Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Sound recording and reproduction

View on Wikipedia

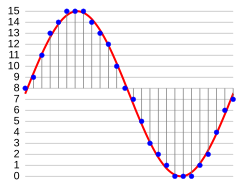

Sound recording and reproduction is the electrical, mechanical, electronic, or digital inscription and re-creation of sound waves, such as spoken voice, singing, instrumental music, or sound effects. The two main classes of sound recording technology are analog recording and digital recording.

Acoustic analog recording is achieved by a microphone diaphragm that senses changes in atmospheric pressure caused by acoustic sound waves and records them as a mechanical representation of the sound waves on a medium such as a phonograph record (in which a stylus cuts grooves on a record). In magnetic tape recording, the sound waves vibrate the microphone diaphragm and are converted into a varying electric current, which is then converted to a varying magnetic field by an electromagnet, which makes a representation of the sound as magnetized areas on a plastic tape with a magnetic coating on it. Analog sound reproduction is the reverse process, with a larger loudspeaker diaphragm causing changes to atmospheric pressure to form acoustic sound waves.

Digital recording and reproduction converts the analog sound signal picked up by the microphone to a digital form by the process of sampling. This lets the audio data be stored and transmitted by a wider variety of media. Digital recording stores audio as a series of binary numbers (zeros and ones) representing samples of the amplitude of the audio signal at equal time intervals, at a sample rate high enough to convey all sounds capable of being heard. A digital audio signal must be reconverted to analog form during playback before it is amplified and connected to a loudspeaker to produce sound.

Early history

[edit]

Long before sound was first recorded, music was recorded—first by written music notation, then also by mechanical devices (e.g., wind-up music boxes, in which a mechanism turns a spindle, which plucks metal tines, thus reproducing a melody). Automatic music reproduction traces back as far as the 9th century, when the Banū Mūsā brothers invented the earliest known mechanical musical instrument, in this case, a hydropowered (water-powered) organ that played interchangeable cylinders. According to Charles B. Fowler, this "... cylinder with raised pins on the surface remained the basic device to produce and reproduce music mechanically until the second half of the nineteenth century."[1][2]

Carvings in the Rosslyn Chapel from the 1560s may represent an early attempt to record the Chladni patterns produced by sound-in-stone representations, although this theory has not been conclusively proved.[3][4]

In the 14th century, a mechanical bell-ringer controlled by a rotating cylinder was introduced in Flanders.[citation needed] Similar designs appeared in barrel organs (15th century), musical clocks (1598), barrel pianos (1805), and music boxes (c. 1800). A music box is an automatic musical instrument that produces sounds by the use of a set of pins placed on a revolving cylinder or disc so as to pluck the tuned teeth (or lamellae) of a steel comb.

The fairground organ, developed in 1892, used a system of accordion-folded punched cardboard books. The player piano, first demonstrated in 1876, used a punched paper scroll that could store a long piece of music. The most sophisticated of the piano rolls were hand-played, meaning that they were duplicates from a master roll that had been created on a special piano, which punched holes in the master as a live performer played the song. Thus, the roll represented a recording of the actual performance of an individual, not just the more common method of punching the master roll through transcription of the sheet music. This technology to record a live performance onto a piano roll was not developed until 1904. Piano rolls were in continuous mass production from 1896 to 2008.[5][6] A 1908 U.S. Supreme Court copyright case noted that, in 1902 alone, there were between 70,000 and 75,000 player pianos manufactured, and between 1,000,000 and 1,500,000 piano rolls produced.[7]

Phonautograph

[edit]The first device that could record actual sounds as they passed through the air, (but could not play them back—the purpose was only visual study) was the phonautograph, patented in 1857 by Parisian inventor Édouard-Léon Scott de Martinville. The earliest known recordings of the human voice are phonautograph recordings, called phonautograms, made in 1857.[8] They consist of sheets of paper with sound-wave-modulated white lines created by a vibrating stylus that cut through a coating of soot as the paper was passed under it. An 1860 phonautogram of "Au Clair de la Lune", a French folk song, was played back as sound for the first time in 2008 by scanning it and using software to convert the undulating line, which graphically encoded the sound, into a corresponding digital audio file.[8][9]

Phonograph

[edit]Thomas Edison's work on two other innovations, the telegraph and the telephone, led to the development of the phonograph. Edison was working on a machine in 1877 that would transcribe telegraphic signals onto paper tape, which could then be transferred over the telegraph again and again. The phonograph was both in a cylinder and a disc form.[citation needed]

Cylinder

[edit]On April 30, 1877, French poet, humorous writer and inventor Charles Cros submitted a sealed envelope containing a letter to the Academy of Sciences in Paris fully explaining his proposed method, called the paleophone.[10] Though no trace of a working paleophone was ever found, Cros is remembered by some historians as an early inventor of a sound recording and reproduction machine.[11]

The first practical sound recording and reproduction device was the mechanical phonograph cylinder; invented by Thomas Edison in 1877 and patented in 1878.[12][13] The invention soon spread across the globe and over the next two decades the commercial recording, distribution, and sale of sound recordings became a growing new international industry, with the most popular titles selling millions of units by the early 1920s.[14] A process for mass-producing duplicate wax cylinders by molding instead of engraving them was put into effect in 1901.[15] The development of mass-production techniques enabled cylinder recordings to become a major new consumer item in industrial countries and the cylinder was the main consumer format from the late 1880s until around 1910.[citation needed]

Disc

[edit]

The next major technical development was the invention of the gramophone record, generally credited to Emile Berliner[by whom?] and patented in 1887,[16] though others had demonstrated similar disk apparatus earlier, most notably Alexander Graham Bell in 1881.[17] Discs were easier to manufacture, transport and store, and they had the additional benefit of being marginally louder than cylinders. Sales of the gramophone record overtook the cylinder ca. 1910, and by the end of World War I the disc had become the dominant commercial recording format. Edison, who was the main producer of cylinders, created the Edison Disc Record in an attempt to regain his market. The double-sided (nominally 78 rpm) shellac disc was the standard consumer music format from the early 1910s to the late 1950s. In various permutations, the audio disc format became the primary medium for consumer sound recordings until the end of the 20th century.

Although there was no universally accepted speed, and various companies offered discs that played at several different speeds, the major recording companies eventually settled on a de facto industry standard of nominally 78 revolutions per minute. The specified speed was 78.26 rpm in America and 77.92 rpm throughout the rest of the world. The difference in speeds was due to the difference in the cycle frequencies of the AC electricity that powered the stroboscopes used to calibrate recording lathes and turntables.[18] The nominal speed of the disc format gave rise to its common nickname, the seventy-eight (though not until other speeds had become available). Discs were made of shellac or similar brittle plastic-like materials, played with needles made from a variety of materials including mild steel, thorn, and even sapphire. Discs had a distinctly limited playing life that varied depending on how they were manufactured.

Earlier, purely acoustic methods of recording had limited sensitivity and frequency range. Mid-frequency range notes could be recorded, but very low and very high frequencies could not. Instruments such as the violin were difficult to transfer to disc. One technique to deal with this involved using a Stroh violin, which uses a conical horn connected to a diaphragm that in turn is connected to the violin bridge. The horn was no longer needed once electrical recording was developed.

The long-playing 331⁄3 rpm microgroove LP record, was developed at Columbia Records and introduced in 1948. The short-playing but convenient 7-inch (18 cm) 45 rpm microgroove vinyl single was introduced by RCA Victor in 1949. In the US and most developed countries, the two new vinyl formats completely replaced 78 rpm shellac discs by the end of the 1950s, but in some corners of the world, the 78 lingered on far into the 1960s.[19] Vinyl was much more expensive than shellac, one of the several factors that made its use for 78 rpm records very unusual, but with a long-playing disc the added cost was acceptable. The compact 45 format required very little material. Vinyl offered improved performance, both in stamping and in playback. Vinyl records were, over-optimistically, advertised as "unbreakable". They were not, but they were much less fragile than shellac, which had itself once been touted as unbreakable compared to wax cylinders.

Electrical

[edit]

Sound recording began as a purely mechanical process. Except for a few crude telephone-based recording devices with no means of amplification, such as the telegraphone,[a] it remained so until the 1920s. Between the invention of the phonograph in 1877 and the first commercial digital recordings in the early 1970s, arguably the most important milestone in the history of sound recording was the introduction of what was then called electrical recording, in which a microphone was used to convert the sound into an electrical signal that was amplified and used to actuate the recording stylus. This innovation eliminated the horn sound resonances characteristic of the acoustic process, produced clearer and more full-bodied recordings by greatly extending the useful range of audio frequencies, and allowed previously unrecordable distant and feeble sounds to be captured. During this time, several radio-related developments in electronics converged to revolutionize the recording process. These included improved microphones and auxiliary devices such as electronic filters, all dependent on electronic amplification to be of practical use in recording.

In 1906, Lee De Forest invented the Audion triode vacuum tube, an electronic valve that could amplify weak electrical signals. By 1915, it was in use in long-distance telephone circuits that made conversations between New York and San Francisco practical. Refined versions of this tube were the basis of all electronic sound systems until the commercial introduction of the first transistor-based audio devices in the mid-1950s.

During World War I, engineers in the United States and Great Britain worked on ways to record and reproduce various sounds, including German U-boat for training purposes. Acoustical recording methods of the time could not reproduce the sounds accurately. The earliest results were not promising.

The first electrical recording issued to the public, with little fanfare, was of the November 11, 1920, funeral service for The Unknown Warrior in Westminster Abbey, London. The recording engineers used microphones of the type used in contemporary telephones. Four were discreetly set up in the abbey and wired to recording equipment in a vehicle outside. Although electronic amplification was used, the audio was weak and unclear, as only possible in those circumstances. For several years, this little-noted disc remained the only issued electrical recording.

Several record companies and independent inventors, notably Orlando Marsh, experimented with equipment and techniques for electrical recording in the early 1920s. Marsh's electrically recorded Autograph Records were already being sold to the public in 1924, a year before the first such offerings from the major record companies, but their overall sound quality was too low to demonstrate any obvious advantage over traditional acoustical methods. Marsh's microphone technique was idiosyncratic and his work had little if any impact on the systems being developed by others.[20]

Telephone industry giant Western Electric had research laboratories[b] with material and human resources that no record company or independent inventor could match. They had the best microphone, a condenser type developed there in 1916 and greatly improved in 1922,[21] and the best amplifiers and test equipment. They had already patented an electromechanical recorder in 1918, and in the early 1920s, they decided to intensively apply their hardware and expertise to developing two state-of-the-art systems for electronically recording and reproducing sound: one that employed conventional discs and another that recorded optically on motion picture film. Their engineers pioneered the use of mechanical analogs of electrical circuits and developed a superior rubber line recorder for cutting the groove into the wax master in the disc recording system.[22]

By 1924, such dramatic progress had been made that Western Electric arranged a demonstration for the two leading record companies, the Victor Talking Machine Company and the Columbia Phonograph Company. Both soon licensed the system and both made their earliest published electrical recordings in February 1925, but neither actually released them until several months later. To avoid making their existing catalogs instantly obsolete, the two long-time archrivals agreed privately not to publicize the new process until November 1925, by which time enough electrically recorded repertory would be available to meet the anticipated demand. During the next few years, the lesser record companies licensed or developed other electrical recording systems. By 1929 only the budget label Harmony was still issuing new recordings made by the old acoustic process.

Comparison of some surviving Western Electric test recordings with early commercial releases indicates that the record companies artificially reduced the frequency range of recordings so they would not overwhelm non-electronic playback equipment, which reproduced very low frequencies as an unpleasant rattle and rapidly wore out discs with strongly recorded high frequencies.[citation needed]

Optical and magnetic

[edit]

In the 1920s, Phonofilm and other early motion picture sound systems employed optical recording technology, in which the audio signal was graphically recorded on photographic film. The amplitude variations comprising the signal were used to modulate a light source which was imaged onto the moving film through a narrow slit, allowing the signal to be photographed as variations in the density or width of a sound track. The projector used a steady light and a photodetector to convert these variations back into an electrical signal, which was amplified and sent to loudspeakers behind the screen.[c] Optical sound became the standard motion picture audio system throughout the world and remains so for theatrical release prints despite attempts in the 1950s to substitute magnetic soundtracks. Currently, all release prints on 35 mm movie film include an analog optical soundtrack, usually stereo with Dolby SR noise reduction. In addition, an optically recorded digital soundtrack in Dolby Digital or Sony SDDS form is likely to be present. An optically recorded timecode is also commonly included to synchronize CDROMs that contain a DTS soundtrack.

This period also saw several other historic developments including the introduction of the first practical magnetic sound recording system, the magnetic wire recorder, which was based on the work of Danish inventor Valdemar Poulsen. Magnetic wire recorders were effective, but the sound quality was poor, so between the wars, they were primarily used for voice recording and marketed as business dictating machines. In 1924, a German engineer, Kurt Stille, improved the Telegraphone with an electronic amplifier.[23] The following year, Ludwig Blattner began work that eventually produced the Blattnerphone,[24] which used steel tape instead of wire. The BBC started using Blattnerphones in 1930 to record radio programs. In 1933, radio pioneer Guglielmo Marconi's company purchased the rights to the Blattnerphone, and newly developed Marconi-Stille recorders were installed in the BBC's Maida Vale Studios in March 1935.[25] The tape used in Blattnerphones and Marconi-Stille recorders was the same material used to make razor blades, and not surprisingly the fearsome Marconi-Stille recorders were considered so dangerous that technicians had to operate them from another room for safety. Because of the high recording speeds required, they used enormous reels about one meter in diameter, and the thin tape frequently broke, sending jagged lengths of razor steel flying around the studio.

Tape

[edit]

Magnetic tape recording uses an amplified electrical audio signal to generate analogous variations of the magnetic field produced by a tape head, which impresses corresponding variations of magnetization on the moving tape. In playback mode, the signal path is reversed, the tape head acting as a miniature electric generator as the varyingly magnetized tape passes over it.[26] The original solid steel ribbon was replaced by a much more practical coated paper tape, but acetate soon replaced paper as the standard tape base. Acetate has fairly low tensile strength and if very thin it will snap easily, so it was in turn eventually superseded by polyester. This technology, the basis for almost all commercial recording from the 1950s to the 1980s, was developed in the 1930s by German audio engineers who also rediscovered the principle of AC biasing (first used in the 1920s for wire recorders), which dramatically improved the frequency response of tape recordings. The K1 Magnetophon was the first practical tape recorder, developed by AEG in Germany in 1935. The technology was further improved just after World War II by American audio engineer John T. Mullin with backing from Bing Crosby Enterprises. Mullin's pioneering recorders were modifications of captured German recorders. In the late 1940s, the Ampex company produced the first tape recorders commercially available in the US.

Magnetic tape brought about sweeping changes in both radio and the recording industry. Sound could be recorded, erased and re-recorded on the same tape many times, sounds could be duplicated from tape to tape with only minor loss of quality, and recordings could now be very precisely edited by physically cutting the tape and rejoining it.

Within a few years of the introduction of the first commercial tape recorder—the Ampex 200 model, launched in 1948—American musician-inventor Les Paul had invented the first multitrack tape recorder, ushering in another technical revolution in the recording industry. Tape made possible the first sound recordings totally created by electronic means, opening the way for the bold sonic experiments of the Musique Concrète school and avant-garde composers like Karlheinz Stockhausen, which in turn led to the innovative pop music recordings of artists such as the Beatles and the Beach Boys.

The ease and accuracy of tape editing, as compared to the cumbersome disc-to-disc editing procedures previously in some limited use, together with tape's consistently high audio quality, finally convinced radio networks to routinely prerecord their entertainment programming, most of which had formerly been broadcast live. Also, for the first time, broadcasters, regulators and other interested parties were able to undertake comprehensive audio logging of each day's radio broadcasts. Innovations like multitracking and tape echo allowed radio programs and advertisements to be produced to a high level of complexity and sophistication. The combined impact with innovations such as the endless loop broadcast cartridge led to significant changes in the pacing and production style of radio program content and advertising.

Stereo and hi-fi

[edit]In 1881, it was noted during experiments in transmitting sound from the Paris Opera that it was possible to follow the movement of singers on the stage if earpieces connected to different microphones were held to the two ears. This discovery was commercialized in 1890 with the Théâtrophone system, which operated for over forty years until 1932. In 1931, Alan Blumlein, a British electronics engineer working for EMI, designed a way to make the sound of an actor in a film follow his movement across the screen. In December 1931, he submitted a patent application including the idea, and in 1933, this became UK patent number 394,325.[27] Over the next two years, Blumlein developed stereo microphones and a stereo disc-cutting head, and recorded a number of short films with stereo soundtracks.

In the 1930s, experiments with magnetic tape enabled the development of the first practical commercial sound systems that could record and reproduce high-fidelity stereophonic sound. The experiments with stereo during the 1930s and 1940s were hampered by problems with synchronization. A major breakthrough in practical stereo sound was made by Bell Laboratories, who in 1937 demonstrated a practical system of two-channel stereo, using dual optical sound tracks on film.[28] Major movie studios quickly developed three-track and four-track sound systems, and the first stereo sound recording for a commercial film was made by Judy Garland for the MGM movie Listen, Darling in 1938.[citation needed] The first commercially released movie with a stereo soundtrack was Walt Disney's Fantasia, released in 1940. The 1941 release of Fantasia used the Fantasound sound system. This system used a separate film for the sound, synchronized with the film carrying the picture. The sound film had four double-width optical soundtracks, three for left, center, and right audio—and a fourth as a control track with three recorded tones that controlled the playback volume of the three audio channels. Because of the complex equipment this system required, Disney exhibited the movie as a roadshow, and only in the United States. Regular releases of the movie used standard mono optical 35 mm stock until 1956, when Disney released the film with a stereo soundtrack that used the Cinemascope four-track magnetic sound system.

German audio engineers working on magnetic tape developed stereo recording by 1941. Of 250 stereophonic recordings made during WW2, only three survive: Beethoven's 5th Piano Concerto with Walter Gieseking and Arthur Rother, a Brahms Serenade, and the last movement of Bruckner's 8th Symphony with Von Karajan.[d] Other early German stereophonic tapes are believed to have been destroyed in bombings. Not until Ampex introduced the first commercial two-track tape recorders in the late 1940s did stereo tape recording become commercially feasible. Despite the availability of multitrack tape, stereo did not become the standard system for commercial music recording for some years, and remained a specialist market during the 1950s. EMI (UK) was the first company to release commercial stereophonic tapes. They issued their first Stereosonic tape in 1954. Others quickly followed, under their His Master's Voice and Columbia labels. 161 Stereosonic tapes were released, mostly classical music or lyric recordings. RCA imported these tapes into the USA. Although some British His Master's Voice imports released in the USA cost up to $15, two-track stereophonic tapes were more successful in America during the second half of the 1950s.

The history of stereo recording changed after the late 1957 introduction of the Westrex stereo phonograph disc, which used the groove format developed earlier by Blumlein. Decca Records in England came out with FFRR (Full Frequency Range Recording) in the 1940s, which became internationally accepted as a worldwide standard for higher-quality recording on vinyl records. The Ernest Ansermet recording of Igor Stravinsky's Petrushka was key in the development of full frequency range records and alerting the listening public to high fidelity in 1946.[29]

Until the mid-1960s, record companies mixed and released most popular music in monophonic sound. From mid-1960s until the early 1970s, major recordings were commonly released in both mono and stereo. Recordings originally released only in mono have been re-rendered and released in stereo using a variety of techniques from remixing to pseudostereo.

1950s to 1980s

[edit]Magnetic tape transformed the recording industry. By the early 1950s, most commercial recordings were mastered on tape instead of recorded directly to disc. Tape facilitated a degree of manipulation in the recording process that was impractical with mixes and multiple generations of directly recorded discs. An early example is Les Paul's 1951 recording of How High the Moon, on which Paul played eight overdubbed guitar tracks.[30] In the 1960s Brian Wilson of The Beach Boys, Frank Zappa, and The Beatles (with producer George Martin) were among the first popular artists to explore the possibilities of multitrack recording techniques and effects on their landmark albums Pet Sounds,[31] Freak Out!, and Sgt. Pepper's Lonely Hearts Club Band.[32]

The next important innovation was small cartridge-based tape systems, of which the compact cassette, commercialized by the Philips electronics company in 1964, is the best known. Initially a low-fidelity format for spoken-word voice recording and inadequate for music reproduction, after a series of improvements it entirely replaced the competing consumer tape formats: the larger 8-track tape[33] (used primarily in cars). The compact cassette became a major consumer audio format and advances in electronic and mechanical miniaturization led to the development of the Sony Walkman, a pocket-sized cassette player introduced in 1979. The Walkman was the first personal music player and it gave a major boost to sales of prerecorded cassettes.[34]

A key advance in audio fidelity came with the Dolby A noise reduction system, invented by Ray Dolby and introduced into professional recording studios in 1966. It suppressed the background of hiss, which was the only easily audible downside of mastering on tape instead of recording directly to disc.[35] A competing system, dbx, invented by David Blackmer,[36] also found success in professional audio.[37] A simpler consumer variant of Dolby's noise reduction system, known as Dolby B, greatly improved the sound of cassette tape recordings by reducing the especially high level of hiss that resulted from the cassette's miniaturized tape format and slow tape speed. The compact cassette format also benefited from improvements to the tape itself as coatings with wider frequency responses and lower inherent noise were developed, often based on cobalt and chrome oxides as the magnetic material instead of the more usual iron oxide.

The multitrack audio cartridge had been in wide use in the radio industry, from the late 1950s to the 1980s, but in the 1960s the pre-recorded 8-track tape was launched as a consumer audio format by the Lear Jet aircraft company.[e] Aimed particularly at the automotive market, they were the first practical, affordable car hi-fi systems, and could produce sound quality superior to that of the compact cassette. The smaller size and greater durability – augmented by the ability to create home-recorded music mixtapes since 8-track recorders were rare – saw the cassette become the dominant consumer format for portable audio devices in the 1970s and 1980s.[38]

There had been experiments with multi-channel sound for many years – usually for special musical or cultural events – but the first commercial application of the concept came in the early 1970s with the introduction of Quadraphonic sound. This spin-off development from multitrack recording used four tracks (instead of the two used in stereo) and four speakers to create a 360-degree audio field around the listener.[39] Following the release of the first consumer 4-channel hi-fi systems, a number of popular albums were released in one of the competing four-channel formats; among the best known are Mike Oldfield's Tubular Bells and Pink Floyd's The Dark Side of the Moon. Quadraphonic sound was not a commercial success, partly because of competing and somewhat incompatible four-channel sound systems (e.g., CBS, JVC, Dynaco and others all had systems) and generally poor quality, even when played as intended on the correct equipment, of the released music. It eventually faded out in the late 1970s, although this early venture paved the way for the eventual introduction of domestic surround sound systems in home theatre use, which gained popularity following the introduction of the DVD.[40]

Audio components

[edit]The replacement of the relatively fragile vacuum tube by the smaller, rugged and efficient transistor also accelerated the sale of consumer high-fidelity sound systems from the 1960s onward. In the 1950s, most record players were monophonic and had relatively low sound quality. Few consumers could afford high-quality stereophonic sound systems. In the 1960s, American manufacturers introduced a new generation of modular hi-fi components — separate turntables, pre-amplifiers, amplifiers, both combined as integrated amplifiers, tape recorders, and other ancillary equipment like the graphic equalizer, which could be connected together to create a complete home sound system. These developments were rapidly taken up by major Japanese electronics companies, which soon flooded the world market with relatively affordable, high-quality transistorized audio components. By the 1980s, corporations like Sony had become world leaders in the music recording and playback industry.

Digital

[edit]

The advent of digital sound recording and later the compact disc (CD) in 1982 brought significant improvements in the quality and durability of recordings. The CD initiated another massive wave of change in the consumer music industry, with vinyl records effectively relegated to a small niche market by the mid-1990s. The record industry fiercely resisted the introduction of digital systems, fearing wholesale piracy on a medium able to produce perfect copies of original released recordings.

The most recent and revolutionary developments have been in digital recording, with the development of various uncompressed and compressed digital audio file formats, processors capable and fast enough to convert the digital data to sound in real time, and inexpensive mass storage.[41] This generated new types of portable digital audio players. The minidisc player, using ATRAC compression on small, re-writeable discs was introduced in the 1990s, but became obsolescent as solid-state non-volatile flash memory dropped in price. As technologies that increase the amount of data that can be stored on a single medium, such as Super Audio CD, DVD-A, Blu-ray Disc, and HD DVD became available, longer programs of higher quality fit onto a single disc. Sound files are readily downloaded from the Internet and other sources, and copied onto computers and digital audio players. Digital audio technology is now used in all areas of audio, from casual use of music files of moderate quality to the most demanding professional applications. New applications such as internet radio and podcasting have appeared.

Technological developments in recording, editing, and consuming have transformed the record, movie and television industries in recent decades. Audio editing became practicable with the invention of magnetic tape recording, but technologies like MIDI, sound synthesis and digital audio workstations allow greater control and efficiency for composers and artists. Digital audio techniques and mass storage have reduced recording costs such that high-quality recordings can be produced in small studios.[42]

Today, the process of making a recording is separated into tracking, mixing and mastering. Multitrack recording makes it possible to capture signals from several microphones, or from different takes to tape, disc or mass storage allowing previously unavailable flexibility in the mixing and mastering stages.

Software

[edit]There are many different digital audio recording and processing programs running under several computer operating systems for all purposes, ranging from casual users and serious amateurs working on small projects to professional sound engineers who are recording albums, film scores and doing sound design for video games.

Digital dictation software for recording and transcribing speech has different requirements; intelligibility and flexible playback facilities are priorities, while a wide frequency range and high audio quality are not.

Cultural effects

[edit]

The development of analog sound recording in the nineteenth century and its widespread use throughout the twentieth century had a huge impact on the development of music. Before analog sound recording was invented, most music was as a live performance. Throughout the medieval, Renaissance, Baroque, Classical, and through much of the Romantic music era, the main way that songs and instrumental pieces were recorded was through music notation. While notation indicates the pitches of the melody and their rhythm many aspects of the performance are undocumented. Indeed, in the Medieval era, Gregorian chant did not indicate the rhythm of the chant. In the Baroque era, instrumental pieces often lack a tempo indication[43] and usually none of the ornaments were written down. As a result, each performance of a song or piece would be slightly different.

With the development of analog sound recording, though, a performance could be permanently fixed, in all of its elements: pitch, rhythm, timbre, ornaments and expression. This meant that many more elements of a performance would be captured and disseminated to other listeners. The development of sound recording also enabled a much larger proportion of people to hear famous orchestras, operas, singers and bands, because even if a person could not afford to hear the live concert, they may be able to hear the recording.[44] The availability of sound recording thus helped to spread musical styles to new regions, countries and continents. The cultural influence went in a number of directions. Sound recordings enabled Western music lovers to hear actual recordings of Asian, Middle Eastern and African groups and performers, increasing awareness of non-Western musical styles. At the same time, sound recordings enabled music lovers outside the West to hear the most famous North American and European groups and singers.[45]

As digital recording developed, so did a controversy commonly known as the analog versus digital controversy. Audio professionals, audiophiles, consumers, musicians alike contributed to the debate based on their interaction with the media and the preferences for analog or digital processes.[46] Scholarly discourse on the controversy came to focus on concern for the perception of moving image and sound.[47] There are individual and cultural preferences for either method. While approaches and opinions vary, some emphasize sound as paramount, others focus on technology preferences as the deciding factor. Analog fans might embrace limitations as strengths of the medium inherent in the compositional, editing, mixing, and listening phases.[48] Digital advocates boast flexibility in similar processes. This debate fosters a revival of vinyl in the music industry,[49] as well as analog electronics and analog-type plug-ins for recording and mixing software.

Legal status

[edit]In copyright law, a phonogram or sound recording is a work that results from the fixation of sounds in a medium. The notice of copyright in a phonogram uses the sound recording copyright symbol, which the Geneva Phonograms Convention defines as ℗ (the letter P in a full circle). This usually accompanies the copyright notice for the underlying musical composition, which uses the ordinary © symbol.

The recording is separate from the song, so copyright for a recording usually belongs to the record company. It is less common for an artist or producer to hold these rights. Copyright for sound recordings has existed in the United States since 1972, while copyright for musical composition, or songs, has existed since 1831. Disputes over sampling and beats[clarification needed] are ongoing.[42]

United States

[edit]United States copyright law defines "sound recordings" as "works that result from the fixation of a series of musical, spoken, or other sounds" other than an audiovisual work's soundtrack.[50] Prior to the Sound Recording Amendment (SRA),[51] which took effect in 1972, copyright in sound recordings was handled at the state level. Federal copyright law preempts most state copyright laws but allows state copyright in sound recordings to continue for one full copyright term after the SRA's effective date,[52] which means 2067.

United Kingdom

[edit]Since 1934, copyright law in Great Britain has treated sound recordings (or phonograms) differently from musical works.[53] The Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988 defines a sound recording as (a) a recording of sounds, from which the sounds may be reproduced, or (b) a recording of the whole or any part of a literary, dramatic or musical work, from which sounds reproducing the work or part may be produced, regardless of the medium on which the recording is made or the method by which the sounds are reproduced or produced. It thus covers vinyl records, tapes, compact discs, digital audiotapes, and MP3s that embody recordings.

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ The earliest known surviving electrical recording was made on a telegraphone magnetic recorder at the 1900 Exposition Universelle in Paris. It includes brief comments by Emperor Franz Joseph and the audio quality, ignoring dropouts and some noise of later origin, is comparable to that of a contemporary telephone.

- ^ In 1925 the laboratories reformed into Bell Telephone Laboratories and under the shared ownership of American Telephone & Telegraph Company and Western Electric.

- ^ Ironically, the introduction of talkies was spearheaded by The Jazz Singer (1927), which used the Vitaphone sound-on-disc system rather than an optical soundtrack.

- ^ The Audio Engineering Society has issued all these recordings on CD. Varèse Sarabande had released the Beethoven Concerto on LP, and it has been reissued on CD several times since.

- ^ Although its given name was the Lear Jet Stereo 8, it was seldom referred to as such.

References

[edit]- ^ Fowler, Charles B. (October 1967), "The Museum of Music: A History of Mechanical Instruments", Music Educators Journal, 54 (2), MENC_ The National Association for Music Education: 45–49, doi:10.2307/3391092, JSTOR 3391092, S2CID 190524140

- ^ Koetsier, Teun (2001). "On the prehistory of programmable machines: musical automata, looms, calculators". Mechanism and Machine Theory. 36 (5). Elsevier: 589–603. doi:10.1016/S0094-114X(01)00005-2.

- ^ Mitchell, Thomas (2006). Rosslyn Chapel: The Music of the Cubes. Diversions Books. ISBN 0-9554629-0-8.

- ^ "Tune into the Da Vinci coda". The Scotsman. April 26, 2006. Archived from the original on November 13, 2011. Retrieved November 5, 2011.

- ^ "History of the Pianola - Piano Players". The Pianola Institute. Archived from the original on May 27, 2017. Retrieved May 24, 2017.

- ^ "The day the music died - News - The Buffalo News". June 10, 2011. Archived from the original on June 10, 2011. Retrieved May 24, 2017.

- ^ White-Smith Music Pub. Co. v. Apollo Co.209 U.S. 1 (1908)

- ^ a b "First Sounds". FirstSounds.ORG. March 27, 2008. Archived from the original on December 31, 2017. Retrieved May 24, 2017.

- ^ Jody Rosen (March 27, 2008). "Researchers Play Tune Recorded Before Edison". The New York Times. Archived from the original on July 1, 2017. Retrieved February 23, 2017.

- ^ "L'impression du son", Revue de la BNF, no. 33, Bibliothèque nationale de France, 2009, ISBN 9782717724301, archived from the original on September 28, 2015

- ^ "Origins of Sound Recording: Charles Cros - Thomas Edison National Historical Park (U.S. National Park Service)". www.nps.gov. Retrieved April 14, 2022.

- ^ "Patent Images". patimg1.uspto.gov. Archived from the original on October 30, 2017. Retrieved May 24, 2017.

- ^ History of the Cylinder Phonograph, Library of Congress, archived from the original on August 19, 2016, retrieved November 6, 2018

- ^ Thompson, Clive. "How the Phonograph Changed Music Forever". Smithsonian. Retrieved April 14, 2022.

- ^ "Inventing Entertainment: The Early Motion Pictures and Sound Recordings of the Edison Companies". Library of Congress. Retrieved April 21, 2023.

- ^ U.S. patent 372,786 Gramophone (horizontal recording), original filed May 1887, refiled September 1887, issued November 8, 1887

- ^ "Early Sound Recording Collection and Sound Recovery Project". Smithsonian. Archived from the original on April 23, 2013. Retrieved April 26, 2013.

- ^ Copeland, Peter (2008). Manual of Analogue Audio Restoration Techniques (PDF). London: The British Library. pp. 89–90. Archived (PDF) from the original on December 22, 2015. Retrieved December 16, 2015.

- ^ Jenkins, Amanda (April 13, 2019). "Inside the Archival Box: The First Long-Playing Disc | Now See Hear!". blogs.loc.gov. Retrieved April 14, 2022.

- ^ Allan Sutton, When Did Marsh Laboratories Begin to Make Electrical Recordings?, archived from the original on March 3, 2016

- ^ "A brief summary of E. C. Wente's development of the condenser microphone and of the Western Electric sound recording project as a whole". IEEE Transactions on Education. 35 (4). November 1992. Archived from the original on February 24, 2012. Retrieved July 24, 2015.

- ^ Maxfield, J. P. and H. C. Harrison. Methods of high-quality recording and reproducing of speech based on telephone research. Bell System Technical Journal, July 1926, 493–523.

- ^ Steven Schoenherr (November 5, 2002), The History of Magnetic Recording

- ^ "The Blattnerphone". Orbem.co.uk. January 10, 2010. Archived from the original on April 10, 2014. Retrieved May 24, 2017.

- ^ "The Marconi-Stille Recorder - Page 1". Orbem.co.uk. February 20, 2008. Archived from the original on July 3, 2013. Retrieved May 24, 2017.

- ^ Gordon, Mumma. "Recording". Oxford Music Online. Oxford University Press. Retrieved February 20, 2015.

- ^ GB patent 394325, Alan Dower Blumlein, "Improvements in and relating to Sound-transmission, Sound-recording and Sound-reproducing Systems.", issued June 14, 1933, assigned to Alan Dower Blumlein and Musical Industries, Limited

- ^ "New Sound Effects Achieved in Film", The New York Times, Oct. 12, 1937, p. 27.

- ^ "Decca's (ffrr) Frequency Series - History Of Vinyl 1". Vinylrecordscollector.co.uk. Archived from the original on June 21, 2002. Retrieved May 24, 2017.

- ^ Buskin, Richard. "Classic Tracks: Les Paul & Mary Ford 'How High the Moon'". SoundOnSound. Sound On Sound. Retrieved August 1, 2023.

- ^ Granata, Charles L. (2003). Wouldn't it Be Nice: Brian Wilson and the Making of the Beach Boys' Pet Sounds. Chicago Review Press. ISBN 978-1-55652-507-0.

- ^ Kehew, Brian; Ryan, Kevin (2006). Recording The Beatles. Curvebender Publishing. p. 216. ISBN 0-9785200-0-9.

- ^ Marvin Camras, ed. (1985). Magnetic Tape Recording. Van Nostrand Reinhold. ISBN 978-0-442-21774-7.

- ^ Paul du Gay; Stuart Hall; Linda Janes; Hugh Mackay; Keith Negus (1997). Doing Cultural Studies: The Story of the Sony Walkman. Sage Publications Ltd. ISBN 978-0-7619-5402-6.

- ^ Dolby, Ray (October 1967). "An Audio Noise Reduction System". Journal of the Audio Engineering Society. 15 (4): 383–388. Retrieved September 2, 2023.

- ^ Blackmer, David E. (1972). "A Wide Dynamic Range Noise Reduction System". db Magazine. Vol. 6, no. 8.

- ^ Millard, Andre (2013). "Cassette Tape". St. James Encyclopedia of Popular Culture (2.1 ed.). p. 529.

- ^ Popular Science, p. 86, at Google Books

- ^ "From Quadraphonic To Good Enough Sound". January 21, 2011. Retrieved July 29, 2024.[unreliable source?]

- ^ Kees Schouhamer Immink (March 1991). "The future of digital audio recording". Journal of the Audio Engineering Society. 47: 171–172.

Keynote address was presented to the 104th Convention of the Audio Engineering Society in Amsterdam during the society's golden anniversary celebration on May 17, 1998.

- ^ a b Hull, Geoffrey (2010). The Music Business and Recording Industry. Routledge. ISBN 978-0203843192.

- ^ "How do musicians know how fast to play a piece? And why are the terms in Italian?". Retrieved September 17, 2024.

- ^ Team, Stringovation. "How the Ability to Record Music Changed the Music Industry". Retrieved September 17, 2024.

- ^ "The influence of recording". Retrieved September 17, 2024.

- ^ "Analog vs. Digital: An Unending Debate – PS Audio". February 20, 2021. Retrieved October 14, 2022.

- ^ Sterne, Jonathan (2006). "The death and life of digital audio". Interdisciplinary Science Reviews. 31 (4): 338–348. Bibcode:2006ISRv...31..338S. doi:10.1179/030801806X143277. ISSN 0308-0188. S2CID 146212262.

- ^ INSAM Journal of Contemporary Music, Art and Technology. INSAM Institute for Contemporary Art, Music and Technology. doi:10.51191/issn.2637-1898. S2CID 194358461.

- ^ "Why is vinyl making a comeback? - Reader's Digest". www.readersdigest.co.uk. Retrieved October 15, 2022.

- ^ 17 U.S.C. § 101

- ^ Pub. L. No. 92-140, § 3, 85 Stat. 391, 392 (1971)

- ^ 17 U.S.C. § 301(c)

- ^ Gramophone Co., Ltd. v. Stephen Carwardine Co [1934] 1 Ch 450

- Magnetic tape sound recording and reproducing systems, BSI British Standards, doi:10.3403/00497725 (inactive July 12, 2025), retrieved April 16, 2022

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: DOI inactive as of July 2025 (link)

Further reading

[edit]- Encyclopedia of Recorded Sound (2 Vols.) (2nd ed.). Routledge. 2005 [1993].

- Barlow, Sanna Morrison. Mountain Singing: the Story of Gospel Recordings in the Philippines. Hong Kong: Alliance Press, 1952. 352 p.

- Coleman, Mark, Playback: from the Victrola to MP3, 100 years of music, machines, and money, Da Capo Press, 2003.

- Gaisberg, Frederick W. (1977). Andrew Farkas (ed.). The Music Goes Round. New Haven: Ayer. ISBN 9780405096785.

- Gronow, Pekka, "The Record Industry: The Growth of a Mass Medium", Popular Music, Vol. 3, Producers and Markets (1983), pp. 53–75, Cambridge University Press.

- Gronow, Pekka, and Saunio, Ilpo, "An International History of the Recording Industry", [translated from the Finnish by Christopher Moseley], London; New York : Cassell, 1998. ISBN 0-304-70173-4

- Lipman, Samuel,"The House of Music: Art in an Era of Institutions", 1984. See the chapter on "Getting on Record", pp. 62–75, about the early record industry and Fred Gaisberg and Walter Legge and FFRR (Full Frequency Range Recording).

- Millard, Andre J., "America on record : a history of recorded sound", Cambridge; New York : Cambridge University Press, 1995. ISBN 0-521-47544-9

- Millard, Andre J., " From Edison to the iPod", UAB Reporter, 2005, University of Alabama at Birmingham.

- Milner, Greg, "Perfecting Sound Forever: An Aural History of Recorded Music", Faber & Faber; 1 edition (June 9, 2009) ISBN 978-0-571-21165-4. Cf. p. 14 on H. Stith Bennett and "recording consciousness".

- Read, Oliver, and Walter L. Welch, From Tin Foil to Stereo: Evolution of the Phonograph, Second ed., Indianapolis, Ind.: H.W. Same & Co., 1976. N.B.: This is an historical account of the development of sound recording technology. ISBN 0-672-21205-6 pbk.

- Read, Oliver, The Recording and Reproduction of Sound, Indianapolis, Ind.: H.W. Sams & Co., 1952. N.B.: This is a pioneering engineering account of sound recording technology.

- "Recording Technology History: notes revised July 6, 2005, by Steven Schoenherr" at the Wayback Machine (archived March 12, 2010), San Diego University

- St-Laurent, Gilles, "Notes on the Degradation of Sound Recordings", National Library [of Canada] News, vol. 13, no. 1 (Jan. 1991), p. 1, 3–4.

- McWilliams, Jerry. The Preservation and Restoration of Sound Recordings. Nashville, Tenn.: American Association for State and Local History, 1979. ISBN 0-910050-41-4

- Weir, Bob, et al. Century of Sound: 100 Years of Recorded Sound, 1877-1977. Executive writer, Bob Weir; project staff writers, Brian Gorman, Jim Simons, Marty Melhuish. [Toronto?]: Produced by Studio 123, cop. 1977. N.B.: Published on the occasion of an exhibition commemorating the centennial of recorded sound, held at the fairground of the annual Canadian National Exhibition, Toronto, Ont., as one of the C.N.E.'s 1977 events. Without ISBN

External links

[edit]- History of Sound Recording – Maintained by the British Library

- Noise in the Groove – A podcast about the history of the phonograph, gramophone, and sound recording/reproduction.

- Recorded Music at A History of Central Florida Podcast

- Millard, Andre, "Edison's Tone Tests and the Ideal of Perfect Reproduction", Lost and Found Sound, interview on National Public Radio.

- Will Straw; Helmut Kallmann; Edward B. Moogk. "Recorded sound production". Encyclopedia of Music in Canada. Retrieved August 19, 2019.

{{cite encyclopedia}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)