Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Tabo Monastery

View on Wikipedia

Tabo Monastery (or Tabo Chos-Khor Monastery[1]) is located in the Tabo village of Spiti Valley, Himachal Pradesh, northern India. It was founded in 996 CE in the Tibetan year of the Fire Ape[2] by the Tibetan Buddhist lotsawa (translator) Rinchen Zangpo (Mahauru Ramabhadra), on behalf of the king of western Himalayan Kingdom of Guge, Yeshe-Ö.[2] Tabo is noted for being the oldest continuously operating Buddhist enclave in both India and the Himalayas.[3] A large number of frescoes displayed on its walls depict tales from the Buddhist pantheon.[4] There are many priceless collections of thankas (scroll paintings), manuscripts, well-preserved statues, frescos and extensive murals which cover almost every wall. The monastery is in need of refurbishing as the wooden structures are aging and the thanka scroll paintings are fading.[5] After the earthquake of 1975, the monastery was rebuilt, and in 1983 a new Du-kang or Assembly Hall was constructed. It is here that the 14th Dalai Lama held the Kalachakra ceremonies in 1983 and 1996.[6][7] The monastery is protected by the Archaeological Survey of India (ASI) as a national historic treasure of India.[7]

Key Information

Geography

[edit]

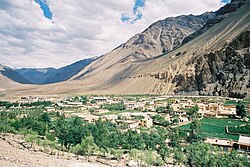

The monastery is situated in the Spiti valley (an isolated valley with a total population of 10,000) above Tabo village on the left bank of the Spiti River. The valley as such is delimited by Ladakh in the north, Lahaul and Kullu districts in the west and south-east respectively, and by Tibet and the Kinnaur district in the east. While Tabo village is in a bowl-shaped flat valley, the monastery is also in the bottom of the valley, unlike other monasteries in the valley, which are perched on hills; in the past the region was part of Tibet. It is located in a very arid, cold and rocky area at an altitude of 3,050 metres (10,010 ft).[7][8] Above the monastery there are a number of caves carved into the cliff face and used by monks for meditation.[6] There is also an assembly hall in the caves and some faded paintings on the rock face.[9]

History

[edit]Early history

[edit]

The monastery was built by the Buddhist king (also known as Royal Lama) Yeshe-Ö in 996 A.D. It was renovated 46 years later by the royal priest Jangchub O'd, the grandnephew of Yeshe-Ö. They were kings of the Purang-Guge kingdom whose ancestry is traced to the ancient Tibetan monarchy, and extended their kingdom from Ladakh to Mustang by building a large network of trade routes, and built temples along the route. Tabo was built as a 'daughter' monastery of the Tholing Monastery in Ngari, western Tibet. This royal dynasty was instrumental in re-introducing the Indian Mahayana Buddhism in Tibet, the second major spreading of Buddhism in Tibetan history. They contributed richly to the political, religious and economic institutions of Tibet in the 11th century through the building of Tabo Monastery; this is documented in the writing on the walls of Tabo.

The iconographic depictions are reported to be of 1042 and later, consisting of paintings, sculptures, inscriptions and extensive wall texts.[10] The translator Rinchen Zangpo, a Tibetan lama from western Tibet, who was chiefly responsible for translating Sanskrit Buddhist texts into Tibetan, was the preceptor to King Yeshe-Ö who helped in the missionary activities. Several Indian pundits visited Tabo to learn the Tibetan language.[11]

Late 17th to 19th centuries

[edit]

During the 17th-19th centuries, the monastery and the bridge across the Spiti River witnessed historical events[6] and political turmoil in the area. Manuscripts such as Tabo Kanjur make mention of some violent confrontations. An inscription of 1837 records attacks on the Tabo Assembly Hall in 1837, which can also visually be seen by damages to some parts of the walls. The attack is attributed to 'Rinjeet's troops' who were under the kings of Ladakh. With the British Rule from 1846, the area enjoyed peace until the 1950s when the Indo-China border disputes reawakened the political claims of the border posts.[11] In 1855, Tabo had 32 monks.[12]

Modern era

[edit]

The original monastery was severely damaged in the 1975 Kinnaur earthquake. Subsequent to its full restoration and the addition of new structures, the 14th Dalai Lama visited the monastery and initiated the Kalachakra Festival (a process of initiation and rejuvenation) in 1983, after the Kalachakra Temple was built. He also revisited in 1996 when the millennium of its existence was celebrated and has returned on numerous occasions.[1][2][13] In 2009, the Dalai Lama was scheduled to inaugurate the Kalachakra Stupa, which has been built as an auspicious symbol, following the special blessings of Kalachakra he had performed earlier.[13] Sakya Trizin and other Tibetan teachers and meditation masters have also visited the monastery and encouraged the Buddhist practice among the local people.

The monastery has 45 monks.[13] Kyabje Serkong Tsenshap Rinpoche (1914–1983) served as the Head Lama prior to Geshe Sonam Wangdui, who became the Abbot of Tabo Monastery since 1975. His responsibilities include caring for the monastery and monks, teaching Buddhist scripture, and looking after the local community. Current Serkong Tsenshap Rinpoche is the spiritual head of the monastery.

Tabo is protected by the ASI as a national historic treasure of India.[7] As such, ASI encourages heritage tourism to this site.[4] ASI had also proposed this monastery, the only monolithic structure of its kind in North India, for recognition as a UNESCO World Heritage Site for its sanctity in Trans Himalayan Buddhism.[14] In 2002, ASI carried out replacement of the large beam, 10 by 10 inches (250 mm × 250 mm), by 4 feet (1.2 m) in length, made of Deodar, which supported the roof of the main hall of the old monastery, with a Sal timber beam as Deodor of that size could not be located.[15]

Architecture and fittings

[edit]

Tabo Monastery (Tabo 'Chos-hKhor' or Doctrinal Enclave[14]) now has nine temples, four decorated stupas, and cave shrines. The paintings date to the 10th-11th centuries for main temple (Tsug la Khang), 13th-14th centuries for the stupas, and from the 15th to the 20th centuries for all the other temples. Yeshe-Ö and his two sons when they built the monastery in 996 AD blended the provincial and regional characteristics with that of India and Central Asia. One particular feature mentioned in this regard is the iconographic themes of non-Buddhist traditions emanating from the protectress deity Wi-nyu-myin. The main temple is conjectured to represent the entire Vajradhatu Mandala.The monastery has a huge collection of manuscripts and Pramana texts, which were filmed between 1991 and 1998.[16]

Main temple

[edit]The main temple has an entry hall (Go Khang), followed by an Assembly Hall (Du Khang). At the western end of the assembly hall there is an apse (recessed area), which has a cella or shrine area (Ti Tsang Khang) with an ambulatory (Kor lam Khang) passage. The entry hall has pictures of Yeshe-Ö and his two sons Nagaraja and Devaraja, the founders of the temple, on its south wall. The temple has a new entry hall (Go Khang), which has paintings dated to the late 19th century or 20th century. The old entry hall, which originally formed the only part of the complex, has retained the paintings of 996 AD.[17]

The Vajradhatu mandala is seen in the New Assembly Hall after entering from the old entry hall where the main deity of Vajradhatu, Vairocana (height 110 cm), is shown seated on a single lotus throne on the back wall. The main iconographic deities here are the Vajradhatu and life-size clay sculptures with painted decorations complementing the main theme. The mandala also has 32 life-size clay sculptures of other deities which are embedded to the wall which merge well within the painted environment. The Protector Deity, Dorje Chenmo, originally known as Wi-nyu-nin, of the main temple was venerated in this hall. The paintings are of very good quality with bright colours, and are dated to 15th or early 16th century. An inscription which brings out the details of renovation works done is fixed to the right of Vajrapasa image.[17] The paintings are depicted in three sections with the central panel of the throne scene. The royal lama, Jangchub 'Od, who was in charge of the renovation, is painted here. On the left part of the composition 'the great Sangha of Tabo monastery' is depicted.

Three very large life-size sculptures are located on a raised platform. They are within the shrine area of the temple. Each is flanked by a pair of painted goddesses. A seated Buddha figure sitting on a throne with the base sculpted with two lions facing each other is also seen; this is a partially restored image. The circumambulation of the temple performed by the devotees in a clock-wise fashion passes through the assembly hall. During this process, the narrative imagery on the south and adjacent walls, the pilgrimage of Sudhana, and on the north and adjacent walls, the Life of the Buddha are seen.[17]

The main temple (Tsug la Khang) has the main hall and main assembly area. It also contains many scriptures written on wooden planks, which are hung on the walls. The dark main temple room is lit by a small sky window and hence the room appears dark. In the inner vestibule, there are colorful frescoes of Buddhist and Hindu-Buddhist gods. Next to the vestibule is the small room where garments for the ritual dances are kept. The main hall at the centre is studded with images, and at the centre is a Buddha image in the Lotus position. This image is flanked on either side by divine figures. On the pedestals next to the main image are many more brass images of Lamas. Tapestries cover the walls, doors and columns, and paintings of various Buddha incarnations, starting with Siddhartha and that of the Panchen Lamas, give it a divine atmosphere. About 50 clay images and full size busts of gods and demons are seen in the back wall of the main hall. The 108 holy scriptures are also part of the main hall display and weigh about 500 pounds.[18]

Older temples

[edit]

The Golden Temple (gSer-khang) is said to have been once covered with gold. It was renovated by Sengge Namgyal, a king of Ladakh in the 16th century. The walls and ceilings are covered with magnificent murals, which are well preserved and are dated to the 16th century. The other iconographic figures seen here are also found in other temples within the complex, and one such is of Vajradhara depiction.[1][17]

The Bodhisattva Maitreya Temple (Byams-Pa Chen-po Lha-khang) is an ancient temple built in the first 100 years of the main monastery as testified by the wooden door frame. Remnants of a painting is attributed to the 14th century. According to the sketch in the Mandala Temple it is indicated that the Maitreya Temple was initially double storied, which is also confirmed by the damage to the entrance wall. The image of the Bodhisattva Maitreya here is over six metres (20 feet) high. There are also murals showing Tashilhunpo Monastery in Shigatse and the Potala in Lhasa. A carved stone column base has the figure of a lion.[1][17]

In the Initiation Temple (dKyil-kHor- khang), there is a huge painting of Vairocana surrounded by eight Bodhisattvas. The other walls are covered in mandalas. This is where monks receive their initiations.

The Temple of Dromton or Trom-ton Temple (Brom-ston Lha khang) is thought to have been founded by Dromton (1008-1064 CE), one of the main disciples of Atisha.[1] The Large Trom-ton Temple has murals of the eight Medicine Buddhas, which are dated to the 17th century; at the base of this temple the life of Shakyamuni Buddha is painted in a narrative form.[17] The Small Mandala Temple is used for tantric rituals and teachings, may also be of the early period.[17] The interior of the Small Trom-ton Temple has very elegant paintings; however, remnants of carvings, dates attributed to the 13th or 14th century, are discerned at the entry door to the temple.[17] The Nun's Temple, a small temple, is seen on the back wall of the compound; the paintings here dated to 18th century are not of good quality.[17]

Newer temples

[edit]Five temples are included in the newer temple group,[1] such as the Chamber of Picture Treasures (Z'al-ma) and the White Temple. (dKar-abyum Lha-Khang). After the assembly hall, the large Temple of Dromton (Brom-ston Lha khang) is the largest temple in the complex and contains many wall paintings; the wooden planks in the ceiling are decorated. The Mahakala Vajra Bhairava Temple (Gon-khang) contains the protective deity of the Gelukpa sect; it contains fierce deities and is only entered after protective meditation. The Protectress deity of the monastery along with her retinue are depicted on a large panel on the east wall of the main entrance; this painting was damaged due to water seepage and has been very well restored by ASI as it provides a link to the old history of Tabo Monastery.[17]

Stupas

[edit]There are many stupas in the precincts of the temple complex of which four have paintings in its interior. Two of the stupas are dated to the 13th century, based on the paintings. A carved wooden lintel was also found in one of the stupas.[17]

Fittings

[edit]The monastery is known as "the Ajanta of the Himalayas" because of its frescoes and stucco paintings. The iconography of this period in the temples also supports the bond that existed between the two cultures of India and Tibet. There is a large and priceless collection of thankas (scroll paintings), manuscripts, well-preserved statues, frescos and extensive murals which cover almost every wall. While in the earlier period, paintings in the interior of the main Tabo temple and its stupas represented the Nyingmapa, Kadampa and Sakyapa traditions, the later period represent paintings of the Gelugpa tradition. In the independent small chambers of the monastery, there are many paintings on the walls. The frescoes seen inside the gompa are in a fragile state. Some are of a bright cobalt colour. Prior to the 1975 earthquake, there were 32 raised medallions on the walls of the temple hall, and an image placed in front of each of them.[19]

Grounds

[edit]The monastery has been built like a fort with very strong walls. The walls of these structures are 3 feet (0.91 m) in thickness and it is the reason for its survival over the centuries of depredations and natural calamities.[6] The high mud brick wall which encloses some 6,300 square metres (68,000 sq ft). In addition to the temples, chortens, and monks' residence, there is an extension that houses the nuns' residence.[9]

Activities

[edit]

Worship

[edit]Daily worship starts with chantings at 6 AM, performed by the lamas who live in the new temple complex. The lamas also perform tantric rites here in the temples.[1]

Education

[edit]Tabo evolved as an important centre of learning in its early centuries; the Kadampa School developed into the Gelugpa School. The monastery currently runs the Serkong School, which was established on 29 May 1999, marking the 15th birthday of Serkong Tsenshap Rinpoche, the present abbot. There are 274 students, from the age of 5 to 14 years, in classes 1–8. The subjects covered are English, Hindi and Spiti Bhoti languages, Social Science, Social Studies, Math and General Knowledge. Information technology, Sanskrit language and Art are also provided to students in higher grade levels. The Indian government funds about 50 per cent of the school through a grant; the rest of the expenses are met through student fees and donations. The monastery has plans to enlarge the school's infrastructure and facilities but needs funding.[13]

Festivals

[edit]Many festivals are held in the precincts of the monastery. The Tibetan monks perform traditional Buddhist and regional songs and dances.[13] The most popular religious festival held here is the Chakhar Festival, which is dedicated to the peace and happiness of all. This is held every three years, usually during September or October. On this occasion, religious masked dances, songs and general festivities are the main events.[13]

See also

[edit]- Rinchenling Gonpa at Halji in Limi valley, Nepal, also said to be founded by Lotsawa Rinchen Zangpo, and considered to have many similarities with the Tabo monastery.[20][21]

- Bhadrakalpikasutra c. 200-250 CE, which gives names of 1002 Buddhas

Bibliography

[edit]- Deshpande, Aruna (2005). India: A Divine Destination. Crest Publishing House. pp. 466–467. ISBN 81-242-0556-6.

- Handa, O. C. (1987). Buddhist Monasteries in Himachal Pradesh. Indus Publishing Company, New Delhi. ISBN 81-85182-03-5.

- Kapadia, Harish. (1999). Spiti: Adventures in the Trans-Himalaya. Second Edition. Indus Publishing Company, New Delhi. ISBN 81-7387-093-4.

- Rizvi, Janet. (1996). Ladakh: Crossroads of High Asia. Second Edition. Oxford University Press, Delhi. ISBN 0-19-564546-4.

- Cunningham, Alexander. (1854). LADĀK: Physical, Statistical, and Historical with Notices of the Surrounding Countries. London. Reprint: Sagar Publications (1977).

- Francke, A. H. (1977). A History of Ladakh. (Originally published as, A History of Western Tibet, (1907). 1977 Edition with critical introduction and annotations by S. S. Gergan & F. M. Hassnain. Sterling Publishers, New Delhi.

- Francke, A. H. (1914). Antiquities of Indian Tibet. Two Volumes. Calcutta. 1972 reprint: S. Chand, New Delhi.

- Klimburg-Salter, Deborah E. (2005). Tabo Monastery: Art and History. With an Interview of Geshe Sonam Wangdu by Peter Stefan and a Tibetan Summary. Deborah E. Klimburg-Salter. Vienna, Austria. This book is a donation to Tabo Monastery from the Austrian Science Fund. Not for sale.

- Singh, Sarina; et al. India. (2007). 12th Edition. Lonely Planet. ISBN 978-1-74104-308-2.

- Tucci, Giuseppe. (1988). Rin-chen-bzan-po and the Renaissance of Buddhism in Tibet Around the Millenium. First Italian Edition 1932. First draft English translation by Nancy Kipp Smith, under the direction of Thomas J. Pritzker. Edited by Lokesh Chandra. English version of Indo-Tibetica II. Aditya Rakashan, New Delhi. ISBN 81-85179-21-2.

- Singh, A. K.(1985). "Trans-Himalayan Wall Paintings".Agam Kala prakashan, Delhi

- Singh, A. K.(1992)."Antiquities of Western Himalayas". Sundeep Prakashan, Delhi. ISBN 81-85067-79-1

| Part of a series on |

| Tibetan Buddhism |

|---|

|

References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e f g "Taboe Ancient Monastery: Ajanta of the Himalayas". Tabo in Spiti Valley. Retrieved 20 January 2013.

- ^ a b c Deshpande 2005, p. 666.

- ^ Klimburg-Salter, Deborah E. (1997). Tabo: a lamp for the kingdom : early Indo Tibetan Buddhist art in the western Himalaya. Skira. p. 39. ISBN 9788881182091. Retrieved 20 January 2013.

- ^ a b "HP to promote temple tourism". Tribune News Service. 8 October 2000. Retrieved 20 January 2013.

- ^ "Heritage status sought for Tabo monastery". Tribune News Service. 15 September 2003. Retrieved 20 January 2013.

- ^ a b c d Kapadia (1999), p. 64.

- ^ a b c d About Tabo Monastery

- ^ Deshpande 2005, p. 666Rizvi (1996), pp. 59, 256.

- ^ a b Deshpande 2005, p. 667.

- ^ "Tabo Monastery". Official Website of Tabo Monastery. Retrieved 21 January 2013.

- ^ a b "The History Of Tabo Monastery". Official Website of Tabo Monastery. Retrieved 21 January 2013.

- ^ Handa (1987), p. 131.

- ^ a b c d e f "Tabo Monastery Activities". Official Website of Tabo Monastery. Retrieved 21 January 2013.

- ^ a b "Lahaul Spiti". Government of Himachal Pradesh. Archived from the original on 17 March 2009. Retrieved 22 January 2013.

- ^ "ASI replacing Tabo monastery's beam". Tribune. 9 September 2002. Retrieved 21 January 2013.

- ^ Klimburg-Salter, Deborah E.; Tropper, Kurt (2007). Text, Image and Song In Transdisciplinary Dialogue: PIATS 2003 : Tibetan Studies : Proceedings of the Tenth Seminar of the International Association for Tibetan Studies, Oxford, 2003. BRILL. p. 63. ISBN 978-90-04-15549-7. Retrieved 24 January 2013.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k "Temples And Holy Objects At Tabo Monastery". Official Website of Tabo Monastery. Retrieved 21 January 2013.

- ^ Kapadia (1999), pp. 64-66

- ^ Francke, August Hermann (1914). Antiquities of Indian Tibet (Public domain ed.). Asian Educational Services. pp. 82–. ISBN 978-81-206-0769-9. Retrieved 20 January 2013.

{{cite book}}: ISBN / Date incompatibility (help) - ^ Bubriski, Kevin; Pandey, Abhimanyu (2018). Kailash Yatra: a Long Walk to Mt Kailash through Humla. New Delhi: Penguin Random House. p. 90.

- ^ "Mimi Church and Mariette Wiebenga: A four-fold Vairocana in the Rinchen Zangpo tradition at Halji in Nepal". asianart.com. Retrieved 5 August 2022.