Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Astronomical object

View on WikipediaAn astronomical object, celestial object, stellar object or heavenly object is a naturally occurring physical entity, association, or structure that exists within the observable universe.[1] In astronomy, the terms object and body are often used interchangeably. However, an astronomical body, celestial body or heavenly body is a single, tightly bound, contiguous physical object, while an astronomical or celestial object admits a more complex, less cohesively bound structure, which may consist of multiple bodies or even other objects with substructures.

Examples of astronomical objects include planetary systems, star clusters, nebulae, and galaxies, while asteroids, moons, planets, and stars are astronomical bodies. A comet may be identified as both a body and an object: It is a body when referring to the frozen nucleus of ice and dust, and an object when describing the entire comet with its diffuse coma and tail.

History

[edit]According to NASA astrophysicists, early astronomical objects began to emerge plausibly 13.6 billion years ago, roughly 200 million years after the Big Bang formed the early universe. Over time, light was left from gravity to fuse into the first stars and galaxies.[2]

Astronomical objects such as stars, planets, nebulae, asteroids and comets have been observed for thousands of years, although early cultures thought of these bodies as deities. These early cultures found the movements of the bodies very important as they used these objects to help navigate over long distances, tell between the seasons, and to determine when to plant crops. During the Middle Ages, cultures began to study the movements of these bodies more closely. Several astronomers of the Middle East began to make detailed descriptions of stars and nebulae, and would make more accurate calendars based on the movements of these stars and planets. In Europe, astronomers focused more on devices to help study the celestial objects and creating textbooks, guides, and universities to teach people more about astronomy.

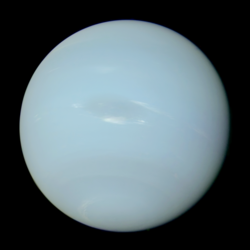

During the Scientific Revolution, in 1543, Nicolaus Copernicus's heliocentric model was published. This model described the Earth, along with all of the other planets as being astronomical bodies which orbited the Sun located in the center of the Solar System. Johannes Kepler discovered Kepler's laws of planetary motion, which are properties of the orbits that the astronomical bodies shared; this was used to improve the heliocentric model. In 1584, Giordano Bruno proposed that all distant stars are their own suns, being the first in centuries to suggest this idea. Galileo Galilei was one of the first astronomers to use telescopes to observe the sky, in 1610 he observed the four largest moons of Jupiter, now named the Galilean moons. Galileo also made observations of the phases of Venus, craters on the Moon, and sunspots on the Sun. Astronomer Edmond Halley was able to successfully predict the return of Halley's Comet, which now bears his name, in 1758. In 1781, Sir William Herschel discovered the new planet Uranus, being the first discovered planet not visible by the naked eye.

In the 19th and 20th centuries, new technologies and scientific innovations allowed scientists to greatly expand their understanding of astronomy and astronomical objects. Larger telescopes and observatories began to be built and scientists began to print images of the Moon and other celestial bodies on photographic plates. New wavelengths of light unseen by the human eye were discovered, and new telescopes were made that made it possible to see astronomical objects in other wavelengths of light. Joseph von Fraunhofer and Angelo Secchi pioneered the field of spectroscopy, which allowed them to observe the composition of stars and nebulae, and many astronomers were able to determine the masses of binary stars based on their orbital elements. Computers began to be used to observe and study massive amounts of astronomical data on stars, and new technologies such as the photoelectric photometer allowed astronomers to accurately measure the color and luminosity of stars, which allowed them to predict their temperature and mass. In 1913, the Hertzsprung–Russell diagram was developed by astronomers Ejnar Hertzsprung and Henry Norris Russell independently of each other, which plotted stars based on their luminosity and color and allowed astronomers to easily examine stars. It was found that stars commonly fell on a band of stars called the main-sequence stars on the diagram. A refined scheme for stellar classification was published in 1943 by William Wilson Morgan and Philip Childs Keenan based on the Hertzsprung–Russell diagram. Astronomers also began debating whether other galaxies existed beyond the Milky Way, these debates ended when Edwin Hubble identified the Andromeda nebula as a different galaxy, along with many others far from the Milky Way.

Galaxy and larger

[edit]The universe can be viewed as having a hierarchical structure.[3] At the largest scales, the fundamental component of assembly is the galaxy. Galaxies are organized into groups and clusters, often within larger superclusters, that are strung along great filaments between nearly empty voids, forming a web that spans the observable universe.[4]

Galaxies have a variety of morphologies, with irregular, elliptical and disk-like shapes, depending on their formation and evolutionary histories, including interaction with other galaxies, which may lead to a merger.[5] Disc galaxies encompass lenticular and spiral galaxies with features, such as spiral arms and a distinct halo. At the core, most galaxies have a supermassive black hole, which may result in an active galactic nucleus. Galaxies can also have satellites in the form of dwarf galaxies and globular clusters.[6]

Within a galaxy

[edit]The constituents of a galaxy are formed out of gaseous matter that assembles through gravitational self-attraction in a hierarchical manner. At this level, the resulting fundamental components are the stars, which are typically assembled in clusters from the various condensing nebulae.[7] The great variety of stellar forms are determined almost entirely by the mass, composition and evolutionary state of these stars. Stars may be found in multi-star systems that orbit about each other in a hierarchical organization. A planetary system and various minor objects such as asteroids, comets and debris, can form in a hierarchical process of accretion from the protoplanetary disks that surround newly formed stars.

The various distinctive types of stars are shown by the Hertzsprung–Russell diagram (H–R diagram)—a plot of absolute stellar luminosity versus surface temperature. Each star follows an evolutionary track across this diagram. If this track takes the star through a region containing an intrinsic variable type, then its physical properties can cause it to become a variable star. An example of this is the instability strip, a region of the H-R diagram that includes Delta Scuti, RR Lyrae and Cepheid variables.[8] The evolving star may eject some portion of its atmosphere to form a nebula, either steadily to form a planetary nebula or in a supernova explosion that leaves a remnant. Depending on the initial mass of the star and the presence or absence of a companion, a star may spend the last part of its life as a compact object; either a white dwarf, neutron star, or black hole.

Shape

[edit]

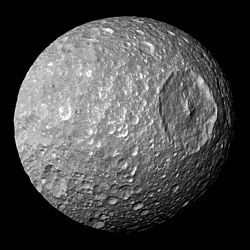

The IAU definitions of planet and dwarf planet require that a Sun-orbiting astronomical body has undergone the rounding process to reach a roughly spherical shape, an achievement known as hydrostatic equilibrium. The same spheroidal shape can be seen on smaller rocky planets like Mars to gas giants like Jupiter.

Any natural Sun-orbiting body that has not reached hydrostatic equilibrium is classified by the IAU as a small Solar System body (SSSB). These come in many non-spherical shapes which are lumpy masses accreted haphazardly by in-falling dust and rock; not enough mass falls in to generate the heat needed to complete the rounding. Some SSSBs are just collections of relatively small rocks that are weakly held next to each other by gravity but are not actually fused into a single big bedrock. Some larger SSSBs are nearly round but have not reached hydrostatic equilibrium. The small Solar System body 4 Vesta is large enough to have undergone at least partial planetary differentiation.

Stars like the Sun are also spheroidal due to gravity's effects on their plasma, which is a free-flowing fluid. Ongoing stellar fusion is a much greater source of heat for stars compared to the initial heat released during their formation.

Categories by location

[edit]The table below lists the general categories of bodies and objects by their location or structure.

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Task Group on Astronomical Designations from IAU Commission 5 (April 2008). "Naming Astronomical Objects". International Astronomical Union (IAU). Archived from the original on 2 August 2010. Retrieved 4 July 2010.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ "The Early Universe". NASA.

- ^ Narlikar, Jayant V. (1996). Elements of Cosmology. Universities Press. ISBN 81-7371-043-0.

- ^ Smolin, Lee (1998). The life of the cosmos. Oxford University Press US. p. 35. ISBN 0-19-512664-5.

- ^ Buta, Ronald James; Corwin, Harold G.; Odewahn, Stephen C. (2007). The de Vaucouleurs atlas of galaxies. Cambridge University Press. p. 301. ISBN 978-0-521-82048-6.

- ^ Hartung, Ernst Johannes (1984-10-18). Astronomical Objects for Southern Telescopes. CUP Archive. ISBN 0521318874. Retrieved 13 February 2017.

- ^ Elmegreen, Bruce G. (January 2010). "The nature and nurture of star clusters". Star clusters: basic galactic building blocks throughout time and space, Proceedings of the International Astronomical Union, IAU Symposium. Vol. 266. pp. 3–13. arXiv:0910.4638. Bibcode:2010IAUS..266....3E. doi:10.1017/S1743921309990809.

- ^ Hansen, Carl J.; Kawaler, Steven D.; Trimble, Virginia (2004). Stellar interiors: physical principles, structure, and evolution. Astronomy and astrophysics library (2nd ed.). Springer. p. 86. ISBN 0-387-20089-4.

External links

[edit]- SkyChart, Sky & Telescope at the Library of Congress Web Archives (archived 2005-06-13)

- Monthly skymaps for every location on Earth. Archived 2007-09-13 at the Wayback Machine.