Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Arabic maqam

View on Wikipedia| Part of a series on |

| Islamic culture |

|---|

| Part of a series on |

| Arabic culture |

|---|

|

In traditional Arabic music, maqam (Arabic: مقام, romanized: maqām, literally "ascent"; pl. مقامات maqāmāt) is the system of melodic modes, which is mainly melodic. The word maqam in Arabic means place, location or position. The Arabic maqam is a melody type. It is "a technique of improvisation" that defines the pitches, patterns, and development of a piece of music and is "unique to Arabic art music".[1] There are 72 heptatonic tone rows or scales of maqamat.[1] These are constructed from augmented, major, neutral, and minor seconds.[1] Each maqam is built on a scale, and carries a tradition that defines its habitual phrases, important notes, melodic development and modulation. Both compositions and improvisations in traditional Arabic music are based on the maqam system. Maqamat can be realized with either vocal or instrumental music, and do not include a rhythmic component.

An essential factor in performance is that each maqam describes the "tonal-spatial factor" or set of musical notes and the relationships between them, including traditional patterns and development of melody, while the "rhythmic-temporal component" is "subjected to no definite organization".[2] A maqam does not have an "established, regularly recurring bar scheme nor an unchanging meter. A certain rhythm does sometimes identify the style of a performer, but this is dependent upon their performance technique and is never characteristic of the maqam as such."[2] The compositional or rather precompositional aspect of the maqam is the tonal-spatial organization, including the number of tone levels, and the improvisational aspect is the construction of the rhythmic-temporal scheme.[2]

Background

[edit]The designation maqam appeared for the first time in the treatises written in the fourteenth century by al-Sheikh al-Safadi and Abdulqadir al-Maraghi, and has since been used as a technical term in Arabic music. The maqam is a modal structure that characterizes the art of music of countries in North Africa, the Near East and Central Asia. Three main musical cultures belong to the maqam modal family: Arabic, Persian, and Turkish.

Tuning system

[edit]The notes of a maqam are not always tuned in equal temperament, meaning that the frequency ratios of successive pitches are not necessarily identical. A maqam also determines other things, such as the tonic (starting note), the ending note, and the dominant note. It also determines which notes should be emphasized and which should not.[3]

Arabic maqamat are based on a musical scale of 7 notes that repeats at the octave. Some maqamat have 2 or more alternative scales (e.g. Rast, Nahawand and Hijaz). Maqam scales in traditional Arabic music are microtonal, not based on a twelve-tone equal-tempered musical tuning system, as is the case in modern Western music. Most maqam scales include a perfect fifth or a perfect fourth (or both), and all octaves are perfect. The remaining notes in a maqam scale may or may not exactly land on semitones. For this reason maqam scales are mostly taught orally, and by extensive listening to the traditional Arabic music repertoire.

Notation

[edit]Since accurately notating every possible microtonal interval is impractical, a simplified musical notation system was adopted in Arabic music at the turn of the 20th century. Starting with a chromatic scale, the octave is divided into 24 equal steps (24 equal temperament), where a quarter tone equals one-half of a semitone in a 12 tone equally-tempered scale. In this notation system all notes in a maqam are rounded to the nearest quarter tone.

This system of notation is not exact since it eliminates many details, but is very practical because it allows maqamat to be notated using standard Western notation. Quarter tones can be notated using half-flats (![]() or

or ![]() ) or half-sharps (

) or half-sharps (![]() ). When transcribed with this notation system some maqam scales happen to include quarter tones, while others don't.

). When transcribed with this notation system some maqam scales happen to include quarter tones, while others don't.

In practice, maqamat are not performed in all chromatic keys, and are more rigid to transpose than scales in Western music, primarily because of the technical limitations of Arabic instruments. For this reason, half-sharps rarely occur in maqam scales, and the most used half-flats are E![]() , B

, B![]() and less frequently A

and less frequently A![]() .

.

Intonation

[edit]The 24-tone system is entirely a notational convention and does not affect the actual precise intonation of the notes performed. Practicing Arab musicians, while using the nomenclature of the 24-tone system (half-flats and half-sharps), often still perform the finer microtonal details which have been passed down through oral tradition to this day.

Maqamat that do not include quarter tones (e.g. Nahawand, ‘Ajam) can be performed on equal-tempered instruments such as the piano, however such instruments cannot faithfully reproduce the microtonal details of the maqam scale. Maqamat can be faithfully performed either on fretless instruments (e.g. the oud or the violin), or on instruments that allow a sufficient degree of tunability and microtonal control (e.g. the nay, the qanun, or the clarinet). On fretted instruments with steel strings, microtonal control can be achieved by string bending, as when playing blues.

The exact intonation of every maqam changes with the historical period, as well as the geographical region (as is the case with linguistic accents, for example). For this reason, and because it is not common to notate precisely and accurately microtonal variations from a twelve-tone equal tempered scale, maqamat are mostly learned auditorally in practice.

Phases and central tones

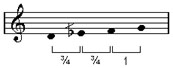

[edit]Each passage consists of one or more phases that are sections "played on one tone or within one tonal area," and may take from seven to forty seconds to articulate. For example, a tone level centered on g:[4]

The tonal levels, or axial pitches, begin in the lower register and gradually rise to the highest at the climax before descending again, for example (in European-influenced notation):[5]

"When all possibilities of the musical structuring of such a tone level have been fully explored, the phase is complete."[5]

Nucleus

[edit]The central tones of a maqam are created from two different intervals. The eleven central tones of the maqam used in the phase sequence example above may be reduced to three, which make up the "nucleus" of the maqam:[6]

The tone rows of maqamat may be identical, such as maqam bayati and maqam 'ushshaq turki:[6]

but be distinguished by different nuclei. Bayati is shown in the example above, while 'ushshaq turki is:[6]

Ajnas

[edit]Maqamat are made up of smaller sets of consecutive notes that have a very recognizable melody and convey a distinctive mood. Such a set is called jins (Arabic: جنس; pl. ajnās أجناس), meaning "gender" or "kind". In most cases, a jins is made up of four consecutive notes (tetrachord), although ajnas of three consecutive notes (trichord) or five consecutive notes (pentachord) also exist. In addition to other exceptional ajnas of undefined sizes.

Ajnas are the building blocks of a maqam. A maqam scale has a lower (or first) jins and an upper (or second) jins. In most cases maqams are classified into families or branches based on their lower jins. The upper jins may start on the ending note of the lower jins or on the note following that. In some cases the upper and lower ajnas may overlap. The starting note of the upper jins is called the dominant, and is the second most important note in that scale after the tonic. Maqam scales often include secondary ajnas that start on notes other than the tonic or the dominant. Secondary ajnas are highlighted in the course of modulation.

References on Arabic music theory often differ on the classification of ajnas. There is no consensus on a definitive list of all ajnas, their names or their sizes. However the majority of references agree on the basic 9 ajnas, which also make up the main 9 maqam families. The following is the list of the basic 9 ajnas notated with Western standard notation (all notes are rounded to the nearest quarter tone):

‘Ajam (عجم) trichord, starting on B♭ |

Bayati (بياتي) tetrachord, starting on D |

Hijaz (حجاز) tetrachord, starting on D |

Kurd (كرد) tetrachord, starting on D |

Nahawand (نهاوند) tetrachord, starting on C |

Nikriz (نكريز) pentachord, starting on C |

Rast (راست) tetrachord, starting on C |

Saba (صبا) tetrachord, starting on D |

Sikah (سيكاه) trichord, starting on E |

(for more detail see Arabic Maqam Ajnas)

Maqam families

[edit]- ‘Ajam – Also The Major Scale ‘Ajam (عجم), Jiharkah (جهاركاه), Shawq Afza (شوق افزا or شوق أفزا), Ajam Ushayran (عجم عشيران)

- Bayati – Bayatayn (بیاتین), Bayati (بياتي), Bayati Shuri (بياتي شوري), Husayni (حسيني), Nahfat (نهفت), Huseini Ushayran (حسيني عشيران),

- Hijaz – Also The Phrygian Dominant Scale Hijaz (حجاز), Hijaz Kar (حجاز كار), Shad ‘Araban (شد عربان), Shahnaz (شهناز), Suzidil (سوزدل), Zanjaran (زنجران), Hijazain (حجازين)

- Kurd – Also the Phrygian Scale Kurd (كرد), Hijaz Kar Kurd (حجاز كار كرد), Lami (لامي)

- Nahawand – Also the Minor Scale Farahfaza (فرحفزا), Nahawand (نهاوند), Nahawand Murassah (نهاوند مرصّع or نهاوند مرصع), ‘Ushaq Masri (عشاق مصري), Sultani Yakah (سلطاني ياكاه)

- Nawa Athar – Athar Kurd (أثر كرد), Nawa Athar (نوى أثر or نوى اثر), Nikriz (نكريز), Hisar (حصار)

- Rast – Mahur (ماهور), Nairuz (نيروز), Rast (راست), Suznak (سوزناك), Yakah (يكاه)

- Saba – Saba (صبا), Saba Zamzam (صبا زمزم)

- Sikah – Bastah Nikar (بسته نكار), Huzam (هزام), ‘Iraq (عراق), Musta‘ar (مستعار), Rahat al-Arwah (راحة الأرواح), Sikah (سيكاه), Sikah Baladi (سيكاه بلدي)

Emotional content

[edit]It is sometimes said that each maqam evokes a specific emotion or set of emotions determined by the tone row and the nucleus, with different maqams sharing the same tone row but differing in nucleus and thus emotion. Maqam Rast is said to evoke pride, power, and soundness of mind.[7] Maqam Bayati: vitality, joy, and femininity.[7] Sikah: love.[7] Saba: sadness and pain.[8] Hijaz: distant desert.[7]

In an experiment where maqam Saba was played to an equal number of Arabs and non-Arabs who were asked to record their emotions in concentric circles with the weakest emotions in the outer circles, Arab subjects reported experiencing Saba as "sad", "tragic", and "lamenting", while only 48 percent of the non-Arabs described it thus with 28 percent of non-Arabs describing feelings such as "seriousness", "longing", and tension", and 6 percent experienced feelings such as "happy", "active", and "very lively" and 10 percent identified no feelings.[8]

These emotions are said to be evoked in part through change in the size of an interval during a maqam presentation. Maqam Saba, for example, contains in its first four notes, D, E![]() , F, and G♭, two medium seconds one larger (160 cents) and one smaller (140 cents) than a three quarter tone, and a minor second (95 cents). Further, E

, F, and G♭, two medium seconds one larger (160 cents) and one smaller (140 cents) than a three quarter tone, and a minor second (95 cents). Further, E![]() and G♭ may vary slightly, said to cause a "sad" or "sensitive" mood.[9]

and G♭ may vary slightly, said to cause a "sad" or "sensitive" mood.[9]

Generally speaking, each maqam is said to evoke a different emotion in the listener. At a more basic level, each jins is claimed to convey a different mood or color. For this reason maqams of the same family are said to share a common mood since they start with the same jins. There is no consensus on exactly what the mood of each maqam or jins is. Some references describe maqam moods using very vague and subjective terminology (e.g. maqams evoking 'love', 'femininity', 'pride' or 'distant desert'). However, there has not been any serious research using scientific methodology on a diverse sample of listeners (whether Arab or non-Arab) proving that they feel the same emotion when hearing the same maqam.

Attempting the same exercise in more recent tonal classical music would mean relating a mood to the major and minor modes. In that case there is some consensus that the minor scale is "sadder" and the major scale is "happier".[10]

Modulation

[edit]Modulation is a technique used during the melodic development of a maqam. In simple terms it means changing from one maqam to another (compatible or closely related) maqam. This involves using a new musical scale. A long musical piece can modulate over many maqamat but usually ends with the starting maqam (in rare cases the purpose of the modulation is to actually end with a new maqam). A more subtle form of modulation within the same maqam is to shift the emphasis from one jins to another so as to imply a new maqam.

Modulation adds a lot of interest to the music, and is present in almost every maqam-based melody. Modulations that are pleasing to the ear are created by adhering to compatible combinations of ajnas and maqamat long established in traditional Arabic music. Although such combinations are often documented in musical references, most experienced musicians learn them by extensive listening.

Influence around the world

[edit]During the Islamic golden age this system influenced musical systems in various places. An example is the influence it had on music in the Iberian peninsula during Muslim rule of Al-Andalus. Sephardic Jewish liturgy also follows the maqam system. The weekly maqam is chosen by the cantor based on the emotional state of the congregation or the weekly Torah reading. This variation is called the Weekly Maqam. There is also a notable influence of the Arabic maqam on the music of Sicily.[11]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b c Touma 1996, pp. 38, 203

- ^ a b c Touma 1996, p. 38

- ^ Touma 1996, pp. 38–39.

- ^ Touma 1996, p. 40.

- ^ a b Touma 1996, p. 41.

- ^ a b c Touma 1996, p. 42

- ^ a b c d Touma 1996, p. 43

- ^ a b Touma 1996, p. 44

- ^ Touma 1996, p. 45

- ^ Fritz, Thomas; Jentschke, Sebastian; Gosselin, Nathalie; Sammler, Daniela; Peretz, Isabelle; Turner, Robert; Friederici, Angela D.; Koelsch, Stefan (2009). "Universal Recognition of Three Basic Emotions in Music". Current Biology. 19 (7): 573–576. Bibcode:2009CBio...19..573F. doi:10.1016/j.cub.2009.02.058. PMID 19303300.

- ^ "Sicilia regional songs". www.italyheritage.com. Retrieved 2021-04-25.

Sources

- Touma, Habib Hassan (1996). The Music of the Arabs. Translated by Laurie Schwartz. Portland, Oregon: Amadeus Press. ISBN 0-931340-88-8.

Further reading

[edit]- el-Mahdi, Salah (1972). La musique arabe : structures, historique, organologie. Paris, France: Alphonse Leduc, Editions Musicales. ISBN 2-85689-029-6.

- Lagrange, Frédéric (1996). Musiques d'Égypte. Cité de la musique / Actes Sud. ISBN 2-7427-0711-5.

- Maalouf, Shireen (2002). History of Arabic music theory. Lebanon: Université Saint-Esprit de Kaslik. OCLC 52037253.

- Marcus, Scott Lloyd (1989). Arab music theory in the modern period (Ph.D. dissertation). Los Angeles: University of California. OCLC 20767535.

- Racy, Ali Jihad (2003). Making Music in the Arab World: The Culture and Artistry of Ṭarab. Publisher: Cambridge; New York: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-30414-8.

- Farraj, Johnny; Abu Shumays, Sami (2019). Inside Arabic Music. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0190658359.

External links

[edit]Arabic maqam

View on GrokipediaIntroduction and Background

Definition and Origins

The Arabic maqam is a system of melodic modes central to traditional Arabic music, characterized by specific scales, recurring motifs, and rules governing melodic progression and development. Unlike Western scales, which primarily define pitch sequences, the maqam emphasizes a framework for improvisation and composition through habitual phrases, key notes of emphasis, and modulation patterns, applicable to both vocal and instrumental performances without inherent rhythmic structures.[6] These modes are constructed from smaller melodic building blocks known as ajnas, providing the foundational elements for elaboration.[7] The term "maqam" originates from the Arabic word مَقَام (maqām), meaning "station," "place," or "position," which metaphorically represents the sequential "stations" or resting points in a melody's journey.[6] This etymology underscores the maqam's conceptual role as a pathway of melodic positions, guiding performers through structured yet flexible musical narratives.[8] The maqam system's origins lie in medieval Islamic music theory, particularly during the Abbasid era (750–1258 CE), where scholars formalized its structures amid a synthesis of regional traditions. Al-Farabi (c. 872–950 CE), a prominent philosopher and musician, played a pivotal role by integrating Greek theoretical principles into Arabic frameworks in his comprehensive treatise Kitab al-Musiqi al-Kabir, establishing foundational concepts for modal organization and tuning that influenced subsequent developments.[9] [10] Building on this, Safi al-Din al-Urmawi (1216–1294 CE) advanced the theory in works like Kitab al-Adwar and al-Risala al-Sharafiyya, classifying 18 maqams derived from combinations of tetrachords and pentachords within a 17-note system, providing one of the earliest systematic categorizations.[7] Early roots of the maqam trace to pre-Islamic Arabian traditions, particularly the melodic recitation of poetry in the Jahiliyyah period (c. 500–622 CE), where oral performances intertwined verse with musical intonation to convey tribal narratives and emotions.[6] These practices evolved into Islamic-era forms, including tajwid rules for Quranic recitation, which adopted similar modal inflections for expressive delivery.[11] Additionally, during the Abbasid period, Greek and Byzantine influences permeated Arabic music theory through translations of ancient texts by scholars like Aristotle and Ptolemy, acquired from Byzantine sources and adapted by figures such as Al-Farabi to enrich local modal systems.[9] [12]Historical Development

The maqam system emerged during the Golden Age of Islam (8th–13th centuries), a period of significant theoretical advancement in Arabic music, where scholars like al-Kindi (9th century) and al-Farabi (10th century) formalized modal structures and scales, building on earlier pre-Islamic traditions. Al-Urmawi (13th century) further refined these concepts in treatises that described maqams as melodic frameworks with specific intervals, including quartertones, influencing court music across the Abbasid Caliphate. By the 14th century, the term "maqam" was explicitly used by scholars such as Abdulqadir al-Maraghi, a Persian musician at the Ottoman court, to denote these modes, marking a shift toward systematic classification.[13][14][15] Integration into Ottoman and Persian courts during the 15th–18th centuries expanded maqam practices, blending Arabic modalities with local elements; Ottoman composers adapted maqams into fasıl suites for ensemble performance, while the related Persian dastgah systems influenced nomenclature and structure in regions like Baghdad and Istanbul. In the 19th century, as Ottoman influence waned, maqam theory spread through urban centers like Cairo, Damascus, and Istanbul, where Western military bands introduced tempered scales and notation, prompting initial standardization efforts amid nationalist revivals. Radio broadcasting from the 1920s and gramophone recordings in the 1930s–1950s further disseminated urban maqam styles, enabling cross-regional exchange but also homogenizing variations through commercial media.[4] Regional variations persisted despite standardization; Levantine maqams in Syria and Lebanon emphasized fluid improvisation and local ajnas (tetrachords), as seen in Damascus repertoires, while North African traditions, such as the Andalusian nuba in Tunisia and Algeria, structured maqams into multi-movement suites with Spanish-Arabic fusions dating to the medieval era. Gulf adaptations in the Arabian Peninsula incorporated bedouin rhythms and simpler scalar forms, reflecting nomadic influences. The 1932 Cairo Congress of Arab Music, convened by King Fuad I, aimed to preserve maqam authenticity against Westernization by documenting over 40 maqams and rejecting equal temperament in favor of traditional quartertones, though debates highlighted tensions between reform and tradition.[16][17][18] Post-colonial revivals in the mid-20th century, particularly after the 1940s independence movements, reinvigorated maqam through state-sponsored conservatories and festivals in Egypt, Syria, and Iraq, countering colonial-era Western influences with efforts to reclaim indigenous modalities; this "Golden Age" (1930–1970) saw performers like Umm Kulthum elevate maqam-based taqsim improvisation, blending preservation with modern orchestration.[19][20]Theoretical Foundations

Tuning System

The Arabic maqam tuning system relies on a microtonal framework that is often approximated in modern theory by a 24-tone equal temperament, dividing the octave into 24 equal steps of 50 cents each to facilitate notation and analysis. However, in performance practice, the system employs variable intervals derived primarily from Pythagorean and neutral tunings, allowing for subtle adjustments that reflect regional and contextual nuances rather than rigid equality. This approach traces back to medieval treatises, where theorists like al-Farabi (d. 950 CE) divided the octave into 25 unequal intervals using units such as the limma (approximately 90 cents) and the Pythagorean comma (about 24 cents), incorporating quarter-tone approximations like 1/4, 3/4, and 5/4 comma deviations for expressive flexibility.[21][22] Key intervals in maqam tuning include the whole tone, typically realized as the just ratio 9/8 (approximately 204 cents), providing a foundational step in many scales. The half-flat, or smaller neutral second, measures around 135 cents, creating a "half-flat" effect between the minor second (90 cents in Pythagorean terms) and the major second; conversely, the half-sharp, or larger neutral second, approaches 165 cents, enabling fluid transitions in melodic lines. The limma, a small semitone, is often tuned to the ratio 16/15 (about 112 cents), serving as a diatonic interval in tetrachord constructions. These intervals, including comma-based quarter tones, allow maqam to build ajnas—short melodic cells—on a pitch lattice that prioritizes harmonic consonance over equal division.[22][23] The fretless oud, a pear-shaped lute central to Arabic ensembles, serves as the primary reference instrument for realizing maqam tuning, its open strings often set in Pythagorean fourths and fifths (ratios 4/3 and 3/2) to anchor the scale while permitting microtonal slides and bends. Historical treatises, such as those by al-Urmawi (d. 1294 CE), explicitly advocated Pythagorean tuning for the oud's four double courses, dividing the octave into finer units like seventieth notes to approximate neutral thirds (e.g., the Wusta-Zalzal interval at 27/22, roughly 355 cents). This instrument's role underscores the system's emphasis on intuitive intonation over fixed pitches.[21] Unlike Western 12-tone equal temperament, which fixes intervals at 100-cent semitones for chromatic uniformity, maqam tuning eschews a strict 12-note framework, incorporating up to 24 or more variable tones per octave with context-dependent intonation that varies by maqam, performer, and regional tradition. This flexibility supports expressive modulation and ornamentation, avoiding the "stale" quality some performers associate with equal temperament, and instead fosters a dynamic pitch continuum attuned to the human voice.[21][22]Ajnas

In Arabic maqam theory, a jins (plural: ajnas) is defined as a foundational melodic unit, typically consisting of four successive notes spanning a perfect fourth, which acts as the core "seed" for constructing maqam scales.[24] These units are characterized by their specific interval patterns, often incorporating microtonal adjustments such as quarter tones, and they emphasize tonicization around key notes within the segment.[25] While ajnas can occasionally be trichords (three notes) or pentachords (five notes), the tetrachord form predominates as the modular building block, allowing for flexible assembly into larger melodic frameworks. Intonation of ajnas can vary by region and tradition, with extensions known as "jins baggage" allowing additional ornamental notes without forming a new jins.[26] Several common ajnas types recur across maqams, each with distinct interval structures that contribute to the system's melodic variety. The Hijaz jins, for example, features intervals of a semitone, an augmented second (tone and a half), and a semitone, as in the notes E-F-G♯-A.[27] The Nahawand jins is a pentachord with intervals of whole tone, semitone, whole tone, and whole tone, exemplified by C-D-E♭-F-G.[27] The Rast jins is a tetrachord with intervals of whole tone, semitone, whole tone, such as D-E-F-G, where the interval between the second and third degrees is a limma of approximately 90-112 cents.[24] Finally, the Bayati jins follows a tetrachord pattern of semitone, whole tone, and semitone, as seen in D-E♭-F-G, though performers may apply subtle quarter-tone inflections to the second degree for expressive nuance.[28] Ajnas combine according to established rules to form complete octave scales, typically by joining a lower jins (starting on the tonic) with an upper jins (beginning on the note shared with the lower jins' endpoint, often the fourth or fifth degree). This conjunction creates a heptatonic scale without overlap, adhering to the maqam's tonic and modulation points.[24] For instance, the Bayati maqam employs a Bayati jins on the root (e.g., D-E♭(half-flat)-F-G) combined with a Shuri jins (a variant of Hijaz) on the fourth degree (G-A(half-flat)-B♭-C), yielding the scale D-E♭(half-flat)-F-G-A(half-flat)-B♭-C-D.[29] Such pairings emphasize the ghammaz (a pivotal note signaling potential modulation) at the junction, ensuring melodic continuity.[25] Ajnas exhibit variations through transposition to different starting pitches, known as movable ajnas, which enable modulation and expansion beyond the initial scale while preserving the interval pattern.[24] This mobility, often guided by "jins baggage"—extensions of neighboring notes around the core segment without implying a new jins—fosters diversity in maqam pathways, allowing performers to navigate between related modes in improvisation or composition.[30] For example, a Hijaz jins transposed to the fifth degree can introduce tension and resolution in a Rast-based maqam, highlighting the system's combinatorial flexibility.[27]| Ajnas Type | Note Example | Interval Structure | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hijaz | E-F-G♯-A | Semitone, augmented second, semitone | Common for dramatic modulations.[27] |

| Nahawand | C-D-E♭-F-G | Whole, semitone, whole, whole | Pentachord resembling natural minor.[27] |

| Rast | D-E-F-G | Whole, semitone, whole | Diatonic-like; tetrachord resembling Ionian tetrachord.[24] |

| Bayati | D-E♭-F-G | Semitone, whole, semitone | Evokes introspective character; tetrachord with half-flat second degree.[28] |