Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

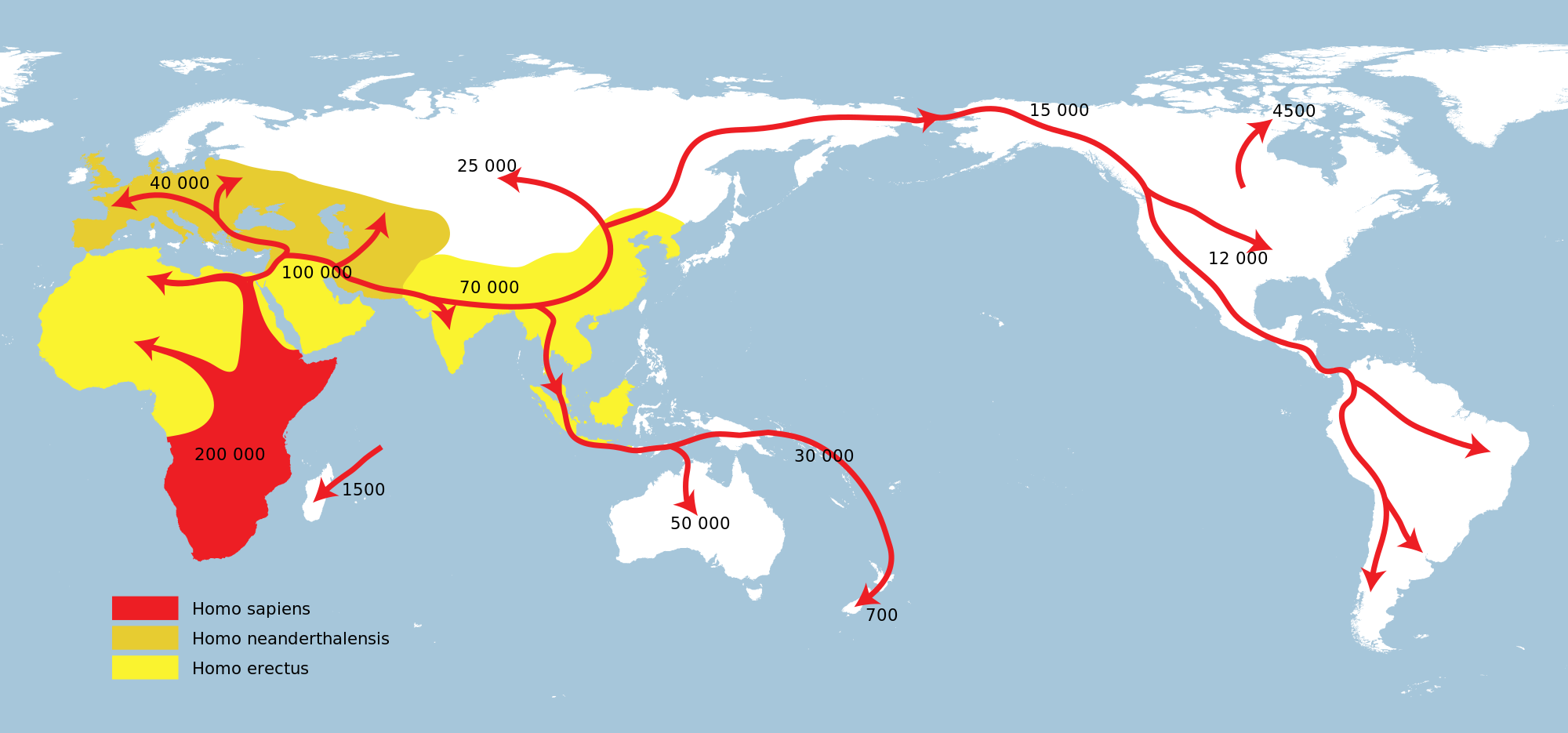

Recent African origin of modern humans

View on Wikipedia

Homo erectus greatest extent (yellow)

Homo neanderthalensis greatest extent (ochre)

Homo sapiens (red)

The recent African origin of modern humans or the "Out of Africa" theory (OOA)[a] holds that present-day humans outside Africa descend mainly from a single expansion of anatomically modern humans (Homo sapiens) from Africa about 70,000–50,000 years ago. It is the most widely accepted[1][2][3] paleo-anthropological model of the geographic origin and early migration of our species.

This expansion follows the early expansions of hominins out of Africa, accomplished by Homo erectus and then Homo neanderthalensis.

The model proposes a "single origin" of Homo sapiens in the taxonomic sense, precluding parallel evolution in other regions of traits considered anatomically modern,[4] but not precluding multiple admixture between H. sapiens and archaic humans in Europe and Asia.[b][5][6] H. sapiens most likely developed in the Horn of Africa between 300,000 and 200,000 years ago,[7][8] although an alternative hypothesis argues that diverse morphological features of H. sapiens appeared locally in different parts of Africa and converged due to gene flow between different populations within the same period.[9][10] The "recent African origin" model proposes that all modern non-African populations are substantially descended from populations of H. sapiens that left Africa after that time.

There were at least several "out-of-Africa" dispersals of modern humans, possibly beginning as early as 270,000 years ago, certainly via northern Africa and the Arabian Peninsula about 130,000 to 115,000 years ago at least.[17] There is evidence that modern humans had reached China around 80,000 years ago.[18][19] Practically all of these early waves seem to have gone extinct or retreated back, and present-day humans outside Africa descend mainly from a single expansion about 70,000–50,000 years ago,[20][21][22][7][8][23][24][excessive citations] via the so-called "Southern Route". These humans spread rapidly along the coast of Asia and reached Australia by around 65,000–50,000 years ago,[25][26][c] (though some researchers question the earlier Australian dates and place the arrival of humans there at 50,000 years ago at earliest,[27][28] while others have suggested that these first settlers of Australia may represent an older wave before the more significant out of Africa migration and thus not necessarily be ancestral to the region's later inhabitants[22]) while Europe was populated by an early offshoot which settled the Near East and Europe less than 55,000 years ago.[29][30][31]

In the 2010s, studies in population genetics uncovered evidence of interbreeding that occurred between H. sapiens and archaic humans in Eurasia, Oceania and Africa,[32][33][34] indicating that modern population groups, while mostly derived from early H. sapiens, are to a lesser extent also descended from regional variants of archaic humans.

Proposed waves

[edit]

"Recent African origin", or Out of Africa II, refers to the migration of anatomically modern humans (Homo sapiens) out of Africa after their emergence at c. 300,000 to 200,000 years ago, in contrast to "Out of Africa I", which refers to the migration of archaic humans from Africa to Eurasia from before 1.8 and up to 0.5 million years ago. Omo-Kibish I (Omo I) from southern Ethiopia is the oldest anatomically modern Homo sapiens skeleton currently known (around 233,000 years old).[36] There are even older Homo sapiens fossils from Jebel Irhoud in Morocco which exhibit a mixture of modern and archaic features at around 315,000 years old.[37]

Since the beginning of the 21st century, the picture of "recent single-origin" migrations has become significantly more complex, due to the discovery of modern-archaic admixture and the increasing evidence that the "recent out-of-Africa" migration took place in waves over a long time. As of 2010, there were two main accepted dispersal routes for the out-of-Africa migration of early anatomically modern humans, the "Northern Route" (via Nile Valley and Sinai) and the "Southern Route" via the Bab-el-Mandeb strait.[38]

- Posth et al. (2017) suggest that early Homo sapiens, or "another species in Africa closely related to us", might have first migrated out of Africa around 270,000 years ago based on the closer affinity within Neanderthals' mitochondrial genomes to Homo sapiens than Denisovans.[39]

- An interpration, with as of yet limited recognition, of a skull fragment coming from Apidima Cave in Greece dated at 210,000 years ago as a Homo sapiens specimen may also points to an early Homo sapiens migration.[40] Finds at Misliya cave, which include a partial jawbone with eight teeth, that may belong to a Homo sapiens specimen, have been dated to around 185,000 years ago. Layers dating from between 250,000 and 140,000 years ago in the same cave contained tools of the Levallois type which could put the date of the first migration even earlier if the tools can be associated with the modern human jawbone finds.[41][42][43]

- An eastward dispersal from Northeast Africa to Arabia 150,000–130,000 years ago is based on the stone tools finds at Jebel Faya dated to 127,000 years ago (discovered in 2011), although fossil evidence in the area is significantly later at 85,000 years ago.[11][44] Possibly related to this wave are the finds from Zhirendong cave, Southern China, dated to more than 100,000 years ago.[45] Other evidence of modern human presence in China has been dated to 80,000 years ago.[19]

- The most significant out of Africa dispersal took place around 50,000–70,000 years ago via the so-called Southern Route, either before[46] or after[30][31] the Toba event, which happened between 69,000 and 77,000 years ago.[46] This dispersal followed the southern coastline of Asia and reached Australia around 65,000–50,000 years ago or according to some research, by 50,000 years ago at earliest.[27][28] Western Asia was "re-occupied" by a different derivation from this wave around 50,000 years ago and Europe was populated from Western Asia beginning around 43,000 years ago.[38]

- Wells (2003) describes an additional wave of migration after the southern coastal route, a northern migration into Europe about 45,000 years ago.[d] This possibility is ruled out by Macaulay et al. (2005) and Posth et al. (2016), who argue for a single coastal dispersal, with an early offshoot into Europe.

Northern Route dispersal

[edit]

Beginning 135,000 years ago, tropical Africa experienced megadroughts which drove humans from the land and towards the sea shores, and forced them to cross over to other continents.[47][e]

Fossils of early Homo sapiens were found in Qafzeh and Es-Skhul Caves in Israel and have been dated to 80,000 to 120,000 years ago.[48][49] These humans seem to have either become extinct or retreated back to Africa 70,000 to 80,000 years ago, possibly replaced by southbound Neanderthals escaping the colder regions of ice-age Europe.[20] Hua Liu et al. analyzed autosomal microsatellite markers dating to about 56,000 years ago. They interpret the paleontological fossil as an isolated early offshoot that retracted back to Africa.[21]

The discovery of stone tools in the United Arab Emirates in 2011 at the Faya-1 site in Mleiha, Sharjah, indicated the presence of modern humans at least 125,000 years ago,[11] leading to a resurgence of the "long-neglected" North African route.[12][50][13][14] This new understanding of the role of the Arabian dispersal began to change following results from archaeological and genetic studies stressing the importance of southern Arabia as a corridor for human expansions out of Africa.[51]

In Oman, a site was discovered by Bien Joven in 2011 containing more than 100 surface scatters of stone tools belonging to the late Nubian Complex, known previously only from archaeological excavations in the Sudan. Two optically stimulated luminescence age estimates placed the Arabian Nubian Complex at approximately 106,000 years old. This provides evidence for a distinct Stone Age technocomplex in southern Arabia, around the earlier part of the Marine Isotope Stage 5.[52]

According to Kuhlwilm and his co-authors, Neanderthals contributed genetically to modern humans then living outside of Africa around 100,000 years ago: humans which had already split off from other modern humans around 200,000 years ago, and this early wave of modern humans outside Africa also contributed genetically to the Altai Neanderthals.[53] They found that "the ancestors of Neanderthals from the Altai Mountains and early modern humans met and interbred, possibly in the Near East, many thousands of years earlier than previously thought".[53] According to co-author Ilan Gronau, "This actually complements archaeological evidence of the presence of early modern humans out of Africa around and before 100,000 years ago by providing the first genetic evidence of such populations."[53] Similar genetic admixture events have been noted in other regions as well.[54]

Southern Route dispersal

[edit]Coastal route

[edit]

By some 50–70,000 years ago, a subset of the bearers of mitochondrial haplogroup L3 migrated from East Africa into the Near East. It has been estimated that from a population of 2,000 to 5,000 individuals in Africa, only a small group, possibly as few as 150 to 1,000 people, crossed the Red Sea.[55][56] The group that crossed the Red Sea travelled along the coastal route around Arabia and the Persian Plateau to India, which appears to have been the first major settling point.[57] Wells (2003) argued for the route along the southern coastline of Asia, across about 250 kilometres (155 mi), reaching Australia by around 50,000 years ago.

Today at the Bab-el-Mandeb straits, the Red Sea is about 20 kilometres (12 mi) wide, but 50,000 years ago sea levels were 70 m (230 ft) lower (owing to glaciation) and the water channel was much narrower. Though the straits were never completely closed, they were narrow enough to have enabled crossing using simple rafts, and there may have been islands in between.[38][58] Shell middens 125,000 years old have been found in Eritrea,[59] indicating that the diet of early humans included seafood obtained by beachcombing.

Toba eruption

[edit]The dating of the Southern Dispersal is a matter of dispute.[46] It may have happened either pre- or post-Toba, a catastrophic volcanic eruption that took place between 69,000 and 77,000 years ago at the site of present-day Lake Toba in Sumatra, Indonesia. Stone tools discovered below the layers of ash deposited in India may point to a pre-Toba dispersal but the source of the tools is disputed.[46] An indication for post-Toba is haplo-group L3, that originated before the dispersal of humans out of Africa and can be dated to 60,000–70,000 years ago, "suggesting that humanity left Africa a few thousand years after Toba".[46] Some research showing slower than expected genetic mutations in human DNA was published in 2012, indicating a revised dating for the migration to between 90,000 and 130,000 years ago.[60] Some more recent research suggests a migration out-of-Africa of around 50,000-65,000 years ago of the ancestors of modern non-African populations, similar to most previous estimates.[22][61][62]

West Asia

[edit]Following the fossils dating 80,000 to 120,000 years ago from Qafzeh and Es-Skhul Caves in Israel there are no H. sapiens fossils in the Levant until the Manot 1 fossil from Manot Cave in Israel, dated to 54,700 years ago,[63] though the dating was questioned by Groucutt et al. (2015). The lack of fossils and stone tool industries that can be safely associated with modern humans in the Levant has been taken to suggest that modern humans were outcompeted by Neanderthals until around 55,000 years ago, who would have placed a barrier on modern human dispersal out of Africa through the Northern Route.[64][failed verification] Climate reconstructions also support a Southern Route dispersal of modern humans as the Bab-el-Mandeb strait experienced a climate more conductive to human migration than the northern landbridge to the Levant during the major human dispersal out of Africa.[65]

A 2023 study proposed that Eurasians and Africans genetically diverged ~100,000 years ago. Main Eurasians then lived in the Saudi Peninsula, genetically isolated from at least 85 kya, before expanding north 54 kya. For reference, Homo sapiens and Neanderthals diverged ~500 kya.[66]

Oceania

[edit]Fossils from Lake Mungo, Australia, have been dated to about 42,000 years ago.[67][68] Other fossils from a site called Madjedbebe have been dated to at least 65,000 years ago,[69][70] though some researchers doubt this early estimate and date the Madjedbebe fossils at about 50,000 years ago at the oldest.[27][28]

Phylogenetic data suggests that an early Eastern Eurasian (Eastern non-African) meta-population trifurcated somewhere in eastern South Asia, and gave rise to the Australo-Papuans, the Ancient Ancestral South Indians (AASI), as well as East/Southeast Asians, although Papuans may have also received some gene flow from an earlier group (xOoA), around 2%,[71] next to additional archaic admixture in the Sahul region.[72][73]

According to one study, Papuans could have either formed from a mixture between an East Eurasian lineage and lineage basal to West and East Asians, or as a sister lineage of East Asians with or without a minor basal OoA or xOoA contribution.[74]

A Holocene hunter-gatherer sample (Leang_Panninge) from South Sulawesi was found to be genetically in between East-Eurasians and Australo-Papuans. The sample could be modeled as ~50% Papuan-related and ~50% Basal-East Asian-related (Andamanese Onge or Tianyuan). The authors concluded that Basal-East Asian ancestry was far more widespread and the peopling of Insular Southeast Asia and Oceania was more complex than previously anticipated.[75][76]

East and Southeast Asia

[edit]In China, the Liujiang man (Chinese: 柳江人) is among the earliest modern humans found in East Asia.[77] The date most commonly attributed to the remains is 67,000 years ago.[78] High rates of variability yielded by various dating techniques carried out by different researchers place the most widely accepted range of dates with 67,000 BP as a minimum, but do not rule out dates as old as 159,000 BP.[78] Liu, Martinón-Torres et al. (2015) claim that modern human teeth have been found in China dating to at least 80,000 years ago.[79]

Tianyuan man from China has a probable date range between 38,000 and 42,000 years ago, while Liujiang man from the same region has a probable date range between 67,000 and 159,000 years ago. According to 2013 DNA tests, Tianyuan man is related "to many present-day Asians and Native Americans".[80][81][82][83][84] Tianyuan is similar in morphology to Liujiang man, and some Jōmon period modern humans found in Japan, as well as modern East and Southeast Asians.[85][86][87]

A 2021 study about the population history of Eastern Eurasia, concluded that distinctive Basal-East Asian (East-Eurasian) ancestry originated in Mainland Southeast Asia at ~50,000BC from a distinct southern Himalayan route, and expanded through multiple migration waves southwards and northwards respectively.[88]

According to a 2024 study, Southeast Asia was the "demographic center of expansion" after some Out of African migrants returned to Africa, evident by the presence of basal Y-chromosome Eurasian lineages (C, D, F, K) in the region.[89]

Americas

[edit]Genetic studies concluded that Native Americans descended from a single founding population that initially split from a Basal-East Asian source population in Mainland Southeast Asia around 36,000 years ago, at the same time at which the proper Jōmon people split from Basal-East Asians, either together with Ancestral Native Americans or during a separate expansion wave. They also show that the basal northern and southern Native American branches, to which all other Indigenous peoples belong, diverged around 16,000 years ago.[90][91] An indigenous American sample from 16,000BC in Idaho, which is craniometrically similar to modern Native Americans as well as Paleosiberians, was found to have largely East-Eurasian ancestry and showed high affinity with contemporary East Asians, as well as Jōmon period samples of Japan, confirming that Ancestral Native Americans split from an East-Eurasian source population in Eastern Siberia.[92]

Europe

[edit]According to Macaulay et al. (2005), an early offshoot from the southern dispersal with haplogroup N followed the Nile from East Africa, heading northwards and crossing into Asia through the Sinai. This group then branched, some moving into Europe and others heading east into Asia.[30] This hypothesis is supported by the relatively late date of the arrival of modern humans in Europe as well as by archaeological and DNA evidence.[30] Based on an analysis of 55 human mitochondrial genomes (mtDNAs) of hunter-gatherers, Posth et al. (2016) argue for a "rapid single dispersal of all non-Africans less than 55,000 years ago". By 45,000 years ago, modern humans are known to have reached northwestern Europe.[93]

Genetic reconstruction

[edit]Mitochondrial haplogroups

[edit]Within Africa

[edit]

The first lineage to branch off from Mitochondrial Eve was L0. This haplogroup is found in high proportions among the San of Southern Africa and the Sandawe of East Africa. It is also found among the Mbuti people.[94][95] These groups branched off early in human history and have remained relatively genetically isolated since then. Haplogroups L1, L2, and L3 are descendants of L1–L6, and are largely confined to Africa. The macro haplogroups M and N, which are the lineages of the rest of the world outside Africa, descend from L3. L3 is about 70,000 years old, while haplogroups M and N are about 65–55,000 years old.[96][62] The relationship between such gene trees and demographic history is still debated when applied to dispersals.[97]

Of all the lineages present in Africa, the female descendants of only one lineage, mtDNA haplogroup L3, are found outside Africa. If there had been several migrations, one would expect descendants of more than one lineage to be found. L3's female descendants, the M and N haplogroup lineages, are found in very low frequencies in Africa (although haplogroup M1 populations are very ancient and diversified in North and North-east Africa) and appear to be more recent arrivals.[citation needed] A possible explanation is that these mutations occurred in East Africa shortly before the exodus and became the dominant haplogroups thereafter by means of the founder effect. Alternatively, the mutations may have arisen shortly afterwards.

Southern Route and haplogroups M and N

[edit]Results from mtDNA collected from aboriginal Malaysians called Orang Asli indicate that the haplogroups M and N share characteristics with original African groups from approximately 85,000 years ago, and share characteristics with sub-haplogroups found in coastal south-east Asian regions, such as Australasia, the Indian subcontinent and throughout continental Asia, which had dispersed and separated from their African progenitor approximately 65,000 years ago. This southern coastal dispersal would have occurred before the dispersal through the Levant approximately 45,000 years ago.[30] This hypothesis attempts to explain why haplogroup N is predominant in Europe and why haplogroup M is absent in Europe. Evidence of the coastal migration is thought to have been destroyed by the rise in sea levels during the Holocene epoch.[98] Alternatively, a small European founder population that had expressed haplogroup M and N at first, could have lost haplogroup M through random genetic drift resulting from a bottleneck (i.e. a founder effect).

The group that crossed the Red Sea travelled along the coastal route around Arabia and Persia until reaching India.[57] Haplogroup M is found in high frequencies along the southern coastal regions of Pakistan and India and it has the greatest diversity in India, indicating that it is here where the mutation may have occurred.[57] Sixty percent of the Indian population belong to Haplogroup M. The indigenous people of the Andaman Islands also belong to the M lineage. The Andamanese are thought to be offshoots of some of the earliest inhabitants in Asia because of their long isolation from the mainland. They are evidence of the coastal route of early settlers that extends from India to Thailand and Indonesia all the way to eastern New Guinea. Since M is found in high frequencies in highlanders from New Guinea and the Andamanese and New Guineans have dark skin and Afro-textured hair, some scientists think they are all part of the same wave of migrants who departed across the Red Sea ~60,000 years ago in the Great Coastal Migration. The proportion of haplogroup M increases eastwards from Arabia to India; in eastern India, M outnumbers N by a ratio of 3:1. Crossing into Southeast Asia, haplogroup N (mostly in the form of derivatives of its R subclade) reappears as the predominant lineage.[citation needed] M is predominant in East Asia, but amongst Indigenous Australians, N is the more common lineage.[citation needed] This haphazard distribution of Haplogroup N from Europe to Australia can be explained by founder effects and population bottlenecks.[99]

Autosomal DNA

[edit]

A 2002 study of African, European, and Asian populations found greater genetic diversity among Africans than among Eurasians, and that genetic diversity among Eurasians is largely a subset of that among Africans, supporting the out-of-Africa model.[101] A large study by Coop et al. (2009) found evidence for natural selection in autosomal DNA outside of Africa. The study distinguishes non-African sweeps (notably KITLG variants associated with skin color), West-Eurasian sweeps (SLC24A5) and East-Asian sweeps (MC1R, relevant to skin color). Based on this evidence, the study concluded that human populations encountered novel selective pressures as they expanded out of Africa.[102] MC1R and its relation to skin color had already been discussed by Harding et al. (2000), p. 1355. According to this study, Papua New Guineans continued to be exposed to selection for dark skin color so that, although these groups are distinct from Africans in other places, the allele for dark skin color shared by contemporary Africans, Andamanese and New Guineans is an archaism. Endicott et al. (2003) suggest convergent evolution. A 2014 study by Gurdasani et al. indicates that the higher genetic diversity in Africa was further increased in some regions by relatively recent Eurasian migrations affecting parts of Africa.[103]

Pathogen DNA

[edit]Another promising route towards reconstructing human genetic genealogy is via the JC virus (JCV), a type of human polyomavirus which is carried by 70–90 percent of humans and which is usually transmitted vertically, from parents to offspring, suggesting codivergence with human populations. For this reason, JCV has been used as a genetic marker for human evolution and migration.[104] This method does not appear to be reliable for the migration out of Africa; in contrast to human genetics, JCV strains associated with African populations are not basal. From this Shackelton et al. (2006) conclude that either a basal African strain of JCV has become extinct or that the original infection with JCV post-dates the migration from Africa.

Admixture of archaic and modern humans

[edit]Evidence for archaic human species (descended from Homo heidelbergensis) having interbred with modern humans outside of Africa, was discovered in the 2010s. This concerns primarily Neanderthal admixture in all modern populations except for Sub-Saharan Africans but evidence has also been presented for Denisova hominin admixture in Australasia (i.e. in Melanesians, Aboriginal Australians and some Negritos).[105] The rate of Neanderthal admixture to European and Asian populations as of 2017 has been estimated at between about 2–3%.[106]

Archaic admixture in some Sub-Saharan African populations hunter-gatherer groups (Biaka Pygmies and San), derived from archaic hominins that broke away from the modern human lineage around 700,000 years ago, was discovered in 2011. The rate of admixture was estimated at 2%.[34] Admixture from archaic hominins of still earlier divergence times, estimated at 1.2 to 1.3 million years ago, was found in Pygmies, Hadza and five Sandawe in 2012.[107][33]

From an analysis of Mucin 7, a highly divergent haplotype that has an estimated coalescence time with other variants around 4.5 million years BP and is specific to African populations, it is inferred to have been derived from interbreeding between African modern and archaic humans.[108]

A study published in 2020 found that the Yoruba and Mende populations of West Africa derive between 2% and 19% of their genome from an as-yet unidentified archaic hominin population that likely diverged before the split of modern humans and the ancestors of Neanderthals and Denisovans.[109]

Stone tools

[edit]In addition to genetic analysis, Petraglia et al. also examines the small stone tools (microlithic materials) from the Indian subcontinent and explains the expansion of population based on the reconstruction of paleoenvironment. He proposed that the stone tools could be dated to 35 ka in South Asia, and the new technology might be influenced by environmental change and population pressure.[110]

History of the theory

[edit]Classical paleoanthropology

[edit]

a: Exit of the L3 precursor to Eurasia. b: Return to Africa and expansion to Asia of basal L3 lineages with subsequent differentiation in both continents.

The cladistic relationship of humans with the African apes was suggested by Charles Darwin after studying the behaviour of African apes, one of which was displayed at the London Zoo.[112] The anatomist Thomas Huxley had also supported the hypothesis and suggested that African apes have a close evolutionary relationship with humans.[113] These views were opposed by the German biologist Ernst Haeckel, who was a proponent of the out-of-Asia theory. Haeckel argued that humans were more closely related to the primates of South-east Asia and rejected Darwin's African hypothesis.[114][115]

In The Descent of Man, Darwin speculated that humans had descended from apes, which still had small brains but walked upright, freeing their hands for uses which favoured intelligence; he thought such apes were African:

In each great region of the world the living mammals are closely related to the extinct species of the same region. It is, therefore, probable that Africa was formerly inhabited by extinct apes closely allied to the gorilla and chimpanzee; and as these two species are now man's nearest allies, it is somewhat more probable that our early progenitors lived on the African continent than elsewhere. But it is useless to speculate on this subject, for an ape nearly as large as a man, namely the Dryopithecus of Lartet, which was closely allied to the anthropomorphous Hylobates, existed in Europe during the Upper Miocene period; and since so remote a period the earth has certainly undergone many great revolutions, and there has been ample time for migration on the largest scale.

— Charles Darwin, Descent of Man[116]

In 1871, there were hardly any human fossils of ancient hominins available. Almost fifty years later, Darwin's speculation was supported when anthropologists began finding fossils of ancient small-brained hominins in several areas of Africa (list of hominina fossils). The hypothesis of recent (as opposed to archaic) African origin developed in the 20th century. The "recent African origin" of modern humans means "single origin" (monogenism) and has been used in various contexts as an antonym to polygenism. The debate in anthropology had swung in favour of monogenism by the mid-20th century. Isolated proponents of polygenism held forth in the mid-20th century, such as Carleton Coon, who thought as late as 1962 that H. sapiens arose five times from H. erectus in five places.[117]

Multiregional origin hypothesis

[edit]The historical alternative to the recent origin model is the multiregional origin of modern humans, initially proposed by Milford Wolpoff in the 1980s. This view proposes that the derivation of anatomically modern human populations from H. erectus at the beginning of the Pleistocene 1.8 million years BP, has taken place within a continuous world population. The hypothesis necessarily rejects the assumption of an infertility barrier between ancient Eurasian and African populations of Homo. The hypothesis was controversially debated during the late 1980s and the 1990s.[118] The now-current terminology of "recent-origin" and "Out of Africa" became current in the context of this debate in the 1990s.[119] Originally seen as an antithetical alternative to the recent origin model, the multiregional hypothesis in its original "strong" form is obsolete, while its various modified weaker variants have become variants of a view of "recent origin" combined with archaic admixture.[120] Stringer (2014) distinguishes the original or "classic" Multiregional model as having existed from 1984 (its formulation) until 2003, to a "weak" post-2003 variant that has "shifted close to that of the Assimilation Model".[121][122]

Mitochondrial analyses

[edit]In the 1980s, Allan Wilson together with Rebecca L. Cann and Mark Stoneking worked on genetic dating of the matrilineal most recent common ancestor of modern human populations (dubbed "Mitochondrial Eve"). To identify informative genetic markers for tracking human evolutionary history, Wilson concentrated on mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA), which is maternally inherited. This DNA material mutates quickly, making it easy to plot changes over relatively short times. With his discovery that human mtDNA is genetically much less diverse than chimpanzee mtDNA, Wilson concluded that modern human populations had diverged recently from a single population while older human species such as Neanderthals and Homo erectus had become extinct.[123] With the advent of archaeogenetics in the 1990s, the dating of mitochondrial and Y-chromosomal haplogroups became possible with some confidence. By 1999, estimates ranged around 150,000 years for the mt-MRCA and 60,000 to 70,000 years for the migration out of Africa.[124]

From 2000 to 2003, there was controversy about the mitochondrial DNA of "Mungo Man 3" (LM3) and its possible bearing on the multiregional hypothesis. LM3 was found to have more than the expected number of sequence differences when compared to modern human DNA (CRS).[125] Comparison of the mitochondrial DNA with that of ancient and modern aborigines, led to the conclusion that Mungo Man fell outside the range of genetic variation seen in Aboriginal Australians and was used to support the multiregional origin hypothesis. A reanalysis of LM3 and other ancient specimens from the area published in 2016, showed it to be akin to modern Aboriginal Australian sequences, inconsistent with the results of the earlier study.[126]

Y-chromosome analyses

[edit]

The Y chromosome, which is paternally inherited, does not go through much recombination and thus stays largely the same after inheritance. Similar to Mitochondrial Eve, this could be studied to track the male most recent common ancestor ("Y-chromosomal Adam" or Y-MRCA).[127]

The most basal lineages have been detected in West, Northwest and Central Africa, suggesting plausibility for the Y-MRCA living in the general region of "Central-Northwest Africa".[13]

A Stanford University School of Medicine study was done by comparing Y-chromosome sequences and mtDNA in 69 men from different geographic regions and constructing a family tree. It was found that the Y-MRCA lived between 120,000 and 156,000, and the Mitochondrial Eve lived between 99,000 and 148,000 years ago, which not only predates some proposed waves of migration, but also meant that both lived in the African continent around the same time.[128]

Another study finds a plausible placement in "the north-western quadrant of the African continent" for the emergence of the A1b haplogroup.[129] The 2013 report of haplogroup A00 found among the Mbo people of western present-day Cameroon is also compatible with this picture.[130]

The revision of Y-chromosomal phylogeny since 2011 has affected estimates for the likely geographical origin of Y-MRCA as well as estimates on time depth. By the same reasoning, future discovery of presently-unknown archaic haplogroups in living people would again lead to such revisions. In particular, the possible presence of between 1% and 4% Neanderthal-derived DNA in Eurasian genomes implies that the (unlikely) event of a discovery of a single living Eurasian male exhibiting a Neanderthal patrilineal line would immediately push back T-MRCA ("time to MRCA") to at least twice its current estimate. However, the discovery of a Neanderthal Y-chromosome by Mendez et al. was tempered by a 2016 study that suggests the extinction of Neanderthal patrilineages, as the lineage inferred from the Neanderthal sequence is outside of the range of contemporary human genetic variation.[131] Questions of geographical origin would become part of the debate on Neanderthal evolution from Homo erectus.

See also

[edit]- Behavioral modernity – Transition of human species to anthropologically modern behavior

- Southern Dispersal – Early human migration out of Africa

- Dawn of Humanity (2015 PBS film) – 2015 American documentary film

- Early human migrations – Spread of humans from Africa through the world

- Genetics and archaeogenetics of South Asia – Biological field of study

- Genetic history of Europe

- Genetic history of Indigenous peoples of the Americas – Genetics on the peopling of the Americas

- Genetic history of Italy

- Genetic history of North Africa – North African genetic history

- Genetic history of the British Isles

- Genetic history of the Iberian Peninsula – Ancestry of Spanish and Portuguese people

- Genetic history of the Middle East

- Hofmeyr Skull – Hominin fossil

- Human evolution – Evolutionary process leading to anatomically modern humans

- Human origins

- Human timeline

- Identical ancestors point – Concept in genetic genealogy

- Indo-Aryan migrations – Migrations of Indo-Aryans into the Indian subcontinent

- Sahara pump theory – Hypothesis about migration of species between Africa and Eurasia

- The Incredible Human Journey – British science documentary television series

- Timeline of human evolution

Notes

[edit]- ^ Also called the recent single-origin hypothesis (RSOH), replacement hypothesis, or recent African origin model (RAO).

- ^ From 1984 to 2003, an alternative scientific hypothesis was the multiregional origin of modern humans, which envisioned a wave of Homo sapiens migrating earlier from Africa and interbreeding with local Homo erectus populations in varied regions of the globe.Jurmain R, Kilgore L, Trevathan W (2008). Essentials of Physical Anthropology. Cengage Learning. pp. 266–. ISBN 978-0-495-50939-4. Retrieved 14 June 2011.

- ^ McChesney (2015): "...genetic evidence suggests that a small band with the marker M168 migrated out of Africa along the coasts of the Arabian Peninsula and India, through Indonesia, and reached Australia very early, between 60,000 and 50,000 years ago. This very early migration into Australia is also supported by Rasmussen et al. (2011)."

- ^ McChesney (2015): "Wells (2003) divided the descendants of men who left Africa into a genealogical tree with 11 lineages. Each genetic marker represents a single-point mutation (SNP) at a specific place in the genome. First, genetic evidence suggests that a small band with the marker M168 migrated out of Africa along the coasts of the Arabian Peninsula and India, through Indonesia, and reached Australia very early, between 60,000 and 50,000 years ago. This very early migration into Australia is also supported by Rasmussen et al. (2011). Second, a group bearing the marker M89 moved out of northeastern Africa into the Middle East 45,000 years ago. From there, the M89 group split into two groups. One group that developed the marker M9 went into Asia about 40,000 years ago. The Asian (M9) group split three ways: into Central Asia (M45), 35,000 years ago; into India (M20), 30,000 years ago; and into China (M122), 10,000 years ago. The Central Asian (M45) group split into two groups: toward Europe (M173), 30,000 years ago and toward Siberia (M242), 20,000 years ago. Finally, the Siberian group (M242) went on to populate North and South America (M3), about 10,000 years ago.[29]

- ^ The researchers used radiocarbon dating techniques on pollen grains trapped in lake-bottom mud to establish vegetation over the ages of the Malawi lake in Africa, taking samples at 300-year-intervals. Samples from the megadrought times had little pollen or charcoal, suggesting sparse vegetation with little to burn. The area around Lake Malawi, today heavily forested, was a desert approximately 135,000 to 90,000 years ago.[47]

References

[edit]- ^ Liu, Prugnolle et al. (2006). "Currently available genetic and archaeological evidence is supportive of a recent single origin of modern humans in East Africa. However, this is where the consensus on human settlement history ends, and considerable uncertainty clouds any more detailed aspect of human colonization history."

- ^ Stringer C (June 2003). "Human evolution: Out of Ethiopia". Nature. 423 (6941): 692–693, 695. Bibcode:2003Natur.423..692S. doi:10.1038/423692a. PMID 12802315. S2CID 26693109.

- ^ Stringer C (2012). Lone Survivors: How We Came to Be the Only Humans on Earth. Henry Holt and Company. p. 26. ISBN 978-1-4299-7344-1 – via Google Books.

- ^ Wolpoff MH, Hawks J, Caspari R (May 2000). "Multiregional, not multiple origins" (PDF). American Journal of Physical Anthropology. 112 (1): 129–136. doi:10.1002/(SICI)1096-8644(200005)112:1<129::AID-AJPA11>3.0.CO;2-K. hdl:2027.42/34270. PMID 10766948.

- ^ Mafessoni F (January 2019). "Encounters with archaic hominins". Nature Ecology & Evolution. 3 (1): 14–15. doi:10.1038/s41559-018-0729-6. PMID 30478304. S2CID 53783648.

- ^ Villanea FA, Schraiber JG (January 2019). "Multiple episodes of interbreeding between Neanderthal and modern humans". Nature Ecology & Evolution. 3 (1): 39–44. doi:10.1038/s41559-018-0735-8. PMC 6309227. PMID 30478305.

- ^ a b University of Huddersfield (20 March 2019). "Researchers shed new light on the origins of modern humans – The work, published in Nature, confirms a dispersal of Homo sapiens from southern to eastern Africa immediately preceded the out-of-Africa migration". EurekAlert!. Retrieved 23 March 2019.

- ^ a b Rito T, Vieira D, Silva M, Conde-Sousa E, Pereira L, Mellars P, et al. (March 2019). "A dispersal of Homo sapiens from southern to eastern Africa immediately preceded the out-of-Africa migration". Scientific Reports. 9 (1): 4728. Bibcode:2019NatSR...9.4728R. doi:10.1038/s41598-019-41176-3. PMC 6426877. PMID 30894612.

- ^ Scerri EM, Chikhi L, Thomas MG (October 2019). "Beyond multiregional and simple out-of-Africa models of human evolution". Nature Ecology & Evolution. 3 (10): 1370–1372. Bibcode:2019NatEE...3.1370S. doi:10.1038/s41559-019-0992-1. hdl:10400.7/954. PMID 31548642. S2CID 202733639.

- ^ Scerri EM, Thomas MG, Manica A, Gunz P, Stock JT, Stringer C, et al. (August 2018). "Did Our Species Evolve in Subdivided Populations across Africa, and Why Does It Matter?". Trends in Ecology & Evolution. 33 (8): 582–594. Bibcode:2018TEcoE..33..582S. doi:10.1016/j.tree.2018.05.005. PMC 6092560. PMID 30007846.

- ^ a b c Armitage SJ, Jasim SA, Marks AE, Parker AG, Usik VI, Uerpmann HP (January 2011). "The southern route "out of Africa": evidence for an early expansion of modern humans into Arabia". Science. 331 (6016): 453–456. Bibcode:2011Sci...331..453A. doi:10.1126/science.1199113. PMID 21273486. S2CID 20296624.

- ^ a b Balter M (January 2011). "Was North Africa the launch pad for modern human migrations?" (PDF). Science. 331 (6013): 20–23. Bibcode:2011Sci...331...20B. doi:10.1126/science.331.6013.20. PMID 21212332.

- ^ a b c Cruciani F, Trombetta B, Massaia A, Destro-Bisol G, Sellitto D, Scozzari R (June 2011). "A revised root for the human Y chromosomal phylogenetic tree: the origin of patrilineal diversity in Africa". American Journal of Human Genetics. 88 (6): 814–818. doi:10.1016/j.ajhg.2011.05.002. PMC 3113241. PMID 21601174.

- ^ a b Smith TM, Tafforeau P, Reid DJ, Grün R, Eggins S, Boutakiout M, Hublin JJ (April 2007). "Earliest evidence of modern human life history in North African early Homo sapiens". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 104 (15): 6128–6133. Bibcode:2007PNAS..104.6128S. doi:10.1073/pnas.0700747104. PMC 1828706. PMID 17372199.

- ^ Bae CJ, Douka K, Petraglia MD (December 2017). "On the origin of modern humans: Asian perspectives". Science. 358 (6368) eaai9067. doi:10.1126/science.aai9067. PMID 29217544.

- ^ Kuo L (10 December 2017). "Early humans migrated out of Africa much earlier than we thought". Quartz. Retrieved 10 December 2017.

- ^ [11][12][13][14][15][16]

- ^ Liu, Wu (14 October 2015). "The earliest unequivocally modern humans in southern China". Nature (526): 696–699. Retrieved 18 June 2025.

- ^ a b Liu, Martinón-Torres et al. (2015).

See also Modern humans in China ~80,000 years ago (?), Dieneks' Anthropology Blog. - ^ a b Finlayson (2009), p. 68.

- ^ a b Liu, Prugnolle et al. (2006).

- ^ a b c Haber M, Jones AL, Connell BA, Arciero E, Yang H, Thomas MG, et al. (August 2019). "A Rare Deep-Rooting D0 African Y-Chromosomal Haplogroup and Its Implications for the Expansion of Modern Humans Out of Africa". Genetics. 212 (4): 1421–1428. doi:10.1534/genetics.119.302368. PMC 6707464. PMID 31196864.

- ^ Posth C, Renaud G, Mittnik M, Drucker DG, Rougier H, Cupillard C, et al. (2016). "Pleistocene Mitochondrial Genomes Suggest a Single Major Dispersal of Non-Africans and a Late Glacial Population Turnover in Europe" (PDF). Current Biology. 26 (6): 827–833. Bibcode:2016CBio...26..827P. doi:10.1016/j.cub.2016.01.037. hdl:2440/114930. PMID 26853362. S2CID 140098861.

- ^ Karmin M, Saag L, Vicente M, Wilson Sayres MA, Järve M, Talas UG, et al. (April 2015). "A recent bottleneck of Y chromosome diversity coincides with a global change in culture". Genome Research. 25 (4): 459–466. doi:10.1101/gr.186684.114. PMC 4381518. PMID 25770088.

- ^ Clarkson C, Jacobs Z, Marwick B, Fullagar R, Wallis L, Smith M, et al. (July 2017). "Human occupation of northern Australia by 65,000 years ago". Nature. 547 (7663): 306–310. Bibcode:2017Natur.547..306C. doi:10.1038/nature22968. hdl:2440/107043. PMID 28726833. S2CID 205257212.

- ^ St. Fleur, Nicholas (19 July 2017). "Humans First Arrived in Australia 65,000 Years Ago, Study Suggests". The New York Times.

- ^ a b c Wood R (2 September 2017). "Comments on the chronology of Madjedbebe". Australian Archaeology. 83 (3): 172–174. doi:10.1080/03122417.2017.1408545. ISSN 0312-2417. S2CID 148777016.

- ^ a b c O'Connell JF, Allen J, Williams MA, Williams AN, Turney CS, Spooner NA, et al. (August 2018). "Homo sapiens first reach Southeast Asia and Sahul?". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 115 (34): 8482–8490. Bibcode:2018PNAS..115.8482O. doi:10.1073/pnas.1808385115. PMC 6112744. PMID 30082377.

- ^ a b McChesney 2015.

- ^ a b c d e Macaulay et al. (2005).

- ^ a b Posth et al. (2016).

See also "mtDNA from 55 hunter-gatherers across 35,000 years in Europe". Dienekes' Anthroplogy Blog. 8 February 2016. - ^ Prüfer K, Racimo F, Patterson N, Jay F, Sankararaman S, Sawyer S, et al. (January 2014) [Online 2013]. "The complete genome sequence of a Neanderthal from the Altai Mountains". Nature. 505 (7481): 43–49. Bibcode:2014Natur.505...43P. doi:10.1038/nature12886. PMC 4031459. PMID 24352235.

- ^ a b Lachance J, Vernot B, Elbers CC, Ferwerda B, Froment A, Bodo JM, et al. (August 2012). "Evolutionary history and adaptation from high-coverage whole-genome sequences of diverse African hunter-gatherers". Cell. 150 (3): 457–469. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2012.07.009. PMC 3426505. PMID 22840920.

- ^ a b Hammer MF, Woerner AE, Mendez FL, Watkins JC, Wall JD (September 2011). "Genetic evidence for archaic admixture in Africa". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 108 (37): 15123–15128. Bibcode:2011PNAS..10815123H. doi:10.1073/pnas.1109300108. PMC 3174671. PMID 21896735.

- ^ a b c Douka K, Bergman CA, Hedges RE, Wesselingh FP, Higham TF (11 September 2013). "Chronology of Ksar Akil (Lebanon) and implications for the colonization of Europe by anatomically modern humans". PLOS ONE. 8 (9) e72931. Bibcode:2013PLoSO...872931D. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0072931. PMC 3770606. PMID 24039825.

- ^ Vidal CM, Lane CS, Asrat A, Barfod DN, Mark DF, Tomlinson EL, et al. (January 2022). "Age of the oldest known Homo sapiens from eastern Africa". Nature. 601 (7894): 579–583. Bibcode:2022Natur.601..579V. doi:10.1038/s41586-021-04275-8. PMC 8791829. PMID 35022610.

- ^ Hublin JJ, Ben-Ncer A, Bailey SE, Freidline SE, Neubauer S, Skinner MM, et al. (June 2017). "New fossils from Jebel Irhoud, Morocco and the pan-African origin of Homo sapiens" (PDF). Nature. 546 (7657): 289–292. Bibcode:2017Natur.546..289H. doi:10.1038/nature22336. PMID 28593953. S2CID 256771372.

- ^ a b c Beyin (2011).

- ^ Posth C, Wißing C, Kitagawa K, Pagani L, van Holstein L, Racimo F, et al. (July 2017). "Deeply divergent archaic mitochondrial genome provides lower time boundary for African gene flow into Neanderthals". Nature Communications. 8 16046. Bibcode:2017NatCo...816046P. doi:10.1038/ncomms16046. PMC 5500885. PMID 28675384.; see also Zimmer C (4 July 2017). "In Neanderthal DNA, Signs of a Mysterious Human Migration". The New York Times. Retrieved 4 July 2017..

- ^ Harvati K, Röding C, Bosman AM, Karakosti FA, Grün R, Stringer C, et al. (July 2019). "Apidima Cave fossils provide earliest evidence of Homo sapiens in Eurasia". Nature. 571 (7766): 500–504. doi:10.1038/s41586-019-1376-z. hdl:10072/397334. PMID 31292546. S2CID 195873640.

- ^ "Scientists discover oldest known modern human fossil outside of Africa: Analysis of fossil suggests Homo sapiens left Africa at least 50,000 years earlier than previously thought". ScienceDaily. Retrieved 27 January 2018.

- ^ Ghosh P (2018). "Modern humans left Africa much earlier". BBC News. Retrieved 27 January 2018.

- ^ Hershkovitz I, Weber GW, Quam R, Duval M, Grün R, Kinsley L, et al. (January 2018). "The earliest modern humans outside Africa". Science. 359 (6374): 456–459. Bibcode:2018Sci...359..456H. doi:10.1126/science.aap8369. hdl:10072/372670. PMID 29371468. S2CID 206664380.

- ^ Groucutt HS, Grün R, Zalmout IS, Drake NA, Armitage SJ, Candy I, et al. (May 2018). "Homo sapiens in Arabia by 85,000 years ago". Nature Ecology & Evolution. 2 (5): 800–809. Bibcode:2018NatEE...2..800G. doi:10.1038/s41559-018-0518-2. PMC 5935238. PMID 29632352.

- ^ Liu W, Jin CZ, Zhang YQ, Cai YJ, Xing S, Wu XJ, et al. (November 2010). "Human remains from Zhirendong, South China, and modern human emergence in East Asia". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 107 (45): 19201–19206. Bibcode:2010PNAS..10719201L. doi:10.1073/pnas.1014386107. PMC 2984215. PMID 20974952.

- ^ a b c d e Appenzeller (2012).

- ^ a b Jensen MN (8 October 2007). "Newfound Ancient African Megadroughts May Have Driven Evolution of Humans and Fish. The findings provide new insights into humans' migration out of Africa and the evolution of fishes in Africa's Great Lakes". The University of Arizona. Retrieved 25 September 2017.

- ^ Stringer CB, Grün R, Schwarcz HP, Goldberg P (April 1989). "ESR dates for the hominid burial site of Es Skhul in Israel". Nature. 338 (6218): 756–758. Bibcode:1989Natur.338..756S. doi:10.1038/338756a0. PMID 2541339. S2CID 4332370.

- ^ Grün R, Stringer C, McDermott F, Nathan R, Porat N, Robertson S, et al. (September 2005). "U-series and ESR analyses of bones and teeth relating to the human burials from Skhul". Journal of Human Evolution. 49 (3): 316–334. Bibcode:2005JHumE..49..316G. doi:10.1016/j.jhevol.2005.04.006. PMID 15970310.

- ^ Scerri, Eleanor M.L.; Drake, Nick A.; Jennings, Richard; Groucutt, Huw S. (2014). "Earliest evidence for the structure of Homo sapiens populations in Africa". Quaternary Science Reviews. 101: 207–216. Bibcode:2014QSRv..101..207S. doi:10.1016/j.quascirev.2014.07.019.

- ^ Bretzke, Knut; Armitage, Simon J.; Parker, Adrian G.; Walkington, Helen; Uerpmann, Hans-Peter (2013). "The environmental context of Paleolithic settlement at Jebel Faya, Emirate Sharjah, UAE". Quaternary International. 300: 83–93. Bibcode:2013QuInt.300...83B. doi:10.1016/j.quaint.2013.01.028.

- ^ Rose JI, Usik VI, Marks AE, Hilbert YH, Galletti CS, Parton A, et al. (2011). "The Nubian Complex of Dhofar, Oman: an African middle Stone Age industry in Southern Arabia". PLOS ONE. 6 (11) e28239. Bibcode:2011PLoSO...628239R. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0028239. PMC 3227647. PMID 22140561.

- ^ a b c Kuhlwilm et al. (2016).

See also Ancestors of Eastern Neandertals admixed with modern humans 100 thousand years ago, Dienekes'Anthropology Blog. - ^ Gibbons A (2 March 2017). "Ancient skulls may belong to elusive humans called Denisovans". Science. doi:10.1126/science.aal0846. Retrieved 25 September 2017.

- ^ Zhivotovsky LA, Rosenberg NA, Feldman MW (May 2003). "Features of evolution and expansion of modern humans, inferred from genomewide microsatellite markers". American Journal of Human Genetics. 72 (5): 1171–1186. doi:10.1086/375120. PMC 1180270. PMID 12690579.

- ^ Stix G (2008). "The Migration History of Humans: DNA Study Traces Human Origins Across the Continents". Scientific American. Retrieved 14 June 2011.

- ^ a b c Metspalu M, Kivisild T, Metspalu E, Parik J, Hudjashov G, Kaldma K, et al. (August 2004). "Most of the extant mtDNA boundaries in south and southwest Asia were likely shaped during the initial settlement of Eurasia by anatomically modern humans". BMC Genetics. 5: 26. doi:10.1186/1471-2156-5-26. PMC 516768. PMID 15339343.

- ^ Fernandes CA, Rohling EJ, Siddall M (June 2006). "Absence of post-Miocene Red Sea land bridges: biogeographic implications". Journal of Biogeography. 33 (6): 961–966. Bibcode:2006JBiog..33..961F. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2699.2006.01478.x.

- ^ Walter RC, Buffler RT, Bruggemann JH, Guillaume MM, Berhe SM, Negassi B, et al. (May 2000). "Early human occupation of the Red Sea coast of Eritrea during the last interglacial". Nature. 405 (6782): 65–69. Bibcode:2000Natur.405...65W. doi:10.1038/35011048. PMID 10811218. S2CID 4417823.

- ^ Catherine B (24 November 2012). "Our True Dawn". New Scientist. 216 (2892): 34–37. Bibcode:2012NewSc.216...34B. doi:10.1016/S0262-4079(12)63018-8. ISSN 0262-4079.

- ^ Karmin M, Saag L, Vicente M, Wilson Sayres MA, Järve M, et al. (April 2015). "A recent bottleneck of Y chromosome diversity coincides with a global change in culture". Genome Research. 25 (4): 459–466. doi:10.1101/gr.186684.114. PMC 4381518. PMID 25770088.

- ^ a b Vai S, Sarno S, Lari M, Luiselli D, Manzi G, Gallinaro M, et al. (March 2019). "Ancestral mitochondrial N lineage from the Neolithic 'green' Sahara". Scientific Reports. 9 (1): 3530. Bibcode:2019NatSR...9.3530V. doi:10.1038/s41598-019-39802-1. PMC 6401177. PMID 30837540.

- ^ Hershkovitz et al. (2015)

See also "55,000-Year-Old Skull Fossil Sheds New Light on Human Migration out of Africa". Science News. 29 January 2015. - ^ Shea, John J. (2003). "Neandertals, competition, and the origin of modern human behavior in the Levant". Evolutionary Anthropology: Issues, News, and Reviews. 12 (4): 173–187. doi:10.1002/evan.10101. ISSN 1060-1538.

- ^ Beyer RM, Krapp M, Eriksson A, Manica A (August 2021). "Climatic windows for human migration out of Africa in the past 300,000 years". Nature Communications. 12 (1): 4889. Bibcode:2021NatCo..12.4889B. doi:10.1038/s41467-021-24779-1. PMC 8384873. PMID 34429408.

- ^ Tobler, Raymond; Souilmi, Yassine; Huber, Christian D.; Bean, Nigel; Turney, Chris S. M.; Grey, Shane T.; Cooper, Alan (30 May 2023). "The role of genetic selection and climatic factors in the dispersal of anatomically modern humans out of Africa". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 120 (22) e2213061120. Bibcode:2023PNAS..12013061T. doi:10.1073/pnas.2213061120. ISSN 0027-8424. PMC 10235988. PMID 37220274.

- ^ Bowler JM, Johnston H, Olley JM, Prescott JR, Roberts RG, Shawcross W, Spooner NA (February 2003). "New ages for human occupation and climatic change at Lake Mungo, Australia". Nature. 421 (6925): 837–640. Bibcode:2003Natur.421..837B. doi:10.1038/nature01383. PMID 12594511. S2CID 4365526.

- ^ Olleya JM, Roberts RG, Yoshida H, Bowler JM (2006). "Single-grain optical dating of grave-infill associated with human burials at Lake Mungo, Australia". Quaternary Science Reviews. 25 (19–20): 2469–2474. Bibcode:2006QSRv...25.2469O. doi:10.1016/j.quascirev.2005.07.022.

- ^ Clarkson, Chris; Jacobs, Zenobia; et al. (19 July 2017). "Human occupation of northern Australia by 65,000 years ago" (PDF). Nature. 547 (7663): 306–310. Bibcode:2017Natur.547..306C. doi:10.1038/nature22968. hdl:2440/107043. PMID 28726833. S2CID 205257212.

- ^ Gibbons, Ann (20 July 2017). "The first Australians arrived early". Science. 357 (6348): 238–239. Bibcode:2017Sci...357..238G. doi:10.1126/science.357.6348.238. PMID 28729491.

- ^ "Almost all living people outside of Africa trace back to a single migration more than 50,000 years ago". www.science.org. Retrieved 19 August 2022.

- ^ Yang M (6 January 2022). "A genetic history of migration, diversification, and admixture in Asia". Human Population Genetics and Genomics: 1–32. doi:10.47248/hpgg2202010001.

- ^ Genetics and material culture support repeated expansions into Paleolithic Eurasia from a population hub out of Africa, Vallini et al. 2022 (April 4, 2022) Quote: "Taken together with a lower bound of the final settlement of Sahul at 37 kya it is reasonable to describe Papuans as either an almost even mixture between East-Eurasians and a lineage basal to West and East-Eurasians which occurred sometimes between 45 and 38kya, or as a sister lineage of East-Eurasians with or without a minor basal OoA or xOoA contribution. We here chose to parsimoniously describe Papuans as a simple sister group of Tianyuan, cautioning that this may be just one out of six equifinal possibilities."

- ^ Genetics and material culture support repeated expansions into Paleolithic Eurasia from a population hub out of Afri, Vallini et al. 2021 (October 15, 2021) Quote: "Taken together with a lower bound of the final settlement of Sahul at 37 kya (the date of the deepest population splits estimated by 1) it is reasonable to describe Papuans as either an almost even mixture between East Asians and a lineage basal to West and East Asians occurred sometimes between 45 and 38kya, or as a sister lineage of East Asians with or without a minor basal OoA or xOoA contribution. "

- ^ Genomic insights into the human population history of Australia and New Guinea, University of Cambridge, Bergström et al. 2018

- ^ Carlhoff S, Duli A, Nägele K, Nur M, Skov L, Sumantri I, et al. (August 2021). "Genome of a middle Holocene hunter-gatherer from Wallacea". Nature. 596 (7873): 543–547. Bibcode:2021Natur.596..543C. doi:10.1038/s41586-021-03823-6. PMC 8387238. PMID 34433944.

The qpGraph analysis confirmed this branching pattern, with the Leang Panninge individual branching off from the Near Oceanian clade after the Denisovan gene flow, although with the most supported topology indicating around 50% of a basal East Asian component contributing to the Leang Panninge genome (Fig. 3c, Supplementary Figs. 7–11).

- ^ Shen G, Wang W, Wang Q, Zhao J, Collerson K, Zhou C, Tobias PV (December 2002). "U-Series dating of Liujiang hominid site in Guangxi, Southern China". Journal of Human Evolution. 43 (6): 817–829. Bibcode:2002JHumE..43..817S. doi:10.1006/jhev.2002.0601. PMID 12473485.

- ^ a b Rosenburg K (2002). "A Late Pleistocene Human Skeleton from Liujiang, China Suggests Regional Population Variation in Sexual Dimorphism in the Human Pelvis". Variability and Evolution.

- ^ Kaifu, Yousuke; Fujita, Masaki (2012). "Fossil record of early modern humans in East Asia". Quaternary International. 248: 2–11. Bibcode:2012QuInt.248....2K. doi:10.1016/j.quaint.2011.02.017.

- ^ "A relative from the Tianyuan Cave". Max Planck Society. 21 January 2013.

- ^ "A relative from the Tianyuan Cave: Humans living 40,000 years ago likely related to many present-day Asians and Native Americans". Science Daily. 21 January 2013.

- ^ "DNA Analysis Reveals Common Origin of Tianyuan Humans and Native Americans, Asians". Sci-News. 24 January 2013.

- ^ "Ancient human DNA suggests minimal interbreeding". Science News. 21 January 2013.

- ^ "Ancient Bone DNA Shows Ancestry of Modern Asians & Native Americans". Caving News. 31 January 2013.

- ^ Hu Y, Shang H, Tong H, Nehlich O, Liu W, Zhao C, et al. (July 2009). "Stable isotope dietary analysis of the Tianyuan 1 early modern human". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 106 (27): 10971–10974. Bibcode:2009PNAS..10610971H. doi:10.1073/pnas.0904826106. PMC 2706269. PMID 19581579.

- ^ Brown P (August 1992). "Recent human evolution in East Asia and Australasia". Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London. Series B, Biological Sciences. 337 (1280): 235–242. Bibcode:1992RSPTB.337..235B. doi:10.1098/rstb.1992.0101. PMID 1357698.

- ^ Curnoe D, Xueping J, Herries AI, Kanning B, Taçon PS, Zhende B, et al. (14 March 2012). "Human remains from the Pleistocene-Holocene transition of southwest China suggest a complex evolutionary history for East Asians". PLOS ONE. 7 (3) e31918. Bibcode:2012PLoSO...731918C. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0031918. PMC 3303470. PMID 22431968.

- ^ Larena M, Sanchez-Quinto F, Sjödin P, McKenna J, Ebeo C, Reyes R, et al. (March 2021). "Multiple migrations to the Philippines during the last 50,000 years". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 118 (13) e2026132118. Bibcode:2021PNAS..11826132L. doi:10.1073/pnas.2026132118. PMC 8020671. PMID 33753512.

- ^ Cabrera, Vicente M. (2024). "Early male and female footprints of modern humans across Eurasia and Australasia". bioRxiv – via bioRxiv.

- ^ Moreno-Mayar JV, Potter BA, Vinner L, Steinrücken M, Rasmussen S, Terhorst J, et al. (January 2018). "Terminal Pleistocene Alaskan genome reveals first founding population of Native Americans" (PDF). Nature. 553 (7687): 203–207. Bibcode:2018Natur.553..203M. doi:10.1038/nature25173. PMID 29323294. S2CID 4454580.

- ^ Gakuhari T, Nakagome S, Rasmussen S, Allentoft ME, Sato T, Korneliussen T, et al. (August 2020). "Ancient Jomon genome sequence analysis sheds light on migration patterns of early East Asian populations". Communications Biology. 3 (1): 437. doi:10.1038/s42003-020-01162-2. PMC 7447786. PMID 32843717.

- ^ Davis LG, Madsen DB, Becerra-Valdivia L, Higham T, Sisson DA, Skinner SM, et al. (August 2019). "Late Upper Paleolithic occupation at Cooper's Ferry, Idaho ~16,000 years ago". Science. 365 (6456): 891–897. Bibcode:2019Sci...365..891D. doi:10.1126/science.aax9830. PMID 31467216. S2CID 201672463.

We interpret this temporal and technological affinity to signal a cultural connection with Upper Paleolithic northeastern Asia, which complements current evidence of shared genetic heritage between late Pleistocene peoples of northern Japan and North America.

- ^ Mylopotamitaki, Dorothea; Weiss, Marcel; Fewlass, Helen; Zavala, Elena Irene; Rougier, Hélène; Sümer, Arev Pelin; Hajdinjak, Mateja; Smith, Geoff M.; Ruebens, Karen; Sinet-Mathiot, Virginie; Pederzani, Sarah; Essel, Elena; Harking, Florian S.; Xia, Huan; Hansen, Jakob; Kirchner, André; Lauer, Tobias; Stahlschmidt, Mareike; Hein, Michael; Talamo, Sahra; Wacker, Lukas; Meller, Harald; Dietl, Holger; Orschiedt, Jörg; Olsen, Jesper V.; Zeberg, Hugo; Prüfer, Kay; Krause, Johannes; Meyer, Matthias; Welker, Frido; McPherron, Shannon P.; Schüler, Tim; HublinHublin, Jean-Jacques (31 January 2024). "Homo sapiens reached the higher latitudes of Europe by 45,000 years ago". Nature. 626 (7998): 341–346. Bibcode:2024Natur.626..341M. doi:10.1038/s41586-023-06923-7. ISSN 1476-4687. PMC 10849966. PMID 38297117.

- ^ Gonder MK, Mortensen HM, Reed FA, de Sousa A, Tishkoff SA (March 2007). "Whole-mtDNA genome sequence analysis of ancient African lineages". Molecular Biology and Evolution. 24 (3): 757–768. doi:10.1093/molbev/msl209. PMID 17194802.

- ^ Chen YS, Olckers A, Schurr TG, Kogelnik AM, Huoponen K, Wallace DC (April 2000). "mtDNA variation in the South African Kung and Khwe-and their genetic relationships to other African populations". American Journal of Human Genetics. 66 (4): 1362–1383. doi:10.1086/302848. PMC 1288201. PMID 10739760.

- ^ Soares P, Alshamali F, Pereira JB, Fernandes V, Silva NM, Afonso C, et al. (March 2012). "The Expansion of mtDNA Haplogroup L3 within and out of Africa". Molecular Biology and Evolution. 29 (3): 915–927. doi:10.1093/molbev/msr245. PMID 22096215.

- ^ Groucutt et al. (2015).

- ^ Maca-Meyer N, González AM, Larruga JM, Flores C, Cabrera VM (13 August 2001). "Major genomic mitochondrial lineages delineate early human expansions". BMC Genetics. 2: 13. doi:10.1186/1471-2156-2-13. PMC 55343. PMID 11553319.

- ^ Ingman M, Gyllensten U (July 2003). "Mitochondrial genome variation and evolutionary history of Australian and New Guinean aborigines". Genome Research. 13 (7): 1600–1606. doi:10.1101/gr.686603. PMC 403733. PMID 12840039.

- ^ Hallast P, Agdzhoyan A, Balanovsky O, Xue Y, Tyler-Smith C (February 2021). "A Southeast Asian origin for present-day non-African human Y chromosomes". Human Genetics. 140 (2): 299–307. doi:10.1007/s00439-020-02204-9. PMC 7864842. PMID 32666166.

- ^ Yu N, Chen FC, Ota S, Jorde LB, Pamilo P, Patthy L, et al. (May 2002). "Larger genetic differences within africans than between Africans and Eurasians". Genetics. 161 (1): 269–274. doi:10.1093/genetics/161.1.269. PMC 1462113. PMID 12019240. Retrieved 7 April 2013.

- ^ Coop G, Pickrell JK, Novembre J, Kudaravalli S, Li J, Absher D, et al. (June 2009). Schierup MH (ed.). "The role of geography in human adaptation". PLOS Genetics. 5 (6) e1000500. doi:10.1371/journal.pgen.1000500. PMC 2685456. PMID 19503611.; summary in Racimo F, Schraiber JG, Casey F, Huerta-Sanchez E (2016). "Directional Selection and Adaptation". In Kliman RM (ed.). Encyclopedia of Evolutionary Biology. Academic Press. p. 451. doi:10.1016/B978-0-12-800049-6.00028-7. ISBN 978-0-12-800426-5 – via Google Books.

- ^ Gurdasani D, Carstensen T, Tekola-Ayele F, Pagani L, Tachmazidou I, Hatzikotoulas K, et al. (January 2015). "The African Genome Variation Project shapes medical genetics in Africa". Nature. 517 (7, 534): 327–332. Bibcode:2015Natur.517..327G. doi:10.1038/nature13997. PMC 4297536. PMID 25470054.

- ^ Matisoo-Smith E, Horsburgh KA (2016). DNA for Archaeologists. Routledge.

- ^ Rasmussen M, Guo X, Wang Y, Lohmueller KE, Rasmussen S, Albrechtsen A, et al. (October 2011). "An Aboriginal Australian genome reveals separate human dispersals into Asia". Science. 334 (6052): 94–98. Bibcode:2011Sci...334...94R. doi:10.1126/science.1211177. PMC 3991479. PMID 21940856.

- ^ East Asians 2.3–2.6%, Western Eurasians 1.8–2.4% (Prüfer K, de Filippo C, Grote S, Mafessoni F, Korlević P, Hajdinjak M, et al. (November 2017). "A high-coverage Neandertal genome from Vindija Cave in Croatia". Science. 358 (6363): 655–658. Bibcode:2017Sci...358..655P. doi:10.1126/science.aao1887. PMC 6185897. PMID 28982794.)

- ^ Callaway E (2012). "Hunter-gatherer genomes a trove of genetic diversity". Nature. doi:10.1038/nature.2012.11076. S2CID 87081207.

- ^ Xu D, Pavlidis P, Taskent RO, Alachiotis N, Flanagan C, DeGiorgio M, et al. (October 2017). "Archaic Hominin Introgression in Africa Contributes to Functional Salivary MUC7 Genetic Variation". Molecular Biology and Evolution. 34 (10): 2704–2715. doi:10.1093/molbev/msx206. PMC 5850612. PMID 28957509.

- ^ Durvasula A, Sankararaman S (February 2020). "Recovering signals of ghost archaic introgression in African populations". Science Advances. 6 (7) eaax5097. Bibcode:2020SciA....6.5097D. doi:10.1126/sciadv.aax5097. PMC 7015685. PMID 32095519.

- ^ Petraglia M, Clarkson C, Boivin N, Haslam M, Korisettar R, Chaubey G, et al. (July 2009). "Population increase and environmental deterioration correspond with microlithic innovations in South Asia ca. 35,000 years ago". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 106 (30): 12261–12266. Bibcode:2009PNAS..10612261P. doi:10.1073/pnas.0810842106. PMC 2718386. PMID 19620737.

- ^ Cabrera VM, Marrero P, Abu-Amero KK, Larruga JM (June 2018). "Carriers of mitochondrial DNA macrohaplogroup L3 basal lineages migrated back to Africa from Asia around 70,000 years ago". BMC Evolutionary Biology. 18 (1): 98. Bibcode:2018BMCEE..18...98C. bioRxiv 10.1101/233502. doi:10.1186/s12862-018-1211-4. PMC 6009813. PMID 29921229.

- ^ Lafreniere P (2010). Adaptive Origins: Evolution and Human Development. Taylor & Francis. p. 90. ISBN 978-0-8058-6012-2. Retrieved 14 June 2011 – via Google Books.

- ^ Robinson D, Ash PM (2010). The Emergence of Humans: An Exploration of the Evolutionary Timeline. New York: Wiley. ISBN 978-0-470-01315-1.

- ^ Palmer D (2006). Prehistoric Past Revealed: The Four Billion Year History of Life on Earth. Berkeley: University of California Press. p. 43. ISBN 978-0-520-24827-4.

- ^ Regal B (2004). Human evolution: a guide to the debates. Santa Barbara, Calif: ABC-CLIO. pp. 73–75. ISBN 978-1-85109-418-9.

- ^ "The Descent of Man Chapter 6 – "On the Affinities and Genealogy of Man"". Darwin-online.org.uk. Retrieved 11 January 2011.

- ^ Jackson JP Jr (2001). "'In Ways Unacademical': The Reception of Carleton S. Coon's The Origin of Races" (PDF). Journal of the History of Biology. 34 (2): 247–285. doi:10.1023/A:1010366015968. S2CID 86739986. Archived from the original (PDF) on 14 May 2013.

- ^ Stringer CB, Andrews P (March 1988). "Genetic and fossil evidence for the origin of modern humans". Science. 239 (4845): 1263–1268. Bibcode:1988Sci...239.1263S. doi:10.1126/science.3125610. PMID 3125610.

Stringer C, Bräuer G (1994). "Methods, misreading, and bias". American Anthropologist. 96 (2): 416–424. doi:10.1525/aa.1994.96.2.02a00080.

Stringer CB (1992). "Replacement, continuity and the origin of Homo sapiens". In Smith FH (ed.). Continuity or replacement? Controversies in Homo sapiens evolution. Rotterdam: Balkema. pp. 9–24.

Bräuer G, Stringer C (1997). "Models, polarization, and perspectives on modern human origins". Conceptual issues in modern human origins research. New York: Aldine de Gruyter. pp. 191–201. - ^ Wu L (1997). "The dental continuity of humans in China from Pleistocene to Holocene, and the origin of mongoloids". Quaternary Geology. 21: 24–32. ISBN 978-90-6764-243-9.

- ^ Stringer C (2001). "Modern human origins – distinguishing the models". African Archaeological Review. 18 (2): 67–75. doi:10.1023/A:1011079908461. S2CID 161991922.

- ^ Stringer C (April 2002). "Modern human origins: progress and prospects". Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London. Series B, Biological Sciences. 357 (1420): 563–579. doi:10.1098/rstb.2001.1057. PMC 1692961. PMID 12028792.

- ^ Stringer C (May 2014). "Why we are not all multiregionalists now". Trends in Ecology & Evolution. 29 (5): 248–251. Bibcode:2014TEcoE..29..248S. doi:10.1016/j.tree.2014.03.001. PMID 24702983.

- ^ "Allan Wilson: Revolutionary Evolutionist". New Zealanders Heroes.

- ^ Wallace DC, Brown MD, Lott MT (September 1999). "Mitochondrial DNA variation in human evolution and disease". Gene. 238 (1): 211–230. doi:10.1016/S0378-1119(99)00295-4. PMID 10570998. "evidence that our species arose in Africa about 150,000 years before present (YBP), migrated out of Africa into Asia about 60,000 to 70,000 YBP and into Europe about 40,000 to 50,000 YBP, and migrated from Asia and possibly Europe to the Americas about 20,000 to 30,000 YBP."

- ^ Adcock GJ, Dennis ES, Easteal S, Huttley GA, Jermiin LS, Peacock WJ, Thorne A (January 2001). "Mitochondrial DNA sequences in ancient Australians: Implications for modern human origins". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 98 (2): 537–542. Bibcode:2001PNAS...98..537A. doi:10.1073/pnas.98.2.537. PMC 14622. PMID 11209053.

- ^ Heupink TH, Subramanian S, Wright JL, Endicott P, Westaway MC, Huynen L, et al. (June 2016). "Ancient mtDNA sequences from the First Australians revisited". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 113 (25): 6892–6897. Bibcode:2016PNAS..113.6892H. doi:10.1073/pnas.1521066113. PMC 4922152. PMID 27274055.

- ^ Parsons, Paul; Dixon, Gail (2016). 50 Ideas You Really Need to Know: Science. London: Quercus. p. 127. ISBN 978-1-78429-614-8.

- ^ Poznik, G. David; Henn, Brenna M.; Yee, Muh-Ching; Sliwerska, Elzbieta; Euskirchen, Ghia M.; Lin, Alice A.; Snyder, Michael; Quintana-Murci, Lluis; Kidd, Jeffrey M.; Underhill, Peter A.; Bustamante, Carlos D. (2 August 2013). "Sequencing Y Chromosomes Resolves Discrepancy in Time to Common Ancestor of Males Versus Females". Science. 341 (6145): 562–565. Bibcode:2013Sci...341..562P. doi:10.1126/science.1237619. ISSN 0036-8075. PMC 4032117. PMID 23908239.

- ^ Scozzari R, Massaia A, D'Atanasio E, Myres NM, Perego UA, Trombetta B, Cruciani F (2012). Caramelli D (ed.). "Molecular dissection of the basal clades in the human Y chromosome phylogenetic tree". PLOS ONE. 7 (11) e49170. Bibcode:2012PLoSO...749170S. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0049170. PMC 3492319. PMID 23145109.

- ^ Mendez FL, Krahn T, Schrack B, Krahn AM, Veeramah KR, Woerner AE, et al. (March 2013). "An African American paternal lineage adds an extremely ancient root to the human Y chromosome phylogenetic tree" (PDF). American Journal of Human Genetics. 92 (3): 454–459. doi:10.1016/j.ajhg.2013.02.002. PMC 3591855. PMID 23453668.

- ^ Mendez FL, Poznik GD, Castellano S, Bustamante CD (April 2016). "The Divergence of Neandertal and Modern Human Y Chromosomes". American Journal of Human Genetics. 98 (4): 728–734. doi:10.1016/j.ajhg.2016.02.023. PMC 4833433. PMID 27058445.

Sources

[edit]- Appenzeller T (2012). "Human migrations: Eastern odyssey. Humans had spread across Asia by 50,000 years ago. Everything else about our original exodus from Africa is up for debate". Nature. 485 (7396).

- Beyin A (2011). "Upper Pleistocene Human Dispersals out of Africa: A Review of the Current State of the Debate". International Journal of Evolutionary Biology. 2011 615094. doi:10.4061/2011/615094. PMC 3119552. PMID 21716744.

- Endicott P, Gilbert MT, Stringer C, Lalueza-Fox C, Willerslev E, Hansen AJ, Cooper A (January 2003). "The genetic origins of the Andaman Islanders". American Journal of Human Genetics. 72 (1): 178–184. doi:10.1086/345487. PMC 378623. PMID 12478481.

- Finlayson C (2009). The humans who went extinct: why Neanderthals died out and we survived. Oxford University Press US. ISBN 978-0-19-923918-4 – via Google Books.

- Groucutt HS, Petraglia MD, Bailey G, Scerri EM, Parton A, Clark-Balzan L, et al. (2015). "Rethinking the dispersal of Homo sapiens out of Africa". Evolutionary Anthropology. 24 (4): 149–164. doi:10.1002/evan.21455. PMC 6715448. PMID 26267436.

- Harding RM, Healy E, Ray AJ, Ellis NS, Flanagan N, Todd C, et al. (April 2000). "Evidence for variable selective pressures at MC1R". American Journal of Human Genetics. 66 (4): 1351–1361. doi:10.1086/302863. PMC 1288200. PMID 10733465.

- Hershkovitz I, Marder O, Ayalon A, Bar-Matthews M, Yasur G, Boaretto E, et al. (April 2015). "Levantine cranium from Manot Cave (Israel) foreshadows the first European modern humans". Nature. 520 (7546): 216–219. Bibcode:2015Natur.520..216H. doi:10.1038/nature14134. PMID 25629628. S2CID 4386123.

- Kuhlwilm M, Gronau I, Hubisz MJ, de Filippo C, Prado-Martinez J, Kircher M, et al. (February 2016). "Ancient gene flow from early modern humans into Eastern Neanderthals". Nature. 530 (7591): 429–433. Bibcode:2016Natur.530..429K. doi:10.1038/nature16544. PMC 4933530. PMID 26886800.

- Liu H, Prugnolle F, Manica A, Balloux F (August 2006). "A geographically explicit genetic model of worldwide human-settlement history". American Journal of Human Genetics. 79 (2): 230–237. doi:10.1086/505436. PMC 1559480. PMID 16826514.

- Liu W, Martinón-Torres M, Cai YJ, Xing S, Tong HW, Pei SW, et al. (October 2015). "The earliest unequivocally modern humans in southern China" (PDF). Nature. 526 (7575): 696–699. Bibcode:2015Natur.526..696L. doi:10.1038/nature15696. hdl:1874/322500. PMID 26466566. S2CID 205246146.

- Macaulay V, Hill C, Achilli A, Rengo C, Clarke D, Meehan W, et al. (May 2005). "Single, rapid coastal settlement of Asia revealed by analysis of complete mitochondrial genomes" (PDF). Science. 308 (5724): 1034–1036. Bibcode:2005Sci...308.1034M. doi:10.1126/science.1109792. PMID 15890885. S2CID 31243109.

- McChesney KY (2015). "Teaching Diversity. The Science You Need to Know to Explain Why Race Is Not Biological". SAGE Open. 5 (4). doi:10.1177/2158244015611712.

- Meredith M (2011). Born in Africa: The Quest for the Origins of Human Life. New York: PublicAffairs. ISBN 978-1-58648-663-1 – via Google Books.

- Posth C, Renaud G, Mittnik A, Drucker DG, Rougier H, Cupillard C, et al. (March 2016). "Pleistocene Mitochondrial Genomes Suggest a Single Major Dispersal of Non-Africans and a Late Glacial Population Turnover in Europe" (PDF). Current Biology. 26 (6): 827–833. Bibcode:2016CBio...26..827P. doi:10.1016/j.cub.2016.01.037. hdl:2440/114930. PMID 26853362. S2CID 140098861.

- Shackelton LA, Rambaut A, Pybus OG, Holmes EC (October 2006). "JC virus evolution and its association with human populations". Journal of Virology. 80 (20): 9928–9933. doi:10.1128/JVI.00441-06. PMC 1617318. PMID 17005670.

- Shen G, Wang W, Wang Q, Zhao J, Collerson K, Zhou C, Tobias PV (December 2002). "U-Series dating of Liujiang hominid site in Guangxi, Southern China". Journal of Human Evolution. 43 (6): 817–829. Bibcode:2002JHumE..43..817S. doi:10.1006/jhev.2002.0601. PMID 12473485.

- Wells S (2003) [2002]. The Journey of Man: A Genetic Odyssey. New York: Random House Trade Paperbacks. ISBN 978-0-8129-7146-0.

Further reading

[edit]- Stringer C (2011). The Origin of Our Species. London: Allen Lane. ISBN 978-1-84614-140-9.

- Wells S (2006). Deep ancestry: inside the Genographic Project. Washington, D.C.: National Geographic. ISBN 978-0-7922-6215-2.

- Wade N (2006). Before the Dawn: Recovering the Lost History of Our Ancestors. Penguin Press. ISBN 978-1-59420-079-3.

- Sykes B (2004). The Seven Daughters of Eve: The Science That Reveals Our Genetic Ancestry. Corgi Adult. ISBN 978-0-552-15218-1.

External links

[edit]- Encyclopædia Britannica, Human Evolution

- Human Timeline (Interactive) – Smithsonian, National Museum of Natural History (August 2016).

- Age constraints for the Trachilos footprints from Crete Nature (October 2021).