Recent from talks

Contribute something

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Key Information

| Papal styles of Pope Leo XIV | |

|---|---|

| |

| Reference style | His Holiness |

| Spoken style | Your Holiness |

| Religious style | Holy Father |

The pope[a] is the bishop of Rome and the head of the worldwide Catholic Church. He is also known as the supreme pontiff,[b] Roman pontiff,[c] or sovereign pontiff. From the 8th century until 1870, the pope was the sovereign or head of state of the Papal States, and since 1929 of the much smaller Vatican City State.[4][5] From a Catholic viewpoint, the primacy of the bishop of Rome is largely derived from his role as the apostolic successor to Saint Peter, to whom primacy was conferred by Jesus, who gave Peter the Keys of Heaven and the powers of "binding and loosing", naming him as the "rock" upon which the Church would be built. The current pope is Leo XIV, who was elected on 8 May 2025 on the second day of the 2025 papal conclave.[6]

While his office is called the papacy, the jurisdiction of the episcopal see is called the Holy See.[7] The word see comes from the Latin for 'seat' or 'chair' (sede, referring in particular to the one on which the newly elected pope sits during the enthronement ceremony).[8] The Holy See is a sovereign entity under international law; it is headquartered in the distinctively independent Vatican City, a city-state which forms a geographical enclave within the conurbation of Rome. It was established by the Lateran Treaty in 1929 between Fascist Italy and the Holy See to ensure its political and spiritual independence. The Holy See is recognized by its adherence at various levels to international organizations and by means of its diplomatic relations and political accords with many independent states.

According to Catholic tradition, the apostolic see of Rome was founded by Saint Peter and Saint Paul in the first century. The papacy is one of the most enduring institutions in the world and has had a prominent part in human history.[9] In ancient times, the popes helped spread Christianity and intervened to find resolutions in various doctrinal disputes.[10] In the Middle Ages, they played a role of secular importance in Western Europe, often acting as arbitrators between Christian monarchs.[11][12][d] In addition to the expansion of Christian faith and doctrine, modern popes are involved in ecumenism and interfaith dialogue, charitable work, and the defence of human rights.[13]

Over time, the papacy accrued broad secular and political influence, eventually rivalling those of territorial rulers. In recent centuries, the temporal authority of the papacy has declined and the office is now largely focused on religious matters.[10] By contrast, papal claims of spiritual authority have been increasingly firmly expressed over time, culminating in 1870 with the proclamation of the dogma of papal infallibility for rare occasions when the pope speaks ex cathedra—literally 'from the chair (of Saint Peter)'—to issue a formal definition of faith or morals.[10] The pope is considered one of the world's most powerful people due to the extensive diplomatic, cultural, and spiritual influence of his position on both 1.3 billion Catholics and those outside the Catholic faith,[14][15][16][17] and because he heads the world's largest non-government provider of education and health care,[18] with a vast network of charities.

History

[edit]Title and etymology

[edit]The word pope derives from Ancient Greek πάππας (páppas) 'father'. In the early centuries of Christianity, this title was applied, especially in the East, to all bishops[19] and other senior clergy, and later became reserved in the West to the bishop of Rome during the reign of Pope Leo I (440–461),[20] a reservation made official only in the 11th century.[21][22][23][24][25] The earliest record of the use of the title of 'pope' was in regard to the by-then-deceased patriarch of Alexandria, Heraclas (232–248).[26] The earliest recorded use of the title "pope" in English dates to the mid-10th century, when it was used in reference to the 7th century Roman Pope Vitalian in an Old English translation of Bede's Historia ecclesiastica gentis Anglorum.[27]

Position within the Church

[edit]The Catholic Church teaches that the pastoral office, the office of shepherding the Church, that was held by the apostles, as a group or "college" with Saint Peter as their head, is now held by their successors, the bishops, with the bishop of Rome (the pope) as their head.[28] This gives rise to another title by which the pope is known: "supreme pontiff". The Catholic Church teaches that Jesus personally appointed Peter as the visible head of the Church,[e] and the Catholic Church's dogmatic constitution Lumen gentium makes a clear distinction between apostles and bishops, presenting the latter as the successors of the former, with the pope as successor of Peter, in that he is head of the bishops as Peter was head of the apostles.[30] Some historians argue against the notion that Peter was the first bishop of Rome, noting that the episcopal see in Rome can be traced back no earlier than the 3rd century.[31]

The writings of Irenaeus, a Church Father who wrote around 180 AD, reflect a belief that Peter "founded and organized" the Church at Rome.[32] Moreover, Irenaeus was not the first to write of Peter's presence in the early Roman Church. The Church of Rome wrote in a letter to the Corinthians (which is traditionally attributed to Clement of Rome c. 96)[33] about the persecution of Christians in Rome as the "struggles in our time" and presented to the Corinthians its heroes, "first, the greatest and most just columns", the "good apostles" Peter and Paul.[34] Ignatius of Antioch wrote shortly after Clement; in his letter from the city of Smyrna to the Romans, he said he would not command them as Peter and Paul did.[35] Given this and other evidence, such as Emperor Constantine's erection of the "Old St. Peter's Basilica" on the location of Saint Peter's tomb, as held and given to him by Rome's Christian community, many scholars agree that Peter was martyred in Rome under Nero, although some scholars argue that he may have been martyred in Palestine.[36][37][38]

Although open to historical debate, first-century Christian communities may have had a group of presbyter-bishops functioning as guides of their local churches. Gradually, episcopal sees were established in metropolitan areas.[39] Antioch may have developed such a structure before Rome.[39] In Rome, there were over time at various junctures rival claimants to be the rightful bishop, though again Irenaeus stressed the validity of one line of bishops from the time of St. Peter up to his contemporary Pope Victor I and listed them.[40] Some writers claim that the emergence of a single bishop in Rome probably did not occur until the middle of the 2nd century. In their view, Linus, Cletus and Clement were possibly prominent presbyter-bishops, but not necessarily monarchical bishops.[31] Documents of the 1st century and early second century indicate that the bishop of Rome had some kind of pre-eminence and prominence in the Church as a whole, as even a letter from the bishop, or patriarch, of Antioch acknowledged the bishop of Rome as "a first among equals",[41] though the detail of what this meant is unclear.[f]

Early Christianity (c. 30–325)

[edit]Sources suggest that at first, the terms episcopos and presbyter were used interchangeably,[45] with the consensus among scholars being that by the turn of the 1st and 2nd centuries, local congregations were led by bishops and presbyters, whose duties of office overlapped or were indistinguishable from one another.[46] Some[who?] say that there was probably "no single 'monarchical' bishop in Rome before the middle of the 2nd century ... and likely later."[47]

In the early Christian era, Rome and a few other cities had claims on the leadership of worldwide Church. James the Just, known as "the brother of the Lord", served as head of the Jerusalem church, which is still honoured as the "Mother Church" in Orthodox tradition. Alexandria had been a center of Jewish learning and became a center of Christian learning. Rome had a large congregation early in the apostolic period whom Paul the Apostle addressed in his Epistle to the Romans, and according to tradition Paul was martyred there.[48]

During the 1st century of the Church (c. 30–130), the Roman capital became recognized as a Christian center of exceptional importance. The church there, at the end of the century, wrote an epistle to the Church in Corinth intervening in a major dispute, and apologizing for not having taken action earlier.[49] There are a few other references of that time to recognition of the authoritative primacy of the Roman See outside of Rome. In the Ravenna Document of 13 October 2007, theologians chosen by the Catholic and the Eastern Orthodox Churches stated:[50]

Both sides agree that this canonical taxis was recognised by all in the era of the undivided Church. Further, they agree that Rome, as the Church that "presides in love" according to the phrase of St. Ignatius of Antioch (To the Romans, Prologue), occupied the first place in the taxis, and that the bishop of Rome was therefore the protos among the patriarchs. They disagree, however, on the interpretation of the historical evidence from this era regarding the prerogatives of the bishop of Rome as protos, a matter that was already understood in different ways in the first millennium.

— Ravenna Document, 41

In AD 195, Pope Victor I, in what is seen as an exercise of Roman authority over other churches, excommunicated the Quartodecimans for observing Easter on the 14th of Nisan, the date of the Jewish Passover, a tradition handed down by John the Evangelist (see Easter controversy). Celebration of Easter on a Sunday, as insisted on by the pope, is the system that has prevailed (see computus).

Nicaea to East–West Schism (325–1054)

[edit]The Edict of Milan in 313 granted freedom to all religions in the Roman Empire,[51] beginning the Peace of the Church. In 325, the First Council of Nicaea condemned Arianism, declaring trinitarianism dogmatic, and in its sixth canon recognized the special role of the Sees of Rome, Alexandria, and Antioch.[52] Great defenders of Trinitarian faith included the popes, especially Liberius, who was exiled to Berea by Constantius II for his Trinitarian faith,[53] Damasus I, and several other bishops.[54]

In 380, the Edict of Thessalonica declared Nicene Christianity to be the state religion of the empire, with the name "Catholic Christians" reserved for those who accepted that faith.[55][56] While the civil power in the Eastern Roman Empire controlled the church, and the patriarch of Constantinople, the capital, wielded much power,[57] in the Western Roman Empire, the bishops of Rome were able to consolidate the influence and power they already possessed.[57] After the fall of the Western Roman Empire, barbarian tribes were converted to Arian Christianity or Nicene Christianity;[58] Clovis I, king of the Franks, was the first important barbarian ruler to convert to the mainstream church rather than Arianism, allying himself with the papacy. Other tribes, such as the Visigoths, later abandoned Arianism in favour of the established church.[58]

Middle Ages

[edit]

After the fall of the Western Roman Empire, the pope served as a source of authority and continuity. Pope Gregory I (c. 540–604) administered the church with strict reform. From an ancient senatorial family, Gregory worked with the stern judgement and discipline typical of ancient Roman rule. Theologically, he represents the shift from the classical to the medieval outlook; his popular writings are full of dramatic miracles, potent relics, demons, angels, ghosts, and the approaching end of the world.[59]

Gregory's successors were largely dominated by the exarch of Ravenna, the Byzantine emperor's representative in the Italian Peninsula. These humiliations, the weakening of the Byzantine Empire in the face of the Muslim conquests, and the inability of the emperor to protect the papal estates against the Lombards, made Pope Stephen II turn from Emperor Constantine V. He appealed to the Franks to protect his lands. Pepin the Short subdued the Lombards and donated Italian land to the papacy. When Pope Leo III crowned Charlemagne (800) as emperor, he established the precedent that, in Western Europe, no man would be emperor without being crowned by a pope.[59]

The low point of the papacy was 867–1049.[60] This period includes the Saeculum obscurum, the Crescentii era, and the Tusculan Papacy. The papacy came under the control of vying political factions. Popes were variously imprisoned, starved, killed, and deposed by force. The Counts of Tusculum made and unmade popes for fifty years. Pope John XII, the great-grandson of one such count, held orgies of debauchery in the Lateran Palace. Emperor Otto I had John accused in an ecclesiastical court, which deposed him and elected a layman as Pope Leo VIII. John mutilated the Imperial representatives in Rome and had himself reinstated as pope. Conflict between the Emperor and the papacy continued, and eventually dukes in league with the emperor were buying bishops and popes almost openly.[61]

In 1049, Leo IX travelled to the major cities of Europe to deal with the church's moral problems firsthand, notably simony and clerical marriage and concubinage. With his long journey, he restored the prestige of the papacy in Northern Europe.[61] From the 7th century, it became common for European monarchies and nobility to found churches and perform investiture or deposition of clergy in their states and fiefdoms, their personal interests causing corruption among the clergy.[62][63] This practice had become common in part because the prelates and secular rulers were also often participants in public life.[64]

To combat this, and other practices that had been seen as corrupting, between the years 900 and 1050, centres emerged promoting ecclesiastical reform, the most important being the Abbey of Cluny, which spread its ideals throughout Europe.[63] This reform movement gained strength with the election of Pope Gregory VII in 1073, who adopted a series of measures in the movement known as the Gregorian Reform, in order to fight strongly against simony and the abuse of civil power and try to restore ecclesiastical discipline, including clerical celibacy.[54]

In 1122, this conflict between popes and secular autocratic rulers such as the Holy Roman Emperor Henry IV and King Henry I of England, known as the Investiture controversy, was resolved by the Concordat of Worms, in which Pope Callixtus II decreed that clerics were to be invested by clerical leaders, and temporal rulers by lay investiture.[62] Soon after, Pope Alexander III began reforms that would lead to the establishment of canon law.[59]

Starting at the beginning of the 7th century, Islamic conquests had succeeded in controlling much of the southern Mediterranean. This was perceived as a threat to Christianity.[65] In 1095, the Byzantine emperor, Alexios I Komnenos, asked for military aid from Pope Urban II in the ongoing Byzantine–Seljuq wars.[66] Urban, at the council of Clermont, called the First Crusade to assist the Byzantine Empire to regain the old Christian territories, especially Jerusalem.[67]

East–West Schism to Reformation (1054–1517)

[edit]

With the East–West Schism, the Eastern Orthodox Church and the Catholic Church split definitively in 1054. This fracture was caused more by political events than by slight divergences of creed. Popes had galled the Byzantine emperors by siding with the king of the Franks, crowning a rival Roman emperor, appropriating the Exarchate of Ravenna, and driving into Greek Italy.[61]

In the Middle Ages, popes struggled with monarchs over power.[10] From 1309 to 1377, the pope resided not in Rome but in Avignon. The Avignon Papacy was notorious for greed and corruption.[68] During this period, the pope was effectively an ally of the Kingdom of France, alienating France's enemies, such as the Kingdom of England.[69]

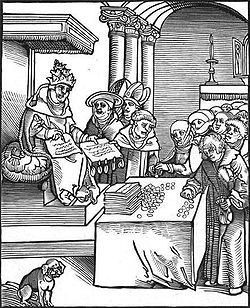

The pope was understood to have the power to draw on the Treasury of Merit built up by the saints and by Christ, so that he could grant indulgences, reducing one's time in purgatory. The concept that a monetary fine or donation accompanied contrition, confession, and prayer eventually gave way to the common assumption that indulgences depended on a simple monetary contribution. The popes condemned misunderstandings and abuses, but were too pressed for income to exercise effective control over indulgences.[68]

Popes also contended with the cardinals, who sometimes attempted to assert the authority of Catholic Ecumenical Councils over the pope's. Conciliarism holds that the supreme authority of the church lies with a General Council, not with the pope. Its foundations were laid early in the 13th century, and it culminated in the 15th century with Jean Gerson as its leading spokesman. The failure of Conciliarism to gain broad acceptance after the 15th century is taken as a factor in the Protestant Reformation.[70]

Various Antipopes challenged papal authority, especially during the Western Schism (1378–1417). It came to a close when the Council of Constance, at the high point of Concilliarism, decided among the papal claimants. The Eastern Church continued to decline with the Eastern Roman (Byzantine) Empire, undercutting Constantinople's claim to equality with Rome. Twice an Eastern emperor tried to force the Eastern Church to reunify with the West. First in the Second Council of Lyon (1272–1274) and secondly in the Council of Florence (1431–1449). Papal claims of superiority were a sticking point in reunification, which failed in any event. In the 15th century, the Ottoman Empire captured Constantinople and ended the Byzantine Empire.[71]

Reformation to present (1517 to today)

[edit]

Protestant Reformers criticized the papacy as corrupt and characterized the pope as the antichrist.[72][73][74][75] Popes instituted a Catholic Reformation[10] (1560–1648), which addressed the challenges of the Protestant Reformation and instituted internal reforms. Pope Paul III initiated the Council of Trent (1545–1563), whose definitions of doctrine and whose reforms sealed the triumph of the papacy over elements in the church that sought conciliation with Protestants and opposed papal claims.[76]

Gradually forced to give up secular power to the increasingly assertive European nation states, the popes focused on spiritual issues.[10] In 1870, the First Vatican Council proclaimed the dogma of papal infallibility for the most solemn occasions when the pope speaks ex cathedra when issuing a definition of faith or morals.[10] Later the same year, Victor Emmanuel II of Italy seized Rome from the pope's control and substantially completed the unification of Italy.[10]

In 1929, the Lateran Treaty between the Kingdom of Italy and the Holy See established Vatican City as an independent city-state, guaranteeing papal independence from secular rule.[10] In 1950, Pope Pius XII defined the Assumption of Mary as dogma, the only time a pope has spoken ex cathedra since papal infallibility was explicitly declared. The Primacy of St. Peter, the controversial doctrinal basis of the pope's authority, continues to divide the eastern and western churches and to separate Protestants from Rome.

Early Christian mentions

[edit]Church Fathers

[edit]The writings of several Early Church fathers contain references to the authority and unique position held by the bishops of Rome, providing valuable insight into the recognition and significance of the papacy during the early Christian era.[77] These sources attest to the acknowledgement of the bishop of Rome as an influential figure within the Church, with some emphasizing the importance of adherence to Rome's teachings and decisions. Such references served to establish the concept of papal primacy and have continued to inform Catholic theology and practice.[78][79]

In his letters, Cyprian of Carthage (c. 210 – 258 AD) recognized the bishop of Rome as the successor of St. Peter in his Letter 55 (c. 251 AD), which is addressed to Pope Cornelius,[80][81] and affirmed his unique authority in the early Christian Church.[82]

Cornelius [the Bishop of Rome] was made bishop by the choice of God and of His Christ, by the favorable witness of almost all the clergy, by the votes of the people who were present, and by the assembly of ancient priests and good men. And he was made bishop when no one else had been made bishop before him when the position of Fabian, that is to say, the position of Peter and the office of the bishop's chair, was vacant. But the position once has been filled by the will of God and that appointment has been ratified by the consent of us all, if anyone wants to be made bishop after that, it has to be done outside the church; if a man does not uphold the unity of the Church's unity, it is not possible for him to have the Church's ordination.

— Cyprian of Carthage, Letter 55, 8.4

Irenaeus of Lyons (c. 130 – c. 202 AD), a prominent Christian theologian of the second century, provided a list of early popes in his work Against Heresies III. The list covers the period from Saint Peter to Pope Eleutherius who served from 174 to 189 AD.[83][84]

The blessed apostles [Peter and Paul], then, having founded and built up the Church [in Rome], committed into the hands of Linus the office of the episcopate. Of this Linus, Paul makes mention in the Epistles to Timothy. To him succeeded Anacletus; and after him, in the third place from the apostles, Clement was allotted the bishopric. ... To this Clement there succeeded Eviristus. Alexander followed Evaristus; then, sixth from the apostles, Sixtus was appointed; after him, Telephorus, who was gloriously martyred; then Hyginus; after him, Pius; then after him, Anicetus. Soter having succeeded Anicetus, Eleutherius does now, in the twelfth place from the apostles, hold the inheritance of the episcopate.

— Irenaeus of Lyons, Against Heresies III, Chapter 3.2

Ignatius of Antioch (died c. 108/140 AD) wrote in his "Epistle to the Romans" that the church in Rome is "the church that presides over love".[85][86]

...the Church which is beloved and enlightened by the will of Him that wills all things which are according to the love of Jesus Christ our God, which also presides in the place of the region of the Romans, worthy of God, worthy of honour, worthy of the highest happiness, worthy of praise, worthy of obtaining her every desire, worthy of being deemed holy, and which presides over love, is named from Christ, and from the Father, which I also salute in the name of Jesus Christ, the Son of the Father: to those who are united, both according to the flesh and spirit, to every one of His commandments;

— Ignatius of Antioch, Epistle to Romans

Augustine of Hippo (354–430), in his Letter 53, wrote a list of 38 popes from Saint Peter to Siricius. The order of this list differs from the lists of Irenaeus and the Annuario Pontificio. Augustine's list claims that Linus was succeeded by Clement and Clement was succeeded by Anacletus as in the list of Eusebius, while the other two lists switch the positions of Clement and Anacletus.[87]

For if the lineal succession of bishops is to be taken into account, with how much more certainty and benefit to the Church do we reckon back till we reach Peter himself, to whom, as bearing in a figure the whole Church, the Lord said: Upon this rock will I build my Church, and the gates of hell shall not prevail against it! Matthew 16:18. The successor of Peter was Linus, and his successors in unbroken continuity were these:— Clement, Anacletus, Evaristus...

— Augustine of Hippo, Letter 53, Paragraph 2

Other early Christian mentions

[edit]Eusebius (c. 260/265 – 339) mentions Linus as Saint Peter's successor and Clement as the third bishop of Rome in his book Church History. As recorded by Eusebius, Clement worked with Saint Paul as his "co-laborer".[88]

As to the rest of his followers, Paul testifies that Crescens was sent to Gaul; but Linus, whom he mentions in the Second Epistle to Timothy as his companion at Rome, was Peter's successor in the episcopate of the church there, as has already been shown. Clement also, who was appointed third bishop of the church at Rome, was, as Paul testifies, his co-laborer and fellow-soldier.

— Eusebius of Caesarea, Church History, Book III, Chapter 4:9-10

Tertullian (c. 155 – c. 220 AD) wrote in his work "The Prescription Against Heretics" about the authority of the church in Rome. In this work, Tertullian said that the Church in Rome has the authority of the Apostles because of its apostolic foundation.[89]

Since, moreover, you are close upon Italy, you have Rome, from which there comes even into our own hands the very authority (of apostles themselves). How happy is its church, on which apostles poured forth all their doctrine along with their blood! Where Peter endures a passion like his Lord's! Where Paul wins his crown in a death like John's where the Apostle John was first plunged, unhurt, into boiling oil, and thence remitted to his island-exile!

— Tertullian, The Prescription Against Heretics, Chapter 32

According to the same book, Clement of Rome was ordained by Saint Peter as the bishop of Rome.

For this is the manner in which the apostolic churches transmit their registers: as the church of Smyrna, which records that Polycarp was placed therein by John; as also the church of Rome, which makes Clement to have been ordained in like manner by Peter.

— Tertullian, Prescription against Heretics, Chapter 32

Optatus the bishop of Milevis in Numidia (today's Algeria) and a contemporary of the Donatist schism, presents a detailed analysis of the origins, beliefs, and practices of the Donatists, as well as the events and debates surrounding the schism, in his book The Schism of the Donatists (367 A.D). In the book, Optatus wrote about the position of the bishop of Rome in maintaining the unity of the Church.[90][91]

You cannot deny that you are aware that in the city of Rome the episcopal chair was given first to Peter; the chair in which Peter sat, the same who was head—that is why he is also called Cephas ['Rock']—of all the apostles; the one chair in which unity is maintained by all.

— Optatus, The Schism of the Donatists, 2:2

Saint Peter and the origin of the papal office

[edit]The Catholic Church teaches that, within the Christian community, the bishops as a body has succeeded the apostles as a body (apostolic succession) and the bishop of Rome has succeeded Saint Peter.[4] Scriptural texts proposed in support of Peter's special position in relation to the church include:

- Matthew 16:

I tell you, you are Peter, and on this rock I will build my church, and the gates of hell shall not prevail against it. I will give you the keys of the kingdom of heaven, and whatever you bind on earth shall be bound in heaven, and whatever you loose on earth shall be loosed in heaven.[92]

- Luke 22:

Simon, Simon, behold, Satan demanded to have you, that he might sift you like wheat, but I have prayed for you that your faith may not fail. And when you have turned again, strengthen your brothers.[93]

- John 21:

Feed my sheep.[94]

The symbolic keys in the Papal coats of arms are a reference to the phrase "the keys of the kingdom of heaven" in the first of these texts. Some Protestant writers have maintained that the "rock" that Jesus speaks of in this text is Jesus himself or the faith expressed by Peter.[95][96][97][98][99][100] This idea is undermined by the Biblical usage of "Cephas", which is the masculine form of "rock" in Aramaic, to describe Peter.[101][102][103] The Encyclopædia Britannica comments that "the consensus of the great majority of scholars today is that the most obvious and traditional understanding should be construed, namely, that rock refers to the person of Peter".[104]

New Eliakim

[edit]According to the Catholic Church, the pope is also the new Eliakim, a figure in the Old Testament of the Bible who directed the affairs of the royal court, managed the palace staff, and handled state affairs. Isaiah also describes him as having the key to the house of David, which symbolizes his authority and power.[105]

Both Matthew 16:18–19 and Isaiah 22:22 show similarities between Eliakim and Peter getting keys which symbolize power. Eliakim gets the power to close and open, while Peter gets the power to bind and loose. According to the Book of Isaiah, Eliakim receives the keys and power to close and open.

I will place the key of the House of David on his shoulder; what he opens, no one will shut, what he shuts, no one will open.[106]

— Isaiah, 22:22

According to the book of Matthew, Peter also gets keys and power to bind and loose.

I will give you the keys of the kingdom of heaven, and whatever you bind on earth shall be bound in heaven, and whatever you loose on earth shall be loosed in heaven.[107]

— Matthew, 16:19

In the Books of Isaiah 22:3 and Matthew 16:18, both Eliakim and Peter are compared to an object. Eliakim to a peg (a structure that is driven into a wall or other structure to provide support and stability) while Peter to a rock.

And I will fasten him like a peg in a secure place, and he will become a throne of honor to his father's house.[108]

— Isaiah, 22:23

In Matthew 16:18 Peter was compared to a rock.

And I tell you, you are Peter, and on this rock I will build my church, and the gates of hell shall not prevail against it[109]

— Matthew, 16:18

Election, death, and resignation

[edit]Election

[edit]

The pope was originally chosen by those senior clergymen resident in and near Rome. In 1059, the electorate was restricted to the cardinals of the Holy Roman Church, and the individual votes of all cardinal electors were made equal in 1179. The electors are now limited to those cardinals who have not reached the age of 80 on the day before the death or resignation of a pope.[110] The pope does not need to be a cardinal elector nor indeed even a cardinal; since the pope is the bishop of Rome, only one who can be ordained a bishop can be elected, which means that any male baptized Catholic is eligible. The last to be elected when not yet a bishop was Gregory XVI in 1831, the last to be elected when not even a priest was Leo X in 1513, and the last to be elected when not a cardinal was Urban VI in 1378.[111] If someone who is not a bishop is elected, he must be given episcopal ordination before the election is announced to the people.[112]

The Second Council of Lyon was convened on 7 May 1274, to regulate the election of the pope. It was decreed at this council that the cardinal electors must meet within ten days of the pope's death, and that they must remain in seclusion until a pope has been elected; this was prompted by the three-year sede vacante following the death of Clement IV in 1268. By the mid-16th century, the electoral process had evolved into its present form, allowing for variation in the time between the death of the pope and the meeting of the cardinal electors.[113] Traditionally, the vote was conducted by acclamation, by selection (by committee), or by plenary vote. Acclamation was the simplest procedure, consisting entirely of a voice vote.

Since 1878, the election of the pope has taken place in the Sistine Chapel, in a sequestered meeting called a "conclave" (so called because the cardinal electors are theoretically locked in, cum clave, i.e., with key, until they elect a new pope). Three cardinals are chosen by lot to collect the votes of absent cardinal electors (by reason of illness), three are chosen by lot to count the votes, and three are chosen by lot to review the count of the votes. The ballots are distributed and each cardinal elector writes the name of his choice on it and pledges aloud that he is voting for "one whom under God I think ought to be elected" before folding and depositing his vote on a plate atop a large chalice placed on the altar.

For the 2005 papal conclave, a special urn was used for this purpose instead of a chalice and plate. The plate is then used to drop the ballot into the chalice, making it difficult for electors to insert multiple ballots. Before being read, the ballots are counted while still folded; if the number of ballots does not match the number of electors, the ballots are burned unopened and a new vote is held. Otherwise, each ballot is read aloud by the presiding cardinal, who pierces the ballot with a needle and thread, stringing all the ballots together and tying the ends of the thread to ensure accuracy and honesty. Balloting continues until someone is elected by a two-thirds majority. With the promulgation of Universi Dominici Gregis in 1996, a simple majority after a deadlock of twelve days was allowed, but this was revoked by Pope Benedict XVI by motu proprio in 2007.

The dean of the College of Cardinals then asks two solemn questions of the man who has been elected. First he asks, "Do you freely accept your election as supreme pontiff?" If the pope-elect replies with the word "Accepto", his reign begins at that instant. In practice, any cardinal who intends not to accept will explicitly state this before he receives a sufficient number of votes to become pope.[114][115] The dean asks next, "By what name shall you be called?" The new pope announces the regnal name he has chosen. If the dean of the college himself is elected pope, as was the case in the 2005 conclave with the election of Pope Benedict XVI, the vice dean performs this task.[116]

The new pope is led to the Room of Tears, a dressing room where three sets of white papal vestments (immantatio) await in three sizes.[117] Donning the appropriate vestments and reemerging into the Sistine Chapel, the new pope is given the "Fisherman's Ring" by the camerlengo of the Holy Roman Church.[118] The pope assumes a place of honour as the rest of the cardinals wait in turn to offer their first "obedience" (adoratio) and to receive his blessing.[119]

One of the most prominent aspects of the papal election process is the means by which the results of each round of voting are announced to the world. Once the ballot papers are counted and bound together, they are burned in a special stove erected in the Sistine Chapel, with the smoke escaping through a small chimney visible from Saint Peter's Square. The ballots from an unsuccessful vote are burned along with a chemical compound to create black smoke, or fumata nera. Traditionally, wet straw was used to produce the black smoke, but this was not completely reliable; the chemical compound is more reliable than the straw. When a vote is successful, the ballots are burned alone, sending white smoke (fumata bianca) through the chimney and announcing to the world the election of a new pope.[120] Starting with the papal conclave of 2005,[121] church bells are also rung as a signal that a new pope has been chosen.[122][123]

A short time later, the cardinal protodeacon announces from a balcony over St. Peter's Square the following proclamation: Annuntio vobis gaudium magnum! Habemus Papam! ("I announce to you a great joy! We have a pope!"). He announces the new pope's Christian name along with his newly-chosen regnal or papal name.[124][125]

Until 1978, the pope's election was followed in a few days by the papal coronation, which started with a procession with great pomp and circumstance from the Sistine Chapel to St. Peter's Basilica, with the newly elected pope borne in the sedia gestatoria (a carried papal throne). After a solemn Papal Mass, the new pope was crowned with the triregnum (papal tiara) and he gave for the first time as pope the famous blessing Urbi et Orbi ("to the City [Rome] and to the World"). Another renowned part of the coronation was the lighting of a bundle of flax at the top of a gilded pole, which would flare brightly for a moment and then promptly extinguish, as he said, Sic transit gloria mundi ("Thus passes worldly glory"). A similar warning against papal hubris made on this occasion was the traditional exclamation, "Annos Petri non-videbis", reminding the newly crowned pope that he would not live to see his rule lasting as long as that of St. Peter. According to tradition, Peter headed the church for 35 years, and has thus far been the longest-reigning pope in the history of the Catholic Church.[126] Nowadays, the newly elected pope celebrates a special mass to inaugurate his papacy, with many tens of thousands of catholic laity, church clerics and religious, and delegations from many nations and other churches across the world, in St Peter's Square.

For centuries, starting from 1378 onwards, those elected to the papacy were predominantly Italians. Prior to the election of the Polish-born John Paul II in 1978, the last non-Italian was Adrian VI of the Netherlands, elected in 1522. John Paul II was followed by election of the German-born Benedict XVI, who was in turn followed by Argentine-born Francis, the first non-European after 1272 years and the first Latin American (albeit of Italian ancestry).[127][128] The most recent election, of Pope Leo XIV (formerly Robert Francis Cardinal Prevost), continues this new tradition of papal selection from a global pool: the current pope was born and lived until his mid-20s in the United States, is a citizen by naturalization of Peru (where he served as an Augustinian priest and bishop for approximately 20 years), and had by the time of his election spent almost 20 years in Italy and the Vatican studying and in various Church leadership roles.

Death

[edit]

The current regulations regarding a papal interregnum—that is, a sede vacante ("vacant seat", literally 'while the see is vacant')—were promulgated by Pope John Paul II in his 1996 document Universi Dominici Gregis.[129] Sede vacante is a papal interregnum, the period between the death or resignation of a pope and the election of his successor. From this term is derived the term sedevacantism, which designates a category of dissident Catholics who maintain that there is no canonically and legitimately elected pope, and that there is therefore a sede vacante.[130]

During the sede vacante period, the College of Cardinals is collectively responsible for the government of the Church and of the Vatican itself, under the direction of the Camerlengo of the Holy Roman Church. Canon law specifically forbids the cardinals from introducing any innovation in the government of the Church during the vacancy of the Holy See. Any decision that requires the assent of the pope has to wait until the new pope has been elected and accepts office.[130]

In recent centuries, when a pope was judged to have died, it was reportedly traditional for the cardinal camerlengo to confirm the death ceremonially by gently tapping the pope's head thrice with a silver hammer, calling his birth name each time.[131] This was not done on the deaths of popes John Paul I[132] and John Paul II.[133] The cardinal camerlengo retrieves the Ring of the Fisherman and cuts it in two in the presence of the cardinals. The pope's seals are defaced, to keep them from ever being used again, and his personal apartment is sealed.[134]

The body lies in state for several days before being interred in the crypt of a leading church or cathedral; all popes who have died in the 20th and 21st centuries have been interred in St. Peter's Basilica, with the exception of Pope Francis as he requested to be interred in the Basilica of St. Mary Major. A nine-day period of mourning (novendialis) follows the interment.[134]

Resignation

[edit]It is highly unusual for a pope to resign.[135] The 1983 Code of Canon Law[136] states, "If it happens that the Roman Pontiff resigns his office, it is required for validity that the resignation is made freely and properly manifested but not that it is accepted by anyone." Benedict XVI, who vacated the Holy See on 28 February 2013, was the most recent to do so, and the first since Gregory XII's resignation in 1415.[137]

Titles

[edit]| Styles of The Pope | |

|---|---|

| |

| Reference style | His Holiness |

| Spoken style | Your Holiness |

| Religious style | Holy Father |

| Posthumous style | See here |

Regnal name

[edit]Popes adopt a new name on their accession, known as papal name, in Italian and Latin. Currently, after a new pope is elected and accepts the election, he is asked, "By what name shall you be called?" The new pope chooses the name by which he will be known from that point on. The senior cardinal deacon, or cardinal protodeacon, then appears on the balcony of Saint Peter's to proclaim the new pope by his birth name, and announce his papal name in Latin. It is customary when referring to popes to translate the regnal name into all local languages. For example, the current pope bears the papal name Papa Leo XIV in Latin, Papa Leone XIV in Italian, Papa Léon XIV in Spanish, Pope Leo XIV in English, etc.

The pope's regnal name is not his real or legal name, which remains unchanged in legal and governmental documents; neither is it connected in any way to his real name. The current pope was born with the name Robert Francis Prevost.

Official list of titles

[edit]The official list of titles of the pope, in the order in which they are given in the Annuario Pontificio, is:

Bishop of Rome, Vicar of Jesus Christ, Successor of the Prince of the Apostles, Supreme Pontiff of the Universal Church, Patriarch of the West, Primate of Italy, Archbishop and Metropolitan of the Roman Province, Sovereign of the Vatican City State, Servant of the servants of God.[138]

The best-known title, that of "pope", does not appear in the official list, but is commonly used in the titles of documents, and appears, in abbreviated form, in their signatures. Thus Paul VI signed as "Paulus PP. VI." Sources are divided on the meaning of "PP.," with some asserting that it is merely a reference to "papa" ("pope"), others "papa pontifex" ("pope and pontiff"), and others "pastor pastorum" ("shepherd of shepherds").[139][140][141][142][143][144]

The title "pope" was from the early 3rd century an honorific designation used for any bishop in the West.[19] In the East, it was used only for the bishop of Alexandria.[19] Marcellinus (d. 304) is the first bishop of Rome shown in sources to have had the title "pope" used of him. From the 6th century, the imperial chancery of Constantinople normally reserved this designation for the bishop of Rome.[19] From the early 6th century, it began to be confined in the West to the bishop of Rome, a practice that was firmly in place by the 11th century.[19]

In Eastern Christianity, where the title "pope" is used also of the bishop of Alexandria, the bishop of Rome is often referred to as the "pope of Rome", regardless of whether the speaker or writer is in communion with Rome or not.[145]

Vicar of Jesus Christ

[edit]"Vicar of Jesus Christ" (Vicarius Iesu Christi) is one of the official titles of the pope given in the Annuario Pontificio. It is commonly used in the slightly abbreviated form "vicar of Christ" (vicarius Christi). While it is only one of the terms with which the pope is referred to as "vicar", it is "more expressive of his supreme headship of the Church on Earth, which he bears in virtue of the commission of Christ and with vicarial power derived from him", a vicarial power believed to have been conferred on Saint Peter when Christ said to him: "Feed my lambs...Feed my sheep".[146][147]

The first record of the application of this title to a bishop of Rome appears in a synod of 495 with reference to Gelasius I.[148] But at that time, and down to the 9th century, other bishops too referred to themselves as vicars of Christ, and for another four centuries this description was sometimes used of kings and even judges,[149] as it had been used in the 5th and 6th centuries to refer to the Byzantine emperor.[150] Earlier still, in the 3rd century, Tertullian used "vicar of Christ" to refer to the Holy Spirit[151][152] sent by Jesus.[153] Its use specifically for the pope appears in the 13th century in connection with the reforms of Pope Innocent III,[150] as can be observed already in his 1199 letter to Leo I, King of Armenia.[154] Other historians suggest that this title was already used in this way in association with the pontificate of Eugene III (1145–1153).[148]

This title "vicar of Christ" is thus not used of the pope alone and has been used of all bishops since the early centuries.[155] The Second Vatican Council referred to all bishops as "vicars and ambassadors of Christ",[156] and this description of the bishops was repeated by John Paul II in his encyclical Ut unum sint, 95. The difference is that the other bishops are vicars of Christ for their own local churches, the pope is vicar of Christ for the whole Church.[157]

On at least one occasion the title "vicar of God" (a reference to Christ as God) was used of the pope.[147] The title "vicar of Peter" (vicarius Petri) is used only of the pope, not of other bishops. Variations of it include: "Vicar of the Prince of the Apostles" (Vicarius Principis Apostolorum) and "Vicar of the Apostolic See" (Vicarius Sedis Apostolicae).[147] Saint Boniface described Pope Gregory II as vicar of Peter in the oath of fealty that he took in 722.[158] In today's Roman Missal, the description "vicar of Peter" is found also in the collect of the Mass for a saint who was a pope.[159]

Supreme pontiff

[edit]

The term "pontiff" is derived from the Latin: pontifex, which literally means "bridge builder" (pons + facere) and which designated a member of the principal college of priests in pagan Rome.[160][161] The Latin word was translated into ancient Greek variously: as Ancient Greek: ἱεροδιδάσκαλος, Ancient Greek: ἱερονόμος, Ancient Greek: ἱεροφύλαξ, Ancient Greek: ἱεροφάντης (hierophant),[162] or Ancient Greek: ἀρχιερεύς (archiereus, high priest)[163][164] The head of the college was known as the Latin: Pontifex Maximus (the greatest pontiff).[165]

In Christian use, pontifex appears in the Vulgate translation of the New Testament to indicate the High Priest of Israel (in the original Koine Greek, ἀρχιερεύς).[166] The term came to be applied to any Christian bishop,[167] but since the 11th century commonly refers specifically to the bishop of Rome,[168] who is more strictly called the "Roman Pontiff". The use of the term to refer to bishops in general is reflected in the terms "Roman Pontifical" (a book containing rites reserved for bishops, such as confirmation and ordination), and "pontificals" (the insignia of bishops).[169]

The Annuario Pontificio lists as one of the official titles of the pope that of "Supreme Pontiff of the Universal Church" (Latin: Summus Pontifex Ecclesiae Universalis).[170] He is also commonly called the supreme pontiff or the sovereign pontiff (Latin: summus pontifex).[171] Pontifex Maximus, similar in meaning to Summus Pontifex, is a title commonly found in inscriptions on papal buildings, paintings, statues and coins, usually abbreviated as "Pont. Max" or "P.M." The office of Pontifex Maximus, or head of the College of Pontiffs, was held by Julius Caesar and thereafter, by the Roman emperors, until Gratian (375–383) relinquished it.[162][172][173] Tertullian, when he had become a Montanist, used the title derisively of either the pope or the bishop of Carthage.[174] The popes began to use this title regularly only in the 15th century.[174]

Servant of the servants of God

[edit]Although the description "servant of the servants of God" (Latin: servus servorum Dei) was also used by other Church leaders, including Augustine of Hippo and Benedict of Nursia, it was first used extensively as a papal title by Gregory the Great, reportedly as a lesson in humility for the patriarch of Constantinople, John the Faster, who had assumed the title "ecumenical patriarch". It became reserved for the pope in the 12th century and is used in papal bulls and similar important papal documents.[175]

Patriarch of the West

[edit]From 1863 to 2005, and again in 2024, the Annuario Pontificio also included the title "patriarch of the West". This title was first used by Pope Theodore I in 642, and was only used occasionally. Indeed, it did not begin to appear in the pontifical yearbook until 1863. On 22 March 2006, the Vatican released a statement explaining this omission on the grounds of expressing a "historical and theological reality" and of "being useful to ecumenical dialogue". The title patriarch of the West symbolized the pope's special relationship with, and jurisdiction over, the Latin Church—and the omission of the title neither symbolizes in any way a change in this relationship, nor distorts the relationship between the Holy See and the Eastern Churches, as solemnly proclaimed by the Second Vatican Council.[176] "Patriarch of the West" was reintroduced to the pope's list of titles in the 2024 edition of the Annuario Pontifico. The Vatican has not made any statements explaining why the title has been brought back into use.[177]

Other titles

[edit]Other titles commonly used are "His Holiness" (either used alone or as an honorific prefix as in "His Holiness Pope Leo"; and as "Your Holiness" as a form of address) and "Holy Father". In Spanish and Italian, "Beatísimo/Beatissimo Padre" (Most Blessed Father) is often used in preference to "Santísimo/Santissimo Padre" (Most Holy Father). In the medieval period, "Dominus Apostolicus" ("the Apostolic Lord") was also used.

Signature

[edit]Pope Francis signed some documents with his name alone, either in Latin ("Franciscus", as in an encyclical dated 29 June 2013)[178] or in another language.[179] Other documents he signed in accordance with the tradition of using Latin only and including the abbreviated form "PP.", for the Latin Papa ("Pope").[180] Popes who have an ordinal numeral in their name traditionally place the abbreviation "PP." before the ordinal numeral, as in "Leo PP. XIV" (Pope Leo XIV), except in papal bulls of canonization and decrees of ecumenical councils, which a pope signs with the formula, "Ego N. Episcopus Ecclesiae catholicae", without the numeral, as in "Ego Leo Episcopus Ecclesiae catholicae" (I, Leo, Bishop of the Catholic Church).

Regalia and insignia

[edit]- Ring of the Fisherman, a gold or gilt ring decorated with a depiction of St. Peter in a boat casting his net, with the pope's name around it.[181]

- Umbraculum (better known in the Italian form ombrellino) is a canopy or umbrella consisting of alternating red and gold stripes, which used to be carried above the pope in processions.[182]

- Sedia gestatoria, a mobile throne carried by twelve footmen (palafrenieri) in red uniforms, accompanied by two attendants bearing flabella (fans made of white ostrich feathers), and sometimes a large canopy, carried by eight attendants. The use of the flabella was discontinued by Pope John Paul I. The use of the sedia gestatoria was discontinued by Pope John Paul II.[183]

In heraldry, each pope has his own personal coat of arms. Though unique for each pope, the arms have for several centuries been traditionally accompanied by two keys in saltire (i.e., crossed over one another so as to form an X) behind the escutcheon (shield) (one silver key and one gold key, tied with a red cord), and above them a silver triregnum with three gold crowns and red infulae (lappets—two strips of fabric hanging from the back of the triregnum which fall over the neck and shoulders when worn). This is blazoned: "two keys in saltire or and argent, interlacing in the rings or, beneath a tiara argent, crowned or".

The 21st century has seen departures from this tradition. In 2005, Pope Benedict XVI, while maintaining the crossed keys behind the shield, omitted the papal tiara from his personal coat of arms, replacing it with a mitre with three horizontal lines. Beneath the shield he added the pallium, a papal symbol of authority more ancient than the tiara, the use of which is also granted to metropolitan archbishops as a sign of communion with the See of Rome. Although the tiara was omitted in the pope's personal coat of arms, the coat of arms of the Holy See, which includes the tiara, remained unaltered. In 2013, Pope Francis maintained the mitre that replaced the tiara, but omitted the pallium.

The flag most frequently associated with the pope is the yellow and white flag of Vatican City, with the arms of the Holy See (blazoned: "Gules, two keys in saltire or and argent, interlacing in the rings or, beneath a tiara argent, crowned or") on the right-hand side (the "fly") in the white half of the flag (the left-hand side—the "hoist"—is yellow). The pope's escucheon does not appear on the flag. This flag was first adopted in 1808, whereas the previous flag had been red and gold. Although Pope Benedict XVI replaced the triregnum with a mitre on his personal coat of arms, it has been retained on the flag.[184]

Papal garments

[edit]Pope Pius V (reigned 1566–1572), is often credited with having originated the custom whereby the pope wears white, by continuing after his election to wear the white habit of the Dominican order. In reality, the basic papal attire was white long before. The earliest document that describes it as such is the Ordo XIII, a book of ceremonies compiled in about 1274. Later books of ceremonies describe the pope as wearing a red mantle, mozzetta, camauro and shoes, and a white cassock and stockings.[185][186] Many contemporary portraits of 15th and 16th-century predecessors of Pius V show them wearing a white cassock similar to his.[187]

Status and authority

[edit]First Vatican Council

[edit]

The status and authority of the pope in the Catholic Church was dogmatically defined by the First Vatican Council on 18 July 1870. In its Dogmatic Constitution of the Church of Christ, the council established the following canons:[188]

If anyone says that the blessed Apostle Peter was not established by the Lord Christ as the chief of all the apostles, and the visible head of the whole militant Church, or, that the same received great honour but did not receive from the same our Lord Jesus Christ directly and immediately the primacy in true and proper jurisdiction: let him be anathema.[189]

If anyone says that it is not from the institution of Christ the Lord Himself, or by divine right that the blessed Peter has perpetual successors in the primacy over the universal Church, or that the Roman Pontiff is not the successor of blessed Peter in the same primacy, let him be anathema.[190]

If anyone thus speaks, that the Roman pontiff has only the office of inspection or direction, but not the full and supreme power of jurisdiction over the universal Church, not only in things which pertain to faith and morals, but also in those which pertain to the discipline and government of the Church spread over the whole world; or, that he possesses only the more important parts, but not the whole plenitude of this supreme power; or that this power of his is not ordinary and immediate, or over the churches altogether and individually, and over the pastors and the faithful altogether and individually: let him be anathema.[191]

We, adhering faithfully to the tradition received from the beginning of the Christian faith, to the glory of God, our Saviour, the elevation of the Catholic religion and the salvation of Christian peoples, with the approbation of the sacred Council, teach and explain that the dogma has been divinely revealed: that the Roman Pontiff, when he speaks ex cathedra, that is, when carrying out the duty of the pastor and teacher of all Christians by his supreme apostolic authority he defines a doctrine of faith or morals to be held by the universal Church, through the divine assistance promised him in blessed Peter, operates with that infallibility with which the divine Redeemer wished that His church be instructed in defining doctrine on faith and morals; and so such definitions of the Roman Pontiff from himself, but not from the consensus of the Church, are unalterable. But if anyone presumes to contradict this definition of Ours, which may God forbid: let him be anathema.[192]

Second Vatican Council

[edit]

In its Dogmatic Constitution on the Church (1964), the Second Vatican Council declared:

Among the principal duties of bishops the preaching of the Gospel occupies an eminent place. For bishops are preachers of the faith, who lead new disciples to Christ, and they are authentic teachers, that is, teachers endowed with the authority of Christ, who preach to the people committed to them the faith they must believe and put into practice, and by the light of the Holy Spirit illustrate that faith. They bring forth from the treasury of Revelation new things and old, making it bear fruit and vigilantly warding off any errors that threaten their flock. Bishops, teaching in communion with the Roman Pontiff, are to be respected by all as witnesses to divine and Catholic truth. In matters of faith and morals, the bishops speak in the name of Christ and the faithful are to accept their teaching and adhere to it with a religious assent. This religious submission of mind and will must be shown in a special way to the authentic magisterium of the Roman Pontiff, even when he is not speaking ex cathedra; that is, it must be shown so that his supreme magisterium is acknowledged with reverence, the judgments made by him are sincerely adhered to, according to his manifest mind and will. His mind and will in the matter may be known either from the character of the documents, from his frequent repetition of the same doctrine, or from his manner of speaking.

... this infallibility with which the Divine Redeemer willed His Church to be endowed in defining doctrine of faith and morals, extends as far as the deposit of Revelation extends, which must be religiously guarded and faithfully expounded. And this is the infallibility which the Roman Pontiff, the head of the College of Bishops, enjoys in virtue of his office, when, as the supreme shepherd and teacher of all the faithful, who confirms his brethren in their faith, by a definitive act he proclaims a doctrine of faith or morals. And therefore his definitions, of themselves, and not from the consent of the Church, are justly styled irreformable, since they are pronounced with the assistance of the Holy Spirit, promised to him in blessed Peter, and therefore they need no approval of others, nor do they allow an appeal to any other judgment. For then the Roman Pontiff is not pronouncing judgment as a private person, but as the supreme teacher of the universal Church, in whom the charism of infallibility of the Church itself is individually present, he is expounding or defending a doctrine of Catholic faith. The infallibility promised to the Church resides also in the body of Bishops, when that body exercises the supreme magisterium with the successor of Peter. To these definitions the assent of the Church can never be wanting, on account of the activity of that same Holy Spirit, by which the whole flock of Christ is preserved and progresses in unity of faith.[193]

On 11 October 2012, on the occasion of the 50th anniversary of the opening of the Second Vatican Council 60 prominent theologians, (including Hans Küng), put out a Declaration, stating that the intention of Vatican II to balance authority in the Church has not been realized. "Many of the key insights of Vatican II have not at all, or only partially, been implemented... A principal source of present-day stagnation lies in misunderstanding and abuse affecting the exercise of authority in our Church."[194]

Politics and functions of the Holy See

[edit] |

| This article is part of a series on |

| Vatican City |

|---|

Residence and jurisdiction

[edit]The pope's official seat is in the Archbasilica of Saint John Lateran, considered the cathedral of the Diocese of Rome.

The pope's official residence is the Apostolic Palace. He also possesses a summer residence at Castel Gandolfo, situated on the site of the ancient city of Alba Longa.

The names "Holy See" and "Apostolic See" are ecclesiastical terminology for the ordinary jurisdiction of the bishop of Rome, including the Roman Curia. The pope's honours, powers, and privileges within the Catholic Church and the international community derive from his Episcopate of Rome in lineal succession from the Saint Peter, one of the twelve apostles.[195]

Consequently, Rome has traditionally occupied a central position in the Catholic Church, although this is not necessarily so. The pope derives his pontificate from being the bishop of Rome but is not required to live there. According to the Latin formula ubi Papa, ibi Curia, wherever the pope resides is the central government of the Church. Between 1309 and 1378, the popes lived in Avignon, France,[196] a period often called the "Babylonian captivity" in allusion to the Biblical narrative of Jews of the ancient Kingdom of Judah living as captives in Babylonia.

Salary and benefits

[edit]As of 2024, the pope's salary was €30,000 per month.[197] Francis, a Jesuit, refused to collect a salary and donated the money to the poor.[197]

The Catholic Church traditionally covers the costs of all the pope's meals, housing, apparel, transport (e.g., the Popemobile), security, housekeeping, and healthcare.[197] The pope has free access to Vatican medical services and a private pharmacy.[197]

If a pope retires, the monthly pension as of 2024 was €2,500 per month.[197]

Citizenship and tax status

[edit]This section is empty. You can help by adding to it. (June 2025) |

Pastoral care of the Diocese of Rome

[edit]Although the pope is the diocesan bishop of Rome, he delegates most of the day-to-day work of leading the diocese to the cardinal vicar, who assures direct episcopal oversight of the diocese's pastoral needs, not in his own name but in that of the pope. The most recent cardinal vicar was Angelo De Donatis, who served from 2017 until 2024. The current cardinal vicar is Baldassare Reina.

This does not mean that popes ignore their diocesan responsibilities. For example, when Pope John XXIII announced his intention to establish the Second Vatican Council in 1959, his reflections dealt first with the state of the Catholic Church within Rome before "broadening his gaze to the entire world".[198]

Political role

[edit]| Sovereign of the Vatican City State | |

|---|---|

| |

| Incumbent | Pope Leo XIV |

| Style | His Holiness |

| Residence | Apostolic Palace |

| First Sovereign | Pope Pius XI |

| Formation | 11 February 1929 |

| Website | vaticanstate |

Though the progressive Christianization of the Roman Empire in the 4th century did not confer upon bishops civil authority within the state, the gradual withdrawal of imperial authority during the 5th century left the pope the senior imperial civilian official in Rome, as bishops were increasingly directing civil affairs in other cities of the Western Empire. This status as a secular and civil ruler was vividly displayed by Pope Leo I's confrontation with Attila in 452.

The first expansion of papal rule outside of Rome came in 728 with the Donation of Sutri. In 754, the Frankish ruler Pippin the Younger gave the pope the land from his conquest of the Lombards. The pope may have utilized the forged Donation of Constantine to gain this land, which formed the core of the Papal States. This document, accepted as genuine until the 15th century, states that Constantine the Great placed the entire Western Empire of Rome under papal rule.

In 800, Pope Leo III crowned the Frankish ruler Charlemagne as Roman emperor, a major step toward establishing what later became known as the Holy Roman Empire. From that date onward the popes claimed the prerogative to crown the emperor. The right fell into disuse after the coronation of Charles V in 1530. In 1804, Pius VII was present at the coronation of Napoleon I but did not actually perform the crowning. As mentioned above, the pope's sovereignty over the Papal States ended in 1870 with their annexation by Italy.

Popes like Alexander VI, an ambitious if spectacularly corrupt politician, and Julius II, a formidable general and statesman, were not afraid to use power to achieve their own ends, which included increasing the power of the papacy. This political and temporal authority was demonstrated through the papal role in the Holy Roman Empire, especially prominent during periods of contention with the emperors, such as during the pontificates of Pope Gregory VII and Pope Alexander III.

Papal bulls, interdict, and excommunication, or the threat thereof, have been used many times to exercise papal power. The bull Laudabiliter in 1155 authorized King Henry II of England to invade Ireland. In 1207, Innocent III placed England under interdict until King John made his kingdom a fiefdom to the pope, complete with yearly tribute, saying, "we offer and freely yield...to our lord Pope Innocent III and his catholic successors, the whole kingdom of England and the whole kingdom of Ireland with all their rights and appurtenences for the remission of our sins".[199]

The Bull Inter caetera in 1493 led to the Treaty of Tordesillas in 1494, which divided the world into areas of Spanish and Portuguese rule. The bull Regnans in Excelsis in 1570 excommunicated Queen Elizabeth I of England and declared that all her subjects were released from allegiance to her. The bull Inter gravissimas in 1582 established the Gregorian calendar.[200]

In recent decades, although the papacy has become less directly involved in politics, popes have nevertheless retained significant political influence. They have also served as mediators, with the support of the Catholic establishment.[201][202] John Paul II, a native of Poland, was regarded as influential in the fall of Communism in Eastern Europe.[203] He also mediated the Beagle conflict between Argentina and Chile, two predominantly Catholic countries.[204] In the 21st century, Francis played a role in brokering the 2015 improvement in relations between the United States and Cuba.[205][206]

International position

[edit]

Under international law, a serving head of state has sovereign immunity from the jurisdiction of the courts of other countries, though not from that of international tribunals.[207][208] This immunity is sometimes loosely referred to as "diplomatic immunity", which is, strictly speaking, the immunity enjoyed by the diplomatic representatives of a head of state. International law treats the Holy See, essentially the central government of the Catholic Church, as the juridical equal of a state. It is distinct from the state of Vatican City, existing for many centuries before the foundation of the latter.

It is common for publications and news media to use "the Vatican", "Vatican City", and even "Rome" as metonyms for the Holy See. Most countries of the world maintain the same form of diplomatic relations with the Holy See that they entertain with other states. Even countries without those diplomatic relations participate in international organizations of which the Holy See is a full member.

It is as head of the state-equivalent worldwide religious jurisdiction of the Holy See (not of the territory of Vatican City) that the U.S. Justice Department ruled that the pope enjoys head-of-state immunity.[209] This head-of-state immunity, recognized by the United States, must be distinguished from that envisaged under the United States' Foreign Sovereign Immunities Act of 1976, which, while recognizing the basic immunity of foreign governments from being sued in American courts, lays down nine exceptions, including commercial activity and actions in the United States by agents or employees of the foreign governments. It was in relation to the latter that, in November 2008, the United States Court of Appeals in Cincinnati decided that a case over sexual abuse by Catholic priests could proceed, provided the plaintiffs could prove that the bishops accused of negligent supervision were acting as employees or agents of the Holy See and were following official Holy See policy.[210][211][212]

In April 2010, there was press coverage in Britain concerning a proposed plan by atheist campaigners and a prominent barrister, Geoffrey Robertson, to have Pope Benedict XVI arrested and prosecuted in the UK for alleged offences, dating from several decades before, in failing to take appropriate action regarding Catholic sex abuse cases and concerning their disputing his immunity from prosecution in that country.[213] This was generally dismissed as "unrealistic and spurious".[214] Another barrister said that it was a "matter of embarrassment that a senior British lawyer would want to allow himself to be associated with such a silly idea".[215] Sovereign immunity does not apply to disputes relating to commercial transactions, and governmental units of the Holy See can face trial in foreign commercial courts. The first such trial to take place in the English courts is likely to occur in 2022 or 2023.[216][217]

Objections to the papacy

[edit]

The pope's claim to authority is either disputed or rejected outright by other churches, for various reasons.

Orthodox, Anglican and Old Catholic churches

[edit]Other traditional Christian churches (Assyrian Church of the East, the Oriental Orthodox Church, the Eastern Orthodox Church, the Old Catholic Church, the Anglican Communion, the Independent Catholic churches, etc.) accept the doctrine of Apostolic succession and, to varying extents, papal claims to a primacy of honour, while generally rejecting the pope as the successor to Peter in any other sense than that of other bishops. Primacy is regarded as a consequence of the pope's position as bishop of the original capital city of the Roman Empire, a definition spelled out in the 28th canon of the Council of Chalcedon. These churches see no foundation to papal claims of universal immediate jurisdiction, or to claims of papal infallibility. Several of these churches refer to such claims as ultramontanism.

Protestant denominations

[edit]In 1973, the United States Conference of Catholic Bishops' Committee on Ecumenical and Interreligious Affairs and the USA National Committee of the Lutheran World Federation in the official Catholic–Lutheran dialogue included this passage in a larger statement on papal primacy:

In calling the pope the "Antichrist", the early Lutherans stood in a tradition that reached back into the eleventh century. Not only dissidents and heretics but even saints had called the bishop of Rome the "Antichrist" when they wished to castigate his abuse of power. What Lutherans understood as a papal claim to unlimited authority over everything and everyone reminded them of the apocalyptic imagery of Daniel 11, a passage that even prior to the Reformation had been applied to the pope as the Antichrist of the last days.[218]

Protestant denominations of Christianity reject the claims of Petrine primacy of honour, Petrine primacy of jurisdiction, and papal infallibility. These denominations vary from rejecting the legitimacy of the pope's claim to authority, to believing that the pope is the Antichrist[219] from 1 John 2:18, the Man of Sin from 2 Thessalonians 2:3–12,[220] and the Beast out of the Earth from Revelation 13:11–18.[221]

This sweeping rejection is held by, among others, some denominations of Lutherans: Confessional Lutherans hold that the pope is the Antichrist, stating that this article of faith is part of a quia ("because") rather than quatenus ("insofar as") subscription to the Book of Concord. In 1932, one of these Confessional churches, the Lutheran Church–Missouri Synod (LCMS), adopted A Brief Statement of the Doctrinal Position of the Missouri Synod, which a small number of Lutheran church bodies now hold. The Lutheran Churches of the Reformation,[223] the Concordia Lutheran Conference,[224] the Church of the Lutheran Confession,[225] and the Illinois Lutheran Conference[226] all hold to the Brief Statement, which the LCMS places on its website.[227] The Wisconsin Evangelical Lutheran Synod (WELS), another Confessional Lutheran church that declares the Papacy to be the Antichrist, released its own statement, the "Statement on the Antichrist", in 1959. The WELS still holds to this statement.[228]

Historically, Protestants objected to the papacy's claim of temporal power over all secular governments, including territorial claims in Italy,[229] the papacy's complex relationship with secular states such as the Roman and Byzantine empires, and the autocratic character of the papal office.[230] In Western Christianity these objections both contributed to and are products of the Protestant Reformation.

Antipopes

[edit]Groups sometimes form around antipopes, who claim the Pontificate without being canonically and properly elected to it. Traditionally, this term was reserved for claimants with a significant following of cardinals or other clergy. The existence of an antipope is usually due either to doctrinal controversy within the Church (heresy) or to confusion as to who is the legitimate pope at the time (schism). Briefly in the 15th century, three separate lines of popes claimed authenticity.[231]

Other uses of the title "Pope"

[edit]In the earlier centuries of Christianity, the title "Pope", meaning "father", had been used by all bishops. Some popes used the term and others did not. Eventually, the title became associated especially with the bishop of Rome. In a few cases, the term is used for other Christian clerical authorities. In English, Catholic priests are still addressed as "father", but the term "pope" is reserved for the head of the church hierarchy.

In the Catholic Church

[edit]"Black Pope" is a name that was popularly, but unofficially, given to the superior general of the Society of Jesus due to the Jesuits' importance within the Church. This name, based on the black colour of his cassock, was used to suggest a parallel between him and the "White Pope" (since in the time of Pius V the pope dressed in white) and the cardinal prefect of the Congregation for the Evangelization of Peoples (formerly called the Sacred Congregation for the Propagation of the Faith), whose red cardinal's cassock gave him the name of the "Red Pope" in view of the authority over all territories that were not considered in some way Catholic. In the present time this cardinal has power over mission territories for Catholicism, essentially the Churches of Africa and Asia,[232] but in the past his competence extended also to all lands where Protestants or Eastern Christianity was dominant. Some remnants of this situation remain, with the result that, for instance, New Zealand is still in the care of this Congregation.

In the Eastern Churches

[edit]Since the papacy of Heraclas in the 3rd century, the bishop of Alexandria in both the Coptic Orthodox Church and the Greek Orthodox Church of Alexandria continues to be called "pope", the former being called "Coptic pope" or, more properly, "Pope and Patriarch of All Africa on the Holy Orthodox and Apostolic Throne of Saint Mark the Evangelist and Holy Apostle" and the latter called "Pope and Patriarch of Alexandria and All Africa".[233]

In the Bulgarian Orthodox Church, Russian Orthodox Church, Serbian Orthodox Church and Macedonian Orthodox Church, it is not unusual for a village priest to be called a "pope" ("поп" pop). This is different from the words used for the head of the Catholic Church (Bulgarian "папа" papa, Russian "папа римский" papa rimskiy).

In new religious movements and other Christian-related new religious movements

[edit]Some new religious movements within Christianity, especially those that have disassociated themselves from the Catholic Church yet retain a Catholic hierarchical framework, have used the designation "pope" for a founder or current leader. Examples include the African Legio Maria Church and the European Palmarian Catholic Church in Spain. The Cao Dai, a Vietnamese faith that duplicates the Catholic hierarchy, is similarly headed by a pope.

Lengths of papal reign

[edit]Longest-reigning popes

[edit]

The longest papal reigns of those whose reign lengths can be determined from contemporary historical data are the following:

- Saint Peter (c. 30–64/68): c. 34 – c. 38 years (Around 12,000–14,000 days)[234]

- Bl. Pius IX (1846–1878): 31 years, 7 months and 23 days (11,560 days)

- St. John Paul II (1978–2005): 26 years, 5 months and 18 days (9,665 days)

- Leo XIII (1878–1903): 25 years, 5 months and 1 day (9,281 days)

- Pius VI (1775–1799): 24 years, 6 months and 15 days (8,962 days)

- Adrian I (772–795): 23 years, 10 months and 25 days (8,729 days)

- Pius VII (1800–1823): 23 years, 5 months and 7 days (8,560 days)

- Alexander III (1159–1181): 21 years, 11 months and 24 days (8,029 days)

- St. Sylvester I (314–335): 21 years, 11 months and 1 day (8,005 days)

- St. Leo I (440–461): 21 years, 1 month, and 13 days (7,713 days)

During the Western Schism, Avignon Pope Benedict XIII (1394–1423) ruled for 28 years, 7 months and 12 days, which would place him third in the above list. Since he is regarded as an anti-pope, he is not included there.

Shortest-reigning popes

[edit]

There have been a number of popes whose reign lasted about a month or less. In the following list the number of calendar days includes partial days. Thus, for example, if a pope's reign commenced on 1 August and he died on 2 August, this counts as reigning for two calendar days.

- Urban VII (15–27 September 1590): reigned for 13 calendar days, died before coronation.

- Boniface VI (April 896): reigned for 16 calendar days

- Celestine IV (25 October – 10 November 1241): reigned for 17 calendar days, died before coronation.

- Theodore II (December 897): reigned for 20 calendar days

- Sisinnius (15 January – 4 February 708): reigned for 21 calendar days

- Marcellus II (9 April – 1 May 1555): reigned for 23 calendar days

- Damasus II (17 July – 9 August 1048): reigned for 24 calendar days

- Pius III (22 September – 18 October 1503) and Leo XI (1–27 April 1605): both reigned for 27 calendar days