Recent from talks

All channels

Be the first to start a discussion here.

Be the first to start a discussion here.

Be the first to start a discussion here.

Be the first to start a discussion here.

Welcome to the community hub built to collect knowledge and have discussions related to Outline of Islam.

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Outline of Islam

View on Wikipediafrom Wikipedia

| Part of a series on |

| Islam |

|---|

Islam is an Abrahamic monotheistic religion teaching that there is only one God (Allah)[1] and that Muhammad is His last Messenger.[2][3]

The following outline is provided as an overview of and topical guide to Islam.

Beliefs

[edit]| Part of a series on Aqidah |

|---|

|

Including: |

Aqidah

[edit]- Allah

- God in Islam

- Tawhid, Oneness of God

- Repentance in Islam

- Islamic views on sin

- Shirk, Partnership and Idolatory

- Haram

- Kufr

- Bid‘ah

Prophets

[edit]

| ||

|---|---|---|

|

Career Views and Perspectives

|

||

Scripture

[edit]| Quran |

|---|

| Part of a series on |

| Hadith |

|---|

|

|

|

- List of Islamic texts

Denominational specifics

[edit]| Part of a series on |

| Ali |

|---|

|

- Shia beliefs

- Ahl al-Kisa

- Imamah

- Mourning of Muharram

- Tawassul

- The Four Companions

- Shia clergy

- Twelver beliefs

- Ismaili beliefs

- Nizari Ismaili beliefs

- Alevi beliefs

- Ahmadi beliefs

Practice

[edit]Denominational specifics

[edit]- Shia rituals

- Ahmadiyya view

Schools and branches

[edit]

| Part of a series on Sunni Islam |

|---|

|

|

|

| Part of a series on:

Salafi movement |

|---|

|

|

|

- Schools of Islamic theology

- Madhhab

- Divisions of the world in Islam

- Islamic schools and branches a.k.a. The Islamic denomination or Muslim denominations

- Denominational

- Sunni Islam, a.k.a. Ahlus Sunnah wal Jamaah

- Shia Islam

- Kharjites

- Ibadi

- Sufism – Tariqa – List of Sufi orders

- Schools of Jurisprudence, Branches, Doctrines and Movements

- Sunni

- Hanafi

- Maliki

- Shafi'i

- Hanbali

- Zahiri

- Ahl al-Hadith, (School of 2nd/3rd Islamic centuries)

- Ahl-i Hadith, (Movement in South-Asia in mid-nineteenth English century)

- Salafi movement

- Wahhabism

- Shia

- Sunni

- Schools of Islamic theology

- Other branches

- Denominational

- Conferences, Movements and Organizations on Union and Peace

- Amman Message

- 2016 international conference on Sunni Islam in Grozny

- Organisation of Islamic Cooperation

- The World Forum for Proximity of Islamic Schools of Thought

- Islamic Unity week

- Al-Azhar Shia Fatwa

- International Islamic Unity Conference (Iran)

- International Islamic Unity Conference (US)

- Al-Azhar Shia Fatwa

- The World Forum for Proximity of Islamic Schools of Thought

- The Humanitarian Forum

- Islamic Relief

- British Muslim Forum

- Muslim Charities Forum

- Catholic–Muslim Forum

- Muslim Safety Forum

- A Common Word Between Us and You

- Hindu–Muslim unity

Philosophy

[edit]- Islamic philosophy

- Early Islamic philosophy

- Islamic ethics

- Logic in Islamic philosophy

- Islamic metaphysics

- Sufi philosophy

- Islamic attitudes towards science

- Science in the medieval Islamic world

- Alchemy and chemistry in the medieval Islamic world

- Astrology in the medieval Islamic world

- Astronomy in the medieval Islamic world

- Cosmology in medieval Islam

- Geography and cartography in the medieval Islamic world

- Mathematics in the medieval Islamic world

- Medicine in the medieval Islamic world

- Prophetic medicine

- Ophthalmology in the medieval Islamic world

- Physics in the medieval Islamic world

- Psychology in the medieval Islamic world

- Islamic view of miracles

- Contemporary Islamic philosophy

Theology

[edit]- Islamic religious sciences

- Islamic theology

- Theological concepts

- Ahl al-Hadith (started in 2nd/3rd Islamic centuries)

- Ahl-i Hadith (another movement in South-Asia in mid-nineteenth English century)

- Ahl ar-Ra'y

- Divisions of the world in Islam

- Fi sabilillah

- Ihsan

- Iman

- Itmam al-hujjah

- Wasat

- Shia theological concepts

- Categorization of individuals

- Groups

- Theological titles

- Theological concepts

- Islamic mythology

- Beings

- Exorcism in Islam, Ruqya

- Places

- Islamic eschatology

Law

[edit]| Part of a series on |

| Islamic jurisprudence (fiqh) |

|---|

|

| Islamic studies |

- Sharia

- Fiqh, The Islamic jurisprudence

- Hisbah

Hadith

[edit]- Main article

- Hadith

- Important Sunni Hadith

- Kutub al-Sittah

- Sahih al-Bukhari

- Sahih Muslim

- Al-Sunan al-Sughra

- Sunan Abu Dawood

- Jami` at-Tirmidhi

- Sunan ibn Majah

- Important Shia Hadith

- The Four Books

- Kitab al-Kafi

- Man la yahduruhu al-Faqih

- Tahdhib al-Ahkam

- Al-Istibsar

- Hadith Collectors

- Muhammad al-Bukhari

- Muslim ibn al-Hajjaj

- Abu Dawood

- Commentary for Sahih al-Bukhari

- Fath al-Bari

- Related

- Hadith studies

- Hadith terminology

The supernatural in Islam

[edit]- Islamic Concept of God

- God in Islam

- Names of God in Islam

- Allah

- The Light before the Material World

- Nūr (Islam)

- Muhammad in Islam

- Al-Insān al-Kāmil

- Holy Spirit in Islam

- The Angels

- Angels in Islam

- Alam al Jabarut

- Archangel

- Artiya'il

- Azrael

- Cherub

- Darda'il

- Gabriel

- Habib

- Harut and Marut

- Illiyin

- Israfil, Raphael (archangel)

- Jannah

- Kiraman Katibin

- Michael (archangel)

- Mu'aqqibat, Hafaza, The Guardian angels

- Recording angel

- Riḍwan

- Seraph

- Beings and Forces in ordinary life

- Asmodeus

- Barakah

- Al-Baqarah

- Al-Ikhlas

- Al-Mu'awwidhatayn

- Adhan

- Throne Verse, also known as Al-Baqara 255 and Ayatul Kursi

- Evil eye

- Hatif

- Hinn (mythology)

- Ifrit

- Jinn

- Sura Al-Jinn

- Exorcism in Islam

- Marid

- Magic (paranormal)

- Malakut

- Peri

- Qalb

- Qareen

- Solomon in Islam

- Death and Human spirit

- Barzakh

- Illiyin

- Islamic view of death

- Munkar and Nakir

- Nāzi'āt and Nāshiṭāt

- Nafs

- Rūḥ

- Fallen Angels, Devils and Hell

- As-Sirāt

- Azazil

- Dajjal

- Div

- Falak (Arabian legend)

- Fallen angel

- Iblis

- Jahannam

- Maalik

- Nar as Samum

- Shaitan

- Sijjin

- Zabaniyya

- Zaqqum

Islamic Legends

[edit]- Adam in Islam

- Akhirah

- Al-Safa and Al-Marwah

- Azazel

- Azrael

- Barzakh

- Beast of the Earth

- Biblical and Quranic narratives

- Biblical figures in Islamic tradition

- Black Standard

- Black Stone

- Cain and Abel in Islam

- Crescent

- Darda'il

- Devil (Islam)

- Dhul-Qarnayn

- Dome of the Rock

- Foundation Stone

- Gabriel

- Gog and Magog

- Green in Islam

- Hafaza

- Hajj

- Harut and Marut

- Hateem

- Holy Spirit (Islam)

- Ishmael in Islam

- Islamic eschatology

- Islamic flags

- Islamic view of angels

- Islamic view of Jesus' death

- Isra and Mi'raj

- Israfil

- Jahannam

- Jannah

- Jesus in Ahmadiyya Islam

- Jesus in Islam

- Kaaba

- Khidr

- Kiraman Katibin

- Kiswah

- Maalik

- Mahdi

- Mary in Islam

- Masih ad-Dajjal

- Michael (archangel)

- Moses in Islam

- Mu'aqqibat

- Munkar and Nakir

- Noah in Islam

- Queen of Sheba

- Raphael (archangel)

- Recording angel

- Ridwan (name)

- Rub el Hizb

- Sarah

- Satan

- Solomon in Islam

- Star and crescent

- Symbols of Islam

- Tawaf

- The Occultation

- Well of Souls

- Zamzam Well

- Zaqqum

History

[edit]- History of Islam

- Timeline of Muslim history Year by Year

- Timeline of 6th-century Muslim history

- Timeline of 7th-century Muslim history

- Timeline of 8th-century Muslim history

- Timeline of 9th-century Muslim history

- Timeline of 10th-century Muslim history

- Timeline of 11th-century Muslim history

- Timeline of 12th-century Muslim history

- Timeline of 13th-century Muslim history

- Timeline of 14th-century Muslim history

- Timeline of 15th-century Muslim history

- Timeline of 16th-century Muslim history

- Timeline of 17th-century Muslim history

- Timeline of 18th-century Muslim history

- Timeline of 19th-century Muslim history

- Timeline of 20th-century Muslim history

- Timeline of 21st-century Muslim history

- Early history

- Classical era

- Pre-Modern era

- Modern times

History of Islam by topic

[edit]Society

[edit]| Today (at UTC+00) | |

|---|---|

| Sunday | |

| Gregorian calendar | 9 November, AD 2025 |

| Islamic calendar | 18 Jumada al-awwal, AH 1447 (using tabular method) |

| Hebrew calendar | 18 Cheshvan, AM 5786 |

| Coptic calendar | 30 Paopi, AM 1742 |

| Solar Hijri calendar | 18 Aban, SH 1404 |

| Bengali calendar | 24 Kartik (month), BS 1432 |

| Julian calendar | 27 October, AD 2025 |

- Ummah

- Islamic calendar

- Islam and humanity

- Islam and children

- Gender roles in Islam

- Women in Islam

- LGBT in Islam

- Mukhannathun

- Islam and clothing

- Animals in Islam

- Muslim holidays

- Qurbani

- Nursing in Islam

- Symbols of Islam

- Islamic education

Places

[edit]- Holiest sites in Islam

- Mecca

- Medina

- Al Quds

- Holiest sites in Sunni Islam

- Holiest sites in Shia Islam

Culture

[edit]- Islamic culture

- Islamic art

- Islamic architecture

- Architectural elements

- Architectural types

- Islamic calligraphy

- Islamic garden

- Islamic glass

- Islamic literature

- Islamic music

- Oriental rug

- Islamic pottery

- Islam and sport

Politics

[edit]- Political aspects of Islam

- Shia–Sunni relations

- Islam and modernity

- Persecution of Muslims

- Persecution of minority Muslim groups

- Islamophobia

- Islamophobic incidents

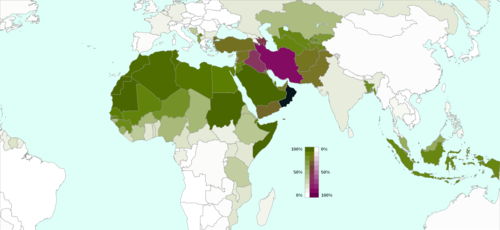

Muslim world

[edit]

| Islam by country |

|---|

|

|

|

- Muslim world

- Islamic organizations

- International organization

- Islamic political parties

- Islamic democratic

- National Islamic Movement of Afghanistan (Afghanistan)

- Islamic Renaissance Movement (Algeria)

- Al-Menbar Islamic Society (Bahrain)

- Bangladesh Islami Front (Bangladesh)

- Islami Oikya Jote (Bangladesh)

- Party of Democratic Action (Bosnia and Herzegovina)

- Al-Wasat Party (Egypt)

- National Awakening Party (Indonesia)

- National Mandate Party (Indonesia)

- United Development Party (Indonesia)

- All India Majlis-e-Ittehadul Muslimeen (India)

- Indian Union Muslim League (India)

- Islamic Action Organisation (Iraq)

- Islamic Dawa Party (Iraq)

- Islamic Fayli Grouping in Iraq (Iraq)

- Kurdistan Islamic Group (Iraq)

- Islamic Labour Movement in Iraq (Iraq)

- Islamic Union of Iraqi Turkoman (Iraq)

- Islamic Centrist Party (Jordan)

- National Patriotic Party (Kazakhstan)

- United Malays National Organisation (Malaysia)

- Jamaat-e-Islami Pakistan (Pakistan)

- Pakistan Tehreek-e-Insaf (Pakistan)

- Lakas–CMD (Philippines)

- Moro Islamic Liberation Front (Philippines)

- United Bangsamoro Justice Party (Philippines)

- Ideal Democratic Party (Rwanda)

- Sri Lanka Muslim Congress (Sri Lanka)

- Ennahda Movement (Tunisia)

- Islamic liberal

- Islamic Iran Participation Front (Iran)

- National Forces Alliance (Libya)

- Sunni Islamist

- Islamic Dawah Organisation of Afghanistan (Afghanistan)

- Hezbi Islami (Afghanistan)

- Jamiat-e Islami (Afghanistan)

- Green Algeria Alliance (Algeria)

- Movement of Society for Peace (Algeria)

- Movement for National Reform (Algeria)

- Bangladesh Jamaat-e-Islami (Bangladesh)

- Islamic Front Bangladesh (Bangladesh)

- Committee for National Revolution (East Turkestan)

- Freedom and Justice Party (Egypt)

- Building and Development Party (Egypt)

- Islamic Party (Egypt)

- Prosperous Justice Party (Indonesia)

- Crescent Star Party (Indonesia)

- Reform Star Party (Indonesia)

- Iraqi Islamic Party (Iraq)

- Kurdistan Islamic Union (Iraq)

- Zamzam (party) (Jordan)

- Islamic Action Front (Jordan)

- Hadas (Kuwait)

- Al-Jama'a al-Islamiyya (Lebanon)

- Justice and Construction Party (Libya)

- Homeland Party (Libya)

- Malaysian Islamic Party (PAS) (Malaysia)

- Islamic Democratic Party (Maldives)

- Justice and Development Party (Morocco)

- Jamiat Ahle Hadith (Pakistan)

- Jamiat Ulema-e Islam (F) (Pakistan)

- Hamas (Palestine)

- National Congress (Sudan)

- Muslim Brotherhood of Syria (Syria)

- Islamic Renaissance Party of Tajikistan (Tajikistan)

- Felicity Party (Turkey)

- Shia Islamist

- Islamic Movement of Afghanistan (Afghanistan)

- Hizb-i-Wahdat (Afghanistan)

- Islamic Party of Azerbaijan (Azerbaijan)

- Al Wefaq (Bahrain)

- Bahrain Freedom Movement (Bahrain)

- Islamic Action Society (Bahrain)

- Hezbollah (Lebanon)

- Alliance of Builders of Islamic Iran (Iran)

- Islamic Coalition Party (Iran)

- National Iraqi Alliance (Iraq)

- Islamic Dawa Party – Iraq Organisation (Iraq)

- Islamic Supreme Council of Iraq (Iraq)

- Islamic Virtue Party (Iraq)

- Tehrik-e-Jafaria (Pakistan)

- Salafist

- Al Asalah (Bahrain)

- Young Kashgar Party (East Turkestan)

- Al-Nour Party (Egypt)

- Adhaalath Party (Maldives)

- Muttahida Majlis-e-Amal (Pakistan)

- Al-Islah (Yemen)

- Islamic democratic

- Militant organization

- Non-governmental organization

- Muslim Brotherhood (Egypt)

- Muhammadiyah (Indonesia)

- Nahdlatul Ulama (Indonesia)

- Indonesian Ulema Council (Indonesia)

- PERSIS (organization) (Indonesia)

- Islamic Defenders Front (Indonesia)

- Tamil Nadu Muslim Munnetra Kazagham (India)

- Popular Front of India (India)

- Dawat-e-Islami (Pakistan)

- Society of the Revival of Islamic Heritage

- Muslim World League

- Islamic relief organizations

People

[edit]Key religious figures

[edit]Muhammad

[edit]Sahabah

[edit]- Ashara e mubashra

- Hadith of the ten promised paradise

- Abu Bakr

- Umar

- Uthman ibn Affan

- Ali

- Talhah

- Az-Zubair

- Abdur Rahman bin Awf

- Sa'd bin Abi Waqqas

- Abu Ubaidah ibn al-Jarrah

- Sa'id ibn Zayd

- Most hadith narrating sahabah

- Abu Hurairah

- Abdullah Ibn Umar

- Anas ibn Malik

- Aisha

- Abd Allah ibn Abbas

- Jabir ibn Abd Allah

- Abu Sa‘id al-Khudri

- Abdullah ibn Masud

- 'Abd Allah ibn 'Amr ibn al-'As

Umar

[edit]- Family tree of Umar

- Umm Kulthum bint Ali (Wife)

- Abdullah ibn Umar (son)

- Hafsa bint Umar (Daughter)

- Asim ibn Umar (son)

- Sunni view of Umar

- Shi'a view of Umar

- Ten Promised Paradise

Uthman

[edit]

Denominational specifics

[edit]Sunni Islam

[edit]- List of Sunni Islamic scholars by schools of jurisprudence

Deobandi

[edit]- List of Deobandis

- List of students of Mahmud Hasan Deobandi

- List of Darul Uloom Deoband alumni

- Ashraf Ali Thanwi

- Hussain Ahmad Madani

Barelvi

[edit]Shia Islam

[edit]- The Four Companions

- Holy women of Shia Islam

- Companions of Ali ibn Abi Talib

- Companions of Ali ibn Husayn Zayn al-Abidin

- List of Shia Imams

Imami Twelver

[edit]| The Fourteen Infallibles |

|---|

Imami Ismailism

[edit]Alevism

[edit]Key figures

Islamism

[edit]Key ideologues

Modernist Salafism

[edit]Salafi movement

[edit]Sufism

[edit]List of Muslims by topic

[edit]Historical

[edit]- List of Ayyubid sultans and emirs

- List of Mamluk sultans

- List of Ghaznavid sultans

- Grand Viziers of the Safavid Empire

- Viziers of the Samanid Empire

- List of Sheikh-ul-Islams of the Ottoman Empire

- Grand Viziers of Ottoman Empire

Denominational / religious-related occupational

[edit]Professional

[edit]

|

Regional

[edit]See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ quran.com, Quran Surah Al-Baqara ( Verse 255 )

- ^ John L. Esposito (2009). "Islam. Overview". In John L. Esposito (ed.). The Oxford Encyclopedia of the Islamic World. Oxford: Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/acref/9780195305135.001.0001. ISBN 9780195305135.

Profession of Faith [...] affirms Islam's absolute monotheism and acceptance of Muḥammad as the messenger of God, the last and final prophet.

- ^ F. E. Peters (2009). "Allāh". In John L. Esposito (ed.). The Oxford Encyclopedia of the Islamic World. Oxford: Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/acref/9780195305135.001.0001. ISBN 9780195305135.

the Muslims' understanding of Allāh is based [...] on the Qurʿān's public witness. Allāh is Unique, the Creator, Sovereign, and Judge of humankind. It is Allāh who directs the universe through his direct action on nature and who has guided human history through his prophets, Abraham, with whom he made his covenant, Moses, Jesus, and Muḥammad, through all of whom he founded his chosen communities, the "Peoples of the Book."

- ^ Quran 19:53

- ^ Quran 19:41

- ^ Quran 9:70

- ^ a b Quran 2:124

- ^ Quran 87:19

- ^ Quran 22:43

- ^ a b c d e Quran 42:13

- ^ Quran 2:31

- ^ a b c d e f g Quran 6:89

- ^ Quran 17:55

- ^ Quran 37:123

- ^ Quran 37:124

- ^ Quran 19:56

- ^ Quran 21:85–86

- ^ a b Quran 26:125

- ^ Quran 7:65

- ^ a b Quran 19:49

- ^ a b Quran 19:54

- ^ a b Quran 26:178

- ^ Quran 7:85

- ^ Quran 19:30

- ^ Quran 4:171

- ^ a b c Quran 46:35

- ^ a b c Quran 33:7

- ^ Quran 57:27

- ^ Quran 61:6

- ^ a b Quran 4:89

- ^ Quran 3:39

- ^ Quran 40:34

- ^ Quran 37:139

- ^ Quran 10:98

- ^ Quran 6:86

- ^ Quran 37:133

- ^ Quran 7:80

- ^ Quran 26:107

- ^ Quran 26:105

- ^ Page 50 "As early as Ibn Ishaq (85–151 AH) the biographer of Muhammad, the Muslims identified the Paraclete – referred to in John's ... "to give his followers another Paraclete that may be with them forever" is none other than Muhammad."

- ^ Quran 33:40

- ^ Quran 33:40

- ^ Quran 42:7

- ^ Quran 7:158

- ^ a b Quran 19:51

- ^ Quran 53:36

- ^ Quran 43:46

- ^ a b Quran 26:143

- ^ Quran 7:73

External links

[edit]Outline of Islam

View on Grokipediafrom Grokipedia

Historical Foundations

Origins and Life of Muhammad

Muhammad ibn Abdullah, the founder of Islam, was born around 570 CE in Mecca, a commercial hub in the Hijaz region of western Arabia controlled by the Quraysh tribe, to which he belonged through the [Banu Hashim](/page/Banu Hashim) clan.[17] [18] His father, Abdullah, died before his birth, and his mother, Amina, passed away when he was approximately six years old, leaving him orphaned and raised first by his grandfather Abdul Muttalib and then by his uncle Abu Talib, a merchant who protected him amid tribal politics and polytheistic practices centered on the Kaaba shrine.[18] [19] As a young adult, Muhammad engaged in trade caravans to Syria, earning a reputation for trustworthiness that led to employment by the wealthy widow Khadija bint Khuwaylid, whom he married around 595 CE at age 25 while she was about 40; their union produced at least four daughters and two sons who died young, with Khadija remaining his sole wife until her death in 619 CE.[19] In his late 30s, troubled by Mecca's social inequalities, idolatry, and moral decay, he retreated for contemplation to the Cave of Hira on Jabal al-Nour near Mecca.[17] Around 610 CE, at age 40, Muhammad experienced what Islamic tradition describes as the first revelation: the angel Gabriel commanded him to "recite" (iqra), delivering initial verses later incorporated into the Quran (Surah 96:1-5), marking the start of his prophethood claim as the final messenger in Abrahamic lineage.[17] He confided initially in Khadija, who supported him and consulted her cousin Waraqa, a Christian familiar with scriptures, affirming the event's divine nature; early converts included Khadija, his cousin Ali (age 10), adopted son Zayd, and friend Abu Bakr.[17] Over 13 years in Mecca (610-622 CE), he preached monotheism (tawhid), social justice, and rejection of idols, attracting about 150 followers but facing hostility from Quraysh elites who saw threats to their economic and religious dominance, leading to boycotts, persecution, and the deaths of some adherents like Bilal's torture and Sumayyah's martyrdom, the first in Islam.[19] Facing assassination plots, Muhammad migrated (Hijra) in 622 CE to Yathrib (renamed Medina), invited as an arbiter among feuding tribes; this event defines the Islamic calendar's start and established the first Muslim community (ummah), formalized in the Constitution of Medina, a pact allying Muslims, local Jews, and pagans under his leadership for mutual defense.[20] [19] In Medina, he unified tribes, directed raids on Meccan caravans to pressure Quraysh economically, and fought defensive battles: Badr (March 624 CE), where 313 Muslims defeated 1,000 Quraysh, killing 70 including leaders like Abu Jahl (victory attributed to divine aid in Quran 3:123); Uhud (March 625 CE), a tactical loss due to archers' disobedience, with Muhammad wounded and 70 Muslims killed; and the Trench (627 CE), where a siege by 10,000 confederates failed amid harsh weather, followed by the execution of Banu Qurayza Jewish males (estimated 400-900) for alleged treason.[19] [17] The 628 CE Treaty of Hudaybiyyah with Mecca allowed pilgrimage access but appeared unequal, yet enabled peaceful conversions, swelling Muslim ranks to 10,000; violated by Quraysh allies, it prompted the bloodless conquest of Mecca in January 630 CE, where Muhammad granted amnesty, destroyed idols in the Kaaba, and declared it a monotheistic sanctuary, consolidating Arabian tribal allegiances.[21] [19] He returned for the Farewell Pilgrimage in 632 CE, delivering a sermon emphasizing equality, women's rights, and unity, before falling ill and dying on June 8, 632 CE in Medina at age 62, buried in his wife Aisha's house adjacent to what became the Prophet's Mosque; his death triggered succession disputes between Abu Bakr's caliphate and Ali's claims, initiating Sunni-Shia division.[21] [19] The biography relies primarily on 8th-9th century Islamic sources like Ibn Ishaq's Sirat Rasul Allah (d. 767 CE, edited by Ibn Hisham) and hadith compilations (e.g., Sahih Bukhari, c. 846 CE), transmitted orally before compilation, which critical scholars view as potentially embellished for theological purposes but corroborated in core outline by 7th-century inscriptions mentioning "Muhammad" as prophet (e.g., 634 CE Syrian stone) and Byzantine/ Armenian chronicles referencing an Arabian leader by 640 CE, affirming his historical existence amid sparse contemporary records.[22] [23]Early Islamic Conquests and Caliphates

Following the death of Muhammad on June 8, 632 CE, Abu Bakr was selected as the first caliph through consultation among prominent companions in Medina, establishing the Rashidun Caliphate (632–661 CE), a period of elective leadership by the "rightly guided" caliphs.[24][25] Abu Bakr's initial challenge was the Ridda Wars (632–633 CE), a series of campaigns against Arabian tribes that renounced Islam, withheld zakat tribute, or followed false prophets like Musaylima ibn Habib and Tulayha ibn Khuwaylid, viewing these as threats to central authority and religious unity.[26][27] Forces under commanders such as Khalid ibn al-Walid suppressed these revolts, with key victories including the Battle of Yamama in December 632 CE, where Musaylima was killed amid heavy casualties estimated at 1,200–7,000 Muslims and up to 21,000 rebels.[28] By mid-633 CE, these wars consolidated Arabia under caliphal control, enabling outward expansion by enforcing Islamic governance and resource extraction for further campaigns.[26] Under the second caliph, Umar ibn al-Khattab (r. 634–644 CE), the conquests accelerated against the exhausted Byzantine and Sassanid empires, weakened by mutual warfare, the Plague of Justinian (541–542 CE aftermath), and internal strife.[29] In the Levant, Muslim armies of approximately 20,000–40,000 defeated Byzantine forces at the Battle of Yarmouk (August 636 CE), leading to the capture of Damascus (September 636 CE), Jerusalem (638 CE under a pact allowing Christian worship), and most of Syria by 640 CE.[24] Simultaneously, in Mesopotamia, the Battle of al-Qadisiyyah (late 636 CE) routed Sassanid armies, followed by the fall of their capital Ctesiphon (March 637 CE) and the defeat of Emperor Yazdegerd III at Nahavand (642 CE), effectively dismantling the Sassanid state.[30] Egypt was invaded in 639 CE, with Alexandria surrendering in 642 CE after sieges, yielding tribute and strategic ports; these victories, driven by mobile Arab cavalry tactics and religious motivation, expanded the caliphate to over 2.2 million square miles by Umar's death, incorporating diverse populations under jizya tax for non-Muslims.[29][25] The third caliph, Uthman ibn Affan (r. 644–656 CE), extended frontiers into Armenia, Cyprus (649 CE raid), and initial North African incursions, standardizing the Quran to unify doctrine amid growing administrative strains.[30] His assassination in 656 CE sparked the First Fitna civil war, during which Ali ibn Abi Talib (r. 656–661 CE), the fourth caliph and Muhammad's cousin, faced rebellions from Muawiya ibn Abi Sufyan in Syria and the Kharijites, culminating in Ali's murder in 661 CE and the caliphate's shift to hereditary rule under the Umayyad dynasty (661–750 CE), founded by Muawiya I.[24] The Umayyads, based in Damascus, pursued further conquests, completing North Africa by 709 CE through campaigns against Berber resistance, and invading the Visigothic Kingdom of Hispania in 711 CE under Tariq ibn Ziyad, who crossed the Strait of Gibraltar with 7,000–12,000 troops, defeating King Roderic at the Battle of Guadalete (July 711 CE) and capturing Toledo, establishing al-Andalus.[31] These expansions, reaching the Indus Valley by 712 CE, relied on Arab settler garrisons (amsar) and fiscal incentives like land grants, but sowed seeds of overextension and ethnic tensions between Arabs and mawali converts.[32]Major Eras of Expansion and Division

The Rashidun Caliphate (632–661 CE), led by the first four successors to Muhammad—Abu Bakr, Umar, Uthman, and Ali—witnessed the initial explosive expansion of Islamic rule, conquering the Byzantine provinces of Syria (by 636 CE at the Battle of Yarmouk), Palestine, and Egypt (by 642 CE), as well as the Sassanid Persian Empire (by 651 CE following the Battle of Nahavand).[33][34] These conquests, driven by tribal Arab armies motivated by religious zeal and economic incentives, transformed a fragmented Arabian Peninsula polity into an empire spanning over 2 million square miles within three decades.[10] This era also initiated profound divisions, notably the First Fitna (656–661 CE), a civil war sparked by the assassination of Uthman and disputes over leadership legitimacy, pitting Ali against Muawiya ibn Abi Sufyan, which entrenched the Sunni-Shia schism rooted in differing views on rightful succession—Sunnis favoring communal election and Shias insisting on Ali's divine designation from Muhammad.[14][35] The Umayyad Caliphate (661–750 CE), established by Muawiya in Damascus, extended Islamic dominion further westward into the Maghreb and al-Andalus (Spain, conquered by 711 CE under Tariq ibn Ziyad) and eastward into Sindh (712 CE) and Transoxiana, reaching a peak territorial extent of approximately 11 million square kilometers by the early 8th century.[36] Arabization and Islamization accelerated through administrative centralization and tax incentives for conversion, though non-Arab Muslims (mawali) faced discrimination, fueling resentment.[32] Divisions intensified with the Second Fitna (680–692 CE), including the martyrdom of Ali's son Husayn at Karbala in 680 CE, which solidified Shia identity around the Ahl al-Bayt (Prophet's family) and opposition to Umayyad "usurpation," while Sunni consensus coalesced around the caliphs' political authority.[12] The Abbasid Revolution (747–750 CE), backed by Persian and Shia elements disillusioned with Umayyad Arab favoritism, toppled the dynasty at the Battle of the Zab, relocating the capital to Baghdad and ushering in a more cosmopolitan but fragmented era.[34] Under the Abbasid Caliphate (750–1258 CE), military expansion waned in favor of intellectual and economic consolidation, with the realm fragmenting into semi-autonomous regions ruled by Turkish mamluks, Buyids, and Seljuks by the 10th century, while Shia Fatimid Caliphate emerged in North Africa and Egypt (909–1171 CE), claiming Ismaili imamate and challenging Abbasid Sunni orthodoxy.[37] The Mongol sack of Baghdad in 1258 CE, led by Hulagu Khan, killed Caliph al-Musta'sim and ended the Abbasid line in Iraq, dissolving centralized caliphal authority and paving the way for regional Islamic powers amid widespread devastation that halved the Muslim world's population in affected areas.[38] Subsequent eras featured rival empires accentuating sectarian divides: the Sunni Ottoman Empire (c. 1299–1924 CE) expanded from Anatolia into the Balkans (conquering Constantinople in 1453 CE) and Arab lands, claiming the caliphate in 1517 CE after defeating the Mamluks and controlling up to 5.2 million square kilometers at its 17th-century zenith under Suleiman the Magnificent.[39] Concurrently, the Shia Safavid Empire (1501–1736 CE) in Persia enforced Twelver Shiism as state religion, converting a majority-Sunni population through coercion and clerical alliances, which provoked wars with the Ottomans (e.g., Chaldiran 1514 CE) and institutionalized the Sunni-Shia geopolitical rift persisting into modern conflicts.[14] These dynamics shifted Islamic expansion from conquest to consolidation and rivalry, with no unified caliphate until its abolition by Turkey in 1924 CE.[35]Scriptural and Doctrinal Core

The Quran as Revelation

Muslims hold that the Quran constitutes the verbatim revelation from God (Allah) delivered to Muhammad via the angel Gabriel over a period of 23 years, from 610 CE to 632 CE.[40] The initial revelation occurred in the Cave of Hira near Mecca during the month of Ramadan in 610 CE, with the command "Iqra" (Recite), marking the surah Al-Alaq as the first disclosed.[41] These disclosures, termed wahy, arrived piecemeal in response to events, comprising approximately 114 surahs (chapters) in Classical Arabic, emphasizing monotheism, moral guidance, and eschatology.[42] The Quran's divine origin is asserted through claims of linguistic inimitability (i'jaz) and predictive elements, though these remain interpretive within Islamic theology rather than empirically verifiable.[43] During Muhammad's lifetime, revelations were primarily transmitted orally, with companions (sahaba) memorizing verses verbatim as huffaz, while scribes like Zaid ibn Thabit recorded them on materials such as palm leaves, bones, and leather.[44] The Prophet reviewed the Quran annually with Gabriel and twice in the final year, establishing its sequence and abrogation (naskh) of earlier verses by later ones.[45] No complete written codex existed at his death in 632 CE, relying instead on distributed fragments and collective memory, which Islamic tradition credits for initial fidelity but modern textual criticism examines for potential oral variations.[46] Following heavy losses of memorizers in the Battle of Yamama (632-633 CE), Caliph Abu Bakr (r. 632-634 CE) commissioned Zaid ibn Thabit to compile a unified mushaf from authenticated written pieces and oral testimonies, cross-verified against multiple witnesses.[47] This codex, housed with Abu Bakr and later Hafsa (Umar's daughter), addressed fears of loss but represented a selective assembly rather than exhaustive reproduction.[48] Under Caliph Uthman (r. 644-656 CE), dialectal recitations proliferated amid empire expansion, prompting a standardization committee—again led by Zaid—to produce authoritative copies in the Quraysh dialect, distributed to major cities, with orders to incinerate divergent variants around 650 CE.[49] This Uthmanic recension forms the basis of all extant Qurans, though early manuscripts like the Birmingham folios (carbon-dated 568-645 CE) exhibit minor orthographic and rasm (consonantal skeleton) differences, indicating a stabilization process involving human curation.[50][51] The Quran's preservation is upheld in Islamic sources as miraculous, with seven to ten canonical qira'at (recitation modes) traced to prophetic approval, yet scholarly analysis of pre-Uthmanic fragments reveals textual fluidity in non-core elements, challenging absolute verbatim uniformity claims while affirming overall consonantal consistency since the 7th century.[52][53] This historical trajectory underscores a transition from oral-prophetic delivery to codified scripture, where empirical evidence supports remarkable stability post-Uthman but highlights the role of caliphal authority in its final form.[54]Articles of Faith and Aqidah

The articles of faith, or arkan al-iman (pillars of faith), form the core doctrinal beliefs in Islam, comprising six fundamental tenets derived from a hadith in which the Prophet Muhammad defines iman (faith) to the angel Jibril in the presence of companions.[55] This hadith, recorded in Sahih Muslim (hadith 8), states: "Faith is to believe in Allah, His angels, His books, His messengers, the Last Day, and the divine decree, both the good and the evil thereof."[56] These beliefs are obligatory for Muslims and underpin aqidah, the systematic Islamic theology that articulates creed through scriptural exegesis and rational defense against deviations.[57] Belief in Allah (tawhid) asserts the absolute oneness, uniqueness, and sovereignty of God, rejecting any partners, associates, or anthropomorphic attributes that compromise divine transcendence, as emphasized in Quran 112:1–4: "Say, He is Allah, [who is] One, Allah, the Eternal Refuge. He neither begets nor is born, nor is there to Him any equivalent."[55] This tenet forms the bedrock of Islamic monotheism, with historical theological schools like the Ash'aris and Maturidis developing defenses against rationalist challenges from Mu'tazilites, who prioritized human reason in interpreting divine attributes.[58] Belief in angels recognizes these as immaterial creations of light, devoid of free will, who execute God's commands, such as Jibril's role in revelations (Quran 2:97).[56] Angels record human deeds (Quran 82:10–12) and serve as intermediaries without independent agency, distinguishing Islamic angelology from polytheistic or dualistic cosmologies.[55] Belief in divine books affirms God's revelations to prophets, with the Quran as the final, unaltered scripture abrogating prior texts like the Torah, Psalms, and Gospel, which Muslims hold were distorted over time (Quran 5:13–14).[57] This underscores the Quran's primacy as verbatim divine speech, preserved since its compilation under Caliph Uthman around 650 CE.[58] Belief in prophets acknowledges a chain of messengers from Adam to Muhammad, all conveying monotheism, with Muhammad as the seal (Quran 33:40). Key figures include Abraham, Moses, and Jesus, viewed as human exemplars without divinity.[56] This linear prophetic history rejects claims of exclusivity in other faiths.[55] Belief in the Last Day anticipates resurrection, judgment, paradise, and hell, where deeds are weighed (Quran 101:6–9), motivating ethical conduct amid eschatological certainty.[57] Belief in qadr (divine decree) holds that God possesses foreknowledge and predetermines all events while granting human accountability through free will, reconciling omniscience with moral responsibility (Quran 57:22).[55] Interpretations vary, with Sunnis emphasizing compatibility between decree and choice, whereas some Shia views integrate it with infallible guidance from Imams.[56] Aqidah encompasses these articles within formalized creeds, such as the Aqidah al-Tahawiyyah (c. 933 CE) for Sunnis, which affirms orthodoxy against innovation (bid'ah), or Shia texts emphasizing Imamate as an extension of prophethood.[57] Theological disputes, like those over God's attributes or free will, arose early, with Sunni consensus codified in texts by scholars like al-Ash'ari (d. 936 CE), prioritizing scripture over speculative philosophy.[58] While shared across major sects, aqidah manifests divergences, such as Shia inclusion of wilayah (allegiance to Ali and Imams) as essential, reflecting post-661 CE schisms.[59] These doctrines demand affirmation through heart, tongue, and action, distinguishing true faith from mere profession.[55]Prophets, Angels, and Predestination

In Islamic doctrine, belief in prophets (anbiya) constitutes a fundamental article of faith, asserting that Allah dispatched messengers to every nation to convey divine guidance and warn against disbelief.[60] The Quran identifies 25 prophets by name, including Adam, the first human and progenitor; Nuh (Noah), who preached monotheism amid a flood; Ibrahim (Abraham), tested through sacrifice and father of monotheistic lineages; Musa (Moses), recipient of the Torah and leader against Pharaoh; Isa (Jesus), born miraculously and performer of miracles; and Muhammad, designated as the final prophet and seal of prophethood.[61] [62] These figures are regarded as infallible in conveying revelation, though human in other respects, with their core message uniformly emphasizing tawhid (oneness of God) and moral accountability.[60] Muslims must affirm all prophets without distinction, rejecting any diminishment of their status, as Quran 2:136 states: "We make no distinction between any of His messengers."[58] Angels (mala'ika), another pillar of faith, are immaterial beings created from light, devoid of free will, gender, or disobedience, existing solely to execute Allah's commands.[63] Their roles encompass revelation, as Jibril (Gabriel) transmitted the Quran to Muhammad over 23 years; sustenance and mercy via Mikail (Michael); heralding the Day of Judgment through Israfil's trumpet blast; and extracting souls at death by the Angel of Death (Malak al-Mawt).[64] Additional functions include recording human deeds by paired scribes (Kiraman Katibin), protecting believers as per Quran 13:11 ("For each one are successive [angels] before and behind him who protect him by the decree of Allah"), and bearing the Throne of Allah in worship.[65] Unlike prophets, angels lack physical form and prophetic mission, serving as intermediaries in the unseen realm without independent agency.[63] Predestination, or al-qadar, affirms Allah's absolute sovereignty over all events through eternal knowledge, decree, will, and creation, recorded in the Preserved Tablet (al-Lawh al-Mahfuz) before creation.[66] This encompasses both good and evil outcomes, as Quran 57:22 declares: "No disaster strikes upon the earth or among yourselves except that it is in a register before We bring it into being—indeed that, for Allah, is easy."[67] Hadith in Sahih Muslim elaborate that qadar operates in stages—Allah's pre-eternal knowledge, inscription 50,000 years before creation, divine willing, and actualization—yet human actions arise from acquired free will (kasb), enabling moral responsibility and judgment.[68] Theological debates, such as those between Ash'aris (emphasizing divine causation) and Mu'tazilis (prioritizing human agency), arise from reconciling decree with accountability, but orthodox Sunni creed upholds both without contradiction, rejecting fatalism that negates striving.[67] Belief in qadar thus fosters submission to divine wisdom while encouraging ethical effort, as unawareness of one's decree precludes predetermining outcomes through inaction.[66]Religious Practices

The Five Pillars

The Five Pillars of Islam represent the core obligatory acts of worship and practice that form the foundation of a Muslim's religious obligations, applicable to all adult Muslims who are physically and financially capable. They are explicitly outlined in a hadith narrated by Ibn Umar, in which the Prophet Muhammad declared: "Islam has been built upon five [pillars]: testifying that there is no deity worthy of worship except Allah and that Muhammad is the Messenger of Allah; establishing the prayer; paying the zakat; fasting the month of Ramadan; and performing Hajj to the House for those who are able."[69] This narration is classified as authentic (sahih) and appears in major Sunni hadith collections, including Sahih al-Bukhari (8) and Sahih Muslim (16).[70] Although the Quran does not enumerate the pillars as a single list, it provides explicit commands for each, emphasizing their role in submission to God (e.g., Quran 2:177). Both Sunni and Shia Muslims recognize these practices as essential religious duties, though Shia traditions frame them within the "branches of faith" (furu' al-din) and incorporate interpretive variations, such as permissible combining of prayers.[71] Shahada (Testimony of Faith)The shahada requires sincere recitation of the declaration: "There is no god but Allah, and Muhammad is the Messenger of Allah" (La ilaha illallah, Muhammadur rasulullah), affirming monotheism (tawhid) and Muhammad's prophethood. It serves as the entry point to Islam, with conversion occurring upon its verbal and heartfelt affirmation before witnesses. The Quran underscores tawhid as the essence of faith (Quran 112:1-4) and Muhammad's role as messenger (Quran 48:29). Recitation five times daily during prayers reinforces it, and denial of either component constitutes disbelief (kufr).[69] Salah (Ritual Prayer)

Salah mandates five daily prayers at prescribed times—dawn (fajr), noon (zuhr), afternoon (asr), sunset (maghrib), and night (isha)—performed facing the Kaaba in Mecca (qibla). Each involves specific recitations, bowing (ruku), and prostration (sujud), totaling 17 rak'ahs (units) per day for able-bodied adults. The Quran commands establishment of prayer over 80 times, linking it to spiritual purification and remembrance of God (Quran 2:43, 20:14). Prayers must be in Arabic, with physical cleansing (wudu or ghusl) beforehand; exemptions apply for illness or travel, allowing shortened or sitting forms. Community prayers (jama'ah) on Fridays (Jumu'ah) replace zuhr for men.[69] Zakat (Almsgiving)

Zakat is an annual wealth tax of 2.5% on savings exceeding the nisab threshold (approximately 85 grams of gold or equivalent, valued at about $5,000 USD as of 2023), distributed to the poor, debtors, and other specified categories. It purifies wealth and fosters social equity, as mandated in the Quran (Quran 9:60 lists eight recipients). Eligible assets include cash, gold, silver, livestock, and business inventory held for a lunar year (hawl); payment is due in Ramadan for some traditions. Unlike voluntary charity (sadaqah), zakat is fard (obligatory), with non-payment risking spiritual penalty.[69] Sawm (Fasting during Ramadan)

Sawm requires abstaining from food, drink, sexual relations, and sinful speech from dawn to sunset throughout Ramadan, the ninth lunar month commemorating the Quran's revelation. Exemptions include the ill, travelers, pregnant or nursing women, and pre-pubescent children, who may make up missed days later or provide fidya (compensation) if unable. The Quran institutes fasting as a means of taqwa (God-consciousness), emulating previous prophets (Quran 2:183-185). It ends with Eid al-Fitr, involving communal prayer and charity (zakat al-fitr, about 3-5 kg of staple food per person). Approximately 1.8 billion Muslims observe it annually, with global participation rates exceeding 90% among adherents in surveys.[69] Hajj (Pilgrimage to Mecca)

Hajj is the once-in-a-lifetime pilgrimage to Mecca during Dhul-Hijjah (12th lunar month), involving rituals at the Kaaba, Arafat, Mina, and Muzdalifah, such as tawaf (circumambulation) and standing at Arafat. It is obligatory only for those with physical health, financial means for travel and support of dependents, and safe passage; about 2-3 million perform it yearly, peaking at 2.5 million in 2019 pre-pandemic. The Quran prescribes it for capable believers (Quran 3:97), symbolizing unity and Abrahamic origins. Non-fulfillment without excuse does not negate faith but incurs sin; Umrah is a non-obligatory pilgrimage anytime.[69]