Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

History of scientific method

View on WikipediaThe history of scientific method considers changes in the methodology of scientific inquiry, as distinct from the history of science itself. The development of rules for scientific reasoning has not been straightforward; scientific method has been the subject of intense and recurring debate throughout the history of science, and eminent natural philosophers and scientists have argued for the primacy of one or another approach to establishing scientific knowledge.

Rationalist explanations of nature, including atomism, appeared both in ancient Greece in the thought of Leucippus and Democritus, and in ancient India, in the Nyaya, Vaisheshika and Buddhist schools, while Charvaka materialism rejected inference as a source of knowledge in favour of an empiricism that was always subject to doubt. Aristotle pioneered scientific method in ancient Greece alongside his empirical biology and his work on logic, rejecting a purely deductive framework in favour of generalisations made from observations of nature.

Some of the most important debates in the history of scientific method center on: rationalism, especially as advocated by René Descartes; inductivism, which rose to particular prominence with Isaac Newton and his followers; and hypothetico-deductivism, which came to the fore in the early 19th century. In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, a debate over realism vs. antirealism was central to discussions of scientific method as powerful scientific theories extended beyond the realm of the observable, while in the mid-20th century some prominent philosophers argued against any universal rules of science at all.[1]

Early methodology

[edit]Ancient Egypt and Babylonia

[edit]

There are few explicit discussions of scientific methodologies in surviving records from early cultures. The most that can be inferred about the approaches to undertaking science in this period stems from descriptions of early investigations into nature, in the surviving records. An Egyptian medical textbook, the Edwin Smith papyrus, (c. 1600 BCE), applies the following components: examination, diagnosis, treatment and prognosis, to the treatment of disease,[2] which display strong parallels to the basic empirical method of science and according to G. E. R. Lloyd[3] played a significant role in the development of this methodology. The Ebers papyrus (c. 1550 BCE) also contains evidence of traditional empiricism.

By the middle of the 1st millennium BCE in Mesopotamia, Babylonian astronomy had evolved into the earliest example of a scientific astronomy, as it was "the first and highly successful attempt at giving a refined mathematical description of astronomical phenomena." According to the historian Asger Aaboe, "all subsequent varieties of scientific astronomy, in the Hellenistic world, in India, in the Islamic world, and in the West – if not indeed all subsequent endeavour in the exact sciences – depend upon Babylonian astronomy in decisive and fundamental ways."[4]

The early Babylonians and Egyptians developed much technical knowledge, crafts, and mathematics[5] used in practical tasks of divination, as well as a knowledge of medicine,[6] and made lists of various kinds. While the Babylonians in particular had engaged in the earliest forms of an empirical mathematical science, with their early attempts at mathematically describing natural phenomena, they generally lacked underlying rational theories of nature.[4][7][8]

Classical antiquity

[edit]Greek-speaking ancient philosophers engaged in the earliest known forms of what is today recognized as a rational theoretical science,[7][9] with the move towards a more rational understanding of nature which began at least since the Archaic Period (650 – 480 BCE) with the Presocratic school. Thales was the first known philosopher to use natural explanations, proclaiming that every event had a natural cause, even though he is known for saying "all things are full of gods" and sacrificed an ox when he discovered his theorem.[10] Leucippus, went on to develop the theory of atomism – the idea that everything is composed entirely of various imperishable, indivisible elements called atoms. This was elaborated in great detail by Democritus.[a]

Similar atomist ideas emerged independently among ancient Indian philosophers of the Nyaya, Vaisesika and Buddhist schools.[11] In particular, like the Nyaya, Vaisesika, and Buddhist schools, the Cārvāka epistemology was materialist, and skeptical enough to admit perception as the basis for unconditionally true knowledge, while cautioning that if one could only infer a truth, then one must also harbor a doubt about that truth; an inferred truth could not be unconditional.[12]

Towards the middle of the 5th century BCE, some of the components of a scientific tradition were already heavily established, even before Plato, who was an important contributor to this emerging tradition, thanks to the development of deductive reasoning, as propounded by his student, Aristotle. In Protagoras (318d–f), Plato mentioned the teaching of arithmetic, astronomy and geometry in schools. The philosophical ideas of this time were mostly freed from the constraints of everyday phenomena and common sense. This denial of reality as we experience it reached an extreme in Parmenides who argued that the world is one and that change and subdivision do not exist.[b]

As early as the 4th century BCE, armillary spheres had been invented in China,[c] and in the 3rd century BCE in Greece for use in astronomy; their use was promulgated thereafter, for example by § Ibn al-Haytham, and by § Tycho Brahe.

In the 3rd and 4th centuries BCE, the Greek physicians Herophilos (335–280 BCE) and Erasistratus of Chios employed experiments to further their medical research; Erasistratus at one time repeatedly weighed a caged bird, and noted its weight loss between feeding times.[15]

Aristotle

[edit]

Aristotle's inductive-deductive method used inductions from observations to infer general principles, deductions from those principles to check against further observations, and more cycles of induction and deduction to continue the advance of knowledge.[16]

The Organon (Greek: Ὄργανον, meaning "instrument, tool, organ") is the standard collection of Aristotle's six works on logic. The name Organon was given by Aristotle's followers, the Peripatetics. The order of the works is not chronological (the chronology is now difficult to determine) but was deliberately chosen by Theophrastus to constitute a well-structured system.[citation needed] Indeed, parts of them seem to be a scheme of a lecture on logic. The arrangement of the works was made by Andronicus of Rhodes around 40 BCE.[17]

The Organon comprises the following six works:

- The Categories (Greek: Κατηγορίαι, Latin: Categoriae) introduces Aristotle's 10-fold classification of that which exists: substance, quantity, quality, relation, place, time, situation, condition, action, and passion.

- On Interpretation (Greek: Περὶ Ἑρμηνείας, Latin: De Interpretatione) introduces Aristotle's conception of proposition and judgment, and the various relations between affirmative, negative, universal, and particular propositions. Aristotle discusses the square of opposition or square of Apuleius in Chapter 7 and its appendix Chapter 8. Chapter 9 deals with the problem of future contingents.

- The Prior Analytics (Greek: Ἀναλυτικὰ Πρότερα, Latin: Analytica Priora) introduces Aristotle's syllogistic method (see term logic), argues for its correctness, and discusses inductive inference.

- The Posterior Analytics (Greek: Ἀναλυτικὰ Ὕστερα, Latin: Analytica Posteriora) deals with demonstration, definition, and scientific knowledge.

- The Topics (Greek: Τοπικά, Latin: Topica) treats of issues in constructing valid arguments, and of inference that is probable, rather than certain. It is in this treatise that Aristotle mentions the predicables, later discussed by Porphyry and by the scholastic logicians.

- The Sophistical Refutations (Greek: Περὶ Σοφιστικῶν Ἐλέγχων, Latin: De Sophisticis Elenchis) gives a treatment of logical fallacies, and provides a key link to Aristotle's work on rhetoric.

Aristotle's Metaphysics has some points of overlap with the works making up the Organon but is not traditionally considered part of it; additionally there are works on logic attributed, with varying degrees of plausibility, to Aristotle that were not known to the Peripatetics.

Aristotle has been called the founder of modern science by De Lacy O'Leary.[18] His demonstration method is found in Posterior Analytics. He provided another of the ingredients of scientific tradition: empiricism. For Aristotle, universal truths can be known from particular things via induction. To some extent then, Aristotle reconciles abstract thought with observation, although it would be a mistake to imply that Aristotelian science is empirical in form. Indeed, Aristotle did not accept that knowledge acquired by induction could rightly be counted as scientific knowledge. Nevertheless, induction was for him a necessary preliminary to the main business of scientific enquiry, providing the primary premises required for scientific demonstrations.

Aristotle largely ignored inductive reasoning in his treatment of scientific enquiry. To make it clear why this is so, consider this statement in the Posterior Analytics:

We suppose ourselves to possess unqualified scientific knowledge of a thing, as opposed to knowing it in the accidental way in which the sophist knows, when we think that we know the cause on which the fact depends, as the cause of that fact and of no other, and, further, that the fact could not be other than it is.

It was therefore the work of the philosopher to demonstrate universal truths and to discover their causes.[19] While induction was sufficient for discovering universals by generalization, it did not succeed in identifying causes. For this task Aristotle used the tool of deductive reasoning in the form of syllogisms. Using the syllogism, scientists could infer new universal truths from those already established.

Aristotle developed a complete normative approach to scientific inquiry involving the syllogism, which he discusses at length in his Posterior Analytics. A difficulty with this scheme lay in showing that derived truths have solid primary premises. Aristotle would not allow that demonstrations could be circular (supporting the conclusion by the premises, and the premises by the conclusion). Nor would he allow an infinite number of middle terms between the primary premises and the conclusion. This leads to the question of how the primary premises are found or developed, and as mentioned above, Aristotle allowed that induction would be required for this task.

Towards the end of the Posterior Analytics, Aristotle discusses knowledge imparted by induction.

Thus it is clear that we must get to know the primary premises by induction; for the method by which even sense-perception implants the universal is inductive. [...] it follows that there will be no scientific knowledge of the primary premises, and since except intuition nothing can be truer than scientific knowledge, it will be intuition that apprehends the primary premises. [...] If, therefore, it is the only other kind of true thinking except scientific knowing, intuition will be the originative source of scientific knowledge.

The account leaves room for doubt regarding the nature and extent of Aristotle's empiricism. In particular, it seems that Aristotle considers sense-perception only as a vehicle for knowledge through intuition. He restricted his investigations in natural history to their natural settings,[20] such as at the Pyrrha lagoon,[21] now called Kalloni, at Lesbos. Aristotle and Theophrastus together formulated the new science of biology,[22] inductively, case by case, for two years before Aristotle was called to tutor Alexander. Aristotle performed no modern-style experiments in the form in which they appear in today's physics and chemistry laboratories.[23] Induction is not afforded the status of scientific reasoning, and so it is left to intuition to provide a solid foundation for Aristotle's science. With that said, Aristotle brings us somewhat closer an empirical science than his predecessors.

Epicurus

[edit]In his work Kαvώv ('canon', a straight edge or ruler, thus any type of measure or standard, referred to as 'canonic'), Epicurus laid out his first rule for inquiry in physics: 'that the first concepts be seen,[24]: p.20 and that they not require demonstration '.[24]: pp.35–47

His second rule for inquiry was that prior to an investigation, we are to have self-evident concepts,[24]: pp.61–80 so that we might infer [ἔχωμεν οἷς σημειωσόμεθα] both what is expected [τò προσμένον], and also what is non-apparent [τò ἄδηλον].[24]: pp.83–103

Epicurus applies his method of inference (the use of observations as signs, Asmis' summary, p. 333: the method of using the phenomena as signs (σημεῖα) of what is unobserved)[24]: pp.175–196 immediately to the atomic theory of Democritus. In Aristotle's Prior Analytics, Aristotle himself employs the use of signs.[24]: pp.212–224 [25] But Epicurus presented his 'canonic' as rival to Aristotle's logic.[24]: pp.19–34 See: Lucretius (c. 99 BCE – c. 55 BCE) De rerum natura (On the nature of things) a didactic poem explaining Epicurus' philosophy and physics.

Emergence of inductive experimental method

[edit]During the Middle Ages issues of what is now termed science began to be addressed. There was greater emphasis on combining theory with practice in the Islamic world than there had been in Classical times, and it was common for those studying the sciences to be artisans as well, something that had been "considered an aberration in the ancient world." Islamic experts in the sciences were often expert instrument makers who enhanced their powers of observation and calculation with them.[26] Starting in the early ninth century, early Muslim scientists such as al-Kindi (801–873) and the authors writing under the name of Jābir ibn Hayyān (writings dated to c. 850–950) began to put a greater emphasis on the use of experiment as a source of knowledge.[27][28] Several scientific methods thus emerged from the medieval Muslim world by the early 11th century, all of which emphasized experimentation as well as quantification to varying degrees.

Ibn al-Haytham

[edit]

The Arab physicist Ibn al-Haytham (Alhazen) used experimentation to obtain the results in his Book of Optics (1021). He combined observations, experiments and rational arguments to support his intromission theory of vision, in which rays of light are emitted from objects rather than from the eyes. He used similar arguments to show that the ancient emission theory of vision supported by Ptolemy and Euclid (in which the eyes emit the rays of light used for seeing), and the ancient intromission theory supported by Aristotle (where objects emit physical particles to the eyes), were both wrong.[30]

Experimental evidence supported most of the propositions in his Book of Optics and grounded his theories of vision, light and colour, as well as his research in catoptrics and dioptrics. His legacy was elaborated through the 'reforming' of his Optics by Kamal al-Din al-Farisi (d. c. 1320) in the latter's Kitab Tanqih al-Manazir (The Revision of [Ibn al-Haytham's] Optics).[31][32]

Alhazen viewed his scientific studies as a search for truth: "Truth is sought for its own sake. And those who are engaged upon the quest for anything for its own sake are not interested in other things. Finding the truth is difficult, and the road to it is rough. ...[33]

Alhazen's work included the conjecture that "Light travels through transparent bodies in straight lines only", which he was able to corroborate only after years of effort. He stated, "[This] is clearly observed in the lights which enter into dark rooms through holes. ... the entering light will be clearly observable in the dust which fills the air."[29] He also demonstrated the conjecture by placing a straight stick or a taut thread next to the light beam.[34]

Ibn al-Haytham also employed scientific skepticism and emphasized the role of empiricism. He also explained the role of induction in syllogism, and criticized Aristotle for his lack of contribution to the method of induction, which Ibn al-Haytham regarded as superior to syllogism, and he considered induction to be the basic requirement for true scientific research.[35]

Something like Occam's razor is also present in the Book of Optics. For example, after demonstrating that light is generated by luminous objects and emitted or reflected into the eyes, he states that therefore "the extramission of [visual] rays is superfluous and useless."[36] He may also have been the first scientist to adopt a form of positivism in his approach. He wrote that "we do not go beyond experience, and we cannot be content to use pure concepts in investigating natural phenomena", and that the understanding of these cannot be acquired without mathematics. After assuming that light is a material substance, he does not further discuss its nature but confines his investigations to the diffusion and propagation of light. The only properties of light he takes into account are those treatable by geometry and verifiable by experiment.[37]

Al-Biruni

[edit]The Persian scientist Abū Rayhān al-Bīrūnī introduced early scientific methods for several different fields of inquiry during the 1020s and 1030s. For example, in his treatise on mineralogy, Kitab al-Jawahir (Book of Precious Stones), al-Biruni is "the most exact of experimental scientists", while in the introduction to his study of India, he declares that "to execute our project, it has not been possible to follow the geometric method" and thus became one of the pioneers of comparative sociology in insisting on field experience and information.[38] He also developed an early experimental method for mechanics.[39]

Al-Biruni's methods resembled the modern scientific method, particularly in his emphasis on repeated experimentation. Biruni was concerned with how to conceptualize and prevent both systematic errors and observational biases, such as "errors caused by the use of small instruments and errors made by human observers." He argued that if instruments produce errors because of their imperfections or idiosyncratic qualities, then multiple observations must be taken, analyzed qualitatively, and on this basis, arrive at a "common-sense single value for the constant sought", whether an arithmetic mean or a "reliable estimate."[40] In his scientific method, "universals came out of practical, experimental work" and "theories are formulated after discoveries", as with inductivism.[38]

Ibn Sina (Avicenna)

[edit]In the On Demonstration section of The Book of Healing (1027), the Persian philosopher and scientist Avicenna (Ibn Sina) discussed philosophy of science and described an early scientific method of inquiry. He discussed Aristotle's Posterior Analytics and significantly diverged from it on several points. Avicenna discussed the issue of a proper procedure for scientific inquiry and the question of "How does one acquire the first principles of a science?" He asked how a scientist might find "the initial axioms or hypotheses of a deductive science without inferring them from some more basic premises?" He explained that the ideal situation is when one grasps that a "relation holds between the terms, which would allow for absolute, universal certainty." Avicenna added two further methods for finding a first principle: the ancient Aristotelian method of induction (istiqra), and the more recent method of examination and experimentation (tajriba). Avicenna criticized Aristotelian induction, arguing that "it does not lead to the absolute, universal, and certain premises that it purports to provide." In its place, he advocated "a method of experimentation as a means for scientific inquiry."[41]

Earlier, in The Canon of Medicine (1025), Avicenna was also the first to describe what is essentially methods of agreement, difference and concomitant variation which are critical to inductive logic and the scientific method.[42][43][44] However, unlike his contemporary al-Biruni's scientific method, in which "universals came out of practical, experimental work" and "theories are formulated after discoveries", Avicenna developed a scientific procedure in which "general and universal questions came first and led to experimental work."[38] Due to the differences between their methods, al-Biruni referred to himself as a mathematical scientist and to Avicenna as a philosopher, during a debate between the two scholars.[45]

Robert Grosseteste

[edit]During the European Renaissance of the 12th century, ideas on scientific methodology, including Aristotle's empiricism and the experimental approaches of Alhazen and Avicenna, were introduced to medieval Europe via Latin translations of Arabic and Greek texts and commentaries.[46] Robert Grosseteste's commentary on the Posterior Analytics places Grosseteste among the first scholastic thinkers in Europe to understand Aristotle's vision of the dual nature of scientific reasoning. Concluding from particular observations into a universal law, and then back again, from universal laws to prediction of particulars. Grosseteste called this "resolution and composition". Further, Grosseteste said that both paths should be verified through experimentation to verify the principles.[47]

Roger Bacon

[edit]While Roger Bacon was not a scientific man and did not undertake experiments himself, he was an excellent writer whose works encouraged those concepts.[48]: 48–49 About 1256 he joined the Franciscan Order and became subject to the Franciscan statute forbidding Friars from publishing books or pamphlets without specific approval. After the accession of Pope Clement IV in 1265, the Pope granted Bacon a special commission to write to him on scientific matters. In eighteen months he completed three large treatises, the Opus Majus, Opus Minus, and Opus Tertium which he sent to the Pope.[49] William Whewell has called Opus Majus at once the Encyclopaedia and Organon of the 13th century.[50]

- Part I (pp. 1–22) treats of the four causes of error: authority, custom, the opinion of the unskilled many, and the concealment of real ignorance by a pretense of knowledge.

- Part VI (pp. 445–477) treats of experimental science, domina omnium scientiarum. There are two methods of knowledge: the one by argument, the other by experience. Mere argument is never sufficient; it may decide a question, but gives no satisfaction or certainty to the mind, which can only be convinced by immediate inspection or intuition, which is what experience gives.

- Experimental science, which in the Opus Tertium (p. 46) is distinguished from the speculative sciences and the operative arts, is said to have three great prerogatives over all sciences:

- It verifies their conclusions by direct experiment;

- It discovers truths which they could never reach;

- It investigates the secrets of nature, and opens to us a knowledge of past and future.

- Roger Bacon illustrated his method by an investigation into the nature and cause of the rainbow, as a specimen of inductive research.[51]

Renaissance humanism and medicine

[edit]Aristotle's ideas became a framework for critical debate beginning with absorption of the Aristotelian texts into the university curriculum in the first half of the 13th century.[52] Contributing to this was the success of medieval theologians in reconciling Aristotelian philosophy with Christian theology. Within the sciences, medieval philosophers were not afraid of disagreeing with Aristotle on many specific issues, although their disagreements were stated within the language of Aristotelian philosophy. All medieval natural philosophers were Aristotelians, but "Aristotelianism" had become a somewhat broad and flexible concept. With the end of Middle Ages, the Renaissance rejection of medieval traditions coupled with an extreme reverence for classical sources led to a recovery of other ancient philosophical traditions, especially the teachings of Plato.[53] By the 17th century, those who clung dogmatically to Aristotle's teachings were faced with several competing approaches to nature.[54]

The discovery of the Americas at the close of the 15th century showed the scholars of Europe that new discoveries could be found outside of the authoritative works of Aristotle, Pliny, Galen, and other ancient writers.

Galen of Pergamon (129 – c. 200 AD) had studied with four schools in antiquity — Platonists, Aristotelians, Stoics, and Epicureans, and at Alexandria, the center of medicine at the time. In his Methodus Medendi, Galen had synthesized the empirical and dogmatic schools of medicine into his own method, which was preserved by Arab scholars. After the translations from Arabic were critically scrutinized, a backlash occurred and demand arose in Europe for translations of Galen's medical text from the original Greek. Galen's method became very popular in Europe. Thomas Linacre, the teacher of Erasmus, thereupon translated Methodus Medendi from Greek into Latin for a larger audience in 1519.[55] Limbrick 1988 notes that 630 editions, translations, and commentaries on Galen were produced in Europe in the 16th century, eventually eclipsing Arabic medicine there, and peaking in 1560, at the time of the Scientific Revolution.[56]

By the late 15th century, the physician-scholar Niccolò Leoniceno was finding errors in Pliny's Natural History. As a physician, Leoniceno was concerned about these botanical errors propagating to the materia medica on which medicines were based.[57] To counter this, a botanical garden was established at Orto botanico di Padova, University of Padua (in use for teaching by 1546), in order that medical students might have empirical access to the plants of a pharmacopia. Other Renaissance teaching gardens were established, notably by the physician Leonhart Fuchs, one of the founders of botany.[58]

The first printed work devoted to the concept of method is Jodocus Willichius, De methodo omnium artium et disciplinarum informanda opusculum (1550). An Informative Essay on the Method of All Arts and Disciplines (1550) [59]

Skepticism as a basis for understanding

[edit]In 1562 Outlines of Pyrrhonism by the ancient Pyrrhonist philosopher Sextus Empiricus (c. 160–210 AD) was published in a Latin translation (from Greek), quickly placing the arguments of classical skepticism in the European mainstream. These arguments establish seemingly insurmountable challenges for the possibility of certain knowledge.

The skeptic philosopher and physician Francisco Sanches, was led by his medical training at Rome, 1571–73, to search for a true method of knowing (modus sciendi), as nothing clear can be known by the methods of Aristotle and his followers[60] — for example, 1) syllogism fails upon circular reasoning; 2) Aristotle's modal logic was not stated clearly enough for use in medieval times, and remains a research problem to this day.[61] Following the physician Galen's method of medicine, Sanches lists the methods of judgement and experience, which are faulty in the wrong hands,[62] and we are left with the bleak statement That Nothing is Known (1581, in Latin Quod Nihil Scitur). This challenge was taken up by René Descartes in the next generation (1637), but at the least, Sanches warns us that we ought to refrain from the methods, summaries, and commentaries on Aristotle, if we seek scientific knowledge. In this, he is echoed by Francis Bacon who was influenced by another prominent exponent of skepticism, Montaigne; Sanches cites the humanist Juan Luis Vives who sought a better educational system, as well as a statement of human rights as a pathway for improvement of the lot of the poor.

"Sanches develops his scepticism by means of an intellectual critique of Aristotelianism, rather than by an appeal to the history of human stupidity and the variety and contrariety of previous theories." —Popkin 1979, p. 37, as cited by Sanches, Limbrick & Thomson 1988, pp. 24–25

"To work, then; and if you know something, then teach me; I shall be extremely grateful to you. In the meantime, as I prepare to examine Things, I shall raise the question anything is known, and if so, how, in the introductory passages of another book,[63] a book in which I will expound, as far as human frailty allows,[64] the method of knowing. Farewell.

WHAT IS TAUGHT HAS NO MORE STRENGTH THAN IT DERIVES FROM HIM WHO IS TAUGHT.

WHAT?" —Francisco Sanches (1581) Quod Nihil Scitur p. 100[65]

Descartes' famous "Cogito" argument is an attempt to overcome skepticism and reestablish a foundation for certainty but other thinkers responded by revising what the search for knowledge, particularly physical knowledge, might be.

Tycho Brahe

[edit]

- See History of astronomy § Renaissance and Early Modern Europe, Kepler's laws of planetary motion, and History of optics § Renaissance and Early Modern

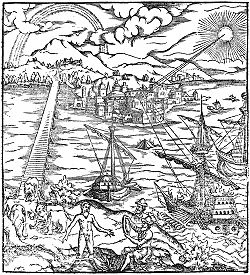

The first modern science, in which practitioners were prepared to revise or reject long-held beliefs in the light of new evidence, was astronomy, and Tycho Brahe was the first modern astronomer. See Sextant, right. Note the explicit reduction of geometrical diagrams to practice (real objects with actual lengths and angles).

In 1572, Tycho noticed a completely new star that was brighter than any star or planet. Astonished by the existence of a star that ought not to have been there and gaining the patronage of King Frederick II of Denmark, Tycho built the Uraniborg observatory at enormous cost. Over a period of fifteen years (1576–1591), Tycho and upwards of thirty assistants charted the positions of stars, planets, and other celestial bodies at Uraniborg with unprecedented accuracy. In 1600, Tycho hired Johannes Kepler to assist him in analyzing and publishing his observations. Kepler later used Tycho's observations of the motion of Mars to deduce the laws of planetary motion, which were later explained in terms of Newton's law of universal gravitation.[66][67]

Besides Tycho's specific role in advancing astronomical knowledge, Tycho's single-minded pursuit of ever-more-accurate measurement was enormously influential in creating a modern scientific culture in which theory and evidence were understood to be inseparably linked. See Sextant, right.

By 1723, standard units of measure had spread to § terrestrial mass and length.[d]

Francis Bacon's eliminative induction

[edit]"If a man will begin with certainties, he shall end in doubts; but if he will be content to begin with doubts, he shall end in certainties." —Francis Bacon (1605) The Advancement of Learning, Book 1, v, 8

Francis Bacon (1561–1626) entered Trinity College, Cambridge in April 1573, where he applied himself diligently to the several sciences as then taught, and came to the conclusion that the methods employed and the results attained were alike erroneous; he learned to despise the current Aristotelian philosophy. He believed philosophy must be taught its true purpose, and for this purpose a new method must be devised. With this conception in his mind, Bacon left the university.[51]

Bacon attempted to describe a rational procedure for establishing causation between phenomena based on induction. Bacon's induction was, however, radically different than that employed by the Aristotelians. As Bacon put it,

[A]nother form of induction must be devised than has hitherto been employed, and it must be used for proving and discovering not first principles (as they are called) only, but also the lesser axioms, and the middle, and indeed all. For the induction which proceeds by simple enumeration is childish. —Novum Organum section CV

Bacon's method relied on experimental histories to eliminate alternative theories.[69] Bacon explains how his method is applied in his Novum Organum (published 1620). In an example he gives on the examination of the nature of heat, Bacon creates two tables, the first of which he names "Table of Essence and Presence", enumerating the many various circumstances under which we find heat. In the other table, labelled "Table of Deviation, or of Absence in Proximity", he lists circumstances which bear resemblance to those of the first table except for the absence of heat. From an analysis of what he calls the natures (light emitting, heavy, colored, etc.) of the items in these lists we are brought to conclusions about the form nature, or cause, of heat. Those natures which are always present in the first table, but never in the second are deemed to be the cause of heat.

The role experimentation played in this process was twofold. The most laborious job of the scientist would be to gather the facts, or 'histories', required to create the tables of presence and absence. Such histories would document a mixture of common knowledge and experimental results. Secondly, experiments of light, or, as we might say, crucial experiments would be needed to resolve any remaining ambiguities over causes.

Bacon showed an uncompromising commitment to experimentation. Despite this, he did not make any great scientific discoveries during his lifetime. This may be because he was not the most able experimenter.[70] It may also be because hypothesising plays only a small role in Bacon's method compared to modern science.[71] Hypotheses, in Bacon's method, are supposed to emerge during the process of investigation, with the help of mathematics and logic. Bacon gave a substantial but secondary role to mathematics "which ought only to give definiteness to natural philosophy, not to generate or give it birth" (Novum Organum XCVI). An over-emphasis on axiomatic reasoning had rendered previous non-empirical philosophy impotent, in Bacon's view, which was expressed in his Novum Organum:

XIX. There are and can be only two ways of searching into and discovering truth. The one flies from the senses and particulars to the most general axioms, and from these principles, the truth of which it takes for settled and immoveable, proceeds to judgment and to the discovery of middle axioms. And this way is now in fashion. The other derives axioms from the senses and particulars, rising by a gradual and unbroken ascent, so that it arrives at the most general axioms last of all. This is the true way, but as yet untried.

In Bacon's utopian novel, The New Atlantis, the ultimate role is given for inductive reasoning:

Lastly, we have three that raise the former discoveries by experiments into greater observations, axioms, and aphorisms. These we call interpreters of nature.

Descartes

[edit]In 1619, René Descartes began writing his first major treatise on proper scientific and philosophical thinking, the unfinished Rules for the Direction of the Mind. His aim was to create a complete science that he hoped would overthrow the Aristotelian system and establish himself as the sole architect[72] of a new system of guiding principles for scientific research.

This work was continued and clarified in his 1637 treatise, Discourse on Method, and in his 1641 Meditations. Descartes describes the intriguing and disciplined thought experiments he used to arrive at the idea we instantly associate with him: I think therefore I am.

From this foundational thought, Descartes finds proof of the existence of a God who, possessing all possible perfections, will not deceive him provided he resolves "[...] never to accept anything for true which I did not clearly know to be such; that is to say, carefully to avoid precipitancy and prejudice, and to comprise nothing more in my judgment than what was presented to my mind so clearly and distinctly as to exclude all ground of methodic doubt."[73]

This rule allowed Descartes to progress beyond his own thoughts and judge that there exist extended bodies outside of his own thoughts. Descartes published seven sets of objections to the Meditations from various sources[74] along with his replies to them. Despite his apparent departure from the Aristotelian system, a number of his critics felt that Descartes had done little more than replace the primary premises of Aristotle with those of his own. Descartes says as much himself in a letter written in 1647 to the translator of Principles of Philosophy,

a perfect knowledge [...] must necessarily be deduced from first causes [...] we must try to deduce from these principles knowledge of the things which depend on them, that there be nothing in the whole chain of deductions deriving from them that is not perfectly manifest.[75]

And again, some years earlier, speaking of Galileo's physics in a letter to his friend and critic Mersenne from 1638,

without having considered the first causes of nature, [Galileo] has merely looked for the explanations of a few particular effects, and he has thereby built without foundations.[76]

Whereas Aristotle purported to arrive at his first principles by induction, Descartes believed he could obtain them using reason only. In this sense, he was a Platonist, as he believed in the innate ideas, as opposed to Aristotle's blank slate (tabula rasa), and stated that the seeds of science are inside us.[77]

Unlike Bacon, Descartes successfully applied his own ideas in practice. He made significant contributions to science, in particular in aberration-corrected optics. His work in analytic geometry was a necessary precedent to differential calculus and instrumental in bringing mathematical analysis to bear on scientific matters.

Galileo Galilei

[edit]

During the period of religious conservatism brought about by the Reformation and Counter-Reformation, Galileo Galilei unveiled his new science of motion. Neither the contents of Galileo's science, nor the methods of study he selected were in keeping with Aristotelian teachings. Whereas Aristotle thought that a science should be demonstrated from first principles, Galileo had used experiments as a research tool. Galileo nevertheless presented his treatise in the form of mathematical demonstrations without reference to experimental results. It is important to understand that this in itself was a bold and innovative step in terms of scientific method. The usefulness of mathematics in obtaining scientific results was far from obvious.[78] This is because mathematics did not lend itself to the primary pursuit of Aristotelian science: the discovery of causes.

Whether it is because Galileo was realistic about the acceptability of presenting experimental results as evidence or because he himself had doubts about the epistemological status of experimental findings is not known. Nevertheless, it is not in his Latin treatise on motion that we find reference to experiments, but in his supplementary dialogues written in the Italian vernacular. In these dialogues experimental results are given, although Galileo may have found them inadequate for persuading his audience. Thought experiments showing logical contradictions in Aristotelian thinking, presented in the skilled rhetoric of Galileo's dialogue were further enticements for the reader.

As an example, in the dramatic dialogue titled Third Day from his Two New Sciences, Galileo has the characters of the dialogue discuss an experiment involving two free falling objects of differing weight. An outline of the Aristotelian view is offered by the character Simplicio. For this experiment he expects that "a body which is ten times as heavy as another will move ten times as rapidly as the other". The character Salviati, representing Galileo's persona in the dialogue, replies by voicing his doubt that Aristotle ever attempted the experiment. Salviati then asks the two other characters of the dialogue to consider a thought experiment whereby two stones of differing weights are tied together before being released. Following Aristotle, Salviati reasons that "the more rapid one will be partly retarded by the slower, and the slower will be somewhat hastened by the swifter". But this leads to a contradiction, since the two stones together make a heavier object than either stone apart, the heavier object should in fact fall with a speed greater than that of either stone. From this contradiction, Salviati concludes that Aristotle must, in fact, be wrong and the objects will fall at the same speed regardless of their weight, a conclusion that is borne out by experiment.

In his 1991 survey of developments in the modern accumulation of knowledge such as this, Charles Van Doren[79] considers that the Copernican Revolution really is the Galilean Cartesian (René Descartes) or simply the Galilean revolution on account of the courage and depth of change brought about by the work of Galileo.

Isaac Newton

[edit]

Both Bacon and Descartes wanted to provide a firm foundation for scientific thought that avoided the deceptions of the mind and senses. Bacon envisaged that foundation as essentially empirical, whereas Descartes provides a metaphysical foundation for knowledge. If there were any doubts about the direction in which scientific method would develop, they were set to rest by the success of Isaac Newton. Implicitly rejecting Descartes' emphasis on rationalism in favor of Bacon's empirical approach, he outlines his four "rules of reasoning" in the Principia,

- We are to admit no more causes of natural things than such as are both true and sufficient to explain their appearances.

- Therefore to the same natural effects we must, as far as possible, assign the same causes.

- The qualities of bodies, which admit neither intension nor remission of degrees, and which are found to belong to all bodies within the reach of our experiments, are to be esteemed the universal qualities of all bodies whatsoever.

- In experimental philosophy we are to look upon propositions collected by general induction from phænomena as accurately or very nearly true, notwithstanding any contrary hypotheses that may be imagined, until such time as other phænomena occur, by which they may either be made more accurate, or liable to exceptions.[80]

But Newton also left an admonition about a theory of everything:

To explain all nature is too difficult a task for any one man or even for any one age. 'Tis much better to do a little with certainty, and leave the rest for others that come after you, than to explain all things.[81]

Newton's work became a model that other sciences sought to emulate, and his inductive approach formed the basis for much of natural philosophy through the 18th and early 19th centuries. Some methods of reasoning were later systematized by Mill's Methods (or Mill's canon), which are five explicit statements of what can be discarded and what can be kept while building a hypothesis. George Boole and William Stanley Jevons also wrote on the principles of reasoning.

Integrating deductive and inductive method

[edit]Attempts to systematize a scientific method were confronted in the mid-18th century by the problem of induction, a positivist logic formulation which, in short, asserts that nothing can be known with certainty except what is actually observed. David Hume took empiricism to the skeptical extreme; among his positions was that there is no logical necessity that the future should resemble the past, thus we are unable to justify inductive reasoning itself by appealing to its past success. Hume's arguments, of course, came on the heels of many, many centuries of excessive speculation upon excessive speculation not grounded in empirical observation and testing. Many of Hume's radically skeptical arguments were argued against, but not resolutely refuted, by Immanuel Kant's Critique of Pure Reason in the late 18th century.[82] Hume's arguments continue to hold a strong lingering influence and certainly on the consciousness of the educated classes for the better part of the 19th century when the argument at the time became the focus on whether or not the inductive method was valid.

Hans Christian Ørsted, (Ørsted is the Danish spelling; Oersted in other languages) (1777–1851) was heavily influenced by Kant, in particular, Kant's Metaphysische Anfangsgründe der Naturwissenschaft (Metaphysical Foundations of Natural Science).[83] The following sections on Ørsted encapsulate our current, common view of scientific method. His work appeared in Danish, most accessibly in public lectures, which he translated into German, French, English, and occasionally Latin. But some of his views go beyond Kant:

- "In order to achieve completeness in our knowledge of nature, we must start from two extremes, from experience and from the intellect itself. ... The former method must conclude with natural laws, which it has abstracted from experience, while the latter must begin with principles, and gradually, as it develops more and more, it becomes ever more detailed. Of course, I speak here about the method as manifested in the process of the human intellect itself, not as found in textbooks, where the laws of nature which have been abstracted from the consequent experiences are placed first because they are required to explain the experiences. When the empiricist in his regression towards general laws of nature meets the metaphysician in his progression, science will reach its perfection."[84]

Ørsted's "First Introduction to General Physics" (1811) exemplified the steps of observation,[85] hypothesis,[86] deduction[87] and experiment. In 1805, based on his researches on electromagnetism Ørsted came to believe that electricity is propagated by undulatory action (i.e., fluctuation). By 1820, he felt confident enough in his beliefs that he resolved to demonstrate them in a public lecture, and in fact observed a small magnetic effect from a galvanic circuit (i.e., voltaic circuit), without rehearsal;[88][89]

In 1831 John Herschel (1792–1871) published A Preliminary Discourse on the study of Natural Philosophy, setting out the principles of science. Measuring and comparing observations was to be used to find generalisations in "empirical laws", which described regularities in phenomena, then natural philosophers were to work towards the higher aim of finding a universal "law of nature" which explained the causes and effects producing such regularities. An explanatory hypothesis was to be found by evaluating true causes (Newton's "vera causae") derived from experience, for example evidence of past climate change could be due to changes in the shape of continents, or to changes in Earth's orbit. Possible causes could be inferred by analogy to known causes of similar phenomena.[90][91] It was essential to evaluate the importance of a hypothesis; "our next step in the verification of an induction must, therefore, consist in extending its application to cases not originally contemplated; in studiously varying the circumstances under which our causes act, with a view to ascertain whether their effect is general; and in pushing the application of our laws to extreme cases."[92]

William Whewell (1794–1866) regarded his History of the Inductive Sciences, from the Earliest to the Present Time (1837) to be an introduction to the Philosophy of the Inductive Sciences (1840) which analyzes the method exemplified in the formation of ideas. Whewell attempts to follow Bacon's plan for discovery of an effectual art of discovery. He named the hypothetico-deductive method (which Encyclopædia Britannica credits to Newton[93]); Whewell also coined the term scientist. Whewell examines ideas and attempts to construct science by uniting ideas to facts. He analyses induction into three steps:

- the selection of the fundamental idea, such as space, number, cause, or likeness

- a more special modification of those ideas, such as a circle, a uniform force, etc.

- the determination of magnitudes

Upon these follow special techniques applicable for quantity, such as the method of least squares, curves, means, and special methods depending on resemblance (such as pattern matching, the method of gradation, and the method of natural classification (such as cladistics). But no art of discovery, such as Bacon anticipated, follows, for "invention, sagacity, genius" are needed at every step.[94] Whewell's sophisticated concept of science had similarities to that shown by Herschel, and he considered that a good hypothesis should connect fields that had previously been thought unrelated, a process he called consilience. However, where Herschel held that the origin of new biological species would be found in a natural rather than a miraculous process, Whewell opposed this and considered that no natural cause had been shown for adaptation so an unknown divine cause was appropriate.[90]

John Stuart Mill (1806–1873) was stimulated to publish A System of Logic (1843) upon reading Whewell's History of the Inductive Sciences. Mill may be regarded as the final exponent of the empirical school of philosophy begun by John Locke, whose fundamental characteristic is the duty incumbent upon all thinkers to investigate for themselves rather than to accept the authority of others. Knowledge must be based on experience.[95]

In the mid-19th century Claude Bernard was also influential, especially in bringing the scientific method to medicine. In his discourse on scientific method, An Introduction to the Study of Experimental Medicine (1865), he described what makes a scientific theory good and what makes a scientist a true discoverer. Unlike many scientific writers of his time, Bernard wrote about his own experiments and thoughts, and used the first person.[96]

William Stanley Jevons' The Principles of Science: a treatise on logic and scientific method (1873, 1877) Chapter XII "The Inductive or Inverse Method", Summary of the Theory of Inductive Inference, states "Thus there are but three steps in the process of induction :-

- Framing some hypothesis as to the character of the general law.

- Deducing some consequences of that law.

- Observing whether the consequences agree with the particular tasks under consideration."

Jevons then frames those steps in terms of probability, which he then applied to economic laws. Ernest Nagel notes that Jevons and Whewell were not the first writers to argue for the centrality of the hypothetico-deductive method in the logic of science.[97]

Charles Sanders Peirce

[edit]In the late 19th century, Charles Sanders Peirce proposed a schema that would turn out to have considerable influence in the further development of scientific method generally. Peirce's work quickly accelerated the progress on several fronts. Firstly, speaking in broader context in "How to Make Our Ideas Clear" (1878),[98] Peirce outlined an objectively verifiable method to test the truth of putative knowledge on a way that goes beyond mere foundational alternatives, focusing upon both Deduction and Induction. He thus placed induction and deduction in a complementary rather than competitive context (the latter of which had been the primary trend at least since David Hume a century before). Secondly, and of more direct importance to scientific method, Peirce put forth the basic schema for hypothesis-testing that continues to prevail today. Extracting the theory of inquiry from its raw materials in classical logic, he refined it in parallel with the early development of symbolic logic to address the then-current problems in scientific reasoning. Peirce examined and articulated the three fundamental modes of reasoning that play a role in scientific inquiry today, the processes that are currently known as abductive, deductive, and inductive inference. Thirdly, he played a major role in the progress of symbolic logic itself – indeed this was his primary specialty.

Charles S. Peirce was also a pioneer in statistics. Peirce held that science achieves statistical probabilities, not certainties, and that chance, a veering from law, is very real. He assigned probability to an argument's conclusion rather than to a proposition, event, etc., as such. Most of his statistical writings promote the frequency interpretation of probability (objective ratios of cases), and many of his writings express skepticism about (and criticize the use of) probability when such models are not based on objective randomization.[99] Though Peirce was largely a frequentist, his possible world semantics introduced the "propensity" theory of probability. Peirce (sometimes with Jastrow) investigated the probability judgments of experimental subjects, pioneering decision analysis.

Peirce was one of the founders of statistics. He formulated modern statistics in "Illustrations of the Logic of Science" (1877–1878) and "A Theory of Probable Inference" (1883). With a repeated measures design, he introduced blinded, controlled randomized experiments (before Fisher). He invented an optimal design for experiments on gravity, in which he "corrected the means". He used logistic regression, correlation, and smoothing, and improved the treatment of outliers. He introduced terms "confidence" and "likelihood" (before Neyman and Fisher). (See the historical books of Stephen Stigler.) Many of Peirce's ideas were later popularized and developed by Ronald A. Fisher, Jerzy Neyman, Frank P. Ramsey, Bruno de Finetti, and Karl Popper.

Modern perspectives

[edit]Karl Popper (1902–1994) is generally credited with providing major improvements in the understanding of the scientific method in the mid-to-late 20th century. In 1934 Popper published The Logic of Scientific Discovery, which repudiated the by then traditional observationalist-inductivist account of the scientific method. He advocated empirical falsifiability as the criterion for distinguishing scientific work from non-science. According to Popper, scientific theory should make predictions (preferably predictions not made by a competing theory) which can be tested and the theory rejected if these predictions are shown not to be correct. Following Peirce and others, he argued that science would best progress using deductive reasoning as its primary emphasis, known as critical rationalism. His astute formulations of logical procedure helped to rein in the excessive use of inductive speculation upon inductive speculation, and also helped to strengthen the conceptual foundations for today's peer review procedures.[citation needed]

Ludwik Fleck, a Polish epidemiologist who was contemporary with Karl Popper but who influenced Kuhn and others with his Genesis and Development of a Scientific Fact (in German 1935, English 1979). Before Fleck, scientific fact was thought to spring fully formed (in the view of Max Jammer, for example), when a gestation period is now recognized to be essential before acceptance of a phenomenon as fact.[100]

Critics of Popper, chiefly Thomas Kuhn, Paul Feyerabend and Imre Lakatos, rejected the idea that there exists a single method that applies to all science and could account for its progress. In 1962 Kuhn published the influential book The Structure of Scientific Revolutions which suggested that scientists worked within a series of paradigms, and argued there was little evidence of scientists actually following a falsificationist methodology. Kuhn quoted Max Planck who had said in his autobiography, "a new scientific truth does not triumph by convincing its opponents and making them see the light, but rather because its opponents eventually die, and a new generation grows up that is familiar with it."[101]

A well quoted source on the subject of the scientific method and statistical models, George E. P. Box (1919–2013) wrote "Since all models are wrong the scientist cannot obtain a correct one by excessive elaboration. On the contrary following William of Occam he should seek an economical description of natural phenomena. Just as the ability to devise simple but evocative models is the signature of the great scientist, so over-elaboration and over-parameterization is often the mark of mediocrity" and "Since all models are wrong the scientist must be alert to what is importantly wrong. It is inappropriate to be concerned about mice when there are tigers abroad."[102]

These debates clearly show that there is no universal agreement as to what constitutes the "scientific method".[103] There remain, nonetheless, certain core principles that are the foundation of scientific inquiry today.[104]

Mention of the topic

[edit]In Quod Nihil Scitur (1581), Francisco Sanches refers to another book title, De modo sciendi (on the method of knowing). This work appeared in Spanish as Método universal de las ciencias.[64]

In 1833 Robert and William Chambers published their 'Chambers's information for the people'. Under the rubric 'Logic' we find a description of investigation that is familiar as scientific method,

Investigation, or the art of inquiring into the nature of causes and their operation, is a leading characteristic of reason [...] Investigation implies three things – Observation, Hypothesis, and Experiment [...] The first step in the process, it will be perceived, is to observe...[105]

In 1885, the words "Scientific method" appear together with a description of the method in Francis Ellingwood Abbot's 'Scientific Theism',

Now all the established truths which are formulated in the multifarious propositions of science have been won by the use of Scientific Method. This method consists in essentially three distinct steps (1) observation and experiment, (2) hypothesis, (3) verification by fresh observation and experiment.[106]

The Eleventh Edition of Encyclopædia Britannica did not include an article on scientific method; the Thirteenth Edition listed scientific management, but not method. By the Fifteenth Edition, a 1-inch article in the Micropædia of Britannica was part of the 1975 printing, while a fuller treatment (extending across multiple articles, and accessible mostly via the index volumes of Britannica) was available in later printings.[107]

Current issues

[edit]In the past few centuries, some statistical methods have been developed, for reasoning in the face of uncertainty, as an outgrowth of methods for eliminating error. This was an echo of the program of Francis Bacon's Novum Organum of 1620. Bayesian inference acknowledges one's ability to alter one's beliefs in the face of evidence. This has been called belief revision, or defeasible reasoning: the models in play during the phases of scientific method can be reviewed, revisited and revised, in the light of further evidence. This arose from the work of Frank P. Ramsey[108] (1903–1930), of John Maynard Keynes[109] (1883–1946), and earlier, of William Stanley Jevons[110][111] (1835–1882) in economics.

Science and pseudoscience

[edit]The question of how science operates and therefore how to distinguish genuine science from pseudoscience has importance well beyond scientific circles or the academic community. In the judicial system and in public policy controversies, for example, a study's deviation from accepted scientific practice is grounds for rejecting it as junk science or pseudoscience. However, the high public perception of science means that pseudoscience is widespread. An advertisement in which an actor wears a white coat and product ingredients are given Greek or Latin sounding names is intended to give the impression of scientific endorsement. Richard Feynman has likened pseudoscience to cargo cults in which many of the external forms are followed, but the underlying basis is missing: that is, fringe or alternative theories often present themselves with a pseudoscientific appearance to gain acceptance.[112]

See also

[edit]Notes and references

[edit]- ^ Peter Achinstein, "General Introduction" (pp. 1–5) to Science Rules: A Historical Introduction to Scientific Methods. Johns Hopkins University Press, 2004. ISBN 0-8018-7943-4

- ^ "Britannica". Archived from the original on 2020-03-17. Retrieved 2005-11-12.

- ^ Lloyd, G. E. R. "The development of empirical research", in his Magic, Reason and Experience: Studies in the Origin and Development of Greek Science.

- ^ a b A. Aaboe (2 May 1974). "Scientific Astronomy in Antiquity". Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society. 276 (1257): 21–42. Bibcode:1974RSPTA.276...21A. doi:10.1098/rsta.1974.0007. JSTOR 74272. S2CID 122508567.

- ^ "The cradle of mathematics is in Egypt." – Aristotle, Metaphysics, as cited on page 1 of Olaf Pedersen (1993) Early physics and astronomy: a historical introduction Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, revised edition

- ^ "There each man is a leech skilled beyond all human kind; yea, for they are of the race of Paeeon." – Homer, Odyssey book IV, acknowledges the skill of the ancient Egyptians in medicine.

- ^ a b Pingree, David (December 1992). "Hellenophilia versus the History of Science". Isis. 83 (4). University of Chicago Press: 554–563. Bibcode:1992Isis...83..554P. doi:10.1086/356288. JSTOR 234257. S2CID 68570164.

- ^ Rochberg, Francesca (October–December 1999). "Empiricism in Babylonian Omen Texts and the Classification of Mesopotamian Divination as Science". Journal of the American Oriental Society. 119 (4). American Oriental Society: 559–569. doi:10.2307/604834. JSTOR 604834.

- ^ Yves Gingras, Peter Keating, and Camille Limoges, Du scribe au savant: Les porteurs du savoir de l'antiquité à la révolution industrielle, Presses universitaires de France, 1998.

- ^ Harrison, Peter (2015). The Territories of Science and Religion. University of Chicago Press. p. 24. ISBN 9780226184487.

- ^ Oliver Leaman, Key Concepts in Eastern Philosophy. Routledge, 1999, page 269.

- ^ Kamal, M.M. (1998), "The Epistemology of the Carvaka Philosophy", Journal of Indian and Buddhist Studies, 46(2): pp. 13–16

- ^ Needham, Joseph; Wang Ling (1995) [1959]. Science and Civilisation in China: Volume 3. Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-05801-8. p. 171

- ^ Institute of Philosophy & Technology (16 Feb 2022) Carlo Rovelli on Anaximander and the Birth of Science Archived 10 April 2023 at the Wayback Machine summary 44:00

- ^ Barnes, Hellenistic Philosophy and Science, pp. 383–384

- ^ Gauch, Hugh G. (2003). Scientific Method in Practice. Cambridge University Press. p. 45. ISBN 978-0-521-01708-4. Retrieved 10 February 2015.

- ^ Hammond, p. 64, "Andronicus Rhodus"

- ^ "In the days when the Arabs inherited the culture of ancient Greece, Greek thought was chiefly interested in science, Athens was replaced by Alexandria, and Hellenism had an entirely "modem "outlook. This was an attitude with which Alexandria and its scholars were directly connected, but it was by no means confined to Alexandria. It was a logical outcome of the influence of Aristotle who before all else was a patient observer of nature, and was, in fact, the founder of modern science." Ch.1, Introduction —De Lacy O'Leary (1949), How Greek Science Passed to the Arabs, London: Routledge & Kegan Paul Ltd., ISBN 0-7100-1903-3

- ^ See Nominalism#The problem of universals for several approaches to this goal.

- ^ Aristotle (fl. 4th c. BCE, d. 322 BCE), History of Animals, including vivisection of the tortoise and chameleon. His theory of spontaneous generation was not experimentally disproved until Francesco Redi (1668).

- ^ Armand Leroi, Aristotle's Lagoon - Lesvos island - Greece Archived 2015-06-28 at the Wayback Machine name of Pyrrha lagoon, now called Kalloni, minute 5:06/57:55. His spontaneous generation disproved, minute 50:00/57:55. His lack of experiment, minute 51:00/57:55

- ^ Armand Leroi, following in Aristotle's footsteps, projects that Aristotle interviewed the fishermen of Lesbos to learn empirical details about the animals. (Leroi, Aristotle's Lagoon)

- ^ See: Aristotle's influence on Greek perception, which cites Annas, Julia Classical Greek Philosophy. In Boardman, John; Griffin, Jasper; Murray, Oswyn (ed.) The Oxford History of the Classical World. Oxford University Press: New York, 1986. ISBN 0-19-872112-9

- ^ a b c d e f g Asmis 1984

- ^ Madden, Edward H. (Apr., 1957) "Aristotle's Treatment of Probability and Signs" Philosophy of Science 24(2), pp. 167–172 JSTOR 185720 Archived 2017-02-19 at the Wayback Machine discusses Aristotle's enthymeme (70a, 5ff.) in Prior Analytics

- ^ David C. Lindberg (1980), Science in the Middle Ages, University of Chicago Press, p. 21, ISBN 0-226-48233-2

- ^ Holmyard, E. J. (1931), Makers of Chemistry, Oxford: Clarendon Press, p. 56

- ^ Plinio Prioreschi, "Al-Kindi, A Precursor of the Scientific Revolution" Archived 2021-05-23 at the Wayback Machine, Journal of the International Society for the History of Islamic Medicine, 2002 (2): 17–20 [17].

- ^ a b Alhazen, translated into English from German by M. Schwarz, from "Abhandlung über das Licht" (Treatise on Light – رسالة في الضوء), J. Baarmann (ed. 1882) Zeitschrift der Deutschen Morgenländischen Gesellschaft Vol 36 as referenced on p. 136 by Shmuel Sambursky (1974) Physical thought from the Presocratics to the Quantum Physicists ISBN 0-87663-712-8

- ^ D. C. Lindberg, Theories of Vision from al-Kindi to Kepler, (Chicago, Univ. of Chicago Pr., 1976), pp. 60–67.

- ^ Nader El-Bizri, "A Philosophical Perspective on Alhazen's Optics," Arabic Sciences and Philosophy, Vol. 15, Issue 2 (2005), pp. 189–218 (Cambridge University Press)

- ^ Nader El-Bizri, "Ibn al-Haytham," in Medieval Science, Technology, and Medicine: An Encyclopedia, eds. Thomas F. Glick, Steven J. Livesey, and Faith Wallis (New York – London: Routledge, 2005), pp. 237–240.

- ^ Alhazen (Ibn Al-Haytham) Critique of Ptolemy, translated by S. Pines, Actes X Congrès internationale d'histoire des sciences, Vol I Ithaca 1962, as referenced on p.139 of Shmuel Sambursky (ed. 1974) Physical Thought from the Presocratics to the Quantum Physicists ISBN 0-87663-712-8

- ^ p. 136, as quoted by Shmuel Sambursky (1974) Physical thought from the Presocratics to the Quantum Physicists ISBN 0-87663-712-8

- ^ Plott, C. (2000), Global History of Philosophy: The Period of Scholasticism, Motilal Banarsidass, p. 462, ISBN 81-208-0551-8

- ^ Alhazen; Smith, A. Mark (2001), Alhacen's Theory of Visual Perception: A Critical Edition, with English Translation and Commentary of the First Three Books of Alhacen's De Aspectibus, the Medieval Latin Version of Ibn al-Haytham's Kitab al-Manazir, Diane Publishing, pp. 372 & 408, ISBN 0-87169-914-1

- ^ Rashed, Roshdi (2007), "The Celestial Kinematics of Ibn al-Haytham", Arabic Sciences and Philosophy, 17, Cambridge University Press: 7–55 [19], doi:10.1017/S0957423907000355, S2CID 170934544:

"In reforming optics he, as it were, adopted positivism (before the term was invented): we do not go beyond experience, and we cannot be content to use pure concepts in investigating natural phenomena. Understanding of these cannot be acquired without mathematics. Thus, once he has assumed light is a material substance, Ibn al-Haytham does not discuss its nature further, but confines himself to considering its propagation and diffusion. In his optics the smallest parts of light, as he calls them, retain only properties that can be treated by geometry and verified by experiment; they lack all sensible qualities except energy."

- ^ a b c Sardar, Ziauddin (1998), "Science in Islamic philosophy", Islamic Philosophy, Routledge Encyclopedia of Philosophy, archived from the original on 2018-05-26, retrieved 2008-02-03

- ^ Mariam Rozhanskaya and I. S. Levinova (1996), "Statics", p. 642, in (Morelon & Rashed 1996, pp. 614–642):

"Using a whole body of mathematical methods (not only those inherited from the antique theory of ratios and infinitesimal techniques, but also the methods of the contemporary algebra and fine calculation techniques), Arabic scientists raised statics to a new, higher level. The classical results of Archimedes in the theory of the centre of gravity were generalized and applied to three-dimensional bodies, the theory of ponderable lever was founded and the 'science of gravity' was created and later further developed in medieval Europe. The phenomena of statics were studied by using the dynamic approach so that two trends – statics and dynamics – turned out to be inter-related within a single science, mechanics. The combination of the dynamic approach with Archimedean hydrostatics gave birth to a direction in science which may be called medieval hydrodynamics. [...] Numerous fine experimental methods were developed for determining the specific weight, which were based, in particular, on the theory of balances and weighing. The classical works of al-Biruni and al-Khazini can by right be considered as the beginning of the application of experimental methods in medieval science."

- ^ Glick, Thomas F.; Livesey, Steven John; Wallis, Faith (2005), Medieval Science, Technology, and Medicine: An Encyclopedia, Routledge, pp. 89–90, ISBN 0-415-96930-1

- ^ McGinnis, Jon (July 2003), "Scientific Methodologies in Medieval Islam", Journal of the History of Philosophy, 41 (3): 307–327, doi:10.1353/hph.2003.0033, S2CID 30864273, archived from the original on 2021-08-09, retrieved 2019-09-24

- ^ Lenn Evan Goodman (2003), Islamic Humanism, p. 155, Oxford University Press, ISBN 0-19-513580-6.

- ^ Lenn Evan Goodman (1992), Avicenna, p. 33, Routledge, ISBN 0-415-01929-X.

- ^ James Franklin (2001), The Science of Conjecture: Evidence and Probability Before Pascal, pp. 177–178, Johns Hopkins University Press, ISBN 0-8018-6569-7.

- ^ Dallal, Ahmad (2001–2002), The Interplay of Science and Theology in the Fourteenth-century Kalam, From Medieval to Modern in the Islamic World, Sawyer Seminar at the University of Chicago, archived from the original on 2012-02-10, retrieved 2008-02-02

- ^ Burnett, Charles (2001). "The Coherence of the Arabic-Latin Translation Program in Toledo in the Twelfth Century". Science in Context. 14 (1–2): 249–288. doi:10.1017/S0269889701000096. S2CID 143006568.

- ^ A. C. Crombie, Robert Grosseteste and the Origins of Experimental Science, 1100–1700, (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1971), pp. 52–60.

- ^ Cajori, Florian (1917). A History of Physics in Its Elementary Branches: Including the Evolution of Physical Laboratories. Macmillan.

- ^ Jeremiah Hackett, "Roger Bacon: His Life, Career, and Works," in Hackett, Roger Bacon and the Sciences, pp. 13–17.

- ^ "Roger Bacon", Encyclopædia Britannica, Eleventh Edition

- ^ a b Adamson, Robert (1911). . In Chisholm, Hugh (ed.). Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 3 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 155.

- ^ Instead of reading Aristotle directly from Greek texts, students of these texts would rely on summaries and translations of Aristotle's work, coupled with commentary by the translators, according to Elaine Limbrick, who cites Michel Reulos, "L'Enseignement d'Aristote dans les collèges au XVIe siècle" in Platon et Aristote à la Renaissance ed. J.-C. Margolin (Paris: Vrin, 1976) pp. 147–154:Sanches, Limbrick & Thomson 1988, p. 26

- ^ Edward Grant, The Foundations of Modern Science in the Middle Ages: Their Religious, Institutional, and Intellectual Contexts, (Cambridge: Cambridge Univ. Pr., 1996, pp. 164–167.

- ^ "Even Aristotle would have laughed at the stupidity of his commentators." — Vives 1531 attacks obscurity in Aristotle's works, as cited by Sanches, Limbrick & Thomson 1988, pp. 28–29

- ^ Galenus, Claudius (1519) Galenus methodus medendi, vel de morbis curandis, T. Linacro ... interprete, libri quatuordecim Lutetiae. as cited by Sanches, Limbrick & Thomson 1988, p. 301

- ^ Richard J. Durling (1961) "A Chronological Census of Renaissance Editions and Translations of Galen", in Journal of the Warburg and Courtald Institutes 24 pp. 242–243 as cited on p. 300 of Sanches, Limbrick & Thomson 1988

- ^ Niccolò Leoniceno (1509), De Plinii et aliorum erroribus liber apud Ferrara, as cited by Sanches, Limbrick & Thomson 1988, p. 13

- ^ Fuchs's book on the methods of Galen and Hippocrates became a standard medical text of 809 pages: Leonhart Fuchs (1560) Institutionum medicinae, sive methodi ad Hippocratis, Galeni, aliorumque veterum scripta recte intelligenda mire utiles libri quinque ... Editio secunda. Lugduni. As cited in Sanches, Limbrick & Thomson 1988, pp. 61 & 301.

- ^ Jodocus Willichius De methodo omnium artium et disciplinarum informanda opusculum Archived 2023-04-09 at the Wayback Machine An Informative Essay on the Method of All Arts and Disciplines (1550)

- ^ 'I have sometimes seen a verbose quibbler attempting to persuade some ignorant person that white was black; to which the latter replied, "I do not understand your reasoning, since I have not studied as much as you have; yet I honestly believe that white differs from black. But pray go on refuting me for just as long as you like." '— Sanches, Limbrick & Thomson 1988, p. 276

- ^ "Susanne Bobzien, "Aristotle's modal logic" Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy". Archived from the original on 2018-08-28. Retrieved 2012-06-29.

- ^ Sanches, Limbrick & Thomson 1988, p. 278.

- ^ "Since, as he had shown, nothing can be known, Sanches put forward a procedure, not to gain knowledge but to deal constructively with human experience. This procedure, for which he introduced the term (for the first time) scientific method, "Metodo universal de las ciencias," consists in patient, careful empirical research and cautious judgment and evaluation of the data we observe. This would not lead, as his contemporary Francis Bacon thought, to a key to knowledge of the world. But it would allow us to obtain the best information available. ...In advancing this limited or constructive view of science, Sanches was the first Renaissance sceptic to conceive of science in its modern form, as the fruitful activity about the study of nature that remained after one had given up the search for absolutely certain knowledge of the nature of things. Popkin 2003, p. 41"

- ^ a b Sanches, Limbrick & Thomson 1988, p. 292 lists De modo sciendi under the Unpublished, Lost, or Projected Works [of Francisco Sanches]. This work appeared in Spanish as Metodo universal de las ciencias, as cited by Guy Patin (1701) Naudeana et Patiniana pp. 72–73

- ^ Sanches, Limbrick & Thomson 1988, p. 290

- ^ "Kepler's Laws". hyperphysics.phy-astr.gsu.edu. Archived from the original on 2022-12-13. Retrieved 2022-12-13.

- ^ "Orbits and Kepler's Laws". NASA Solar System Exploration. 26 June 2008. Archived from the original on 2022-12-13. Retrieved 2022-12-13.

- ^ Jacques Cassini. (1720) De la grandeur et de la figure de la Terre Archived 2023-03-29 at the Wayback Machine On the size and features of Earth, pp. 14ff.

- ^ In this sense, it has been seen as a precursor to falsificationism of Charles Sanders Peirce and Karl Popper. However, Bacon believed his method would produce certain knowledge, similar to Peirce's view of scientific methods as ultimately approaching the truth; with the goal of attaining knowledge of the truth, Bacon's philosophy is less sceptical than Popper's philosophy.

- Bacon precedes Peirce in another sense – his reliance on doubt: "If a man will begin with certainties, he shall end in doubts; but if he will be content to begin with doubts he shall end in certainties." – Francis Bacon, The Advancement of Learning (1605), Book I, v, 8.

- ^ B. Gower, Scientific Method, An Historical and Philosophical Introduction, (Routledge, 1997), pp. 48–2.

- ^ B. Russell, History of Western Philosophy, (Routledge, 2000), pp. 529–3.

- ^ Descartes compares his work to that of an architect: "there is less perfection in works composed of several separate pieces and by difference masters, than those in which only one person has worked.", Discourse on Method and The Meditations, (Penguin, 1968), p. 35. (see too his letter to Mersenne (28. January 1641 [AT III, 297–298]).

- ^ This is the first of four rules Descartes resolved "never once to fail to observe", Discourse on Method and The Meditations, (Penguin, 1968), p. 41.

- ^ René Descartes, Meditations on First Philosophy: With Selections from the Objections and Replies, (Cambridge: Cambridge Univ. Pr., 2nd ed., 1996), pp. 63–107.

- ^ René Descartes, The Philosophical Writings of Descartes: Principles of Philosophy, Preface to French Edition, translated by J. Cottingham, R. Stoothoff, D. Murdoch (Cambridge: Cambridge Univ. Pr., 1985), vol. 1, pp. 179–189.

- ^ René Descartes, Oeuvres De Descartes, edited by Charles Adam and Paul Tannery (Paris: Librairie Philosophique J. Vrin, 1983), vol. 2, p. 380.

- ^ Koyré, Alexandre: Introduction a la Lecture de Platon, suivi de Entretiens sur Descartes, Gallimard, p. 203

- ^ For more about the role of mathematics in science around the time of Galileo see R. Feldhay, The Cambridge Companion to Galileo: The use and abuse of mathematical entities, (Cambridge: Cambridge Univ. Pr., 1998), pp. 80–133.

- ^ Van Doren, Charles. A History of Knowledge. (New York, Ballantine, 1991)

- ^ Rule IV, Philosophiae Naturalis Principia Mathematica#Rules of Reasoning in Philosophy:

- Newton states "This rule we must follow that the argument of induction may not be evaded by hypotheses", in the Motte translation (p. 400 in the Cajori revision, vol. 2)

- Newton's comment is also rendered as "This rule should be followed so that arguments based on induction may not be nullified by hypotheses" on p. 796 of Newton, Isaac (1999), Philosophiae Naturalis Principia Mathematica, University of California Press, ISBN 0-520-08817-4, 3rd ed.: 1687, 1713, 1726. From I. Bernard Cohen and Anne Whitman's 1999 translation, 974 pages.

- ^ Statement from unpublished notes for the Preface to Opticks (1704) quoted in Never at Rest: A Biography of Isaac Newton (1983) by Richard S. Westfall, p. 643

- ^ "Hume awakened Kant from his dogmatic slumbers". Archived from the original on 2020-07-31. Retrieved 2012-06-29.

- ^ Karen Jelved, Andrew D. Jackson, and Ole Knudsen, (1997) translators for Selected Scientific Works of Hans Christian Ørsted, ISBN 0-691-04334-5, p. x. The succeeding Ørsted references are contained in this book.

- ^ "Fundamentals of the Metaphysics of Nature Partly According to a New Plan", a special reprint of Hans Christian Ørsted (1799), Philosophisk Repertorium, printed by Boas Brünnich, Copenhagen, in Danish. Kirstine Meyer's 1920 edition of Ørsted's works, vol.I, pp. 33–78. English translation by Karen Jelved, Andrew D. Jackson, and Ole Knudsen, (1997) ISBN 0-691-04334-5 pp. 46–47.