Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Ruta graveolens

View on Wikipedia

| Common rue | |

|---|---|

| |

| Common rue in flower | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Plantae |

| Clade: | Tracheophytes |

| Clade: | Angiosperms |

| Clade: | Eudicots |

| Clade: | Rosids |

| Order: | Sapindales |

| Family: | Rutaceae |

| Genus: | Ruta |

| Species: | R. graveolens

|

| Binomial name | |

| Ruta graveolens | |

| |

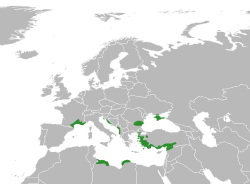

Ruta graveolens, commonly known as rue, common rue or herb-of-grace, is a species of the genus Ruta grown as an ornamental plant and herb. It is native to the Mediterranean. It is grown throughout the world in gardens, especially for its bluish leaves, and sometimes for its tolerance of hot and dry soil conditions. It is also cultivated as a culinary herb, and to a lesser extent as an insect repellent and incense.

Etymology

[edit]The specific epithet graveolens refers to the strong-smelling leaves.[1]

Description

[edit]

Rue is a woody, perennial shrub. Its leaves are oblong, blue green and arranged bipinnately with rounded leaflets; they release a strong aroma when they are bruised.[2]

The flowers are small with 4 to 5 dull yellow petals in cymes. The first flower in each cyme is pentamerous (five sepals, five petals, five stamens and five carpels. All the others are tetramerous (four of each part). They bear brown seed capsules when pollinated.[2]

Uses

[edit]Traditional use

[edit]This article is missing information about effectiveness and safety of traditional medical uses. (October 2021) |

In the ancient Roman world, the naturalists Pedanius Dioscorides and Pliny the Elder recommended that rue be combined with the poisonous shrub oleander to be drunk as an antidote to venomous snake bites.[3][4]

The refined oil of rue is an emmenagogue[5] and was cited by the Roman historian Pliny the Elder and Soranus as an abortifacient (inducing abortion).[6][7]

Culinary use

[edit]

Rue has a culinary use, but since it is bitter and gastric discomfort may be experienced by some individuals, it is used sparingly. Although used more extensively as a culinary herb in former times, it is not typically found in modern cuisine. Due to small amounts of toxins it contains, it must be used in small amounts, and should be avoided by pregnant women or women who have liver issues.

It has a variety of other culinary uses:

- It was used extensively in ancient Near Eastern and Roman cuisine (according to Ibn Sayyar al-Warraq and Apicius).

- Rue is used as a traditional flavouring in Greece and other Mediterranean countries.[1]

- In Istria (a region spanning Croatia and Slovenia), and in northern Italy, it is used to give a special flavour to grappa/rakia and most of the time a little branch of the plant can be found in the bottle. This is called grappa alla ruta.

- Seeds can be used for porridge.

- The bitter leaf can be added to eggs, cheese, fish, or mixed with damson plums and wine to produce a meat sauce.

- In Italy in Friuli-Venezia Giulia, the young branches of the plant are dipped in a batter, deep-fried in oil, and consumed with salt or sugar. They are also used on their own to aromatise a specific type of omelette.[8]

- Used in Old World beers as flavouring ingredient.[9]

- The rue that is widespread in Ethiopian culture is a different species, R. chalapensis.[10]

Other

[edit]Rue is also grown as an ornamental plant, both as a low hedge and so the leaves can be used in nosegays.

Most cats dislike the smell of it, and it can, therefore, be used as a deterrent to them (see also Plectranthus caninus).[citation needed]

Caterpillars of some subspecies of the butterfly Papilio machaon feed on rue, as well as other plants. The caterpillars of Papilio xuthus also feed readily on it.[11]

In Sephardic Jewish tradition, ruda is believed to possess protective qualities against malevolent forces, particularly the evil eye. It is often placed near vulnerable individuals, such as newborns, children, and mothers, to ward off evil.[12] Beyond its symbolic significance, ruda is valued for its medicinal properties. When combined with sugar, it is traditionally used to soothe eye discomfort and alleviate the symptoms of a mild cold. Additionally, inhaling ruda is thought to mitigate the effects of shock. Ruda's significance in Sephardic Jewish culture also extends to religious practices. During Yom Kippur, a Jewish holiday marked by fasting, Sephardic synagogues often pass ruda among congregants to revitalise them.[12]

Beyond the Sephardic tradition, Hasidic Jews also recognized the protective qualities of ruda. Hasidic Jews also were taught that rue should be placed into amulets to protect them from epidemics and plagues.[13] Other Hasidim rely on the works of a famous Baghdadi Kabbalist Yaakov Chaim Sofer who makes mention of the plant "ruda" (רודה) as an effective device against both black magic and the evil eye.[14]

It finds many household uses around the world as well. It is traditionally used in Central Asia as an insect repellent and room deodorizer.[clarification needed]

Toxicity

[edit]Rue is generally safe if consumed in small amounts as an herb to flavor food. Rue extracts are mutagenic and hepatotoxic.[5] Large doses can cause violent gastric pain, vomiting, liver damage, and death.[5] This is due to a variety of toxic compounds in the plant's sap. It is recommended to only use small amounts in food, and to not consume it excessively. It should be strictly avoided by pregnant women, as it can be an abortifacient and teratogen.[15]

Exposure to common rue, or herbal preparations derived from it, can cause severe phytophotodermatitis, which results in burn-like blisters on the skin.[16][17][18][19] The mechanism of action is currently unknown.[20]

Chemistry

[edit]

A series of furanoacridones and two acridone alkaloids (arborinine and evoxanthine) have been isolated from R. graveolens.[21] It also contains coumarins and limonoids.[22]

Cell cultures produce the coumarins umbelliferone, scopoletin, psoralen, xanthotoxin, isopimpinellin, rutamarin and rutacultin, and the alkaloids skimmianine, kokusaginine, 6-methoxydictamnine and edulinine.[23]

The ethyl acetate extract of R. graveolens leaves yields two furanocoumarins, one quinoline alkaloid and four quinolone alkaloids including graveoline.[24][25]

The chloroform extracts of the root, stem and leaf shows the isolation of the furanocoumarin chalepensin.[26]

The essential oil of R. graveolens contains two main constituents, undecan-2-one (46.8%) and nonan-2-one (18.8%).[27]

Symbolism

[edit]The bitter taste of its leaves led to rue being associated with the (etymologically unrelated) verb rue "to regret". Rue is well known for its symbolic meaning of regret and it has sometimes been called "herb-of-grace" in literary works. In mythology,[28] the basilisk, whose breath could cause plants to wilt and stones to crack, had no effect on rue. Weasels who were bitten by the basilisk would retreat and eat rue in order to recover and return to fight.

In the Bible

[edit]Rue is mentioned in the New Testament, Luke 11:42:

"But woe unto you, Pharisees! For ye tithe mint and rue and all manner of herbs".

In Jewish culture

[edit]Sephardic Jewish tradition has long valued ruda for its diverse applications in health, religious practices, and spiritual well-being. It was in the Ottoman Balkans, rather than Medieval Spain, that Sephardic Jews encountered ruda and adopted its associated traditions and beliefs.[12]

For Sephardic Jews, Ruda is believed to protect against the evil eye and is often placed near newborns, children, and mothers to ward off harm. It is also traditionally used for its healing properties; when combined with sugar, it can soothe eye discomfort. Inhaling ruda is thought to alleviate symptoms of shock.[12] During Yom Kippur, ruda is sometimes used in synagogues to revitalize fasting worshippers.[12]

In Sephardic culture, ruda also symbolizes affection and is incorporated into celebratory rituals such as bridal showers. This symbolism is also featured in the traditional Sephardic song "Una Matica de Ruda", a popular Ladino ballad sung by Sephardic Jews for centuries. It's a retelling of a 16th-century Spanish ballad, and depicts a conversation between a mother and daughter about love and marriage. The daughter receives a cluster of ruda from a suitor, while the mother warns her of the dangers of new love.[12]

In Lithuania

[edit]Rue is considered a national herb of Lithuania and it is the most frequently referenced herb in Lithuanian folk songs, as an attribute of young girls, associated with virginity and maidenhood. It was common in traditional Lithuanian weddings for only virgins to wear a rue (Lithuanian: rūta) at their wedding, a symbol to show their purity.

In Ukraine

[edit]Likewise, rue is prominent in Ukrainian folklore, songs and culture. In the Ukrainian folk song "Oi poli ruta, ruta" (O, rue, rue in the field), the girl regrets losing her virginity, reproaching the lover for "breaking the green hazel tree".[29] "Chervona Ruta" (Червона Рута—"Red Rue") is a song, written by Volodymyr Ivasyuk, a popular Ukrainian poet and composer. Pop singer Sofia Rotaru performed the song in 1971.

In Germany

[edit]Rue as heraldic charge (Crancelin) is used on the coats of arms of Saxony and Saxony-Anhalt.

In Shakespeare

[edit]It is one of the flowers distributed by the mad Ophelia in William Shakespeare's Hamlet (IV.5):

- "There's fennel for you, and columbines:

- there's rue for you; and here's some for me:

- we may call it herb-grace o' Sundays:

- O you must wear your rue with a difference..."

It is used by the clown Lavatch in All's Well That Ends Well (IV.5) to describe Helena and his regret at her apparent death:

- "she was the sweet marjoram of the salad, or rather, the herb of grace."

It was planted by the gardener in Richard II to mark the spot where the Queen wept upon hearing news of Richard's capture (III.4.104–105):

- "Here did she fall a tear, here in this place

- I'll set a bank of rue, sour herb of grace."

It is also given by the rusticated Perdita to her disguised royal father-in-law on the occasion of a sheep-shearing (Winter's Tale, IV.4):

- "For you there's rosemary and rue; these keep

- Seeming and savour all the winter long."

In other English literature

[edit]It is used by Michael in Milton's Paradise Lost to give Adam clear sight (11.414):

- "Then purg'd with euphrasy and rue

- The visual nerve, for he had much to see."

Rue is used by Gulliver in Gulliver's Travels (by Jonathan Swift) when he returns to England after living among the "Houyhnhnms". Gulliver can no longer stand the smell of the English Yahoos (people), so he stuffs rue or tobacco in his nose to block out the smell.

"I was at last bold enough to walk the street in his (Don Pedro's) company, but kept my nose well with rue, or sometimes with tobacco".

See also

[edit]- Ruta chalepensis or fringed rue, popular in Ethiopian cuisine

- Peganum harmala, an unrelated plant also known as "Syrian rue"

References

[edit]- ^ a b J. D. Douglas and Merrill C. Tenney Zondervan Illustrated Bible Dictionary, p. 1150, at Google Books

- ^ a b "Ruta graveolens". Plant Finder. Missouri Botanical Garden. 2022. Retrieved 16 December 2022.

- ^ Pliny the Elder. Natural History Book. p. Book 24, 90.

- ^ Pedanius Dioscorides. De Materia Medica. p. Book V, 42.

- ^ a b c "Rue". drugs.com.

- ^ Natural History Book XX Ch LI[full citation needed]

- ^ Nelson, Sarah E. (2009). "Persephone's Seeds: Abortifacients and Contraceptives in Ancient Greek Medicine and Their Recent Scientific Appraisal". Pharmacy in History. 51 (2): 57–69. JSTOR 41112420. PMID 20853553.

- ^ Ghirardini, Maria; Carli, Marco; Del Vecchio, Nicola; et al. (2007). "The importance of a taste. A comparative study on wild food plant consumption in twenty-one local communities in Italy". Journal of Ethnobiology and Ethnomedicine. 3: 22. doi:10.1186/1746-4269-3-22. PMC 1877798. PMID 17480214.

- ^ Spencer Hornsey, Ian (December 2003). "Chapter 3". A History of Beer and Brewing. Royal Society of Chemistry. p. 103. ISBN 978-0-854-04630-0.

- ^ "Ruta graveolens". Kew Plants of the World Online. Retrieved 21 June 2023.; "Ruta chalepensis". Kew Plants of the World Online. Retrieved 21 June 2023., compare distribution maps.

- ^ Dempster, J.P. (1995). "The ecology and conservation of Papilio machaon in Britain". In Pullin, Andrew S. (ed.). Ecology and Conservation of Butterflies (1st ed.). London: Chapman & Hall. pp. 137–149. ISBN 0412569701.

- ^ a b c d e f Stein, Sarah Abrevaya (2022). "The Queen of Herbs: A Plant's-Eye View of the Sephardic Diaspora". Jewish Quarterly Review. 112 (1): 119–138. doi:10.1353/jqr.2022.0004. ISSN 1553-0604.

- ^ This was taught by Rabbi Isaac of Komarno in his comments to Sefer Adam Yashar in the name of Rabbi Isaac Luria

- ^ https://www.sefaria.org/Kaf_HaChayim_on_Shulchan_Arukh%2C_Orach_Chayim.301.135?lang=bi[full citation needed]

- ^ Feng, Chris; Fay, Kathryn E.; Burns, Michele M. (2023). "Toxicities of herbal abortifacients". The American Journal of Emergency Medicine. 68: 42–46. doi:10.1016/j.ajem.2023.03.005. PMC 10192026. PMID 36924751.

- ^ Arias-Santiago, SA; Fernández-Pugnaire, MA; Almazán-Fernández, FM; Serrano-Falcón, C; Serrano-Ortega, S (2009). "Phytophotodermatitis due to Ruta graveolens prescribed for fibromyalgia". Rheumatology. 48 (11): 1401. doi:10.1093/rheumatology/kep234. PMID 19671699.

- ^ Furniss, D; Adams, T (2007). "Herb of grace: An unusual cause of phytophotodermatitis mimicking burn injury". Journal of Burn Care & Research. 28 (5): 767–769. doi:10.1097/BCR.0B013E318148CB82. PMID 17667834.

- ^ Eickhorst, K; Deleo, V; Csaposs, J (2007). "Rue the herb: Ruta graveolens–associated phytophototoxicity". Dermatitis. 18 (1): 52–55. doi:10.2310/6620.2007.06033. PMID 17303046.

- ^ Wessner, D; Hofmann, H; Ring, J (1999). "Phytophotodermatitis due to Ruta graveolens applied as protection against evil spells". Contact Dermatitis. 41 (4): 232. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0536.1999.tb06145.x. PMID 10515113. S2CID 45280728.

- ^ Naghibi Harat, Z.; Kamalinejad, M.; Sadeghi, M. R.; Sadeghipour, H. R.; Eshraghian, M. R. (2009-05-10). "A Review on Ruta graveolens L. Its Usage in Traditional Medicine and Modern Research Data". Journal of Medicinal Plants. 8 (30): 1–19.

- ^ Rethy, Borbala; Zupko, Istvan; Minorics, Renata; Hohmann, Judit; Ocsovszki, Imre; Falkay, George (2007). "Investigation of cytotoxic activity on human cancer cell lines of arborinine and furanoacridones isolated from Ruta graveolens". Planta Medica. 73 (1): 41–48. Bibcode:2007PlMed..73...41R. doi:10.1055/s-2006-951747. PMID 17109253. S2CID 260283678. INIST 18469419

- ^ Srivastava, S. D.; Srivastava, S. K.; Halwe, K. (1998). "New coumarins and limonoids of Ruta graveolens". Fitoterapia. 69 (1): 7–12. INIST 2179664

- ^ Steck, Warren; Bailey, B.K.; Shyluk, J.P.; Gamborg, O.L. (1971). "Coumarins and alkaloids from cell cultures of Ruta graveolens". Phytochemistry. 10 (1): 191–194. Bibcode:1971PChem..10..191S. doi:10.1016/S0031-9422(00)90269-3.

- ^ Oliva, Anna; Meepagala, Kumudini M.; Wedge, David E.; Harries, Dewayne; Hale, Amber L.; Aliotta, Giovanni; Duke, Stephen O. (2003). "Natural Fungicides from Ruta graveolens L. Leaves, Including a New Quinolone Alkaloid". Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry. 51 (4): 890–896. Bibcode:2003JAFC...51..890O. doi:10.1021/jf0259361. PMID 12568545.

- ^ Zobel, Alicja M.; Brown, Stewart A. (1988). "Determination of Furanocoumarins on the Leaf Surface of Ruta graveolens with an Improved Extraction Technique". Journal of Natural Products. 51 (5): 941–946. Bibcode:1988JNAtP..51..941Z. doi:10.1021/np50059a021. PMID 21401190.

- ^ Kong, Y.; Lau, C.; Wat, K.; Ng, K.; But, P.; Cheng, K.; Waterman, P. (2007). "Antifertility Principle of Ruta graveolens". Planta Medica. 55 (2): 176–8. doi:10.1055/s-2006-961917. PMID 2748734. S2CID 28529328.

- ^ De Feo, Vincenzo; De Simone, Francesco; Senatore, Felice (2002). "Potential allelochemicals from the essential oil of Ruta graveolens". Phytochemistry. 61 (5): 573–578. Bibcode:2002PChem..61..573D. doi:10.1016/s0031-9422(02)00284-4. PMID 12409025. INIST 13994117

- ^ Walsh, William Shepard; Garrison, William H.; Harris, Samuel R. (5 January 1888). "American Notes and Queries". Westminster Publishing Company – via Google Books.

- ^ Ukrainian folk songs. Oi u poli ruta, ruta (O, rue, rue in the field). (Ukrainian)

External links

[edit]- An uninviting but much-loved ruta article on the ruta graveolens in the ancient Roman world by the Nunc est bibendum Association

- Rue (Ruta graveolens L.) page from Gernot Katzer's Spice Pages