Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Samarkand

View on WikipediaKey Information

Samarkand[a] is a city in southeastern Uzbekistan and among the oldest continuously inhabited cities in Central Asia. Samarkand is the capital of the Samarkand Region and a district-level city, that includes the urban-type settlements Kimyogarlar, Farhod and Khishrav.[2] With 551,700 inhabitants (2021),[3] it is the third-largest city in Uzbekistan.

There is evidence of human activity in the area of the city dating from the late Paleolithic Era. Though there is no direct evidence of when Samarkand was founded, several theories propose that it was founded between the 8th and 7th centuries BC. Prospering from its location on the Silk Road between China, Persia and Europe, at times Samarkand was one of the largest[4] cities in Central Asia,[5] and was an important city of the empires of Greater Iran.[6] By the time of the Persian Achaemenid Empire, it was the capital of the Sogdian satrapy. The city was conquered by Alexander the Great in 329 BC, when it was known as Markanda, which was rendered in Greek as Μαράκανδα.[7] The city was ruled by a succession of Iranian and Turkic rulers until it was conquered by the Mongols under Genghis Khan in 1220.

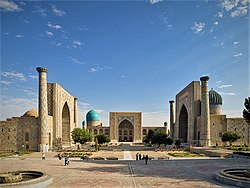

The city is noted as a centre of Islamic scholarly study and the birthplace of the Timurid Renaissance. In the 14th century, Timur made it the capital of his empire and the site of his mausoleum, the Gur-e Amir. The Bibi-Khanym Mosque, rebuilt during the Soviet era, remains one of the city's most notable landmarks. Samarkand's Registan square was the city's ancient centre and is bounded by three monumental religious buildings. The city has carefully preserved the traditions of ancient crafts: embroidery, goldwork, silk weaving, copper engraving, ceramics, wood carving, and wood painting.[8] In 2001, UNESCO added the city to its World Heritage List as Samarkand – Crossroads of Cultures.

Modern Samarkand is divided into two parts: the old city, which includes historical monuments, shops, and old private houses; and the new city, which was developed during the days of the Russian Empire and Soviet Union and includes administrative buildings along with cultural centres and educational institutions.[9] On 15 and 16 September 2022, the city hosted the 2022 SCO summit.

Samarkand has a multicultural and plurilingual history that was significantly modified by the process of national delimitation in Central Asia. Many inhabitants of the city are native or bilingual speakers of the Tajik language,[10][11] whereas Uzbek is the official language and Russian is also widely used in the public sphere, as per Uzbekistan's language policy.

Etymology

[edit]The name comes from the Iranian languages Persian and Sogdian samar "stone, rock" and kand "fort, town."[12] In this respect, Samarkand shares the same meaning as the name of the Uzbek capital Tashkent, with tash- being the Turkic term for "stone" and -kent the Turkic analogue of kand borrowed from Iranian languages.[13]

According to 11th-century scholar Mahmud al-Kashghari, the city was known in Karakhanid as Sämizkänd (سَمِزْکَنْدْ), meaning "fat city."[14] 16th-century Mughal emperor Babur also mentioned the city under this name, and 15th-century Castillian traveler Ruy González de Clavijo stated that Samarkand was simply a distorted form of it.[15]

History

[edit]This section needs additional citations for verification. (November 2022) |

Early history

[edit]Along with Bukhara,[16] Samarkand is one of the oldest inhabited cities in Central Asia, prospering from its location on the trade route between China and Europe. There is no direct evidence of when it was founded. Researchers at the Institute of Archaeology of Samarkand date the city's founding around 700 BC.[17]

Archaeological excavations conducted within the city limits (Syob and midtown) as well as suburban areas (Hojamazgil, Sazag'on) unearthed 40,000-year-old evidence of human activity, dating back to the Upper Paleolithic. A group of Mesolithic (12th–7th millennia BC) archaeological sites were discovered in the suburbs of Sazag'on-1, Zamichatosh, and Okhalik. The Syob and Darg'om canals, supplying the city and its suburbs with water, appeared around the 7th–5th centuries BC (early Iron Age).

From its earliest days, Samarkand was one of the main centres of Sogdian civilization. By the time of the Achaemenid dynasty of Persia, the city had become the capital of the Sogdian satrapy.

Hellenistic period

[edit]

Ferens Art Gallery, Hull.

Alexander the Great conquered Samarkand in 329 BC. The city was known as Maracanda (Μαράκανδα) by the Greeks.[18] Written sources offer small clues as to the subsequent system of government.[19] They mention one Orepius who became ruler "not from ancestors, but as a gift of Alexander."[20]

While Samarkand suffered significant damage during Alexander's initial conquest, the city recovered rapidly and flourished under the new Hellenic influence. There were also major new construction techniques. Oblong bricks were replaced with square ones and superior methods of masonry and plastering were introduced.[21]

Alexander's conquests introduced classical Greek culture into Central Asia and for a time, Greek aesthetics heavily influenced local artisans. This Hellenistic legacy continued as the city became part of various successor states in the centuries following Alexander's death, the Greek Seleucid Empire, Greco-Bactrian Kingdom, and Kushan Empire (even though the Kushana themselves originated in Central Asia). After the Kushan state lost control of Sogdia during the 3rd century AD, Samarkand went into decline as a centre of economic, cultural, and political power. It did not significantly revive until the 5th century.

Sasanian era

[edit]Samarkand was conquered by the Persian Sasanians c. 260 AD. Under Sasanian rule, the region became an essential site for Manichaeism and facilitated the dissemination of the religion throughout Central Asia.[22]

Hephthalites and Turkic Khaganate era

[edit]Between AD 350 and 375, Samarkand was conquered by the nomadic tribes of Xionites, the origin of which remains controversial.[23] The resettlement of nomadic groups to Samarkand confirms archaeological material from the 4th century. The culture of nomads from the Middle Syrdarya basin is spreading in the region.[24] Between 457 and 509, Samarkand was part of the Kidarite state.[25]

After the Hephthalites ("White Huns") conquered Samarkand, they controlled it until the Göktürks, in an alliance with the Sassanid Persians, won it at the Battle of Bukhara, c. 560 AD.[28]

In the middle of the 6th century, a Turkic state was formed in Altai, founded by the Ashina dynasty. The new state formation was named the Turkic Khaganate after the people of the Turks, which were headed by the ruler – the Khagan. From 557 to 561, the Hephthalites empire was defeated by the joint actions of the Turks and Sassanids, which led to the establishment of a common border between the two empires.[29]

In the early Middle Ages, Samarkand was surrounded by four rows of defensive walls and had four gates.[30]

An ancient Turkic burial with a horse was investigated on the territory of Samarkand. It dates back to the 6th century.[31]

During the period of the ruler of the Western Turkic Khaganate, Tong Yabghu Qaghan (618–630), family relations were established with the ruler of Samarkand – Tong Yabghu Qaghan gave him his daughter.[32]

Some parts of Samarkand have been Christian since the 4th century. In the 5th century, a Nestorian chair was established in Samarkand. At the beginning of the 8th century, it was transformed into a Nestorian metropolitanate.[33] Discussions and polemics arose between the Sogdian followers of Christianity and Manichaeism, reflected in the documents.[34]

Early Islamic era

[edit]

The armies of the Umayyad Caliphate under Qutayba ibn Muslim captured the city from the Tang dynasty c. 710 CE.[22] During this period, Samarkand was a diverse religious community and was home to a number of religions, including Zoroastrianism, Buddhism, Hinduism, Manichaeism, Judaism, and Nestorian Christianity, with most of the population following Zoroastrianism.[36]

Qutayba generally did not settle Arabs in Central Asia; he forced the local rulers to pay him tribute but largely left them to their own devices. Samarkand was the major exception to this policy: Qutayba established an Arab garrison and Arab governmental administration in the city, its Zoroastrian fire temples were razed, and a mosque was built.[37] Much of the city's population converted to Islam.[38]

As a long-term result, Samarkand developed into a center of Islamic and Arabic learning.[37] At the end of the 740s, a movement of those dissatisfied with the power of the Umayyads emerged in the Arab Caliphate, led by the Abbasid commander Abu Muslim, who, after the victory of the uprising, became the governor of Khorasan and Maverannahr (750–755). He chose Samarkand as his residence. His name is associated with the construction of a multi-kilometer defensive wall around the city and the palace.[39]

Legend has it that during Abbasid rule,[40] the secret of papermaking was obtained from two Chinese prisoners from the Battle of Talas in 751, which led to the foundation of the first paper mill in the Islamic world at Samarkand. The invention then spread to the rest of the Islamic world and thence to Europe.[citation needed]

Abbasid control of Samarkand soon dissipated and was replaced with that of the Samanids (875–999), though the Samanids were still nominal vassals of the Caliph during their control of Samarkand. Under Samanid rule the city became a capital of the Samanid dynasty and an even more important node of numerous trade routes. The Samanids were overthrown by the Karakhanids around 999. Over the next 200 years, Samarkand would be ruled by a succession of Turkic tribes, including the Seljuqs and the Khwarazmshahs.[41]

The 10th-century Persian author Istakhri, who travelled in Transoxiana, provides a vivid description of the natural riches of the region he calls "Smarkandian Sogd":

I know no place in it or in Samarkand itself where if one ascends some elevated ground one does not see greenery and a pleasant place, and nowhere near it are mountains lacking in trees or a dusty steppe... Samakandian Sogd... [extends] eight days travel through unbroken greenery and gardens... . The greenery of the trees and sown land extends along both sides of the river [Sogd]... and beyond these fields is pasture for flocks. Every town and settlement has a fortress... It is the most fruitful of all the countries of Allah; in it are the best trees and fruits, in every home are gardens, cisterns and flowing water.

Karakhanid (Ilek-Khanid) period (11th–12th centuries)

[edit]

After the fall of the Samanids state in 999, it was replaced by the Qarakhanid State, where the Turkic Qarakhanid dynasty ruled.[42] After the state of the Qarakhanids split into two parts, Samarkand became a part of the West Karakhanid Khaganate and from 1040 to 1212 was its capital.[42] The founder of the Western Qarakhanid Khaganate was Ibrahim Tamgach Khan (1040–1068).[42] For the first time, he built a madrasah in Samarkand with state funds and supported the development of culture in the region. During his reign, a public hospital (bemoristan) and a madrasah were established in Samarkand, where medicine was also taught.

The memorial complex Shah-i-Zinda was founded by the rulers of the Karakhanid dynasty in the 11th century.[43]

The most striking monument of the Qarakhanid era in Samarkand was the palace of Ibrahim ibn Hussein (1178–1202), which was built in the citadel in the 12th century. During the excavations, fragments of monumental painting were discovered. On the eastern wall, a Turkic warrior was depicted, dressed in a yellow caftan and holding a bow. Horses, hunting dogs, birds and periodlike women were also depicted here.[44]

Mongol period

[edit]

The Mongols conquered Samarkand in 1220. Juvayni writes that Genghis killed all who took refuge in the citadel and the mosque, pillaged the city completely, and conscripted 30,000 young men along with 30,000 craftsmen. Samarkand suffered at least one other Mongol sack by Khan Baraq to get treasure he needed to pay an army. It remained part of the Chagatai Khanate (one of four Mongol successor realms) until 1370.

The Travels of Marco Polo, where Polo records his journey along the Silk Road in the late 13th century, describes Samarkand as "a very large and splendid city..."[45]

The Yenisei area had a community of weavers of Chinese origin, and Samarkand and Outer Mongolia both had artisans of Chinese origin, as reported by Changchun.[46] After Genghis Khan conquered Central Asia, foreigners were chosen as governmental administrators; Chinese and Qara-Khitays (Khitans) were appointed as co-managers of gardens and fields in Samarkand, which Muslims were not permitted to manage on their own.[47][48] The khanate allowed the establishment of Christian bishoprics (see below).

Timur's rule (1370–1405)

[edit]

Ibn Battuta, who visited in 1333, called Samarkand "one of the greatest and finest of cities, and most perfect of them in beauty." He also noted that the orchards were supplied water via norias.[49]

In 1365, a revolt against Chagatai Mongol control occurred in Samarkand.[50] In 1370, the conqueror Timur (Tamerlane), the founder and ruler of the Timurid Empire, made Samarkand his capital. Timur used various tools for legitimisation, including urban planning in his capital, Samarkand.[51] Over the next 35 years, he rebuilt most of the city and populated it with great artisans and craftsmen from across the empire. Timur gained a reputation as a patron of the arts, and Samarkand grew to become the centre of the region of Transoxiana. Timur's commitment to the arts is evident in how, in contrast with the ruthlessness he showed his enemies, he demonstrated mercy toward those with special artistic abilities. The lives of artists, craftsmen, and architects were spared so that they could improve and beautify Timur's capital.[citation needed]

Timur was also directly involved in construction projects, and his visions often exceeded the technical abilities of his workers. The city was in a state of constant construction, and Timur would often order buildings to be done and redone quickly if he was unsatisfied with the results.[52] By his orders, Samarkand could be reached only by roads; deep ditches were dug, and walls 8 km (5 mi) in circumference separated the city from its surrounding neighbors.[53] At this time, the city had a population of about 150,000.[54]

Henry III of Castile's ambassador Ruy Gonzalez de Clavijo, who visited Samarkand between 8 September and 20 November 1404, attested to the never-ending construction that went on in the city. "The Mosque which Timur had built seemed to us the noblest of all those we visited in the city of Samarkand."[55]

Ulugh Beg's period (1409–1449)

[edit]

Between 1417 and 1420, Timur's grandson Ulugh Beg built a madrasah in Samarkand, which became the first building in the architectural ensemble of Registan. Ulugh Beg invited a large number of astronomers and mathematicians of the Islamic world to this madrasah. Under Ulugh Beg, Samarkand became one of the world centers of medieval science. In the first half of the 15th century, a whole scientific school arose around Ulugh Beg, uniting prominent astronomers and mathematicians including Jamshid al-Kashi, Qāḍī Zāda al-Rūmī, and Ali Qushji. Ulugh Beg's main interest in science was astronomy, and he constructed an observatory in 1428. Its main instrument was the wall quadrant, which was unique in the world.[56] It was known as the "Fakhri Sextant" and had a radius of 40 meters.[57] Seen in the image on the left, the arc was finely constructed with a staircase on either side to provide access for the assistants who performed the measurements.

16th–18th centuries

[edit]In 1500, nomadic Uzbek warriors took control of Samarkand.[54] The Shaybanids emerged as the city's leaders at or about this time. In 1501, Samarkand was finally taken by Muhammad Shaybani from the Uzbek dynasty of Shaybanids, and the city became part of the newly formed “Bukhara Khanate”. Samarkand was chosen as the capital of this state, in which Muhammad Shaybani Khan was crowned. In Samarkand, Muhammad Shaybani Khan ordered to build a large madrasah, where he later took part in scientific and religious disputes. The first dated news about the Shaybani Khan madrasah dates back to 1504 (it was completely destroyed during the years of Soviet power). Muhammad Salikh wrote that Sheibani Khan built a madrasah in Samarkand to perpetuate the memory of his brother Mahmud Sultan.[58]

Fazlallah ibn Ruzbihan [who?] in "Mikhmon-namei Bukhara" expresses his admiration for the majestic building of the madrasah, its gilded roof, high hujras, spacious courtyard and quotes a verse praising the madrasah.[59] Zayn ad-din Vasifi, who visited the Sheibani-khan madrasah several years later, wrote in his memoirs that the veranda, hall and courtyard of the madrassah are spacious and magnificent.[58]

Abdulatif Khan, the son of Mirzo Ulugbek's grandson Kuchkunji Khan, who ruled in Samarkand from 1540 to 1551, was considered an expert in the history of Maverannahr and the Shibanid dynasty. He patronized poets and scientists. Abdulatif Khan himself wrote poetry under the literary pseudonym Khush.[60]

During the reign of the Ashtarkhanid Imam Quli Khan (1611–1642) famous architectural masterpieces were built in Samarkand. In 1612–1656, the governor of Samarkand, Yalangtush Bahadur, built a cathedral mosque, Tillya-Kari madrasah and Sherdor madrasah.[citation needed]

Zarafshan Water Bridge is a brick bridge built on the left bank of the Zarafshan River, 7–8 km northeast of the center of Samarkand, built by Shaibani Khan at the beginning of the 16th century.[61][62]

After an assault by the Afshar Shahanshah Nader Shah, the city was abandoned in the early 1720s.[63] From 1599 to 1756, Samarkand was ruled by the Ashtrakhanid branch of the Khanate of Bukhara.

-

Ulugh Beg Madrasah

-

Sher-Dor Madrasah

-

Tilya Kori Madrasah

-

Ulugh Beg Madrasah courtyard

-

Tiger on the Sher-Dor Madrasah iwan

Second half of the 18th–19th centuries

[edit]

From 1756 to 1868, it was ruled by the Manghud Emirs of Bukhara.[64] The revival of the city began during the reign of the founder of the Uzbek dynasty, the Mangyts, Muhammad Rakhim (1756–1758), who became famous for his strong-willed qualities and military art. Muhammad Rakhimbiy made some attempts to revive Samarkand.[65]

Russian Empire period

[edit]

The city came under imperial Russian rule after the citadel had been taken by a force under Colonel Konstantin Petrovich von Kaufman in 1868. Shortly thereafter the small Russian garrison of 500 men were themselves besieged. The assault, which was led by Abdul Malik Tura, the rebellious elder son of the Bukharan Emir, as well as Baba Beg of Shahrisabz and Jura Beg of Kitab, was repelled with heavy losses. General Alexander Konstantinovich Abramov became the first Governor of the Military Okrug, which the Russians established along the course of the Zeravshan River with Samarkand as the administrative centre. The Russian section of the city was built after this point, largely west of the old city.

In 1886, the city became the capital of the newly formed Samarkand Oblast of Russian Turkestan and regained even more importance when the Trans-Caspian railway reached it in 1888.

Soviet period

[edit]

Samarkand was the capital of the Uzbek SSR from 1925 to 1930, before being replaced by Tashkent. During World War II, after Nazi Germany invaded the Soviet Union, a number of Samarkand's citizens were sent to Smolensk to fight the enemy. Many were taken captive or killed by the Nazis.[66][67] Additionally, thousands of refugees from the occupied western regions of the USSR fled to the city, and it served as one of the main hubs for the fleeing civilians in the Uzbek Soviet Socialist Republic and the Soviet Union as a whole.[citation needed]

European study of the history of Samarkand began after the conquest of Samarkand by the Russian Empire in 1868. The first studies of the history of Samarkand belong to N. Veselovsky, V. Bartold and V. Vyatkin. In the Soviet period, the generalization of materials on the history of Samarkand was reflected in the two-volume History of Samarkand edited by the academician of Uzbekistan Ibrohim Moʻminov.[68]

On the initiative of Academician of the Academy of Sciences of the Uzbek SSR I. Muminov and with the support of Sharaf Rashidov, the 2500th anniversary of Samarkand was widely celebrated in 1970. In this regard, a monument to Ulugh Beg was opened, the Museum of the History of Samarkand was founded, and a two-volume history of Samarkand was prepared and published.[69][70]

After Uzbekistan gained independence, several monographs were published on the ancient and medieval history of Samarkand.[71][72]

Geography

[edit]

Samarkand is located in southeastern Uzbekistan, in the Zarefshan River valley, 135 km from Qarshi. Road M37 connects Samarkand to Bukhara, 240 km away. Road M39 connects it to Tashkent, 270 km away. The Tajikistan border is about 35 km from Samarkand; the Tajik capital Dushanbe is 210 km away from Samarkand. Road M39 connects Samarkand to Mazar-i-Sharif in Afghanistan, which is 340 km away.

Climate

[edit]Samarkand has a cold semi-arid climate (Köppen climate classification: BSk) with hot, dry summers and relatively wet, variable winters that alternate periods of warm weather with periods of cold weather. July and August are the hottest months of the year, with temperatures reaching and exceeding 40 °C (104 °F). Precipitation is sparse from June through October, but increases to a maximum from February to April. January 2008 was particularly cold; the temperature dropped to −22 °C (−8 °F).[74]

| Climate data for Samarkand (1991–2020, extremes 1891–present) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 23.2 (73.8) |

26.7 (80.1) |

32.2 (90.0) |

36.2 (97.2) |

39.5 (103.1) |

41.6 (106.9) |

42.4 (108.3) |

41.0 (105.8) |

38.6 (101.5) |

35.2 (95.4) |

31.5 (88.7) |

27.5 (81.5) |

42.4 (108.3) |

| Mean daily maximum °C (°F) | 7.3 (45.1) |

9.5 (49.1) |

15.2 (59.4) |

21.4 (70.5) |

27.0 (80.6) |

32.4 (90.3) |

34.5 (94.1) |

33.3 (91.9) |

28.6 (83.5) |

22.0 (71.6) |

14.4 (57.9) |

9.1 (48.4) |

21.2 (70.2) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | 2.3 (36.1) |

4.0 (39.2) |

9.3 (48.7) |

15.2 (59.4) |

20.4 (68.7) |

25.4 (77.7) |

27.2 (81.0) |

25.6 (78.1) |

20.6 (69.1) |

14.1 (57.4) |

8.0 (46.4) |

3.7 (38.7) |

14.7 (58.4) |

| Mean daily minimum °C (°F) | −1.3 (29.7) |

−0.2 (31.6) |

4.6 (40.3) |

9.7 (49.5) |

14.1 (57.4) |

18.0 (64.4) |

19.5 (67.1) |

17.9 (64.2) |

13.5 (56.3) |

7.8 (46.0) |

3.2 (37.8) |

−0.2 (31.6) |

8.9 (48.0) |

| Record low °C (°F) | −25.4 (−13.7) |

−22 (−8) |

−14.9 (5.2) |

−6.8 (19.8) |

−1.3 (29.7) |

4.8 (40.6) |

8.6 (47.5) |

7.8 (46.0) |

0.0 (32.0) |

−6.4 (20.5) |

−18.1 (−0.6) |

−22.8 (−9.0) |

−25.4 (−13.7) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 41.1 (1.62) |

52.2 (2.06) |

73.2 (2.88) |

62.9 (2.48) |

40.0 (1.57) |

6.8 (0.27) |

1.6 (0.06) |

1.6 (0.06) |

2.7 (0.11) |

16.0 (0.63) |

40.3 (1.59) |

39.2 (1.54) |

377.6 (14.87) |

| Average rainy days | 8 | 10 | 13 | 11 | 9 | 3 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 6 | 8 | 9 | 82 |

| Average snowy days | 9 | 7 | 3 | 0.3 | 0.1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.3 | 2 | 6 | 28 |

| Average relative humidity (%) | 76 | 74 | 70 | 63 | 54 | 42 | 42 | 43 | 47 | 59 | 68 | 74 | 59 |

| Average dew point °C (°F) | −2 (28) |

−1 (30) |

2 (36) |

6 (43) |

9 (48) |

9 (48) |

10 (50) |

9 (48) |

6 (43) |

4 (39) |

2 (36) |

−1 (30) |

4 (40) |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 119.2 | 130.9 | 172.2 | 228.8 | 297.7 | 345.5 | 373.1 | 358.9 | 305.9 | 242.6 | 150.7 | 120.2 | 2,845.7 |

| Average ultraviolet index | 2 | 3 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 4 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 4 |

| Source 1: Pogoda.ru.net [75] | |||||||||||||

| Source 2: Weather Atlas (UV),[76] Time and Date (dewpoints, 1985–2015),[77] NOAA[78] | |||||||||||||

People

[edit]According to official reports, a majority of Samarkand's inhabitants are Uzbeks, while many sources refer to the city as majority Tajik,[79][80][81][82] up to 70 percent of the city's population.[83] Tajiks are especially concentrated in the eastern part of the city, where the main architectural landmarks are.

According to various independent sources, Tajiks are Samarkand's majority ethnic group. Ethnic Uzbeks are the second-largest group[84] and are most concentrated in the west of Samarkand. Exact demographic figures are difficult to obtain since some people in Uzbekistan identify as "Uzbek" even though they speak Tajiki as their first language, often because they are registered as Uzbeks by the central government despite their Tajiki language and identity. As explained by Paul Bergne:

During the census of 1926 a significant part of the Tajik population was registered as Uzbek. Thus, for example, in the 1920 census in Samarkand city the Tajiks were recorded as numbering 44,758 and the Uzbeks only 3301. According to the 1926 census, the number of Uzbeks was recorded as 43,364 and the Tajiks as only 10,716. In a series of kishlaks [villages] in the Khojand Okrug, whose population was registered as Tajik in 1920 e.g. in Asht, Kalacha, Akjar i Tajik and others, in the 1926 census they were registered as Uzbeks. Similar facts can be adduced also with regard to Ferghana, Samarkand, and especially the Bukhara oblasts.[84]

Samarkand is also home to large ethnic communities of "Iranis" (the old, Persian-speaking, Shia population of Merv city and oasis, deported en masse to this area in the late 18th century), Russians, Ukrainians, Belarusians, Armenians, Azeris, Tatars, Koreans, Poles, and Germans, all of whom live primarily in the centre and western neighborhoods of the city. These peoples have emigrated to Samarkand since the end of the 19th century, especially during the Soviet Era; by and large, they speak the Russian language.

In the extreme west and southwest of Samarkand is a population of Central Asian Arabs, who mostly speak Uzbek; only a small portion of the older generation speaks Central Asian Arabic. In eastern Samarkand there was once a large mahallah of Bukharian (Central Asian) Jews, but starting in the 1970s, hundreds of thousands of Jews left Uzbekistan for Israel, United States, Canada, Australia, and Europe. Only a few Jewish families are left in Samarkand today.

Also in the eastern part of Samarkand there are several quarters where Central Asian "Gypsies"[85] (Lyuli, Djugi, Parya, and other groups) live. These peoples began to arrive in Samarkand several centuries ago from what are now India and Pakistan. They mainly speak a dialect of the Tajik language, as well as their own languages, most notably Parya.

Language

[edit]

The state and official language in Samarkand, as in all Uzbekistan, is the Uzbek language. Uzbek is one of the Turkic languages and the mother tongue of Uzbeks, Turkmens, Samarkandian Iranians, and most Samarkandian Arabs living in Samarkand.

As in the rest of Uzbekistan, the Russian language is the de facto second official language in Samarkand, and about 5% of signs and inscriptions in Samarkand are in this language. Russians, Belarusians, Poles, Germans, Koreans, the majority of Ukrainians, the majority of Armenians, Greeks, some Tatars, and some Azerbaijanis in Samarkand speak Russian. Several Russian-language newspapers are published in Samarkand, the most popular of which is Samarkandskiy vestnik (Russian: Самаркандский вестник, lit. the Samarkand Herald). The Samarkandian TV channel STV conducts some broadcasts in Russian.

De facto, the most common native language in Samarkand is Tajik, which is a dialect or variant of the Persian language. Samarkand was one of the cities in which the Persian language developed. Many classical Persian poets and writers lived in or visited Samarkand over the millennia, the most famous being Abulqasem Ferdowsi, Omar Khayyam, Abdurahman Jami, Abu Abdullah Rudaki, Suzani Samarqandi, and Kamal Khujandi.

While the official stance is that Uzbek is the most common language in Samarkand, some data indicate that only about 30% of residents speak it as a native tongue. For the other 70%, Tajik is the native tongue, with Uzbek the second language and Russian the third. However, as no population census has been taken in Uzbekistan since 1989, there are no accurate data on this matter. Despite Tajik being the second most common language in Samarkand, it does not enjoy the status of an official or regional language.[86][80][81][87][82][88] Nevertheless, at Samarkand State University ten faculties offer courses in Tajiki, and the Tajik Language and Literature Department has an enrolment of over 170 students.[89] Only one newspaper in Samarkand is published in Tajiki, in the Cyrillic Tajik alphabet: Ovozi Samarqand (Tajik: Овози Самарқанд —Voice of Samarkand). Local Samarkandian STV and "Samarkand" TV channels offer some broadcasts in Tajik, as does one regional radio station. In 2022 a quarterly literary magazine in Tajiki, Durdonai Sharq, was launched in Samarkand.[89]

In addition to Uzbek, Tajik, and Russian, native languages spoken in Samarkand include Ukrainian, Armenian, Azerbaijani, Tatar, Crimean Tatar, Arabic (for a very small percentage of Samarkandian Arabs), and others.

Modern Samarkand is a vibrant city, and in 2019 the city hosted the first Samarkand Half Marathon.[90] In 2022 this also included a full marathon for the first time.

Religion

[edit]Islam

[edit]Islam entered Samarkand in the 8th century, during the invasion of the Arabs in Central Asia (Umayyad Caliphate). Before that, almost all inhabitants of Samarkand were Zoroastrians, and many Nestorians and Buddhists also lived in the city. From that point forward, throughout the reigns of many Muslim governing powers, numerous mosques, madrasahs, minarets, shrines, and mausoleums were built in the city. Many have been preserved. For example, there is the Shrine of Imam Bukhari, an Islamic scholar who authored the hadith collection known as Sahih al-Bukhari, which Sunni Muslims regard as one of the most authentic (sahih) hadith collections. His other books included Al-Adab al-Mufrad. Samarkand is also home to the Shrine of Imam Maturidi, the founder of Maturidism and the Mausoleum of the Prophet Daniel, who is revered in Islam, Judaism, and Christianity.

Most inhabitants of Samarkand are Muslim, primarily Sunni (mostly Hanafi) and Sufi. Approximately 80–85% of Muslims in the city are Sunni, comprising almost all Tajiks, Uzbeks, and Samarkandian Arabs living therein. Samarkand's best-known Islamic sacred lineages are the descendants of Sufi leaders such as Khodja Akhror Wali (1404–1490) and Makhdumi A’zam (1461–1542), the descendants of Sayyid Ata (first half of 14th c.) and Mirakoni Khojas (Sayyids from Mirakon, a village in Iran).[91] The liberal policy of President Shavkat Mirziyoyev opened up new opportunities for the expression of the religious identity. In Samarkand, since 2018, there has been an increase in the number of women wearing the hijab.[92]

Shia Muslims

[edit]The Samarqand Vilayat is one of the two regions of Uzbekistan (along with Bukhara Vilayat) that are home to a large number of Shiites. The total population of the Samarkand Vilayat is more than 3,720,000 people (2019).

There are no exact data on the number of Shiites in the city of Samarkand, but the city has several Shiite mosques and madrasas. The largest of these are the Punjabi Mosque, the Punjabi Madrassah, and the Mausoleum of Mourad Avliya. Every year, the Shiites of Samarkand celebrate Ashura, as well as other memorable Shiite dates and holidays.

Shiites in Samarkand are mostly Samarkandian Iranians, who call themselves Irani. Their ancestors began to arrive in Samarkand in the 18th century. Some migrated there in search of a better life, others were sold as slaves there by Turkmen captors, and others were soldiers who were posted to Samarkand. Mostly they came from Khorasan, Mashhad, Sabzevar, Nishapur, and Merv; and secondarily from Iranian Azerbaijan, Zanjan, Tabriz, and Ardabil. Samarkandian Shiites also include Azerbaijanis, as well as small numbers of Tajiks and Uzbeks.

While there are no official data on the total number of Shiites in Uzbekistan, they are estimated to be "several hundred thousand." According to leaked diplomatic cables, in 2007–2008, the US Ambassador for International Religious Freedom held a series of meetings with Sunni mullahs and Shiite imams in Uzbekistan. During one of the talks, the imam of the Shiite mosque in Bukhara said that about 300,000 Shiites live in the Bukhara Vilayat and 1 million in the Samarkand Vilayat. The Ambassador slightly doubted the authenticity of these figures, emphasizing in his report that data on the numbers of religious and ethnic minorities provided by the government of Uzbekistan were considered a very "delicate topic" due to their potential to provoke interethnic and interreligious conflicts. All the ambassadors of the ambassador tried to emphasize that traditional Islam, especially Sufism and Sunnism, in the regions of Bukhara and Samarkand is characterized by great religious tolerance toward other religions and sects, including Shiism.[93][94][95]

Christianity

[edit]This section needs additional citations for verification. (March 2024) |

Christianity was introduced to Samarkand when it was part of Sogdiana, long before the penetration of Islam into Central Asia. The city then became one of the centers of Nestorianism in Central Asia.[96] The majority of the population were then Zoroastrians, but since Samarkand was the crossroads of trade routes among China, Persia, and Europe, it was religiously tolerant. Under the Umayyad Caliphate, Zoroastrians and Nestorians were persecuted by the Arab conquerors;[citation needed] the survivors fled to other places or converted to Islam. Several Nestorian temples were built in Samarkand, but they have not survived. Their remains were found by archeologists at the ancient site of Afrasiyab and on the outskirts of Samarkand.

In the three decades of 1329–1359, the Samarkand eparchy of the Roman Catholic Church served several thousand Catholics who lived in the city. According to Marco Polo and Johann Elemosina, a descendant of Chaghatai Khan, the founder of the Chaghatai dynasty, Eljigidey, converted to Christianity and was baptized. With the assistance of Eljigidey, the Catholic Church of St. John the Baptist was built in Samarkand. After a while, however, Islam completely supplanted Catholicism.

Christianity reappeared in Samarkand several centuries later, from the mid-19th century onward, after the city was seized by the Russian Empire. Russian Orthodoxy was introduced to Samarkand in 1868, and several churches and temples were built. In the early 20th century several more Orthodox cathedrals, churches, and temples were built, most of which were demolished while Samarkand was part of the USSR.

In present time, Christianity is the second-largest religious group in Samarkand with the predominant form is the Russian Orthodox Church (Moscow Patriarchate). More than 5% of Samarkand residents are Orthodox, mostly Russians, Ukrainians, and Belarusians, and also some Koreans and Greeks. Samarkand is the center of the Samarkand branch (which includes the Samarkand, Qashqadarya, and Surkhandarya provinces of Uzbekistan) of the Uzbekistan and Tashkent eparchy of the Central Asian Metropolitan District of the Russian Orthodox Church of the Moscow Patriarchate. The city has several active Orthodox churches: Cathedral of St. Alexiy Moscowskiy, Church of the Intercession of the Holy Virgin, and Church of St. George the Victorious. There are also a number of inactive Orthodox churches and temples, for example that of Church of St. George Pobedonosets.[97][98]

There are also a few tens of thousands of Catholics in Samarkand, mostly Poles, Germans, and some Ukrainians. In the center of Samarkand is St. John the Baptist Catholic Church, which was built at the beginning of the 20th century. Samarkand is part of the Apostolic Administration of Uzbekistan.[99]

The third largest Christian sect in Samarkand is the Armenian Apostolic Church, followed by a few tens of thousands of Armenian Samarkandians. Armenian Christians began emigrating to Samarkand at the end of the 19th century, this flow increasing especially in the Soviet era.[100] In the west of Samarkand is the Armenian Church Surb Astvatsatsin.[101]

Samarkand also has several thousand Protestants, including Lutherans, Baptists, Mormons, Jehovah's Witnesses, Adventists, and members of the Korean Presbyterian church. These Christian movements appeared in Samarkand mainly after the independence of Uzbekistan in 1991.[102]

Landmarks

[edit]Silk Road Samarkand (Eternal city)

[edit]Silk Road Samarkand is a modern multiplex which opened in early 2022 in eastern Samarkand. The complex covers 260 hectares and includes world-class business and medical hotels, eateries, recreational facilities, park grounds, an ethnographic corner and a large congress hall for hosting international events.[103]

Eternal city situated in Silk Road Samarkand complex. This site which occupies 17 hectares accurately recreates the spirit of the ancient city backed up by the history and traditions of Uzbek lands and Uzbek people for the guests of the Silk Road Samarkand. The narrow streets here house multiple shops of artists, artisans, and craftsmen. The pavilions of the Eternal City were inspired by real houses and picturesque squares described in ancient books. This is where you can plunge into a beautiful oriental fairy tale: with turquoise domes, mosaics on palaces, and high minarets that pierce the sky.

Visitors to the Eternal City can taste national dishes from different eras and regions of the country and also see authentic street performances. The Eternal City showcases a unique mix of Parthian, Hellenistic, and Islamic cultures so that the guests could imagine the versatile heritage of bygone centuries in full splendor. The project was inspired and designed by Bobur Ismoilov, a famous modern artist.[104]

Architecture

[edit]

Timur initiated the building of Bibi-Khanym after his 1398–1399 campaign in India. The Bibi-Khanym originally had about 450 marble columns, which were hauled there and set up with the help of 95 elephants that Timur had brought back from Hindustan. Artisans and stonemasons from India designed the mosque's dome, giving it its distinctive appearance amongst the other buildings. An 1897 earthquake destroyed the columns, which were not entirely restored in the subsequent reconstruction.[52]

The best-known landmark of Samarkand is the mausoleum known as Gur-i Amir. It exhibits the influences of many cultures, past civilizations, neighboring peoples, and religions, especially those of Islam. Despite the devastation wrought by Mongols to Samarkand's pre-Timurid Islamic architecture, under Timur these architectural styles were revived, recreated, and restored. The blueprint and layout of the mosque itself, with their precise measurements, demonstrate the Islamic passion for geometry. The entrance to the Gur-i Amir is decorated with Arabic calligraphy and inscriptions, the latter a common feature in Islamic architecture. Timur's meticulous attention to detail is especially obvious inside the mausoleum: the tiled walls are a marvelous example of mosaic faience, an Iranian technique in which each tile is cut, colored, and fit into place individually.[52] The tiles of the Gur-i Amir were also arranged so that they spell out religious words such as "Muhammad" and "Allah."[52]

The ornamentation of the Gur-i Amir's walls includes floral and vegetal motifs, which signify gardens; the floor tiles feature uninterrupted floral patterns. In Islam, gardens are symbols of paradise, and as such, they were depicted on the walls of tombs and grown in Samarkand itself.[52] Samarkand boasted two major gardens, the New Garden and the Garden of Heart's Delight, which became the central areas of entertainment for ambassadors and important guests. In 1218, a friend of Genghis Khan named Yelü Chucai reported that Samarkand was the most beautiful city of all, as "it was surrounded by numerous gardens. Every household had a garden, and all the gardens were well designed, with canals and water fountains that supplied water to round or square-shaped ponds. The landscape included rows of willows and cypress trees, and peach and plum orchards were shoulder to shoulder."[105] Persian carpets with floral patterns have also been found in some Timurid buildings.[106]

The elements of traditional Islamic architecture can be seen in traditional mud-brick Uzbek houses that are built around central courtyards with gardens.[107] Most of these houses have painted wooden ceilings and walls. By contrast, houses in the west of the city are chiefly European-style homes built in the 19th and 20th centuries.[107]

Turko-Mongol influence is also apparent in Samarkand's architecture. It is believed that the melon-shaped domes of the mausoleums were designed to echo yurts or gers, traditional Mongol tents in which the bodies of the dead were displayed before burial or other disposition. Timur built his tents from more-durable materials, such as bricks and wood, but their purposes remained largely unchanged.[52] The chamber in which Timur's own body was laid included "tugs", poles whose tops were hung with a circular arrangement of horse or yak tail hairs. These banners symbolized an ancient Turkic tradition of sacrificing horses, which were valuable commodities, to honor the dead.[52] Tugs were also a type of cavalry standard used by many nomads, up to the time of the Ottoman Turks.

Colors of buildings in Samarkand also have significant meanings. The dominant architectural color is blue, which Timur used to convey a broad range of concepts. For example, the shades of blue in the Gur-i Amir are colors of mourning; in that era, blue was the color of mourning in Central Asia, as it still is in various cultures today. Blue was also considered the color that could ward off "the evil eye" in Central Asia; this notion is evidenced by in the number of blue-painted doors in and around the city. Furthermore, blue represented water, a particularly rare resource in the Middle East and Central Asia; walls painted blue symbolized the wealth of the city.

Gold also has a strong presence in the city. Timur's fascination with vaulting explains the excessive use of gold in the Gur-i Amir, as well as the use of embroidered gold fabric in both the city and his buildings. The Mongols had great interests in Chinese- and Persian-style golden silk textiles, as well as nasij[108] woven in Iran and Transoxiana. Mongol leaders like Ögedei Khan built textile workshops in their cities to be able to produce gold fabrics themselves.

Suburbs

[edit]Suburbs of the city include: Gulyakandoz, Superfosfatnyy, Bukharishlak, Ulugbek, Ravanak, Kattakishlak, Registan, Zebiniso, Kaftarkhona, Uzbankinty.[109]

Transport

[edit]Local

[edit]Samarkand has a strong public-transport system. From Soviet times up through today, municipal buses and taxis (GAZ-21, GAZ-24, GAZ-3102, VAZ-2101, VAZ-2106 and VAZ-2107) have operated in Samarkand. Buses, mostly SamAuto and Isuzu buses, are the most common and popular mode of transport in the city. Taxis, which are mostly Chevrolets and Daewoo sedans, are usually yellow in color. Since 2017, there have also been several Samarkandian tram lines, mostly Vario LF.S Czech trams. From the Soviet Era up until 2005, Samarkandians also got around via trolleybus. Finally, Samarkand has the so-called "Marshrutka," which are Daewoo Damas and GAZelle minibuses.

-

Many yellow taxis on the streets of Samarkand

-

Taxi and tram on Rudaki Street in Samarkand

-

Tram in Samarkand

Until 1950, the main forms of transport in Samarkand were carriages and "arabas" with horses and donkeys. However, the city had a steam tram from 1924 to 1930, and there were more modern trams from 1947 to 1973.

Air transport

[edit]In the north of the city is Samarkand International Airport, which was opened in the 1930s, under the Soviets. As of spring 2019, Samarkand International Airport has flights to Tashkent, Nukus, Moscow, Saint Petersburg, Yekaterinburg, Kazan, Istanbul, and Dushanbe; charter flights to other cities are also available.

Railway

[edit]Modern Samarkand is an important rail junction of Uzbekistan, and all national east–west railway routes pass through the city. The most important and longest of these is Tashkent–Kungrad. High-speed Tashkent–Samarkand high-speed rail line trains run between Tashkent, Samarkand, and Bukhara. Samarkand also has international railway connections: Saratov–Samarkand, Moscow–Samarkand, and Astana–Samarkand.

-

Samarkand railway station

-

Afrasiyab (Talgo 250) high-speed train in Samarkand railway station

Between 1879 and 1891, the Russian Empire built the Trans-Caspian Railway to facilitate its expansion into Central Asia. The railway originated in Krasnovodsk (now Turkmenbashi) on the Caspian Sea coast. Its terminus was originally Samarkand, whose station first opened in May 1888. However, a decade later, the railway was extended eastward to Tashkent and Andijan, and its name was changed to Central Asian Railways. Nonetheless, Samarkand remained one of the largest and most important stations of the Uzbek SSR and Soviet Central Asia.

International relations

[edit]Samarkand is twinned with:[110]

Agra, India

Agra, India Balkh, Afghanistan

Balkh, Afghanistan Banda Aceh, Indonesia

Banda Aceh, Indonesia Cusco, Peru

Cusco, Peru Jūrmala, Latvia

Jūrmala, Latvia Kairouan, Tunisia

Kairouan, Tunisia Khujand, Tajikistan

Khujand, Tajikistan Krasnoyarsk, Russia

Krasnoyarsk, Russia Lahore, Pakistan

Lahore, Pakistan Liège, Belgium

Liège, Belgium Mary, Turkmenistan

Mary, Turkmenistan Merv, Turkmenistan

Merv, Turkmenistan Mexico City, Mexico

Mexico City, Mexico New Delhi, India

New Delhi, India Nishapur, Iran

Nishapur, Iran Plovdiv, Bulgaria

Plovdiv, Bulgaria Rio de Janeiro, Brazil

Rio de Janeiro, Brazil Samara, Russia

Samara, Russia Xi'an, China

Xi'an, China Nara, Japan[111]

Nara, Japan[111]

In literature

[edit]The frame story of One Thousand and One Nights involves a Sasanian king who assigns his brother, Shah Zaman, to rule over Samarkand.[113]

The poet James Elroy Flecker published the poem The Golden Journey to Samarkand in 1913. It was included in his play, Hassan. Hassan (The Story of Hassan of Bagdad and How He Came to Make the Golden Journey to Samarkand) is a five-act drama in prose with verse passages. It tells the story of Hassan, a young man from Baghdad who embarks on a journey to Samarkand. Along the way, he encounters various challenges and obstacles, including bandits, treacherous terrain, and political turmoil.

In 2002, Nobel Laureate Wole Soyinka titled his collection of poetry Samarkand and Other Markets I Have Known.[114]

English author Jonathan Stroud published his book The Amulet of Samarkand in 2003. The book contains no allusions to Samarkand other than namesake.[citation needed]

The city of Samarkand is famous for being the subject of an Uzbek tale called "The Rendezvous at Samarkand." It was recounted by a 12th-century Persian storyteller and mystic, Farid Al-Din Attar. In a legendary Baghdad, ruled by a powerful caliph, lived a young, healthy vizier. He seemed to have his whole life ahead of him. One day, he went to the city market, incognito, as he often did. Amidst the stalls of the spice merchants, he encountered a skeletal woman, who turned around as he passed and reached out to him. The vizier, a wise man, immediately recognized death. Terrified by what he saw, he begged his caliph to let him flee Baghdad, explaining that death was here and wanted to take him. His only hope was to immediately saddle his fastest horse and gallop off far from the city. The caliph therefore granted him permission to leave and asked him where he would be going. The vizier replies that to escape death, he is going to Samarkand, the desert city, on the edge of the kingdom, on the borders of Asia and the Middle East, thinking he will be safe there, far from the death that lurks in Baghdad! However, the caliph also decides to go to the market to check for the presence of death. He recognizes her very quickly and addresses her without fear, asking her the meaning of the gesture she made towards the vizier. "It was only a gesture of surprise..." replies death "Because I saw him in Baghdad while I must take him tonight in Samarkand..." This tale illustrates the inevitability of human destiny in the face of death. [citation needed]

This tale also inspired Agatha Christie to title her novel "Appointment with Death."[citation needed]

Notable people

[edit]- Bakhtiyor Fazilov

- Takhmina Ikromova, Uzbek rhythmic gymnast

- Igor Sarukhanov, Russian pop musician, composer and artist of Armenian descent

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ /ˈsæmərkænd/ SAM-ər-kand; Uzbek and Tajik: Самарқанд, romanized: Samarqand, IPA: [sæmærˈqænd, -ænt].

Citations

[edit]- ^ "The State Committee of the Republic of Uzbekistan on Statistics". Archived from the original on 2020-04-29. Retrieved 2020-04-26.

- ^ "Classification system of territorial units of the Republic of Uzbekistan" (in Uzbek and Russian). The State Committee of the Republic of Uzbekistan on statistics. July 2020.

- ^ "Urban and rural population by district" (in Uzbek). Samarkand regional department of statistics. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2022-02-13.

- ^ Varadarajan, Tunku (24 October 2009). "Metropolitan Glory". The Wall Street Journal.

- ^ Guidebook of history of Samarkand", ISBN 978-9943-01-139-7

- ^ NikTalab, Poopak (2019). From the Alleyways of Samarkand to the Mediterranean Coast (The Evolution of the World of Child and Adolescent Literature). Tehran, Iran: Faradid publishing. pp. 18–27. ISBN 9786226606622.

- ^ "History of Samarkand". Sezamtravel. Archived from the original on 3 November 2013. Retrieved 1 November 2013.

- ^ Энциклопедия туризма Кирилла и Мефодия. 2008.

- ^ "History of Samarkand". Advantour. Archived from the original on 2018-05-16. Retrieved 2018-05-15.

- ^ "The Persian-speaking cities of Bukhara and Samarkand, rightly considered by today’s Tajiks as the constituting the historical centres of Tajik civilization" Foltz, Richard. A History of the Tajiks: Iranians of the East. I.B. Tauris, 2019. p.9

- ^ D.I. Kertzer/D. Arel, Census and identity Archived 2022-11-17 at the Wayback Machine, Cambridge University Press, 2001, pp. 186–188.

- ^ Room, Adrian (2006). Placenames of the World: Origins and Meanings of the Names for 6,600 Countries, Cities, Territories, Natural Features and Historic Sites (2nd ed.). London: McFarland. p. 330. ISBN 978-0-7864-2248-7.

Samarkand City, southeastern Uzbekistan. The city here was already named Marakanda, when captured by Alexander the Great in 329 BCE. Its own name derives from the Sogdian words samar, "stone, rock", and kand, "fort, town".

- ^ Sachau, Edward C. Alberuni’s India: an Account of the Religion. Philosophy, Literature, Geography, Chronology, Astronomy, Customs, Laws and Astrology of India about AD 1030, vol. 1 London: KEGAN PAUL, TRENCH, TRtJBNBR & CO. 1910. p.298.

- ^ al-Kashghari, Mahmud (1074). Compendium of The Turkic Dialects. Part 1. Translated by Dankoff, Robert; Kelly, James Michael. Harvard University Printing Office (published 1982). p. 270 – via Archive.org.

sämiz känd meaning "Fat city (balda samina)" is called thus because of its great size; it is, in Persian, Samarqand.

- ^ Ragagnin, Elisabetta (2020). "About Marco Polo Samarkand". Uzbekistan: Language and Culture. 3 (3). Alisher Navo’i Tashkent State University of Uzbek Language and Literature: 79–87. ISSN 2181-922X. Archived from the original on 2024-01-23. Retrieved 2024-01-23.

- ^ Vladimir Babak, Demian Vaisman, Aryeh Wasserman, Political organization in Central Asia and Azerbaijan: sources and documents, p. 374

- ^ Hanks, Reuel R. (19 February 2024). Historical Dictionary of Uzbekistan. Bloomsbury Publishing PLC. ISBN 978-1-5381-0229-9.

- ^ Columbia-Lippincott Gazetteer (New York: Columbia University Press, 1972 reprint) p. 1657

- ^ Wood, Frances (2002). The Silk Road: Two Thousand Years in the Heart of Asia. Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press. ISBN Berkeley and Los Angeles.

{{cite book}}: Check|isbn=value: invalid character (help) - ^ Shichkina, G.V. (1994). "Ancient Samarkand: Capital of Soghd". Bulletin of the Asia Institute. 8: 83.

- ^ Shichkina, G.V. (1994). "Ancient Samarkand: capital of Soghd". Bulletin of the Asia Institute. 8: 86.

- ^ a b Dumper, Stanley (2007). Cities of the Middle East and North Africa: A Historical Encyclopedia. California: ABC-CLIO. pp. 319–320.

- ^ Grenet Frantz, Regional interaction in Central Asia and northwest India in the Kidarite and Hephthalites periods in Indo-Iranian languages and peoples. Edited by Nicholas Sims-Williams. Oxford university press, 2003. Р.219–220

- ^ Buryakov Y.F. Iz istorii arkheologicheskikh rabot v zonakh oroshayemogo zemledeliya Uzbekistana // Arkheologicheskiye raboty na novostroykakh Uzbekistana. Tashkent, 1990. pp. 9–10.

- ^ Etienne de la Vaissiere, Sogdian traders. A history. Translated by James Ward. Brill. Leiden. Boston, 2005, pp. 108–111.

- ^ Baumer, Christoph (18 April 2018). History of Central Asia, The: 4-volume set. Bloomsbury Publishing. p. 243. ISBN 978-1-83860-868-2.

- ^ Grenet, Frantz (2004). "Maracanda/Samarkand, une métropole pré-mongole". Annales. Histoire, Sciences Sociales. 5/6: Fig. B.

- ^ Bivar, A.D.H. Encyclopedia Iranica, Vol. XII, Fasc. 2. London et al. pp. 198–201.

- ^ History of Civilizations of Central Asia: The crossroads of civilizations, AD 250 to 750. Vol. 3. Unesco, 1996. p. 332

- ^ Belenitskiy A.M., Bentovich I.B., Bolshakov O.G. Srednevekovyy gorod Sredney Azii. L., 1973.

- ^ Sprishevskiy V.I. Pogrebeniye s konem serediny I tysyacheletiya n.e., obnaruzhennoye okolo observatorii Ulugbeka. // Tr. Muzeya istorii narodov Uzbekistana. T.1.- Tashkent, 1951.

- ^ Klyashtornyy S. G., Savinov D. G., Stepnyye imperii drevney Yevrazii. Sankt-Peterburg: Filologicheskiy fakul'tet SPbGU, 2005 god, s. 97

- ^ Masson M.Ye., Proiskhozhdeniye dvukh nestorianskikh namogilnykh galek Sredney Azii // Obshchestvennyye nauki v Uzbekistane, 1978, №10, p. 53.

- ^ Sims-Williams Nicholas, A Christian sogdian polemic against the manichaens // Religious themes and texts of pre-Islamic Iran and Central Asia. Edited by Carlo G. Cereti, Mauro Maggi and Elio Provasi. Wiesbaden: Dr. Ludwig Reichert Verlag, 2003, pp. 399–407

- ^ Tadjikistan : au pays des fleuves d'or. Paris: Musée Guimet. 2021. p. 152. ISBN 978-9461616272.

- ^ Dumper, Stanley (2007). Cities of the Middle East and North Africa: A Historical Encyclopedia. California.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ a b Wellhausen, J. (1927). Weir, Margaret Graham (ed.). The Arab Kingdom and its Fall. University of Calcutta. pp. 437–438. ISBN 9780415209045. Archived from the original on 2019-04-21. Retrieved 2019-05-04.

{{cite book}}: ISBN / Date incompatibility (help) - ^ Whitfield, Susan (1999). Life Along the Silk Road. California: University of California Press. p. 33.

- ^ Bartold V. V., Abu Muslim//Akademik V. V. Bartol'd. Sochineniya. Tom VII. Moskva: Nauka, 1971

- ^ Quraishi, Silim "A survey of the development of papermaking in Islamic Countries", Bookbinder, 1989 (3): 29–36.

- ^ Dumper, Stanley (2007). Cities of the Middle East and North Africa: A Historical Encyclopedia. California. p. 320.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ a b c Kochnev B. D., Numizmaticheskaya istoriya Karakhanidskogo kaganata (991—1209 gg.). Moskva «Sofiya», 2006

- ^ Nemtseva, N.B., Shvab, IU. Ansambl Shah-i Zinda: istoriko-arkhitektymyi ocherk. Tashent: 1979.

- ^ Karev, Yury. Qarakhanid wall paintings in the citadel of Samarqand: First report and preliminary observations in Muqarnas 22 (2005): 45–84.

- ^ "Samarkand Travel Guide". Caravanistan. Retrieved 2021-03-20.

- ^ Jacques Gernet (31 May 1996). A History of Chinese Civilization. Cambridge University Press. pp. 377–. ISBN 978-0-521-49781-7. Archived from the original on 15 June 2016. Retrieved 25 January 2020.

- ^ E.J.W. Gibb memorial series. 1928. p. 451.

- ^ E. Bretschneider (1888). "The Travels of Ch'ang Ch'un to the West, 1220–1223 recorded by his disciple Li Chi Ch'ang". Mediæval Researches from Eastern Asiatic Sources. Barnes & Noble. pp. 37–108. Archived from the original on 2018-04-30. Retrieved 2018-04-26.

- ^ Battutah, Ibn (2002). The Travels of Ibn Battutah. London: Picador. p. 143. ISBN 9780330418799.

- ^ Encyclopædia Britannica, 15th Ed, p. 204

- ^ Malikov Azim, The cultural traditions of urban planning in Samarkand during the epoch of Timur. In: Baumer, C., Novák, M. and Rutishauser, S., Cultures in Contact. Central Asia as Focus of Trade, Cultural Exchange and Knowledge Transmission. Harrassowitz. 2022, p.343

- ^ a b c d e f g Marefat, Roya (Summer 1992). "The Heavenly City of Samarkand". The Wilson Quarterly. 16 (3): 33–38. JSTOR 40258334.

- ^ Wood, Frances (2002). The Silk Road: Two Thousand Years in the Heart of Asia. Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press. pp. 136–137. ISBN Berkeley and Los Angeles.

{{cite book}}: Check|isbn=value: invalid character (help) - ^ a b Columbia-Lippincott Gazetteer, p. 1657

- ^ Le Strange, Guy (trans) (1928). Clavijo: Embassy to Tamburlaine 1403–1406. London. p. 280.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ "Ulugh Beg – Biography". Maths History.

- ^ Ulugh Beg. Dictionary of Scientific Biography.

- ^ a b Mukminova R. G., K istorii agrarnykh otnosheniy v Uzbekistane XVI veke. Po materialam «Vakf-name». Tashkent. Nauka. 1966

- ^ Fazlallakh ibn Ruzbikhan Isfakhani. Mikhman-name-yi Bukhara (Zapiski bukharskogo gostya). M. Vostochnaya literatura. 1976, p. 3

- ^ B.V. Norik. Rol' shibanidskikh praviteley v literaturnoy zhizni Maverannakhra XVI veka. Sankt-Peterburg: Rakhmat-name, 2008. p. 233.

- ^ "ZARAFSHON SUVAYIRGʻICH KOʻPRIGI". uzsmart.uz. Retrieved 2023-11-14.

- ^ "МОСТ ШЕЙБАНИ-ХАНА". www.centralasia-travel.com. Retrieved 2023-11-14.

- ^ Britannica. 15th Ed, p. 204

- ^ Columbia-Lippincott Gazetteer. p. 1657

- ^ Materialy po istorii Sredney i Tsentral'noy Azii X—XIX veka. Tashkent: Fan, 1988, рр. 270—271

- ^ "Советское Поле Славы". www.soldat.ru. Archived from the original on April 13, 2020.

- ^ Rustam Qobil (2017-05-09). "Why were 101 Uzbeks killed in the Netherlands in 1942?". BBC. Archived from the original on 2020-03-30. Retrieved 2017-05-09.

- ^ Montgomery David. Samarkand taarikhi (History of Samarkand) by I.M.Muminov, The American historical review, volume 81, no.8 (October 1976), pp. 914–915

- ^ Istoriya Samarkanda v dvukh tomakh. Pod redaktsiyey I. Muminova. Tashkent, 1970

- ^ Montgomery David, Review of Samarkand taarikhi by I. M. Muminov et al. // The American historical review, volume 81, no. 4 (October 1976)

- ^ Shirinov T.SH., Isamiddinov M.KH. Arkheologiya drevnego Samarkanda. Tashkent, 2007

- ^ Malikov A.M. Istoriya Samarkanda (s drevnikh vremen do serediny XIV veka). Tom. 1. Tashkent: Paradigma, 2017.

- ^ "Samarkand, Uzbekistan". Earthobservatory.nasa.gov. 23 September 2013. Archived from the original on 2015-09-17. Retrieved 2014-08-23.

- ^ Samarkand.info. "Weather in Samarkand". Archived from the original on 2009-06-04. Retrieved 2009-06-11.

- ^ "Weather and Climate-The Climate of Samarkand" (in Russian). Weather and Climate. Retrieved 18 January 2021.

- ^ "Samarkand, Uzbekistan – Detailed climate information and monthly weather forecast". Weather Atlas. Retrieved 1 August 2022.

- ^ "Climate & Weather Averages in Samarkand". Time and Date. Retrieved 24 July 2022.

- ^ "Samarkand Climate Normals 1991–2020". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved November 1, 2023.

- ^ Akiner, Shirin; Djalili, Mohammad-Reza; Grare, Frederic (2013). Tajikistan: The Trials of Independence. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-136-10490-9 p. 78, "Bukhara and Samarkand, inhabited by a marked Tajik majority (...)"

- ^ a b Lena Jonson (1976) "Tajikistan in the New Central Asia", I.B.Tauris, p. 108: "According to official Uzbek statistics there are slightly over 1 million Tajiks in Uzbekistan or about 3% of the population. The unofficial figure is over 6 million Tajiks. They are concentrated in the Sukhandarya, Samarqand and Bukhara regions."

- ^ a b "Узбекистан: Таджикский язык подавляется". catoday.org — ИА "Озодагон". Archived from the original on 22 March 2019. Retrieved 22 March 2019.

- ^ a b "Таджики – иранцы Востока? Рецензия книги от Камолиддина Абдуллаева". «ASIA-Plus» Media Group / Tajikistan — news.tj. Archived from the original on 27 March 2019. Retrieved 22 March 2019.

- ^ Richard Foltz (1996). "The Tajiks of Uzbekistan". Central Asian Survey. 15 (2): 213–216. doi:10.1080/02634939608400946.

- ^ a b Paul Bergne: The Birth of Tajikistan. National Identity and the Origins of the Republic. International Library of Central Asia Studies. I.B. Tauris. 2007. Pg. 106

- ^ Marushiakova; Popov, Vesselin (January 2014). Migrations and Identities of Central Asian 'Gypsies'. Asia Pacific Sociological Association (APSA) Conference "Transforming Societies: Conestations and Convergences in Asia and the Pacific". doi:10.1057/ces.2008.3. S2CID 154689140. Retrieved 2022-02-28.

- ^ Karl Cordell, "Ethnicity and Democratisation in the New Europe", Routledge, 1998. p. 201: "Consequently, the number of citizens who regard themselves as Tajiks is difficult to determine. Tajikis within and outside of the republic, Samarkand State University (SamGU) academic and international commentators suggest that there may be between six and seven million Tajiks in Uzbekistan, constituting 30% of the republic's 22 million population, rather than the official figure of 4.7% (Foltz 1996: 213; Carlisle 1995: 88).

- ^ "Статус таджикского языка в Узбекистане". Лингвомания.info — lingvomania.info. Archived from the original on 29 October 2016. Retrieved 22 March 2019.

- ^ "Есть ли шансы на выживание таджикского языка в Узбекистане — эксперты". "Биржевой лидер" — pfori-forex.org. Archived from the original on 22 March 2019. Retrieved 22 March 2019.

- ^ a b Foltz, Richard (2023). A History of the Tajiks: Iranians of the East, 2nd edition. Bloomsbury Publishing. p. 186. ISBN 978-0-7556-4964-8.

- ^ Samarkand Marathon.

- ^ Malikov Azim, Sacred lineages of Samarqand: history and identity in Anthropology of the Middle East, Volume 15, Issue 1, Summer 2020, р.36

- ^ https://www.ajol.info/index.php/ijma/article/view/218533 Malikov A. and Djuraeva D. 2021. Women, Islam, and politics in Samarkand (1991–2021), International Journal of Modern Anthropology. 2 (16): 561

- ^ "Шииты в Узбекистане". www.islamsng.com. Archived from the original on October 3, 2017. Retrieved April 3, 2019.

- ^ "Ташкент озабочен делами шиитов". www.dn.kz. Archived from the original on 2019-04-03. Retrieved April 3, 2019.

- ^ "Узбекистан: Иранцы-шииты сталкиваются c проблемами с правоохранительными органами". catoday.org. Archived from the original on September 5, 2017. Retrieved April 3, 2019.

- ^ Dickens, Mark "Nestorian Christianity in Central Asia. p. 17

- ^ В. А. Нильсен. У истоков современного градостроительства Узбекистана (ΧΙΧ — начало ΧΧ веков). —Ташкент: Издательство литературы и искусства имени Гафура Гуляма, 1988. 208 с.

- ^ Голенберг В. А. «Старинные храмы туркестанского края». Ташкент 2011 год

- ^ Католичество в Узбекистане. Ташкент, 1990.

- ^ Armenians. Ethnic atlas of Uzbekistan, 2000.

- ^ Назарьян Р.Г. Армяне Самарканда. Москва. 2007

- ^ Бабина Ю. Ё. Новые христианские течения и страны мира. Фолкв, 1995.

- ^ "Silk Road Samarkand Tourist Complex". Advantour. Retrieved 2023-01-20.

- ^ "Eternal City". www.silkroad-samarkand.com. Retrieved 2023-01-20.

- ^ Liu, Xinru (2010). The Silk Road in world history. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-516174-8.

- ^ Cohn-Wiener, Ernst (June 1935). "An Unknown Timurid Building". The Burlington Magazine for Connoisseurs. 66 (387): 272–273+277. JSTOR 866154.

- ^ a b "Samarkand – Crossroad of Cultures". UNESCO World Heritage Centre. Archived from the original on 2018-05-16. Retrieved 2018-05-15.

- ^ "Textiles in "The world of Kubilai Khan" @ Metropolitan Museum, New York". Alain.R.Truong. 25 December 2010. Archived from the original on 2019-11-18. Retrieved 2020-05-23.

- ^ "Superfosfatnyy · Uzbekistan". Superfosfatnyy · Uzbekistan.

- ^ a b "Самарканд и Валенсия станут городами-побратимами". podrobno.uz (in Russian). 2018-01-27. Retrieved 2020-11-15.

- ^ "A brotherhood agreement has been signed between the cities of Nara and Samarkand".

- ^ "Внешнеэкономическое сотрудничество". bobruisk.by (in Russian). Babruysk. Archived from the original on 2020-10-28. Retrieved 2020-11-15.

- ^ Burton, Richard (2011). Mondschein, Ken (ed.). The Arabian Nights. Canterbury Classics. p. 1. ISBN 978-1-60710-309-7.

- ^ "Samarkand and Other Markets I Have Known | poetry by Soyinka | Britannica". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 2023-09-17.

General and cited references

[edit]- Azim Malikov, "Cult of saints and shrines in the Samarqand province of Uzbekistan". International Journal of Modern Anthropology. No. 4. 2010, pp. 116–123.

- Azim Malikov, "The politics of memory in Samarkand in post-Soviet period". International Journal of Modern Anthropology. (2018) Vol. 2. Issue No. 11. pp. 127–145.

- Azim Malikov, "Sacred lineages of Samarqand: history and identity". Anthropology of the Middle East, Volume 15, Issue 1, Summer 2020, рp. 34–49.

- Alexander Morrison, Russian Rule in Samarkand 1868–1910: A Comparison with British India (Oxford, OUP, 2008) (Oxford Historical Monographs).

External links

[edit]- Forbes, Andrew, & Henley, David: Timur's Legacy: The Architecture of Bukhara and Samarkand (CPA Media).

- Samarkand – Silk Road Seattle Project, University of Washington

- The history of Samarkand, according to Columbia University's Encyclopædia Iranica (archived 11 March 2007)

- Samarkand – Crossroad of Cultures. UNESCO World Heritage Committee documentation on Samarkand.

- Kropotkin, Peter Alexeivitch; Bealby, John Thomas (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 24 (11th ed.). pp. 112–113.

- GCatholic – former Latin Catholic bishopric

- Samarkand: Photos, History, Sights, Useful information for travelers

- About Samarkand in Uzbekistan Latest (archived 18 August 2018)

- Tilla-Kori Madrasa was included in the UNESCO World Heritage List Archived 2019-07-02 at the Wayback Machine

Samarkand

View on GrokipediaEtymology

Origins and Interpretations

The name Samarkand originates from the Sogdian language, an Eastern Iranian tongue spoken by the ancient inhabitants of the region, where it combines samar, denoting "stone" or "rock," with kand, signifying "fort" or "town," yielding the meaning "stone fort."[6][7] This designation likely alluded to the city's defensive structures built from local stone materials in the Zeravshan River valley, a key oasis amid arid surroundings that supported early settlement.[8] Archaeological evidence from the Afrosiyab hill, the site's ancient core, corroborates fortified enclosures dating back to at least the 8th century BCE, aligning with the etymological emphasis on fortification.[9] Under Achaemenid Persian rule in the 6th century BCE, the city was recorded as Marakanda in administrative texts, serving as the principal center of Sogdiana satrapy.[8][10] This form, phonetically akin to the Sogdian precursor, appears in Greek accounts following Alexander the Great's campaigns, preserving the core consonants while adapting to Old Persian phonology.[11] Subsequent linguistic shifts occurred with Arab conquest in the 8th century CE, rendering the name Samarqand in Arabic script, which emphasized the initial "s" sound and integrated it into Islamic historiography.[12] Turkic influences from the 11th century onward standardized it as Samarkand, reflecting phonetic assimilation in Chagatai Turkish while maintaining the original Sogdian structure. Alternative interpretations, such as derivations from Turkish "simiz kent" meaning "rich settlement," lack robust philological support and appear as later folk etymologies tied to the city's prosperity rather than primary linguistic roots.[13]History

Ancient Foundations and Achaemenid Rule

Archaeological evidence from the Afrasiab hill, the ancient core of Samarkand, indicates initial settlement activity dating to the 8th-7th centuries BCE, with layers revealing early urban planning and pottery shards consistent with local Central Asian cultures.[14] Excavations conducted since the late 19th century, including those by Russian archaeologist Nikolay Veselovsky, have uncovered structural remains suggesting organized habitation on this elevated site overlooking the Siab River, which provided natural defenses on the north.[15] By the mid-6th century BCE, the region of Sogdiana, including the settlement at Marakanda (the ancient name for Samarkand), fell under Achaemenid Persian control following Cyrus the Great's conquests, becoming the capital of the Sogdian satrapy.[16] This integration facilitated Samarkand's role as a strategic trade outpost linking Persian territories with Central Asian nomadic routes, as evidenced by the empire's administrative records and the site's position on emerging overland paths.[17] Achaemenid influence is apparent in enhanced fortifications, including massive walls encircling the city with internal hallways, towers, and reliance on river cliffs for defense, adaptations likely implemented to secure the satrapy against incursions. Artifacts from this period, such as ceramics and tools, reflect Zoroastrian cultural elements prevalent among the Iranian-speaking Sogdians, including ossuaries indicative of exposure burial practices aligned with the faith's tenets, though direct fire altar remains are scarce in early strata.[9] These findings underscore the site's evolution from a local stronghold to an imperial administrative center under Persian rule.[18]Alexander's Conquest and Hellenistic Influence

In 329 BCE, Alexander the Great advanced into Sogdia following the defeat of Bessus, the satrap who had usurped the Persian throne, and targeted Marakanda as the region's primary stronghold.[8] Macedonian forces first subdued resistant towns along the Jaxartes River, including Cyropolis, where Arrian records significant combat resulting in the deaths of numerous defenders during assaults on fortified positions.[19] Marakanda's inhabitants, facing the destruction of these outposts, surrendered without a prolonged siege, allowing Alexander to occupy the city and incorporate it into his empire.[8] This event effectively dismantled the independent Sogdian political framework under local dynasts, replacing it with direct Macedonian oversight.[20] The imposition of Hellenistic elements began with the establishment of garrisons comprising Greek and Macedonian settlers, who enforced tax collection and military recruitment in ways that clashed with prior decentralized Sogdian tribal systems reliant on fortified refuges and nomadic alliances.[16] Administrative changes included the appointment of satraps loyal to Alexander, such as those drawn from his entourage, which prioritized imperial supply lines over local customs and provoked revolts like the one orchestrated by Spitamenes, who exploited the overextended Macedonian positions.[21] These uprisings demonstrated the causal limits of conquest through superior infantry tactics alone, as guerrilla warfare in the rugged terrain undermined sustained control and necessitated constant reinforcement from Bactria.[20] Cultural impositions were modest during Alexander's brief oversight, featuring the introduction of Attic-standard coinage alongside overstuck Persian darics to facilitate trade and payments, though archaeological evidence from Marakanda shows continuity in local pottery and urban layouts rather than wholesale Greek redesign.[16] Strategic marriages, including Alexander's union with Roxana, daughter of the Sogdian lord Oxyartes near the Rock of Sogdiana, aimed to forge alliances but primarily served to secure hostages and intelligence amid ongoing resistance.[8] The era's tensions culminated in incidents like the slaying of Cleitus the Black during a drunken banquet in Marakanda, underscoring internal Macedonian strains from prolonged campaigns in alien territories.[19] Overall, the Hellenistic overlay disrupted Sogdian autonomy without establishing enduring institutions, paving the way for successor states to contend with the same integration challenges.[16]Sasanian and Hephthalite Dominance

The Sasanian Empire asserted control over Sogdiana, encompassing Samarkand, in the 3rd century CE, following campaigns against Kushan remnants, with Shapur I's Res Gestae Divi Saporis inscription from around 260 CE claiming the subjugation of Sogdian territories as a satrapy.[22] This period saw the reinforcement of Zoroastrian institutions, as Sasanian administrators promoted fire temples and priestly hierarchies amid local Iranian traditions, evidenced by archaeological discoveries of Sasanian-style seals and ceramics in eastern outposts like Paykand, suggesting cultural oversight rather than unbroken direct rule.[23] Samarkand's strategic location facilitated persistent Silk Road commerce, with Sogdian merchants navigating tributary obligations to maintain exchange networks despite intermittent Sasanian military expeditions. From the mid-5th century, the Hephthalites—nomadic warriors known as White Huns—overran Sogdiana, conquering Samarkand and adjacent areas by circa 440–479 CE after displacing Kidarite predecessors and extending into Bactria.[24] Their dominance featured fortified suburbs and administrative hubs, such as the nearby Piandjikent complex, which served as a regional capital with murals depicting Hephthalite-influenced elite interactions.[25] Local Sogdian rulers operated under a tribute system, remitting goods and levies to Hephthalite overlords, while records of sporadic revolts and alliances highlight resistance, including appeals to Sasanian aid against nomadic incursions. Hephthalite control, lasting until the 560s CE, imposed nomadic fiscal demands that strained urban economies but preserved trade flux, as Sogdian caravaneers adapted to exactions while channeling goods from China to Persia.[26] This era underscored causal tensions between steppe mobility and settled commerce, with empirical coin hoards and fortification expansions at Afrasiyab attesting to defensive adaptations without romanticized harmony.[22] The joint Sasanian-Turkic campaigns culminating in Hephthalite defeat around 567 CE briefly restored Iranian influence, yet underscored the fragility of dominance in the region.[27]Arab Conquest and Early Islamic Integration

The Arab conquest of Samarkand occurred in 712 CE under Qutayba ibn Muslim, the Umayyad governor of Khorasan, as part of the broader Muslim campaigns into Transoxiana.[28] Following the subjugation of Bukhara and other Sogdian strongholds, Qutayba's forces besieged the fortified city, overcoming resistance from local rulers allied with Turkic tribes.[29] The siege culminated in the city's capitulation, with terms imposed including heavy tribute payments and the installation of Arab garrisons to secure control.[30] Initial integration involved coercive measures, such as mass conversions among the population to avoid jizya taxes, though Zoroastrianism persisted among elites for decades.[31] Qutayba ordered the construction of the first mosque in Samarkand shortly after the conquest, symbolizing the imposition of Islamic authority over Sogdian administrative structures.[32] Local dihqans, the hereditary landowners, faced displacement as Arab administrators supplanted them, disrupting traditional power dynamics and accelerating the erosion of Sogdian autonomy.[33] This shift prioritized fiscal extraction, with the city's wealth redirected to Umayyad coffers via systematic taxation.[34] Under the subsequent Abbasid Caliphate from 750 CE, Samarkand experienced renewed prosperity as a key Silk Road entrepôt, facilitating trade between China and the Mediterranean.[35] The caliphs' policies fostered economic stability, evidenced by increased caravan traffic and artisanal output, though non-Muslim communities remained subject to orthodox Islamic governance that curtailed prior religious pluralism.[12] Rebellions, such as those by Sogdian princes in the 740s, underscored tensions from imposed orthodoxy, yet military reprisals ensured gradual Islamization through incentives and demographic changes.[36] By the late 8th century, the city hosted diwans for tax collection, integrating it into the caliphal bureaucracy while local elites adapted by converting to maintain influence.[31]Karakhanid and Seljuk Flourishing