Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Kriegsmarine

View on Wikipedia

| Kriegsmarine | |

|---|---|

Helmet decal of Kriegsmarine | |

| Founded | 21 May 1935 |

| Disbanded | 20 September 1945 |

| Country | |

| Allegiance | |

| Branch | Wehrmacht |

| Type | Navy |

| Size | 810,000 peak in 1944[2] 1,500,000 (total 1939–45) |

| Part of | Wehrmacht |

| Engagements | Spanish Civil War (1936–1939) World War II (1939–1945) |

| Commanders | |

| OKM | See list |

| Notable commanders | Erich Raeder Karl Dönitz |

| Insignia | |

| War ensign (1935–1938) |  |

| War ensign (1938–1945) |  |

| Land flag |  |

The Kriegsmarine (German pronunciation: [ˈkʁiːksmaˌʁiːnə], lit. 'War Navy') was the navy of Nazi Germany from 1935 to 1945. It superseded the Imperial German Navy of the German Empire (1871–1918) and the inter-war Reichsmarine (1919–1935) of the Weimar Republic. The Kriegsmarine was one of three official branches, along with the Heer and the Luftwaffe, of the Wehrmacht, the German armed forces from 1935 to 1945.

In violation of the Treaty of Versailles, the Kriegsmarine grew rapidly during the German naval rearmament in the 1930s. The 1919 treaty had limited the size of the German navy and prohibited the building of submarines.[3]

Kriegsmarine ships were deployed to the waters around Spain during the Spanish Civil War (1936–1939) under the guise of enforcing non-intervention, but in reality supporting the Nationalists against the Spanish Republicans.

In January 1939, Plan Z, a massive shipbuilding programme, was ordered, calling for surface naval parity with the British Royal Navy by 1944. When World War II broke out in September 1939, Plan Z was shelved in favour of a crash building programme for submarines (U-boats) instead of capital surface warships, and land and air forces were given priority of strategic resources.

The Commander-in-Chief of the Kriegsmarine (as for all branches of the armed forces during the period of absolute Nazi power) was Adolf Hitler, who exercised his authority through the Oberkommando der Marine ('High Command of the Navy').

Among the Kriegsmarine's most significant ships were its U-boats, most of which were constructed after Plan Z was abandoned at the beginning of World War II. Wolfpacks were rapidly assembled groups of submarines which attacked British convoys during the first half of the Battle of the Atlantic, but this tactic was largely abandoned by May 1943, when U-boat losses mounted. Along with the U-boats, surface commerce raiders (including auxiliary cruisers) were used to disrupt Allied shipping in the early years of the war, the most famous of these being the heavy cruisers Admiral Graf Spee and Admiral Scheer and the battleship Bismarck. However, the adoption of convoy escorts, especially in the Atlantic, greatly reduced the effectiveness of surface commerce raiders against convoys.

Following the end of World War II in 1945, the Kriegsmarine's remaining ships were divided up among the Allied powers and were used for various purposes including minesweeping. Some were loaded with superfluous chemical weapons and scuttled.[4]

History

[edit]Post–World War I origins

[edit]Under the terms of the 1919 Treaty of Versailles, Germany was only allowed a minimal navy of 15,000 personnel, six capital ships of no more than 10,000 tons, six cruisers, twelve destroyers, twelve torpedo boats, and no submarines or aircraft carriers. Military aircraft were also banned, so Germany could have no naval aviation. Under the treaty Germany could only build new ships to replace old ones. All the ships allowed and personnel were taken over from the Kaiserliche Marine, which was renamed the Reichsmarine.

From the outset, Germany worked to circumvent the military restrictions of the Treaty of Versailles. The Germans continued to develop U-boats through a submarine design office in the Netherlands (NV Ingenieurskantoor voor Scheepsbouw) and a torpedo research program in Sweden where the G7e torpedo was developed.[5]

Even before the Nazi seizure of power on 30 January 1933 the German government decided on 15 November 1932 to launch a prohibited naval re-armament program that included U-boats, airplanes, and an aircraft carrier.

The launching of the first pocket battleship, Deutschland in 1931 (as a replacement for the old pre-dreadnought battleship Preussen) was a step in the formation of a modern German fleet. The building of the Deutschland caused consternation among the French and the British as they had expected that the restrictions of the Treaty of Versailles would limit the replacement of the pre-dreadnought battleships to coastal defence ships, suitable only for defensive warfare. By using innovative construction techniques, the Germans had built a heavy ship suitable for offensive warfare on the high seas while still abiding by the letter of the treaty.

Nazi control

[edit]

When the Nazis came to power in 1933, Hitler soon began to more brazenly ignore many of the Treaty restrictions and accelerated German naval rearmament. The Anglo-German Naval Agreement of 18 June 1935 allowed Germany to build a navy equivalent to 35% of the British surface ship tonnage and 45% of British submarine tonnage; battleships were to be limited to 35,000 tons. That same year the Reichsmarine was renamed as the Kriegsmarine. In April 1939, as tensions escalated between the United Kingdom and Germany over Poland, Hitler unilaterally rescinded the restrictions of the Anglo-German Naval Agreement.

The building-up of the German fleet in the time period of 1935–1939 was slowed by problems with marshaling enough manpower and material for ship building. This was because of the simultaneous and rapid build-up of the German Army and Air Force which demanded substantial effort and resources. Some projects, like the D-class cruisers and the P-class cruisers, had to be cancelled.

Spanish Civil War

[edit]The first military action of the Kriegsmarine came during the Spanish Civil War (1936–1939). Following the outbreak of hostilities in July 1936 several large warships of the German fleet were sent to the region. The heavy cruisers Deutschland and Admiral Scheer, and the light cruiser Köln were the first to be sent in July 1936. These large ships were accompanied by the 2nd Torpedo-boat Flotilla. The German presence was used to covertly support Francisco Franco's Nationalists although the immediate involvement of the Deutschland was humanitarian relief operations and evacuating 9,300 refugees, including 4,550 German citizens. Following the brokering of the International Non-Intervention Patrol to enforce an international arms embargo, the Kriegsmarine was allotted the patrol area between Cabo de Gata (Almeria) and Cabo de Oropesa. Numerous vessels served as part of these duties including Admiral Graf Spee. On 29 May 1937 the Deutschland was attacked off Ibiza by two bombers from the Republican Air Force. Total casualties from the Republican attack were 31 dead and 110 wounded, 71 seriously, mostly burn victims. In retaliation the Admiral Scheer shelled Almeria on 31 May killing 19–20 civilians, wounding 50 and destroying 35 buildings.[6] Following further attacks by Republican submarines against the Leipzig off the port of Oran between 15 and 18 June 1937 Germany withdrew from the Non-Intervention Patrol.

U-boats also participated in covert action against Republican shipping as part of Operation Ursula. At least eight U-boats engaged a small number of targets in the area throughout the conflict. (By comparison the Italian Regia Marina operated 58 submarines in the area as part of the Sottomarini Legionari.)

Plan Z

[edit]The Kriegsmarine saw as her main tasks the controlling of the Baltic Sea and winning a war against France in connection with the German army, because France was seen as the most likely enemy in the event of war. But in 1938 Hitler wanted to have the possibility of winning a war against Great Britain at sea in the coming years. Therefore, he ordered plans for such a fleet from the Kriegsmarine. From the three proposed plans (X, Y and Z) he approved Plan Z in January 1939. This blueprint for the new German naval construction program envisaged building a navy of approximately 800 ships during the period 1939–1947. Hitler demanded that the program be completed by 1945. The main force of Plan Z were six H-class battleships. In the version of Plan Z drawn up in August 1939, the German fleet was planned to consist of the following ships by 1945:

- 4 aircraft carriers

- 10 battleships

- 15 armored ships (Panzerschiffe)

- 3 battlecruisers

- 5 heavy cruisers

- 44 light cruisers

- 158 destroyers and torpedo boats

- 249 submarines

- Numerous smaller craft

Personnel strength was planned to rise to over 200,000.

The planned naval program was not very far advanced by the time World War II began. In 1939 two M-class cruisers and two H-class battleships were laid down and parts for two further H-class battleships and three O-class battlecruisers were in production. The strength of the German fleet at the beginning of the war was not even 20% of Plan Z. On 1 September 1939, the navy still had a total personnel strength of only 78,000, and it was not at all ready for a major role in the war. Because of the long time it would take to get the Plan Z fleet ready for action and shortage in workers and material in wartime, Plan Z was essentially shelved in September 1939 and the resources allocated for its realisation were largely redirected to the construction of U-boats, which would be ready for war against the United Kingdom more quickly.[7]

World War II

[edit]

The Kriegsmarine took part in the Battle of Westerplatte and the Battle of the Danzig Bay during the invasion of Poland. In 1939, major events for the Kriegsmarine were the sinking of the British aircraft carrier HMS Courageous and the British battleship HMS Royal Oak and the loss of Admiral Graf Spee at the Battle of the River Plate. Submarine attacks on Britain's vital maritime supply routes (Battle of the Atlantic) started immediately at the outbreak of war, although they were hampered by the lack of well placed ports from which to operate. Throughout the war the Kriegsmarine was responsible for coastal artillery protecting major ports and important coastal areas. It also operated anti-aircraft batteries protecting major ports.[8]

In April 1940, the German Navy was heavily involved in the invasion of Norway, where it suffered significant losses, which included the heavy cruiser Blücher sunk by artillery and torpedoes from Norwegian shore batteries at the Oscarsborg Fortress in the Oslofjord. Ten destroyers were lost in the Battles of Narvik (half of German destroyer strength at the time), and two light cruisers, the Königsberg which was bombed and sunk by Royal Navy aircraft in Bergen, and the Karlsruhe which was sunk off the coast of Kristiansand by a British submarine. The Kriegsmarine did in return sink some British warships during this campaign, including the aircraft carrier HMS Glorious.

The losses in the Norwegian Campaign left only a handful of undamaged heavy ships available for the planned, but never executed, invasion of the United Kingdom (Operation Sea Lion) in the summer of 1940. There were serious doubts that the invasion sea routes could have been protected against British naval interference. The Fall of France and the conquest of Norway gave German submarines greatly improved access to British shipping routes in the Atlantic. At first, British convoys lacked escorts that were adequate either in numbers or equipment and, as a result, the submarines had much success for few losses (this period was dubbed the First Happy Time by the Germans).

Italy entered the war in June 1940, and the Battle of the Mediterranean began: from September 1941 to May 1944 some 62 German submarines were transferred there, sneaking past the British naval base at Gibraltar. The Mediterranean submarines sank 24 major Allied warships (including 12 destroyers, 4 cruisers, 2 aircraft carriers, and 1 battleship) and 94 merchant ships (449,206 tons of shipping). None of the Mediterranean submarines made it back to their home bases, as they were all either sunk in battle or scuttled by their crews at the end of the war.[9]

In 1941, one of the four modern German battleships, Bismarck sank HMS Hood while breaking out into the Atlantic for commerce raiding. The Bismarck was in turn hunted down by much superior British forces after being crippled by an air-launched torpedo. She was subsequently scuttled after being rendered a burning wreck by two British battleships.

In November 1941 during the Battle of the Mediterranean, German submarine U-331 sank the British battleship Barham, which had a magazine explosion and sank in minutes, with the loss of 862, or 2/3 of her crew.[10]

During 1941, the Kriegsmarine and the United States Navy became de facto belligerents, although war was not formally declared, leading to the sinking of the USS Reuben James. This course of events were the result of the American decision to support Britain with its Lend-Lease program and the subsequent decision to escort Lend-Lease convoys with US war ships through the western part of the Atlantic.

The Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor and the subsequent German declaration of war against the United States in December 1941 led to another phase of the Battle of the Atlantic. In Operation Drumbeat and subsequent operations until August 1942, a large number of Allied merchant ships were sunk by submarines off the US coast as the Americans had not prepared for submarine warfare, despite clear warnings (this was the so-called Second Happy Time for the German Navy). The situation became so serious that military leaders feared for the whole Allied strategy. The vast American ship building capabilities and naval forces were however now brought into the war and soon more than offset any losses inflicted by the German submariners. In 1942, the submarine warfare continued on all fronts, and when German forces in the Soviet Union reached the Black Sea, a few submarines were eventually transferred there.

In February 1942, the three large warships stationed on the Atlantic coast at Brest were evacuated back to German ports for deployment to Norway. The ships had been repeatedly damaged by air attacks by the RAF, the supply ships to support Atlantic sorties had been destroyed by the Royal Navy, and Hitler now felt that Norway was the "zone of destiny" for these ships. The two battleships Scharnhorst and Gneisenau and the heavy cruiser Prinz Eugen passed through the English Channel (Channel Dash) on their way to Norway despite British efforts to stop them.[11][12][13] Not since the Spanish Armada in 1588 had any warships in wartime done this. It was a tactical victory for the Kriegsmarine and a blow to British morale, but the withdrawal removed the possibility of attacking allied convoys in the Atlantic with heavy surface ships.

With the German attack on the Soviet Union in June 1941 Britain started to send Arctic convoys with military goods around Norway to support their new ally. In 1942 German forces began heavily attacking these convoys, mostly with bombers and U-boats. The big ships of the Kriegsmarine in Norway were seldom involved in these attacks, because of the inferiority of German radar technology,[14] and because Hitler and the leadership of the Kriegsmarine feared losses of these precious ships. The most effective of these attacks was the near destruction of Convoy PQ 17 in July 1942. Later in the war German attacks on these convoys were mostly reduced to U-boat activities and the mass of the allied freighters reached their destination in Soviet ports.

The Battle of the Barents Sea in December 1942 was an attempt by a German naval surface force to attack an Allied Arctic convoy. However, the advantage was not pressed home and they returned to base. There were serious implications: this failure infuriated Hitler, who nearly enforced a decision to scrap the surface fleet. Instead, resources were diverted to new U-boats, and the surface fleet became a lesser threat to the Allies.

After December 1943 when Scharnhorst had been sunk in an attack on an Arctic convoy in the Battle of North Cape by HMS Duke of York, most German surface ships in bases at the Atlantic were blockaded in, or close to, their ports as a fleet in being, for fear of losing them in action and to tie up British naval forces. The largest of these ships, the battleship Tirpitz, was stationed in Norway as a threat to Allied shipping and also as a defence against a potential Allied invasion. When she was sunk, after several attempts, by British bombers in November 1944 (Operation Catechism), several British capital ships could be moved to the Far East.

From late 1944 until the end of the war, the surviving surface fleet of the Kriegsmarine (heavy cruisers: Admiral Scheer, Lützow, Admiral Hipper, Prinz Eugen, light cruisers: Nürnberg, Köln, Emden) was heavily engaged in providing artillery support to the retreating German land forces along the Baltic coast and in ferrying civilian refugees to the western Baltic Sea parts of Germany (Mecklenburg, Schleswig-Holstein) in large rescue operations. Large parts of the population of eastern Germany fled the approaching Red Army out of fear for Soviet retaliation (mass rapes, killings, and looting by Soviet troops did occur[citation needed]). The Kriegsmarine evacuated two million civilians and troops in the evacuation of East Prussia and Danzig from January to May 1945. It was during this activity that the catastrophic sinking of several large passenger ships occurred: Wilhelm Gustloff and Goya were sunk by Soviet submarines, while Cap Arcona was sunk by British bombers, each sinking claiming thousands of civilian lives. The Kriegsmarine also provided important assistance in the evacuation of the fleeing German civilians of Pomerania and Stettin in March and April 1945.

A desperate measure of the Kriegsmarine to fight the superior strength of the Western Allies from 1944 was the formation of the Kleinkampfverbände (Small Battle Units). These were special naval units with frogmen, manned torpedoes, motorboats laden with explosives and so on. The more effective of these weapons and units were the development and deployment of midget submarines like the Molch and Seehund. In the last stage of the war, the Kriegsmarine also organised a number of divisions of infantry from its personnel.[8]

Between 1943 and 1945, a group of U-boats known as the Monsun Boats (Monsun Gruppe) operated in the Indian Ocean from Japanese bases in the occupied Dutch East Indies and Malaya. Allied convoys had not yet been organised in those waters, so initially many ships were sunk. However, this situation was soon remedied.[15] During the later war years, the Monsun Boats were also used as a means of exchanging vital war supplies with Japan.

During 1943 and 1944, due to Allied anti-submarine tactics and better equipment, the U-boat fleet started to suffer heavy losses. The turning point of the Battle of the Atlantic was during Black May in 1943, when the U-boat fleet started suffering heavy losses and the number of Allied ships sunk started to decrease. Radar, longer range air cover, sonar, improved tactics, and new weapons all contributed. German technical developments, such as the Schnorchel, attempted to counter these. Near the end of the war a small number of the new Elektroboot U-boats (types XXI and XXIII) became operational, the first submarines designed to operate submerged at all times. The Elektroboote had the potential to negate the Allied technological and tactical advantage, although they were deployed too late to see combat in the war.[16]

War crimes

[edit]

Following the capture of Liepāja in Latvia by the Germans on 29 June 1941, the town came under the command of the Kriegsmarine. On 1 July 1941, the town commandant Korvettenkapitän Stein ordered that ten hostages be shot for every act of sabotage, and further put civilians in the zone of targeting by declaring that Red Army soldiers were hiding among them in civilian attire.

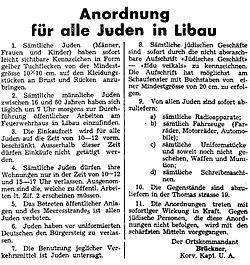

On 5 July 1941 Korvettenkapitän Brückner, who had taken over from Stein, issued a set of anti-Jewish regulations[18] in the local newspaper, Kurzemes Vārds.[17] Summarized, the regulations were as follows:[19]

- All Jews were to wear the yellow star on the front and back of their clothing;

- Shopping hours for Jews were restricted to 10:00 a.m. to 12:00 noon. Jews were only allowed out of their residences for these hours and from 3:00 p.m. to 5:00 p.m.;

- Jews were barred from public events and transportation and were not to walk on the beach;

- Jews were required to leave the pavement if they encountered a German in uniform;

- Jewish shops were required to display the sign "A Jewish-owned business" in the window;

- Jews were to surrender all radios, typewriters, uniforms, arms, and means of transportation

On 16 July 1941, Fregattenkapitän Dr. Hans Kawelmacher was appointed the German naval commandant in Liepāja.[20] On 22 July, Kawelmacher sent a telegram to the German Navy's Baltic Command in Kiel, which stated that he wanted 100 SS and fifty Schutzpolizei (protective police) men sent to Liepāja for "quick implementation Jewish problem".[21] Kawelmacher hoped to accelerate the killings, complaining: "Here about 8,000 Jews... with present SS-personnel, this would take one year, which is untenable for [the] pacification of Liepāja."[22] Kawelmacher telegram on 27 July 1941 read: "Jewish problem Libau largely solved by execution of about 1,100 male Jews by Riga SS commando on 24 and 25.7."[21]

In September 1939, U-boat commander Fritz-Julius Lemp of U-30 sank SS Athenia (1922) after mistaking it for a legitimate military target, resulting in the deaths of 117 civilians. Germany did not admit responsibility for the incident until after the war. Lemp was killed in action in 1941. U-247 was alleged to have shot at sunken ship survivors, but as the vessel was lost at sea with its crew, there was no investigation.

In 1945, U-boat Commander Heinz-Wilhelm Eck of U-852 was tried along with four of his crewmen for shooting at survivors. All were found guilty, with three of them, including Eck, being executed. In 1946, Hellmuth von Ruckteschell was sentenced to 10 years in prison, reduced to 7 years on appeal, for the illegal sinking of ships and criminal negligence for failing to protect the downed crew of the SS Anglo Saxon. Ruckteschell died in prison in 1948.

Post-war division

[edit]After the war, the German surface ships that remained afloat (only the cruisers Prinz Eugen and Nürnberg, and a dozen destroyers were operational) were divided among the victors by the Tripartite Naval Commission. The US used the heavy cruiser Prinz Eugen in nuclear testing at Bikini Atoll in 1946 as a target ship for the Operation Crossroads. Some (like the unfinished aircraft carrier Graf Zeppelin) were used for target practice with conventional weapons, while others (mostly destroyers and torpedo boats) were put into the service of Allied navies that lacked surface ships after the war. The training barque SSS Horst Wessel was recommissioned USCGC Eagle and remains in active service, assigned to the United States Coast Guard Academy. The British, French, and Soviet navies received the destroyers, and some torpedo boats went to the Danish and Norwegian navies. For the purpose of mine clearing, the Royal Navy employed German crews and minesweepers from June 1945 to January 1948,[23] organised in the German Mine Sweeping Administration (GMSA), which consisted of 27,000 members of the former Kriegsmarine and 300 vessels.[24]

The destroyers and the Soviet share light cruiser Nürnberg were all retired by the end of the 1950s, but five escort destroyers were returned from the French to the new West German Navy in the 1950s and three 1945 scuttled type XXI and XXIII U-boats were raised by West Germany and integrated into their new navy. In 1956, with West Germany's accession to NATO, a new navy was established and was referred to as the Bundesmarine (Federal Navy). Some Kriegsmarine commanders like Erich Topp and Otto Kretschmer went on to serve in the Bundesmarine. In East Germany the Volksmarine (People's Navy) was established in 1956. With the reunification of Germany in 1990, it was decided to use the name Deutsche Marine (German Navy).

Major wartime operations

[edit]- Wikinger ("Viking") (1940) – foray by destroyers into the North Sea

- Weserübung ("Operation Weser") (1940) – invasion of Denmark and Norway

- Juno (1940) – operation to disrupt Allied supplies to Norway

- Nordseetour (1940) – first Atlantic operation of Admiral Hipper

- Berlin (1941) – Atlantic cruise of Scharnhorst and Gneisenau

- Rheinübung ("Rhine exercise") (1941) – breakout by Bismarck and Prinz Eugen

- Doppelschlag ("Double blow") (1942) – anti-shipping operation off Novaya Zemlya by Admiral Scheer and Admiral Hipper

- Sportpalast (1942) – aborted operation (including Tirpitz) to attack Arctic convoys

- Rösselsprung ("Knights Move") (1942) – operation (including Tirpitz) to attack Arctic convoy PQ 17

- Wunderland (1942) – anti-shipping operation in Kara Sea by Admiral Scheer

- Paukenschlag ("Drumbeat" ("Beat of the Kettle Drum"); "Second Happy Time") (1942) – U-boat campaign off the United States east coast

- Neuland ("New Land") (1942) – U-boat campaign in the Caribbean Sea; launched in conjunction with Operation Drumbeat

- Regenbogen ("Rainbow") (1942) – failed attack on Arctic convoy JW 51B, by Admiral Hipper and Lützow

- Cerberus (1942) – movement of capital ships from Brest to home ports in Germany (Channel Dash)

- Ostfront ("East front") (1943) – final operation of Scharnhorst, to intercept convoy JW 55B

- Domino (1943) – second aborted Arctic sortie by Scharnhorst, Prinz Eugen, and destroyers

- Zitronella ("Lemon extract") (1943) – raid upon Allied-occupied Spitzbergen (Svalbard)

- Hannibal (1945) – evacuation proceedings from Courland, Danzig-West Prussia, and East Prussia

- Deadlight (1945) – the British Royal Navy's postwar scuttling of Kriegsmarine U-boats

Ships

[edit]

By the start of World War II, much of the Kriegsmarine were modern ships: fast, well-armed, and well-armoured. This had been achieved by concealment but also by deliberately flouting World War I peace terms and those of various naval treaties. However, the war started with the German Navy still at a distinct disadvantage in terms of sheer size with what were expected to be its primary adversaries – the navies of France and Great Britain. Although a major re-armament of the navy (Plan Z) was planned, and initially begun, the start of the war in 1939 meant that the vast amounts of material required for the project were diverted to other areas. The sheer disparity in size when compared to the other European powers navies prompted Raeder to write of his own navy once the war began "The surface forces can do no more than show that they know how to die gallantly." A number of captured ships from occupied countries were added to the German fleet as the war progressed.[25] Though six major units of the Kriegsmarine were sunk during the war (both Bismarck-class battleships and both Scharnhorst-class battleships, as well as two heavy cruisers), there were still many ships afloat (including four heavy cruisers and four light cruisers) as late as March 1945.

Some ship types do not fit clearly into the commonly used ship classifications. Where there is argument, this has been noted.

Surface ships

[edit]The main combat ships of the Kriegsmarine (excluding U-boats):

Aircraft carriers

[edit]Construction of Graf Zeppelin was started in 1936 and construction of an unnamed sister ship was started two years later in 1938, but neither ship was completed. In 1942 conversion of three German passenger ships (Europa, Potsdam, Gneisenau) and two unfinished cruisers, the captured French light cruiser De Grasse and the German heavy cruiser Seydlitz, to auxiliary carriers was begun. In November 1942 the conversion of the passenger ships was stopped because these ships were now seen as too slow for operations with the fleet. But conversion of one of these ships, the Potsdam, to a training carrier was begun instead. In February 1943 all the work on carriers was halted because of the German failure during the Battle of the Barents Sea, which convinced Hitler that large warships were useless.

All engineering of the aircraft carriers like catapults, arresting gears and so on were tested and developed at the Erprobungsstelle See Travemünde (Experimental Agency Sea in Travemünde) including the airplanes for the aircraft carriers, the Fieseler Fi 167 ship-borne biplane torpedo and reconnaissance bomber and the naval versions of two key early war Luftwaffe aircraft: the Messerschmitt Bf 109T fighter and the Junkers Ju 87C Stuka dive bomber.

Battleships

[edit]

The Kriegsmarine completed four battleships during its existence. The first pair were the 11-inch gun Scharnhorst class, consisting of the Scharnhorst and Gneisenau, which participated in the invasion of Norway in 1940, and then in commerce raiding until the Gneisenau was heavily damaged by a British air raid in 1942 and the Scharnhorst was sunk in the Battle of the North Cape in late 1943. The second pair were the 15-inch gun Bismarck class, consisting of the Bismarck and Tirpitz. The Bismarck was sunk on her first sortie into the Atlantic in 1941 (Operation Rheinübung) although she did sink the battlecruiser Hood and severely damaged the battleship Prince of Wales, while the Tirpitz was based in Norwegian ports during most of the war as a fleet in being, tying up Allied naval forces, and subject to a number of attacks by British aircraft and submarines. More battleships were planned (the H-class), but construction was abandoned in September 1939.

Pre-dreadnought battleships

[edit]

The World War I-era pre-dreadnought battleships Schlesien and Schleswig-Holstein were used mainly as training ships, although they also participated in several military operations, with the latter bearing the distinction of firing the opening shots of World War II. Zähringen and Hessen were converted into radio-guided target ships in 1928 and 1930 respectively. Hannover was decommissioned in 1931 and struck from the naval register in 1936. Plans to convert her into a radio-controlled target ship for aircraft was cancelled because of the outbreak of war in 1939.

Battlecruisers

[edit]Three O-class battlecruisers were ordered in 1939, but with the start of the war the same year there were not enough resources to build the ships.

Panzerschiffe and Heavy cruisers

[edit]The Deutschland-class cruisers were the Deutschland (renamed Lützow), Admiral Scheer, and Admiral Graf Spee. Modern commentators favour classifying these as "heavy cruisers" and the Kriegsmarine itself reclassified these ships as such (Schwere Kreuzer) in 1940.[26] In German language usage these three ships were designed and built as "armoured ships" (Panzerschiffe) – "pocket battleship" is an English label.

The Graf Spee was scuttled by her own crew in the Battle of the River Plate, in the Rio de la Plata estuary in December 1939. Admiral Scheer was bombed on 9 April 1945 in port at Kiel and badly damaged, essentially beyond repair, and rolled over at her moorings. After the war that part of the harbor was filled in with rubble and the hulk buried. Lützow (ex-Deutschland) was bombed 16 April 1945 in the Baltic off Swinemünde just west of Stettin, and settled on the shallow bottom. With the Red Army advancing across the Oder, the ship was destroyed in place to prevent the Soviets capturing anything useful. The wreck was dismantled and scrapped in 1948–1949.[27]

The Admiral Hipper-class cruisers in active service were Admiral Hipper, Blücher, and Prinz Eugen. Cruisers Seydlitz, and Lützow were never completed.

Light cruisers

[edit]

The term "light cruiser" is a shortening of the phrase "light armoured cruiser". Light cruisers were defined under the Washington Naval Treaty by gun calibre. Light cruiser describes a small ship that was armoured in the same way as an armoured cruiser. In other words, like standard cruisers, light cruisers possessed a protective belt and a protective deck. Prior to this, smaller cruisers tended to be of the protected cruiser model and possessed only an armoured deck. The Kriegsmarine light cruisers were as follows:

Never completed: three M-class cruisers

Never completed: KH-1 and KH-2 (Kreuzer (cruiser) Holland 1 and 2). Captured in the Netherlands 1940. Both being on the stocks and building continued for the Kriegsmarine.

In addition, the former Kaiserliche Marine light cruiser Niobe was captured by the Germans on 11 September 1943 after the capitulation of Italy. She was pressed into Kriegsmarine service for a brief time before being destroyed by British MTBs.

Auxiliary cruisers

[edit]

During the war, some merchant ships were converted into "auxiliary cruisers" and nine were used as commerce raiders sailing under false flags to avoid detection, and operated in all oceans with considerable effect. The German designation for the ships was 'Handelstörkreuzer' thus the HSK serial assigned. Each had as well an administrative label more commonly used, e.g. Schiff 16 = Atlantis, Schiff 41 = Kormoran, etc. The auxiliary cruisers were:

- Orion (HSK-1, Schiff 36)

- Atlantis (HSK-2, Schiff 16)

- Widder (HSK-3, Schiff 21)

- Thor (HSK-4, Schiff 10)

- Pinguin (HSK-5, Schiff 33)

- Stier (HSK-6, Schiff 23)

- Komet (HSK-7, Schiff 45)

- Kormoran (HSK-8, Schiff 41)

- Michel (HSK-9, Schiff 28)

- Coronel (HSK number not assigned, Schiff 14, never active in raider operations.)

- Hansa (HSK not assigned, Schiff 5, never active in raider operations, used as a training ship)[28]

Destroyers

[edit]

Although the German World War II destroyer (Zerstörer) fleet was modern and the ships were larger than conventional destroyers of other navies, they had problems. Early classes were unstable, wet in heavy weather, suffered from engine problems, and had short range. Some problems were solved with the evolution of later designs, but further developments were curtailed by the war and, ultimately, by Germany's defeat. In the first year of World War II, they were used mainly to sow offensive minefields in shipping lanes close to the British coast.[citation needed]

Torpedo boats

[edit]

These vessels evolved through the 1930s from small vessels, relying almost entirely on torpedoes, to what were effectively small destroyers with mines, torpedoes, and guns. Two classes of fleet torpedo boats were planned, but not built, in the 1940s.

E-boats (Schnellboote)

[edit]The E-boats were fast attack craft with torpedo tubes. Over 200 boats of this type were built for the Kriegsmarine.

Troop ships

[edit]Cap Arcona, Goya, General von Steuben, Monte Rosa, Wilhelm Gustloff.

Miscellaneous

[edit]Thousands of smaller warships and auxiliaries served in the Kriegsmarine, including minelayers, minesweepers, mine transports, netlayers, floating AA and torpedo batteries, command ships, decoy ships (small merchantmen with hidden weaponry), gunboats, monitors, escorts, patrol boats, sub-chasers, landing craft, landing support ships, training ships, test ships, torpedo recovery boats, dispatch boats, aviso, fishery protection ships, survey ships, harbor defense boats, target ships and their radio control vessels, motor explosive boats, weather ships, tankers, colliers, tenders, supply ships, tugs, barges, icebreakers, hospital and accommodation ships, floating cranes and docks, and many others. The Kriegsmarine employed hundreds of auxiliary Vorpostenboote during the war, mostly civilian ships that were drafted and fitted with military equipment, for use in coastal operations.

Submarines

[edit]

The Submarine Arm of the Kriegsmarine was titled the U-bootwaffe ("submarine force"). At the outbreak of war, it had a fleet of 57 submarines.[29] This was increased steadily until mid-1943, when losses from Allied counter-measures matched the new vessels launched.[30]

The principal types were the Type IX, a long range type used in the western and southern Atlantic, Indian and Pacific Oceans; the Type VII, the most numerous type, used principally in the north Atlantic; and the small Type II, for coastal waters. Type X was a small class of minelayers and Type XIV was a specialised type used to support distant U-boat operations – the "Milchkuh" (Milkcow).

Types XXI and XXIII, the "Elektroboot", could have negated much of the Allied anti-submarine tactics and technology, but only a few of this new type of U-boat became ready for combat at the end of the war. Post-war, they became the prototype for modern conventional submarines, such as the Soviet Zulu class.

During World War II, about 60% of all U-boats commissioned were lost in action; 28,000 of the 40,000 U-boat crewmen were killed during the war and 8,000 were captured. The remaining U-boats were either surrendered to the Allies or scuttled by their own crews at the end of the war.[31]

| Name | Shipping sunk |

|---|---|

| Otto Kretschmer | 274,333 tons (47 ships sunk) |

| Wolfgang Lüth | 225,712 tons (43 ships) |

| Erich Topp | 193,684 tons (34 ships) |

| Karl-Friedrich Merten | 186,064 tons (29 ships) |

| Victor Schütze | 171,164 tons (34 ships) |

| Herbert Schultze | 171,122 tons (26 ships) |

| Georg Lassen | 167,601 tons (28 ships) |

| Heinrich Lehmann-Willenbrock | 166,596 tons (22 ships) |

| Heinrich Liebe | 162,333 tons (30 ships) |

| Günther Prien | 160,939 tons (28 ships), plus the British battleship HMS Royal Oak inside Scapa Flow |

Captured ships

[edit]The military campaigns in Europe yielded a large number of captured vessels, many of which were under construction. Nations represented included Austria (riverine craft), Czechoslovakia (riverine craft), Poland, Norway, Denmark, the Netherlands, Belgium, France, Yugoslavia, Greece, the Soviet Union, the United Kingdom, the United States (several landing craft), and Italy (after the armistice). Few of the incomplete ships of destroyer size or above were completed, but many smaller warships and auxiliaries were completed and commissioned into Kriegsmarine during the war. Additionally many captured or confiscated foreign civilian ships (merchantmen, fishing boats, tugboats etc.) were converted into auxiliary warships or support ships.

Major enemy warships sunk or destroyed

[edit]On 3 September 1939, during the early days of the invasion of Poland, the Polish destroyer ORP Wicher of the Polish Navy, was sunk by German Ju 87 dive bombers belonging to Trägergeschwader 186—a Luftwaffe unit established for naval aviation and intended for deployment aboard the aircraft carrier Graf Zeppelin. However, as the Graf Zeppelin was not operational and never saw combat, these aircraft conducted their attacks from land-based airfields under Kriegsmarine direction.[32]

| Ship | Type | Date | Action |

|---|---|---|---|

| HMS Courageous (Royal Navy) | Fleet aircraft carrier | 17 September 1939 | Torpedoed by submarine U-29 |

| HMS Royal Oak (Royal Navy) | Battleship | 14 October 1939 | Torpedoed at anchor by submarine U-47 |

| HNoMS Eidsvold (Royal Norwegian Navy) | Coastal defence ship | 9 April 1940 | Torpedoed in Narvik harbor by destroyer Z21 Wilhelm Heidkamp |

| HNoMS Norge (Royal Norwegian Navy) | Coastal defence ship | 9 April 1940 | Torpedoed in Narvik harbor by destroyer Z11 Bernd von Arnim |

| Jaguar (French Navy) | Large destroyer | 23 May 1940 | Torpedoed by torpedo boats (E-boats) S21 and S23 |

| HMS Glorious (Royal Navy) | Fleet aircraft carrier | 8 June 1940 | Sunk by battleships Gneisenau and Scharnhorst |

| HMS Hood (Royal Navy) | Battlecruiser | 24 May 1941 | Sunk by the battleship Bismarck |

| HMS Ark Royal (Royal Navy) | Fleet aircraft carrier | 14 November 1941 | Torpedoed by submarine U-81 on 13 November, sank while under tow to Gibraltar |

| HMAS Sydney (Royal Australian Navy) | Light cruiser | 19 November 1941 | Sunk by the auxiliary cruiser Kormoran. The Kormoran was also sunk in the battle. |

| HMS Dunedin (Royal Navy) | Light cruiser | 24 November 1941 | Torpedoed by submarine U-124 |

| HMS Barham (Royal Navy) | Battleship | 25 November 1941 | Torpedoed by submarine U-331. While the attack on the ship was recorded, the Kriegsmarine were unaware that it had been sunk until 27 January 1942 when the Admiralty admitted Barham's loss. |

| HMS Galatea (Royal Navy) | Light cruiser | 14 December 1941 | Torpedoed by submarine U-557 |

| HMS Audacity (Royal Navy) | Escort carrier | 21 December 1941 | Torpedoed by submarine U-751 |

| HMS Naiad (Royal Navy) | Light cruiser | 11 March 1942 | Torpedoed by submarine U-565 |

| HMS Edinburgh (Royal Navy) | Light cruiser | 2 May 1942 | Torpedoed by U-456 and destroyers Z7 Hermann Schoemann, Z24 and Z25, abandoned and scuttled |

| HMS Hermione (Royal Navy) | Light cruiser | 16 June 1942 | Torpedoed by submarine U-205 |

| HMS Eagle (Royal Navy) | Aircraft carrier | 11 August 1942 | Torpedoed by submarine U-73 |

| HMS Avenger (Royal Navy) | Escort carrier | 15 November 1942 | Torpedoed by submarine U-155 |

| HMS Welshman (Royal Navy) | Minelaying cruiser | 1 February 1943 | Torpedoed by U-617 |

| HMS Abdiel (Royal Navy) | Minelaying cruiser | 10 September 1943 | Sunk by mines in Taranto harbor while operating as a transport. The mines were laid by torpedo boats (E-boats) S54 and S61. |

| HMS Charybdis (Royal Navy) | Light cruiser | 23 October 1943 | Torpedoed by torpedo boats T23 and T27 |

| HMS Penelope (Royal Navy) | Light cruiser | 18 February 1944 | Torpedoed by submarine U-410 |

| USS Block Island (US Navy) | Escort carrier | 29 May 1944 | Torpedoed by submarine U-549 |

| HMS Scylla (Royal Navy) | Light cruiser | 23 June 1944 | Mine hit, declared a constructive total loss |

| ORP Dragon (Polish Navy) | Light cruiser | 7 July 1944 | Torpedoed by a Neger manned torpedo, abandoned and scuttled |

| HMS Nabob (Royal Navy) | Escort carrier | 22 August 1944 | Torpedoed by U-354, judged not worth repairing, beached and abandoned |

| HMS Thane (Royal Navy) | Escort carrier | 15 January 1945 | Torpedoed by U-1172, declared a constructive total loss |

Organisation

[edit]Command structure

[edit]

Adolf Hitler was the Supreme Commander of all German forces, including the Kriegsmarine. His authority was exercised through the Oberkommando der Marine (OKM) with a Commander-in-Chief (Oberbefehlshaber der Kriegsmarine), a Chief of Naval General Staff (Chef des Stabes der Seekriegsleitung), and a Chief of Naval Operations (Chef der Operationsabteilung).[35] The first Commander-in-Chief of the OKM was Erich Raeder who was the Commander-in-Chief of the Reichsmarine when it was renamed and reorganised in 1935. Raeder held the post until falling out with Hitler after the German failure in the Battle of the Barents Sea. He was replaced by Karl Dönitz on 30 January 1943 who held the command until he was appointed President of Germany upon Hitler's suicide in April 1945. Hans-Georg von Friedeburg was then Commander-in-Chief of the OKM for the short period of time until Germany surrendered in May 1945.

Subordinate to these were regional, squadron, and temporary flotilla commands. Regional commands covered significant naval regions and were themselves sub-divided, as necessary. They were commanded by a Generaladmiral or an Admiral. There was a Marineoberkommando for the Baltic Fleet, Nord, Nordsee, Norwegen, Ost/Ostsee (formerly Baltic), Süd, and West. The Kriegsmarine used a form of encoding called Gradnetzmeldeverfahren to denote regions on a map.

Each squadron (organised by type of ship) also had a command structure with its own Flag Officer. The commands were Battleships, Cruisers, Destroyers, Submarines (Führer der Unterseeboote), Torpedo Boats, Minesweepers, Reconnaissance Forces, Naval Security Forces, Big Guns and Hand Guns, and Midget Weapons.

Major naval operations were commanded by a Flottenchef. The Flottenchef controlled a flotilla and organized its actions during the operation. The commands were, by their nature, temporary.

The Kriegsmarine's ship design bureau, known as the Marineamt, was administered by officers with experience in sea duty but not in ship design, while the naval architects who did the actual design work had only a theoretical understanding of design requirements. As a result, the German surface fleet was plagued by design flaws throughout the war.[36]

Communication was undertaken using an eight-rotor system of Enigma encoding.

Air units

[edit]The Luftwaffe had a near-complete monopoly on all German military aviation, including naval aviation, a source of great interservice rivalry with the Kriegsmarine. Catapult-launched spotter planes like Arado Ar 196 twin-float seaplanes were manned by the so-called Bordfliegergruppe 196 (shipboard flying group 196).[37] Trägergeschwader 186 (Carrier Air Wing 186) operated two Gruppen (Trägergruppe I/186 and Trägergruppe II/186) equipped with navalized Messerschmitt Bf 109T and Junkers Ju 87C Stuka; these units were intended to serve aboard the aircraft carrier Graf Zeppelin which was never completed, yet provided the Kriegsmarine with some air-power from bases on land.[38] Five coastal groups (Küstenfliegergruppen) with reconnaissance aircraft, torpedo bombers, Minensuch aerial minesweepers, and air-sea rescue seaplanes supported the Kriegsmarine, although with lesser resources as the war progressed.[39]

Coastal artillery, flak and radar units

[edit]The coastal batteries of the Kriegsmarine were stationed on the German coasts. With the conquering and occupation of other countries coastal artillery was stationed along the coasts of these countries, especially in France and Norway as part of the Atlantic Wall.[40] Naval bases were protected by flak-batteries of the Kriegsmarine against enemy air raids. The Kriegsmarine also manned the Seetakt sea radars on the coasts.[40]

Marines

[edit]At the beginning of World War II, on 1 September 1939, the Marinestoßtruppkompanie (Naval Shock Troop Company) landed in Danzig from the old battleship Schleswig-Holstein for conquering a Polish bastion at Westerplatte. A reinforced platoon of the Marine Stoßtrupp Kompanie landed with soldiers of the German Army from destroyers on 9 April 1940 in Narvik. In June 1940 the Marine Stoßtrupp Abteilung (Marine Attack Troop Battalion) was flown in from France to the Channel Islands to occupy this British territory.

In September 1944 amphibious units unsuccessfully tried to capture the strategic island Suursaari in the Gulf of Finland from Germany's former ally Finland (Operation Tanne Ost).

With the invasion of Normandy in June 1944 and the Soviet advance from the summer of 1944 the Kriegsmarine started to form regiments and divisions for the battles on land with superfluous personnel. With the loss of naval bases because of the Allied advance more and more navy personnel were available for the ground troops of the Kriegsmarine. About 40 regiments were raised and from January 1945 on six divisions. Half of the regiments were absorbed by the divisions.[41]

Personnel

[edit]- Personnel strength of the Kriegsmarine 1939-1945

| Year | Strength |

|---|---|

| 1939 | 105,000 |

| 1940 | 280,000 |

| 1941 | 435,000 |

| 1942 | 569,000 |

| 1943 | 780,000 |

| 1944 | 810,000 |

| 1945 | 700,000 |

| Source: | [42] |

Ranks and uniforms

[edit]

Many different types of uniforms were worn by the Kriegsmarine; here is a list of the main ones:

- Dienstanzug (Service suit)

- Kleiner Dienstanzug (Lesser service uniform)

- Ausgehanzug (Suit for walking out)

- Sportanzug (Sportswear)

- Tropen-und Sommeranzug (Tropical and summer suit) – uniforms for hot climates

- Große Uniform (Parade uniform)

- Kleiner Gesellschaftsanzug (Small party suit)

- Großer Gesellschaftsanzug (Full dress uniform)

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ "German Military Oaths".

- ^ "Wehrmacht > WW2 Weapons". 28 June 2019.

- ^ "Peace Treaty of Versailles, Articles 159-213, Military, Naval and Air Clauses". net.lib.byu.edu.

- ^ Chemical Weapons Dumped in the Ocean After World War II Could Threaten Waters Worldwide smithsonianmag.com November 11, 2016

- ^ Wolves Without Teeth: The German Torpedo Crisis in World War Two p. 24

- ^ Thomas, Hugh. The Spanish Civil War. Penguin Books. London. 2006. p.665

- ^ Siegfried Breyer: Der Z-PLAN. Podzun-Pallas-Verlag. Wölfersheim-Berstadt 1996. ISBN 3-7909-0535-6

- ^ a b "Organization of the Kriegsmarine in the West 1940-45". Feldgrau. 4 August 2020.

- ^ Uboat.net, U-boats in the Mediterranean – Overview

- ^ "Battleship HMS Barham - Militär Wissen". Retrieved 21 July 2021.

- ^ Garzke, William H.; Dulin, Robert O. (1985). Battleships: Axis and Neutral Battleships in World War II. Annapolis: Naval Institute Press. pp. 145–146. ISBN 978-0-87021-101-0.

- ^ Koop, Gerhard; Schmolke, Klaus-Peter (1999). Battleships of the Scharnhorst Class. Annapolis: Naval Institute Press. p. 111. ISBN 978-1-55750-045-8.

- ^ Hellwinkel, Lars (2014). Hitler's Gateway to the Atlantic: German Naval Bases in France 1940-1945 (Kindle, English Translation ed.). Barnsley: Seaforth Publishing. p. Kindle location 731 of 4855. ISBN 978-184832-199-1.

- ^ Sieche, Erwin (4 May 2007). "German Naval Radar to 1945". Naval Weapons of the World. Retrieved 23 December 2012.

- ^ Uboat.net, U-boat Operations – The Monsun U-boats

- ^ Submarines: an illustrated history of their impact Paul E. Fontenoy p.39

- ^ a b (in Latvian) Kurzemes Vārds, 5 July 1941, page 1, at website of National Library of Latvia. Archived 30 October 2018 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Ezergailis, The Holocaust in Latvia, at page 209

- ^ Ezergailis, The Holocaust in Latvia, at page 233, n.26 and page 287

- ^ Dribins, Leo, Gūtmanis, Armands, and Vestermanis, Marģers, Latvia's Jewish Community: History, Tragedy, Revival (2001) at page 224

- ^ a b Anders and Dubrovskis, Who Died in the Holocaust, at pages 126 and 127

- ^ "Liepāja" (PDF). Liepāja Jews in WWII.

- ^ German Mine Sweeping Administration (GMSA) Archived 20 April 2008 at the Wayback Machine (in German), accessed: 9 June 2008

- ^ Google book review: German Seaman 1939–45 Page: 41, author: Gordon Williamson, John White, publisher: Osprey Publishing, accessed: 9 July 2008

- ^ "Captured Ships". German Naval History.

- ^ "Deutschland History". german-navy.de.

- ^ E. Gröner, Die Schiffe der deutschen Kriegsmarine. 2nd Edition, Lehmanns, München, 1976. C. Bekker, Verdammte See, Ein Kriegstagebuch der deutschen Marine. Köln, Neumann / Göbel, no date.1976,

- ^ E. Gröner, Die Schiffe der deutschen Kriegsmarine. 2nd Edition. 1976, München, Lehmanns Verlag.

- ^ Ireland, Bernard (2003). Battle of the Atlantic. Barnsley, UK: Pen & Sword Books. p. 32. ISBN 1-84415-001-1.

- ^ Ireland, Bernard (2003). Battle of the Atlantic. Barnsley, UK: Pen & Sword Books. p. 225. ISBN 1-84415-001-1.

- ^ "U-boats after World War Two - Fates - German U-boats of WWII - Kriegsmarine - uboat.net". uboat.net. Retrieved 8 May 2018.

- ^ "ORP Wicher of the Polish Navy - Polish Destroyer of the Wicher class - Allied Warships of WWII - uboat.net". uboat.net. Retrieved 25 May 2025.

- ^ "Battleships sunk by the Kriegsmarine". german-navy.de.

- ^ "Carriers sunk by the Kriegsmarine". german-navy.de.

- ^ Pipes, Jason (1996–2006). "Organization of the Kriegsmarine". Feldgrau.com. Retrieved 31 August 2007.

- ^ Lienau, Peter (22 October 1999). "The Working Environment for German Warship design in WWI and WWII". Naval Weapons of the World. Retrieved 23 December 2012.

- ^ Admin (4 August 2020). "Bordfliegergruppe 196". Feldgrau.

- ^ "Trägergruppe 186". Feldgrau. 4 August 2020.

- ^ "Seefliegerverbände 1939-45". www.wlb-stuttgart.de.

- ^ a b J. P. Mallmann-Showell: Das Buch der deutschen Kriegsmarine 1935–1945. Publisher Motorbuch. Stuttgart 1995 ISBN 3-87943-880-3 p. 75–91

- ^ Jörg Benz: Deutsche Marineinfanterie 1938–1945. Publisher Husum Druck. Husum 1996. ISBN 3880427992

- ^ Delgado, Eduardo (2016). Deutsche Kriegsmarine: Uniforms, Insignias and Equipment of the German Navy 1933-1945. Andrea Press, p. 34.

Bibliography

[edit]- Bird, Keith (1977). Weimar, the German Naval Officer Corps, and the Rise of National Socialism. Amsterdam: Grüner. ISBN 9060320948.

- Bird, Keith (1985). German Naval History: A Guide to the Literature. New York: Garland. ISBN 0824090241.

- Bräckow, Werner (1974). Die Geschichte des deutschen Marine- Ingenieuroffizierskorps. Hamburg: Stalling. ISBN 3797918542.

- Breyer, Siegfried, and Gerhard Koop. (1985). Die deutsche Kriegsmarine. Friedberg: Podzun-Pallas.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Dülffer, Jost (1973). Weimar, Hitler, und die Marine:Reichspolitik und Flottenbau, 1920-1939. Düsseldorf: Droste. ISBN 3770003209.

- Dülffer, Jost; et al. (Deutsche Marinegeschichte der Neuzeit) (1977). Die Reichs- und Kriegsmarine, 1918-1939. Munich: Bernard und Graefe. pp. 337–488. OCLC 729157062.

- Güth, Rolf (1964). "Bild einer Crew". Marine Rundschau. Vol. 61, no. 3. pp. 131–41.

- Güth, Rolf; et al. (Deutsche Marinegeschichte der Neuzeit) (1977). Die Organisation der deutschen Marine in Krieg und Frieden, 1913-1933. Munich: Bernard und Graefe. pp. 263–336.

- Güth, Rolf (1978). Die Organisation der Kriegsmarine bis 1939." In Wehrmacht und Nationalsozialismus, 1933-1939, 401–500. Munich: Bernard und Graefe.

- Krüger, Peter (1966). "Die Verhandlungen über die deutsche Kriegs-und Handelsflotte auf der Konferenz von Potsdam 1945". Marine Rundschau. Vol. 63, no. 1. pp. 10–19, 81–94.

- Lohmann, Walter; Hildebrandt, Hans H. (1956). Die deutsche Kriegsmarine, 1939-1945. Bad Nauheim: Podzun.

- Löwke, Udo F. (1976). Die SPD und die Wehrfrage, 1949-1955. Bonn and Bad Godesberg: Neue Gesellschaft.

- Peifer, Douglas (2002). The Three German Navies: Dissolution, Transition, and New Beginning. Gainesville: University Press of Florida.

- Rahn, Werner; Schreiber, Gerhard (1988). Kriegstagebuch der Seekriegsleitung, 1939-1945. Herford: E.S. Mittler.

- Rohwer, Jürgen (1983). Axis Submarine Successes 1939-1945. Annapolis: Naval Institute Press.

- Rohwer, Jürgen and Gert Hümmelchen (2005). Chronology of the War at Sea, 1939-1945. Annapolis: Naval Institute Press. ISBN 1-59114-119-2.

- Roskill, Stephen W (2004). The War At Sea, 1939-1945. Uckfield: Naval and Military Press. ISBN 9781843428039.

- Rössler, Eberhard (1981). The U-Boat: The Evolution and Technical History of German Submarines. Annapolis: Naval Institute Press.

- Salewski, Michael (1975). 1942-1945. Die deutsche Seekriegsleitung, 1935-1945. Vol. 2. Munich: Bernard und Graefe.

- Showell, Jak P. Mallmann (1979). The German Navy in World War Two : a reference guide to the Kriegsmarine, 1935-1945. Annapolis: Naval Institute Press. ISBN 0870219332.

- Tarrant, V. E. (1994). The Last Year of the Kriegsmarine: May 1944-May 1945. Annapolis: Naval Institute Press.

- Thomas, Charles S. (1990). The German Navy in the Nazi Era. Annapolis: Naval Institute Press.

- Thompson, Harold Keith, and Henry Strutz. (1976). Dönitz at Nuremberg: A Reappraisal: War Crimes and the Military Professional. New York: Amber.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

External links

[edit]- The Nazi German Navy 1935-1945 (Kriegsmarine)

- "German U-Boats and Battle of the Atlantic". uboataces.com. Retrieved 20 January 2007.

- "Kriegsmarine History". german-navy.de. Retrieved 20 January 2007.

- Helgason, Guðmundur. "The U-boat War 1939–1945". German U-boats of WWII - uboat.net. Retrieved 20 January 2007.

- "Bismarck & Tirpitz". bismarck-class.dk. Retrieved 20 January 2007.

- "Deutschland in Spanish Civil War". bismarck-class.dk. Archived from the original on 6 February 2007. Retrieved 20 January 2007.

- The photo album of Kriegsmarine minelayer 'Roland' crew member. Archived 8 May 2015 at the Wayback Machine Photos of minelayers on combat missions and various Kriegsmarine vessels.

Kriegsmarine

View on GrokipediaOrigins and Rearmament

Versailles Treaty Constraints and Reichsmarine

The Treaty of Versailles, signed on June 28, 1919, imposed severe restrictions on the German navy to prevent it from posing a future threat to Allied powers. Article 181 and subsequent naval clauses limited the fleet to six pre-dreadnought battleships of the Deutschland or Lothringen classes, six light cruisers not exceeding 6,000 long tons each, twelve destroyers, and twelve torpedo boats, with all other warships required to be scrapped or surrendered.[12] Submarines were explicitly banned, as were aircraft carriers, heavy cruisers, and any form of naval aviation, while personnel was capped at 15,000 officers and enlisted men, prohibiting conscription and emphasizing a professional cadre focused on training rather than combat readiness.[13] These measures effectively reduced the navy to a coastal defense force incapable of blue-water operations.[14] The remnants of the Imperial German Navy, known as the Kaiserliche Marine, were reorganized into the Provisional Reichsmarine on April 1, 1919, under the Weimar Republic, retaining select vessels such as the pre-dreadnoughts Schlesien and Schleswig-Holstein to meet treaty quotas.[15] The Reichsmarine prioritized personnel development and technical expertise, constructing a few compliant light cruisers like the Emden (commissioned 1925) and the Königsberg-class vessels to replace obsolete units, while maintaining a small inventory of torpedo boats and destroyers for training purposes.[16] This era saw a shift toward qualitative improvements, with rigorous officer training programs designed to preserve institutional knowledge for potential future expansion, despite the treaty's prohibitions on offensive capabilities.[17] Erich Raeder, a veteran of World War I, assumed command as Chief of the Naval Command on October 1, 1928, succeeding Admiral Hans Zenker and steering the Reichsmarine toward subtle enhancements within treaty bounds.[18] Under Raeder's leadership, efforts focused on maintaining morale and expertise amid economic constraints of the Weimar era. To circumvent the submarine ban, the Reichsmarine engaged in covert activities, including the establishment of the Ingenieurskantoor voor Scheepsbouw (IvS), a front company in the Netherlands, where German engineers developed submarine designs and trained personnel discreetly from the early 1920s.[19] These violations, exposed in scandals like the 1928 Lohmann Affair, underscored the navy's determination to retain prohibited technologies for eventual rearmament, though they remained limited in scale until the treaty's repudiation in the 1930s.[20]

Nazi Ascension and Initial Expansion

Adolf Hitler's appointment as Chancellor on 30 January 1933 enabled Admiral Erich Raeder, who had commanded the Reichsmarine since 1928, to intensify covert rearmament efforts in violation of the Treaty of Versailles, which capped naval tonnage at 100,000 tons for surface ships and banned submarines and capital ships beyond outdated vessels.[21][16] On 16 March 1935, Hitler openly repudiated the Versailles Treaty's military clauses, proclaiming the restoration of conscription, the creation of the Luftwaffe, and naval expansion to include modern warships.[22] This announcement facilitated the renaming of the Reichsmarine to Kriegsmarine via the Law for the Reconstruction of the National Defense Forces, effective 21 May 1935, signaling a transition to an offensive-oriented force under Raeder's leadership.[23][16] The Anglo-German Naval Agreement, signed on 18 June 1935, provided diplomatic cover by authorizing the Kriegsmarine to build up to 35% of the Royal Navy's surface tonnage—approximately 420,000 tons—and 45% for submarines, effectively nullifying Versailles limits while averting immediate British opposition.[24][16] Early construction prioritized the Deutschland-class pocket battleships, designed as long-range commerce raiders exploiting Versailles loopholes with 11-inch guns and high speed within light cruiser tonnage disguises: Admiral Scheer was commissioned on 12 November 1934, followed by Admiral Graf Spee on 30 January 1936.[16] Parallel efforts launched the Zerstörer 1934 class, the first post-World War I destroyers built in Germany, with four vessels—Z1 Leberecht Maass, Z2 Georg Thiele, Z3 Max Schultz, and Z4 Richard Beitzen—laid down between January 1934 and February 1935 and commissioned by 1937, emphasizing torpedo armament and fleet escort capabilities.[25][16]Plan Z and Long-Term Naval Ambitions

Plan Z, a long-term naval rearmament program initiated in 1938 and formally approved by Adolf Hitler in January 1939, aimed to transform the Kriegsmarine into a balanced fleet capable of challenging Royal Navy dominance in home waters and beyond.[26] The blueprint targeted completion by 1944–1948, specifying 10 battleships, 3 battlecruisers, 4 aircraft carriers, 15 Panzerschiffe (pocket battleships), 5 heavy cruisers, 44 light cruisers, 68 destroyers, 90 torpedo boats, and 240 U-boats, alongside extensive minelaying and auxiliary forces.[27] This composition sought to enable decisive surface engagements while supporting commerce warfare, reflecting Grand Admiral Erich Raeder's advocacy for a "risk fleet" that could force Britain into a two-front naval commitment.[26] The plan's ambitions stemmed from Germany's geopolitical imperatives: countering British encirclement through a fleet ratio approaching 1:3 against the Royal Navy, as permitted under the 1935 Anglo-German Naval Agreement, but expanded covertly to project power into the Atlantic.[28] Projected costs exceeded 33 billion Reichsmarks over eight years, with initial construction—such as the aircraft carrier Graf Zeppelin (laid down 1936) and H-class battleships (two started July 1939)—prioritizing heavy units to deter or defeat British squadrons in fleet actions.[27] Raeder envisioned carriers providing air cover absent from battleships, battlecruisers for raiding, and U-boats for attrition, forming a synergistic force unbound by Versailles-era restrictions.[26] Resource limitations, however, exposed the plan's impracticality from inception. Hitler's strategic focus on rapid continental conquests favored the army's panzer divisions and Luftwaffe's bombers, subordinating naval steel allocations despite Raeder's lobbying; by 1938, ground and air forces consumed over 80% of armaments spending.[29] Germany's shipbuilding infrastructure, concentrated in yards like Blohm & Voss and Deutsche Werke, lacked capacity for simultaneous heavy-ship construction—evidenced by pre-war output of just two battleships (Bismarck and Tirpitz)—while skilled labor shortages and import dependencies constrained scaling.[30] Steel deficits further undermined feasibility, with production rising to 22.8 million tons in 1938 yet rationed amid competing demands; naval needs competed directly with tank and aircraft fabrication, where each battleship required 30,000–50,000 tons of specialized alloy steel, equivalent to hundreds of panzers.[31] [32] Empirical assessments of industrial throughput indicate that full Plan Z execution would have demanded 2–3 times the 1930s naval yard output, diverting resources from Hitler's prioritized land-air blitzkrieg doctrine and risking economic overheating without Swedish ore imports or synthetic alternatives scaling adequately.[30] Consequently, only skeletal progress occurred before September 1939, with unbuilt hulls later repurposed for submarines amid wartime exigencies.[26]Pre-War Engagements and Preparations

Spanish Civil War Operations

The Kriegsmarine's involvement in the Spanish Civil War (1936–1939) marked its first operational deployment, conducted under the pretext of enforcing the international non-intervention agreement while providing covert support to Francisco Franco's Nationalist forces.[33] Following the outbreak of hostilities on July 17, 1936, German naval units, including pocket battleships Deutschland and Admiral Scheer as well as light cruiser Leipzig, were dispatched to Spanish waters starting July 23, 1936, for patrols ostensibly monitoring arms shipments but effectively aiding Nationalist blockade efforts and reconnaissance.[34] These operations allowed testing of shipboard systems, anti-aircraft defenses, and crew endurance in a combat environment, though engagements remained limited to avoid broader escalation.[35] A pivotal incident occurred on May 29, 1937, when the Deutschland, anchored off Ibiza, was struck by two bombs from Soviet Tupolev SB bombers operated by the Republican Air Force, resulting in 31 sailors killed and 101 wounded; one bomb damaged guns and ignited fires in crew spaces, while the other destroyed a floatplane.[36] In retaliation, on May 31, 1937, Admiral Scheer—supported by four destroyers—shelled the Republican-held port of Almería, firing over 300 rounds from 28 cm main guns and secondary armament, destroying oil tanks, warehouses, and causing an estimated 19–35 civilian deaths alongside military targets.[37] This action, ordered by Adolf Hitler, demonstrated the Kriegsmarine's willingness to apply coercive force and highlighted vulnerabilities in anchored positions, prompting improved vigilance protocols.[38] The light cruiser Leipzig also conducted patrols, suffering a near-miss torpedo strike on June 15, 1938, off Oran, Algeria—attributed to Republican submarines but possibly a misperception—which reinforced lessons on threat identification amid foggy conditions and neutral shipping density.[39] Overall, these deployments inflicted minimal material losses but yielded practical experience in sustained operations, with Admiral Scheer logging extensive mileage for gunnery practice and evacuation of German nationals; total Kriegsmarine casualties numbered around 50, underscoring the risks of proxy conflicts despite nominal neutrality.[40] The episodes validated the value of heavy cruisers for deterrence while exposing coordination challenges with Luftwaffe elements, informing pre-World War II tactics without committing to full-scale commitment.[37]Technological and Tactical Developments

Admiral Karl Dönitz, appointed Befehlshaber der Unterseeboote in October 1936, advanced the concept of Rudeltaktik, or wolfpack tactics, emphasizing massed U-boat attacks on merchant convoys to overwhelm defenses. Drawing from World War I unrestricted submarine warfare observations and interwar analysis, Dönitz conducted trials as early as 1936, refining coordinated search and assault methods that proved effective in simulated exercises against Kriegsmarine vessels mimicking convoys by May 1939. Submarine technology progressed with the Type VII class, designed in the early 1930s to circumvent Versailles Treaty tonnage limits while enhancing ocean-going capabilities. The first Type VIIA boats were laid down in 1933, with commissioning beginning in 1936; these featured a surface speed of 17 knots, a range exceeding 6,500 nautical miles, and capacity for 11 torpedoes, surpassing the coastal-focused Type II predecessors. By 1939, over a dozen Type VII submarines were operational, forming the core of expansion under the 1935 Anglo-German Naval Agreement.[41][30] Surface fleet advancements included modernizations of inherited Reichsmarine vessels and initiation of new builds. Pre-dreadnought battleships Schlesien and Schleswig-Holstein, retained for training, underwent boiler replacements and armament updates in the mid-1930s to extend utility despite obsolescence. Concurrently, construction started on advanced designs like the Scharnhorst-class battlecruisers in 1935, incorporating 28 cm guns and improved armor, alongside destroyers of the 1934A class with enhanced torpedoes and anti-aircraft batteries, prioritizing commerce raiding potential.[16][30] Resource constraints from rearmament priorities limited sensor integration, yet passive hydrophone systems advanced with the Gruppenhorchgerät (GHG), deployed on U-boats from 1936 onward, using arrays of 24 hydrophones for directional underwater detection up to several kilometers. Radar development lagged, with initial surface-search sets like FuMO emerging experimentally by 1937 on select cruisers, relying on meter-wave technology amid competing Luftwaffe demands.[42]Strategic Doctrine and World War II Operations

Overall Naval Strategy Under Hitler

The Kriegsmarine's overarching naval strategy under Adolf Hitler centered on commerce raiding and avoidance of direct fleet engagements with the superior Royal Navy, reflecting Germany's limited industrial capacity and resource constraints relative to Britain's established maritime dominance. This approach stemmed from a realistic assessment of numerical disparities: in September 1939, Germany fielded 57 operational U-boats and a handful of surface combatants, including two battleships, three pocket battleships, and eight cruisers, against a Royal Navy boasting 15 battleships, numerous cruisers, and approximately 184 destroyers.[6][43][16] Plan Z, Hitler's approved expansion blueprint from January 1939, aimed to rectify this imbalance over eight years by constructing a balanced fleet of 10 battleships, 4 aircraft carriers, 3 battlecruisers, 15 pocket battleships, 5 heavy cruisers, 44 light cruisers or flotilla leaders, 68 destroyers, 90 torpedo boats, and 240 submarines, but the premature outbreak of war halted progress, diverting steel and labor to land forces.[44][30] Grand Admiral Erich Raeder, as Oberbefehlshaber der Kriegsmarine, championed this surface-oriented "balanced fleet" doctrine, drawing from interwar analyses of World War I's Jutland battle to envision opportunistic raids and eventual decisive actions against divided British forces, rather than a Mahanist confrontation of battle lines.[45] Raeder's vision prioritized capital ships for prestige and deterrence, influencing early commerce raider deployments like the pocket battleships Deutschland, Admiral Scheer, and Admiral Graf Spee, designed to disrupt trade routes while forcing the Royal Navy to disperse its assets.[16] However, this strategy presupposed prolonged peacetime buildup, which Hitler's focus on rapid continental conquests undermined, as naval allocations remained subordinate to Heer expansion, capping the fleet at roughly 10% of total defense spending by 1939.[17] In opposition, Commodore Karl Dönitz, commanding the U-boat force from 1936, advocated an asymmetric submarine-centric strategy, arguing in a September 1939 memorandum that surface vessels were too vulnerable to air and radar threats in a total war scenario, and urging immediate production of 300 Type VII U-boats to target merchant convoys en masse using wolfpack tactics.[14] Dönitz's position gained traction post-war outbreak, as initial U-boat successes demonstrated commerce interdiction's potential to economically cripple Britain without risking capital ships, aligning with causal constraints of inferior shipbuilding capacity—Germany produced only 23 new U-boats in 1939-1940, versus Britain's convoy escort buildup.[46] Hitler's directives introduced inconsistencies, as he endorsed Raeder's prestige-driven surface ambitions for political signaling—such as parading battleships like Bismarck—while intervening sporadically to align naval efforts with land priorities, exemplified by resource reallocations after Poland's invasion and reluctance to escalate unrestricted submarine warfare early, fearing U.S. entry.[47] This reflected Hitler's expectation of a swift European victory, rendering a global naval challenge unnecessary, yet it perpetuated a hybrid strategy ill-suited to sustained attrition, with surface raiders tying down U-boat escorts and diluting focus on tonnage warfare.[48][49]Early Campaigns: Poland, Scandinavia, and France

The Kriegsmarine's involvement in the invasion of Poland began on 1 September 1939, when the pre-dreadnought battleship Schleswig-Holstein, ostensibly on a goodwill visit to Danzig, commenced bombardment of the Polish Westerplatte ammunition depot at 4:45 a.m., firing the opening salvos of World War II in Europe.[50][51] This action supported marine infantry assaults, with the Polish garrison holding out until surrendering on 7 September after seven days of resistance.[52] Concurrently, light surface units engaged in the Battle of Danzig Bay, where German destroyers and torpedo boats neutralized Polish minelayers and submarines, preventing effective counteraction by the small Polish fleet.[53] To secure approaches against British and French naval response, the Kriegsmarine initiated defensive mining in the North Sea, employing destroyers, torpedo boats, and minelayers to establish barrages close to German coasts.[54] In the Scandinavian theater, Operation Weserübung commenced on 9 April 1940 with amphibious assaults on Denmark and Norway, utilizing the bulk of the Kriegsmarine's surface fleet—including heavy cruiser Blücher, light cruisers, 10 destroyers, and transports—to land roughly 100,000 troops at key ports from Narvik to Oslo.[55] Denmark surrendered the same day, but Norwegian defenses inflicted severe damage: Blücher was sunk by coastal batteries at Oscarsborg Fortress in Oslofjord, claiming about 1,000 lives and delaying the capital's capture.[56] The campaign exacted a heavy toll, with the Kriegsmarine losing one heavy cruiser, one light cruiser (Königsberg, air-attacked in Bergen), 10 destroyers, and over 2,300 personnel at sea, alongside 3,700 ground casualties.[56][55] Despite these irreplaceable losses—representing nearly half the destroyers and significant cruiser tonnage—the operation achieved strategic victory by mid-June, securing Norway's ports, denying Allied occupation, and safeguarding Swedish iron ore shipments vital to German industry.[56] During the Battle of France from 10 May to 25 June 1940, Kriegsmarine surface operations remained peripheral to the land-air blitzkrieg, focusing on mine warfare to protect flanks and contest the Channel.[57] Destroyers and specialized minelayers sowed extensive fields in the North Sea and English Channel approaches, including barrages off the Thames Estuary and Dover Straits, to deter British naval movements and coastal raids.[58][57] Direct fleet engagements were minimal, as Royal Navy superiority precluded major sorties, though E-boats and minesweepers supported coastal advances. Following the French armistice on 22 June, German occupation extended to Atlantic harbors—Brest, Lorient, Saint-Nazaire, La Pallice, and Bordeaux—yielding fortified bases that bypassed North Sea chokepoints for direct ocean access.[59] These facilities enhanced operational reach, though initial exploitation emphasized defensive consolidation over immediate offensive projection.[60]Battle of the Atlantic: U-Boat Dominance and Decline