Recent from talks

Contribute something

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Prostitution

View on Wikipedia

Femmes de Maison, painting by Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec, c. 1893—1895 | |

| Occupation | |

|---|---|

Activity sectors | Sex industry |

| Description | |

Fields of employment | Sex work |

Related jobs | Stripper, porn actor, sex worker, sugar dating |

Prostitution is a type of sex work that involves engaging in sexual activity in exchange for payment.[1][2] The definition of "sexual activity" varies, and is often defined as an activity requiring physical contact (e.g., sexual intercourse, non-penetrative sex, manual sex, oral sex, etc.) with the customer.[3] The requirement of physical contact also creates the risk of transferring infections. Prostitution is sometimes described as sexual services, commercial sex or, colloquially, hooking. It is sometimes referred to euphemistically as "the world's oldest profession" in the English-speaking world.[4][5] A person who works in the field is usually called a prostitute or sex worker, but other words, such as hooker and whore, are sometimes used pejoratively to refer to those who work in prostitution. The majority of prostitutes are female and have male clients.[6][7]

Prostitution occurs in a variety of forms, and its legal status varies from country to country (sometimes from region to region within a given country). In most cases, it can be either an enforced crime, an unenforced crime, a decriminalized activity, a legal but unregulated activity, or a regulated profession. It is one branch of the sex industry, along with pornography, stripping, and erotic dancing. Brothels are establishments specifically dedicated to prostitution. In escort prostitution, the act may take place at the client's residence or hotel room (referred to as out-call), or at the escort's residence or a hotel room rented for the occasion by the escort (in-call). Another form is street prostitution.

According to a 2011 report by Fondation Scelles there are about 42 million prostitutes in the world, living all over the world (though most of Central Asia, the Middle East and Africa lack data, studied countries in that large region rank as top sex tourism destinations).[8] Estimates place the annual revenue generated by prostitution worldwide to be over $100 billion.[9]

The position of prostitution and the law varies widely worldwide, reflecting differing opinions. Some view prostitution as a form of exploitation of or violence against women,[10] and children,[11] that helps to create a supply of victims for human trafficking.[12][13] Some critics of prostitution as an institution are supporters of the "Nordic model" that decriminalizes the act of selling sex and makes the purchase of sex illegal. This approach has also been adopted by Canada, Iceland, Ireland,[14] Northern Ireland, Norway, France and Sweden. Others view sex work as a legitimate occupation, whereby a person trades or exchanges sexual acts for money. Amnesty International is one of the notable groups calling for the decriminalization of prostitution.[15]

Etymology and terminology

[edit]General

[edit]

Prostitute is derived from the Latin prostituta. Some sources cite the verb as a composition of "pro" meaning "up front" or "forward" and "stituere", defined as "to offer up for sale".[16] Another explanation is that prostituta is a composition of pro and statuere (to cause to stand, to station, place erect). A literal translation therefore is: "to put up front for sale" or "to place forward". The Online Etymology Dictionary states: "The notion of 'sex for hire' is not inherent in the etymology, which rather suggests one 'exposed to lust' or sex 'indiscriminately offered'."[17][18]

The word prostitute was then carried down through various languages to the present-day Western society. Most sex worker activists groups reject the word prostitute and since the late 1970s have used the term sex worker instead. However, sex worker can also mean anyone who works within the sex industry or whose work is of a sexual nature and is not limited solely to prostitutes.[19][20]

A variety of terms are used for those who engage in prostitution, some of which distinguish between different types of prostitution or imply a value judgment about them. This terminology is hotly contested among scholars.[21] Common alternatives for prostitute include escort and whore; however, not all professional escorts are prostitutes.

The English word whore derives from the Old English word hōra, from the Proto-Germanic *hōrōn (prostitute), which derives from the Proto-Indo-European root *keh₂- meaning "desire", a root which has also given us Latin cārus (dear), whence the French cher (dear, expensive) and the Latin cāritās (love, charity). Use of the word whore is widely considered pejorative, especially in its modern slang form of ho. In Germany, however, most prostitutes' organizations deliberately use the word Hure (whore) since they feel that prostitute is a bureaucratic term.[citation needed]

Those seeking to remove the social stigma associated with prostitution often promote terminology such as sex worker, commercial sex worker (CSW) or sex trade worker. Another commonly used word for a prostitute is hooker. Although a popular etymology connects "hooker" with Joseph Hooker, a Union general in the American Civil War, the word more likely comes from the concentration of prostitutes around the shipyards and ferry terminal of the Corlear's Hook area of Manhattan in the 1820s, who came to be referred to as "hookers".[22] A streetwalker solicits customers on the streets or in public places, while a call girl makes appointments by phone, or other means of communication.

Correctly or not, the use of the word prostitute without specifying a sex may commonly be assumed to be female; compound terms such as male prostitution or male escort are therefore often used to identify males. Those offering services to female customers are commonly known as gigolos; those offering services to male customers are hustlers or rent boys.

Procuring

[edit]

Organizers of prostitution may be known colloquially as pimps if male or madams if female. More formally, one who is said to practice procuring is a procurer, or procuress.[23] They may also be called panderers or brothel keepers.

Examples of procuring include:

- deriving financial gain from the prostitution of another

- operating a prostitution business

- trafficking a person into a country for the purpose of soliciting sex

- transporting a prostitute to the location of their arrangement

Clients

[edit]Clients of prostitutes, most often men by prevalence, are sometimes known as johns or tricks in North America and punters in Britain and Ireland. These slang terms are used among both prostitutes and law enforcement for persons who solicit prostitutes.[24] The term john may have originated from the frequent customer practice of giving one's name as "John", a common name in English-speaking countries, in an effort to maintain anonymity. In some places, men who drive around red-light districts for the purpose of soliciting prostitutes are also known as kerb crawlers.

Female clients of prostitutes are sometimes referred to as janes or sugar mamas.[25][26][27]

Other meanings

[edit]The word "prostitution" can also be used metaphorically to mean debasing oneself or working towards an unworthy cause or "selling out".[28] In this sense, "prostituting oneself" or "whoring oneself" the services or acts performed are typically not sexual. For instance, in the book The Catcher in the Rye, Holden Caulfield says of his brother ("D.B."): "Now he's out in Hollywood, D.B., being a prostitute. If there's one thing I hate, it's the movies. Don't even mention them to me." D.B. is not literally a prostitute; Holden feels that his job writing B-movie screenplays is morally debasing.

The prostitution metaphor, "traditionally used to signify political inconstancy, unreliability, fickleness, a lack of firm values and integrity, and venality, has long been a staple of Russian political rhetoric.[29] One of the famous insults of Leon Trotsky made by Joseph Stalin was calling him a "political prostitute".[29] Leon Trotsky used this epithet himself, calling German Social Democracy, at that time "corrupted by Kautskianism", a "political prostitution disguised by theories".[30] In 1938, he used the same description for the Comintern, saying that the chief aim of the Bonapartist clique of Stalin during the preceding several years "has consisted in proving to the imperialist 'democracies' its wise conservatism and love for order. For the sake of the longed alliance with imperialist democracies [Stalin] has brought the Comintern to the last stages of political prostitution."[31]

Besides targeting political figures, the term is used in relation to organizations and even small countries, which "have no choice but to sell themselves", because their voice in world affairs is insignificant. In 2007, a Russian caricature depicted the Baltic states as three "ladies of the night", "vying for the attentions of Uncle Sam, since the Russian client has run out of money".[29]

Usage of the "political prostitute" moniker is by no means unique to the Russian political lexicon, such as when a Huffington Post contributor expressed the opinion that Donald Trump was "prostituting himself to feed his ego and gain power" when he ran for President of the United States.[32]

Sex work researcher and writer Gail Pheterson writes that these metaphorical usages exist because "the term prostitute gradually took on a Christian moralist tradition, as being synonymous with debasement of oneself or of others for the purpose of ill-gotten gains".[33]

History

[edit]Europe

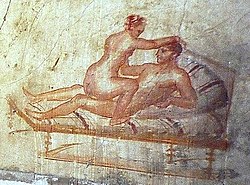

[edit]Ancient

[edit]

Although historically it was suggested that peoples of the Ancient Near East engaged in sacred prostitution based on accounts of ancient Greek authors like Herodotus, the veracity of these claims has been seriously questioned due to a lack of corroborating evidence.[34][35] Amongst the oldest reliable references to prostitution in ancient Greece comes from the Archaic era poet Anacreon ( c. 575 – c. 495 BC) in his poem about Artemon, which references "whores by choice". The record of prostitution in the classical period is better documented, and includes references to both free-born voluntary prostitutes, including the high social status hetairai, as well as involuntary slave prostitutes.[36] Male prostitutes also existed in Ancient Greece.[37]

There was never a unified legal approach to prostitution in ancient Rome.[38] In ancient Rome, prostitutes had low social status and were considered infamia.[39] Under the reign of emperor Caligula, a taxation on prostitution was implemented.[38] Roman slave owners were able to include the ne serva prostituatur covenant as part of slave sale contracts, which prohibited the slaves being forced to prostitute themselves by their owners after being sold.[40]

Middle Ages

[edit]Throughout the Middle Ages the definition of a prostitute has been ambiguous, with various secular and canonical organizations defining prostitution in constantly evolving terms. Even though medieval secular authorities created legislation to deal with the phenomenon of prostitution, they rarely attempted to define what a prostitute was because it was deemed unnecessary "to specify exactly who fell into that [specific] category" of a prostitute.[41] The first known definition of prostitution was found in Marseille's thirteenth-century statutes, which included a chapter entitled De meretricibus ("regarding prostitutes").[41] The Marseillais designated prostitutes as "public girls" who, day and night, received two or more men in their house, and as a woman who "did business trading [their bodies], within the confine[s] of a brothel."[42] A fourteenth-century English tract, Fasciculus Morum, states that the term prostitute (termed 'meretrix' in this document), "must be applied only to those women who give themselves to anyone and will refuse none, and that for monetary gain".[42] In general prostitution was not typically a lifetime career choice for women. Women usually alternated their career of prostitution with "petty retailing, and victualing," or only occasionally turned to prostitution in times of great financial need.[43] Women who became prostitutes often did not have the familial ties or means to protect themselves from the lure of prostitution, and it has been recorded on several occasions that mothers would be charged with prostituting their own daughters in exchange for extra money.[44] Medieval civilians accepted without question the fact of prostitution, it was a necessary part of medieval life.[45] Prostitutes subverted the sexual tendencies of male youth, just by existing. With the establishment of prostitution, men were less likely to collectively rape honest women of marriageable and re-marriageable age.[46] This is most clearly demonstrated in St. Augustine's claim that "the removal of the institution would bring lust into all aspects of the world."[47] Meaning that without prostitutes to subvert male tendencies, men would go after innocent women instead, thus the prostitutes were actually doing society a favor, according to Augustine.

In urban societies there was an erroneous view that prostitution was flourishing more in rural regions rather than in cities, however, it has been proven that prostitution was more rampant in cities and large towns.[48] Although there were wandering prostitutes in rural areas who worked according to the calendar of fairs, similar to riding a circuit, in which prostitutes stopped by various towns based on what event was going on at the time, most prostitutes remained in cities. Cities tended to draw more prostitutes due to the sheer size of the population and the institutionalization of prostitution in urban areas which made it more rampant in metropolitan regions.[48] Furthermore, in both urban and rural areas of society, women who did not live under the rule of male authority were more likely to be suspected of prostitution than their oppressed counterparts because of the fear of women who did not fit into a stereotypical category outside of marriage or religious life.[44]

Secular law, like most other aspects of prostitution in the Middle Ages, is difficult to generalize due to the regional variations in attitudes towards prostitution.[49] The global trend of the thirteenth century was toward the development of positive policy on prostitution as laws exiling prostitutes changed towards sumptuary laws and the confinement of prostitutes to red light districts.[50]

Sumptuary laws became the regulatory norm for prostitutes and included making courtesans "wear a shoulder-knot of a particular color as a badge of their calling" to be able to easily distinguish the prostitute from a respectable woman in society.[50] The color that designated them as prostitutes could vary from different earth tones to yellow, as was usually designated as a color of shame in the Hebrew communities.[51] These laws, however, proved no impediment to wealthier prostitutes because their glamorous appearances were almost indistinguishable from noble women.[52] In the 14th century, London prostitutes were only tolerated when they wore yellow hoods.[53]

Although brothels were still present in most cities and urban centers and could range from private bordelages run by a procuress from her home to public baths and centers established by municipal legislation, the only centers for prostitution legally allowed were the institutionalized and publicly funded brothels.[54] This did not prevent illegal brothels from thriving. Brothels theoretically banned the patronage of married men and clergy, but it was sporadically enforced and there is evidence of clergymen present in brawls that were documented in brothels.[55] Thus the clergy were at least present in brothels at some point or another. Brothels also settled the "obsessive fear of the sharing of women" and solved the issue of "collective security."[56] The lives of prostitutes in brothels were not cloistered like that of nuns and "only some lived permanently in the streets assigned to them."[57] Prostitutes were only allowed to practice their trade in the brothel in which they worked.[58] Brothels were also used to protect prostitutes and their clients through various regulations. For example, the law that "forbid brothel keepers [from] beat[ing] them."[59] However, brothel regulations also hindered prostitutes' lives by forbidding them from having "lovers other than their customers" or from having a favored customer.[59]

Courts showed conflicting views on the role of prostitutes in secular law as prostitutes could not inherit property, defend themselves in court, or make accusations in court.[60] However, prostitutes were sometimes called upon as witnesses during trial.[61]

16th–present

[edit]By the end of the 15th-century attitudes seemed to have begun to harden against prostitution. An outbreak of syphilis in Naples 1494 which later swept across Europe, and which may have originated from the Columbian Exchange,[62] and the prevalence of other sexually transmitted infections from the earlier 13th century, may have been causes of this change in attitude. By the early 16th century, the association between prostitutes, plague, and contagion emerged, causing brothels and prostitution to be outlawed by secular authority.[63] Furthermore, outlawing brothel-keeping and prostitution was also used to "strengthen the criminal law" system of the sixteenth-century secular rulers.[64] Canon law defined a prostitute as "a promiscuous woman, regardless of financial elements."[65] The prostitute was considered a "whore … who [was] available for the lust of many men," and was most closely associated with promiscuity.[66]

The Church's stance on prostitution was three-fold: "acceptance of prostitution as an inevitable social fact, condemnation of those profiting from this commerce, and encouragement for the prostitute to repent."[67] The Church was forced to recognize its inability to remove prostitution from the worldly society, and in the fourteenth century "began to tolerate prostitution as a lesser evil."[68] However, prostitutes were to be excluded from the Church as long as they practiced.[69] Around the twelfth century, the idea of prostitute saints took hold, with Mary Magdalene being one of the most popular saints of the era. The Church used Mary Magdalene's biblical history of being a reformed harlot to encourage prostitutes to repent and mend their ways.[70] Simultaneously, religious houses were established with the purpose of providing asylum and encouraging the reformation of prostitution. 'Magdalene Homes' were particularly popular and peaked especially in the early fourteenth century.[71] Over the course of the Middle Ages, popes and religious communities made various attempts to remove prostitution or reform prostitutes, with varying success.[72]

With the advent of the Protestant Reformation, numbers of Southern German towns closed their brothels in an attempt to eradicate prostitution.[73] In some periods prostitutes had to distinguish themselves by particular signs, sometimes wearing very short hair or no hair at all, or wearing veils in societies where other women did not wear them. Ancient codes regulated in this case the crime of a prostitute that dissimulated her profession. In some cultures, prostitutes were the sole women allowed to sing in public or act in theatrical performances.

In the 19th century, legalized prostitution became the center of public controversy as the British government passed the Contagious Diseases Acts, legislation mandating pelvic examinations for suspected prostitutes; they would remain in force until 1886. The French government, instead of trying to outlaw prostitution, began to view prostitution as a necessary evil for society to function. French politicians chose to regulate prostitution, introducing a "Morals Brigade" onto the streets of Paris.[74] A similar situation did in fact exist in the Russian Empire; prostitutes operating out of government-sanctioned brothels were given yellow internal passports signifying their status and were subjected to weekly physical exams. A major work, Prostitution, Considered in Its Moral, Social, and Sanitary Aspects, was published by William Acton in 1857, which estimated that the County of London had 80,000 prostitutes and that 1 house in 60 was serving as a brothel.[75] Leo Tolstoy's novel Resurrection describes legal prostitution in 19th-century Russia.

The leading Marxist theorists opposed prostitution. Communist governments often attempted to repress the practice immediately after obtaining power, although it always persisted. In most contemporary communist states, prostitution remained illegal but was nonetheless common.[76] The economic decline brought about by the collapse of the Soviet Union led to increased prostitution in many current and former Communist countries.[77]

In 1956, the United Kingdom introduced the Sexual Offences Act 1956. While this law did not criminalise the act of prostitution in the United Kingdom itself, it prohibited such activities as running a brothel. Soliciting was made illegal by the Street Offences Act 1959. These laws were partly repealed, and altered, by the Sexual Offences Act 2003 and the Policing and Crime Act 2009.

Since the break up of the Soviet Union, thousands of eastern European women end up as prostitutes in China, Western Europe, Israel, and Turkey every year. Some enter the profession willingly; many are tricked, coerced, or kidnapped, and often experience captivity and violence.[78] There are tens of thousands of women from eastern Europe and Asia working as prostitutes in Dubai. Men from Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates form a large proportion of the customers.[79]

Middle East

[edit]In the Islamic world, sex outside of marriage was normally acquired by men not by paying for temporary sex from a free sex worker, but rather by personal sex slave called concubine, which was a sex slave trade that was still ongoing in the early 20th-century.[80]

Traditionally, prostitution in the Islamic world was historically practiced by way of the pimp temporarily selling his slave to her client, who then returned the ownership of the slave after intercourse. The Islamic Law formally prohibited prostitution. However, since Islamic Law allowed a man to have sexual intercourse with his slave concubine, prostitution was practiced by a pimp selling his female slave on the slave market to a client, who returned his ownership on the pretext of discontent after having had intercourse with her, which was a legal and accepted method for prostitution in the Islamic world.[81] This form of prostitution was practiced by for example Ibn Batuta, who acquired several female slaves during his travels.[citation needed]

According to Shia Muslims, Muhammad sanctioned fixed-term marriage—muta'a in Iraq and sigheh in Iran—which has instead been used as a legitimizing cover for sex workers, in a culture where prostitution is otherwise forbidden.[82] Sunni Muslims, who make up the majority of Muslims worldwide, believe the practice of fixed-term marriage was abrogated and ultimately forbidden by either Muhammad, or one of his successors, Umar. Sunnis regard prostitution as sinful and forbidden. Some writers have argued that mut'ah[83] and nikah misyar[84] approximate prostitution. Julie Parshall writes that mut'ah is legalised prostitution which has been sanctioned by the Twelver Shia authorities. She quotes the Oxford Encyclopedia of Modern Islamic World to differentiate between marriage (nikah) and mut'ah, and states that while nikah is for procreation, mut'ah is just for sexual gratification.[85] According to Zeyno Baran, this kind of temporary marriage provides Shi'ite men with a religiously sanctioned equivalent to prostitution.[86] According to Elena Andreeva's observation published in 2007, Russian travellers to Iran consider mut'ah to be "legalized profligacy" which is indistinguishable from prostitution.[87] Religious supporters of mut'ah argue that temporary marriage is different from prostitution for a couple of reasons, including the necessity of iddah in case the couple have sexual intercourse. It means that if a woman marries a man in this way and has sex, she has to wait for a number of months before marrying again and therefore, a woman cannot marry more than 3 or 4 times in a year.[88][89][90][91][92][93]

According to Dervish Ismail Agha, in the Dellâkname-i Dilküşâ, the Ottoman archives,[94][95] in the hammams, the masseurs were traditionally young men, who helped wash clients by soaping and scrubbing their bodies. They also worked as sex workers.[96] The Ottoman texts describe who they were, their prices, how many times they could bring their customers to orgasm, and the details of their sexual practices.

East Asia

[edit]

In the early 17th century, there was widespread male and female prostitution throughout the cities of Kyoto, Edo, and Osaka, Japan. Oiran were courtesans in Japan during the Edo period. The oiran were considered a type of yūjo (遊女)(ja) "woman of pleasure" or prostitute. Among the oiran, the tayū (太夫) was considered the highest rank of courtesan available only to the wealthiest and highest ranking men. To entertain their clients, oiran practiced the arts of dance, music, poetry, and calligraphy as well as sexual services, and an educated wit was considered essential for sophisticated conversation. Many became celebrities of their times outside the pleasure districts. Their art and fashions often set trends among wealthy women. The last recorded oiran was in 1761. Although illegal in modern Japan, the definition of prostitution does not extend to a "private agreement" reached between a woman and a man in a brothel. Yoshiwara has a large number of soaplands where women wash men's bodies. They began when explicit prostitution in Japan became illegal, and were originally known as toruko-buro ("Turkish bath").

Japanese prostitutes were held in high regard by European travelling men in the 19th century. A British army officer reported that Japanese women were the best prostitutes in the world, for their attractiveness, cleanliness, and intelligence.[97]

South Asia

[edit]The Mahabharata and the Matsya Purana mention fictitious accounts of the origin of Prostitution. Although, Later Vedic texts tacitly, as well as overtly, mention Prostitutes, it is in the Buddhist literature that professional prostitutes are noticed.[98] A tawaif was a courtesan who catered to the nobility of the Indian subcontinent, particularly during the era of the Mughal Empire. These courtesans danced, sang, recited poetry and entertained their suitors at mehfils. Like the geisha tradition in Japan, their main purpose was to professionally entertain their guests, and while sex was often incidental, it was not assured contractually. High-class or the most popular tawaifs could often pick and choose between the best of their suitors. They contributed to music, dance, theatre, film, and the Urdu literary tradition.[99]

During the East India Company's rule in India from 1757 until 1857, it was common for European soldiers serving in the presidency armies to solicit the services of Indian prostitutes, and they frequently paid visits to local nautch dancers for purposes of a sexual nature.[100] Prostitutes from Japan were also popular. Asian prostitutes were held in higher regard than prostitutes from Europe because they came from higher social backgrounds and were regarded as cleaner, more attractive and entertaining than prostitutes back in Europe.[97]

In the 21st century, Afghans revived a method of prostituting young boys which is referred to as "bacha bazi".[101]

India's devadasi girls are forced by their poor families to dedicate themselves to the Hindu goddess Renuka. The BBC wrote in 2007 that devadasis are "sanctified prostitutes".[102]

Americas

[edit]

In Latin America and the Caribbean sex worker movements date back to the late 19th century in Havana, Cuba. A catalyst in the movement being a newspaper published by Havana sex workers. This publication went by the name La Cebolla, created by Las Horizontales.[103]

During this period, prostitution was also very prominent in the Barbary Coast, San Francisco as the population was mainly men, due to the influx from the Gold Rush.[104] One of the more successful madams was Belle Cora, who inadvertently got involved in a scandal involving her husband, Charles Cora, shooting US Marshal William H. Richardson.[105] This led to the rise of new statutes against prostitution, gambling and other activities seen as "immoral".[104]

Originally, prostitution was widely legal in the United States. Prostitution was made illegal in almost all states between 1910 and 1915 largely due to the influence of the Woman's Christian Temperance Union.[106][107]

On the other hand, prostitution generated much national revenue in South Korea, hence the military government encouraged prostitution for the U.S. military.[108][109]

Beginning in the late 1980s, many states in the US increased the penalties for prostitution in cases where the prostitute is knowingly HIV-positive. Penalties for felony prostitution vary, with maximum sentences of typically 10 to 15 years in prison.

Recently, a study published in UNED Research Journal examined Costa Rican college students’ perceptions of prostitution through interviews with sex workers, NGO leaders, and 200 students. Results showed realistic views: students saw sex work as a mix of need and choice, and clients as diverse and often regular. Findings aligned with previous research in Spain.[110]

Sex tourism emerged in the late 20th century as a controversial aspect of Western tourism and globalization.

Historically, and currently, church prostitutes exist, and the practice may be legal or illegal, depending on the country, state or province.[111][110]

Economics

[edit]Prostitutes' salaries and payments fluctuate according to the economic conditions of their respective countries. Prostitutes who usually have foreign clients, such as business travelers, depend on good foreign economic conditions.[112] Payment may vary according to regulations made by pimps, brothel keepers, madams, and procurers, who usually take a slice out of a prostitute's income.[113] Prices may further depend on demand; popular, high-end prostitutes can earn significant amounts of money (upwards of $5,000 per client),[114] and virgins may receive even higher payments.

Law

[edit]This section needs additional citations for verification. (March 2020) |

The position of prostitution and the law varies widely worldwide,[115] reflecting differing opinions on victimhood and exploitation, inequality, gender roles, gender equality, ethics and morality, freedom of choice, historical social norms, and social costs and benefits.

Legal themes tend to address four types of issues: victimhood (including potential victimhood), ethics and morality, freedom of choice, and general benefit or harm to society (including harm arising indirectly from matters connected to prostitution).

Prostitution may be considered a form of exploitation (e.g., Sweden, Norway, Iceland, where it is illegal to buy sexual services, but not to sell them—the client commits a crime, but not the prostitute), a legitimate occupation (e.g., Netherlands, Germany, where prostitution is regulated as a profession) or a crime (e.g., many Muslim countries, where the prostitutes face severe penalties).

The legal status of prostitution varies from country to country, from being legal and considered a profession to being punishable by death.[116] Some jurisdictions outlaw the act of prostitution (the exchange of sexual services for money); other countries do not prohibit prostitution itself, but ban the activities typically associated with it (soliciting in a public place, operating a brothel, pimping, etc.), making it difficult to engage in prostitution without breaking any law; and in a few countries prostitution is legal and regulated.

In some countries, there is controversy regarding the laws applicable to sex work. For instance, the legal stance of punishing pimping while keeping sex work legal but "underground" and risky is often denounced as hypocritical; opponents suggest either going the full abolition route and criminalize clients or making sex work a regulated business.

Other groups, often with religious backgrounds, focus on offering women a way out of the world of prostitution while not taking a position on the legal question.

Prostitution is a significant issue in feminist thought and activism. Many feminists are opposed to prostitution, which they see as a form of exploitation of women and male dominance over women, and as a practice that is the result of the existing patriarchal societal order. These feminists argue that prostitution has a very negative effect, both on the prostitutes themselves and on society as a whole, as it reinforces stereotypical views about women, who are seen as sex objects which can be used and abused by men. Other feminists hold that prostitution can be a valid choice for the women who choose to engage in it; in this view, prostitution must be differentiated from forced prostitution, and feminists should support sex worker activism against abuses by both the sex industry and the legal system.

Decriminalization

[edit]Decriminalization views prostitution as labor like any other and that the sex industry premises should not be subject to any special regulation or laws. This is the current situation in New Zealand; the laws against operating a brothel, pimping, and street prostitution are struck down, but prostitution is hardly regulated at all. Proponents of this view often cite instances of government regulation under legalization that they consider intrusive, demeaning, or violent, but feel that criminalization adversely affects sex workers.[117] Amnesty International is one of the notable groups calling for the decriminalization of prostitution.[118][15][119]

Many countries have sex worker advocacy groups that lobby against criminalization and discrimination of prostitutes. These groups generally oppose Nevada-style regulation and oversight, stating that prostitution should be treated like other professions. In the United States of America, one such group is COYOTE (an abbreviation for "Call Off Your Old Tired Ethics") and another is the North American Task Force on Prostitution.[120] In Australia the lead sex worker rights organisation is Scarlet Alliance.[121] International prostitutes' rights organizations include the International Committee for Prostitutes' Rights and the Network of Sex Work Projects.[122]

Legalization

[edit]Some view prostitution as something to be legalized and regulated: prostitution may be considered a legitimate business; prostitution and the employment of prostitutes are legal, but regulated. This is the current situation in the Netherlands, Germany,[123] most of Australia and parts of Nevada (see Prostitution in Nevada). The degree of regulation varies very much; for example, in the Netherlands, prostitutes are not required to undergo mandatory health checks (see Prostitution in the Netherlands), while in Nevada, the regulations are very strict (see Prostitution in Nevada). Because prostitution is considered criminal in many jurisdictions, its substantial revenues are not contributing to the tax revenues of the state, and its workers are not routinely screened for sexually transmitted infections which is dangerous in cultures favouring unprotected sex and leads to significant expenditure in the health services. According to the 1992 Estimates of the costs of crime in Australia report, there was an "estimated $96 million loss of taxation revenue from undeclared earnings of prostitution".[124]

Abolitionism

[edit]In abolitionism, prostitution itself is not prohibited, but most associated activities are illegal, in an attempt to make it more difficult to engage in prostitution, prostitution is heavily discouraged and seen as a social problem. Prostitution (the exchange of sexual services for money) is legal, but the surrounding activities such as public solicitation, operating a brothel and other forms of pimping are prohibited. This is to some extent the current situation in Great Britain, where prostitution is considered "both a public nuisance and sexual offence", and Italy among others.[125]

Neo-abolitionism

[edit]Neo-abolitionism view prostitution as inherently abusive and a form of violence against women.[126] Prostitutes are not prosecuted, but their clients and pimps are. In 1999, after lobbying by a coalition of feminists and Christians, Sweden criminalized the buying, not the selling, of sex and neo-abolitionism has come to also be known as the "Nordic model". It has since become law in France, Norway and Iceland (in Norway the law is even more strict, forbidding also having sex with a prostitute abroad).[127] Exxpose, a Dutch group led by evangelical students gathered 40,000 signatures for a petition for the Dutch parliament to adopt the Swedish model but were unsuccessful.[128] Advocates feel that legalizing and regulating prostitution creates a parallel illegal prostitution industry, and fails to dissociate the legal part of the sex trade from crime.[129][130][131][132]

In 1949, the UN General Assembly adopted a convention stating that "prostitution and the accompanying evil of the traffic in persons for the purpose of prostitution are incompatible with the dignity and worth of the human person",[133] requiring all signing parties to punish pimps and brothel owners and operators and to abolish all special treatment or registration of prostitutes. As of January 2009, the convention was ratified by 95 member nations including France, Spain, Italy, Denmark, and not ratified by another 97 member nations including Germany, the Netherlands, the United Kingdom, and the United States.

In February 2014, the members of the European Parliament voted in a non-binding resolution, (adopted by 343 votes to 139; with 105 abstentions), in favor of the 'Swedish Model' of criminalizing the buying, but not the selling of sex.[134]

Prohibitionism

[edit]In prohibitionism, both prostitutes and clients are criminalized and are seen as immoral, they are considered criminals. This is the prevailing attitude nearly everywhere in the United States, with a few exceptions in some rural Nevada counties (see Prostitution in Nevada)

Prostitution, often when it is illegal, is used in extortion and blackmail, which always involves extortion, where the extortionist threatens to reveal information about a victim or their family members that is potentially embarrassing, socially damaging, or incriminating unless a demand for money, property, or services is met. The subject of the extortion may be manipulated into or voluntarily solicit the use of prostitution which is then later used to extort money or for profit otherwise. The film The Godfather Part II famously depicts the role of Senator Geary who is implicated in the use of prostitution in order to gain his compliance on political issues.[135]

Survival sex

[edit]Survival sex is when the prostitute is driven to prostitution by a need for basic necessities such as food or shelter.

Drug addicts

[edit]Drug addiction is associated with increased odds of survival sex work.[136]

Homeless

[edit]Researchers estimate that of homeless youth in North America, one in three has engaged in survival sex. In one study of homeless youth in Los Angeles, about one-third of females and half of males said they had engaged in survival sex.[137][138][139]

Refugees

[edit]Survival sex is common in refugee camps. In internally displaced persons camps in northern Uganda, where 1.4 million civilians have been displaced by conflict between Ugandan government forces and the militant Lord's Resistance Army, Human Rights Watch reported in 2005 that displaced women and girls were engaging in survival sex with other camp residents, local defense personnel, and Ugandan government soldiers.[140]

Illegal migrants

[edit]A difficulty facing migrant prostitutes in many developed countries is the illegal residence status of some of these women. They face potential deportation, and so do not have recourse to the law. This increases their fear of reporting violence they may suffer, due to their fear of being deported, as well as fear of reprisal from human traffickers.[141][142] The immigration status of the persons who sell sexual services is—particularly in Western Europe—a controversial and highly debated political issue. Currently, in most of these countries, most prostitutes are immigrants, mainly from Eastern and Central Europe; in Spain and Italy 90% of prostitutes are estimated to be migrants, in Austria 78%, in Switzerland 75%, in Greece 73%, in Norway 70% (according to a 2009 TAMPEP report, Sex Work in Europe-A mapping of the prostitution scene in 25 European countries).[143] An article in Le Monde diplomatique in 1997 stated that 80% of prostitutes in Amsterdam were foreigners and 70% had no immigration papers.[144]

Caste prostitutes

[edit]

Castes are largely hereditary social classes often emerging around certain professions. Lower castes are associated with professions considered "unclean", which has often included prostitution. In pre-modern Korea, some women from the lower caste Cheonmin, known as Kisaeng, were trained to provide entertainment, conversation, and sexual services to men of the upper class.[145] In South Asia, castes associated with prostitution today include the Bedias,[146] the Perna caste,[147] the Banchhada,[148] the Nat caste and, in Nepal, the Badi people.[149][150]

Elderly

[edit]Prostitution among the elderly is a phenomenon reported in South Korea where elderly women, called Bacchus Ladies, turn to prostitution out of necessity. They are called that because many also sell the popular Bacchus energy drink to make ends meet. State pensions of about ₩200,000 (US$168) provide a basic income but are often not enough to cover the rising medical bills of old age. It first arose after the 1997 Asian financial crisis when it became more difficult for children and grandchildren to support their elders. Clients tend to be more senior. The use of erection-inducing injections with reused needles has contributed to the spread of sexually transmitted infections.[151][152]

Forced prostitution

[edit]

Sex trafficking is defined as using coercion or force to transport an unwilling person into prostitution or other sexual exploitation.[154] The United Nations stated in 2009 that sex trafficking is the most commonly identified form of human trafficking and estimates that about 79% of human trafficking reported is for prostitution (although the study notes that this may be the result of statistical bias and that sex trafficking tends to receive the most attention and be the most visible).[155] Sex trafficking has been described by Kul Gautum, deputy executive director of UNICEF, as "the largest slave trade in history."[156] It is also the fastest growing criminal industry, predicted to outgrow drug trafficking.[157][158][159] While there may be a higher number of people involved in slavery today than at any time in history, the proportion of the population is probably the smallest in history.[160][161] "Annually, according to U.S. Government-sponsored research completed in 2006, approximately 800,000 people are trafficked across national borders, which does not include millions trafficked within their own countries. Approximately 80 percent of transnational victims are women and girls and up to 50 percent are minors", estimated the US Department of State in a 2008 study, in reference to the number of people estimated to be victims of all forms of human trafficking.[162] Due in part to the illegal and underground nature of sex trafficking, the actual extent of women and children forced into prostitution is unknown. A statistical analysis of various measures of trafficking found that the legal status of prostitution did not have a significant impact on trafficking.[13] Globally, forced labour generates an estimated $31 billion, about half of it in the industrialized world and around one-tenth in transitional countries, according to the International Labour Organization (ILO) in a report on forced labour ("A global alliance against forced labour", ILO, 11 May 2005).[163] International trafficking of people has been heavily facilitated by communication technologies.[164] The most common destinations for victims of human trafficking are Thailand, Japan, Israel, Belgium, the Netherlands, Germany, Italy, Turkey, and the US, according to a report by the UNODC (UN Office on Drugs and Crime).[165] Major sources of trafficked persons include Thailand, China, Nigeria, Albania, Bulgaria, Belarus, Moldova, and Ukraine.[165]

The legalization of buying sex is associated with higher human trafficking inflows than countries where it is prohibited. The type of legalization, such as allowing third-party involvement (i.e, “pimps”), is not shown to make a difference in the effect of sex trafficking inflows.[166]

Use of children

[edit]Regarding the prostitution of children the laws on prostitution as well as those on sex with a child apply. If prostitution, in general, is legal there is usually a minimum age requirement for legal prostitution that is higher than the general age of consent (see above for some examples). In the early 1990s, some countries, mainly in Latin America, did not single out patronage of child prostitution as a separate crime.[167] According to Steinman (2002), by the early 2000s, several such countries had passed laws against child prostitution, yet they were weakly enforced, and pimps continued to profit from the exploitation of minors in Latin America.[168]

Children are sold into the global sex trade every year. Often they are kidnapped or orphaned, and sometimes they are sold by their own families. According to the International Labour Organization, the occurrence is especially common in places such as Thailand, the Philippines, Sri Lanka, Vietnam, Cambodia, Nepal, and India.[169]

In India, the federal police say that around 1.2 million children are believed to be involved in prostitution.[170] A CBI statement said that studies and surveys sponsored by the ministry of women and child development estimated that about 40% of all India's prostitutes are children.[170]

Children are often medicated to make them appear more mature. In Bangladesh, child prostitutes are known to take the drug Oradexon, also known as dexamethasone. This over-the-counter steroid, usually used by farmers to fatten cattle, makes child prostitutes look larger and older. Charities say that 90% of prostitutes in the country's legalized brothels use the drug. According to social activists, the steroid can cause diabetes, high blood pressure and is highly addictive.[171][172][173] In India, some girls are injected with oxytocin to make their breasts grow faster.[174]

Thailand's Health System Research Institute reported that children in prostitution make up 40% of prostitutes in Thailand.[175]

Some adults travel to other countries to have access to sex with children, which is unavailable in their home country. Cambodia has become a notorious destination for sex with children.[176][177] Thailand is also a destination for child sex tourism.[177][178] Several western countries have recently enacted laws with extraterritorial reach, punishing citizens who engage in sex with minors in other countries. As the crime usually goes undiscovered, these laws are rarely enforced.[179][180][181]

Sex care for the disabled

[edit]Prostitution is seen by some people with disabilities, or some people with neurological differences – such as some on the autism spectrum – to be an effective way to have sexual experiences, find intimacy or receive human affection that may be difficult for them to come by via traditional means and that may be lacking in their lives.[182][183] A poll by The Observer in 2008 indicated that 70% of Britons would not consider having sex with someone who has a physical disability.[182] Some people that have disabilities are referred to prostitutes by friends or family, such as a parent or guardian, carers, or support workers.[184] In 2021, a UK judge ruled that council care workers can help disabled people meet prostitutes without breaking the law.[185] Prostitutes that cater to people with disabilities have argued that people with disabilities have the same needs and desires as everyone else.[184]

In some countries such as Denmark and the Netherlands access to sex workers for those with disabilities is funded by the state on the basis that sexuality is a human right and leads to improved well-being for people with disabilities.[186][187]

Procurement methods

[edit]In countries where prostitution is legal, advertising it may be legal (as in the Netherlands) or illegal (as in India). Covert advertising for prostitution can take a number of forms:

- by cards in newsagents' windows

- by cards placed in public telephone enclosures: so-called tart cards

- by euphemistic advertisements in regular magazines and newspapers (for instance, talking of "massages" or "relaxation")

- in specialist contact magazines

- via the Internet

In the United States, massage parlors serving as a cover for prostitution may advertise "full service", a euphemism for coitus.[188]

In Las Vegas, prostitution is often promoted overtly on the Las Vegas Strip by third party workers distributing risque flyers with the pictures and phone numbers of escorts (despite the fact that prostitution is illegal in Las Vegas and Clark County, see Prostitution in Nevada).

The way in which prostitutes advertise their presence varies widely. Some remain in apartments that have hints or clues outside such as posters with "model" written on them to lure potential customers inside. Others advertise by putting numbers or locations in phoneboxes or in online or newspaper ads. In more sexually permissive societies, prostitutes can advertise in public view, such as through display windows. In sexually restrictive societies it may occur through word-of-mouth and other means.[189]

Street

[edit]In street prostitution, the prostitute solicits customers while waiting at street corners, sometimes called "the track" by pimps and prostitutes alike. They usually dress in skimpy, provocative clothing, regardless of the weather. In American usage, street prostitutes are often called "streetwalkers" while their customers are referred to as "tricks" or "johns". Servicing the customers is described as "turning tricks". The sex is usually performed in the customer's car, in a nearby alley, or in a rented room. Motels and hotels that accommodate prostitutes commonly rent rooms by half or full hour.

In Russia and other countries of the former USSR, prostitution takes the form of an open-air market. One prostitute stands by a roadside and directs cars to a so-called "tochka" (usually located in alleyways or carparks), where lines of women are paraded for customers in front of their car headlights. The client selects a prostitute, whom he takes away in his car. Prevalent in the late 1990s, this type of service has been steadily declining in recent years.

A "lot lizard" is a commonly encountered special case of street prostitution.[190] Lot lizards mainly serve those in the trucking industry at truck stops and stopping centers. Prostitutes will often proposition truckers using a CB radio from a vehicle parked in the non-commercial section of a truck stop parking lot, communicating through codes based on commercial driving slang, then join the driver in his truck.

Window prostitution

[edit]

Window prostitution is a form of prostitution that is fairly common in the Netherlands and surrounding countries.[191] The prostitute rents a window plus workspace off a window operator for a certain period of time, often per day or part of a day.[192][193][194] The prostitute is also independent and recruits her own customers and also negotiates the price and the services to be provided.[192][193][194]

Brothels

[edit]

Brothels are establishments specifically dedicated to prostitution, often confined to special red-light districts in big cities. Other names for brothels include bordello, whorehouse, cathouse, knocking shop, and general houses. Prostitution also occurs in some massage parlours, and in Asian countries in some barber shops where sexual services may be offered as a secondary function of the premises.

Escorts

[edit]

Escort services may be distinguished from prostitution or other forms of prostitution in that sexual activities are often not explicitly advertised as necessarily included in these services; rather, payment is often noted as being for an escort's time and companionship only, although there is often an implicit assumption that sexual activities are expected.

In escort prostitution, the act takes place at the customer's residence or hotel room (referred to as out-call), or at the escort's residence, or in a hotel room rented for the occasion by the escort (called in-call). The prostitute may be independent or working under the auspices of an escort agency. Services may be advertised over the Internet, in regional publications, or in local telephone listings.

Use of the Internet by prostitutes and customers is common.[196] A prostitute may use adult boards or create a website of their own with contact details, such as email addresses. Adult contact sites, chats, and online communities are also used. This, in turn, has brought increased scrutiny from law enforcement, public officials, and activist groups toward online prostitution. In 2009, Craigslist came under fire for its role in facilitating online prostitution, and was sued by some 40 US state attorneys general, local prosecutors, and law enforcement officials.

Reviews of the services of individual prostitutes can often be found at various escort review boards worldwide. These online forums are used to trade information between potential clients, and also by prostitutes to advertise the various services available. Sex workers, in turn, often use online forums of their own to exchange information on clients, particularly to warn others about dangerous clients.

Sex tourism

[edit]Sex tourism is travel for sexual intercourse with prostitutes or to engage in other sexual activity. The World Tourism Organization, a specialized agency of the United Nations, defines sex tourism as "trips organized from within the tourism sector, or from outside this sector but using its structures and networks, with the primary purpose of effecting a commercial sexual relationship by the tourist with residents at the destination".[197]

As opposed to regular sex tourism, which is often legal, a tourist who has sex with a child prostitute will usually be committing a crime in the host country, under the laws of his own country (notwithstanding him being outside of it) and against international law. Child sex tourism (CST) is defined as travel to a foreign country for the purpose of engaging in commercially facilitated child sexual abuse.[198] Thailand, Cambodia, India, Brazil, and Mexico have been identified as leading hotspots of child sexual exploitation.[199]

Virtual sex

[edit]Virtual sex, that is, sexual acts conveyed by messages rather than physically, is also the subject of commercial transactions. Commercial phone sex services have been available for decades. The advent of the Internet has made other forms of virtual sex available for money, including computer-mediated cybersex, in which sexual services are provided in text form by way of chat rooms or instant messaging, or audiovisually through a webcam (see camgirl).

Organization

[edit]Labor unions

[edit]The International Union of Sex Workers is a United Kingdom-based labor union for sex workers and is affiliated with the general trade union, GMB.

Communities

[edit]Daulatdia, sometimes called the world's largest brothel, is an entire village in Bangladesh dedicated to prostitution. Many were born there, being the children of prostitutes.[200] Another similar community in Bangladesh is Kandapara.[201] The village of Vadia, India, is known locally as the village of prostitutes, where unmarried women are involved in prostitution. Mass weddings for children of prostitutes in the village are held to protect them from being pushed into prostitution.[202]

Prevalence

[edit]

According to the paper "Estimating the prevalence and career longevity of prostitute women",[203] the number of full-time equivalent prostitutes in a typical area in the United States (Colorado Springs, CO, during 1970–1988) is estimated at 23 per 100,000 population (0.023%), of which some 4% were under 18. The length of these prostitutes' working careers was estimated at a mean of 5 years. According to a 2012 report by Fondation Scelles there are between 40 and 42 million prostitutes in the world.[204]

In 2003, it was estimated that in Amsterdam, one woman in 35 was working as a prostitute, compared to one in 300 in London.[205]

The number of men who have used a prostitute at least once varies widely from country to country, from an estimated low of between 7%[206] and 8.8%[207] in the United Kingdom, to a high of between 59% and 80% in Cambodia.[208] A study conducted by ProCon – a nonpartisan nonprofit organization – estimated the percentage of men who had paid for sex at least once in their lives, and found the highest rates in Cambodia (between 59 and 80% of men had paid for sex at least once) and Thailand (an estimated 75%), followed by Italy (16.7–45%), Spain (27–39%), Japan (37%), the Netherlands (13.5–21.6%), the United States (15.0–20.0%), and China (6.4-20%).[208] Nations with higher rates of prostitution clients display much more positive attitudes towards commercial sex.[208] In some countries, such as Cambodia and Thailand, sex with prostitutes is considered commonplace and men who do not engage in commercial sex may be considered unusual by their peers.[208] In Thailand, it has been reported that about 75% of men have visited a prostitute at least once in their lifetimes. In Cambodia, that figure is 59% to 80%.[208]

In the United States, a 2004 TNS poll reported 15% of all men admitted to having paid for sex at least once in their life.[209] However, a paper entitled "Prostitution and the sex discrepancy in reported number of sexual partners" concluded that men's self-reporting of prostitutes as sexual partners provides a serious underestimate.[210]

In Australia, a survey conducted in the early 2000s showed that 15.6% of men aged 16–59 reported paying for sex at least once in their life, and 1.9% had done so in the past year.[211]

Reports disagree on whether prostitution levels are growing or declining in developed countries. Some studies indicate that the percentage of men engaging in commercial sex in the United States has declined significantly in recent decades: in 1964, an estimated 69–80% of men had paid for sex at least once.[208] Some have suggested that prostitution levels have fallen in sexually liberal countries, most likely because of the increased availability of non-commercial, non-marital sex[212] or, for example in Sweden, because of stricter legal penalties.[213] Other reports suggest a growth in prostitution levels, for example in the US,[214] where again, sexual liberalisation is suggested as the cause. As Norma Ramos, executive director of the Coalition Against Trafficking in Women says "The more the commercial sex industry normalizes this behavior, the more of this behavior you get".[215]

Prostitutes have long plied their trades to the military in many cultures. For example, the British naval port of Portsmouth had a flourishing local sex industry in the 19th century, and until the early 1990s there were large red-light districts near American military bases in the Philippines. The notorious Patpong entertainment district in Bangkok, Thailand, started as an R&R location for US troops serving in the Vietnam War in the early 1970s. Washington D.C. itself had Murder Bay which attracted the military of the Civil War.

Violence against prostitutes

[edit]Street prostitutes are at higher risk of violent crime than brothel prostitutes and bar prostitutes.[216][217]

In the United States, the homicide rate for female prostitutes was estimated to be 204 per 100,000.[218] There are substantial differences in rates of victimization between street prostitutes and indoor prostitutes who work as escorts, call girls, or in brothels and massage parlors.[219][220] Violence against male prostitutes is less common.[221]

The call to decriminalize selling sex is in part to reduce harm and violence. Under criminalization, prostitutes become more vulnerable to be victims of crimes, even by serial killers, because those committing crimes know that prostitutes would be less likely to report such crimes to the police as they would risk arrest. Additionally, this puts prostitutes at risk of violence by police as police are able to extort prostitutes by threatening arrest. The ACLU, Human Rights Watch and Amnesty International argue that, in addition to decriminalize selling sex as in the Nordic model, decriminalizing buying sex makes it more safer for prostitutes.[222][223][224]

Medical situation

[edit]In some places, prostitution may be associated with the spread of sexually transmitted infections (STIs). Lack of condom use among prostitutes and their clients has been cited as a factor in the spread of HIV in Asia: "One of the main reasons for the rapid spread of HIV in Asian countries is the massive transmission among sex workers and clients".[225] As a result, prevention campaigns aimed at increasing condom use by sex workers have been attributed to play a major role in restricting the spread of HIV.[226]

One of the sources for the spread of HIV in Africa is prostitution, with one study finding that encounters with prostitutes produced 84% of new HIV infections in adult males in Accra, Ghana.[227] The spread of HIV from urban settings to rural areas in Africa has been attributed to the mobility of farmers who visit sex workers in cities, for example in Ethiopia.[228] Some studies of prostitution in urban settings in developing countries, such as Kenya, have stated that prostitution acts as a reservoir of STIs within the general population.[229]

Typical responses to the problem are:

- banning prostitution completely

- introducing a system of registration for prostitutes that mandates health checks and other public health measures

- educating prostitutes and their clients to encourage the use of barrier contraception and greater interaction with health care

Some think that the first two measures are counter-productive. Banning prostitution tends to drive it underground, making safe sex promotion, treatment, and monitoring more difficult. Registering prostitutes makes the state complicit in prostitution and does not address the health risks of unregistered prostitutes. Both of the last two measures can be viewed as harm reduction policies.

In countries and areas where safer sex precautions are either unavailable or not practiced for cultural reasons, prostitution is an active disease vector for all STIs, including HIV/AIDS, but the encouragement of safer sex practices, combined with regular testing for sexually transmitted infections, has been very successful when applied consistently. As an example, Thailand's condom program has been largely responsible for the country's progress against the HIV epidemic.[225] It has been estimated that successful implementation of safe sex practices in India "would drive the [HIV] epidemic to extinction" while similar measures could achieve a 50% reduction in Botswana.[230] In 2009, UN Secretary-General Ban Ki-moon urged all countries to remove bans on prostitution and homosexual sex, because "such laws constitute major barriers to reaching key populations with HIV services". In 2012, the Global Commission on HIV and the Law, which was convened by Ban Ki-moon, and which is an independent body, was established at the request of the UNAIDS, and supported by a Secretariat based at the UNDP,[231] reached the same conclusions, also recommending decriminalization of brothels and procuring.[232][233][234] Nevertheless, the report states that: "The content, analysis, opinions and policy recommendations contained in this publication do not necessarily reflect the views of the United Nations Development Programme."[231]

The COVID-19 pandemic has had an impact on sex work. During the COVID-19 pandemic, contact professions (which includes prostitution, amongst others) had been banned (temporarily) in some countries. This has resulted in a local reduction of prostitution.[235]

Psychological issues

[edit]De Marneffe (2009) argued that there are psychological issues that prostitutes face from certain experiences and through the duration or repetition. Some go through experiences that may result "in lasting feelings of worthlessness, shame, and self-hatred". De Marneffe further argued that this may affect the prostitute's ability to perform sexual acts for the purpose of building a trusting intimate relationship, which may be important for their partner. The lack of a healthy relationship can lead to higher divorce rates and can influence unhealthy relationship to their children, influencing their future relationships.[236]

See also

[edit]- Brothel

- Common prostitute

- Drugs and prostitution

- Empathy and Prostitution

- Fallen woman

- Index of prostitute articles

- International Day of No Prostitution

- International Day to End Violence Against Sex Workers

- International Whores' Day

- Lady in Red

- List of prostitutes and courtesans

- Mann Act (White-Slave Traffic Act)

- Prostitution among animals

- Prostitution statistics by country

- Recreation and Amusement Association

- Red light violations under the SCS

- Revolting Prostitutes

- Sanky-panky

- Street prostitute

- Transactional sex

- Treating (social activity)

- A Vindication of the Rights of Whores

- Impact of prostitution on mental health

References

[edit]Notes

- ^ "Prostitution – Definition and More from the Free Merriam-Webster Dictionary". Merriam-Webster. Retrieved 19 September 2013.

- ^ "Prostitution Law & Legal Definition". US Legal. Retrieved 19 March 2013.

- ^ "What counts as prostitution?" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 13 May 2021. Retrieved 13 May 2021.

- ^ Flowers 1998, p. 5.

- ^ Forrest Wickman (6 March 2012). "Rush Limbaugh calls Sandra Fluke a "prostitute": Is prostitution really the world's oldest profession?". Slate. Retrieved 4 February 2016.

- ^ "There Are 42 Million Prostitutes In The World, And Here's Where They Live". Business Insider. Retrieved 15 September 2022.

- ^ "There The prostitution statistics you have to know". 6 April 2015. Retrieved 15 September 2022.

- ^ Gus Lubin (17 January 2012). "There Are 42 Million Prostitutes in the World, And Here's Where They Live". Business Insider. Retrieved 14 December 2015.

- ^ "Prostitution Market Value". 25 March 2010. Archived from the original on 22 May 2010. Retrieved 22 May 2010. This Business Insider article is citing this report (https://www.fondationscelles.org/pdf/current-assessment-of-the-state-of-prostitution-2013.pdf) by Fondation Scelles which is an anti human trafficking organization

- ^ Meghan Murphy (12 December 2013). "Prostitution by Any Other Name Is Still Exploitation". VICE. Retrieved 4 February 2016.

- ^ Malika Saada Saar (29 July 2015). "The myth of child prostitution". CNN. Retrieved 4 February 2016.

- ^ Carol Tan (2 January 2014). "Does legalized prostitution increase human trafficking?". Journalist's Resource. Retrieved 4 February 2016.

- ^ a b Cho, Seo-Young (2015). "Modeling for Determinants of Human Trafficking: An Empirical Analysis". Social Inclusion. 3 (1): 2–21. doi:10.17645/si.v3i1.125. Retrieved 5 October 2018.

- ^ (eISB), electronic Irish Statute Book. "Amendment of Act of 1993". www.irishstatutebook.ie. Retrieved 14 May 2017.

- ^ a b Q&A: policy to protect the human rights of sex workers. Amnesty International. Retrieved 23 November 2017.

- ^ Perkins & Lovejoy 2007, pp. 2–3.

- ^ "prostitute". Online Etymology Dictionary. Retrieved 26 June 2012.

- ^ "Perseus Digital Library". Perseus.tufts.edu. Retrieved 26 June 2012.

- ^ "sex worker". Merriam-webster.com. 13 August 2010. Retrieved 26 June 2012.

- ^ Weitzer, Ronald (2009). "Sociology of Sex Work". Annual Review of Sociology. 35: 213–234. doi:10.1146/annurev-soc-070308-120025. ISSN 0360-0572. S2CID 145372267.

- ^ Benoit, C.; Jansson, S. M.; Smith, M.; Flagg, J. (2018). "Prostitution stigma and its effect on the working conditions, personal lives, and health of sex workers". Journal of Sex Research. 55 (4–5): 457–471. doi:10.1080/00224499.2017.1393652. PMID 29148837. S2CID 4008671.

- ^ "AmericanHeritage.com / History Now". 21 May 2006. Archived from the original on 21 May 2006. Retrieved 22 December 2014.

- ^ Horning, A.; Thomas, C.; Marcus; Sriken, J. (2019). "Risky business: Harlem pimps' work decisions and economic returns". Deviant Behavior. 41 (2): 160–185. doi:10.1080/01639625.2018.1556863. S2CID 150273170.

- ^ "Adult Industry Terms and Acronyms". Forum.myredbook.com. Archived from the original on 9 February 2010. Retrieved 23 May 2010.

- ^ Ling, Justin (4 March 2014). "Opposition parties shy away from sex-work debate". Xtra. Retrieved 26 August 2018.

- ^ "7 Things You Learn As A Cop Pretending To Be A Hooker". Cracked.com. 11 October 2015.

- ^ Honwana, Alcinda. "Changing Patterns of Intimacy among Young People in Africa." African Dynamics in a Multipolar World (2013): 29-47.

- ^ "prostitution – Dictionary definition and pronunciation – Yahoo! Education". Education.yahoo.com. Archived from the original on 23 March 2010. Retrieved 23 May 2010.

- ^ a b c Riabova, Tatiana and Riabova, Oleg (2015) "Gayromaidan" in Fedor, Julie; Portnov, Andriy; and Umland, Andraes (eds.) Journal of Soviet and Post-Soviet Politics and Society: Sociographic Essays on the Post-Soviet Infrastructure for Alternative Healing Practices, Volume 1, Issue 1 Columbia University Press. p.105 Accessed: 14 March 2017

- ^ Trotsky, Leon (1921). "Terrorism and Communism: Chapter 7, The Working Class and Its Soviet Policy". Marxists.org. Retrieved 14 March 2017.

- ^ Trotsky, Leon (September 1938). "New War Flows from Versailles Banditry". Marxists.org. Retrieved 14 March 2017.

- ^ Gerdy, Tom (29 February 2016). "Winner or Just Another Political Prostitute?". The Huffington Post. Retrieved 14 March 2017.

- ^ Pheterson, Gail (1993). "The Whore Stigma: Female Dishonor and Male Unworthiness". Social Text (37): 39–64. doi:10.2307/466259. JSTOR 466259.

- ^ Beard, Mary; Henderson, John (November 1997). "With This Body I Thee Worship: Sacred Prostitution in Antiquity". Gender & History. 9 (3): 480–503. doi:10.1111/1468-0424.00072. ISSN 0953-5233. S2CID 145105205.

- ^ Budin, Stephanie Lynn (14 January 2008). The Myth of Sacred Prostitution in Antiquity (1 ed.). Cambridge University Press. doi:10.1017/cbo9780511497766. ISBN 978-0-521-88090-9.

- ^ Kapparis, Konstantinos (23 October 2017), "1. Prostitution in the Archaic Period", Prostitution in the Ancient Greek World, De Gruyter, pp. 15–46, doi:10.1515/9783110557954-001, ISBN 978-3-11-055795-4, retrieved 14 February 2023

- ^ Lear, Andrew (15 November 2013), Hubbard, Thomas K. (ed.), "Ancient Pederasty: An Introduction", A Companion to Greek and Roman Sexualities, Chichester, UK: John Wiley & Sons, Ltd, pp. 102–127, doi:10.1002/9781118610657.ch7, ISBN 978-1-118-61065-7, retrieved 14 February 2023

- ^ a b McGinn, Thomas A. J. (27 February 2003). Prostitution, Sexuality, and the Law in Ancient Rome (1 ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/acprof:oso/9780195161328.001.0001. ISBN 978-0-19-516132-8.

- ^ Edwards, Catharine (31 December 1998), Hallett, Judith P.; Skinner, Marilyn B. (eds.), "Unspeakable Professions: Public Performance and Prostitution in Ancient Rome", Roman Sexualities, Princeton University Press, pp. 66–96, doi:10.1515/9780691219547-005, ISBN 978-0-691-21954-7, retrieved 14 February 2023

- ^ McGinn, Thomas A. J. (27 February 2003), "Ne Serva Prostituatur: Restrictive Covenants in the Sale of Slaves", Prostitution, Sexuality, and the Law in Ancient Rome (1 ed.), Oxford University PressNew York, pp. 288–319, doi:10.1093/acprof:oso/9780195161328.003.0008, ISBN 978-0-19-516132-8, retrieved 25 April 2023

- ^ a b Rollo-Koster, Joelle (2002). "From Prostitutes to Brides of Christ: The Avignonese Repentises in the Late Middle Ages". Journal of Medieval and Early Modern Studies. 31 (1): 110. doi:10.1215/10829636-32-1-109. S2CID 170873311.

- ^ a b Bullough & Brundage 2000, pp. 243–260.

- ^ Roberts 1992, p. 65.

- ^ a b Findlen, Fontaine & Osheim 2003, p. 98.

- ^ Otis 1985, p. 16.

- ^ Rossiaud 1996, p. 32.

- ^ Bullough & Brundage 1994, p. 34.

- ^ a b Rossiaud 1996, p. 3.

- ^ Karras 1998, pp. 13–31.

- ^ a b Sanger 1859, p. 97.

- ^ Knauer 2002, pp. 95–117.

- ^ Knauer 2002, p. 101.

- ^ Mortimer, Ian (2012). The Time Traveller's Guide to Medieval England: A Handbook for Visitors to the Fourteenth Century. Random House. p. 102. ISBN 9781448103782.

- ^ Karras 1998, p. 32; Rossiaud 1996, p. 6.

- ^ Rossiaud 1996, p. 41.

- ^ Rossiaud 1996, p. 42.

- ^ Rossiaud 1996, p. 43.

- ^ Geremek 2006, p. 216.

- ^ a b Karras 1998, p. 106.

- ^ Bullough & Brundage 1994, p. 37.

- ^ Karras 1998, pp. 13–107.

- ^ "Columbus May Have Brought Syphilis to Europe". LiveScience. 15 January 2008.

- ^ Otis 1985, p. 41.

- ^ Otis 1985, p. 44.

- ^ London Commissary Court Act Books. London: Department of Manuscripts. 1470–1473.

- ^ Bennett 1989, p. 81.

- ^ Otis 1985, p. 13.

- ^ Rossiaud 1996, p. 160; Otis 1985, p. 12.

- ^ Bullough & Brundage 1994, p. 36.

- ^ Karras, Ruth (July 1990). "Holy Harlots: Prostitute Saints in Medieval Legend". Journal of the History of Sexuality. 1 (1): 4. PMID 11622758.

- ^ Bullough & Brundage 1994, p. 41; Roberts 1992, pp. 73–4.

- ^ Bullough & Brundage 1994, pp. 41–42.

- ^ "L. Roper: Luther on sex, marriage, and motherhood. The University of Warwick".

- ^ Harsin 1985, pp. 3, 25.

- ^ Gale 2002, p. 245.

- ^ Flowers 1998, p. 169.

- ^ Wickman, Forrest (5 November 2011). ""Socialist Whores": What did Karl Marx think of prostitutes?". Slate. Retrieved 5 November 2011.

- ^ Hornblower, Margot (24 June 2001). "The Skin Trade". Time Magazine. Retrieved 19 April 2009.

- ^ "Why Dubai's Islamic austerity is a sham – sex is for sale in every bar". The Guardian. 16 May 2010.

- ^ Zilfi, M. (2010). Women and Slavery in the Late Ottoman Empire: The Design of Difference. Storbritannien: Cambridge University Press. p. 217

- ^ B. Belli, "Registered female prostitution in the Ottoman Empire (1876-1909)," Ph.D. - Doctoral Program, Middle East Technical University, 2020. p 56

- ^ İlkkaracan 2008, p. 36.

- ^ Meri, Josef W.; Bacharach, Jere L. (1 January 2006). Medieval Islamic Civilization: L-Z, index. Taylor & Francis. ISBN 9780415966924.

- ^ Pohl, Florian (1 September 2010). Muslim World: Modern Muslim Societies. Marshall Cavendish. pp. 52–53. ISBN 9780761479277. Retrieved 5 April 2013.

- ^ Parshall, Philip L.; Parshall, Julie (1 April 2003). Lifting the Veil: The World of Muslim Women. InterVarsity Press. ISBN 9780830856961.

- ^ Baran, Zeyno (21 July 2011). Citizen Islam: The Future of Muslim Integration in the West. A&C Black. ISBN 9781441112484.

- ^ Andreeva, Elena (2007). Russia and Iran in the great game: travelogues and Orientalism. Routledge studies in Middle Eastern history. 8. Psychology Press. pp. 162–163. ISBN 0415771536. "Most of the travelers describe the Shi'i institution of temporary marriage (sigheh) as 'legalized profligacy' and hardly distinguish between temporary marriage and prostitution."

- ^ Temporary Marriage in Islam Part 6: Similarities and Differences of Mut’a and Regular Marriage | A Shi'ite Encyclopedia | Books on Islam and Muslims | Al-Islam.org. Permanent archived link.

- ^ "Iddah Of Mutah". ShiaChat.com. Archived from the original on 19 June 2018. Retrieved 17 November 2018.

- ^ "Marriage " Mut'ah (temporary marriage) - Islamic Laws - The Official Website of the Office of His Eminence Al-Sayyid Ali Al-Husseini Al-Sistani". www.sistani.org.

- ^ "The Rules in Matrimony and Marriage". Al-Islam.org. 3 October 2012.

- ^ "How is Mutah different from prostitution (from a non-Muslim point of view)?". islam.stackexchange.com.

- ^ "Marriage". english.bayynat.org.lb. Archived from the original on 23 February 2018. Retrieved 17 November 2018.

- ^ Gazali 2001, p. 106.

- ^ Kemal Sılay (1994). Nedim and the poetics of the Ottoman court. Indiana University. ISBN 978-1-878318-09-1.

- ^ Toledano 2003, p. 242 "[Flaubert, January 1850:] Be informed, furthermore, that all of the bath-boys are bardashes [male homosexuals].".

- ^ a b Hyam, R. (2010). Understanding the British Empire. Cambridge University Press. p. 372. ISBN 978-1-139-78846-5. Retrieved 1 November 2023.