Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

French Canadians

View on Wikipedia

Key Information

| Part of a series of articles on the |

| French people |

|---|

|

French Canadians, referred to as Canadiens mainly before the nineteenth century, are an ethnic group descended from French colonists first arriving in France's colony of Canada in 1608.[4] The vast majority of French Canadians live in the province of Quebec.

During the 17th century, French settlers originating mainly from the west and north of France settled Canada.[5] It is from them that the French Canadian ethnicity was born. During the 17th to 18th centuries, French Canadians expanded across North America and colonized various regions, cities, and towns.[6] As a result, people of French Canadian descent can be found across North America. Between 1840 and 1930, many French Canadians emigrated to New England, an event known as the Grande Hémorragie.[7]

Etymology

[edit]French Canadians get their name from the French colony of Canada, the most developed and densely populated region of New France during the period of French colonization in the 17th and 18th centuries. The original use of the term Canada referred to the area of present-day Quebec along the St. Lawrence River, divided in three districts (Québec, Trois-Rivières, and Montréal), as well as to the Pays d'en Haut (Upper Countries), a vast and thinly settled territorial dependence north and west of Montreal which covered the whole of the Great Lakes area.

From 1535 to the 1690s, Canadien was a word used by the French to refer to the First Nations they had encountered in the St. Lawrence River valley at Stadacona and Hochelaga; however, First Nations groups did not refer to themselves as Canadien.[8] At the end of the 17th century, Canadien became an ethnonym distinguishing the French inhabitants of Canada from those of France. At the end of the 18th century, to distinguish between the English-speaking population and the French-speaking population, the terms English Canadian and French Canadian emerged.[9] During the Quiet Revolution of the 1960s to 1980s, inhabitants of Quebec began to identify as Québécois instead of simply French Canadian.[10]

History

[edit]

French settlers from Normandy, Perche, Beauce, Brittany, Maine, Anjou, Touraine, Poitou, Aunis, Angoumois, Saintonge, and Gascony were the first Europeans to permanently colonize what is now Quebec, parts of Ontario, Acadia, and select areas of Western Canada, all in Canada (see French colonization of the Americas). Their colonies of New France (also commonly called Canada) stretched across what today are the Maritime provinces, southern Quebec and Ontario, as well as the entire Mississippi River Valley.

The first permanent European settlements in Canada were at Port Royal in 1605 and Quebec City in 1608 as fur trading posts. The territories of New France were Canada, Acadia (later renamed Nova Scotia), and Louisiana; the mid-continent Illinois Country was at first governed from Canada and then attached to Louisiana. The inhabitants of the French colony of Canada (modern-day Quebec) called themselves the Canadiens, and came mostly from northwestern France.[11] The early inhabitants of Acadia, or Acadians (Acadiens), came mostly but not exclusively from the southwestern regions of France.

Canadien explorers and fur traders would come to be known as coureurs des bois and voyageurs, while those who settled on farms in Canada would come to be known as habitants. Many French Canadians are the descendants of the King's Daughters (Filles du Roi) of this era. A few also are the descendants of mixed French and Algonquian marriages (see also Metis people and Acadian people). During the mid-18th century, French explorers and Canadiens born in French Canada colonized other parts of North America in what are today the states of Louisiana, Mississippi, Missouri, Illinois, Vincennes, Indiana, Louisville, Kentucky, the Windsor-Detroit region and the Canadian prairies (primarily Southern Manitoba).

After the 1760 British conquest of New France in the French and Indian War (known as the Seven Years' War in Canada), the French-Canadian population remained important in the life of the colonies. The British gained Acadia by the Treaty of Utrecht in 1713. It took the 1774 Quebec Act for French Canadians to regain the French civil law system, and in 1791 French Canadians in Lower Canada were introduced to the parliamentary system when an elected Legislative Assembly was created. The Legislative Assembly having no real power, the political situation degenerated into the Lower Canada Rebellions of 1837–1838, after which Lower Canada and Upper Canada were unified. Some of the motivations for the union was to limit French-Canadian political power and at the same time transferring a large part of the Upper Canadian debt to the debt-free Lower Canada. After many decades of British immigration, the Canadiens became a minority in the Province of Canada in the 1850s.

French-Canadian contributions were essential in securing responsible government for the Canadas and in undertaking Canadian Confederation. In the late 19th and 20th centuries, French Canadians' discontent grew with their place in Canada because of a series of events: including the execution of Louis Riel, the elimination of official bilingualism in Manitoba, Canada's military participation in the Second Boer War, Regulation 17 which banned French-language schools in Ontario, the Conscription Crisis of 1917 and the Conscription Crisis of 1944.[12][13]

Between the 1840s and the 1930s, some 900,000 French Canadians immigrated to the New England region. About half of them returned home. The generations born in the United States would eventually come to see themselves as Franco-Americans. During the same period of time, numerous French Canadians also migrated and settled in Eastern and Northern Ontario. The descendants of those Quebec inter-provincial migrants constitute the bulk of today's Franco-Ontarian community.

Since 1968, French has been one of Canada's two official languages. It is the sole official language of Quebec and one of the official languages of New Brunswick, Yukon, the Northwest Territories, and Nunavut. The province of Ontario has no official languages defined in law, although the provincial government provides French language services in many parts of the province under the French Language Services Act.

Demography

[edit]Language

[edit]There are many varieties of French spoken by francophone Canadians, for example Quebec French, Acadian French, Métis French, and Newfoundland French. The French spoken in Ontario, the Canadian West, and New England can trace their roots back to Quebec French because of Quebec's diaspora. Over time, many regional accents have emerged. Canada is estimated to be home to between 32 and 36 regional French accents,[14][15] 17 of which can be found in Quebec, and seven of which are found in New Brunswick.[16] There are also people who will naturally speak using Québécois Standard or Joual which are considered sociolects.

There are about seven million French Canadians and native French speakers in Quebec. Another one million French-speaking French Canadians are distributed throughout the rest of Canada. French Canadians may also speak Canadian English, especially if they live in overwhelmingly English-speaking environments. In Canada, not all those of French Canadian ancestry speak French, but the vast majority do.

Francophones living in Canadian provinces other than Quebec have enjoyed minority language rights under Canadian law since the Official Languages Act of 1969, and under the Canadian Constitution since 1982, protecting them from provincial governments that have historically been indifferent towards their presence. At the provincial level, New Brunswick formally designates French as a full official language, while other provinces vary in the level of French language services they offer. All three of Canada's territories include French as an official language of the territory alongside English and local indigenous languages; however, in practice, French-language services are normally available only in the capital cities and not across the entire territory.[citation needed]

Religion

[edit]Catholicism is the chief denomination amongst French Canadians. The kingdom of France forbade non-Catholic settlement in New France from 1629 onward; thus, almost all French settlers of Canada were Catholic. In the United States, some families of French-Canadian origin have converted to Protestantism. Until the 1960s, religion was a central component of French-Canadian national identity. The Church parish was the focal point of civic life in French-Canadian society, and religious orders ran French-Canadian schools, hospitals and orphanages and were very influential in everyday life in general. During the Quiet Revolution of the 1960s, however, the practice of Catholicism dropped drastically.[17]

| Religious group | 2021[18][b] | 2001[19][c] | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pop. | % | Pop. | % | |

| Christianity | 3,111,025 | 63.26% | 4,086,585 | 87.54% |

| Islam | 8,805 | 0.18% | 5,325 | 0.11% |

| Irreligion | 1,744,545 | 35.47% | 551,100 | 11.8% |

| Judaism | 10,855 | 0.22% | 8,575 | 0.18% |

| Buddhism | 1,285 | 0.03% | 4,995 | 0.11% |

| Hinduism | 975 | 0.02% | 665 | 0.01% |

| Indigenous spirituality | 3,775 | 0.08% | 3,105 | 0.07% |

| Sikhism | 275 | 0.01% | 345 | 0.01% |

| Other | 29,650 | 0.6% | 7,700 | 0.16% |

| Total French Canadian population | 4,917,990 | 100% | 4,668,410 | 100% |

| Religious group | 2021[18][b] | 2001[19][c] | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pop. | % | Pop. | % | |

| Catholic | 2,502,585 | 80.44% | 3,373,730 | 82.56% |

| Orthodox | 8,805 | 0.28% | 7,110 | 0.17% |

| Protestant | 350,365 | 11.26% | 628,275 | 15.37% |

| Other Christian | 249,270 | 8.01% | 77,470 | 1.9% |

| Total French canadian christian population | 3,111,025 | 100% | 4,086,585 | 100% |

Geographical distribution

[edit]People who claim some French-Canadian ancestry or heritage number some 7 million in Canada. In the United States, 2.4 million people report French-Canadian ancestry or heritage, while an additional 8.4 million claim French ancestry; they are treated as a separate ethnic group by the U.S. Census Bureau.

Canada

[edit]

In Canada, 85% of French Canadians reside in Quebec where they constitute the majority of the population in all regions except the far north (Nord-du-Québec). Most cities and villages in this province were built and settled by the French or French Canadians during the French colonial rule.

There are various urban and small centres in Canada outside Quebec that have long-standing populations of French Canadians, going back to the late 19th century, due to interprovincial migration. Eastern and Northern Ontario have large populations of francophones in communities such as Ottawa, Cornwall, Hawkesbury, Sudbury, Timmins, North Bay, Timiskaming, Welland and Windsor. Many also pioneered the Canadian Prairies in the late 18th century, founding the towns of Saint Boniface, Manitoba and in Alberta's Peace Country, including the region of Grande Prairie.

It is estimated that roughly 70–75% of Quebec's population descend from the French pioneers of the 17th and 18th century.

The French-speaking population have massively chosen the "Canadian" ("Canadien") ethnic group since the government made it possible (1986), which has made the current statistics misleading. The term Canadien historically referred only to a French-speaker, though today it is used in French to describe any Canadian citizen.

United States

[edit]

In the United States, many cities were founded as colonial outposts of New France by French or French-Canadian explorers. They include Mobile (Alabama), Coeur d'Alene (Idaho), Vincennes (Indiana), Belleville (Illinois), Bourbonnais (Illinois), Prairie du Rocher (Illinois), Dubuque (Iowa), Baton Rouge (Louisiana), New Orleans (Louisiana), Detroit (Michigan), Biloxi (Mississippi), Creve Coeur (Missouri), St. Louis (Missouri), Pittsburgh (Fort Duquesne, Pennsylvania), Provo (Utah), Green Bay (Wisconsin), La Crosse (Wisconsin), Milwaukee (Wisconsin) or Prairie du Chien (Wisconsin).

The majority of the French-Canadian population in the United States is found in the New England area, although there is also a large French-Canadian presence in Plattsburgh, New York, across Lake Champlain from Burlington, Vermont. Quebec and Acadian emigrants settled in industrial cities like Fitchburg, Leominster, Lynn, Worcester, Haverhill, Waltham, Lowell, Gardner, Lawrence, Chicopee, Somerset, Fall River, and New Bedford in Massachusetts; Woonsocket in Rhode Island; Manchester and Nashua in New Hampshire; Bristol, Hartford, and East Hartford in Connecticut; throughout the state of Vermont, particularly in Burlington, St. Albans, and Barre; and Biddeford and Lewiston in Maine. Smaller groups of French Canadians settled in the Midwest, notably in the states of Michigan, Illinois, Wisconsin, Nebraska, Iowa, Missouri, and Minnesota. French Canadians also settled in central North Dakota, largely in Rolette and Bottineau counties, and in South Dakota.

Some Metis still speak Michif, a language influenced by French, and a mixture of other European and Native American tribal languages.

Identities

[edit]Canada

[edit]

| Year | Pop. | ±% |

|---|---|---|

| 1871 | 1,082,940 | — |

| 1881 | 1,298,929 | +19.9% |

| 1901 | 1,649,371 | +27.0% |

| 1911 | 2,061,719 | +25.0% |

| 1921 | 2,452,743 | +19.0% |

| 1931 | 2,927,990 | +19.4% |

| 1941 | 3,483,038 | +19.0% |

| 1951 | 4,319,167 | +24.0% |

| 1961 | 5,540,346 | +28.3% |

| 1971 | 6,180,120 | +11.5% |

| 1981 | 7,111,540 | +15.1% |

| 1986 | 8,123,360 | +14.2% |

| 1991 | 8,389,180 | +3.3% |

| 1996 | 5,709,215 | −31.9% |

| 2001 | 4,809,250 | −15.8% |

| 2006 | 5,146,940 | +7.0% |

| 2011 | 5,386,995 | +4.7% |

| 2016 | 4,995,040 | −7.3% |

| Source: Statistics Canada [27]: 17 [28][29][30][31][32][33][34][35][36][37][1] Note 1: 1981 Canadian census only included partial multiple ethnic origin responses for individuals with British and French ancestry. Note 2: 1996-present censuses include the "Canadian" ethnic origin category. | ||

French Canadians express their cultural or ancestral roots using a number of different terms. In the 2021 census, French-speaking Canadians identified their ethnicity, in order of prevalence, most often as Canadian, French, Québécois, French Canadian, and Acadian. All of these except for French were grouped together by Jantzen (2006) as "French New World" ancestries because they originate in Canada.[22][38]

Jantzen (2006) distinguishes the English Canadian, meaning "someone whose family has been in Canada for multiple generations", and the French Canadien, used to refer to descendants of the original settlers of New France in the 17th and 18th centuries.[23] "Canadien" was used to refer to the French-speaking residents of New France beginning in the last half of the 17th century. The English-speaking residents who arrived later from Great Britain were called "Anglais". This usage continued until Canadian Confederation in 1867.[39] Confederation united several former British colonies into the Dominion of Canada, and from that time forward, the word "Canadian" has been used to describe both English-speaking and French-speaking citizens, wherever they live in the country.

Those reporting "French New World" ancestries overwhelmingly had ancestors that went back at least four generations in Canada.[24] Fourth generation Canadiens and Québécois showed considerable attachment to their ethno-cultural group, with 70% and 61%, respectively, reporting a strong sense of belonging.[25]

The generational profile and strength of identity of French New World ancestries contrast with those of British or Canadian ancestries, which represent the largest ethnic identities in Canada.[26] Although deeply rooted Canadians express a deep attachment to their ethnic identity, most English-speaking Canadians of British or Canadian ancestry generally cannot trace their ancestry as far back in Canada as French speakers.[40] As a result, their identification with their ethnicity is weaker: for example, only 50% of third generation "Canadians" strongly identify as such, bringing down the overall average.[41] The survey report notes that 80% of Canadians whose families had been in Canada for three or more generations reported "Canadian and provincial or regional ethnic identities". These identities include French New World ancestries such as "Québécois" (37% of Quebec population) and Acadian (6% of Atlantic provinces).[42]

Quebec

[edit]

Since the 1960s, French Canadians in Quebec have generally used Québécois (masculine) or Québécoise (feminine) to express their cultural and national identity, rather than Canadien français and Canadienne française. Francophones who self-identify as Québécois and do not have French-Canadian ancestry may not identify as "French Canadian" (Canadien or Canadien français); however, by extension, though the term "French Canadian" may refer to natives of the province of Quebec or other parts of French Canada of foreign descent.[43][44][45][46] Those who do have French or French-Canadian ancestry, but who support Quebec sovereignty, often find Canadien français to be archaic or even pejorative. This is a reflection of the strong social, cultural, and political ties that most Quebecers of French-Canadian origin, who constitute a majority of francophone Quebecers, maintain within Quebec. It has given Québécois an ambiguous meaning[47] which has often played out in political issues,[48] as all public institutions attached to the Government of Quebec refer to all Quebec citizens, regardless of their language or their cultural heritage, as Québécois.

Academic analysis of French Canadian culture has often focused on the degree to which the Quiet Revolution, particularly the shift in the social and cultural identity of the Québécois following the Estates General of French Canada of 1966 to 1969, did or did not create a "rupture" between the Québécois and other francophones elsewhere in Canada.[49]

Elsewhere in Canada

[edit]The emphasis on the French language and Quebec autonomy means that French speakers across Canada may now self-identify as québécois(e), acadien(ne), or Franco-canadien(ne), or as provincial linguistic minorities such as Franco-manitobain(e), Franco-ontarien(ne) or fransaskois(e).[50] Education, health and social services are provided by provincial institutions, so that provincial identities are often used to identify French-language institutions:

- Franco-Newfoundlanders, province of Newfoundland and Labrador, also known as Terre-Neuvien(ne)

- Franco-Ontarians, province of Ontario, also referred to as Ontarien(ne)

- Franco-Manitobans, province of Manitoba, also referred to as Manitobain(e)

- Fransaskois, province of Saskatchewan, also referred to Saskois(e)

- Franco-Albertans, province of Alberta, also referred to Albertain(e)

- Franco-Columbians, province of British Columbia mostly live in the Vancouver metro area; also referred to as Franco-Colombien(ne)

- Franco-Yukonnais, territory of Yukon, also referred to as Yukonais(e)

- Franco-Ténois, territory of Northwest Territories, also referred to as Ténois(e)

- Franco-Nunavois, territory of Nunavut, also referred to as Nunavois(e)

Acadians residing in the provinces of New Brunswick, Prince Edward Island and Nova Scotia represent a distinct ethnic French-speaking culture. This group's culture and history evolved separately from the French Canadian culture, at a time when the Maritime Provinces were not part of what was referred to as Canada, and are consequently considered a distinct culture from French Canadians.

Brayons in Madawaska County, New Brunswick and Aroostook County, Maine may be identified with either the Acadians or the Québécois, or considered a distinct group in their own right, by different sources.

French Canadians outside Quebec are more likely to self-identify as "French Canadian". Identification with provincial groupings varies from province to province, with Franco-Ontarians, for example, using their provincial label far more frequently than Franco-Columbians do. Few identify only with the provincial groupings, explicitly rejecting "French Canadian" as an identity label. A population genetics ancestry study claims that for those French Canadians who trace their ancestry to the French founder population, a significant percentage, 53-78% have at least one indigenous ancestor.[51]

United States

[edit]

During the mid-18th century, French Canadian explorers and colonists colonized other parts of North America in what are today Louisiana (called Louisianais), Mississippi, Missouri, Illinois, Wisconsin, Indiana, Ohio, far northern New York and the Upper Peninsula of Michigan as well as around Detroit.[52] They also founded such cities as New Orleans and St. Louis and villages in the Mississippi Valley. French Canadians later emigrated in large numbers from Canada to the United States between the 1840s and the 1930s in search of economic opportunities in border communities and industrialized portions of New England.[53] French-Canadian communities in the United States remain along the Quebec border in Maine, Vermont, and New Hampshire, as well as further south in Massachusetts, Rhode Island, and Connecticut. There is also a significant community of French Canadians in South Florida, particularly Hollywood, Florida, especially during the winter months. The wealth of Catholic churches named after St. Louis throughout New England is indicative of the French immigration to the area. They came to identify as Franco-American, especially those who were born American.

Distinctions between French Canadian, natives of France, and other New World French identities is more blurred in the U.S. than in Canada; however, those who identify as French Canadian or Franco American generally do not regard themselves as French. Rather, they identify culturally, historically, and ethnically with the culture that originated in Quebec that is differentiated from French culture. In L'Avenir du français aux États-Unis, Calvin Veltman and Benoît Lacroix found that since the French language has been so widely abandoned in the United States, the term "French Canadian" has taken on an ethnic rather than linguistic meaning.[54]

French Canadian identities are influenced by historical events that inform regional cultures. For example, in New England, the relatively recent immigration (19th/20th centuries) is informed by experiences of language oppression and an identification with certain occupations, such as the mill workers. In the Great Lakes, many French Canadians also identify as Métis and trace their ancestry to the earliest voyageurs and settlers; many also have ancestry dating to the lumber era and often a mixture of the two groups.

The main Franco-American regional identities are:

- French Canadians:

- French Canadians of the Great Lakes (including Muskrat French)

- New England French

- Creoles:

- Missouri French (and other people of French ancestry in the former Illinois Country)

- Louisiana Creoles (who speak Colonial French)

- Cajuns

Culture

[edit]Agriculture

[edit]Traditionally, Canadiens had a subsistence agriculture in Eastern Canada (Québec). This subsistence agriculture slowly evolved in dairy farm during the end of the 19th century and the beginning of 20th century while retaining the subsistence side. By 1960, agriculture changed toward an industrial agriculture. French Canadians have selectively bred distinct livestock over the centuries, including cattle, horses and chickens.[55][56]

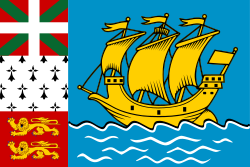

Flags

[edit]From New France

[edit]-

Royal pavilion of 1534 to 1599.

-

Pavilion of the merchant navy from 1600 to 1663.

-

Royal pavilion of 1663 to 1763.

After the conquest

[edit]-

Flag of Quebec in 1948.

Of French Canadian civic institutions

[edit]Of francophone groups located in native land

[edit]Of francophone groups formed by French Canadian emigration

[edit]Of other groups originating from the colonisation of New France

[edit]See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ a b 1981-present: Statistic also includes "Acadian" and "Quebecois" responses. Additionally, 1996-present census populations are undercounts, due to the addition of the "Canadian" (English) or "Canadien" (French) ethnic origin. All citizens of Canada are classified as "Canadians" as defined by Canada's nationality laws. However, "Canadian" as an ethnic group has since 1996 been added to census questionnaires for possible ancestry. "Canadian" was included as an example on the English questionnaire and "Canadien" as an example on the French questionnaire. "The majority of respondents to this selection are from the eastern part of the country that was first settled. Respondents generally are visibly European (Anglophones and Francophones), however no-longer self identify with their ethnic ancestral origins. This response is attributed to a multitude or generational distance from ancestral lineage.[20][21][22][23][24][25][26]

- ^ a b Religious breakdown proportions based on "French" ethnic or cultural origin response on the 2021 census.[18]

- ^ a b Religious breakdown proportions based on "French" ethnic or cultural origin response on the 2001 census.[19]

References

[edit]- ^ a b Government of Canada, Statistics Canada (June 17, 2019). "Ethnic Origin (279), Single and Multiple Ethnic Origin Responses (3), Generation Status (4), Age (12) and Sex (3) for the Population in Private Households of Canada, Provinces and Territories, Census Metropolitan Areas and Census Agglomerations, 2016 Census - 25% Sample Data". www12.statcan.gc.ca. Archived from the original on October 26, 2017. Retrieved September 24, 2022.

- ^ Government of Canada, Statistics Canada (August 17, 2022). "Census Profile, 2021 Census of Population Profile table Canada [Country]". www12.statcan.gc.ca. Archived from the original on September 20, 2022. Retrieved September 25, 2022.

- ^ "Table B04006 - People Reporting Ancestry - 2020 American Community Survey 5-Year Estimates". United States Census Bureau. Archived from the original on July 13, 2022. Retrieved October 12, 2022.

- ^ New, William H. (2002). Encyclopedia of Literature in Canada. University of Toronto Press. p. 190. ISBN 978-0-8020-0761-2.

- ^ G. E. Marquis and Louis Allen, "The French Canadians in the Province of Quebec" Archived February 24, 2017, at the Wayback Machine. The Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, Vol. 107, Social and Economic Conditions in The Dominion of Canada (May, 1923), pp. 7–12.

- ^ R. Louis Gentilcore (January 1987). Historical Atlas of Canada: The land transformed, 1800–1891. University of Toronto Press. ISBN 0-8020-3447-0.

- ^ "French Canadian Emigration to the United States, 1840–1930". Marianopolis College. Archived from the original on November 4, 2021. Retrieved June 18, 2014.

- ^ "Gervais Carpin, Histoire d'un mot". Celat.ulaval.ca. Archived from the original on July 6, 2011. Retrieved January 28, 2011.

- ^ Kuitenbrouwer, Peter (June 27, 2017). "The Strange History of 'O Canada'". The Walrus. Archived from the original on August 17, 2021. Retrieved July 7, 2017.

- ^ Beauchemin, Jacques (2009). Collectif Liberté (ed.). "L'identité franco-québécoise d'hier à aujourd'hui: la fin des vieilles certitudes". Liberté. 51 (3). ISSN 0024-2020.

- ^ Marquis, G. E.; Allen, Louis (January 1, 1923). "The French Canadians in the Province of Quebec". The Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science. 107: 7–12. doi:10.1177/000271622310700103. JSTOR 1014689. S2CID 143714682.

- ^ Paul-André Linteau, René Durocher, and Jean-Claude Robert, Quebec: a history 1867–1929 (1983) p. 261–272.

- ^ P.B. Waite, Canada 1874–1896 (1996), pp 165–174.

- ^ "Our 32 Accents". Quebec Culture Blog. November 14, 2014. Archived from the original on April 11, 2021. Retrieved February 26, 2021.

- ^ "Le francais parlé de la Nouvelle-France" (in French). Government of Canada. April 27, 2020. Archived from the original on May 11, 2021. Retrieved November 1, 2021.

- ^ Parent, Stéphane (March 30, 2017). "Le francais dans tous ses etats au quebec et au canada". Radio-Canada. Archived from the original on April 13, 2021. Retrieved November 1, 2021.

- ^ Claude Bélenger (August 23, 2000). "The Quiet Revolution". Archived from the original on February 2, 2008. Retrieved March 2, 2011.

- ^ a b c Government of Canada, Statistics Canada (May 10, 2023). "Religion by ethnic or cultural origins: Canada, provinces and territories and census metropolitan areas with parts". www12.statcan.gc.ca. Retrieved September 15, 2024.

- ^ a b c Government of Canada, Statistics Canada (December 23, 2013). "2001 Census Topic-based tabulations Selected Demographic and Cultural Characteristics (105), Selected Ethnic Groups (100), Age Groups (6), Sex (3) and Single and Multiple Ethnic Origin Responses (3) for Population, for Canada, Provinces, Territories and Census Metropolitan Areas, 2001 Census - 20% Sample Data". www12.statcan.gc.ca. Retrieved September 21, 2025.

- ^ Jack Jedwab (April 2008). "Our 'Cense' of Self: the 2006 Census saw 1.6 million 'Canadian'" (PDF). Association for Canadian Studies. Archived from the original (PDF) on October 2, 2011. Retrieved March 7, 2011.

"Virtually all persons who reported "Canadian" in 1996 had English or French as a mother tongue, were born in Canada and had both parents born inside Canada. This suggests that many of these respondents were people whose families have been in this country for several generations. In effect the "new Canadians" were persons that previously reported either British or French origins. Moreover in 1996 some 55% of people with both parents born in Canada reported Canadian (alone or in combination with other origins). By contrast, only 4% of people with both parents born outside Canada reported Canadian. Thus the Canadian response did not appeal widely to either immigrants or their children. Most important however was that neatly half of those persons reporting Canadian origin in 1996 were in Quebec this represented a majority of the mother tongue francophone population. ... In the 2001 Census, 11.7 million people, or 39% of the total population, reported Canadian as their ethnic origin, either alone or in combination with other origins. Some 4.9 million Quebecers out of 7.1 million individuals reported Canadian or "Canadien" thus accounting for nearly seven in ten persons (nearly eighty percent of francophones in Quebec). (Page 2)

- ^ Don Kerr (2007). The Changing Face of Canada: Essential Readings in Population. Canadian Scholars' Press. pp. 313–317. ISBN 978-1-55130-322-2.

- ^ a b Jantzen, Lorna (2003). "The Advantages of Analyzing Ethnic Attitudes Across Generations—Results From the Ethnic Diversity Survey" (PDF). Canadian and French Perspectives on Diversity: 103–118. Archived (PDF) from the original on February 24, 2021. Retrieved May 7, 2012.

- ^ a b Jantzen (2006) Footnote 5: "Note that Canadian and Canadien have been separated since the two terms mean different things. In English, it usually means someone whose family has been in Canada for multiple generations. In French it is referring to "Les Habitants", settlers of New France during the 17th and 18th centuries who earned their living primarily from agricultural labour."

- ^ a b Jantzen (2006): "The reporting of French New World ancestries (Canadien, Québécois, and French-Canadian) is concentrated in the 4th+ generations; 79% of French-Canadian, 88% of Canadien and 90% of Québécois are in the 4th+generations category."

- ^ a b Jantzen (2005): "According to Table 3, the 4th+ generations are highest because of a strong sense of belonging to their ethnic or cultural group among those respondents reporting the New World ancestries of Canadien and Québécois."

- ^ a b Jantzen (2006): For respondents of French and New World ancestries the pattern is different. Where generational data is available, it is possible to see that not all respondents reporting these ancestries report a high sense of belonging to their ethnic or cultural group. The high proportions are focused among those respondents that are in the 4th+ generations, and unlike with the British Isles example, the difference between the 2nd and 3rd generations to the 4th+ generation is more pronounced. Since these ancestries are concentrated in the 4th+ generations, their high proportions of sense of belonging to ethnic or cultural group push up the 4th+ generational results."

- ^ Government of Canada, Statistics Canada (July 29, 1999). "Historical statistics of Canada, section A: Population and migration - Archived". www12.statcan.gc.ca. Archived from the original on September 28, 2022. Retrieved September 24, 2022.

- ^ Government of Canada, Statistics Canada (April 3, 2013). "1961 Census of Canada : population : vol. I - part 2 = 1961 Recensement du Canada : population: vol. I - partie 2. Ethnic groups". www12.statcan.gc.ca. Archived from the original on September 18, 2022. Retrieved September 24, 2022.

- ^ Government of Canada, Statistics Canada (April 3, 2013). "1971 Census of Canada : population : vol. I - part 3 = Recensement du Canada 1971 : population: vol. I - partie 3. Ethnic groups". www12.statcan.gc.ca. Archived from the original on September 18, 2022. Retrieved September 24, 2022.

- ^ Government of Canada, Statistics Canada (April 3, 2013). "1981 Census of Canada : volume 1 - national series : population = Recensement du Canada de 1981 : volume 1 - série nationale: population. Ethnic origin". www12.statcan.gc.ca. Archived from the original on September 27, 2022. Retrieved September 24, 2022.

- ^ Government of Canada, Statistics Canada (April 3, 2013). "Census Canada 1986 Profile of ethnic groups". www12.statcan.gc.ca. Archived from the original on September 14, 2022. Retrieved September 24, 2022.

- ^ Government of Canada, Statistics Canada (April 3, 2013). "1986 Census of Canada: Ethnic Diversity In Canada". www12.statcan.gc.ca. Archived from the original on September 12, 2022. Retrieved September 24, 2022.

- ^ Government of Canada, Statistics Canada (April 3, 2013). "1991 Census: The nation. Ethnic origin". www12.statcan.gc.ca. Archived from the original on April 18, 2023. Retrieved September 24, 2022.

- ^ Government of Canada, Statistics Canada (June 4, 2019). "Data tables, 1996 Census Population by Ethnic Origin (188) and Sex (3), Showing Single and Multiple Responses (3), for Canada, Provinces, Territories and Census Metropolitan Areas, 1996 Census (20% Sample Data)". www12.statcan.gc.ca. Archived from the original on August 12, 2019. Retrieved September 24, 2022.

- ^ Government of Canada, Statistics Canada (December 23, 2013). "Ethnic Origin (232), Sex (3) and Single and Multiple Responses (3) for Population, for Canada, Provinces, Territories, Census Metropolitan Areas and Census Agglomerations, 2001 Census - 20% Sample Data". www12.statcan.gc.ca. Archived from the original on September 22, 2022. Retrieved September 24, 2022.

- ^ Government of Canada, Statistics Canada (May 1, 2020). "Ethnic Origin (247), Single and Multiple Ethnic Origin Responses (3) and Sex (3) for the Population of Canada, Provinces, Territories, Census Metropolitan Areas and Census Agglomerations, 2006 Census - 20% Sample Data". www12.statcan.gc.ca. Archived from the original on September 21, 2022. Retrieved September 24, 2022.

- ^ Government of Canada, Statistics Canada (January 23, 2019). "Ethnic Origin (264), Single and Multiple Ethnic Origin Responses (3), Generation Status (4), Age Groups (10) and Sex (3) for the Population in Private Households of Canada, Provinces, Territories, Census Metropolitan Areas and Census Agglomerations, 2011 National Household Survey". www12.statcan.gc.ca. Archived from the original on September 28, 2022. Retrieved September 24, 2022.

- ^ Jantzen (2006) Footnote 9: "These will be called "French New World" ancestries since the majority of respondents in these ethnic categories are Francophones."

- ^ Lacoursière, Jacques; Bouchard, Claude; Howard, Richard (1972). Notre histoire: Québec-Canada, Volume 2 (in French). Montreal: Editions Format. p. 174.

- ^ Jantzen (2006): "As shown on Graph 3, over 30% of respondents reporting Canadian, British Isles or French ancestries are distributed across all four generational categories."

- ^ Jantzen (2006): Table 3: Percentage of Selected Ancestries Reporting that Respondents have a Strong* Sense of Belonging to the Ethnic and Cultural Groups, by Generational Status, 2002 EDS".

- ^ See p. 14 of the report Archived 4 January 2007 at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ "Anthony Duclair's dream of a more inclusive game is becoming reality". Tampa Bay Times. Retrieved August 16, 2024.

- ^ "Laughing in both official languages". The Globe and Mail. October 20, 2004. Retrieved August 16, 2024.

- ^ "Burnside: All grown up". ESPN.com. March 23, 2004. Retrieved August 16, 2024.

- ^ "For my Relevance - Bradley Eng + Corrida - Audrey Gaussiran + MOVE - Clément Le Disquay et Paul Canestraro + Women and Cypresses - Cai Glover". Regroupement québécois de la danse (in French). Retrieved August 16, 2024.

- ^ Bédard, Guy (2001). "Québécitude: An Ambiguous Identity". In Adrienne Shadd; Carl E. James (eds.). Talking about Identity: Encounters in Race, Ethnicity and Language. Toronto: Between the Lines. pp. 28–32. ISBN 1-896357-36-9. Archived from the original on December 17, 2023. Retrieved October 17, 2020.

- ^ "House passes motion recognizing Québécois as nation". Canadian Broadcasting Corporation. November 27, 2006. Archived from the original on September 5, 2021. Retrieved December 21, 2006.

- ^ "Québec/Canada francophone : le mythe de la rupture" Archived August 15, 2021, at the Wayback Machine. Relations 778, May/June 2015.

- ^ Churchill, Stacy (2003). "Language Education, Canadian Civic Identity, and the Identity of Canadians" (PDF). Council of Europe, Language Policy Division. pp. 8–11. Archived from the original on October 30, 2021. Retrieved May 5, 2008.

French speakers usually refer to their own identities with adjectives such as québécoise, acadienne, or franco-canadienne, or by some term referring to a provincial linguistic minority such as franco-manitobaine, franco-ontarienne or fransaskoise.

- ^ Moreau, C.; Lefebvre, J. F.; Jomphe, M.; Bhérer, C.; Ruiz-Linares, A.; Vézina, H.; Roy-Gagnon, M. H.; Labuda, D. (2013). "Native American Admixture in the Quebec Founder Population". PLOS ONE. 8 (6) e65507. Bibcode:2013PLoSO...865507M. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0065507. PMC 3680396. PMID 23776491.

- ^ Balesi, Charles J. (2005). "French and French Canadians". The Electronic Encyclopedia of Chicago. Chicago Historical Society. Archived from the original on May 9, 2008. Retrieved May 5, 2008.

- ^ Bélanger, Damien-Claude; Bélanger, Claude (August 23, 2000). "French Canadian Emigration to the United States, 1840–1930". Quebec History. Marianapolis College CEGEP. Archived from the original on November 4, 2021. Retrieved May 5, 2008.

- ^ Veltman, Calvin; Lacroix, Benoît (1987). L'Avenir du français aux États-Unis. Service des communications. ISBN 978-2-551-08872-0. Archived from the original on December 17, 2023. Retrieved May 1, 2018.

- ^ "Breeds of Livestock – Canadienne Cattle — Breeds of Livestock, Department of Animal Science". afs.okstate.edu. March 18, 2021. Archived from the original on November 7, 2021. Retrieved November 7, 2021.

- ^ "Chantecler Chicken". November 22, 2008. Archived from the original on November 22, 2008. Retrieved November 7, 2021.

Genealogical works

[edit]Below is a list of the main genealogical works retracing the origins of French Canadian families:

- Hubert Charbonneau and Jacques Legaré, Répertoire des actes de baptême, mariage et sépulture et des recensements du Québec ancien, vol. I-XLVII. Montréal : Les Presses de l'Université de Montréal, 1980. (ISBN 2-7606-0471-3)

- René Jetté and collab, Dictionnaire généalogique des familles du Québec. Des origines à 1730, Montréal : Les Presses de l'Université de Montréal, 1983. (ISBN 9782891058155)

- Noël Montgomery Elliot, Les Canadiens français 1600-1900, vol. I-III. Toronto : 1st edition, La Bibliothèque de recherche généalogique, 1992. (ISBN 0-919941-20-6)

- Cyprien Tanguay, Dictionnaire généalogique des familles canadiennes. Depuis la fondation de la colonie jusqu'à nos jours, vol. I-VII, 1871–1890. Nouvelle édition, Montréal : Éditions Élysée, 1975. (ISBN 0-88545-009-4)

Further reading

[edit]- Allan, Greer (1997). The People of New France. (Themes in Canadian History Series). University of Toronto Press. ISBN 0-8020-7816-8. Archived from the original on December 17, 2023. Retrieved October 17, 2020.

- Brault, Gerard J. (1986). The French-Canadian Heritage in New England. University Press of New England. ISBN 0-87451-359-6. Archived from the original on December 17, 2023. Retrieved October 17, 2020.

- Breton, Raymond, and Pierre Savard, eds. "The Quebec and Acadian Diaspora in North America (1982) online book review Archived November 14, 2023, at the Wayback Machine

- Doty, C. Stewart (1985). The First Franco-Americans: New England Life Histories from the Federal Writers' Project, 1938–1939. University of Maine at Orono Press.

- Faragher, John Mack (2005). A Great and Noble Scheme: The Tragic Story of the Expulsion of the French Acadians from Their American Homeland. W. W. Norton.

- Geyh, Patricia Keeney (2002). French Canadian sources: a guide for genealogists. Ancestry Pub. ISBN 1-931279-01-2. Archived from the original on December 17, 2023. Retrieved October 17, 2020.

- Lamarre, Jean. Les Canadiens français du Michigan: leur contribution dans le développement de la vallée de la Saginaw et de la péninsule de Keweenaw, 1840-1914 (Les éditions du Septentrion, 2000). online Archived August 26, 2023, at the Wayback Machine

- Louder, Dean R.; Eric Waddell (1993). French America: Mobility, Identity, and Minority Experience across the Continent. Franklin Philip (trans.). Louisiana State University Press.

- McQuillan, D. Aidan. "Franch-Canadian Communities in the American Upper Midwest during the Nineteenth Century." Cahiers de géographie du Québec 23.58 (1979): 53-72.

- Marquis, G. E.; Louis Allen (May 1923). "The French Canadians in the Province of Quebec". Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science. 107 (Social and Economic Conditions in The Dominion of Canada): 7–12. doi:10.1177/000271622310700103. S2CID 143714682. Archived from the original on April 6, 2023. Retrieved June 18, 2014.

- Newton, Jason L. ""These French Canadian of the Woods are Half-Wild Folk" Wilderness, Whiteness, and Work in North America, 1840–1955." Labour 77 (2016): 121-150. in New Hampshire online Archived July 25, 2023, at the Wayback Machine

- Parker, James Hill (1983). Ethnic Identity: The Case of the French Americans. University Press of America.

- Silver, A. I. (1997). The French-Canadian idea of Confederation, 1864–1900. University of Toronto Press. ISBN 0-8020-7928-8. Archived from the original on December 17, 2023. Retrieved October 17, 2020.

- Sorrell, Richard S. "The survivance of French Canadians in New England (1865–1930): History, geography and demography as destiny." Ethnic and Racial Studies 4.1 (1981): 91-109.

- Szlezák, Edith. Franco-Americans in Massachusetts: "No French no mo' 'round here" (Narr Francke Attempto Verlag, 2010) online Archived October 7, 2023, at the Wayback Machine.

- Map displaying the percentage of the US population claiming French Canadian ancestry by county, United States Census Bureau, Census 2000

French Canadians

View on GrokipediaHistory

Colonial Foundations in New France (1608–1763)

The establishment of New France began with Samuel de Champlain's founding of Quebec on July 3, 1608, marking the first permanent French settlement along the St. Lawrence River. Initially comprising 28 men under the auspices of trading companies, the colony focused on the fur trade as its economic mainstay, exchanging European goods for beaver pelts with Indigenous groups. Champlain cultivated alliances with the Innu, Algonquin, and Huron peoples, notably participating in a 1609 expedition against the Iroquois, which secured trade routes but entrenched ongoing conflicts.[10][11][12] Governed by chartered companies until 1663, New France saw limited immigration and slow growth, with the population reaching approximately 3,000 by the mid-1660s, hindered by high mortality and returns to France. In 1663, King Louis XIV assumed direct control, dispatching administrators, soldiers, and the Carignan-Salières Regiment to bolster defenses and settlement. To address the gender imbalance and promote family formation, around 770 filles du roi—women sponsored by the crown—arrived between 1663 and 1673, marrying settlers and contributing to a surge in birth rates that drove natural increase.[13][14] The fur trade remained central, fostering a dispersed society of seigneuries where habitants farmed under feudal-like grants while engaging in seasonal trading and coureur de bois expeditions. Jesuit missionaries established missions among Indigenous groups, blending evangelization with alliance-building, though epidemics and warfare decimated native populations. By 1760, the colony's population had expanded to about 65,000, predominantly of French descent, laying the demographic foundation for French Canadians through high fertility rates averaging 7-8 children per family. This growth, reliant on endogenous expansion rather than mass immigration— with only around 10,000 permanent European settlers arriving overall—distinguished New France from contemporaneous English colonies.[15][16][13] These foundations, characterized by trade-driven expansion, Indigenous partnerships, and royal demographic policies, positioned New France as a viable but vulnerable territory by the eve of the Seven Years' War in 1756, culminating in its conquest by Britain in 1763. The enduring French-speaking, Catholic populace emerged from this era, with genetic and cultural roots traceable to a narrow pool of 17th-century immigrants primarily from regions like Normandy, Poitou, and Perche.[17]Adaptation and Survival Under British Rule (1763–1840)

Following the Treaty of Paris in 1763, which ceded New France to Britain after the Seven Years' War, the approximately 70,000 French-speaking Canadiens faced potential cultural erasure under Protestant British rule, yet their survival hinged on pragmatic adaptation and limited British settlement in the core St. Lawrence Valley.[18] Initial military governance under Governor James Murray emphasized conciliation, recognizing the Canadiens' loyalty during Pontiac's War (1763–1766) and avoiding aggressive anglicization to prevent unrest; Murray's reports highlighted the impracticality of imposing English common law or Protestantism on a Catholic, French-majority population.[19] With negligible French immigration post-conquest—only about 1,000 arrivals by 1850—the community's growth relied on high natural increase, driven by large families and low mortality, doubling the population roughly every 25 years through endogenous expansion rather than exogenous reinforcement.[20] The Quebec Act of 1774 proved pivotal for institutional survival, revoking the 1763 Royal Proclamation's assimilationist framework by restoring French civil law and the seigneurial land tenure system, granting Catholics freedom of worship, the right to collect tithes, and eligibility for non-denominational public office, while expanding Quebec's territory westward to include hunting grounds for Indigenous allies.[21] This legislation, motivated by British imperial needs for stability amid American colonial tensions, secured Canadien loyalty during the American Revolutionary War (1775–1783), as French leaders rejected invasion offers from Congress, viewing the Act as safeguarding their distinct identity against New England Protestantism.[22] The Catholic Church, unburdened by French episcopal oversight post-conquest, assumed expanded roles in education, parish governance, and social welfare, embedding French language and customs through seminaries and rural curacies, which fostered resilience against anglicizing pressures.[23] The Constitutional Act of 1791 divided the Province of Quebec into Lower Canada (predominantly French-speaking) and Upper Canada (for English loyalists), establishing elected assemblies in each; in Lower Canada, the French majority ensured dominance of proceedings in French, preserving legislative autonomy over local affairs like property and religion despite an appointed British executive council.[19] Adaptation manifested in the emergence of a francophone professional elite—notaires, avocats, and priests—who navigated British criminal law while advocating for customary rights through petitions to London, as seen in delegations lobbying for expanded civil liberties in the 1770s and 1780s.[24] By 1825, Lower Canada's census recorded 563,401 inhabitants, over 90% French Canadian by descent, underscoring demographic vitality amid sparse British influx (numbering under 20,000 in the province), which concentrated in urban Montreal rather than diluting rural strongholds. This period's survival tactics—clinging to Church-mediated cohesion, leveraging imperial concessions, and exploiting numeric superiority—forestalled assimilation until economic strains presaged later conflicts, with the French language entrenched in 80% of Lower Canada's households by the 1830s.[25]Expansion, Nationalism, and Industrialization (1840–1960)

Following the Act of Union in 1840, which merged Upper and Lower Canada, French Canadians experienced rapid demographic expansion driven by high fertility rates exceeding 7 children per woman in the mid-19th century, leading to a population increase from approximately 670,000 in 1844 to over 1.6 million by 1901 in Quebec alone.[26] This growth, fueled by natural increase rather than immigration from France, created land shortages in rural areas and prompted large-scale seasonal and permanent migration, particularly to New England textile mills where French Canadians formed enclaves comprising up to 30% of the workforce in states like Massachusetts by 1900.[27] Between 1840 and 1930, roughly 900,000 French Canadians emigrated to the United States, though about half returned, contributing to cultural diffusion while exposing communities to industrial labor conditions and English-language dominance.[27] Industrialization transformed Quebec's economy from agrarian self-sufficiency to manufacturing dependence, beginning modestly in the 1840s with small craft-based operations and accelerating after 1870 as tariffs protected nascent industries like textiles and lumber processing.[28] By 1900, Montreal emerged as Canada's industrial hub, with French Canadian workers shifting to urban factories powered increasingly by hydroelectricity after 1900, replacing steam engines and enabling growth in sectors such as pulp and paper; factory employment rose from under 40 establishments in 1851 to thousands by the early 20th century, drawing rural migrants and fostering labor unions amid exploitative conditions.[28] This shift, dominated by anglophone capital ownership, widened economic disparities, as French Canadians occupied low-skill roles while elites like the Catholic Church invested in survivance institutions to counter assimilation pressures from urbanization, which concentrated 60% of Quebec's population in cities by 1960.[29] French Canadian nationalism during this era emphasized cultural and religious preservation over territorial separatism, manifesting as conservative ultramontanism that allied with the Church to resist British liberal individualism and promote a distinct Catholic, agrarian identity against encroaching industrialization.[30] Influenced by figures like Henri Bourassa, who opposed conscription in World War I to safeguard demographic survival, this nationalism viewed economic modernization as a threat to traditional family structures and language, leading to movements like the Ligue Nationaliste in 1903 advocating economic autonomy through French-owned enterprises.[30] By the mid-20th century, amid two world wars and the Great Depression—which hit Quebec's export-dependent industries hard, with unemployment reaching 30% in 1933—nationalism evolved to critique anglophone economic control, as articulated in Abbé Lionel Groulx's writings promoting a "French Canada first" ethos, though it remained deferential to clerical authority until the 1950s.[31] This period's nationalism prioritized institutional survival, with the Church controlling education and social services to maintain cohesion amid migration and industrial flux, averting widespread assimilation despite pressures from English-majority institutions.[30]Quiet Revolution, Secularization, and Contemporary Challenges (1960–Present)

The Quiet Revolution commenced with the election of Jean Lesage's Liberal government on June 22, 1960, marking a shift from conservative, church-influenced governance under Maurice Duplessis to rapid modernization and state-led reforms in Quebec.[32] Key initiatives included the creation of the Ministry of Education in 1964, which centralized and secularized schooling by wresting control from the Catholic Church, previously responsible for nearly all francophone education; by the decade's end, public enrollment surged as vocational and higher education expanded to address high illiteracy rates among youth, with two-thirds of young adults lacking high school diplomas in 1960.[33] Similarly, the Ministry of Social Affairs and Health centralized welfare and hospital services, reducing clerical dominance in healthcare, where the Church had operated most institutions. Economic nationalism peaked with the 1962 nationalization of private hydroelectric firms, expanding Hydro-Québec's capacity from regional to province-wide by May 1, 1963, through acquisitions that harnessed resources like the Manicouagan River for industrial growth.[34] These reforms fostered a Québécois welfare state, emphasizing state intervention over traditional agrarian and clerical conservatism, though Lesage's government fell in 1966 amid fiscal strains from expanded borrowing.[35] Secularization accelerated during this period, eroding the Catholic Church's longstanding authority over French Canadian social life, which had enforced high birth rates and cultural isolation until the mid-20th century. Pre-1960, weekly Mass attendance among Quebec Catholics reached 88%, with the Church controlling education, hospitals, and charities; by the 1950s, irregular attendance had risen to 40%, signaling early disaffection amid urbanization.[36] Post-reforms, state assumption of these roles marginalized clerical influence, contributing to plummeting religiosity: monthly attendance fell from 48% in 1986 to 17% by 2011, while weekly Mass participation among Quebec Catholics dropped to 2% by the 2020s, far below the 15-25% national average.[37] [38] This shift correlated with fertility collapse, as Quebec's total fertility rate (TFR), exceeding Canada's until 1960, plunged from around 4 children per woman in the 1950s to below 2 by 1971, reflecting delayed marriage, contraception access, and women's workforce entry amid secular individualism.[39] By 2022, Quebec's TFR hovered at 1.3-1.4, sustaining population stagnation without immigration.[40] The Revolution's nationalist undercurrents birthed the Parti Québécois (PQ) in 1968, founded by René Lévesque to advocate sovereignty-association, blending independence with economic ties to Canada; the PQ won power in 1976, enacting Charter of the French Language (Bill 101) on August 26, 1977, mandating French as the sole public language for business, signage, and education for non-Anglophone immigrants to counter perceived anglophone economic dominance.[41] [42] Sovereignty peaked with referendums: the 1980 vote on negotiating sovereignty-association failed 59.56% to 40.44% on May 20, amid economic fears and federalist campaigns.[43] The 1995 referendum, offering "sovereignty with partnership," lost narrowly 50.58% to 49.42% on October 30, by fewer than 55,000 votes, exacerbated by federal interventions and Quebec's fiscal deficits.[44] Contemporary challenges for French Canadians center on cultural survival amid demographic pressures and identity erosion. Quebec's below-replacement fertility, persisting since the 1970s, has heightened reliance on immigration, yet Bill 101's francization requirements clash with influxes of non-French speakers—over 50% of Montreal immigrants by the 2010s speak neither French nor English primarily—diluting francophone majorities and straining language assimilation.[45] Sovereigntist fervor waned post-1995, with polls by 2025 showing two-thirds of Quebecers uninterested in renewed referendums, shifting focus to provincial autonomy under coalitions like the Coalition Avenir Québec.[46] Outside Quebec, French Canadian communities face assimilation, with francophone populations declining relative to English speakers due to intermarriage and mobility, though enclaves in New Brunswick and Ontario maintain vitality via bilingual policies. Economic integration persists as a tension, with francophones achieving parity in incomes but grappling with globalization's anglophone tilt, underscoring causal links between secular individualism, low natality, and existential threats to distinct French Canadian continuity.[47]Demographics and Geography

Population Statistics and Trends in Canada

In the 2021 Census of Population, 906,315 individuals in Canada self-identified "French Canadian" as an ethnic or cultural origin, accounting for 2.5% of the national population of 36,991,981.[48] A broader category, "French, n.o.s.," was reported by 3,985,945 people, or 11.0%, reflecting the multifaceted nature of self-reported ancestries where multiple origins can be selected.[49] Estimates of those claiming some French-Canadian ancestry or heritage reach approximately 7 million, concentrated primarily in Quebec where they form the demographic core. These figures underscore self-identification's variability, influenced by generational distance from origins and intermarriage, rather than strict genealogical continuity. Geographically, over 85% of French Canadians reside in Quebec, comprising the majority of the province's non-immigrant population of about 8.7 million, with significant minorities in New Brunswick (Acadian communities), Ontario, and Manitoba. In Quebec, 588,810 reported "French Canadian" specifically, though many more align with Québécois identity, which overlaps culturally and historically.[50] Outside Quebec, pockets persist in eastern Ontario and the Maritimes, but numbers are smaller and more dispersed, with Ontario hosting around 500,000 of French descent amid a larger English-majority context. Historically, French Canadians represented 30-40% of Canada's population in the 19th century, descending from New France settlers who grew rapidly through high fertility until the mid-20th century.[51] Absolute numbers have increased with overall population growth, yet their relative share has declined to about 15-20% due to differential fertility rates—French Canadian birth rates fell below replacement level (around 1.4-1.6 children per woman in Quebec by the 2020s) earlier than some groups—and non-French immigration comprising over 80% of recent inflows.[51] Assimilation accelerates the trend outside Quebec, where intermarriage rates exceed 50% in some communities, leading to linguistic and cultural shift toward English dominance and diluted ethnic identification in subsequent generations.[42] In Quebec, the Francophone proportion dropped from 82.5% post-World War II to under 80% by 2021, driven by immigration from non-French sources and urban concentration favoring bilingualism.[51] Projections indicate further relative decline without policy interventions, as low native fertility and assimilation counteract modest French-speaking immigration targets (currently 4.4% of economic immigrants).[52] These dynamics reflect causal factors like economic incentives for English acquisition and demographic momentum from historical patterns, rather than isolated cultural preferences.Communities in the United States

French Canadian migration to the United States occurred primarily between 1840 and 1930, driven by economic pressures in Quebec such as depleted farmland and limited opportunities, alongside demand for labor in New England's burgeoning textile mills and factories.[53] Approximately one million individuals emigrated during this period, with many settling in industrial centers to work in cotton mills, where French Canadians comprised 44 percent of the workforce by 1900.[54] About half eventually returned to Canada, but the remainder established enduring communities, particularly in states like Massachusetts, Maine, New Hampshire, Rhode Island, and Vermont.[53] These communities formed ethnic enclaves in mill towns, including Lowell and Holyoke in Massachusetts, Manchester in New Hampshire, Lewiston-Auburn and Biddeford in Maine, and Woonsocket in Rhode Island.[55] Northern Maine's St. John River Valley hosted Acadian descendants displaced earlier by British expulsion, maintaining distinct cultural practices alongside later industrial migrants.[56] Franco-Americans initially preserved their language, Catholicism, and family-oriented social structures through parish-based institutions and mutual aid societies, resisting rapid assimilation despite nativist opposition portraying them as unassimilable due to their attachment to French and faith.[54] As of the 2020 Census, approximately 1.63 million Americans reported French Canadian ancestry, concentrated in New England where it constitutes significant shares of local populations, such as 25 percent in Maine, 24.5 percent in New Hampshire, and 23.9 percent in Vermont based on earlier surveys reflecting persistent demographic patterns.[57] [58] Assimilation accelerated post-World War II through intermarriage, English-language dominance in education and employment, and military service, which exposed individuals to broader American norms and contributed to identity dilution.[59] Today, while overt cultural markers have faded— with French speakers among ancestry holders now a minority—pockets of heritage persist in bilingual programs, festivals, and organizations like the Franco-American Centre in Manchester, New Hampshire.[60]Genetic Studies and Cultural Assimilation Patterns

French Canadians, particularly those in Quebec, exhibit a pronounced founder effect stemming from an initial settler population of approximately 8,500 individuals who arrived primarily from France between 1608 and 1760, leading to reduced genetic diversity and elevated frequencies of certain rare variants compared to the broader European population.[61] This bottleneck effect is amplified in isolated regions like Saguenay–Lac-Saint-Jean, where a "triple founder effect"—involving serial migrations and endogamy—has resulted in higher prevalences of hereditary disorders such as familial hypercholesterolemia and certain neuromuscular conditions.[62][5] Genome-wide studies confirm that contemporary French Canadian genetic structure reflects not only ancestral French regional contributions but also post-settlement isolation and local admixture, with principal component analyses distinguishing Quebec subpopulations from metropolitan French cohorts due to drift and selection pressures.[63] Autosomal DNA analyses indicate that French Canadians derive over 90% of their ancestry from Western European sources, predominantly French, with average Native American admixture estimated at 0.5–2% provincially, though higher in eastern Quebec and Acadian-descended groups due to historical intermarriages in the 17th–18th centuries.[61] Y-chromosome and mtDNA haplogroups align closely with pre-modern French distributions—e.g., R1b dominating paternal lines and H subclades in maternal lines—underscoring limited non-European paternal input, while maternal lines show sporadic Indigenous signals from early fur trade unions.[64] These patterns facilitate disease gene mapping, as seen in enriched rare coding variants for conditions like inflammatory bowel disease in founder cohorts.[65] Peer-reviewed genetic research, often leveraging Quebec's genealogical records, highlights how this homogeneity enables causal variant identification but also raises ethical concerns in consanguinity-linked studies, with data from biobanks like CARTaGENE providing robust empirical validation over self-reported ancestry claims.[66] Cultural assimilation patterns among French Canadians diverge sharply by geography, with Quebec's institutional safeguards—such as language immersion policies and provincial autonomy—sustaining linguistic and ethnic cohesion, evidenced by over 80% French monolingualism in the province as of 2021 censuses, in contrast to rapid erosion elsewhere.[67] Outside Quebec, in anglophone Canada and the United States, assimilation accelerated post-1840 migrations, where approximately 1 million French Canadians relocated to New England industrial centers between 1865 and 1930, initially forming enclave communities that preserved Catholicism and endogamy but yielded to intergenerational language shift, with second- and third-generation Franco-Americans showing educational and occupational convergence to Anglo norms by the mid-20th century.[68][59] This assimilation was hastened by factors like compulsory English schooling, World War I/II military integration, and economic incentives, resulting in Franco-American identity dilution—e.g., French-language retention dropping below 20% by the 1980s in New England—while Quebec's nationalist movements post-1960 reinforced resistance, maintaining distinct family structures and fertility rates higher than Canadian averages until recent secular trends.[69] Acadian subgroups, dispersed after 1755 expulsions, display intermediate patterns: stronger cultural retention in Maritime provinces via folklore and bilingualism but partial anglicization in Louisiana Cajuns, where French creolization blended with Anglo influences.[70] Empirical metrics from census data and ethnographic surveys indicate that geographic proximity to Quebec cores inversely correlates with assimilation rates, with urban-rural divides further modulating outcomes: rural isolates preserved patois dialects longer, mirroring genetic endogamy's role in heritage continuity.[27] These dynamics underscore causal linkages between policy, migration, and identity persistence, with U.S. Franco groups facing higher intermarriage rates (over 70% exogamy by 1950) than Quebec's 20–30%, per historical demography.[71]Language

Linguistic Characteristics and Variants

Canadian French, spoken by the majority of French Canadians, diverged from 17th- and 18th-century northern and western French dialects brought by settlers to New France, evolving independently after 1763 due to geographic isolation and English linguistic dominance. This resulted in a conservative retention of archaic features alongside innovations from English contact and substrate influences, distinguishing it from Standard French.[72] Phonologically, Quebec French—the predominant variety—preserves more oral-nasal vowel contrasts than Standard French, where mergers occurred, such as maintaining distinct /a/ and /ɑ/ in pairs like pâte and patte. High vowels (/i/, /y/, /u/) are often laxed to [ɪ], [ʏ], [ʊ], as in facile pronounced [fa.sɪl] rather than [fa.sil]; diphthongization affects mid vowels, e.g., frère as [frɛjr] versus [frɛʁ].[73] Consonants exhibit affrication of dentals before high front vowels, yielding [tsi.ʁe] for tirer instead of [ti.ʁe], while nasal vowels like /ã/ remain less open, sometimes approaching [ɛ̃]. Intonation patterns are flatter, lacking the rising contour typical of Standard French yes/no questions.[73] Lexically, Canadian French retains 17th-century archaisms absent or obsolete in France, such as maganer (to damage or spoil) or bouleau (birch tree, from Gaulish substrate), reflecting rural and agricultural origins.[73] [74] Anglicisms are prevalent due to bilingual contexts, including le fun (fun), jobber (to work odd jobs), and calques like checker (to check); regionalisms include tuque (knit cap) or dépanneur (convenience store). Syntax shows minor divergences, such as periphrastic constructions for emphasis, but aligns closely with Standard French in formal registers.[74] Within Quebec, variants range from formal français québécois standard to informal joual, a working-class sociolect prominent in mid-20th-century literature and media, marked by phonetic reductions (e.g., elision of /ʁ/), slang-heavy lexicon with anglicisms and archaisms, and stable rural phonetic traits like exaggerated nasality.[74] Northern Quebec varieties are more nasal and relaxed (e.g., peut-être as [pøt.tʁə]), while urban Montreal and Quebec City speech approaches standard norms in educated contexts. Acadian French, used by French Canadians in New Brunswick, Nova Scotia, and Prince Edward Island, draws from western French dialects, featuring voiced fricatives (/ʒ/ for /ʃ/), th-stopping (/tʃ/ for /θ/ in loanwords), and vocabulary tied to maritime history, such as distinct terms for seafood or navigation.[72] [73] Franco-Ontarian French, in eastern Ontario, blends Quebec influences with local English borrowings, showing hybrid phonological traits like variable vowel laxing. Smaller enclaves, such as Brayon French along the Quebec-New Brunswick border, exhibit transitional features between Quebec and Acadian forms. These variants persist despite standardization efforts, with mutual intelligibility high but regional markers signaling identity.[72]Preservation Policies and Legal Frameworks

The federal Official Languages Act of 1969, revised in 1985 and modernized through Bill C-13 receiving royal assent on June 20, 2023, establishes English and French as co-official languages with equal status in Parliament, federal institutions, and the provision of services to the public.[75] It mandates bilingualism in federal courts, communications, and supports the vitality of official language minority communities, including French-speaking populations outside Quebec, by promoting positive measures for their development and prohibiting discrimination based on language.[76] Bill C-13 specifically addresses the demographic decline of French by requiring federally regulated private businesses—such as banks and airlines—to actively offer French services where warranted, enhancing substantive equality over formal parity and empowering the Commissioner of Official Languages with new investigative and remedial powers.[77][78] In Quebec, where the majority of French Canadians reside, the Charter of the French Language (Bill 101), adopted on August 26, 1977, designates French as the sole official language and the common public language, requiring its predominant use in legislation, judicial proceedings, commercial signage, contracts, and education.[79] It mandates French instruction for children of immigrants unless they qualify for English eligibility based on parental attendance at English schools, aiming to counter anglicization trends post-Quiet Revolution.[80] Amendments via Bill 96, enacted May 24, 2022, and phased in through 2025, expand francization obligations to companies with 25 or more Quebec employees (lowered from 50), enforce French as the dominant language on product packaging and websites, and extend requirements to federally regulated entities operating in the province, with non-compliance fines up to C$30,000 per violation.[81][82] These reforms respond to data showing French's share of Quebec's population dipping below 80% by 2021, prioritizing preservation amid immigration-driven linguistic shifts.[83] Outside Quebec, policies for French Canadian minorities, including Acadians, vary by province but align with federal obligations under section 41 of the Official Languages Act for community enhancement. New Brunswick, officially bilingual since the 1969 Official Languages Act, provides French services province-wide via the 1981 French Language Services Regulation, supporting Acadian schools and media.[84] Ontario's French Language Services Act of 1986 guarantees services in 25 designated francophone-heavy regions, covering health, education, and courts, while Manitoba and Nova Scotia offer targeted protections through legislation for French education and services in francophone areas.[84] These frameworks, though less stringent than Quebec's, have sustained minority French vitality, with New Brunswick hosting Canada's only constitutionally bilingual province and Acadian communities comprising about 30% of its population as of 2021.[85]Debates on Language Decline and Immigration Impacts

In Quebec, the primary hub of French Canadian communities, debates over French language decline center on empirical indicators from census data showing a gradual erosion in the relative dominance of French speakers. According to the 2021 Canadian Census, the proportion of Quebec residents reporting French as their mother tongue decreased to 74.8% from 77.1% in 2016, while the share speaking French most often at home fell to 77.5% from 78.7%.[86] This trend persists despite protective legislation like the Charter of the French Language (Bill 101, enacted 1977), which mandates French as the language of public education for non-Anglophone children and business operations. Critics, including Quebec's Commissioner of Official Languages, attribute the decline to structural factors such as low francophone fertility rates (around 1.4 children per woman in 2021) and urban linguistic shifts, particularly in Montreal where English-French bilingualism rose to 56.5% by 2021, facilitating code-switching and potential assimilation toward English.[87][88] Immigration exacerbates these concerns, as Quebec's population growth—projected to rely on 50,000–60,000 annual immigrants through 2030—introduces non-francophone newcomers who often enter as allophones (neither French nor English mother tongue), comprising 11.7% of Quebec's population in 2021, up from 9.9% in 2011.[88] While Quebec's selection criteria prioritize French proficiency (with about 80% of economic immigrants required to demonstrate it since reforms in the 2010s), federal streams account for roughly half of arrivals, many from English-dominant or non-Romance language backgrounds, leading to debates over integration efficacy. Proponents of stricter controls, such as the Coalition Avenir Québec government, argue that without enhanced language requirements—like those in Bill 96 (2022), which extends French mandates to temporary workers and extends cut-off ages for English schooling—immigrants and their descendants disproportionately adopt English for economic mobility, evidenced by microsimulation models projecting French's share in Quebec dropping below 70% by 2051 under high immigration scenarios without full linguistic assimilation.[89][90] Conversely, economic analyses contend that vitality stems more from prosperity than coercion, noting pre-Bill 101 upticks in immigrant enrollment in French schools driven by opportunity, and warn that capping immigration could shrink Quebec's labor force amid an aging demographic.[91] Outside Quebec, French Canadian minorities face amplified decline, with francophone populations in provinces like Ontario and New Brunswick shrinking in absolute terms (e.g., -1.3% for French-only speakers in New Brunswick from 2016–2021) due to out-migration and intermarriage, compounded by federal immigration favoring English contexts.[92] These patterns fuel broader francophone advocacy for immigration targets allocating at least 8–12% to francophone minority communities outside Quebec, though data indicate limited retention, as second-generation immigrants often prioritize English.[93] Overall, while policies have stabilized absolute numbers of French speakers (up 3.9% in Quebec from 2001–2021), the relative decline underscores causal tensions between demographic replenishment and cultural preservation, with no consensus on optimal immigration thresholds to halt erosion without economic stagnation.[92]Religion and Social Values

Historical Catholicism and Clerical Influence