Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Sustainability

View on Wikipedia

Sustainability (from the latin sustinere - hold up, hold upright; furnish with means of support; bear, undergo, endure) is the ability to continue over a long period of time.[1][2] In modern usage it generally refers to a state in which the environment, economy, and society will continue to exist over a long period of time.[3] Many definitions emphasize the environmental dimension.[4][5] This can include addressing key environmental problems, such as climate change and biodiversity loss. The idea of sustainability can guide decisions at the global, national, organizational, and individual levels.[6] A related concept is that of sustainable development, and the terms are often used to mean the same thing.[7] UNESCO distinguishes the two like this: "Sustainability is often thought of as a long-term goal (i.e. a more sustainable world), while sustainable development refers to the many processes and pathways to achieve it."[8]

Details around the economic dimension of sustainability are controversial.[9] Scholars have discussed this under the concept of weak and strong sustainability. For example, there will always be tension between the ideas of "welfare and prosperity for all" and environmental conservation,[10][9] so trade-offs are necessary. It would be desirable to find ways that separate economic growth from harming the environment.[11] This means using fewer resources per unit of output even while growing the economy.[12] This decoupling reduces the environmental impact of economic growth, such as pollution. Doing this is difficult.[13][14]

It is challenging to measure sustainability as the concept is complex, contextual, and dynamic.[15] Indicators have been developed to cover the environment, society, or the economy but there is no fixed definition of sustainability indicators.[16] The metrics are evolving and include indicators, benchmarks, and audits. They include sustainability standards and certification systems, like Fairtrade and Organic. They also involve indices and accounting systems, such as corporate sustainability reporting and triple Bottom Line accounting.

It is necessary to address many barriers to sustainability to achieve a sustainability transition or sustainability transformation.[6]: 34 [17] Some barriers arise from nature and its complexity while others are extrinsic to the concept of sustainability. For example, they can result from the dominant institutional frameworks in countries.

Global issues of sustainability are difficult to tackle because they need global solutions. The United Nations writes, "Today, there are almost 140 developing countries in the world seeking ways of meeting their development needs, but with the increasing threat of climate change, concrete efforts must be made to ensure development today does not negatively affect future generations" UN Sustainability. Existing global organizations such as the UN and WTO are seen as inefficient in enforcing current global regulations. One reason for this is the lack of suitable sanctioning mechanisms.[6]: 135–145 Governments are not the only sources of action for sustainability. For example, business groups have tried to integrate ecological concerns with economic activity, seeking sustainable business.[18][19] Religious leaders have stressed the need for caring for nature and environmental stability. Individuals can also choose to live more sustainably.[6]

Some people have criticized the idea of sustainability. One point of criticism is that the concept is vague and only a buzzword.[20][9] Another is that sustainability might be an impossible goal.[21] Some experts have pointed out that "no country is delivering what its citizens need without transgressing the biophysical planetary boundaries".[22]: 11

Definitions

[edit]Current usage

[edit]Sustainability is regarded as a "normative concept".[6][23][24][25] This means it is based on what people value or find desirable: "The quest for sustainability involves connecting what is known through scientific study to applications in pursuit of what people want for the future."[24]

The 1983 UN Commission on Environment and Development (Brundtland Commission) had a big influence on the use of the term sustainability today. The commission's 1987 Brundtland Report provided a definition of sustainable development. The report, Our Common Future, defines it as development that "meets the needs of the present without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs".[26][27] The report helped bring sustainability into the mainstream of policy discussions. It also popularized the concept of sustainable development.[9]

Some other key concepts to illustrate the meaning of sustainability include:[24]

- It may be a fuzzy concept, but in a positive sense: the goals are more important than the approaches or means applied.

- It connects with other essential concepts, such as resilience, adaptive capacity, and vulnerability.

- Choices matter: "it is not possible to sustain everything, everywhere, forever"

- Scale matters in both space and time, and place matters

- Limits exist (see planetary boundaries).

In everyday usage, sustainability often focuses on the environmental dimension.[28]

Specific definitions

[edit]A single specific definition of sustainability may never be possible, but the concept is still useful.[25][24] There have been attempts to define it, for example:

- "Sustainability can be defined as the capacity to maintain or improve the state and availability of desirable materials or conditions over the long term."[24]

- "Sustainability [is] the long-term viability of a community, set of social institutions, or societal practice. In general, sustainability is understood as a form of intergenerational ethics in which the environmental and economic actions taken by present persons do not diminish the opportunities of future persons to enjoy similar levels of wealth, utility, or welfare."[7]

- "Sustainability means meeting our own needs without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs. In addition to natural resources, we also need social and economic resources. Sustainability is not just environmentalism. Embedded in most definitions of sustainability we also find concerns for social equity and economic development."[29]

Some definitions focus on the environmental dimension. The Oxford Dictionary of English defines sustainability as: "the property of being environmentally sustainable; the degree to which a process or enterprise is able to be maintained or continued while avoiding the long-term depletion of natural resources".[30]

Historical usage

[edit]The term sustainability is derived from the Latin word sustinere. "To sustain" can mean to maintain, support, uphold, or endure.[31][32] So sustainability is the ability to continue over a long period of time.

In the past, sustainability referred to environmental sustainability. It meant using natural resources so that people in the future could continue to rely on them in the long term.[33][34] The concept of sustainability, or Nachhaltigkeit in German, goes back to Hans Carl von Carlowitz (1645–1714), and applied to forestry. The term for this now would be sustainable forest management.[35] He used this term to mean the long-term responsible use of a natural resource. In his 1713 work Silvicultura oeconomica,[36] he wrote that "the highest art/science/industriousness [...] will consist in such a conservation and replanting of timber that there can be a continuous, ongoing and sustainable use".[37] The shift in use of "sustainability" from preservation of forests (for future wood production) to broader preservation of environmental resources (to sustain the world for future generations) traces to a 1972 book by Ernst Basler, based on a series of lectures at M.I.T.[38]

The idea itself goes back a long time: Communities have always worried about the capacity of their environment to sustain them in the long term. Many ancient cultures, traditional societies, and indigenous peoples have restricted the use of natural resources.[39]

Comparison to sustainable development

[edit]The terms sustainability and sustainable development are closely related. In fact, they are often used to mean the same thing.[7] Both terms are linked with the "three dimensions of sustainability" concept.[9] One distinction is that sustainability is a general concept, while sustainable development can be a policy or organizing principle. Scholars say sustainability is a broader concept because sustainable development focuses mainly on human well-being.[24]

Sustainable development has two linked goals. It aims to meet human development goals.[40] It also aims to enable natural systems to provide the natural resources and ecosystem services needed for economies and society. The concept of sustainable development has come to focus on economic development, social development and environmental protection for future generations.[41]

Dimensions

[edit]Development of three dimensions

[edit]

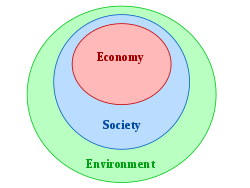

Scholars usually distinguish three different areas of sustainability. These are the environmental, the social, and the economic. Several terms are in use for this concept. Authors may speak of three pillars, dimensions, components, aspects,[42] perspectives, factors, or goals. All mean the same thing in this context.[9] The three dimensions paradigm has few theoretical foundations.[9]

The popular three intersecting circles, or Venn diagram, representing sustainability first appeared in a 1987 article by the economist Edward Barbier.[9][43]

Scholars rarely question the distinction itself. The idea of sustainability with three dimensions is a dominant interpretation in the literature.[9]

In the Brundtland Report, the environment and development are inseparable and go together in the search for sustainability. It described sustainable development as a global concept linking environmental and social issues. It added sustainable development is important for both developing countries and industrialized countries:

The 'environment' is where we all live; and 'development' is what we all do in attempting to improve our lot within that abode. The two are inseparable. [...] We came to see that a new development path was required, one that sustained human progress not just in a few pieces for a few years, but for the entire planet into the distant future. Thus 'sustainable development' becomes a goal not just for the 'developing' nations, but for industrial ones as well.

— Our Common Future (also known as the Brundtland Report), [26]: Foreword and Section I.1.10

The Rio Declaration from 1992 is seen as "the foundational instrument in the move towards sustainability".[44]: 29 It includes specific references to ecosystem integrity.[44]: 31 The plan associated with carrying out the Rio Declaration also discusses sustainability in this way. The plan, Agenda 21, talks about economic, social, and environmental dimensions:[45]: 8.6

Countries could develop systems for monitoring and evaluation of progress towards achieving sustainable development by adopting indicators that measure changes across economic, social and environmental dimensions.

Agenda 2030 from 2015 also viewed sustainability in this way. It sees the 17 Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) with their 169 targets as balancing "the three dimensions of sustainable development, the economic, social and environmental".[46]

Hierarchy

[edit]

Scholars have discussed how to rank the three dimensions of sustainability. Many publications state that the environmental dimension is the most important.[4][5] (Planetary integrity or ecological integrity are other terms for the environmental dimension.)

Protecting ecological integrity is the core of sustainability according to many experts.[5] If this is the case then its environmental dimension sets limits to economic and social development.[5]

The diagram with three nested ellipses is one way of showing the three dimensions of sustainability together with a hierarchy: It gives the environmental dimension a special status. In this diagram, the environment includes society, and society includes economic conditions. Thus it stresses a hierarchy.

This nested hierarchy has led some scholars and Indigenous thinkers to call for decentering the human in sustainability discourse, arguing that ecological systems should not merely be valued for their utility to humans but as interdependent life systems with intrinsic worth.[49]

Another model shows the three dimensions in a similar way: In this SDG wedding cake model, the economy is a smaller subset of the societal system. And the societal system in turn is a smaller subset of the biosphere system.[48]

In 2022 an assessment examined the political impacts of the Sustainable Development Goals. The assessment found that the "integrity of the earth's life-support systems" was essential for sustainability.[4]: 140 The authors said that "the SDGs fail to recognize that planetary, people and prosperity concerns are all part of one earth system, and that the protection of planetary integrity should not be a means to an end, but an end in itself".[4]: 147 The aspect of environmental protection is not an explicit priority for the SDGs. This causes problems as it could encourage countries to give the environment less weight in their developmental plans.[4]: 144 The authors state that "sustainability on a planetary scale is only achievable under an overarching Planetary Integrity Goal that recognizes the biophysical limits of the planet".[4]: 161

Other frameworks bypass the compartmentalization of sustainability into separate dimensions completely.[9]

Environmental sustainability

[edit]

The environmental dimension is central to the overall concept of sustainability. People became more and more aware of environmental pollution in the 1960s and 1970s. This led to discussions on sustainability and sustainable development. This process began in the 1970s with concern for environmental issues. These included natural ecosystems or natural resources and the human environment. It later extended to all systems that support life on Earth, including human society.[50]: 31 Reducing these negative impacts on the environment would improve environmental sustainability.[50][51]

Environmental pollution is not a new phenomenon. But it has been only a local or regional concern for most of human history. Awareness of global environmental issues increased in the 20th century.[50]: 5 [52] The harmful effects and global spread of pesticides like DDT came under scrutiny in the 1960s.[53] In the 1970s it emerged that chlorofluorocarbons (CFCs) were depleting the ozone layer. This led to the de facto ban of CFCs with the Montreal Protocol in 1987.[6]: 146

In the early 20th century, Arrhenius discussed the effect of greenhouse gases on the climate (see also: history of climate change science).[54] Climate change due to human activity became an academic and political topic several decades later. This led to the establishment of the IPCC in 1988 and the UNFCCC in 1992.

In 1972, the UN Conference on the Human Environment took place. It was the first UN conference on environmental issues. It stated it was important to protect and improve the human environment.[55]: 3 It emphasized the need to protect wildlife and natural habitats:[55]: 4

The natural resources of the earth, including the air, water, land, flora and fauna and [...] natural ecosystems must be safeguarded for the benefit of present and future generations through careful planning or management, as appropriate.

— UN Conference on the Human Environment, [55]: p.4., Principle 2

In 2000, the UN launched eight Millennium Development Goals. The aim was for the global community to achieve them by 2015. Goal 7 was to "ensure environmental sustainability". But this goal did not mention the concepts of social or economic sustainability.[9]

Specific problems often dominate public discussion of the environmental dimension of sustainability: In the 21st century these problems have included climate change, biodiversity and pollution. Other global problems are loss of ecosystem services, land degradation, environmental impacts of animal agriculture and air and water pollution, including marine plastic pollution and ocean acidification.[56][57] Many people worry about human impacts on the environment. These include impacts on the atmosphere, land, and water resources.[50]: 21

Human activities now have an impact on Earth's geology and ecosystems. This led Paul Crutzen to call the current geological epoch the Anthropocene.[58]

The importance of citizens in accomplishing climate change adaptation, mitigation, and more general sustainable development objectives is being emphasized more and more by urban climate change governance (Hegger, Mees, & Wamsler, 2022).[59] The Sustainable Development Goals and the Glasgow Climate Pact are two recent international agreements that acknowledge that sustainability transformations depend on both individual and social attitudes, values, and behaviors in addition to technical solutions (IPCC, 2022; Wamsler et al., 2021).[59] Through their roles as voters, activists, consumers, and community members—particularly in decision-making, information co-production, and localized self-governance initiatives—citizens are seen as crucial change agents (Mees et al., 2016; Wamsler, 2017).[59]

Economic sustainability

[edit]The economic dimension of sustainability is controversial.[9] This is because the term development within sustainable development can be interpreted in different ways. Some may take it to mean only economic development and growth. This can promote an economic system that is bad for the environment.[60][61][62] Others focus more on the trade-offs between environmental conservation and achieving welfare goals for basic needs (food, water, health, and shelter).[10]

Economic development can indeed reduce hunger or energy poverty, especially in the least developed countries. That is why Sustainable Development Goal 8 calls for economic growth to drive social progress and well-being, where indicators include real GDP per capita growth.[63] However, the challenge is to expand economic activities while reducing their environmental impact.[12]: 8 In other words, humanity will have to find ways how societal progress (potentially by economic development) can be reached without excess strain on the environment.

The Brundtland report says poverty causes environmental problems. Poverty also results from them. So addressing environmental problems requires understanding the factors behind world poverty and inequality.[26]: Section I.1.8 The report demands a new development path for sustained human progress. It highlights that this is a goal for both developing and industrialized nations.[26]: Section I.1.10

UNEP and UNDP launched the Poverty-Environment Initiative in 2005 which has three goals. These are reducing extreme poverty, greenhouse gas emissions, and net natural asset loss. This guide to structural reform will enable countries to achieve the SDGs.[64][65]: 11 It should also show how to address the trade-offs between ecological footprint and economic development.[6]: 82

The government debt increases of many countries were found unsustainable in the long-term.[66]

Social sustainability

[edit]

The social dimension of sustainability is not well defined.[67][68][69] One definition states that a society is sustainable in social terms if people do not face structural obstacles in key areas. These key areas are health, influence, competence, impartiality and meaning-making.[70]

Some scholars place social issues at the very center of discussions.[71] They suggest that all the domains of sustainability are social. These include ecological, economic, political, and cultural sustainability. These domains all depend on the relationship between the social and the natural. The ecological domain is defined as human embeddedness in the environment. From this perspective, social sustainability encompasses all human activities.[72] It goes beyond the intersection of economics, the environment, and the social.[73]

There are many broad strategies for more sustainable social systems. They include improved education and the political empowerment of women. This is especially the case in developing countries. They include greater regard for social justice. This involves equity between rich and poor both within and between countries. And it includes intergenerational equity.[74] Providing more social safety nets to vulnerable populations would contribute to social sustainability.[75]: 11 Current pension systems are financially unsustainable in some countries.[76]

A society with a high degree of social sustainability would lead to livable communities with a good quality of life (being fair, diverse, connected and democratic).[77]

Indigenous communities might have a focus on particular aspects of sustainability, for example spiritual aspects, community-based governance and an emphasis on place and locality.[78]

Another aspect of social sustainability would be gender equity. According to reports from the United Nations and various research studies, women are disproportionately affected by climate related issues and sustainability efforts than men are.[79] To name a few, natural disasters, carbon taxes, and public transportation expansions have all reportedly had unequal consequences on women and other marginalized groups by making it harder for them to afford different goods and services or newer transit routes (longer car rides equate to more gas purchases), as well as putting them at risk of becoming targets of violence.[79]

These issues often go unaddressed and unheard, as women do not have the ability to voice these concerns due to the little to nonexistent presence of women in environmental policymaking. Despite the contrast in ability, women are often given the responsibility of solving the issues of climate change more than men are, due to the stereotypical feminine aspect of caring for the planet.[79] For this reason, scholars urge the need for more female representation and leadership in environmental politics and policymaking. They also highlight the link between environmental and social sustainability and the importance of addressing the two together so that actual progress can be made, as policymakers often categorize and handle them separately. By improving healthcare, education, and representation in government, women will be empowered to have a voice in policy making.[80]

Proposed additional dimensions

[edit]Some experts have proposed further dimensions. These could cover institutional, cultural, political, and technical dimensions.[9]

Cultural sustainability

[edit]Some scholars have argued for a fourth dimension. They say the traditional three dimensions do not reflect the complexity of contemporary society.[81] For example, Agenda 21 for culture and the United Cities and Local Governments argue that sustainable development should include a solid cultural policy. They also advocate for a cultural dimension in all public policies. Another example was the Circles of Sustainability approach, which included cultural sustainability.[82]

Interactions between dimensions

[edit]Environmental and economic dimensions

[edit]People often debate the relationship between the environmental and economic dimensions of sustainability.[83] In academia, this is discussed under the term weak and strong sustainability. In that model, the weak sustainability concept states that capital made by humans could replace most of the natural capital.[84][83] Natural capital is a way of describing environmental resources. People may refer to it as nature. An example for this is the use of environmental technologies to reduce pollution.[85]

The opposite concept in that model is strong sustainability. This assumes that nature provides functions that technology cannot replace.[86] Thus, strong sustainability acknowledges the need to preserve ecological integrity.[6]: 19 The loss of those functions makes it impossible to recover or repair many resources and ecosystem services. Biodiversity, along with pollination and fertile soils, are examples. Others are clean air, clean water, and regulation of climate systems.

Weak sustainability has come under criticism. It may be popular with governments and business but does not ensure the preservation of the earth's ecological integrity.[87] This is why the environmental dimension is so important.[5]

The World Economic Forum illustrated this in 2020. It found that $44 trillion of economic value generation depends on nature. This value, more than half of the world's GDP, is thus vulnerable to nature loss.[88]: 8 Three large economic sectors are highly dependent on nature: construction, agriculture, and food and beverages. Nature loss results from many factors. They include land use change, sea use change and climate change. Other examples are natural resource use, pollution, and invasive alien species.[88]: 11

Trade-offs

[edit]Trade-offs between different dimensions of sustainability are a common topic for debate. Balancing the environmental, social, and economic dimensions of sustainability is difficult. This is because there is often disagreement about the relative importance of each. To resolve this, there is a need to integrate, balance, and reconcile the dimensions.[9] For example, humans can choose to make ecological integrity a priority or to compromise it.[5]

Some even argue the Sustainable Development Goals are unrealistic. Their aim of universal human well-being conflicts with the physical limits of Earth and its ecosystems.[22]: 41

Measurement tools

[edit]

Environmental impacts of humans

[edit]There are several methods to measure or describe human impacts on Earth. They include the ecological footprint, ecological debt, carrying capacity, and sustainable yield. The idea of planetary boundaries is that there are limits to the carrying capacity of the Earth. It is important not to cross these thresholds to prevent irreversible harm to the Earth.[96][97] These planetary boundaries involve several environmental issues. These include climate change and biodiversity loss. They also include types of pollution. These are biogeochemical (nitrogen and phosphorus), ocean acidification, land use, freshwater, ozone depletion, atmospheric aerosols, and chemical pollution.[96][98] (Since 2015 some experts refer to biodiversity loss as change in biosphere integrity. They refer to chemical pollution as introduction of novel entities.)

The IPAT formula measures the environmental impact of humans. It emerged in the 1970s. It states this impact is proportional to human population, affluence and technology.[99] This implies various ways to increase environmental sustainability. One would be human population control. Another would be to reduce consumption and affluence[100] such as energy consumption. Another would be to develop innovative or green technologies such as renewable energy. In other words, there are two broad aims. The first would be to have fewer consumers. The second would be to have less environmental footprint per consumer.

The Millennium Ecosystem Assessment from 2005 measured 24 ecosystem services. It concluded that only four have improved over the last 50 years. It found 15 are in serious decline and five are in a precarious condition.[101]: 6–19

Economic costs

[edit]

Experts in environmental economics have calculated the cost of using public natural resources. One project calculated the damage to ecosystems and biodiversity loss. This was the Economics of Ecosystems and Biodiversity project from 2007 to 2011.[102]

An entity that creates environmental and social costs often does not pay for them. The market price also does not reflect those costs. In the end, government policy is usually required to resolve this problem.[103]

Decision-making can take future costs and benefits into account. The tool for this is the social discount rate. The bigger the concern for future generations, the lower the social discount rate should be.[104] Another approach is to put an economic value on ecosystem services. This allows us to assess environmental damage against perceived short-term welfare benefits. One calculation is that, "for every dollar spent on ecosystem restoration, between three and 75 dollars of economic benefits from ecosystem goods and services can be expected".[105]

In recent years, economist Kate Raworth has developed the concept of doughnut economics. This aims to integrate social and environmental sustainability into economic thinking. The social dimension acts as a minimum standard to which a society should aspire. The carrying capacity of the planet acts an outer limit.[106]

Barriers

[edit]There are many reasons why sustainability is so difficult to achieve. These reasons have the name sustainability barriers.[6][17] Before addressing these barriers it is important to analyze and understand them.[6]: 34 Some barriers arise from nature and its complexity ("everything is related").[24] Others arise from the human condition. One example is the value-action gap. This reflects the fact that people often do not act according to their convictions. Experts describe these barriers as intrinsic to the concept of sustainability.[107]: 81

Other barriers are extrinsic to the concept of sustainability. This means it is possible to overcome them. One way would be to put a price tag on the consumption of public goods.[107]: 84 Some extrinsic barriers relate to the nature of dominant institutional frameworks. Examples would be where market mechanisms fail for public goods. Existing societies, economies, and cultures encourage increased consumption. There is a structural imperative for growth in competitive market economies. This inhibits necessary societal change.[100]

Furthermore, there are several barriers related to the difficulties of implementing sustainability policies. There are trade-offs between the goals of environmental policies and economic development. Environmental goals include nature conservation. Development may focus on poverty reduction.[17][6]: 65 There are also trade-offs between short-term profit and long-term viability.[107]: 65 Political pressures generally favor the short term over the long term. So they form a barrier to actions oriented toward improving sustainability.[107]: 86

Barriers to sustainability may also reflect current trends. These could include consumerism and short-termism.[107]: 86

Conflicts, lack of international cooperation are also considered as a barrier to achieve sustainability.[108][109] 61 scientists, including Michael Meeropol, Don Trent Jacobs and 24 organizations including Scientist Rebellion endorsed an appeal saying we can not stop the ecological crisis without stopping overconsumption and this is impossible as wars continue because GDP is directly linked to military potential.[110]

Transition

[edit]Characteristics

[edit]Sustainability transformation (or transition), though not universally defined, refers to a deep, system-wide change affecting technology, economy, society, values, and goals. It is a complex and multi-layered process that must happen at all scales, from local communities to global governance institutions.[111] However, it is often politically debated, as different stakeholders may disagree on both the goals and the methods of change. Additionally, such transformations can challenge existing power structures and resource distribution.[112]

A sustainability transition requires major change in societies. They must change their fundamental values and organizing principles.[50]: 15 These new values would emphasize "the quality of life and material sufficiency, human solidarity and global equity, and affinity with nature and environmental sustainability".[50]: 15 A transition may only work if far-reaching lifestyle changes accompany technological advances.[100]

Scientists have pointed out that: "Sustainability transitions come about in diverse ways, and all require civil-society pressure and evidence-based advocacy, political leadership, and a solid understanding of policy instruments, markets, and other drivers."[57]

There are four possible overlapping processes of transformation. They each have different political dynamics. Technology, markets, government, or citizens can lead these processes.[23]

The European Environment Agency defines a sustainability transition as "a fundamental and wide-ranging transformation of a socio-technical system towards a more sustainable configuration that helps alleviate persistent problems such as climate change, pollution, biodiversity loss or resource scarcities."[113]: 152 The concept of sustainability transitions is similar to the concept of energy transitions.[114]

One expert argues a sustainability transition must be "supported by a new kind of culture, a new kind of collaboration, [and] a new kind of leadership".[115] It requires a large investment in "new and greener capital goods, while simultaneously shifting capital away from unsustainable systems".[22]: 107

In 2024 an interdisciplinary group of experts including Chip Fletcher, William J. Ripple, Phoebe Barnard, Kamanamaikalani Beamer, Christopher Field, David Karl, David King, Michael E. Mann and Naomi Oreskes advocated for a paradigm shift toward genuine sustainability and resource regeneration. They said that "such a transformation is imperative to reverse the tide of biodiversity loss due to overconsumption and to reinstate the security of food and water supplies, which are foundational for the survival of global populations."[116]

Principles

[edit]It is possible to divide action principles to make societies more sustainable into four types. These are nature-related, personal, society-related and systems-related principles.[6]: 206

- Nature-related principles: decarbonize; reduce human environmental impact by efficiency, sufficiency and consistency; be net-positive – build up environmental and societal capital; prefer local, seasonal, plant-based and labor-intensive; polluter-pays principle; precautionary principle; and appreciate and celebrate the beauty of nature.

- Personal principles: practise contemplation, apply policies with caution, celebrate frugality.

- Society-related principles: grant the least privileged the greatest support; seek mutual understanding, trust and many wins; strengthen social cohesion and collaboration; engage stakeholders; foster education – share knowledge and collaborate.

- Systems-related principles: apply systems thinking; foster diversity; make what is relevant to the public more transparent; maintain or increase option diversity.

Example steps

[edit]There are many approaches that people can take to transition to environmental sustainability. These include maintaining ecosystem services, protecting and co-creating common resources, reducing food waste, and promoting dietary shifts towards plant-based foods.[117] Another is reducing population growth by cutting fertility rates. Others are promoting new green technologies, and adopting renewable energy sources while phasing out subsidies to fossil fuels.[57]

In 2017 scientists published an update to the 1992 World Scientists' Warning to Humanity. It showed how to move towards environmental sustainability. It proposed steps in three areas:[57]

- Reduced consumption: reducing food waste, promoting dietary shifts towards mostly plant-based foods.

- Reducing the number of consumers: further reducing fertility rates and thus population growth.

- Technology and nature conservation: there are several related approaches. One is to maintain nature's ecosystem services. Another is promote new green technologies. Another is changing energy use. One aspect of this is to adopt renewable energy sources. At the same time it is necessary to end subsidies to energy production through fossil fuels.

Agenda 2030 for the Sustainable Development Goals

[edit]

In 2015, the United Nations agreed the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). Their official name is Agenda 2030 for the Sustainable Development Goals. The UN described this programme as a very ambitious and transformational vision. It said the SDGs were of unprecedented scope and significance.[46]: 3/35

The UN said: "We are determined to take the bold and transformative steps which are urgently needed to shift the world on to a sustainable and resilient path."[46]

The 17 goals and targets lay out transformative steps. For example, the SDGs aim to protect the future of planet Earth. The UN pledged to "protect the planet from degradation, including through sustainable consumption and production, sustainably managing its natural resources and taking urgent action on climate change, so that it can support the needs of the present and future generations".[46]

Options for overcoming barriers

[edit]Issues around economic growth

[edit]

Eco-economic decoupling is an idea to resolve tradeoffs between economic growth and environmental conservation. The idea is to "decouple environmental bads from economic goods as a path towards sustainability".[13] This would mean "using less resources per unit of economic output and reducing the environmental impact of any resources that are used or economic activities that are undertaken".[12]: 8 The intensity of pollutants emitted makes it possible to measure pressure on the environment. This in turn makes it possible to measure decoupling. This involves following changes in the emission intensity associated with economic output.[12] Examples of absolute long-term decoupling are rare. But some industrialized countries have decoupled GDP growth from production- and consumption-based CO2 emissions.[118] Yet, even in this example, decoupling alone is not enough. It is necessary to accompany it with "sufficiency-oriented strategies and strict enforcement of absolute reduction targets".[118]: 1

One study in 2020 found no evidence of necessary decoupling. This was a meta-analysis of 180 scientific studies. It found that there is "no evidence of the kind of decoupling needed for ecological sustainability" and that "in the absence of robust evidence, the goal of decoupling rests partly on faith".[13] Some experts have questioned the possibilities for decoupling and thus the feasibility of green growth.[14] Some have argued that decoupling on its own will not be enough to reduce environmental pressures. They say it would need to include the issue of economic growth.[14] There are several reasons why adequate decoupling is currently not taking place. These are rising energy expenditure, rebound effects, problem shifting, the underestimated impact of services, the limited potential of recycling, insufficient and inappropriate technological change, and cost-shifting.[14]

The decoupling of economic growth from environmental deterioration is difficult. This is because the entity that causes environmental and social costs does not generally pay for them. So the market price does not express such costs.[103] For example, the cost of packaging into the price of a product. may factor in the cost of packaging. But it may omit the cost of disposing of that packaging. Economics describes such factors as externalities, in this case a negative externality.[119] Usually, it is up to government action or local governance to deal with externalities.[120]

For highly developed nations, sustainable practices and climate policies "often lead to conflicts between short-term economic interests and long-term environmental goals." However, for developing countries, efforts to address climate change are limited by their financial resources.[121] To effectively advance sustainability, solutions need to focus on "fostering political commitment, enhancing inter-agency coordination, securing adequate funding, and engaging diverse stakeholders to overcome these challenges."[121]

There are various ways to incorporate environmental and social costs and benefits into economic activities. Examples include: taxing the activity (the polluter pays); subsidizing activities with positive effects (rewarding stewardship); and outlawing particular levels of damaging practices (legal limits on pollution).[103]

Government action and local governance

[edit]A textbook on natural resources and environmental economics stated in 2011: "Nobody who has seriously studied the issues believes that the economy's relationship to the natural environment can be left entirely to market forces."[122]: 15 This means natural resources will be over-exploited and destroyed in the long run without government action.

Elinor Ostrom (winner of the 2009 Nobel Prize in Economics) expanded on this. She stated that local governance (or self-governance) can be a third option besides the market or the national government.[123] She studied how people in small, local communities manage shared natural resources.[124] She showed that communities using natural resources can establish rules their for use and maintenance. These are resources such as pastures, fishing waters, and forests. This leads to both economic and ecological sustainability.[123] Successful self-governance needs groups with frequent communication among participants. In this case, groups can manage the usage of common goods without overexploitation.[6]: 117 Based on Ostrom's work, some have argued that: "Common-pool resources today are overcultivated because the different agents do not know each other and cannot directly communicate with one another."[6]: 117

Global governance

[edit]

Questions of global concern are difficult to tackle. That is because global issues need global solutions. But existing global organizations (UN, WTO, and others) do not have sufficient means.[6]: 135 For example, they lack sanctioning mechanisms to enforce existing global regulations.[6]: 136 Some institutions do not enjoy universal acceptance. An example is the International Criminal Court. Their agendas are not aligned (for example UNEP, UNDP, and WTO) And some accuse them of nepotism and mismanagement.[6]: 135–145

Multilateral international agreements, treaties, and intergovernmental organizations (IGOs) face further challenges. These result in barriers to sustainability. Often these arrangements rely on voluntary commitments. An example is Nationally Determined Contributions for climate action. There can be a lack of enforcement of existing national or international regulation. And there can be gaps in regulation for international actors such as multi-national enterprises. Critics of some global organizations say they lack legitimacy and democracy. Institutions facing such criticism include the WTO, IMF, World Bank, UNFCCC, G7, G8 and OECD.[6]: 135

Sustainable Democracy and Pluralism

[edit]When ways to achieve sustainability remain limited only to those which are based on extraction and endless growth, it is difficult to reach the target. Other methodes are mostly not represented in global mechanisms for achieving sustainability. Allowing different ways of thinking to shape sustainability practices, can help overcome this barrier.[125]

Responses by nongovernmental stakeholders

[edit]Businesses

[edit]

Sustainable business practices integrate ecological concerns with social and economic ones.[18][19] One accounting framework for this approach uses the phrase "people, planet, and profit". The name of this approach is the triple bottom line. The circular economy is a related concept. Its goal is to decouple environmental pressure from economic growth.[126][127]

Growing attention towards sustainability has led to the formation of many organizations. These include the Sustainability Consortium of the Society for Organizational Learning,[128] the Sustainable Business Institute,[129] and the World Business Council for Sustainable Development.[130] Supply chain sustainability looks at the environmental and human impacts of products in the supply chain. It considers how they move from raw materials sourcing to production, storage, and delivery, and every transportation link on the way.[131]

Religious communities

[edit]Religious leaders have stressed the importance of caring for nature and environmental sustainability. In 2015 over 150 leaders from various faiths issued a joint statement to the UN Climate Summit in Paris 2015.[132] They reiterated a statement made in the Interfaith Summit in New York in 2014:

As representatives from different faith and religious traditions, we stand together to express deep concern for the consequences of climate change on the earth and its people, all entrusted, as our faiths reveal, to our common care. Climate change is indeed a threat to life, a precious gift we have received and that we need to care for.[133]

Individuals

[edit]Individuals can also live in a more sustainable way. They can change their lifestyles, practise ethical consumerism, and embrace frugality.[6]: 236 These sustainable living approaches can also make cities more sustainable. They do this by altering the built environment.[134] Such approaches include sustainable transport, sustainable architecture, and zero emission housing. Research can identify the main issues to focus on. These include flying, meat and dairy products, car driving, and household sufficiency. Research can show how to create cultures of sufficiency, care, solidarity, and simplicity.[100]

Some young people are using activism, litigation, and on-the-ground efforts to advance sustainability. This is particularly the case in the area of climate action.[75]: 60

Assessments and reactions

[edit]Impossible to reach

[edit]Scholars have criticized the concepts of sustainability and sustainable development from different angles. One was Dennis Meadows, one of the authors of the first report to the Club of Rome, called "The Limits to Growth". He argued many people deceive themselves by using the Brundtland definition of sustainability.[60] This is because the needs of the present generation are actually not met today. Instead, economic activities to meet present needs will shrink the options of future generations.[135][6]: 27 Another criticism is that the paradigm of sustainability is no longer suitable as a guide for transformation. This is because societies are "socially and ecologically self-destructive consumer societies".[136]

Some scholars have even proclaimed the end of the concept of sustainability. This is because humans now have a significant impact on Earth's climate system and ecosystems.[21] It might become impossible to pursue sustainability because of these complex, radical, and dynamic issues.[21] Others have called sustainability a utopian ideal: "We need to keep sustainability as an ideal; an ideal which we might never reach, which might be utopian, but still a necessary one."[6]: 5

Vagueness

[edit]The term is often hijacked and thus can lose its meaning. People use it for all sorts of things, such as saving the planet to recycling your rubbish.[30] A specific definition may never be possible. This is because sustainability is a concept that provides a normative structure. That describes what human society regards as good or desirable.[25]

But some argue that while sustainability is vague and contested it is not meaningless.[25] Although lacking in a singular definition, this concept is still useful. Scholars have argued that its fuzziness can actually be liberating. This is because it means that "the basic goal of sustainability (maintaining or improving desirable conditions [...]) can be pursued with more flexibility".[24]

Confusion and greenwashing

[edit]Sustainability has a reputation as a buzzword.[9] People may use the terms sustainability and sustainable development in ways that are different to how they are usually understood. This can result in confusion and mistrust. So a clear explanation of how the terms are being used in a particular situation is important.[24]

Greenwashing is a practice of deceptive marketing. It is when a company or organization provides misleading information about the sustainability of a product, policy, or other activity.[75]: 26 [137] Investors are wary of this issue as it exposes them to risk.[138] The reliability of eco-labels is also doubtful in some cases.[139] Ecolabelling is a voluntary method of environmental performance certification and labelling for food and consumer products. The most credible eco-labels are those developed with close participation from all relevant stakeholders.[140]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Harper, Douglas. "sustain". Online Etymology Dictionary.

- ^ Onions, Charles, T. (ed) (1964). The Shorter Oxford English Dictionary. Oxford: Clarendon Press. p. 2095.

- ^ Purvis, Ben; Mao, Yong; Robinson, Darren (3 September 2018). "Three pillars of sustainability: in search of conceptual origins". Sustainability Science. 14 (3): 681–695. doi:10.1007/s11625-018-0627-5. Retrieved 3 September 2025.

- ^ a b c d e f Kotzé, Louis J.; Kim, Rakhyun E.; Burdon, Peter; du Toit, Louise; Glass, Lisa-Maria; Kashwan, Prakash; Liverman, Diana; Montesano, Francesco S.; Rantala, Salla (2022). "Planetary Integrity". In Sénit, Carole-Anne; Biermann, Frank; Hickmann, Thomas (eds.). The Political Impact of the Sustainable Development Goals: Transforming Governance Through Global Goals?. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 140–171. doi:10.1017/9781009082945.007. ISBN 978-1-316-51429-0.

- ^ a b c d e f Bosselmann, Klaus (2010). "Losing the Forest for the Trees: Environmental Reductionism in the Law". Sustainability. 2 (8): 2424–2448. Bibcode:2010Sust....2.2424B. doi:10.3390/su2082424. hdl:10535/6499. ISSN 2071-1050.

Text was copied from this source, which is available under a Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 International License

Text was copied from this source, which is available under a Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 International License

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u Berg, Christian (2020). Sustainable action: overcoming the barriers. Abingdon, Oxon: Routledge. ISBN 978-0-429-57873-1. OCLC 1124780147.

- ^ a b c "Sustainability". Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved 31 March 2022.

- ^ "Sustainable Development". UNESCO. 3 August 2015. Retrieved 20 January 2022.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o Purvis, Ben; Mao, Yong; Robinson, Darren (2019). "Three pillars of sustainability: in search of conceptual origins". Sustainability Science. 14 (3): 681–695. Bibcode:2019SuSc...14..681P. doi:10.1007/s11625-018-0627-5. ISSN 1862-4065.

Text was copied from this source, which is available under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License

Text was copied from this source, which is available under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License

- ^ a b Kuhlman, Tom; Farrington, John (2010). "What is Sustainability?". Sustainability. 2 (11): 3436–3448. Bibcode:2010Sust....2.3436K. doi:10.3390/su2113436. ISSN 2071-1050.

- ^ Nelson, Anitra (31 January 2024). "Degrowth as a Concept and Practice: Introduction". The Commons Social Change Library. Retrieved 23 February 2024.

- ^ a b c d UNEP (2011) Decoupling natural resource use and environmental impacts from economic growth, A Report of the Working Group on Decoupling to the International Resource Panel. Fischer-Kowalski, M., Swilling, M., von Weizsäcker, E.U., Ren, Y., Moriguchi, Y., Crane, W., Krausmann, F., Eisenmenger, N., Giljum, S., Hennicke, P., Romero Lankao, P., Siriban Manalang, A., Sewerin, S.

- ^ a b c Vadén, T.; Lähde, V.; Majava, A.; Järvensivu, P.; Toivanen, T.; Hakala, E.; Eronen, J.T. (2020). "Decoupling for ecological sustainability: A categorisation and review of research literature". Environmental Science & Policy. 112: 236–244. Bibcode:2020ESPol.112..236V. doi:10.1016/j.envsci.2020.06.016. PMC 7330600. PMID 32834777.

- ^ a b c d Parrique T., Barth J., Briens F., C. Kerschner, Kraus-Polk A., Kuokkanen A., Spangenberg J.H., 2019. Decoupling debunked: Evidence and arguments against green growth as a sole strategy for sustainability. European Environmental Bureau.

- ^ Hardyment, Richard (2024). Measuring Good Business: Making Sense of Environmental, Social & Governance Data. Abingdon: Routledge. ISBN 978-1-032-60119-9.

- ^ Bell, Simon; Morse, Stephen (2012). Sustainability Indicators: Measuring the Immeasurable?. Abington: Routledge. ISBN 978-1-84407-299-6.

- ^ a b c Howes, Michael; Wortley, Liana; Potts, Ruth; Dedekorkut-Howes, Aysin; Serrao-Neumann, Silvia; Davidson, Julie; Smith, Timothy; Nunn, Patrick (2017). "Environmental Sustainability: A Case of Policy Implementation Failure?". Sustainability. 9 (2): 165. Bibcode:2017Sust....9..165H. doi:10.3390/su9020165. hdl:10453/90953. ISSN 2071-1050.

- ^ a b Kinsley, M. and Lovins, L.H. (September 1997). "Paying for Growth, Prospering from Development." Archived 17 July 2011 at the Wayback Machine Retrieved 15 June 2009.

- ^ a b Sustainable Shrinkage: Envisioning a Smaller, Stronger Economy Archived 11 April 2016 at the Wayback Machine. Thesolutionsjournal.com. Retrieved 13 March 2016.

- ^ Apetrei, Cristina I.; Caniglia, Guido; von Wehrden, Henrik; Lang, Daniel J. (1 May 2021). "Just another buzzword? A systematic literature review of knowledge-related concepts in sustainability science". Global Environmental Change. 68 102222. Bibcode:2021GEC....6802222A. doi:10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2021.102222. ISSN 0959-3780.

- ^ a b c Benson, Melinda Harm; Craig, Robin Kundis (2014). "End of Sustainability". Society & Natural Resources. 27 (7): 777–782. Bibcode:2014SNatR..27..777B. doi:10.1080/08941920.2014.901467. ISSN 0894-1920. S2CID 67783261.

- ^ a b c Stockholm+50: Unlocking a Better Future. Stockholm Environment Institute (Report). 18 May 2022. doi:10.51414/sei2022.011. S2CID 248881465.

- ^ a b Scoones, Ian (2016). "The Politics of Sustainability and Development". Annual Review of Environment and Resources. 41 (1): 293–319. doi:10.1146/annurev-environ-110615-090039. ISSN 1543-5938. S2CID 156534921.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Harrington, Lisa M. Butler (2016). "Sustainability Theory and Conceptual Considerations: A Review of Key Ideas for Sustainability, and the Rural Context". Papers in Applied Geography. 2 (4): 365–382. Bibcode:2016PAGeo...2..365H. doi:10.1080/23754931.2016.1239222. ISSN 2375-4931. S2CID 132458202.

- ^ a b c d Ramsey, Jeffry L. (2015). "On Not Defining Sustainability". Journal of Agricultural and Environmental Ethics. 28 (6): 1075–1087. Bibcode:2015JAEE...28.1075R. doi:10.1007/s10806-015-9578-3. ISSN 1187-7863. S2CID 146790960.

- ^ a b c d United Nations General Assembly (1987) Report of the World Commission on Environment and Development: Our Common Future. Transmitted to the General Assembly as an Annex to document A/42/427 – Development and International Co-operation: Environment.

- ^ United Nations General Assembly (20 March 1987). "Report of the World Commission on Environment and Development: Our Common Future; Transmitted to the General Assembly as an Annex to document A/42/427 – Development and International Co-operation: Environment; Our Common Future, Chapter 2: Towards Sustainable Development; Paragraph 1". United Nations General Assembly. Retrieved 1 March 2010.

- ^ Altanlar, Ali; Özdemir, Zeynep (2025). "A scale development study on the perception of the sustainable urban environment". International Journal of Environmental Science and Technology. 22 (5): 3111–3128. Bibcode:2025JEST...22.3111A. doi:10.1007/s13762-024-05914-z.

- ^ "University of Alberta: What is sustainability?" (PDF). mcgill.ca. Retrieved 13 August 2022.

- ^ a b Halliday, Mike (21 November 2016). "How sustainable is sustainability?". Oxford College of Procurement and Supply. Retrieved 12 July 2022.

- ^ Harper, Douglas. "sustain". Online Etymology Dictionary.

- ^ Onions, Charles, T. (ed) (1964). The Shorter Oxford English Dictionary. Oxford: Clarendon Press. p. 2095.

- ^ "Sustainability Theories". World Ocean Review. Retrieved 20 June 2019.

- ^ Compare: "sustainability". Oxford English Dictionary (Online ed.). Oxford University Press. (Subscription or participating institution membership required.) The English-language word had a legal technical sense from 1835 and a resource-management connotation from 1953.

- ^ "Hans Carl von Carlowitz and Sustainability". Environment and Society Portal. Retrieved 20 June 2019.

- ^ Dresden, SLUB. "Sylvicultura Oeconomica, Oder Haußwirthliche Nachricht und Naturmäßige Anweisung Zur Wilden Baum-Zucht". digital.slub-dresden.de (in German). Retrieved 28 March 2022.

- ^ Von Carlowitz, H.C. & Rohr, V. (1732) Sylvicultura Oeconomica, oder Haußwirthliche Nachricht und Naturmäßige Anweisung zur Wilden Baum Zucht, Leipzig; translated from German as cited in Friederich, Simon; Symons, Jonathan (15 November 2022). "Operationalising sustainability? Why sustainability fails as an investment criterion for safeguarding the future". Global Policy. 14: 1758–5899.13160. doi:10.1111/1758-5899.13160. ISSN 1758-5880. S2CID 253560289.

- ^ Basler, Ernst (1972). Strategy of Progress: Environmental Pollution, Habitat Scarcity and Future Research (originally, Strategie des Fortschritts: Umweltbelastung Lebensraumverknappung and Zukunftsforshung). BLV Publishing Company.

- ^ Gadgil, M.; Berkes, F. (1991). "Traditional Resource Management Systems". Resource Management and Optimization. 8: 127–141.

- ^ Zhang, Yixin; Wu, Zhijie (10 September 2022). "Environmental performance and human development for sustainability: Towards to a new Environmental Human Index". Science of the Total Environment. 838 (Pt 4) 156491. Bibcode:2022ScTEn.83856491Z. doi:10.1016/j.scitotenv.2022.156491. ISSN 0048-9697. PMID 35667422.

- ^ "Sustainable development: conditions, principles and issues(BP-458E)". publications.gc.ca. Retrieved 30 April 2025.

- ^ "Resolution adopted by the General Assembly on 16 September 2005, 60/1. 2005 World Summit Outcome" (PDF). United Nations General Assembly. 2005. Retrieved 17 January 2022.

- ^ Barbier, Edward B. (July 1987). "The Concept of Sustainable Economic Development". Environmental Conservation. 14 (2): 101–110. Bibcode:1987EnvCo..14..101B. doi:10.1017/S0376892900011449. ISSN 1469-4387.

- ^ a b Bosselmann, K. (2022) Chapter 2: A normative approach to environmental governance: sustainability at the apex of environmental law, Research Handbook on Fundamental Concepts of Environmental Law, edited by Douglas Fisher

- ^ a b "Agenda 21" (PDF). United Nations Conference on Environment & Development, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, 3 to 14 June 1992. 1992. Retrieved 17 January 2022.

- ^ a b c d United Nations (2015) Resolution adopted by the General Assembly on 25 September 2015, Transforming our world: the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development (A/RES/70/1 Archived 28 November 2020 at the Wayback Machine)

- ^ Scott Cato, M. (2009). Green Economics. London: Earthscan, pp. 36–37. ISBN 978-1-84407-571-3.

- ^ a b Obrecht, Andreas; Pham-Truffert, Myriam; Spehn, Eva; Payne, Davnah; Altermatt, Florian; Fischer, Manuel; Passarello, Cristian; Moersberger, Hannah; Schelske, Oliver; Guntern, Jodok; Prescott, Graham (5 February 2021). "Achieving the SDGs with Biodiversity". Swiss Academies Factsheet. Vol. 16, no. 1. doi:10.5281/zenodo.4457298.

- ^ Tran, T.M.A., Reed-VanDam, C., Belopavlovich, K. et al. Decentering humans in sustainability: a framework for Earth-centered kinship and practice. Socio Ecol Pract Res 7, 43–55 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1007/s42532-024-00206-9

- ^ a b c d e f Raskin, P.; Banuri, T.; Gallopín, G.; Gutman, P.; Hammond, A.; Kates, R.; Swart, R. (2002). Great transition: the promise and lure of the times ahead. Boston: Stockholm Environment Institute. ISBN 0-9712418-1-3. OCLC 49987854.

- ^ Ekins, Paul; Zenghelis, Dimitri (2021). "The costs and benefits of environmental sustainability". Sustainability Science. 16 (3): 949–965. Bibcode:2021SuSc...16..949E. doi:10.1007/s11625-021-00910-5. PMC 7960882. PMID 33747239.

- ^ William L. Thomas, ed. (1956). Man's role in changing the face of the earth. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. ISBN 0-226-79604-3. OCLC 276231.

{{cite book}}: ISBN / Date incompatibility (help) - ^ Carson, Rachel (2002) [1st. Pub. Houghton Mifflin, 1962]. Silent Spring. Mariner Books. ISBN 978-0-618-24906-0.

- ^ Arrhenius, Svante (1896). "XXXI. On the influence of carbonic acid in the air upon the temperature of the ground". The London, Edinburgh, and Dublin Philosophical Magazine and Journal of Science. 41 (251): 237–276. doi:10.1080/14786449608620846. ISSN 1941-5982.

- ^ a b c UN (1973) Report of the United Nations Conference on the Human Environment, A/CONF.48/14/Rev.1, Stockholm, 5–16 June 1972

- ^ UNEP (2021). "Making Peace With Nature". UNEP – UN Environment Programme. Retrieved 30 March 2022.

- ^ a b c d Ripple, William J.; Wolf, Christopher; Newsome, Thomas M.; Galetti, Mauro; Alamgir, Mohammed; Crist, Eileen; Mahmoud, Mahmoud I.; Laurance, William F.; 15,364 scientist signatories from 184 countries (2017). "World Scientists' Warning to Humanity: A Second Notice". BioScience. 67 (12): 1026–1028. doi:10.1093/biosci/bix125. hdl:11336/71342. ISSN 0006-3568.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ Crutzen, Paul J. (2002). "Geology of mankind". Nature. 415 (6867): 23. Bibcode:2002Natur.415...23C. doi:10.1038/415023a. ISSN 0028-0836. PMID 11780095. S2CID 9743349.

- ^ a b c Hegger, Dries L. T.; Mees, Heleen L. P.; Wamsler, Christine (2022). "The role of citizens in sustainability and climate change governance: Taking stock and looking ahead". Environmental Policy and Governance. 32 (3): 161–166. Bibcode:2022EnvPG..32..161H. doi:10.1002/eet.1990. hdl:1874/422514. ISSN 1756-9338.

- ^ a b Wilhelm Krull, ed. (2000). Zukunftsstreit (in German). Weilerwist: Velbrück Wissenschaft. ISBN 3-934730-17-5. OCLC 52639118.

- ^ Redclift, Michael (2005). "Sustainable development (1987-2005): an oxymoron comes of age". Sustainable Development. 13 (4): 212–227. doi:10.1002/sd.281. ISSN 0968-0802.

- ^ Daly, Herman E. (1996). Beyond growth: the economics of sustainable development (PDF). Boston: Beacon Press. ISBN 0-8070-4708-2. OCLC 33946953.

- ^ United Nations (2017) Resolution adopted by the General Assembly on 6 July 2017, Work of the Statistical Commission pertaining to the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development (A/RES/71/313)

- ^ "UN Environment | UNDP-UN Environment Poverty-Environment Initiative". UN Environment | UNDP-UN Environment Poverty-Environment Initiative. Retrieved 24 January 2022.

- ^ PEP (2016) Poverty-Environment Partnership Joint Paper | June 2016 Getting to Zero – A Poverty, Environment and Climate Call to Action for the Sustainable Development Goals

- ^ Beqiraj, Elton; Fedeli, Silvia; Forte, Francesco (2018). "Public debt sustainability: An empirical study on OECD countries". Journal of Macroeconomics. 58: 238–248. doi:10.1016/j.jmacro.2018.10.002. ISSN 0164-0704.

- ^ Boyer, Robert H. W.; Peterson, Nicole D.; Arora, Poonam; Caldwell, Kevin (2016). "Five Approaches to Social Sustainability and an Integrated Way Forward". Sustainability. 8 (9): 878. Bibcode:2016Sust....8..878B. doi:10.3390/su8090878.

- ^ Doğu, Feriha Urfalı; Aras, Lerzan (2019). "Measuring Social Sustainability with the Developed MCSA Model: Güzelyurt Case". Sustainability. 11 (9): 2503. Bibcode:2019Sust...11.2503D. doi:10.3390/su11092503. ISSN 2071-1050.

- ^ Davidson, Mark (2010). "Social Sustainability and the City: Social sustainability and city". Geography Compass. 4 (7): 872–880. doi:10.1111/j.1749-8198.2010.00339.x.

- ^ Missimer, Merlina; Robèrt, Karl-Henrik; Broman, Göran (2017). "A strategic approach to social sustainability – Part 2: a principle-based definition". Journal of Cleaner Production. 140: 42–52. Bibcode:2017JCPro.140...42M. doi:10.1016/j.jclepro.2016.04.059.

- ^ Boyer, Robert; Peterson, Nicole; Arora, Poonam; Caldwell, Kevin (2016). "Five Approaches to Social Sustainability and an Integrated Way Forward". Sustainability. 8 (9): 878. Bibcode:2016Sust....8..878B. doi:10.3390/su8090878. ISSN 2071-1050.

- ^ James, Paul; with Magee, Liam; Scerri, Andy; Steger, Manfred B. (2015). Urban Sustainability in Theory and Practice: Circles of Sustainability. London: Routledge. ISBN 978-1-315-76574-7.

- ^ Liam Magee; Andy Scerri; Paul James; James A. Thom; Lin Padgham; Sarah Hickmott; Hepu Deng; Felicity Cahill (2013). "Reframing social sustainability reporting: Towards an engaged approach". Environment, Development and Sustainability. 15 (1): 225–243. Bibcode:2013EDSus..15..225M. doi:10.1007/s10668-012-9384-2. S2CID 153452740.

- ^ Cohen, J. E. (2006). "Human Population: The Next Half Century.". In Kennedy, D. (ed.). Science Magazine's State of the Planet 2006-7. London: Island Press. pp. 13–21. ISBN 978-1-59726-624-6.

- ^ a b c Aggarwal, Dhruvak; Esquivel, Nhilce; Hocquet, Robin; Martin, Kristiina; Mungo, Carol; Nazareth, Anisha; Nikam, Jaee; Odenyo, Javan; Ravindran, Bhuvan; Kurinji, L. S.; Shawoo, Zoha; Yamada, Kohei (28 April 2022). Charting a youth vision for a just and sustainable future (PDF) (Report). Stockholm Environment Institute. doi:10.51414/sei2022.010.

- ^ Jimon, Stefania Amalia; Dumiter, Florin Cornel; Baltes, Nicolae (2021). "Financial Sustainability of Pension Systems". Financial and Monetary Policy Studies. doi:10.1007/978-3-030-74454-0. ISSN 0921-8580.

- ^ "The Regional Institute – WACOSS Housing and Sustainable Communities Indicators Project". www.regional.org.au. 2012. Retrieved 26 January 2022.

- ^ Virtanen, Pirjo Kristiina; Siragusa, Laura; Guttorm, Hanna (2020). "Introduction: toward more inclusive definitions of sustainability". Current Opinion in Environmental Sustainability. 43: 77–82. Bibcode:2020COES...43...77V. doi:10.1016/j.cosust.2020.04.003. S2CID 219663803.

- ^ a b c "We Can't Fight Climate Change Without Fighting for Gender Equity". Harvard Business Review. 26 July 2022. ISSN 0017-8012. Retrieved 8 May 2025.

- ^ Hailemariam, Abebe; Kalsi, Jaslin Kaur; Mavisakalyan, Astghik (2021). "Climate Change and Gender Equality". The Palgrave Handbook of Global Social Problems. Cham: Springer International Publishing. pp. 1–15. doi:10.1007/978-3-030-68127-2_237-1. ISBN 978-3-030-68127-2. Retrieved 13 May 2025.

- ^ "Culture: Fourth Pillar of Sustainable Development". United Cities and Local Governments. Archived from the original on 3 October 2013.

- ^ James, Paul; Magee, Liam (2016). "Domains of Sustainability". In Farazmand, Ali (ed.). Global Encyclopedia of Public Administration, Public Policy, and Governance. Cham: Springer International Publishing. pp. 1–17. doi:10.1007/978-3-319-31816-5_2760-1. ISBN 978-3-319-31816-5. Retrieved 28 March 2022.

- ^ a b Robert U. Ayres & Jeroen C.J.M. van den Bergh & John M. Gowdy, 1998. "Viewpoint: Weak versus Strong Sustainability", Tinbergen Institute Discussion Papers 98-103/3, Tinbergen Institute.

- ^ Pearce, David W.; Atkinson, Giles D. (1993). "Capital theory and the measurement of sustainable development: an indicator of "weak" sustainability". Ecological Economics. 8 (2): 103–108. Bibcode:1993EcoEc...8..103P. doi:10.1016/0921-8009(93)90039-9.

- ^ Ayres, Robert; van den Berrgh, Jeroen; Gowdy, John (2001). "Strong versus Weak Sustainability". Environmental Ethics. 23 (2): 155–168. Bibcode:2001EnEth..23..155A. doi:10.5840/enviroethics200123225. ISSN 0163-4275.

- ^ Cabeza Gutés, Maite (1996). "The concept of weak sustainability". Ecological Economics. 17 (3): 147–156. Bibcode:1996EcoEc..17..147C. doi:10.1016/S0921-8009(96)80003-6.

- ^ Bosselmann, Klaus (2017). The principle of sustainability: transforming law and governance (2nd ed.). London: Routledge. ISBN 978-1-4724-8128-3. OCLC 951915998.

- ^ a b WEF (2020) Nature Risk Rising: Why the Crisis Engulfing Nature Matters for Business and the Economy New Nature Economy, World Economic Forum in collaboration with PwC

- ^ James, Paul; with Magee, Liam; Scerri, Andy; Steger, Manfred B. (2015). Urban Sustainability in Theory and Practice: Circles of Sustainability. London: Routledge. ISBN 978-1-315-76574-7.

- ^ a b Hardyment, Richard (2 February 2024). Measuring Good Business. London: Routledge. doi:10.4324/9781003457732. ISBN 978-1-003-45773-2.

- ^ a b Bell, Simon and Morse, Stephen 2008. Sustainability Indicators. Measuring the Immeasurable? 2nd edn. London: Earthscan. ISBN 978-1-84407-299-6.

- ^ Dalal-Clayton, Barry and Sadler, Barry 2009. Sustainability Appraisal: A Sourcebook and Reference Guide to International Experience. London: Earthscan. ISBN 978-1-84407-357-3.[page needed]

- ^ Hak, T. et al. 2007. Sustainability Indicators, SCOPE 67. Island Press, London. [1] Archived 2011-12-18 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Wackernagel, Mathis; Lin, David; Evans, Mikel; Hanscom, Laurel; Raven, Peter (2019). "Defying the Footprint Oracle: Implications of Country Resource Trends". Sustainability. 11 (7): 2164. doi:10.3390/su11072164.

- ^ "Sustainable Development visualized". Sustainability concepts. Retrieved 24 March 2022.

- ^ a b Steffen, Will; Rockström, Johan; Cornell, Sarah; Fetzer, Ingo; Biggs, Oonsie; Folke, Carl; Reyers, Belinda (15 January 2015). "Planetary Boundaries – an update". Stockholm Resilience Centre. Retrieved 19 April 2020.

- ^ "Ten years of nine planetary boundaries". Stockholm Resilience Centre. November 2019. Retrieved 19 April 2020.

- ^ Persson, Linn; Carney Almroth, Bethanie M.; Collins, Christopher D.; Cornell, Sarah; de Wit, Cynthia A.; Diamond, Miriam L.; Fantke, Peter; Hassellöv, Martin; MacLeod, Matthew; Ryberg, Morten W.; Søgaard Jørgensen, Peter (1 February 2022). "Outside the Safe Operating Space of the Planetary Boundary for Novel Entities". Environmental Science & Technology. 56 (3): 1510–1521. Bibcode:2022EnST...56.1510P. doi:10.1021/acs.est.1c04158. ISSN 0013-936X. PMC 8811958. PMID 35038861.

- ^ Ehrlich, P.R.; Holden, J.P. (1974). "Human Population and the global environment". American Scientist. Vol. 62, no. 3. pp. 282–292.

- ^ a b c d Wiedmann, Thomas; Lenzen, Manfred; Keyßer, Lorenz T.; Steinberger, Julia K. (2020). "Scientists' warning on affluence". Nature Communications. 11 (1): 3107. Bibcode:2020NatCo..11.3107W. doi:10.1038/s41467-020-16941-y. ISSN 2041-1723. PMC 7305220. PMID 32561753.

Text was copied from this source, which is available under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License

Text was copied from this source, which is available under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License

- ^ Millennium Ecosystem Assessment (2005). Ecosystems and Human Well-being: Biodiversity Synthesis (PDF). Washington, DC: World Resources Institute.

- ^ TEEB (2010), The Economics of Ecosystems and Biodiversity: Mainstreaming the Economics of Nature: A Synthesis of the Approach, Conclusions and Recommendations of TEEB

- ^ a b c Jaeger, William K. (2005). Environmental economics for tree huggers and other skeptics. Washington, DC: Island Press. ISBN 978-1-4416-0111-7. OCLC 232157655.

- ^ Groth, Christian (2014). Lecture notes in Economic Growth, (mimeo), Chapter 8: Choice of social discount rate. Copenhagen University.

- ^ "UNEP, FAO (2020). UN Decade on Ecosystem Restoration. 48p" (PDF).

- ^ Raworth, Kate (2017). Doughnut economics: seven ways to think like a 21st-century economist. London: Random House. ISBN 978-1-84794-138-1. OCLC 974194745.

- ^ a b c d e Berg, Christian (2017). "Shaping the Future Sustainably – Types of Barriers and Tentative Action Principles (chapter in: Future Scenarios of Global Cooperation—Practices and Challenges)". Global Dialogues (14). Centre For Global Cooperation Research (KHK/GCR21), Nora Dahlhaus and Daniela Weißkopf (eds.). doi:10.14282/2198-0403-GD-14. ISSN 2198-0403.

- ^ Adkins, Madalyn. "The Link Between Peace and Sustainable Development". ADEC ESG. Retrieved 25 June 2025.

- ^ Virji, Hassan; Sharifi, Ayyoob; Kaneko, Shinji; Simangan, Dahlia (10 October 2019). "The sustainability–peace nexus in the context of global change". Sustainability Science. 14. Retrieved 25 June 2025.

- ^ "Prominent climate scientists, activists: to stop the climate crisis, first stop wars and change the system". Extinction Rebellion Tunisia. Retrieved 11 June 2025.

- ^ Pastor-Escuredo, David. "Multiscale Governance". Research Gate. Retrieved 12 May 2025.

- ^ Pickering, Jonathan; Hickmann, Thomas; Bäckstrand, Karin; Kalfagianni, Agni; Bloomfield, Michael; Mert, Ayşem; Ransan-Cooper, Hedda; Lo, Alex Y. (2022). "Democratising sustainability transformations: Assessing the transformative potential of democratic practices in environmental governance". Earth System Governance. 11 100131. Bibcode:2022ESGov..1100131P. doi:10.1016/j.esg.2021.100131.

Text was copied from this source, which is available under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License

Text was copied from this source, which is available under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License

- ^ European Environment Agency. (2019). Sustainability transitions: policy and practice. LU: Publications Office. doi:10.2800/641030. ISBN 978-92-9480-086-2.

- ^ Noura Guimarães, Lucas (2020). "Introduction". The regulation and policy of Latin American energy transitions. Elsevier. pp. xxix–xxxviii. doi:10.1016/b978-0-12-819521-5.00026-7. ISBN 978-0-12-819521-5. S2CID 241093198.

- ^ Kuenkel, Petra (2019). Stewarding Sustainability Transformations: An Emerging Theory and Practice of SDG Implementation. Cham: Springer. ISBN 978-3-030-03691-1. OCLC 1080190654.

- ^ Fletcher, Charles; Ripple, William J.; Newsome, Thomas; Barnard, Phoebe; Beamer, Kamanamaikalani; Behl, Aishwarya; Bowen, Jay; Cooney, Michael; Crist, Eileen; Field, Christopher; Hiser, Krista; Karl, David M.; King, David A.; Mann, Michael E.; McGregor, Davianna P.; Mora, Camilo; Oreskes, Naomi; Wilson, Michael (4 April 2024). "Earth at risk: An urgent call to end the age of destruction and forge a just and sustainable future". PNAS Nexus. 3 (4) pgae106. doi:10.1093/pnasnexus/pgae106. PMC 10986754. PMID 38566756. Retrieved 4 April 2024.

Text was copied from this source, which is available under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License

Text was copied from this source, which is available under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License

- ^ Smith, E. T. (23 January 2024). "Practising Commoning". The Commons Social Change Library. Retrieved 23 February 2024.

- ^ a b Haberl, Helmut; Wiedenhofer, Dominik; Virág, Doris; Kalt, Gerald; Plank, Barbara; Brockway, Paul; Fishman, Tomer; Hausknost, Daniel; Krausmann, Fridolin; Leon-Gruchalski, Bartholomäus; Mayer, Andreas (2020). "A systematic review of the evidence on decoupling of GDP, resource use and GHG emissions, part II: synthesizing the insights". Environmental Research Letters. 15 (6): 065003. Bibcode:2020ERL....15f5003H. doi:10.1088/1748-9326/ab842a. ISSN 1748-9326. S2CID 216453887.

- ^ Pigou, Arthur Cecil (1932). The Economics of Welfare (PDF) (4th ed.). London: Macmillan.

- ^ Jaeger, William K. (2005). Environmental economics for tree huggers and other skeptics. Washington, DC: Island Press. ISBN 978-1-4416-0111-7. OCLC 232157655.

- ^ a b Suprayitno D, Iskandar S, Dahurandi K, Hendarto T, Rumambi FJ. Public Policy In The Era Of Climate Change: Adapting Strategies For Sustainable Futures. Migration Letters. 2024;21(S6):945-58.

- ^ Roger Perman; Yue Ma; Michael Common; David Maddison; James Mcgilvray (2011). Natural resource and environmental economics (4th ed.). Harlow, Essex: Pearson Addison Wesley. ISBN 978-0-321-41753-4. OCLC 704557307.

- ^ a b Anderies, John M.; Janssen, Marco A. (16 October 2012). "Elinor Ostrom (1933–2012): Pioneer in the Interdisciplinary Science of Coupled Social-Ecological Systems". PLOS Biology. 10 (10) e1001405. doi:10.1371/journal.pbio.1001405. ISSN 1544-9173. PMC 3473022.

- ^ "The Nobel Prize: Women Who Changed the World". thenobelprize.org. Retrieved 31 March 2022.

- ^ J.Salovaara, Janne; E.Hagolany-Albov, Sophia (October 2025). "A greener future cannot be bought: On the paradoxes of practising contemporary consumption-driven sustainability". Elsevier. Retrieved 20 October 2025.

- ^ Ghisellini, Patrizia; Cialani, Catia; Ulgiati, Sergio (15 February 2016). "A review on circular economy: the expected transition to a balanced interplay of environmental and economic systems". Journal of Cleaner Production. Towards Post Fossil Carbon Societies: Regenerative and Preventative Eco-Industrial Development. 114: 11–32. Bibcode:2016JCPro.114...11G. doi:10.1016/j.jclepro.2015.09.007. ISSN 0959-6526.

- ^ Nobre, Gustavo Cattelan; Tavares, Elaine (10 September 2021). "The quest for a circular economy final definition: A scientific perspective". Journal of Cleaner Production. 314 127973. Bibcode:2021JCPro.31427973N. doi:10.1016/j.jclepro.2021.127973. ISSN 0959-6526.

- ^ Zhexembayeva, N. (May 2007). "Becoming Sustainable: Tools and Resources for Successful Organizational Transformation". Center for Business as an Agent of World Benefit. Case Western University. Archived from the original on 13 June 2010.

- ^ "About Us". Sustainable Business Institute. Archived from the original on 17 May 2009.

- ^ "About the WBCSD". World Business Council for Sustainable Development (WBCSD). Archived from the original on 9 September 2007. Retrieved 1 April 2009.

- ^ "Supply Chain Sustainability | UN Global Compact". www.unglobalcompact.org. Retrieved 4 May 2022.

- ^ ""Statement of Faith and Spiritual Leaders on the upcoming United Nations Climate Change Conference, COP21 in Paris in December 2015"" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 22 December 2015. Retrieved 21 March 2022.

- ^ "The Statement — Interfaith Climate". www.interfaithclimate.org. Retrieved 13 August 2022.

- ^ McDilda, Diane Gow (2007). The everything green living book: easy ways to conserve energy, protect your family's health, and help save the environment. Avon, Mass.: Adams Media. ISBN 978-1-59869-425-3. OCLC 124074971.

- ^ Gambino, Megan (15 March 2012). "Is it Too Late for Sustainable Development?". Smithsonian Magazine. Retrieved 12 January 2022.