Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Śrauta

View on Wikipedia

| Part of a series on |

| Hinduism |

|---|

|

Śrauta (Sanskrit: श्रौत) is a Sanskrit word that means "belonging to śruti", that is, anything based on the Vedas of Hinduism.[1][2] It is an adjective and prefix for texts, ceremonies or person associated with śruti.[3] The term, for example, refers to Brahmins who specialise in the śruti corpus of texts,[4] and Śrauta Brahmin traditions in modern times can be seen in Kerala and Coastal Andhra.[5]

Etymology and meaning

[edit]The Sanskrit word śrauta is rooted in śruti ("that which is heard", referring to scriptures of Hinduism). Johnson says that śrauta is an adjective that is applied to a text, a ritual practice, or a person, that is associated with śruti.[3] Klostermaier concurs, stating that the prefix means "belonging to śruti", and includes ceremonies and texts related to śruti.[1] The word is sometimes spelled shrauta in scholarly literature.[6][7]

History

[edit]Spread via Indian religions, homa traditions are found all across Asia, from Samarkand to Japan, over a 3000-year history.[8] A homa, in all its Asian variations, is a ceremonial ritual that offers food to fire and is ultimately descended from the Vedic religion.[8] The tradition reflects a ritual eclecticism for fire and cooked food (Paka-yajna) that developed in Indian religions, and the Brahmana layers of the Vedas are the earliest surviving records of this.[9]

Yajna or vedic fire sacrifice ritual, in Indian context, became a distinct feature of the early śruti (Vedic) rituals.[8] A śrauta ritual is a form of quid pro quo where through the fire ritual, a sacrificer offered something to the gods, and the sacrificer expected something in return.[10][11] The Vedic ritual consisted of sacrificial offerings of something edible or drinkable,[12] such as milk, clarified butter, yoghurt, rice, barley, an animal, or anything of value, offered to the gods with the assistance of fire priests.[13][14] This Vedic tradition split into Śrauta (śruti-based) and Smarta (Smriti-based).[8]

The Śrauta rituals, states Michael Witzel, are an active area of study and are incompletely understood.[15]

Śrauta "fire ritual" practices were copied by different Buddhist and Jain traditions, states Phyllis Granoff, with their texts appropriating the "ritual eclecticism" of Hindu traditions, albeit with variations that evolved through the medieval times.[8][16][17] The homa-style Vedic sacrifice ritual, states Musashi Tachikawa, was absorbed into Mahayana Buddhism and homa rituals continue to be performed in some Buddhist traditions in Tibet, China and Japan.[18][19]

Texts

[edit]| Veda | Sutras |

| Rigveda | Asvalayana-sutra (§), Sankhayana-sutra (§), Saunaka-sutra (¶) |

| Samaveda | Latyayana-sutra (§), Drahyayana-sutra (§), Nidana-sutra (§), Pushpa-sutra (§), Anustotra-sutra (§)[21] |

| Yajurveda | Manava-sutra (§), Bharadvaja-sutra (¶), Vadhuna-sutra (¶), Vaikhanasa-sutra (¶), Laugakshi-sutra (¶), Maitra-sutra (¶), Katha-sutra (¶), Varaha-sutra (¶), Apastamba-sutra (§), Baudhayana-sutra (§)[22] |

| Atharvaveda | Kusika-sutra (§) |

| ¶: only quotes survive; §: text survives | |

Śrautasūtras are ritual-related sutras based on the śruti. The first versions of the Kalpa (Vedanga) sutras were probably composed by the sixth century BCE, starting about the same time as the Brahmana layer of the Vedas were composed and most ritual sutras were complete by around 300 BCE.[23] They were attributed to famous Vedic sages in the Hindu tradition.[24] These texts are written aphoristic sutras style, and therefore are taxonomies or terse guidebooks rather than detailed manuals or handbooks for any ceremony.[25]

The Śrautasūtras differ from the smārtasūtra based on smṛti (that which is remembered, traditions).[26] The Smartasutras, in ancient vedic and post-vedic literature, typically refer to the gṛhyasūtras (householder's rites of passage) and sāmayācārikasūtras (right way to live one's life with duties to self and to relationships with others, dharmaśāstras).[26][27]

Śrauta Sutras

[edit]

The Śrautasūtras form a part of the corpus of Sanskrit sutra literature. Their topics include instructions relating to the use of the śruti corpus in great rituals and the correct performance of these major vedic ceremonies, are same as those found in the Brahmana layers of the Vedas, but presented in more systematic and detailed manner.[29]

Definition of a Vedic sacrifice

Yajña, sacrifice, is an act by which we surrender something for the sake of the gods. Such an act must rest on a sacred authority (āgama), and serve for man's salvation (śreyortha). The nature of the gift is of less importance. It may be cake (puroḍāśa), pulse (karu), mixed milk (sāṃnāyya), an animal (paśu), the juice of soma-plant (soma), etc; nay, the smallest offerings of butter, flour, and milk may serve for the purpose of a sacrifice.

— Apastamba Yajna Paribhasa-sutras 1.1, Translator: M Dhavamony[14][30]

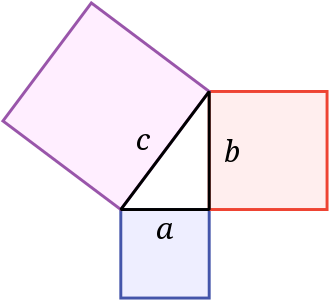

Baudhayana srautasutra is probably the oldest text in the śrautasūtra genre, and includes in its appendix a paribhāṣāsūtra (definitions, glossary section).[31] Other texts such as the early Apastamba śrautasūtra and later composed Katyayana start with Paribhasa-sutra section.[31] The śulbasūtras or śulvasūtras are appendices in the śrautasūtras and deal with the mathematical methodology to construct geometries for the vedi (Vedic altar).[32] The Sanskrit word śulba means "cord", and these texts are "rules of the cord".[33] They provide, states Kim Plofker, what in modern mathematical terminology would be called "area preserving transformations of plane figures", tersely describing geometric formulae and constants.[33] Five śulbasutras have survived through history, of which the oldest surviving is likely the Baudhayāna śulbasūtra (800–500 BCE), while the one by Kātyāyana may be chronologically the youngest (≈300 BCE).[34]

Rituals

[edit]Śrauta rituals and ceremonies refer to those found in the Brahmana layers of the Vedas. These include rituals related to fire, full moon, new moon, soma, animal sacrifice, as well as seasonal offerings made during Vedic times.[35] These rituals and ceremonies in the Brahmanas texts are mixed and difficult to follow. A clearer description of the ritual procedures appeared in the Vedanga Kalpa-sutras.[36]

The Vedic rituals, states Burde, can be "divided into Śrauta and Gṛhya rituals".[37] Śrauta rites relating to public ceremonies were relegated to the Śrautasutras, while most Vedic rituals relating to rites of passage and household ceremonies were incorporated in the Gṛhyasūtras (literally, homely; also called Laukika or popular, states Lubin).[8][38] However, the Gṛhyasūtras also added many new non-Śrauta ceremonies over time.[8] The śrautasūtras generally focus on large expensive public ceremonies, while gṛhyasūtras focus on householders and saṃskāras (rites of passage) such as childbirth, marriage, renunciation and cremation.[36][2][37]

The śrautasūtra ceremonies are usually elaborate and require the services of multiple priests,[2] while gṛhyasūtra rituals can be performed without or with the assistance of a priest in the Hindu traditions.[39][40]

Animal versus vegetarian sacrificial offerings

[edit]The Śrauta rituals varied in complexity. The first step of a Śrauta ritual was making of an altar, then the initiation of fire, next of Havir-yajnas recitations, then offering of milk or drinkable liquid drops into the fire, then prayers all with mantras.[41]

More complex Śrauta rituals were based on moon's cycle (Darshapurnamasa) and the seasonal rituals.[41] The lunar cycle Śrauta sacrifices had no animal sacrifices, offered a Purodasha (baked grain cake) and Ghee (clarified butter) as an offering to gods, with recitation of mantras.[42]

According to Witzel, "the Pasubandha or "Animal Sacrifice" is also integrated into the Soma ritual, and involves the killing of an animal." The killing was considered inauspicious, and "bloodless" suffocation of the animal outside the offering grounds was practiced.[38] The killing was viewed as a form of evil and pollution (papa, agha, enas), and reforms were introduced to avoid this evil in late/post-Rigvedic times.[43] According to Timothy Lubin, the substitution of animal sacrifice in Śrauta ritual with shaped dough (pistapasu) or pots of ghee (ajyapasu) has been practiced for at least 600 years, although such a substitution is not condoned in Śrauta ritual texts.[44]

'Shatapatha Brahmana section 1.2.3 of the Yajurveda is generally misinterpreted by modern day indologists as transition from animals to vegetarian offering. However a very careful examination of these verses reveal that these are not vegetarian substitutes for the entire animal but only for those animal organs not offered in fire. Further not a single commentator from mimamsa or vaishnava traditions have talked about any vegetarian substitutes and hence it is clear that vedic animal sacrifices continued as late as 21st century

Decline

[edit]According to Alexis Sanderson, Śrauta ceremonies declined from the fifth to the thirteenth century CE.[45] This period saw a shift from Śrauta sacrifices to charitable grant of gifts such as giving cows, land, issuing endowments to build temples and sattrani (feeding houses), and water tanks as part of religious ceremonies.[46][47]

Contemporary practices

[edit]Most Śrauta rituals are rarely performed in the modern era.[48] Some Śrauta traditions have been observed and studied by scholars, as in the rural parts of Andhra Pradesh, and elsewhere in India and Nepal.[49] Śrauta traditions from Coastal Andhra have been reported by David Knipe,[5] and an elaborate śrauta ceremony was video recorded in Kerala by Frits Staal in 1975.[50] According to Axel Michaels, the homa sacrifice rituals found in modern Hindu and Buddhist contexts evolved as a simpler version of the Vedic Śrauta ritual.[48]

Knipe has published a book on Śrauta practices from rural Andhra. The Śrauta ritual system, states Knipe, "is an extended one, in the sense that a simple domestic routine has been replaced by one far more demanding on the religious energies of the sacrificer and his wife," and is initiated by augmenting a family's single fire Grihya system to a three fire Śrauta system.[51] The community that continues to teach the Śrauta tradition to the next generation also teaches the Smarta tradition, the choice left to the youth.[52] The Andhra tradition may be, states Knipe, rooted in the ancient Apstamba Śrauta and Grihya Sutras.[53] In the Andhra traditions, after one has established the routine of the twice-daily routine of agnihotra offerings and biweekly dara pūrṇamāsa offerings, one is eligible to perform the agniṣṭoma, the simplest soma rite.[49] After the agniṣṭoma, one is eligible to perform more extensive soma rites and agnicayana rites.[54]

The first soma Śrauta ritual to be conducted outside of South Asia was in London, the United Kingdom in 1996 by a Puṣṭimārga mahārāj who employed south Indian priests. The sacrifice was described by Smith to be a "ludicrous debacle" in terms of adherence to ritual rules.[55]

Śrauta brahmins specialise in conducting rituals according to the śruti corpus of texts, in contrast to smarta brahmins, known for conducting rituals according to smriti texts.[4][56]

Defunct practices

[edit]The Ashvamedha and Rajasuya are not practiced anymore.[57] There is doubt the Purushamedha, a human sacrifice, was ever performed.[57][58]

Influence

[edit]The Śrauta rituals were complex and expensive, states Robert Bellah, and "we should not forget that the rites were created for royalty and nobility".[59] A Brahmin, adds Bellah, would need to be very rich to sponsor and incur the expense of an elaborate Śrauta rite.[59] In ancient times, through the middle of 1st millennium CE, events such as royal consecration sponsored the Śrauta rites, and thereafter they declined as alternative rites such as temple and philanthropic actions became more popular with the royalty.[60]

The Upanishads, states Brian Smith, were a movement towards the demise of the Śrauta-style social rituals and the worldview these rites represented.[61] The Upanishadic doctrines were not a culmination, but a destruction of Vedic ritualism.[61] This had a lasting influence on the Indian religions that gained prominence in the 1st millennium BCE, not only in terms of the Vedanta and other schools of Hindu philosophy that emerged, but also in terms of Buddhist and Jaina influence among the royal class of the ancient Indian society.[61]

In the Upanishads, one might be witnessing the conclusion of Vedism, not in the sense of its culmination but in the sense of its destruction. In the proto-Vedantic view, the universe and ritual order based on resemblance has collapsed, and a very different configuration based on identity has emerged. Upanishadic monism, one might say, blew the lid off a system contained, as well as regulated, by hierarchical resemblance. The formulation of a monistic philosophy of ultimate identity – arguably one indication of Vedism dissipating and reforming into a new systematic vision of the world and its fundamental principles – was born outside the normative classification schema of Vedic social life and became institutionalized as a counterpoint to life in the world.[61]

With time, scholars of ancient India composed Upanishads, such as the Pranagnihotra Upanishad, that evolved the focus from external rituals to self-knowledge and to inner rituals within man. The Pranagnihotra is, states Henk Bodewitz, an internalized direct private ritual that substituted external public Agnihotra ritual (a srauta rite).[62]

This evolution hinged on the Vedic idea of devas (gods) referring to the sense organs within one's body, and that the human body is the temple of Brahman, the metaphysical unchanging reality. This principle is found in many Upanishads, including the Pranagnihotra Upanishad, the Brihadaranyaka Upanishad section 2.2,[63] Kaushitaki Upanishad sections 1.4 and 2.1–2.5,[64] Prasna Upanishad chapter 2,[65][66] and others.[67] The idea is also found and developed by other minor Upanishads such as the ancient Brahma Upanishad which opens by describing human body as the "divine city of Brahman".[67]

Bodewitz states that this reflects the stage in ancient Indian thought where "the self or the person as a totality became central, with the self or soul as the manifestation of the highest principle or god".[68] This evolution marked a shift in spiritual rite from the external to the internal, from public performance through srauta-like rituals to performance in thought through introspection, from gods in nature to gods within.[68]

The Śrauta Agnihotra sacrifice thus evolved into Prana-Agnihotra sacrifice concept. Heesterman describes the pranagnihotra sacrifice as one where the practitioner performs the sacrifice with food and his own body as the temple, without any outside help or reciprocity, and this ritual allows the Hindu to "stay in the society while maintaining his independence from it", its simplicity thus marks the "end station of Vedic ritualism".[69]

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ a b Klostermaier, Klaus K. (2014). A Concise Encyclopedia of Hinduism. Oneworld Publications. p. 198. ISBN 978-1-78074-672-2.

- ^ a b c Frits Staal (2008). Discovering the Vedas: Origins, Mantras, Rituals, Insights. Penguin Books. pp. 123–127, 224–225. ISBN 978-0-14-309986-4.

- ^ a b Johnson, W.J. (2010). "Śrauta". A Dictionary of Hinduism. Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/acref/9780198610250.001.0001. ISBN 978-0-19-861026-7.

- ^ a b Flood 2006, p. 8.

- ^ a b Knipe 2015, p. 1-246.

- ^ "Shrauta sutra". Encyclopædia Britannica. 2015.

- ^ Patton, Laurie L. (2005). "Can women be priests? Brief notes toward an argument from the ancient Hindu world". Journal of Hindu-Christian Studies. 18 (1): 17. doi:10.7825/2164-6279.1340.

- ^ a b c d e f g Timothy Lubin (2015). Michael Witzel (ed.). Homa Variations: The Study of Ritual Change Across the Longue Durée. Oxford University Press. pp. 143–166. ISBN 978-0-19-935158-9.

- ^ Timothy Lubin (2015). Michael Witzel (ed.). Homa Variations: The Study of Ritual Change Across the Longue Durée. Oxford University Press. pp. 143–145, 148. ISBN 978-0-19-935158-9., Quote: "The homa, the ritual offering of food in a fire, has had a prolific career in Asia over the course of more than three millennia. In various forms, rites of this type have become a part of most of the religions that arose in India as well as their extensions and offsprings from Samarqand to Japan. All of these homas ultimately descend from those of the Vedic religions, but at no point has the homa been stable. (...) The rules of Vedic fire offerings have come down to us in two parallel systems. A few of the later exegetical passages (brahmana) in the Vedas refer to cooked food (paka) offerings contrasted with the multiple-fire ritual otherwise being prescribed. (...) several ways in which a homa employing a cooked offering (pakayajana) can be distinguished from a Srauta offering (...)"

- ^ Richard Payne (2015). Michael Witzel (ed.). Homa Variations: The Study of Ritual Change Across the Longue Durée. Oxford University Press. pp. 2–3. ISBN 978-0-19-935158-9.

- ^ Michael Witzel (2008). Gavin Flood (ed.). The Blackwell Companion to Hinduism. John Wiley & Sons. p. 78. ISBN 978-0-470-99868-7.

- ^ Michael Witzel (2008). Gavin Flood (ed.). The Blackwell Companion to Hinduism. John Wiley & Sons. p. 79. ISBN 978-0-470-99868-7.

- ^ Sushil Mittal; Gene Thursby (2006). Religions of South Asia: An Introduction. Routledge. pp. 65–66. ISBN 978-1-134-59322-4.

- ^ a b M Dhavamony (1974). Hindu Worship: Sacrifices and Sacraments. Studia Missionalia. Vol. 23. Gregorian Press, Universita Gregoriana, Roma. pp. 107–108.

- ^ Michael Witzel (2008). Gavin Flood (ed.). The Blackwell Companion to Hinduism. John Wiley & Sons. p. 77. ISBN 978-0-470-99868-7.

Quote: A thorough interpretation of the Śrauta ritual that uses a wealth of Vedic descriptions and contemporaneous native interpretation is a desideratum. Though begun a hundred years ago (...), a comprehensive interpretation still is outstanding.

- ^ Phyllis Granoff (2000), Other people's rituals: Ritual Eclecticism in early medieval Indian religious, Journal of Indian Philosophy, Volume 28, Issue 4, pages 399–424

- ^ Christian K. Wedemeyer (2014). Making Sense of Tantric Buddhism: History, Semiology, and Transgression in the Indian Traditions. Columbia University Press. pp. 163–164. ISBN 978-0-231-16241-8.

- ^ Musashi Tachikawa; S. S. Bahulkar; Madhavi Bhaskar Kolhatkar (2001). Indian Fire Ritual. Motilal Banarsidass. pp. 2–3, 21–22. ISBN 978-81-208-1781-4.

- ^ Musashi Tachikawa (2015). Michael Witzel (ed.). Homa Variations: The Study of Ritual Change Across the Longue Durée. Oxford University Press. pp. 126–141. ISBN 978-0-19-935158-9.

- ^ Max Muller, History of Ancient Sanskrit Literature, Oxford University Press, pages 198–199

- ^ Max Muller, History of Ancient Sanskrit Literature, Oxford University Press, page 210

- ^ Knipe 2015, p. 37.

- ^ Brian Smith 1998, p. 120 with footnote 1.

- ^ James Lochtefeld (2002), "Kalpa" in The Illustrated Encyclopedia of Hinduism, Vol. 1: A-M, Rosen Publishing, ISBN 0-8239-2287-1, page 339

- ^ Brian Smith 1998, pp. 120–137 with footnotes.

- ^ a b Friedrich Max Müller (1860). A History of Ancient Sanskrit Literature. Williams and Norgate. pp. 200–201.

- ^ P. Holler (1901). The Student's Manual of Indian-Vedic-Sanskrit-Prakrut-Pali Literature. Kalavati. pp. ii–iii.

- ^ Kim Plofker 2009, p. 18 with note 13.

- ^ Brian Smith 1998, pp. 138–139 with footnote 62.

- ^ Jan Gonda (1980). Handbuch Der Orientalistik: Indien. Zweite Abteilung. BRILL Academic. pp. 345–346. ISBN 978-90-04-06210-8.

- ^ a b Brian Smith 1998, p. 123 with footnotes.

- ^ Pradip Kumar Sengupta (2010). History of Science and Philosophy of Science. Pearson. pp. 79–80. ISBN 978-81-317-1930-5.

- ^ a b Kim Plofker 2009, p. 17.

- ^ Kim Plofker 2009, pp. 17–18.

- ^ Maurice Winternitz 1963, p. 253.

- ^ a b Maurice Winternitz 1963, pp. 252–262.

- ^ a b Jayant Burde (1 January 2004). Rituals, Mantras, and Science: An Integral Perspective. Motilal Banarsidass. pp. 21–23. ISBN 978-81-208-2053-1.

- ^ a b Michael Witzel (2008). Gavin Flood (ed.). The Blackwell Companion to Hinduism. John Wiley & Sons. p. 80. ISBN 978-0-470-99868-7.

- ^ Muralidhar Shrinivas Bhat (1987). Vedic Tantrism: A Study of R̥gvidhāna of Śaunaka with Text and Translation. Motilal Banarsidass. p. 13. ISBN 978-81-208-0197-4.

- ^ Brian Smith 1998, p. 137-142 with footnotes.

- ^ a b Michael Witzel (2008). Gavin Flood (ed.). The Blackwell Companion to Hinduism. John Wiley & Sons. p. 80. ISBN 978-0-470-99868-7.

- ^ Usha Grover (1994). Pierre-Sylvain Filliozat; et al. (eds.). Pandit N.R. Bhatt Felicitation Volume 1. Motilal Banarsidass. pp. 59–61. ISBN 978-81-208-1183-6.

- ^ Michael Witzel (2008). Gavin Flood (ed.). The Blackwell Companion to Hinduism. John Wiley & Sons. p. 82. ISBN 978-0-470-99868-7.

- ^ Timothy Lubin (2015). Michael Witzel (ed.). Homa Variations: The Study of Ritual Change Across the Longue Durée. Oxford University Press. p. 153. ISBN 978-0-19-935158-9.

- ^ Sanderson, Alexis (2009). "The Śaiva Age: The Rise and Dominance of Śaivism during the Early Medieval Period (University of Tokyo Institute of Oriental Culture Special Series, 23)". In Einoo, Shingo (ed.). Genesis and Development of Tantrism. Tokyo: Institute of Oriental Culture. pp. 41–43.

- ^ Sanderson, Alexis (2009). "The Śaiva Age: The Rise and Dominance of Śaivism during the Early Medieval Period (University of Tokyo Institute of Oriental Culture Special Series, 23)". In Einoo, Shingo (ed.). Genesis and Development of Tantrism. Tokyo: Institute of Oriental Culture. pp. 268–269.

- ^ Nicholas Dirks (1976), Political Authority and Structural Change in Early South Indian History, Indian Economic and Social History Review, Volume 13, pages 144–157

- ^ a b Axel Michaels (2016). Homo Ritualis: Hindu Ritual and Its Significance for Ritual Theory. Oxford University Press. pp. 237–238. ISBN 978-0-19-026263-1.

- ^ a b Knipe 2015, pp. 41–49, 220–221.

- ^ Annette Wilke; Oliver Moebus (2011). Sound and Communication: An Aesthetic Cultural History of Sanskrit Hinduism. Walter de Gruyter. pp. 347–348 with footnote 17. ISBN 978-3-11-024003-0.

- ^ Knipe 2015, pp. 41–44.

- ^ Knipe 2015, pp. 35–36.

- ^ Knipe 2015, p. 32.

- ^ Knipe 2015, pp. 46–47, 220–233.

- ^ Smith, Frederick M. "Indra Goes West: Report on a Vedic Soma Sacrifice in London in July 1996". History of Religions. 39 (3).

- ^ William J. Jackson; Tyāgarāja (1991). Tyāgarāja: life and lyrics. Oxford University Press. p. 31. ISBN 978-0-19-562812-8.

- ^ a b Knipe 2015, p. 237.

- ^ Oliver Leaman (2006), Encyclopedia of Asian Philosophy, Routledge, ISBN 978-0415172813, page 557, Quote: "It should be mentioned that although provision is made for human sacrifice (purusha-medha) this was purely symbolic and did not involve harm to anyone".

- ^ a b Robert N. Bellah (2011). Religion in Human Evolution. Harvard University Press. pp. 499–501. ISBN 978-0-674-06309-9.

- ^ Sanderson, Alexis (2009). "The Śaiva Age: The Rise and Dominance of Śaivism during the Early Medieval Period (University of Tokyo Institute of Oriental Culture Special Series, 23)". In Einoo, Shingo (ed.). Genesis and Development of Tantrism. Tokyo: Institute of Oriental Culture. pp. 41–43, 268–270 with footnotes.

- ^ a b c d Brian Smith 1998, p. 195-196.

- ^ Henk Bodewitz (1997), Jaiminīya Brāhmaṇa I, 1–65: Translation and Commentary, Brill Academic, ISBN 978-9004036048, pp. 23, 230–233 with footnote 6

- ^ Brihadaranyaka Upanishad Robert Hume (Translator), Oxford University Press, pp. 96–97

- ^ Kausitaki Upanishad Robert Hume (Translator), Oxford University Press, pp. 302–303, 307–310, 327–328

- ^ Robert Hume, Prasna Upanishad, Thirteen Principal Upanishads, Oxford University Press, pp. 381

- ^ The Prasnopanishad with Sri Shankara's Commentary SS Sastri (Translator), pp. 118–119

- ^ a b Patrick Olivelle (1992), The Samnyasa Upanisads: Hindu Scriptures on Asceticism and Renunciation, Oxford University Press, ISBN 978-0195070453, pp. 147–151

- ^ a b Henk Bodewitz (1997), Jaiminīya Brāhmaṇa I, 1–65: Translation and Commentary, Brill Academic, ISBN 978-9004036048, pp. 328–329

- ^ Heesterman, J. C. (1985). The Inner Conflict of Tradition: Essays in Indian Ritual, Kingship, and Society. University of Chicago Press. ISBN 978-0-226-32299-5.

References

[edit]- Flood, Gavin (5 January 2006). The Tantric Body: The Secret Tradition of Hindu Religion. I.B.Tauris. ISBN 978-1-84511-011-6.

- Knipe, David M. (2 March 2015). Vedic Voices: Intimate Narratives of a Living Andhra Tradition. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-939770-9.

- Kim Plofker (2009). Mathematics in India. Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0-691-12067-6.

- Brian Smith (1998). Reflections on Resemblance, Ritual, and Religion. Motilal Banarsidass. ISBN 978-81-208-1532-2.

- Maurice Winternitz (1963). History of Indian Literature, Volume 1. Motilal Banarsidass. ISBN 978-8120802643.

{{cite book}}: ISBN / Date incompatibility (help)

External links

[edit]- Baudhayana Śrauta sutra Vol 1, W Caland, (in Sanskrit), Baptist Mission Press

- Baudhayana Śrauta sutra Vol 2, W Caland, (in Sanskrit), Baptist Mission Press

- Baudhayana Śrauta sutra Vol 3, W Caland, (in Sanskrit), Baptist Mission Press

- Apastamba Śrauta sutra, W Caland, (in German)

- Apastamba Śrauta sutra with commentary of Dhurtaswami, Narasimhachar, (in Sanskrit)

- Sankhayana Śrauta sutra with commentary of Anartiya Vol 2, Alfred Hillebrandt, (in Sanskrit)

- Sankhayana Śrauta sutra with commentary of Anartiya Vol 3, Alfred Hillebrandt, (in Sanskrit)

Śrauta

View on GrokipediaEtymology and Terminology

Derivation and Meaning

The term "Śrauta" derives from the Sanskrit root śru, meaning "to hear," which forms the basis of śruti, denoting the "heard" or revealed Vedic texts transmitted orally through divine inspiration.[3] This etymological connection underscores Śrauta's association with authoritative, unchanging scriptural tradition, as opposed to smṛti, the "remembered" texts composed by human authors and subject to interpretation.[4] In linguistic terms, "Śrauta" functions as an adjective derived from śruta (past participle of śru), emphasizing auditory reception and fidelity to the original Vedic revelation.[3] The primary meaning of "Śrauta" pertains to rituals, practices, and texts that adhere strictly to the prescriptions of the Śruti corpus, highlighting orthodoxy and direct conformity to Vedic injunctions.[4] It denotes sacrificial and ceremonial activities grounded in the sacred tradition, such as those involving the maintenance of sacred fires or communal offerings, which prioritize scriptural exactitude over later customary developments.[3] This semantic focus reinforces Śrauta's role in preserving the purity of Vedic ritualism, distinguishing it from more flexible, Smṛti-influenced domestic observances.[4] Historically, the term first appears in late Vedic texts, particularly the Brāhmaṇas, where it describes public, community-oriented sacrifices that embody collective religious obligations.[3] For instance, in the Śatapatha Brāhmaṇa, "Śrauta" qualifies elaborate rites like the Agnihotra, marking their alignment with revealed knowledge and priestly execution.[3] These early usages, emerging in the post-Ṛgvedic period, illustrate the term's evolution as a marker of ritual legitimacy within the broadening Vedic framework.[3]Key Terms in Śrauta Context

In the Śrauta tradition, yajña refers to a structured act of worship involving oblations offered into the sacred fire (Agni) to invoke divine favor and maintain cosmic order, distinct from mere prayer by its ritual precision and communal execution as outlined in the Vedic Śrauta Sūtras.[5] This term, derived from the root yaj meaning "to worship" or "to revere," encompasses both the physical offering and the socio-ritual framework that binds the sacrificer (yajamāna) to the deities.[5] Central to Śrauta yajñas are oblations known as havir, which consist of clarified butter (ghee), milk, grains, or barley cakes presented to the gods through the fire, serving as the foundational elements in haviryajña rituals that emphasize reciprocity between humans and divinities.[5] The iṣṭi, a basic form of haviryajña, involves vegetal or dairy offerings such as rice cakes or barley, performed with the aid of four priests and the sacrificer's wife, often as a standalone rite or embedded within larger sacrifices like the Darsa-Purnamasa.[6] In contrast, soma denotes both the sacred plant (an unidentified creeper) and its extracted juice, which is filtered and offered in elaborate somayajña rituals to invigorate the gods and the participants, marking a more complex category of Śrauta sacrifice.[6] A key distinction in Vedic ritual terminology lies between Śrauta and Gṛhya rites: Śrauta rituals, such as the Agniṣṭoma or Soma sacrifices, are public, multi-day ceremonies requiring specialized priests (ṛtvij) and communal participation to fulfill obligations derived from the Śruti, whereas Gṛhya rituals are simpler domestic observances focused on household life-cycle events like marriages or funerals, performed by the householder without priestly mediation.[5] For instance, the Darsa-Purnamasa iṣṭi in Śrauta texts involves congregational offerings at the new and full moon phases with Vedic chants, while its Gṛhya counterpart emphasizes family-based domestic purity rites.[6] This bifurcation underscores Śrauta's emphasis on collective cosmic maintenance rooted in the foundational Śruti texts.[5] The meanings of these terms evolved from the Rigveda to the Brāhmaṇas, reflecting a shift from spontaneous, poetic invocations to codified ritual systems. In the Rigveda, yajña denoted informal offerings for immediate divine aid, havir simple gifts like milk to deities such as Agni or Indra, iṣṭi ad hoc homas by householders, and soma a energizing plant-deity praised in hymns; by the Brāhmaṇas, these acquired layered cosmological significance—yajña as a cosmic drama sustaining ṛta (order), havir in structured Nitya rites like Agnihotra symbolizing dawn, iṣṭi formalized with priestly roles in monthly sacrifices, and soma integrated into elaborate Soma Yajñas with chants and symbolism for universal renewal.[1] This progression, evident in texts like the Śatapatha Brāhmaṇa, transformed Vedic terminology into a precise framework for Śrauta practice, prioritizing ritual efficacy over poetic flexibility.[1]Vedic Foundations

Connection to Śruti

The Śruti corpus, comprising the four Vedas—Ṛgveda, Sāmaveda, Yajurveda, and Atharvaveda—along with their subdivisions of Saṃhitās (hymn collections), Brāhmaṇas (ritual explications), Āraṇyakas (esoteric interpretations), and Upaniṣads (philosophical discourses), serves as the infallible scriptural foundation for Śrauta practices.[7] These texts form the Karma-Kāṇḍa (ritual portion) of the Vedas, where the Saṃhitās provide the mantras recited during ceremonies and the Brāhmaṇas detail their procedural applications, rendering Śrauta rituals a direct enactment of this revealed knowledge.[7] The Āraṇyakas and Upaniṣads, while more contemplative, reinforce the ritual framework by bridging ceremonial action with deeper metaphysical insights, ensuring the holistic authority of Śruti in guiding Śrauta observances.[8] Doctrinally, Śrauta rituals function as mechanisms to sustain ṛta, the cosmic order encompassing natural, moral, and sacrificial harmony, through the verbatim recitation of Vedic hymns that invoke deities and align human conduct with universal principles.[8] In this system, sacrifices such as the Agnihotra or Soma offerings, prescribed in the Brāhmaṇas, restore equilibrium when ṛta is disrupted, with precise mantra intonation from the Saṃhitās—particularly in the Ṛgveda and Sāmaveda—acting as vibrational conduits to perpetuate this order.[9] The hymns, personifying ṛta through figures like Varuṇa, underscore the rituals' role in ethical and cosmic maintenance, where deviation from textual prescriptions could invite disorder.[8] Central to Śruti's authority in Śrauta is its apaurusheya quality, denoting an authorless, eternal origin independent of human or divine composition, manifested as self-evident truths "heard" by ancient ṛṣis in states of heightened perception.[10] This revelation to the ṛṣis, as articulated in Mīmāṃsā and Advaita traditions, positions Śruti not as authored doctrine but as primordial sound (śabda) with inherent efficacy, directly informing the ritual precision required in Śrauta without intermediary interpretation.[10] Consequently, Śrauta Sūtras, such as the Āpastamba Śrauta Sūtra, derive their validity solely from this uncreated Śruti, serving as mnemonic aids to its application.[11]Role in Vedic Cosmology

In Vedic cosmology, Śrauta sacrifices function as microcosmic recreations of the primordial creation myths, wherein human rituals symbolically reenact the divine act of generation to link earthly actions with celestial realms. Central to this is the myth of Prajāpati, the cosmic progenitor, who initiates creation through his own self-sacrifice, dispersing his essence to form the universe and its elements.[12] This foundational event, detailed in Vedic exegesis, positions the Śrauta yajña as a participatory renewal of that generative process, allowing performers to align mortal endeavors with the ongoing cosmic order. By emulating Prajāpati's dismemberment and offering, the ritual bridges the microcosm of the human sphere and the macrocosm of divine existence, ensuring continuity between the two.[13] A core concept in this framework is the reciprocity established through yajña between humans and the devas, the divine powers, which sustains dharma—the ethical and natural law—and averts primordial chaos. Offerings channeled via the sacrifice nourish the devas, who in return bestow prosperity, fertility, and stability upon the world, thereby upholding ṛta, the intrinsic cosmic order that governs seasonal cycles, moral conduct, and universal harmony. This exchange is not merely transactional but essential for preventing dissolution (pralaya), as unfulfilled reciprocity would disrupt the delicate balance of existence, echoing the Vedic principle that ritual action mirrors and reinforces the devas' primordial pacts.[8] As referenced in Śruti hymns, this dynamic underscores yajña's role in perpetuating an ordered cosmos against entropic forces.[14] Symbolically, fire (Agni) serves as the primary mediator in Śrauta rituals, facilitating communication between the terrestrial and heavenly domains while embodying the transformative energy of creation. Agni, invoked as the divine messenger, conveys oblations upward to the devas and draws their presence downward, symbolizing the vertical axis connecting earth, atmosphere, and sky.[15] Complementing this is the ritual geometry of the vedi (altar), meticulously constructed to replicate the universe's structure—its layers and orientations mirroring the tripartite cosmic realms (earth, midspace, heaven) and the directional expanse of the world.[16] This architectural symbolism, governed by precise proportions in the Śulba Sūtras, reinforces the ritual's cosmological efficacy, transforming the physical space into a homologous model of the cosmos itself.[17]Primary Texts

Śrauta Sūtras Overview

The Śrauta Sūtras constitute a genre of ancient Indian ritual texts composed in a highly concise, aphoristic style known as sūtra format, designed for ease of memorization and oral transmission among Vedic priests. This terse composition focuses on the intricate procedural details of Vedic sacrifices, including minutiae such as the precise construction of altars, the sequencing of ritual chants, and the coordination of priestly actions to ensure ritual efficacy.[18] Unlike more narrative Vedic texts, these sūtras prioritize practical taxonomy over elaboration, serving as essential handbooks for performing complex śrauta rites.[18] Their primary purpose was to codify longstanding oral traditions of sacrificial performance into a more systematic written form, thereby bridging the explanatory discussions of the Vedic Brāhmaṇas with actual priestly practice. Composed primarily between c. 800 and 400 BCE, spanning the late Vedic and early post-Vedic periods, these texts reflect a transitional phase in Vedic literature, standardizing rituals that had evolved from earlier oral customs to support both communal and royal ceremonies. Composition dates vary, with earlier texts like the Baudhāyana dating to around 800–650 BCE and later ones extending into the post-Vedic era.[3] By distilling ritual knowledge into rules, the Śrauta Sūtras enabled priests to maintain orthodoxy amid growing ritual complexity, preserving the sacred efficacy attributed to proper execution.[18] In terms of structure, the Śrauta Sūtras are typically organized into chapters called paṭalas, each addressing distinct phases of the sacrificial process from initial preparations—such as site selection and material gathering—to the core execution of offerings and concluding rites like dispersal of remnants. These paṭalas often subdivide further into smaller units like khaṇḍas for granular instructions, ensuring comprehensive coverage without redundancy. This modular format facilitated targeted reference during live rituals, underscoring the texts' role as operational manuals rather than theoretical treatises.[18]Major Śrauta Texts by Veda

The Śrauta Sūtras associated with the Rigveda primarily include the Āśvalāyana Śrauta Sūtra and the Śāṅkhāyana Śrauta Sūtra, both of which belong to the Śākala and Kauṣītaki branches, respectively, and emphasize the recitation of Rigvedic hymns by the Hotṛ priest during Soma sacrifices.[3] These texts provide detailed instructions on the integration of poetic verses into ritual sequences, highlighting the centrality of hymn-based invocations in maintaining cosmic order.[3] For the Yajurveda, the major Śrauta Sūtras differ between its Black and White traditions: the Āpastamba and Baudhāyana Śrauta Sūtras pertain to the Taittirīya śākhā of the Black Yajurveda, while the Kātyāyana Śrauta Sūtra aligns with the Vājasaneyī śākhā of the White Yajurveda.[3] These works, particularly those of the Black tradition, offer extensive descriptions of fire altar constructions such as the Agnicayana, underscoring the Adhvaryu's role in prosaic formulas and procedural exactitude.[3] The Samaveda tradition features the Lāṭyāyana Śrauta Sūtra and the Jaiminīya Śrauta Sūtra, which focus on the melodic chanting of Sāmaveda verses by the Udgātṛ priest in Soma rituals.[3] These sūtras detail the musical notations and intonations essential to the chanting priests' duties, adapting Rigvedic hymns into sung forms for enhanced ritual efficacy.[19] Śrauta-specific texts for the Atharvaveda are limited, with the Vaitāna Sūtra serving as the primary example, outlining rituals involving the Brahman priest's recitations in contexts like royal consecration ceremonies.[3] Unlike the other Vedas, Atharvavedic śrauta literature integrates more magical and protective elements rather than elaborate Soma or altar procedures.[20] Across Vedic branches (śākhās), these Śrauta Sūtras exhibit variations in ritual emphasis, such as differing sequences in altar building or chant modulations, reflecting regional and scholastic adaptations while preserving core sacrificial principles.[3]Historical Context

Origins in Early Vedic Period

The Śrauta tradition emerged during the Early Vedic Period, approximately 1500–1200 BCE, as the foundational ritual framework of Vedic religion, with its earliest textual evidence preserved in the Rigveda.[21] This corpus of hymns, composed by Indo-Aryan poets, reflects a nascent sacrificial system centered on invoking deities through verbal praise and material offerings, predating the more elaborate rituals codified in later Vedic texts.[18] Proto-Śrauta elements are discernible in the Rigveda's depictions of simple communal gatherings where participants offered libations of milk, ghee, and barley to principal deities such as Indra and Agni, often in exchange for protection, prosperity, and victory in battle.[21] These practices evolved from informal feasts among migrating Indo-Aryan tribes into more structured yajñas, or sacrificial rites, as social organization solidified following their influx into the northwestern Indian subcontinent around c. 2000–1500 BCE.[22] The migratory context influenced ritual forms by integrating pastoral and warrior motifs, emphasizing reciprocity between humans and gods in a mobile, tribal society.[21] Key developments include the introduction of the Soma ritual, prominently featured in the Rigveda's ninth mandala, where the plant's juices were pressed, filtered, and offered to energize gods like Indra for cosmic battles, symbolizing vitality and divine inspiration.[23] Later hymns also contain subtle hints of the aśvamedha, or horse sacrifice, such as metaphorical references to equine vitality in Rigveda 1.162–1.163 and 5.27, foreshadowing its later role as a royal sovereignty rite without full procedural detail.[24] These proto-rituals laid the groundwork for Śrauta's emphasis on precise, community-sanctioned performances derived from revealed knowledge.[18]Evolution Through Later Vedic Age

During the Brāhmaṇas era (c. 1000–700 BCE), Śrauta rituals underwent significant elaboration, transitioning from the simpler offerings described in early Vedic hymns to highly structured ceremonies requiring precise procedural knowledge.[1] This period saw the institutionalization of priestly roles, with the Hotṛ responsible for reciting Ṛgvedic verses, the Adhvaryu for executing Yajurvedic actions such as altar preparation and offerings, the Udgātṛ for Sāmavedic chants, and the Brahman for oversight to ensure ritual integrity.[3] Concurrently, a specialized brāhmaṇa class emerged as hereditary ritual experts, professionalizing the performance of these sacrifices and elevating their social status within Vedic society.[3] Key developments included the construction of complex altars, such as the multi-layered brick structures for the Agnicayana sacrifice, which symbolized cosmic order and required advanced geometric principles outlined in the Śulba Sūtras.[3] Śrauta rituals also integrated elements of domestic (gṛhya) practices, allowing householders to incorporate life-cycle events like marriages into larger sacrificial frameworks, thereby bridging personal and communal piety.[3] Philosophical justifications proliferated in texts like the Śatapatha Brāhmaṇa, which interpreted sacrifices as microcosmic recreations of creation myths, linking ritual actions to the maintenance of ṛta (cosmic law) and introducing esoteric concepts of reciprocity between gods and humans.[1] In the socio-political sphere, Śrauta rites played a pivotal role in legitimizing kingship through ceremonies like the Rājasūya (royal consecration) and Aśvamedha (horse sacrifice), which affirmed the ruler's divine authority and territorial sovereignty.[3] These rituals fostered alliances between brāhmaṇas and kṣatriyas, influencing the formation of early Indian polities by embedding sacrificial performance as a marker of political legitimacy and social hierarchy.[1]Core Rituals

Classification of Śrauta Sacrifices

Śrauta sacrifices, as prescribed in the Śrauta Sūtras, are systematically classified into two primary categories: haviryajñas, which involve offerings of havis (vegetable or milky substances) into the consecrated fires, and somayajñas, which center on the ritual preparation and consumption of the sacred Soma juice. This binary division reflects the foundational structure of Vedic ritualism, with haviryajñas serving as preparatory or routine oblations and somayajñas representing more elaborate, intoxicating rites aimed at divine communion and cosmic renewal.[25] The seven core haviryajñas form the essential repertoire of minor Śrauta rites performed by householders or patrons to maintain ritual purity and seasonal harmony. These include:- Agnyādheya: The initial establishment of the three sacred fires (gārhapatya, āhavanīya, and dakṣiṇāgni), marking the commencement of Śrauta practice.

- Agnihotra: Daily oblations of milk into the fire at dawn and dusk, sustaining the cosmic order through perpetual offering.

- Darśapūrṇamāsa: Fortnightly sacrifices on the new and full moon days, involving rice cakes and barley offerings to lunar deities.

- Āgrāyaṇa: The offering of the season's first grains, typically in the autumn, to propitiate agricultural prosperity.

- Cāturmāsya: Seasonal rites performed at the onset of the monsoon, dewy, and winter seasons, featuring varied oblations like curds and grains.

- Nirūḍhapaśubandha: An animal sacrifice integrated into the haviryajña framework, where a victim is bound and offered to reinforce prior rites.

- Sautrāmaṇī: A concluding rite substituting Soma with fermented surā liquor, purifying the patron after major performances.