Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Auto rickshaw

View on Wikipedia

An auto rickshaw is a motorized version of the pulled rickshaw or cycle rickshaw.[1] It is usually a three-wheeled vehicle, powered by an engine.[2] They use a variety of fuels, with the most common being petrol, Compressed Natural Gas, Liquefied Petroleum Gas, and electricity. They are known by various other names across countries.

The auto rickshaw is a common form of transport around the world, both as a vehicle for hire and for private use. They are especially common in countries with tropical or subtropical climate since they are usually not fully enclosed, and in many developing countries because they are relatively inexpensive to own and operate.

There are different auto rickshaw designs. The most common type used for passenger transport is characterized by a sheet-metal body resting on three wheels with a canvas roof and drop-down side curtains. The driver is seated in a small cabin at the front and operates handlebar controls with a space for carrying up to three passengers in the back.[3] The cargo versions might have an open space at the rear. A simpler version might have an expanded sidecar mounted on a three wheeled motorcycle.

As of 2023[update], India is the largest market for electric auto rickshaws, bypassing China.[4] As of 2024[update], Bajaj Auto of India is the world's largest auto rickshaw manufacturer.[5]

Origin

[edit]

In the 1930s Japan, which was the most industrialized country in Asia at the time, encouraged the development of motorized vehicles including less expensive three-wheeled vehicles based on motorcycles. The Mazda-Go, a 3-wheel open "truck" released in 1931,[6] is often considered the first of what became auto rickshaws. Later that decade the Japanese Ministry of Posts and Telecommunications of Japan distributed about 20,000 used three-wheelers to Southeast Asia as part of efforts to expand its influence in the region.[7][8][9][10] They became popular in some areas, especially Thailand, which developed local manufacturing and design after the Japanese government abolished the three-wheeler license in Japan in 1965.[11]

Production in Southeast Asia started from the knockdown production of the Daihatsu Midget, which was introduced in 1959.[12] An exception is the indigenously modified Philippine tricycle, which originates from the Rikuo Type 97 motorcycle with a sidecar, introduced to the islands in 1941 by the Imperial Japanese Army during World War II.[13]

In Europe, Corradino D'Ascanio, aircraft designer at Piaggio and inventor of the Vespa, came up with the idea of building a light three-wheeled commercial vehicle to power Italy's post-war economic reconstruction. The Piaggio Ape followed suit in 1947. Also Innocenti another leading Scooter manufacturer came up with their Lambretta line of three wheelers in cargo version, later adopted as passenger version by its Indian colloborator Automobile Products of India.

Regional variations

[edit]Africa and the Middle East

[edit]Algeria

[edit]This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (April 2025) |

Egypt

[edit]Locally named the "tuktuk", the rickshaw is used as a means of transportation in most parts of Egypt. It is generally rare to find in some affluent and newer parts of cities such as New Cairo and Heliopolis; and on highways due to police control and enforcement.

Gaza

[edit]Together with the recent boom of recreational facilities in Gaza for the local residents, donkey carts have all but been displaced by tuk-tuks in 2010. Due to the ban by Egypt and Israel on the import of most motorised vehicles, the tuk-tuks have had to be smuggled in parts through the tunnel network connecting Gaza with Egypt.[14]

Iraq

[edit]Due to extreme congestion in Baghdad and other Iraqi cities combined with the insensible cost of vehicles in relation to frequent violence, rickshaws have been imported from India in large numbers to provide taxi service and other purposes, in stark contrast to previous attitudes of the pre-U.S. 2003 invasion eras with rickshaws being disdained and sedans being held in high regard as a status symbol. Rickshaws have been noted for being instrumental in political protest revolts.[15][16][17][18][19]

Madagascar

[edit]In Madagascar, man-powered rickshaws are a common form of transportation in a number of cities, especially Antsirabe. They are known as "posy" from pousse-pousse, meaning push-push. Cycle rickshaws took off since 2006 in a number of flat cities like Toamasina and replaced the major part of the posy, and are now threatened by the auto rickshaws, introduced in 2009. Provincial capitals like Toamasina, Mahajanga, Toliara, and Antsiranana are taking to them rapidly.[citation needed] They are known as "bajaji" in the north and "tuk-tuk" or "tik-tik" in the east, and are now licensed to operate as taxis.[citation needed] They are not yet allowed an operating licence in the congested, and more polluted national capital, Antananarivo.[citation needed][20][21][22]

Morocco

[edit]In Morocco, there are Auto-rickshaws in Rabat, Casablanca and Marrakesh.

Nigeria

[edit]

The auto rickshaw is used to provide transportation in cities all over Nigeria. Popularity and use varies across the country. In Lagos, for example, the "keke" (Hausa for bicycle) is regulated and transportation around the state's highways is prohibited while in Kano it's popularly known as "Adaidaita Sahu".[23]

South Africa

[edit]

Tuk-tuks, introduced in Durban[24] in the late 1980s, have enjoyed growing popularity in recent years, particularly in Gauteng.[25] In Cape Town they are used to deliver groceries and, more recently, transport tourists.[26][27]

Sudan

[edit]Rickshaws, known as "Raksha" in Sudan, are the most common means of transportation, followed by the bus, in the capital Khartoum.

Tanzania

[edit]Locally known as "bajaji", they are a common mode of transportation in Dar es Salaam, and many other cities and villages.[28]

Tunisia

[edit]This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (April 2025) |

Uganda

[edit]A local delivery company called as Sokowatch in 2020 began a pilot project using electric tuk-tuks, to cut pollution.[29]

United Arab Emirates

[edit]Zimbabwe

[edit]

Hende Moto EV & Taxi company was founded in 2019 by Devine Mafa, an American-Zimbabwean businessman. Hende Moto taxis were first introduced in Zimbabwe as the first vehicle manufactured by Zimbabwean three-wheeler manufacturing company Hende Moto Pvt Ltd. The first Hende Moto Taxi was introduced in Kwekwe in August 2019, and thereafter in Victoria Falls City and then Harare in 2019. Hende Moto is also the manufacturer of the first Zimbabwean-made electric passenger three-wheeled vehicle. It operates on a lithium-ion battery that has a range of 70 miles on a 6-hour charge.

South Asia

[edit]Afghanistan

[edit]

Auto rickshaws are very common in the eastern Afghan city of Jalalabad, where they are popularly decorated in art and colors.[30] They are also popular in the northern city of Kunduz.[31]

Bangladesh

[edit]

Auto rickshaws (locally called "baby taxis", "Bangla Teslas" for electric ones[32] or "CNGs" for those running on compressed natural gas) are one of the more popular modes of transport in Bangladesh mainly due to their size and speed. They are best suited to narrow, crowded streets, and are thus the principal means of covering longer distances within urban areas.[33]

Two-stroke engines had been identified as one of the leading sources of air pollution in Dhaka. Thus, since January 2003, traditional auto rickshaws were banned from the capital; only the new natural gas-powered models (CNG) were permitted to operate within the city limits. All CNGs are painted green to signify that the vehicles are eco-friendly and that each one has a meter built-in.[34]

As of 2025, auto rickshaws in Bangladesh are predominantly electric. There were around 4 million unregistered electric auto rickshaws circulating in Bangladesh by 2025, up from 200,000 in 2016. They constitute "perhaps the world’s biggest informal EV fleet."[32]

India

[edit]

Most cities offer auto rickshaw service, Although cycle rickshaws and hand-pulled rickshaws are also available but rarely in certain remote areas, as all other cities began using auto rickshaws. [35]: 15, 57, 156 Many state governments have launched an initiative of women-friendly rickshaw service called the Pink Rickshaws driven by women.[36] The drivers are known as the Rickshaw-wallah, auto-wallah, tuktuk-wallah or auto-kaaran in places like Tamil Nadu/Kerala . Auto-rickshaws are also known as tempos in some parts of India.[37]

Auto rickshaws are used in cities and towns for short distances; they are less suited to long distances because they are slow and the carriages are open to air pollution.[35]: 57, 58, 110 Auto rickshaws (often called "autos") provide cheap and efficient transportation. Modern auto rickshaws run on electricity as government pushes for e-mobility through its FAME-II scheme, compressed natural gas (CNG) and liquified petroleum gas (LPG) due to government regulations and are environmentally friendly compared to full-sized cars.[citation needed][nb 1]

To augment speedy movement of traffic, auto rickshaws are not allowed in the southern part of Mumbai.[38]

India is the location of the annual Rickshaw Run.

There are two types of auto rickshaws in India. In older versions the engines were below the driver's seat, while in newer versions engines are in the rear. They normally run on petrol, CNG, or diesel. The seating capacity of a normal rickshaw is four, including the driver's seat. Six-seater rickshaws exist in different parts of the country, but the model was officially banned in the city of Pune on 10 January 2003 by the Regional Transport Authority (RTA).[39]

Apart from this, modern electric auto rickshaws, which run on electric motors and have high torque and loading capacity with better speed, are also gaining popularity in India. Many auto drivers moved to electric three-wheelers as the prices of CNG or Diesel is very high and that type of auto rickshaw is much costlier compared to the electric auto rickshaw. The Government is also taking actions to convert current CNG and diesel rickshaws to electric rickshaws.[40]

CNG autos in many cities (e.g. Delhi, Agra) are distinguishable from the earlier petrol-powered autos by a green and yellow livery, as opposed to the earlier black and yellow appearance. In other cities (such as Mumbai) the only distinguishing feature is the 'CNG' print found on the back or side of the auto. Some local governments are considering four-stroke engines instead of two-stroke versions.[citation needed]

Notable auto rickshaw manufacturers in India include Bajaj Auto, Mahindra & Mahindra, Piaggio Ape, Atul Auto, Kerala Automobiles Limited, TVS Motors and Force Motors.

In Delhi there also used to be a variant powered by a Harley-Davidson engine called the phat-phati, because of the sound it made. The story goes that shortly after Independence a stock of Harley-Davidson motorbikes were found that had been used by British troops during World War II and left behind in a military storage house in Delhi. Drivers purchased these bikes, added on a gear box (probably from a Willys jeep), welded on a passenger compartment that was good for four to six passengers, and put the unconventional vehicles onto the roads. A 1998 ruling of the Supreme Court against the use of polluting vehicles finally signed the death warrant of Delhi's phat-phatis.[41][42]

As of 2022[update] India has about 2.4 million battery-powered, three-wheeled rickshaws on its roads. Some 11,000 new ones hit the streets each month, creating a US$3.1 billion market. Manufacturers include Mahindra & Mahindra Ltd. and Kinetic Engineering. A prerequisite for the adoption to electric vehicles is the availability of charging stations; as of early 2024, India had 12,146 public EV charging stations operational across the country.[43]

-

CNG green auto rickshaw in New Delhi

-

A Bajaj Auto rickshaw in Bangalore

-

A Piaggio Ape auto rickshaw in Kerala

-

A TVS auto rickshaw in Chennai

-

An electric rickshaw at a battery swapping point

-

Three wheeler cargo auto-rickshaw used in India

-

Indian auto-rickshaw adapted with trailer

-

Erisha electric passenger and cargo Auto rickshaws in India

Generally rickshaw fares are controlled by the government,[44] however auto (and taxi) driver unions frequently go on strike demanding fare hikes. They have also gone on strike multiple times in Delhi to protest against the government and High Court's 2012 order to install GPS systems, and even though GPS installation in public transport was made mandatory in 2015, as of 2017 compliance remains very low.[45][46][47]

The 200 cc variant of the Bajaj Auto auto rickshaw was used in the 2022 Rickshaw Run to set the record for the world's highest auto rickshaw, over the Umling La Pass, at 5,798 meters (19,022 feet)[48][49]

Nepal

[edit]Auto rickshaws were a popular mode of transport in Nepal during the 1980s and 1990s, until the government banned the movement of 600 such vehicles in the early 2000s.[50] The earliest auto rickshaws running in Kathmandu were manufactured by Bajaj Auto.[citation needed]

Nepal has been a popular destination for the Rickshaw Run. The 2009 Fall Run took place in Goa, India and ended in Pokhara, Nepal.[51]

Pakistan

[edit]Auto rickshaws are a popular mode of transport in Pakistani towns[52] and are mainly used for travelling short distances within cities. One of the major manufacturers of auto rickshaws is Piaggio. The government is taking measures to convert all gasoline powered auto rickshaws to cleaner CNG rickshaws by 2015 in all the major cities of Pakistan by issuing easy loans through commercial banks. Environment Canada is implementing pilot projects in Lahore, Karachi, and Quetta with engine technology developed in Mississauga, Ontario, Canada that uses CNG instead of gasoline in the two-stroke engines, in an effort to combat environmental pollution and noise levels.[citation needed]

In many cities in Pakistan, there are also motorcycle rickshaws, usually called "chand gari" (moon car) or "chingchi", after the Chinese company Jinan Qingqi Motorcycle Co. Ltd who first introduced these to the market.[citation needed]

There are many rickshaw manufacturers in Pakistan. Lahore is the hub of CNG auto rickshaw manufacturing. Manufacturers include: New Asia automobile Pvt, Ltd; AECO Export Company; STAHLCO Motors; Global Sources; Parhiyar Automobiles; Global Ledsys Technologies; Siwa Industries; Prime Punjab Automobiles; Murshid Farm Industries; Sazgar Automobiles; NTN Enterprises; and Imperial Engineering Company.

Sri Lanka

[edit]

Auto rickshaws, commonly known as three-wheelers, tuk-tuks (Sinhala: ටුක් ටුක්, pronounced [ṭuk ṭuk]), autos, or trishaws can be found on all roads in Sri Lanka transporting people or freight. Sri Lankan three-wheelers are of the style of the light Phnom Penh-type. Most of the three-wheelers in Sri Lanka are a slightly modified Indian Bajaj model, imported from India though there are few manufactured locally and increasingly imports from other countries in the region and other brands of three-wheelers such as Piaggio Ape. Three-wheelers were introduced to Sri Lanka for the first time around 1979 by Richard Pieris & Company. As of mid-2018,[update] a new gasoline powered tuk-tuk typically costs around US$4,300, while a newly introduced Chinese electric model cost around US$5,900.[53] Since 2008, the Sri Lankan government has banned the import of all 2-stroke gasoline engines due to environmental concerns.[53] Ones imported to the island now are four-stroke engines. Most three-wheelers are available as hired vehicles, with few being used to haul goods or as private company or advertising vehicles. Bajaj enjoys a virtual monopoly in the island, with its agent being David Pieries Motor Co, Ltd.[54] A few three-wheelers in Sri Lanka have distance meters. In the capital city it is becoming more and more common. The vast majority of fares are negotiated between the passenger and driver. There are 1.2 million trishaws in Sri Lanka and most are on financial loans.

Southeast Asia

[edit]-

Tuktuks and palmyra palms on the Mekong bank in Thakhek, Laos

-

Tuk-tuk taxi sidecar in Laos

-

Tuk-tuk, Phnom Penh, Cambodia

Cambodia

[edit]In Cambodia, a passenger-carrying three-wheeled vehicle is known as រ៉ឺម៉ក rœmâk from the French remorque. It is a widely used form of transportation in the capital of Phnom Penh and for visitors touring the Angkor temples in Siem Reap. Some have four wheels and is composed of a motorcycle (which leans) and trailer (which does not). Cambodian cities have a much lower volume of automobile traffic than Thai cities, and tuk-tuks are still the most common form of urban transport. There are more than 6,000 tuk-tuks in Phnom Penh, according to the Independent Democracy of Informal Economy Association (IDEA), a union that represents tuk-tuk drivers among other members.[55]

Indonesia

[edit]In Indonesia, auto rickshaws are popular in Jakarta as Bajay, Java, Medan and Gorontalo as Bentor, and some parts of Sulawesi and other places in the country. In Jakarta, the auto rickshaws are called Bajay or Bajaj and they are the same to as the ones in India but are colored blue (for the ones which use compressed natural gas) and orange (for normal gasoline fuel).[56] The blue ones are imported from India with the brand of Bajaj and TVS and the orange ones are the old design from 1977. The orange ones uses two-stroke engines as their prime mover, while the blue ones use four stroke engines. The orange bajaj has been banned since 2017 due to emission regulations.[57][56] The Bajaj is one of the most popular modes of transportation in the city. Outside of Jakarta, the bentor-style auto rickshaw is ubiquitous, with the passenger cabin mounted as a sidecar (like in Medan) or in-front (like the ones in some parts of Sulawesi) to a motorcycle.

-

Bentor in North Sumatra

-

Bentor in Tana Toraja, South Sulawesi

-

4-stroke Bajaj in Jakarta

-

Former 2-stroke orange Bajaj in Jakarta (discontinued in 2015)

Philippines

[edit]In the Philippines, a similar mode of public transport is the "tricycle" (Filipino: traysikel; Cebuano: traysikol).[58] Unlike auto rickshaws, however, it has a motorcycle with a sidecar configuration and a different origin. The exact date of its appearance in the Philippines is unknown, but it started appearing after World War 2, roughly at the same time as the appearance of the jeepney. It is most likely derived from the Rikuo Type 97 military motorcycle used by the Imperial Japanese Army in the Philippines starting at 1941. The motorcycle was essentially a licensed copy of a Harley-Davidson with a sidecar.[13] However, there is also another hypothesis which places the origin of the tricycle to the similarly built "trisikad", a human-powered cycle rickshaw built in the same configuration as the tricycle. However, the provenance of the trisikad is also unknown. Prior to the tricycles and trisikad, the most common means of mass public transport in the Philippines is a carriage pulled by horses or carabaos known as the kalesa (calesa or carromata in Philippine Spanish).[59] The pulled rickshaw never gained acceptance in the Philippines. Americans tried to introduce it in the early 20th century, but it was strongly opposed by local Filipinos who viewed it as an undignified mode of transport that turned humans into "beasts".[60]

The design and configuration of tricycles vary widely from place to place, but tends towards rough standardization within each municipality. The usual design is a passenger or cargo sidecar fitted to a motorbike, usually on the right of the motorbike. It is rare to find one with a left sidecar. A larger variant of the tricycle with the motorcycle in the center enclosed by a passenger cab with two side benches is known as a "motorela". It is found on the islands of Mindanao, Camiguin, and Bohol.[61] Another notable variant is the tricycles of the Batanes Islands which have cabs made from wood and roofed with thatched cogon grass.[62] In Pagadian City, tricycles are also uniquely built with the passenger cab slanting upwards, due to the city's streets that run along steep hills.[63]

Tricycles can carry three passengers or more in the sidecar, one or two pillion passengers behind the driver, and even a few on the roof of the sidecar. Tricycles are one of the main contributors to air pollution in the Philippines,[64][65] which account for 45% of all volatile organic compound emissions[66] since majority of them employ two-stroke engines. However, some local governments are working towards phasing out two-stroke tricycles for ones with cleaner four-stroke engines.[64][67]

Tuk-Tuks have now been accepted as Three-Wheeled Vehicles by the Land Transportation Office (Philippines) as distinct from tricycles and are now seen in Philippine streets. Electric versions are now seen especially in the city of Manila where they are called e-trikes,[68] while called as Bukyo in Batangas and Cavite.[69] Combustion engine tuktuks are locally distributed by TVS Motors and Bajaj Auto through dealerships[70]

-

Motorized tricycle, Dumaguete

-

7-passenger tricycle with large sidecar, province of Aklan

-

Tricycle stand, Banaue Municipal Town

Thailand

[edit]The auto rickshaw, called tuk-tuk (Thai: ตุ๊ก ๆ, pronounced [túk túk]) in Thailand, is a widely used form of urban transport in Bangkok and other Thai cities. The name is onomatopoeic, mimicking the sound of a small (often two-cycle) engine. It is particularly popular where traffic congestion is a major problem, such as in Bangkok and Nakhon Ratchasima. In Bangkok in the 1960s, these were called samlaws, and they are still popularly called that today.

Bangkok and other cities in Thailand have many tuk-tuks which are a more open variation on the Indian auto rickshaw. About 20,000 tuk-tuks were registered as taxis in Thailand in 2017.[71] Bangkok alone is reported to have 9,000 tuk-tuks.[72]

Tuk-tuk hua kob (ตุ๊ก ๆ หัวกบ, pronounced [túk túk hua̯ kop̚], lit. 'frog-headed tuk tuk') is a unique tuk tuk with a cab looking like a frog's head. Only Phra Nakhon Si Ayutthaya and Trang have vehicles like this.[73][74]

in 2018, MuvMi, an electric tuk-tuk ride hailing service launched in Bangkok.[75]

-

Tuk-tuk in Bangkok

-

Police tuk-tuk, Chiang Mai

-

Electric tuk-tuk in Chiang Mai

-

Tuk-tuk hua kob, Phra Nakhon Si Ayutthaya

East Asia

[edit]China

[edit]

Various types of auto rickshaw are used around China, where they are called sān lún chē (三轮车) and sometimes sān bèng zǐ (三蹦子), meaning three wheeler or tricycle. They may be used to transport cargo or passengers in the more rural areas. However, in many urban areas the auto rickshaws for passengers are often operated illegally as they are considered unsafe and an eyesore.[76][77] They are permitted in some towns and cities, however. The Southeast Asian word tuk tuk is transliterated as dū dū chē (嘟嘟车, or beep beep car) in Chinese.[78]

Europe

[edit]France

[edit]A number of tuk-tuks (250 in 2013 according to the Paris Prefecture) are used as an alternative tourist transport system in Paris, some of them being pedal-operated with electric motor assist. They are not yet fully licensed to operate and await customers on the streets. Vélotaxis were common during the Occupation years in Paris due to fuel restrictions.[79]

Italy

[edit]

Auto rickshaws have been commonly used in Italy since the late 1940s, providing a low-cost means of transportation in the post–World War II years when the country was short of economic resources. The Piaggio Ape (Tukxi), designed by Vespa creator Corradino D'Ascanio and first manufactured in 1948 by the Italian company Piaggio, though primarily designed for carrying freight has also been widely used as an auto rickshaw. It is still extremely popular throughout the country, being particularly useful in the narrow streets found in the center of many little towns in central and southern Italy. Though it no longer has a key role in transportation, Piaggio Ape is still used as a minitaxi in some areas such as the islands of Ischia and Stromboli (on Stromboli no cars are allowed). It has recently been re-launched as a trendy-ecological means of transportation, or, relying on the role the Ape played in the history of Italian design, as a promotional tool.

Portugal

[edit]

Tuk Tuks are used in the main touristic cities and regions of the country, specially in Lisbon and the sunny region of Algarve, as a novel form of transport for visitors during the tourist season.

Spain

[edit]Tuk Tuks have become a popular mode of transport in Spain’s main tourist destinations, particularly in Barcelona and the coastal areas of Valencia,[80] as well as Mallorca[81] and Málaga[82]

United Kingdom

[edit]In 2006 a British travel writer – Antonia Bolingbroke-Kent – and her friend Jo Huxster travelled 12,561 miles (20,215 km) with an auto rickshaw from Bangkok to Brighton. With this 98 days' trip they set a Guinness World Record for the longest journey ever with an auto rickshaw.[citation needed] In October 2022, Gwent police spent £40,000 on four tuk tuk vehicles in order to help fight crime.[83]

Montenegro

[edit]Tuk Tuk Montenegro has implemented tours with electric tuk-tuks in Kotor, Montenegro in 2018.[84]

North America

[edit]

El Salvador

[edit]The mototaxi or moto is the El Salvadoran version of the auto rickshaw. These are most commonly made from the front end and engine of a motorcycle attached to a two-wheeled passenger area in back. Commercially produced models, such as the Indian Bajaj brand, are also employed.[citation needed]

Guatemala

[edit]In Guatemala tuk-tuks operate, both as taxis and private vehicles, in Guatemala City, around the island town of Flores, Peten, in the mountain city of Antigua Guatemala, and in many small towns in the mountains. From 2005 to present the tuk-tuks have been prevalent in Lago de Atitlán towns such as Panajachel and Santiago Atitlán. While tuk-tuks continue to serve as a prevalent form of transportation in Antigua and Lake Atitlan their use throughout the country as a whole has declined.

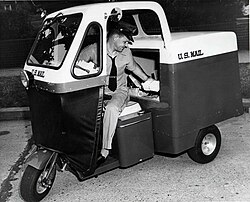

United States

[edit]In the 1950s and 1960s, the United States Post Office (replaced in 1971 by the United States Postal Service) used the WestCoaster Mailster, a close relative of the tuk-tuk.[85] Similar vehicles remain in limited use for parking enforcement, mall security, and other niche applications. After a short time on the market (Mid-2000s to 2008) in the United States,[86] the vehicles failed to gain popularity in the United States, and as a result, are no longer available. The Manufacturer Bajaj cited the manual transmissions aboard the three-wheelers as the reason for poor sales. As a result of modifications that made the machines EPA and DOT compliant, the vehicles that were sold are still street-legal.[87]

Auto rickshaws are rarely seen in the United States, However there are companies that operate them as taxis, affordable transportation services, or rentals, usually in urban areas like Tuk Tuk Chicago in Chicago, Capital Tuk-Tuk in Sacramento, eTuk Ride Denver in Denver, the Boston rickshaw company in Boston and several more.[88][89][90][91][92][93][94][95][96][97][98][99]

The New York Police Department (NYPD) operates auto rickshaws that they call “three-wheel patrol scooters”. The patrol scooters are used for parking and traffic enforcement on city streets and to patrol places that most cars can't – like the narrow paths in Central Park. The NYPD patrol scooters started being replaced in 2016 with Smart Fortwos. The NYPD believes that the Smart Fourtwos are safer, more comfortable, and more affordable, than the three-wheel patrol scooters due to the Smart Fourtwos coming with features that the patrol scooters lack like air conditioning, and airbags, while also costing about $6,000 less. The Smart Fortwos can also be driven on highways if needed. The Smart Fortwos are also said to be more “approachable” and “friendlier looking” which helps with public relations.[100]

Cuba

[edit]In Cuba, the autorickshaws are small and look like a coconut, hence the name Cocotaxi.

Mexico

[edit]Some auto rickshaws have been and are still used in Mexico, Such as in Rickshaws in Mexico City.[101][102][103]

South America

[edit]Peru

[edit]In Peru, a version of this vehicle is called a motocar[104] or mototaxi.[105]

Bolivia

[edit]Auto Rickshaws are seen in Bolivia.[106][107]

Brazil

[edit]Uber allows auto rickshaws to be used by drivers.[108][109][110]

Colombia

[edit]Tuk tuks or moto-taxis are used in some towns and cities in Colombia such as Jardín in Antioquia. [111]

Australia and Oceania

[edit]Australia

[edit]Ikea did a trial run using Electric Auto Rickshaws in Sydney, Australia to deliver packages to customers from May to August 2023.[112]

A company called Just Tuk'n Around using both pedal powered rickshaws and electric auto rickshaws carries tourists around in Airlie Beach.[113]

New Zealand

[edit]Mount Cook Alpine Salmon uses Auto rickshaws on its farms to move equipment and people around.[114]

A company using auto rickshaws called Tuk Tuk Taxi operates in Wānaka in the South Island.[115]

A company using auto rickshaws called Tuk Tuk NZ used to operate in Wellington.[116][117]

A company using auto rickshaws called Kiwi Tuk Tuk used to operate in Auckland.[118][116]

Fuel efficiency and pollution

[edit]In July 1998, the Supreme Court of India ordered the government of Delhi to implement CNG or LPG (Autogas) fuel for all autos and for the entire bus fleet in and around the city. Delhi's air quality has improved with the switch to CNG. Initially, auto rickshaw drivers in Delhi had to wait in long queues for CNG refueling, but the situation improved following an increase in the number of CNG stations. Gradually, many state governments passed similar laws, thus shifting to CNG or LPG vehicles in most large cities to improve air quality and reduce pollution. Certain local governments are pushing for four-stroke engines instead of two-stroke ones. Typical mileage for an Indian-made auto rickshaw is around 35 kilometres per litre (99 mpg‑imp; 82 mpg‑US) of petrol. Pakistan has passed a similar law prohibiting auto rickshaws in certain areas. CNG auto rickshaws have started to appear in huge numbers in many Pakistani cities.[citation needed]

In January 2007 the Sri Lankan government also banned two-stroke trishaws to reduce air pollution. In the Philippines[119] there are projects to convert carbureted two-stroke engines to direct-injected via Envirofit technology. Research has shown LPG or CNG gas direct-injection can be retrofitted to existing engines, in similar fashion to the Envirofit system.[120] In Vigan City majority of tricycles-for-hire as of 2008 are powered by motorcycles with four-stroke engines, as tricycles with two-stroke motorcycles are prevented from receiving operating permits. Direct injection is standard equipment on new machines in India.[121][122]

In March 2009 an international consortium coordinated by the International Centre for Hydrogen Energy Technologies initiated a two-year public-private partnership of local and international stakeholders aiming at operating a fleet of 15 hydrogen-fueled three-wheeled vehicles in New Delhi's Pragati Maidan complex.[123] As of January 2011, the project was nearing completion.[citation needed]

Hydrogen internal combustion (HICV) use in three-wheelers has only recently being started to be looked into, mainly by developing countries, to decrease local pollution at an affordable cost.[124][125] At some point, Bajaj Auto made a HICV auto rickshaw together with the company "Energy Conversion Devices".[126] They made a report on it called "Clean Hydrogen Technology for 3-Wheel Transportation in India" and it stated that the performance was comparable with CNG autos. In 2012, Mahindra & Mahindra showcased their first HICV auto rickshaw, called the Mahindra HyAlfa.[126] The development of the hydrogen-powered rickshaw happened with support from the International Centre for Hydrogen Energy Technologies.

World records

[edit]On 16 September 2022, at 11:04 a.m. (Indian Standard Time), a Canadian team (Greg Harris and Priya Singh) and a Swiss team (Michele Daryanani and Nevena Lazarevic) set the world record for the highest altitude at which an auto rickshaw has ever been driven. The world record was officially recognized and certified by Guinness World Records on October 10, 2024.[127] The two teams set the record by driving to the summit of Umling La Pass at an altitude of 5,798 meters (19,022 feet).[128]

The two teams were participating in the Rickshaw Run (Himalayan Edition), an event promoted by The Adventurists, where teams drive auto rickshaws from the Thar desert town of Jaisalmer in Rajasthan to the Himalayan town of Leh in Ladakh. Rickshaw Run teams are given the start and finish lines, but are otherwise unsupported and left to their own navigational choices in completing the approximately 2,300 km journey.

The road at Umling La Pass was constructed by India's Border Roads Organization and completed in 2017. Guinness World Records certified the road as the highest motorable road in the world.[129]

See also

[edit]- Electric rickshaw

- Fuel gas-powered scooter

- Formic acid vehicle: a type of hydrogen-based vehicle

- Jeepney

- Rickshaw (disambiguation)

Explanatory notes

[edit]- ^ Typical fuel economy for an Indian-made auto rickshaw is around 35 kilometres per litre (99 mpg‑imp; 82 mpg‑US) of petrol.[citation needed]

References

[edit]- ^ "Auto rickshaw". Merriam Webster. Retrieved 1 June 2025.

- ^ "Auto rickshaw". Collins dictionary. Retrieved 1 June 2025.

- ^ "Auto rickshaw". Cambridge Dictionary. Retrieved 1 June 2025.

- ^ "India beats China again to be world's largest electric 3W market". Autocar Professional. Retrieved 1 June 2025.

- ^ "Best Auto Rickshaw Manufacturers in India". Cmv360. Retrieved 1 June 2025.

- ^ "Great Cars of Mazda: Mazda-Go 3-wheeled Trucks (1931〜)". Mazda Motor Corporation. Archived from the original on 2019-02-09.

- ^ ミゼット物語 木村信之 著 高原書店(Nobuyuki Kimura "Story of Midget", Published on 10 November 1998)

- ^ Daihatsu Motor Co., Ltd. public relations section

- ^ NPOみらいネットワーク寄附講座、ホテル観光学科の学生に日タイ関係をピーアール 日本での就職機会に関心. Bangkok Shuho (in Japanese). 2007-11-19. Archived from the original on 2009-04-30.

- ^ /index.php?option=com_content&view=article&id=321:2009-11-30-05-34-59&catid=54:2009-09-09-07-52-31&Itemid=232 Royal Thai Embassy Tokyo, Japan 日本生まれのタイのトゥクトゥク (Tuk-Tuk of Thailand was born in Japan.)

- ^ "Tuk-Tuk, Thailand's most notorious mode of transport - deSIAM". www.desiam.com. Archived from the original on 2020-09-23. Retrieved 2020-03-26.

- ^ "【ダイハツ ミゼット DKA / DSA型】 幌付3輪スクーター型トラック 旧式商用車図鑑". route0030.blog.fc2.com.

- ^ a b "The History of the Philippines Tricycle". Tuk Tuk 3 Wheelers. 22 November 2018. Retrieved 25 March 2020.

- ^ "Tuk Tuks replace mules on Gaza streets". Maan News Agency. 12 September 2010. Retrieved 2011-03-22.

- ^ "Mundane autos in India, hero tuk-tuks in Iraq". Deccan Herald. 25 November 2019. Retrieved 31 January 2024.

- ^ Shukla, Srijan (26 November 2019). "How Indian manufactured auto-rickshaws became a symbol of Iraqi protests". ThePrint. Retrieved 31 January 2024.

- ^ Alhas, Ali Murat. "In congested Baghdad, Iraqis turn to 3-wheel 'tuk-tuks'". Anadolu Agency.

- ^ Vitalone, Vivi (14 November 2024). "How tuk-tuk drivers became the unlikely heroes of Iraq's popular revolt". NBC News. Retrieved 31 January 2024.

- ^ Salim, Mustafa; Berger, Miriam (1 November 2024). "The humble three-wheeled tuk-tuk has become the symbol of Iraq's uprising". The Washington Post. Retrieved 31 January 2024.

- ^ Jay Heale; Zawiah Abdul Latif (2008). Madagascar, Volume 15 of Cultures of the World Cultures of the World – Group 15 (2 ed.). Marshall Cavendish. pp. 75–76. ISBN 978-0761430360.

- ^ Madagascar Travel Guide (7 ed.). Lonely Planet. 2012. ISBN 978-1743213018. Retrieved 2013-04-13.

- ^ "'Bajaj' à Mahajanga : Entre 70 et 100 clients par jour". Midi Madagasikara (in French). 2014-05-30.

- ^ Odunsi, Wale (16 November 2017). "Lagos bans okada, keke from 520 roads, areas [Full list]". Daily Post.

- ^ "Durban offers beaches and cultural diversity". Zululand Tourism. Archived from the original on 22 May 2022. Retrieved 22 September 2015.

Tuk Tuks: Mororised, covered tricycles which carry up to six passengers. Ideal for short 'hops' between the beachfront and city centre.

- ^ Steyn, Lisa (18 January 2013). "Cheap-cheap tuk-tuk taxis take over Jozi". Retrieved 22 September 2015.

Tuk-tuks, also known as auto rickshaws, are becoming an increasingly common sight on South Africa's roads because people are trying to travel short distances at lower costs than driving and at less risk than walking.

- ^ Ryan, Tamlyn (September 2016). "Tuk-tuks are coming to Cape Town". Inside Guide. Archived from the original on 2017-08-14. Retrieved 2017-03-18.

- ^ Govender, Suthentira (2017-01-25). "Buddibox grocery delivery programme set to create 10,000 young entrepreneurs in Gauteng". TimesLIVE.

- ^ Kalagho, Kenan (13 February 2012). "Tanzania: Bajaji, Dar es Salaam's Indispensable Taxi". AllAfrica. Retrieved 22 September 2015.

Until the year 2010 Dar es Salaam had no room for the Indian Bajaji and or a tricycle to be used as a means of transporting passengers. Today it is a common feature around Dar es Salaam.

- ^ Kuhudzai, Remeredzai Joseph (4 December 2020). "Gayam Motor Works & Sokowatch Launch East Africa's First Commercial Electric Tuk-Tuks". CleanTechnica.

- ^ McHugh, John D. "In Taliban country: inside the city of Jalalabad". The Irish Times.

- ^ "Auto-rickshaws clogging Kunduz arteries". www.pajhwok.com. 23 May 2012.

- ^ a b ""Bangla Teslas" give Musk a run for his money". The Economist. ISSN 0013-0613. Retrieved 2025-07-27.

- ^ Lane, Jo. "Asia's love affair with the rickshaw". asiancorrespondent.com. Archived from the original on 2015-07-13. Retrieved 2015-07-30.

- ^ "Police purge for Dhaka rickshaws". BBC News. 20 December 2002. Retrieved 2011-03-22.

- ^ a b Pippa de Bruyn; Keith Bain; David Allardice; Shonar Joshi (2010). Frommer's India (Fourth ed.). John Wiley and Sons. ISBN 978-0470645802.

- ^ "Pink Auto Rickshaw Project" (PDF). odishapolice.gov.in. 17 July 2019.

- ^ Mishra, Animesh (18 October 2024). "LMC drafts by-laws for tempos, e-rickshaws in Lucknow". Hindustan Times.

- ^ Pippa de Bruyn; Keith Bain; David Allardice; Shonar Joshi (2010). Frommer's India (Fourth ed.). John Wiley and Sons. p. 110. ISBN 978-0470645802.

- ^ "Six seater rickshaws banned in city". Times of India. 25 September 2003. Retrieved 2014-01-11.

- ^ "Patna: Transport department to ban all diesel-run buses, auto-rickshaws from April 1". India Today. 29 March 2022. Retrieved 2022-03-29.

- ^ "Remembering Delhi's phat-phatis | India News". The Times of India.

- ^ "Transportation through the ages in Shahjahanabad". olddelhiheritage.in. 18 September 2022. Archived from the original on 14 June 2016.

- ^ "12,146 public EV charging stations operational across the country". pib.gov.in. Retrieved 2024-04-16.

- ^ "Maharashtra Govt refuses to increase autorickshaw, taxi fares". newKerala.com. UNI. Archived from the original on 2013-05-18.

- ^ "Autos, taxis in Delhi to go on strike today demanding fare hike". India Today. 15 October 2012. Retrieved 2017-02-19.

- ^ "Delhi High Court Directs City Auto-Rickshaws To Install GPS". Medianama. 28 September 2012. Retrieved 2017-02-19.

- ^ "GPS installation in public transport becomes mandatory". Times of India. 2 June 2015. Retrieved 2017-02-19.

- ^ "Auto Rickshaws Set Highest Altitude Drive Record at 19,024 Feet on Umling La Pass". news18.com. 22 October 2022.

- ^ "Auto rickshaws drive on Umling La Pass, the highest motorable road, to set world record at 19,024 feet". MSN. 27 October 2022.

- ^ "Nepal Government decides to ban 3 wheeler auto rickshaws from Nepal's road". BBC. 28 July 1999. Retrieved 2011-12-06.

- ^ "Rickshaw Run on 3 Wheelers from Goa, India to Pokhara, Nepal". The National. 29 August 2009. Retrieved 2011-12-06.

- ^ Sebastian Abbot, Associated Press (8 February 2013). "Eye-Catching Rickshaws Promote Peace in Pakistan". ABC News. Retrieved 2013-04-13.

- ^ a b Ranasinghe, A.K. (3 September 2018). "Can He Convince Sri Lankan Tuk-Tuk Owners to Go Green?". OZY. Archived from the original on 3 September 2018. Retrieved 3 September 2018.

Tuk-tuks play a vital role in urban Sri Lanka's passenger transport system, providing what traffic experts call "last mile" service. Police and government workers rely on them too to navigate congested streets. In rural Sri Lanka, they are everything from taxi to ambulance.

- ^ "Bajaj ready with 4-stroke autos for SL". Indiacar.net. Archived from the original on 2009-06-27. Retrieved 2010-04-03.

- ^ Wilkins, Emily (19 February 2014). "New Futuristic Tuk-Tuks Arrive on the Streets of Phnom Penh". The Cambodia Daily. Archived from the original on 30 January 2015. Retrieved 30 January 2015.

- ^ a b "Bajaj Oranye Menunggu Giliran Dimusnahkan". Republika Online (in Indonesian). 7 January 2016. Retrieved 26 May 2018.

- ^ Damarjati, Danu (4 July 2017). "Dishub DKI: Bulan Ini, Bajaj Merah Harus Segera Jadi Biru" [Jakarta DOT: Red Bajajs must turn Blue this month] (in Indonesian). Retrieved 28 December 2022.

- ^ "Motorcycles and tricycles". Utrecht Faculty of Education. Archived from the original on 7 March 2009. Retrieved 2009-03-14.

- ^ "Filipino Icon: Tricycle and Pedicab". FFE Magazine. 29 December 2016. Retrieved 25 March 2020.

- ^ Pante, Michael D. (14 August 2014). "Rickshaws and Filipinos: Transnational Meanings of Technology and Labor in American-Occupied Manila". International Review of Social History. 59 (S22): 133–159. doi:10.1017/S0020859014000315.

- ^ "Tricycle, Motorela & Habal-Habal". Silent Gardens. Retrieved 25 March 2020.

- ^ Corsino, Nikka (24 October 2013). "A day on Sabtang Island in Batanes". GMA News Online. Retrieved 25 March 2020.

- ^ "WATCH: What makes Pagadian tricycles unique". Rappler. 23 January 2017. Retrieved 25 March 2020.

- ^ a b "Tricycles in the Philippines". cleanairasia.org. Archived from the original on 10 June 2018. Retrieved 7 January 2019.

- ^ Taruc, Paolo (25 March 2015). "Tricycles: As iconic as jeepneys and just as problematic". CNN Philippines. Archived from the original on 7 January 2019. Retrieved 7 January 2019.

- ^ Felongco, Gilbert P. (22 November 2015). "Philippines: Tricycles and motorcycles responsible for 45 per cent of harmful emissions". Gulf News. Retrieved 7 January 2019.

- ^ "Mandaluyong City 2-Stroke Replacement Project". cleanairasia.org. Archived from the original on 1 October 2020. Retrieved 7 January 2019.

- ^ "E.R.A.P. Manila electric tricycle project – Second batch of beneficiaries ready". www.bemac-philippines.com.

- ^ "Introducing the Bajaj RE: The Only Three-Wheeler You Will Ever Need". www.centaurmarketing.co. October 8, 2019.

- ^ "TVS King Deluxe Three Wheeler Vs Tricycle". Tuk Tuk 3-Wheelers. 20 October 2019.

- ^ Wattanasukchai, Sirinya (2 February 2017). "With our tuk tuks, let's copy the Dutch". Bangkok Post. Retrieved 2 February 2017.

- ^ "Thailand government says Bangkok has too many 'tuk-tuks'". Asian Correspondent. 2016-04-15. Archived from the original on 2016-04-26. Retrieved 2016-04-15.

- ^ "Frog-headed Tuk Tuk, Symbol of Aytthaya". Go Ayutthaya. Retrieved 2019-05-30.

- ^ Muangkaew, Methee (2013-02-19). "Tuk-tuk 'endangered species' in Trang". Bangkok Post. Retrieved 2019-05-30.

- ^ "MuvMi". ThailandMagazine.com. 2022-02-15. Retrieved 2022-06-18.

- ^ "明珠路上规模浩大的等客车队 危险逆行载客". 珠江晚报. 3 November 2009. Archived from the original on 2015-04-04.

- ^ "[天津]面对"三蹦子" 请您大声说"不"". auto sohu. Archived from the original on 2023-11-18. Retrieved 2015-03-29.

- ^ "東南亞的三輪車". Global Voices. 25 March 2012.

- ^ "A Paris, les tuk-tuks fleurissent... tout comme les PV". La Dépêche (in French). Toulouse. AFP. 2013-08-20.

- ^ "What to visit in Valencia: Tour in Tuk Tuk". 1 April 2025. Retrieved 1 April 2025.

- ^ "What to visit in Palma de Mallorca: tuk tuk tour". 1 April 2025. Retrieved 1 April 2025.

- ^ "DISCOVER MÁLAGA ABOARD OUR ELECTRIC TUK TUKS". 21 June 2025. Retrieved 21 June 2025.

- ^ "Gwent Police spend £40,000 on crime-fighting tuk-tuks". 27 October 2022. Retrieved 21 November 2022.

- ^ "A little bit about us". Tuk Tuk Montenegro. Retrieved 2022-01-12.

- ^ "National Postal Museum". 25 August 2009. Archived from the original on 25 August 2009.

- ^ "Tuk Tuk USA gets DOT and EPA approval". Autoblog. 15 April 2009.

- ^ "Bajaj 3-Wheeler is now off the U.S. market". Autoblog. 2 May 2008.

- ^ "Tuk Tuk Chicago – Do You Tuk Tuk?".

- ^ "Eco-Friendly Tour - Capital Tuk Tuk | Sacramento, CA". Capital Tuk Tuk.

- ^ "eTuk Locations - Electric Tuk Tuk City Tours & Brewery Crawls - eTuk Ride". eTuk.

- ^ "About Us". 4 February 2020.

- ^ "Rickshaw Rental Service for Events". Rags to Rickshaws.

- ^ tuks, Texas Tuk. "Texas Tuk tuks". Texas Tuk tuks.

- ^ "Things to do in Jacksonville | Jacksonville Tours & Transportation". Go Tuk'n.

- ^ "Home - RVATukTuk The fun, unique way to experience Richmond Book your adventure".

- ^ "Boston Rickshaw Company". Boston Rickshaw Company.

- ^ Weissmann, Emma (November 13, 2019). "Been There, Do This: eTuk Ride Portland in Oregon". TravelAge West.

- ^ "Home". Cycle Pub.

- ^ "Lucky Tuk Tuk Private Tours – Private Small Group Sightseeing Tours in San Francisco".

- ^ "NYPD's "kissable and huggable" Smart cars receive flood of attention". www.cbsnews.com. 27 June 2017.

- ^ "Ensenada Tuk Tuk, Beach and Bar | Ensenada Shore Excursion | Mexican Riviera Cruise Tours". Shore Excursions Group.

- ^ "gpsKevin Adventure Rides - Tuk Tuk Oaxaca". www.gpskevinadventurerides.com. Retrieved 2025-01-15.

- ^ Hilden, Nick (2024-05-06). "Everything I Learned on Mexico's New Highway Connecting Oaxaca City to the Coast". Thrillist. Retrieved 2025-01-15.

- ^ "Motocar". Perú Motor. Archived from the original on 3 October 2018.

- ^ Tony Dunnell (28 July 2017). "A Traveler's Guide to Mototaxis in Peru". tripsavvy. Retrieved 27 November 2017.

- ^ Schultz, Amber (April 15, 2023). "Australian man's seven-year tuk-tuk journey from Argentina to Alaska". The Sydney Morning Herald.

- ^ https://www.couriermail.com.au/news/queensland/trouble-strikes-ryan-magee-aussieespanol-on-his-tuk-tuk-travels/news-story/de5faae1816a5b51c9f7626624a7e4f1?amp&nk=11387282b59daa33d2f6f4a6926d7d47-1740345984

- ^ Williams, Lachlan (January 29, 2020). "Uber Launches "Tuk-tuk" in Brazil".

- ^ "THE TUK TUK IS HERE TO STAY IN BRAZIL". June 21, 2012.

- ^ "Bajaj Auto Confirms Production Unit In Brazil; Expands Global Production To 100 Countries". News18.

- ^ García, Jessica Paola Vera (August 28, 2023). "En Colombia, 10% de las personas que se movilizan lo hacen en "Tuk Tuks"". El Carro Colombiano.

- ^ Hart, Amalyah (2023-05-16). "Electric tuk tuks to make deliveries for Ikea customers in Sydney". The Driven. Retrieved 2025-01-15.

- ^ "Tuk Tuk Tours". Just Tuk'n Around. Retrieved 2025-01-15.

- ^ "Tuk-tuk trial on Canterbury salmon farm". Otago Daily Times. 2024-04-19. Retrieved 2025-01-15.

- ^ "Wanaka taxi Services by Tuk Tuk Taxi | Call now-0800885800". Retrieved 2025-01-15.

- ^ a b "Tuk tuk start up hits red tape speed bump". The New Zealand Herald. 2016-08-17. Retrieved 2025-01-15.

- ^ "Engineer penalised for signing off on Auckland tuk-tuk safety despite having never viewed them". 1News. Retrieved 2025-01-15.

- ^ "Kiwi Tuk Tuk Limited | GetYourGuide Supplier". GetYourGuide. Retrieved 2025-01-15.

- ^ "Envirofit's Tricycle Retrofit Program Funded". Colorado State University. 19 May 2006. Archived from the original on 29 September 2011. Retrieved 2011-03-22.

- ^ "Microsoft Word – SETC_LPG2T.doc" (PDF). Retrieved 2010-04-03.

- ^ "Bajaj rolls out low-emission fuel-efficient autorickshaw". Business Line. The Hindu. 2007-12-09. Retrieved 2010-04-03.

- ^ "Bajaj Begins Production of 2-Stroke Direct-Injection Auto Rickshaw". Green Car Congress. 2007-05-18. Retrieved 2010-04-03.

- ^ "A fleet of hydrogen rickshaws to circulate in New Delhi by 2010". International Centre for Hydrogen Energy Technologies. Archived from the original on 2011-07-28. Retrieved 2011-03-22.

- ^ "Hydrogen-Fueled Internal Combustion Engines, see page 7".

- ^ "Clean Hydrogen Technology for 3-Wheel Transportation in India" (PDF).

- ^ a b "India Showcases Hydrogen Fuel Auto-Rickshaws |". 21 February 2012.

- ^ "Highest altitude achieved in an auto rickshaw".

- ^ "Look: Auto rickshaws take world's highest road to set world record - UPI.com". UPI.

- ^ "Highest altitude road". Guinness World Records.

External links

[edit]- The India 1000 – an article in Wired about auto rickshaw racing

Auto rickshaw

View on GrokipediaDesign and Technology

Basic Configuration and Features

Auto rickshaws feature a three-wheeled configuration with a single steerable front wheel and two rear wheels driven by a rear-mounted engine, enabling tight maneuverability in congested urban environments.[5] The chassis is typically a narrow tubular steel frame, approximately 1,800-2,000 mm in wheelbase length, supporting a gross vehicle weight of around 780 kg when fully loaded.[6][7] The body consists of a sheet-metal or fiberglass enclosure with the driver seated upfront behind a handlebar steering mechanism, and a rear bench accommodating two to three passengers, often protected by drop-down side curtains and a canvas or metal roof.[8] Dimensions generally range from 2.8-3.2 meters in length, 1.4-1.6 meters in width, and 1.8-2.0 meters in height, optimized for narrow streets.[7] Standard propulsion involves a single-cylinder, air-cooled petrol engine with displacements of 145-236 cc, delivering 7-10 horsepower at speeds up to 65 km/h, paired with a 4-speed manual transmission including reverse.[5][9] Braking is provided by hydraulic drums on all wheels, while basic suspension uses leaf springs for load-bearing stability.[5] Fuel capacity stands at 8-10 liters, supporting operational ranges suitable for intra-city travel.[2] Essential features include front headlights, indicators, a horn, and often a fare meter, with variants incorporating CNG or electric systems for emissions compliance.[3][2]Propulsion Systems and Variants

Auto rickshaws predominantly utilize single-cylinder, air-cooled, four-stroke internal combustion engines with displacements ranging from 198 to 470 cc, optimized for low-speed urban operation and fuel efficiency.[10] Traditional petrol variants, such as those in Bajaj RE models, feature a 236.2 cc engine delivering 7.7 kW at around 5000 rpm, paired with a multi-plate wet clutch and four-speed manual transmission.[1] These engines evolved from polluting two-stroke designs prevalent until the early 2000s, which emitted high levels of particulate matter and hydrocarbons, prompting shifts to cleaner four-stroke configurations compliant with emissions standards like BS-IV and BS-VI in India.[11] Compressed natural gas (CNG) propulsion systems represent a key variant, using dedicated or bi-fuel setups on similar 236.2 cc bases but detuned to 6.90 kW for gaseous fuel, reducing carbon monoxide and particulate emissions by up to 80% compared to petrol equivalents; these are widespread in polluted megacities like Delhi, where over 100,000 CNG auto rickshaws operate under regulatory mandates.[10] Liquefied petroleum gas (LPG) variants employ comparable 236 cc engines producing up to 9.9 HP and 17.65 Nm torque, offering dual-fuel flexibility and lower costs in regions with subsidized LPG availability, as seen in models from Bajaj and TVS.[12] Diesel-powered options, less common due to higher noise and maintenance, utilize larger 470.5 cc engines at 6.24 kW, suited for cargo variants requiring greater torque on inclines up to 18 degrees.[10] Electric propulsion has gained traction since the mid-2010s, driven by government incentives like India's FAME-II scheme, featuring brushless DC (BLDC) motors rated 1000-1300 W for peak efficiency and regenerative braking, powered by 48-60 V batteries yielding ranges of 80-120 km per charge.[13] These systems eliminate tailpipe emissions and reduce operating costs by 50-70% versus fossil fuels, though challenges include battery life and charging infrastructure; by 2023, electric models comprised over 20% of new registrations in select markets.[14] Variants include lead-acid for affordability and lithium-ion for extended range, with hub-mounted motors enhancing maneuverability in congested traffic.[15]Capacity and Maneuverability

Auto rickshaws are designed with a seating capacity for one driver and typically two to three passengers on a rear bench, though certain models are rated for up to four persons total.[10][16] The Bajaj RE, a widely produced variant, specifies a capacity of four persons including the driver, with a gross vehicle weight of 672 kg to support this load.[2][10] Regulations in regions like India often limit legal occupancy to three passengers plus driver to ensure safety, but overloading remains common in practice despite risks to stability and braking.[17] Maneuverability stems from the vehicle's three-wheeled configuration and compact footprint, enabling operation in narrow urban lanes and dense traffic where larger vehicles cannot navigate.[18] Typical dimensions include a length of 2.6 to 3.1 meters, width of 1.3 to 1.5 meters, and wheelbase of 1.6 to 2.2 meters, reducing the turning radius to under 4 meters—often 2.8 to 2.9 meters in models like the Bajaj RE and Mahindra Treo.[2][19][7] This allows for a minimum turning circle of approximately 5.76 meters, facilitating sharp turns and evasion of obstacles in congested settings.[20] The rear-mounted engine and lightweight chassis—curb weights around 400 kg—further aid agility, with gradeability up to 18% on inclines and quick acceleration from standstill.[17][2] Such attributes make auto rickshaws suitable for short-haul trips in high-density areas, though the design limits high-speed stability and increases rollover risk during evasive actions.[18]History

Origins and Early Motorization

The human-pulled rickshaw, the precursor to the auto rickshaw, originated in Japan in 1869, developed as a lightweight, two-wheeled passenger cart drawn by one or two pullers to meet urban transport demands during rapid modernization.[21] This invention, attributed to figures like Izumi Yosuke, quickly proliferated across Asia, reaching India by around 1880 and becoming a staple for short-distance travel in densely populated cities, though it relied heavily on manual labor.[22] Cycle rickshaws, pedaled by the operator, emerged in the early 20th century as a partial mechanization, appearing in Japan, India, and Southeast Asia by the 1920s and 1930s, offering greater efficiency but still limited by human power.[21] Early motorization addressed the physical strain on operators and scalability issues of pulled variants, with the first dedicated three-wheeled motorized vehicles appearing in Japan in the early 1930s. Toyo Kogyo (later Mazda) introduced the Mazda-Go Type-DA in 1931, a three-wheeled open truck powered by a 475 cc single-cylinder engine producing about 15 horsepower, initially designed for cargo but soon adapted for passenger transport in urban settings.[23] This model, with its rear-mounted engine and single front wheel for steering, marked a pivotal shift toward affordable motorized tricycles, influencing subsequent designs; Daihatsu concurrently released similar vehicles like the HB in 1931.[23] These early prototypes prioritized simplicity, low cost, and maneuverability over speed, achieving top velocities around 40-50 km/h, and were produced amid Japan's industrial expansion to support small-scale logistics and personal mobility.[23] Post-World War II reconstruction accelerated global adoption, with Italian manufacturers like Piaggio introducing the Ape in 1948—a diesel-powered three-wheeler for both cargo and passengers—that influenced exports to Asia.[24] In India, motorized rickshaws first appeared in the mid-20th century, with initial imports and local assembly in cities like Coimbatore, Tamil Nadu; Bajaj Auto launched domestic production of the Bajaj Auto-Rickshaw in 1959, licensing designs from Italian firms to meet rising urban demand.[22][25] This transition from human- or pedal-powered to engine-driven forms reduced operator fatigue, increased carrying capacity to 2-4 passengers, and facilitated integration into informal transport networks, though early models suffered from basic suspension and open cabins vulnerable to weather.[25]Post-War Global Adoption

In Italy, the Piaggio Ape, a three-wheeled vehicle designed by aeronautical engineer Corradino D'Ascanio in 1947, entered production in 1948 to address post-World War II transportation shortages.[26][27] Intended initially for agricultural and commercial use, its lightweight construction, powered by a 125 cc or 150 cc two-stroke engine producing around 4 horsepower, enabled affordable passenger services in urban areas amid economic reconstruction.[28] By the early 1950s, variants like the Ape Calessino facilitated taxi operations, with over 100,000 units produced by 1956, marking early European adoption of motorized three-wheelers for low-cost mobility.[29] Japanese manufacturers contributed to Asian adoption through post-war exports of compact three-wheelers, such as the Daihatsu Midget introduced in 1957, which featured a rear-mounted 350 cc engine and open passenger compartment suited for narrow streets.[30] In Thailand, tuk-tuks—evolving from pre-war cycle rickshaws—saw motorized versions imported from Japan proliferate in the 1960s, with the characteristic two-stroke engine noise earning the onomatopoeic name; by then, they numbered in the thousands in Bangkok, supplanting human- or pedal-powered alternatives amid rapid urbanization.[31][32] Indonesia followed suit, with bajay auto rickshaws appearing in cities like Jakarta post-1950, often based on licensed Japanese or local adaptations for short-haul passenger and goods transport in congested tropical environments.[32] In India, commercial introduction occurred in 1959 when Bajaj Auto imported and assembled Italian-inspired three-wheelers, equipped with 200 cc engines delivering about 9 horsepower, initially in Pune before spreading to Mumbai and other cities; this followed experimental motorized rickshaws in Coimbatore during the mid-1950s.[25][22] By 1961, Bajaj's local production under license from Piaggio scaled output to meet demand, with vehicles carrying up to three passengers at speeds of 40-50 km/h, filling gaps left by limited bus services and high fuel costs for cars.[33] This era's adoption emphasized durability in high-heat conditions and minimal maintenance, driving fleet growth to over 10,000 units nationwide by the late 1960s.[25] Broader diffusion to other regions, including early experiments in the Philippines and Middle Eastern markets, relied on Japanese and Italian blueprints, but sustained growth occurred primarily in South and Southeast Asia where infrastructure deficits favored nimble, fuel-efficient vehicles; by the 1970s, annual production in India alone exceeded 50,000, underscoring their role in informal economies.[32][33]Evolution in Manufacturing Hubs

The manufacturing of auto rickshaws began in Italy, where Piaggio introduced the Ape three-wheeler in 1948 at its Pontedera plant near Pisa, initially as a lightweight commercial vehicle derived from Vespa scooter technology to aid post-World War II reconstruction.[34] This marked the origin of enclosed cabin three-wheelers suitable for passenger transport, with early production focused on domestic European markets before evolving into global exports.[35] Piaggio's design emphasized durability and simplicity, influencing subsequent adaptations worldwide. In 1959, Indian firm Bajaj Auto secured a licensing agreement with Piaggio to produce the Ape in Pune, establishing India as the primary manufacturing hub for auto rickshaws tailored to emerging markets.[36] Production commenced with limited capacity of 1,000 units monthly, but expanded rapidly after 1962 approvals, enabling Bajaj to adapt the design for local fuels and conditions like CNG compatibility.[37] By the 1980s, additional Indian manufacturers such as Atul Auto and Force Motors entered the sector, while TVS Motors launched its King model in 2008, incorporating two-stroke engines in 200 cc variants for CNG, LPG, and petrol.[38] India's output surged to over one million three-wheelers annually by 2018, with Bajaj dominating as the global leader and exporting to regions including Africa, Southeast Asia, and the Middle East.[39] Parallel developments occurred in China from the early 2000s, where factories in provinces like Henan and Chongqing began mass-producing low-cost auto rickshaw copies and electric variants, often based on Indian designs but optimized for battery power and urban logistics.[40] This shift supported China's dominance in electric three-wheeler volumes, exceeding India's in lighter cargo categories by the 2010s, though passenger auto rickshaws remained India-centric. Local assembly hubs also emerged in Pakistan (Lahore) and Indonesia (via Piaggio's facilities), relying on imported components or licensed production to customize for regional regulations like CNG mandates.[41] Overall, the evolution centralized high-volume, affordable manufacturing in Asia, transitioning from European innovation to Indian scale and Chinese electrification.Economic and Social Role

Employment Generation and Informal Economy

Auto rickshaws serve as a significant source of employment in urban centers of developing economies, particularly in South Asia, where low entry barriers enable absorption of surplus labor from rural areas and informal migrants. In India, the sector supports approximately 6.3 million registered commercial auto-rickshaws, which constitute the primary or sole income source for millions of households, often involving self-employment or vehicle rental arrangements.[42] This model thrives due to minimal capital requirements—typically under $2,000 for vehicle purchase or rental—and basic operational skills, allowing individuals with limited education to enter the market rapidly.[43] The informal nature of auto rickshaw operations aligns with broader patterns in developing countries' transport sectors, where privately owned vehicles fill gaps left by underfunded public systems, generating livelihoods without formal contracts or benefits. Drivers frequently operate on a cash-based, unregulated basis, contributing to the informal economy's estimated 50-60% share of urban employment in regions like India and Bangladesh.[44] For instance, battery-operated variants have employed previously jobless individuals, with studies showing 21% of operators transitioning from unemployment, though earnings remain volatile, averaging $150-250 monthly after expenses.[43] In Sri Lanka, three-wheeler taxis similarly sustain over 1 million drivers, reflecting regional reliance on such vehicles for economic resilience amid formal job scarcity.[45] While fostering entrepreneurship, the sector's informality exposes workers to risks like income instability and lack of social protections, as operations evade taxes and regulations, sustaining a parallel economy that underpins urban mobility but strains infrastructure. Government data indicate annual registration growth of 8.2% in India over the past decade, amplifying employment but intensifying competition and downward pressure on fares.[42] Electric conversions, promoted since 2020, have created over 1 million additional jobs in manufacturing and charging networks, yet persist within informal frameworks dominated by individual operators rather than structured firms.[46] This dynamic underscores auto rickshaws' role in causal employment chains, linking vehicle production, maintenance, and daily services to poverty alleviation, albeit with persistent vulnerabilities to fuel costs and policy shifts.[47]Impact on Urban Mobility and Accessibility

Auto rickshaws enhance urban mobility in densely populated developing cities by providing affordable, on-demand paratransit that bridges gaps in formal public transport systems, particularly for short intra-city trips. In Indian urban areas, they constitute 10-20% of daily commuting trips as part of the intermediate public transport sector, enabling low-income residents to access employment, markets, and services without reliance on walking or costly private vehicles.[48] Their flexibility in routing and scheduling addresses the limitations of fixed-route buses and metros, which often fail to serve peripheral or irregularly timed demands.[49] The vehicles' compact design and maneuverability permit operation in narrow alleys and congested thoroughfares inaccessible to larger transport modes, thereby improving accessibility in informal settlements and high-density neighborhoods common in South Asian and Southeast Asian cities. This capability supports last-mile connectivity to mass transit hubs, reducing effective travel distances and times for users who might otherwise forgo trips due to infrastructural barriers.[49] [50] Door-to-door service further democratizes mobility, allowing elderly individuals, families with children, and those carrying goods to reach destinations efficiently without fixed stops.[51] With around 8 million auto rickshaws operating across India, they collectively handle millions of passenger trips daily, supplementing public systems during peak loads and providing off-peak availability that sustains economic activity in informal urban economies.[52] In contexts like Delhi and Mumbai, this modal integration has empirically lowered barriers to urban participation for marginalized groups, though benefits are constrained by regulatory inconsistencies that can lead to uneven service distribution.[53] Electric variants, increasingly adopted, amplify these effects by offering quieter, lower-emission options that maintain accessibility while mitigating some environmental drawbacks of fossil-fuel models.[54]Driver Livelihoods and Market Dynamics

Auto rickshaw drivers, predominantly in densely populated urban areas of South Asia, often operate under precarious financial conditions, with many financing vehicle purchases through high-interest loans that result in persistent debt obligations. In India, a key market, drivers frequently rent vehicles from owners on a daily basis, paying fees that can consume 20-30% of gross earnings, while owner-drivers grapple with repayment schedules amid volatile fuel costs and maintenance expenses.[47][55] Income irregularity stems from fluctuating demand, weather, and competition, compelling drivers to work extended shifts of 10-14 hours daily to meet basic needs, though empirical data on average net earnings remains limited and city-specific.[56][57] Market dynamics are shaped by oversupply and technological shifts, with India registering 1.22 million three-wheeler sales in calendar year 2024, including 691,000 electric units that captured 56% of the segment and pressured traditional CNG or petrol models through lower operating costs.[58] This proliferation fosters intense intra-driver competition for fares, exacerbated by informal entry barriers and lax permit enforcement, leading to fare undercutting and congestion in high-demand zones. The rise of digital platforms has further disrupted equilibria, as aggregators like Uber and Ola initially imposed 20-25% commissions that eroded driver margins, prompting adaptations such as zero-commission subscription models adopted by Uber for auto-rickshaws in February 2025 to counter homegrown rivals emphasizing driver retention.[59][60] Regulatory interventions and electrification incentives influence livelihoods by altering cost structures; government-backed financing for electric conversions reduces long-term fuel expenses by up to 50%, yet upfront debt for battery-equipped vehicles burdens low-capital drivers, with repayment periods extending 3-5 years.[61] In competitive markets, this transition favors operators accessing subsidized loans or fleet programs, widening disparities between financed owner-drivers and renters who face stalled upgrades. Platform integration offers income stabilization via algorithm-dispatched rides but introduces dependency on app policies, where algorithmic pricing and surge dynamics can amplify earnings volatility during peak hours while sidelining non-digitized drivers.[62] Overall, these dynamics sustain auto-rickshaws as a vital informal sector buffer against unemployment, employing millions amid urban migration, though without structural reforms to debt relief and fare standardization, driver precarity persists.[63]Regional Variations

South Asia

In India, auto rickshaws form a cornerstone of urban paratransit, with electric models achieving 54.41% market penetration among three-wheelers by 2024, driven by subsidies and infrastructure for charging.[64] Sales of electric three-wheelers, including passenger rickshaws, totaled 699,000 units in fiscal year 2025 ending March, led by manufacturers Bajaj Auto and Mahindra & Mahindra.[65] Major producers like Piaggio, Atul Auto, and TVS supply both compressed natural gas (CNG) and electric variants, with CNG models prevalent in polluted metros such as Delhi to comply with emission norms.[66] Regional adaptations include color-coded vehicles by state—yellow-black in Mumbai, green in Delhi—and cargo variants for logistics in rural areas.[67] In Pakistan, auto rickshaws coexist with chingchi (or qingqi) three-wheelers, which are motorcycle-based designs locally assembled by companies like Sazgar Engineering, offering lower costs for informal operators.[68] These vehicles dominate short-haul transport in cities like Lahore and Karachi, though 2025 municipal bans in Lahore cited safety risks from overloading and poor roadworthiness, sparking protests among drivers reliant on daily earnings.[69] Traditional Indian-style rickshaws, often imported, face competition from chingchis, which prioritize affordability over enclosed cabins. Bangladesh features predominantly CNG-fueled auto rickshaws, with approximately 309,000 registered nationwide as of recent estimates, concentrated in Dhaka where numbers are capped to mitigate congestion.[70] Regulations limit operations on main arterial roads, prompting 2024 debates over partial bans versus expanded quotas up to 40,000 vehicles in the capital to balance accessibility and traffic flow.[71] [72] Electric rickshaws are emerging but face enforcement challenges alongside illegal battery-powered variants.[73] In Sri Lanka, auto rickshaws—locally termed trishaws—are largely Indian Bajaj imports modified for local roads, serving as metered taxis in urban centers like Colombo despite competition from buses and three-wheel motorcycles.[74] Across South Asia, common variations include shared rides accommodating up to six passengers informally, though official capacity limits three, and widespread refusal of meters leads to negotiated fares.[75]Southeast and East Asia

In Thailand, tuk-tuks—three-wheeled motorized rickshaws with open-air seating for two to three passengers—serve as a primary short-distance transport mode in urban centers like Bangkok, where they navigate congested streets efficiently. Originating from Japanese designs in the 1930s and introduced post-World War II, these vehicles typically feature a single front wheel, two rear wheels, and two-stroke or four-stroke engines, though adoption of electric models dropped from 32% to 13% between 2023 and 2024 amid infrastructure challenges.[30][76] Fares are often negotiated rather than metered, with new 2025 ride-hailing regulations requiring public transport registration, valid public driving licenses, and identity verification to enhance safety and curb scams.[77] In Indonesia, bajaj auto rickshaws, imported from India's Bajaj Auto since the 1970s, consist of enclosed three-wheeled vehicles with two-stroke engines and have become an urban fixture, particularly in Jakarta, where they handle passenger loads in dense traffic. These models, known for their distinctive three-wheeled design and colorful exteriors, peaked in popularity four decades ago but face phase-outs in several cities due to high emissions and replacement by four-wheeled alternatives.[78] Regulations restrict new bajaj registrations in Jakarta to reduce pollution, though existing units persist in informal operations.[79] The Philippines relies heavily on motorized tricycles—motorcycle-based three-wheelers with sidecar attachments accommodating four to six passengers—as a staple of public transport in both urban and rural settings, filling gaps left by jeepneys and buses. These vehicles, often locally assembled, operate under local government franchises but are prohibited on national highways by Department of Transportation policies since at least 2023 to mitigate accident risks from their low speeds and instability.[80] Electric variants are proliferating rapidly, with minimal national oversight, enabling widespread use for last-mile connectivity despite safety concerns like overloading.[81] In Cambodia and Laos, tuk-tuks adapted from motorcycle-trailer configurations (remorques) or standalone three-wheelers provide tourist and local transport in cities like Phnom Penh and Vientiane, typically seating two to four passengers in open cabins powered by small engines. These evolved from post-colonial imports and remain unregulated in fares but integral to informal economies, with Cambodia's versions often featuring welded frames for durability on uneven roads.[82] Vietnam features fewer motorized rickshaws, favoring cyclos (pedal versions) or motorbike taxis, though three-wheelers appear in tourist hubs like Hanoi for short hauls.[83] In East Asia, auto rickshaws have largely declined from early 20th-century prominence. Japan pioneered motorized three-wheelers like the 1930s Daihatsu Midget but phased them out by the mid-20th century in favor of automobiles and rail, rendering them obsolete in modern urban transport.[30] China employs electric three-wheelers akin to rickshaws in tier-3 cities and rural areas for cargo and passenger services, but strict urban bans and India's 2023 overtake in e-rickshaw production highlight regulatory curbs on emissions and congestion.[8] South Korea sees negligible current use, with historical reliance on human-pulled variants during the colonial era supplanted by motorized alternatives post-1950s.[84]Africa and Middle East

Auto rickshaws, often referred to as tuk-tuks, serve as vital informal transport in several African nations, filling gaps in formal public systems with low-cost, door-to-door service. Introduced primarily from Asian manufacturers like India in the early 2000s, they proliferated in urban peripheries and low-income areas where buses and minibuses are insufficient.[85] [86] In Egypt, tuk-tuks appeared unofficially around 2005, gaining official licensing in 2008, and numbered approximately 6 million by 2015, though licensed vehicles stood at 2.5 million by mid-2021.[87] [88] These vehicles, typically imported in parts and assembled locally, are shared among 2-3 drivers who purchase them for around $2,760 as of 2014, operating in congested slums of Cairo and other cities.[85] [89] Regulatory challenges persist across the region, with governments imposing import restrictions and crackdowns on unlicensed operations due to safety and traffic concerns. In Egypt, a 2014 one-year import halt and intensified policing targeted unregulated tuk-tuks, while recent plans for emission reductions have raised driver apprehensions amid soaring vehicle prices from import bans and inflation.[90] [91] In South Africa, tuk-tuks emerged in Johannesburg around 2010-2015, offering short-haul trips and competing with metered taxis, with operational studies noting average speeds of 20-30 km/h and user preferences for affordability over minibuses.[92] Cape Town permitted limited tuk-tuk operations in tourist areas like the Waterfront since April 2013, restricting trips to 3 km.[93] Further south and west, adoption varies by country. Nigeria's keke-marwa tuk-tuks dominate in cities like Uyo and Lagos, providing essential mobility in high-density informal economies.[86] In Sudan, known as raksha, they constitute the primary transport mode in Khartoum alongside buses.[74] Ghana's Kumasi sees auto-rickshaws as a rising alternative to tricycles, with operator surveys indicating high daily revenues but vulnerability to fuel price fluctuations.[94] In the Middle East, usage centers on Egypt's overlap with North Africa, though smuggling networks supply tuk-tuks to Gaza despite import bans by Egypt and Israel. Afghanistan features widespread tuk-tuks in cities like Herat, adapted for rugged terrains but facing similar regulatory hurdles.[74] Across these regions, tuk-tuks enhance accessibility for the urban poor but contribute to congestion and accident risks, prompting ongoing debates over formal integration versus phase-outs. Economic analyses in Egypt highlight low operating costs offset by high maintenance, sustaining driver livelihoods despite informal status.[95] [96]Americas and Europe