Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Function (mathematics)

View on Wikipedia| Function |

|---|

| x ↦ f (x) |

| History of the function concept |

| Types by domain and codomain |

| Classes/properties |

| Constructions |

| Generalizations |

| List of specific functions |

In mathematics, a function from a set X to a set Y assigns to each element of X exactly one element of Y.[1] The set X is called the domain of the function[2] and the set Y is called the codomain of the function.[3]

Functions were originally the idealization of how a varying quantity depends on another quantity. For example, the position of a planet is a function of time. Historically, the concept was elaborated with the infinitesimal calculus at the end of the 17th century, and, until the 19th century, the functions that were considered were differentiable (that is, they had a high degree of regularity). The concept of a function was formalized at the end of the 19th century in terms of set theory, and this greatly increased the possible applications of the concept.

A function is often denoted by a letter such as f, g or h. The value of a function f at an element x of its domain (that is, the element of the codomain that is associated with x) is denoted by f(x); for example, the value of f at x = 4 is denoted by f(4). Commonly, a specific function is defined by means of an expression depending on x, such as in this case, some computation, called function evaluation, may be needed for deducing the value of the function at a particular value; for example, if then

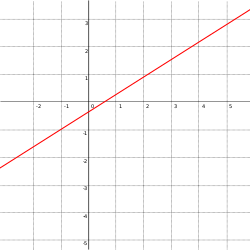

Given its domain and its codomain, a function is uniquely represented by the set of all pairs (x, f (x)), called the graph of the function, a popular means of illustrating the function.[note 1][4] When the domain and the codomain are sets of real numbers, each such pair may be thought of as the Cartesian coordinates of a point in the plane.

Functions are widely used in science, engineering, and in most fields of mathematics. It has been said that functions are "the central objects of investigation" in most fields of mathematics.[5]

The concept of a function has evolved significantly over centuries, from its informal origins in ancient mathematics to its formalization in the 19th century. See History of the function concept for details.

Definition

[edit]

A function f from a set X to a set Y is an assignment of one element of Y to each element of X. The set X is called the domain of the function and the set Y is called the codomain of the function.

If the element y in Y is assigned to x in X by the function f, one says that f maps x to y, and this is commonly written In this notation, x is the argument or variable of the function.

A specific element x of X is a value of the variable, and the corresponding element of Y is the value of the function at x, or the image of x under the function. The image of a function, sometimes called its range, is the set of the images of all elements in the domain.[6][7][8][9]

A function f, its domain X, and its codomain Y are often specified by the notation One may write instead of , where the symbol (read 'maps to') is used to specify where a particular element x in the domain is mapped to by f. This allows the definition of a function without naming. For example, the square function is the function

The domain and codomain are not always explicitly given when a function is defined. In particular, it is common that one might only know, without some (possibly difficult) computation, that the domain of a specific function is contained in a larger set. For example, if is a real function, the determination of the domain of the function requires knowing the zeros of f. This is one of the reasons for which, in mathematical analysis, "a function from X to Y " may refer to a function having a proper subset of X as a domain.[note 2] For example, a "function from the reals to the reals" may refer to a real-valued function of a real variable whose domain is a proper subset of the real numbers, typically a subset that contains a non-empty open interval. Such a function is then called a partial function.

A function f on a set S means a function from the domain S, without specifying a codomain. However, some authors use it as shorthand for saying that the function is f : S → S.

Formal definition

[edit]

The above definition of a function is essentially that of the founders of calculus, Leibniz, Newton and Euler. However, it cannot be formalized, since there is no mathematical definition of an "assignment". It is only at the end of the 19th century that the first formal definition of a function could be provided, in terms of set theory. This set-theoretic definition is based on the fact that a function establishes a relation between the elements of the domain and some (possibly all) elements of the codomain. Mathematically, a binary relation between two sets X and Y is a subset of the set of all ordered pairs such that and The set of all these pairs is called the Cartesian product of X and Y and denoted Thus, the above definition may be formalized as follows.

A function with domain X and codomain Y is a binary relation R between X and Y that satisfies the two following conditions:[10]

- For every in there exists in such that

- If and then

This definition may be rewritten more formally, without referring explicitly to the concept of a relation, but using more notation (including set-builder notation):

A function is formed by three sets (often as an ordered triple), the domain the codomain and the graph that satisfy the three following conditions.

A relation satisfying these conditions is called a functional relation.

The more usual terminology and notation can be derived from this formal definition as follows. Let be a function defined by a functional relation . For every in the domain of , the unique element of the codomain that is related to is denoted . If is this element, one writes commonly instead of or , and one says that " maps to ", " is the image by of ", or "the application of on gives ", etc.

Partial functions

[edit]Partial functions are defined similarly to ordinary functions, with the "total" condition removed. That is, a partial function from X to Y is a binary relation R between X and Y such that, for every there is at most one y in Y such that

Using functional notation, this means that, given either is in Y, or it is undefined.

The set of the elements of X such that is defined and belongs to Y is called the domain of definition of the function. A partial function from X to Y is thus an ordinary function that has as its domain a subset of X called the domain of definition of the function. If the domain of definition equals X, one often says that the partial function is a total function.

In several areas of mathematics, the term "function" refers to partial functions rather than to ordinary (total) functions. This is typically the case when functions may be specified in a way that makes difficult or even impossible to determine their domain.

In calculus, a real-valued function of a real variable or real function is a partial function from the set of the real numbers to itself. Given a real function its multiplicative inverse is also a real function. The determination of the domain of definition of a multiplicative inverse of a (partial) function amounts to compute the zeros of the function, the values where the function is defined but not its multiplicative inverse.

Similarly, a function of a complex variable is generally a partial function whose domain of definition is a subset of the complex numbers . The difficulty of determining the domain of definition of a complex function is illustrated by the multiplicative inverse of the Riemann zeta function: the determination of the domain of definition of the function is more or less equivalent to the proof or disproof of one of the major open problems in mathematics, the Riemann hypothesis.

In computability theory, a general recursive function is a partial function from the integers to the integers whose values can be computed by an algorithm (roughly speaking). The domain of definition of such a function is the set of inputs for which the algorithm does not run forever. A fundamental theorem of computability theory is that there cannot exist an algorithm that takes an arbitrary general recursive function as input and tests whether 0 belongs to its domain of definition (see Halting problem).

Multivariate functions

[edit]

A multivariate function, multivariable function, or function of several variables is a function that depends on several arguments. Such functions are commonly encountered. For example, the position of a car on a road is a function of the time travelled and its average speed.

Formally, a function of n variables is a function whose domain is a set of n-tuples.[note 3] For example, multiplication of integers is a function of two variables, or bivariate function, whose domain is the set of all ordered pairs (2-tuples) of integers, and whose codomain is the set of integers. The same is true for every binary operation. The graph of a bivariate surface over a two-dimensional real domain may be interpreted as defining a parametric surface, as used in, e.g., bivariate interpolation.

Commonly, an n-tuple is denoted enclosed between parentheses, such as in When using functional notation, one usually omits the parentheses surrounding tuples, writing instead of

Given n sets the set of all n-tuples such that is called the Cartesian product of and denoted

Therefore, a multivariate function is a function that has a Cartesian product or a proper subset of a Cartesian product as a domain.

where the domain U has the form

If all the are equal to the set of the real numbers or to the set of the complex numbers, one talks respectively of a function of several real variables or of a function of several complex variables.

Notation

[edit]There are various standard ways for denoting functions. The most commonly used notation is functional notation, which is the first notation described below.

Functional notation

[edit]The functional notation requires that a name is given to the function, which, in the case of a unspecified function is often the letter f. Then, the application of the function to an argument is denoted by its name followed by its argument (or, in the case of a multivariate functions, its arguments) enclosed between parentheses, such as in

The argument between the parentheses may be a variable, often x, that represents an arbitrary element of the domain of the function, a specific element of the domain (3 in the above example), or an expression that can be evaluated to an element of the domain ( in the above example). The use of an unspecified variable between parentheses is useful for defining a function explicitly such as in "let ".

When the symbol denoting the function consists of several characters and no ambiguity may arise, the parentheses of functional notation might be omitted. For example, it is common to write sin x instead of sin(x).

Functional notation was first used by Leonhard Euler in 1734.[11] Some widely used functions are represented by a symbol consisting of several letters (usually two or three, generally an abbreviation of their name). In this case, a roman type is customarily used instead, such as "sin" for the sine function, in contrast to italic font for single-letter symbols.

The functional notation is often used colloquially for referring to a function and simultaneously naming its argument, such as in "let be a function". This is an abuse of notation that is useful for a simpler formulation.

Arrow notation

[edit]Arrow notation defines the rule of a function inline, without requiring a name to be given to the function. It uses the ↦ arrow symbol, read as "maps to". For example, is the function which takes a real number as input and outputs that number plus 1. Again, a domain and codomain of is implied.

The domain and codomain can also be explicitly stated, for example:

This defines a function sqr from the integers to the integers that returns the square of its input.

As a common application of the arrow notation, suppose is a function in two variables, and we want to refer to a partially applied function produced by fixing the second argument to the value t0 without introducing a new function name. The map in question could be denoted using the arrow notation. The expression (read: "the map taking x to f of x comma t nought") represents this new function with just one argument, whereas the expression f(x0, t0) refers to the value of the function f at the point (x0, t0).

Index notation

[edit]Index notation may be used instead of functional notation. That is, instead of writing f (x), one writes

This is typically the case for functions whose domain is the set of the natural numbers. Such a function is called a sequence, and, in this case the element is called the nth element of the sequence.

The index notation can also be used for distinguishing some variables called parameters from the "true variables". In fact, parameters are specific variables that are considered as being fixed during the study of a problem. For example, the map (see above) would be denoted using index notation, if we define the collection of maps by the formula for all .

Dot notation

[edit]In the notation the symbol x does not represent any value; it is simply a placeholder, meaning that, if x is replaced by any value on the left of the arrow, it should be replaced by the same value on the right of the arrow. Therefore, x may be replaced by any symbol, often an interpunct " ⋅ ". This may be useful for distinguishing the function f (⋅) from its value f (x) at x.

For example, may stand for the function , and may stand for a function defined by an integral with variable upper bound: .

Specialized notations

[edit]There are other, specialized notations for functions in sub-disciplines of mathematics. For example, in linear algebra and functional analysis, linear forms and the vectors they act upon are denoted using a dual pair to show the underlying duality. This is similar to the use of bra–ket notation in quantum mechanics. In logic and the theory of computation, the function notation of lambda calculus is used to explicitly express the basic notions of function abstraction and application. In category theory and homological algebra, networks of functions are described in terms of how they and their compositions commute with each other using commutative diagrams that extend and generalize the arrow notation for functions described above.

Functions of more than one variable

[edit]In some cases the argument of a function may be an ordered pair of elements taken from some set or sets. For example, a function f can be defined as mapping any pair of real numbers to the sum of their squares, . Such a function is commonly written as and referred to as "a function of two variables". Likewise one can have a function of three or more variables, with notations such as , .

Other terms

[edit]| Term | Distinction from "function" |

|---|---|

| Map/Mapping | None; the terms are synonymous.[12] |

| A map can have any set as its codomain, while, in some contexts, typically in older books, the codomain of a function is specifically the set of real or complex numbers.[13] | |

| Alternatively, a map is associated with a special structure (e.g. by explicitly specifying a structured codomain in its definition). For example, a linear map.[14] | |

| Homomorphism | A function between two structures of the same type that preserves the operations of the structure (e.g. a group homomorphism).[15] |

| Morphism | A generalisation of homomorphisms to any category, even when the objects of the category are not sets (for example, a group defines a category with only one object, which has the elements of the group as morphisms; see Category (mathematics) § Examples for this example and other similar ones).[16] |

A function may also be called a map or a mapping, but some authors make a distinction between the term "map" and "function". For example, the term "map" is often reserved for a "function" with some sort of special structure (e.g. maps of manifolds). In particular map may be used in place of homomorphism for the sake of succinctness (e.g., linear map or map from G to H instead of group homomorphism from G to H). Some authors[14] reserve the word mapping for the case where the structure of the codomain belongs explicitly to the definition of the function.

Some authors, such as Serge Lang,[13] use "function" only to refer to maps for which the codomain is a subset of the real or complex numbers, and use the term mapping for more general functions.

In the theory of dynamical systems, a map denotes an evolution function used to create discrete dynamical systems. See also Poincaré map.

Whichever definition of map is used, related terms like domain, codomain, injective, continuous have the same meaning as for a function.

Specifying a function

[edit]Given a function , by definition, to each element of the domain of the function , there is a unique element associated to it, the value of at . There are several ways to specify or describe how is related to , both explicitly and implicitly. Sometimes, a theorem or an axiom asserts the existence of a function having some properties, without describing it more precisely. Often, the specification or description is referred to as the definition of the function .

By listing function values

[edit]On a finite set a function may be defined by listing the elements of the codomain that are associated to the elements of the domain. For example, if , then one can define a function by

By a formula

[edit]Functions are often defined by an expression that describes a combination of arithmetic operations and previously defined functions; such a formula allows computing the value of the function from the value of any element of the domain. For example, in the above example, can be defined by the formula , for .

When a function is defined this way, the determination of its domain is sometimes difficult. If the formula that defines the function contains divisions, the values of the variable for which a denominator is zero must be excluded from the domain; thus, for a complicated function, the determination of the domain passes through the computation of the zeros of auxiliary functions. Similarly, if square roots occur in the definition of a function from to the domain is included in the set of the values of the variable for which the arguments of the square roots are nonnegative.

For example, defines a function whose domain is because is always positive if x is a real number. On the other hand, defines a function from the reals to the reals whose domain is reduced to the interval [−1, 1]. (In old texts, such a domain was called the domain of definition of the function.)

Functions can be classified by the nature of formulas that define them:

- A quadratic function is a function that may be written where a, b, c are constants.

- More generally, a polynomial function is a function that can be defined by a formula involving only additions, subtractions, multiplications, and exponentiation to nonnegative integer powers. For example, and are polynomial functions of .

- A rational function is the same, with divisions also allowed, such as and

- An algebraic function is the same, with nth roots and roots of polynomials also allowed.

- An elementary function[note 4] is the same, with logarithms and exponential functions allowed.

Inverse and implicit functions

[edit]A function with domain X and codomain Y, is bijective, if for every y in Y, there is one and only one element x in X such that y = f(x). In this case, the inverse function of f is the function that maps to the element such that y = f(x). For example, the natural logarithm is a bijective function from the positive real numbers to the real numbers. It thus has an inverse, called the exponential function, that maps the real numbers onto the positive numbers.

If a function is not bijective, it may occur that one can select subsets and such that the restriction of f to E is a bijection from E to F, and has thus an inverse. The inverse trigonometric functions are defined this way. For example, the cosine function induces, by restriction, a bijection from the interval [0, π] onto the interval [−1, 1], and its inverse function, called arccosine, maps [−1, 1] onto [0, π]. The other inverse trigonometric functions are defined similarly.

More generally, given a binary relation R between two sets X and Y, let E be a subset of X such that, for every there is some such that x R y. If one has a criterion allowing selecting such a y for every this defines a function called an implicit function, because it is implicitly defined by the relation R.

For example, the equation of the unit circle defines a relation on real numbers. If −1 < x < 1 there are two possible values of y, one positive and one negative. For x = ± 1, these two values become both equal to 0. Otherwise, there is no possible value of y. This means that the equation defines two implicit functions with domain [−1, 1] and respective codomains [0, +∞) and (−∞, 0].

In this example, the equation can be solved in y, giving but, in more complicated examples, this is impossible. For example, the relation defines y as an implicit function of x, called the Bring radical, which has as domain and range. The Bring radical cannot be expressed in terms of the four arithmetic operations and nth roots.

The implicit function theorem provides mild differentiability conditions for existence and uniqueness of an implicit function in the neighborhood of a point.

Using differential calculus

[edit]Many functions can be defined as the antiderivative of another function. This is the case of the natural logarithm, which is the antiderivative of 1/x that is 0 for x = 1. Another common example is the error function.

More generally, many functions, including most special functions, can be defined as solutions of differential equations. The simplest example is probably the exponential function, which can be defined as the unique function that is equal to its derivative and takes the value 1 for x = 0.

Power series can be used to define functions on the domain in which they converge. For example, the exponential function is given by . However, as the coefficients of a series are quite arbitrary, a function that is the sum of a convergent series is generally defined otherwise, and the sequence of the coefficients is the result of some computation based on another definition. Then, the power series can be used to enlarge the domain of the function. Typically, if a function for a real variable is the sum of its Taylor series in some interval, this power series allows immediately enlarging the domain to a subset of the complex numbers, the disc of convergence of the series. Then analytic continuation allows enlarging further the domain for including almost the whole complex plane. This process is the method that is generally used for defining the logarithm, the exponential and the trigonometric functions of a complex number.

By recurrence

[edit]Functions whose domain are the nonnegative integers, known as sequences, are sometimes defined by recurrence relations.

The factorial function on the nonnegative integers () is a basic example, as it can be defined by the recurrence relation

and the initial condition

Representing a function

[edit]A graph is commonly used to give an intuitive picture of a function. As an example of how a graph helps to understand a function, it is easy to see from its graph whether a function is increasing or decreasing. Some functions may also be represented by bar charts.

Graphs and plots

[edit]

Given a function its graph is, formally, the set

In the frequent case where X and Y are subsets of the real numbers (or may be identified with such subsets, e.g. intervals), an element may be identified with a point having coordinates x, y in a 2-dimensional coordinate system, e.g. the Cartesian plane. Parts of this may create a plot that represents (parts of) the function. The use of plots is so ubiquitous that they too are called the graph of the function. Graphic representations of functions are also possible in other coordinate systems. For example, the graph of the square function

consisting of all points with coordinates for yields, when depicted in Cartesian coordinates, the well known parabola. If the same quadratic function with the same formal graph, consisting of pairs of numbers, is plotted instead in polar coordinates the plot obtained is Fermat's spiral.

Tables

[edit]A function can be represented as a table of values. If the domain of a function is finite, then the function can be completely specified in this way. For example, the multiplication function defined as can be represented by the familiar multiplication table

y x

|

1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| 2 | 2 | 4 | 6 | 8 | 10 |

| 3 | 3 | 6 | 9 | 12 | 15 |

| 4 | 4 | 8 | 12 | 16 | 20 |

| 5 | 5 | 10 | 15 | 20 | 25 |

On the other hand, if a function's domain is continuous, a table can give the values of the function at specific values of the domain. If an intermediate value is needed, interpolation can be used to estimate the value of the function.[note 5] For example, a portion of a table for the sine function might be given as follows, with values rounded to 6 decimal places:

| x | sin x |

|---|---|

| 1.289 | 0.960557 |

| 1.290 | 0.960835 |

| 1.291 | 0.961112 |

| 1.292 | 0.961387 |

| 1.293 | 0.961662 |

Before the advent of handheld calculators and personal computers, such tables were often compiled and published for functions such as logarithms and trigonometric functions.[note 6]

Bar chart

[edit]A bar chart can represent a function whose domain is a finite set, the natural numbers, or the integers. In this case, an element x of the domain is represented by an interval of the x-axis, and the corresponding value of the function, f(x), is represented by a rectangle whose base is the interval corresponding to x and whose height is f(x) (possibly negative, in which case the bar extends below the x-axis).

General properties

[edit]This section describes general properties of functions, that are independent of specific properties of the domain and the codomain.

Standard functions

[edit]There are a number of standard functions that occur frequently:

- For every set X, there is a unique function, called the empty function, or empty map, from the empty set to X. The graph of an empty function is the empty set.[note 7] The existence of empty functions is needed both for the coherency of the theory and for avoiding exceptions concerning the empty set in many statements. Under the usual set-theoretic definition of a function as an ordered triplet (or equivalent ones), there is exactly one empty function for each set, thus the empty function is not equal to if and only if , although their graphs are both the empty set.

- For every set X and every singleton set {s}, there is a unique function from X to {s}, which maps every element of X to s. This is a surjection (see below) unless X is the empty set.

- Given a function the canonical surjection of f onto its image is the function from X to f(X) that maps x to f(x).

- For every subset A of a set X, the inclusion map of A into X is the injective (see below) function that maps every element of A to itself.

- The identity function on a set X, often denoted by idX, is the inclusion of X into itself.

Function composition

[edit]Given two functions and such that the domain of g is the codomain of f, their composition is the function defined by

That is, the value of is obtained by first applying f to x to obtain y = f(x) and then applying g to the result y to obtain g(y) = g(f(x)). In this notation, the function that is applied first is always written on the right.

The composition is an operation on functions that is defined only if the codomain of the first function is the domain of the second one. Even when both and satisfy these conditions, the composition is not necessarily commutative, that is, the functions and need not be equal, and may deliver different values for the same argument. For example, let f(x) = x2 and g(x) = x + 1, then and agree just for

The function composition is associative in the sense that, if one of and is defined, then the other is also defined, and they are equal, that is, Therefore, it is usual to just write

The identity functions and are respectively a right identity and a left identity for functions from X to Y. That is, if f is a function with domain X, and codomain Y, one has

-

A composite function g(f(x)) can be visualized as the combination of two "machines".

-

A simple example of a function composition

-

Another composition. In this example, (g ∘ f )(c) = #.

Image and preimage

[edit]Let The image under f of an element x of the domain X is f(x).[6] If A is any subset of X, then the image of A under f, denoted f(A), is the subset of the codomain Y consisting of all images of elements of A,[6] that is,

The image of f is the image of the whole domain, that is, f(X).[17] It is also called the range of f,[6][7][8][9] although the term range may also refer to the codomain.[9][17][18]

On the other hand, the inverse image or preimage under f of an element y of the codomain Y is the set of all elements of the domain X whose images under f equal y.[6] In symbols, the preimage of y is denoted by and is given by the equation

Likewise, the preimage of a subset B of the codomain Y is the set of the preimages of the elements of B, that is, it is the subset of the domain X consisting of all elements of X whose images belong to B.[6] It is denoted by and is given by the equation

For example, the preimage of under the square function is the set .

By definition of a function, the image of an element x of the domain is always a single element of the codomain. However, the preimage of an element y of the codomain may be empty or contain any number of elements. For example, if f is the function from the integers to themselves that maps every integer to 0, then .

If is a function, A and B are subsets of X, and C and D are subsets of Y, then one has the following properties:

The preimage by f of an element y of the codomain is sometimes called, in some contexts, the fiber of y under f.

If a function f has an inverse (see below), this inverse is denoted In this case may denote either the image by or the preimage by f of C. This is not a problem, as these sets are equal. The notation and may be ambiguous in the case of sets that contain some subsets as elements, such as In this case, some care may be needed, for example, by using square brackets for images and preimages of subsets and ordinary parentheses for images and preimages of elements.

Injective, surjective and bijective functions

[edit]Let be a function.

The function f is injective (or one-to-one, or is an injection) if f(a) ≠ f(b) for every two different elements a and b of X.[17][19] Equivalently, f is injective if and only if, for every the preimage contains at most one element. An empty function is always injective. If X is not the empty set, then f is injective if and only if there exists a function such that that is, if f has a left inverse.[19] Proof: If f is injective, for defining g, one chooses an element in X (which exists as X is supposed to be nonempty),[note 8] and one defines g by if and if Conversely, if and then and thus

The function f is surjective (or onto, or is a surjection) if its range equals its codomain , that is, if, for each element of the codomain, there exists some element of the domain such that (in other words, the preimage of every is nonempty).[17][20] If, as usual in modern mathematics, the axiom of choice is assumed, then f is surjective if and only if there exists a function such that that is, if f has a right inverse.[20] The axiom of choice is needed, because, if f is surjective, one defines g by where is an arbitrarily chosen element of

The function f is bijective (or is a bijection or a one-to-one correspondence) if it is both injective and surjective.[17][21] That is, f is bijective if, for every the preimage contains exactly one element. The function f is bijective if and only if it admits an inverse function, that is, a function such that and [21] (Contrarily to the case of surjections, this does not require the axiom of choice; the proof is straightforward).

Every function may be factorized as the composition of a surjection followed by an injection, where s is the canonical surjection of X onto f(X) and i is the canonical injection of f(X) into Y. This is the canonical factorization of f.

"One-to-one" and "onto" are terms that were more common in the older English language literature; "injective", "surjective", and "bijective" were originally coined as French words in the second quarter of the 20th century by the Bourbaki group and imported into English.[22] As a word of caution, "a one-to-one function" is one that is injective, while a "one-to-one correspondence" refers to a bijective function. Also, the statement "f maps X onto Y" differs from "f maps X into B", in that the former implies that f is surjective, while the latter makes no assertion about the nature of f. In a complicated reasoning, the one letter difference can easily be missed. Due to the confusing nature of this older terminology, these terms have declined in popularity relative to the Bourbakian terms, which have also the advantage of being more symmetrical.

Restriction and extension

[edit]If is a function and S is a subset of X, then the restriction of to S, denoted , is the function from S to Y defined by

for all x in S. Restrictions can be used to define partial inverse functions: if there is a subset S of the domain of a function such that is injective, then the canonical surjection of onto its image is a bijection, and thus has an inverse function from to S. One application is the definition of inverse trigonometric functions. For example, the cosine function is injective when restricted to the interval [0, π]. The image of this restriction is the interval [−1, 1], and thus the restriction has an inverse function from [−1, 1] to [0, π], which is called arccosine and is denoted arccos.

Function restriction may also be used for "gluing" functions together. Let be the decomposition of X as a union of subsets, and suppose that a function is defined on each such that for each pair of indices, the restrictions of and to are equal. Then this defines a unique function such that for all i. This is the way that functions on manifolds are defined.

An extension of a function f is a function g such that f is a restriction of g. A typical use of this concept is the process of analytic continuation, that allows extending functions whose domain is a small part of the complex plane to functions whose domain is almost the whole complex plane.

Here is another classical example of a function extension that is encountered when studying homographies of the real line. A homography is a function such that ad − bc ≠ 0. Its domain is the set of all real numbers different from and its image is the set of all real numbers different from If one extends the real line to the projectively extended real line by including ∞, one may extend h to a bijection from the extended real line to itself by setting and .

In calculus

[edit]The idea of function, starting in the 17th century, was fundamental to the new infinitesimal calculus. At that time, only real-valued functions of a real variable were considered, and all functions were assumed to be smooth. But the definition was soon extended to functions of several variables and to functions of a complex variable. In the second half of the 19th century, the mathematically rigorous definition of a function was introduced, and functions with arbitrary domains and codomains were defined.

Functions are now used throughout all areas of mathematics. In introductory calculus, when the word function is used without qualification, it means a real-valued function of a single real variable. The more general definition of a function is usually introduced to second or third year college students with STEM majors, and in their senior year they are introduced to calculus in a larger, more rigorous setting in courses such as real analysis and complex analysis.

Real function

[edit]

A real function is a real-valued function of a real variable, that is, a function whose codomain is the field of real numbers and whose domain is a set of real numbers that contains an interval. In this section, these functions are simply called functions.

The functions that are most commonly considered in mathematics and its applications have some regularity, that is they are continuous, differentiable, and even analytic. This regularity insures that these functions can be visualized by their graphs. In this section, all functions are differentiable in some interval.

Functions enjoy pointwise operations, that is, if f and g are functions, their sum, difference and product are functions defined by

The domains of the resulting functions are the intersection of the domains of f and g. The quotient of two functions is defined similarly by

but the domain of the resulting function is obtained by removing the zeros of g from the intersection of the domains of f and g.

The polynomial functions are defined by polynomials, and their domain is the whole set of real numbers. They include constant functions, linear functions and quadratic functions. Rational functions are quotients of two polynomial functions, and their domain is the real numbers with a finite number of them removed to avoid division by zero. The simplest rational function is the function whose graph is a hyperbola, and whose domain is the whole real line except for 0.

The derivative of a real differentiable function is a real function. An antiderivative of a continuous real function is a real function that has the original function as a derivative. For example, the function is continuous, and even differentiable, on the positive real numbers. Thus one antiderivative, which takes the value zero for x = 1, is a differentiable function called the natural logarithm.

A real function f is monotonic in an interval if the sign of does not depend of the choice of x and y in the interval. If the function is differentiable in the interval, it is monotonic if the sign of the derivative is constant in the interval. If a real function f is monotonic in an interval I, it has an inverse function, which is a real function with domain f(I) and image I. This is how inverse trigonometric functions are defined in terms of trigonometric functions, where the trigonometric functions are monotonic. Another example: the natural logarithm is monotonic on the positive real numbers, and its image is the whole real line; therefore it has an inverse function that is a bijection between the real numbers and the positive real numbers. This inverse is the exponential function.

Many other real functions are defined either by the implicit function theorem (the inverse function is a particular instance) or as solutions of differential equations. For example, the sine and the cosine functions are the solutions of the linear differential equation

such that

Vector-valued function

[edit]When the elements of the codomain of a function are vectors, the function is said to be a vector-valued function. These functions are particularly useful in applications, for example modeling physical properties. For example, the function that associates to each point of a fluid its velocity vector is a vector-valued function.

Some vector-valued functions are defined on a subset of or other spaces that share geometric or topological properties of , such as manifolds. These vector-valued functions are given the name vector fields.

Function space

[edit]In mathematical analysis, and more specifically in functional analysis, a function space is a set of scalar-valued or vector-valued functions, which share a specific property and form a topological vector space. For example, the real smooth functions with a compact support (that is, they are zero outside some compact set) form a function space that is at the basis of the theory of distributions.

Function spaces play a fundamental role in advanced mathematical analysis, by allowing the use of their algebraic and topological properties for studying properties of functions. For example, all theorems of existence and uniqueness of solutions of ordinary or partial differential equations result of the study of function spaces.

Multi-valued functions

[edit]

Several methods for specifying functions of real or complex variables start from a local definition of the function at a point or on a neighbourhood of a point, and then extend by continuity the function to a much larger domain. Frequently, for a starting point there are several possible starting values for the function.

For example, in defining the square root as the inverse function of the square function, for any positive real number there are two choices for the value of the square root, one of which is positive and denoted and another which is negative and denoted These choices define two continuous functions, both having the nonnegative real numbers as a domain, and having either the nonnegative or the nonpositive real numbers as images. When looking at the graphs of these functions, one can see that, together, they form a single smooth curve. It is therefore often useful to consider these two square root functions as a single function that has two values for positive x, one value for 0 and no value for negative x.

In the preceding example, one choice, the positive square root, is more natural than the other. This is not the case in general. For example, let consider the implicit function that maps y to a root x of (see the figure on the right). For y = 0 one may choose either for x. By the implicit function theorem, each choice defines a function; for the first one, the (maximal) domain is the interval [−2, 2] and the image is [−1, 1]; for the second one, the domain is [−2, ∞) and the image is [1, ∞); for the last one, the domain is (−∞, 2] and the image is (−∞, −1]. As the three graphs together form a smooth curve, and there is no reason for preferring one choice, these three functions are often considered as a single multi-valued function of y that has three values for −2 < y < 2, and only one value for y ≤ −2 and y ≥ −2.

Usefulness of the concept of multi-valued functions is clearer when considering complex functions, typically analytic functions. The domain to which a complex function may be extended by analytic continuation generally consists of almost the whole complex plane. However, when extending the domain through two different paths, one often gets different values. For example, when extending the domain of the square root function, along a path of complex numbers with positive imaginary parts, one gets i for the square root of −1; while, when extending through complex numbers with negative imaginary parts, one gets −i. There are generally two ways of solving the problem. One may define a function that is not continuous along some curve, called a branch cut. Such a function is called the principal value of the function. The other way is to consider that one has a multi-valued function, which is analytic everywhere except for isolated singularities, but whose value may "jump" if one follows a closed loop around a singularity. This jump is called the monodromy.

In the foundations of mathematics

[edit]The definition of a function that is given in this article requires the concept of set, since the domain and the codomain of a function must be a set. This is not a problem in usual mathematics, as it is generally not difficult to consider only functions whose domain and codomain are sets, which are well defined, even if the domain is not explicitly defined. However, it is sometimes useful to consider more general functions.

For example, the singleton set may be considered as a function Its domain would include all sets, and therefore would not be a set. In usual mathematics, one avoids this kind of problem by specifying a domain, which means that one has many singleton functions. However, when establishing foundations of mathematics, one may have to use functions whose domain, codomain or both are not specified, and some authors, often logicians, give precise definitions for these weakly specified functions.[23]

These generalized functions may be critical in the development of a formalization of the foundations of mathematics. For example, Von Neumann–Bernays–Gödel set theory, is an extension of the set theory in which the collection of all sets is a class. This theory includes the replacement axiom, which may be stated as: If X is a set and F is a function, then F[X] is a set.

In alternative formulations of the foundations of mathematics using type theory rather than set theory, functions are taken as primitive notions rather than defined from other kinds of object. They are the inhabitants of function types, and may be constructed using expressions in the lambda calculus.[24]

In computer science

[edit]In computer programming, a function is, in general, a subroutine which implements the abstract concept of function. That is, it is a program unit that produces an output for each input. Functional programming is the programming paradigm consisting of building programs by using only subroutines that behave like mathematical functions, meaning that they have no side effects and depend only on their arguments: they are referentially transparent. For example, if_then_else is a function that takes three (nullary) functions as arguments, and, depending on the value of the first argument (true or false), returns the value of either the second or the third argument. An important advantage of functional programming is that it makes easier program proofs, as being based on a well founded theory, the lambda calculus (see below). However, side effects are generally necessary for practical programs, ones that perform input/output. There is a class of purely functional languages, such as Haskell, which encapsulate the possibility of side effects in the type of a function. Others, such as the ML family, simply allow side effects.

In many programming languages, every subroutine is called a function, even when there is no output but only side effects, and when the functionality consists simply of modifying some data in the computer memory.

Outside the context of programming languages, "function" has the usual mathematical meaning in computer science. In this area, a property of major interest is the computability of a function. For giving a precise meaning to this concept, and to the related concept of algorithm, several models of computation have been introduced, the old ones being general recursive functions, lambda calculus, and Turing machine. The fundamental theorem of computability theory is that these three models of computation define the same set of computable functions, and that all the other models of computation that have ever been proposed define the same set of computable functions or a smaller one. The Church–Turing thesis is the claim that every philosophically acceptable definition of a computable function defines also the same functions.

General recursive functions are partial functions from integers to integers that can be defined from

- constant functions,

- successor, and

- projection functions

via the operators

Although defined only for functions from integers to integers, they can model any computable function as a consequence of the following properties:

- a computation is the manipulation of finite sequences of symbols (digits of numbers, formulas, etc.),

- every sequence of symbols may be coded as a sequence of bits,

- a bit sequence can be interpreted as the binary representation of an integer.

Lambda calculus is a theory that defines computable functions without using set theory, and is the theoretical background of functional programming. It consists of terms that are either variables, function definitions (𝜆-terms), or applications of functions to terms. Terms are manipulated by interpreting its axioms (the α-equivalence, the β-reduction, and the η-conversion) as rewriting rules, which can be used for computation.

In its original form, lambda calculus does not include the concepts of domain and codomain of a function. Roughly speaking, they have been introduced in the theory under the name of type in typed lambda calculus. Most kinds of typed lambda calculi can define fewer functions than untyped lambda calculus.

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ This definition of "graph" refers to a set of pairs of objects. Graphs, in the sense of diagrams, are most applicable to functions from the real numbers to themselves. All functions can be described by sets of pairs but it may not be practical to construct a diagram for functions between other sets (such as sets of matrices).

- ^ The true domain of such a function is often called the domain of definition of the function.

- ^ n may also be 1, thus subsuming functions as defined above. For n = 0, each constant is a special case of a multivariate function, too.

- ^ Here "elementary" has not exactly its common sense: although most functions that are encountered in elementary courses of mathematics are elementary in this sense, some elementary functions are not elementary for the common sense, for example, those that involve roots of polynomials of high degree.

- ^ provided the function is continuous, see below

- ^ See e.g. commons:Category:Logarithm tables for a collection of historical tables.

- ^ By definition, the graph of the empty function to X is a subset of the Cartesian product ∅ × X, and this product is empty.

- ^ The axiom of choice is not needed here, as the choice is done in a single set.

References

[edit]- ^ Halmos 1970, p. 30; the words map, mapping, transformation, correspondence, and operator are sometimes used synonymously.

- ^ Halmos 1970

- ^ "Mapping". Encyclopedia of Mathematics. EMS Press. 2001 [1994].

- ^ "function | Definition, Types, Examples, & Facts". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 2020-08-17.

- ^ Spivak 2008, p. 39.

- ^ a b c d e f Kudryavtsev, L.D. (2001) [1994]. "Function". Encyclopedia of Mathematics. EMS Press.

- ^ a b Taalman, Laura; Kohn, Peter (2014). Calculus. New York City: W. H. Freeman and Company. p. 3. ISBN 978-1-4292-4186-1. LCCN 2012947365. OCLC 856545590. OL 27544563M.

- ^ a b Trench, William F. (2013) [2003]. Introduction to Real Analysis (2.04th ed.). Pearson Education (originally; self-republished by the author). pp. 30–32. ISBN 0-13-045786-8. LCCN 2002032369. OCLC 953799815. Zbl 1204.00023.

- ^ a b c Thomson, Brian S.; Bruckner, Judith B.; Bruckner, Andrew M. (2008) [2001]. Elementary Real Analysis (PDF) (2nd ed.). Prentice Hall (originally; 2nd ed. self-republished by the authors). pp. A-4 – A-5. ISBN 978-1-4348-4367-8. OCLC 1105855173. OL 31844948M. Zbl 0872.26001.

- ^ Halmos, Paul R. (1974). Naive Set Theory. Springer. pp. 30–33.

- ^ Larson, Ron; Edwards, Bruce H. (2010). Calculus of a Single Variable. Cengage Learning. p. 19. ISBN 978-0-538-73552-0.

- ^ Weisstein, Eric W. "Map". Wolfram MathWorld. Retrieved 2019-06-12.

- ^ a b Lang, Serge (1987). "III §1. Mappings". Linear Algebra (3rd ed.). Springer. p. 43. ISBN 978-0-387-96412-6.

A function is a special type of mapping, namely it is a mapping from a set into the set of numbers, i.e. into, R, or C or into a field K.

- ^ a b Apostol, T. M. (1981). Mathematical Analysis (2nd ed.). Addison-Wesley. p. 35. ISBN 978-0-201-00288-1. OCLC 928947543.

- ^ James, Robert C.; James, Glenn (1992). Mathematics dictionary (5th ed.). Van Nostrand Reinhold. p. 202. ISBN 0-442-00741-8. OCLC 25409557.

- ^ James & James 1992, p. 48

- ^ a b c d e Gowers, Timothy; Barrow-Green, June; Leader, Imre, eds. (2008). The Princeton Companion to Mathematics. Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton University Press. p. 11. doi:10.1515/9781400830398. ISBN 978-0-691-11880-2. JSTOR j.ctt7sd01. LCCN 2008020450. MR 2467561. OCLC 227205932. OL 19327100M. Zbl 1242.00016.

- ^ Quantities and Units - Part 2: Mathematical signs and symbols to be used in the natural sciences and technology, p. 15. ISO 80000-2 (ISO/IEC 2009-12-01)

- ^ a b Ivanova, O. A. (2001) [1994]. "Injection". Encyclopedia of Mathematics. EMS Press.

- ^ a b Ivanova, O.A. (2001) [1994]. "Surjection". Encyclopedia of Mathematics. EMS Press.

- ^ a b Ivanova, O.A. (2001) [1994]. "Bijection". Encyclopedia of Mathematics. EMS Press.

- ^ Hartnett, Kevin (9 November 2020). "Inside the Secret Math Society Known Simply as Nicolas Bourbaki". Quanta Magazine. Retrieved 2024-06-05.

- ^ Gödel 1940, p. 16; Jech 2003, p. 11; Cunningham 2016, p. 57

- ^ Klev, Ansten (2019). "A comparison of type theory with set theory". In Centrone, Stefania; Kant, Deborah; Sarikaya, Deniz (eds.). Reflections on the Foundations of Mathematics: Univalent Foundations, Set Theory and General Thoughts. Synthese Library. Vol. 407. Cham: Springer. pp. 271–292. doi:10.1007/978-3-030-15655-8_12. ISBN 978-3-030-15654-1. MR 4352345.

Sources

[edit]- Bartle, Robert (1976). The Elements of Real Analysis (2nd ed.). Wiley. ISBN 978-0-471-05465-8. OCLC 465115030.

- Bloch, Ethan D. (2011). Proofs and Fundamentals: A First Course in Abstract Mathematics. Springer. ISBN 978-1-4419-7126-5.

- Cunningham, Daniel W. (2016). Set theory: A First Course. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-107-12032-7.

- Gödel, Kurt (1940). The Consistency of the Continuum Hypothesis. Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0-691-07927-1.

{{cite book}}: ISBN / Date incompatibility (help) - Halmos, Paul R. (1970). Naive Set Theory. Springer-Verlag. ISBN 978-0-387-90092-6.

- Jech, Thomas (2003). Set theory (3rd ed.). Springer-Verlag. ISBN 978-3-540-44085-7.

- Spivak, Michael (2008). Calculus (4th ed.). Publish or Perish. ISBN 978-0-914098-91-1.

Further reading

[edit]- Anton, Howard (1980). Calculus with Analytical Geometry. Wiley. ISBN 978-0-471-03248-9.

- Bartle, Robert G. (1976). The Elements of Real Analysis (2nd ed.). Wiley. ISBN 978-0-471-05464-1.

- Dubinsky, Ed; Harel, Guershon (1992). The Concept of Function: Aspects of Epistemology and Pedagogy. Mathematical Association of America. ISBN 978-0-88385-081-7.

- Hammack, Richard (2009). "12. Functions" (PDF). Book of Proof. Virginia Commonwealth University. Retrieved 2012-08-01.

- Husch, Lawrence S. (2001). Visual Calculus. University of Tennessee. Retrieved 2007-09-27.

- Katz, Robert (1964). Axiomatic Analysis. D. C. Heath and Company.

- Kleiner, Israel (1989). "Evolution of the Function Concept: A Brief Survey". The College Mathematics Journal. 20 (4): 282–300. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.113.6352. doi:10.2307/2686848. JSTOR 2686848.

- Lützen, Jesper (2003). "Between rigor and applications: Developments in the concept of function in mathematical analysis". In Porter, Roy (ed.). The Cambridge History of Science: The modern physical and mathematical sciences. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-57199-9. An approachable and diverting historical presentation.

- Malik, M. A. (1980). "Historical and pedagogical aspects of the definition of function". International Journal of Mathematical Education in Science and Technology. 11 (4): 489–492. doi:10.1080/0020739800110404.

- Reichenbach, Hans (1947). Elements of Symbolic Logic. Dover. ISBN 0-486-24004-5.

{{cite book}}: ISBN / Date incompatibility (help) - Ruthing, D. (1984). "Old Intelligencer: Some definitions of the concept of function from Bernoulli, Joh. to Bourbaki, N.". Mathematical Intelligencer. 6 (4): 71–78. doi:10.1007/BF03026743. S2CID 189883712.

- Thomas, George B.; Finney, Ross L. (1995). Calculus and Analytic Geometry (9th ed.). Addison-Wesley. ISBN 978-0-201-53174-9.

External links

[edit]- The Wolfram Functions – website giving formulae and visualizations of many mathematical functions

- NIST Digital Library of Mathematical Functions

Function (mathematics)

View on GrokipediaDefinition and Fundamentals

Formal Definition

In mathematics, the Cartesian product of two sets and consists of all ordered pairs where and .[9] A function is formally defined as a binary relation between sets and , meaning it is a subset of the Cartesian product such that for every element , there exists exactly one element satisfying .[9] This uniqueness condition ensures that each input from the domain corresponds to precisely one output in the codomain , distinguishing functions from more general relations.[9] The set of all such pairs is known as the graph of the function.[9] The concept of a function as an arbitrary mapping between sets traces its evolution to earlier mathematical ideas. Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz introduced the term "function" in 1673 to describe geometric dependencies in curves.[10] Leonhard Euler advanced the notion in 1748 as an analytic expression involving variables and constants, later broadening it in 1755 to quantities that change dependently with others.[10] Peter Gustav Lejeune Dirichlet formalized the modern perspective in 1837 by defining a function as an arbitrary correspondence or succession of values between quantities, building on Joseph Fourier's earlier emphasis on arbitrary associations and separating the concept from continuous or analytic representations.[10] For example, the squaring function defined by forms a subset of including pairs such as , , and , where each real number maps uniquely to its square.[9]Domain, Codomain, and Range

In the context of a function , the domain of , denoted or simply , is the set of all input elements for which is defined.[11] This set specifies the valid arguments that the function accepts, ensuring that the mapping is well-defined for every element in it.[12] For instance, in real analysis, the domain might exclude points where the function is undefined, such as points where the expression involves division by zero or other undefined operations.[13] The codomain of , denoted or , is the target set into which the function maps its inputs; it represents the collection of all possible output values that could theoretically be produced, though not all elements of need to be achieved.[11] Unlike the domain, which is determined by where the function is defined, the codomain is chosen by the definer of the function and may be larger than necessary.[14] This choice allows flexibility in describing the function's intended scope, such as specifying the codomain as the real numbers even if outputs are restricted.[15] The range of , also known as the image and denoted or , is the subset of the codomain consisting precisely of all actual output values for .[16] It captures exactly what the function produces, distinguishing it from the codomain, which may include extraneous elements never attained.[12] For example, consider the function with domain and codomain ; here, the range is , as the function outputs only non-negative reals.[14] This distinction highlights that while the codomain is part of the function's specification, the range emerges from its behavior.[17]Total and Partial Functions

In mathematics, a total function from a set to a set , denoted , is a relation that assigns to every element a unique element , ensuring the function is defined for all inputs in its domain without exception.[18] This totality requirement distinguishes total functions from more general mappings, emphasizing completeness over the entire specified domain.[19] A partial function, in contrast, relaxes this condition by allowing the mapping to be undefined for some elements in , effectively defining the function only on a subset of .[20] Graphically, partial functions are represented by excluding points from the graph where the function is undefined, such as gaps corresponding to division by zero.[21] The standard notation for a partial function is , indicating that the domain may be a proper subset of , or it can be specified explicitly by stating conditions under which is undefined.[22] For instance, the function is partial when considered from to , as it is undefined at .[18] Partial functions find significant application in computability theory, where many computable processes, such as the halting problem, yield partial mappings because no algorithm can determine outcomes for all inputs.[23] In this context, partial recursive functions form the basis of Turing computability, encompassing all total recursive functions as a subclass while accounting for non-halting computations.[24] From a set-theoretic perspective, both total and partial functions are special cases of binary relations: a relation qualifies as a (partial) function if each element of relates to at most one element of , with totality requiring exactly one for every element in .[18] This relational view underscores that partial functions lack only the totality axiom, enabling broader modeling of incomplete or conditional mappings in mathematics.[22]Functions of Multiple Variables

In mathematics, functions of multiple variables generalize the unary function concept by defining mappings from Cartesian products of sets to another set. Specifically, a binary function assigns to each ordered pair with and a unique output , ensuring that the relation is functional—each input pair maps to exactly one element in the codomain.[25][26] The domain of such a function is the Cartesian product , which collects all possible ordered pairs from the input sets. For instance, in the real numbers, the domain might be , representing the plane where inputs are pairs of real coordinates.[27][28] A concrete example is the addition function , where the domain is (all pairs of real numbers) and the codomain is , producing a real output for any input pair without restrictions.[27][28] This extends to higher arity through n-ary functions , where (n times) is the n-fold Cartesian product, consisting of n-tuples with each , and the function assigns a unique element of to each such tuple.[26][29] Importantly, these differ from iterated unary functions obtained via composition, such as where both and are unary and the overall input remains a single variable; in contrast, a binary function like treats and as independent joint inputs from the product space.[29][28]Notation and Specification

Common Notations

In mathematics, the notation for functions has undergone significant evolution, beginning with early analytic expressions and progressing to modern symbolic conventions that emphasize clarity and generality. Leonhard Euler played a pivotal role in this development by introducing the functional notation in 1734 to denote an arbitrary function applied to the variable , marking a shift from geometric descriptions to algebraic symbolism.[30] This innovation, detailed in his work Commentarii Academiae Scientiarum Petropolitanae, facilitated the systematic treatment of functions in calculus and analysis, building on Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz's earlier conceptualization of functions in 1673 without standardized symbols.[30] By the late 18th century, Joseph-Louis Lagrange further popularized in his 1797 Théorie des fonctions analytiques, using it to express functions explicitly as some expression, which remains the conventional way to specify the output of a function for a given input.[31] A fundamental convention for declaring the domain and codomain of a function is the arrow notation , where is the domain and the codomain, indicating that maps elements from to elements in . This set-theoretic style emerged in the early 20th century within topology, with its earliest documented use appearing around 1940 in papers by Witold Hurewicz and Norman Steenrod, who employed it to describe continuous mappings between spaces.[32] The notation gained widespread adoption in algebraic topology and category theory shortly thereafter, providing a concise visual representation of functional mappings without specifying individual values.[32] For families or sequences of functions, indexed notation such as (where is an index, often from a set like the natural numbers) is standard, allowing distinction among related functions, as in , , etc. This practice traces back to Leibniz's 1698 suggestions for subscripted variables like to handle multiple quantities, later extended by Carl Gustav Jacob Jacobi in the 19th century for multivariable functions with indexed components .[31] Such indexing is essential in areas like linear algebra and analysis for denoting bases of function spaces or parameterized families. Dot notation appears rarely in function contexts, primarily in physics and differential geometry to indicate derivatives with respect to time, such as for the velocity vector derived from position , a convention originating with Isaac Newton's fluxion notation in the late 17th century.[33] In more abstract settings, uses a dot as a placeholder for an arbitrary argument, emphasizing the functional form without specifying inputs. Specialized notations include the Iverson bracket , which defines a characteristic function equal to 1 if the proposition is true and 0 otherwise, serving as a compact indicator in logic and combinatorics. Introduced by Kenneth E. Iverson in his 1962 book A Programming Language as part of APL's design, it generalizes Boolean evaluation into mathematical expressions.[34]Explicit Listing and Formulas

One method to specify a function explicitly is by listing the mappings for each element in a finite domain, often called the roster method or enumeration. For instance, consider a function defined by and ; this fully determines the function without ambiguity.[35] Such listings are practical only for small finite sets, as the number of possible functions grows exponentially with domain size—for a domain of elements and codomain of elements, there are functions.[36] For functions on infinite or continuous domains, explicit definitions typically use closed-form expressions, which express the output in terms of a finite combination of elementary operations, constants, and standard functions like polynomials, exponentials, or logarithms. A simple example is the linear function , where the output is computed directly via multiplication and addition for any input in the domain, such as the real numbers.[37] More complex closed-form functions include polynomials like or exponentials such as , both of which allow direct evaluation without iteration or approximation for most inputs.[38] Piecewise definitions provide another explicit form by partitioning the domain into intervals and assigning a closed-form expression to each, enabling the representation of functions that behave differently across regions. For example, the absolute value function is defined as This construction ensures the function is fully specified, with evaluation depending on which interval the input falls into.[39] Piecewise functions are common in applications like step functions or rectifiers in signal processing.[40] A classic example of a closed-form function on an infinite domain is the sine function, defined for all real numbers by , which can be evaluated using its Taylor series expansion around zero but is considered closed-form in terms of the elementary trigonometric operations. This allows precise computation for any , such as , and extends to complex arguments via Euler's formula . However, not all functions admit simple closed-form expressions; many, particularly non-analytic smooth functions like the bump function for and otherwise, cannot be expressed using finite elementary operations and require piecewise or series definitions instead.[41] Such limitations highlight that while explicit formulas suffice for many practical cases, arbitrary functions may demand alternative specifications.[37]Recurrence and Implicit Definitions

In mathematics, functions on the natural numbers or sequences can be defined recursively through a recurrence relation, which expresses each term as a function of preceding terms, supplemented by initial conditions to uniquely determine the sequence. This approach is particularly useful for defining functions that exhibit self-similar or accumulative patterns, such as those in combinatorics and number theory.[42] A simple example is the factorial function, defined recursively by the base case and the recursive step for nonnegative integers , yielding . This builds the value incrementally, with each step multiplying the previous result by the next integer. Another well-known instance is the Fibonacci sequence, specified by the initial conditions , , and the relation for , producing the terms 0, 1, 1, 2, 3, 5, 8, and so on.[42][43] Recursive definitions frequently rely on iteration, where the -fold iteration of a function denotes the result of composing with itself times, i.e., with applications. This process generates sequences of values that can approximate solutions or reveal dynamical behavior, as seen in recursive computations./Text/2%3A_Sequences/2.4%3A_Solving_Recurrence_Relations) Functions can also be defined implicitly via an equation relating the input and output variables without isolating the output explicitly. For example, the equation implicitly defines as a multi-valued function of on the unit circle, where solving yields for , but the implicit form captures the full relation compactly. Implicit definitions are advantageous when explicit expressions are algebraically intractable or when the relation itself is the primary interest, such as in geometry or systems of equations.[44] Despite their utility, recursive and implicit definitions can encounter convergence issues. In recursive sequences, if the underlying relation amplifies terms excessively—such as in a linear recurrence with a characteristic root of magnitude greater than 1—the sequence may diverge, preventing a well-defined limit or extension to continuous domains. Similarly, iterative processes may fail to converge to a fixed point unless the function satisfies conditions like contractivity, requiring careful analysis to ensure the definition yields a valid function./02%3A_Root_Finding/2.04%3A_Order_of_Convergence)Representations

Graphical Representations

Graphical representations provide a visual means to depict the behavior of functions over their domains, facilitating intuitive understanding of relationships between inputs and outputs. For functions of a single variable, the Cartesian graph is the primary method, where points are plotted in a two-dimensional plane with the horizontal axis representing the domain and the vertical axis the codomain or range. This approach, rooted in René Descartes' coordinate system, allows for the visualization of curves that illustrate how the function maps inputs to outputs, such as rising, falling, or oscillating patterns.[45] A classic example is the quadratic function , whose graph forms a parabola symmetric about the y-axis, opening upwards with its vertex at the origin. Key features like x-intercepts (where the graph crosses the horizontal axis, indicating roots) and y-intercepts (where it crosses the vertical axis) are readily identified on such plots; for , the y-intercept is at (0,0), and there are no x-intercepts. Asymptotes, which are lines that the graph approaches but never touches, are also crucial for rational or exponential functions; vertical asymptotes occur where the function is undefined (e.g., denominator zero), while horizontal ones describe long-term behavior as approaches infinity. These elements help reveal discontinuities, monotonicity trends, and overall shape without algebraic computation.[46] For functions of multiple variables, such as , graphical representations extend to three dimensions or projections thereof. Three-dimensional surface plots display the function as a surface in space, where the height corresponds to the output value, enabling visualization of peaks, valleys, and saddles that indicate maxima, minima, or inflection points. Contour plots, alternatively, project level sets onto the xy-plane, with curves connecting points of equal function value (e.g., ), akin to topographic maps; denser contours signify steeper gradients. These methods are essential for understanding multivariable behavior, as full 3D immersion is challenging in static images.[47][27] Hand-sketching remains a foundational tool for quick approximations and pedagogical purposes, relying on key points, symmetry, and transformations to outline basic shapes. However, for precision, especially with complex or data-driven functions, computer-generated plots are preferred; software like MATLAB uses commands such asfplot for symbolic expressions or surf for 3D surfaces, allowing interactive scaling, rotation, and annotation to explore domains comprehensively. Other tools, including GeoGebra for dynamic visualizations, complement this by supporting sliders for parameter variation.[48][49]

Despite their utility, graphical representations have limitations, primarily suited to continuous functions or discrete sampled points, as infinite or highly oscillatory behaviors may require dense sampling that obscures details or demands computational resources. High-dimensional functions beyond three variables necessitate dimensionality reduction techniques, and static plots can mislead if scales are distorted or features like asymptotes are not clearly marked. Thus, graphs serve best as complementary tools alongside analytical methods for verification.[50][51]

Tabular and Symbolic Representations

Tabular representations provide a structured way to specify functions with finite domains by listing input-output pairs in a matrix format, where rows typically correspond to inputs and columns to outputs or vice versa, depending on the function's arity.[52] This approach is particularly useful for unary functions, where a single column for inputs pairs directly with a column for outputs, allowing complete enumeration without ambiguity.[53] For example, truth tables represent Boolean functions, which map binary inputs to binary outputs, exhaustively listing all possible combinations to define the function's behavior.[54] A classic truth table for the Boolean AND function, denoted , is shown below, where inputs and are 0 (false) or 1 (true):| 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 0 | 1 | 0 |

| 1 | 0 | 0 |

| 1 | 1 | 1 |

| × | 1 | 2 | 3 |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 1 | 2 | 3 |

| 2 | 2 | 4 | 6 |

| 3 | 3 | 6 | 9 |

Core Properties

Composition and Iteration

In mathematics, the composition of two functions and is a new function defined by for all such that .[61] The domain of consists precisely of those elements in the domain of whose image under lies within the domain of .[62] Function composition is associative: for functions , , and , it holds that , where both compositions are defined on the appropriate domain.[63] This property follows from the equality of the resulting mappings on their common domain, as for all suitable .[64] Iteration refers to the repeated composition of a function with itself; for a function , the -fold iterate is defined recursively by and for positive integers , with denoting the identity function on .[65] For instance, if and , then , illustrating how composition builds more complex functions from simpler ones.[66] The identity function is defined by for all ; it serves as the neutral element for composition, satisfying whenever the domains and codomains align appropriately.[67] This identity property underscores the algebraic structure of the set of functions under composition.[68]Injectivity, Surjectivity, and Bijectivity

A function is injective, also known as one-to-one, if distinct elements in the domain map to distinct elements in the codomain, formally stated as implies for all .[69] For real-valued functions, injectivity can be tested graphically using the horizontal line test: if no horizontal line intersects the graph more than once, the function is injective.[70] A function is surjective, also known as onto, if every element in the codomain is mapped to by at least one element in the domain, meaning the range of equals the codomain , or equivalently, for every , there exists such that .[71] A function is bijective if it is both injective and surjective, establishing a one-to-one correspondence between and .[72] Bijectivity implies the existence of an inverse function such that and .[73] For example, the function from to is injective, as implies (since the exponential function is strictly increasing), but not surjective, since its range is , excluding non-positive reals like 0 or -1.[74] In contrast, from to is bijective, as it maps every real number uniquely to itself.[75] For finite sets and , an injective function implies , by the pigeonhole principle, as each element in maps to a unique element in without exceeding its size.[76] Bijectivity requires , establishing equal cardinality.[76]Image, Preimage, and Restrictions