Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

University of Bonn

View on Wikipedia

The University of Bonn, officially the Rhenish Friedrich Wilhelm University of Bonn (German: Rheinische Friedrich-Wilhelms-Universität Bonn), is a public research university in Bonn, North Rhine-Westphalia, Germany. It was founded in its present form as the Rhein-Universität (English: Rhine University) on 18 October 1818 by Frederick William III, as the linear successor of the Kurkölnische Akademie Bonn (English: Academy of the Prince-elector of Cologne) which was founded in 1777. The University of Bonn offers many undergraduate and graduate programs in a range of subjects and has 544 professors. The University of Bonn is a member of the German U15 association of major research-intensive universities in Germany and has the title of "University of Excellence" under the German Universities Excellence Initiative.

Key Information

Bonn has 6 Clusters of Excellence, the most of any German university;[4] the Hausdorff Center for Mathematics, the Matter and Light for Quantum Computing cluster, Bonn Center for Dependency and Slavery Studies, PhenoRob: Research for the Future of Crop Production, the Immune Sensory System cluster, and ECONtribute: Markets and Public Policy. The University and State Library Bonn (ULB Bonn) is the central university and archive library of the Rheinische Friedrich-Wilhelms-Universität Bonn and North Rhine-Westphalia; it holds more than five million volumes.

As of October 2020,[update] among its notable alumni, faculty and researchers are 11 Nobel Laureates, 5 Fields Medalists, 12 Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz Prize winners as well as some of the most gifted minds in Natural science, e.g. August Kekulé, Heinrich Hertz and Justus von Liebig; Eminent mathematicians, such as Karl Weierstrass, Felix Klein, Friedrich Hirzebruch and Felix Hausdorff; Major philosophers, such as Friedrich Nietzsche, Karl Marx, and Jürgen Habermas; German poets and writers, for example Heinrich Heine, Paul Heyse and Thomas Mann; Painters, like Max Ernst; Political theorists, for instance Carl Schmitt and Otto Kirchheimer; Statesmen, viz. Konrad Adenauer and Robert Schuman; economists, like Walter Eucken, Ferdinand Tönnies and Joseph Schumpeter; and furthermore Prince Albert, Pope Benedict XVI and Wilhelm II.

History

[edit]Foundation

[edit]The university's forerunner was the Kurkölnische Akademie Bonn (English: 'Academy of the Prince-elector of Cologne') which was founded in 1777 by Maximilian Frederick of Königsegg-Rothenfels (who was also one of the first employers of Beethoven), the prince-elector of Cologne. In the spirit of the Enlightenment the new academy was nonsectarian. The academy had schools for theology, law, pharmacy and general studies. In 1784 Emperor Joseph II granted the academy the right to award academic degrees (Licentiat and Ph.D.), turning the academy into a university. The academy was closed in 1798 after the left bank of the Rhine was occupied by France during the French Revolutionary Wars.

The Rhineland became a part of Prussia in 1815 as a result of the Congress of Vienna. King Frederick William III of Prussia thereafter decreed the establishment of a new university in the new province (German: den aus Landesväterlicher Fürsorge für ihr Bestes gefaßten Entschluß, in Unsern Rheinlanden eine Universität zu errichten) on 18 October 1818. At this time there was no university in the Rhineland, as all three universities that existed until the end of the 18th century were closed as a result of the French occupation. The Kurkölnische Akademie Bonn was one of these three universities. The other two were the Roman Catholic University of Cologne and the Protestant University of Duisburg.

Rhine University

[edit]

The new Rhine University (German: Rhein-Universität) was then founded on 18 October 1818 by Frederick William III. It was the sixth Prussian University, founded after the universities in Greifswald, Berlin, Königsberg, Halle and Breslau. The new university was equally shared between the two Christian denominations. This was one of the reasons why Bonn, with its tradition of a nonsectarian university, was chosen over Cologne and Duisburg. Apart from a school of Roman Catholic theology and a school of Protestant theology, the university had schools for medicine, law and philosophy. Initially 35 professors and eight adjunct professors were teaching in Bonn.

The university constitution was adopted in 1827. In the spirit of Wilhelm von Humboldt the constitution emphasized the autonomy of the university and the unity of teaching and research. Similar to the University of Berlin, which was founded in 1810, the new constitution made the University of Bonn a modern research university.

Only one year after the inception of the Rhein University the dramatist August von Kotzebue was murdered by Karl Ludwig Sand, a student at the University of Jena. The Carlsbad Decrees, introduced on 20 September 1819 led to a general crackdown on universities, the dissolution of the Burschenschaften and the introduction of censorship laws. One victim was the author and poet Ernst Moritz Arndt, who, freshly appointed university professor in Bonn, was banned from teaching. Only after the death of Frederick William III in 1840 was he reinstated in his professorship. Another consequence of the Carlsbad Decrees was the refusal by Frederick William III to confer the chain of office, the official seal and an official name to the new university. The Rhine University was thus nameless until 1840, when the new King of Prussia, Frederick William IV gave it the official name Rheinische Friedrich-Wilhelms-Universität. (This last sentence conflicts with pg. 176 of Die Preussischen Universitäten, which states a cabinet order on 28 June 1828 gave the university the following name: Rheinische Friedrich-Wilhelms Universität.)[5]

Despite these problems, the university grew and attracted scholars and students. At the end of the 19th century the university was also known as the Prinzenuniversität (English: 'Princes' university'), as many of the sons of the king of Prussia studied here. In 1900, the university had 68 chairs, 23 adjunct chairs, two honorary professors, 57 Privatdozenten and six lecturers. Since 1896, women were allowed to attend classes as guest auditors at universities in Prussia. In 1908 the University of Bonn became fully coeducational.

World Wars

[edit]

The growth of the university came to a halt with World War I. Financial and economic problems in Germany in the aftermath of the war resulted in reduced government funding for the university. The University of Bonn responded by trying to find private and industrial sponsors. In 1930 the university adopted a new constitution. For the first time students were allowed to participate in the self-governing university administration. To that effect the student council Astag (German: Allgemeine Studentische Arbeitsgemeinschaft) was founded the same year. Members of the student council were elected in a secret ballot.

After the Nazi takeover of power in 1933, the Gleichschaltung transformed the university into a Nazi educational institution. According to the Führerprinzip the autonomous and self-governing administration of the university was replaced by a hierarchy of leaders resembling the military, with the university president being subordinate to the ministry of education. Jewish professors and students and political opponents were ostracized and expelled from the university. The theologian Karl Barth was forced to resign and to emigrate to Switzerland for refusing to swear an oath to Hitler. The Jewish mathematician Felix Hausdorff was expelled from the university in 1935 and committed suicide after learning about his impending deportation to a concentration camp in 1942. The philosophers Paul Ludwig Landsberg and Johannes Maria Verweyen were deported and died in concentration camps. In 1937 Thomas Mann was deprived of his honorary doctorate. His honorary degree was restored in 1946.

During the second World War the university suffered heavy damage. An air raid on 18 October 1944 destroyed the main building.[citation needed]

Post-war to Modern Day

[edit]

The university was re-opened on 17 November 1945 as one of the first in the British occupation zone. The first university president was Heinrich Matthias Konen, who had been expelled from the university in 1934 because of his opposition to Nazism. At the start of the first semester on 17 November 1945 the university had more than 10,000 applicants for only 2,500 places.

The university greatly expanded in the postwar period, in particular in the 1960s and 1970s. Significant events of the postwar era were the relocation of the university hospital from the city center to Venusberg in 1949, the opening of the new university library in 1960 and the opening of a new building, the Juridicum, for the School of Law and Economics in 1967.

In 1980 the Pedagogical University Bonn was merged into the University of Bonn, although eventually all the teachers education programs were closed in 2007. In 1983 the new science library was opened. In 1989 Wolfgang Paul was awarded the Nobel Prize in Physics. Three years later Reinhard Selten was awarded the Nobel Prize in Economics. The decision of the German government to move the capital from Bonn to Berlin after the reunification in 1991 resulted in generous compensation for the city of Bonn. The compensation package included three new research institutes affiliated or closely collaborating with the university, thus significantly enhancing the research profile of the University of Bonn.

In the 2000s the university implemented the Bologna process and replaced the traditional Diplom and Magister programs with Bachelor and Master programs. This process was completed by 2007.[6]

Campus

[edit]

The University of Bonn does not have a centralized campus. The main building is the Kurfürstliches Schloss, the former residential palace of the prince-elector of Cologne in the city center. The main building was built by Enrico Zuccalli for the prince-elector of Cologne, Joseph Clemens of Bavaria from 1697 to 1705. Today it houses the faculty of humanities and theology and the university administration. The Hofgarten, a large park in front of the main building is a popular place for students to meet, study and relax. The Hofgarten was repeatedly the place for political demonstrations as for example the demonstration against the NATO Double-Track Decision on 22 October 1981 with about 250,000 participants.[7] The school of law and economics, the main university library and several smaller departments are housed in modern buildings a short distance south of the main building. The department of psychology and the department of computer science are located in a northern suburb of Bonn.

The science departments and the main science library are located in Poppelsdorf and Endenich, west of the city center, and housed in a mix of historical and modern buildings. Notable is the Poppelsdorf Palace (German: Poppelsdorfer Schloss), which was built from 1715 to 1753 by Robert de Cotte for Joseph Clemens of Bavaria and his successor Clemens August of Bavaria. Today the Poppelsdorf Palace houses the university's mineral collection and several science departments; its grounds are the university's botanical garden (the Botanische Gärten der Friedrich-Wilhelms-Universität Bonn).

The school of medicine is located on the Venusberg, a hill on the western edge of Bonn. Several residence halls are scattered across the city. In total the University of Bonn owns 371 buildings.

University Library

[edit]

The university library was founded in 1818 and started with 6,000 volumes inherited from the library of the closed University of Duisburg. In 1824 the library became legal deposit for all books published in the Prussian Rhine province. The library contained about 200,000 volumes at the end of the 19th century, and about 600,000 volumes at the outbreak of World War II. An air raid on 10 October 1944 destroyed about 200,000 volumes and a large part of the library catalog. After the war the library was housed in several makeshift locations until the completion of the new central library in 1960. The new building was designed by Pierre Vago and Fritz Bornemann and is located close to the main building. In 1983 a new library building was opened in Poppelsdorf, west of the main building. The new library building houses the science, agriculture and medicine collections. Today, the university library system comprises the central library, the library for science, agriculture and medicine and about 160 smaller libraries. It holds 2.2 million volumes and subscribes to about 14,000 journals.[8]

University Hospital

[edit]

The university hospital (German: Universitätsklinikum Bonn) was founded at the same time as the university and officially opened on 5 May 1819 in the former Electoral Palace (German: Kurfüstliches Schloss), the main building, in the western wing (internal medicine) and on the second floor (obstetrics). In its first year, the hospital had thirty beds, performed 93 surgeries and treated about 600 outpatients. From 1872 to 1883 the hospital moved to a new complex of buildings in the city center of Bonn, where today the Beethoven Concert Hall stands, and after World War II to the Venusberg on the western edge of Bonn. On 1 January 2001 the university hospital became a public corporation. Although the university hospital is since then independent from the university, the School of Medicine of the University of Bonn and the university hospital closely collaborate. Today the university hospital comprises about thirty individual hospitals, employs more than 990 physicians and more than 1,100 nursing and clinical support staff and treated about 50,000 inpatients.[9]

University Museums

[edit]

The Akademisches Kunstmuseum (English: 'Academic Museum of Antiquities') was founded in 1818 and has one of the largest collections of plaster casts of ancient Greek and Roman sculptures in the world. At this time collections of plaster casts were mainly used in the instruction of students at art academies. They were first used in the instruction of university students in 1763 by Christian Gottlob Heyne at University of Göttingen. The Akademisches Kunstmuseum in Bonn was the first of its kind, as at this time collections at other universities were scattered around universities libraries. The first director was Friedrich Gottlieb Welcker, who also held a professorship of archaeology. His tenure was from 1819 until his retirement in 1854. He was succeeded by Otto Jahn and Friedrich Wilhelm Ritschl, who shared the directorship. From 1870 to 1889 Reinhard Kekulé von Stradonitz, nephew of the organic chemist Friedrich August Kekulé von Stradonitz, was the director. In 1872 the museum moved to a new building that was formerly used by the department of anatomy. The building was constructed from 1823 to 1830 and designed by Karl Friedrich Schinkel and Hermann Friedrich Waesemann. Other directors of the museum were Georg Loeschcke (from 1889 to 1912), Franz Winter (from 1912 to 1929), Richard Delbrück (from 1929 to 1940), Ernst Langlotz (from 1944 to 1966), Nikolaus Himmelmann (from 1969 to 1994) and Harald Mielsch (since 1994). All directors, with the exception of Friedrich Wilhelm Ritschl held a professorship of archaeology at the university.[10]

The Egyptian Museum (German: Ägyptisches Museum) was founded in 2001. The collection dates back to the 19th century and was formerly part of the Akademisches Kunstmuseum. Large parts of the collection were destroyed in World War II. Today the collection comprises about 3,000 objects.[11]

The Arithmeum was opened in 1999. With over 1,200 objects it has the world's largest collection of historical mechanical calculating machines. The museum is affiliated with the Research Institute for Discrete Mathematics.[12]

The Teaching Collection of Archaeology and Anthropology (German: Archäologisch-ethnographische Lehr- und Studiensammlung) was opened in 2008. The collection comprises more than 7,500 objects of mostly pre-Columbian art.[13]

The Botanical Garden was officially founded in 1818 and is located around the Poppelsdorf Palace. A garden existed at the same place at least since 1578, and around 1720 a Baroque garden was built for Clemens August of Bavaria. The first director of the Botanical Garden was Nees von Esenbeck from 1818 to 1830. In May 2003 the world's largest titan arum, some 2.74 meters high, flowered in the Botanical Garden for three days.[14]

The natural history museum was opened in 1820 by Georg August Goldfuss. It was the first public museum in the Rhineland. In 1882 it was split into the Mineralogical Museum[15] located in the Poppelsdorf Palace and a museum of palaeontology, now named Goldfuß Museum.[16]

The Horst Stoeckel-Museum of the History of Anesthesiology (German: Horst Stoeckel-Museum für die Geschichte der Anästhesiologie) was opened in 2000 and is the largest of its kind in Europe.[17]

The Museum Koenig is one of the largest natural history museums in Germany and is affiliated with the university. The museum was founded in 1912 by Alexander Koenig, who donated his collection of mounted specimens to the public.[18]

Organization

[edit]The University of Bonn has 32,500 students, and 4,000 of these are international students. Each year about 3,000 undergraduate students graduate. The university also confers about 800 Ph.D.s and about 60 habilitations. More than 90 programs in all fields are offered. Strong fields as identified by the university are mathematics, physics, law, economics, neuroscience, medical genetics, chemical biology, agriculture, Asian and Oriental studies and Philosophy and Ethics. The university has more than 550 professors, an additional academic staff of 3,900 and an administrative staff of over 1,700. The annual budget was more than 570 million euros in 2016.[3]

Faculties

[edit]From the foundation in 1818 to 1928 the University of Bonn had five faculties, that is, the Faculty of Catholic Theology, the Faculty of Protestant Theology, the Faculty of Law and the Faculty of Arts and Science. In 1928, the Faculty of Law and the Department of Economics, that until then was part of the Faculty of Arts and Science, merged into the new Faculty of Law and Economics. In 1934 the until then independent Agricultural University Bonn-Poppelsdorf (German: Landwirtschaftliche Hochschule Bonn-Poppelsdorf) was merged into the University of Bonn as the Faculty of Agricultural Science. In 1936, the science departments were separated from the Faculty of Arts and Science. Today the university is divided into seven faculties.[19]

Faculty of Protestant Theology

[edit]

The Protestant Theological Faculty has existed at the University of Bonn since 1818 (Unlike other universities, only Bonn and the Friedrich Wilhelm University in Wroclaw, founded in 1811, had both a Catholic and a theological faculty). The thematic focuses are in the areas of "Texts of Theology", "Historical Theology", "Theory of Theology", "Theology in Dialogue with the Human Sciences" and "Ecumenical Theology". Other institutes of the faculty are the Institute of Hermeneutics and the Institute of Ecumenism. The faculty is located in the main building of the university, where the Protestant Castle Church is also located. The university preacher is Eberhard Hauschildt. The faculty operates its own dormitory for students of Protestant theology. With 187 students, it is the smallest faculty of the University of Bonn. In teacher training, the Faculty of Protestant Theology cooperates with the Institute of Protestant Theology of the University of Cologne. Numerous members of the faculty are also involved in the Center for Religion and Society of the university.

Faculty of Catholic Theology

[edit]The Faculty of Catholic Theology was also founded in 1818 with six chairs; it began teaching in the summer half of 1819. Today, the faculty comprises 13 chairs. A special feature is the workplace for theological gender research. With 243 students, it is also one of the small faculties of the university. It cooperates with the Institute for Catholic Theology of the University of Cologne and is part of the ZERG degree program. The Chair of Fundamental Theology was held by Joseph Ratzinger from 1959 to 1963, the later Pope Benedict XVI.

Faculty of Agriculture

[edit]In 1934, the Faculty of Agriculture was established at the university. It originated from the former Agricultural University Poppelsdorf, which was founded in 1847. Today, the faculty has its scientific focus in the areas of "Agrar Systems Sensing Analysis and Management", "Food and Nutrition" and "Enlightenment of genetically determined metabolic functions in crops, farm animals and humans using molecular biological methods" (From Molecules to Function: Crop - Livestock - Human). Courses of study for students include Agricultural Sciences, Nutritional and Food Sciences, Animal Sciences, as well as Geodesy and Geoinformation. The location of the faculty is the Poppelsdorf campus. The faculty has about 2,500 students. In the winter semester 2008/09, the Theodor Brinkman Research Training Group was established at the faculty.[20]

The faculty comprises the following seven institutes:

- IEL - Institute of Nutrition and Food Sciences,

- IGG - Institute for Geodesy and Geoinformation,

- ILR - Institute of Food and Resource Economics,

- ILT - Institute of Agricultural Engineering,

- INRES - Institute of Crop Sciences and Resource Protection

- IOL - Institute of Organic Agriculture,

- ITW - Institute of Animal Sciences.

Faculty of Mathematics and Natural Sciences

[edit]The Faculty of Mathematics and Natural Sciences includes the subject groups Mathematics, Computer Science, Physics-Astronomy, Chemistry, Earth Sciences, Biology, Pharmacy and Molecular Biomedicine. In 1936, the natural science subjects were separated from the Faculty of Philosophy and the Faculty of Mathematics and Natural Sciences was founded.[21] With 7,636 students, it is now one of the largest faculties of the university. The locations are spread over the districts of Castell, Endenich and Poppelsdorf.

The Department of Mathematics includes the Mathematical Institute, the Institute of Applied Mathematics, the Institute of Numerical Simulation and the Research Institute for Discrete Mathematics. The Mathematical Institute (MI) and the Institute of Applied Mathematics moved into the building of the Rhineland Chamber of Agriculture in 2009. MI is currently organizing a DFG Research Training Group on the topic of "Homotopy and Cohomology." In addition, the university has a cluster of excellence in the field of mathematics. For this reason, the Hausdorff Center for Mathematics was created. The Research Institute for Discrete Mathematics is one of the mathematical institutes of the university, but is not affiliated with the Faculty of Mathematics and Natural Sciences, but reports directly to the Senate. Fields medalist Peter Scholze was educated at and currently teaches in the department, and past fields medalists. It is part of the GlobalMathNetwork: École Normale Supérieure, New York University, Kyoto University, Peking University. The Bonn mathematics department also has established international partnerships with University of California, Berkeley, Princeton University, University of Oxford and University of Warwick.[22]

The Informatics Section includes the Institute of Computer Science and the Bonn-Aachen International Center for Information Technology (b-it). They were founded in April 2011 and emerged from the Department of Mathematics/Computer Science. The Institute of Applied Mathematics and Computer Science was founded in 1969. This institute was divided into two independent institutes in 1975. The Institute of Computer Science has been using the computer science center on the Poppelsdorf campus together with b-it since 2018.[23] The Institute of Applied Mathematics and Computer Science was founded in 1969. This institute was divided into two independent institutes in 1975.[24] The Institute of Computer Science has been using the computer science center on the Poppelsdorf campus together with b-it since 2018.[25]

The Physics-Astronomy Section includes the Institute of Physics (PI), the Institute of Applied Physics (IAP), the Argelander Institute for Astronomy (AIfA) and the Helmholtz Institute for Radiation and Nuclear Physics (HISKP).[26] Together with the University of Cologne, Bonn hosts the Bonn-Cologne Graduate School of Physics and Astronomy, which is funded by Excellence Initiatives. The Institute of Physics operates the particle accelerator ELSA and organizes the Wolfgang Paul lectures. The chairs of theoretical physics as well as some of mathematics merged into the "Bethe Center for Theoretical Physics" in 2008.[27] The Argelander Institute for Astronomy, named after the astronomer Friedrich Wilhelm Argelander, was founded in 2006 by the merger of the previous three astronomical university institutes: the Observatory, the Radio Astronomical Institute (RAIUB) and the Institute of Astrophysics and Extraterrestrial Research.

When it was built 1864 to 1867, the Old Chemical Institute was the largest institute building in the world. Today it houses the Institute of Microbiology and the Institute of Geography. The Biology Section (2019) consists of eight institutes: Institute of Evolutionary Biology and Zooecology, Institute of Genetics, Institute of Microbiology and Biotechnology, Institute of Molecular Physiology and Biotechnology of Plants (IMBIO), Institute of Cell Biology, Institute of Cellular and Molecular Botany (IZMB), Institute of Zoology, Nees Institute for Biodiversity of The IZMB as well as parts of the IMBIO and the Institute of Genetics are located in the old Soennecken building. In addition, the Zoological Research Museum Alexander Koenig and the Botanical Gardens are associated with the Department of Biology as a cooperating institute.

The Steinmann Institute for Geology, Mineralogy and Paleontology has replaced the former separate Geological Institute, Mineralogical-Petrological Institute and Institute of Paleontology since 2007. It is divided into the departments of geochemistry/petrology, geology, paleontology and geophysics and recently, since the merger with the Meteorological Institute, also meteorology. In addition, he is integrated into the Mineralogical Museum of the University of Bonn and the Paleontological Goldfuß Museum.

Faculty of Medicine

[edit]The Faculty of Medicine focuses on neurosciences, genetic foundations and genetic epidemiology of human diseases, hepato-gastroenterology, cardiovascular diseases and immunology and infectious diseases. The DFG Cluster of Excellence "ImmunoSensation: The Immune System as a Sensory Organ" approved in 2012 is largely located at the Faculty of Medicine. In the field of health care, there is a cooperation with the University Hospital Bonn. The majority of the buildings are located on Venusberg, but individual institutes are also in the city center. The institutes of the pre-clinic focus around the Anatomical Institute on Nußallee in the Poppelsdorf district. 2,699 students study at the faculty.

Faculty of Law, Economics and Social Sciences

[edit]

The Faculty of Law and Political Science, which until the Second World War was housed in the main building and then provisionally in various places, received its newly built Juridicum in 1967, a building on Adenauerallee opposite the Beethoven-Gymnasium near the University Library. The faculty currently has about 5,000 students and consists of the departments of law and economics.

The Faculty of Law currently comprises sixteen institutes for teaching. Since 1989, the Center for European Business Law has existed with an affiliated DFG Research Training Group on the subject of "Legal Issues of the European Financial Area" and a European Documentation Center. In addition, the Department of Political Science also includes the Institute for Water and Waste Management Law. This is a research institute whose task is to scientifically deal with the main questions of water law and to develop practical solutions.

The Department of Economics comprises three institutes for academic teaching as well as the research institutions Bonn Graduate School of Economics (BGSE), DFG Research Training Group on the topic of Quantitative Economics and the Laboratory for Experimental Economic Research or the Reinhard Selten Institute. Renowned and well-known members of the department are the economists Isabel Schnabel, the Leibniz Prize winner Armin Falk, Martin Hellwig and the Nobel Prize winner Reinhard Selten. The Institute for the Future of Work (IZA) and the Institute on Behaviour and Inequality (briq), are two research institutions also connected to the department. In addition, there is a cooperation with the University of California, Berkeley. In 2018, the department won the Cluster of Excellence "ECONtribute: Markets and & Public Policy" of the Excellence Initiative of the Federal and State Governments for the Reinhard Selten Institute.

Faculty of Arts

[edit]The Faculty of Arts includes the Institutes of English Studies, American Studies and Celtology, History, German Studies, Comparative Literature and Cultural Studies, Classic and Romance Philology, Communication Sciences, Oriental and Asian Studies, Philosophy, Political Science and Sociology, Psychology, Archaeology and Cultural Anthropology and the Institute of Art History.With over 8,753 students, it is the largest faculty of the university.

On the 4 May 1860, the first German-language chair for art history was established at the university; Anton Springer was appointed chair for Middle and Modern Art History. Today's Department of Art History at the Institute of Art History and Archaeology has emerged from this Institute of Art History.[citation needed] From the winter semester 2009/2010, the philosophical faculties of the University of Bonn and the University of Cologne have worked together, so that in selected courses of study, it is possible for students to attend events in both Bonn and Cologne. In February 2009, the "International Center for Philosophy North Rhine-Westphalia" was founded on an initiative of Wolfram Hogrebe. Since 2011, the Thomas Kling Poetry Lectureship has been awarded in cooperation with the Kunststiftung NRW.[28] For the 200th anniversary of the university in 2018, 110 Bonn professors, especially from the Faculty of Humanities, presented the Bonn Encyclopedia of Globality, edited by the political scientists Ludger Kühnhardt and Tilman Mayer.[29]

In addition, the following interdisciplinary centers have been set up:

- Center for Aging Cultures (ZAK)

- Center for Contemporary Historical Foundations (ZHGG)

- Centre for the Classical Tradition (CCT)

- Bonn Medieval Center (BMZ)

- Center for Cultural Studies/Cultural Studies (ZfKW)

- Bonn Asia Center (BAZ)

- Center for Global Studies (CGS)

Student Life

[edit]

The Bonn Studentenwerk (English: Student union) is one of the three oldest in Germany. Studentenwerke provide public services for the economic, social, medical and cultural support for students enrolled at German universities. In particular, they run university cafeterias, dormitories, and provide the BAföG program to finance studies with grants and loans. The national association includes multiple stakeholders of German society and collaborates with other students' affairs organizations worldwide. This includes the Uniradio BonnFM, Bonn University Shakespeare Company, Debating club of the University of Bonn (which was European Champion in 2006), and various sport clubs.

University Sports

[edit]The University of Bonn has one of the largest university sports companies in North Rhine-Westphalia, with around 200 sports facilities, 38 sports facilities throughout the city as well as two of its own sports facilities on Venusberg and Römerstraße in the Castell district of Bonn. With Hall 5, the university also operates its own gym with equipment and course rooms for all strength and endurance sports.

Rowing enjoys supra-regional importance within Bonn university sports. In their own boathouse on the banks of the Rhine, located between the two Bonn districts of Beuel and Limperich, the Bonn rowers have a diverse and modern boat park of training and racing boats at their disposal. The rowing team of the University of Bonn is one of the most traditional in the German Rowing Association and participates in regattas throughout Germany every year in partly mixed teams in four or eight. The highlight is the annual participation in the German university championships, where the Bonn rowers have repeatedly qualified for the respective final in recent years.

Academic Exchange

[edit]The Erasmus program gives students the opportunity to exchange with over 300 European higher education institutions. Moreover, the Global Exchange Program allows for study free of charge for one to two semesters at non-European partner universities of the University of Bonn.[30]

A selection of internationally leading universities in various countries that were available for Bonn exchange students in 2022 included:[31] American University, Aristotle University of Thessaloniki, Australian National University, Autonomous University of Barcelona, Charles University Prague, Chinese University of Hong Kong, Complutense University of Madrid, Durham University, Eötvös Loránd University, EPFL, Federal University of Rio Grande do Sul, Hebrew University of Jerusalem, HSE Moscow, Korea University, KU Leuven, Kyoto University, Leiden University, National University of Singapore, Paris-Saclay University, ENSAE ParisTech, Politecnico di Milano, Pompeu Fabra University, Queen's University Belfast, Sapienza University of Rome, Sciences Po, Seoul National University, Shanghai Jiao Tong University, Sorbonne University, Stockholm University, Stony Brook University, Tel Aviv University, TU Eindhoven, University College London, University of Amsterdam, University of Barcelona, University of British Columbia, University of California, Berkeley, University of California, San Diego, University of Cambridge, University of Chile, University of Coimbra, University of Copenhagen, University of Florida, University of Geneva, University of Glasgow, University of Helsinki, University of Hong Kong, University of Lisbon, University of Milan, University of Oslo, University of Oxford, University of St Andrews, University of Tennessee, University of Toronto, University of Toulouse, University of Vienna, University of Warsaw, University of Warwick, Waseda University, Weizmann Institute of Science.

Future development

[edit]Infrastructure

[edit]

The university and North Rhine-Westphalia state construction and real estate agency is investing €2 billion in refurbishing existing buildings and new construction.[32] One project currently under construction is the €55 million project constructing a 'Teaching and Research Forum I & II' that is expected to be completed by 2024. This will become a central research hub with lecture halls, a library and seminar rooms for the Economics department, the Clusters of Excellence, the Hausdorff Center for Mathematics, HPCA, and DiCe. By mid-2023 the €45 million research building for the new Leibniz Institute for the Analysis of Biodiversity Change of the Zoological Research Museum Alexander Koenig will be completed; this will allow for more collaborative research between the museum and the Department of Biology, and will house a data center, laboratories, a biobank, a cryogenic storage facility, spaces for collections, and a library. The University of Bonn is also currently replacing its chemistry building with a new €37.2 million five-story building for the chemical institutes that will house 17,750 square feet of laboratory space and 6,500 square feet of office space by 2023. From 2022, the Akademisches Kunstmuseum has been under renovation by the North Rhine-Westphalia state construction agency and expected to be completed by 2025. It will also accommodate the library, offices and lecture hall for the classical archaeology department, including providing access for teaching purposes to items in the collection.

Over €1 billion is being spent on the main building, the Electoral Palace, which will be out of service for several years and completed in 2030; this includes work on fire protection, re-wiring, and plumbing, as well as modernization of lecture halls, common areas, and offices. The Humanities departments are being accommodated in the former Zurich Insurance building on Rabinstraße throughout the construction works, while the administrative staff are being housed in the former Deutscher Herold headquarters. Both temporary locations have been equipped with library areas, seminar rooms and meeting rooms. In addition, by 2031 €128 million will be spent on a 'Forum of Knowledge' which will extend the main building on a site spanning several tens of thousands of square feet, and will be open to members of the university and city residents. The university is also planning spaces for study spaces, shops, catering, and bike parking in the extension.

Internationalization

[edit]A strategic objective of the University of Bonn since 2015 has been increasing internationality in the areas of research, teaching, and administration.[33] With this aim, since 2015 six international transdisciplinary research areas and six clusters of excellence were formed, Bonn ranked second in Germany for international co-publications in the Nature Index 2018, The Bonn International Graduate Schools (BIGS) system was expanded to twelve graduate schools, and there was continuation of the "International Doctorate" program with DAAD.

The current strategic research aims for 2025 are to increase percentage of non-German national professors to 15% of total, increase the number of joint international research projects being conducted, increase application filing and approval rates in European Union research funding programs, to build up and expand European research and innovation networks, and to raise the international profile of the Bonn International Graduate Schools (BIGS). This will include formation of a global network with the existing strategic partner universities and establishing new partners for research, teaching and administration, continuation of efforts to build up the European University of Brain and Technology (NeurotechEU) within the European University Network funding framework, choosing at least two countries in Africa, Asia and Latin America as focus countries for international cooperation, and establishment of joint doctoral programs, and expansion of bi-national doctorate programs.

The strategic teaching aims for 2025 are digital internationalization of study offerings and teaching, increasing the number of English-language bachelor's degree modules, increasing the number of incoming international exchange students (in particular bachelors programs), increase outgoing student mobility through the Global Exchange Program, improving access to underrepresented groups of students. This will include expanding the bilingually of services in central administration, enhancement of foreign language and intercultural competency acquisition opportunities as part of personnel staff skill development, further development of existing internationalization structures within the faculties, departments and institutes, digitalization of service structures for international students and academics at the University of Bonn, and increasing the University of Bonn's international marketing and public relations.

Additional strategic objectives for the university are the increased bilateral cooperation between the University of Bonn and United Nations University, increased cooperation with international academic and science organizations active in Bonn, increased cooperation with private-sector firms based in the region, increased cooperation with the City of Bonn on internationalization-relevant initiatives, and development of long-term internationalization plans aligned with the identity of the City of Bonn as a center for sustainability policy.

Academic profile

[edit]Research Institutes

[edit]

The Franz Joseph Dölger-Institute studies the late antiquity and in particular the confrontation and interaction of Christians, Jews and Pagans in the late antiquity. The institute edits the Reallexikon für Antike und Christentum, a German language encyclopedia treating the history of early Christians in late antiquity. The institute is named after the church historian Franz Joseph Dölger who was a professor of theology at the university from 1929 to 1940.[34]

The Research Institute for Discrete Mathematics focuses on discrete mathematics and its applications, in particular combinatorial optimization and the design of computer chips. The institute cooperates with IBM and Deutsche Post.[35] Researchers of the institute optimized the chess computer IBM Deep Blue.[36]

The Bethe Center for Theoretical Physics "is a joint enterprise of theoretical physicists and mathematicians at various institutes of or connected with the University of Bonn. In the spirit of Hans Bethe it fosters research activities over a wide range of theoretical and mathematical physics." Activities of the Bethe Center include a short- and long-term visitors' program, workshops on dedicated research topics, regular Bethe Seminar Series, lectures and seminars for graduate students.[37]

The German Reference Center for Ethics in the Life Sciences (German: Deutsches Referenzzentrum für Ethik in den Biowissenschaften) was founded in 1999 and is modeled after the National Reference Center for Bioethics Literature at Georgetown University. The center provides access to scientific information to academics and professionals in the fields of life science and is the only one of its kind in Germany.[38]

After the German government's decision in 1991 to move the capital of Germany from Bonn to Berlin, the city of Bonn received generous compensation from the federal government. This led to the foundation of three research institutes in 1995, of which two are affiliated with the university:

- The Center for European Integration Studies (German: Zentrum für Europäische Integrationsforschung) studies the legal, economic and social implications of the European integration process. The institute offers several graduate programs and organizes summer schools for students.[39]

- The Center for Development Research (German: Zentrum für Entwicklungsforschung) studies global development from an interdisciplinary perspective and offers a doctoral program in international development.[40]

- The Center of Advanced European Studies and Research (CAESAR) is an interdisciplinary applied research institute. Research is conducted in the fields of nanotechnology, biotechnology and medical technology. The institute is a private foundation, but collaborates closely with the university.

The Institute for the Study of Labor (German: Forschungsinstitut zur Zukunft der Arbeit) is a private research institute that is funded by Deutsche Post. The institute concentrates on research on labor economics, but is also offering policy advice on labor market issues. The institute also awards the annual IZA Prize in Labor Economics. The department of economics of the University of Bonn and the institute closely cooperate.

The Max Planck Institute for Mathematics (German: Max Planck-Institut für Mathematik) is part of the Max Planck Society, a network of scientific research institutes in Germany. The institute was founded in 1980 by Friedrich Hirzebruch.

The Max Planck Institute for Radio Astronomy (German: Max-Planck-Institut für Radioastronomie) was founded in 1966 as an institute of the Max Planck Society. It operates the radio telescope in Effelsberg.

The Max Planck Institute for Research on Collective Goods (German: Max-Planck-Institut zur Erforschung von Gemeinschaftsgütern) started as a research group in 1997 and was founded as an institute of the Max Planck Society in 2003. The institute studies collective goods from a legal and economic perspective.

The Center for Economics and Neuroscience, founded in 2009 by Christian Elger, Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz Prize winner Armin Falk, Martin Reuter and Bernd Weber, provides an international platform for interdisciplinary work in neuroeconomics.[41][42] It includes the Laboratory for Experimental Economics that can carry out computer-based behavioral experiments with up to 24 participants simultaneously, two magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scanners for interactive behavioral experiments and functional imaging, as well as a biomolecular laboratory for genotyping different polymorphisms.

Research

[edit]University of Bonn researchers made fundamental contributions in the sciences and the humanities. In physics researchers developed the quadrupole ion trap and the Geissler tube, discovered radio waves, were instrumental in describing cathode rays and developed the variable star designation. In chemistry researchers made significant contributions to the understanding of alicyclic compounds and Benzene. In material science researchers have been instrumental in describing the lotus effect. In mathematics University of Bonn faculty made fundamental contributions to modern topology and algebraic geometry. The Hirzebruch–Riemann–Roch theorem, Lipschitz continuity, the Petri net, the Schönhage–Strassen algorithm, Faltings's theorem and the Toeplitz matrix are all named after University of Bonn mathematicians. University of Bonn economists made fundamental contributions to game theory and experimental economics. Thinkers that were faculty at the University of Bonn include the poet August Wilhelm Schlegel, the historian Barthold Georg Niebuhr, the theologians Karl Barth and Joseph Ratzinger and the poet Ernst Moritz Arndt.

The university has nine collaborative research centres and five research units funded by the German Science Foundation and attracts more than 75 million Euros in external research funding annually.

The Excellence Initiative of the German government in 2006 resulted in the foundation of the Hausdorff Center for Mathematics as one of the seventeen national Clusters of Excellence that were part of the initiative and the expansion of the already existing Bonn Graduate School of Economics (BGSE). The Excellence Initiative also resulted in the founding of the Bonn-Cologne Graduate School of Physics and Astronomy (an honors Masters and PhD program, jointly with the University of Cologne). Bethe Center for Theoretical Physics was founded in the November 2008, to foster closer interaction between mathematicians and theoretical physicists at Bonn. The center also arranges for regular visitors and seminars (on topics including String theory, Nuclear physics, Condensed matter etc.).

Rankings

[edit]| University rankings | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overall – Global & National | ||||||||||

| ||||||||||

| By subject – Global & National | ||||||||||

| ||||||||||

In the QS World University Rankings for 2024, the university was positioned 239th globally and 14th nationally.[43] Additionally, the university was ranked significantly higher in the Times Higher Education World University Rankings, taking the 91st place worldwide and the 6th position within the country for the year 2023.[44] Moreover, the university's highest ranking was achieved in the Academic Ranking of World Universities, where it was ranked 67th globally and 4th nationally in 2023.[45]

According to the QS rankings for Mathematics in 2023, it sits at 39th globally and is the leading institution nationally.[46] The ARWU's 2022 Mathematics rankings further bolster this reputation, placing the university 15th in the world and maintaining its first-place national standing.[47]

|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Strategic Partner Universities

[edit]The University of Bonn maintains a variety of relationships with renowned higher education institutions from around the globe.[49] In addition to the numerous research collaborations of its scholars, institutes and faculties, the University of Bonn has a cross-faculty partnership network with over 70 higher education institutions worldwide. In 2023, Bonn built on its strategic partnerships with its existing partner universities and launched a global university network consisting of Emory University, Hebrew University of Jerusalem, University of St Andrews, and Waseda University to foster collaboration in education, research, leadership and innovation.[50]

Africa

[edit]- Ghana: University of Ghana, KNUST.

- Kenya: University of Nairobi.

- Morocco: Mohammed V University.

Asia and Oceania

[edit]- Australia: Australian National University, University of New South Wales, University of Melbourne

- China: Peking University, Beijing Language and Culture University, Beijing Foreign Studies University, Nanjing University, Shanghai Jiao Tong University, Tongji University

- Hong Kong: Chinese University of Hong Kong, University of Hong Kong

- Japan: Keio University, Rikkyo University, Sophia University, University of Tsukuba, Kyoto University, Waseda University, University of Tokyo

- Singapore: National University of Singapore

- South Korea: Korea University, Seoul National University, Sogang University

- Taiwan: National Chengchi University, National Taiwan University, Tamkang University

Europe

[edit]- Czechia: Charles University.

- France: Collège de France, Paris Sciences et Lettres University, Paris-Saclay University, Sorbonne University, University of Strasbourg, University of Toulouse

- Italy: University of Florence.

- Luxembourg: University of Luxembourg.

- Netherlands: Wageningen University & Research.

- Poland: Cardinal Stefan Wyszyński University in Warsaw, Warsaw University of Life Sciences, University of Warsaw, University of Wrocław.

- Spain: Autonomous University of Barcelona, University of Barcelona, University of León, University of Salamanca.

- Switzerland: University of Basel.

- United Kingdom: University of St Andrews, University of Warwick, University of Oxford.

North and South America

[edit]- Brazil: Pontifical Catholic University of Rio de Janeiro, Federal University of Rio de Janeiro

- Chile: University of Talca, Pontifical Catholic University of Chile, University of Chile

- Canada: University of British Columbia, University of Northern British Columbia, University of Ottawa, University of Toronto, McGill University, York University

- Mexico: Meritorious Autonomous University of Puebla

- United States of America: Emory University, Kalamazoo College, Louisiana State University, Ohio State University, Stony Brook University, University of California, Berkeley, University of Florida, University of Kansas, University of Missouri–St. Louis, University of New Mexico, University of Southern Mississippi, University of Mississippi, University of Tennessee, University of Wisconsin–Madison, Washington State University

Middle East

[edit]- Afghanistan: Kabul University.

- Israel: Hebrew University of Jerusalem, Technion, Reichman University, Weizmann Institute of Science.

Regional Networks

[edit]- ABCD-J: RWTH Aachen, University of Cologne, Heinrich Heine University Düsseldorf, Forschungszentrum Jülich

- Bonn-Frankfurt-Mainz: Goethe University Frankfurt, University of Mainz

Subject Specific

[edit]Bonn has close ties to other universities through the following international research networks:

- GlobalMathNetwork: École Normale Supérieure, New York University, Kyoto University, Peking University, University of Warwick, Berkeley, Princeton University[22]

- European Doctoral Programme in Quantitative Economics: Pompeu Fabra University, European University Institute, London School of Economics, KU Leuven, HEC Paris, Tel Aviv University

- TAKeOFF: LMU Munich, KNUST, Tanzania Institute for Medical Research, University of Buea

- Agricultural Innovation: LMU Munich, University of Hohenheim, FARA, AGRODEP

- European Culture and Identity: Sorbonne University, University of Florence, University of Toulouse, University of St Andrews, University of Salamanca, University of Warsaw, University of Freiburg, Sofia University, University of California, Irvine

- UN-Bonn-Tokyo: United Nations University

Notable people

[edit]To date, eleven Nobel Prizes and five Fields Medals have been awarded to faculty and alumni of the Rheinische Friedrich-Wilhelms-Universität Bonn:

- Nobel Prize:

- Emil Fischer, alumni: chemistry, 1902

- Jacobus Henricus van 't Hoff, alumni: chemistry, 1901

- Harald zur Hausen, alumni: physiology and medicine, 2008

- Walter Rudolf Hess, faculty member: physiology and medicine, 1949

- Reinhard Selten, faculty member: economics, 1994

- Wolfgang Paul, faculty member: physics, 1989

- Luigi Pirandello, alumni: literature, 1934

- Otto Wallach, faculty member: chemistry, 1910

- Paul Johann Ludwig von Heyse, alumni: literature, 1910

- Philipp Lenard, faculty member: physics, 1905

- Reinhard Genzel, alumni: physics, 2020

- Fields Medal:

- Gerd Faltings, 1986

- Maxim Kontsevich, 1998

- Gregori Margulis, 1978

- Peter Scholze, 2018

- Maryna Viazovska, 2022

Some of the numerous well-known faculty members and alumni of the University of Bonn:

- In Humanities:

-

Konrad Adenauer was Chancellor of Germany from 1949 to 1963

-

Ernst Moritz Arndt

Historian, writer, poet and one of the founders of 19th century movement for German unification -

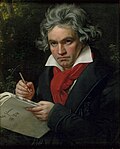

Ludwig van Beethoven

Composer and pianist -

Max Bruch

Composer and conductor -

Franz Boas

Anthropologist and a pioneer of modern anthropology -

Ludwig Erhard

The second Chancellor of (West) Germany from 1963 to 1966 -

Walter Eucken

Economist of the Freiburg school, father of ordoliberalism and developer of the concept of social market economy -

Frederick III

German Emperor -

Joseph Goebbels

Nazi politician and Reich Minister of Propaganda of Nazi Germany -

Jürgen Habermas

Philosopher and sociologist -

Heinrich Heine

Poet, writer and literary critic -

Sheik-Umarr Mikailu Jah

Surgeon & Politician -

Oskar Lafontaine

Served as Minister-President of Saarland, as Germanys Minister of Finance, as party leader of the SPD and later of The Left -

Nobel Prize-winning novelist Thomas Mann

-

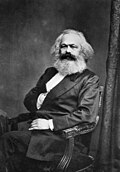

Karl Marx

Philosopher, economist, historian, sociologist, political theorist, journalist and socialist revolutionary -

Friedrich Nietzsche

Philosopher, cultural critic, composer, poet, and philologist -

Thilo Sarrazin

Politician and writer of controversial books about Muslim immigrants in Germany -

Robert Schuman

Statesman and one of the founding fathers of the European Union -

Joseph Schumpeter

Political economist -

Carl Schurz

German revolutionary and an American statesman, journalist, reformer and 13th United States Secretary of the Interior -

Ferdinand Tönnies

Sociologist, economist and philosopher -

Guido Westerwelle

Foreign Minister of Germany, Vice Chancellor of Germany from 2009 to 2011 and first openly gay person to hold any of these positions -

Wilhelm II of Germany

German Emperor

- In Natural Sciences:

-

Friedrich Wilhelm August Argelander

Astronomer -

Constantin Carathéodory

Mathematician -

Peter Gustav Lejeune Dirichlet

Mathematician -

Gerd Faltings

Mathematician -

Emil Fischer

Organic Chemist -

Reinhard Genzel

Astrophysicist -

Felix Hausdorff

Mathematician -

Harald zur Hausen

Virologist -

Heinrich Hertz

Physicist -

Friedrich Hirzebruch

Mathematician -

Eduard Heine

Mathematician -

Walter Rudolf Hess

Physiologist -

August Kekulé

Organic chemist -

Jacobus Henricus van 't Hoff

Physical and Organic Chemist -

Felix Klein

Mathematician -

Maxim Kontsevich

Mathematical Physicist -

Wolfgang Krull

Mathematician -

Philipp Lenard

Physicist -

Harald Lesch

Physicist, astronomer, natural philosopher, author, and television presenter -

Justus von Liebig

Founder of organic chemistry -

Maria von Linden

Bacteriologist and zoologist -

Rudolf Lipschitz

Mathematician -

Jacob Lüroth

Mathematician and Discoverer of the t-Distribution -

Grigory Margulis

Mathematician -

Hermann Minkowski

Mathematician and Physicist -

Wolfgang Paul

Physicist -

Carl Adam Petri

Computer Scientist and Mathematician -

Julius Plücker

Mathematician and Experimental Physicist -

Peter Scholze

Mathematician -

Arnold Schönhage

Computer Scientist and Mathematician -

Issai Schur

Mathematician -

Otto Toeplitz

Mathematician -

Maryna Viazovska

Mathematician -

Otto Wallach

Organic Chemist -

Karl Weierstrass

Mathematician

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Anderson, Peter John (1907). Record of the Celebration of the Quatercentenary of the University of Aberdeen: From 25th to 28th September, 1906. Aberdeen, United Kingdom: Aberdeen University Press (University of Aberdeen). ISBN 9781363625079.

{{cite book}}: ISBN / Date incompatibility (help) - ^ "Zahlen und Fakten — Universität Bonn". www.uni-bonn.de.

- ^ a b c d "University of Bonn at a glance". University of Bonn. Retrieved 3 June 2017.

- ^ "Clusters of Excellence". Universität Bonn. Retrieved 25 March 2022.

- ^ Johann Friedrich Wilhelm Koch: Die Preussischen Universitäten, vol. 1, Berlin: Posen und Bromberg: 1839, pg. 176.

- ^ Becker, Thomas P. (May 2007). "Geschichte der Rheinischen Friedrich-Wilhelms-Universität". Archived from the original on 9 June 2007. Retrieved 8 February 2008.

- ^ Haus der Geschichte der Bundesrepublik Deutschland. "Weg der Demokratie – Path of Democracy". Retrieved 8 February 2008.

- ^ Universitäts-und Landesbibliothek Bonn (October 2003). "Geschichte der ULB Bonn". Archived from the original on 27 November 2007. Retrieved 8 February 2008.

- ^ Universitätsklinikum Bonn. "Homepage of the University Hospital Bonn". Retrieved 8 February 2008.

- ^ University of Bonn (January 2008). "Official Homepage of the Akademisches Kunstmuseum". Archived from the original on 10 February 2008. Retrieved 8 February 2008.

- ^ Egyptian Museum of the University of Bonn (September 2006). "Official Homepage of the Egyptian Museum". Archived from the original on 24 November 2007. Retrieved 8 February 2008.

- ^ Arithmeum. "Official Homepage of the Arithmeum". Archived from the original on 18 February 2008. Retrieved 8 February 2008.

- ^ University of Bonn. "Museums and Academic Collections". Archived from the original on 18 January 2008. Retrieved 8 February 2008.

- ^ Botanic Garden of the University of Bonn. "Official Homepage of the Botanic Garden". Archived from the original on 16 December 2013. Retrieved 8 February 2008.

- ^ "Das Mineralogische Museum". uni-bonn.de. Uni Bonn. Archived from the original on 5 May 2019. Retrieved 8 July 2012.

- ^ Institute of Paleontology. "Geschichte des Museums und des Gebäudes". Archived from the original on 26 January 2008. Retrieved 8 February 2008.

- ^ University Hospital. "Horst-Stoeckel-Museum für die Geschichte der Anästhesiologie". Archived from the original on 19 April 2015. Retrieved 8 February 2008.

- ^ Zoologisches Forschungsmuseum Alexander Koenig. "Official Homepage of the Museum Koenig". Archived from the original on 28 September 2011. Retrieved 8 February 2008.

- ^ "Faculties". University of Bonn. Archived from the original on 3 February 2017. Retrieved 4 February 2018.

- ^ "BIGS - Land and Food — Landwirtschaftliche Fakultät". www.lf.uni-bonn.de. Retrieved 27 March 2022.

- ^ Thomas P. Becker: Geschichte der Rheinischen Friedrich-Wilhelms-Universität. (Online) Archived 21 October 2014 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ a b "Bonn International Graduate School of Mathematics. Promoting the future of excellent research - PDF Free Download". docplayer.net. Retrieved 4 April 2022.

- ^ "Fachgruppe Informatik. Institut – Über uns". www.informatik.uni-bonn.de. Retrieved 18 September 2019.

- ^ "Institut für Informatik". Archived from the original on 17 March 2012. Retrieved 27 March 2022., informatik.uni-bonn.de, retrieved 10 May 2012.

- ^ "Attraktive Lernumgebung: Informatik bezieht Neubau in Poppelsdorf — Universität Bonn". Retrieved 17 September 2019.[permanent dead link]

- ^ Fachgruppe Physik-Astronomie: Institute Archived 28 September 2022 at the Wayback Machine Retrieved 30 July 2015.

- ^ "BCTP :: Home :: Mission". www.bctp.uni-bonn.de. Retrieved 11 February 2023.

- ^ "Kunststiftung NRW richtet Thomas-Kling-Poetikdozentur an der Universität Bonn ein". Kunststiftung NRW. Retrieved 4 April 2015.

- ^ Ludger Kühnhardt, Tilman Mayer, ed. (2017), Bonner Enzyklopädie der Globalität (in German), Wiesbaden: Springer VS, (1627 Seiten pages), ISBN 978-3-658-13818-9, retrieved 25 March 2017

- ^ "Global Exchange Program". Universität Bonn (in German). Retrieved 7 April 2022.

- ^ "Mobility-Online Portal". mobility-international.uni-bonn.de. Retrieved 7 April 2022.

- ^ "Seven key properties on the three campuses of Poppelsdorf, Endenich and City". Universität Bonn. Retrieved 7 April 2022.

- ^ "THE UNIVERSITY OF BONN 2025 INTERNATIONALIZATION STRATEGY" (PDF). University of Bonn Rectorate. 2020. Archived (PDF) from the original on 9 October 2022.

- ^ F.J. Dölger-Institut. "Official Homepage of the F.J. Dölger-Institut". Archived from the original on 14 March 2009. Retrieved 8 February 2008.

- ^ Research Institute for Discrete Mathematics. "Research of the Institute for Discrete Mathematics". Retrieved 8 February 2008.

- ^ Karnbach, Bodo (October 2000). "Chip-Design mit diskreter Mathematik – Weltweit erfolgreiche Kooperation verlängert". Archived from the original on 30 September 2007. Retrieved 8 February 2008.

- ^ Bethe Center for Theoretical Physics. "Official Homepage of the BCTP". Retrieved 25 March 2009.

- ^ German Reference Center for Ethics in the Life Science. "Official Homepage of the DRZE". Retrieved 8 February 2008.

- ^ Center for European Integration Studies. "Official Homepage of the ZEI". Retrieved 8 February 2008.

- ^ Center for Development Research. "Official Homepage of the ZEF". Archived from the original on 27 February 2008. Retrieved 8 February 2008.

- ^ "Center for Economics and Neuroscience – Zentrale wissenschaftliche Einrichtung der Universität Bonn". www.cens.uni-bonn.de.

- ^ http://www3.uni-bonn.de/Pressemitteilungen/304-2011 Press release of the University of Bonn concerning the official welcoming of the center

- ^ a b "QS World University Rankings 2024". QS World University Rankings. Retrieved 16 July 2023.

- ^ a b "World University Rankings 2024". Times Higher Education World University Rankings. 27 September 2023. Retrieved 27 September 2023.

- ^ a b "2023 Academic Ranking of World Universities". Academic Ranking of World Universities. Retrieved 15 August 2023.

- ^ a b c "QS World University Rankings by Subject 2022". QS World University Rankings. 23 March 2023.

- ^ a b c "ShanghaiRanking's Global Ranking of Academic Subjects 2022". Academic Ranking of World Universities. Retrieved 2 August 2023.

- ^ "World University Rankings by subject". Times Higher Education World University Rankings. Retrieved 27 October 2022.

- ^ "University Partnerships". Universität Bonn. Retrieved 25 March 2022.

- ^ "Global Network Officially Launched". Universität Bonn. 10 May 2023.

External links

[edit]- Official website

- University Library Archived 3 February 2017 at the Wayback Machine

University of Bonn

View on GrokipediaHistory

Foundation and Early Development (1818–1914)

The University of Bonn was established on 18 October 1818 by King Frederick William III of Prussia via a royal decree creating the Rhein-Universität, aimed at bolstering Prussian governance and education in the Rhineland territories acquired after the Napoleonic Wars and formalized by the Congress of Vienna in 1815.[9] [10] This initiative sought to replace the University of Cologne, dissolved in 1798 during French occupation, thereby restoring local access to higher learning while aligning the region with Prussian administrative priorities.[10] Instruction commenced in 1819, with the Electoral Palace serving as the initial site for lectures across the medical and other disciplines.[11] The founding structure included five faculties: Catholic Theology, Protestant Theology, Law, Medicine, and Philosophy, a configuration unique for its separate theological departments to accommodate the Rhineland's mixed religious demographics under Prussian rule.[4] [12] These faculties reflected the Humboldtian ideal of integrating teaching and research, though implementation emphasized practical state service alongside scholarly pursuits.[13] The university initially operated without the founder's name, receiving its full designation as Rheinische Friedrich-Wilhelms-Universität in 1840 under Frederick William IV, who honored his deceased father posthumously.[13] Throughout the 19th century, the institution expanded amid Germany's unification and industrialization, incorporating solemn annual opening ceremonies from its inception to mark the academic year.[13] Facilities grew beyond the Electoral Palace, with sites like Poppelsdorf Palace adapted for natural sciences and agriculture by the late 1800s, supporting burgeoning fields vital to regional economy. Early enrollment was modest, but by the Wilhelmine era preceding 1914, the university had solidified as a key Prussian academic center, fostering advancements in theology, law, and emerging sciences through state funding and scholarly migration.[11] This period laid the groundwork for Bonn's reputation in rigorous inquiry, though constrained by monarchical oversight and limited autonomy compared to older German universities.[14]World War I, Weimar Republic, and Nazi Era (1914–1945)

During World War I, the University of Bonn, like other German institutions of higher education, saw its growth halted as male students volunteered en masse for military service, leading to a sharp decline in enrollment.[15] [16] The main building of the university served as a war kitchen to support the war effort, which later evolved into the institution's first student cafeteria in 1919.[17] In the Weimar Republic period, the university faced financial constraints due to reduced government funding amid post-war economic instability, prompting efforts to secure support from private industry.[15] Student political activity was prominent, reflecting broader tensions in German academia, though specific enrollment figures for Bonn remain sparsely documented.[18] The Nazi era brought profound changes following the regime's seizure of power in 1933. The Law for the Restoration of the Professional Civil Service, enacted on April 7, 1933, mandated the dismissal of Jewish and politically unreliable academics, affecting the University of Bonn as part of the nationwide "Aryanization" of universities. Mathematician Otto Toeplitz, who had held a professorship at Bonn since 1928, retained his lecturing position initially in 1933 but was dismissed from his chair in 1935 despite exemptions for certain veterans; he subsequently emigrated to Mandatory Palestine.[19] Similarly, Felix Hausdorff, a prominent mathematician and professor at Bonn from 1930, was forced into retirement in 1935 at age 66, despite his conversion to Protestantism and status as a World War I veteran; facing escalating persecution, he and his wife committed suicide in 1942 to avoid deportation.[20] The university's administration adapted to Nazi oversight, with student organizations like the National Socialist German Students' League gaining control and many remaining professors signing a vow of allegiance to Hitler. Later revelations highlighted pre-1933 Nazi affiliations among some faculty, including future rectors.[21] As World War II progressed, the university endured Allied bombings, sustaining heavy damage to facilities. Operations ceased in late 1944, and Bonn was captured by U.S. forces on March 8–9, 1945, marking the end of the Nazi period for the institution. [22]Post-World War II Reconstruction (1945–1989)

The University of Bonn sustained severe damage from Allied air raids, particularly the bombing on October 18, 1944, which destroyed nearly all medical clinics and much of the infrastructure on its 126th founding anniversary.[23] Despite the devastation, the institution reopened ceremonially on November 17, 1945, just six months after the war's end and one year after the major attack, as one of the first universities in the British occupation zone.[24] Heinrich Matthias Konen served as the inaugural post-war president, admitting 1,549 students by December 10, 1945, amid efforts to resume academic life in provisional facilities.[22] Denazification processes were implemented under Allied oversight, targeting faculty and staff with Nazi affiliations, though implementation proved inconsistent, with some former regime members retaining positions due to personnel shortages and pragmatic needs for continuity.[8] The British authorities prioritized re-education toward democratic values, but systemic challenges, including incomplete purges, persisted, as evidenced by later controversies over instructors' wartime roles surfacing in the 1960s.[21] Physical reconstruction advanced concurrently, with the main building—the former Electoral Palace—restored post-1945, incorporating 1950s-era elements to replace war damage.[25] In 1949, the university hospital relocated from the bombed city center to the Venusberg district on Bonn's western outskirts, enhancing medical facilities amid the city's designation as West Germany's provisional capital. The 1950s and 1960s saw expansion during the Wirtschaftswunder economic boom, with new constructions supporting growing enrollment and research; by the mid-1960s, many buildings dated to this period, reflecting modernization efforts.[26] Student activism peaked in the late 1960s, mirroring national protests against perceived authoritarian remnants and Vietnam War involvement, influencing campus governance debates at Bonn.[8] Through the 1970s and 1980s, the university solidified its status as a research powerhouse, benefiting from federal funding as the capital's academic hub, though infrastructure strains emerged from rapid postwar growth.[27]Reunification Era and Modern Expansion (1990–Present)

Following German reunification on October 3, 1990, the University of Bonn navigated the shift of the federal capital to Berlin while benefiting from Bonn's redesignation as a federal city hosting international institutions and research entities, which bolstered its role in cross-border academic collaborations. The institution maintained steady operations amid national economic integration, with early 1990s developments including expanded computing infrastructure through connections to the national WIN science network, facilitating growth in data-intensive research.[28] Student enrollment, which stood at approximately 25,000 in the early 1990s, expanded to over 35,000 by the 2020s, reflecting broader trends in German higher education access and internationalization, with international students comprising about 12% of the total by the mid-2010s.[29] The late 1990s and 2000s marked infrastructural and programmatic expansions, notably through participation in the federal Excellence Initiative launched in 2005 to elevate top-tier research. In 2006, Bonn established the Hausdorff Center for Mathematics as Germany's inaugural Cluster of Excellence in the field, funded under this initiative to foster advanced studies in pure and applied mathematics, including geometry, analysis, and probability, drawing global talent and hosting thematic programs.[30] This center, named after alumnus Felix Hausdorff, integrated with the Mathematics Institute to enhance interdisciplinary applications, such as in physics and data science, contributing to Bonn's reputation for producing Fields Medal recipients, including professor Peter Scholze in 2018. Complementary growth included new facilities like the Arithmeum museum for computing history and expanded agricultural research tied to the Poppelsdorf campus. ![Hausdorff Center.jpg][float-right] In the 2010s onward, Bonn solidified its status as a research powerhouse via the successor Excellence Strategy. Designated a University of Excellence in 2019—one of only 11 in Germany—it secured six Clusters of Excellence, outpacing all peers in number, covering domains from economic governance (ECONtribute) to plant sciences (PhenoRobotics) and immunology (ImmunoSensation2).[31] By May 2025, all six were renewed for the 2026–2030 period, with two additional clusters approved, totaling eight and injecting over €100 million in funding to drive innovations like AI-driven crop phenotyping and dependency studies in global history.[32] These initiatives have elevated Bonn's global rankings, reaching 89th worldwide in the Times Higher Education assessment by 2024, while prioritizing empirical advancements over administrative expansion, with research output evidenced by sustained third-party grants from the German Research Foundation exceeding €200 million annually.[7] This era underscores causal drivers of success: targeted federal investment in merit-based clusters yielding measurable outputs in publications and patents, rather than diffuse institutional growth.Campus and Facilities

Main Campuses and Architectural Features

The University of Bonn operates without a centralized campus, distributing its facilities across multiple sites in Bonn, primarily in the city center, Poppelsdorf, Endenich, and Castell districts.[27] This decentralized structure integrates historic architecture with modern constructions, reflecting the institution's evolution since its 1818 foundation.[25] In the city center, the main building occupies the former Electoral Palace (Kurfürstliches Schloss), a Baroque Residenzschloss originally constructed as the residence of Elector Ernst of Bavaria in the late 16th century, rebuilt after fires and wars, and donated to the university in 1818 by King Friedrich Wilhelm III of Prussia.[25] The structure features a four-wing complex with corner towers on the Hofgarten wing, spanning 26,000 square meters as the largest among the university's approximately 200 buildings in Bonn.[25] It houses the Faculty of Arts, both theology faculties, and administrative offices, forming a historic ensemble with the adjacent Hofgarten and Poppelsdorfer Allee avenue.[27] A comprehensive renovation began in 2024, involving temporary relocations due to the building's listed status.[25] The Poppelsdorf campus, located in the Poppelsdorf district, spans over 15 hectares and focuses on natural sciences, featuring Poppelsdorf Palace, a Baroque structure built between 1715 and 1740 as a pleasure palace for the archbishops and electors of Cologne.[27] [33] Modern additions include the Rotation Building, a laboratory and seminar facility under construction with 8,300 square meters for interdisciplinary use, and the Teaching and Research Forum, completed in 2017 with 5,600 square meters housing natural sciences institutes and lecture halls.[27] The Endenich campus in the Endenich district accommodates the Faculty of Mathematics and Natural Sciences, alongside spaces for technology transfer units and startups, with plans for a new pharmacy building to support research and innovation.[27] [34] The Castell district hosts additional facilities, contributing to the university's dispersed yet interconnected presence in Bonn.[27]Library and Archival Resources

The Bonn University and State Library (Universitäts- und Landesbibliothek Bonn, ULB Bonn) serves as the central lending and archival library for the University of Bonn, supporting information services for university members and the broader Rhineland region.[35] Its holdings encompass 2,357,000 books and journal volumes, alongside 4,103 current printed journals and access to 29,426 licensed electronic journals.[36] The library maintains 58 affiliated libraries across the university, contributing to a collective total of approximately 5,000,000 volumes.[3] Special collections within the ULB include medieval and modern manuscripts, bequests, autographs, music manuscripts, and other specialist materials, forming a core resource for historical and cultural research.[37] Historical holdings feature autographs, portraits, war letters, seals, deeds, certificates, and coats of arms, with ongoing digitization efforts expanding online access to these materials.[38] [39] As North Rhine-Westphalia's state library for the Cologne district, it archives regional publications and participates in projects like the NS-Raubgut initiative, which systematically examines books seized during Nazi persecution.[37] The University Archive, distinct from the ULB, preserves the institution's historical records in approximately 4,000 linear shelf meters, supplemented by a 10,000-volume reference library.[40] These resources document the university's nearly 200-year history, including administrative files, personnel records, and institutional developments, accessible for scholarly research on site.[41] Digital initiatives, such as the bonndoc server for university publications and research data management services, further enhance archival accessibility.[42]University Hospital and Medical Facilities