Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Neuroimaging

View on Wikipedia| Neuroimaging | |

|---|---|

Para-sagittal MRI of the head in a patient with benign familial macrocephaly | |

| Purpose | Indirectly (directly) image structure, function/pharmacology of the nervous system |

Neuroimaging is the use of quantitative (computational) techniques to study the structure and function of the central nervous system, developed as an objective way of scientifically studying the healthy human brain in a non-invasive manner. Increasingly it is also being used for quantitative research studies of brain disease and psychiatric illness. Neuroimaging is highly multidisciplinary involving neuroscience, computer science, psychology and statistics, and is not a medical specialty. Neuroimaging is sometimes confused with neuroradiology.

Neuroradiology is a medical specialty that uses non-statistical brain imaging in a clinical setting, practiced by radiologists who are medical practitioners. Neuroradiology primarily focuses on recognizing brain lesions, such as vascular diseases, strokes, tumors, and inflammatory diseases. In contrast to neuroimaging, neuroradiology is qualitative (based on subjective impressions and extensive clinical training) but sometimes uses basic quantitative methods. Functional brain imaging techniques, such as functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI), are common in neuroimaging but rarely used in neuroradiology. Neuroimaging falls into two broad categories:

- Structural imaging, which is used to quantify brain structure using e.g., voxel-based morphometry.

- Functional imaging, which is used to study brain function, often using fMRI and other techniques such as PET and MEG (see below).

History

[edit]

The first chapter of the history of neuroimaging traces back to the Italian neuroscientist Angelo Mosso who invented the 'human circulation balance', which could non-invasively measure the redistribution of blood during emotional and intellectual activity.[1]

In 1918, the American neurosurgeon Walter Dandy introduced the technique of ventriculography. X-ray images of the ventricular system within the brain were obtained by injection of filtered air directly into one or both lateral ventricles of the brain. Dandy also observed that air introduced into the subarachnoid space via lumbar spinal puncture could enter the cerebral ventricles and also demonstrate the cerebrospinal fluid compartments around the base of the brain and over its surface. This technique was called pneumoencephalography.[citation needed]

In 1927, Egas Moniz introduced cerebral angiography, whereby both normal and abnormal blood vessels in and around the brain could be visualized with great precision. [citation needed]

In the early 1970s, Allan McLeod Cormack and Godfrey Newbold Hounsfield introduced computerized axial tomography (CAT or CT scanning), and ever more detailed anatomic images of the brain became available for diagnostic and research purposes. Cormack and Hounsfield won the 1979 Nobel Prize for Physiology or Medicine for their work. Soon after the introduction of CAT in the early 1980s, the development of radioligands allowed single-photon emission computed tomography (SPECT) and positron emission tomography (PET) of the brain.[citation needed]

More or less concurrently, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI or MR scanning) was developed by researchers including Peter Mansfield and Paul Lauterbur, who were awarded the Nobel Prize for Physiology or Medicine in 2003. In the early 1980s MRI was introduced clinically, and during the 1980s a veritable explosion of technical refinements and diagnostic MR applications took place. Scientists soon learned that the large blood flow changes measured by PET could also be imaged by the correct type of MRI. Functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) was born, and since the 1990s, fMRI has come to dominate the brain mapping field due to its low invasiveness, lack of radiation exposure, and relatively wide availability.[citation needed]

In the early 2000s, the field of neuroimaging reached the stage where limited practical applications of functional brain imaging have become feasible. The main application area is crude forms of brain–computer interface.[citation needed]

The world record for the spatial resolution of a whole-brain MRI image was a 100-micrometer volume (image) achieved in 2019. The sample acquisition took about 100 hours.[2] The spatial world record of a whole human brain of any method was an X-ray tomography scan performing at the ESRF (European synchrotron radiation facility), which had a resolution of about 25 microns and requiring about 22 hours. This scan was part of the human organ atlas which has X-ray tomography scans of other organs in the human body with the same resolution.[3][4]

A crucial idea for magnetic resonance imaging is that the net magnetization vector can be moved by exposing the spin system to energy of a frequency equal to the energy difference between the spin states (e.g., by a radio frequency pulse). If enough energy is delivered to the system, it is possible to make the net magnetization vector orthogonal to that of the external magnetic field.[citation needed]

Indications

[edit]Neuroradiology often follows a neurological examination in which a physician has found cause to more deeply investigate a patient who has or may have a neurological disorder.[citation needed]

Common clinical indications for neuroimaging include head trauma, stroke like symptoms e.g.: sudden weakness/numbness in one half of body, difficulty talking or walking; seizures, sudden onset severe headache, sudden change in level of consciousness for unclear reasons.[citation needed]

Another indication for neuroradiology is CT-, MRI- and PET-guided stereotactic surgery or radiosurgery for treatment of intracranial tumors, arteriovenous malformations and other surgically treatable conditions.[5][6][7]

One of the more common neurological problems which a person may experience is simple syncope.[8][9] In cases of simple syncope in which the patient's history does not suggest other neurological symptoms, the diagnosis includes a neurological examination but routine neurological imaging is not indicated because the likelihood of finding a cause in the central nervous system is extremely low and the patient is unlikely to benefit from the procedure.[9]

Neuroradiology is not indicated for patients with stable headaches which are diagnosed as migraine.[10] Studies indicate that presence of migraine does not increase a patient's risk for intracranial disease.[10] A diagnosis of migraine which notes the absence of other problems, such as papilledema, would not indicate a need for radiological investigations.[10] In the course of conducting a careful diagnosis, the physician should consider whether the headache has a cause other than the migraine and might require radiological investigations.[10][11]

Brain-imaging techniques

[edit]Computed axial tomography

[edit]Computed tomography (CT) or Computed Axial Tomography (CAT) scanning uses a series of x-rays of the head taken from many different directions. Typically used for quickly viewing brain injuries, CT scanning uses a computer program that performs a numerical integral calculation (the inverse Radon transform) on the measured x-ray series to estimate how much of an x-ray beam is absorbed in a small volume of the brain. Typically the information is presented as cross-sections of the brain.[12]

Magnetic resonance imaging

[edit]

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) uses magnetic fields and radio waves to produce high quality two- or three-dimensional images of brain structures without the use of ionizing radiation (X-rays) or radioactive tracers.[citation needed]

The record for the highest spatial resolution of a whole intact brain (postmortem) is 100 microns, from Massachusetts General Hospital. The data was published in Scientific Data on 30 October 2019.[13]

Positron emission tomography

[edit]Positron emission tomography (PET) and brain positron emission tomography, measure emissions from radioactively labeled metabolically active chemicals that have been injected into the bloodstream. The emission data are computer-processed to produce 2- or 3-dimensional images of the distribution of the chemicals throughout the brain.[14]: 57 The positron emitting radioisotopes used are produced by a cyclotron, and chemicals are labeled with these radioactive atoms. The labeled compound, called a radiotracer, is injected into the bloodstream and eventually makes its way to the brain. Sensors in the PET scanner detect the radioactivity as the compound accumulates in various regions of the brain. A computer uses the data gathered by the sensors to create multicolored 2- or 3-dimensional images that show where the compound acts in the brain. Especially useful are a wide array of ligands used to map different aspects of neurotransmitter activity, with by far the most commonly used PET tracer being a labeled form of glucose (see Fludeoxyglucose (18F) (FDG)).[citation needed]

The greatest benefit of PET scanning is that different compounds can show blood flow and oxygen and glucose metabolism in the tissues of the working brain. These measurements reflect the amount of brain activity in the various regions of the brain and allow to learn more about how the brain works. PET scans were superior to all other metabolic imaging methods in terms of resolution and speed of completion (as little as 30 seconds) when they first became available. The improved resolution permitted better study to be made as to the area of the brain activated by a particular task. The biggest drawback of PET scanning is that because the radioactivity decays rapidly, it is limited to monitoring short tasks.[14]: 60 Before fMRI technology came online, PET scanning was the preferred method of functional (as opposed to structural) brain imaging, and it continues to make large contributions to neuroscience.[citation needed]

PET scanning is also used for diagnosis of brain disease, most notably brain tumors, epilepsy, and neuron-damaging diseases which cause dementia (such as Alzheimer's disease) all cause great changes in brain metabolism, which in turn causes easily detectable changes in PET scans. PET is probably most useful in early cases of certain dementias (with classic examples being Alzheimer's disease and Pick's disease) where the early damage is too diffuse and makes too little difference in brain volume and gross structure to change CT and standard MRI images enough to be able to reliably differentiate it from the "normal" range of cortical atrophy which occurs with aging (in many but not all) persons, and which does not cause clinical dementia.[citation needed]

FDG-PET scanning is also often used in assessment of patients with epilepsy who continue to have seizures despite adequate medical treatment. In focal epilepsy, where seizures begin in a small part of the brain before spreading elsewhere, it is one of the many modalities used to identify the region of brain responsible for seizure onset. Typically, the area of brain where seizures begin is dysfunctional even when patient is not having a seizure and uptakes less glucose, hence less FDG compared to healthy brain regions.[15] This information can help plan for epilepsy surgery as a treatment for drug resistant epilepsy.[citation needed]

Other radiotracers have also been used to identify areas of seizure onset though they are not available commercially for clinical use. These include 11C-flumazenil, 11C-alpha-methyl-L-tryptophan, 11C-methionine, 11C-cerfentanil.[15]

Single-photon emission computed tomography

[edit]Single-photon emission computed tomography (SPECT) is similar to PET and uses gamma ray-emitting radioisotopes and a gamma camera to record data that a computer uses to construct two- or three-dimensional images of active brain regions.[16] SPECT relies on an injection of radioactive tracer, or "SPECT agent," which is rapidly taken up by the brain but does not redistribute. Uptake of SPECT agent is nearly 100% complete within 30 to 60 seconds, reflecting cerebral blood flow (CBF) at the time of injection. These properties of SPECT make it particularly well-suited for epilepsy imaging, which is usually made difficult by problems with patient movement and variable seizure types. SPECT provides a "snapshot" of cerebral blood flow since scans can be acquired after seizure termination (so long as the radioactive tracer was injected at the time of the seizure). A significant limitation of SPECT is its poor resolution (about 1 cm) compared to that of MRI. Today, SPECT machines with Dual Detector Heads are commonly used, although Triple Detector Head machines are available in the marketplace. Tomographic reconstruction, (mainly used for functional "snapshots" of the brain) requires multiple projections from Detector Heads which rotate around the human skull, so some researchers have developed 6 and 11 Detector Head SPECT machines to cut imaging time and give higher resolution.[17][18]

Like PET, SPECT also can be used to differentiate different kinds of disease processes which produce dementia, and it is increasingly used for this purpose. SPECT scan using Isoflupane labeled with I-123 (also called DaT scan) is useful in differentiating Parkinson's disease from other causes of tremor.[19]

SPECT scan is also used in evaluation of drug resistant epilepsy. This uses Tc99 labeled hexamethyl-propylene amine oxime (Tc99HMPAO) or ethyl cysteinate dimer ( Tc99 ECD) as the tracers. The radiotracer is injected into the patient's vein as soon as the start of a seizure is detected and scanning is done within few hours after the seizure is over. This technique is called ictal SPECT and relies on the increased CBF in areas of seizure onset during the seizure. Interictal SPECT is a scan done using the same tracers but during a time when the patient is not having a seizure. In between seizures, a reduction in CBF is seen in areas of seizure onset and is not as pronounced as the blood flow increase during the seizure.[20]

Cranial ultrasound

[edit]Cranial ultrasound is usually only used in babies, whose open fontanelles provide acoustic windows allowing ultrasound imaging of the brain. Advantages include the absence of ionising radiation and the possibility of bedside scanning, but the lack of soft-tissue detail means MRI is preferred for some conditions.

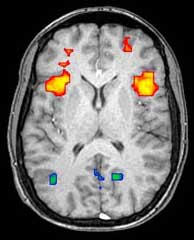

Functional magnetic resonance imaging

[edit]

Functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) and arterial spin labeling (ASL) relies on the paramagnetic properties of oxygenated and deoxygenated hemoglobin to see images of changing blood flow in the brain associated with neural activity. This allows images to be generated that reflect which brain structures are activated (and how) during the performance of different tasks or at resting state. According to the oxygenation hypothesis, changes in oxygen usage in regional cerebral blood flow during cognitive or behavioral activity can be associated with the regional neurons as being directly related to the cognitive or behavioral tasks being attended.

Most fMRI scanners allow subjects to be presented with different visual images, sounds and touch stimuli, and to make different actions such as pressing a button or moving a joystick. Consequently, fMRI can be used to reveal brain structures and processes associated with perception, thought and action. The resolution of fMRI is about 2-3 millimeters at present, limited by the spatial spread of the hemodynamic response to neural activity. It has largely superseded PET for the study of brain activation patterns. PET, however, retains the significant advantage of being able to identify specific brain receptors (or transporters) associated with particular neurotransmitters through its ability to image radiolabeled receptor "ligands" (receptor ligands are any chemicals that stick to receptors). There is also significant concern regarding the validity of some of the statistics used in fMRI analyses; hence, the validity of conclusions drawn from many fMRI studies.[22]

With between 72% and 90% accuracy where chance would achieve 0.8%,[23] fMRI techniques can decide which of a set of known images the subject is viewing.[24]

Recent studies on machine learning in psychiatry have used fMRI to build machine learning models that can discriminate between individuals with or without suicidal behaviour. Imaging studies in conjunction with machine learning algorithms may help identify new markers in neuroimaging that could allow stratification based on patients' suicide risk and help develop the best therapies and treatments for individual patients.[25]

Diffuse optical imaging

[edit]Diffuse optical imaging (DOI) or diffuse optical tomography (DOT) is a medical imaging modality which uses near infrared light to generate images of the body. The technique measures the optical absorption of haemoglobin, and relies on the absorption spectrum of haemoglobin varying with its oxygenation status. High-density diffuse optical tomography (HD-DOT) has been compared directly to fMRI using response to visual stimulation in subjects studied with both techniques, with reassuringly similar results.[26] HD-DOT has also been compared to fMRI in terms of language tasks and resting state functional connectivity.[27]

Event-related optical signal

[edit]Event-related optical signal (EROS) is a brain-scanning technique which uses infrared light through optical fibers to measure changes in optical properties of active areas of the cerebral cortex. Whereas techniques such as diffuse optical imaging (DOT) and near-infrared spectroscopy (NIRS) measure optical absorption of haemoglobin, and thus are based on blood flow, EROS takes advantage of the scattering properties of the neurons themselves and thus provides a much more direct measure of cellular activity. EROS can pinpoint activity in the brain within millimeters (spatially) and within milliseconds (temporally). Its biggest downside is the inability to detect activity more than a few centimeters deep. EROS is a new, relatively inexpensive technique that is non-invasive to the test subject. It was developed at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign where it is now used in the Cognitive Neuroimaging Laboratory of Dr. Gabriele Gratton and Dr. Monica Fabiani.[citation needed]

Magnetoencephalography

[edit]Magnetoencephalography (MEG) is an imaging technique used to measure the magnetic fields produced by electrical activity in the brain via extremely sensitive devices such as superconducting quantum interference devices (SQUIDs) or spin exchange relaxation-free[28] (SERF) magnetometers. MEG offers a very direct measurement of neural electrical activity (compared to fMRI for example) with very high temporal resolution but relatively low spatial resolution. The advantage of measuring the magnetic fields produced by neural activity is that they are likely to be less distorted by surrounding tissue (particularly the skull and scalp) compared to the electric fields measured by electroencephalography (EEG). Specifically, it can be shown that magnetic fields produced by electrical activity are not affected by the surrounding head tissue, when the head is modeled as a set of concentric spherical shells, each being an isotropic homogeneous conductor. Real heads are non-spherical and have largely anisotropic conductivities (particularly white matter and skull). While skull anisotropy has a negligible effect on MEG (unlike EEG), white matter anisotropy strongly affects MEG measurements for radial and deep sources.[29] Note, however, that the skull was assumed to be uniformly anisotropic in this study, which is not true for a real head: the absolute and relative thicknesses of diploë and tables layers vary among and within the skull bones. This makes it likely that MEG is also affected by the skull anisotropy,[30] although probably not to the same degree as EEG.

There are many uses for MEG, including assisting surgeons in localizing a pathology, assisting researchers in determining the function of various parts of the brain, neurofeedback, and others.[citation needed]

Functional ultrasound imaging

[edit]Functional ultrasound imaging (fUS) is a medical ultrasound imaging technique of detecting or measuring changes in neural activities or metabolism, for example, the loci of brain activity, typically through measuring blood flow or hemodynamic changes. Functional ultrasound relies on Ultrasensitive Doppler and ultrafast ultrasound imaging which allows high sensitivity blood flow imaging.[citation needed]

Quantum optically-pumped magnetometer

[edit]In June 2021, researchers reported the development of the first modular quantum brain scanner which uses magnetic imaging and could become a novel whole-brain scanning approach.[31][32]

Advantages and concerns of neuroimaging techniques

[edit]Functional Magnetic Resonance Imaging (fMRI)

[edit]fMRI is commonly classified as a minimally-to-moderate risk due to its non-invasiveness compared to other imaging methods. fMRI uses blood oxygenation level dependent (BOLD)-contrast in order to produce its form of imaging. BOLD-contrast is a naturally occurring process in the body so fMRI is often preferred over imaging methods that require radioactive markers to produce similar imaging.[33] A concern in the use of fMRI is its use in individuals with medical implants or devices and metallic items in the body. The magnetic resonance (MR) emitted from the equipment can cause failure of medical devices and attract metallic objects in the body if not properly screened for. Currently, the FDA classifies medical implants and devices into three categories, depending on MR-compatibility: MR-safe (safe in all MR environments), MR-unsafe (unsafe in any MR environment), and MR-conditional (MR-compatible in certain environments, requiring further information).[34]

- FDA MR safety labels for implants and devices

-

MR Safe[35]

-

MR Conditional

-

MR Unsafe

Computed Tomography (CT) scan

[edit]The CT scan was introduced in the 1970s and quickly became one of the most widely used methods of imaging. A CT scan can be performed in under a second and produce rapid results for clinicians, with its ease of use leading to an increase in CT scans performed in the United States from 3 million in 1980 to 62 million in 2007. Clinicians oftentimes take multiple scans, with 30% of individuals undergoing at least 3 scans in one study of CT scan usage.[36] CT scans can expose patients to levels of radiation 100-500 times higher than traditional x-rays, with higher radiation doses producing better resolution imaging.[37] While easy to use, increases in CT scan use, especially in asymptomatic patients, is a topic of concern since patients are exposed to significantly high levels of radiation.[36]

Positron Emission Tomography (PET)

[edit]In PET scans, imaging does not rely on intrinsic biological processes, but relies on a foreign substance injected into the bloodstream traveling to the brain. Patients are injected with radioisotopes that are metabolized in the brain and emit positrons to produce a visualization of brain activity.[33] The amount of radiation a patient is exposed to in a PET scan is relatively small, comparable to the amount of environmental radiation an individual is exposed to across a year. PET radioisotopes have limited exposure time in the body as they commonly have very short half-lives (~2 hours) and decay rapidly.[38] Currently, fMRI is a preferred method of imaging brain activity compared to PET, since it does not involve radiation, has a higher temporal resolution than PET, and is more readily available in most medical settings.[33]

Magnetoencephalography (MEG) and Electroencephalography (EEG)

[edit]The high temporal resolution of MEG and EEG allow these methods to measure brain activity down to the millisecond. Both MEG and EEG do not require exposure of the patient to radiation to function. EEG electrodes detect electrical signals produced by neurons to measure brain activity and MEG uses oscillations in the magnetic field produced by these electrical currents to measure activity. A barrier in the widespread usage of MEG is due to pricing, as MEG systems can cost millions of dollars. EEG is a much more widely used method to achieve such temporal resolution as EEG systems cost much less than MEG systems. A disadvantage of EEG and MEG is that both methods have poor spatial resolution when compared to fMRI.[33]

See also

[edit]- Brain mapping – Set of neuroscience techniques

- Outline of brain mapping – Overview of and topical guide to brain mapping

- Connectogram – Graphical representations of connectomics

- Functional integration (neurobiology) – Study of cooperation of brain regions to process information

- Functional near-infrared spectroscopy – Optical technique for monitoring brain activity

- History of neuroimaging

- Human brain – Central organ of the human nervous system

- Cognitive neuroscience – Scientific field

- Outline of the human brain – Overview of and topical guide to the human brain

- List of neuroimaging software

- List of neuroscience databases

- Magnetic resonance imaging – Medical imaging technique

- Magnetoencephalography – Mapping brain activity by recording magnetic fields produced by currents in the brain

- Medical image computing – Interdisciplinary field

- Medical imaging – Technique and process of creating visual representations of the interior of a body

- Neuroimaging journals

- Statistical parametric mapping – Statistical technique

- Transcranial magnetic stimulation – Brain stimulation using magnetic fields

- Voxel-based morphometry – Computational neuroanatomy method

References

[edit]- ^ Sandrone S, Bacigaluppi M, Galloni MR, Martino G (November 2012). "Angelo Mosso (1846-1910)". Journal of Neurology. 259 (11): 2513–4. doi:10.1007/s00415-012-6632-1. hdl:2318/140004. PMID 23010944. S2CID 13365830.

- ^ "100-Hour-Long MRI of Human Brain Produces Most Detailed 3D Images Yet". 10 July 2019.

- ^ "World's brightest x-rays reveal COVID-19's damage to the body". National Geographic Society. 26 January 2022. Archived from the original on January 26, 2022.

- ^ "Human Organ Atlas".

- ^ Thomas DG, Anderson RE, du Boulay GH (January 1984). "CT-guided stereotactic neurosurgery: experience in 24 cases with a new stereotactic system". Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery, and Psychiatry. 47 (1): 9–16. doi:10.1136/jnnp.47.1.9. PMC 1027634. PMID 6363629.

- ^ Heilbrun MP, Sunderland PM, McDonald PR, Wells TH, Cosman E, Ganz E (1987). "Brown-Roberts-Wells stereotactic frame modifications to accomplish magnetic resonance imaging guidance in three planes". Applied Neurophysiology. 50 (1–6): 143–52. doi:10.1159/000100700. PMID 3329837.

- ^ Leksell L, Leksell D, Schwebel J (January 1985). "Stereotaxis and nuclear magnetic resonance". Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery, and Psychiatry. 48 (1): 14–8. doi:10.1136/jnnp.48.1.14. PMC 1028176. PMID 3882889.

- ^ Miller TH, Kruse JE (October 2005). "Evaluation of syncope". American Family Physician. 72 (8): 1492–500. PMID 16273816.

- ^ a b American College of Physicians (September 2013), "Five Things Physicians and Patients Should Question", Choosing Wisely: an initiative of the ABIM Foundation, American College of Physicians, retrieved 10 December 2013, which cites

- American College of Radiology; American Society of Neuroradiology (2010), "ACR-ASNR practice guideline for the performance of computed tomography (CT) of the brain", Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, Reston, VA, USA: American College of Radiology, archived from the original on 15 September 2012, retrieved 9 September 2012

- Transient loss of consciousness in adults and young people: NICE guideline, National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence, 25 August 2010, retrieved 9 September 2012

- Moya A, Sutton R, Ammirati F, Blanc JJ, Brignole M, Dahm JB, Deharo JC, Gajek J, Gjesdal K, Krahn A, Massin M, Pepi M, Pezawas T, Ruiz Granell R, Sarasin F, Ungar A, van Dijk JG, Walma EP, Wieling W (November 2009). "Guidelines for the diagnosis and management of syncope (version 2009)". European Heart Journal. 30 (21): 2631–71. doi:10.1093/eurheartj/ehp298. PMC 3295536. PMID 19713422.

- ^ a b c d American Headache Society (September 2013), "Five Things Physicians and Patients Should Question", Choosing Wisely: an initiative of the ABIM Foundation, American Headache Society, archived from the original on 3 December 2013, retrieved 10 December 2013, which cites

- Lewis DW, Dorbad D (September 2000). "The utility of neuroimaging in the evaluation of children with migraine or chronic daily headache who have normal neurological examinations". Headache. 40 (8): 629–32. doi:10.1046/j.1526-4610.2000.040008629.x. PMID 10971658. S2CID 14443890.

- Silberstein SD (September 2000). "Practice parameter: evidence-based guidelines for migraine headache (an evidence-based review): report of the Quality Standards Subcommittee of the American Academy of Neurology". Neurology. 55 (6): 754–62. doi:10.1212/WNL.55.6.754. PMID 10993991.

- Medical Advisory, Secretariat (2010). "Neuroimaging for the evaluation of chronic headaches: an evidence-based analysis". Ontario Health Technology Assessment Series. 10 (26): 1–57. PMC 3377587. PMID 23074404.

- ^ Levivier M, Massager N, Wikler D, Lorenzoni J, Ruiz S, Devriendt D, David P, Desmedt F, Simon S, Van Houtte P, Brotchi J, Goldman S (July 2004). "Use of stereotactic PET images in dosimetry planning of radiosurgery for brain tumors: clinical experience and proposed classification". Journal of Nuclear Medicine. 45 (7): 1146–54. PMID 15235060.

- ^ Jeeves MA (1994). Mind Fields: Reflections on the Science of Mind and Brain. Grand Rapids, MI: Baker Books. p. 21.

- ^ Dockrill P (10 July 2019). "100-Hour-Long MRI of Human Brain Produces Most Detailed 3D Images Yet". www.sciencealert.com.

- ^ a b Nilsson LG, Markowitsch HJ (1999). Cognitive Neuroscience of Memory. Seattle: Hogrefe & Huber Publishers.

- ^ a b Sarikaya I (2015-10-12). "PET studies in epilepsy". American Journal of Nuclear Medicine and Molecular Imaging. 5 (5): 416–430. PMC 4620171. PMID 26550535.

- ^ Philip Ball Brain Imaging Explained

- ^ "SPECT Systems for Brain Imaging". Retrieved July 24, 2014.

- ^ "SPECT Brain Imaging". Retrieved January 12, 2016.

- ^ Akdemir ÜÖ, Bora Tokçaer A, Atay LÖ (April 2021). "Dopamine transporter SPECT imaging in Parkinson's disease and parkinsonian disorders". Turkish Journal of Medical Sciences. 51 (2): 400–410. doi:10.3906/sag-2008-253. PMC 8203173. PMID 33237660.

- ^ Kim S, Mountz JM (2011). "SPECT Imaging of Epilepsy: An Overview and Comparison with F-18 FDG PET". International Journal of Molecular Imaging. 2011 813028. doi:10.1155/2011/813028. PMC 3139140. PMID 21785722.

- ^ Massachusetts General Hospital. "Team publishes on highest resolution brain MRI scan". medicalxpress.com.

- ^ Eklund A, Nichols TE, Knutsson H (July 2016). "Cluster failure: Why fMRI inferences for spatial extent have inflated false-positive rates". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 113 (28): 7900–7905. Bibcode:2016PNAS..113.7900E. doi:10.1073/pnas.1602413113. PMC 4948312. PMID 27357684.

- ^ Smith K (March 5, 2008). "Mind-reading with a brain scan". Nature News. Nature Publishing Group. Retrieved 2008-03-05.

- ^ Keim B (March 5, 2008). "Brain Scanner Can Tell What You're Looking At". Wired News. CondéNet. Retrieved 2015-09-16.

- ^ Videtič Paska A, Kouter K (August 2021). "Machine learning as the new approach in understanding biomarkers of suicidal behavior". Bosnian Journal of Basic Medical Sciences. 21 (4): 398–408. doi:10.17305/bjbms.2020.5146. PMC 8292863. PMID 33485296.

- ^ Eggebrecht AT, White BR, Ferradal SL, Chen C, Zhan Y, Snyder AZ, Dehghani H, Culver JP (July 2012). "A quantitative spatial comparison of high-density diffuse tomography and fMRI cortical mapping". NeuroImage. 61 (4): 1120–8. doi:10.1016/j.neuroimage.2012.01.124. PMC 3581336. PMID 22330315.

- ^ Eggebrecht AT, Ferradal SL, Robichaux-Viehoever A, Hassanpour MS, Dehghani H, Snyder AZ, Hershey T, Culver JP (June 2014). "Mapping distributed brain function and networks with diffuse optical tomography". Nature Photonics. 8 (6): 448–454. Bibcode:2014NaPho...8..448E. doi:10.1038/nphoton.2014.107. PMC 4114252. PMID 25083161.

- ^ Boto E, Holmes N, Leggett J, Roberts G, Shah V, Meyer SS, et al. (March 2018). "Moving magnetoencephalography towards real-world applications with a wearable system". Nature. 555 (7698): 657–661. Bibcode:2018Natur.555..657B. doi:10.1038/nature26147. PMC 6063354. PMID 29562238.

- ^ Wolters CH, Anwander A, Tricoche X, Weinstein D, Koch MA, MacLeod RS (April 2006). "Influence of tissue conductivity anisotropy on EEG/MEG field and return current computation in a realistic head model: a simulation and visualization study using high-resolution finite element modeling". NeuroImage. 30 (3): 813–26. doi:10.1016/j.neuroimage.2005.10.014. hdl:11858/00-001M-0000-0019-1079-8. PMID 16364662. S2CID 5578998.

- ^ Ramon C, Haueisen J, Schimpf PH (October 2006). "Influence of head models on neuromagnetic fields and inverse source localizations". BioMedical Engineering OnLine. 5 (1) 55. doi:10.1186/1475-925X-5-55. PMC 1629018. PMID 17059601.

- ^ "Researchers build first modular quantum brain sensor, record signal". phys.org. Retrieved 11 July 2021.

- ^ Coussens T, Abel C, Gialopsou A, Bason MG, James TM, Orucevic F, Kruger P (10 June 2021). "Modular optically-pumped magnetometer system". arXiv:2106.05877 [physics.atom-ph].

- ^ a b c d Crosson B, Ford A, McGregor KM, Meinzer M, Cheshkov S, Li X, Walker-Batson D, Briggs RW (2010). "Functional imaging and related techniques: an introduction for rehabilitation researchers". Journal of Rehabilitation Research and Development. 47 (2): vii–xxxiv. doi:10.1682/jrrd.2010.02.0017. PMC 3225087. PMID 20593321.

- ^ Tsai LL, Grant AK, Mortele KJ, Kung JW, Smith MP (October 2015). "A Practical Guide to MR Imaging Safety: What Radiologists Need to Know". Radiographics. 35 (6): 1722–37. doi:10.1148/rg.2015150108. PMID 26466181.

- ^ Center for Devices and Radiological Health. "MRI (Magnetic Resonance Imaging) - MRI Safety Posters". www.fda.gov. Retrieved 2018-04-10.[dead link]

- ^ a b Brenner DJ, Hall EJ (November 2007). "Computed tomography--an increasing source of radiation exposure". The New England Journal of Medicine. 357 (22): 2277–84. doi:10.1056/NEJMra072149. PMID 18046031. S2CID 2760372.

- ^ Smith-Bindman R (July 2010). "Is computed tomography safe?". The New England Journal of Medicine. 363 (1): 1–4. doi:10.1056/NEJMp1002530. PMID 20573919.

- ^ What happens during a PET scan?. 2016-12-30.

External links

[edit]- The Whole Brain Atlas @ Harvard

- Lecture notes on mathematical aspects of neuroimaging by Will Penny, University College London

- "Transcranial Magnetic Stimulation". by Michael Leventon in association with MIT AI Lab.

- NeuroDebian – a complete operating system targeting neuroimaging

.gif/250px-Parasagittal_MRI_of_human_head_in_patient_with_benign_familial_macrocephaly_prior_to_brain_injury_(ANIMATED).gif)

.gif)

![MR Safe[35]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/6/6e/MR_safe_sign.svg/180px-MR_safe_sign.svg.png)