Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Qutbism

View on Wikipedia

| Part of a series on |

| Conservatism |

|---|

|

| Part of a series on |

| Islamism |

|---|

|

Qutbism[a] is an exonym that refers to the Sunni Islamist beliefs and ideology of Sayyid Qutb,[1] a leading Islamist revolutionary of the Muslim Brotherhood who was executed by the Egyptian government of Gamal Abdel Nasser in 1966.[2] Influenced by the doctrines of earlier Islamists like Hasan al-Banna and Maududi, Qutbism advocates Islamic extremist violence in order to establish an Islamic government, in addition to promoting offensive Jihad.[3] Qutbism has been characterized as an Islamofascist and Islamic terrorist ideology.[3]

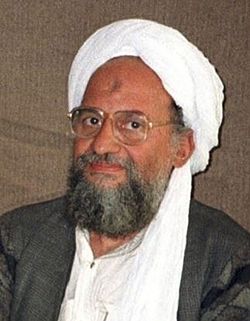

Sayyid Qutb's treatises deeply influenced numerous jihadist ideologues and organizations across the Muslim world.[1][4][5] Qutbism has gained prominence due to its influence on notable Jihadist figures of contemporary era such as Abdullah Azzam, Osama bin Laden, Ayman al-Zawahiri, and Saif al-Adel.[4][5][6][7] Its ideas have also been adopted by the Salafi-jihadist terrorist organization Islamic State (ISIL).[8] It was one inspiration that influenced Ruhollah Khomeini in the development of his own ideology, Khomeinism.[9]

Qutbist literature has been a major source of influence on numerous jihadist movements and organizations that have emerged since the 1970s.[1][4][5] These include the Egyptian Islamic Jihad, al-Jama'ah al-Islamiyya, al-Takfir wal-Hijra, the Armed Islamic Group of Algeria (GIA), the Libyan Islamic Fighting Group (LIFG), al-Qaeda, al-Nusra Front, and the Islamic State (ISIL), and others that have sought to implement their strategy of waging offensive Jihad.[1][4][5][10][11][12]

Terminology

[edit]While adherents of Qutbism are referred to as Qutbists or Qutbiyyun (singular: Qutbi), they rarely refer to themselves with these names (i.e. the word is not an endonym); the name was first and still is used by the sect's opponents (i.e. it is an exonym).[13]

Tenets

[edit]The main tenet of the Qutbist ideology is that modern Muslims abandoned true Islam centuries ago, having instead reverted to jahiliyyah.[4][5][8][14] Adherents believe that Islam must be re-established by Qutb's followers.[15]

Qutb outlined his religious and political ideas in his book Ma'alim fi-l-Tariq ("Milestones").[4][5][8] Important principles of Qutbism include:[citation needed]

- Adherence to Sharia as sacred law accessible to humans, without which Islam cannot exist

- Adherence to Sharia as a complete way of life that will bring not only justice, but peace, personal serenity, scientific discovery, complete freedom from servitude, and other benefits;

- Avoidance of Western and non-Islamic "evil and corruption," including socialism, nationalism and consumerist capitalism.[16]

- Vigilance against Western and Jewish conspiracies against Islam;

- A two-pronged attack of

- preaching to convert and,

- jihad to forcibly eliminate the "structures" of Jahiliyya;[17]

- Offensive Jihad to eliminate Jahiliyya not only from the Islamic homeland but from the face of the Earth, seeing it as mutually exclusive with true Islam.[18]

Takfirism

[edit]Qutb declared Islam "extinct," which implied that any Muslims who do not follow his teachings are not actually Muslim. This was intended to shock Muslims into religious rearmament. When taken literally, takfir refers to ex-communication, thereby declaring all non-Qutbist Muslims to be apostates in violation of Sharia law. Violating this law could potentially be punished by death, according to Islamic law.[19]

Because of these serious consequences, Muslims have traditionally been reluctant to practice takfir, that is, to pronounce professed Muslims as unbelievers, even when in violation of Islamic law.[20] This prospect of fitna, or internal strife, between Qutbists and "takfir-ed" mainstream Muslims, led Qutb to conclude that the Egyptian government was irredeemably evil. As a result, he helped to plan a thwarted series of assassinations of Egyptian officials, the discovery of which let to Qutb's trial and eventual execution.[21] Due in part to this teaching, Qutb's ideology remains controversial among Muslims.[22][23]

It is unclear whether Qutb's proclamation of jahiliyyah was meant to apply the global Muslim community or to only Muslim governments.[24]

In the 1980s and 1990s, a series of terrorist attacks in Egypt were committed by Islamic extremists believed to be influenced by Qutb.[25] Victims included Egyptian President Anwar Sadat, head of the counter-terrorism police Major General Raouf Khayrat, parliamentary speaker Rifaat el-Mahgoub, dozens of European tourists and Egyptian bystanders, and over one hundred Egyptian police officers.[26] Qutb's takfir against the Egyptian government, which he believed to be irredeemably evil, was a primary motivation for the attacks.[27] Other factors included frustration with Egypt's economic stagnation and rage over President Sadat's policy of reconciliation with Israel.[28]

History

[edit]Spread of Qutb's ideas

[edit]Qutb's message was spread through his writings, his followers and especially through his brother, Muhammad Qutb. Muhammad was implicated in the assassination plots that led to Qutb's execution, but he was spared the death penalty. After his release from prison, Muhammad moved to Saudi Arabia along with fellow members of the Muslim Brotherhood. There, he became a professor of Islamic Studies and edited, published and promoted his brother Sayyid's works.[29][30]

One of Qutb's key proponents was one of his students, Ayman Al-Zawahiri, who went on to become a member of the Egyptian Islamic Jihad[31] and later a mentor of Osama bin Laden and a leading member of al-Qaeda.[32] He had been first introduced to Sayyad Qutb by his uncle, Mafouz Azzam, who was a close friend to Qutb and taught his nephew that he was an honorable man.[33] Zawahiri paid homage to Qutb in his work Knights under the Prophet's Banner.[34]

Qutbism was propagated by Abdullah Azzam during the Afghan-Soviet War. As the Muslim jihad volunteers from around the world exchanged religious ideas, Qutbism merged with Salafism and Wahhabism, culminating in the formation of Salafi jihadism.[35] Abdullah Azzam was a mentor of bin Laden as well.

Osama bin Laden reportedly regularly attended weekly public lectures by Muhammad Qutb at King Abdulaziz University, and to have read and been deeply influenced by Sayyid Qutb.[36]

The Yemeni Al-Qaeda leader Anwar al-Awlaki also cited Qutb's writings as formative to his ideology.[37]

Many Islamic extremists consider him a father of the movement.[38][39] Ayman al-Zawahiri, former leader of Al-Qaeda, asserted that Qutb's execution lit "the jihadist fire",[38] and reshaped the direction of the Islamist movement by convincing them that the takfir against Muslim governments made them important targets.[39]

Backlash

[edit]Following Qutb's death, his ideas spread throughout Egypt and other parts of the Arab and Muslim world, prompting a backlash by more traditionalist and conservative Muslims, such as the book Du'ah, la Qudah ("Preachers, not Judges") (1969). The book, written by Muslim Brotherhood Supreme Guide Hassan al-Hudaybi, attacked the idea of Takfir of other Muslims, though it was ostensibly intended as a criticism of Mawdudi.[40]

Views

[edit]| Part of a series on |

| Fascism |

|---|

|

Science and learning

[edit]On the importance of science and learning, Qutb was ambivalent.

He wrote that Muslims should learn science and develop their capabilities to fulfill their role as representatives of God.[41] He encouraged Muslims to seek knowledge in abstract sciences and arts, whether from Muslim or non-Muslim teachers, so that Muslim communities will have their own experts.[42]

However, Qutb believed that Muslims were not allowed to study some subjects, including:

the principles of economics and political affairs and the interpretation of historical processes... the origin of the universe, the origin of the life of man... philosophy, comparative religion... sociology (excluding statistics and observations)... Darwinist biology ([which] goes beyond the scope of its observations, without any rhyme or reason and only exists for the sake of expressing an opinion...).[43]

He also believed that the era of scientific discovery in the West was over, and that further scientific discovery must be reached in accordance with Sharia law.[44][45]

On philosophy and kalam

[edit]Qutb also strongly opposed Falsafa and Ilm al-Kalam, which he denounced as deviations which undermined the original Islamic creed because they were based on Aristotelian logic. He denounced these disciplines as alien to Islamic traditions and called for their abandonment in favor of a literalist interpretation of Islamic scriptures.[46]

Sharia and governance

[edit]Qutbism advocates the belief that in a sharia-based society, wonders of justice, prosperity, peace and harmony—both individually and societally—are "not postponed for the next life [i.e. heaven] but are operative even in this world".[47]

Qutb believed harmony and perfection brought by Sharia law is such that the use of offensive jihad to spread sharia-Islam throughout the non-Muslim world is not aggression but rather means of introducing "true freedom" to the masses. Because Sharia law is judged by God rather than man, in this view, enforcing Sharia frees people from servitude to each other.[45]

In other works Qutb describes the ruler of the Islamic state, as a man (never a woman) who "derives his legitimacy from his being elected by the community and from his submission to God. He has no privileges over other Muslims, and is only obeyed as long as he himself adheres to the shari‘a".[48]

Conspiracy theories

[edit]Qutbism emphasizes what it sees as the evil designs of Westerners and Jews against Islam, and it also emphasizes the importance of Muslims not trusting or imitating them.

Non-Muslims

[edit]Qutbisms's teachings on non-Muslims gained attention after the September 11 attacks. Qutb's writings on non-Muslims, particularly Western non-Muslims, are extremely negative. They teach that Christians and Jews are hostile to his movement "simply for being Muslims" and believing in God.[49][50] He refers to "people of the book," who are typically viewed more favorably than other non-Muslims in Islam, as "depraved" for having "falsified" their religious texts.[51]

Qutb believed Ibn Qayyim al-Jawziyya's teachings that the realm outside of Muslim lands was Dar al-Harb ("the Abode of War"), and had to be subjugated by Muslims. Subjugation would actually be "liberation" however,[52] because it "would free men from all authority except that of God."[53] However, this view also necessitates that non-Muslims not be allowed to make law or choose representatives, lest they disobey Islamic law.[54][55]

The West

[edit]In Qutb's view, Western imperialism is not only an economic or racial exploitation means of oppression, but rather an attempt to undermine the faith of Muslims.[56] He believed that historians lied to confuse Muslims and weaken their faith by teaching, for example, that the Crusades were an attempt by Christians to reconquer the formerly Christian-ruled holy land.[57] He believed that the ultimate goal of these efforts was to destroy Muslim society.[58]

Qutb spent two years in the U.S. in the late 1940s and he disliked it immensely.[59] Qutb wrote that he experienced "Western malevolence" during his time there, including an attempt by an American agent to seduce him, and the alleged celebration of American hospital employees upon hearing of the assassination of Egyptian Ikhwan Supreme Guide Hassan al-Banna.[60]

Qutb's critics, particularly in the West, have cast doubts upon these stories. Having not been a member of any government or political organization at the time of his visit, it is unlikely that American intelligence agents would have sought him out. Additionally, many Americans did not know who Hassan al-Banna or the Muslim Brotherhood were in 1948, making the celebration of hospital employees unlikely.[61]

Western corruption

[edit]Qutbism emphasizes a claimed Islamic moral superiority over the West, according to Islamist values. One example of the West's perceived moral decay was the "animal-like" mixing of the sexes, as well as jazz, which he found lurid and distasteful for its association with Black Americans.[62] Qutb states that while he was in America a young woman told him that ethics and sex are separate issues, pointing out that animals do not have any problems mixing freely.

Critics such as Maajid Nawaz protest by arguing that Qutb's complaint about both American racism and the "primitive inclinations" of the "Negro" are contradictory and hypocritical.[62] The place Qutb spent most of his time in was the small city of Greeley, Colorado, dominated by cattle feedlots and an "unpretentious university", originally founded as "a sober, godly, cooperative community".[63]

Jews

[edit]The other anti-Islamic conspiratorial group, according to Qutb, is "World Jewry," because that it is engaging in tricks to eliminate "faith and religion", and trying to divert "the wealth of mankind" into "Jewish financial institutions" by charging interest on loans.[64] Jewish designs are so pernicious, according to Qutb's logic, that "anyone who leads this [Islamic] community away from its religion and its Quran can only be [a] Jewish agent."[65]

Criticism

[edit]By Muslims

[edit]While Ma'alim fi-l-Tariq [Arabic: معالم في الطريق] (Milestones) was Qutb's manifesto, other elements of Qutbism are found in his works Al-'adala al-Ijtima'iyya fi-l-Islam [Arabic: العدالة الاجتماعية في الاسلام] (Social Justice in Islam), and his Quranic commentary Fi Zilal al-Qur'an [Arabic: في ظلال القرآن] (In the shade of the Qur'an). Ideas in (or alleged to be in) those works also have been criticized by some traditionalist/conservative Muslims. They include:

- Qutb's assertion that slavery was now illegal under Islam, as its lawfulness was only temporary, existing only "until the world devised a new code of practice, other than enslavement."[Note 1] Many contemporary Islamic scholars, however, do share the view that slavery is not allowed in Islam in modern times. On the other hand, according to Salafi critics such as Saleh Al-Fawzan, "Islam has affirmed slavery ... And it will continue so long as Jihaad in the path of Allah exists."[67]

- Proposals to redistribute income and property to the needy. Opponents claim they are revisionist and innovations of Islam.[68][69][70]

- Describing Moses as having an "excitable nature" – this allegedly being "mockery," and "mockery of the Prophets is apostasy in its own,'" according to Shaikh ‘Abdul-Aziz ibn Baz.[citation needed]

- Dismissing fiqh or the schools of Islamic law known as madhhab as separate from "Islamic principles and Islamic understanding."[71]

- Describing Islamic societies as being sunk in a state of Jahiliyyah (pagan ignorance) implying takfir. Salafi scholars like (Albani, Rabee bin Hadi, Ibn Baz, Ibn Jibreen, Ibn Uthaymeen, Saalih al-Fawzan, Muqbil ibn Hadi, etc.) would condemn Qutb as a heretic for takfiri views as well as for what they considered to be theological deviancies and these ideologies were widely refuted by Al Allāmah Rabee Ibn Hadi Al Madkhali in his books and audio tapes. They also identified his methodology as a distinct "Qutbi' manhaj", thus resulting in the labelling of Salafi-Jihadis as "Qutbists" by many of their quietist Salafist opponents.[72][73][74][75][76][77][78]

Qutb may now be facing criticism representing his idea's success or Qutbism's logical conclusion as much as his idea's failure to persuade some critics. Writing before the Islamic revival was in full bloom, Qutb sought Islamically correct alternatives to European ideas like Marxism and socialism and proposed Islamic means to achieve the ends of social justice and equality, redistribution of private property and political revolution. But according to Olivier Roy, contemporary "neofundamentalists refuse to express their views in modern terms borrowed from the West. They consider indulging in politics, even for a good cause, will by definition lead to bid'a and shirk (the giving of priority to worldly considerations over religious values.)"[79]

There are, however, some commentators who display an ambivalence towards him, and Roy notes that "his books are found everywhere and mentioned on most neo-fundamentalist websites, and arguing his "mystical approach", "radical contempt and hatred for the West", and "pessimistic views on the modern world" have resonated with these Muslims.[80]

Criticism by Americans

[edit]James Hess, an analyst at the American Military University (AMU), labelled Qutbism as "Islamic-based terrorism".[81] In his essay criticizing the doctrines of Qutbist ideology, US Army colonel Dale C. Eikmeier described Qutbism as "a fusion of puritanical and intolerant Islamic orientations that include elements from both the Sunni and Shia sects".[82]

Relationship with the Muslim Brotherhood

[edit]The controversy over Qutbism is partially caused by two opposing factions which exist within the Islamic revival: the politically quiet Salafi Muslims, and the politically active Muslim groups which are associated with the Muslim Brotherhood.[83]

Although Sayyid Qutb was never the head of the Muslim Brotherhood,[84] he was the Brotherhood's "leading intellectual,"[85] the editor of its weekly periodical, and a member of the highest branch in the Brotherhood, the Working Committee and the Guidance Council.[86]

Hassan al-Hudaybi, the leader of the Muslim Brotherhood, argued against takfir and adopted a tolerant attitude. In response, some Qutbists concluded that the Muslim Brotherhood had abandoned their ideology.[87] Ayman al-Zawahiri, a prominent Qutbist, also attacked the Muslim Brotherhood.[87]

After the publication of Ma'alim fi-l-Tariq (Milestones), opinion in the Brotherhood split over his ideas, though many in Egypt (including extremists outside the Brotherhood) and most of the Muslim Brotherhood's members in other countries are said to have shared his analysis "to one degree or another."[88] However, the leadership of the Brotherhood, headed by Hassan al-Hudaybi, remained moderate and interested in political negotiation and activism. By the 1970s, the Brotherhood had renounced violence as a means of achieving its goals.[89] In recent years, his ideas have been embraced by Islamic extremist groups,[90] while the Muslim Brotherhood has tended to serve as the official voice of Moderate Islamism.

Influence on Jihadist movements

[edit]In 2005, the British author and religion academic Karen Armstrong declared, regarding the ideological framework of al-Qaeda, that al-Qaeda and nearly every other Islamic fundamentalist movement was influenced by Qutb. She proposed the term "Qutbian terrorism" to describe violence by his followers.[91]

According to The Guardian journalist Robert Manne, "there exists a more or less general consensus that the ideology of the Islamic State was founded upon the principles which were set forth by Qutb", particularly based on some sections of his treatises Milestones and In the Shade of the Qur'an.[92]

However, the self-declared Islamic State in Iraq and Syria, headed by Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi, has been described by various analysts as being more violent than al-Qaeda and closely aligned with Wahhabism,[93][94][95] alongside Salafism and Salafi jihadism.[96][97] In 2014, regarding the ideology of IS, Karen Armstrong remarked that "IS is certainly an Islamic movement [...] because its roots are in Wahhabism, a form of Islam practised in Saudi Arabia that developed only in the 18th century".[93]

Nabil Na'eem, a former associate of Ayman al-Zawahiri and an ex-Islamic Jihad leader, argued that Qutb's writings were the main factor that led to the rise of Al-Qaeda, Islamic State and various Jihadist groups.[98][99]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ An example of the conflict between government-approved orthodox Islamic clerics in agreement with Qutb that slavery "is now illegal under Islam", and traditionalists who disagree, was a report of a televised "ceremony" of contemporary "melk al-yameen" [slavery] marriage in July 2012, where "a Muslim cleric, who gave his name as 'Abdul Raouf Aun'", married a woman who "voluntarily gave ownership of herself to" Aun, who also conducted the "marriage." Aun explained that "this form of marriage [does] not requiring witnesses or official confirmation". The marriage was condemned by the al-Azhar Islamic Research Centre as an example of "apostasy and a return to jahiliyyah", and by Egypt's Grand Mufti, Dr. Ali Gomaa as religiously impermissible and akin to "adultery."[66]

Citations

[edit]- ^ a b c d Polk, William R. (2018). "The Philosopher of the Muslim Revolt, Sayyid Qutb". Crusade and Jihad: The Thousand-Year War Between the Muslim World and the Global North. The Henry L. Stimson Lectures Series. New Haven and London: Yale University Press. pp. 370–380. doi:10.2307/j.ctv1bvnfdq.40. ISBN 978-0-300-22290-6. JSTOR j.ctv1bvnfdq.40. LCCN 2017942543.

- ^ Qutbism Archived 2021-08-01 at the Wayback Machine Earthlysojourner.com

- ^ a b Eikmeier, Dale C. (Spring 2007). "Qutbism: An Ideology of Islamic-Fascism" (PDF). The US Army War College Quarterly: Parameters. 37 (1). Carlisle, Pennsylvania: Army War College Foundation Press: 84–97. doi:10.55540/0031-1723.2340. ISSN 0031-1723. Retrieved 10 September 2024.[permanent dead link]

- ^ a b c d e f Moussalli, Ahmad S. (2012). "Sayyid Qutb: Founder of Radical Islamic Political Ideology". In Akbarzadeh, Shahram (ed.). Routledge Handbook of Political Islam (1st ed.). London and New York City: Routledge. pp. 24–26. ISBN 9781138577824. LCCN 2011025970.

- ^ a b c d e f Cook, David (2015) [2005]. "Radical Islam and Contemporary Jihad Theory". Understanding Jihad (2nd ed.). Berkeley: University of California Press. pp. 102–110. ISBN 9780520287327. JSTOR 10.1525/j.ctv1xxt55.10. LCCN 2015010201.

- ^ Aydınlı, Ersel (2018) [2016]. "The Jihadists pre-9/11". Violent Non-State Actors: From Anarchists to Jihadists. Routledge Studies on Challenges, Crises, and Dissent in World Politics (1st ed.). London and New York City: Routledge. p. 66. ISBN 978-1-315-56139-4. LCCN 2015050373.

- ^ Gallagher, Eugene V.; Willsky-Ciollo, Lydia, eds. (2021). "Al-Qaeda". New Religions: Emerging Faiths and Religious Cultures in the Modern World. Vol. 1. Santa Barbara, California: ABC-CLIO. pp. 13–15. ISBN 978-1-4408-6235-9.

- ^ a b c Baele, Stephane J. (October 2019). Giles, Howard (ed.). "Conspiratorial Narratives in Violent Political Actors' Language". Journal of Language and Social Psychology. 38 (5–6). SAGE Publications: 706–734. doi:10.1177/0261927X19868494. hdl:10871/37355. ISSN 1552-6526. S2CID 195448888. Archived from the original (PDF) on 3 January 2022. Retrieved 3 January 2022.

- ^ "Why Sayed Qutb inspired Iran's Khomeini and Khamenei". Al-Arabiya News. Retrieved 3 September 2018.

- ^ Roy, Olivier (1994). The Failure of Political Islam. Translated by Volk, Carol. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press. p. 113. ISBN 0-674-29140-9.

- ^ Jenkins, Frampton, Wilson, Sir John, Dr Martyn, Tom (2020). "Understanding Islamism" (PDF). Policy Exchange. 8 – 10 Great George Street, Westminster, London SW1P 3AE: 1–37. ISBN 978-1-913459-46-8 – via policyexchange.org.uk.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: location (link) CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Shay, Shaul (2008). Somalia Between Jihad and Restoration. New Brunswick, New Jersey, USA: Transaction Publishers. p. 17. ISBN 978-1-4128-0709-8.

- ^ Pioneers of Islamic revival by ʻAlī Rāhnamā, p. 175

- ^ Qutb, Sayyid, Milestones, The Mother Mosque Foundation, 1981, p. 9

- ^ Muslim extremism in Egypt: the prophet and pharaoh by Gilles Kepel, p. 46

- ^ Kepel, Gilles; Kepel, Professor Gilles (January 1985). Muslim Extremism in Egypt. University of California Press. ISBN 9780520056879. Retrieved 26 February 2015.

- ^ Muslim extremism in Egypt: the prophet and pharaoh by Gilles Kepel, pp. 55–6

- ^ SOAGE, ANA BELÉN (June 2009). "Islamism and Modernity: The Political Thought of Sayyid Qutb". Totalitarian Movements and Political Religions. 10 (2): 192. doi:10.1080/14690760903119092. S2CID 144071957. Retrieved 9 March 2021.

- ^ Eikmeier, DC (Spring 2007). Qutbism: An Ideology of Islamic-Fascism. Vol. 37. Parameters, US Army War College Quarterly. p. 89.

In addition to offensive jihad Sayyid Qutb used the Islamic concept of "takfir" or excommunication of apostates. Declaring someone takfir provided a legal loophole around the prohibition of killing another Muslim and in fact made it a religious obligation to execute the apostate. The obvious use of this concept was to declare secular rulers, officials or organizations, or any Muslims that opposed the Islamist agenda a takfir thereby justifying assassinations and attacks against them. Sheikh Omar Abdel Rahman, who was later convicted in the 1993 World Trade Center attack, invoked Qutb's takfirist writings during his trial for the assassination of President Anwar Sadat. The takfir concept along with "offensive jihad" became a blank check for any Islamic extremist to justify attacks against anyone.

- ^ Kepel, Jihad, p. 31

- ^ Sivan, Radical Islam, (1985), p. 93

- ^ "Hakikat Kitabevi". Archived from the original on 11 February 2012. Retrieved 26 February 2015.

- ^ "The Wahhabi Myth – Salafism, Wahhabism, Qutbism. Who was Sayyid Qutb? (part 2)". Retrieved 26 February 2015.[permanent dead link]

- ^ Kepel, Jihad, 2002, p. 31

- ^ Sayyid Qutb and the Origins of Radical Islamism by John Calvert, p. 285

- ^ Passion for Islam: Shaping the Modern Middle East: The Egyptian Experience by Caryle Murphy, p. 91

- ^ Kepel, The Prophet and Pharaoh, pp. 65, 74–5, Understanding Jihad by David Cook, University of California Press, 2005, p. 139

- ^ Kepel, Jihad, 2002, p. 31,

Ruthven, Malise, Islam in the World, Penguin Books, 1984, pp. 314–15 - ^ Kepel, War for Muslim Minds, (2004) pp. 174–75

- ^ Kepel, Jihad, (2002), p. 51

- ^ Sageman, Marc, Understanding Terror Networks, University of Pennsylvania Press, 2004, p. 63

- ^ "How Did Sayyid Qutb Influence Osama bin Laden?". Retrieved 26 February 2015.

- ^ Wright, Looming Tower, 2006, p. 36

- ^ "Sayyid_Qutbs_Milestones". Retrieved 26 February 2015.

- ^ Hassan, Hassan. (June 13, 2016). The Sectarianism of the Islamic State: Ideological Roots and Political Context. Carnegie Endowment for Peace. Retrieved 3 December 2017.

- ^ Wright, Looming Tower, 2006, p. 79

- ^ Scott Shane; Souad Mekhennet & Robert F. Worth (8 May 2010). "Imam's Path From Condemning Terror to Preaching Jihad". The New York Times. Retrieved 13 May 2010.

- ^ a b Eikmeier, Dale (Spring 2007). "Qutbism: An Ideology of Islamic-fascism". Parameters: U.S. Army War College Journal: 89. Retrieved 10 March 2021.

- ^ a b Fawaz A. Gerges, The Far Enemy: Why Jihad Went Global, (Bronxville, N.Y.: Sarah Lawrence College) 2005, prologue, http://www.cambridge.org/us/catalogue/catalogue.asp?isbn=9780521791403

- ^ Sayyid Qutb and the Origins of Radical Islamism by John Calvert, p. 274

- ^ Qutb, Milestones p. 112

- ^ (Qutb, Milestones p. 109)

- ^ (Qutb, Milestones pp. 108–10)

- ^ [Qutb, Milestones p. 8]

- ^ a b [Qutb, Milestones p. 90]

- ^ Qutb, Sayyid. "Introduction: A Word About the Methodology". The Islamic Concept and Its Characteristics (PDF). pp. 6–8.

- ^ [Qutb, Milestones p. 91]

- ^ Qutb, Al-‘adala al-ijtima‘iyya fi’l-Islam, pp.102–6; Ma‘rikat al-Islam wa’l-ra’smaliyya, p.74; quote by A.B. SOAGE and cited in SOAGE, ANA BELÉN (June 2009). "Islamism and Modernity: The Political Thought of Sayyid Qutb". Totalitarian Movements and Political Religions. 10 (2): 197. doi:10.1080/14690760903119092. S2CID 144071957. Retrieved 9 March 2021.

- ^ Reference to the Qur’anic verse: ‘And the Jews will not be pleased with thee, nor will the Christians, till thou follow their creed’ (2:120); cited in SOAGE, ANA BELÉN (June 2009). "Islamism and Modernity: The Political Thought of Sayyid Qutb". Totalitarian Movements and Political Religions. 10 (2): 198. doi:10.1080/14690760903119092. S2CID 144071957. Retrieved 9 March 2021.

- ^ Reference to the Qur’anic verse: ‘And the Jews will not be pleased with thee, nor will the Christians, till thou follow their creed’ (2:120). cited in SOAGE, ANA BELÉN (June 2009). "Islamism and Modernity: The Political Thought of Sayyid Qutb". Totalitarian Movements and Political Religions. 10 (2): 198. doi:10.1080/14690760903119092. S2CID 144071957. Retrieved 9 March 2021.

- ^ Qutb, Fi zilal al-Qur’an, p.924. Muslim Islamic scholars "explain the contradictions between the Qur’an and the Bible by saying that the Jews and the Christians deliberately distorted God’s message to hide references to the advent of prophet Muhammad"; cited in SOAGE, ANA BELÉN (June 2009). "Islamism and Modernity: The Political Thought of Sayyid Qutb". Totalitarian Movements and Political Religions. 10 (2): 198. doi:10.1080/14690760903119092. S2CID 144071957. Retrieved 9 March 2021.

- ^ Qutb, Ma‘alim fi’l-tariq, pp.78–9, 88–9, 110–1; Fi zilal al-Qur’an, pp.1435–6; cited in SOAGE, ANA BELÉN (June 2009). "Islamism and Modernity: The Political Thought of Sayyid Qutb". Totalitarian Movements and Political Religions. 10 (2): 197. doi:10.1080/14690760903119092. S2CID 144071957. Retrieved 9 March 2021.

- ^ Qutb, Fi zilal al-Qur’an, pp.294–5; Ma‘alim fi’l-tariq, p.83; SOAGE, ANA BELÉN (June 2009). "Islamism and Modernity: The Political Thought of Sayyid Qutb". Totalitarian Movements and Political Religions. 10 (2): 197. doi:10.1080/14690760903119092. S2CID 144071957. Retrieved 9 March 2021.

- ^ Qutb, Ma‘alim fi’l-tariq, pp.87, 101–2.; cited in SOAGE, ANA BELÉN (June 2009). "Islamism and Modernity: The Political Thought of Sayyid Qutb". Totalitarian Movements and Political Religions. 10 (2): 198. doi:10.1080/14690760903119092. S2CID 144071957. Retrieved 9 March 2021.

- ^ Qutb, Fi zilal al-Qur’an, p.295; cited in SOAGE, ANA BELÉN (June 2009). "Islamism and Modernity: The Political Thought of Sayyid Qutb". Totalitarian Movements and Political Religions. 10 (2): 198. doi:10.1080/14690760903119092. S2CID 144071957. Retrieved 9 March 2021.

- ^ Qutb, Milestones, Chapter 12

- ^ Qutb, Milestones, pp. 159–60

- ^ Qutb, Milestones, p. 116

- ^ Hagler, Aaron M. "The America That I Have Seen", The Effect of Sayyid Quṭb's Colorado Sojourn on the Political Islamist Worldview". Academia. ACM/ Andrew W. Mellon Postdoctoral Teacher/Scholar FellowDepartment of HistoryCornell College, Mt. Vernon, IA. Retrieved 10 March 2021.

- ^ Wright, The Looming Tower, 2006

- ^ Soufan Ali, The Black Banners, October 2008

- ^ a b Nawaz, Maajid (2016). Radical: My Journey out of Islamist Extremism. Rowman & Littlefield. p. xxi. ISBN 9781493025725. Retrieved 10 March 2021.

- ^ Von Drehle, David (February 2006). "A Lesson In Hate". Smithsonian Magazine. Retrieved 10 March 2021.

- ^ The age of sacred terror, Daniel Benjamin, Steven Simon, p. 68

- ^ quote from David Zeidan, "The Islamic Fundamentalist View of Life as Perennial Battle," Middle East Review of International Affairs, v. 5, n. 4 (December 2001), criticism from The Age of Sacred Terror by Daniel Benjamin and Steven Simon, Random House, 2002, p. 68

- ^ "Egypt: "Slavery marriage" case sparks controversy". Asharq Al-Awsat. 16 July 2012. Archived from the original on 18 May 2017. Retrieved 10 March 2021.

- ^ see also: Shaikh Salih al-Fawzaan "affirmation of slavery" p. 24 of "Taming a Neo-Qutubite Fanatic Part 1 Archived 2009-03-19 at the Wayback Machine" when accessed on February 17, 2007

- ^ "Hakikat Kitabevi". Archived from the original on 23 February 2007. Retrieved 26 February 2015.

- ^ "Hakikat Kitabevi". Archived from the original on 23 February 2007. Retrieved 26 February 2015.

- ^ "Hakikat Kitabevi". Archived from the original on 24 February 2007. Retrieved 26 February 2015.

- ^ "Hakikat Kitabevi". Archived from the original on 19 February 2012. Retrieved 26 February 2015.

- ^ "The Heresies of Sayyid Qutb in Light of the Statements of the Ulamaa (Part 1)". Salafi Publications. Archived from the original on 5 January 2020.

- ^ "Shaykh Muhammad bin Saalih al-Uthaymeen Distinguished Between The Salafi Manhaj and The Qutbi Manhaj and Wholeheartedly Recommended Warning From the Qutbi Manhaj After Detailed Study and Consideration". Madkhalis.com. 21 December 2009. Archived from the original on 5 February 2021.

- ^ "Shaykh Ibn Uthaymeen and Shaykh al-Fawzaan: Between the Salafi Manhaj and the Qutubi Manhaj". Madkhalis.com. 31 December 2009. Archived from the original on 3 December 2020.

- ^ "Sayyid Qutb, The Doctrine of Wahdat ul-Wujood, Imaam al-Albaanee and Abdullaah Azzaam:Part 2 – Shaykh al-Albaanee on Abdullaah Azzam – a 'Dhaalim' Who Failed To Publish a Retraction From His Slander". Madkhalis.com. 5 January 2010. Archived from the original on 3 December 2020.

- ^ "Shaykh Salih Aal ash-Shaykh: The Ghuluww (Extremism) of Sayyid Qutb in Takfir of the Sinners". Madkhalis.com. 19 December 2009. Archived from the original on 26 January 2021.

- ^ "Sheikh Al-Albāni about Sayyid Qutb". Muflihun.com. 8 February 2016. Archived from the original on 26 October 2020.

- ^ "Shaikh Ibn Baz on Sayyid Qutb". Salafi Publications. Archived from the original on 28 February 2021.

- ^ Roy, Globalized Islam, (2004), p. 247

- ^ Roy, Globalized Islam, (2004), p. 250

- ^ Hess, James (8 April 2018). "PERSPECTIVE: A Dual Strategy to Empower Intelligence to Confront Ideology-Based Terror". Homeland Security Today. Retrieved 9 March 2021.

- ^ William McCants of the US Military Academy's Combating Terrorism Center, quoted in Qutbism: An Ideology of Islamic-Fascism by Dale C. Eikmeier. From Parameters, Spring 2007, pp. 85–98.

- ^ Kepel, Gilles, The War for Muslim Minds, 2004, pp. 253–266

- ^ Hasan al-Hudaybi was its Supreme Guide during this period,

- ^ Ruthvan, Malise, Islam in the World, Penguin, 1984

- ^ Moussalli, Radical Islamic Fundamentalism, 1992, pp. 31–2

- ^ a b Leiken, Robert (2011). Europe's Angry Muslims: The Revolt of The Second Generation, p. 89

- ^ Hamid Algar from his introduction to Social Justice in Islam by Sayyid Qutb, translated by John Hardie, translation revised and introduction by Hamid Algar, Islamic Publications International, 2000, p.1, 9, 11

- ^ Kepel, Gilles, Jihad: the Trail of Political Islam, p. 83

- ^ William McCants, a Bahai consultant, quoted in Qutbism: An Ideology of Islamic-Fascism Archived 2007-06-09 at the Wayback Machine by Dale C. Eikmeier From Parameters, Spring 2007, pp. 85–98.

- ^ Armstrong, Karen (10 July 2005). "The label of Catholic terror was never used about the IRA". The Guardian. London. Archived from the original on 13 February 2014. Retrieved 28 June 2021.

- ^ Manne, Robert (3 November 2016). "The mind of Islamic State: more coherent and consistent than Nazism". The Guardian. London. Archived from the original on 28 January 2017. Retrieved 28 June 2021.

There exists a more or less general consensus that the ideology of the Islamic State is founded upon the prison writings of the revolutionary Egyptian Muslim Brother Sayyid Qutb, in particular some sections of his commentary In the Shade of the Qur'an, but most importantly his late visionary work Milestones, published in 1964.

- ^ a b Armstrong, Karen (27 November 2014). "Wahhabism to ISIS: how Saudi Arabia exported the main source of global terrorism". New Statesman. London. Archived from the original on 27 November 2014. Retrieved 28 June 2021.

- ^ Crooke, Alastair (30 March 2017) [First published 27 August 2014]. "You Can't Understand ISIS If You Don't Know the History of Wahhabism in Saudi Arabia". The Huffington Post. New York City. Archived from the original on 28 August 2014. Retrieved 28 June 2021.

- ^ Sells, Michael (22 December 2016). "Wahhabist Ideology: What It Is And Why It's A Problem". The Huffington Post. New York City. Archived from the original on 8 April 2020. Retrieved 28 June 2021.

- ^ Bunzel, Cole (March 2015). "From Paper State to Caliphate: The Ideology of the Islamic State" (PDF). The Brookings Project on U.S. Relations with the Islamic World. 19. Washington, D.C.: Center for Middle East Policy (Brookings Institution): 1–48. Archived (PDF) from the original on 21 March 2015. Retrieved 28 June 2021.

- ^ Wood, Graeme (March 2015). "What ISIS Really Wants". The Atlantic. Washington, D.C. Archived from the original on 16 February 2015. Retrieved 28 June 2021.

- ^ al-Saleh, Huda (28 March 2017). "Former Egyptian Islamic Jihad leader Nabil Naeem: Zawahiri himself is ignorant". AlArabiya News. Archived from the original on 31 March 2021.

- ^ N. Celso, Anthony (14 April 2014). "Jihadist Organizational Failure and Regeneration: The Transcendental Role of Takfiri Violence" (PDF): 1–23 – via Political Studies Association, UK.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help)

Bibliography

[edit]- Kepel, Gilles (1985). The Prophet and Pharaoh: Muslim Extremism in Egypt. translated by Jon Rothschild. Al Saqi. ISBN 0-86356-118-7.

- Kepel, Gilles (2002). Jihad, The Trail of Political Islam. translated by Anthony F. Roberts. Belknap Press of Harvard University. ISBN 0-674-00877-4.

- Moussalli, Ahmad S. (1992). Radical Islamic Fundamentalism: the Ideological and Political Discourse of Sayyid Qutb. American University of Beirut.

- Qutb, Sayyid (2003). Milestones. Kazi Publications. ISBN 1-56744-494-6.

- Roy, Olivier (2004). Globalized Islam: the Search for a New Ummah. Columbia University Press. ISBN 0-231-13498-3.

- Sivan, Emmanuel (1985). Radical Islam: Medieval Theology and Modern Politics. Yale University Press.

Further reading

[edit]- Berman, Paul. Terror and Liberalism. W. W. Norton & Company, April 2003.

- Berman devotes several chapters of this work to discussing Qutb as the foundation of a unique strain of Islamist thought.

- Malik, S. K. (1986). The Quranic Concept of War (PDF). Himalayan Books. ISBN 81-7002-020-4.

- Swarup, Ram (1982). Understanding Islam through Hadis. Voice of Dharma. ISBN 0-682-49948-X.

- Trifkovic, Serge (2006). Defeating Jihad. Regina Orthodox Press, USA. ISBN 1-928653-26-X.

- Phillips, Melanie (2006). Londonistan: How Britain is Creating a Terror State Within. Encounter books. ISBN 1-59403-144-4.

External links

[edit]- Stanley, Trevor Sayyid Qutb, The Pole Star of Egyptian Salafism.

- El-Kadi, Ahmed Great Muslims of the 20th Century ... Sayyid Qutb.

- Mawdudi, Qutb and the Prophets of Allah.

- The Ideology of Terrorism and Violence in Saudi Arabia: Origins, Reasons and Solution

- C. Eikmeier, Dale Qutbism: An Ideology of Islamic-Fascism

Qutbism

View on GrokipediaQutbism is an Islamist ideology derived from the writings of Egyptian thinker Sayyid Qutb (1906–1966), particularly his 1964 manifesto Milestones (Ma'alim fi al-Tariq), which posits that sovereignty (hakimiyyah) belongs exclusively to God and that contemporary Muslim societies, including their rulers and institutions, exist in a state of jahiliyyah (pre-Islamic ignorance or barbarism) requiring violent jihad by a vanguard of true believers to dismantle and replace with sharia-based governance.[1][2]

Central to Qutbism is the doctrine of takfir, the declaration of existing Muslim governments and populations as apostates, justifying their overthrow through offensive jihad as a religious obligation rather than defensive response, a radical departure from traditional Islamic jurisprudence that influenced the formation of militant groups like Egyptian Islamic Jihad and al-Qaeda.[2][3]

While Qutb's ideas emerged from critiques of Western materialism and Nasserist secularism during his imprisonment, Qutbism has been characterized as fusing Islamist revivalism with totalitarian methods akin to fascism, prioritizing ideological purity over democratic processes or gradual reform, and contributing causally to global jihadist movements through its emphasis on revolutionary violence against perceived internal enemies within the ummah.[4][2][5]

Definition and Origins

Terminology and Core Concepts

Qutbism refers to the Islamist ideology articulated by Egyptian thinker Sayyid Qutb (1906–1966), particularly in his 1964 work Milestones (Ma'alim fi al-Tariq), which frames modern societies—including those in Muslim-majority countries—as existing in jahiliyyah, a state of ignorance and rebellion against divine authority traditionally associated with pre-Islamic Arabia but expanded by Qutb to encompass any system governed by human laws rather than God's sovereignty (hakimiyyah).[6][7] This redefinition posits that jahiliyyah persists wherever tawhid (the oneness of God) is compromised by man-made governance, rendering such societies un-Islamic and requiring Muslims to reject allegiance to them.[2] Central to Qutbist terminology is hakimiyyah, the exclusive legislative authority of Allah, which precludes democracy, nationalism, or secularism as forms of shirk (associating partners with God) since they elevate human will over divine law.[6] Qutb emphasized dissociation (talaq or bara') from jahili institutions as a prerequisite for authentic faith, arguing that true believers must form a separate community to challenge and dismantle these structures.[7] While Qutb avoided blanket takfir (declaration of apostasy) for individuals, his societal critique enabled followers to apply it to rulers enforcing non-Sharia systems, justifying their removal.[6][2] The pathway to an Islamic order (nizam Islami) involves a vanguard (jama'at mutaqaddimah), a small elite of rigorously trained Muslims emulating the Prophet Muhammad's early companions in Mecca, who initiate revolutionary jihad—not merely defensive but offensive—to eradicate jahiliyyah and establish Sharia-based governance ensuring justice and equality under piety rather than race, class, or nationality.[6][7] This vanguard operates through phases of preaching, organization, and confrontation, viewing jihad as an eternal obligation to universalize God's rule.[2]

Sayyid Qutb's Background and Influences

Sayyid Qutb was born in 1906 in the rural village of Musha in Egypt's Asyut province to a family rooted in conservative Islamic traditions. He began his education in local state primary schools before relocating to Cairo around 1920 for secondary studies and enrollment at Dar al-Ulum, a teacher-training institution equivalent to a college, graduating in 1933. During this period, Qutb absorbed influences from Egyptian secular nationalism and socialism, shaping his initial literary output as a poet and critic.[4] From 1933 to 1952, Qutb served in various roles within Egypt's Ministry of Education, including as a teacher, school inspector, and administrator, while publishing extensively on literature and social issues. In 1948, the Egyptian government sponsored his travel to the United States for educational studies, where he spent two years primarily in Greeley, Colorado, and later in California and Washington, D.C. Qutb documented his revulsion toward aspects of American society, including perceived moral decay, racial discrimination against African Americans, consumerism, and cultural phenomena like jazz concerts and Christian worship services, experiences that accelerated his rejection of Western modernity.[4] Returning to Egypt in 1950, Qutb formally affiliated with the Muslim Brotherhood in 1953, rising quickly to become one of its chief propagandists and ideologues under the legacy of founder Hasan al-Banna. Key intellectual influences included Abu al-A'la Maududi's formulations of hakimiyya (divine sovereignty) and jahiliyyah (pre-Islamic ignorance applied to modern societies), which Qutb encountered around 1951 and integrated into his critique of secular regimes. His support for the 1952 Free Officers' coup against the monarchy soured into opposition to Gamal Abdel Nasser's government, leading to his arrest in 1954 amid a broader crackdown on the Brotherhood; the ensuing imprisonment until 1964, involving reported torture and harsh conditions, decisively radicalized his thought toward revolutionary Islamism. Qutb was hanged on August 29, 1966, following a trial for alleged conspiracy.[8][4]