Recent from talks

Contribute something

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Crane (machine)

View on WikipediaThis article needs additional citations for verification. (November 2011) |

A crane is a machine used to move materials both vertically and horizontally, utilizing a system of a boom, hoist, wire ropes or chains, and sheaves for lifting and relocating heavy objects within the swing of its boom. The device uses one or more simple machines, such as the lever and pulley, to create mechanical advantage to do its work. Cranes are commonly employed in transportation for the loading and unloading of freight, in construction for the movement of materials, and in manufacturing for the assembling of heavy equipment.

The first known crane machine was the shaduf, a water-lifting device that was invented in ancient Mesopotamia (modern Iraq) and then appeared in ancient Egyptian technology. Construction cranes later appeared in ancient Greece, where they were powered by men or animals (such as donkeys), and used for the construction of buildings. Larger cranes were later developed in the Roman Empire, employing the use of human treadwheels, permitting the lifting of heavier weights. In the High Middle Ages, harbour cranes were introduced to load and unload ships and assist with their construction—some were built into stone towers for extra strength and stability. The earliest cranes were constructed from wood, but cast iron, iron and steel took over with the coming of the Industrial Revolution.

For many centuries, power was supplied by the physical exertion of men or animals, although hoists in watermills and windmills could be driven by the harnessed natural power. The first mechanical power was provided by steam engines, the earliest steam crane being introduced in the 18th or 19th century, with many remaining in use well into the late 20th century.[1] Modern cranes usually use internal combustion engines or electric motors and hydraulic systems to provide a much greater lifting capability than was previously possible, although manual cranes are still utilized where the provision of power would be uneconomic.

There are many different types of cranes, each tailored to a specific use. Sizes range from the smallest jib cranes, used inside workshops, to the tallest tower cranes, used for constructing high buildings. Mini-cranes are also used for constructing high buildings, to facilitate constructions by reaching tight spaces. Large floating cranes are generally used to build oil rigs and salvage sunken ships.[citation needed]

Some lifting machines do not strictly fit the above definition of a crane, but are generally known as cranes, such as stacker cranes and loader cranes.

Etymology

[edit]Cranes were so called from the resemblance to the long neck of the bird, cf. Ancient Greek: γερανός, French grue.[2]

History

[edit]Ancient Near East

[edit]The first type of crane machine was the shadouf, which had a lever mechanism and was used to lift water for irrigation.[3][4][5] It was invented in Mesopotamia (modern Iraq) circa 3000 BC.[3][4] The shadouf subsequently appeared in ancient Egyptian technology circa 2000 BC.[5][6]

Ancient Greece

[edit]

A crane for lifting heavy loads was developed by the Ancient Greeks in the late 6th century BC.[7] The archaeological record shows that no later than c. 515 BC distinctive cuttings for both lifting tongs and lewis irons begin to appear on stone blocks of Greek temples. Since these holes point at the use of a lifting device, and since they are to be found either above the center of gravity of the block, or in pairs equidistant from a point over the center of gravity, they are regarded by archaeologists as the positive evidence required for the existence of the crane.[7]

The introduction of the winch and pulley hoist soon led to a widespread replacement of ramps as the main means of vertical motion. For the next 200 years, Greek building sites witnessed a sharp reduction in the weights handled, as the new lifting technique made the use of several smaller stones more practical than fewer larger ones. In contrast to the archaic period with its pattern of ever-increasing block sizes, Greek temples of the classical age like the Parthenon invariably featured stone blocks weighing less than 15–20 metric tons. Also, the practice of erecting large monolithic columns was practically abandoned in favour of using several column drums.[8]

Although the exact circumstances of the shift from the ramp to the crane technology remain unclear, it has been argued that the volatile social and political conditions of Greece were more suitable to the employment of small, professional construction teams than of large bodies of unskilled labour, making the crane preferable to the Greek polis over the more labour-intensive ramp which had been the norm in the autocratic societies of Egypt or Assyria.[8]

The first unequivocal literary evidence for the existence of the compound pulley system appears in the Mechanical Problems (Mech. 18, 853a32–853b13) attributed to Aristotle (384–322 BC), but perhaps composed at a slightly later date. Around the same time, block sizes at Greek temples began to match their archaic predecessors again, indicating that the more sophisticated compound pulley must have found its way to Greek construction sites by then.[9]

Roman Empire

[edit]

The heyday of the crane in ancient times came during the Roman Empire, when construction activity soared and buildings reached enormous dimensions. The Romans adopted the Greek crane and developed it further. There is much available information about their lifting techniques, thanks to rather lengthy accounts by the engineers Vitruvius (De Architectura 10.2, 1–10) and Heron of Alexandria (Mechanica 3.2–5). There are also two surviving reliefs of Roman treadwheel cranes, with the Haterii tombstone from the late first century AD being particularly detailed.

The simplest Roman crane, the trispastos, consisted of a double-beam jib, a winch, a rope, and a block containing three pulleys. Having thus a mechanical advantage of 3:1, it has been calculated that a single man working the winch could raise 150 kg (330 lb) (3 pulleys x 50 kg or 110 lb = 150), assuming that 50 kg (110 lb) represent the maximum effort a man can exert over a longer time period. Heavier crane types featured five pulleys (pentaspastos) or, in case of the largest one, a set of three by five pulleys (Polyspastos) and came with two, three or four masts, depending on the maximum load. The polyspastos, when worked by four men at both sides of the winch, could readily lift 3,000 kg (6,600 lb) (3 ropes x 5 pulleys x 4 men x 50 kg or 110 lb = 3,000 kg or 6,600 lb). If the winch was replaced by a treadwheel, the maximum load could be doubled to 6,000 kg (13,000 lb) at only half the crew, since the treadwheel possesses a much bigger mechanical advantage due to its larger diameter. This meant that, in comparison to the construction of the ancient Egyptian pyramids, where about 50 men were needed to move a 2.5 ton[which?] stone block up the ramp (50 kg (110 lb) per person), the lifting capability of the Roman polyspastos proved to be 60 times higher (3,000 kg or 6,600 lb per person).[10]

However, numerous extant Roman buildings which feature much heavier stone blocks than those handled by the polyspastos indicate that the overall lifting capability of the Romans went far beyond that of any single crane. At the temple of Jupiter at Baalbek, for instance, the architrave blocks weigh up to 60 tons each, and one corner cornice block even over 100 tons, all of them raised to a height of about 19 m (62.3 ft).[9] In Rome, the capital block of Trajan's Column weighs 53.3 tons, which had to be lifted to a height of about 34 m (111.5 ft) (see construction of Trajan's Column).[11]

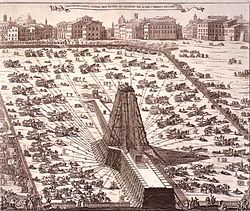

It is assumed that Roman engineers lifted these extraordinary weights by two measures (see picture below for comparable Renaissance technique): First, as suggested by Heron, a lifting tower was set up, whose four masts were arranged in the shape of a quadrangle with parallel sides, not unlike a siege tower, but with the column in the middle of the structure (Mechanica 3.5).[12] Second, a multitude of capstans were placed on the ground around the tower, for, although having a lower leverage ratio than treadwheels, capstans could be set up in higher numbers and run by more men (and, moreover, by draught animals).[13] This use of multiple capstans is also described by Ammianus Marcellinus (17.4.15) in connection with the lifting of the Lateranense obelisk in the Circus Maximus (c. 357 AD). The maximum lifting capability of a single capstan can be established by the number of lewis iron holes bored into the monolith. In case of the Baalbek architrave blocks, which weigh between 55 and 60 tons, eight extant holes suggest an allowance of 7.5 ton per lewis iron, that is per capstan.[14] Lifting such heavy weights in a concerted action required a great amount of coordination between the work groups applying the force to the capstans.

Middle Ages

[edit]During the High Middle Ages, the treadwheel crane was reintroduced on a large scale after the technology had fallen into disuse in western Europe with the demise of the Western Roman Empire.[16] The earliest reference to a treadwheel (magna rota) reappears in archival literature in France about 1225,[17] followed by an illuminated depiction in a manuscript of probably also French origin dating to 1240.[18] In navigation, the earliest uses of harbor cranes are documented for Utrecht in 1244, Antwerp in 1263, Bruges in 1288 and Hamburg in 1291,[19] while in England the treadwheel is not recorded before 1331.[20]

Generally, vertical transport could be done more safely and inexpensively by cranes than by customary methods. Typical areas of application were harbors, mines, and, in particular, building sites where the treadwheel crane played a pivotal role in the construction of the lofty Gothic cathedrals. Nevertheless, both archival and pictorial sources of the time suggest that newly introduced machines like treadwheels or wheelbarrows did not completely replace more labor-intensive methods like ladders, hods and handbarrows. Rather, old and new machinery continued to coexist on medieval construction sites[21] and harbors.[19]

Apart from treadwheels, medieval depictions also show cranes to be powered manually by windlasses with radiating spokes, cranks and by the 15th century also by windlasses shaped like a ship's wheel. To smooth out irregularities of impulse and get over 'dead-spots' in the lifting process flywheels are known to be in use as early as 1123.[22]

The exact process by which the treadwheel crane was reintroduced is not recorded,[17] although its return to construction sites has undoubtedly to be viewed in close connection with the simultaneous rise of Gothic architecture. The reappearance of the treadwheel crane may have resulted from a technological development of the windlass from which the treadwheel structurally and mechanically evolved. Alternatively, the medieval treadwheel may represent a deliberate reinvention of its Roman counterpart drawn from Vitruvius' De architectura which was available in many monastic libraries. Its reintroduction may have been inspired, as well, by the observation of the labor-saving qualities of the waterwheel with which early treadwheels shared many structural similarities.[20]

Structure and placement

[edit]The medieval treadwheel was a large wooden wheel turning around a central shaft with a treadway wide enough for two workers walking side by side. While the earlier 'compass-arm' wheel had spokes directly driven into the central shaft, the more advanced "clasp-arm" type featured arms arranged as chords to the wheel rim,[23] giving the possibility of using a thinner shaft and providing thus a greater mechanical advantage.[24]

Contrary to a popularly held belief, cranes on medieval building sites were neither placed on the extremely lightweight scaffolding used at the time nor on the thin walls of the Gothic churches which were incapable of supporting the weight of both hoisting machine and load. Rather, cranes were placed in the initial stages of construction on the ground, often within the building. When a new floor was completed, and massive tie beams of the roof connected the walls, the crane was dismantled and reassembled on the roof beams from where it was moved from bay to bay during construction of the vaults.[25] Thus, the crane "grew" and "wandered" with the building with the result that today all extant construction cranes in England are found in church towers above the vaulting and below the roof, where they remained after building construction for bringing material for repairs aloft.[26]

Less frequently, medieval illuminations also show cranes mounted on the outside of walls with the stand of the machine secured to putlogs.[27]

Mechanics and operation

[edit]

In contrast to modern cranes, medieval cranes and hoists — much like their counterparts in Greece and Rome[28] — were primarily capable of a vertical lift, and not used to move loads for a considerable distance horizontally as well.[25] Accordingly, lifting work was organized at the workplace in a different way than today. In building construction, for example, it is assumed that the crane lifted the stone blocks either from the bottom directly into place,[25] or from a place opposite the centre of the wall from where it could deliver the blocks for two teams working at each end of the wall.[28] Additionally, the crane master who usually gave orders at the treadwheel workers from outside the crane was able to manipulate the movement laterally by a small rope attached to the load.[29] Slewing cranes which allowed a rotation of the load and were thus particularly suited for dockside work appeared as early as 1340.[30] While ashlar blocks were directly lifted by sling, lewis or devil's clamp (German Teufelskralle), other objects were placed before in containers like pallets, baskets, wooden boxes or barrels.[31]

It is noteworthy that medieval cranes rarely featured ratchets or brakes to forestall the load from running backward.[32] This curious absence is explained by the high friction force exercised by medieval tread-wheels which normally prevented the wheel from accelerating beyond control.[29]

Harbour usage

[edit]

According to the "present state of knowledge" unknown in antiquity, stationary harbor cranes are considered a new development of the Middle Ages.[19] The typical harbor crane was a pivoting structure equipped with double treadwheels. These cranes were placed docksides for the loading and unloading of cargo where they replaced or complemented older lifting methods like see-saws, winches and yards.[19]

Two different types of harbor cranes can be identified with a varying geographical distribution: While gantry cranes, which pivoted on a central vertical axle, were commonly found at the Flemish and Dutch coastside, German sea and inland harbors typically featured tower cranes where the windlass and treadwheels were situated in a solid tower with only jib arm and roof rotating.[15] Dockside cranes were not adopted in the Mediterranean region and the highly developed Italian ports where authorities continued to rely on the more labor-intensive method of unloading goods by ramps beyond the Middle Ages.[33]

Unlike construction cranes where the work speed was determined by the relatively slow progress of the masons, harbor cranes usually featured double treadwheels to speed up loading. The two treadwheels whose diameter is estimated to be 4 m or larger were attached to each side of the axle and rotated together.[19] Their capacity was 2–3 tons, which apparently corresponded to the customary size of marine cargo.[19] Today, according to one survey, fifteen treadwheel harbor cranes from pre-industrial times are still extant throughout Europe.[34] Some harbour cranes were specialised at mounting masts to newly built sailing ships, such as in Gdańsk, Cologne and Bremen.[15] Beside these stationary cranes, floating cranes, which could be flexibly deployed in the whole port basin came into use by the 14th century.[15]

A sheer hulk (or shear hulk) was used in shipbuilding and repair as a floating crane in the days of sailing ships, primarily to place the lower masts of a ship under construction or repair. Booms known as sheers were attached to the base of a hulk's lower masts or beam, supported from the top of those masts. Blocks and tackle were then used in such tasks as placing or removing the lower masts of the vessel under construction or repair. These lower masts were the largest and most massive single timbers aboard a ship, and erecting them without the assistance of either a sheer hulk or land-based masting sheer was extremely difficult.[35]

The concept of sheer hulks originated with the Royal Navy in the 1690s, and persisted in Britain until the early nineteenth century. Most sheer hulks were decommissioned warships; Chatham, built in 1694, was the first of only three purpose-built vessels.[36] There were at least six sheer hulks in service in Britain at any time throughout the 1700s. The concept spread to France in the 1740s with the commissioning of a sheer hulk at the port of Rochefort.[37]

Early modern age

[edit]A lifting tower similar to that of the ancient Romans was used to great effect by the Renaissance architect Domenico Fontana in 1586 to relocate the 361 t heavy Vatican obelisk in Rome.[38] From his report, it becomes obvious that the coordination of the lift between the various pulling teams required a considerable amount of concentration and discipline, since, if the force was not applied evenly, the excessive stress on the ropes would make them rupture.[39]

Cranes were also used domestically during this period. The chimney or fireplace crane was used to swing pots and kettles over the fire and the height was adjusted by a trammel.[40]

- Examples of early modern cranes

-

Erection of the Vatican obelisk in 1586 by means of a lifting tower

-

An 1868 photo of a 15th-century crane on the unfinished south tower of Cologne Cathedral

-

Fireplace crane

Industrial revolution

[edit]

With the onset of the Industrial Revolution the first modern cranes were installed at harbours for loading cargo. In 1838, the industrialist and businessman William Armstrong designed a water-powered hydraulic crane. His design used a ram in a closed cylinder that was forced down by a pressurized fluid entering the cylinder and a valve regulated the amount of fluid intake relative to the load on the crane.[41] This mechanism, the hydraulic jigger, then pulled on a chain to lift the load.

In 1845 a scheme was set in motion to provide piped water from distant reservoirs to the households of Newcastle. Armstrong was involved in this scheme and he proposed to Newcastle Corporation that the excess water pressure in the lower part of town could be used to power one of his hydraulic cranes for the loading of coal onto barges at the Quayside. He claimed that his invention would do the job faster and more cheaply than conventional cranes. The corporation agreed to his suggestion, and the experiment proved so successful that three more hydraulic cranes were installed on the Quayside.[42]

The success of his hydraulic crane led Armstrong to establish the Elswick works at Newcastle, to produce his hydraulic machinery for cranes and bridges in 1847. His company soon received orders for hydraulic cranes from Edinburgh and Northern Railways and from Liverpool Docks, as well as for hydraulic machinery for dock gates in Grimsby. The company expanded from a workforce of 300 and an annual production of 45 cranes in 1850, to almost 4,000 workers producing over 100 cranes per year by the early 1860s.[42]

Armstrong spent the next few decades constantly improving his crane design; his most significant innovation was the hydraulic accumulator. Where water pressure was not available on site for the use of hydraulic cranes, Armstrong often built high water towers to provide a supply of water at pressure. However, when supplying cranes for use at New Holland on the Humber Estuary, he was unable to do this, because the foundations consisted of sand. He eventually produced the hydraulic accumulator, a cast-iron cylinder fitted with a plunger supporting a very heavy weight. The plunger would slowly be raised, drawing in water, until the downward force of the weight was sufficient to force the water below it into pipes at great pressure. This invention allowed much larger quantities of water to be forced through pipes at a constant pressure, thus increasing the crane's load capacity considerably.[43]

One of his cranes, commissioned by the Italian Navy in 1883 and in use until the mid-1950s, is still standing in Venice, where it is now in a state of disrepair.[44]

Mechanical principles

[edit]This section needs additional citations for verification. (October 2024) |

There are three major considerations in the design of cranes. First, the crane must be able to lift the weight of the load; second, the crane must not topple; third, the crane must not fail structurally.

- Examples of Mechanical principles

-

A tower crane can "swing" its boom left and right, "dolly" its car (or traveler) in and out, and lift and lower its load

-

Failed crane in Sermetal Shipyard, former Ishikawajima do Brasil – Rio de Janeiro, caused by a lack of maintenance and misuse of the equipment

-

Cranes can mount many different fittings, such as hooks, blocks, spreader bars, and "choker" lines, depending on load (left). Cranes can be remote-controlled from the ground, allowing much more precise control, at the expense of the view from atop the crane (right).

Stability

[edit]For stability, the sum of all moments about the base of the crane must be close to zero so that the crane does not overturn.[45] In practice, the magnitude of load that is permitted to be lifted (called the "rated load" in the US) is some value less than the load that will cause the crane to tip, thus providing a safety margin.

Under United States standards for mobile cranes, the stability-limited rated load for a crawler crane is 75% of the tipping load. The stability-limited rated load for a mobile crane supported on outriggers is 85% of the tipping load. These requirements, along with additional safety-related aspects of crane design, are established by the American Society of Mechanical Engineers in the volume ASME B30.5-2018 Mobile and Locomotive Cranes.

Standards for cranes mounted on ships or offshore platforms are somewhat stricter because of the dynamic load on the crane due to vessel motion. Additionally, the stability of the vessel or platform must be considered.

For stationary pedestal or kingpost mounted cranes, the moment produced by the boom, jib, and load is resisted by the pedestal base or kingpost. Stress within the base must be less than the yield stress of the material or the crane will fail.

Dynamic Lift Factor

[edit]

Overview

[edit]The dynamic lift factor (DLF), also known as the design dynamic factor, is a critical parameter in the crane design and operation. It accounts for the dynamic effects that can increase the load on a crane's structure and components during lifting operations. These effects include:

- Hoisting acceleration and deceleration of the load, which is a significant factor;

- Crane movement such as slewing or luffing;

- Load swinging;

- Wind forces acting on the crane, the load and the rigging; and

- Operator error or other unexpected events.

The DLF for a new crane design can be determined with analytical calculations and mathematical models following the relevant design specifications. If available, data from previous tests of similar crane types can be used to estimate the DLF. More sophisticated methods, such as finite element analysis or other simulation techniques, may also be used to model the crane's behavior under various loading conditions, as deemed appropriate by the designer or certifying authority.To verify the actual DLF, control load tests can be conducted on the completed crane using instrumentation such as load cells, accelerometers, and strain gauges. This process is usually part of the crane's type approval.

In offshore lifting, where the crane and/or lifted object are on a floating vessel, the DLF is higher compared to onshore lifts because of the additional movement caused by wave action.[46] This motion introduces additional acceleration forces and necessitates increased hoisting and lowering speeds to minimize the risk of repeated collisions when the load is near the deck. Additionally, the DLF increases further when lifting objects that are underwater or going through the splash zone.[47] The wind speeds tend to be higher than onshore as well.

Though actual DLF values are determined through crane tests under representative operational conditions, design specifications can be used for guidance. The values vary according to the specification, which reflects the type of crane and its usage. Here are some example typical values:

- Jib cranes typically have a lower DLF () compared to traveling gantry cranes () because they are stiffer;[46][48]

- For grab cranes, the DLF can increase by 20% to 30% reflecting the shock loads caused by the release of the lifted material;[46] and

- The DLF generally decreases as the mass of the lifted object increases, as cranes tend to operate at lower velocities with heavier loads to ensure safety and stability. For offshore lifts, the DLF typically decreases from 1.3 at 100 tonnes to 1.1 at 2500 tonnes.[49]

Formulas

[edit]The methods for determining the DLF vary in the different crane specifications. The following formulas are examples from one specification.[46]

The working load (suspended load) is the total weight that a crane is designed to safely lift under normal operating conditions. It is[46]

where

- is the working load,

- is the acceleration of gravity,

- is the maximum lifted mass, which is also called the crane working load limit (WLL) or safe working load (SWL), and

- is the mass of lifting appliances or parts of the crane that move with the lifted mass.

The DLF is then used as a multiplier to determine the force applied to the crane structure and components[46]

where

- is the design force, and

- is the DLF.

The DLF can then be calculated using[46]

where

- is relative velocity between lifted object and hook at the time of pick-up, and

- is the stiffness of the crane system at the hook.

The relative velocity is dependent on the crane's operational requirements and the system stiffness at the hook can be determined by calculation or load deflection tests.

Types

[edit]The crane types outlined in this section are categorized based on their primary area of application:

Construction

[edit]Truck-mounted

[edit]The most basic truck-mounted crane configuration is a "boom truck" or "lorry loader", which features a rear-mounted rotating telescopic-boom crane mounted on a commercial truck chassis.[50][51]

Larger, heavier duty, purpose-built "truck-mounted" cranes are constructed in two parts: the carrier, often called the lower, and the lifting component, which includes the boom, called the upper. These are mated together through a turntable, allowing the upper to swing from side to side. These modern hydraulic truck cranes are usually single-engine machines, with the same engine powering the undercarriage and the crane. The upper is usually powered via hydraulics run through the turntable from the pump mounted on the lower. In older model designs of hydraulic truck cranes, there were two engines. One in the lower pulled the crane down the road and ran a hydraulic pump for the outriggers and jacks. The one in the upper ran the upper through a hydraulic pump of its own. Many older operators favor the two-engine system due to leaking seals in the turntable of aging newer design cranes. Hiab invented the world's first hydraulic truck mounted crane in 1947.[52] The name, Hiab, comes from the commonly used abbreviation of Hydrauliska Industri AB, a company founded in Hudiksvall, Sweden 1944 by Eric Sundin, a ski manufacturer who saw a way to utilize a truck's engine to power loader cranes through the use of hydraulics.

Generally, these cranes are able to travel on highways, eliminating the need for special equipment to transport the crane unless weight or other size constrictions are in place such as local laws. If this is the case, most larger cranes are equipped with either special trailers to help spread the load over more axles or are able to disassemble to meet requirements. An example is counterweights. Often a crane will be followed by another truck hauling the counterweights that are removed for travel. In addition some cranes are able to remove the entire upper. However, this is usually only an issue in a large crane and mostly done with a conventional crane such as a Link-Belt HC-238. When working on the job site, outriggers are extended horizontally from the chassis then vertically to level and stabilize the crane while stationary and hoisting. Many truck cranes have slow-travelling capability (a few miles per hour) while suspending a load. Great care must be taken not to swing the load sideways from the direction of travel, as most anti-tipping stability then lies in the stiffness of the chassis suspension. Most cranes of this type also have moving counterweights for stabilization beyond that provided by the outriggers. Loads suspended directly aft are the most stable, since most of the weight of the crane acts as a counterweight. Factory-calculated charts (or electronic safeguards) are used by crane operators to determine the maximum safe loads for stationary (outriggered) work as well as (on-rubber) loads and travelling speeds.

Truck cranes range in lifting capacity from about 14.5 short tons (12.9 long tons; 13.2 t) to about 2,240 short tons (2,000 long tons; 2,032 t).[53][54] Although most only rotate about 180 degrees, the more expensive truck mounted cranes can turn a full 360 degrees.

- Examples of truck mounted cranes

-

Automobile crane of the Railway Troops of Russia

-

Truck mounted crane building a bridge

-

A truck-mounted crane in road travel configuration

Loader

[edit]

A loader crane (also called a knuckle-boom crane or articulating crane) is a hydraulically powered articulated arm fitted to a truck or trailer, and is used for loading/unloading the vehicle cargo. The numerous jointed sections can be folded into a small space when the crane is not in use. One or more of the sections may be telescopic. Often the crane will have a degree of automation and be able to unload or stow itself without an operator's instruction.

Unlike most cranes, the operator must move around the vehicle to be able to view his load; hence modern cranes may be fitted with a portable cabled or radio-linked control system to supplement the crane-mounted hydraulic control levers.

In the United Kingdom and Canada, this type of crane is often known colloquially as a "Hiab", partly because this manufacturer invented the loader crane and was first into the UK market, and partly because the distinctive name was displayed prominently on the boom arm.[55]

A rolloader crane is a loader crane mounted on a chassis with wheels. This chassis can ride on the trailer. Because the crane can move on the trailer, it can be a light crane, so the trailer is allowed to transport more goods.

Telescopic

[edit]

A telescopic crane has a boom that consists of a number of tubes fitted one inside the other. A hydraulic cylinder or other powered mechanism extends or retracts the tubes to increase or decrease the total length of the boom. These types of booms are often used for short term construction projects, rescue jobs, lifting boats in and out of the water, etc. The relative compactness of telescopic booms makes them adaptable for many mobile applications.

Though not all telescopic cranes are mobile cranes, many of them are truck-mounted.

A telescopic tower crane has a telescopic mast and often a superstructure (jib) on top so that it functions as a tower crane. Some telescopic tower cranes also have a telescopic jib.

Rough-terrain

[edit]

A rough terrain crane has a boom mounted on an undercarriage atop four rubber tires that is designed for off-road pick-and-carry operations. Outriggers are used to level and stabilize the crane for hoisting.[56]

These telescopic cranes are single-engine machines, with the same engine powering the undercarriage and the crane, similar to a crawler crane. The engine is usually mounted in the undercarriage rather than in the upper, as with crawler crane. Most have 4 wheel drive and 4 wheel steering for traversing tighter and slicker terrain than a standard truck crane, with less site prep.

All-terrain

[edit]

An all-terrain crane is a hybrid combining the roadability of a truck-mounted and on-site maneuverability of a rough-terrain crane. It can both travel at speed on public roads and maneuver on rough terrain at the job site using all-wheel and crab steering.

AT's have 2–12 axles and are designed for lifting loads up to 2,000 tonnes (2,205 short tons; 1,968 long tons).[57]

Crawler

[edit]

A crawler crane has its boom mounted on an undercarriage fitted with a set of crawler tracks that provide both stability and mobility. Crawler cranes range in lifting capacity from about 40 to 4,000 long tons (44.8 to 4,480.0 short tons; 40.6 to 4,064.2 t) as seen from the XGC88000 crawler crane.[58]

The main advantage of a crawler crane is its ready mobility and use, since the crane is able to operate on sites with minimal improvement and stable on its tracks without outriggers. Wide tracks spread the weight out over a great area and are far better than wheels at traversing soft ground without sinking in. A crawler crane is also capable of traveling with a load. Its main disadvantage is its weight, making it difficult and expensive to transport. Typically a large crawler must be disassembled at least into boom and cab and moved by trucks, rail cars or ships to its next location.[59]

Pick-and-carry

[edit]

A pick and carry crane is similar to a mobile crane in that is designed to travel on public roads; however, pick and carry cranes have no stabiliser legs or outriggers and are designed to lift the load and carry it to its destination, within a small radius, then be able to drive to the next job. Pick and carry cranes are popular in Australia, where large distances are encountered between job sites. One popular manufacturer in Australia was Franna, who have since been bought by Terex, and now all pick and carry cranes are commonly called "Frannas", even though they may be made by other manufacturers. Nearly every medium- and large-sized crane company in Australia has at least one and many companies have fleets of these cranes. The capacity range is between 10 and 40 t (9.8 and 39.4 long tons; 11 and 44 short tons) as a maximum lift, although this is much less as the load gets further from the front of the crane. Pick and carry cranes have displaced the work usually completed by smaller truck cranes, as the set-up time is much quicker. Many steel fabrication yards also use pick and carry cranes, as they can "walk" with fabricated steel sections and place these where required with relative ease.

Smaller pick and carry cranes may be based on an articulated tractor chassis, with the boom mounted over the front wheels. In Australia these are popularly known as "wobbly cranes".[60]

Carry-deck

[edit]A carry deck crane is a small 4 wheel crane with a 360-degree rotating boom placed right in the centre and an operators cab located at one end under this boom. The rear section houses the engine and the area above the wheels is a flat deck. Very much an American invention the Carry deck can hoist a load in a confined space and then load it on the deck space around the cab or engine and subsequently move to another site. The Carry Deck principle is the American version of the pick and carry crane and both allow the load to be moved by the crane over short distances.

Telescopic handler

[edit]Telescopic handlers are forklift-like trucks that have a set of forks mounted on a telescoping extendable boom like a crane. Early telescopic handlers only lifted in one direction and did not rotate;[61] however, several of the manufacturers have designed telescopic handlers that rotate 360 degrees through a turntable and these machines look almost identical to the Rough Terrain Crane. These new 360-degree telescopic handler/crane models have outriggers or stabiliser legs that must be lowered before lifting; however, their design has been simplified so that they can be more quickly deployed. These machines are often used to handle pallets of bricks and install frame trusses on many new building sites and they have eroded much of the work for small telescopic truck cranes. Many of the world's armed forces have purchased telescopic handlers and some of these are the much more expensive fully rotating types. Their off-road capability and their on site versatility to unload pallets using forks, or lift like a crane make them a valuable piece of machinery.

Block-setting crane

[edit]

A block-setting crane is a form of crane. They were used for installing the large stone blocks used to build breakwaters, moles and stone piers.

Tower

[edit]In 1949, Hans Liebherr built the first mobile tower crane, the TK10.[62][63]

Tower cranes are a modern form of balance crane that consist of the same basic parts. Fixed to the ground on a concrete slab (and sometimes attached to the sides of structures), tower cranes often give the best combination of height and lifting capacity and are used in the construction of tall buildings. The base is then attached to the mast which gives the crane its height. Further, the mast is attached to the slewing unit (gear and motor) that allows the crane to rotate. On top of the slewing unit there are three main parts which are: the long horizontal jib (working arm), shorter counter-jib, and the operator's cab.

Optimization of tower crane location in the construction sites has an important effect on material transportation costs of a project,[64] but site operators need to ensure they assess where the jib will oversail the property of other landowners and tenants as it rotates over the site. Under English law a landowner also owns the airspace above their property and developers will need to agree terms with adjacent property owners before oversailing their land.[65]

The long horizontal jib is the part of the crane that carries the load. The counter-jib carries a counterweight, usually of concrete blocks, while the jib suspends the load to and from the center of the crane. The crane operator either sits in a cab at the top of the tower or controls the crane by radio remote control from the ground. In the first case the operator's cab is most usually located at the top of the tower attached to the turntable, but can be mounted on the jib, or partway down the tower. The lifting hook is operated by the crane operator using electric motors to manipulate wire rope cables through a system of sheaves. The hook is located on the long horizontal arm to lift the load which also contains its motor.

In order to hook and unhook the loads, the operator usually works in conjunction with a signaller (known as a "dogger", "rigger" or "swamper"). They are most often in radio contact, and always use hand signals. The rigger or dogger directs the schedule of lifts for the crane, and is responsible for the safety of the rigging and loads.

Tower cranes can achieve a height under hook of over 100 metres.[66]

- Examples of tower cranes

-

Tower crane atop Mont Blanc

-

Tower crane cabin

-

Tower crane with "luffing" jib

-

A tower crane rotates on its axis before lowering the lifting hook.

-

Teleoperation tower cranes at a prefabricated framed construction site

Components

[edit]Tower cranes are used extensively in construction and other industry to hoist and move materials. There are many types of tower cranes. Although they are different in type, the main parts are the same, as follows:

- Mast: the main supporting tower of the crane. It is made of steel trussed sections that are connected together during installation.

- Slewing unit: the slewing unit sits at the top of the mast. This is the engine that enables the crane to rotate.

- Operating cabin: on most tower cranes the operating cabin sits just above the slewing unit. It contains the operating controls, load-movement indicator system (LMI), scale, anemometer, etc.

- Jib: the jib, or operating arm, extends horizontally from the crane. A "luffing" jib is able to move up and down; a fixed jib has a rolling trolley car that runs along the underside to move loads horizontally.

- Counter jib: holds counterweights, hoist motor, hoist drum and the electronics. (In many older tower crane designs the hoisting devices and electronics were located in the mast foot.) [67]

- Hoist winch: the hoist winch assembly consists of the hoist winch (motor, gearbox, hoist drum, hoist rope, and brakes), the hoist motor controller, and supporting components, such as the platform. Many tower cranes have transmissions with two or more speeds.

- Hook: the hook is used to connect the material to the crane, suspended from the hoist rope either at the tip (on luffing jib cranes) or routed through the trolley (on hammerhead cranes).

- Weights: Large, moveable concrete counterweights are mounted toward the rear of the counterdeck, to compensate for the weight of the goods lifted and keep the center of gravity over the supporting tower.[68]

Assembly

[edit]A tower crane is usually assembled by a telescopic jib (mobile) crane of greater reach (also see "self-erecting crane" below) and in the case of tower cranes that have risen while constructing very tall skyscrapers, a smaller crane (or derrick) will often be lifted to the roof of the completed tower to dismantle the tower crane afterwards, which may be more difficult than the installation.[69]

Tower cranes can be operated by remote control, removing the need for the crane operator to sit in a cab atop the crane.

Operation

[edit]Each model and distinctive style of tower crane has a predetermined lifting chart that can be applied to any radii available, depending on its configuration. Similar to a mobile crane, a tower crane may lift an object of far greater mass closer to its center of rotation than at its maximum radius. An operator manipulates several levers and pedals to control each function of the crane.

Safety

[edit]When a tower crane is used in proximity to buildings, roads, power lines, or other tower cranes, a tower crane anti-collision system is used. This operator support system reduces the risk of a dangerous interaction occurring between a tower crane and another structure.

In some countries, such as France, tower crane anti-collision systems are mandatory.[70]

Self-erecting tower cranes

[edit]

Generally a type of pedestrian operated tower crane, self-erecting tower cranes are transported as a single unit and can be assembled by a qualified technician without the assistance of a larger mobile crane. They are bottom slewing cranes that stand on outriggers, have no counter jib, have their counterweights and ballast at the base of the mast, cannot climb themselves, have a reduced capacity compared to standard tower cranes, and seldom have an operator's cabin.

In some cases, smaller self-erecting tower cranes may have axles permanently fitted to the tower section to make maneuvering the crane onsite easier.

Tower cranes can also use a hydraulic-powered jack frame to raise themselves to add new tower sections without any additional other cranes assisting beyond the initial assembly stage. This is how it can grow to nearly any height needed to build the tallest skyscrapers when tied to a building as the building rises. The maximum unsupported height of a tower crane is around 265 ft.[71] For a video of a crane getting taller, see "Crane Building Itself" on YouTube.[72]

For another animation of such a crane in use, see "SAS Tower Construction Simulation" on YouTube.[73] Here, the crane is used to erect a scaffold, which, in turn, contains a gantry to lift sections of a bridge spire.

Climbing crane

[edit]

Many tower cranes are designed to "jump" in stages, effectively lifting themselves to the next level. A specialty example of a climbing crane was introduced by Lagerwey Wind and Enercon[This paragraph needs citation(s)] to construct a wind turbine tower, where instead of erecting a large crane a smaller climbing crane can raise itself with the structure's construction, lift the generator housing to its top, add the rotor blades, then climb down.

Cargo handling

[edit]Rubber-tyred gantry crane

[edit]

Reach stacker

[edit]

A reach stacker is a vehicle used for handling intermodal cargo containers in small terminals or medium-sized ports. Reach stackers are able to transport a container short distances very quickly and pile them in various rows depending on its access.

Sidelifter

[edit]

A sidelifter crane is a road-going truck or semi-trailer, able to hoist and transport ISO standard containers. Container lift is done with parallel crane-like hoists, which can lift a container from the ground or from a railway vehicle.

Travel lift

[edit]A travel lift (also called a boat gantry crane, or boat crane) is a crane with two rectangular side panels joined by a single spanning beam at the top of one end. The crane is mobile with four groups of steerable wheels, one on each corner. These cranes allow boats with masts or tall super structures to be removed from the water and transported around docks or marinas.[74] Not to be confused mechanical device used for transferring a vessel between two levels of water, which is also called a boat lift.

Straddle carrier

[edit]A Straddle carrier moves and stacks intermodal containers.

Industrial

[edit]Ring

[edit]

Ring cranes are some of the largest and heaviest land-based cranes ever designed. A ring-shaped track support the main superstructure allowing for extremely heavy loads (up to thousands of tonnes).

Hammerhead

[edit]

The "hammerhead", or giant cantilever, crane is a fixed-jib crane consisting of a steel-braced tower on which revolves a large, horizontal, double cantilever; the forward part of this cantilever or jib carries the lifting trolley, the jib is extended backwards in order to form a support for the machinery and counterbalancing weight. In addition to the motions of lifting and revolving, there is provided a so-called "racking" motion, by which the lifting trolley, with the load suspended, can be moved in and out along the jib without altering the level of the load. Such horizontal movement of the load is a marked feature of later crane design.[75] These cranes are generally constructed in large sizes and can lift up to 350 tons.[76]

The design of Hammerkran evolved first in Germany around the turn of the 19th century and was adopted and developed for use in British shipyards to support the battleship construction program from 1904 to 1914. The ability of the hammerhead crane to lift heavy weights was useful for installing large pieces of battleships such as armour plate and gun barrels. Giant cantilever cranes were also installed in naval shipyards in Japan and in the United States. The British government also installed a giant cantilever crane at the Singapore Naval Base (1938) and later a copy of the crane was installed at Garden Island Naval Dockyard in Sydney (1951). These cranes provided repair support for the battle fleet operating far from Great Britain.

In the British Empire, the engineering firm Sir William Arrol & Co. was the principal manufacturer of giant cantilever cranes; the company built a total of fourteen. Among the sixty built in the world, few remain; seven in England and Scotland of about fifteen worldwide.[77]

The Titan Clydebank is one of the four Scottish cranes on the River Clyde and preserved as a tourist attraction.

Level luffing

[edit]Normally a crane with a hinged jib will tend to have its hook also move up and down as the jib moves (or luffs). A level luffing crane is a crane of this common design, but with an extra mechanism to keep the hook at the same level when the jib is pivoted in or out.

Overhead

[edit]

An overhead crane, also known as a bridge crane, is a type of crane where the hook-and-line mechanism runs along a horizontal beam that itself runs along two widely separated rails. Often it is in a long factory building and runs along rails along the building's two long walls. It is similar to a gantry crane. Overhead cranes typically consist of either a single beam or a double beam construction. These can be built using typical steel beams or a more complex box girder type. Pictured on the right is a single bridge box girder crane with the hoist and system operated with a control pendant. Double girder bridge are more typical when needing heavier capacity systems from 10 tons[which?] and above. The advantage of the box girder type configuration results in a system that has a lower deadweight yet a stronger overall system integrity. Also included would be a hoist to lift the items, the bridge, which spans the area covered by the crane, and a trolley to move along the bridge.

The most common overhead crane use is in the steel industry. At every step of the manufacturing process, until it leaves a factory as a finished product, steel is handled by an overhead crane. Raw materials are poured into a furnace by crane, hot steel is stored for cooling by an overhead crane, the finished coils are lifted and loaded onto trucks and trains by overhead crane, and the fabricator or stamper uses an overhead crane to handle the steel in his factory. The automobile industry uses overhead cranes for handling of raw materials. Smaller workstation cranes handle lighter loads in a work-area, such as CNC mill or saw.

Almost all paper mills use bridge cranes for regular maintenance requiring removal of heavy press rolls and other equipment. The bridge cranes are used in the initial construction of paper machines because they facilitate installation of the heavy cast iron paper drying drums and other massive equipment, some weighing as much as 70 tons.

In many instances the cost of a bridge crane can be largely offset with savings from not renting mobile cranes in the construction of a facility that uses a lot of heavy process equipment.

This electric overhead traveling crane is most common type of overhead crane, found in many factories. These cranes are electrically operated by a control pendant, radio/IR remote pendant, or from an operator cabin attached to the crane.

Gantry

[edit]

A gantry crane has a hoist in a fixed machinery house or on a trolley that runs horizontally along rails, usually fitted on a single beam (mono-girder) or two beams (twin-girder). The crane frame is supported on a gantry system with equalized beams and wheels that run on the gantry rail, usually perpendicular to the trolley travel direction. These cranes come in all sizes, and some can move very heavy loads, particularly the extremely large examples used in shipyards or industrial installations. A special version is the container crane (or "Portainer" crane, named by the first manufacturer), designed for loading and unloading ship-borne containers at a port.

Most container cranes are of this type.

Jib

[edit]

A jib crane is a type of crane - not to be confused with a crane rigged with a jib to extend its main boom - where a horizontal member (jib or boom), supporting a moveable hoist, is fixed to a wall or to a floor-mounted pillar. Jib cranes are used in industrial premises and on military vehicles. The jib may swing through an arc, to give additional lateral movement, or be fixed. Similar cranes, often known simply as hoists, were fitted on the top floor of warehouse buildings to enable goods to be lifted to all floors.

Bulk-handling

[edit]

Bulk-handling cranes are designed from the outset to carry a shell grab or bucket, rather than using a hook and a sling. They are used for bulk cargoes, such as coal, minerals, scrap metal etc.

Stacker

[edit]

A crane with a forklift type mechanism used in automated (computer-controlled) warehouses (known as an automated storage and retrieval system (AS/RS)). The crane moves on a track in an aisle of the warehouse. The fork can be raised or lowered to any of the levels of a storage rack and can be extended into the rack to store and retrieve the product. The product can in some cases be as large as an automobile. Stacker cranes are often used in the large freezer warehouses of frozen food manufacturers. This automation avoids requiring forklift drivers to work in below-freezing temperatures every day.

Marine

[edit]Floating

[edit]

Floating cranes are used mainly in bridge building and port construction, but they are also used for occasional loading and unloading of especially heavy or awkward loads on and off ships. Some floating cranes are mounted on pontoons, others are specialized crane barges with a lifting capacity exceeding 10,000 short tons (8,929 long tons; 9,072 t) and have been used to transport entire bridge sections. Floating cranes have also been used to salvage sunken ships.

Crane vessels are often used in offshore construction. The largest revolving cranes can be found on SSCV Sleipnir, which has two cranes with a capacity of 10,000 tonnes (11,023 short tons; 9,842 long tons) each. For 50 years, the largest such crane was "Herman the German" at the Long Beach Naval Shipyard, one of three constructed by Nazi Germany and captured in the war. The crane was sold to the Panama Canal in 1996 where it is now known as Titan.[78]

Deck

[edit]

Deck cranes, also known as shipboard or cargo cranes,[79] are located on ships and boats, used for cargo operations where no shore unloading facilities are available, raising and lowering loads (such as shellfish dredges and fish nets) into the water, and small boat unloading and retrieval. Most are diesel-hydraulic or electric-hydraulic, supporting an increasingly automated control interface.[80]

Other types

[edit]Railroad

[edit]A railroad crane has flanged wheels for use on railroads. The simplest form is a crane mounted on a flatcar. More capable devices are purpose-built. Different types of crane are used for maintenance work, recovery operations and freight loading in goods yards and scrap handling facilities.

Aerial

[edit]

Aerial cranes or "sky cranes" usually are helicopters designed to lift large loads. Helicopters are able to travel to and lift in areas that are difficult to reach by conventional cranes. Helicopter cranes are most commonly used to lift loads onto shopping centers and high-rise buildings. They can lift anything within their lifting capacity, such as air conditioning units, cars, boats, swimming pools, etc. They also perform disaster relief after natural disasters for clean-up, and during wild-fires they are able to carry huge buckets of water to extinguish fires.

Some aerial cranes, mostly concepts, have also used lighter-than air aircraft, such as airships.

Efficiency increase of cranes

[edit]Lifetime of existing cranes made of welded metal structures can often be extended for many years by after treatment of welds. During development of cranes, load level (lifting load) can be significantly increased by taking into account the IIW recommendations, leading in most cases to an increase of the permissible lifting load and thus to an efficiency increase.[81]

Similar machines

[edit]

The generally accepted definition of a crane is a machine for lifting and moving heavy objects by means of ropes or cables suspended from a movable arm. As such, a lifting machine that does not use cables, or else provides only vertical and not horizontal movement, cannot strictly be called a 'crane'.

Types of crane-like lifting machine include:

More technically advanced types of such lifting machines are often known as "cranes", regardless of the official definition of the term.

Special examples

[edit]- Finnieston Crane, a.k.a. the Stobcross Crane

- Category A-listed example of a "hammerhead" (cantilever) crane in Glasgow's former docks, built by the William Arrol company.

- 50 m (164 ft) tall, 175 tonnes (172 long tons; 193 short tons) capacity, built 1926

- Taisun

- Kockums Crane

- shipyard crane formerly at Kockums, Sweden.

- 138 m (453 ft) tall, 1,500 tonnes (1,500 long tons; 1,700 short tons) capacity, since moved to Ulsan, South Korea

- Samson and Goliath (cranes)

- two gantry cranes at the Harland & Wolff shipyard in Belfast built by Krupp

- Goliath is 96 m (315 ft) tall, Samson is 106 m (348 ft)

- span 140 m (459 ft), lift-height 70 m (230 ft), capacity 840 tonnes (830 long tons; 930 short tons) each, 1,600 tonnes (1,600 long tons; 1,800 short tons) combined

- Breakwater Crane Railway

- self-propelled steam crane that formerly ran the length of the breakwater at Douglas.

- ran on 10 ft (3,048 mm) gauge track, the broadest in the British Isles

- Liebherr TCC 78000[82]

Crane operators

[edit]

Crane operators are skilled workers and heavy equipment operators.

Key skills that are needed for a crane operator include:

- An understanding of how to use and maintain machines and tools

- Good team working skills

- Attention to details

- Good spatial awareness.

- Patience and the ability to stay calm in stressful situations[83]

Terminology

[edit]This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (June 2023) |

The ISO 4306 series of specifications establish the vocabulary for cranes:[84]

- Part 1: General

- Part 2: Mobile cranes

- Part 3: Tower cranes

- Part 4: Jib cranes

- Part 5: Bridge and gantry cranes

See also

[edit]- Accredited Crane Operator Certification

- Banksman

- Cherry picker

- Davit

- Floating sheerleg

- Gantry crane

- Lifting devices with one, two, and three legs:

- Overhead crane

- Pallet

- Patient lift

- Sidelifter

- Steam shovel

- Taisun

- Telescopic handler

References

[edit]- ^ "How Are Cranes Powered?". Bryn Thomas Cranes. 22 February 2017. Retrieved 20 November 2017.

- ^ Pitt 1911, p. 368.

- ^ a b Paipetis, S. A.; Ceccarelli, Marco (2010). The Genius of Archimedes -- 23 Centuries of Influence on Mathematics, Science and Engineering: Proceedings of an International Conference held at Syracuse, Italy, June 8–10, 2010. Springer Science & Business Media. p. 416. ISBN 9789048190911.

- ^ a b Chondros, Thomas G. (1 November 2010). "Archimedes life works and machines". Mechanism and Machine Theory. 45 (11): 1766–1775. doi:10.1016/j.mechmachtheory.2010.05.009. ISSN 0094-114X.

- ^ a b Sayed, Osama Sayed Osman; Attalemanan, Abusamra Awad (19 October 2016). The Structural Performance of Tower Cranes Using Computer Program SAP2000-v18 (Thesis). Sudan University of Science and Technology. Archived from the original on 14 December 2019. Retrieved 1 August 2019.

The earliest recorded version or concept of a crane was called a Shaduf and used over 4,000 years by the Egyptians to transport water.

- ^ Faiella, Graham (2006). The Technology of Mesopotamia. The Rosen Publishing Group. p. 27. ISBN 9781404205604.

- ^ a b Coulton 1974, p. 7

- ^ a b Coulton 1974, pp. 14ff

- ^ a b Coulton 1974, p. 16

- ^ All data from: Dienel & Meighörner 1997, p. 13

- ^ Lancaster 1999, p. 426

- ^ Lancaster 1999, pp. 427ff

- ^ Lancaster 1999, pp. 434ff

- ^ Lancaster 1999, p. 436

- ^ a b c d Matheus 1996, p. 346

- ^ Matthies 1992, p. 514

- ^ a b Matthies 1992, p. 515

- ^ Matthies 1992, p. 526

- ^ a b c d e f Matheus 1996, p. 345

- ^ a b Matthies 1992, p. 524

- ^ Matthies 1992, p. 545

- ^ Matthies 1992, p. 518

- ^ Matthies 1992, pp. 525ff

- ^ Matthies 1992, p. 536

- ^ a b c Matthies 1992, p. 533

- ^ Matthies 1992, pp. 532ff

- ^ Matthies 1992, p. 535

- ^ a b Coulton 1974, p. 6

- ^ a b Dienel & Meighörner 1997, p. 17

- ^ Matthies 1992, p. 534

- ^ Matthies 1992, p. 531

- ^ Matthies 1992, p. 540

- ^ Matheus 1996, p. 347

- ^ These are Bergen, Stockholm, Karlskrona (Sweden), Kopenhagen (Denmark), Harwich (England), Gdańsk (Poland), Lüneburg, Stade, Otterndorf, Marktbreit, Würzburg, Östrich, Bingen, Andernach and Trier (Germany). Cf. Matheus 1996, p. 346

- ^ Britannica, The Editors of Encyclopaedia (1 May 2023). "shipyard". Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved 8 June 2023.

- ^ Threedecks: British sheer hulk 'Chatham' (1694)

- ^ Gardiner, Robert; Lavery, Brian, eds. (1992). The Line of Battle: The Sailing Warship 1650–1840. Conway Maritime Press. pp. 106–107. ISBN 0-85177-954-9.

- ^ Lancaster 1999, p. 428

- ^ Lancaster 1999, pp. 436–437

- ^ The Victorian Web

- ^ "Armstrong Hydraulic Crane". Machine-History.Com. Archived from the original on 10 January 2014.

- ^ a b Dougan, David (1970). The Great Gun-Maker: The Story of Lord Armstrong. Sandhill Press Ltd. ISBN 0-946098-23-9.

- ^ McKenzie, Peter (1983). W.G. Armstrong: The Life and Times of Sir William George Armstrong, Baron Armstrong of Cragside. Longhirst Press. ISBN 0-946978-00-X.

- ^ "Newcastle crane 'priceless' part of Venetian heritage". BBC. 20 May 2010. Retrieved 8 November 2013.

- ^ Brain, Marshall (April 2000). "How Tower Cranes Work". howstuffworks.com. Retrieved 2 April 2014.

- ^ a b c d e f g Standard for Certification 2.22 Lifting Appliances. Det Norske Veritas AS. October 2011.

- ^ Standard for certification No. 2.7-3 Portable offshore units. Det Norske Veritas. May 2011.

- ^ FEM 1.001 Rules for the design of hoisting appliances (3rd ed.). Federation Europeenne de la Manutention. October 1998.

- ^ 0027/ND Guidelines for Marine Lifting Operations. www.gl-nobledenton.com. 2010.

- ^ Boom Truck, constructionequipment.com

- ^ "What Is A HIAB? Is a HIAB A Lorry Loader?". Retrieved 24 January 2021.

- ^ "History | Sunfab". Archived from the original on 12 March 2016. Retrieved 6 April 2016.

- ^ "Zoomlion QAY2000 Completes Overload Tests Successfully". 17 December 2013. Retrieved 24 January 2021.

- ^ "What Can You Lift With A HIAB?". Retrieved 24 January 2021.

- ^ "Hiab Loader Cranes - Custom-made cranes for highest productivity". Archived from the original on 22 March 2013.

- ^ Khan, Inamullah (14 July 2017). "Top 12 Different Types of Cranes used in Construction Works". CivilGuides. Retrieved 3 January 2018.

- ^ "Zoomlion QAY 2000". YouTube. Archived from the original on 4 April 2020. Retrieved 1 June 2008.

- ^ "World NO. 1 – SANY XCMG XGC88000 Crawler Crane - Cranesy". 21 January 2013. Retrieved 24 January 2021.

- ^ "15 Types of Cranes used in Construction (SURPRISE List)". Define Civil. 21 September 2018. Retrieved 26 September 2018.

- ^ Alfonso, Jack (24 June 2024). "Freo Group: a 50-year journey in cranes and logistics". Cranes & Lifting.

- ^ "Crane Lifts Big Load." Popular Science, August 1948, p. 106.

- ^ "The Liebherr Group in the years 1949-1960". www.liebherr.com - Liebherr.

- ^ Peckyte, Akvile (14 July 2021). "Brief History of Liebherr: Pioneers in Cranes". Plant Planet. Retrieved 17 July 2025.

- ^ Kaveh, Ali; Vazirinia, Yasin (2018). "Optimization of tower crane location and material quantity between supply and demand points: A comparative study". Periodica Polytechnica Civil Engineering. 62 (3): 732–745. doi:10.3311/PPci.11816.

- ^ Institute of Party Wall Surveyors, Oversailing: what is it and why is it a concern for developers?, accessed on 12 October 2024

- ^ Cranes and Access https://s3.eu-central-1.amazonaws.com/vertikal.net/ca-2009-1-p25-32_0881f7cc.pdf

- ^ Elliott, Matthew (19 December 2015). "Tower crane anatomy". Crane & Rigging. Archived from the original on 22 December 2015. Retrieved 19 December 2015.

- ^ "the component of the tower cranes". 86towercrane.com. 21 April 2012. Archived from the original on 27 June 2012. Retrieved 15 August 2012.

- ^ Croucher, Martin (11 November 2009). "Myth of 'Babu Sassi' Remains After Burj Cranes Come Down". Khaleej Times. Archived from the original on 1 October 2012. Retrieved 3 June 2011.

- ^ Arnott, William (4 December 2019). "The real and hidden costs of tower crane anti-collision systems".

- ^ "How Tower Cranes Work". HowStuffWorks. 1 April 2000. Retrieved 23 August 2019.

- ^ Crane Building Itself on YouTube

- ^ SAS Tower Construction Simulation on YouTube

- ^ "Travel Lift". Archived from the original on 30 September 2019. Retrieved 1 October 2019. and other pages on this Web site.

- ^ Pitt 1911, p. 370.

- ^ "Navy's biggest crane is coming down". Retrieved 11 July 2024.

- ^ "The Cowes Giant Cantilever Crane". Freespace.virgin.net. Archived from the original on 28 August 2012. Retrieved 15 August 2012.

- ^ "Herman the German". 28 April 2011. Retrieved 27 April 2014.

- ^ "Cargo cranes". Wartsila.com. Retrieved 16 March 2024.

- ^ Cao, Yuchi; Li, Tieshan (1 May 2024). "Nonlinear antiswing control for shipboard boom cranes with full state constraints". Applied Ocean Research. 146 103964. Bibcode:2024AppOR.14603964C. doi:10.1016/j.apor.2024.103964. ISSN 0141-1187.

- ^ International Institute of Welding Technology, IIW, published the guideline "Recommendations for the HFMI Treatment" in 2016.

- ^ "TCC 78000 - Heavy Lift Handling in Rostock, Germany". Liebherr. Retrieved 26 April 2020.

- ^ Team, Go Construct. "Crane Operator Job Description, Salary & Training". Go Construct. Retrieved 26 August 2020.

- ^ Cranes. Vocabulary, BSI British Standards, doi:10.3403/30347964, retrieved 30 August 2024

Sources

[edit]History of cranes

- Coulton, J. J. (1974), "Lifting in Early Greek Architecture", The Journal of Hellenic Studies, 94: 1–19, doi:10.2307/630416, JSTOR 630416, S2CID 162973494

- Dienel, Hans-Liudger; Meighörner, Wolfgang (1997), "Der Tretradkran", Publication of the Deutsches Museum (Technikgeschichte Series) (2nd ed.), München

- Lancaster, Lynne (1999), "Building Trajan's Column", American Journal of Archaeology, 103 (3): 419–439, doi:10.2307/506969, JSTOR 506969, S2CID 192986322

- Matheus, Michael (1996), "Mittelalterliche Hafenkräne", in Lindgren, Uta (ed.), Europäische Technik im Mittelalter. 800 bis 1400. Tradition und Innovation (4th ed.), Berlin: Gebr. Mann Verlag, pp. 345–348, ISBN 3-7861-1748-9

- Matthies, Andrea (1992), "Medieval Treadwheels. Artists' Views of Building Construction", Technology and Culture, 33 (3): 510–547, doi:10.2307/3106635, JSTOR 3106635, S2CID 113201185

- O'Connor, Colin (1993), Roman Bridges, Cambridge University Press, pp. 47–51, ISBN 0-521-39326-4

- This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Pitt, Walter (1911). "Cranes". In Chisholm, Hugh (ed.). Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 7 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 368–372.