Recent from talks

Contribute something

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Addiction

View on Wikipedia

| Addiction | |

|---|---|

| |

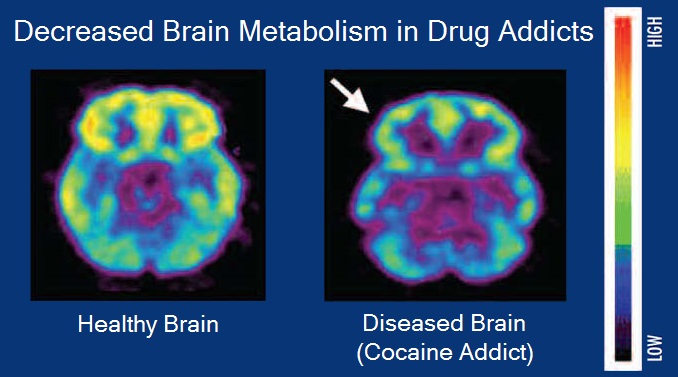

| Brain positron emission tomography images that compare brain metabolism in a healthy individual and an individual with a cocaine addiction | |

| Specialty | Psychiatry, clinical psychology, toxicology, addiction medicine |

| Symptoms | Recurring compulsion to engage in rewarding activity despite negative consequences |

| Risk factors | Family history, adverse childhood experiences, attention deficit hyperactivity disorder |

| Treatment | Cognitive behavioral therapy, behavior modification, medication |

Addiction is a neuropsychological disorder characterized by a persistent and intense urge to use a drug or engage in a behavior that produces natural reward, despite substantial harm and other negative consequences. Repetitive drug use can alter brain function in synapses similar to natural rewards like food or falling in love[1] in ways that perpetuate craving and weakens self-control for people with pre-existing vulnerabilities.[2] This phenomenon – drugs reshaping brain function – has led to an understanding of addiction as a brain disorder with a complex variety of psychosocial as well as neurobiological factors that are implicated in the development of addiction.[3][4][5] While mice given cocaine showed the compulsive and involuntary nature of addiction,[a] for humans this is more complex, related to behavior[6] or personality traits.[7]

Classic signs of addiction include compulsive engagement in rewarding stimuli, preoccupation with substances or behavior, and continued use despite negative consequences. Habits and patterns associated with addiction are typically characterized by immediate gratification (short-term reward),[8][9] coupled with delayed deleterious effects (long-term costs).[4][10]

Examples of substance addiction include alcoholism, cannabis addiction, amphetamine addiction, cocaine addiction, nicotine addiction, opioid addiction, and eating or food addiction. Behavioral addictions may include gambling addiction, shopping addiction, stalking, pornography addiction, internet addiction, social media addiction, video game addiction, and sexual addiction. The DSM-5 and ICD-10 only recognize gambling addictions as behavioral addictions, but the ICD-11 also recognizes gaming addictions.[11]

Signs and symptoms

[edit]Signs and symptoms of drug addiction can vary depending on the type of addiction. Symptoms may include:

- Continuation of drug use despite the knowledge of consequences[12]

- Disregarding financial status when it comes to drug purchases

- Ensuring a stable supply of the drug

- Needing more of the drug over time to achieve similar effects[12]

- Social and work life impacted due to drug use[12]

- Unsuccessful attempts to stop drug use[12]

- Urge to use drug regularly

Other signs and symptoms can be categorized across relevant dimensions:

| Behavioral Changes | Physical Changes | Social Changes |

|---|---|---|

|

|

|

Substance use disorder

[edit]| Addiction and dependence glossary[3][14][15] | |

|---|---|

| |

The DSM-5 discourages using the term "drug addiction" because of its "uncertain definition and its potentially negative connotation" and prefers the term "substance use disorder" to describe the wide range of the disorder, from a mild form to a severe state of chronically relapsing, compulsive pattern of drug taking.[16]

SUD, belongs to the class of substance-related disorders, is a chronic and relapsing brain disorder that features drug seeking and drug abuse, despite their harmful effects.[17] This form of addiction changes brain circuitry such that the brain's reward system is compromised,[18] causing functional consequences for stress management and self-control.[17] Damage to the functions of the organs involved can persist throughout a lifetime and cause death if untreated.[17] Substances involved with drug addiction include alcohol, nicotine, marijuana, opioids, cocaine, amphetamines, and even foods with high fat and sugar content.[19] Addictions can begin experimentally in social contexts[20] and can arise from the use of prescribed medications or a variety of other measures.[21]

It has been shown to work in phenomenological, conditioning (operant and classical), cognitive models, and the cue reactivity model. However, no one model completely illustrates substance abuse.[22]

Risk factors for addiction include:

- Aggressive behavior (particularly in childhood)

- Availability of substance[20]

- Community economic status[citation needed]

- Experimentation[20]

- Epigenetics

- Impulsivity (attentional, motor, or non-planning)[23]

- Lack of parental supervision[20]

- Lack of peer refusal skills[20]

- Mental disorders[20]

- Method substance is taken[17]

- Usage of substance in youth[20]

Food addiction

[edit]The diagnostic criteria for food or eating addiction has not been categorized or defined in references such as the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM or DSM-5) and is based on subjective experiences similar to substance use disorders.[12][23] Food addiction may be found in those with eating disorders, though not all people with eating disorders have food addiction and not all of those with food addiction have a diagnosed eating disorder.[12] Long-term frequent and excessive consumption of foods high in fat, salt, or sugar, such as chocolate, can produce an addiction[24][25] similar to drugs since they trigger the brain's reward system, such that the individual may desire the same foods to an increasing degree over time.[26][12][23] The signals sent when consuming highly palatable foods have the ability to counteract the body's signals for fullness and persistent cravings will result.[26] Those who show signs of food addiction may develop food tolerances, in which they eat more, despite the food becoming less satisfactory.[26]

Chocolate's sweet flavor and pharmacological ingredients are known to create a strong craving or feel 'addictive' by the consumer.[27] A person who has a strong liking for chocolate may refer to themselves as a chocoholic.

Risk factors for developing food addiction include excessive overeating and impulsivity.[23]

The Yale Food Addiction Scale (YFAS), version 2.0, is the current standard measure for assessing whether an individual exhibits signs and symptoms of food addiction.[28][12][23] It was developed in 2009 at Yale University on the hypothesis that foods high in fat, sugar, and salt have addictive-like effects which contribute to problematic eating habits.[29][26] The YFAS is designed to address 11 substance-related and addictive disorders (SRADs) using a 25-item self-report questionnaire, based on the diagnostic criteria for SRADs as per DSM-5.[30][12] A potential food addiction diagnosis is predicted by the presence of at least two out of 11 SRADs and a significant impairment to daily activities.[31]

The Barratt Impulsiveness Scale, specifically the BIS-11 scale, and the UPPS-P Impulsive Behavior subscales of Negative Urgency and Lack of Perseverance have been shown to have relation to food addiction.[23]

Behavioral addiction

[edit]The term behavioral addiction refers to a compulsion to engage in a natural reward – which is a behavior that is inherently rewarding (i.e., desirable or appealing) – despite adverse consequences.[9][24][25] Preclinical evidence has demonstrated that marked increases in the expression of ΔFosB through repetitive and excessive exposure to a natural reward induces the same behavioral effects and neuroplasticity as occurs in a drug addiction.[24][32][33][34]

Addiction can exist without psychotropic drugs, an idea that was popularized by psychologist Stanton Peele.[35] These are termed behavioral addictions. Such addictions may be passive or active, but they commonly contain reinforcing features, which are found in most addictions.[35] Sexual behavior, eating, gambling, playing video games, and shopping are all associated with compulsive behaviors in humans and have been shown to activate the mesolimbic pathway and other parts of the reward system.[24] Based on this evidence, sexual addiction, gambling addiction, video game addiction, and shopping addiction are classified accordingly.[24]

Causes

[edit]Personality theories

[edit]Personality theories of addiction are psychological models that associate personality traits or modes of thinking (i.e., affective states) with an individual's proclivity for developing an addiction. Data analysis demonstrates that psychological profiles of drug users and non-users have significant differences and the psychological predisposition to using different drugs may be different.[36] Models of addiction risk that have been proposed in psychology literature include: an affect dysregulation model of positive and negative psychological affects, the reinforcement sensitivity theory of impulsiveness and behavioral inhibition, and an impulsivity model of reward sensitization and impulsiveness.[37][38][39][40][41]

Neuropsychology

[edit]The transtheoretical model of change (TTM) can point to how someone may be conceptualizing their addiction and the thoughts around it, including not being aware of their addiction.[42]

Cognitive control and stimulus control, which is associated with operant and classical conditioning, represent opposite processes (i.e., internal vs external or environmental, respectively) that compete over the control of an individual's elicited behaviors.[43] Cognitive control, and particularly inhibitory control over behavior, is impaired in both addiction and attention deficit hyperactivity disorder.[44][45] Stimulus-driven behavioral responses (i.e., stimulus control) that are associated with a particular rewarding stimulus tend to dominate one's behavior in an addiction.[45]

| Operant conditioning | Extinction | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Reinforcement Increase behavior | Punishment Decrease behavior | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Positive reinforcement Add appetitive stimulus following correct behavior | Negative reinforcement | Positive punishment Add noxious stimulus following behavior | Negative punishment Remove appetitive stimulus following behavior | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Escape Remove noxious stimulus following correct behavior | Active avoidance Behavior avoids noxious stimulus | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Stimulus control of behavior

[edit]In operant conditioning, behavior is influenced by outside stimulus, such as a drug. The operant conditioning theory of learning is useful in understanding why the mood-altering or stimulating consequences of drug use can reinforce continued use (an example of positive reinforcement) and why the addicted person seeks to avoid withdrawal through continued use (an example of negative reinforcement). Stimulus control is using the absence of the stimulus or presence of a reward to influence the resulting behavior.[42]

Cognitive control of behavior

[edit]Cognitive control is the intentional selection of thoughts, behaviors, and emotions, based on our environment. It has been shown that drugs alter the way our brains function, and its structure.[46][18] Cognitive functions such as learning, memory, and impulse control, are affected by drugs.[46] These effects promote drug use, as well as hinder the ability to abstain from it.[46] The increase in dopamine release is prominent in drug use, specifically in the ventral striatum and the nucleus accumbens.[46] Dopamine is responsible for producing pleasurable feelings, as well driving us to perform important life activities. Addictive drugs cause a significant increase in this reward system, causing a large increase in dopamine signaling as well as increase in reward-seeking behavior, in turn motivating drug use.[46][18] This promotes the development of a maladaptive drug to stimulus relationship.[47] Early drug use leads to these maladaptive associations, later affecting cognitive processes used for coping, which are needed to successfully abstain from them.[46][42]

Evolutionary perspectives

[edit]Some scholars have proposed evolutionary explanations for addiction, suggesting that vulnerabilities to substance or behavioural dependence reflect by-products or dysregulated expressions of reward and learning systems that were adaptive in ancestral environments. Classic accounts argue that purified drugs and rapid delivery methods exploit ancient motivational circuitry by providing "false fitness signals" that mimic cues once linked to survival or reproduction.[48] Other reviews emphasise how psychoactive substances and behavioural reinforcers act on conserved mechanisms for reward, reinforcement, and emotion, which in modern settings can be overstimulated or maladapted.[49][50] These perspectives do not replace proximate neurobiological models, but aim instead to situate contemporary patterns of vulnerability within a broader evolutionary framework.[51][52]

Risk factors

[edit]A number of genetic and environmental risk factors exist for developing an addiction.[3][53] Genetic and environmental risk factors each account for roughly half of an individual's risk for developing an addiction;[3] the contribution from epigenetic risk factors to the total risk is unknown.[53] Even in individuals with a relatively low genetic risk, exposure to sufficiently high doses of an addictive drug for a long period of time (e.g., weeks–months) can result in an addiction.[3] Adverse childhood events are associated with negative health outcomes, such as substance use disorder. Childhood abuse or exposure to violent crime is related to developing a mood or anxiety disorder, as well as a substance dependence risk.[54]

Genetic factors

[edit]Genetic factors, along with socio-environmental (e.g., psychosocial) factors, have been established as significant contributors to addiction vulnerability.[3][53][55][12] Studies done on 350 hospitalized drug-dependent patients showed that over half met the criteria for alcohol abuse, with a role of familial factors being prevalent.[56] Genetic factors account for 40–60% of the risk factors for alcoholism.[57] Similar rates of heritability for other types of drug addiction have been indicated, specifically in genes that encode the Alpha5 Nicotinic Acetylcholine Receptor.[58] Knestler hypothesized in 1964 that a gene or group of genes might contribute to predisposition to addiction in several ways. For example, altered levels of a normal protein due to environmental factors may change the structure or functioning of specific brain neurons during development. These altered brain neurons could affect the susceptibility of an individual to an initial drug use experience. In support of this hypothesis, animal studies have shown that environmental factors such as stress can affect an animal's genetic expression.[58]

In humans, twin studies into addiction have provided some of the highest-quality evidence of this link, with results finding that if one twin is affected by addiction, the other twin is likely to be as well, and to the same substance.[59] Further evidence of a genetic component is research findings from family studies which suggest that if one family member has a history of addiction, the chances of a relative or close family developing those same habits are much higher than one who has not been introduced to addiction at a young age.[60]

The data implicating specific genes in the development of drug addiction is mixed for most genes. Many addiction studies that aim to identify specific genes focus on common variants with an allele frequency of greater than 5% in the general population. When associated with disease, these only confer a small amount of additional risk with an odds ratio of 1.1–1.3 percent; this has led to the development the rare variant hypothesis, which states that genes with low frequencies in the population (<1%) confer much greater additional risk in the development of the disease.[61]

Genome-wide association studies (GWAS) are used to examine genetic associations with dependence, addiction, and drug use.[55] These studies rarely identify genes from proteins previously described via animal knockout models and candidate gene analysis. Instead, large percentages of genes involved in processes such as cell adhesion are commonly identified. The important effects of endophenotypes are typically not capable of being captured by these methods. Genes identified in GWAS for drug addiction may be involved either in adjusting brain behavior before drug experiences, subsequent to them, or both.[62]

Environmental factors

[edit]Environmental risk factors for addiction are the experiences of an individual during their lifetime that interact with the individual's genetic composition to increase or decrease his or her vulnerability to addiction.[3] For example, after the nationwide[where?] outbreak of COVID-19, more people quit (vs. started) smoking; and smokers, on average, reduced the quantity of cigarettes they consumed.[63] More generally, a number of different environmental factors have been implicated as risk factors for addiction, including various psychosocial stressors. The National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA) and studies cite lack of parental supervision, the prevalence of peer substance use, substance availability, and poverty as risk factors for substance use among children and adolescents.[64][20] The brain disease model of addiction posits that an individual's exposure to an addictive drug is the most significant environmental risk factor for addiction.[65] Many researchers, including neuroscientists, indicate that the brain disease model presents a misleading, incomplete, and potentially detrimental explanation of addiction.[66]

The psychoanalytic theory model defines addiction as a form of defense against feelings of hopelessness and helplessness as well as a symptom of failure to regulate powerful emotions related to adverse childhood experiences (ACEs), various forms of maltreatment and dysfunction experienced in childhood. In this case, the addictive substance provides brief but total relief and positive feelings of control.[42] The Adverse Childhood Experiences Study by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention has shown a strong dose–response relationship between ACEs and numerous health, social, and behavioral problems throughout a person's lifespan, including substance use disorder.[67] Children's neurological development can be permanently disrupted when they are chronically exposed to stressful events such as physical, emotional, or sexual abuse, physical or emotional neglect, witnessing violence in the household, or a parent being incarcerated or having a mental illness. As a result, the child's cognitive functioning or ability to cope with negative or disruptive emotions may be impaired. Over time, the child may adopt substance use as a coping mechanism or as a result of reduced impulse control, particularly during adolescence.[67][20][42] Vast amounts of children who experienced abuse have gone on to have some form of addiction in their adolescence or adult life.[68] This pathway towards addiction that is opened through stressful experiences during childhood can be avoided by a change in environmental factors throughout an individual's life and opportunities of professional help.[68] If one has friends or peers who engage in drug use favorably, the chances of them developing an addiction increases. Family conflict and home management is a cause for one to become engaged in drug use.[69]

Social control theory

[edit]According to Travis Hirschi's social control theory, adolescents with stronger attachments to family, religious, academic, and other social institutions are less likely to engage in delinquent and maladaptive behavior such as drug use leading to addiction.[70]

Age

[edit]Adolescence represents a period of increased vulnerability for developing an addiction.[71] In adolescence, the incentive-rewards systems in the brain mature well before the cognitive control center. This consequentially grants the incentive-rewards systems a disproportionate amount of power in the behavioral decision-making process. Therefore, adolescents are increasingly likely to act on their impulses and engage in risky, potentially addictive behavior before considering the consequences.[72] Not only are adolescents more likely to initiate and maintain drug use, but once addicted they are more resistant to treatment and more liable to relapse.[73][74]

Most individuals are exposed to and use addictive drugs for the first time during their teenage years.[75] In the United States, there were just over 2.8 million new users of illicit drugs in 2013 (7,800 new users per day);[75] among them, 54.1% were under 18 years of age.[75] In 2011, there were approximately 20.6 million people in the United States over the age of 12 with an addiction.[76] Over 90% of those with an addiction began drinking, smoking or using illicit drugs before the age of 18.[76]

Comorbid disorders

[edit]Individuals with comorbid (i.e., co-occurring) mental health disorders such as depression, anxiety, attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) or post-traumatic stress disorder are more likely to develop substance use disorders.[77][78][79][20] The NIDA cites early aggressive behavior as a risk factor for substance use.[64] The National Bureau of Economic Research found that there is a "definite connection between mental illness and the use of addictive substances" and a majority of mental health patients participate in the use of these substances: 38% alcohol, 44% cocaine, and 40% cigarettes.[80]

Epigenetic

[edit]Epigenetics is the study of stable phenotypic changes that do not involve alterations in the DNA sequence.[81] Illicit drug use has been found to cause epigenetic changes in DNA methylation, as well as chromatin remodeling.[82] The epigenetic state of chromatin may pose as a risk for the development of substance addictions.[82] It has been found that emotional stressors, as well as social adversities may lead to an initial epigenetic response, which causes an alteration to the reward-signalling pathways.[82] This change may predispose one to experience a positive response to drug use.[82]

Transgenerational epigenetic inheritance

[edit]Epigenetic genes and their products (e.g., proteins) are the key components through which environmental influences can affect the genes of an individual:[53] they serve as the mechanism responsible for transgenerational epigenetic inheritance, a phenomenon in which environmental influences on the genes of a parent can affect the associated traits and behavioral phenotypes of their offspring (e.g., behavioral responses to environmental stimuli).[53] In addiction, epigenetic mechanisms play a central role in the pathophysiology of the disease;[3] it has been noted that some of the alterations to the epigenome which arise through chronic exposure to addictive stimuli during an addiction can be transmitted across generations, in turn affecting the behavior of one's children (e.g., the child's behavioral responses to addictive drugs and natural rewards).[53][83]

The general classes of epigenetic alterations that have been implicated in transgenerational epigenetic inheritance include DNA methylation, histone modifications, and downregulation or upregulation of microRNAs.[53] With respect to addiction, more research is needed to determine the specific heritable epigenetic alterations that arise from various forms of addiction in humans and the corresponding behavioral phenotypes from these epigenetic alterations that occur in human offspring.[53][83] Based on preclinical evidence from animal research, certain addiction-induced epigenetic alterations in rats can be transmitted from parent to offspring and produce behavioral phenotypes that decrease the offspring's risk of developing an addiction.[note 1][53] More generally, the heritable behavioral phenotypes that are derived from addiction-induced epigenetic alterations and transmitted from parent to offspring may serve to either increase or decrease the offspring's risk of developing an addiction.[53][83]

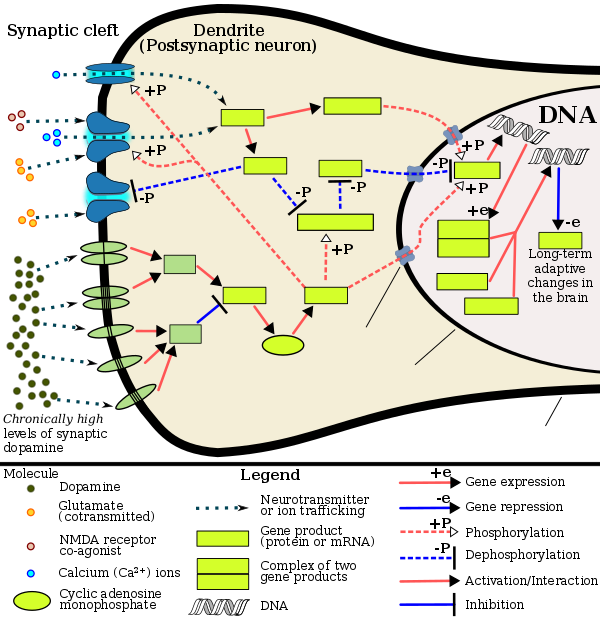

Mechanisms

[edit]Addiction is a disorder of the brain's reward system developing through transcriptional and epigenetic mechanisms as a result of chronically high levels of exposure to an addictive stimulus (e.g., eating food, the use of cocaine, engagement in sexual activity, participation in high-thrill cultural activities such as gambling, etc.) over extended time.[3][84][24] DeltaFosB (ΔFosB), a gene transcription factor, is a critical component and common factor in the development of virtually all forms of behavioral and drug addictions.[84][24][85][25] Two decades of research into ΔFosB's role in addiction have demonstrated that addiction arises, and the associated compulsive behavior intensifies or attenuates, along with the overexpression of ΔFosB in the D1-type medium spiny neurons of the nucleus accumbens.[3][84][24][85] Due to the causal relationship between ΔFosB expression and addictions, it is used preclinically as an addiction biomarker.[3][84][85] ΔFosB expression in these neurons directly and positively regulates drug self-administration and reward sensitization through positive reinforcement, while decreasing sensitivity to aversion.[note 2][3][84]

| Transcription factor glossary | |

|---|---|

| |

Chronic addictive drug use causes alterations in gene expression in the mesocorticolimbic projection.[25][93][94] The most important transcription factors that produce these alterations are ΔFosB, cAMP response element binding protein (CREB), and nuclear factor kappa B (NF-κB).[25] ΔFosB is the most significant biomolecular mechanism in addiction because the overexpression of ΔFosB in the D1-type medium spiny neurons in the nucleus accumbens is necessary and sufficient for many of the neural adaptations and behavioral effects (e.g., expression-dependent increases in drug self-administration and reward sensitization) seen in drug addiction.[25] ΔFosB expression in nucleus accumbens D1-type medium spiny neurons directly and positively regulates drug self-administration and reward sensitization through positive reinforcement while decreasing sensitivity to aversion.[note 2][3][84] ΔFosB has been implicated in mediating addictions to many different drugs and drug classes, including alcohol, amphetamine and other substituted amphetamines, cannabinoids, cocaine, methylphenidate, nicotine, opiates, phenylcyclidine, and propofol, among others.[84][25][93][95][96] ΔJunD, a transcription factor, and G9a, a histone methyltransferase, both oppose the function of ΔFosB and inhibit increases in its expression.[3][25][97] Increases in nucleus accumbens ΔJunD expression (via viral vector-mediated gene transfer) or G9a expression (via pharmacological means) reduces, or with a large increase can even block, many of the neural and behavioral alterations that result from chronic high-dose use of addictive drugs (i.e., the alterations mediated by ΔFosB).[85][25]

ΔFosB plays an important role in regulating behavioral responses to natural rewards, such as palatable food, sex, and exercise.[25][98] Natural rewards, like drugs of abuse, induce gene expression of ΔFosB in the nucleus accumbens, and chronic acquisition of these rewards can result in a similar pathological addictive state through ΔFosB overexpression.[24][25][98] Consequently, ΔFosB is the key transcription factor involved in addictions to natural rewards (i.e., behavioral addictions) as well;[25][24][98] in particular, ΔFosB in the nucleus accumbens is critical for the reinforcing effects of sexual reward.[98] Research on the interaction between natural and drug rewards suggests that dopaminergic psychostimulants (e.g., amphetamine) and sexual behavior act on similar biomolecular mechanisms to induce ΔFosB in the nucleus accumbens and possess bidirectional cross-sensitization effects that are mediated through ΔFosB.[24][33][34] This phenomenon is notable since, in humans, a dopamine dysregulation syndrome, characterized by drug-induced compulsive engagement in natural rewards (specifically, sexual activity, shopping, and gambling), has been observed in some individuals taking dopaminergic medications.[24]

ΔFosB inhibitors (drugs or treatments that oppose its action) may be an effective treatment for addiction and addictive disorders.[99]

The release of dopamine in the nucleus accumbens plays a role in the reinforcing qualities of many forms of stimuli, including naturally reinforcing stimuli like palatable food and sex.[100][101][12] Altered dopamine neurotransmission is frequently observed following the development of an addictive state.[24][18] In humans and lab animals that have developed an addiction, alterations in dopamine or opioid neurotransmission in the nucleus accumbens and other parts of the striatum are evident.[24] Use of certain drugs (e.g., cocaine) affect cholinergic neurons that innervate the reward system, in turn affecting dopamine signaling in this region.[102]

A recent study in Addiction reports that GLP-1 agonist medications, such as semaglutide, which are commonly used for diabetes and weight management, may also reduce the risk of overdose and alcohol intoxication in people with substance use disorders.[103] The study analyzed nearly nine years of health records from 1.3 million individuals across 136 U.S. hospitals, including 500,000 with opioid use disorder and over 800,000 with alcohol use disorder.[104] Researchers found that those who used Ozempic or similar medications had a 40% lower risk of opioid overdose and a 50% lower risk of alcohol intoxication compared to those not using these drugs.

Reward system

[edit]Mesocorticolimbic pathway

[edit]ΔFosB accumulation from excessive drug use

Top: this depicts the initial effects of high dose exposure to an addictive drug on gene expression in the nucleus accumbens for various Fos family proteins (i.e., c-Fos, FosB, ΔFosB, Fra1, and Fra2).

Bottom: this illustrates the progressive increase in ΔFosB expression in the nucleus accumbens following repeated twice daily drug binges, where these phosphorylated (35–37 kilodalton) ΔFosB isoforms persist in the D1-type medium spiny neurons of the nucleus accumbens for up to 2 months.[91][105] |

Understanding the pathways in which drugs act and how drugs can alter those pathways is key when examining the biological basis of drug addiction. The reward pathway, known as the mesolimbic pathway,[18] or its extension, the mesocorticolimbic pathway, is characterized by the interaction of several areas of the brain.

- The projections from the ventral tegmental area (VTA) are a network of dopaminergic neurons with co-localized postsynaptic glutamate receptors (AMPAR and NMDAR). These cells respond when stimuli indicative of a reward are present.[12] The VTA supports learning and sensitization development and releases dopamine (DA) into the forebrain.[106] These neurons project and release DA into the nucleus accumbens,[107] through the mesolimbic pathway. Virtually all drugs causing drug addiction increase the DA release in the mesolimbic pathway.[108][18]

- The nucleus accumbens (NAcc) is one output of the VTA projections. The nucleus accumbens itself consists mainly of GABAergic medium spiny neurons (MSNs).[109] The NAcc is associated with acquiring and eliciting conditioned behaviors, and is involved in the increased sensitivity to drugs as addiction progresses.[106][23] Overexpression of ΔFosB in the nucleus accumbens is a necessary common factor in essentially all known forms of addiction;[3] ΔFosB is a strong positive modulator of positively reinforced behaviors.[3]

- The prefrontal cortex, including the anterior cingulate and orbitofrontal cortices,[110][23] is another VTA output in the mesocorticolimbic pathway; it is important for the integration of information which helps determine whether a behavior will be elicited.[111] It is critical for forming associations between the rewarding experience of drug use and cues in the environment. Importantly, these cues are strong mediators of drug-seeking behavior and can trigger relapse even after months or years of abstinence.[112][18]

Other brain structures that are involved in addiction include:

- The basolateral amygdala projects into the NAcc and is thought to be important for motivation.[111]

- The hippocampus is involved in drug addiction, because of its role in learning and memory. Much of this evidence stems from investigations showing that manipulating cells in the hippocampus alters DA levels in NAcc and firing rates of VTA dopaminergic cells.[107]

Role of dopamine and glutamate

[edit]Dopamine is the primary neurotransmitter of the reward system in the brain. It plays a role in regulating movement, emotion, cognition, motivation, and feelings of pleasure.[113] Natural rewards, like eating, as well as recreational drug use cause a release of dopamine, and are associated with the reinforcing nature of these stimuli.[113][114][12] Nearly all addictive drugs, directly or indirectly, act on the brain's reward system by heightening dopaminergic activity.[115][18]

Excessive intake of many types of addictive drugs results in repeated release of high amounts of dopamine, which in turn affects the reward pathway directly through heightened dopamine receptor activation. Prolonged and abnormally high levels of dopamine in the synaptic cleft can induce receptor downregulation in the neural pathway. Downregulation of mesolimbic dopamine receptors can result in a decrease in the sensitivity to natural reinforcers.[113]

Drug seeking behavior is induced by glutamatergic projections from the prefrontal cortex to the nucleus accumbens. This idea is supported with data from experiments showing that drug seeking behavior can be prevented following the inhibition of AMPA glutamate receptors and glutamate release in the nucleus accumbens.[110]

Reward sensitization

[edit]| Target gene |

Target expression |

Neural effects | Behavioral effects |

|---|---|---|---|

| c-Fos | ↓ | Molecular switch enabling the chronic induction of ΔFosB[note 3] |

– |

| dynorphin | ↓ [note 4] |

• Downregulation of κ-opioid feedback loop | • Increased drug reward |

| NF-κB | ↑ | • Expansion of NAcc dendritic processes • NF-κB inflammatory response in the NAcc • NF-κB inflammatory response in the CP |

• Increased drug reward • Locomotor sensitization |

| GluR2 | ↑ | • Decreased sensitivity to glutamate | • Increased drug reward |

| Cdk5 | ↑ | • GluR1 synaptic protein phosphorylation • Expansion of NAcc dendritic processes |

Decreased drug reward (net effect) |

Reward sensitization is a process that causes an increase in the amount of reward (specifically, incentive salience[note 5]) that is assigned by the brain to a rewarding stimulus (e.g., a drug). In simple terms, when reward sensitization to a specific stimulus (e.g., a drug) occurs, an individual's "wanting" or desire for the stimulus itself and its associated cues increases.[118][117][119] Reward sensitization normally occurs following chronically high levels of exposure to the stimulus.[18] ΔFosB expression in D1-type medium spiny neurons in the nucleus accumbens has been shown to directly and positively regulate reward sensitization involving drugs and natural rewards.[3][84][85]

"Cue-induced wanting" or "cue-triggered wanting", a form of craving that occurs in addiction, is responsible for most of the compulsive behavior that people with addictions exhibit.[117][119] During the development of an addiction, the repeated association of otherwise neutral and even non-rewarding stimuli with drug consumption triggers an associative learning process that causes these previously neutral stimuli to act as conditioned positive reinforcers of addictive drug use (i.e., these stimuli start to function as drug cues).[117][120][119] As conditioned positive reinforcers of drug use, these previously neutral stimuli are assigned incentive salience (which manifests as a craving) – sometimes at pathologically high levels due to reward sensitization – which can transfer to the primary reinforcer (e.g., the use of an addictive drug) with which it was originally paired.[117][120][119]

Research on the interaction between natural and drug rewards suggests that dopaminergic psychostimulants (e.g., amphetamine) and sexual behavior act on similar biomolecular mechanisms to induce ΔFosB in the nucleus accumbens and possess a bidirectional reward cross-sensitization effect[note 6] that is mediated through ΔFosB.[24][33][34] In contrast to ΔFosB's reward-sensitizing effect, CREB transcriptional activity decreases user's sensitivity to the rewarding effects of the substance. CREB transcription in the nucleus accumbens is implicated in psychological dependence and symptoms involving a lack of pleasure or motivation during drug withdrawal.[3][105][116]

| Form of neuroplasticity or behavioral plasticity |

Type of reinforcer | Ref. | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Opiates | Psychostimulants | High fat or sugar food | Sexual intercourse | Physical exercise (aerobic) |

Environmental enrichment | ||

| ΔFosB expression in nucleus accumbens D1-type MSNs |

↑ | ↑ | ↑ | ↑ | ↑ | ↑ | [24] |

| Behavioral plasticity | |||||||

| Escalation of intake | Yes | Yes | Yes | [24] | |||

| Psychostimulant cross-sensitization |

Yes | Not applicable | Yes | Yes | Attenuated | Attenuated | [24] |

| Psychostimulant self-administration |

↑ | ↑ | ↓ | ↓ | ↓ | [24] | |

| Psychostimulant conditioned place preference |

↑ | ↑ | ↓ | ↑ | ↓ | ↑ | [24] |

| Reinstatement of drug-seeking behavior | ↑ | ↑ | ↓ | ↓ | [24] | ||

| Neurochemical plasticity | |||||||

| CREB phosphorylation in the nucleus accumbens |

↓ | ↓ | ↓ | ↓ | ↓ | [24] | |

| Sensitized dopamine response in the nucleus accumbens |

No | Yes | No | Yes | [24] | ||

| Altered striatal dopamine signaling | ↓DRD2, ↑DRD3 | ↑DRD1, ↓DRD2, ↑DRD3 | ↑DRD1, ↓DRD2, ↑DRD3 | ↑DRD2 | ↑DRD2 | [24] | |

| Altered striatal opioid signaling | No change or ↑μ-opioid receptors |

↑μ-opioid receptors ↑κ-opioid receptors |

↑μ-opioid receptors | ↑μ-opioid receptors | No change | No change | [24] |

| Changes in striatal opioid peptides | ↑dynorphin No change: enkephalin |

↑dynorphin | ↓enkephalin | ↑dynorphin | ↑dynorphin | [24] | |

| Mesocorticolimbic synaptic plasticity | |||||||

| Number of dendrites in the nucleus accumbens | ↓ | ↑ | ↑ | [24] | |||

| Dendritic spine density in the nucleus accumbens |

↓ | ↑ | ↑ | [24] | |||

Neuroepigenetic mechanisms

[edit]Altered epigenetic regulation of gene expression within the brain's reward system plays a significant and complex role in the development of drug addiction.[97][121] Addictive drugs are associated with three types of epigenetic modifications within neurons.[97] These are (1) histone modifications, (2) epigenetic methylation of DNA at CpG sites at (or adjacent to) particular genes, and (3) epigenetic downregulation or upregulation of microRNAs which have particular target genes.[97][25][121] As an example, while hundreds of genes in the cells of the nucleus accumbens (NAc) exhibit histone modifications following drug exposure – particularly, altered acetylation and methylation states of histone residues[121] – most other genes in the NAc cells do not show such changes.[97]

Diagnosis

[edit]Classification

[edit]DSM-5

[edit]The fifth edition of the DSM uses the term substance use disorder to refer to a spectrum of drug use-related disorders. The DSM-5 eliminates the terms abuse and dependence from diagnostic categories, instead using the specifiers of mild, moderate and severe to indicate the extent of disordered use. These specifiers are determined by the number of diagnostic criteria present in a given case. In the DSM-5, the term drug addiction is synonymous with severe substance use disorder.[122][15]

The DSM-5 introduced a new diagnostic category for behavioral addictions. Problem gambling is the only condition included in this category in the fifth edition.[123] Internet gaming disorder is listed as a "condition requiring further study" in the DSM-5.[124]

Past editions have used physical dependence and the associated withdrawal syndrome to identify an addictive state. Physical dependence occurs when the body has adjusted by incorporating the substance into its "normal" functioning – i.e., attains homeostasis – and therefore physical withdrawal symptoms occur on cessation of use.[125] Tolerance is the process by which the body continually adapts to the substance and requires increasingly larger amounts to achieve the original effects. Withdrawal refers to physical and psychological symptoms experienced when reducing or discontinuing a substance that the body has become dependent on. Symptoms of withdrawal generally include but are not limited to body aches, anxiety, irritability, intense cravings for the substance, dysphoria, nausea, hallucinations, headaches, cold sweats, tremors, and seizures. During acute physical opioid withdrawal, symptoms of restless legs syndrome are common and may be profound. This phenomenon originated the idiom "kicking the habit".

Medical researchers who actively study addiction have criticized the DSM classification of addiction for being flawed and involving arbitrary diagnostic criteria.[126]

ICD-11

[edit]The eleventh revision of the International Classification of Diseases, commonly referred to as ICD-11, conceptualizes diagnosis somewhat differently. ICD-11 first distinguishes between problems with psychoactive substance use ("Disorders due to substance use") and behavioral addictions ("Disorders due to addictive behaviours").[127] With regard to psychoactive substances, ICD-11 explains that the included substances initially produce "pleasant or appealing psychoactive effects that are rewarding and reinforcing with repeated use, [but] with continued use, many of the included substances have the capacity to produce dependence. They have the potential to cause numerous forms of harm, both to mental and physical health."[128] Instead of the DSM-5 approach of one diagnosis ("Substance Use Disorder") covering all types of problematic substance use, ICD-11 offers three diagnostic possibilities: 1) Episode of Harmful Psychoactive Substance Use, 2) Harmful Pattern of Psychoactive Substance Use, and 3) Substance Dependence.[128]

Screening and assessment

[edit]Addictions Neuroclinical Assessment

[edit]The Addictions Neuroclinical Assessment is used to diagnose addiction disorders. This tool measures three different domains: executive function, incentive salience, and negative emotionality.[129][130] Executive functioning consists of processes that would be disrupted in addiction.[130] In the context of addiction, incentive salience determines how one perceives the addictive substance.[130] Increased negative emotional responses have been found with individuals with addictions.[130]

Tobacco, Alcohol, Prescription Medication, and Other Substance Use (TAPS)

[edit]This is a screening and assessment tool in one, assessing commonly used substances. This tool allows for a simple diagnosis, eliminating the need for several screening and assessment tools, as it includes both TAPS-1 and TAPS-2, screening and assessment tools respectively. The screening component asks about the frequency of use of the specific substance (tobacco, alcohol, prescription medication, and other).[131] If an individual screens positive, the second component will begin. This dictates the risk level of the substance.[131]

CRAFFT

[edit]The CRAFFT (Car-Relax-Alone-Forget-Family and Friends-Trouble) is a screening tool that is used in medical centers. The CRAFFT is in version 2.1 and has a version for nicotine and tobacco use called the CRAFFT 2.1+N.[132] This tool is used to identify substance use, substance related driving risk, and addictions among adolescents. This tool uses a set of questions for different scenarios.[133] In the case of a specific combination of answers, different question sets can be used to yield a more accurate answer. After the questions, the DSM-5 criteria are used to identify the likelihood of the person having substance use disorder.[133] After these tests are done, the clinician is to give the "5 RS" of brief counseling.

The five Rs of brief counseling includes:[133]

- REVIEW screening results

- RECOMMEND to not use

- RIDING/DRIVING risk counseling

- RESPONSE: elicit self-motivational statements

- REINFORCE self-efficacy

Drug Abuse Screening Test (DAST-10)

[edit]The Drug Abuse Screening Test (DAST) is a self-reporting tool that measures problematic substance use.[134] Responses to this test are recorded as yes or no answers, and scored as a number between zero and 28. Drug abuse or dependence, are indicated by a cut off score of 6.[134] Three versions of this screening tool are in use: DAST-28, DAST-20, and DAST-10. Each of these instruments are copyrighted by Dr. Harvey A. Skinner.[134]

Alcohol, Smoking, and Substance Involvement Test (ASSIST)

[edit]The Alcohol, Smoking, and Substance Involvement Test (ASSIST) is an interview-based questionnaire consisting of eight questions developed by the WHO.[135] The questions ask about lifetime use; frequency of use; urge to use; frequency of health, financial, social, or legal problems related to use; failure to perform duties; if anyone has raised concerns over use; attempts to limit or moderate use; and use by injection.[136]

Prevention

[edit]Abuse liability

[edit]Abuse or addiction liability is the tendency to use drugs in a non-medical situation. This is typically for euphoria, mood changing, or sedation.[137] Abuse liability is used when the person using the drugs wants something that they otherwise can not obtain. The only way to obtain this is through the use of drugs. When looking at abuse liability there are a number of determining factors in whether the drug is abused. These factors are: the chemical makeup of the drug, the effects on the brain, and the age, vulnerability, and the health (mental and physical) of the population being studied.[137] There are a few drugs with a specific chemical makeup that leads to a high abuse liability. These are: cocaine, heroin, inhalants, marijuana, MDMA (ecstasy), methamphetamine, PCP, synthetic cannabinoids, synthetic cathinones (bath salts), nicotine (e.g. tobacco), and alcohol.[138]

Potential vaccines for addiction to substances

[edit]Vaccines for addiction have been investigated as a possibility since the early 2000s.[139] The general theory of a vaccine intended to "immunize" against drug addiction or other substance abuse is that it would condition the immune system to attack and consume or otherwise disable the molecules of such substances that cause a reaction in the brain, thus preventing the addict from being able to realize the effect of the drug. Addictions that have been floated as targets for such treatment include nicotine, opioids, and fentanyl.[140][141][142][143] Vaccines have been identified as potentially being more effective than other anti-addiction treatments, due to "the long duration of action, the certainty of administration and a potential reduction of toxicity to important organs".[144]

Specific addiction vaccines in development include:

- NicVAX, a conjugate vaccine intended to reduce or eliminate physical dependence on nicotine.[145] This proprietary vaccine is being developed by Nabi Biopharmaceuticals[146] of Rockville, MD. with the support from the U.S. National Institute on Drug Abuse. NicVAX consists of the hapten 3'-aminomethylnicotine which has been conjugated (attached) to Pseudomonas aeruginosa exotoxin A.[147]

- TA-CD, an active vaccine[148] developed by the Xenova Group which is used to negate the effects of cocaine. It is created by combining norcocaine with inactivated cholera toxin. It works in much the same way as a regular vaccine. A large protein molecule attaches to cocaine, which stimulates response from antibodies, which destroy the molecule. This also prevents the cocaine from crossing the blood–brain barrier, negating the euphoric high and rewarding effect of cocaine caused from stimulation of dopamine release in the mesolimbic reward pathway. The vaccine does not affect the user's "desire" for cocaine—only the physical effects of the drug.[149]

- TA-NIC, used to create human antibodies to destroy nicotine in the human body so that it is no longer effective.[150]

As of September 2023, it was further reported that a vaccine "has been tested against heroin and fentanyl and is on its way to being tested against OxyContin".[151]

Treatment

[edit]To be effective, treatment for addiction that is pharmacological or biologically based need to be accompanied by other interventions such as cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) and dialectical behavioral therapy (DBT); individual and group psychotherapy, behavior modification strategies, twelve-step programs, and residential treatment facilities.[152][20] The transtheoretical model (TTM) can be used to determine when treatment can begin and which method will be most effective. If treatment begins too early, it can cause a person to become defensive and resistant to change.[42][153]

Epidemiology

[edit]Due to cultural variations, the proportion of individuals who develop a drug or behavioral addiction within a specified time period (i.e., the prevalence) varies over time, by country, and across national population demographics (e.g., by age group, socioeconomic status, etc.).[53] Where addiction is viewed as unacceptable, there will be fewer people addicted.

Asia

[edit]The prevalence of alcohol dependence is not as high as is seen in other regions. In Asia, not only socioeconomic factors but biological factors influence drinking behavior.[154]

Internet addiction disorder is highest in the Philippines, according to both the IAT (Internet Addiction Test) – 5% and the CIAS-R (Revised Chen Internet Addiction Scale) – 21%.[155]

Australia

[edit]The prevalence of substance use disorder among Australians was reported at 5.1% in 2009.[156] In 2019 the Australian Institute of Health and Welfare conducted a national drug survey that quantified drug use for various types of drugs and demographics.[157] The survey found that in 2019, 11% of people over 14 years old smoke daily; that 9.9% of those who drink alcohol, which equates to 7.5% of the total population age 14 or older, may qualify as alcohol dependent; that 17.5% of the 2.4 million people who used cannabis in the last year may have hazardous use or a dependence problem; and that 63.5% of about 300000 recent users of meth and amphetamines were at risk for developing problem use.[157]

Europe

[edit]In 2015, the estimated prevalence among the adult population was 18.4% for heavy episodic alcohol use (in the past 30 days); 15.2% for daily tobacco smoking; and 3.8% for cannabis use, 0.77% for amphetamine use, 0.37% for opioid use, and 0.35% for cocaine use in 2017. The mortality rates for alcohol and illicit drugs were highest in Eastern Europe.[158] Data shows a downward trend of alcohol use among children 15 years old in most European countries between 2002 and 2014. First-time alcohol use before the age of 13 was recorded for 28% of European children in 2014.[20]

United States

[edit]Based on representative samples of the US youth population in 2011[update], the lifetime prevalence[note 7] of addictions to alcohol and illicit drugs has been estimated to be approximately 8% and 2–3% respectively.[159] Based on representative samples of the US adult population in 2011[update], the 12-month prevalence of alcohol and illicit drug addictions were estimated at 12% and 2–3% respectively.[159] The lifetime prevalence of prescription drug addictions is around 4.7%.[160]

As of 2021,[update] 43.7 million people aged 12 or older surveyed by the National Survey on Drug Use and Health in the United States needed treatment for an addiction to alcohol, nicotine, or other drugs. The groups with the highest number of people were 18–25 years (25.1%) and "American Indian or Alaska Native" (28.7%).[161] Only about 10%, or a little over 2 million, receive any form of treatments, and those that do generally do not receive evidence-based care.[162][163] One-third of inpatient hospital costs and 20% of all deaths in the US every year are the result of untreated addictions and risky substance use.[162][163] In spite of the massive overall economic cost to society, which is greater than the cost of diabetes and all forms of cancer combined, most doctors in the US lack the training to effectively address a drug addiction.[162][163]

Estimates of lifetime prevalence rates in the US are 1–2% for compulsive gambling, 5% for sexual addiction, 2.8% for food addiction, and 5–6% for compulsive shopping.[24] The time-invariant prevalence rate for sexual addiction and related compulsive sexual behavior (e.g., compulsive masturbation with or without pornography, compulsive cybersex, etc.) within the US ranges from 3–6% of the population.[32]

According to a 2017 poll conducted by the Pew Research Center, almost half of US adults know a family member or close friend who has struggled with a drug addiction at some point in their life.[164]

In 2019, opioid addiction was acknowledged as a national crisis in the United States.[165] An article in The Washington Post stated that "America's largest drug companies flooded the country with pain pills from 2006 through 2012, even when it became apparent that they were fueling addiction and overdoses."

The National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions found that from 2012 to 2013 the prevalence of Cannabis use disorder in U.S. adults was 2.9%.[166]

Canada

[edit]A Statistics Canada Survey in 2012 found the lifetime prevalence and 12-month prevalence of substance use disorders were 21.6%, and 4.4% in those 15 and older.[167] Alcohol abuse or dependence reported a lifetime prevalence of 18.1% and a 12-month prevalence of 3.2%.[167] Cannabis abuse or dependence reported a lifetime prevalence of 6.8% and a 12-month prevalence of 3.2%.[167] Other drug abuse or dependence has a lifetime prevalence of 4.0% and a 12-month prevalence of 0.7%.[167] Substance use disorder is a term used interchangeably with a drug addiction.[168]

In Ontario, Canada between 2009 and 2017, outpatient visits for mental health and addiction increased from 52.6 to 57.2 per 100 people, emergency department visits increased from 13.5 to 19.7 per 1000 people and the number of hospitalizations increased from 4.5 to 5.5 per 1000 people.[169] Prevalence of care needed increased the most among the 14–17 age group overall.[169]

South America

[edit]The realities of opioid use and opioid use disorder in Latin America may be deceptive if observations are limited to epidemiological findings. In the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime report,[170] although South America produced 3% of the world's morphine and heroin and 0.01% of its opium, prevalence of use is uneven. According to the Inter-American Commission on Drug Abuse Control, consumption of heroin is low in most Latin American countries, although Colombia is the area's largest opium producer. Mexico, because of its border with the United States, has the highest incidence of use.[171]

Etymology

[edit]The word addiction derives from the Latin "addico", meaning "giving over" with both positive connotations (devotion, dedication) and negative ones (being enslaved to a creditor in Roman law). This dual meaning persisted in traditional English dictionaries, encompassing both legal surrender and personal devotion to habits. Later, 19th century temperance movements narrowed the definition of addiction to just drug-related disease, ignoring behavioral addictions and the possibility of positive or neutral addictions. This restrictive view opposes the current understanding of addiction.[172]

Addiction and addictive behavior are polysemes denoting a category of mental disorders, of neuropsychological symptoms, or of merely maladaptive/harmful habits and lifestyles.[173] A common use of the term addiction in medicine is for neuropsychological symptoms denoting pervasive/excessive and intense urges to engage in a category of behavioral compulsions or impulses towards sensory rewards (e.g., alcohol, betel quid, drugs, sex, gambling, video gaming).[174][175][176][177][127] Addictive disorders or addiction disorders are mental disorders involving high intensities of addictions (as neuropsychological symptoms) that induce functional disabilities (i.e., limit subjects' social/family and occupational activities); the two categories of such disorders are substance-use addictions and behavioral addictions.[178][173][177][127]

The etymology of the term addiction throughout history has been misunderstood and has taken on various meanings associated with the word.[179] An example is the usage of the word in the religious landscape of early modern Europe.[180] "Addiction" at the time meant "to attach" to something, giving it both positive and negative connotations. The object of this attachment could be characterized as "good or bad".[181] The meaning of addiction during the early modern period was mostly associated with positivity and goodness;[180] during this early modern and highly religious era of Christian revivalism and Pietistic tendencies,[180] it was seen as a way of "devoting oneself to another".[181]

The suffixes "-holic" and "-holism"

[edit]In contemporary modern English "-holic" is a suffix that can be added to a subject to denote an addiction to it. It was extracted from the word alcoholism (one of the first addictions to be widely identified both medically and socially) (correctly the root "alcohol" plus the suffix "-ism") by misdividing or rebracketing it into "alco" and "-holism". There are correct medico-legal terms for such addictions: dipsomania is the medico-legal term for alcoholism;[182] other examples are in this table:[citation needed]

| Colloquial term | Addiction to | Medico-legal term |

|---|---|---|

| chocoholic | chocolate | |

| danceaholic | dance | choreomania |

| rageaholic | rage | |

| sexaholic | sex | hypersexuality, satyriasis, nymphomania |

| sugarholic | sugar | saccharomania |

| workaholic | work | ergomania |

History

[edit]Modern research on addiction has led to a better understanding of the disease with research on the topic dating back to 1875, specifically on morphine addiction.[183] This furthered the understanding of addiction being a medical condition. It was not until the 19th century that addiction was seen and acknowledged in the Western world as a disease, being both a physical condition and mental illness.[184] Today, addiction is understood both as a biopsychosocial and neurological disorder that negatively impacts those who are affected by it, most commonly associated with the use of drugs and excessive use of alcohol.[4] The understanding of addiction has changed throughout history, which has impacted and continues to impact the ways it is medically treated and diagnosed.[citation needed]

Addiction and art

[edit]The arts can be used in a variety of ways to address issues related to addiction. Art can be used as a form of therapy in the treatment of substance use disorders. Creative activities like painting, sculpting, music, and writing can help people express their feelings and experiences in safe and healthy ways. The arts can be used as an assessment tool to identify underlying issues that may be contributing to a person's substance use disorder. Through art, individuals can gain insights into their own motivations and behaviors that can be helpful in determining a course of treatment. Finally, the arts can be used to advocate for those suffering from a substance use disorder by raising awareness of the issue and promoting understanding and compassion. Through art, individuals can share their stories, increase awareness, and offer support and hope to those struggling with substance use disorders.

As therapy

[edit]Addiction treatment is complex and not always effective due to engagement and service availability concerns, so researchers prioritize efforts to improve treatment retention and decrease relapse rates.[185][186] Characteristics of substance abuse may include feelings of isolation, a lack of confidence, communication difficulties, and a perceived lack of control.[187] In a similar vein, people suffering from substance use disorders tend to be highly sensitive, creative, and as such, are likely able to express themselves meaningfully in creative arts such as dancing, painting, writing, music, and acting.[188] Further evidenced by Waller and Mahony (2002)[189] and Kaufman (1981),[190] the creative arts therapies can be a suitable treatment option for this population especially when verbal communication is ineffective.

Primary advantages of art therapy in the treatment of addiction have been identified as:[191][192]

- Assess and characterize a client's substance use issues

- Bypassing a client's resistances, defenses, and denial

- Containing shame or anger

- Facilitating the expression of suppressed and/or complicated emotions

- Highlighting a client's strengths

- Providing an alternative to verbal communication (via use of symbols) and conventional forms of therapy

- Providing clients with a sense of control

- Tackling feelings of isolation

Art therapy is an effective method of dealing with substance abuse in comprehensive treatment models. When included in psychoeducational programs, art therapy in a group setting can help clients internalize taught concepts in a more personalized manner.[193] During the course of treatment, by examining and comparing artwork created at different times, art therapists can be helpful in identifying and diagnosing issues, as well as charting the extent or direction of improvement as a person detoxifies.[193] Where increasing adherence to treatment regimes and maintaining abstinence is the target; art therapists can aid by customizing treatment directives (encourage the client to create collages that compare pros and cons, pictures that compare past and present and future, and drawings that depict what happened when a client went off medication).[193]

Art therapy can function as a complementary therapy used in conjunction with more conventional therapies and can integrate with harm reduction protocols to minimize the negative effects of drug use.[194][192] An evaluation of art therapy incorporation within a pre-existing Addiction Treatment Programme based on the 12 step Minnesota Model endorsed by the Alcoholics Anonymous found that 66% of participants expressed the usefulness of art therapy as a part of treatment.[195][192] Within the weekly art therapy session, clients were able to reflect and process the intense emotions and cognitions evoked by the programme. In turn, the art therapy component of the programme fostered stronger self-awareness, exploration, and externalization of repressed and unconscious emotions of clients, promoting the development of a more integrated 'authentic self'.[196][192]

Despite the large number of randomized control trials, clinical control trials, and anecdotal evidence supporting the effectiveness of art therapies for use in addiction treatment, a systematic review conducted in 2018 could not find enough evidence on visual art, drama, dance and movement therapy, or 'arts in health' methodologies to confirm their effectiveness as interventions for reducing substance misuse.[197] Music therapy was identified to have potentially strong beneficial effects in aiding contemplation and preparing those diagnosed with substance use for treatment.[197]

As an assessment tool

[edit]The Formal Elements Art Therapy Scale (FEATS) is an assessment tool used to evaluate drawings created by people suffering from substance use disorders by comparing them to drawings of a control group (consisting of individuals without SUDs).[198][192] FEATS consists of twelve elements, three of which were found to be particularly effective at distinguishing the drawings of those with SUDs from those without: Person, Realism, and Developmental. The Person element assesses the degree to which a human features are depicted realistically, the Realism element assesses the overall complexity of the artwork, and the Developmental element assesses "developmental age" of the artwork in relation to standardized drawings from children and adolescents.[198] By using the FEATS assessment tool, clinicians can gain valuable insight into the drawings of individuals with SUDs, and can compare them to those of the control group. Formal assessments such as FEATS provide healthcare providers with a means to quantify, standardize, and communicate abstract and visceral characteristics of SUDs to provide more accurate diagnoses and informed treatment decisions.[198]

Other artistic assessment methods include the Bird's Nest Drawing: a useful tool for visualizing a client's attachment security.[199][192] This assessment method looks at the amount of color used in the drawing, with a lack of color indicating an 'insecure attachment', a factor that the client's therapist or recovery framework must take into account.[200]

Art therapists working with children of parents suffering from alcoholism can use the Kinetic Family Drawings assessment tool to shed light on family dynamics and help children express and understand their family experiences.[201][192] The KFD can be used in family sessions to allow children to share their experiences and needs with parents who may be in recovery from alcohol use disorder. Depiction of isolation of self and isolation of other family members may be an indicator of parental alcoholism.[201]

Advocacy

[edit]Stigma can lead to feelings of shame that can prevent people with substance use disorders from seeking help and interfere with provision of harm reduction services.[202][203][204] It can influence healthcare policy, making it difficult for these individuals to access treatment.[205] For designing and implementing effective and evidence-based stigma prevention and intervention, it is important do both, identify persons who are more likely to be stigmatized (e.g., male or those addicted to drugs believed to be "stronger") and target those more likely to stigmatize (e.g., those with lacking or limited familiarity with addiction or more conservative individuals).[206][207][208][209]

Artists attempt to change the societal perception of addiction from a punishable moral offense to instead a chronic illness necessitating treatment. This form of advocacy can help to relocate the fight of addiction from a judicial perspective to the public health system.[210]

Artists who have personally lived with addiction or undergone recovery may use art to depict their experiences in a manner that uncovers the "human face of addiction". By bringing experiences of addiction and recovery to a personal level and breaking down the "us and them", the viewer may be more inclined to show compassion, forego stereotypes and stigma of addiction, and label addiction as a social rather than individual problem.[210]

According to Santora[210] the main purposes in using art as a form of advocacy in the education and prevention of substance use disorders include:

- Addiction art exhibitions can come from a variety of sources, but the underlying message of these works is the same: to communicate through emotions without relying on intellectually demanding/gatekept facts and figures. These exhibitions can either stand alone, reinforce, or challenge facts.

- A powerful educational tool for increasing awareness and understanding of addiction as a medical illness. Exhibitions featuring personal stories and images can help to create lasting impressions on diverse audiences (including addiction scientists/researchers, family/friends of those affected by addiction etc.), highlighting the humanity of the problem and in turn encouraging compassion and understanding.

- A way to destigmatize substance use disorders and shift public perception from viewing them as a moral failing to understanding them as a chronic medical condition which requires treatment.

- Provide those who are struggling with addiction assurance and encouragement of healing, and let them know that they are not alone in their struggle.

- The use of visual arts can help bring attention to the lack of adequate substance use treatment, prevention, and education programs and services in a healthcare system. Messages can encourage policymakers to allocate more resources to addiction treatment and prevention from federal, state, and local levels.

The Temple University College of Public Health department conducted a project to promote awareness around opioid use and reduce associated stigma by asking students to create art pieces that were displayed on a website they created and promoted via social media.[211] Quantitative and qualitative data was recorded to measure engagement, and the student artists were interviewed, which revealed a change in perspective and understanding, as well as greater appreciation of diverse experiences. Ultimately, the project found that art was an effective medium for empowering both the artist creating the work and the person interacting with it.[211]

Another author critically examined works by contemporary Canadian artists that deal with addiction via the metaphor of a cultural landscape to "unmap" and "remap" ideologies related to Indigenous communities and addiction to demonstrate how colonial violence in Canada has drastically impacted the relationship between Indigenous peoples, their land, and substance abuse.[212]

A project known as "Voice" was a collection of art, poetry and narratives created by women living with a history of addiction to explore women's understanding of harm reduction, challenge the effects of stigma and give voice to those who have historically been silenced or devalued.[213] In the project, nurses with knowledge of mainstream systems, aesthetic knowing, feminism and substance use organized weekly gatherings, wherein women with histories of substance use and addiction worked alongside a nurse to create artistic expressions. Creations were presented at several venues, including an International Conference on Drug Related Harm, a Nursing Conference and a local gallery to positive community response.[213]

Social scientific models

[edit]

Biopsychosocial–cultural–spiritual

[edit]While regarded biomedically as a neuropsychological disorder, addiction is multi-layered, with biological, psychological, social, cultural, and spiritual (biopsychosocial–cultural–spiritual) elements.[214][215] A biopsychosocial–cultural–spiritual approach fosters the crossing of disciplinary boundaries, and promotes holistic considerations of addiction.[216][217][218] A biopsychosocial–cultural–spiritual approach considers, for example, how physical environments influence experiences, habits, and patterns of addiction.

Ethnographic engagements and developments in fields of knowledge have contributed to biopsychosocial–cultural–spiritual understandings of addiction, including the work of Philippe Bourgois, whose fieldwork with street-level drug dealers in East Harlem highlights correlations between drug use and structural oppression in the United States.[219] Prior models that have informed the prevailing biopsychosocial–cultural–spiritual consideration of addiction include:

Cultural model

[edit]The cultural model, an anthropological understanding of the emergence of drug use and abuse, was developed by Dwight Heath.[220] Heath undertook ethnographic research and fieldwork with the Camba people of Bolivia from June 1956 to August 1957.[221] Heath observed that adult members of society drank 'large quantities of rum and became intoxicated for several contiguous days at least twice a month'.[220] This frequent, heavy drinking from which intoxication followed was typically undertaken socially, during festivals.[221] Having returned in 1989, Heath observed that while much had changed, 'drinking parties' remained, as per his initial observations, and 'there appear to be no harmful consequences to anyone'.[222] Heath's observations and interactions reflected that this form of social behavior, the habitual heavy consumption of alcohol, was encouraged and valued, enforcing social bonds in the Camba community.[221] Despite frequent intoxication, "even to the point of unconsciousness", the Camba held no concept of alcoholism (a form of addiction), and no visible social problems associated with drunkenness, or addiction, were apparent.[220]

As noted by Merrill Singer, Heath's findings, when considered alongside subsequent cross-cultural experiences, challenged the perception that intoxication is socially 'inherently disruptive'.[220] Following this fieldwork, Heath proposed the 'cultural model', suggesting that 'problems' associated with heavy drinking, such as alcoholism – a recognised form addiction – were cultural: that is, that alcoholism is determined by cultural beliefs, and therefore varies among cultures. Heath's findings challenged the notion that 'continued use [of alcohol] is inexorably addictive and damaging to the consumer's health'.[221][220]

The cultural model did face criticism by Sociologist Robin Room and others, who felt anthropologists could "downgrade the severity of the problem".[220] Merrill Singer found it notable that the ethnographers working within the prominence of the cultural model were part of the 'wet generation': while not blind to the 'disruptive, dysfunctional and debilitating effects of alcohol consumption', they were products 'socialized to view alcohol consumption as normal'.[220]

Subcultural model

[edit]Historically, addiction has been viewed from the etic perspective, defining users through the pathology of their condition.[223] As reports of drug use rapidly increased, the cultural model found application in anthropological research exploring western drug subculture practices.[220]

The approach evolved from the ethnographic exploration into the lived experiences and subjectivities of 1960s and 70s drug subcultures.[220] The seminal publication "Taking care of business", by Edward Preble and John J. Casey, documented the daily lives of New York street-based intravenous heroin users in detail, providing insight into the dynamic social worlds and activities that surrounded their drug use.[224] These findings challenge popular narratives of immorality and deviance, conceptualizing substance abuse as a social phenomenon. The prevailing culture can have an influence on drug taking behaviors, along with the physical and psychological effects of the drug.[225] To marginalized individuals, drug subcultures can provide social connection, symbolic meaning, and socially constructed purpose that they may feel is unattainable through conventional means.[225] The subcultural model demonstrates the complexities of addiction, highlighting the need for an integrated approach. It contends that a biosocial approach is required to achieve a holistic understanding of addiction.[220]

Critical medical anthropology model

[edit]Emerging in the early 1980s, the critical medical anthropology model was introduced, and as Merrill Singer offers 'was applied quickly to the analysis of drug use'.[220] Where the cultural model of the 1950s looked at the social body, the critical medical anthropology model revealed the body politic, considering drug use and addiction within the context of macro level structures including larger political systems, economic inequalities, and the institutional power held over social processes.[220]

Highly relevant to addiction, the three issues emphasized in the model are:

- Self-medication

- The social production of suffering

- The political economy (Licit and Illicit Drugs)[220]

These three key points highlight how drugs may come to be used to self-medicate the psychological trauma of socio-political disparity and injustice, intertwining with licit and illicit drug market politics.[220] Social suffering, "the misery among those on the weaker end of power relations in terms of physical health, mental health and lived experience", is used by anthropologists to analyze how individuals may have personal problems caused by political and economic power.[220] From the perspective of critical medical anthropology heavy drug use and addiction is a consequence of such larger scale unequal distributions of power.[220]

The three models developed here – the cultural model, the subcultural model, and the Critical Medical Anthropology Model – display how addiction is not an experience to be considered only biomedically. Through consideration of addiction alongside the biological, psychological, social, cultural and spiritual (biopsychosocial–spiritual) elements which influence its experience, a holistic and comprehensive understanding can be built.

Social learning models

[edit]Social learning theory

[edit]Albert Bandura's 1977 social learning theory posits that individuals acquire addictive behaviors by observing and imitating models in their social environment.[226][227] The likelihood of engaging in and sustaining similar addictive behaviors is influenced by the reinforcement and punishment observed in others. The principle of reciprocal determinism suggests that the functional relationships between personal, environmental, and behavioral factors act as determinants of addictive behavior.[228] Thus, effective treatment targets each dynamic facet of the biopsychosocial disorder.

Transtheoretical model (stages of change model)

[edit]The transtheoretical model of change suggests that overcoming an addiction is a stepwise process that occurs through several stages.[229]

Precontemplation: This initial stage precedes individuals considering a change in their behavior. They might be oblivious to or in denial of their addiction, failing to recognize the need for change.