Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

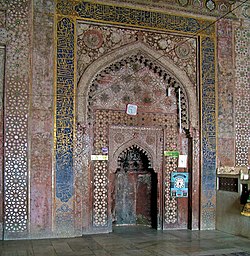

Islamic ornament

View on Wikipedia

Islamic ornament is the use of decorative forms and patterns in Islamic art and Islamic architecture. Its elements can be broadly divided into the arabesque, using curving plant-based elements, geometric patterns with straight lines or regular curves, and calligraphy, consisting of religious texts with stylized appearance, used both decoratively and to convey meaning. All three often involve elaborate interlacing in various mediums.

Islamic ornament has had a significant influence on European decorative art forms, especially as seen in the Western arabesque.

Overview

[edit]

Islamic art mostly avoids figurative images to avoid becoming objects of worship.[1][2] This aniconism in Islamic culture encouraged artists to explore non-figural art, creating a general aesthetic shift toward mathematically-based decoration.[3] Even before the preaching of Islam, the regions associated with the Islamic world today showed a preference for geometric and stylized vegetal decoration. As early as the fourth century, Byzantine architecture showcased influential forms of abstract ornament in stonework. Sasanian artists were influential in part through their experimentation with stucco as a decorative medium.

The Islamic geometric patterns derived from designs used in earlier cultures: Greek, Roman, and Sasanian. They are one of three forms of Islamic decoration, the others being the arabesque based on curving and branching plant forms, and Islamic calligraphy; all three are frequently used together, in mediums such as mosaic, stucco, brickwork, and ceramics, to decorate religious buildings and objects.[4][5][6][7]

Authors such as Keith Critchlow[a] argue that Islamic patterns are created to lead the viewer to an understanding of the underlying reality, rather than being mere decoration, as writers interested only in pattern sometimes imply.[8][9] In Islamic culture, the patterns are believed to be the bridge to the spiritual realm, the instrument to purify the mind and the soul.[10] David Wade[b] states that "Much of the art of Islam, whether in architecture, ceramics, textiles or books, is the art of decoration – which is to say, of transformation."[11] Wade argues that the aim is to transfigure, turning mosques "into lightness and pattern", while "the decorated pages of a Qur’an can become windows onto the infinite."[11] Against this, Doris Behrens-Abouseif[c] states in her book Beauty in Arabic Culture that a "major difference" between the philosophical thinking of medieval Europe and the Islamic world is exactly that the concepts of the good and the beautiful are separated in Arabic culture. She argues that beauty, whether in poetry or in the visual arts, was enjoyed "for its own sake, without commitment to religious or moral criteria".[12]

Arabesque

[edit]

The Islamic arabesque is a form of artistic decoration consisting of "rhythmic linear patterns of scrolling and interlacing foliage, tendrils" or plain lines,[13] often combined with other elements. It usually consists of a single design which can be 'tiled' or seamlessly repeated as many times as desired.[14] This technique, which emerged thanks to artistic interest in older geometric compositions in Late Antique art, made it possible for the viewer to imagine what the pattern would look like if it continued beyond its actual limits. This is a characteristic which made it distinctive to Islamic art.[15]

The fully "geometricized" arabesques appeared in the 10th century.[15] The vegetal forms commonly used within the patterns, such as acanthus leaves, grapes, and more abstract palmettes, were initially derived from Late Antique and Sasanian art. The Sasanians characteristic use of the scrolling vine as a decorative element derived from the Romans through Byzantine art. In the Islamic period, this vine scroll evolved into the arabesque.[16] The vine ornament which is popular in Islamic ornament is believed to come out of Hellenistic and early Christian art.[17][18] However, the vine scroll has experienced stylistic changes which has transformed the vine pattern into a more abstract ornament with only remnants of the Hellenistic model. Additional motifs, such as flowers, began to be added towards the 14th century.[15]

From the 14th century onward, the geometrically-configured arabesque began to be displaced by freer vegetal motifs inspired by Chinese art and by the Saz style that became popular in Ottoman art during the 16th century.[15]

Geometric patterns

[edit]

The historic world of Islamic art is widely known to be the most proficient in its use of geometric patterns for artistic expression.[16] Islamic geometric patterns developed in two different regions. Those locations being in the eastern regions of Persia, Transoxiana, and Khurasan, and in the western regions of Morocco and Andalusia.[19] The geometric designs in Islamic art are often built on combinations of repeated squares and circles, which may be overlapped and interlaced, as can arabesques, with which they are often combined, to form intricate and complex patterns, including a wide variety of tessellations. These may constitute the entire decoration, may form a framework for floral or calligraphic embellishments, or may retreat into the background around other motifs. The complexity and variety of patterns used evolved from simple stars and lozenges in the ninth century, through a variety of 6- to 13-point patterns by the 13th century, and finally to include also 14- and 16-point stars in the sixteenth century.[4][20][5][21] Geometric forms such as circles, squares, rhombs, dodecagons, and stars vary in their representation and configuration across the world of Islam.

Geometric patterns occur in a variety of forms in Islamic art and architecture including kilim carpets,[22] Persian girih[23] and western zellij tilework,[24][25] muqarnas decorative vaulting,[26] jali pierced stone screens,[27] ceramics,[28] leather,[29] stained glass,[30][31] woodwork,[32] and metalwork.[33][34]

Calligraphy

[edit]

Calligraphy is a central element of Islamic art, combining aesthetic appeal and religious message. Sometimes it is the dominant form of ornament; at other times it is combined with arabesque.[35] The importance of the written word in Islam ensured that epigraphic or calligraphic decoration played a prominent role in architecture.[36] Calligraphy is used to ornament buildings such as mosques, madrasas, and mausoleums; wooden objects such as caskets; and ceramics such as tiles and bowls.[37][38]

Epigraphic decoration can also indicate further political or religious messages through the selection of a textual program of inscriptions.[39] For example, the calligraphic inscriptions adorning the Dome of the Rock include quotations from the Qur'an that reference the miracle of Jesus and his human nature (e.g. Quran 19:33–35), the oneness of God (e.g. Qur'an 112), and the role of Muhammad as the "Seal of the Prophets", which have been interpreted as an attempt to announce the rejection of the Christian concept of the Holy Trinity and to proclaim the triumph of Islam over Christianity and Judaism.[40][41][42] Additionally, foundation inscriptions on buildings commonly indicate its founder or patron, the date of its construction, the name of the reigning sovereign, and other information.[36]

The earliest examples of epigraphic inscriptions in Islamic art demonstrate a more unplanned approach in which calligraphy is not integrated with other decoration.[43] In the 10th century, a new approach to writing emerged. Ibn Muqla is known as the originator of the khatt al-mansub, or proportioned script style.[44] "Khatt," meaning the "marking out," emphasized calligraphic writing's physical demarcation of space. This concept of rationalizing space is inherent in Islamic ornament.[43] By the 9th and 10th centuries inscriptions were fully integrated into the rest of an object or building's decorative program, and by the 14th century they became the dominant decorative feature on many objects.[43] The most common style of script during the early period was Kufic, in which straight angular lines dominated. In monumental inscriptions, certain flourishes were added over time to create variations such as "floriated" Kufic (in which flower or tendril forms spring from the letters) or "knotted" Kufic (in which some letters form interlacing knots).[45] However, the elaboration of Kufic scripts also made them less legible, which led to the adoption of rounder "cursive" scripts in architectural decoration, such as Naskh, Thuluth, and others. These scripts first appeared on monuments in the 11th century, initially for religious inscriptions but then for other inscriptions as well. Cursive scripts underwent further elaborations over the following centuries while Kufic was relegated to a secondary role. Inscriptions became longer and more crowded as more information was included and more titles were added to the names of patrons.[45]

Influence on Western ornament

[edit]

A Western style of ornament based on Islamic arabesque developed in Europe, starting in late 15th century Venice; it has been called either moresque or western arabesque. It has been used in a great variety of the decorative arts, especially in book design and bookbinding.[46] More recently, William Morris of the Arts and Crafts movement was influenced by all three types of Islamic ornament.[47]

Theories of Islamic ornament

[edit]This section needs additional citations for verification. (December 2022) |

The representation of pattern is one of the earliest forms of artistic expression; however, scientific and theoretical studies on pattern are a relatively recent development. The systematic study of their properties and significance emerged in the late 19th century. Theories on ornament can be located in the writings of Alois Reigl, William Morris, John Ruskin, Carl Semper, and Viollet-le-Duc.

Oleg Grabar is one of the theorists to engage with ornament's capacity to evoke thought and interpretation. He argues that ornament is used not merely as embellishment but an intermediary for making and seeing. Furthermore, its decorative qualities seem to complete an object by providing it with quality. This "quality" is the feeling transmitted through ornament's visual messages.

Owen Jones, in his book The Grammar of Ornament (1856), proposes theories on color, geometry, and abstraction. One of his guiding principles states that all ornament is based on a geometric construction.[48]

Ernst Gombrich emphasizes the practical effects of ornament as framing, filling, and linking.[49] He deems the most meaningful aspects of art to be non-ornamental, which stems from a preference to Western representational art. Geometric pattern in Islamic ornament involves this filling of space, technically described as "'tessellation through isometry.'"[50] The primary objective for geometric patterns "filling" of space is to enhance it. In his book,The Meditation on Ornament, Oleg Grabar departs from Gombrich's European-influenced position to show how ornament can be the subject of a design. He differentiates between filling a space with design, and transforming a space through design.

Grabar calls attention to the "iconophoric quality" of ornament. His use of the word "iconophoric" connotes "indicative" or "expressive." Regarding ornament for its own sake undermines its subjectivity. Geometric forms can be fashioned as subjects through their ability to communicate or enhance iconographic, semiotic, or symbolic meaning. Ornament in the Islamic work is used to convey the essence of an identifiable message or specific messages themselves. The richly textured geometric forms in the Alhambra function as a passageway, an essence, for viewers to meditate on life and afterlife.[50] One example of the use of geometry to indicate a specific message is visible over the entrance of one of the Kharraqan towers, where star-shaped polygons frame the word "Allah" (God).

The development of vegetal ornament from Egypt, the ancient Near East, and the Hellenistic world culminated in the Islamic arabesque.[3] Vegetal ornament is the suggestion of evocation of life as opposed to the representation of it. Its organic, rhythmic lines create an essence of growth and movement.

A common misconception in understanding the arabesque is resigning it to purely religious messages. This implies that the Islamic use of ornament emerged as a stylistic response to a rejection of idol or icon worship. Although ornament is used as a vehicle towards sacred contemplation and union with God, it is not confined to this function.

Notes

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Bouaissa, Malikka (27 July 2013). "The crucial role of geometry in Islamic art". Al Arte Magazine. Archived from the original on 27 March 2019. Retrieved 1 December 2015.

- ^ Bonner, Jay (2017). Islamic geometric patterns : their historical development and traditional methods of construction. New York: Springer. p. 1. ISBN 978-1-4419-0216-0. OCLC 1001744138.

- ^ a b Bier, Carol (Sep 2008). "Art and Mithãl: Reading Geometry as Visual Commentary". Iranian Studies. 41 (4): 491–509. doi:10.1080/00210860802246176. JSTOR 25597484. S2CID 171003353.

- ^ a b "Geometric Patterns in Islamic Art". Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History. Metropolitan Museum of Art. Retrieved 1 December 2015.

- ^ a b Hankin, Ernest Hanbury (1925). The Drawing of Geometric Patterns in Saracenic Art. Memoirs of the Archaeological Survey of India No. 15. Government of India Central Publication Branch.

- ^ Baer 1998, p. 41.

- ^ Clevenot 2017, pp. 7–8, 63–112.

- ^ Critchlow, Keith (1976). Islamic Patterns : an analytical and cosmological approach. Thames and Hudson. ISBN 0-500-27071-6.

- ^ Field, Robert (1998). Geometric Patterns from Islamic Art & Architecture. Tarquin Publications. ISBN 978-1-899618-22-4.

- ^ Ahuja, Mangho; Loeb, A. L. (1995). "Tessellations in Islamic Calligraphy". Leonardo. 28 (1): 41–45. doi:10.2307/1576154. JSTOR 1576154. S2CID 191368443.

- ^ a b Wade, David. "The Evolution of Style". Pattern in Islamic Art. Retrieved 6 September 2024.

Much of the art of Islam, whether in architecture, ceramics, textiles or books, is the art of decoration – which is to say, of transformation. The aim, however, is never merely to ornament, but rather to transfigure. ... The vast edifices of mosques are transformed into lightness and pattern; the decorated pages of a Qur'an can become windows onto the infinite. Perhaps most importantly, the Word, expressed in endless calligraphic variations, always conveys the impression that it is more enduring than the objects on which it is inscribed.

- ^ Behrens-Abouseif, Doris (1999). Beauty in Arabic Culture. Markus Wiener. pp. 7–8. ISBN 978-1-558-76199-5.

- ^ Fleming, John; Honour, Hugh (1977). Dictionary of the Decorative Arts. Penguin. ISBN 978-0-670-82047-4.

- ^ Robinson, Francis (1996). The Cambridge Illustrated History of the Islamic World. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-66993-1.

- ^ a b c d Bloom & Blair 2009, pp. 65–66, Chapter: Arabesque

- ^ a b Irwin, Robert (1997). Islamic Art in Context. New York, N.Y.: Henry N. Abrams. pp. 20–70. ISBN 0-8109-2710-1.

- ^ Dimand, Maurice S. (1937). "Studies in Islamic Ornament: I. Some Aspects of Omaiyad and Early 'Abbāsid Ornament". Ars Islamica. 4: 293–337. ISSN 1939-6406. JSTOR 25167044.

- ^ "The Heraldic Style", Problems of Style, Princeton University Press, pp. 41–47, 2018-12-04, doi:10.2307/j.ctv7r40hw.9, S2CID 239603192, retrieved 2022-12-11

- ^ BONNER, JAY (2018). ISLAMIC GEOMETRIC PATTERNS : their historical development and traditional methods of ... construction. SPRINGER-VERLAG NEW YORK. ISBN 978-1-4939-7921-9. OCLC 1085181820.

- ^ Broug, Eric (2008). Islamic Geometric Patterns. Thames and Hudson. pp. 183–185, 193. ISBN 978-0-500-28721-7.

- ^ Abdullahi, Yahya; Bin Embi, Mohamed Rashid (2013). "Evolution of Islamic geometric patterns". Frontiers of Architectural Research. 2 (2): 243–251. doi:10.1016/j.foar.2013.03.002.

- ^ Thompson, Muhammad; Begum, Nasima. "Islamic Textile Art and how it is Misunderstood in the West – Our Personal Views". Salon du Tapis d'Orient. Retrieved 3 December 2015.

- ^ "Gereh-Sazi". Tebyan. 20 August 2011. Retrieved 4 December 2015.

- ^ Bloom & Blair 2009, p. 201, Chapter: Architecture; X. Decoration; B. Tiles

- ^ Njoku, Raphael Chijioke (2006). Culture and Customs of Morocco. Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 58. ISBN 978-0-313-33289-0.

- ^ Tabbaa, Yasser. "The Muqarnas Dome: Its Origin and Meaning". Archnet. pp. 61–74. Retrieved 9 September 2024.

- ^ "Unit 3: Geometric Design in Islamic Art: Image 15" (PDF). Metropolitan Museum of Art. p. 78. Retrieved 6 September 2024.

- ^ "Geometric Decoration and the Art of the Book. Ceramics". Museum with no Frontiers. Retrieved 6 September 2024.

- ^ "Geometric Decoration and the Art of the Book. Leather". Museum with no Frontiers. Retrieved 6 September 2024.

- ^ King, David C. King (2006). Azerbaijan. Marshall Cavendish. p. 99. ISBN 978-0-7614-2011-8.

- ^ Sharifov, Azad (1998). "Shaki Paradise in the Caucasus Foothills". Azerbaijan International. 6 (2): 28–35.

- ^ Gereh-Sāzī. Encyclopaedia Iranica. Retrieved 2 December 2015.

- ^ Baer, Eva (1983). Metalwork in Medieval Islamic Art. SUNY Press. pp. 122–132. ISBN 978-0-87395-602-4.

- ^ Gibb, Sir Hamilton Alexander Rosskeen (1954). The Encyclopaedia of Islam. Brill Archive. pp. 990–992. GGKEY:N71HHP1UY5E.

- ^ Department of Islamic Art. "Calligraphy in Islamic Art" In Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art (October 2001)

- ^ a b Bloom & Blair 2009, Chapter: Architecture; X. Decoration

- ^ Mozzati, Luca (2010). "Calligraphy: The Form of the Divine Word". Islamic Art. Prestel. pp. 52–59. ISBN 978-3-7913-4455-3.

- ^ "Bowl with Kufic Calligraphy". Brooklyn Museum. Retrieved 30 September 2020.

- ^ Capilla, Susana (2018). "The Visual Construction of the Umayyad Caliphate in Al-Andalus through the Great Mosque of Cordoba". Arts. 7 (3): 10. doi:10.3390/arts7030036. ISSN 2076-0752.

- ^ Grabar, Oleg (2006). The Dome of the Rock. Harvard University Press. pp. 91–95, 119. ISBN 978-0-674-02313-0.

- ^ Bloom & Blair 2009, Chapter: Jerusalem.

- ^ Hattstein, Markus; Delius, Peter, eds. (2011). Islam: Art and Architecture. H. F. Ullman. p. 64. ISBN 9783848003808.

- ^ a b c Bloom & Blair 2009, pp. 73–74, Chapter: Ornament and pattern; I. Motifs and their transformation; D. Epigraphic

- ^ Sourdel, Dominique (1971). "Ibn Muḳla". In Lewis, B.; Ménage, V. L.; Pellat, Ch. & Schacht, J. (eds.). The Encyclopaedia of Islam, Second Edition. Volume III: H–Iram. Leiden: E. J. Brill. pp. 886–887. OCLC 495469525.

- ^ a b Bloom & Blair 2009, pp. 210–212, Chapter: Architecture; X. Decoration; F. Epigraphy

- ^ Harthan, John P. (1961). Bookbinding (2nd ed.). HMSO for the Victoria and Albert Museum. pp. 10–12. OCLC 220550025.

- ^ "A Place in Pattern: Islamic Art and its Influence in British Arts & Crafts". William Morris Society. 2020. Archived from the original on 3 October 2020. Retrieved 14 October 2020.

- ^ Jones, Owen; Bedford, Francis; Waring, J. B; Westwood, J. O; Wyatt, M. Digby (1856). The grammar of ornament. London: Published by Day and Son. doi:10.5479/sil.387695.39088012147732.

- ^ Gombrich, E. H. (Ernst Hans), 1909–2001. The story of art. ISBN 978-0-7148-3247-0. OCLC 1254557050.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ a b Brett, David; Grabar, Oleg (1993). "The Mediation of Ornament". Circa (review) (65): 63. doi:10.2307/25557837. ISSN 0263-9475. JSTOR 25557837.

Sources

[edit]- Baer, Eva (1998). Islamic Ornament. New York University Press. ISBN 0-8147-1329-7.

- Bloom, Jonathan M.; Blair, Sheila S., eds. (2009). The Grove Encyclopedia of Islamic Art and Architecture. Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780195309911.

- Clevenot, Dominique (2017). Ornament and Decoration in Islamic Architecture. Thames & Hudson. ISBN 978-0-500-34332-6. OCLC 961005036.