Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Human skin

View on Wikipedia

| Human skin | |

|---|---|

| |

| Details | |

| System | Integumentary system |

| Identifiers | |

| Latin | cutis |

| TA98 | A16.0.00.002 |

| TA2 | 7041 |

| TH | H3.12.00.1.00001 |

| FMA | 7163 |

| Anatomical terminology | |

The human skin is the outer covering of the body and is the largest organ of the integumentary system. The skin has up to seven layers of ectodermal tissue guarding muscles, bones, ligaments and internal organs. Human skin is similar to most of the other mammals' skin, and it is very similar to pig skin. Though nearly all human skin is covered with hair follicles, it can appear hairless. There are two general types of skin: hairy and glabrous skin (hairless). The adjective cutaneous literally means "of the skin" (from Latin cutis, skin).

Skin plays an important immunity role in protecting the body against pathogens and excessive water loss. Its other functions are insulation, temperature regulation, sensation, synthesis of vitamin D, and the protection of vitamin B folates. Severely damaged skin will try to heal by forming scar tissue. This is often discoloured and depigmented.

In humans, skin pigmentation (affected by melanin) varies among populations, and skin type can range from dry to non-dry and from oily to non-oily. Such skin variety provides a rich and diverse habitat for the approximately one thousand species of bacteria from nineteen phyla which have been found on human skin.

Structure

[edit]

Human skin shares anatomical, physiological, biochemical and immunological properties with other mammalian lines. Pig skin especially shares similar epidermal and dermal thickness ratios to human skin: pig and human skin share similar hair follicle and blood vessel patterns; biochemically the dermal collagen and elastin content is similar in pig and human skin; and pig skin and human skin have similar physical responses to various growth factors.[1][2]

Skin has mesodermal cells which produce pigmentation, such as melanin provided by melanocytes, which absorb some of the potentially dangerous ultraviolet radiation (UV) in sunlight. It contains DNA repair enzymes that help reverse UV damage. People lacking the genes for these enzymes have high rates of skin cancer. One form predominantly produced by UV light, malignant melanoma, is particularly invasive, causing it to spread quickly, and can often be deadly. Human skin pigmentation varies substantially between populations; this has led to the classification of people(s) on the basis of skin colour.[3]

In terms of surface area, the skin is the second largest organ in the human body (the inside of the small intestine is 15 to 20 times larger). For the average adult human, the skin has a surface area of 1.5–2.0 square metres (15–20 sq ft). The thickness of the skin varies considerably over all parts of the body, and between men and women, and young and old. An example is the skin on the forearm, which is on average 1.3 mm in males and 1.26 mm in females.[4] One average square inch (6.5 cm2) of skin holds 650 sweat glands, 20 blood vessels, 60,000 melanocytes, and more than 1,000 nerve endings.[5][better source needed] The average human skin cell is about 30 μm in diameter, but there are variants. A skin cell usually ranges from 25 to 40 μm2, depending on a variety of factors.

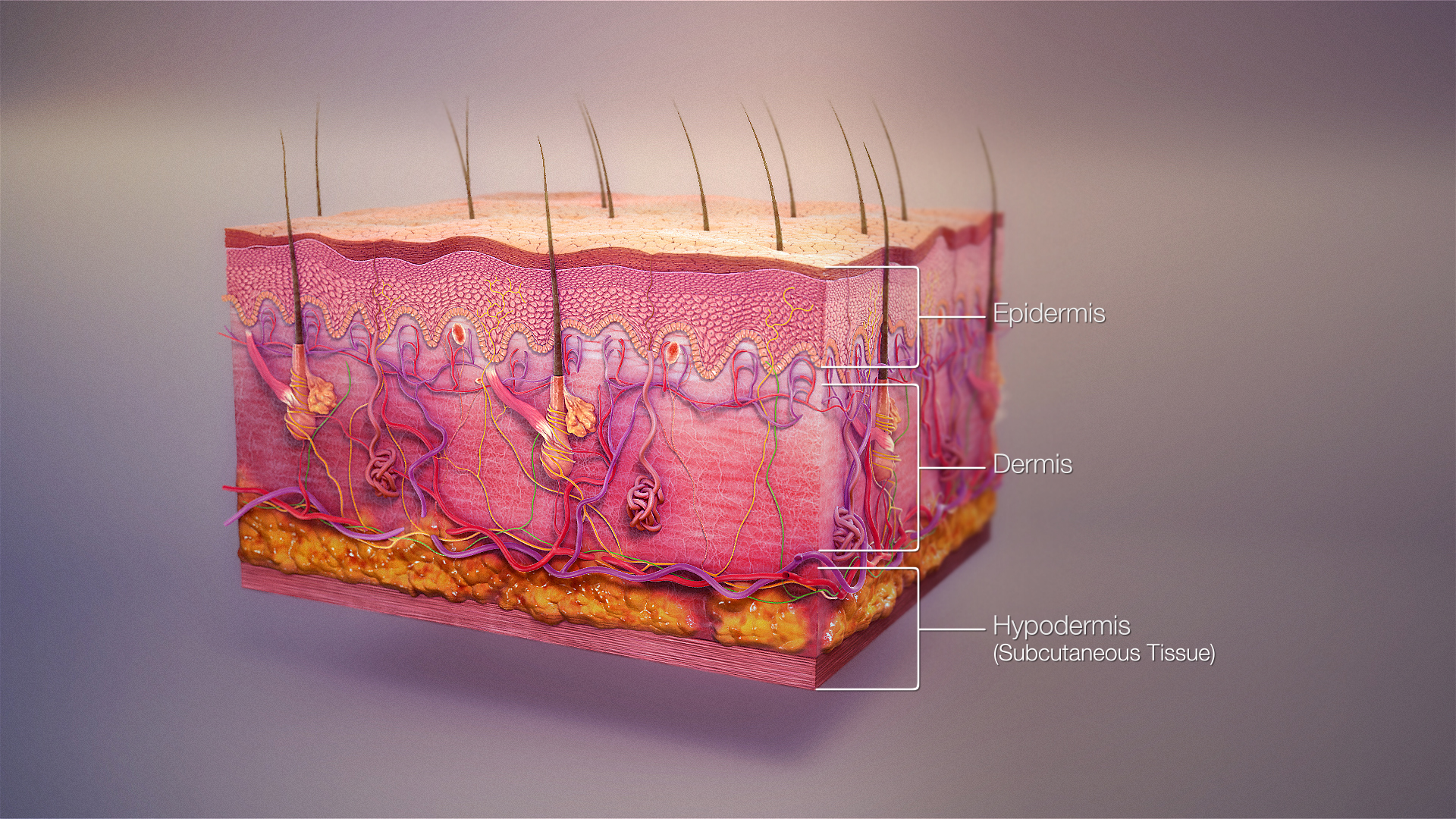

Skin is composed of three primary layers: the epidermis, the dermis and the hypodermis.[4]

Epidermis

[edit]The epidermis, "epi" coming from the Greek language meaning "over" or "upon", is the outermost layer of the skin. It forms the waterproof, protective wrap over the body's surface, which also serves as a barrier to infection and is made up of stratified squamous epithelium with an underlying basal lamina.

The epidermis contains no blood vessels, and cells in the deepest layers are nourished almost exclusively by diffused oxygen from the surrounding air[6] and to a far lesser degree by blood capillaries extending to the outer layers of the dermis. The main type of cells that make up the epidermis are Merkel cells, keratinocytes, with melanocytes and Langerhans cells also present. The epidermis can be further subdivided into the following strata (beginning with the outermost layer): corneum, lucidum (only in palms of hands and bottoms of feet), granulosum, spinosum, and basale. Cells are formed through mitosis at the basale layer. The daughter cells (see cell division) move up the strata changing shape and composition as they die due to isolation from their blood source. The cytoplasm is released and the protein keratin is inserted. They eventually reach the corneum and slough off (desquamation). This process is called "keratinization". This keratinized layer of skin is responsible for keeping water in the body and keeping other harmful chemicals and pathogens out, making skin a natural barrier to infection.[7]

Sublayers

[edit]The epidermis is divided into the following 5 sublayers or strata:

- Stratum corneum

- Stratum lucidum

- Stratum granulosum

- Stratum spinosum

- Stratum basale (also called "stratum germinativum")

Blood capillaries are found beneath the epidermis and are linked to an arteriole and a venule. Arterial shunt vessels may bypass the network in ears, the nose and fingertips.

Genes and proteins expressed in the epidermis

[edit]About 70% of all human protein-coding genes are expressed in the skin.[8][9] Almost 500 genes have an elevated pattern of expression in the skin. There are fewer than 100 genes that are specific for the skin, and these are expressed in the epidermis.[10] An analysis of the corresponding proteins show that these are mainly expressed in keratinocytes and have functions related to squamous differentiation and cornification.

Dermis

[edit]The dermis is the layer of skin beneath the epidermis that consists of connective tissue and cushions the body from stress and strain. The dermis is tightly connected to the epidermis by a basement membrane. It also harbours many nerve endings that provide the sense of touch and heat. It contains the hair follicles, sweat glands, sebaceous glands, apocrine glands, lymphatic vessels and blood vessels. The blood vessels in the dermis provide nourishment and waste removal from its own cells as well as from the stratum basale of the epidermis.

The dermis is structurally divided into two areas: a superficial area adjacent to the epidermis, called the papillary region, and a deep thicker area known as the reticular region.

Papillary region

[edit]The papillary region is composed of loose areolar connective tissue. It is named for its finger-like projections called papillae, which extend toward the epidermis. The papillae provide the dermis with a "bumpy" surface that interdigitates with the epidermis, strengthening the connection between the two layers of skin.

In the palms, fingers, soles, and toes, the influence of the papillae projecting into the epidermis forms contours in the skin's surface. These epidermal ridges occur in patterns (see: fingerprint) that are genetically and epigenetically determined and are therefore unique to the individual, making it possible to use fingerprints or footprints as a means of identification.

Reticular region

[edit]The reticular region lies deep in the papillary region and is usually much thicker. It is composed of dense irregular connective tissue, and receives its name from the dense concentration of collagenous, elastic, and reticular fibres that weave throughout it. These protein fibres give the dermis its properties of strength, extensibility, and elasticity.

Also located within the reticular region are the roots of the hairs, sebaceous glands, sweat glands, receptors, nails, and blood vessels.

Tattoo ink is held in the dermis. Stretch marks, often from adolescent growth spurts, weight gain, pregnancy and obesity, are also located in the dermis.

Subcutaneous tissue

[edit]The subcutaneous tissue (also hypodermis and subcutis) is not part of the skin, but lies below the dermis of the cutis. Its purpose is to attach the skin to underlying bone and muscle as well as supplying it with blood vessels and nerves. It consists of loose connective tissue, adipose tissue and elastin. The main cell types are fibroblasts, macrophages and adipocytes (subcutaneous tissue contains 50% of body fat). Fat serves as padding and insulation for the body.

Cross-section

[edit]Cell count and cell mass

[edit]Skin cell table

[edit]The below table identifies the skin cell count and aggregate cell mass estimates for a 70 kg adult male (ICRP-23; ICRP-89, ICRP-110).[11][12][13]

Tissue mass is defined at 3.3 kg (ICRP-89, ICRP110) and addresses the skin's epidermis, dermis, hair follicles, and glands. The cell data is extracted from 'The Human Cell Count and Cell Size Distribution',[14][15] Tissue-Table tab in the Supporting Information SO1 Dataset (xlsx). The 1200 record Dataset is supported by extensive references for cell size, cell count, and aggregate cell mass.

Detailed data for below cell groups are further subdivided into all the cell types listed in the above sections and categorized by epidermal, dermal, hair follicle, and glandular subcategories in the dataset and on the dataset's graphical website interface.[16] While adipocytes in the hypodermal adipose tissue are treated separately in the ICRP tissue categories, fat content (minus cell-membrane-lipids) resident in the dermal layer (Table-105, ICRP-23) is addressed by the below interstitial-adipocytes in the dermal layer.

| Named tissue and associated cell groups |

Cell count | Aggregate cell mass (g) |

Percent of total mass |

|---|---|---|---|

| Skin total | 6.1E+11 | 846.7 | 100% |

| Adipocyte | 7.3E+08 | 291.9 | 34.5% |

| Endothelial cell (EnCs) | 1.5E+10 | 6.16 | 0.7% |

| Epithelial cells (EpC) | 4.1E+11 | 313.9 | 37.1% |

| Eccrine gland | 1.7E+11 | 105 | 12.4% |

| Epidermal keratinocytes | 1.1E+11 | 85.5 | 10.1% |

| Hair follicle | 1.3E+11 | 119.9 | 14.2% |

| Mechanoreceptors | 4.9E+09 | 3.6 | 0.4% |

| Epithelial cells (EpC); non-nucleated | 7.2E+10 | 28.2 | 3.3% |

| Fibroblasts | 4.3E+10 | 94.6 | 11.2% |

| Myocytes | 2.6E+07 | 0.08 | 0.01% |

| Neuroglia | 8.5E+09 | 12.8 | 1.5% |

| Perivascular cells / Pericytes / Mural | 1.5E+09 | 0.56 | 0.07% |

| Stem cells; epithelial (EpSC) | 3.6E+09 | 1.50 | 0.2% |

| White blood cells | 5.4E+10 | 97.1 | 11.5% |

| Granulocytes (mast cell) | 2.2E+10 | 32.6 | 3.8% |

| Lymphoid | 1.3E+10 | 1.6 | 0.2% |

| Monocyte-macrophage series | 1.9E+10 | 62.9 | 7.4% |

Development

[edit]Skin colour

[edit]Human skin shows high skin colour variety from the darkest brown to the lightest pinkish-white hues. Human skin shows higher variation in colour than any other single mammalian species and is the result of natural selection. Skin pigmentation in humans evolved to primarily regulate the amount of ultraviolet radiation (UVR) penetrating the skin, controlling its biochemical effects.[17]

The actual skin colour of different humans is affected by many substances, although the single most important substance determining human skin colour is the pigment melanin. Melanin is produced within the skin in cells called melanocytes and it is the main determinant of the skin colour of darker-skinned humans. The skin colour of people with light skin is determined mainly by the bluish-white connective tissue under the dermis and by the haemoglobin circulating in the veins of the dermis. The red colour underlying the skin becomes more visible, especially in the face, when, as consequence of physical exercise or the stimulation of the nervous system (anger, fear), arterioles dilate.[18]

There are at least five different pigments that determine the colour of the skin.[19][20] These pigments are present at different levels and places.

- Melanin: It is brown in colour and present in the basal layer of the epidermis.

- Melanoid: It resembles melanin but is present diffusely throughout the epidermis.

- Carotene: This pigment is yellow to orange in colour. It is present in the stratum corneum and fat cells of dermis and superficial fascia.

- Hemoglobin (also spelled haemoglobin): It is found in blood and is not a pigment of the skin but develops a purple colour.

- Oxyhemoglobin: It is also found in blood and is not a pigment of the skin. It develops a red colour.

There is a correlation between the geographic distribution of UV radiation (UVR) and the distribution of indigenous skin pigmentation around the world. Areas that highlight higher amounts of UVR reflect darker-skinned populations, generally located nearer towards the equator. Areas that are far from the tropics and closer to the poles have lower concentration of UVR, which is reflected in lighter-skinned populations.[21]

In the same population it has been observed that adult human females are considerably lighter in skin pigmentation than males. Females need more calcium during pregnancy and lactation, and vitamin D, which is synthesized from sunlight, helps in absorbing calcium. For this reason it is thought that females may have evolved to have lighter skin in order to help their bodies absorb more calcium.[22]

The Fitzpatrick scale[23][24] is a numerical classification schema for human skin colour developed in 1975 as a way to classify the typical response of different types of skin to ultraviolet (UV) light:

| I | Always burns, never tans | Pale, Fair, Freckles |

| II | Usually burns, sometimes tans | Fair |

| III | May burn, usually tans | Light Brown |

| IV | Rarely burns, always tans | Olive brown |

| V | Moderate constitutional pigmentation | Brown |

| VI | Marked constitutional pigmentation | Black |

Ageing

[edit]

As skin ages, it becomes thinner and more easily damaged. Intensifying this effect is the decreasing ability of skin to heal itself as a person ages.

Among other things, skin ageing is noted by a decrease in volume and elasticity. There are many internal and external causes to skin ageing. For example, ageing skin receives less blood flow and lower glandular activity.

A validated comprehensive grading scale has categorized the clinical findings of skin ageing as laxity (sagging), rhytids (wrinkles), and the various facets of photoageing, including erythema (redness), and telangiectasia, dyspigmentation (brown discolouration), solar elastosis (yellowing), keratoses (abnormal growths) and poor texture.[25]

Cortisol causes degradation of collagen,[26] accelerating skin ageing.[27]

Anti-ageing supplements are used to treat skin ageing.[citation needed]

Photoageing

[edit]Photoageing has two main concerns: an increased risk for skin cancer and the appearance of damaged skin. In younger skin, sun damage will heal faster since the cells in the epidermis have a faster turnover rate, while in the older population the skin becomes thinner and the epidermis turnover rate for cell repair is lower, which may result in the dermis layer being damaged.[28]

UV-induced DNA damage

[edit]UV-irradiation of human skin cells generates damages in DNA through direct photochemical reactions at adjacent thymine or cytosine residues on the same strand of DNA.[29] Cyclobutane pyrimidine dimers formed by two adjacent thymine bases, or by two adjacent cytosine bases, in DNA are the most frequent types of DNA damage induced by UV. Humans, as well as other organisms, are capable of repairing such UV-induced damages by the process of nucleotide excision repair.[29] In humans this repair process protects against skin cancer.[29]

Types

[edit]This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (March 2022) |

Though most human skin is covered with hair follicles, some parts can be hairless. There are two general types of skin, hairy and glabrous skin (hairless).[30] The adjective cutaneous means "of the skin" (from Latin cutis, skin).[31]

Functions

[edit]Skin performs the following functions:

- Protection: an anatomical barrier from pathogens and damage between the internal and external environment in bodily defence; Langerhans cells in the skin are part of the adaptive immune system.[7][32] Perspiration contains lysozyme that break the bonds within the cell walls of bacteria.[33]

- Sensation: contains a variety of nerve endings that react to heat and cold, touch, pressure, vibration, and tissue injury; see somatosensory system and haptics.

- Heat regulation: the skin contains a blood supply far greater than its requirements, which allows precise control of energy loss by radiation, convection and conduction. Dilated blood vessels increase perfusion and heat loss, while constricted vessels greatly reduce cutaneous blood flow and conserve heat.

- Control of evaporation: the skin provides a relatively dry and semi-impermeable barrier to fluid loss.[32] Loss of this function contributes to the massive fluid loss in burns.

- Aesthetics and communication: others see skin and can assess mood, physical state and attractiveness.

- Storage and synthesis: acts as a storage centre for lipids and water, as well as a means of synthesis of vitamin D by action of UV on certain parts of the skin.

- Excretion: sweat contains urea, however its concentration is 1/130th that of urine, hence excretion by sweating is at most a secondary function to temperature regulation.

- Absorption: the cells comprising the outermost 0.25–0.40 mm of the skin are "almost exclusively supplied by external oxygen", although the "contribution to total respiration is negligible".[6] In addition, medicine can be administered through the skin, by ointments or by means of adhesive patch, such as the nicotine patch or iontophoresis. The skin is an important site of transport in many other organisms.

- Water resistance: The skin acts as a water-resistant barrier so essential nutrients are not washed out of the body.[32]

Skin flora

[edit]The human skin is a rich environment for microbes.[34][35] Around 1,000 species of bacteria from 19 bacterial phyla have been found.[35][34] Most come from only four phyla: Actinomycetota (51.8%), Bacillota (24.4%), Pseudomonadota (16.5%), and Bacteroidota (6.3%). Propionibacteria and Staphylococci species were the main species in sebaceous areas. There are three main ecological areas: moist, dry and sebaceous. In moist places on the body Corynebacteria together with Staphylococci dominate. In dry areas, there is a mixture of species but dominated by Betaproteobacteria and Flavobacteriales. Ecologically, sebaceous areas had greater species richness than moist and dry ones. The areas with least similarity between people in species were the spaces between fingers, the spaces between toes, axillae, and umbilical cord stump. Most similarly were beside the nostril, nares (inside the nostril), and on the back.

Reflecting upon the diversity of the human skin researchers on the human skin microbiome have observed: "hairy, moist underarms lie a short distance from smooth dry forearms, but these two niches are likely as ecologically dissimilar as rainforests are to deserts."[34]

The NIH conducted the Human Microbiome Project to characterize the human microbiota, which includes that on the skin and the role of this microbiome in health and disease.[36]

Microorganisms like Staphylococcus epidermidis colonize the skin surface. The density of skin flora depends on region of the skin. The disinfected skin surface gets recolonized from bacteria residing in the deeper areas of the hair follicle, gut and urogenital openings.

Clinical significance

[edit]Diseases of the skin include skin infections and skin neoplasms (including skin cancer). Dermatology is the branch of medicine that deals with conditions of the skin.[30]

There are seven cervical, twelve thoracic, five lumbar, and five sacral.[clarification needed] Certain diseases like shingles, caused by varicella-zoster infection, have pain sensations and eruptive rashes involving dermatomal distribution. Dermatomes are helpful in the diagnosis of vertebral spinal injury levels. Aside from the dermatomes, the epidermis cells are susceptible to neoplastic changes, resulting in various cancer types.[37]

The skin is also valuable for diagnosis of other conditions, since many medical signs show through the skin. Skin colour affects the visibility of these signs, a source of misdiagnosis in unaware medical personnel.[38][39][40]

Society and culture

[edit]Hygiene and skin care

[edit]The skin supports its own ecosystems of microorganisms, including yeasts and bacteria, which cannot be removed by any amount of cleaning. Estimates place the number of individual bacteria on the surface of human skin at 7.8 million per square centimetre (50 million per square inch), though this figure varies greatly over the average 1.9 square metres (20 sq ft) of human skin. Oily surfaces, such as the face, may contain over 78 million bacteria per square centimetre (500 million per square inch). Despite these vast quantities, all of the bacteria found on the skin's surface would fit into a volume the size of a pea.[41] In general, the microorganisms keep one another in check and are part of a healthy skin. When the balance is disturbed, there may be an overgrowth and infection, such as when antibiotics kill microbes, resulting in an overgrowth of yeast. The skin is continuous with the inner epithelial lining of the body at the orifices, each of which supports its own complement of microbes.

Cosmetics should be used carefully on the skin because these may cause allergic reactions. Each season requires suitable clothing in order to facilitate the evaporation of the sweat. Sunlight, water and air play an important role in keeping the skin healthy.

Oily skin

[edit]Oily skin is caused by over-active sebaceous glands, that produce a substance called sebum, a naturally healthy skin lubricant.[42][43] A high glycemic-index diet and dairy products (except for cheese) consumption increase IGF-1 generation, which in turn increases sebum production.[43] Overwashing the skin does not cause sebum overproduction but may cause dryness.[43]

When the skin produces excessive sebum, it becomes heavy and thick in texture, known as oily skin.[43] Oily skin is typified by shininess, blemishes and pimples.[42] The oily-skin type is not necessarily bad, since such skin is less prone to wrinkling, or other signs of ageing,[42] because the oil helps to keep needed moisture locked into the epidermis (outermost layer of skin). The negative aspect of the oily-skin type is that oily complexions are especially susceptible to clogged pores, blackheads, and buildup of dead skin cells on the surface of the skin.[42] Oily skin can be sallow and rough in texture and tends to have large, clearly visible pores everywhere, except around the eyes and neck.[42]

Permeability

[edit]Human skin has a low permeability; that is, most foreign substances are unable to penetrate and diffuse through the skin. Skin's outermost layer, the stratum corneum, is an effective barrier to most inorganic nanosized particles.[44][45] This protects the body from external particles such as toxins by not allowing them to come into contact with internal tissues. However, in some cases it is desirable to allow particles entry to the body through the skin. Potential medical applications of such particle transfer has prompted developments in nanomedicine and biology to increase skin permeability. One application of transcutaneous particle delivery could be to locate and treat cancer. Nanomedical researchers seek to target the epidermis and other layers of active cell division where nanoparticles can interact directly with cells that have lost their growth-control mechanisms (cancer cells). Such direct interaction could be used to more accurately diagnose properties of specific tumours or to treat them by delivering drugs with cellular specificity.

Nanoparticles

[edit]Nanoparticles 40 nm in diameter and smaller have been successful in penetrating the skin.[46][47][48] Research confirms that nanoparticles larger than 40 nm do not penetrate the skin past the stratum corneum.[46] Most particles that do penetrate will diffuse through skin cells, but some will travel down hair follicles and reach the dermis layer.

The permeability of skin relative to different shapes of nanoparticles has also been studied. Research has shown that spherical particles have a better ability to penetrate the skin compared to oblong (ellipsoidal) particles because spheres are symmetric in all three spatial dimensions.[48] One study compared the two shapes and recorded data that showed spherical particles located deep in the epidermis and dermis whereas ellipsoidal particles were mainly found in the stratum corneum and epidermal layers.[48] Nanorods are used in experiments because of their unique fluorescent properties but have shown mediocre penetration.

Nanoparticles of different materials have shown skin's permeability limitations. In many experiments, gold nanoparticles 40 nm in diameter or smaller are used and have shown to penetrate to the epidermis. Titanium oxide (TiO2), zinc oxide (ZnO), and silver nanoparticles are ineffective in penetrating the skin past the stratum corneum.[45][49] Cadmium selenide (CdSe) quantum dots have proven to penetrate very effectively when they have certain properties. Because CdSe is toxic to living organisms, the particle must be covered in a surface group. An experiment comparing the permeability of quantum dots coated in polyethylene glycol (PEG), PEG-amine, and carboxylic acid concluded the PEG and PEG-amine surface groups allowed for the greatest penetration of particles. The carboxylic acid coated particles did not penetrate past the stratum corneum.[48]

Increasing permeability

[edit]Scientists previously believed that the skin was an effective barrier to inorganic particles. Damage from mechanical stressors was believed to be the only way to increase its permeability.[50]

Recently, simpler and more effective methods for increasing skin permeability have been developed. Ultraviolet radiation (UVR) slightly damages the surface of skin and causes a time-dependent defect allowing easier penetration of nanoparticles.[51] The UVR's high energy causes a restructuring of cells, weakening the boundary between the stratum corneum and the epidermal layer.[51][50] The damage of the skin is typically measured by the transepidermal water loss (TEWL), though it may take 3–5 days for the TEWL to reach its peak value. When the TEWL reaches its highest value, the maximum density of nanoparticles is able to permeate the skin. While the effect of increased permeability after UVR exposure can lead to an increase in the number of particles that permeate the skin, the specific permeability of skin after UVR exposure relative to particles of different sizes and materials has not been determined.[51]

There are other methods to increase nanoparticle penetration by skin damage: tape stripping is the process in which tape is applied to skin then lifted to remove the top layer of skin; skin abrasion is done by shaving the top 5–10 μm off the surface of the skin; chemical enhancement applies chemicals such as polyvinylpyrrolidone (PVP), dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO), and oleic acid to the surface of the skin to increase permeability;[52][53] electroporation increases skin permeability by the application of short pulses of electric fields. The pulses are high voltage and on the order of milliseconds when applied. Charged molecules penetrate the skin more frequently than neutral molecules after the skin has been exposed to electric field pulses. Results have shown molecules on the order of 100 μm to easily permeate electroporated skin.[53]

Applications

[edit]A large area of interest in nanomedicine is the transdermal patch because of the possibility of a painless application of therapeutic agents with very few side effects. Transdermal patches have been limited to administer a small number of drugs, such as nicotine, because of the limitations in permeability of the skin. Development of techniques that increase skin permeability has led to more drugs that can be applied via transdermal patches and more options for patients.[53]

Increasing the permeability of skin allows nanoparticles to penetrate and target cancer cells. Nanoparticles along with multi-modal imaging techniques have been used as a way to diagnose cancer non-invasively. Skin with high permeability allowed quantum dots with an antibody attached to the surface for active targeting to successfully penetrate and identify cancerous tumours in mice. Tumour targeting is beneficial because the particles can be excited using fluorescence microscopy and emit light energy and heat that will destroy cancer cells.[54]

Sunblock and sunscreen

[edit]Sunblock and sunscreen are different important skin-care products though both offer full protection from the sun.[55]

Sunblock—Sunblock is opaque and stronger than sunscreen, since it is able to block most of the UVA/UVB rays and radiation from the sun, and does not need to be reapplied several times in a day. Titanium dioxide and zinc oxide are two of the important ingredients in sunblock.[56]

Sunscreen—Sunscreen is more transparent once applied to the skin and also has the ability to protect against UVA/UVB rays, although the sunscreen's ingredients have the ability to break down at a faster rate once exposed to sunlight, and some of the radiation is able to penetrate to the skin. In order for sunscreen to be more effective it is necessary to consistently reapply and use one with a higher sun protection factor.

Diet

[edit]Vitamin A, also known as retinoids, benefits the skin by normalizing keratinization, downregulating sebum production, which contributes to acne, and reversing and treating photodamage, striae, and cellulite.

Vitamin D and analogues are used to downregulate the cutaneous immune system and epithelial proliferation while promoting differentiation.

Vitamin C is an antioxidant that regulates collagen synthesis, forms barrier lipids, regenerates vitamin E, and provides photoprotection.

Vitamin E is a membrane antioxidant that protects against oxidative damage and also provides protection against harmful UV rays. [57]

Several scientific studies confirmed that changes in baseline nutritional status affects skin condition. [58]

Mayo Clinic lists foods they state help the skin: fruits and vegetables, whole-grains, dark leafy greens, nuts, and seeds.[59]

See also

[edit]- Acid mantle

- Anthropodermic bibliopegy

- Artificial skin

- Callus – Thick area of skin

- Cutaneous structure development

- Fingerprint – Skin on fingertips

- Human body

- Hyperpigmentation – About excess skin colour

- Intertriginous

- List of cutaneous conditions

- Meissner's corpuscle

- Nude beaches

- Nude swimming

- Nudity

- Pacinian corpuscle

- Polyphenol antioxidant

- Skin cancer

- Skin lesion

- Skin repair

- Sunbathing

References

[edit]- ^ Herron AJ (5 December 2009). "Pigs as Dermatologic Models of Human Skin Disease" (PDF). ivis.org. DVM Center for Comparative Medicine and Department of Pathology Baylor College of Medicine Houston, Texas. Retrieved 27 January 2018.

pig skin has been shown to be the most similar to human skin. Pig skin is structurally similar to human epidermal thickness and dermal-epidermal thickness ratios. Pigs and humans have similar hair follicle and blood vessel patterns in the skin. Biochemically pigs contain dermal collagen and elastic content that is more similar to humans than other laboratory animals. Finally pigs have similar physical and molecular responses to various growth factors.

- ^ Liu J, Kim D, Brown L, Madsen T, Bouchard GF. "Comparison of Human, Porcine and Rodent Wound Healing With New Miniature Swine Study Data" (PDF). sinclairresearch.com. Sinclair Research Centre, Auxvasse, MO, USA; Veterinary Medical Diagnostic Laboratory, Columbia, MO, USA. Archived from the original (PDF) on 27 January 2018. Retrieved 27 January 2018.

Pig skin is anatomically, physiologically, biochemically and immunologically similar to human skin

- ^ Maton A, Hopkins J, McLaughlin CW, Johnson S, Warner MQ, LaHart D, Wright JD (1893). Human Biology and Health. Englewood Cliffs, New Jersey, USA: Prentice Hall. ISBN 978-0-13-981176-0.

{{cite book}}: ISBN / Date incompatibility (help) - ^ a b Wilkinson PF, Millington R (2009). Skin (Digitally printed version ed.). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 49–50. ISBN 978-0-521-10681-8.

- ^ Bennett H (25 May 2014). "Ever wondered about your skin?". The Washington Post. Retrieved 27 October 2014.

- ^ a b Stücker M, Struk A, Altmeyer P, Herde M, Baumgärtl H, Lübbers DW (February 2002). "The cutaneous uptake of atmospheric oxygen contributes significantly to the oxygen supply of human dermis and epidermis". The Journal of Physiology. 538 (Pt 3): 985–994. doi:10.1113/jphysiol.2001.013067. PMC 2290093. PMID 11826181.

- ^ a b Proksch E, Brandner JM, Jensen JM (December 2008). "The skin: an indispensable barrier". Experimental Dermatology. 17 (12): 1063–1072. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0625.2008.00786.x. PMID 19043850. S2CID 31353914.

- ^ "The human proteome in skin – The Human Protein Atlas". www.proteinatlas.org.

- ^ Uhlén M, Fagerberg L, Hallström BM, Lindskog C, Oksvold P, Mardinoglu A, et al. (January 2015). "Proteomics. Tissue-based map of the human proteome". Science. 347 (6220) 1260419. doi:10.1126/science.1260419. PMID 25613900. S2CID 802377.

- ^ Edqvist PH, Fagerberg L, Hallström BM, Danielsson A, Edlund K, Uhlén M, Pontén F (February 2015). "Expression of human skin-specific genes defined by transcriptomics and antibody-based profiling". The Journal of Histochemistry and Cytochemistry. 63 (2): 129–141. doi:10.1369/0022155414562646. PMC 4305515. PMID 25411189.

- ^ Snyder WS, Cook M, Nasset E, Karhausen L, Howells GP, Tipton IH (1975). "ICRP Publication 23: report of the task group on reference man". www.icrp.org. Elmsford, NY: International Commission on Radiological Protection. Retrieved 30 October 2023.

- ^ Valentin J (September 2002). "Basic anatomical and physiological data for use in radiological protection: reference values: ICRP Publication 89". Annals of the ICRP. 32 (3–4): 1–277. doi:10.1016/S0146-6453(03)00002-2. S2CID 222552. Retrieved 30 October 2023.

- ^ Zankl M (2010). "Adult male and female reference computational phantoms (ICRP Publication 110)". Japanese Journal of Health Physics. 45 (4): 357–369. doi:10.5453/jhps.45.357. Retrieved 30 October 2023.

- ^ Hatton IA, Galbraith ED, Merleau NS, Miettinen TP, Smith BM, Shander JA (September 2023). "The human cell count and size distribution". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 120 (39) e2303077120. Bibcode:2023PNAS..12003077H. doi:10.1073/pnas.2303077120. PMC 10523466. PMID 37722043.

- ^ Max Planck Society. "Cellular cartography: Charting the sizes and abundance of our body's cells reveals mathematical order underlying life". medicalxpress.com. Retrieved 30 October 2023.

- ^ "Human Cell data". humancelltreemap.mis.mpg.de. Retrieved 30 October 2023.

- ^ Muehlenbein M (2010). Human Evolutionary Biology. Cambridge University Press. pp. 192–213. ISBN 978-1-139-78900-4.

- ^ Jablonski NG (2006). Skin: a Natural History. Berkeley: University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-95481-6.

- ^ Handbook of General Anatomy by B. D. Chaurasia. ISBN 978-81-239-1654-5

- ^ "Pigmentation of Skin". Mananatomy.com. Archived from the original on 7 October 2012. Retrieved 3 June 2019.

- ^ Webb AR (September 2006). "Who, what, where and when-influences on cutaneous vitamin D synthesis". Progress in Biophysics and Molecular Biology. 92 (1): 17–25. doi:10.1016/j.pbiomolbio.2006.02.004. PMID 16766240.

- ^ Jablonski NG, Chaplin G (July 2000). "The evolution of human skin coloration". Journal of Human Evolution. 39 (1): 57–106. Bibcode:2000JHumE..39...57J. doi:10.1006/jhev.2000.0403. PMID 10896812.

- ^ "The Fitzpatrick Skin Type Classification Scale". Skin Inc. (November 2007). 28 May 2009. Retrieved 7 January 2014.

- ^ "Fitzpatrick Skin Type" (PDF). Australian Radiation Protection and Nuclear Safety Agency. Archived from the original (PDF) on 31 March 2016. Retrieved 7 January 2014.

- ^ Alexiades-Armenakas MR, Dover JS, Arndt KA (May 2008). "The spectrum of laser skin resurfacing: nonablative, fractional, and ablative laser resurfacing". Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology. 58 (5): 719–737. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2008.01.003. PMID 18423256.

- ^ Cutroneo KR, Sterling KM (May 2004). "How do glucocorticoids compare to oligo decoys as inhibitors of collagen synthesis and potential toxicity of these therapeutics?". Journal of Cellular Biochemistry. 92 (1): 6–15. doi:10.1002/jcb.20030. PMID 15095399. S2CID 24160757.(subscription required)

- ^ Oikarinen A (2004). "Connective tissue and aging". International Journal of Cosmetic Science. 26 (2): 107. doi:10.1111/j.1467-2494.2004.213_6.x. ISSN 0142-5463.(subscription required)

- ^ Gilchrest BA (April 1990). "Skin aging and photoaging". Dermatology Nursing. 2 (2): 79–82. PMID 2141531.

- ^ a b c Lee JW, Ratnakumar K, Hung KF, Rokunohe D, Kawasumi M (May 2020). "Deciphering UV-induced DNA Damage Responses to Prevent and Treat Skin Cancer". Photochemistry and Photobiology. 96 (3): 478–499. doi:10.1111/php.13245. PMC 7651136. PMID 32119110.

- ^ a b Marks, James G; Miller, Jeffery (2006). Lookingbill and Marks' Principles of Dermatology. (4th ed.). Elsevier Inc. ISBN 1-4160-3185-5.

- ^ "Definition of CUTANEOUS". www.merriam-webster.com. Retrieved 4 March 2022.

- ^ a b c Madison KC (August 2003). "Barrier function of the skin: "la raison d'être" of the epidermis". The Journal of Investigative Dermatology. 121 (2): 231–241. doi:10.1046/j.1523-1747.2003.12359.x. PMID 12880413.

- ^ Todar K. "Immune Defense against Bacterial Pathogens: Innate Immunity". textbookofbacteriology.net. Retrieved 19 April 2017.

- ^ a b c Grice EA, Kong HH, Conlan S, Deming CB, Davis J, Young AC, et al. (May 2009). "Topographical and temporal diversity of the human skin microbiome". Science. 324 (5931): 1190–1192. Bibcode:2009Sci...324.1190G. doi:10.1126/science.1171700. PMC 2805064. PMID 19478181.

- ^ a b Pappas S. (2009). Your Body Is a Wonderland ... of Bacteria. ScienceNOW Daily News Archived 2 June 2009 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "NIH Human Microbiome Project". Hmpdacc.org. Retrieved 3 June 2019.

- ^ Yousef H, Alhajj M, Sharma S (8 June 2024) [2023]. "Anatomy, Skin (Integument), Epidermis". StatPearls. Treasure Island, FL: StatPearls Publishing. PMID 29262154. Retrieved 28 September 2023.

- ^ "Color Awareness: A Must for Patient Assessment". American Nurse. 11 January 2011.

- ^ McCue D (21 July 2020). "Medical Student Creates Handbook for Diagnosing Conditions in Black and Brown Skin". As It Happens. CBC Radio. Retrieved 15 December 2020.

- ^ Mukwende M, Tamony P, Turner M (2020). Mind the Gap: A Handbook of Clinical Signs in Black and Brown Skin (PDF) (First ed.). London: St George's, University of London. doi:10.24376/rd.sgul.12769988.v1. ISBN 978-1-5272-6908-8. OCLC 1199001123. Archived from the original on 3 October 2020. Retrieved 28 December 2024.

- ^ Theodor Rosebury. Life on Man: Secker & Warburg, 1969 ISBN 0-670-42793-4

- ^ a b c d e "Skin care" (analysis), Health-Cares.net, 2007, webpage: HCcare Archived 12 December 2007 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ a b c d Sakuma TH, Maibach HI (2012). "Oily skin: an overview". Skin Pharmacology and Physiology. 25 (5): 227–235. doi:10.1159/000338978. PMID 22722766. S2CID 2446947.

- ^ Baroli B (January 2010). "Penetration of nanoparticles and nanomaterials in the skin: fiction or reality?". Journal of Pharmaceutical Sciences. 99 (1): 21–50. Bibcode:2010JPhmS..99...21B. doi:10.1002/jps.21817. PMID 19670463.

- ^ a b Filipe P, Silva JN, Silva R, Cirne de Castro JL, Marques Gomes M, Alves LC, et al. (2009). "Stratum corneum is an effective barrier to TiO2 and ZnO nanoparticle percutaneous absorption". Skin Pharmacology and Physiology. 22 (5): 266–275. doi:10.1159/000235554. PMID 19690452. S2CID 25769287.

- ^ a b Vogt A, Combadiere B, Hadam S, Stieler KM, Lademann J, Schaefer H, et al. (June 2006). "40 nm, but not 750 or 1,500 nm, nanoparticles enter epidermal CD1a+ cells after transcutaneous application on human skin". The Journal of Investigative Dermatology. 126 (6): 1316–1322. doi:10.1038/sj.jid.5700226. PMID 16614727.

- ^ a b c d Ryman-Rasmussen JP, Riviere JE, Monteiro-Riviere NA (May 2006). "Penetration of intact skin by quantum dots with diverse physicochemical properties". Toxicological Sciences. 91 (1): 159–165. doi:10.1093/toxsci/kfj122. PMID 16443688.

- ^ Larese FF, D'Agostin F, Crosera M, Adami G, Renzi N, Bovenzi M, Maina G (January 2009). "Human skin penetration of silver nanoparticles through intact and damaged skin". Toxicology. 255 (1–2): 33–37. Bibcode:2009Toxgy.255...33L. doi:10.1016/j.tox.2008.09.025. PMID 18973786.

- ^ a b Mortensen LJ, Oberdörster G, Pentland AP, Delouise LA (September 2008). "In vivo skin penetration of quantum dot nanoparticles in the murine model: the effect of UVR". Nano Letters. 8 (9): 2779–2787. Bibcode:2008NanoL...8.2779M. doi:10.1021/nl801323y. PMC 4111258. PMID 18687009.

- ^ a b c Mortensen L, Zheng H, Faulknor R, De Benedetto A, Beck L, DeLouise LA (2009). Osinski M, Jovin TM, Yamamoto K (eds.). "Increased in vivo skin penetration of quantum dots with UVR and in vitro quantum dot cytotoxicity". Colloidal Quantum Dots for Biomedical Applications IV. 7189: 718919–718919–12. Bibcode:2009SPIE.7189E..19M. doi:10.1117/12.809215. ISSN 0277-786X. S2CID 137060184.

- ^ Sokolov K, Follen M, Aaron J, Pavlova I, Malpica A, Lotan R, Richards-Kortum R (May 2003). "Real-time vital optical imaging of precancer using anti-epidermal growth factor receptor antibodies conjugated to gold nanoparticles". Cancer Research. 63 (9): 1999–2004. PMID 12727808.

- ^ a b c Prausnitz MR, Mitragotri S, Langer R (February 2004). "Current status and future potential of transdermal drug delivery". Nature Reviews. Drug Discovery. 3 (2): 115–124. doi:10.1038/nrd1304. PMID 15040576. S2CID 28888964.

- ^ Gao X, Cui Y, Levenson RM, Chung LW, Nie S (August 2004). "In vivo cancer targeting and imaging with semiconductor quantum dots". Nature Biotechnology. 22 (8): 969–976. doi:10.1038/nbt994. PMID 15258594. S2CID 41561027.

- ^ "Sunblock vs. sunscreen: Which one should you use?". Baylor Scott & White Health. 17 March 2022.

- ^ "Nanotechnology Information Center: Properties, Applications, Research, and Safety Guidelines". American Elements.

- ^ Shapiro SS, Saliou C (October 2001). "Role of vitamins in skin care". Nutrition. 17 (10): 839–844. doi:10.1016/S0899-9007(01)00660-8. PMID 11684391.

- ^ Boelsma E, van de Vijver LP, Goldbohm RA, Klöpping-Ketelaars IA, Hendriks HF, Roza L (February 2003). "Human skin condition and its associations with nutrient concentrations in serum and diet". The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 77 (2): 348–355. doi:10.1093/ajcn/77.2.348. PMID 12540393.

- ^ "Foods for healthy skin". Mayo Clinic.

External links

[edit]- "Skin Conditions". MedlinePlus. U.S. National Library of Medicine. Retrieved 12 November 2013.

Human skin

View on GrokipediaAnatomical Structure

Epidermis

The epidermis is the outermost layer of the skin, consisting of stratified squamous keratinized epithelium that lacks blood vessels and relies on diffusion from the dermis for nutrients.[4] It primarily comprises keratinocytes, which undergo differentiation to form a protective barrier, along with melanocytes, Langerhans cells, and Merkel cells.[4] The epidermis varies in thickness across body regions, ranging from approximately 0.05 mm on the eyelids to 1.5 mm on the palms and soles, reflecting adaptations to mechanical stress and environmental exposure.[4][6] In thin skin, which covers most of the body, the epidermis features four layers: the stratum basale, stratum spinosum, stratum granulosum, and stratum corneum.[4] Thick skin, found on the palms and soles, includes an additional stratum lucidum between the granulosum and corneum.[4] The stratum basale, anchored to the basement membrane, contains stem cells that proliferate to renew the epidermis; above it, the stratum spinosum provides strength via desmosomes, while the stratum granulosum initiates keratinization with keratohyalin granules.[4] The stratum corneum consists of dead, flattened corneocytes filled with keratin, continuously sloughed off to maintain barrier integrity.[4] Keratinocytes constitute about 90% of epidermal cells and follow a lifecycle where basal keratinocytes divide asymmetrically, with daughter cells migrating upward, differentiating over 28 to 40 days, and eventually desquamating as the body sheds roughly 40,000 cells daily.[4][7] Melanocytes, located in the basal layer, produce melanin granules transferred to keratinocytes via dendrites, providing photoprotection; their density is approximately 1 per 10 basal cells in non-sun-exposed areas.[4] Langerhans cells, dendritic immune cells derived from bone marrow, comprise 2-4% of epidermal cells and function in antigen presentation, while Merkel cells, associated with nerve endings, contribute to tactile sensation.[4] This cellular composition and renewal process ensure the epidermis acts as a dynamic barrier against pathogens, UV radiation, and water loss.[4]Dermis

The dermis constitutes the middle layer of human skin, situated beneath the epidermis and overlying the hypodermis, and is primarily composed of dense irregular connective tissue rich in collagen and elastin fibers.[4] It accounts for roughly 90-95% of the total skin thickness, providing structural support, elasticity, and tensile strength to the integument.[7] The dermis harbors vascular networks, sensory nerve endings, lymphatic vessels, and adnexal structures such as hair follicles, sweat glands, and sebaceous glands, which anchor into its matrix.[3] Histologically, the dermis subdivides into two principal strata: the superficial papillary dermis and the deeper reticular dermis, which blend seamlessly without a distinct boundary.[4] The papillary dermis features loosely arranged type III collagen fibers, fine elastic fibers, and a higher density of fibroblasts, macrophages, and mast cells, forming dermal papillae that project upward to interdigitate with the overlying epidermis, enhancing nutrient exchange and mechanical adhesion.[8] In contrast, the reticular dermis contains thicker bundles of type I collagen fibers oriented in a coarse, interwoven network, interspersed with coarser elastin fibers, contributing to the skin's durability and recoil properties.[9] Dermal thickness exhibits regional variation, ranging from approximately 0.6 mm on the eyelids to 3-4 mm on the palms, soles, and dorsal aspects of the trunk, influenced by local mechanical demands and appendage density.[10] Fibroblasts within the dermis synthesize and maintain the extracellular matrix, including glycosaminoglycans that provide hydration and resilience.[11] Sensory structures such as Meissner's corpuscles predominate in the papillary layer, while Pacinian corpuscles reside deeper in the reticular layer, facilitating tactile discrimination and pressure sensation.[12]Hypodermis

The hypodermis, also termed the subcutaneous layer or superficial fascia, represents the deepest cutaneous layer situated beneath the dermis, primarily comprising adipose tissue interspersed with loose connective tissue. This layer anchors the integument to underlying muscles, bones, and organs, facilitating mobility while providing structural support.[3] It consists mainly of adipocytes for fat storage, alongside fibroblasts, macrophages, mast cells, and an extracellular matrix rich in collagen fibers, reticular fibers, and elastin, which contribute to its elasticity and resilience.[13] Blood vessels, lymphatics, and nerves traverse the hypodermis to supply the overlying dermis and epidermis, with larger-caliber vessels originating here.[4] Structurally, the hypodermis exhibits regional variations in organization; in areas such as the abdomen and buttocks, it forms distinct lobules of adipose tissue separated by fibrous septa, whereas in regions like the eyelids and genitalia, it is notably thin and less adipose-rich. Thickness ranges from approximately 0.1 mm in thin-skinned areas to over 30 mm in regions of high fat accumulation, influenced by factors including age, sex, body mass index, and anatomical site.[14] Aging typically leads to thinning of this layer, reducing its insulating capacity and increasing susceptibility to temperature dysregulation.[15] Key physiological roles of the hypodermis include thermoregulation through adipose insulation that minimizes heat loss, energy storage in the form of triglycerides within adipocytes for metabolic reserves, and mechanical shock absorption to protect deeper tissues from trauma.[16] It also aids in hormone production, such as leptin from adipocytes, influencing appetite and energy balance, and supports wound healing by providing a vascular scaffold.[17] Unlike the dermis, the hypodermis lacks epidermal appendages like hair follicles or sweat glands but permits their extension from superficial layers.[3]Skin Appendages

Skin appendages, also known as adnexal structures, are epidermal-derived components of the integumentary system that proliferate downward into the dermis, forming hair follicles, nails, sebaceous glands, and sweat glands; their development begins in the third fetal month from ectodermal downgrowths.[18] Hair follicles are distributed across the body, with approximately 100,000–150,000 on the head (including the scalp); the face has about 20,000 pores, primarily associated with hair follicles and sebaceous glands, and the remainder distributed across other body parts.[19][20] Hair follicles generate keratinized hair shafts consisting of an outer cuticle, central cortex, and optional medulla, with the follicle structured into an upper infundibulum, mid-isthmus, and lower segment enclosing the proliferative hair bulb and inductive dermal papilla.[18] The inner root sheath (with Henle, Huxley, and cuticle layers) and outer root sheath encase the growing hair, enabling cyclic phases of anagen growth, catagen regression, and telogen rest; associated arrector pili muscles and sensory innervation support piloerection for thermoregulation and tactile response.[18][21] Hair primarily protects against UV radiation and mechanical injury, aids in thermoregulation and sensory perception, and serves aesthetic and social signaling functions.[18] Nails form as rigid, translucent plates from the nail matrix's germinative cells, which produce compact, anuclear onychocytes rich in hard keratin but lacking a granular layer; the matrix underlies the proximal nail plate, with the lunula visible as its distal extent and the hyponychium sealing the free edge.[18][21] Nails protect underlying distal phalanges, enhance fine motor tasks like grasping and scratching, amplify tactile sensitivity, and contribute to manual dexterity.[18] Sebaceous glands comprise alveolar lobules of lipid-laden sebocytes that undergo holocrine disintegration to release sebum via short ducts emptying into hair follicles, with secretion regulated by androgens.[18][21] Sebum lubricates skin and hair shafts, forms a hydrophobic barrier against desiccation and pathogens, and exhibits antimicrobial properties through free fatty acids and other components.[18] Sweat glands subdivide into eccrine and apocrine variants, both coiled tubular structures but differing in distribution, activation, and output. Eccrine glands predominate body-wide (except lips and glans), with a secretory coil of clear and dark cells plus myoepithelial contractions in the deep dermis or hypodermis, connected by a straight duct traversing the epidermis to surface pores; they secrete watery, hypotonic fluid containing electrolytes and proteins via merocrine mechanism.[18][21] This sweat facilitates evaporative cooling for thermoregulation, minor excretion of waste, and antimicrobial defense.[18] Apocrine glands concentrate in axillae, groin, areolae, and perianal regions, featuring wider lumens lined by cuboidal epithelium and larger secretory coils in the dermis; dormant until puberty and hormonally responsive, they discharge viscous, protein-rich secretions (potentially odorous upon bacterial breakdown) into follicular canals via apocrine or partial holocrine modes.[18][21] Apocrine output may lubricate associated hair, support bacterial flora modulation, and convey pheromonal signals, though human roles remain less defined than in other mammals.[18]Cellular and Molecular Composition

Major Cell Types

Keratinocytes constitute approximately 90% of the cells in the epidermis and are the primary structural elements responsible for forming the skin's protective barrier through keratin production and desquamation. These cells originate from the basal layer, undergo differentiation as they migrate upward, and flatten into corneocytes in the stratum corneum, which are filled with keratin filaments cross-linked by disulfide bonds for mechanical strength.[22] Melanocytes, located in the basal layer of the epidermis at a ratio of about 1 per 10 keratinocytes, synthesize melanin within melanosomes and transfer these organelles via dendrites to adjacent keratinocytes, providing photoprotection against ultraviolet radiation and determining skin pigmentation through eumelanin and pheomelanin production.[22][4] Langerhans cells, dendritic immune cells comprising 2-4% of epidermal cells, originate from bone marrow precursors and reside primarily in the stratum spinosum; they express MHC class II molecules, capture antigens via pattern recognition receptors, and migrate to lymph nodes to initiate T-cell responses, serving as sentinels against pathogens.[4][22] Merkel cells, mechanosensory cells found in the basal epidermis often associated with hair follicles and touch domes, function as slowly adapting type I mechanoreceptors; they form synaptic complexes with sensory nerve endings and express neuroendocrine markers like cytokeratin 20, contributing to fine tactile discrimination.[4] In the dermis, fibroblasts are the predominant resident cells, synthesizing and remodeling extracellular matrix components such as type I and III collagen, elastin, and proteoglycans to maintain structural integrity and facilitate wound healing through cytokine secretion and matrix metalloproteinase activity.[23] Dermal immune cells, including macrophages (histiocytes) and mast cells, support innate immunity; macrophages phagocytose debris and present antigens, while mast cells release histamine and other mediators in response to IgE-mediated triggers, influencing vascular permeability and inflammation.[23] Endothelial cells line dermal blood vessels, regulating nutrient exchange and leukocyte trafficking via adhesion molecules like ICAM-1 and VCAM-1 during inflammatory responses.[24] In the hypodermis, adipocytes predominate, storing triglycerides for energy reserves and cushioning; these cells also secrete adipokines influencing metabolism and insulation, with white adipocytes being the primary type in adult human skin.[22]Extracellular Matrix and Proteins

The extracellular matrix (ECM) of human skin, primarily located in the dermis but also forming the basement membrane at the dermal-epidermal junction, consists of a network of fibrous proteins, glycoproteins, and proteoglycans that provide mechanical strength, elasticity, hydration, and signaling cues for cellular interactions. In the dermis, ECM components constitute approximately 90% of the tissue's dry weight, with collagens forming the dominant scaffold.[25] This matrix supports fibroblast activity, regulates tissue homeostasis, and facilitates wound repair, while its composition varies slightly across skin regions and with age.[26] Collagens are the most abundant proteins in dermal ECM, accounting for 70-80% of the dry weight, with type I collagen comprising the majority (approximately 80% of total collagen) to confer tensile strength and structural integrity through fibrillar assembly. Type III collagen, present at 10-15%, interweaves with type I fibrils to enhance flexibility and resilience, particularly in reticular fibers. Minor collagens, such as types V and VI, modulate fibril diameter and associate with cellular surfaces. In the basement membrane, type IV collagen forms a non-fibrillar network essential for anchoring the epidermis, self-assembling into sheets with isoforms including α1, α2, α5, and α6 chains.[26][25][27] Elastic fibers, composed of elastin (2-4% of dermal dry weight) cross-linked with microfibrils like fibrillin, enable skin recoil and viscoelasticity, preventing permanent deformation under mechanical stress. Glycoproteins such as fibronectin organize the matrix by binding integrins and collagens, promoting cell adhesion and migration during development and repair. Laminins, particularly laminin-511 in skin, polymerize in the basement membrane to initiate network assembly and support keratinocyte adhesion via integrin receptors.[26][26] Proteoglycans and associated glycosaminoglycans (GAGs) fill interstitial spaces, binding water to maintain hydration and regulate collagen fibrillogenesis. Decorin, the most abundant dermal proteoglycan with chondroitin/dermatan sulfate chains, binds type I collagen to control fibril spacing and modulates transforming growth factor-β signaling. Other key proteoglycans include versican (chondroitin sulfate, for viscoelasticity), biglycan (dermis and basement membrane, for growth factor sequestration), lumican (keratan sulfate, for fibril organization), and perlecan (heparan/chondroitin sulfate in basement membrane, linking laminin and collagen IV networks). Non-sulfated hyaluronan, a major GAG, interacts with proteoglycans to form hydrated gels, aiding epidermal-dermal separation and cell motility.[28][25][28]Genetic Expression Patterns

The human skin transcriptome encompasses expression of 14,224 proteins, representing 71% of the total human proteome, with 602 genes exhibiting elevated expression relative to other tissues.[29] Genome-wide transcriptomic profiling of skin biopsies has identified 417 genes with enriched expression in skin, including 106 genes upregulated at least five-fold compared to non-skin tissues, many of which encode proteins critical for barrier formation and structural integrity.[30] These patterns arise from the stratified architecture of skin, where gene expression differentiates sharply between the epidermis, dermis, and hypodermis to support specialized functions such as mechanical resilience and lipid storage.[31] In the epidermis, keratinocytes dominate gene expression, with high levels of keratin genes like KRT5 and KRT14 in the basal layer transitioning to KRT1 and KRT10 in suprabasal layers, facilitating cytoskeletal support and differentiation.[32] Barrier-related genes such as FLG (filaggrin), LOR (loricrin), and desmosomal components (DSG1, DSC1) peak in the stratum corneum, enabling cornification and waterproofing.[30] Single-cell RNA sequencing reveals four spatially distinct basal stem cell populations in the interfollicular epidermis, each with unique expression signatures involving proliferation markers (MKI67) and adhesion molecules.[32] Dermal fibroblasts display layer-specific heterogeneity, with papillary fibroblasts expressing genes like APCDD1, AXIN2, COLEC12, PTGDS, and COL18A1 for provisional matrix support, while reticular fibroblasts upregulate structural extracellular matrix components such as COL1A1, COL3A1, and ELN (elastin) for tensile strength.[33] Transcriptomic analyses confirm diurnal oscillations in both epidermal and dermal layers, with rhythms in clock genes (PER1, CLOCK) and metabolic pathways influencing up to 10% of expressed genes in healthy adults.[34] Hypodermal adipocytes contribute genes involved in lipid biosynthesis and insulation, such as FABP4 and PPARG, which modulate overlying dermal expression through paracrine signaling.[31] Cell-type-specific patterns further delineate skin function: melanocytes highly express melanin synthesis genes (MLANA, DCT, TYR), while Langerhans cells and resident T cells show immune surveillance markers like CD1A and CD69.[29] Recent single-cell atlases across anatomical sites highlight regional Hox gene gradients (HOXC13 in scalp, HOXD13 in distal limbs) driving site-specific expression, underscoring developmental origins of these patterns.[35] Such profiles, validated via immunohistochemistry and RNA sequencing, reveal minimal inter-subject variability in core patterns but sensitivity to aging and environmental factors.[30][33]Physiological Functions

Physical Barrier and Protection

The stratum corneum functions as the skin's principal physical barrier, comprising 15-20 layers of anucleate corneocytes filled with keratin filaments and surrounded by intercellular lipids including ceramides, cholesterol, and free fatty acids organized into lamellar sheets.[36] This structure, often described as a "bricks and mortar" model where corneocytes act as bricks and lipids as mortar, restricts transepidermal water loss to approximately 5-10 g/m²/h under normal conditions, preventing dehydration while blocking the ingress of hydrophilic and lipophilic xenobiotics, allergens, and microorganisms.[37] [38] Tight junctions in the stratum granulosum layer of the viable epidermis provide a complementary paracellular seal, composed of proteins such as claudins, occludins, and zonula occludens, which limit diffusion of ions, water, and solutes, thereby reinforcing the barrier against environmental insults.[39] Desmosomal attachments between corneocytes further enhance mechanical cohesion, distributing shear forces and resisting abrasion from physical trauma.[40] The barrier also confers protection against ultraviolet radiation through scattering and absorption by corneocyte keratin and, to a lesser extent, by melanin pigments transferred from melanocytes to keratinocytes, reducing penetration of UVB (280-320 nm) wavelengths that cause DNA damage.[41] The skin's surface acidity, maintained at pH 4.5-5.5 by dissociated fatty acids and other metabolites, creates an "acid mantle" that inhibits proliferation of pathogenic bacteria such as Staphylococcus aureus while favoring commensal flora.[42] In addition to passive physical exclusion, the barrier integrates active defenses; disruption of the stratum corneum, as occurs in conditions like atopic dermatitis, correlates with increased permeability and susceptibility to infections, underscoring its role in innate immunity.[43] Keratinocytes within the epidermis produce antimicrobial peptides, including cathelicidin LL-37 and human β-defensins, which are secreted into the intercellular space to lyse microbes that compromise the physical integrity.[44][39]Thermoregulation and Sensation

The skin maintains core body temperature through integrated mechanisms involving vascular control, sweat production, and insulation. During heat stress, cutaneous vasodilation mediated by sympathetic nerves increases skin blood flow up to 8 liters per minute, enabling radiative and convective heat loss equivalent to several times the resting metabolic rate.[45] Simultaneously, eccrine sweat glands, numbering approximately 2-4 million across the body surface, secrete hypotonic fluid at rates exceeding 2 liters per hour under maximal stimulation; its evaporation absorbs 2430 kJ per liter of heat from the skin.[46] In cold conditions, arteriolar vasoconstriction reduces peripheral blood flow by over 90%, conserving heat, while subcutaneous adipose tissue provides thermal insulation with conductivity as low as 0.2 W/m·K.[46] Basal insensible perspiration contributes 600-700 mL of water loss daily, supporting ongoing evaporative cooling even without overt sweating.[46] Skin sensation arises from specialized free nerve endings and encapsulated receptors distributed across epidermal and dermal layers, transducing environmental stimuli into neural signals via primary afferents. Mechanoreceptors predominate for tactile discrimination: Meissner corpuscles in dermal papillae detect transient light touch and low-frequency vibrations (2-50 Hz); Merkel cell-neurite complexes sustain fine spatial resolution for texture and pressure; Pacinian corpuscles sense deep pressure and high-frequency vibrations (>100 Hz); and Ruffini endings register skin stretch and sustained indentation.[47] Thermoreceptors, primarily unmyelinated C-fibers and thinly myelinated Aδ-fibers, include cold-sensitive spots peaking at 25°C and warm-sensitive at 40°C, with receptive fields spanning millimeters to centimeters.[48] Nociceptors, comprising polymodal C-fibers (responding to heat >43°C, cold <5°C, mechanical pinch, and irritants) and Aδ high-threshold mechanothermal fibers, initiate protective withdrawal reflexes and pain perception upon tissue-threatening stimuli.[49] Receptor density varies regionally—fingertips host over 100 mechanoreceptors per cm² versus <10 on the back—enabling adaptive sensitivity, with glabrous skin emphasizing precision touch and hairy skin integrating itch via pruriceptors.[47] These somatosensory inputs integrate in the spinal cord and thalamus, contributing to conscious perception and autonomic thermoregulatory adjustments.[46]Metabolic and Immune Roles

The human skin performs key metabolic functions, including the synthesis of vitamin D3, where ultraviolet B radiation (290–315 nm) converts 7-dehydrocholesterol in epidermal keratinocytes to previtamin D3, which thermally isomerizes to vitamin D3 (cholecalciferol) before release into circulation.[50] This process accounts for approximately 80–100% of endogenous vitamin D production in sun-exposed individuals, varying by factors such as skin pigmentation, latitude, and age, with darker skin requiring longer exposure due to higher melanin content absorbing UVB.[51] Skin also contributes to lipid metabolism by producing ceramides, cholesterol, and free fatty acids in keratinocytes via enzymes like elongases and desaturases, forming the stratum corneum's permeability barrier that prevents transepidermal water loss and supports antimicrobial defense.[52] Additionally, epidermal cells metabolize amino acids for protein synthesis in structural components such as keratin and filaggrin, with mitochondria in keratinocytes and fibroblasts driving ATP production essential for cellular maintenance and repair.[53][54] In immune roles, the skin acts as a frontline barrier through constitutive and inducible production of antimicrobial peptides (AMPs) by keratinocytes, including human β-defensins (hBD-1 to hBD-4) and cathelicidin (LL-37), which disrupt microbial membranes and recruit immune cells via chemokine activity.[55] These AMPs are upregulated in response to pathogens or injury through pathways like Toll-like receptors, providing rapid chemical defense independent of adaptive immunity.[56] Langerhans cells, dendritic cells comprising 3–5% of epidermal nucleated cells, serve as antigen-presenting sentinels, capturing antigens via dendrites extending through tight junctions and migrating to lymph nodes to initiate T-cell responses or promote tolerance in steady-state conditions.[57][58] Keratinocytes further coordinate immunity by secreting cytokines (e.g., IL-1, TNF-α) and expressing MHC class II molecules during inflammation, bridging innate and adaptive responses while dermal immune cells like mast cells and macrophages amplify clearance of invaders.[59] This integrated system maintains homeostasis, with disruptions linked to conditions like atopic dermatitis from reduced AMP expression.[55]Microbiome Interactions

The human skin microbiome comprises a diverse community dominated by bacteria from the phyla Actinobacteria (e.g., Cutibacterium acnes), Firmicutes (e.g., Staphylococcus epidermidis), and Proteobacteria (e.g., Corynebacterium spp.), with compositions varying by skin niche: sebaceous areas favor Cutibacterium, moist sites like the axilla favor Corynebacterium, and dry sites like the forearm exhibit higher diversity.[60] These commensals interact symbiotically with host cells, providing colonization resistance via resource competition, biofilm disruption, and antimicrobial production; for instance, S. epidermidis secretes serine protease Esp to dismantle S. aureus biofilms and bacteriocins like epidermin, pep5, and epilancin K7 to inhibit pathogens including MRSA.[61] Similarly, C. acnes produces propionic acid and cutimycin, suppressing S. aureus growth through short-chain fatty acid-mediated acidification and direct antimicrobial activity.[61] Microbe-host crosstalk modulates innate immunity, with commensals stimulating keratinocytes via Toll-like receptor 2 (TLR2) to upregulate antimicrobial peptides such as β-defensins and cathelicidins, enhancing barrier defense without excessive inflammation.[60] S. epidermidis lipoteichoic acid activates TLR2 to recruit and mature mast cells, while also dampening TLR3-driven proinflammatory responses post-injury, thereby preserving homeostasis.[62] These interactions extend to adaptive immunity, where early-life microbiota induce commensal-specific regulatory T cells via CD301+ dendritic cells for tolerance, and present microbial metabolites (e.g., glycolipids via CD1d or riboflavin via MR1) to foster innate-like T cells like NKT and MAIT cells.[62] In physiological contexts, such dynamics support wound healing by activating keratinocyte aryl hydrocarbon receptor (AhR) pathways for barrier repair and limit pathogen invasion; diverse communities reduce S. aureus colonization in mouse models by boosting innate defenses.[62][61] Host factors like sebum lipids and pH further stabilize these equilibria, with S. epidermidis phenol-soluble modulins selectively targeting pathogens while sparing host tissues.[60] Disruptions, though beyond core homeostasis, underscore the microbiome's role in sustaining immune vigilance and epidermal integrity.[60]Developmental Biology

Embryonic Formation

The embryonic formation of human skin originates from the ectoderm and mesoderm germ layers established during gastrulation in the third week of development. The epidermis derives from the surface ectoderm, while the dermis arises from mesenchymal cells of the mesoderm, including contributions from the lateral plate mesoderm and somitic dermatomes.[63][64] The hypodermis, or subcutaneous layer, forms later from mesodermal mesenchyme, providing insulation and fat storage as the embryo matures.[4] By the end of the fourth week, the surface ectoderm separates from the neural tube, forming a single-layered epithelium that constitutes the primitive epidermis.[63] This layer initially consists of cuboidal cells expressing keratins K5 and K14, marking commitment to epidermal lineage.[65] Mesenchymal cells migrate beneath the ectoderm around the same period, condensing to form the early dermis and initiating production of extracellular matrix components such as collagen types I and III.[66] Stratification of the epidermis begins around the eighth week, with the formation of a transient periderm layer overlying the basal keratinocytes to protect against amniotic fluid.[63] Intermediate layers emerge by the tenth to twelfth weeks, driven by signals like BMP and Wnt pathways that promote progenitor proliferation and differentiation into spinous and granular layers.[65] Concurrently, the dermis develops papillary and reticular subdivisions by the third month, with fibroblasts synthesizing fibronectin and laminin to anchor the epidermis via a basement membrane.[67] Appendage primordia, such as hair follicles and glands, initiate from epidermal placodes interacting with dermal condensates starting in the ninth week, regulated by epithelial-mesenchymal signaling involving FGF and Shh pathways.[65] By the end of the first trimester, the skin achieves a multilayered structure resembling the adult form, though cornification and barrier function mature postnatally.[64] These processes ensure the skin's role as a protective interface from early organogenesis.[68]Postnatal Maturation

The human skin at birth transitions from an aqueous intrauterine environment to air exposure, initiating rapid postnatal adaptations primarily in barrier function and hydration. In term infants, the stratum corneum consists of 10-15 cell layers, providing a competent initial barrier coated by vernix caseosa, which sheds within hours to days post-delivery, exposing the skin to environmental stressors and prompting keratinocyte differentiation.[69] Preterm infants born before 34 weeks gestation exhibit immature epidermis with only 2-3 stratum corneum layers, resulting in elevated transepidermal water loss (TEWL) rates—often exceeding 50 g/m²/h compared to adult levels of 5-10 g/m²/h—and heightened vulnerability to dehydration and infection.[69] [70] Postnatally, TEWL in preterm neonates decreases exponentially, approximating term infant levels within 2-3 weeks through accelerated corneocyte extrusion and lipid matrix compaction.[69] Dermal maturation involves reorganization of the extracellular matrix, with preterm neonates displaying edematous papillary dermis, sparse and immature collagen fibrils (diameter ~40 nm versus ~100 nm in adults), and underdeveloped anchoring fibrils at the dermo-epidermal junction.[69] Over the first months, collagen deposition increases, fibril diameter enlarges, and elastic fibers elongate, enhancing tensile strength and elasticity; by 6-12 months, dermal thickness approaches adult proportions in term infants.[69] Epidermal thickness, initially 30-50% thinner in infants than adults, thickens progressively via keratinocyte proliferation, reaching adult-like values (~100 μm) by approximately 6 years.[71] Skin surface pH, alkaline at birth (6.34-7.5) due to amniotic fluid residues, acidifies within the first postnatal week to 5.5-6.0 in term infants, driven by free fatty acids from vernix hydrolysis and microbial colonization, establishing the antimicrobial acid mantle.[69] This shift lags in preterm skin, correlating with delayed barrier integrity. Sebaceous gland activity peaks neonatally from maternal androgen influence, yielding sebum levels up to 10-fold higher than in older children, before regressing sharply by 6 months and remaining low until puberty.[69] Eccrine sweat glands, structurally present from mid-gestation, function immaturely at birth; thermoregulatory sweating emerges by 2 weeks in term infants, while full emotional and gustatory responses develop over the first 1-2 years.[69] Stratum corneum properties refine beyond infancy: corneocyte size, smaller in neonates (~600 μm² versus ~1000 μm² in adults), enlarges by age 6 years, coinciding with reduced TEWL and increased lipid compactness for sustained barrier efficacy.[71] Hydration levels transiently exceed adult norms between 3-12 months due to elevated natural moisturizing factors, then stabilize.[69] By 6-10 years, most structural and functional metrics—epidermal renewal rate, dermal vascular density, and sebum composition—align with adult skin, though microbiome integration and immune effector density continue evolving into adolescence.[71] These changes underpin reduced permeability and enhanced resilience, with deviations in preterm cohorts often mitigated by environmental humidity and emollient support.[72]Pigmentation Development

Melanocytes, the pigment-producing cells responsible for skin coloration, originate from neural crest-derived melanoblasts during early embryogenesis. Neural crest cells form around the third week of gestation, with melanoblast specification occurring progressively as pluripotent precursors commit to the melanogenic lineage under the influence of transcription factors such as MITF (microphthalmia-associated transcription factor).[73] [74] These melanoblasts migrate dorsolaterally through the developing embryo, reaching the epidermal basal layer by approximately 8 to 10 weeks of gestation in humans, where they differentiate into mature melanocytes.[75] This migration is guided by signaling pathways including KIT ligand and endothelin-3, ensuring proper distribution to the epidermis, hair follicles, and other sites.[76] Upon reaching the skin, melanocytes begin synthesizing melanin within melanosomes, organelles that mature through four stages: formation, enzymatic activation of tyrosinase, melanin deposition, and transfer to keratinocytes.[77] Eumelanin (brown-black) and pheomelanin (red-yellow) production ratios determine baseline pigmentation, with genetic variants in genes like MC1R influencing the balance from fetal stages.[78] By the second trimester, functional melanocytes are evident in fetal skin, though melanin content remains low until postnatal activation.[79] Premature infants exhibit even lighter pigmentation due to incomplete maturation, highlighting the role of gestational age in establishing initial melanin levels.[80] Postnatally, skin pigmentation undergoes maturation as constitutive melanin production increases, typically reaching adult levels by 2 to 3 years of age, with infants born relatively hypopigmented compared to their genetic potential.[81] This development involves enhanced melanocyte proliferation, melanosome transfer efficiency, and responsiveness to ultraviolet radiation, which stimulates tyrosinase activity via p53-mediated pathways.[82] Hormonal factors, such as androgens during puberty, further modulate pigmentation density, while evolutionary adaptations link darker baseline tones to higher UV exposure histories through selection on genes like SLC24A5.[83] Disruptions in this process, as seen in conditions like piebaldism from KIT mutations, underscore the sequential dependence on embryonic migration and postnatal regulation for uniform pigmentation.Biological Variations

Sex-Based Differences