Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Atomic physics

View on WikipediaThis article includes a list of general references, but it lacks sufficient corresponding inline citations. (September 2015) |

| Modern physics |

|---|

| |

Atomic physics is the field of physics that studies atoms as an isolated system of electrons and an atomic nucleus. Atomic physics typically refers to the study of atomic structure and the interaction between atoms.[1] It is primarily concerned with the way in which electrons are arranged around the nucleus and the processes by which these arrangements change. This comprises ions, neutral atoms and, unless otherwise stated, it can be assumed that the term atom includes ions.

The term atomic physics can be associated with nuclear power and nuclear weapons, due to the synonymous use of atomic and nuclear in standard English. Physicists distinguish between atomic physics—which deals with the atom as a system consisting of a nucleus and electrons—and nuclear physics, which studies nuclear reactions and special properties of atomic nuclei.

As with many scientific fields, strict delineation can be highly contrived and atomic physics is often considered in the wider context of atomic, molecular, and optical physics. As a result, atomic physics research groups are usually classified as such.

Isolated atoms

[edit]Atomic physics primarily considers atoms in isolation. Atomic models will consist of a single nucleus that may be surrounded by one or more bound electrons. It is not concerned with the formation of molecules (although much of the physics is identical), nor does it examine atoms in a solid state as condensed matter. It is concerned with processes such as ionization and excitation by photons or collisions with atomic particles.

While modelling atoms in isolation may not seem realistic, if one considers atoms in a gas or plasma then the time-scales for atom-atom interactions are huge in comparison to the atomic processes that are generally considered. This means that the individual atoms can be treated as if each were in isolation, as the vast majority of the time they are. By this consideration, atomic physics provides the underlying theory in plasma physics and atmospheric physics, even though both deal with very large numbers of atoms.

Electronic configuration

[edit]Electrons form notional shells around the nucleus. These are normally in a ground state but can be excited by the absorption of energy from light (photons), magnetic fields, or interaction with a colliding particle (typically ions or other electrons).

Electrons that populate a shell are said to be in a bound state. The energy necessary to remove an electron from its shell (taking it to infinity) is called the binding energy. Any quantity of energy absorbed by the electron in excess of this amount is converted to kinetic energy according to the conservation of energy. The atom is said to have undergone the process of ionization.

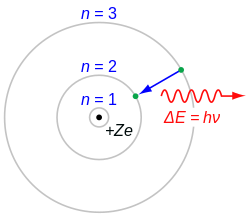

If the electron absorbs a quantity of energy less than the binding energy, it will be transferred to an excited state. After a certain time, the electron in an excited state will "jump" (undergo a transition) to a lower state. In a neutral atom, the system will emit a photon of the difference in energy, since energy is conserved.

If an inner electron has absorbed more than the binding energy (so that the atom ionizes), then a more outer electron may undergo a transition to fill the inner orbital. In this case, a visible photon or a characteristic X-ray is emitted, or a phenomenon known as the Auger effect may take place, where the released energy is transferred to another bound electron, causing it to go into the continuum. The Auger effect allows one to multiply ionize an atom with a single photon.

There are rather strict selection rules as to the electronic configurations that can be reached by excitation by light –however, there are no such rules for excitation by collision processes.

Bohr model of the atom

[edit]The Bohr model, proposed by Niels Bohr in 1913, is a revolutionary theory describing the structure of the hydrogen atom. It introduced the idea of quantized orbits for electrons, combining classical and quantum physics.

- Key Postulates of the Bohr Model

- Electrons Move in Circular Orbits

- Electrons revolve around the nucleus in fixed, circular paths called orbits or energy levels.

- These orbits are stable and do not radiate energy.

- Quantization of Angular Momentum:

- The angular momentum of an electron is quantized and given by: where:

- : electron mass

- : velocity of the electron

- : radius of the orbit

- : reduced Planck constant ()

- : principal quantum number, representing the orbit

- The angular momentum of an electron is quantized and given by: where:

- Energy Levels

- Each orbit has a specific energy. The total energy of an electron in the th orbit is: where is the ground-state energy of the hydrogen atom.

- Emission or Absorption of Energy

- Electrons can transition between orbits by absorbing or emitting energy equal to the difference between the energy levels: where:

- : the Planck constant.

- : frequency of emitted/absorbed radiation.

- : final and initial energy levels.

- Electrons can transition between orbits by absorbing or emitting energy equal to the difference between the energy levels: where:

History and developments

[edit]One of the earliest steps towards atomic physics was the recognition that matter was composed of atoms. It forms a part of the texts written in 6th century BC to 2nd century BC, such as those of Democritus or Vaiśeṣika Sūtra written by Kaṇāda.[2][3] This theory was later developed in the modern sense of the basic unit of a chemical element by the British chemist and physicist John Dalton in the 18th century.[4] At this stage, it was not clear what atoms were, although they could be described and classified by their properties (in bulk). The invention of the periodic system of elements by Dmitri Mendeleev was another great step forward.

The true beginning of atomic physics is marked by the discovery of spectral lines and attempts to describe the phenomenon, most notably by Joseph von Fraunhofer.[5] The study of these lines led to the Bohr atom model and to the birth of quantum mechanics. In seeking to explain atomic spectra, an entirely new mathematical model of matter was revealed. As far as atoms and their electron shells were concerned, not only did this yield a better overall description, i.e. the atomic orbital model, but it also provided a new theoretical basis for chemistry (quantum chemistry) and spectroscopy.[6]

Since the Second World War, both theoretical and experimental fields have advanced at a rapid pace. This can be attributed to progress in computing technology, which has allowed larger and more sophisticated models of atomic structure and associated collision processes.[7][8] Similar technological advances in accelerators, detectors, magnetic field generation and lasers have greatly assisted experimental work.

Beyond the well-known phenomena which can be described with regular quantum mechanics chaotic processes[9] can occur which need different descriptions.

Significant atomic physicists

[edit]- Pre quantum mechanics

- John Dalton

- Joseph von Fraunhofer

- Johannes Rydberg

- J. J. Thomson

- Ernest Rutherford

- Democritus

- Vaiśeṣika Sūtra

- Post quantum mechanics

- Alexander Dalgarno

- David Bates

- Niels Bohr

- Max Born

- Clinton Joseph Davisson

- Paul A. M. Dirac

- Enrico Fermi

- Charlotte Froese Fischer

- Vladimir Fock

- Douglas Hartree

- Ernest M. Henley

- Ratko Janev

- Daniel Kleppner

- Harrie S. Massey

- Nevill Mott

- I. I. Rabi

- Norman Ramsey

- Mike Seaton

- John C. Slater

- George Paget Thomson

See also

[edit]Bibliography

[edit]- Will Raven (2025). Atomic Physics for Everyone. Springer Nature. doi:10.1007/978-3-031-69507-0. ISBN 978-3-031-69507-0.

- Sommerfeld, A. (1923) Atomic structure and spectral lines. (translated from German "Atombau und Spektrallinien" 1921), Dutton Publisher.

- Foot, CJ (2004). Atomic Physics. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-850696-6.

- Smirnov, B.E. (2003) Physics of Atoms and Ions, Springer. ISBN 0-387-95550-X.

- Szász, L. (1992) The Electronic Structure of Atoms, John Willey & Sons. ISBN 0-471-54280-6.

- Herzberg, Gerhard (1979) [1945]. Atomic Spectra and Atomic Structure. New York: Dover. ISBN 978-0-486-60115-1.

- Bethe, H.A. & Salpeter E.E. (1957) Quantum Mechanics of One- and Two Electron Atoms. Springer.

- Born, M. (1937) Atomic Physics. Blackie & Son Limited.

- Cox, P.A. (1996) Introduction to Quantum Theory and Atomic Spectra. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-855916

- Condon, E.U. & Shortley, G.H. (1935). The Theory of Atomic Spectra. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-09209-8.

{{cite book}}: ISBN / Date incompatibility (help) - Cowan, Robert D. (1981). The Theory of Atomic Structure and Spectra. University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-03821-9.

- Lindgren, I. & Morrison, J. (1986). Atomic Many-Body Theory (Second ed.). Springer-Verlag. ISBN 978-0-387-16649-0.

References

[edit]- ^ Demtröder, W. (2006). Atoms, molecules and photons : an introduction to atomic-, molecular-, and quantum-physics. Berlin: Springer. ISBN 978-3-540-32346-4. OCLC 262692011.

- ^ Pullman, Bernard; Pullman, Bernard (2001). The atom in the history of human thought. Oxford: Oxford Univ. Press. ISBN 978-0-19-515040-7.

- ^ Kanada; Sankara Misra; Chandrakanta Tarakalankara; Jayanarayana Tarkapanchanana (1923). The Vaisesika sutras of Kanada. Translated by Nandalal Sinha. Robarts - University of Toronto. Allahabad Panini Office.

- ^ Dalton, John (2010-09-16). A New System of Chemical Philosophy. Cambridge University Press. doi:10.1017/cbo9780511736407. ISBN 978-1-108-01968-2.

- ^ Brand, John C. D. (1995). Lines of light: the sources of dispersive spectroscopy, 1800 - 1930. Luxembourg: Gordon and Breach Publ. ISBN 978-2-88449-162-4.

- ^ Svanberg, S. (2004). Atomic and Molecular Spectroscopy. Springer. ISBN 3-540-20382-6.

- ^ Bell, K.L.; Berrington, K.A.; Crothers, D.S.F.; Hilbert, A.; Taylor, K. (2002). Supercomputing, Collision Processes, and Applications. Springer. ISBN 0-306-46190-0.

- ^ Amusia, M. Ya.; Chernysheva, L.V. (1997). Computation of Atomic Processes. Institute of Physics Publishing. ISBN 0-7503-0229-1.

- ^ Blümel, R.; Reinhardt, W.P (1997). Chaos in Atomic Physics. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-45502-2.

External links

[edit]Atomic physics

View on GrokipediaFundamentals

Definition and Scope

Atomic physics is the branch of physics dedicated to the study of the structure, properties, and interactions of atoms, with a primary focus on electrons bound to the atomic nucleus. This field examines atoms as isolated systems, investigating phenomena such as electron-nuclear interactions and the quantum states of atomic electrons. It deliberately excludes in-depth analyses of molecular formations, where interatomic bonds dominate, and nuclear physics, which concerns the nucleus's internal composition and strong force interactions.[8][9] A key aspect of atomic physics is its role as a foundational testing ground for quantum mechanics, where theoretical frameworks can be rigorously tested against experimental observations. The hydrogen atom, consisting of a single proton and electron, exemplifies this simplicity, enabling exact solutions to the Schrödinger equation and providing benchmarks for quantum theory's predictions on energy levels and wave functions.[10][11] Central questions driving atomic physics research include the mechanisms by which atoms emit and absorb light—manifesting as discrete spectral lines from electronic transitions between quantized energy levels—and the stability of electron orbits or configurations that prevent classical collapse into the nucleus. Additionally, the field elucidates the atomic basis of matter's composition, revealing how elemental building blocks determine the chemical and physical properties of substances.[12][13][8]Basic Components of Atoms

Atoms are composed of three fundamental subatomic particles: protons, neutrons, and electrons. The nucleus at the center of the atom contains protons and neutrons, which together account for nearly all of the atom's mass. Protons carry a positive electric charge of +1 elementary charge (e = 1.602 176 634 × 10⁻¹⁹ C) and have a mass of approximately 1.007 276 u (unified atomic mass units), where 1 u = 1.660 539 066 60 × 10⁻²⁷ kg.[14] Neutrons are electrically neutral and have a slightly larger mass of about 1.008 665 u.[14] Surrounding the nucleus is a cloud of electrons, each with a negative charge of -1 e and a much smaller mass of roughly 0.000 549 u, or about 1/1836 that of a proton.[14] The following table summarizes the key properties of these particles:| Particle | Charge | Mass (u) | Location |

|---|---|---|---|

| Proton | +1 e | 1.007 276 | Nucleus |

| Neutron | 0 | 1.008 665 | Nucleus |

| Electron | -1 e | 0.000 549 | Electron cloud |