Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Group theory

View on Wikipedia| Algebraic structure → Group theory Group theory |

|---|

|

In abstract algebra, group theory studies the algebraic structures known as groups. The concept of a group is central to abstract algebra: other well-known algebraic structures, such as rings, fields, and vector spaces, can all be seen as groups endowed with additional operations and axioms. Groups recur throughout mathematics, and the methods of group theory have influenced many parts of algebra. Linear algebraic groups and Lie groups are two branches of group theory that have experienced advances and have become subject areas in their own right.

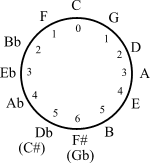

Various physical systems, such as crystals and the hydrogen atom, and three of the four known fundamental forces in the universe, may be modelled by symmetry groups. Thus group theory and the closely related representation theory have many important applications in physics, chemistry, and materials science. Group theory is also central to public key cryptography.

The early history of group theory dates from the 19th century. One of the most important mathematical achievements of the 20th century[1] was the collaborative effort, taking up more than 10,000 journal pages and mostly published between 1960 and 2004, that culminated in a complete classification of finite simple groups.

History

[edit]Group theory has three main historical sources: number theory, the theory of algebraic equations, and geometry. The number-theoretic strand was begun by Leonhard Euler, and developed by Gauss's work on modular arithmetic and additive and multiplicative groups related to quadratic fields. Early results about permutation groups were obtained by Lagrange, Ruffini, and Abel in their quest for general solutions of polynomial equations of high degree. Évariste Galois coined the term "group" and established a connection, now known as Galois theory, between the nascent theory of groups and field theory. In geometry, groups first became important in projective geometry and, later, non-Euclidean geometry. Felix Klein's Erlangen program proclaimed group theory to be the organizing principle of geometry.

Galois, in the 1830s, was the first to employ groups to determine the solvability of polynomial equations. Arthur Cayley and Augustin Louis Cauchy pushed these investigations further by creating the theory of permutation groups. The second historical source for groups stems from geometrical situations. In an attempt to come to grips with possible geometries (such as euclidean, hyperbolic or projective geometry) using group theory, Felix Klein initiated the Erlangen programme. Sophus Lie, in 1884, started using groups (now called Lie groups) attached to analytic problems. Thirdly, groups were, at first implicitly and later explicitly, used in algebraic number theory.

The different scope of these early sources resulted in different notions of groups. The theory of groups was unified starting around 1880. Since then, the impact of group theory has been ever growing, giving rise to the birth of abstract algebra in the early 20th century, representation theory, and many more influential spin-off domains. The classification of finite simple groups is a vast body of work from the mid 20th century, classifying all the finite simple groups.

Main classes of groups

[edit]The range of groups being considered has gradually expanded from finite permutation groups and special examples of matrix groups to abstract groups that may be specified through a presentation by generators and relations.

Permutation groups

[edit]The first class of groups to undergo a systematic study was permutation groups. Given any set X and a collection G of bijections of X into itself (known as permutations) that is closed under compositions and inverses, G is a group acting on X. If X consists of n elements and G consists of all permutations, G is the symmetric group Sn; in general, any permutation group G is a subgroup of the symmetric group of X. An early construction due to Cayley exhibited any group as a permutation group, acting on itself (X = G) by means of the left regular representation.

In many cases, the structure of a permutation group can be studied using the properties of its action on the corresponding set. For example, in this way one proves that for n ≥ 5, the alternating group An is simple, i.e. does not admit any proper normal subgroups. This fact plays a key role in the impossibility of solving a general algebraic equation of degree n ≥ 5 in radicals.

Matrix groups

[edit]The next important class of groups is given by matrix groups, or linear groups. Here G is a set consisting of invertible matrices of given order n over a field K that is closed under the products and inverses. Such a group acts on the n-dimensional vector space Kn by linear transformations. This action makes matrix groups conceptually similar to permutation groups, and the geometry of the action may be usefully exploited to establish properties of the group G.

Transformation groups

[edit]Permutation groups and matrix groups are special cases of transformation groups: groups that act on a certain space X preserving its inherent structure. In the case of permutation groups, X is a set; for matrix groups, X is a vector space. The concept of a transformation group is closely related with the concept of a symmetry group: transformation groups frequently consist of all transformations that preserve a certain structure.

The theory of transformation groups forms a bridge connecting group theory with differential geometry. A long line of research, originating with Lie and Klein, considers group actions on manifolds by homeomorphisms or diffeomorphisms. The groups themselves may be discrete or continuous.

Abstract groups

[edit]Most groups considered in the first stage of the development of group theory were "concrete", having been realized through numbers, permutations, or matrices. It was not until the late nineteenth century that the idea of an abstract group began to take hold, where "abstract" means that the nature of the elements are ignored in such a way that two isomorphic groups are considered as the same group. A typical way of specifying an abstract group is through a presentation by generators and relations,

A significant source of abstract groups is given by the construction of a factor group, or quotient group, G/H, of a group G by a normal subgroup H. Class groups of algebraic number fields were among the earliest examples of factor groups, of much interest in number theory. If a group G is a permutation group on a set X, the factor group G/H is no longer acting on X; but the idea of an abstract group permits one not to worry about this discrepancy.

The change of perspective from concrete to abstract groups makes it natural to consider properties of groups that are independent of a particular realization, or in modern language, invariant under isomorphism, as well as the classes of group with a given such property: finite groups, periodic groups, simple groups, solvable groups, and so on. Rather than exploring properties of an individual group, one seeks to establish results that apply to a whole class of groups. The new paradigm was of paramount importance for the development of mathematics: it foreshadowed the creation of abstract algebra in the works of Hilbert, Emil Artin, Emmy Noether, and mathematicians of their school.[citation needed]

Groups with additional structure

[edit]An important elaboration of the concept of a group occurs if G is endowed with additional structure, notably, of a topological space, differentiable manifold, or algebraic variety. If the multiplication and inversion of the group are compatible with this structure, that is, they are continuous, smooth or regular (in the sense of algebraic geometry) maps, then G is a topological group, a Lie group, or an algebraic group.[2]

The presence of extra structure relates these types of groups with other mathematical disciplines and means that more tools are available in their study. Topological groups form a natural domain for abstract harmonic analysis, whereas Lie groups (frequently realized as transformation groups) are the mainstays of differential geometry and unitary representation theory. Certain classification questions that cannot be solved in general can be approached and resolved for special subclasses of groups. Thus, compact connected Lie groups have been completely classified. There is a fruitful relation between infinite abstract groups and topological groups: whenever a group Γ can be realized as a lattice in a topological group G, the geometry and analysis pertaining to G yield important results about Γ. A comparatively recent trend in the theory of finite groups exploits their connections with compact topological groups (profinite groups): for example, a single p-adic analytic group G has a family of quotients which are finite p-groups of various orders, and properties of G translate into the properties of its finite quotients.

Branches of group theory

[edit]Finite group theory

[edit]During the twentieth century, mathematicians investigated some aspects of the theory of finite groups in great depth, especially the local theory of finite groups and the theory of solvable and nilpotent groups.[citation needed] As a consequence, the complete classification of finite simple groups was achieved, meaning that all those simple groups from which all finite groups can be built are now known.

During the second half of the twentieth century, mathematicians such as Chevalley and Steinberg also increased our understanding of finite analogs of classical groups, and other related groups. One such family of groups is the family of general linear groups over finite fields. Finite groups often occur when considering symmetry of mathematical or physical objects, when those objects admit just a finite number of structure-preserving transformations. The theory of Lie groups, which may be viewed as dealing with "continuous symmetry", is strongly influenced by the associated Weyl groups. These are finite groups generated by reflections which act on a finite-dimensional Euclidean space. The properties of finite groups can thus play a role in subjects such as theoretical physics and chemistry.

Representation of groups

[edit]Saying that a group G acts on a set X means that every element of G defines a bijective map on the set X in a way compatible with the group structure. When X has more structure, it is useful to restrict this notion further: a representation of G on a vector space V is a group homomorphism:

where GL(V) consists of the invertible linear transformations of V. In other words, to every group element g is assigned an automorphism ρ(g) such that ρ(g) ∘ ρ(h) = ρ(gh) for any h in G.

This definition can be understood in two directions, both of which give rise to whole new domains of mathematics.[3] On the one hand, it may yield new information about the group G: often, the group operation in G is abstractly given, but via ρ, it corresponds to the multiplication of matrices, which is very explicit.[4] On the other hand, given a well-understood group acting on a complicated object, this simplifies the study of the object in question. For example, if G is finite, it is known that V above decomposes into irreducible parts (see Maschke's theorem). These parts, in turn, are much more easily manageable than the whole V (via Schur's lemma).

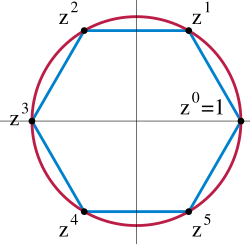

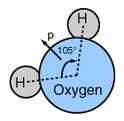

Given a group G, representation theory then asks what representations of G exist. There are several settings, and the employed methods and obtained results are rather different in every case: representation theory of finite groups and representations of Lie groups are two main subdomains of the theory. The totality of representations is governed by the group's characters. For example, Fourier polynomials can be interpreted as the characters of U(1), the group of complex numbers of absolute value 1, acting on the L2-space of periodic functions.

Lie theory

[edit]A Lie group is a group that is also a differentiable manifold, with the property that the group operations are compatible with the smooth structure. Lie groups are named after Sophus Lie, who laid the foundations of the theory of continuous transformation groups. The term groupes de Lie first appeared in French in 1893 in the thesis of Lie's student Arthur Tresse, page 3.[5]

Lie groups represent the best-developed theory of continuous symmetry of mathematical objects and structures, which makes them indispensable tools for many parts of contemporary mathematics, as well as for modern theoretical physics. They provide a natural framework for analysing the continuous symmetries of differential equations (differential Galois theory), in much the same way as permutation groups are used in Galois theory for analysing the discrete symmetries of algebraic equations. An extension of Galois theory to the case of continuous symmetry groups was one of Lie's principal motivations.

Combinatorial and geometric group theory

[edit]Groups can be described in different ways. Finite groups can be described by writing down the group table consisting of all possible multiplications g • h. A more compact way of defining a group is by generators and relations, also called the presentation of a group. Given any set F of generators , the free group generated by F surjects onto the group G. The kernel of this map is called the subgroup of relations, generated by some subset D. The presentation is usually denoted by For example, the group presentation describes a group which is isomorphic to A string consisting of generator symbols and their inverses is called a word.

Combinatorial group theory studies groups from the perspective of generators and relations.[6] It is particularly useful where finiteness assumptions are satisfied, for example finitely generated groups, or finitely presented groups (i.e. in addition the relations are finite). The area makes use of the connection of graphs via their fundamental groups. A fundamental theorem of this area is that every subgroup of a free group is free.

There are several natural questions arising from giving a group by its presentation. The word problem asks whether two words are effectively the same group element. By relating the problem to Turing machines, one can show that there is in general no algorithm solving this task. Another, generally harder, algorithmically insoluble problem is the group isomorphism problem, which asks whether two groups given by different presentations are actually isomorphic. For example, the group with presentation is isomorphic to the additive group Z of integers, although this may not be immediately apparent. (Writing , one has )

Geometric group theory attacks these problems from a geometric viewpoint, either by viewing groups as geometric objects, or by finding suitable geometric objects a group acts on.[7] The first idea is made precise by means of the Cayley graph, whose vertices correspond to group elements and edges correspond to right multiplication in the group. Given two elements, one constructs the word metric given by the length of the minimal path between the elements. A theorem of Milnor and Svarc then says that given a group G acting in a reasonable manner on a metric space X, for example a compact manifold, then G is quasi-isometric (i.e. looks similar from a distance) to the space X.

Connection of groups and symmetry

[edit]Given a structured object X of any sort, a symmetry is a mapping of the object onto itself which preserves the structure. This occurs in many cases, for example

- If X is a set with no additional structure, a symmetry is a bijective map from the set to itself, giving rise to permutation groups.

- If the object X is a set of points in the plane with its metric structure or any other metric space, a symmetry is a bijection of the set to itself which preserves the distance between each pair of points (an isometry). The corresponding group is called isometry group of X.

- If instead angles are preserved, one speaks of conformal maps. Conformal maps give rise to Kleinian groups, for example.

- Symmetries are not restricted to geometrical objects, but include algebraic objects as well. For instance, the equation has the two solutions and . In this case, the group that exchanges the two roots is the Galois group belonging to the equation. Every polynomial equation in one variable has a Galois group, that is a certain permutation group on its roots.

The axioms of a group formalize the essential aspects of symmetry. Symmetries form a group: they are closed because if you take a symmetry of an object, and then apply another symmetry, the result will still be a symmetry. The identity keeping the object fixed is always a symmetry of an object. Existence of inverses is guaranteed by undoing the symmetry and the associativity comes from the fact that symmetries are functions on a space, and composition of functions is associative.

Frucht's theorem says that every group is the symmetry group of some graph. So every abstract group is actually the symmetries of some explicit object.

The saying of "preserving the structure" of an object can be made precise by working in a category. Maps preserving the structure are then the morphisms, and the symmetry group is the automorphism group of the object in question.

Applications of group theory

[edit]Applications of group theory abound. Almost all structures in abstract algebra are special cases of groups. Rings, for example, can be viewed as abelian groups (corresponding to addition) together with a second operation (corresponding to multiplication). Therefore, group theoretic arguments underlie large parts of the theory of those entities.

Galois theory

[edit]Galois theory uses groups to describe the symmetries of the roots of a polynomial (or more precisely the automorphisms of the algebras generated by these roots). The fundamental theorem of Galois theory provides a link between algebraic field extensions and group theory. It gives an effective criterion for the solvability of polynomial equations in terms of the solvability of the corresponding Galois group. For example, S5, the symmetric group in 5 elements, is not solvable which implies that the general quintic equation cannot be solved by radicals in the way equations of lower degree can. The theory, being one of the historical roots of group theory, is still fruitfully applied to yield new results in areas such as class field theory.

Algebraic topology

[edit]Algebraic topology is another domain which prominently associates groups to the objects the theory is interested in. There, groups are used to describe certain invariants of topological spaces. They are called "invariants" because they are defined in such a way that they do not change if the space is subjected to some deformation. For example, the fundamental group "counts" how many paths in the space are essentially different. The Poincaré conjecture, proved in 2002/2003 by Grigori Perelman, is a prominent application of this idea. The influence is not unidirectional, though. For example, algebraic topology makes use of Eilenberg–MacLane spaces which are spaces with prescribed homotopy groups. Similarly algebraic K-theory relies in a way on classifying spaces of groups. Finally, the name of the torsion subgroup of an infinite group shows the legacy of topology in group theory.

Algebraic geometry

[edit]Algebraic geometry likewise uses group theory in many ways. Abelian varieties have been introduced above. The presence of the group operation yields additional information which makes these varieties particularly accessible. They also often serve as a test for new conjectures. (For example the Hodge conjecture (in certain cases).) The one-dimensional case, namely elliptic curves is studied in particular detail. They are both theoretically and practically intriguing.[8] In another direction, toric varieties are algebraic varieties acted on by a torus. Toroidal embeddings have recently led to advances in algebraic geometry, in particular resolution of singularities.[9]

Algebraic number theory

[edit]Algebraic number theory makes uses of groups for some important applications. For example, Euler's product formula,

captures the fact that any integer decomposes in a unique way into primes. The failure of this statement for more general rings gives rise to class groups and regular primes, which feature in Kummer's treatment of Fermat's Last Theorem.

Harmonic analysis

[edit]Analysis on Lie groups and certain other groups is called harmonic analysis. Haar measures, that is, integrals invariant under the translation in a Lie group, are used for pattern recognition and other image processing techniques.[10]

Combinatorics

[edit]In combinatorics, the notion of permutation group and the concept of group action are often used to simplify the counting of a set of objects; see in particular Burnside's lemma.

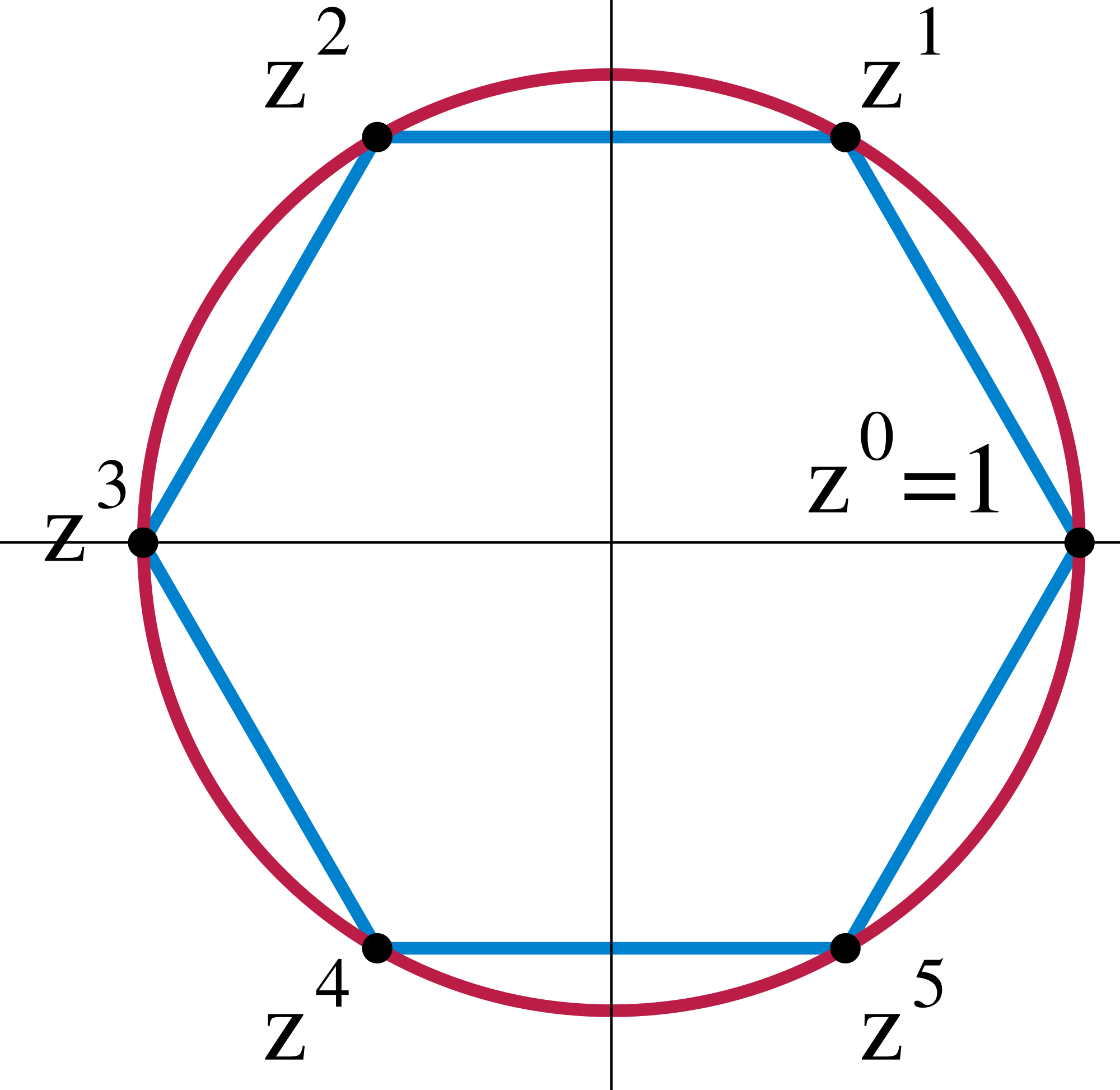

Music

[edit]The presence of the 12-periodicity in the circle of fifths yields applications of elementary group theory in musical set theory. Transformational theory models musical transformations as elements of a mathematical group.

Physics

[edit]In physics, groups are important because they describe the symmetries which the laws of physics seem to obey. According to Noether's theorem, every continuous symmetry of a physical system corresponds to a conservation law of the system. Physicists are very interested in group representations, especially of Lie groups, since these representations often point the way to the "possible" physical theories. Examples of the use of groups in physics include the Standard Model, gauge theory, the Lorentz group, and the Poincaré group.

Group theory can be used to resolve the incompleteness of the statistical interpretations of mechanics developed by Willard Gibbs, relating to the summing of an infinite number of probabilities to yield a meaningful solution.[11]

Chemistry and materials science

[edit]In chemistry and materials science, point groups are used to classify regular polyhedra, and the symmetries of molecules, and space groups to classify crystal structures. The assigned groups can then be used to determine physical properties (such as chemical polarity and chirality), spectroscopic properties (particularly useful for Raman spectroscopy, infrared spectroscopy, circular dichroism spectroscopy, magnetic circular dichroism spectroscopy, UV/Vis spectroscopy, and fluorescence spectroscopy), and to construct molecular orbitals.

Molecular symmetry is responsible for many physical and spectroscopic properties of compounds and provides relevant information about how chemical reactions occur. In order to assign a point group for any given molecule, it is necessary to find the set of symmetry operations present on it. The symmetry operation is an action, such as a rotation around an axis or a reflection through a mirror plane. In other words, it is an operation that moves the molecule such that it is indistinguishable from the original configuration. In group theory, the rotation axes and mirror planes are called "symmetry elements". These elements can be a point, line or plane with respect to which the symmetry operation is carried out. The symmetry operations of a molecule determine the specific point group for this molecule.

In chemistry, there are five important symmetry operations. They are identity operation (E), rotation operation or proper rotation (Cn), reflection operation (σ), inversion (i) and rotation reflection operation or improper rotation (Sn). The identity operation (E) consists of leaving the molecule as it is. This is equivalent to any number of full rotations around any axis. This is a symmetry of all molecules, whereas the symmetry group of a chiral molecule consists of only the identity operation. An identity operation is a characteristic of every molecule even if it has no symmetry. Rotation around an axis (Cn) consists of rotating the molecule around a specific axis by a specific angle. It is rotation through the angle 360°/n, where n is an integer, about a rotation axis. For example, if a water molecule rotates 180° around the axis that passes through the oxygen atom and between the hydrogen atoms, it is in the same configuration as it started. In this case, n = 2, since applying it twice produces the identity operation. In molecules with more than one rotation axis, the Cn axis having the largest value of n is the highest order rotation axis or principal axis. For example in boron trifluoride (BF3), the highest order of rotation axis is C3, so the principal axis of rotation is C3.

In the reflection operation (σ) many molecules have mirror planes, although they may not be obvious. The reflection operation exchanges left and right, as if each point had moved perpendicularly through the plane to a position exactly as far from the plane as when it started. When the plane is perpendicular to the principal axis of rotation, it is called σh (horizontal). Other planes, which contain the principal axis of rotation, are labeled vertical (σv) or dihedral (σd).

Inversion (i ) is a more complex operation. Each point moves through the center of the molecule to a position opposite the original position and as far from the central point as where it started. Many molecules that seem at first glance to have an inversion center do not; for example, methane and other tetrahedral molecules lack inversion symmetry. To see this, hold a methane model with two hydrogen atoms in the vertical plane on the right and two hydrogen atoms in the horizontal plane on the left. Inversion results in two hydrogen atoms in the horizontal plane on the right and two hydrogen atoms in the vertical plane on the left. Inversion is therefore not a symmetry operation of methane, because the orientation of the molecule following the inversion operation differs from the original orientation. And the last operation is improper rotation or rotation reflection operation (Sn) requires rotation of 360°/n, followed by reflection through a plane perpendicular to the axis of rotation.

Cryptography

[edit]

Very large groups of prime order constructed in elliptic curve cryptography serve for public-key cryptography. Cryptographical methods of this kind benefit from the flexibility of the geometric objects, hence their group structures, together with the complicated structure of these groups, which make the discrete logarithm very hard to calculate. One of the earliest encryption protocols, Caesar's cipher, may also be interpreted as a (very easy) group operation. Most cryptographic schemes use groups in some way. In particular Diffie–Hellman key exchange uses finite cyclic groups. So the term group-based cryptography refers mostly to cryptographic protocols that use infinite non-abelian groups such as a braid group.

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ Elwes, Richard (December 2006), "An enormous theorem: the classification of finite simple groups", Plus Magazine (41), archived from the original on 2009-02-02, retrieved 2011-12-20

- ^ This process of imposing extra structure has been formalized through the notion of a group object in a suitable category. Thus Lie groups are group objects in the category of differentiable manifolds and affine algebraic groups are group objects in the category of affine algebraic varieties.

- ^ Such as group cohomology or equivariant K-theory.

- ^ In particular, if the representation is faithful.

- ^ Arthur Tresse (1893), "Sur les invariants différentiels des groupes continus de transformations", Acta Mathematica, 18: 1–88, doi:10.1007/bf02418270

- ^ Schupp & Lyndon 2001

- ^ La Harpe 2000

- ^ See the Birch and Swinnerton-Dyer conjecture, one of the millennium problems

- ^ Abramovich, Dan; Karu, Kalle; Matsuki, Kenji; Wlodarczyk, Jaroslaw (2002), "Torification and factorization of birational maps", Journal of the American Mathematical Society, 15 (3): 531–572, arXiv:math/9904135, doi:10.1090/S0894-0347-02-00396-X, MR 1896232, S2CID 18211120

- ^ Lenz, Reiner (1990), Group theoretical methods in image processing, Lecture Notes in Computer Science, vol. 413, Berlin, New York: Springer-Verlag, doi:10.1007/3-540-52290-5, ISBN 978-0-387-52290-6, S2CID 2738874

- ^ Norbert Wiener, Cybernetics: Or Control and Communication in the Animal and the Machine, ISBN 978-0262730099, Ch 2

References

[edit]- Borel, Armand (1991), Linear algebraic groups, Graduate Texts in Mathematics, vol. 126 (2nd ed.), Berlin, New York: Springer-Verlag, doi:10.1007/978-1-4612-0941-6, ISBN 978-0-387-97370-8, MR 1102012

- Carter, Nathan C. (2009), Visual group theory, Classroom Resource Materials Series, Mathematical Association of America, ISBN 978-0-88385-757-1, MR 2504193

- Cannon, John J. (1969), "Computers in group theory: A survey", Communications of the ACM, 12: 3–12, doi:10.1145/362835.362837, MR 0290613, S2CID 18226463

- Frucht, R. (1939), "Herstellung von Graphen mit vorgegebener abstrakter Gruppe", Compositio Mathematica, 6: 239–50, ISSN 0010-437X, archived from the original on 2008-12-01

- Golubitsky, Martin; Stewart, Ian (2006), "Nonlinear dynamics of networks: the groupoid formalism", Bull. Amer. Math. Soc. (N.S.), 43 (3): 305–364, doi:10.1090/S0273-0979-06-01108-6, MR 2223010 Shows the advantage of generalising from group to groupoid.

- Judson, Thomas W. (1997), Abstract Algebra: Theory and Applications An introductory undergraduate text in the spirit of texts by Gallian or Herstein, covering groups, rings, integral domains, fields and Galois theory. Free downloadable PDF with open-source GFDL license.

- Kleiner, Israel (1986), "The evolution of group theory: a brief survey", Mathematics Magazine, 59 (4): 195–215, doi:10.2307/2690312, ISSN 0025-570X, JSTOR 2690312, MR 0863090

- La Harpe, Pierre de (2000), Topics in geometric group theory, University of Chicago Press, ISBN 978-0-226-31721-2

- Livio, M. (2005), The Equation That Couldn't Be Solved: How Mathematical Genius Discovered the Language of Symmetry, Simon & Schuster, ISBN 0-7432-5820-7 Conveys the practical value of group theory by explaining how it points to symmetries in physics and other sciences.

- Mumford, David (1970), Abelian varieties, Oxford University Press, ISBN 978-0-19-560528-0, OCLC 138290

- Ronan M., 2006. Symmetry and the Monster. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-280722-6. For lay readers. Describes the quest to find the basic building blocks for finite groups.

- Rotman, Joseph (1994), An introduction to the theory of groups, New York: Springer-Verlag, ISBN 0-387-94285-8 A standard contemporary reference.

- Schupp, Paul E.; Lyndon, Roger C. (2001), Combinatorial group theory, Berlin, New York: Springer-Verlag, ISBN 978-3-540-41158-1

- Scott, W. R. (1987) [1964], Group Theory, New York: Dover, ISBN 0-486-65377-3 Inexpensive and fairly readable, but somewhat dated in emphasis, style, and notation.

- Shatz, Stephen S. (1972), Profinite groups, arithmetic, and geometry, Princeton University Press, ISBN 978-0-691-08017-8, MR 0347778

- Weibel, Charles A. (1994), An introduction to homological algebra, Cambridge Studies in Advanced Mathematics, vol. 38, Cambridge University Press, ISBN 978-0-521-55987-4, MR 1269324, OCLC 36131259

External links

[edit]- History of the abstract group concept

- Burnside, William (1911), , in Chisholm, Hugh (ed.), Encyclopædia Britannica, vol. 12 (11th ed.), Cambridge University Press, pp. 626–636 This is a detailed exposition of contemporaneous understanding of Group Theory by an early researcher in the field.

Group theory

View on GrokipediaFundamentals

Definition and axioms

In mathematics, group theory formalizes the concept of symmetry by modeling collections of reversible transformations that preserve some underlying structure, such as rotations or reflections of geometric objects. These symmetries form a group under composition, providing a unified way to analyze patterns of invariance across diverse fields like geometry, physics, and algebra.[2] The abstract structure of a group abstracts away specific realizations to focus on the algebraic properties shared by all such symmetric operations.[8] A group is defined as a nonempty set together with a binary operation satisfying four fundamental axioms: closure, associativity, the existence of an identity element, and the existence of inverses.[1] This definition, introduced in the 19th century and refined over time, captures the essence of reversible operations while excluding structures that fail to maintain these properties.[9] The closure axiom requires that for all , the product is also an element of ; this ensures the operation produces results within the set, preventing "leakage" that would undermine repeated applications.[10] Without closure, the structure cannot consistently model transformations on the set. For instance, the natural numbers under subtraction fail closure, as lies outside the natural numbers, disqualifying it as a binary operation for a group.[11] Associativity states that for all , ; this property guarantees that the grouping of operations does not affect the outcome, enabling unambiguous computation of longer sequences without parentheses.[1] It is logically essential for defining powers and iterates, as non-associative operations like vector cross products would lead to inconsistencies in extended compositions. The identity axiom posits the existence of an element such that for every , ; this neutral element acts as a "do-nothing" transformation, serving as a reference point for all other operations.[12] In symmetric contexts, it corresponds to the trivial transformation that leaves everything unchanged. Finally, the invertibility axiom requires that for each , there exists an inverse satisfying ; this ensures every transformation can be undone, embodying the reversibility central to symmetry.[1] Structures lacking inverses, such as the natural numbers under addition (where no element inverts 1 to reach the identity 0), cannot qualify as groups.[13] Groups are denoted by the ordered pair , emphasizing both the set and its operation.[9] When the operation resembles multiplication, multiplicative notation is used (with written as ); for addition-like operations, additive notation prevails (with and inverses as negatives). Groups are classified as finite if the cardinality , or order, is a finite nonnegative integer, or infinite otherwise; the order quantifies the group's size and influences its possible subgroups and representations.[14]Basic examples and properties

The trivial group, often denoted as , consists solely of the identity element and forms the simplest example of a group under the operation where . This structure satisfies all group axioms, with serving as its own inverse.[15] A fundamental infinite example is the set of integers under addition, which forms an abelian group with identity element $0n \in \mathbb{Z}-nm + n = n + mm, n \in \mathbb{Z}, and the group is generated by $1 since every integer is a multiple of $1\mathbb{R} under [addition](/page/Addition), with identity $0 and inverse for each ; commutativity holds as for all .[16] Finite cyclic groups provide essential finite examples. A group is cyclic if there exists an element such that every element is a power of , i.e., . The integers modulo , denoted under addition modulo , form a cyclic group of order generated by $1, with identity $0 and inverse of given by . This group is abelian since .[17] The order of an element in a group , denoted , is the smallest positive integer such that , where is the identity; if no such exists, the order is infinite. In the trivial group, . In under addition, every nonzero element has infinite order, while in , the order of is .[18] Several basic properties follow directly from the group axioms. The identity element is unique: if and both satisfy and for all , then . To see this, substitute into the first to get , then multiply on the right by to obtain . Each element has a unique inverse: if and both satisfy and , then . This follows by left-multiplying by to get . Cancellation laws also hold: if , then (left cancellation), proved by right-multiplying both sides by ; similarly for right cancellation. These properties hold in any group, including the examples above.[19] Lagrange's theorem relates subgroup orders to the group order. For a finite group and subgroup , the order equals times the index , the number of distinct left cosets . Thus, divides . This result, originally from Lagrange's 1770 work on polynomial equations, is proved by noting that the left cosets of partition (since if , then , by the cancellation law), and each coset has exactly elements, so . For instance, in , the subgroup has order $1n, and the whole group has index $1.[20]Historical Development

Early origins and geometric roots

The roots of group theory lie in ancient geometric intuitions, particularly in Euclidean geometry around 300 BCE. Euclid's Elements explored congruences of plane figures, which implicitly relied on symmetries such as rotations and reflections that preserve distances, angles, and overall shape. These operations formed the basis for understanding isometries in the plane, allowing proofs of figure equivalence without explicit algebraic formalization.[21] In the 18th century, Leonhard Euler advanced these geometric ideas through studies of polyhedral symmetries. Euler investigated the rotational symmetries of regular polyhedra like the icosahedron and dodecahedron, discovering that the group of rotations for each has 60 elements, an early enumeration of symmetry operations without modern group terminology. Euler's 1779 work on Latin squares, prompted by the "36 officers problem," examined orthogonal arrangements of symbols that encode multiple permutations simultaneously, serving as prototypes for the combinatorial structure of permutation sets.[21] Joseph-Louis Lagrange's reflections in the 1770s further bridged geometry and algebra via permutations. In his 1771 paper Réflexions sur la résolution algébrique des équations, Lagrange analyzed permutations of polynomial roots to simplify resolvent equations, noting how cycles and orders of these permutations influence solvability, which foreshadowed key results like the theorem bearing his name on subgroup indices.[21][3] Early explorations of solvability by radicals involved figures like Jean le Rond d'Alembert and Paolo Ruffini. D'Alembert's 1746 memoir on equation roots emphasized distinctions between real and imaginary solutions, contributing to criteria for radical expressions in lower-degree polynomials. Ruffini, in his 1799 treatise Teoria generale delle equazioni, employed permutation analysis to argue that general quintic equations resist solution by radicals, marking a pivotal intuitive step toward structural obstructions in algebra.[3][21] Évariste Galois's nascent ideas in the late 1820s and early 1830s built on these foundations by focusing on permutations of roots. In his 1830 bulletin note and subsequent memoir, Galois considered substitutable permutations that preserve algebraic relations among roots, introducing rudimentary notions of permutation groups to classify solvability conditions without fully abstracting the group concept. Galois also coined the term "group" (groupe) around this time for sets of permutations.[21]19th-century formalization

In the early 1830s, Évariste Galois pioneered the use of groups as sets of permutations to analyze the solvability of polynomial equations by radicals, laying the groundwork for modern group theory. He conceptualized the Galois group associated with a polynomial, where the structure of this group determines whether the equation can be solved using radical expressions, and introduced the notion of normal subgroups as those invariant under conjugation, which are essential for constructing solvable series in groups. Galois's insights stemmed from his efforts to extend the work on quadratic, cubic, and quartic equations, revealing that the symmetry properties captured by these permutation groups dictate solvability conditions. Tragically, Galois died in 1832 at age 20 following a duel, leaving his ideas unpublished during his lifetime. Galois's manuscript was rescued and published posthumously in 1846 by Joseph Liouville in the Journal de Mathématiques Pures et Appliquées, where Liouville edited and appended his own commentary to clarify and promote the revolutionary ideas. This publication highlighted how Galois groups could classify polynomials based on their resolubility, building on the Abel-Ruffini theorem, which Niels Henrik Abel proved in 1824 and Paolo Ruffini had anticipated earlier, demonstrating that general quintic equations (degree 5) are not solvable by radicals. Galois's group-theoretic approach provided the precise mechanism: if the Galois group of a quintic is the symmetric group , which is not solvable, then no radical solution exists, thus formalizing the impossibility in terms of group structure rather than ad hoc analysis. Augustin-Louis Cauchy advanced the formalization in the 1840s by treating permutation groups as an independent subject. In works from 1815 and 1844–1845, Cauchy established foundational results, including what is now known as Cauchy's theorem: in a finite group whose order is divisible by a prime , there exists an element of order . These contributions shifted focus from specific algebraic problems to the intrinsic properties of permutation sets, proving results like the existence of subgroups and Lagrange's theorem in this context. Arthur Cayley further abstracted the concept in 1854 with two papers in the Philosophical Magazine, providing the first definition of a group as an abstract set with a binary operation satisfying closure, associativity, identity, and inverses—detaching it entirely from permutations. This axiomatic approach enabled broader applications beyond algebra, emphasizing groups as algebraic structures in their own right. Meanwhile, in 1872, Felix Klein's Erlangen program, presented in his inaugural address at the University of Erlangen, proposed a unified classification of geometries by the transitive transformation groups preserving their structures, such as Euclidean geometry under the group of rigid motions or projective geometry under projective transformations. Klein's framework demonstrated group theory's power in organizing geometric knowledge, influencing the field's expansion.20th-century expansions and modern contributions

In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, William Burnside and Ferdinand Georg Frobenius laid foundational work in the representation theory of finite groups, with Burnside developing key concepts in his 1897 treatise on groups of finite order, including early explorations of representations as linear transformations.[22] Frobenius advanced this further by introducing the theory of characters and blocks in the 1890s and 1900s, providing tools to decompose representations into irreducible components and analyze their modular behavior, which became essential for understanding finite group structures.[23] The 1920s and 1930s saw group theory integrate deeply into abstract algebra, driven by Emil Artin and Emmy Noether, who emphasized axiomatic approaches and non-commutative structures, unifying disparate algebraic concepts through ideals and modules in their collaborative works during this period. Concurrently, Richard Brauer pioneered modular representation theory in the 1930s, extending Frobenius's ideas to characteristic-p representations and developing Brauer characters to classify blocks modulo primes, which resolved key problems in finite group decompositions.[24] Post-World War II developments included Claude Chevalley's systematic treatment of Lie groups in his 1946 monograph, bridging algebraic and differential structures through Chevalley groups, which generalized finite groups of Lie type.[25] Henri Cartan contributed to the topological aspects of Lie groups during this era, influencing classifications via homogeneous spaces.[26] A landmark milestone was the 1963 Feit-Thompson theorem, proving that every finite group of odd order is solvable, which provided a crucial reduction in the ongoing classification of finite simple groups.[27] This effort culminated in 2004 with Michael Aschbacher and others completing the classification, identifying all 26 sporadic simple groups alongside Lie-type and alternating groups.[28] The 1970s and 1980s marked the discovery of the Monster group, the largest sporadic simple group with over 8 × 10^53 elements, constructed by Robert Griess in 1982 and embedding 20 other sporadics as subquotients.[29] Computational group theory emerged prominently with the GAP system, initiated in 1986 at Aachen, enabling algorithmic computations of group structures, presentations, and representations for practical research.[30] Post-2000 contributions have extended group theory to interdisciplinary applications, including quantum groups in quantum computing, where Drinfeld-Jimbo quantizations model braided categories for topological quantum field theories.[31] In string theory, finite group symmetries underpin orbifold compactifications and monstrous moonshine phenomena, linking sporadic groups to modular forms and black hole entropy calculations in recent models.[32] The 2020s have seen advances in algorithmic group solving, such as improved nilpotent quotient algorithms in systems like GAP, enhancing solvability for large finite groups.Examples and Classes of Groups

Permutation groups

Permutation groups arise as subgroups of the symmetric group on a finite set, providing concrete realizations of abstract group structures through bijections that rearrange elements. These groups are fundamental in group theory, as they model symmetries and transformations on discrete objects, and serve as a bridge to more general algebraic concepts./05%3A_Permutation_Groups/5.01%3A_Definitions_and_Notation) The symmetric group consists of all bijections from a set of elements to itself, equipped with the group operation of composition. It has order , reflecting the number of possible rearrangements of distinct objects.[33] The group is generated by the set of all transpositions, which are permutations that swap two elements and leave the rest fixed.[34] A key subgroup of is the alternating group , comprising all even permutations—those that can be expressed as a product of an even number of transpositions. The alternating group has index 2 in , so its order is , and it is a normal subgroup.[35] For , is simple, meaning it has no nontrivial normal subgroups, a property that underscores its importance in the classification of finite simple groups./04%3A_Families_of_Groups/4.04%3A_Alternating_Groups) Permutations in are often represented using cycle notation, which decomposes a permutation into disjoint cycles for clarity and computational efficiency. For instance, the permutation sending 1 to 2, 2 to 3, and 3 to 1 while fixing other elements is denoted ./05%3A_Permutation_Groups/5.01%3A_Definitions_and_Notation) In this notation, the length of a cycle determines its order under composition, and two permutations are conjugate in if and only if they have the same cycle type—that is, the same multiset of cycle lengths.[36] This classification partitions into conjugacy classes, each corresponding to a partition of .[37] Cayley's theorem establishes that every finite group of order is isomorphic to a subgroup of via the regular action, where elements of act as permutations on the set itself by left multiplication./09%3A_Isomorphisms/9.01%3A_Definition_and_Examples) This embedding highlights the universality of permutation groups, as it shows that studying symmetries of sets suffices to understand all finite groups. Concrete examples illustrate the diversity of permutation groups. The Rubik's cube group, generated by face rotations, is a subgroup of , where the 48 non-center facets are labeled and permuted, subject to parity and orientation constraints that prevent it from being the full symmetric group.[38] Permutation groups are often analyzed through their actions on sets, particularly transitive and primitive ones. A permutation group acts transitively on a set if there is only one orbit, meaning any element can be mapped to any other by some group element.[39] An action is primitive if it is transitive and admits no nontrivial blocks—subsets of the set that are permuted as units beyond singletons or the whole set—ensuring the action is "indecomposable" in a strong sense.[40] Primitive groups form a foundational class in the study of permutation representations, with their structure tightly constrained by theorems like the Jordan-Hölder factorization.[41]Matrix groups

Matrix groups form a significant class of groups in group theory, consisting of sets of invertible matrices under matrix multiplication that preserve specific structures on vector spaces. These groups arise naturally in linear algebra and provide concrete realizations of abstract group properties, often serving as examples of Lie groups when defined over the real or complex numbers.[42] The general linear group is defined as the group of all invertible matrices with entries in a field , where the group operation is matrix multiplication. A matrix belongs to if and only if its determinant is nonzero, ensuring invertibility. This group captures all linear automorphisms of an -dimensional vector space over .[43] The special linear group is the kernel of the determinant homomorphism from to the multiplicative group , consisting precisely of those matrices in with determinant equal to 1. It forms a normal subgroup of and is generated by elementary matrices for .[44] Classical matrix groups include the orthogonal group , which comprises real matrices satisfying , preserving the standard Euclidean inner product. The special orthogonal group is the subgroup of with determinant 1. Similarly, the unitary group consists of complex matrices such that , where is the conjugate transpose, preserving the Hermitian inner product. The special unitary group requires determinant 1. The symplectic group preserves a nondegenerate alternating bilinear form, represented by matrices over satisfying , where is the standard symplectic matrix.[45][46][47] Over the real or complex fields, these groups possess a Lie group structure, being closed subgroups of or that are smooth manifolds. For instance, is the Lie group of rotations in three-dimensional Euclidean space, diffeomorphic to the real projective space . An important example is the Heisenberg group, realized as the group of upper triangular matrices over with ones on the diagonal: This nilpotent group is non-abelian and serves as a model for the Heisenberg algebra in quantum mechanics.[48] When is a finite field with elements (a prime power), is a finite group of order , playing a key role in the study of finite groups and their representations.[49]Transformation and symmetry groups

Transformation groups in group theory capture symmetries by modeling sets of transformations that preserve specific structures, such as distances or angles in geometric spaces. These groups arise naturally when studying objects invariant under certain mappings, linking algebraic structure to geometric intuition.[50] Isometry groups consist of transformations that preserve distances, forming the foundation for rigid symmetries in Euclidean spaces. The Euclidean group is the group of all isometries of , generated by translations and orthogonal transformations, including rotations and reflections. It decomposes as a semidirect product , where acts on the translation vectors. The orientation-preserving subgroup, often denoted or , restricts to special orthogonal transformations .[51] The dihedral group exemplifies finite transformation groups acting on regular polygons. It comprises the symmetries of a regular -gon, consisting of rotations by multiples of around the center and reflections across axes through vertices or midpoints of opposite sides, yielding a group of order . Formally, is generated by a rotation of order and a reflection satisfying and .) Weyl groups extend reflection symmetries to higher-dimensional root systems associated with Lie algebras. For a root system in a Euclidean space , the Weyl group is the subgroup of the orthogonal group generated by reflections across hyperplanes perpendicular to roots in . These groups are finite Coxeter groups, acting faithfully on and preserving the root system, with applications in classifying semisimple Lie algebras. For example, the Weyl group of type is the symmetric group .[52] Conformal transformation groups preserve angles, generalizing isometries to mappings that maintain local shapes up to scaling. In the complex plane , the conformal group consists of Möbius transformations with , forming the projective linear group , which acts triply transitively on the Riemann sphere. These transformations include inversions and dilations, distinct from rigid motions by allowing non-uniform scaling.[53] Infinite transformation groups illustrate symmetries in periodic patterns. Frieze groups describe one-dimensional infinite symmetries along a strip, classified into seven types based on combinations of translations, rotations, reflections, and glide reflections. Wallpaper groups extend this to two-dimensional tilings, with exactly 17 distinct types arising from discrete subgroups of isometries in the plane that include translations in two independent directions. These classifications, due to Fedorov, underpin crystallographic applications.[54] A key tool for analyzing transformation groups is the orbit-stabilizer theorem, which relates group order to action dynamics. For a group acting on a set and , the orbit and stabilizer satisfy when is finite. This theorem quantifies how symmetries partition objects into equivalent classes under group actions./06%3A_Group_Actions/6.02%3A_Orbits_and_Stabilizers)Abstract and finite groups

Abstract groups are algebraic structures defined purely by their operation satisfying the group axioms, without reference to any underlying set or geometric interpretation. Two abstract groups are considered the same up to isomorphism if there exists a bijective homomorphism between them, partitioning all groups into isomorphism classes that capture their intrinsic structural properties.[6] A standard way to specify an abstract group is through a presentation, denoted , where is a set of generators and is a set of relations that the generators must satisfy; this defines the group as the quotient of the free group on by the normal closure of .[55] For finite groups, presentations are particularly useful for computational purposes and classification, as they provide a concise encoding of the group's multiplication table.[56] Finite groups, those with a finite number of elements, form a central focus of group theory due to their amenability to complete classification in many cases. A -group is a finite group whose order is a power of a prime , and such groups exhibit rich structure, including the property that their centers are nontrivial.[57] Every finite -group is nilpotent, meaning it possesses a central series where each factor is abelian, which implies it is also solvable—a weaker condition requiring a subnormal series with abelian factors.[58] Nilpotent groups are a subclass of solvable groups, "closer to abelian" in the sense that they have a central series with abelian factors, while solvable groups have a subnormal series with abelian factors. Both classes are closed under direct products.[59] These distinctions are crucial for understanding decompositions and extensions in finite group theory. The Sylow theorems provide foundational tools for analyzing the -subgroup structure of finite groups. The first Sylow theorem guarantees the existence of Sylow -subgroups, maximal -subgroups of order where is the highest power of dividing the group's order.[60] The second theorem states that all Sylow -subgroups are conjugate to each other, ensuring a uniform size and establishing conjugacy classes among them.[61] The third theorem specifies that the number of Sylow -subgroups satisfies and divides the index , where is a Sylow -subgroup; uniqueness occurs if and only if , making the subgroup normal.[62] Applications of these theorems abound in classification efforts, such as determining when a group has normal Sylow subgroups or solving for groups of small order by counting possibilities for .[63] Simple groups are finite groups with no nontrivial normal subgroups, serving as the building blocks for all finite groups via composition series and extensions. The classification of finite simple groups, a monumental achievement of the late 20th century fully completed in 2004, asserts that every non-abelian finite simple group is isomorphic to either an alternating group for , a group of Lie type such as projective special linear groups , or one of 26 sporadic groups like the Monster group.[64] Abelian simple groups are precisely the cyclic groups of prime order. This theorem enables the decomposition of arbitrary finite groups into products and extensions of these simples, revolutionizing finite group theory.[65] Illustrative examples of finite non-abelian groups include those of order 8, where up to isomorphism there are exactly two: the dihedral group of symmetries of the square and the quaternion group with relations .[66] The quaternion group is a non-abelian 2-group that is nilpotent but not abelian, featuring a cyclic center of order 2 and all proper subgroups normal.[67] These groups demonstrate early applications of Sylow theory, as their unique Sylow 2-subgroup coincides with the whole group. Burnside's problem, posed in 1902, inquired whether a finitely generated group in which every element has finite order (a periodic group) must be finite. The general version received a negative solution in 1964 via constructions of infinite finitely generated -groups by Golod, using graded algebras to produce groups of exponent that are infinite.[68] Further counterexamples, such as the Grigorchuk group—a 2-group of intermediate growth—highlighted infinite torsion groups with additional properties like amenability. These resolutions underscore the complexity of infinite abstract groups arising from finite generation constraints.Algebraic Structures in Groups

Subgroups, cosets, and normal subgroups

A subgroup of a group is a non-empty subset of that forms a group under the same binary operation as . To satisfy this, must be closed under the operation, contain the identity element of , and include the inverse of every element in .[69] These criteria ensure inherits the group structure while remaining a proper subset, such as the even integers forming a subgroup of the integers under addition.[70] Cosets provide a way to partition using subgroups. For a subgroup and element , the left coset is , and the right coset is .[71] The distinct left (or right) cosets of in are disjoint and cover , with the number of such cosets called the index .[72] In abelian groups, left and right cosets coincide, but they may differ otherwise. Lagrange's theorem states that if is finite and , then divides , and specifically .[73] This follows from the partition into cosets, each of size , as cosets are equicardinal bijections via left multiplication by .[74] Applications include determining possible subgroup orders and the fact that the order of any element divides , since the cyclic subgroup has order equal to the smallest positive integer such that .[75] A normal subgroup is one invariant under conjugation, meaning for all , or equivalently, left and right cosets coincide: .[76] Every subgroup of an abelian group is normal, and normal subgroups enable quotient group constructions.[77] Key examples include the center , which is normal as elements commute with all conjugates, and the derived subgroup , generated by commutators , which is normal and measures deviation from abelianness.[43][78] Cyclic subgroups are generated by a single element and arise naturally, with their orders dividing by Lagrange's theorem.[79] For instance, in the symmetric group , the subgroup has order 2, dividing .[80]Homomorphisms, isomorphisms, and group actions

A group homomorphism is a function between two groups and that preserves the group operation, satisfying for all .[81] The kernel of , defined as , where is the identity in , forms a normal subgroup of .[82] This normality arises because conjugation by elements of maps the kernel to itself, ensuring compatibility with the group structure.[83] An isomorphism is a bijective homomorphism, establishing a one-to-one correspondence between groups while preserving their algebraic structure; thus, isomorphic groups are essentially identical up to relabeling of elements.[84] An automorphism is an isomorphism from a group to itself, and the set of all automorphisms of , denoted , forms a group under composition.[85] For example, in the symmetric group , inner automorphisms induced by conjugation generate a subgroup isomorphic to itself.[86] The first isomorphism theorem states that for a homomorphism , the quotient group is isomorphic to the image , providing a way to identify factor groups with subgroups of the codomain.[87] This theorem underscores how homomorphisms reveal structural similarities between groups. A group action is a map satisfying for the identity and for all and , equivalently a homomorphism from to the symmetric group on .[88] An action is transitive if there is only one orbit, meaning for any , there exists with ; it is free if stabilizers are trivial, i.e., implies .[89][90] The orbit-stabilizer theorem relates these concepts: for a group action on , the size of the orbit of equals the index of the stabilizer in , i.e., .[91] The fundamental theorem of group actions asserts that the orbits partition and that the action induces a transitive action on each orbit.[92] Examples include the conjugation action of on itself, where , with orbits as conjugacy classes and stabilizers as centralizers.[93] The regular action of on itself by left multiplication, , is both free and transitive, embedding as a subgroup of the symmetric group on elements via the Cayley theorem.[94]Quotient groups and direct products

A quotient group, also known as a factor group, is constructed from a group and a normal subgroup of . The elements of the quotient group are the left (or equivalently right, since is normal) cosets of in , with the group operation defined by for . This operation is well-defined precisely because is normal in , ensuring that the product of cosets depends only on the coset representatives and not on the choice of representatives.[95] The first isomorphism theorem for groups states that if is a group homomorphism, then , where is the kernel of , which is a normal subgroup of . This theorem establishes a fundamental connection between homomorphisms and quotient groups, showing that the image of is isomorphic to the quotient of by its kernel. Homomorphisms thus provide a key mechanism for constructing and identifying quotient groups.[95] The direct product of two groups and , denoted , consists of ordered pairs with and , equipped with the componentwise operation . This forms a group whose order is the product of the orders of and (if finite), and is abelian if and only if both and are abelian./09:_Isomorphisms/9.02:_Direct_Products) An internal direct product describes a decomposition of a group as , where and are normal subgroups of such that (the trivial subgroup) and every element of can be uniquely expressed as a product of an element from and an element from . This internal construction is isomorphic to the external direct product when these conditions hold, providing a way to decompose groups into simpler components.[96] More generally, the semidirect product of groups and incorporates a homomorphism , twisting the direct product operation to . This construction yields non-abelian groups even when and are abelian, capturing asymmetric interactions between subgroups. A classic example is the dihedral group of order , which is isomorphic to , where acts on by inversion.[97] Representative examples illustrate these constructions. The direct product is the free abelian group of rank 2, generated by and , with every element uniquely for integers . Another example is the Klein four-group, isomorphic to , an abelian group of order 4 where every non-identity element has order 2.[98][99]Branches of Group Theory

Finite group theory

Finite group theory examines the algebraic structure of groups with finitely many elements, emphasizing their internal organization, decompositions, and computational methods. Central to this field is the classification of finite groups up to isomorphism, though a complete classification remains elusive except for specific classes like abelian groups. Key concepts include series that reveal solvability and nilpotency, as well as tools for analyzing extensions and permutation representations. These structures underpin applications in algebra, number theory, and computational mathematics, building on foundational results like the Sylow theorems for p-subgroups. A cornerstone result is the fundamental theorem of finite abelian groups, which states that every finite abelian group is isomorphic to a direct sum of cyclic groups of prime-power order. This decomposition, known as the primary decomposition, uniquely determines the group up to isomorphism when the orders of the cyclic components are specified in non-increasing order for each prime. The theorem provides a complete classification of finite abelian groups and is essential for understanding their subgroup lattices and homomorphisms. Originally proved using group-theoretic methods, it highlights the torsion nature of these groups.[100] Solvable groups form an important class of finite groups, characterized by the termination of the derived series at the trivial subgroup after finitely many steps. Equivalently, a finite group is solvable if it admits a composition series whose factor groups are all abelian. This property implies that the group can be built from abelian groups via successive extensions, connecting to solvability by radicals in Galois theory. Solvable groups include all nilpotent groups and abelian groups, and their derived length measures the "distance" from abelianness. Nilpotent groups represent a stricter subclass, defined for finite groups by the termination of the lower central series at the trivial subgroup. The lower central series begins with the group itself and iteratively takes commutator subgroups with the previous term, capturing higher-order commutativity obstructions. Finite nilpotent groups are direct products of their Sylow p-subgroups and possess Hall subgroups—subgroups of order coprime to p that normalize their Sylow complements. These properties make nilpotent groups "close" to abelian, with the nilpotency class bounding the series length. In p-group theory, finite groups of p-power order exhibit rich structure, including the Frattini subgroup, which is the intersection of all maximal subgroups and consists of non-generators—elements that can be omitted from any generating set without loss. The Frattini subgroup is nilpotent and characteristic, and quotienting by it yields an elementary abelian group. Chief series, minimal normal series with elementary abelian factors, further decompose p-groups, revealing their chief factors as vector spaces over the field with p elements. These tools aid in classifying p-groups of small order.[101] Group extensions involve short exact sequences, where the transfer homomorphism maps from the extension group to the abelianization of the kernel, capturing index-related information. In cohomology terms, inflation and restriction functors relate the cohomology of the extension to those of the base and kernel groups, facilitating computations in group extensions. These maps are crucial for studying Schur multipliers and projective representations, though focused here on algebraic aspects.[102] Computational finite group theory relies on algorithms like the Schreier-Sims algorithm, developed in the 1970s, which constructs a base and strong generating set (BSGS) for a permutation group given by generators. Using Schreier's lemma on coset decompositions and Sims' sifting procedure, it computes the group order and tests membership efficiently, with time complexity polynomial in the degree for fixed base size. This algorithm forms the basis for software like GAP and MAGMA, enabling practical computations for groups up to degree thousands.[103]Representation theory

In representation theory, a central tool for studying finite groups is the realization of abstract group elements as linear transformations on vector spaces. A representation of a finite group over a field (typically ) is a group homomorphism , where is a finite-dimensional vector space over , and denotes the general linear group of invertible linear transformations on .[104] The dimension is called the degree of the representation. Two representations and are equivalent if there exists an invertible linear map such that for all , meaning they are conjugate in the sense of similar matrix representations after choosing bases.[104] Matrix groups, such as the special linear group , provide concrete examples of such representations acting on .[104] A key invariant of a representation is its character, defined by , the trace of the linear transformation .[105] Characters are class functions, constant on conjugacy classes of , and the character of a direct sum of representations is the sum of the individual characters.[104] For irreducible representations (those with no nontrivial invariant subspaces), the characters satisfy orthogonality relations: if and are characters of distinct irreducible representations over , then , where is the Kronecker delta.[105] These relations, first established by Frobenius, allow the decomposition of any representation into irreducibles via inner products of characters: the multiplicity of an irreducible in is .[105] Maschke's theorem guarantees that representations of finite groups over fields of characteristic not dividing (such as ) are semisimple, meaning every representation decomposes as a direct sum of irreducible representations.[106] This semisimplification arises from the existence of complementary projections for invariant subspaces, relying on averaging over the group action.[106] Consequently, the group algebra , which acts on itself via left multiplication to yield the regular representation, is semisimple. By the Artin-Wedderburn theorem, as algebras, where each is the degree of an irreducible representation, and the sum is over the distinct irreducibles (with multiplicity equal to the number of irreducibles of that degree).[104] To construct new representations from subgroups, the induced representation of a representation of a subgroup is defined on the space of functions satisfying for , with action .[104] Frobenius reciprocity relates induction and restriction: for representations of and of , the inner product , where inner products are taken with respect to characters.[104] This adjunction, originating in Frobenius's work on character composition, facilitates computing dimensions and decompositions by reducing to smaller subgroups.[104] A fundamental example is the regular representation of on , with character if and 0 otherwise.[104] By character orthogonality and Maschke's theorem, it decomposes as , where the sum is over all irreducible representations (up to equivalence), each appearing with multiplicity equal to its degree.[104] This decomposition underscores that the number of irreducible representations equals the number of conjugacy classes, and the sum of the squares of their degrees is .[104]Lie groups and Lie theory

A Lie group is a mathematical structure that combines the algebraic properties of a group with the geometric properties of a smooth manifold, where the group operations of multiplication and inversion are smooth maps. This concept was introduced by Sophus Lie in his work on continuous transformation groups, motivated by the study of symmetries in differential equations.[107] Formally, a Lie group is a smooth manifold equipped with a group structure such that the multiplication map and the inversion map are smooth. Many classical groups, such as matrix groups, provide concrete realizations of Lie groups.[107] Associated to every Lie group is its Lie algebra , which is the tangent space at the identity element , endowed with a Lie bracket derived from the adjoint action or the commutator of left-invariant vector fields. The term "Lie algebra" was coined by Hermann Weyl in the 1930s to describe this infinitesimal structure capturing the local behavior of the group.[108] The Lie bracket satisfies bilinearity, antisymmetry, and the Jacobi identity: This algebraic structure linearizes the nonlinear group, facilitating analysis of representations and symmetries.[108] The exponential map connects the Lie algebra to the group by sending an element to the endpoint of the unique one-parameter subgroup at , defined via the integral curves of left-invariant vector fields. For matrix Lie groups, this coincides with the matrix exponential . Locally, the group structure near the identity is governed by the Baker-Campbell-Hausdorff (BCH) formula, which expresses the logarithm of a product of exponentials as a series in nested commutators: . This formula, originally developed by Campbell, Baker, and Hausdorff in the early 1900s, allows reconstruction of the group multiplication from the algebra.[109][110] Finite-dimensional simple Lie algebras over the complex numbers were classified by Wilhelm Killing in 1888 and rigorously completed by Élie Cartan in 1894, yielding four infinite families and three exceptional cases. The classical series are (type ), (type ), (type ), and (type ), with exceptional algebras , , , , and . This classification relies on root systems, which are finite sets of vectors in a Euclidean space satisfying geometric axioms, reflecting the structure of semisimple algebras via Cartan subalgebras and their root decompositions. Eugene Dynkin in 1947 introduced Dynkin diagrams as graphical representations of these root systems, where nodes correspond to simple roots and edges encode their angles, providing a combinatorial tool for distinguishing the types.[111][112] Compact Lie groups are closed subgroups of the general linear group and admit a unique maximal torus , an abelian subgroup that is a maximal connected solvable subroup, up to conjugation. Hermann Weyl in 1925 showed that every element of a compact connected Lie group lies in some conjugate of , and the Weyl group (where is the normalizer of ) acts as a finite reflection group on the Lie algebra of , facilitating the study of representations via highest weights.[108] Prominent examples include the special orthogonal group , the connected component of the orthogonal group preserving the standard inner product on , which models rotations in Euclidean space. The special unitary group consists of unitary matrices with determinant 1, preserving the Hermitian inner product on . The Lorentz group is the orthogonal group for the Minkowski metric on , underlying spacetime symmetries in special relativity, with its connected component being the proper orthochronous Lorentz group.[113][113][114]Geometric and combinatorial group theory

Geometric group theory studies groups through their actions on geometric spaces, particularly via Cayley graphs, which provide a combinatorial model for the group's structure. The Cayley graph of a group with respect to a finite generating set (not containing the identity) is a graph with vertex set and edges connecting to for each and ; the distance between two vertices in this graph corresponds to the minimal word length of the corresponding group elements in the generators .[115] Introduced by Arthur Cayley in 1878, these graphs encode the geometry of the group, where quasi-isometries between Cayley graphs preserve essential large-scale features of the group.[116] Free groups on generators, which admit no nontrivial relations beyond those implied by inverses, serve as fundamental examples; their Cayley graphs with respect to the standard generators are trees, reflecting the absence of cycles.[117] The Nielsen-Schreier theorem asserts that every subgroup of a free group is itself free, with the rank determined by an index formula, providing a key tool for understanding subgroup structures in geometric contexts.[118] A central class in geometric group theory is that of hyperbolic groups, defined by Mikhail Gromov in 1987 as finitely generated groups whose Cayley graphs are -hyperbolic metric spaces for some , meaning geodesic triangles are -thin: each side lies within of the union of the other two.[119] This thinness condition captures a negative curvature-like behavior at large scales, ensuring efficient algorithms for problems like the word problem, which asks whether a given word in the generators represents the identity. Max Dehn solved the word problem in the 1910s for fundamental groups of closed orientable surfaces of genus at least 2, using Dehn's algorithm based on geodesic representatives and canonical reductions in the hyperbolic plane.[120] Hyperbolic groups generalize this solvability, as their Cayley graphs admit Morse geodesics with linear isoperimetric inequalities.[119] Combinatorial aspects emphasize word and growth properties; the growth rate of a group measures the asymptotic density of the number of elements within balls of radius in the Cayley graph, distinguishing polynomial growth (e.g., virtually nilpotent groups) from exponential growth (e.g., free groups). Small cancellation theory, developed in the mid-20th century, provides conditions on relators in group presentations to ensure asphericity and hyperbolicity; for instance, the condition implies the Cayley complex is hyperbolic, yielding solutions to the word problem via van Kampen diagrams with minimal overlaps. Examples abound in manifold topology: fundamental groups of closed hyperbolic 3-manifolds are hyperbolic by definition, inheriting geometric rigidity from Thurston's geometrization.[121] Braid groups , generated by Artin's generators with quadratic relations, arise combinatorially from weaving strands and act on configuration spaces, exhibiting exponential growth and connections to knot theory via closures.[122]Groups and Symmetry

Symmetry groups in geometry