Recent from talks

Contribute something

Nothing was collected or created yet.

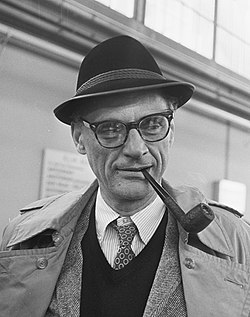

Arthur Miller

View on Wikipedia

Arthur Asher Miller (October 17, 1915 – February 10, 2005) was an American actor and writer of plays in the 20th-century American theater. Among his most popular plays are All My Sons (1947), Death of a Salesman (1949), The Crucible (1953), and A View from the Bridge (1955). He wrote several screenplays, including The Misfits (1961). The drama Death of a Salesman is considered one of the best American plays of the 20th century.

Key Information

Miller was often in the public eye, particularly during the late 1940s, 1950s and early 1960s. During this time, he received a Pulitzer Prize for Drama, testified before the House Un-American Activities Committee, and married Marilyn Monroe. In 1980, he received the St. Louis Literary Award from the Saint Louis University Library Associates.[1][2] He received the Praemium Imperiale prize in 2001, the Prince of Asturias Award in 2002, and the Jerusalem Prize in 2003, and the Dorothy and Lillian Gish Prize in 1999.[3]

Early life and education

[edit]Miller was born in the Harlem area of Manhattan, New York in 1915. He was the second of three children of Augusta (Barnett) and Isidore Miller. He was born into a Jewish family of Polish-Jewish descent.[4] His father was born in Radomyśl Wielki, Galicia (then part of Austria-Hungary, now Poland), and his mother was a native of New York whose parents also arrived from that town.[5] Isidore owned a women's clothing manufacturing business employing 400 people. He became a well respected man in the community.[6] The family, including Miller's younger sister Joan Copeland, lived on West[7] 110th Street in Manhattan, owned a summer house in Far Rockaway, Queens, and employed a chauffeur.[8] In the Wall Street crash of 1929, the family lost almost everything and moved to Gravesend, Brooklyn.[9] According to Peter Applebome, they moved to Midwood.[10]

As a teenager, Miller delivered bread every morning before school to help the family.[8] Miller later published an account of his early years under the title "A Boy Grew in Brooklyn". After graduating in 1932 from Abraham Lincoln High School, he worked at several menial jobs to pay for his college tuition at the University of Michigan.[9][11] After graduation (c. 1936), he worked as a psychiatric aide and copywriter before accepting faculty posts at New York University and University of New Hampshire. On May 1, 1935, he joined the League of American Writers (1935–1943), whose members included Alexander Trachtenberg of International Publishers, Franklin Folsom, Louis Untermeyer, I. F. Stone, Myra Page, Millen Brand, Lillian Hellman and Dashiell Hammett. Members were largely either Communist Party members or fellow travelers.[12]

At the University of Michigan, Miller first majored in journalism and wrote for the student newspaper, The Michigan Daily, and the satirical Gargoyle Humor Magazine. It was during this time that he wrote his first play, No Villain.[13] He switched his major to English, and subsequently won the Avery Hopwood Award for No Villain. The award led him to consider that he could have a career as a playwright. He enrolled in a playwriting seminar with the influential Professor Kenneth Rowe,[14] who emphasized how a play was built to achieve its intended effect, or what Miller called "the dynamics of play construction".[15] Rowe gave Miller realistic feedback and much-needed encouragement, and became a lifelong friend.[16] Miller retained strong ties to his alma mater through the rest of his life, establishing the university's Arthur Miller Award in 1985 and the Arthur Miller Award for Dramatic Writing in 1999, and lending his name to the Arthur Miller Theatre in 2000.[17] In 1937, Miller wrote Honors at Dawn, which also received the Avery Hopwood Award.[13] After his graduation in 1938, he joined the Federal Theatre Project, a New Deal agency established to provide jobs in the theater. He chose the theater project despite the more lucrative offer to work as a scriptwriter for 20th Century Fox.[13] However, Congress, worried about possible Communist infiltration, closed the project in 1939.[9] Miller began working in the Brooklyn Navy Yard while continuing to write radio plays, some of which were broadcast on CBS.[9][13]

Career

[edit]1940–1949: Early career

[edit]Miller was exempted from military service during World War II because of a high school football injury to his left kneecap.[9] In 1944 Miller's first play was produced: The Man Who Had All the Luck won the Theatre Guild's National Award.[18] The play closed after four performances with disastrous reviews.[19]

In 1947, Miller's play All My Sons, the writing of which had commenced in 1941, was a success on Broadway (earning him his first Tony Award, for Best Author) and his reputation as a playwright was established.[20] Years later, in a 1994 interview with Ron Rifkin, Miller said that most contemporary critics regarded All My Sons as "a very depressing play in a time of great optimism" and that positive reviews from Brooks Atkinson of The New York Times had saved it from failure.[21]

In 1948, Miller built a small studio in Roxbury, Connecticut. There, in less than a day, he wrote Act I of Death of a Salesman. Within six weeks, he completed the rest of the play,[13] one of the classics of world theater.[9][22] Death of a Salesman premiered on Broadway on February 10, 1949, at the Morosco Theatre, directed by Elia Kazan, and starring Lee J. Cobb as Willy Loman, Mildred Dunnock as Linda, Arthur Kennedy as Biff, and Cameron Mitchell as Happy. The play was commercially successful and critically acclaimed, winning a Tony Award for Best Author, the New York Drama Circle Critics' Award, and the Pulitzer Prize for Drama. It was the first play to win all three of these major awards. The play was performed 742 times.[9]

In 1949, Miller exchanged letters with Eugene O'Neill regarding Miller's production of All My Sons. O'Neill had sent Miller a congratulatory telegram; in response, he wrote a letter that consisted of a few paragraphs detailing his gratitude for the telegram, apologizing for not responding earlier, and inviting Eugene to the opening of Death of a Salesman. O'Neill replied, accepting the apology, but declining the invitation, explaining that his Parkinson's disease made it difficult to travel. He ended the letter with an invitation to Boston, a trip that never occurred.[23]

1950–1963: Critical years and HUAC controversy

[edit]In 1952, Elia Kazan appeared before the House Un-American Activities Committee (HUAC). Kazan named eight members of the Group Theatre, including Clifford Odets, Paula Strasberg, Lillian Hellman, J. Edward Bromberg, and John Garfield,[24] who in recent years had been fellow members of the Communist Party.[25] Miller and Kazan were close friends throughout the late 1940s and early 1950s, but after Kazan's testimony to the HUAC, the pair's friendship ended.[25] After speaking with Kazan about his testimony, Miller traveled to Salem, Massachusetts, to research the witch trials of 1692.[26] He and Kazan did not speak to each other for the next ten years. Kazan later defended his own actions through his film On the Waterfront, in which a dockworker heroically testifies against a corrupt union boss.[27] Miller would retaliate against Kazan's work by writing A View from the Bridge, a play where a longshoreman outs his co-workers motivated only by jealousy and greed. He sent a copy of the initial script to Kazan and when the director asked in jest to direct the movie, Miller replied "I only sent you the script to let you know what I think of stool-pigeons."[28]

In The Crucible, which was first performed at the Martin Beck Theatre on Broadway on January 22, 1953, Miller likened the situation with the House Un-American Activities Committee to the witch hunt in Salem in 1692.[29][30][31] Though widely considered only somewhat successful at the time of its release, The Crucible is Miller's most frequently produced work throughout the world.[26] It was adapted into an opera by Robert Ward in 1961. Earlier in 1955, a one-act version of Miller's verse drama, titled A View from the Bridge, opened on Broadway in a joint bill with one of Miller's lesser-known plays, A Memory of Two Mondays. The following year, Miller revised A View from the Bridge as a two-act prose drama, which Peter Brook directed in London.[32] A French-Italian co-production Vu du pont, based on the play, was released in 1962.[33]

The HUAC took an interest in Miller himself not long after The Crucible opened, engineering the US State Department's denying him a passport to attend the play's London opening in 1954.[13] When Miller applied in 1956 for a routine renewal of his passport, the House Un-American Activities Committee used this opportunity to subpoena him to appear before the committee. Before appearing, Miller asked the committee not to ask him to name names, to which the chairman, Francis E. Walter (D-PA) agreed.[34] When Miller attended the hearing, to which Monroe accompanied him, risking her own career,[26] he gave the committee a detailed account of his political activities.[35] Miller emphasized that his cooperation with various Communist-front organizations had been unfortunate and a mistake. He stressed his own patriotism and portrayed himself as a changed man who regretted his errors. “I think it would be a disaster and a calamity if the Communist Party ever took over this country,” said Miller. “That is an opinion that has come to me not out of the blue sky but out of long thought.”[36] Reneging on the chairman's promise, the committee demanded the names of friends and colleagues who had participated in similar activities.[34] Miller refused to comply, saying "I could not use the name of another person and bring trouble on him."[34] As a result, a judge found Miller guilty of contempt of Congress in May 1957. Miller was sentenced to a fine and a prison sentence, blacklisted from Hollywood, and disallowed a US passport.[37] In August 1958, his conviction was overturned by the court of appeals, which ruled that Miller had been misled by the chairman of the HUAC.[34]

Miller's experience with the HUAC affected him throughout his life. In the late 1970s, he joined other celebrities (including William Styron and Mike Nichols) who were brought together by the journalist Joan Barthel. Barthel's coverage of the highly publicized Barbara Gibbons murder case helped raise bail for Gibbons' son Peter Reilly, who had been convicted of his mother's murder based on what many felt was a coerced confession and little other evidence.[38] Barthel documented the case in her book A Death in Canaan, which was made as a television film of the same name and broadcast in 1978.[39] City Confidential, an A&E Network series, produced an episode about the murder, postulating that part of the reason Miller took such an active interest (including supporting Reilly's defense and using his own celebrity to bring attention to Reilly's plight) was because he had felt similarly persecuted in his run-ins with the HUAC. He sympathized with Reilly, whom he firmly believed to be innocent and to have been railroaded by the Connecticut State Police and the Attorney General who had initially prosecuted the case.[40][41]

Miller began work on writing the screenplay for The Misfits in 1960, directed by John Huston and starring Monroe. It was during the filming that Miller's and Monroe's relationship hit difficulties, and he later said that the filming was one of the lowest points in his life.[42] Monroe was taking drugs to help her sleep and other drugs to help her wake up, arriving on the set late, and having trouble remembering her lines. Huston was unaware that Miller and Monroe were having problems in their private life. He recalled later, "I was impertinent enough to say to Arthur that to allow her to take drugs of any kind was criminal and utterly irresponsible. Shortly after that I realized that she wouldn't listen to Arthur at all; he had no say over her actions."[43]

Shortly before the film's premiere in 1961, Miller and Monroe divorced after five years of marriage.[13] Nineteen months later, on August 5, 1962, Monroe died of a likely drug overdose.[44] Huston, who had also directed her in her first major role in The Asphalt Jungle in 1950, and who had seen her rise to stardom, put the blame for her death on her doctors as opposed to the stresses of being a star: "The girl was an addict of sleeping pills and she was made so by the God-damn doctors. It had nothing to do with the Hollywood set-up."[45]

1964–2004: Later career

[edit]In 1964, After the Fall was produced, and is said to be a deeply personal view of Miller's experiences during his marriage to Monroe. It reunited Miller with his former friend Kazan; they collaborated on the script and direction. It opened on January 23, 1964, at the ANTA Theatre in Washington Square Park amid a flurry of publicity and outrage at putting a Monroe-like character, Maggie, on stage.[26] Robert Brustein, in a review in the New Republic, called After the Fall "a three and one half hour breach of taste, a confessional autobiography of embarrassing explicitness ... There is a misogynistic strain in the play which the author does not seem to recognize. ... He has created a shameless piece of tabloid gossip, an act of exhibitionism which makes us all voyeurs ... a wretched piece of dramatic writing."[46] That year, Miller produced Incident at Vichy. In 1965, he was elected the first American president of PEN International, a position which he held for four years.[47] A year later, he organized the 1966 PEN congress in New York City. He also wrote the penetrating family drama The Price, produced in 1968.[26] It was his most successful play since Death of a Salesman.[48]

In 1968, Miller attended the Democratic National Convention as a delegate for Eugene McCarthy.[49] In 1969, Miller's works were banned in the Soviet Union after he campaigned for the freedom of dissident writers.[13] Throughout the 1970s, he spent much of his time experimenting with the theatre, producing one-act plays such as Fame and The Reason Why, and traveling with his wife, producing In the Country and Chinese Encounters with her. Both his 1972 comedy The Creation of the World and Other Business and its musical adaptation, Up from Paradise, were critical and commercial failures.[50][51]

Miller was an unusually articulate commentator on his own work. In 1978, he published a collection of his Theater Essays, edited by Robert A. Martin and with a foreword by Miller. Highlights of the collection included Miller's introduction to his Collected Plays, his reflections on the theory of tragedy, comments on the McCarthy Era, and pieces arguing for a publicly supported theater. Reviewing this collection in the Chicago Tribune, Studs Terkel remarked, "In reading [the Theater Essays] ... you are exhilaratingly aware of a social critic, as well as a playwright, who knows what he's talking about."[52]

In 1983, Miller traveled to China to produce and direct Death of a Salesman at the People's Art Theatre in Beijing. It was a success in China[48] and in 1984, Salesman in Beijing, a book about Miller's experiences in Beijing, was published. Around the same time, Death of a Salesman was adapted into a television film starring Dustin Hoffman as Willy Loman. The film was broadcast on CBS, and garnered an audience viewership of 25 million.[13][53] In late 1987, Miller's autobiographical work, Timebends, was published. Before it was published, it was well known that Miller would not talk about Monroe in interviews; however, in the book, he wrote extensively in detail about his experiences with Monroe.[26]

During the early 1990s, Miller wrote three new plays: The Ride Down Mt. Morgan (1991), The Last Yankee (1992), and Broken Glass (1994). In 1996, a film adaptation of The Crucible starring Daniel Day-Lewis, Paul Scofield, Bruce Davison and Winona Ryder was released. Miller spent much of 1996 working on the screenplay.[13]

Mr. Peters' Connections was staged Off-Broadway in 1998, and Death of a Salesman was revived on Broadway in 1999 to celebrate its 50th anniversary. The 1999 revival ran for 274 performances at the Eugene O'Neill Theatre, starring Brian Dennehy as Willy Loman. Once again, it was a large critical success, winning a Tony Award for Best Revival of a Play.[54]

In 1993, Miller received the National Medal of Arts.[55] He was honored with the PEN/Laura Pels Theater Award for a Master American Dramatist in 1998. In 2001, the National Endowment for the Humanities selected him for the Jefferson Lecture, the U.S. federal government's highest honor for achievement in the humanities.[56] His lecture, "On Politics and the Art of Acting",[57] analyzed political events (including the U.S. presidential election of 2000) in terms of the "arts of performance". It drew attacks from some conservatives[58] such as Jay Nordlinger, who called it "a disgrace";[59] and George Will, who argued that Miller was not a legitimate "scholar".[60]

In October 1999, Miller received The Dorothy and Lillian Gish Prize, given annually to "a man or woman who has made an outstanding contribution to the beauty of the world and to mankind's enjoyment and understanding of life".[61] Additionally in 1999, San Jose State University honored Miller with the John Steinbeck "In the Souls of the People" Award, which is given to those who capture "Steinbeck's empathy, commitment to democratic values, and belief in the dignity of people who by circumstance are pushed to the fringes."[62] In 2001, he received the National Book Foundation's Medal for Distinguished Contribution to American Letters.[63] On May 1, 2002, he received Spain's Principe de Asturias Prize for Literature as "the undisputed master of modern drama". Later that year, Ingeborg Morath died of lymphatic cancer[64] at the age of 78. The following year, Miller won the Jerusalem Prize.[13]

In December 2004, 89-year-old Miller announced that he had been in love with 34-year-old minimalist painter Agnes Barley and had been living with her at his Connecticut farm since 2002, and that they intended to marry.[65] Miller's final play, Finishing the Picture, opened at the Goodman Theatre, Chicago, in the fall of 2004, with one character said to be based on Barley.[66] It was reportedly based on his experience during the filming of The Misfits,[67] though Miller insisted the play was a work of fiction with independent characters that were no more than composite shadows of history.[68]

Personal life

[edit]Marriages and family

[edit]In 1940, Miller married Mary Grace Slattery.[26] The couple had two children, Jane (born September 7, 1944) and Robert (May 31, 1947 – March 6, 2022).[69]

In June 1956, Miller left Slattery and wed film star Marilyn Monroe.[26] Miller and Monroe had met in 1951, had a brief affair, and remained in contact.[9][26] Monroe had just turned 30 when they married; she never had a real family of her own and was eager to join the family of her new husband.[70]: 156

Monroe began to reconsider her career and the fact that trying to manage it made her feel helpless. She admitted to Miller, "I hate Hollywood. I don't want it any more. I want to live quietly in the country and just be there when you need me. I can't fight for myself any more."[70]: 154 Monroe converted to Judaism to "express her loyalty and get close to both Miller and his parents", writes biographer Jeffrey Meyers.[70]: 156 Soon after Monroe converted, Egypt banned all of her movies.[70]: 157 Away from Hollywood and the culture of celebrity, Monroe's life became more normal; she began cooking, keeping house, and giving Miller more attention and affection than he had been used to.[70]: 157

Later that year, Miller was subpoenaed by the House Un-American Activities Committee, and Monroe accompanied him.[31] In her personal notes, she wrote about her worries during this period:

I am so concerned about protecting Arthur. I love him—and he is the only person—human being I have ever known that I could love not only as a man to which I am attracted to practically out of my senses—but he is the only person—as another human being that I trust as much as myself...[71]

During the filming of the 1961 film The Misfits, which Miller wrote the script for, Miller and Monroe's marriage dissolved.[42] Monroe obtained a Mexican divorce from Miller in January 1961.[72]

In February 1962, Miller married photographer Inge Morath, who had worked as a photographer documenting the production of The Misfits. The first of their two children, Rebecca, was born September 15, 1962. Their son Daniel was born with Down syndrome in November 1966. Against his wife's wishes, Miller had him institutionalized, first at a home for infants in New York City, then at the Southbury Training School in Connecticut. Though Morath visited Daniel often, Miller never visited him at the school and rarely spoke of him; Daniel left Southbury at the age of 17 and gradually went from living in a group home to living in an apartment with occasional visits by a social worker.[73][74] Miller and Inge remained together until her death in 2002. Miller's son-in-law, actor Daniel Day-Lewis, visited Daniel frequently and persuaded Miller to meet with him. At one point, Miller answered a question about his son by stating, "Well, he knows I’m a person, and he knows my name, but he doesn’t understand what it means to be a son.” When Inge died, Miller stated that they had only had one child together; Daniel did not attend her funeral. When Miller died, Daniel was named as an heir along with his three other children.[75]

Death

[edit]Miller died on the evening of February 10, 2005 (the 56th anniversary of the Broadway debut of Death of a Salesman), at age 89 of bladder cancer and heart failure, at his home in Roxbury, Connecticut. He had been in hospice care at his sister's apartment in New York since his release from the hospital the previous month.[76] He was surrounded by his companion (painter Agnes Barley), family, and friends.[77][78] His body was interred at Roxbury Center Cemetery in Roxbury. Within hours of her father's death, Rebecca Miller, who had been consistently opposed to the relationship with Barley, ordered her to vacate the home she shared with Arthur.[79]

Legacy

[edit]Miller's writing career spanned over seven decades, and at the time of his death, he was considered one of the 20th century's greatest dramatists.[22] After his death, many respected actors, directors, and producers paid tribute to him,[80] some calling him the last great practitioner of the American stage,[81] and Broadway theatres darkened their lights in a show of respect.[82] Miller's alma mater, the University of Michigan, opened the Arthur Miller Theatre in March 2007. Per his express wish, it is the only theater in the world that bears his name.[83]

Miller's letters, notes, drafts and other papers are housed at the Harry Ransom Humanities Research Center at the University of Texas at Austin. Miller is also a member of the American Theater Hall of Fame. He was inducted in 1979.[84][85] In 1993, he received the Four Freedoms Award for Freedom of Speech.[86] In 2017, his daughter, Rebecca Miller, a writer and filmmaker, completed a documentary about her father's life, Arthur Miller: Writer.[87] Minor planet 3769 Arthurmiller is named after him.[88] In the 2022 Netflix film Blonde, Miller was portrayed by Adrien Brody.[89]

Foundation

[edit]The Arthur Miller Foundation was founded to honor the legacy of Miller and the New York City Public School education. Its mission is "Promoting increased access and equity to theater arts education in our schools and increasing the number of students receiving theater arts education as an integral part of their academic curriculum."[90] Its other initiatives include certification of new theater teachers and their placement in public schools, increasing the number of theater teachers in the system from the current[as of?] estimate of 180 teachers in 1800 schools, supporting professional development of all certified theater teachers, and providing teaching artists, cultural partners, physical spaces, and theater ticket allocations for students. The foundation's primary purpose is to provide arts education in the New York City school system. Its current chancellor is Carmen Farina, a prominent proponent of the Common Core State Standards Initiative. The Master Arts Council includes Alec Baldwin, Ellen Barkin, Bradley Cooper, Dustin Hoffman, Scarlett Johansson, Tony Kushner, Julianne Moore, Michael Moore, Liam Neeson, David O. Russell, and Liev Schreiber. Miller's son-in-law, Daniel Day-Lewis, has served on the current board of directors since 2016.[91]

The foundation celebrated Miller's 100th birthday with a one-night performance of his seminal works in November 2015.[92] The Arthur Miller Foundation currently supports a pilot program in theater and film at the public school Quest to Learn, in partnership with the Institute of Play. The model is being used as an in-school elective theater class and lab. Its objective is to create a sustainable theater education model to disseminate to teachers at professional development workshops.[93]

Archive

[edit]Miller donated thirteen boxes of his earliest manuscripts to the Harry Ransom Center at the University of Texas at Austin in 1961 and 1962.[94] This collection included the original handwritten notebooks and early typed drafts for Death of a Salesman, The Crucible, All My Sons, and other works. In January 2018, the Ransom Center announced the acquisition of the remainder of the Miller archive, totaling over 200 boxes.[95][96] The full archive opened in November 2019.[97]

Literary and public criticism

[edit]Christopher Bigsby wrote Arthur Miller: The Definitive Biography based on boxes of papers Miller made available to him before his death in 2005.[98] The book was published in November 2008, and is reported to reveal unpublished works in which Miller "bitterly attack[ed] the injustices of American racism long before it was taken up by the civil rights movement".[98] In his book Trinity of Passion, author Alan M. Wald conjectures that Miller was "a member of a writer's unit of the Communist Party around 1946", using the pseudonym Matt Wayne, and editing a drama column in the magazine The New Masses.[99]

In 1999, the writer Christopher Hitchens attacked Miller for comparing the Monica Lewinsky investigation to the Salem witch hunt. Miller had asserted a parallel between the examination of physical evidence on Lewinsky's dress and the examinations of women's bodies for signs of the "Devil's Marks" in Salem. Hitchens scathingly disputed the parallel.[100] In his memoir, Hitch-22, Hitchens bitterly noted that Miller, despite his prominence as a left-wing intellectual, had failed to support author Salman Rushdie during the Iranian fatwa involving The Satanic Verses.[101]

Works

[edit]Stage plays

[edit]- No Villain (1936)

- They Too Arise (1937, based on No Villain)

- Honors at Dawn (1938, based on They Too Arise)

- The Grass Still Grows (1938, based on They Too Arise)

- The Great Disobedience (1938)

- Listen My Children (1939, with Norman Rosten)

- The Golden Years (1940)

- The Half-Bridge (1943)

- The Man Who Had All the Luck (1944)[98]

- All My Sons (1947)

- Death of a Salesman (1949)

- An Enemy of the People (1950, adaptation of Henrik Ibsen's play An Enemy of the People)

- The Crucible (1953)

- A View from the Bridge (1955)

- A Memory of Two Mondays (1955)

- After the Fall (1964)

- Incident at Vichy (1964)

- The Price (1968)

- The Reason Why (1970)

- Fame (one-act, 1970; revised for television 1978)

- The Creation of the World and Other Business (1972)

- Up from Paradise (1974)

- The Archbishop's Ceiling (1977)

- The American Clock (1980)

- Playing for Time (television play, 1980)

- Elegy for a Lady (short play, 1982, first part of Two Way Mirror)

- Some Kind of Love Story (short play, 1982, second part of Two Way Mirror)

- I Think About You a Great Deal (1986)

- Playing for Time (stage version, 1985)

- I Can't Remember Anything (1987, collected in Danger: Memory!)

- Clara (1987, collected in Danger: Memory!)

- The Ride Down Mt. Morgan (1991)

- The Last Yankee (1993)

- Broken Glass (1994)

- Mr. Peters' Connections (1998)

- Resurrection Blues (2002)

- Finishing the Picture (2004)

Radio plays

[edit]- The Pussycat and the Expert Plumber Who Was a Man (1940)

- Joel Chandler Harris (1941)

- The Battle of the Ovens (1942)

- Thunder from the Mountains (1942)

- I Was Married in Bataan (1942)

- That They May Win (1943)

- Listen for the Sound of Wings (1943)

- Bernardine (1944)

- I Love You (1944)

- Grandpa and the Statue (1944)

- The Philippines Never Surrendered (1944)

- The Guardsman (1944, based on Ferenc Molnár's play)

- The Story of Gus (1947)

Screenplays

[edit]- The Hook (1947)

- All My Sons (1948)

- Let's Make Love (1960)

- The Misfits (1961)

- Death of a Salesman (1985)

- Everybody Wins (1990)

- The Crucible (1996)

Assorted fiction

[edit]- Focus (novel, 1945)

- "The Misfits" (short story, published in Esquire, October 1957)

- I Don't Need You Anymore (short stories, 1967)

- Homely Girl: A Life (short story, 1992, published in UK as "Plain Girl: A Life" 1995)

- Presence: Stories (2007) (short stories include "The Bare Manuscript", "Beavers", "The Performance", and "Bulldog")

Non-fiction

[edit]- Situation Normal (1944) is based on his experiences researching the war correspondence of Ernie Pyle.

- In Russia (1969), the first of three books created with his photographer wife Inge Morath, offers Miller's impressions of Russia and Russian society.

- In the Country (1977), with photographs by Morath and text by Miller, provides insight into how Miller spent his time in Roxbury, Connecticut, and profiles of his various neighbors.

- Chinese Encounters (1979) is a travel journal with photographs by Morath. It depicts the Chinese society in the state of flux which followed the end of the Cultural Revolution. Miller discusses the hardships of many writers, professors, and artists during Mao Zedong's regime.

- Salesman in Beijing (1984) details Miller's experiences with the 1983 Beijing People's Theatre production of Death of a Salesman. He describes directing a Chinese cast in an American play.

- Timebends: A Life, Methuen London (1987) ISBN 0-413-41480-9. Miller's autobiography.

- On Politics and the Art of Acting, Viking 2001 {ISBN 0-670-030-422} an 85-page essay about the thespian skills in American politics, comparing FDR, JFK, Reagan, Clinton.

Collections

[edit]- Abbotson, Susan C. W. (ed.), Arthur Miller: Collected Essays, Penguin 2016 ISBN 978-0-14-310849-8

- Kushner, Tony, ed. Arthur Miller, Collected Plays 1944–1961 (Library of America, 2006) ISBN 978-1-931082-91-4.

- Martin, Robert A. (ed.), "The theater essays of Arthur Miller", foreword by Arthur Miller. NY: Viking Press, 1978 ISBN 0-14-004903-7

References

[edit]- ^ "Website of St. Louis Literary Award". Archived from the original on August 23, 2016. Retrieved July 25, 2016.

- ^ Saint Louis University Library Associates. "Recipients of the Saint Louis Literary Award". Archived from the original on July 31, 2016. Retrieved July 25, 2016.

- ^ Associated Press, "Citing Arts' Power, Arthur Miller Accepts International Prize". Los Angeles Times, September 4, 2002

- ^ Ratcliffe, Michael (February 12, 2005). "Arthur Miller". The Guardian. Retrieved May 8, 2018.

- ^ Arthur Miller, Timebends: A Life, A&C Black, 2012. p. 539.

- ^ BBC TV Interview; Miller and Yentob; 'Finishing the Picture,' 2004

- ^ Miller, Arthur (June 22, 1998) American Summer: Before Air-Conditioning. The New Yorker. Retrieved on October 30, 2013.

- ^ a b Garner, Dwight (June 2, 2009). "Miller: Life before and after Marilyn". The New York Times. Retrieved December 18, 2011.

- ^ a b c d e f g h The Times Arthur Miller Obituary, (London: The Times, 2005)

- ^ Applebome, Peter. "Present at the Birth of a Salesman", The New York Times, January 29, 1999. Accessed February 8, 2019. "Mr. Miller was born in Harlem in 1915 and then moved with his family to the Midwood section of Brooklyn."

- ^ Hechinger, Fred M. "Personal Touch Helps", The New York Times, January 1, 1980. Accessed September 20, 2009. "Lincoln, an ordinary, unselective New York City high school, is proud of a galaxy of prominent alumni, who include the playwright Arthur Miller, Representative Elizabeth Holtzman, the authors Joseph Heller and Ken Auletta, the producer Mel Brooks, the singer Neil Diamond and the songwriter Neil Sedaka."

- ^ Page, Myra; Baker, Christina Looper (1996). In a Generous Spirit: A First-Person Biography of Myra Page. University of Illinois Press. p. 145. ISBN 9780252065439. Retrieved August 4, 2018.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k "A Brief Chronology of Arthur Miller's Life and Works". The Arthur Miller Society. Archived from the original on October 2, 2006. Retrieved September 24, 2006.

- ^ For Rowe's recollections of Miller's work as a student playwright, see Kenneth Thorpe Rowe, "Shadows Cast Before," in Robert A. Martin, ed. (1982) Arthur Miller: New Perspectives, Prentice-Hall, ISBN 0130488011. Rowe's influential book Write That Play (Funk and Wagnalls, 1939), which appeared just a year after Miller's graduation, describes Rowe's approach to play construction.

- ^ Arthur Miller, Timebends: A Life. New York: Grove Press, 1987, pp. 226–227

- ^ "Arthur Miller Files (UM days)". University of Michigan. Retrieved September 24, 2006.

- ^ "Arthur Miller and University of Michigan". University of Michigan. Archived from the original on September 13, 2006. Retrieved September 24, 2006.

- ^ Royal National Theater: Platform Papers, 7. Arthur Miller (Battley Brothers Printers, 1995).

- ^ Shenton, Mark (March 14, 2008). "The man who HAS all the luck..." The Stage. The Stage Newspaper Limited. Archived from the original on May 19, 2009. Retrieved May 6, 2009.

- ^ Bigsby, C. W. E. (2005). Arthur Miller: A Critical Study. Cambridge University Press. p. 301. ISBN 978-0-521-60553-3.

- ^ Rifkin, Ron, "Arthur Miller" Archived May 26, 2012, at the Wayback Machine. BOMB Magazine. Fall 1994. Retrieved on July 18, 2012.

- ^ a b "Obituary: Arthur Miller". BBC News. BBC. February 11, 2005. Retrieved September 21, 2010.

- ^ Dan Isaac, "Founding Father: O'Neill's Correspondence with Arthur Miller and Tennessee Williams", The Eugene O'Neill Review, Vol. 17, No. 1/2 (Spring/Fall 1993), pp. 124–133

- ^ Mills, Michael. "Postage Paid: In defense of Elia Kazan". moderntimes.com. Retrieved February 25, 2009.

- ^ a b "American Masters: Elia Kazan". PBS. September 3, 2003. Archived from the original on September 23, 2006. Retrieved September 22, 2006.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Ratcliffe, Michael (February 11, 2005). "Obituary: Arthur Miller". The Guardian. London. p. 25. Archived from the original on July 23, 2012. Retrieved July 23, 2012.

- ^ Sklar, Robert. "On The Waterfront" (PDF). Library of Congress. Archived (PDF) from the original on September 9, 2022. Retrieved December 27, 2018.

- ^ "The Untold Story of On the Waterfront – As Time Goes By". CampusPress. April 2, 2021. Retrieved September 3, 2024.

- ^ For a frequently cited study of Miller's use of the Salem witchcraft episode, see Robert A. Martin, "Arthur Miller's The Crucible: Background and Sources", reprinted in James J. Martine, ed. (1979) Critical Essays on Arthur Miller, G. K. Hall, ISBN 0816182582.

- ^ "Are you now, or were you ever?". University of Pennsylvania. Archived from the original on September 10, 2006. Retrieved September 25, 2006.

- ^ a b Çakırtaş, Önder. "Double Portrayed: Tituba, Racism and Politics". International Journal of Language Academy. Volume 1/1 Winter 2013, pp. 13–22.

- ^ Miller, Arthur (1988) Introduction to Plays: One, London: Methuen, p. 51, ISBN 0413175502.

- ^ Pecorari, Mario; Poppi, Roberto (2007). Dizionario del cinema italiano. I film (in Italian). Rome: Gremese Editore. ISBN 978-8884405036.

- ^ a b c d "BBC On This Day". BBC. August 7, 1958. Retrieved October 14, 2006.

- ^ Drury, Allen (June 22, 1956). "Arthur Miller Admits Helping Communist-Front Groups in '40's". The New York Times. Retrieved June 7, 2016.

- ^ Leaming, Barbara (1998). Marilyn Monroe: A Biography, pp. 231–233.

- ^ "Arthur Miller Files". University of Michigan. Retrieved April 2, 2016.

- ^ Barthel, Joan:A Death in Canaan. New York: E.P. Dutton. 1976

- ^ A Death in Canaan |url = https://www.imdb.com/title/tt0077412/

- ^ "A Son's Confession DVD, Shows The First 48, A&E Shop". shop.aetv.com. Archived from the original on January 16, 2013. Retrieved January 11, 2009.

- ^ Stowe, Stacey (September 3, 2004). "Records on Exonerated Man Are Kept Off Limits to Press". The New York Times. Retrieved January 11, 2009.

- ^ a b Celizic, Mike (June 2, 2008). "New footage of Marilyn Monroe, Clark Gable revealed". Today. Retrieved April 22, 2018.

- ^ Grobel, Lawrence. The Hustons, Charles Scribner's Sons, New York (1989) p. 489

- ^ "Marilyn Monroe is found dead". History. November 24, 2009. Retrieved September 2, 2020.

- ^ Badman, Keith. The Final Years of Marilyn Monroe: The Shocking True Story, Aurum Press (2010) ebook, ISBN 9781781310519

- ^ Schwartz, Stephen (February 28, 2005). "The Moral of Arthur Miller". The Weekly Standard. Archived from the original on January 7, 2015. Retrieved October 30, 2013.

- ^ Miller, Arthur (December 24, 2003). "A Visit With Castro". The Nation. Archived from the original on August 20, 2015. Retrieved August 1, 2006.

- ^ a b "Arthur Miller Files 60s70s80s". University of Michigan. Retrieved October 14, 2006.

- ^ Kurlansky, Mark (2004). 1968: The Year that Rocked the World (1st ed.). New York: Ballantine. p. 272. ISBN 0-345-45581-9. OCLC 53929433.

- ^ Mel Gussow (April 17, 1974). "Arthur Miller Returns to Genesis for First Musical". The New York Times. Retrieved January 11, 2009.

- ^ Rich, Frank (October 26, 1983). "Stage: Miller's Up from Paradise". The New York Times. p. C22. Retrieved January 11, 2009.

- ^ Martin, Robert A., ed. (1978). The Theater Essays of Arthur Miller. Viking. ISBN 0670698016.

- ^ Wilmeth, Don B.; Bigsby, Christopher, eds. (2006). The Cambridge History of American Theatre Volume III: Post-World War II to the 1990s. Cambridge University Press. p. 296. ISBN 978-0-521-67985-5.

- ^ "'Death of a Salesman' Takes Four Tony Awards". Los Angeles Times. June 7, 1999. Retrieved January 8, 2023.

- ^ "1993 Lifetime Honors". National Medal of Arts. Archived from the original on July 21, 2011. Retrieved December 18, 2011.

- ^ "Arthur Miller". National Endowment for the Humanities. Retrieved January 22, 2009.

- ^ Miller, Arthur (March 26, 2001). On Politics and the Art of Acting (Speech). National Endowment for the Humanities. Archived from the original on July 17, 2001.

- ^ Craig, Bruce (May 2001). "Arthur Miller's Jefferson Lecture Stirs Controversy". OAH Newsletter. Organization of American Historians. Archived from the original on December 22, 2001.

- ^ Nordlinger, Jay (April 22, 2002). "Back to Plessy, Easter with Fidel, Miller's new tale". National Review. Archived from the original on May 20, 2002.

- ^ Will, George (April 10, 2001). "Enduring Arthur Miller: Oh, the Humanities!". Jewish World Review.

- ^ McGrath, Sean (July 20, 1999). "Arthur Miller to Receive 1999 Dorothy and Lillian Gish Prize". Playbill. Retrieved January 18, 2023.

- ^ "Arthur Miller". The John Steinbeck Award. Retrieved October 29, 2024.

- ^ Miller, Arthur (2001). Acceptance Speech by Arthur Miller, Winner of the 2001 Distinguished Contribution to American Letters Award (Speech). National Book Foundation. Archived from the original on January 26, 2003.

- ^ Wrigg, William (January 12, 2003). "On Inge Morath's death". The New York Times Magazine. Retrieved January 21, 2007.

- ^ "At 89, Arthur Miller grows old romantically". The Daily Telegraph. December 11, 2004. Archived from the original on January 11, 2022. Retrieved September 3, 2014.

- ^ "Arthur Miller creates a new work". USA Today. Chicago. October 10, 2004. Retrieved September 23, 2014.

And in the play's sweetest moments, he's found a new romance – Kitty's tenderhearted secretary, played by Fisher, a union perhaps mirroring Miller's reported new relationship with Agnes Barley, a 34-year-old artist.

- ^ Solomon, Deborah (September 19, 2004). "Goodbye (Again), Norma Jean". The New York Times. Retrieved September 3, 2014.

- ^ Jones, Chris (February 12, 2005). "Arthur Miller (1915–2005) – The Shadow Of Marilyn Monroe. Decades later, a man still haunted". Chicago Tribune. Retrieved September 3, 2014.

- ^ Fried, Billy (April 9, 2022). "Remembering Bob Miller". Laguna Beach Independent. Firebrand Media. Retrieved August 13, 2022.

- ^ a b c d e Meyers, Jeffrey. The Genius and the Goddess: Arthur Miller and Marilyn Monroe. University of Illinois Press (2010) ISBN 978-0-252-03544-9

- ^ Monroe, Marilyn (2010). Fragments: Poems, Intimate Notes, Letters. New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux. pp. 89–101. ISBN 9780374158354.

- ^ Spoto, Donald (2001). Marilyn Monroe: The Biography. Cooper Square Press. pp. 450–455. ISBN 978-0-8154-1183-3.

- ^ Andrews, Suzanna (September 2007). "Arthur Miller's Missing Act". Vanity Fair. Retrieved August 17, 2007.

- ^ Joseph Epstein (November 29, 2011). Gossip: The Untrivial Pursuit. HMH. pp. 35–37. ISBN 9780547577210. Retrieved March 29, 2020.

- ^ Andrews, Suzanna (August 13, 2007). "Arthur Miller's Missing Act". Vanity Fair. Retrieved June 3, 2021.

- ^ Richard Christiansen (February 23, 2005). "Miller's last days reflected his life". Chicago Tribune.

- ^ "Playwright Arthur Miller dies at age 89 – THEATER". Today.com. Associated Press. February 11, 2005. Retrieved January 11, 2009.

- ^ Leonardin, Tom (February 12, 2005). "Dramatist's last hours spent in home he shared with star". Irish Independent. Retrieved December 18, 2011.

- ^ Leonard, Tom (February 18, 2005). "Miller's fiancée quits his home after ultimatum from family". The Daily Telegraph. Archived from the original on January 11, 2022. Retrieved February 21, 2013.

- ^ "Tributes to Arthur Miller". BBC. February 12, 2005. Retrieved November 9, 2006.

- ^ "Legacy of Arthur Miller". BBC. February 11, 2005. Retrieved January 21, 2007.

- ^ "Broadway lights go out for Arthur Miller". BBC. February 12, 2005. Retrieved November 9, 2006.

- ^ "U-M celebrates naming of Arthur Miller Theatre". University of Michigan. Archived from the original on December 11, 2007. Retrieved November 12, 2007.

- ^ "Theater Hall of Fame | The Official Website | Members | Preserve the Past • Honor the Present • Encourage the Future". theaterhalloffame.org.

- ^ "Theater Hall of Fame Enshrines 51 Artists" (PDF). The New York Times. Archived (PDF) from the original on October 9, 2022. Retrieved March 13, 2014.

- ^ "Four Freedoms Awards". Archived from the original on March 25, 2015. Retrieved April 4, 2015.

- ^ "Arthur Miller: Writer (2018)". Rotten Tomatoes.

- ^ Schmadel, Lutz D. (2006). (3769) Arthurmiller [2.26, 0.11, 4.7] In: Dictionary of Minor Planet Names. Springer. doi:10.1007/978-3-540-34361-5. ISBN 978-3-540-34361-5.

- ^ "'Blonde': 10 of the Marilyn Monroe Biopic's Stars and Their Real-Life Inspirations". The Hollywood Reporter. September 28, 2022. Retrieved August 6, 2023.

- ^ Arthur Miller Foundation, summary report and legitimacy information, guidestar.org

- ^ The Arthur Miller Foundation, arthurmillerfoundation.org

- ^ "Celebrating Arthur Miller's Centenary: An Events Guide". Archived from the original on October 11, 2015.

- ^ Media Room, Hasty Pudding Institute of 1770, hastypudding.org

- ^ "Arthur Miller: An Inventory of His Collection at the Harry Ransom Center". norman.hrc.utexas.edu. Retrieved January 10, 2018.

- ^ "Playwright Arthur Miller's archive comes to the Harry Ransom Center". sites.utexas.edu. Retrieved January 10, 2018.

- ^ Schuessler, Jennifer (2018). "Inside the Battle for Arthur Miller's Archive". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on January 1, 2022. Retrieved January 10, 2018.

- ^ "Playwright Arthur Miller's archive opens to researchers". sites.utexas.edu. Retrieved December 14, 2019.

- ^ a b c Alberge, Dalya (March 7, 2008). "Unseen writings show anti-racist passions of young Arthur Miller". The Times. London. Archived from the original on August 30, 2008. Retrieved March 7, 2008.

- ^ Wald, Alan M (2007). "7". Trinity of passion: the literary left and the antifascist crusade. NC: University of North Carolina Press. pp. 212–221. ISBN 978-0-8078-3075-8. Retrieved May 6, 2009.

- ^ Hitchens, Christopher (April 18, 1999). "Bill Clinton: Is He the Most Crooked President in History?". The Guardian. Retrieved February 14, 2020.

- ^ Hitchens, Christopher (January 5, 2009). "Christopher Hitchens on the cultural fatwa". Vanity Fair. Retrieved September 30, 2020.

Bibliography

[edit]- Bigsby, Christopher (ed.), The Cambridge Companion to Arthur Miller, Cambridge 1997 ISBN 0-521-55992-8

- Gottfried, Martin, Arthur Miller, A Life, Da Capo Press (US)/Faber and Faber (UK), 2003 ISBN 0-571-21946-2

- Koorey, Stefani, Arthur Miller's Life and Literature, Scarecrow, 2000 ISBN 978-0810838697

- Moss, Leonard. Arthur Miller, Boston: Twayne Publishers, 1980.

Further reading

[edit]- Critical Companion to Arthur Miller, Susan Greenwood (2007)

- Student Companion to Arthur Miller, Susan C. W. Abbotson, Facts on File (2000)

- File on Miller, Christopher Bigsby (1988)

- Arthur Miller & Company, Christopher Bigsby, editor (1990)

- Arthur Miller: A Critical Study, Christopher Bigsby (2005)

- Remembering Arthur Miller, Christopher Bigsby, editor (2005)

- Arthur Miller 1915–1962, Christopher Bigsby (2008, U.K.; 2009, U.S.)

- The Cambridge Companion to Arthur Miller (Cambridge Companions to Literature), Christopher Bigsby, editor (1998, updated and republished 2010)

- Arthur Miller 1962–2005, Christopher Bigsby (2011)

- Nelson, Benjamin (1970). Arthur Miller, Portrait of a Playwright. New York: McKay.

- Arthur Miller: Critical Insights, Brenda Murphy, editor, Salem (2011)

- Understanding Death of a Salesman, Brenda Murphy and Susan C. W. Abbotson, Greenwood (1999)

- Robert Willoughby Corrigan, ed. (1969). Arthur Miller: A Collection of Critical Essays. Englewood Cliffs, New Jersey: Prentice-Hall. ISBN 978-0135829738. OL 5683736M.

Critical articles

- Arthur Miller Journal, published biannually by Penn State UP. Vol. 1.1 (2006)

- Radavich, David. "Arthur Miller's Sojourn in the Heartland". American Drama 16:2 (Summer 2007): 28–45.

External links

[edit]This article's use of external links may not follow Wikipedia's policies or guidelines. (August 2018) |

Organizations

Archive

- Arthur Miller Papers at the Harry Ransom Center

- "Playwright Arthur Miller's archive comes to the Harry Ransom Center"

- Finding aid to Arthur Miller papers at Columbia University. Rare Book & Manuscript Library.

Databases

- Arthur Miller at the Internet Broadway Database

- Arthur Miller at the Internet Off-Broadway Database (archived)

- Arthur Miller at IMDb

Websites

- Arthur Miller at Find a Grave

- Appearances on C-SPAN

- A Visit With Castro – Miller's article in The Nation, January 12, 2004

- Works by Arthur Miller at Open Library

- Joyce Carol Oates on Arthur Miller

- Arthur Miller Biography

- Arthur Miller and Mccarthyism

Interviews

- Carlisle, Olga & Styron, Rose (Summer 1966). "Arthur Miller, The Art of Theater No. 2". The Paris Review Interview. Summer 1966 (38).

- Bigby, Christopher (Fall 1999). "Arthur Miller, The Art of Theater No. 2, Part 2". The Paris Review. Fall 1999 (152).

- Miller interview, Humanities, March–April 2001

Obituaries