-7134-4852-8 – via Google Books.

- ^ Duck, R.W. (2011). This shrinking land: climate change and Britain's coasts. Dundee: Dundee University. p. 14. ISBN 978-1-4744-6785-8. OCLC 1145888878.

- ^ a b Thorgrim (14 December 2003). "Nornour". The Megalithic Portal. Retrieved 5 May 2021.

- ^ a b c Dudley, Dorothy (1967). "Excavations on Nor'Nour in the Isles of Scilly, 1962–6". The Archaeological Journal. CXXIV; includes a description of over 250 Roman fibulae found at the site.

- ^ Weatherhill, Craig. "IKTIS – The Ancient Cornish Tin Trade". Retrieved 1 June 2024.

- ^ "The Rumps & The Veneti Refugees who Settled in Cornwall". The Cornish Bird. 21 January 2023. Retrieved 1 June 2024.

- ^ "Scilly's Unique Inter Island Walk Sets Off This Morning". Scilly Today. 22 August 2013. Retrieved 9 June 2015.

- ^ Dillon, Paddy (2015). Walking in the Isles of Scilly. Cicerone. p. 67.

- ^ Weatherhill, Craig (2007). Cornish Placenames and Language. Wilmslow, UK: Sigma Leisure.

- ^ Sturlason, Snorri (1225). "King Olaf Trygvason's Saga". Heimskringla (in Old Norse).

- ^ a b c Anderson, Joseph, ed. (1990) [1893]. Orkneyinga saga. Translated by Hjaltalin, Jón A.; Goudie, Gilbert (reprint ed.). Edinburgh: James Thin and Mercat Press. ISBN 9780901824257.

- ^ Henderson, Charles (1925). The Cornish Church Guide. Truro: Oscar Blackford. p. 194.

- ^ "Petitioners: Abbot and convent of Tavistock. Addressees: King and council". The National Archives. Retrieved 25 November 2014.

- ^ Worden, Blair (2012). God's Instruments: Political Conduct in the England of Oliver Cromwell. Oxford University Press. pp. 79–81. ISBN 9780199570492.

- ^ Banerjee, D.; et al. (1 December 2001). "Scilly Isles, UK: optical dating of a possible tsunami deposit from the 1755 Lisbon earthquake". Quaternary Science Reviews. 20 (5–9): 715–718. Bibcode:2001QSRv...20..715B. doi:10.1016/s0277-3791(00)00042-1. Retrieved 30 March 2015.

- ^ Scheffel, Richard L.; Wernet, Susan J., eds. (1980). Natural Wonders of the World. United States of America: Reader's Digest Association, Inc. p. 340. ISBN 978-0-89577-087-5.

- ^ Mumford, Clive (1980). Portrait of the Isles of Scilly (3rd ed.). London: Robert Hale. pp. 188–189. ISBN 0-7091-1718-3. OCLC 859198.

- ^ "NCA 158: Isles of Scilly Key Facts & Data" (PDF). www.naturalengland.org.uk. Retrieved 8 September 2013.

- ^ "County flower of Isles of Scilly". Plantlife International – The Wild Plant Conservation Charity. Archived from the original on 18 March 2007. Retrieved 7 April 2006.

- ^ Bowley, R. L. (2004). The Fortunate Islands: The story of the Isles of Scilly (9th ed.). St Mary's, Isles of Scilly: Bowley Publications. p. 96. ISBN 0-900184-40-X. OCLC 60559326.

- ^ Robinson, H.W. (1925). "A New British Animal Discovered in Scilly". Scillonian. No. 4. pp. 123–124.

- ^ Millison, Andrew (1 August 2019). "Appendix D: Koppen-Trewartha Climate Classification Descriptions". Oregon State University.

- ^ Hickman, Leo (10 April 2011). "Isles of Scilly turn heat on Jersey over 'warmest place in Britain' claim". The Guardian.

The Met Office officially recognises Scilly as the warmest place in the UK.

- ^ Killingley, Eileen (2011). "Bromeliads of Tresco Abbey Garden, Isles of Scilly, Cornwall, England". Journal of the Bromeliad Society. 61 (6): 268–276.

While the Scillies do have the warming influence of the Gulf Stream they are also subject to cold winter gales.

- ^ Cooper, Leslie H. N. (1961). "The oceanography of the Celtic Sea. I. Wind drift" (PDF). Journal of the Marine Biological Association of the United Kingdom. 41 (2): 223–233. Bibcode:1961JMBUK..41..223C. doi:10.1017/S0025315400023870. S2CID 86325502.

- ^ "Fact Sheet – South West England" (PDF). Met Office. p. 17. Archived from the original (PDF) on 24 May 2014.

- ^ "Extreme Temperatures Around the World: world highest lowest recorded temperatures". Maximiliano Herrera.

- ^ "St Mary's Heliport (Isles of Scilly) Location-specific long-term averages - Met Office". www.metoffice.gov.uk. Retrieved 21 August 2025.

- ^ "St Mary's Heliport Climatic Averages 1991-2020". Met Office. December 2021. Retrieved 16 December 2021.

- ^ "Climate & Weather Averages in Hugh Town, United Kingdom". Time and Date. Retrieved 16 January 2022.

- ^ Barrow, George (1906). The Geology of the Isles of Scilly. Memoirs of the Geological Survey of Great Britain. England and Wales (New Series) No. 357. HM Stationery Office.

- ^ Darbyshire, D. P. Fiona; Shepherd, Thomas J. (1994). "Nd and Sr isotope constraints on the origin of the Cornubian batholith, SW England". Journal of the Geological Society. 151 (5): 795. Bibcode:1994JGSoc.151..795D. doi:10.1144/gsjgs.151.5.0795. S2CID 128417340.

- ^ Hiemstra, John F.; et al. (February 2006). "New evidence for a grounded Irish Sea glaciation of the Isles of Scilly, UK". Quaternary Science Reviews. 25 (3–4): 299–309. Bibcode:2006QSRv...25..299H. doi:10.1016/j.quascirev.2005.01.013. hdl:1885/20102. S2CID 131144622. Retrieved 29 March 2015.

- ^ Scourse, James D. (1991). "Late Pleistocene Stratigraphy and Palaeobotany of the Isles of Scilly". Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London. Series B: Biological Sciences. 334 (1271): 405–448. Bibcode:1991RSPTB.334..405S. doi:10.1098/rstb.1991.0125. Retrieved 29 March 2015.

- ^ O'Neil, B.H.St.J. (1949). Ancient Monuments of the Isles of Scilly. Ministry of Works Official Guide-book. Her Majesty's Stationery Office (HMSO). OCLC 561729732.

- ^ "Birdwatching - The Isles of Scilly". Cornwall Guide. 2 March 2016. Retrieved 22 May 2022.

- ^ "Isles of Scilly". BirdLife Data Zone. BirdLife International. 2024. Retrieved 28 August 2024.

- ^ Woodley, George (1822). "Of the Civil, Military, and Ecclesiastical Government of the Scilly Islands". A View of the Present State of the Scilly Islands. London: F. C. and J. Rivington; Longman; Carthew, County Library, Truro. pp. 93–104.

- ^ Bowley, R. L. (2004). The Fortunate Islands (9th ed.). St Mary's, Isles of Scilly: Bowley Publications. ISBN 0-900184-40-X.

- ^ "Interpretation Act 1978: Schedule 1", legislation.gov.uk, The National Archives, 1978 c. 30 (sch. 1), retrieved 16 February 2024,

"England" means, subject to any alteration of boundaries under Part IV of the Local Government Act 1972, the area consisting of the counties established by section 1 of that Act, Greater London and the Isles of Scilly. [1st April 1974].

- ^ "Your MP and MEPs | Council of the ISLES OF SCILLY". scilly.gov.uk. Retrieved 29 January 2023.

- ^ Local Government Act 1972 (1972 c.70) section 216(2)

- ^ "Isles of Scilly Order 1930" (PDF). The National Archives.

- ^ "Isles of Scilly Cornwall through time". visionofbritain.org.uk. Retrieved 19 January 2007.

- ^ "Isles of Scilly RD Cornwall through time". visionofbritain.org.uk. Archived from the original on 6 May 2007. Retrieved 19 January 2007.

- ^ Examples include the Health and Social Care Act 2003, section 198 and the Environment Act 1995, section 117.

- ^ Leijser, Theo (2015) Scilly Now & Then no. 77 p. 35

- ^ "Council of the Isles of Scilly Corporate Assessment December 2002" (PDF). Audit Commission. Retrieved 21 January 2007.

- ^ "Elections | Council of the ISLES OF SCILLY". www.scilly.gov.uk. Retrieved 10 February 2023.

- ^ "Councillors and Committees | Council of the ISLES OF SCILLY". committees.scilly.gov.uk. Retrieved 10 February 2023.

- ^ "Welcome to the Isles of Scilly Area of Outstanding Natural Beauty (AONB)". Isles of Scilly Area of Outstanding Natural Beauty (AONB). Archived from the original on 20 March 2013. Retrieved 9 June 2015.

- ^ "Welcome to the Isles of Scilly Inshore Fisheries and Conservation Authority". Isles of Scilly IFCA.

- ^ "Cornwall devolution: First county with new powers". BBC News Online. 16 July 2015. Retrieved 27 August 2015.

- ^ a b c "Isles of Scilly (United Kingdom)". fotw.net. Retrieved 16 January 2007.

- ^ "How Do You Get A Scillonian Cross". Scilly Archive. Archived from the original on 11 April 2013. Retrieved 16 January 2007.

- ^ "Isles of Scilly – The Flag Institute". The Flag Institute. Retrieved 25 July 2017.

- ^ "Cornwall (United Kingdom)". fotw.net. Archived from the original on 17 January 2007. Retrieved 16 January 2007.

- ^ Taylor, Colin (2017). The life of a Scilly sergeant. London: Arrow Books. ISBN 978-1-78475-515-7. OCLC 974938409.

- ^ Busy week for Cornwall Air Ambulance Scilly Today

- ^ "Fire & Rescue | Council of the ISLES OF SCILLY". scilly.gov.uk. Retrieved 9 January 2022.

- ^ "Welcome to SWASFT -". www.swast.nhs.uk. Retrieved 9 January 2022.

- ^ "Welcome to Council of the ISLES OF SCILLY | Council of the ISLES OF SCILLY". www.scilly.gov.uk. Retrieved 3 February 2025.

- ^ "Welcome to The Five Islands Academy | Five Islands Academy". www.fiveislands.scilly.sch.uk. Archived from the original on 9 January 2022. Retrieved 9 January 2022.

- ^ "Schools & Colleges | Council of the ISLES OF SCILLY". www.scilly.gov.uk. Retrieved 9 January 2022.

- ^ Gibson, F, My Scillionian Home... its past, its present, its future, St Ives, 1980

- ^ a b c d Isles of Scilly Integrated Area Plan 2001–2004, Isles of Scilly Partnership 2001

- ^ Neate, S, The role of tourism in sustaining farm structures and communities on the Isles of Scilly in M Bouquet and M Winter (eds) Who From Their Labours Rest? Conflict and practice in rural tourism Aldershot, 1987

- ^ a b Isles of Scilly Local Plan: A 2020 Vision, Council of the Isles of Scilly, 2004

- ^ Isles of Scilly 2004, imagine..., Isles of Scilly Tourist Board, 2004

- ^ Bowley, Rex Lyon (2006). The Scilly guidebook : Isles of Scilly standard guidebook (56th ed.). Isles of Scilly: Bowley Publications. pp. 44–49. ISBN 978-0-900184-44-4. OCLC 1158345082.

- ^ J.Urry, The Tourist Gaze (2nd edition), London, 2002

- ^ "Travel: Living in a world of their own: On the shortest day of the year, Simon Calder took the high road to Shetland and Frank Barrett took the low road to the Scillies, as Britain's extremities made ready for Christmas". The Independent. London. 24 December 1993.

- ^ a b "Council Tax | Council of the ISLES OF SCILLY". www.scilly.gov.uk. Retrieved 24 May 2022.

- ^ Ordnance Survey. OS Maps Online (Map). 1:25,000. Leisure. Retrieved 9 February 2022.

- ^ Motor Vehicles (tests) Regulations 1981 (SI 1981/1694)

- ^ "A Sustainable Energy Strategy for the Isles of Scilly" (PDF). Council of the Isles of Scilly. November 2007. pp. 13, 21. Archived from the original (PDF) on 18 January 2012. Retrieved 21 August 2010.

- ^ "Skybus Timetables". Skybus. Archived from the original on 16 November 2013. Retrieved 8 September 2014.

- ^ "Home | Penzance Helicopters". penzancehelicopters.co.uk. Retrieved 26 January 2021.

- ^ "Isles of Scilly Travel – Travel by sea". Isles of Scilly Travel. Retrieved 17 January 2007.

- ^ Mumford, Clive (1980). Portrait of the Isles of Scilly (3rd ed.). Robert Hale. p. 138. ISBN 0-7091-1718-3.

- ^ Sandy Mitchell (May 2006). "Prince Charles not your typical radical". National Geographic. National Geographic Society. pp. 96–115, map ref 104. Archived from the original on 6 August 2007. Retrieved 26 September 2010.

- ^ "Isles of Scilly". Duchy of Cornwall. Retrieved 8 June 2017.

In particular, The Isles of Scilly Wildlife Trust, which manages around 60 per cent of the area of the Isles, including the uninhabited islands, plays an important role in protecting wildlife and their habitats. The Trust pays a rent to the Duchy of one daffodil per year!

- ^ Martin D, 'Heaven and Hell', in Inside Housing, 31 October 2004

- ^ Sub Regional Housing Markets in the South West, South West Housing Board, 2004

- ^ a b S. Fleming et al., "In from the cold" A report on Cornwall’s Affordable Housing Crisis, Liberal Democrats, Penzance, 2003

- ^ The Cornishman, "Islanders in dispute with Duchy over housing policy", 19 August 2004

- ^ "Scilly Isles council buys house to tackle housing crisis". BBC News. 4 December 2021. Retrieved 20 January 2022.

- ^ "The Council of the Isles of Scilly declares housing crisis". BBC News. 20 January 2022. Retrieved 20 January 2022.

- ^ a b c d Energy Infrastructure Plan for the Isles of Scilly Smart Islands. Report for the Council of the Isles of Scilly. Funded by the Local Enterprise Partnership. Submitted by Hitachi Europe Ltd. Final version dated 12 May 2016. https://www.scilly.gov.uk/sites/default/files/IoS_Infrastructure%20Plan_FINAL_IoS.pdf

- ^ Isles of Scilly Electrification. August 2011.https://wpehs.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2020/04/Sup048IoSElectrification.pdf

- ^ South West Water. Draft Drought Plan: Isles of Scilly. September 2022. https://www.southwestwater.co.uk/siteassets/documents/environment/drought-plan/isles-of-scilly-draft-drought-plan-september-2022.pdf

- ^ . Dictionary of National Biography. Vol. 22. 1890. p. 41.

- ^ "Isles of Scilly – Country of Birth". Office for National Statistics. Archived from the original on 19 November 2015. Retrieved 6 December 2012.

- ^ "East Europeans in the Isles of Scilly". The Guardian. 23 January 2006. Retrieved 6 December 2012.

- ^ Mawby, R.I. (2002). "The Land that Crime Forgot? Auditing the Isles of Scilly". Crime Prevention and Community Safety. 4 (2): 39–53. doi:10.1057/palgrave.cpcs.8140122. S2CID 159581320. Retrieved 29 March 2015.

- ^ Rick Persich; Chairman World Pilot Gigs Championships Committee. "World Pilot Gig Championships – Isles of Scilly". Archived from the original on 23 April 2010. Retrieved 26 September 2010.

- ^ Smith, Rory (22 December 2016). "Welcome to the World's Smallest Soccer League. Both Teams Are Here". The New York Times.

- ^ "Active People Survey – national factsheet appendix". Sport England. Archived from the original (Microsoft Excel) on 15 March 2007. Retrieved 16 January 2007.

- ^ "Isles of Scilly Golf Club". Archived from the original on 31 May 2015. Retrieved 9 June 2015.

- ^ "Community station Radio Scilly rebrands to Islands FM". Community Ragio Today. 25 June 2020. Archived from the original on 3 April 2021.

- ^ "About Islands FM". Islands FM 107.9. Archived from the original on 10 August 2020.

- ^ "An Island Parish". BBC. Retrieved 16 January 2007.

- ^ "Former Methodist Minister Returns For Visit". The Scillonian. 8 July 2015. Retrieved 11 August 2016.

Further reading

[edit]- Woodley, George (1822). A View of the Present State of the Scilly Islands: exhibiting their vast importance to the British empire, the improvements of which they are susceptible, and a particular account of the means lately adopted for the amelioration of the condition of the inhabitants, by the establishment and extension of their fisheries. London: Rivington.

- O'Neil, B. H. St. J. (1949). Ancient Monuments of the Isles of Scilly. Ministry of Works Official Guide-book. His Majesty's Stationery Office (HMSO). OCLC 561729732.

- Isles of Scilly Guidebook by Friendly Guides (2021) ISBN 978-1-904645-34-4

- A Study of the Historic Coastal and Marine Environment of the Isles of Scilly. Cornwall Archaeological Unit, Cornwall Council, ed. by D. Charman et al. (Truro: Cornwall Archaeological Unit, Cornwall Council, 2015)

External links

[edit]- Council of the Isles of Scilly

- Map sources for Isles of Scilly

Isles of Scilly

View on GrokipediaEtymology

Name and Linguistic Origins

The name "Isles of Scilly" entered English usage by the medieval period, with the archipelago appearing in records under variants such as "Suly" or "Sulley" as early as the 12th century.[9] These forms reflect an anglicization of earlier Celtic or Latinized designations, evolving into the modern "Scilly" through phonetic shifts, including the addition of the letter "c" without clear ancient precedent.[10] The term "Scilly" likely stems from a pre-Roman substrate, potentially linked to insular Celtic languages spoken in the region prior to Anglo-Saxon influence.[11] Scholarly consensus on the precise etymology remains elusive, with multiple hypotheses rooted in linguistic and historical evidence. One prominent theory posits derivation from Cornish Syllan or a related Brythonic form, possibly denoting "rocky place" or echoing ancient insular nomenclature, as preserved in medieval Latin records like Insulae Sillinae.[12] A folk etymology, popularized in local histories, interprets "Sully" as "sun islands" (sōl-īeg), alluding to the mild subtropical climate with over 1,900 annual sunshine hours, though this lacks direct philological support and may conflate descriptive usage with origin.[8] Norse influence is another candidate, with Viking-era references to Syllingeyjar or Syllorgar suggesting adaptation from Old Norse ey ("island") combined with a Celtic base, consistent with Scandinavian raids documented from the 9th to 11th centuries.[13] Recent philological analysis by Andrew Breeze proposes a Mediterranean origin, tracing "Scilly" to ancient Greek Sílyres or Súrines, potentially via Bronze Age trade networks linking Cornwall's tin exports to Mycenaean Greece around 2000–1200 BCE; the earliest attested form, Silimnus in classical texts, may represent a Hellenized rendering of a local toponym, predating Roman contact.[14] [11] This view challenges insular-centric models by invoking evidence of Aegean artifacts in southwest Britain, such as imported pottery from sites like Mount Batten, though it remains contested due to sparse textual corroboration beyond Ptolemy's 2nd-century CE Geography. Alternative links to Roman Sulis (a syncretic solar deity) or Cornish silya ("conger eel," referencing marine fauna) appear in secondary sources but derive from speculative morphology rather than attested usage.[15] [16] In Cornish, the contemporary designation is Enesow Syllan, underscoring linguistic continuity with the Duchy of Cornwall, where the islands retain cultural ties despite administrative separation since 1890.[17] The absence of definitive primary sources—such as pre-Norman inscriptions—leaves room for ongoing debate, with etymologies informed more by comparative linguistics than direct attestation.[18]History

Prehistoric Settlement and Ancient Monuments

Evidence of human activity in the Isles of Scilly dates to the Mesolithic period, with hunter-gatherer visits around 6000 BCE indicated by flint tools and other artifacts, though no permanent settlements from this era have been identified.[19] Neolithic presence is sparse, limited to occasional finds suggesting seasonal exploitation rather than sustained occupation. Permanent settlement began in the Early Bronze Age circa 2250 BCE, coinciding with the construction of ceremonial and burial monuments, as the islands transitioned from a more connected landmass to a distinct archipelago due to rising sea levels.[20][21] The archipelago features one of Britain's highest densities of prehistoric monuments, with 239 scheduled ancient monuments across 16 square kilometers, over 60% of the land area holding archaeological significance.[22] Dominant among these are Bronze Age entrance graves—rectangular or oval burial chambers with corbelled roofs and antechambers—unique to Scilly and western Cornwall, exemplified by well-preserved examples like Bant's Carn on St. Mary's, dating to approximately 2000–1500 BCE.[23][24] Cairns, standing stones, and cliff sanctuaries further attest to ceremonial practices, while Middle Bronze Age sites reveal stone-built houses and field systems indicating organized agriculture and domestic life.[21] St. Mary's hosts the most diverse prehistoric remains, including these burial structures and evidence of continuous use into later periods.[23] Iron Age occupation, from circa 800 BCE to the Roman era, is marked by promontory forts such as the one at Borough Cove on St. Mary's and settlements like Halangy Down on the same island, occupied from around 200 BCE with stone houses and artifacts showing trade links.[22] A notable 1st-century BCE cist burial on Bryher contained a sword, mirror, and other grave goods, identified through ancient DNA analysis as belonging to a female warrior, challenging assumptions about gender roles in prehistoric warfare; this represents the richest Iron Age burial in Scilly and one of the earliest decorated bronze mirrors in Britain.[25] Prehistoric field systems and enclosures on islands like St. Agnes and Little Ganilly further demonstrate sustained agrarian communities adapting to the islands' isolation.[26] These monuments, preserved due to minimal modern development, provide insights into a sequence of maritime-oriented societies reliant on fishing, farming, and ritual landscapes.[27]Medieval and Norse Influences

In the late 10th century, the Isles of Scilly served as a waypoint for Norse seafarers during raids across the British Isles. Around 986 AD, the Norwegian prince Olaf Tryggvason, later king of Norway, landed on the islands during his campaigns. There, he encountered a seer who prophesied his future kingship and urged his conversion to Christianity, leading to his baptism on Scilly before continuing to England.[28][29] This event, recorded in Norse sagas, marks an early intersection of pagan Viking activity and emerging Christian influences in the region, though Olaf's stay was temporary and tied to his raiding expeditions rather than settlement.[30] Norse raids persisted into the 12th century, with the Orkneyinga Saga documenting an attack on the islands, referred to as Syllingar, by the Orcadian Viking Sweyn Asleifsson around 1150 AD. Sweyn, known for his maritime prowess, targeted the isles during broader campaigns in the British Isles, contributing to disruptions of local monastic sites.[31][32] Archaeological and textual evidence suggests limited permanent Norse settlement, but transient visits influenced local lore and possibly place names; for instance, St Agnes may derive from Old Norse elements hagi (pasture) and nes (headland), indicating grazing areas on promontories.[33] Medieval Christian institutions emerged amid these Norse incursions, reflecting integration into broader Cornish ecclesiastical networks. The Priory of St Nicholas on Tresco, established around 1114 AD as a Benedictine cell dependent on Tavistock Abbey, represented an early monastic outpost, though it faced repeated raids that damaged its structures.[34][35] By the 13th century, defensive architecture developed, exemplified by Ennor Castle on St Mary's, first documented in a 1244 AD deed as a shell keep fortification guarding the harbor and serving administrative functions under local lords.[36] These developments underscore the islands' strategic role in medieval Cornwall, balancing vulnerability to seaborne threats with efforts to fortify and evangelize the remote archipelago.Early Modern Period and English Civil War

In the 16th century, the Isles of Scilly gained strategic importance as a potential naval base for continental powers threatening England, prompting the construction of early fortifications. The Old Blockhouse, an artillery fort on Tresco, was erected between 1548 and 1554 to defend against invasion, while Harry's Walls, an ambitious but unfinished bastioned fort on St Mary's, was initiated in 1551 under Edward VI's government to protect the principal harbor at Hugh Town.[23][37] The Godolphin family, who held a Crown lease on the islands from the mid-1500s, managed their governance and defense; Sir Francis Godolphin (c.1534–1608) served as governor from 1568, overseeing repairs and expansions including Star Castle around 1593 amid fears of Spanish attack.[38][39] During the English Civil War (1642–1651), the Isles remained a Royalist outpost under the governorship of Sir Francis Godolphin (1605–1667), who fortified key sites like the Garrison on St Mary's with earthworks and batteries to counter Parliamentarian advances.[40] After mainland Royalist defeats, Sir John Grenville assumed command in 1648, transforming the islands into a privateering base that disrupted Parliamentarian and neutral Dutch shipping in the Western Approaches, with captured prizes funding defenses.[41][42] Parliament, viewing Scilly's position as a threat to trade routes, dispatched a fleet under Sir Robert Blake; following a blockade and bombardment, Grenville surrendered on 4 June 1651 after negotiations, marking the last Royalist stronghold in England to fall.[43] The capitulation briefly entangled the Isles in undeclared hostilities with the Dutch Republic, who had allied with Parliament but lacked a formal peace treaty with Scilly until a ceremonial resolution in 1986—though no combat ensued.[43] Post-surrender, Parliamentarian forces enhanced batteries, such as the eponymous Oliver's Battery, to secure the archipelago against potential Royalist resurgence.[39]19th and 20th Century Developments

The 19th century brought concerted efforts to address the Isles of Scilly's notorious maritime perils, where rocky reefs and frequent fog contributed to hundreds of shipwrecks. The Bishop Rock Lighthouse, constructed on a narrow granite ledge four miles west of the islands, exemplified these advancements; initiated in 1847 with an iron structure that was destroyed by storms before completion, the permanent granite tower was finished in 1858 under Trinity House oversight, standing 49 meters tall with interlocking blocks to withstand Atlantic gales.[44] [45] Further reinforcement with iron tie bars occurred in the 1880s after erosion threatened the foundation, reducing wreck incidents and supporting safer passage for trade vessels reliant on the islands' piloting services.[45] Economic diversification accelerated with the onset of commercial flower farming, leveraging the archipelago's frost-free microclimate. In 1879, local resident William Richards dispatched a consignment of wild narcissi to London's Covent Garden market, sparking organized cultivation of bulbs like daffodils and lilies for export; by the late 19th century, small-scale growers had established hedgerows and fields, shifting from subsistence piloting and fishing toward horticulture as a cash crop.[46] This industry expanded into the early 20th century, with exports reaching approximately 40 tonnes shipped twice weekly by steamer, employing much of the resident population in labor-intensive picking and packing before competition from overseas producers eroded profitability post-1950s.[47] The World Wars imposed temporary military impositions on civilian life. During World War I, the islands hosted Royal Naval Air Service flying boats for anti-submarine patrols, utilizing St. Mary's as a staging point amid U-boat threats in the Western Approaches. World War II saw heightened fortifications, including 27 concrete pillboxes concentrated on St. Mary's to deter potential invasion, alongside a detachment of RAF Hurricane fighters from No. 87 Squadron for coastal defense; radar installations and troop rotations further integrated the Isles into Britain's defensive network, though no direct combat occurred.[48] [49] Postwar recovery emphasized accessibility and leisure, fostering tourism as a pillar alongside declining agriculture. Regular steamship links via the Isles of Scilly Steamship Company, established in the early 1900s, and the development of St. Mary's Airport in the interwar period enabled influxes of visitors drawn to subtropical flora, beaches, and mild weather, generating over half of contemporary revenue by mid-century through hotels and excursions.[18] This transition reflected broader causal shifts from peril-dependent economies to service-oriented ones, sustained by the Duchy of Cornwall's land stewardship.[50]Recent History and Infrastructure Projects

The Isles of Scilly have experienced persistent housing pressures in the 21st century, exacerbated by high demand from tourism-related seasonal employment and limited land availability, leading the Council of the Isles of Scilly to declare a housing crisis in January 2022, with projections of 15 households facing homelessness and potential off-island relocation by March of that year.[51] Economic reliance on tourism, agriculture (notably flower production), and small-scale fishing has been challenged by workforce retention issues, prompting a Housing and Economic Needs Assessment launched in October 2025 to evaluate resident experiences, affordable housing shortages, and growth opportunities.[52] In September 2025, the Duchy of Cornwall announced plans for 10 sustainable homes on St Mary's to address urgent local demand, emphasizing low-carbon construction amid broader regional homelessness strains in Cornwall and the Isles.[53][54] Transport infrastructure upgrades have prioritized reliability for the islands' 2,200 residents and visitors, given their isolation 28 miles southwest of Cornwall. The Isles of Scilly Steamship Group initiated a vessel replacement program, constructing Scillonian IV—a passenger ferry with 24% increased capacity (up to 600 passengers per sailing)—to succeed the 48-year-old Scillonian III, though delivery delayed from 2026 to 2027 due to construction setbacks; the accompanying cargo vessel Menawethan remains on schedule for spring 2026 arrival and commissioning.[55][56] Air connectivity advanced via Skybus operations at St Mary's Airport, with a new aircraft leased from Aurigny Air Services entering service in November 2025 for enhanced resilience, alongside summer 2025 expansion to two daily flights from Newquay Airport starting May 12 (up from three weekly).[57][58] Helicopter services, operated by a local firm, expanded to a three-aircraft fleet in May 2025, supporting up to 17 daily crossings from the mainland.[59] Digital and cultural infrastructure projects aim to bolster connectivity and heritage preservation. In April 2024, Wildanet secured a £41 million contract to deliver gigabit broadband across Cornwall and the Isles, marking the third major investment to improve remote access and support economic diversification.[60] Construction commenced in October 2024 on the Isles of Scilly Cultural Centre and Museum, transforming St Mary's Town Hall into a facility for local history exhibits and community events, funded through regeneration initiatives.[61] Energy resilience efforts, including the European-funded Smart Energy Isles project, have explored integrated hubs for sewage treatment, district heating, and renewables, though sewage upgrades sought since 2014 remain partially unresolved due to costs exceeding £11.7 million.[62][63]Geography

Archipelago Composition and Topography

The Isles of Scilly comprise approximately 200 low-lying granite islands, islets, and rocks, spanning a total land area of about 1,600 hectares.[7] Of these, five principal islands are inhabited: St Mary's, the largest and most populous; Tresco, the second largest; St Martin's; Bryher; and St Agnes.[50] [64] St Mary's serves as the main entry point for visitors, covering slightly more than 6 square kilometres, while Tresco measures 297 hectares.[64] [3] The archipelago's topography features undulating granite terrain with modest elevations, primarily gentle hills and rocky outcrops.[65] The highest point is Telegraph Hill on St Mary's, reaching 51 metres above sea level.[66] Coastal landscapes dominate, characterized by rugged shorelines, exposed granite cliffs on windward sides, and sheltered sandy bays on leeward aspects, interspersed with numerous reefs that contribute to hazardous navigation.[5] Inland areas include heathlands, freshwater pools, and limited arable land, shaped by the islands' exposure to Atlantic winds and shallow soils derived from weathered granite.[7]| Principal Island | Approximate Area | Notable Topographic Features |

|---|---|---|

| St Mary's | >6 km² | Highest elevation at 51 m; varied terrain with hills and harbours[64] [66] |

| Tresco | 297 ha | Low hills; sheltered gardens and abbey ruins amid coastal dunes[3] |

| St Martin's | Not specified | Elevated eastern ridges; white sandy beaches and granite tors[7] |

| Bryher | Not specified | Rugged western cliffs up to 40 m; Hell Bay's dramatic seascapes[67] |

| St Agnes | Not specified | Lowest and most remote; guano-covered rocks and coastal heath[50] |

Geology and Formation