Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Heraldry

View on Wikipedia

Heraldry (also known as armory) is a discipline relating to the design, display, study and transmission of armorial bearings. A full heraldic achievement may include a coat of arms on a shield, helmet and crest, together with accompanying devices, such as supporters, badges, heraldic banners and mottoes.[1] Heraldic achievements are formally described in a blazon.[2]

Although the use of various devices to signify individuals and groups goes back to antiquity, both the form and use of such devices varied widely, as the concept of regular, hereditary designs, constituting the distinguishing feature of heraldry, did not develop until the High Middle Ages.[3] It is often claimed that the use of helmets with face guards during this period made it difficult to recognize one's commanders in the field when large armies gathered together for extended periods, necessitating the development of heraldry as a symbolic language, but there is little support for this view.[3][4]

The perceived beauty and pageantry of heraldic designs allowed them to survive the gradual abandonment of armour on the battlefield during the seventeenth century. Heraldry has been described poetically as "the handmaid of history",[5] "the shorthand of history",[6] and "the floral border in the garden of history".[7] In modern times, individuals, public and private organizations, corporations, cities, towns, regions, and other entities use heraldry and its conventions to symbolize their heritage, achievements, and aspirations.[8]

Related disciplines include vexillology (the study of flags), genealogy, and the studies of ceremony and rank.[9][10]

History

[edit]Precursors

[edit]Various symbols have been used to represent individuals or groups for thousands of years. The earliest representations of distinct persons and regions in Egyptian art show the use of standards topped with the images or symbols of various gods, and the names of kings appear upon emblems known as serekhs, representing the king's palace, and usually topped with a falcon representing the god Horus, of whom the king was regarded as the earthly incarnation. Similar emblems and devices are found in ancient Mesopotamian art of the same period, and the precursors of heraldic beasts such as the griffin can also be found.[3] In the Bible, the Book of Numbers refers to the standards and ensigns of the children of Israel, who were commanded to gather beneath these emblems and declare their pedigrees.[11] The Greek and Latin writers frequently describe the shields and symbols of various heroes,[12] and units of the Roman army were sometimes identified by distinctive markings on their shields.[13] At least one pre-historic European object, the Nebra sky disc, is also thought to serve as a heraldic precursor.[14]

Until the nineteenth century, it was common for heraldic writers to cite examples such as these, and metaphorical symbols such as the "Lion of Judah" or "Eagle of the Caesars", as evidence of the antiquity of heraldry itself; and to infer that the great figures of ancient history bore arms representing their noble status and descent. The Book of Saint Albans, compiled in 1486, declares that Christ himself was a gentleman of coat armour.[15] These claims are now regarded as the fantasy of medieval heralds, as there is no evidence of a distinctive symbolic language akin to that of heraldry during this early period; nor do many of the shields described in antiquity bear a close resemblance to those of medieval heraldry; nor is there any evidence that specific symbols or designs were passed down from one generation to the next, representing a particular person or line of descent.[16]

The medieval heralds also devised arms for various knights and lords from history and literature. Notable examples are the toads attributed to Pharamond, the cross and martlets of Edward the Confessor, and the various arms attributed to the Nine Worthies and the Knights of the Round Table. These too are readily dismissed as fanciful inventions, rather than evidence of the antiquity of heraldry.

-

Reverse of the Narmer Palette, circa 3100 BC. The top row depicts four men carrying standards. Directly above them is a serekh containing the name of the king, Narmer.

-

Fresco depicting a shield of a type common in Mycenaean Greece.

-

Vase with Greek soldiers in armor, circa 550 BC.

-

A reconstruction of a shield that would have been carried by a Roman Legionary.

-

Shields from the "Magister Militum Praesentalis II". From the Notitia Dignitatum, a medieval copy of a Late Roman register of military commands. However, it is likely the art on the shields are made to fit the time/age and not from the original.[citation needed]

-

The death of King Harold, from the Bayeux Tapestry. The shields look heraldic, but do not seem to have been personal or hereditary emblems.

Origins of modern heraldry

[edit]

The development of the modern heraldic language cannot be attributed to a single individual, time, or place. Although certain designs that are now considered heraldic were evidently in use during the eleventh century, most accounts and depictions of shields up to the beginning of the twelfth century contain little or no evidence of their heraldic character. For example, the Bayeux Tapestry, illustrating the Norman invasion of England in 1066, and probably commissioned about 1077, when the cathedral of Bayeux was rebuilt,[i] depicts a number of shields of various shapes and designs, many of which are plain, while others are decorated with dragons, crosses, or other typically heraldic figures. Yet no individual is depicted twice bearing the same arms, nor are any of the descendants of the various persons depicted known to have borne devices resembling those in the tapestry.[17][18]

Similarly, an account of the French knights at the court of the Byzantine emperor Alexius I at the beginning of the twelfth century describes their shields of polished metal, devoid of heraldic design. A Spanish manuscript from 1109 describes both plain and decorated shields, none of which appears to have been heraldic.[19] The Abbey of St. Denis contained a window commemorating the knights who embarked on the Second Crusade in 1147, and was probably made soon after the event; but Montfaucon's illustration of the window before it was destroyed shows no heraldic design on any of the shields.[18][20]

In England, from the time of the Norman conquest, official documents had to be sealed. Beginning in the twelfth century, seals assumed a distinctly heraldic character; a number of seals dating from between 1135 and 1155 appear to show the adoption of heraldic devices in England, France, Germany, Spain, and Italy.[21] A notable example of an early armorial seal is attached to a charter granted by Philip I, Count of Flanders, in 1164. Seals from the latter part of the eleventh and early twelfth centuries show no evidence of heraldic symbolism, but by the end of the twelfth century, seals are uniformly heraldic in nature.[19][22]

One of the earliest known examples of armory as it subsequently came to be practiced can be seen on the tomb of Geoffrey Plantagenet, Count of Anjou, who died in 1151.[23] An enamel, probably commissioned by Geoffrey's widow between 1155 and 1160, depicts him carrying a blue shield decorated with six golden lions rampant.[ii] He wears a blue helmet adorned with another lion, and his cloak is lined in vair. A medieval chronicle states that Geoffrey was given a shield of this description when he was knighted by his father-in-law, Henry I, in 1128; but this account probably dates to about 1175.[24][25]

The earlier heraldic writers attributed the lions of England to William the Conqueror, but the earliest evidence of the association of lions with the English crown is a seal bearing two lions passant, used by the future King John during the lifetime of his father, Henry II, who died in 1189.[26][27] Since Henry was the son of Geoffrey Plantagenet, it seems reasonable to suppose that the adoption of lions as an heraldic emblem by Henry or his sons might have been inspired by Geoffrey's shield. John's elder brother, Richard the Lionheart, who succeeded his father on the throne, is believed to have been the first to have borne the arms of three lions passant-guardant, still the arms of England, having earlier used two lions rampant combatant, which arms may also have belonged to his father.[28] Richard is also credited with having originated the English crest of a lion statant (now statant-guardant).[27][29]

The origins of heraldry are sometimes associated with the Crusades, a series of military campaigns undertaken by Christian armies from 1096 to 1487, with the goal of reconquering Jerusalem and other former Byzantine territories captured by Muslim forces during the seventh century. While there is no evidence that heraldic art originated in the course of the Crusades, there is no reason to doubt that the gathering of large armies, drawn from across Europe for a united cause, would have encouraged the adoption of armorial bearings as a means of identifying one's commanders in the field, or that it helped disseminate the principles of armory across Europe. At least two distinctive features of heraldry are generally accepted as products of the crusaders: the surcoat, an outer garment worn over the armor to protect the wearer from the heat of the sun, was often decorated with the same devices that appeared on a knight's shield. It is from this garment that the phrase "coat of arms" is derived.[30] Also the lambrequin, or mantling, that depends from the helmet and frames the shield in modern heraldry, began as a practical covering for the helmet and the back of the neck during the Crusades, serving much the same function as the surcoat. Its slashed or scalloped edge, today rendered as billowing flourishes, is thought to have originated from hard wearing in the field, or as a means of deadening a sword blow and perhaps entangling the attacker's weapon.[31]

Heralds and heraldic authorities

[edit]The spread of armorial bearings across Europe gave rise to a new occupation: the herald, originally a type of messenger employed by noblemen, assumed the responsibility of learning and knowing the rank, pedigree, and heraldic devices of various knights and lords, as well as the rules governing the design and description, or blazoning of arms, and the precedence of their bearers.[32] As early as the late thirteenth century, certain heralds in the employ of monarchs were given the title "King of Heralds", which eventually became "King of Arms."[32]

In the earliest period, arms were assumed by their bearers without any need for heraldic authority. However, by the middle of the fourteenth century, the principle that only a single individual was entitled to bear a particular coat of arms was generally accepted, and disputes over the ownership of arms seems to have led to gradual establishment of heraldic authorities to regulate their use. The earliest known work of heraldic jurisprudence, De Insigniis et Armis, was written about 1350 by Bartolus de Saxoferrato, a professor of law at the University of Padua.[33][34] The most celebrated armorial dispute in English heraldry is that of Scrope v Grosvenor (1390), in which two different men claimed the right to bear azure, a bend or.[35] The continued proliferation of arms, and the number of disputes arising from different men assuming the same arms, led Henry V to issue a proclamation in 1419, forbidding all those who had not borne arms at the Battle of Agincourt from assuming arms, except by inheritance or a grant from the crown.[35][36]

Beginning in the reign of Henry VIII of England, the English Kings of Arms were commanded to make visitations, in which they traveled about the country, recording arms borne under proper authority, and requiring those who bore arms without authority either to obtain authority for them, or cease their use. Arms borne improperly were to be taken down and defaced. The first such visitation began in 1530, and the last was carried out in 1700, although no new commissions to carry out visitations were made after the accession of William III in 1689.[35][37] There is little evidence that Scottish heralds ever went on visitations.

In 1484, during the reign of Richard III, the various heralds employed by the crown were incorporated into England's College of Arms, through which all new grants of arms would eventually be issued.[38][39] The college currently consists of three Kings of Arms, assisted by six Heralds, and four Pursuivants, or junior officers of arms, all under the authority of the Earl Marshal; but all of the arms granted by the college are granted by the authority of the crown.[40] In Scotland Court of the Lord Lyon King of Arms oversees the heraldry, and holds court sessions which are an official part of Scotland's court system. Similar bodies regulate the granting of arms in other monarchies and several members of the Commonwealth of Nations, but in most other countries there is no heraldic authority, and no law preventing anyone from assuming whatever arms they please, provided that they do not infringe upon the arms of another.[39]

Later uses and developments

[edit]Although heraldry originated from military necessity, it soon found itself at home in the pageantry of the medieval tournament. The opportunity for knights and lords to display their heraldic bearings in a competitive medium led to further refinements, such as the development of elaborate tournament helms, and further popularised the art of heraldry throughout Europe. Prominent burghers and corporations, including many cities and towns, assumed or obtained grants of arms, with only nominal military associations.[41] Heraldic devices were depicted in various contexts, such as religious and funerary art, and in using a wide variety of media, including stonework, carved wood, enamel, stained glass, and embroidery.[42]

As the rise of firearms rendered the mounted knight increasingly irrelevant during the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, and the tournament faded into history, the military character of heraldry gave way to its use as a decorative art. Freed from the limitations of actual shields and the need for arms to be easily distinguished in combat, heraldic artists designed increasingly elaborate achievements, culminating in the development of "landscape heraldry", incorporating realistic depictions of landscapes, during the latter part of the eighteenth and early part of the nineteenth century. These fell out of fashion during the mid-nineteenth century, when a renewed interest in the history of armory led to the re-evaluation of earlier designs, and a new appreciation for the medieval origins of the art.[43][44] In particular, a late use of heraldic imagery has been in patriotic commemorations and nationalistic propaganda during the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries.[45][46][47] Since the late nineteenth century, heraldry has focused on the use of varied lines of partition and little-used ordinaries to produce new and unique designs.[48]

Heraldic achievement

[edit]Elements of an achievement

[edit]| Part of a series on |

| Heraldic achievement |

|---|

| External devices in addition to the central coat of arms |

|

|

A heraldic achievement consists of a shield of arms, the coat of arms, or simply coat, together with all of its accompanying elements, such as a crest, supporters, and other heraldic embellishments. The term "coat of arms" technically refers to the shield of arms itself, but the phrase is commonly used to refer to the entire achievement. The one indispensable element of a coat of arms is the shield; many ancient coats of arms consist of nothing else, but no achievement or armorial bearings exists without a coat of arms.[49]

From a very early date, illustrations of arms were frequently embellished with helmets placed above the shields. These in turn came to be decorated with fan-shaped or sculptural crests, often incorporating elements from the shield of arms; as well as a wreath or torse, or sometimes a coronet, from which depended the lambrequin or mantling. To these elements, modern heraldry often adds a motto displayed on a ribbon, typically below the shield. The helmet is borne of right, and forms no part of a grant of arms; it may be assumed without authority by anyone entitled to bear arms, together with mantling and whatever motto the armiger may desire. The crest, however, together with the torse or coronet from which it arises, must be granted or confirmed by the relevant heraldic authority.[49]

If the bearer is entitled to the ribbon, collar, or badge of a knightly order, it may encircle or depend from the shield. Some arms, particularly those of the nobility, are further embellished with supporters, heraldic figures standing alongside or behind the shield; often these stand on a compartment, typically a mound of earth and grass, on which other badges, symbols, or heraldic banners may be displayed. The most elaborate achievements sometimes display the entire coat of arms beneath a pavilion, an embellished tent or canopy of the type associated with the medieval tournament,[49] though this is only very rarely found in English or Scots achievements.

Shield

[edit]The primary element of a heraldic achievement is the shield, or escutcheon, upon which the coat of arms is depicted.[iii] All of the other elements of an achievement are designed to decorate and complement these arms, but only the shield of arms is required.[50][51][52] The shape of the shield, like many other details, is normally left to the discretion of the heraldic artist,[iv] and many different shapes have prevailed during different periods of heraldic design, and in different parts of Europe.[50][57][58][59]

One shape alone is normally reserved for a specific purpose: the lozenge, a diamond-shaped escutcheon, was traditionally used to display the arms of women, on the grounds that shields, as implements of war, were inappropriate for this purpose.[50][60][61] This distinction was not always strictly adhered to, and a general exception was usually made for sovereigns, whose arms represented an entire nation. Sometimes an oval shield, or cartouche, was substituted for the lozenge; this shape was also widely used for the arms of clerics in French, Spanish, and Italian heraldry, although it was never reserved for their use.[50][58] In recent years, the use of the cartouche for women's arms has become general in Scottish heraldry, while both Scottish and Irish authorities have permitted a traditional shield under certain circumstances, and in Canadian heraldry the shield is now regularly granted.[62]

The whole surface of the escutcheon is termed the field, which may be plain, consisting of a single tincture, or divided into multiple sections of differing tinctures by various lines of partition; and any part of the field may be semé, or powdered with small charges.[63] The edges and adjacent parts of the escutcheon are used to identify the placement of various heraldic charges; the upper edge, and the corresponding upper third of the shield, are referred to as the chief; the lower part is the base. The sides of the shield are known as the dexter and sinister flanks, although these terms are based on the point of view of the bearer of the shield, who would be standing behind it; to the observer, and in all heraldic illustration, the dexter is on the left side, and the sinister on the right.[64][65][66]

The placement of various charges may also refer to a number of specific points: nine in number according to some authorities, but eleven according to others. The three most important are fess point, located in the visual center of the shield;[v] the honour point, located midway between fess point and the chief; and the nombril point, located midway between fess point and the base.[64][65][66] The other points include dexter chief, center chief, and sinister chief, running along the upper part of the shield from left to right, above the honour point; dexter flank and sinister flank, on the sides approximately level with fess point; and dexter base, middle base, and sinister base along the lower part of the shield, below the nombril point.[64][65]

Tinctures

[edit]

One of the most distinctive qualities of heraldry is the use of a limited palette of colours and patterns, usually referred to as tinctures. These are divided into three categories, known as metals, colours, and furs.[vi][67]

The metals are or and argent, representing gold and silver, respectively, although in practice they are usually depicted as yellow and white. Five colours are universally recognized: gules, or red; sable, or black; azure, or blue; vert, or green; and purpure, or purple; and most heraldic authorities also admit two additional colours, known as sanguine or murrey, a dark red or mulberry colour between gules and purpure, and tenné, an orange or dark yellow to brown colour. These last two are quite rare, and are often referred to as stains, from the belief that they were used to represent some dishonourable act, although in fact there is no evidence that this use existed outside of fanciful heraldic writers.[68] Perhaps owing to the realization that there is really no such thing as a stain in genuine heraldry, as well as the desire to create new and unique designs, the use of these colours for general purposes has become accepted in the twentieth and twenty-first centuries.[vii][40] Occasionally one meets with other colours, particularly in continental heraldry, although they are not generally regarded among the standard heraldic colours. Among these are cendrée, or ash-colour; brunâtre, or brown; bleu-céleste or bleu de ciel, sky blue; amaranth or columbine, a bright violet-red or pink colour; and carnation, commonly used to represent flesh in French heraldry.[69] A more recent addition is the use of copper as a metal in one or two Canadian coats of arms.

There are two basic types of heraldic fur, known as ermine and vair, but over the course of centuries each has developed a number of variations. Ermine represents the fur of the stoat, a type of weasel, in its white winter coat, when it is called an ermine. It consists of a white, or occasionally silver field, powdered with black figures known as ermine spots, representing the black tip of the animal's tail. Ermine was traditionally used to line the cloaks and caps of the nobility. The shape of the heraldic ermine spot has varied considerably over time, and nowadays is typically drawn as an arrowhead surmounted by three small dots, but older forms may be employed at the artist's discretion. When the field is sable and the ermine spots argent, the same pattern is termed ermines; when the field is or rather than argent, the fur is termed erminois; and when the field is sable and the ermine spots or, it is termed pean.[70][71]

Vair represents the winter coat of the red squirrel, which is blue-grey on top and white underneath. To form the linings of cloaks, the pelts were sewn together, forming an undulating, bell-shaped pattern, with interlocking light and dark rows. The heraldic fur is depicted with interlocking rows of argent and azure, although the shape of the pelts, usually referred to as "vair bells", is usually left to the artist's discretion. In the modern form, the bells are depicted with straight lines and sharp angles, and meet only at points; in the older, undulating pattern, now known as vair ondé or vair ancien, the bells of each tincture are curved and joined at the base. There is no fixed rule as to whether the argent bells should be at the top or the bottom of each row. At one time vair commonly came in three sizes, and this distinction is sometimes encountered in continental heraldry; if the field contains fewer than four rows, the fur is termed gros vair or beffroi; if of six or more, it is menu-vair, or miniver.[72][73]

A common variation is counter-vair, in which alternating rows are reversed, so that the bases of the vair bells of each tincture are joined to those of the same tincture in the row above or below. When the rows are arranged so that the bells of each tincture form vertical columns, it is termed vair in pale; in continental heraldry one may encounter vair in bend, which is similar to vair in pale, but diagonal. When alternating rows are reversed as in counter-vair, and then displaced by half the width of one bell, it is termed vair in point, or wave-vair. A form peculiar to German heraldry is alternate vair, in which each vair bell is divided in half vertically, with half argent and half azure.[72] All of these variations can also be depicted in the form known as potent, in which the shape of the vair bell is replaced by a T-shaped figure, known as a potent from its resemblance to a crutch. Although it is really just a variation of vair, it is frequently treated as a separate fur.[74]

When the same patterns are composed of tinctures other than argent and azure, they are termed vairé or vairy of those tinctures, rather than vair; potenté of other colours may also be found. Usually vairé will consist of one metal and one colour, but ermine or one of its variations may also be used, and vairé of four tinctures, usually two metals and two colours, is sometimes found.[75]

Three additional furs are sometimes encountered in continental heraldry; in French and Italian heraldry one meets with plumeté or plumetty, in which the field appears to be covered with feathers, and papelonné, in which it is decorated with scales. In German heraldry one may encounter kursch, or vair bellies, depicted as brown and furry; all of these probably originated as variations of vair.[76]

Considerable latitude is given to the heraldic artist in depicting the heraldic tinctures; there is no fixed shade or hue to any of them.[viii]

Whenever an object is depicted as it appears in nature, rather than in one or more of the heraldic tinctures, it is termed proper, or the colour of nature. This does not seem to have been done in the earliest heraldry, but examples are known from at least the seventeenth century. While there can be no objection to the occasional depiction of objects in this manner, the overuse of charges in their natural colours is often cited as indicative of bad heraldic practice. The practice of landscape heraldry, which flourished in the latter part of the eighteenth and early part of the nineteenth century, made extensive use of non-heraldic colours.[77]

One of the most important conventions of heraldry is the so-called "rule of tincture". To provide for contrast and visibility, metals should never be placed on metals, and colours should never be placed on colours. This rule does not apply to charges which cross a division of the field, which is partly metal and partly colour; nor, strictly speaking, does it prevent a field from consisting of two metals or two colours, although this is unusual. Furs are considered amphibious, and neither metal nor colour; but in practice ermine and erminois are usually treated as metals, while ermines and pean are treated as colours. This rule is strictly adhered to in British armory, with only rare exceptions; although generally observed in continental heraldry, it is not adhered to quite as strictly. Arms which violate this rule are sometimes known as "puzzle arms", of which the most famous example is the arms of the Kingdom of Jerusalem, consisting of gold crosses on a silver field.[78][79]

Variations of the field

[edit]The field of a shield, or less often a charge or crest, is sometimes made up of a pattern of colours, or variation. A pattern of horizontal (barwise) stripes, for example, is called barry, while a pattern of vertical (palewise) stripes is called paly. A pattern of diagonal stripes may be called bendy or bendy sinister, depending on the direction of the stripes. Other variations include chevrony, gyronny and chequy. Wave shaped stripes are termed undy. For further variations, these are sometimes combined to produce patterns of barry-bendy, paly-bendy, lozengy and fusilly. Semés, or patterns of repeated charges, are also considered variations of the field.[80] The Rule of tincture applies to all semés and variations of the field.

Divisions of the field

[edit]

The field of a shield in heraldry can be divided into more than one tincture, as can the various heraldic charges. Many coats of arms consist simply of a division of the field into two contrasting tinctures. These are considered divisions of a shield, so the rule of tincture can be ignored. For example, a shield divided azure and gules would be perfectly acceptable. A line of partition may be straight or it may be varied. The variations of partition lines can be wavy, indented, embattled, engrailed, nebuly, or made into myriad other forms; see Line (heraldry).[81]

Ordinaries

[edit]In the early days of heraldry, very simple bold rectilinear shapes were painted on shields. These could be easily recognized at a long distance and could be easily remembered. They therefore served the main purpose of heraldry: identification.[82] As more complicated shields came into use, these bold shapes were set apart in a separate class as the "honourable ordinaries". They act as charges and are always written first in blazon. Unless otherwise specified they extend to the edges of the field. Though ordinaries are not easily defined, they are generally described as including the cross, the fess, the pale, the bend, the chevron, the saltire, and the pall.[83]

There is a separate class of charges called sub-ordinaries which are of a geometrical shape subordinate to the ordinary. According to Friar, they are distinguished by their order in blazon. The sub-ordinaries include the inescutcheon, the orle, the tressure, the double tressure, the bordure, the chief, the canton, the label, and flaunches.[84]

Ordinaries may appear in parallel series, in which case blazons in English give them different names such as pallets, bars, bendlets, and chevronels. French blazon makes no such distinction between these diminutives and the ordinaries when borne singly. Unless otherwise specified an ordinary is drawn with straight lines, but each may be indented, embattled, wavy, engrailed, or otherwise have their lines varied.[85]

Charges

[edit]A charge is any object or figure placed on a heraldic shield or on any other object of an armorial composition.[86] Any object found in nature or technology may appear as a heraldic charge in armory. Charges can be animals, objects, or geometric shapes. Apart from the ordinaries, the most frequent charges are the cross – with its hundreds of variations – and the lion and eagle. Other common animals are bears, stags, wild boars, martlets, wolves and fish. Dragons, bats, unicorns, griffins, and other monsters appear as charges and as supporters.

Animals are found in various stereotyped positions or attitudes. Quadrupeds can often be found rampant (standing on the left hind foot). Another frequent position is passant, or walking, like the lions of the coat of arms of England. Eagles are almost always shown with their wings spread, or displayed. A pair of wings conjoined is called a vol.

In English heraldry the crescent, mullet, martlet, annulet, fleur-de-lis, and rose may be added to a shield to distinguish cadet branches of a family from the senior line. These cadency marks are usually shown smaller than normal charges, but it still does not follow that a shield containing such a charge belongs to a cadet branch. All of these charges occur frequently in basic undifferenced coats of arms.[87]

Marshalling

[edit]

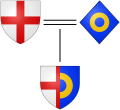

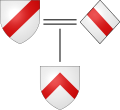

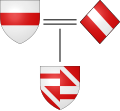

To marshal two or more coats of arms is to combine them in one shield, to express inheritance, claims to property, or the occupation of an office. This can be done in a number of ways, of which the simplest is impalement: dividing the field per pale and putting one whole coat in each half. Impalement replaced the earlier dimidiation – combining the dexter half of one coat with the sinister half of another – because dimidiation can create ambiguity between, for example, a bend and a chevron. "Dexter" (from Latin dextra, "right") means to the right from the viewpoint of the bearer of the arms and "sinister" (from Latin sinistra, "left") means to the bearer's left. The dexter side is considered the side of greatest honour (see also dexter and sinister).

A more versatile method is quartering, division of the field by both vertical and horizontal lines. This practice originated in Spain (Castile and León) after the 13th century.[88] As the name implies, the usual number of divisions is four, but the principle has been extended to very large numbers of "quarters".

Quarters are numbered from the dexter chief (the corner nearest to the right shoulder of a man standing behind the shield), proceeding across the top row, and then across the next row and so on. When three coats are quartered, the first is repeated as the fourth; when only two coats are quartered, the second is also repeated as the third. The quarters of a personal coat of arms correspond to the ancestors from whom the bearer has inherited arms, normally in the same sequence as if the pedigree were laid out with the father's father's ... father (to as many generations as necessary) on the extreme left and the mother's mother's...mother on the extreme right. A few lineages have accumulated hundreds of quarters, though such a number is usually displayed only in documentary contexts.[89] The Scottish and Spanish traditions resist allowing more than four quarters, preferring to subdivide one or more "grand quarters" into sub-quarters as needed.

The third common mode of marshalling is with an inescutcheon, a small shield placed in front of the main shield. In Britain this is most often an "escutcheon of pretence" indicating, in the arms of a married couple, that the wife is an heraldic heiress (i.e., she inherits a coat of arms because she has no brothers). In continental Europe an inescutcheon (sometimes called a "heart shield") usually carries the ancestral arms of a monarch or noble whose domains are represented by the quarters of the main shield.

In German heraldry, animate charges in combined coats usually turn to face the centre of the composition.

-

Dimidiation

-

Dimidiation (worst case)

-

Impalement

-

Impalement (worst case)

-

Escutcheon of pretence

-

Quartering

Helm and crest

[edit]

In English the word "crest" is commonly (but erroneously) used to refer to an entire heraldic achievement of armorial bearings. The technical use of the heraldic term crest refers to just one component of a complete achievement. The crest rests on top of a helmet which itself rests on the most important part of the achievement: the shield.

The modern crest has grown out of the three-dimensional figure placed on the top of the mounted knights' helms as a further means of identification. In most heraldic traditions, a woman does not display a crest, though this tradition is being relaxed in some heraldic jurisdictions, and the stall plate of Lady Marion Fraser in the Thistle Chapel in St Giles, Edinburgh, shows her coat on a lozenge but with helmet, crest, and motto.

The crest is usually found on a wreath of twisted cloth and sometimes within a coronet. Crest-coronets are generally simpler than coronets of rank, but several specialized forms exist; for example, in Canada, descendants of the United Empire Loyalists are entitled to use a Loyalist military coronet (for descendants of members of Loyalist regiments) or Loyalist civil coronet (for others).

When the helm and crest are shown, they are usually accompanied by a mantling. This was originally a cloth worn over the back of the helmet as partial protection against heating by sunlight. Today it takes the form of a stylized cloak hanging from the helmet.[90] Typically in British heraldry, the outer surface of the mantling is of the principal colour in the shield and the inner surface is of the principal metal, though peers in the United Kingdom use standard colourings (Gules doubled Argent - Red/White) regardless of rank or the colourings of their arms. The mantling is sometimes conventionally depicted with a ragged edge, as if damaged in combat, though the edges of most are simply decorated at the emblazoner's discretion.

Clergy often refrain from displaying a helm or crest in their heraldic achievements. Members of the clergy may display appropriate headwear. This often takes the form of a small crowned, wide brimmed hat called a galero with the colours and tassels denoting rank; or, in the case of Papal coats of arms until the inauguration of Pope Benedict XVI in 2005, an elaborate triple crown known as a tiara. Benedict broke with tradition to substitute a mitre in his arms. Orthodox and Presbyterian clergy do sometimes adopt other forms of headgear to ensign their shields. In the Anglican tradition, clergy members may pass crests on to their offspring, but rarely display them on their own shields.

Mottoes

[edit]An armorial motto is a phrase or collection of words intended to describe the motivation or intention of the armigerous person or corporation. This can form a pun on the family name as in Thomas Nevile's motto Ne vile velis. Mottoes are generally changed at will and do not make up an integral part of the armorial achievement. Mottoes can typically be found on a scroll under the shield. In Scottish heraldry, where the motto is granted as part of the blazon, it is usually shown on a scroll above the crest, and may not be changed at will. A motto may be in any language.

Supporters and other insignia

[edit]

Supporters are human or animal figures or, very rarely, inanimate objects, usually placed on either side of a coat of arms as though supporting it. In many traditions, these have acquired strict guidelines for use by certain social classes. On the European continent, there are often fewer restrictions on the use of supporters.[91] In the United Kingdom, only peers of the realm, a few baronets, senior members of orders of knighthood, and some corporate bodies are granted supporters. Often, these can have local significance or a historical link to the armiger.

If the armiger has the title of baron, hereditary knight, or higher, he may display a coronet of rank above the shield. In the United Kingdom, this is shown between the shield and helmet, though it is often above the crest in Continental heraldry.

Another addition that can be made to a coat of arms is the insignia of a baronet or of an order of knighthood. This is usually represented by a collar or similar band surrounding the shield. When the arms of a knight and his wife are shown in one achievement, the insignia of knighthood surround the husband's arms only, and the wife's arms are customarily surrounded by an ornamental garland of leaves for visual balance.[92]

Differencing and cadency

[edit]Since arms pass from parents to offspring, and there is frequently more than one child per couple, it is necessary to distinguish the arms of siblings and extended family members from the original arms as passed on from eldest son to eldest son. Over time several schemes have been used.[93]

Blazon

[edit]To "blazon" arms means to describe them using the formal language of heraldry. This language has its own vocabulary and syntax, or rules governing word order, which becomes essential for comprehension when blazoning a complex coat of arms. The verb comes from the Middle English blasoun, itself a derivative of the French blason meaning "shield". The system of blazoning arms used in English-speaking countries today was developed by heraldic officers in the Middle Ages. The blazon includes a description of the arms contained within the escutcheon or shield, the crest, supporters where present, motto and other insignia. Complex rules, such as the rule of tincture, apply to the physical and artistic form of newly created arms, and a thorough understanding of these rules is essential to the art of heraldry. Though heraldic forms initially were broadly similar across Europe, several national styles had developed by the end of the Middle Ages, and artistic and blazoning styles today range from the very simple to extraordinarily complex.

National styles

[edit]Heraldry emerged across western Europe almost simultaneously in the various countries. Originally, heraldic style was very similar from country to country.[94] Over time, heraldic tradition diverged into four broad styles: German-Nordic, Gallo-British, Latin, and Eastern.[95] In addition, it can be argued that newer national heraldic traditions, such as South African and Canadian heraldry, have emerged in the 20th century.[96]

Germanic heraldries

[edit]German-Nordic heraldry

[edit]

Coats of arms in Germany, the Nordic countries, Estonia, Latvia, the Czech lands and northern Switzerland generally change very little over time. Marks of difference are very rare in this tradition, as are heraldic furs.[98] One of the most striking characteristics of German-Nordic heraldry is the treatment of the crest. Often, the same design is repeated in the shield and the crest. The use of multiple crests is also common.[99] The crest is rarely used separately as in British heraldry, but can sometimes serve as a mark of difference between different branches of a family.[100] Torse is optional.[101] Heraldic courtoisie is observed: that is, charges in a composite shield (or two shields displayed together) usually turn to face the centre.[102]

Coats consisting only of a divided field are somewhat more frequent in Germany than elsewhere.

Dutch heraldry

[edit]The Low Countries were great centres of heraldry in medieval times. One of the famous armorials is the Gelre Armorial or Wapenboek, written between 1370 and 1414. Coats of arms in the Netherlands were not controlled by an official heraldic system like the two in the United Kingdom, nor were they used solely by noble families. Any person could develop and use a coat of arms if they wished to do so, provided they did not usurp someone else's arms, and historically, this right was enshrined in Roman Dutch law.[103] As a result, many merchant families had coats of arms even though they were not members of the nobility. These are sometimes referred to as burgher arms, and it is thought that most arms of this type were adopted while the Netherlands was a republic (1581–1806).[citation needed] This heraldic tradition was also exported to the erstwhile Dutch colonies.[104] Dutch heraldry is characterised by its simple and rather sober style, and in this sense, is closer to its medieval origins than the elaborate styles which developed in other heraldic traditions.[105]

Gallo-British heraldry

[edit]

The use of cadency marks to difference arms within the same family and the use of semy fields are distinctive features of Gallo-British heraldry (in Scotland the most significant mark of cadency being the bordure, the small brisures playing a very minor role). Marks of cadency are mandatory in Scotland, where no two persons can own identical arms at a time. It is common to see heraldic furs used.[98] In the United Kingdom, the style is notably still controlled by royal officers of arms.[106] French heraldry experienced a period of strict rules of construction under Napoleon.[107] English and Scots heraldries make greater use of supporters than other European countries.[99]

Latin heraldry

[edit]

The heraldry of Latin countries, namely southern France, Andorra, Spain, and Italy, and except for northern France (using the Gallo-British style), Portugal (which does use crests), and Romania (using the Eastern European style), is characterized by a lack of crests, and uniquely shaped shields.[98] Portuguese and Spanish heraldry, which together form a larger Iberian tradition of heraldry, occasionally introduce words to the shield of arms, a practice usually avoided in British heraldry. Latin heraldry is known for extensive use of quartering, because of armorial inheritance via the male and the female lines. Moreover, Italian heraldry is dominated by the Roman Catholic Church, featuring many shields and achievements, most bearing some reference to the Church.[108]

Trees are frequent charges in Latin arms. Charged bordures, including bordures inscribed with words, are seen often in Spain.

Eastern European heraldry

[edit]

Eastern European heraldry is in the traditions developed in Eastern Europe and the Balkans, which includes all Slavic countries (except for Czechia, which uses the German-Nordic style), Albania, Hungary, Lithuania and Romania, and excludes Greece, Cyprus and Turkey. Eastern coats of arms are characterized by a pronounced, territorial, clan system—often, entire villages or military groups were granted the same coat of arms irrespective of family relationships. In Poland, nearly six hundred unrelated families are known to bear the same Jastrzębiec coat of arms. Marks of cadency are almost unknown, and shields are generally very simple, with only one charge. Many heraldic shields derive from ancient house marks. At least fifteen per cent of all Hungarian personal arms bear a severed Turk's head, referring to their wars against the Ottoman Empire.[109][110]

Quasi-heraldic emblems

[edit]True heraldry, as now generally understood, has its roots in medieval Europe. However, there have been other historical cultures which have used symbols and emblems to represent families or individuals, and in some cases these symbols have been adopted into Western heraldry. For example, the coat of arms of the Ottoman Empire incorporated the royal tughra as part of its crest, along with such traditional Western heraldic elements as the escutcheon and the compartment.

Greek symbols

[edit]Ancient Greeks were among the first civilizations to use symbols consistently in order to identify a warrior, clan or a state.[111] The first record of a shield blazon is illustrated in Aeschylus' tragedy Seven Against Thebes.

Mon

[edit]Mon (紋), also monshō (紋章), mondokoro (紋所), and kamon (家紋), are Japanese emblems used to decorate and identify an individual or family. While mon is an encompassing term that may refer to any such device, kamon and mondokoro refer specifically to emblems used to identify a family.[further explanation needed] An authoritative mon reference compiles Japan's 241 general categories of mon based on structural resemblance (a single mon may belong to multiple categories), with 5116 distinct individual mon (it is however well acknowledged that there exist lost or obscure mon that are not in this compilation).[112][113]

The devices are similar to the badges and coats of arms in European heraldic tradition, which likewise are used to identify individuals and families. Mon are often referred to as crests in Western literature, another European heraldic device similar to the mon in function.

Japanese helmets (kabuto) also incorporated elements similar to crests, called datemono, which helped identify the wearer while they were concealed by armour. These devices sometimes incorporated mon, and some figures, like Date Masamune, were well known for their helmet designs.

Socialist emblems

[edit]

Communist states often followed a unique style characterized by communist symbolism. Although commonly called coats of arms, most such devices are not actually coats of arms in the traditional heraldic sense and should therefore, in a strict sense, not be called arms at all.[114] Many communist governments purposely diverged from the traditional forms of European heraldry in order to distance themselves from the monarchies that they usually replaced, with actual coats of arms being seen as symbols of the monarchs.

The Soviet Union was the first state to use this type of emblem, beginning at its creation in 1922. The style became more widespread after World War II, when many other communist states were established. Even a few non-socialist states have adopted the style, for various reasons—usually because communists had helped them to gain independence—but also when no apparent connection to a Communist nation exists, such as the emblem of Italy.[114][115] After the fall of the Soviet Union and the other communist states in Eastern Europe in 1989–1991, this style of heraldry was often abandoned for the old heraldic practices, with many new governments reinstating the traditional heraldry that was previously cast aside.

Tamgas

[edit]A tamga or tamgha "stamp, seal" (Mongolian: тамга, Turkic: tamga) is an abstract seal or stamp used by Eurasian nomadic peoples and by cultures influenced by them. The tamga was normally the emblem of a particular tribe, clan or family. They were common among the Eurasian nomads throughout Classical Antiquity and the Middle Ages (including Alans, Mongols, Sarmatians, Scythians and Turkic peoples). Similar "tamga-like" symbols were sometimes also adopted by sedentary peoples adjacent to the Pontic-Caspian steppe both in Eastern Europe and Central Asia,[116] such as the East Slavs, whose ancient royal symbols are sometimes referred to as "tamgas" and have similar appearance.[117]

Unlike European coats of arms, tamgas were not always inherited, and could stand for families or clans (for example, when denoting territory, livestock, or religious items) as well as for specific individuals (such as when used for weapons, or for royal seals). One could also adopt the tamga of one's master or ruler, therefore signifying said master's patronage. Outside of denoting ownership, tamgas also possessed religious significance, and were used as talismans to protect one from curses (it was believed that, as symbols of family, tamgas embodied the power of one's heritage). Tamgas depicted geometric shapes, images of animals, items, or glyphs. As they were usually inscribed using heavy and unwieldy instruments, such as knives or brands, and on different surfaces (meaning that their appearance could vary somewhat), tamgas were always simple and stylised, and needed to be laconic and easily recognisable.[118]

Tughras

[edit]Every sultan of the Ottoman Empire had his own monogram, called the tughra, which served as a royal symbol. A coat of arms in the European heraldic sense was created in the late 19th century. Hampton Court requested from Ottoman Empire the coat of arms to be included in their collection. As the coat of arms had not been previously used in Ottoman Empire, it was designed after this request and the final design was adopted by Sultan Abdul Hamid II on April 17, 1882. It included two flags: the flag of the Ottoman Dynasty, which had a crescent and a star on red base, and the flag of the Islamic Caliph, which had three crescents on a green base.

Ancient Iran

[edit]The word of "arms" in the Pahlavi scripts is 𐭥𐭢𐭱𐭠𐭥 which is read as nišān (Persian: نشان). In Islamic sources there are some references to the existence of nišāns in ancient Iran. It is suggested that the words arms, mon, and nišān are oscillating on a same semantic context as they all satisfy a similar need: Heraldic identification. al-Masudi writes that nišāns (Arabic: شعار) used by Parthians and Sasanians. When al-Masudi talks about Sasanians, he describes their arms as "flags of Persians and their emblems" (رایات الفرس و أعلامهم). In the world of "pahlavans" (پهلوانان) of Iranian national narratives, as same as the world of European knights, each army under the command of a pahlavan from one of the noble families identified by a nišān on its flag. Usually, when the pahlavans were presented in the court of the king of Iran, they were distinguishing each troop from another with a flag which had their lords' nišāns on itself.[119][120]

Modern heraldry

[edit]Today, institutions, companies, and private persons continue using coats of arms as their pictorial identification.[121][122][123][124] In the United Kingdom and Ireland, the English Kings of Arms, Scotland's Lord Lyon King of Arms, and the Chief Herald of Ireland continue making grants of arms.[125] There are heraldic authorities in Canada (Canadian Heraldic Authority),[126] South Africa, Spain, and Sweden that grant or register coats of arms. In South Africa, the right to armorial bearings is also determined by Roman Dutch law, due to its origins as a 17th-century colony of the Netherlands.[127]

Heraldic societies abound in Africa, Asia, Australasia, the Americas and Europe. Heraldry aficionados participate in the Society for Creative Anachronism, medieval revivals, micronations and other related projects. Modern armigers use heraldry to express ancestral and personal heritage as well as professional, academic, civic, and national pride.[128] Little is left of class identification in modern heraldry, where the emphasis is more than ever on expression of identity.[129]

Heraldry continues to build on its rich tradition in academia, government, guilds and professional associations, religious institutions, and the military. Nations and their subdivisions – provinces, states, counties, cities, etc. – continue to build on the traditions of civic heraldry. The Roman Catholic Church, Anglican churches, and other religious institutions maintain the traditions of ecclesiastical heraldry for clergy, religious orders, and schools.

Many of these institutions have begun to employ blazons representing modern objects. For example, some heraldic symbols issued by the United States Army Institute of Heraldry incorporate symbols such as guns, airplanes, or locomotives. Some scientific institutions incorporate symbols of modern science such as the atom or particular scientific instruments. The arms of the United Kingdom Atomic Energy Authority uses traditional heraldic symbols to depict the harnessing of atomic power.[130] Locations with strong associations to particular industries may incorporate associated symbols. The coat of arms of Stenungsund Municipality in Sweden incorporates a hydrocarbon molecule, alluding to the historical significance of the petrochemical industry in the region.

Heraldry in countries with heraldic authorities continues to be regulated generally by laws granting rights to arms and recognizing possession of arms as well as protecting against their misuse. Countries without heraldic authorities usually treat coats of arms as creative property in the manner of logos, offering protection under copyright laws. This is the case in Nigeria, where most of the components of its heraldic system are otherwise unregulated.

-

1977 arms with a hydrocarbon molecule

-

2022 arms of Castagneto, showing chestnuts (castagne)

-

Arms of the US 52nd Air Defense Artillery Regiment, with a locomotive as a crest

See also

[edit]- Emblematic – Pictorial image that epitomizes a concept or that represents a person

- Heraldic societies

- Sigillography – Study of seals

- Totem pole – Monumental carvings by Indigenous peoples of the Pacific Northwest

Footnotes

[edit]- ^ This was undertaken by Odo, Bishop of Bayeux, and half-brother of William I, whose conquest of England is commemorated by the tapestry.

- ^ Only four lions are visible in this depiction, in which the shield is shown in profile, but judging from their position, there must have been six; the tomb of Geoffrey's grandson, William Longspée, shows him bearing an apparently identical shield, but on this all six lions are at least partly visible.

- ^ The term "coat of arms" is sometimes used to refer to the entire achievement, of which the shield is the central part.

- ^ There are exceptions to this rule, in which the shape of the escutcheon is specified in the blazon; for example, the arms of Nunavut,[53] and the former Republic of Bophuthatswana;[54] in the United States, the arms of North Dakota use an escutcheon in the shape of a stone arrowhead,[55] while the arms of Connecticut require a rococo shield;[56] the Scottish Public Register specifies an oval escutcheon for the Lanarkshire Master Plumbers' and Domestic Engineers' Association, and a square shield for the Anglo Leasing organisation.

- ^ Because most shields are widest at the chief, and narrow to a point at the base, fess point is usually slightly higher than the midpoint.

- ^ Technically, the word tincture applies specifically to the colours, rather than to the metals or the furs; but for lack of another term including all three, it is regularly used in this extended sense.

- ^ For instance, the arms of Lewes Old Grammar School, granted October 25, 2012: "Murrey within an Orle of eight Crosses crosslet Argent a Lion rampant Or holding in the forepaws a Book bound Azure the spine and the edges of the pages Gold" and those of Woolf, granted October 2, 2015: "Murrey a Snow Wolf's Head erased proper on a Chief Argent a Boar's Head coped at the neck between two Fleurs de Lys Azure."

- ^ "There are no fixed shades for heraldic colours. If the official description of a coat of arms gives its tinctures as Gules (red), Azure (blue) and Argent (white or silver) then, as long as the blue is not too light and the red not too orange, purple or pink, it is up to the artist to decide which particular shades they think are appropriate."[40]

References

[edit]- ^ Fox-Davies (1909), pp. 1, 57–59

- ^ "Heraldry - Symbols, Blazon, Armorial | Britannica". www.britannica.com. Retrieved 2025-07-23.

- ^ a b c Fox-Davies (1909), pp. 1–18

- ^ John Brooke-Little, An Heraldic Alphabet, Macdonald, London (1973), p. 2.

- ^ Boutell (1890), p. 5

- ^ Fox-Davies (1909), p. v

- ^ Iain Moncreiffe of that Ilk & Pottinger, Simple Heraldry, Thomas Nelson (1953).

- ^ Fox-Davies (1909), pp. 19–26

- ^ Fox-Davies (1909), p. 1; Friar (1987), p. 183

- ^ Webster's Third New International Dictionary, C. & G. Merriam Company, Cambridge, Massachusetts (1960).

- ^ Numbers, i. 2, 18, 52; ii. 2, 34; quoted by William Sloane Sloane-Evans, in A Grammar of British Heraldry (London, 1854), p. ix; quoted by Fox-Davies (1909), pp. 6.

- ^ Fox-Davies (1909), pp. 6–10

- ^ Notitia Dignitatum, Bodleian Library

- ^ Eiland, Murray (2003). "Pre-heraldry on the Sangerhausen Disc". The Armiger's News. 25 (2): 1, 9 – via academia.edu.

- ^ Fox-Davies (1909), p. 6

- ^ Fox-Davies (1909), pp. 11–16

- ^ Woodward & Burnett (1892), pp. 29–31

- ^ a b Fox-Davies (1909), pp. 14–16

- ^ a b Woodward & Burnett (1892), p. 26

- ^ Woodward & Burnett (1892), p. 31

- ^ Woodcock & Robinson (1988), p. 1

- ^ Wagner (1946), p. 8

- ^ Fox-Davies (1909), pp. 62

- ^ C. A. Stothard, Monumental Effigies of Great Britain (1817) pl. 2, illus. in Wagner (1946), pl. I

- ^ Pastoureau (1997), p. 18

- ^ Woodward & Burnett (1892), p. 32

- ^ a b Fox-Davies (1909), pp. 173–174

- ^ Pastoureau (1997), p. 59

- ^ Woodward & Burnett (1892), p. 37

- ^ Fox-Davies (1909), pp. 17–18

- ^ Fox-Davies (1909), pp. 17–18, 383

- ^ a b Fox-Davies (1909), pp. 27–29

- ^ De Insigniis et Armis

- ^ George Squibb, "The Law of Arms in England", in The Coat of Arms vol. II, no. 15 (Spring 1953), p. 244.

- ^ a b c Fox-Davies (1909), pp. 21–22

- ^ Woodward & Burnett (1892), p. 35–36

- ^ Julian Franklyn, Shield and Crest: An Account of the Art and Science of Heraldry, MacGibbon & Kee, London (1960), p. 386.

- ^ Fox-Davies (1909), p. 38

- ^ a b Pastoureau (1997), pp. 39–41

- ^ a b c College of Arms official website, accessed 3 March 2016.

- ^ Gwynn-Jones (1998), pp. 18–20

- ^ Neubecker (1976), pp. 253–258

- ^ Fox-Davies (1909), pp. 87–88

- ^ Gwynn-Jones (1998), pp. 110–112

- ^ Eiland, Murray (2018). "Heraldry on American Patriotic Postcards". The Armiger's News. 41 (1): 1–3 – via academia.edu.

- ^ Eiland, Murray (2019). "Heraldry on German Patriotic Postcards". The Armiger's News. 41 (2): 1–5 – via academia.edu.

- ^ Eiland, Murray (2010). "Heraldry on German Notgeld". The Armiger's News. 23 (3): 1–3, 12 – via academia.edu.

- ^ Gwynn-Jones (1998), pp. 113–121

- ^ a b c Fox-Davies (1909), pp. 57–59

- ^ a b c d Fox-Davies (1909), pp. 57, 60–61

- ^ Boutell (1890), p. 6

- ^ William Whitmore, The Elements of Heraldry, Weathervane Books, New York (1968), p. 9.

- ^ "About the Flag and Coat of Arms". Government of Nunavut. Archived from the original on 2006-04-27. Retrieved October 19, 2006.

- ^ Hartemink R. 1996. South African Civic Heraldry-Bophuthatswana. Ralf Hartemink, The Netherlands. Accessed October 19, 2006. Available at NGW.nl

- ^ "US Heraldic Registry". US Heraldic Registry. Retrieved 2012-06-19.

- ^ "American Heraldry Society - Arms of Connecticut". Americanheraldry.org. Archived from the original on 2012-07-22. Retrieved 2012-06-19.

- ^ Boutell (1890), pp. 6–7

- ^ a b Woodward & Burnett (1892), pp. 54–58

- ^ Neubecker (1976), pp. 72–77

- ^ Boutell (1890), p. 9

- ^ Slater (2003), p. 56

- ^ Slater (2003), p. 231

- ^ Fox-Davies (1909), pp. 89, 96–98

- ^ a b c Boutell (1890), p. 8

- ^ a b c Woodward & Burnett (1892), p. 59–60

- ^ a b Fox-Davies (1909), pp. 104–105

- ^ Fox-Davies (1909), p. 70

- ^ Fox-Davies (1909), pp. 70–74

- ^ Woodward & Burnett (1892), p. 61–62; Fox-Davies (1909), pp. 74

- ^ Woodward & Burnett (1892), p. 63

- ^ Fox-Davies (1909), pp. 77–79

- ^ a b Fox-Davies (1909), pp. 79–83

- ^ Innes of Learney (1978), p. 28

- ^ Fox-Davies (1909), pp. 84–85

- ^ Fox-Davies (1909), pp. 80–85

- ^ Fox-Davies (1909), pp. 83–85

- ^ Fox-Davies (1909), pp. 75, 87–88

- ^ Fox-Davies (1909), pp. 85–87

- ^ Bruno Heim, Or and Argent, Gerrards Cross, Buckingham (1994).

- ^ Fox-Davies (1909), pp. 101

- ^ Stephen Friar and John Ferguson. Basic Heraldry. (W.W. Norton & Company, New York: 1993), 148.

- ^ von Volborth (1981), p. 18

- ^ Friar (1987), p. 259

- ^ Friar (1987), p. 330

- ^ Woodcock & Robinson (1988), p. 60

- ^ Boutell (1890), p. 311

- ^ Moncreiffe, Iain; Pottinger, Don (1953). Simple Heraldry, Cheerfully Illustrated. London: Thomas Nelson and Sons. p. 20. OCLC 1119559413.

- ^ Woodcock & Robinson (1988), p. 14

- ^ Edmundas Rimša. Heraldry Past to Present. (Versus Aureus, Vilnius: 2005), 38.

- ^ Gwynn-Jones (1998), p. 124

- ^ Neubecker (1976), pp. 186

- ^ Julian Franklyn. Shield and Crest. (MacGibbon & Kee, London: 1960), 358.

- ^ "Differencing a.k.a. Cadency". Journalists' & Authors' Guide to Heraldry and Titles. Baronage.co.uk. Archived from the original on Aug 5, 2012. Retrieved 2012-06-19.

- ^ Davies, T. R. (Spring 1976). "Did National Heraldry Exist?". The Coat of Arms NS II (97): 16.

- ^ von Warnstedt (1970), p. 128

- ^ Alan Beddoe, revised by Strome Galloway. Beddoe's Canadian Heraldry. (Mika Publishing Company, Belleville: 1981).

- ^ Jussi Iltanen (2013). Suomen kuntavaakunat. Kommunvapnen i Finland (in Finnish). Helsinki: Karttakeskus. pp. 133–134. ISBN 978-952-266-092-3.

- ^ a b c von Warnstedt (1970), p. 129

- ^ a b Woodcock & Robinson (1988), p. 15

- ^ Neubecker (1976), p. 158

- ^ Pinches (1994), p. 82

- ^ von Volborth (1981), p. 88

- ^ de Boo, J. A. (1977). Familiewapens, oud en nieuw. Een inleiding tot de Familieheraldiek (in Dutch). The Hague: Centraal Bureau voor Genealogie. OCLC 63382927.

- ^ McMillan, Joseph. "Theodore Roosevelt and Franklin Delano Roosevelt, 26th and 32nd Presidents of the United States". American Heraldry Society.

- ^ Cornelius Pama Heraldiek in Suid-Afrika. (Balkema, Cape Town: 1956).

- ^ Carl-Alexander von Volborth. Heraldry of the World. (Blandford Press, Dorset: 1979), 192.

- ^ Woodcock & Robinson (1988), p. 21

- ^ Woodcock & Robinson (1988), pp. 24–30

- ^ von Warnstedt (1970), pp. 129–30

- ^ Woodcock & Robinson (1988), pp. 28–32

- ^ Claus, Patricia (6 May 2022). "Aincent Greek Shields Struck Fear Into Enemy". Greek Reporter. Greek Reporter. Retrieved 10 March 2023.

- ^ 日本の家紋大全. 梧桐書院. 2004. ISBN 434003102X.

- ^ Some 6939 mon are listed here Archived 2016-10-28 at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ a b von Volborth (1981), p. 11

- ^ von Volborth, Carl-Alexander (1972). Alverdens heraldik i farver (in Danish). Editor and translator from English to Danish: Sven Tito Achen. Copenhagen: Politikens Forlag. p. 158. ISBN 87-567-1685-0.

- ^ Ottfried Neubecker. Heraldik. Orbis, 2002; Brook 154; Franklin and Shepard 120-121; Pritsak 78-79.

- ^ Noonan, Thomas Schaub (2006). Pre-modern Russia and Its World: Essays in Honor of Thomas S. Noonan. Otto Harrassowitz Verlag. ISBN 9783447054256. Retrieved 2016-06-13.

- ^ ТАМГА (к функции знака). В.С. Ольховский (Историко-археологический альманах, No 7, Армавир, 2001, стр. 75-86)

- ^ Kalani, Reza. 2022. Indo-Parthians and the Rise of Sasanians, Tahouri Publishers, Tehran, pp85,88

- ^ Kalani, Reza. 2017. Multiple Identification Alternatives for Two Sassanid Equestrians on Fīrūzābād I Relief: A Heraldic Approach, Tarikh Negar Monthly, Tehran, p3: note.6

- ^ Eiland, Murray (2014). "Cigar box heraldry". The Armiger's News. 36 (1): 1–4. Archived from the original on Jan 17, 2023 – via academia.edu.

- ^ Eiland, Murray (2015). "Heraldry on Crate Labels". The Armiger's News. 37 (3): 1–4. Archived from the original on Aug 18, 2023 – via academia.edu.

- ^ Eiland, Murray (2018). "Elvis Presley's Coat of Arms". The Armiger's News. 41 (1): 6. Archived from the original on Aug 19, 2023 – via academia.edu.

- ^ Eiland, Murray (2012). "Postcard from the Supreme Court, London". The Armiger's News. 34 (3): 2–4. Archived from the original on Aug 18, 2023 – via academia.edu.

- ^ See the College of Arms newsletter for quarterly samplings of English grants and the Chief Herald of Ireland's webpage Archived 2006-10-04 at the Wayback Machine for recent Irish grants.

- ^ See the Public Register of Arms, Flags and Badges of Canada.

- ^ Cornelius Pama. Heraldry of South African families: coats of arms/crests/ancestry. (Balkema, Cape Town: 1972)

- ^ Eiland, Murray (2018). "Gathering the clans in California". The Armiger's News. 40 (1): 1–6 – via academia.edu.

- ^ Slater (2003), p. 238

- ^ Child, Heather (1976-01-01). Heraldic Design: A Handbook for Students. Genealogical Publishing Com. ISBN 9780806300719.

Bibliography

[edit]- Boutell, Charles (1890). Aveling, S. T. (ed.). Heraldry, Ancient and Modern: Including Boutell's Heraldry. London: Frederick Warne. OCLC 6102523 – via Internet Archive.

- Burke, Bernard (1967). The General Armory of England, Scotland, Ireland and Wales; Comprising a Registry of Armorial Bearings from the Earliest to the Present Time. Baltimore: Genealogical Publishing.

- Dennys, Rodney (1975). The Heraldic Imagination. New York: Clarkson N. Potter.

- Elvins, Mark Turnham (1988). Cardinals and Heraldry. London: Buckland Publications.

- Fairbairn, James (1986). Fairbairn's Crests of the Families of Great Britain & Ireland. New York: Bonanza Books.

- Fox-Davies, Arthur Charles (1904). The Art of Heraldry: An Encyclopedia of Armory. London: T.C. & E.C. Jack – via Internet Archive.

- Fox-Davies, Arthur Charles (1909). A Complete Guide to Heraldry. London: T.C. & E.C. Jack. LCCN 09023803 – via Internet Archive.

- Franklyn, Julian (1968). Heraldry. Cranbury, NJ: A.S. Barnes and Company. ISBN 9780498066832.

- Friar, Stephen, ed. (1987). A Dictionary of Heraldry. New York: Harmony Books. ISBN 9780517566657.

- Gwynn-Jones, Peter (1998). The Art of Heraldry: Origins, Symbols, and Designs. London: Parkgate Books. ISBN 9780760710821.

- Hart, Vaughan. 'London's Standard: Christopher Wren and the Heraldry of the Monument', in RES: Journal of Anthropology and Aesthetics, vol.73/74, Autumn 2020, pp. 325–39

- Humphery-Smith, Cecil (1973). General Armory Two. London: Tabard Press. ISBN 9780806305837.

- Innes of Learney, Thomas (1978). Innes of Edingight, Malcolm (ed.). Scots Heraldry (3rd ed.). London: Johnston & Bacon. ISBN 9780717942282.

- Le Févre, Jean (1971). Pinches, Rosemary; Wood, Anthony (eds.). A European Armorial: An Armorial of Knights of the Golden Fleece and 15th Century Europe. London: Heraldry Today. ISBN 9780900455131.

- Louda, Jiří; Maclagan, Michael (1981). Heraldry of the Royal Families of Europe. New York: Clarkson Potter.

- Mackenzie of Rosehaugh, George (1680). Scotland's Herauldrie: the Science of Herauldrie treated as a part of the Civil law and Law of Nations. Edinburgh: Heir of Andrew Anderson.

- Moncreiffe, Iain; Pottinger, Don (1953). Simple Heraldry - Cheerfully Illustrated. London and Edinburgh: Thomas Nelson and Sons.

- Neubecker, Ottfried (1976). Heraldry: Sources, Symbols and Meaning. Maidenhead, England: McGraw-Hill.

- Nisbet, Alexander (1984). A system of Heraldry. Edinburgh: T & A Constable.

- Parker, James (1970). A Glossary of Terms Used in Heraldry. Newton Abbot: David & Charles.

- Pastoureau, Michel (1997). Heraldry: An Introduction to a Noble Tradition. "Abrams Discoveries" series. New York: Harry N. Abrams.

- Paul, James Balfour (1903). An Ordinary of Arms Contained in the Public Register of All Arms and Bearings in Scotland. Edinburgh: W. Green & Sons – via Internet Archive.

- Pinches, J. H. (1994). European Nobility and Heraldry. Heraldry Today. ISBN 0-900455-45-4.

- Reid of Robertland, David; Wilson, Vivien (1977). An Ordinary of Arms. Vol. Second. Edinburgh: Lyon Office.

- Rietstap, Johannes B. (1967). Armorial General. Baltimore: Genealogical Publishing.

- Siebmacher, Johann. J. (1890–1901). Siebmacher's Grosses und Allgemeines Wappenbuch Vermehrten Auglage. Nürnberg: Von Bauer & Raspe.

- Slater, Stephen (2003). The Complete Book of Heraldry. New York: Hermes House. ISBN 9781844772247.

- von Volborth, Carl-Alexander (1981). Heraldry – Customs, Rules and Styles. Ware, Hertfordshire: Omega Books. ISBN 0-907853-47-1.

- Wagner, Anthony (1946). Heraldry in England. Penguin. OCLC 878505764.

- Wagner, Anthony R (1967). Heralds of England: A History of the Office and College of Arms. London: Her Majesty's Stationery Office.

- von Warnstedt, Christopher (October 1970). "The Heraldic Provinces of Europe". The Coat of Arms. XI (84).

- Woodcock, Thomas; Robinson, John Martin (1988). The Oxford Guide to Heraldry. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Woodward, John; Burnett, George (1892) [1884]. Woodward's a treatise on heraldry, British and foreign: with English and French glossaries. Edinburgh: W. & A. B. Johnson. ISBN 0-7153-4464-1. LCCN 02020303 – via Internet Archive.

{{cite book}}: ISBN / Date incompatibility (help)

External links

[edit]- EuropeanHeraldry.org catalogues a large number of European noble titles and heraldry.

- Heraldry of Greatlitvan Nobility

- Heraldry of the World (civic heraldry), an overview of thousands of coats of arms of towns and countries

- Barron, Oswald (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 13 (11th ed.). pp. 311–330.

- International heraldry Introduction and examples

- Heraldisk Selskab The Scandinavian Heraldry Society (one of the oldest and largest societies dedicated to heraldic research)

- Heraldry for Kids Introducing Heraldry for Kids with free heraldry activity sheets

- Heraldica The history of heraldry, knighthood and chivalry, glossary of the blazon, themes, coats of arms, etc.

- Heraldic Arts Founded in 1987, the Society of Heraldic Arts was the first organisation of its kind in the world.

Heraldry

View on GrokipediaHistorical Development

Precursors and Early Symbolic Systems

In ancient Mesopotamia, symbolic standards emerged as early tools for military identification around 2600 BCE, as illustrated on the Standard of Ur, a mosaic box depicting war scenes with figures possibly bearing emblems tied to units or deities to coordinate forces amid chaotic battles.[4] These artifacts highlight a practical emphasis on visibility and rallying points, driven by the tactical necessity of distinguishing allies from foes in close-quarters combat rather than decorative or hereditary purposes.[5] Ancient Egyptian forces similarly utilized standards by the late Predynastic period, circa 3100 BC, as shown on the Narmer Palette where four standards—depicting animals like falcons and bulls associated with nomes or protective gods—are carried before the king, Narmer, to signify territorial allegiances and divine sanction during conquests.[6] The serekh, a rectangular enclosure containing the royal Horus name above these standards, functioned as a personal identifier linking the ruler to the falcon god Horus, underscoring causal utility in warfare for command recognition without codified rules.[7] Roman legions formalized unit emblems through standards like the aquila eagle, adopted by 104 BC as a legionary symbol embodying imperial authority and serving as a focal point for troop cohesion in engagements. By the late Empire, as documented in the Notitia Dignitatum (circa 395–423 CE), shields bore distinct blazons such as animals or geometric motifs unique to cohorts, enabling rapid visual differentiation on the battlefield and foreshadowing heraldic principles through empirical adaptation to infantry needs, though lacking personal heritability.[8] Among Iron Age Celts, shield decorations featuring motifs like boars or knot patterns, evident in artifacts from the 1st century BCE, provided tribal markers of strength and protection, prioritizing functional intimidation and group identity in tribal skirmishes over systematized symbolism.[9] Germanic groups employed rudimentary totemic symbols and early runes inscribed on gear for personal or clan distinction in warfare from the Migration Period onward, rooted in practical lore rather than institutional precedent, thus linking ad hoc visual cues to the later evolution of fixed emblems.[10]Emergence in Twelfth-Century Europe

The emergence of heraldry in twelfth-century Europe stemmed from the practical requirements of identifying armored knights during tournaments and battles, where enclosed helmets and visors increasingly obscured facial features, rendering traditional recognition methods ineffective.[11] This need intensified with the rise of tournaments around 1100 and participation in the Crusades, particularly the Second Crusade (1147–1149), where knights required distinctive markers for allies and foes amid chaotic melee combat.[12] Initially, knights adopted personal devices—simple geometric patterns or symbols—painted on shields, surcoats, and banners to ensure visibility and prevent battlefield confusion, without any centralized authority dictating designs.[13] The earliest datable evidence of consistent armorial bearings appears in the 1140s to 1160s, primarily through seals and monumental art. A pivotal example is the enamel funerary plaque of Geoffrey V, Count of Anjou (died 1151), preserved in Le Mans Cathedral, which shows him bearing a blue shield semé of golden lions rampant, marking one of the first attested heraldic compositions linked to a specific individual.[11] [14] By the 1160s, equestrian seals of high nobility, such as that of Philip I, Count of Flanders (1164), routinely featured heraldic shields, indicating widespread adoption among the European aristocracy.[15] These devices originated as ad hoc choices by bearers, reflecting personal or regional motifs, and spread rapidly via returning crusaders and tournament circuits across France, England, and the Holy Roman Empire.[12] By the late twelfth century, these personal emblems had evolved into inheritable symbols, transmitted from father to son, fostering lineage-based identification that solidified social hierarchies.[11] This transition occurred organically, as evidenced by consistent use across generations in Angevin noble families, without formal regulation, laying the groundwork for heraldry's role in feudal society.[13] The practice's utility in distinguishing combatants and signaling status ensured its persistence and refinement into a systematic visual language.[2]Institutionalization Through Heralds

![Pursuivant of arms, a junior heraldic officer][float-right] Professional heralds emerged as key institutionalizers of heraldry in 13th-century Europe, initially organizing tournaments by proclaiming events, marshalling participants, and identifying combatants via their arms to prevent misidentification in melee.[16] Their expertise extended to verifying and recording armorial bearings, ensuring uniqueness to maintain order in chivalric and diplomatic contexts, where heralds also served as messengers immune from harm under truce conventions.[16] By regulating grants and usages, heralds shifted heraldry from ad hoc personal symbols to a systematized practice grounded in empirical documentation rather than unsubstantiated claims.[17] In England, heralds integrated into the royal household by the 13th century, with principal kings of arms appointed under Edward III (r. 1327–1377) to oversee armorial matters, including royal grants to favored subjects, marking the onset of centralized control.[17] Early rolls of arms, compiled from the 1240s onward—such as the Glover's Roll (c. 1240–1250)—provided primary records of verified bearings used by heralds to authenticate claims, demonstrating that armigerous status required documented precedence over presumed nobility.[18] These compilations, often created post-battle or for tournaments, served as evidentiary baselines for resolving disputes. The 1385–1390 Scrope v. Grosvenor case before the Court of Chivalry exemplified heralds' regulatory enforcement, as officers testified to the Scropes' prior right to azure, a bend or, compelling the Grosvenors to adopt a differenced version with a bordure argent.[3] This precedent, reliant on heraldic witnesses and records rather than self-assertion, affirmed that arms demanded verifiable historical or granted exclusivity, curbing conflicts and formalizing heraldry's legal framework under the Earl Marshal's jurisdiction.[19] Heralds' records thus countered notions of universal noble entitlement, prioritizing causal chains of documented transmission.[18]Peak Usage and Regional Divergence