Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

English art

View on Wikipedia

| Culture of England |

|---|

|

| History |

| People |

| Mythology and folklore |

| Cuisine |

| Religion |

| Art |

| Literature |

English art is the body of visual arts made in England. England has Europe's earliest and northernmost ice-age cave art.[1] Prehistoric art in England largely corresponds with art made elsewhere in contemporary Britain, but early medieval Anglo-Saxon art saw the development of a distinctly English style,[2] and English art continued thereafter to have a distinct character. English art made after the formation in 1707 of the Kingdom of Great Britain may be regarded in most respects simultaneously as art of the United Kingdom.

Medieval English painting, mainly religious, had a strong national tradition and was influential in Europe.[3] The English Reformation, which was antipathetic to art, not only brought this tradition to an abrupt stop but resulted in the destruction of almost all wall-paintings.[4][5] Only illuminated manuscripts now survive in good numbers.[6]

There is in the art of the English Renaissance a strong interest in portraiture, and the portrait miniature was more popular in England than anywhere else.[7] English Renaissance sculpture was mainly architectural and for monumental tombs.[8] Interest in English landscape painting had begun to develop by the time of the 1707 Act of Union.[9]

Substantive definitions of English art have been attempted by, among others, art scholar Nikolaus Pevsner (in his 1956 book The Englishness of English Art),[10] art historian Roy Strong (in his 2000 book The Spirit of Britain: A narrative history of the arts)[11] and critic Peter Ackroyd (in his 2002 book Albion).[12]

Earliest art

[edit]The earliest English art – also Europe's earliest and northernmost cave art – is located at Creswell Crags in Derbyshire, estimated at between 13,000 and 15,000 years old.[13] In 2003, more than 80 engravings and bas-reliefs, depicting deer, bison, horses, and what may be birds or bird-headed people were found there. The famous, large ritual landscape of Stonehenge dates from the Neolithic period; around 2600 BC.[14] From around 2150 BC, the Beaker people learned how to make bronze, and used both tin and gold. They became skilled in metal refining and their works of art, placed in graves or sacrificial pits have survived.[15] In the Iron Age, a new art style arrived as Celtic culture and spread across the British isles. Though metalwork, especially gold ornaments, was still important, stone and most likely wood were also used.[16] This style continued into the Roman period, beginning in the 1st century BC, and found a renaissance in the Medieval period. The arrival of the Romans brought the Classical style of which many monuments have survived, especially funerary monuments, statues and busts. They also brought glasswork and mosaics.[17] In the 4th century, a new element was introduced as the first Christian art was made in Britain. Several mosaics with Christian symbols and pictures have been preserved.[18] England boasts some remarkable prehistoric hill figures; a famous example is the Uffington White Horse in Oxfordshire, which "for more than 3,000 years ... has been jealously guarded as a masterpiece of minimalist art."[19]

Earliest art: gallery

[edit]-

Ochre horse illustration from the Creswell Crags; 11000-13000 BC.[20]

-

Stonehenge; 2600 BC.[21]

-

Winchester Hoard items; 75-25 BC.[23]

-

Hinton St Mary Mosaic; 4th century AD.[24]

Medieval art

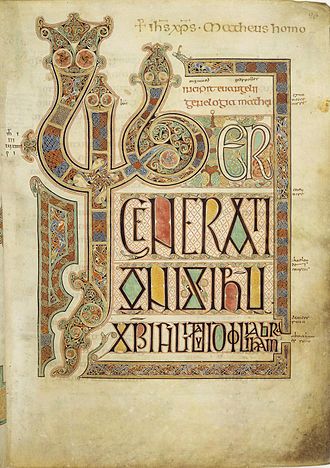

[edit]After Roman rule, Anglo-Saxon art brought the incorporation of Germanic traditions, as may be seen in the metalwork of Sutton Hoo.[25] Anglo-Saxon sculpture was outstanding for its time, at least in the small works in ivory or bone which are almost all that survive.[26] Especially in Northumbria, the Insular art style shared across the British Isles produced the finest work being produced in Europe, until the Viking raids and invasions largely suppressed the movement;[27] the Book of Lindisfarne is one example certainly produced in Northumbria.[28] Anglo-Saxon art developed a very sophisticated variation on contemporary Continental styles, seen especially in metalwork and illuminated manuscripts such as the Benedictional of St. Æthelwold.[29] None of the large-scale Anglo-Saxon paintings and sculptures that we know existed have survived.[30]

By the first half of the 11th century, English art benefited from lavish patronage by a wealthy Anglo-Saxon elite, who valued above all works in precious metals.[31] but the Norman Conquest in 1066 brought a sudden halt to this art boom, and instead works were melted down or removed to Normandy.[32] The so-called Bayeux Tapestry - the large, English-made, embroidered cloth depicting events leading up to the Norman conquest - dates to the late 11th century.[33] Some decades after the Norman conquest, manuscript painting in England was soon again among the best of any in Europe; in Romanesque works such as the Winchester Bible and the St. Albans Psalter, and then in early Gothic ones like the Tickhill Psalter.[34] The best-known English illuminator of the period is Matthew Paris (c. 1200–1259).[35] Some of the rare surviving examples of English medieval panel paintings, such as the Westminster Retable and Wilton Diptych, are of the highest quality.[36] From the late 14th century to the early 16th century, England had a considerable industry in Nottingham alabaster reliefs for mid-market altarpieces and small statues, which were exported across Northern Europe.[37] Another art form introduced through the church was stained glass, which was also adopted for secular uses.[38]

Medieval art: gallery

[edit]-

Sutton Hoo helmet; c. 625.[39]

-

Lindisfarne Gospels; c. 700.[40]

-

Lichfield Gospels; c. 730.[41]

-

The Queen Mary Psalter; 1310–1320.[47]

-

Gorleston Psalter; 14th century.[49]

-

Tickhill Psalter; 14th century.[50]

16th and 17th centuries

[edit]Nicholas Hilliard (c. 1547–7 January 1619) – "the first native-born genius of English painting"[54] – began a strong English tradition in the portrait miniature.[55] The tradition was continued by Hilliard's pupil Isaac Oliver (c. 1565–bur. 2 October 1617), whose French Huguenot parents had escaped to England in the artist's childhood.

Other notable English artists across the period include: Nathaniel Bacon (1585–1627); John Bettes the Elder (active c. 1531–1570) and John Bettes the Younger (died 1616); George Gower (c. 1540–1596), William Larkin (early 1580s–1619), and Robert Peake the Elder (c. 1551–1619).[56] The artists of the Tudor court and their successors until the early 18th century included a number of influential imported talents: Hans Holbein the Younger, Anthony van Dyck, Peter Paul Rubens, Orazio Gentileschi and his daughter Artemisia, Sir Peter Lely (a naturalised English subject from 1662), and Sir Godfrey Kneller (a naturalised English subject by the time of his 1691 knighthood).[57]

The 17th century saw a number of significant English painters of full-size portraits, most notably William Dobson 1611 (bapt. 1611–bur. 1646); others include Cornelius Johnson (bapt. 1593–bur. 1661)[58] and Robert Walker (1599–1658). Samuel Cooper (1609–1672) was an accomplished miniaturist in Hilliard's tradition, as was his brother Alexander Cooper (1609–1660), and their uncle, John Hoskins (1589/1590–1664). Other notable portraitists of the period include: Thomas Flatman (1635–1688), Richard Gibson (1615–1690), the dissolute John Greenhill (c. 1644–1676), John Riley (1646–1691), and John Michael Wright (1617–1694). Francis Barlow (c. 1626–1704) is known as "the father of British sporting painting";[59] he was England's first wildlife painter, beginning a tradition that reached a high-point a century later, in the work of George Stubbs (1724–1806).[60] English women began painting professionally in the 17th century; notable examples include Joan Carlile (c. 1606–79), and Mary Beale (née Cradock; 1633–1699).[61]

In the first half of the 17th century the English nobility became important collectors of European art, led by King Charles I and Thomas Howard, 21st Earl of Arundel.[62] By the end of the 17th century, the Grand Tour – a trip of Europe giving exposure to the cultural legacy of classical antiquity and the Renaissance – was de rigueur for wealthy young Englishmen.[63]

16th and 17th centuries: gallery

[edit]-

Nicholas Hilliard's Young Man Among Roses; 1587.[67]

-

Isaac Oliver's A Young Man Seated Under a Tree; 1590–1595.[68]

-

Francis Barlow's Coursing the Hare; 1686.[77]

18th and 19th centuries

[edit]In the 18th century, English painting's distinct style and tradition continued to concentrate frequently on portraiture, but interest in landscapes increased, and a new focus was placed on history painting, which was regarded as the highest of the hierarchy of genres,[79] and is exemplified in the extraordinary work of Sir James Thornhill (1675/1676–1734). History painter Robert Streater (1621–1679) was highly thought of in his time.[80]

William Hogarth (1697–1764) reflected the burgeoning English middle-class temperament — English in habits, disposition, and temperament, as well as by birth. His satirical works, full of black humour, point out to contemporary society the deformities, weaknesses and vices of London life. Hogarth's influence can be found in the distinctively English satirical tradition continued by James Gillray (1756–1815), and George Cruikshank (1792–1878).[81] One of the genres in which Hogarth worked was the conversation piece, a form in which certain of his contemporaries also excelled: Joseph Highmore (1692–1780), Francis Hayman (1708–1776), and Arthur Devis (1712–1787).[82]

Portraits were in England, as in Europe, the easiest and most profitable way for an artist to make a living, and the English tradition continued to show the relaxed elegance of the portrait-style traceable to Van Dyck. The leading portraitists are: Thomas Gainsborough (1727–1788); Sir Joshua Reynolds (1723–1792), founder of the Royal Academy of Arts; George Romney (1734–1802); Lemuel "Francis" Abbott (1760/61–1802); Richard Westall (1765–1836); Sir Thomas Lawrence (1769–1830); and Thomas Phillips (1770–1845). Also of note are Jonathan Richardson (1667–1745) and his pupil (and defiant son-in-law) Thomas Hudson (1701–1779). Joseph Wright of Derby (1734–1797) was well known for his candlelight pictures; George Stubbs (1724–1806) and, later, Edwin Henry Landseer (1802–1873) for their animal paintings. By the end of the century, the English swagger portrait was much admired abroad.[83]

London's William Blake (1757–1827) produced a diverse and visionary body of work defying straightforward classification; critic Jonathan Jones regards him as "far and away the greatest artist Britain has ever produced".[84] Blake's artist friends included neoclassicist John Flaxman (1755–1826), and Thomas Stothard (1755–1834) with whom Blake quarrelled.

In the popular imagination English landscape painting from the 18th century onwards typifies English art, inspired largely from the love of the pastoral and mirroring as it does the development of larger country houses set in a pastoral rural landscape.[85] Two English Romantics are largely responsible for raising the status of landscape painting worldwide: John Constable (1776–1837) and J. M. W. Turner (1775–1851), who is credited with elevating landscape painting to an eminence rivalling history painting.[86][87] Other notable 18th and 19th century landscape painters include: George Arnald (1763–1841); John Linnell (1792–1882), a rival to Constable in his time; George Morland (1763–1804), who developed on Francis Barlow's tradition of animal and rustic painting; Samuel Palmer (1805–1881); Paul Sandby (1731–1809), who is recognised as the father of English watercolour painting;[88] and subsequent watercolourists John Robert Cozens (1752–1797), Turner's friend Thomas Girtin (1775–1802), and Thomas Heaphy (1775–1835).[89]

The early 19th century saw the emergence of the Norwich school of painters, the first provincial art movement outside of London. Short-lived owing to sparse patronage and internal dissent, its prominent members were "founding father" John Crome (1768–1821), John Sell Cotman (1782–1842), James Stark (1794–1859), and Joseph Stannard (1797–1830).[90]

The Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood movement, established in the 1840s, dominated English art in the second half of the 19th century. Its members — William Holman Hunt (1827–1910), Dante Gabriel Rossetti (1828–1882), John Everett Millais (1828–1896) and others — concentrated on religious, literary, and genre works executed in a colorful and minutely detailed, almost photographic style.[91] Ford Madox Brown (1821–1893) shared the Pre-Raphaelites' principles.[92]

Leading English art critic John Ruskin (1819–1900) was hugely influential in the latter half of the 19th century; from the 1850s he championed the Pre-Raphaelites, who were influenced by his ideas.[93] William Morris (1834–1896), founder of the Arts and Crafts Movement, emphasised the value of traditional craft skills which seemed to be in decline in the mass industrial age. His designs, like the work of the Pre-Raphaelite painters with whom he was associated, referred frequently to medieval motifs.[94] English narrative painter William Powell Frith (1819–1909) has been described as the "greatest British painter of the social scene since Hogarth",[95] and painter and sculptor George Frederic Watts (1817–1904) became famous for his symbolist work.

The gallant spirit of 19th century English military art helped shape Victorian England's self-image.[96] Notable English military artists include: John Edward Chapman 'Chester' Mathews (1843–1927);[97] Lady Butler (1846–1933);[98] Frank Dadd (1851–1929); Edward Matthew Hale (1852–1924); Charles Edwin Fripp (1854–1906);[99] Richard Caton Woodville, Jr. (1856–1927);[100] Harry Payne (1858–1927);[101] George Delville Rowlandson (1861–1930); and Edgar Alfred Holloway (1870–1941).[102] Thomas Davidson (1842–1919), who specialised in historical naval scenes,[103] incorporated remarkable reproductions of Nelson-related works by Arnald, Westall and Abbott in England's Pride and Glory (1894).[104]

To the end of the 19th century, the art of Aubrey Beardsley (1872–1898) contributed to the development of Art Nouveau, and suggested, among other things, an interest in the visual art of Japan.[105]

18th and 19th centuries: gallery

[edit]-

Arthur Devis's "conversation piece" portrait of the East India Company's Robert James and family; 1751.[111]

-

Richard Westall's Nelson in conflict with a Spanish launch, 3 July 1797; 1806.[120]

-

Thomas Stothard's Procession of the Canterbury Pilgrims; 1806–7.[121]

-

George Arnald's The Destruction of 'L'Orient' at the Battle of the Nile, 1 August 1798; 1825–27.[125]

-

John Constable's The Hay Wain; c. 1821

-

Constable's Salisbury Cathedral from the Bishop's Grounds; c. 1826 version

-

Thomas Davidson's England's Pride and Glory; 1894.[134]

20th century

[edit]Impressionism found a focus in the New English Art Club, founded in 1886.[136] Notable members included Walter Sickert (1860–1942) and Philip Wilson Steer (1860–1942), two English painters with coterminous lives who became influential in the 20th century. Sickert went on to the post-impressionist Camden Town Group, active 1911–1913, and was prominent in the transition to Modernism.[137] Steer's sea and landscape paintings made him a leading Impressionist, but later work displays a more traditional English style, influenced by both Constable and Turner.[138]

Paul Nash (1889–1946) played a key role in the development of Modernism in English art. He was among the most important landscape artists of the first half of the twentieth century, and the artworks he produced during World War I are among the most iconic images of the conflict.[139] Nash attended the Slade School of Art, where the remarkable generation of artists who studied under the influential Henry Tonks (1862–1937) included, too, Harold Gilman (1876–1919), Spencer Gore (1878–1914), David Bomberg (1890–1957), Stanley Spencer (1891–1959), Mark Gertler (1891–1939), and Roger Hilton (1911–1975).

Modernism's most controversial English talent was writer and painter Wyndham Lewis (1882–1957). He co-founded the Vorticist movement in art, and after becoming better known for his writing than his painting in the 1920s and early 1930s he returned to more concentrated work on visual art, with paintings from the 1930s and 1940s constituting some of his best-known work. Walter Sickert called Wyndham Lewis: "the greatest portraitist of this or any other time".[140] Modernist sculpture was exemplified by English artists Henry Moore (1898–1986), well known for his carved marble and larger-scale abstract cast bronze sculptures, and Barbara Hepworth (1903–1975), who was a leading figure in the colony of artists who resided in St Ives, Cornwall during World War II.[141]

Lancastrian L. S. Lowry (1887–1976) became famous for his scenes of life in the industrial districts of North West England in the mid-20th century. He developed a distinctive style of painting and is best known for his urban landscapes peopled with human figures often referred to as "matchstick men".[142]

Notable English artists of the mid-20th century and after include: Graham Sutherland (1903–1980); Carel Weight (1908–1997); Ruskin Spear (1911–1990); pop art pioneers Richard Hamilton (1922–2011), Peter Blake (b. 1932), and David Hockney (b. 1937); and op art exemplar Bridget Riley (b. 1931).

Following the development of Postmodernism, English art became in some respect synonymous toward the end of the 20th century with the Turner Prize; the prize, established in 1984 and named with ostensibly credible intentions after J. M. W. Turner, earned for latterday English art a reputation arguably to its detriment.[143] Prize exhibits have included a shark in formaldehyde and a dishevelled bed.[144]

While the Turner Prize establishment satisfied itself with weak conceptual homages to authentic iconoclasts like Duchamp and Manzoni,[145] it spurned original talents such as Beryl Cook (1926–2008).[146] The award ceremony has since 2000 attracted annual demonstrations by the "Stuckists", a group calling for a return to figurative art and aesthetic authenticity. Observing wryly that "the only artist who wouldn't be in danger of winning the Turner Prize is Turner", the Stuckists staged in 2000 a "Real Turner Prize 2000" exhibition, promising (by contrast) "no rubbish".[147]

20th century: gallery

[edit]-

Philip Wilson Steer's Girls Running, Walberswick Pier; 1888–94.[148]

-

Harold Gilman's Leeds market; c. 1913.[150]

-

Ruskin Spear's Patients waiting Outside a First Aid Post in a Factory; 1942.[156]

-

Carel Weight's Recruit's Progress; 1942.[157]

-

L. S. Lowry's Going to Work; 1959.

21st century

[edit]The sculptor Antony Gormley (b. 1950) expressed doubts a decade after winning the Turner Prize about his "usefulness to the human race",[162] and work including Another Place (2005) and Event Horizon (2012) has achieved both acclaim and popularity. The pseudo-subversive urban art of Banksy,[163] has been much discussed in the media.[164]

A highly visible and much praised work of public art, seen for a brief period in 2014 was Blood Swept Lands and Seas of Red, a collaboration between artist Paul Cummins (b. 1977) and theatre designer Tom Piper. The installation at the Tower of London between July and November 2014 commemorated the centenary of the outbreak of World War I; it consisted of 888,246 ceramic red poppies, each intended to represent one British or Colonial serviceman killed in the War.[165]

Leading contemporary printmakers include Norman Ackroyd and Richard Spare.[citation needed]

English art on display

[edit]See also

[edit]Further reading

[edit]- David Bindman (ed.), The Thames and Hudson Encyclopaedia of British Art (London, 1985)

- Joseph Burke, English Art, 1714–1800 (Oxford, 1976)

- William Gaunt, A Concise History of English Painting (London, 1978)

- William Gaunt, The Great Century of British Painting: Hogarth to Turner (London, 1971)

- Nikolaus Pevsner, The Englishness of English Art (London, 1956)

- William Vaughan, British Painting: The Golden Age from Hogarth to Turner (London, 1999)

- Ellis Waterhouse, Painting in Britain, 1530-1790, 4th Edn, 1978, Penguin Books (now Yale History of Art series)

References

[edit]- ^ "Britain's first nude?". The Daily Telegraph. Retrieved 28 August 2017.

- ^ "Anglo-Saxon art". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 28 August 2017.

- ^ "Western Dark Ages And Medieval Christendom". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 28 August 2017.

- ^ "The story of the Reformation needs reforming". The Daily Telegraph. Archived from the original on 23 June 2012. Retrieved 11 September 2017.

- ^ "Art under Attack: Histories of British Iconoclasm". Tate. Retrieved 28 August 2017.

- ^ "Manuscripts from the 8th to the 15th century". British Library. Archived from the original on 30 March 2020. Retrieved 28 August 2017.

- ^ "Portrait Painting in England, 1600–1800". Metropolitan Museum of Art. Retrieved 28 August 2017.

- ^ "Medieval And Renaissance Sculpture". Ashmolean Museum. Archived from the original on 12 September 2017. Retrieved 28 August 2017.

- ^ "Edge of darkness". The Guardian. Retrieved 28 August 2017.

- ^ "Nikolaus Pevsner: The Englishness of English Art: 1955". BBC Online. Retrieved 30 August 2017.

- ^ "That was then..." The Guardian. Retrieved 30 August 2017.

- ^ "Ackroyd's England". The Daily Telegraph. Retrieved 30 August 2017.

- ^ "Prehistory: Arts & Invention". English Heritage. Retrieved 28 August 2017.

- ^ "World's oldest doodle found on rock". The Daily Telegraph. Retrieved 28 August 2017.

- ^ "Why these Bronze Age relics make me jump for joy". The Daily Telegraph. Retrieved 28 August 2017.

- ^ "The Celts: not quite the barbarians history would have us believe". The Observer. Retrieved 28 August 2017.

- ^ "Romans: Arts & Invention". English Heritage. Retrieved 28 August 2017.

- ^ "Jesus, the early years". The Guardian. Retrieved 28 August 2017.

- ^ "Big Brother's logo 'defiles' White Horse". The Observer. Retrieved 10 September 2017.

- ^ "Graffiti disfigured Ice Age cave art". The Daily Telegraph. Retrieved 11 September 2017.

- ^ "Stonehenge: not archaeology, but art". The Guardian. Retrieved 11 September 2017.

- ^ "Uffington White Horse (c.1000BC)". The Independent. Retrieved 11 September 2017.

- ^ "Archaeologists and amateurs agree pact". The Guardian. Retrieved 11 September 2017.

- ^ "Sacred mysteries". The Daily Telegraph. Retrieved 11 September 2017.

- ^ "Anglo-Saxon treasure hoard casts Beowulf and wealthy warriors of Mercia in a new light". The Guardian. Retrieved 28 August 2017.

- ^ "Ivory Carvings in England from Before the Norman Conquest". BBC History. Retrieved 28 August 2017.

- ^ "Insular Art". Oxford Bibliographies Online. Retrieved 28 August 2017.

- ^ "Everything is illuminated". The Guardian. Retrieved 28 August 2017.

- ^ "Benedictional of St Aethelwold". British Library. Retrieved 28 August 2017.

- ^ "Anglo-Saxon art from the 7th century to the Norman conquest". History Today. Retrieved 28 August 2017.

- ^ "Largest Anglo-Saxon hoard in history discovered". The Daily Telegraph. Retrieved 28 August 2017.

- ^ "The Norman World of Art". History Today. Retrieved 28 August 2017.

- ^ "Campaign to bring the Bayeux Tapestry back to Britain". The Daily Telegraph. Retrieved 28 August 2017.

- ^ "Romanesque Art". Oxford Bibliographies Online. Retrieved 29 August 2017.

- ^ "Matthew Paris: English artist and historian". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 29 August 2017.

- ^ "'Rarest' medieval panel painting saved by recycling". The Daily Telegraph. Retrieved 29 August 2017.

- ^ "Alabaster Collection". Nottingham Castle. Archived from the original on 3 August 2017. Retrieved 29 August 2017.

- ^ "Object of the week: stained glass". The Daily Telegraph. Retrieved 11 September 2017.

- ^ "Savage warrior: Sutton Hoo Helmet". The Guardian. Retrieved 11 September 2017.

- ^ "Revealed: hidden art behind the gospel truth". The Guardian. Retrieved 11 September 2017.

- ^ "St Chad Gospels". Lichfield Cathedral. Archived from the original on 30 March 2020. Retrieved 11 September 2017.

- ^ "Towns and a tapestry". The Guardian. Retrieved 11 September 2017.

- ^ "Psalter returns to St Albans Cathedral". BBC News. Retrieved 11 September 2017.

- ^ "The Peterborough Psalter". Fitzwilliam Museum. Retrieved 11 September 2017.

- ^ "National Gallery unveils England's oldest altarpiece". The Guardian. Retrieved 11 September 2017.

- ^ "The Creation of the World, in the 'Flowers of History'". British Library. Archived from the original on 30 March 2020. Retrieved 11 September 2017.

- ^ "Detailed record for Royal 2 B VII". British Library. Archived from the original on 30 March 2020. Retrieved 11 September 2017.

- ^ "Luttrell Psalter". British Library. Archived from the original on 30 March 2020. Retrieved 11 September 2017.

- ^ "'Virile, if Somewhat Irresponsible' Design: The Marginalia of the Gorleston Psalter". British Library. Retrieved 11 September 2017.

- ^ "Tickhill Psalter". University of Missouri. Archived from the original on 12 September 2017. Retrieved 11 September 2017.

- ^ "A precious stone set in a silver sea: The Wilton Diptych: Andrew Graham-Dixon deciphers the royal message for so long concealed within medieval England's most famous painting". The Independent. Retrieved 11 September 2017.

- ^ "Consecration of St Thomas Becket as archbishop". Victoria and Albert Museum. Retrieved 31 August 2017.

- ^ "Midlands glazier created this medieval masterpiece". Birmingham Post. Retrieved 11 September 2017.

- ^ Wilson, Simon (1979). British Art. London: The Tate Gallery & The Bodley Head. p. 12. ISBN 0370300343.

- ^ "Small is beautiful". The Daily Telegraph. Retrieved 12 September 2017.

- ^ Gaunt, William (1978). A Concise History of English Painting. London: Thames & Hudson. pp. 15–56.

- ^ "Paintings". Royal Collection Trust. Retrieved 12 September 2017.

- ^ "Cornelius Johnson: Charles I's Forgotten Painter". National Portrait Gallery. Retrieved 29 August 2017.

- ^ Artworks by or after English art, Art UK. Retrieved 8 September 2016.

- ^ "Monkeys and Dogs Playing: Francis Barlow (1626–1704)". Art UK. Retrieved 8 September 2016.

- ^ Gaunt, William (1978). A Concise History of English Painting. London: Thames & Hudson. pp. 29–56.

- ^ "Charles I art collection reunited for first time in 350 years as Royal Academy relocates works from Van Dyke and Titian". The Daily Telegraph. Retrieved 29 August 2017.

- ^ "The Town & Country Grand Tour". Town and Country Magazine. Retrieved 29 August 2017.

- ^ "Would the real Anne Boleyn please come forward?". On the Tudor Trail. Retrieved 1 September 2017.

- ^ Montrose, Louis (2006). The Subject of Elizabeth: Authority, Gender, and Representation. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. p. 123. ISBN 0226534758.

- ^ "Portraits of Queen Elizabeth The First, Part 2: Portraits 1573-1587". Luminarium: Anthology of English Literature. Retrieved 12 September 2017.

- ^ "'Young Man Among Roses' by Nicholas Hilliard (1547–1619)". Victoria and Albert Museum. Retrieved 29 August 2017.

- ^ "A Young Man Seated Under a Tree, c. 1590-1595". Royal Collection. Retrieved 11 September 2017.

- ^ "The Final Years of Elizabeth I's Reign". History Today. Retrieved 12 September 2017.

- ^ "The only true painting of Shakespeare - probably". The Guardian. Retrieved 2 September 2017.

- ^ Wihl, Gary (1988). Literature and Ethics: Essays Presented to A. E. Malloch. Montreal, Quebec: McGill-Queen's University Press. p. 37. ISBN 0773506624.

- ^ "William Dobson: Charles II, 1630 - 1685. King of Scots 1649 - 1685. King of England and Ireland 1660 - 1685 (When Prince of Wales, with a page)". Scottish National Portrait Gallery. Retrieved 12 September 2017.

- ^ "King Charles I at his Trial". National trust. Retrieved 11 September 2017.

- ^ "John Evelyn". National Portrait Gallery, London. Retrieved 11 September 2017.

- ^ "Charles II (1630-1685) c.1676". Royal Collection Trust. Retrieved 12 September 2017.

- ^ "John Locke". National Portrait Gallery, London. Retrieved 12 September 2017.

- ^ Hodnett, Edward (1978). Francis Barlow: The First Master of English Book Illustration. London: Scolar Press. p. 106. ISBN 0859673502.

- ^ "Artist: John Riley, British, 1646-1691; Samuel Pepys". Yale University Art Gallery. Retrieved 12 September 2017.

- ^ "Painting history: Manet on a mission". The Daily Telegraph. Retrieved 29 August 2017.

- ^ "Sheldonian ceiling restored". The Guardian. Retrieved 29 August 2017.

- ^ "Hogarth, the father of the modern cartoon". The Daily Telegraph. Retrieved 29 August 2017.

- ^ Newman, Gerald (1978). Britain in the Hanoverian Age, 1714-1837. London: Routledge. p. 525. ISBN 0815303963.

- ^ "A Short History of British Portraiture". Royal Society of Portrait Painters. Retrieved 29 August 2017.

- ^ "Blake's heaven". The Guardian. Retrieved 31 August 2017.

- ^ "Constable, Turner, Gainsborough and the Making of Landscape". The Guardian. Retrieved 30 August 2017.

- ^ Lacayo, Richard (11 October 2007). "The Sunshine Boy". Time. Archived from the original on October 12, 2007.

At the turn of the 18th century, history painting was the highest purpose art could serve, and Turner would attempt those heights all his life. But his real achievement would be to make landscape the equal of history painting.

- ^ "British Watercolours 1750-1900: The Landscape Genre". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 29 August 2017.

- ^ "Paul Sandby at Royal Academy". The Daily Telegraph. Retrieved 29 August 2017.

- ^ "Landscape painting". Victoria and Albert Museum. Retrieved 29 August 2017.

- ^ "Made In England: Norfolk". BBC Online. Retrieved 29 August 2017.

- ^ "Pre-Raphaelite art: the paintings that obsessed the Victorians". The Daily Telegraph. Retrieved 29 August 2017.

- ^ "Into the Frame: the Four Loves of Ford Madox Brown by Angela Thirlwell: review". The Daily Telegraph. Retrieved 29 August 2017.

- ^ "John Ruskin's marriage: what really happened". The Guardian. Retrieved 31 August 2017.

- ^ "Who was William Morris? The textile designer and early socialist whose legacy is still felt today". The Daily Telegraph. Retrieved 31 August 2017.

- ^ "William Powell Frith, 1819–1909". Tate. Retrieved 11 September 2017.

- ^ "Artist and Empire review – a captivating look at the colonial times we still live in". The Guardian. Retrieved 31 August 2017.

- ^ "The Charge of the 21st Lancers at Omdurman, 2 September 1898". National Army Museum. Retrieved 31 August 2017.

- ^ "Tate Britain to explore - but not celebrate - art and the British Empire". The Daily Telegraph. Retrieved 31 August 2017.

- ^ "The Battle of Isandlwana, 22 January 1879". National Army Museum. Retrieved 31 August 2017.

- ^ "The Charge of the Light Brigade, 1854". National Army Museum. Retrieved 31 August 2017.

- ^ "Harry Payne: Artist". Look and Learn. Retrieved 31 August 2017.

- ^ "Edgar Alfred Holloway - 1870-1941". Canadian Anglo-Boer War Museum. Archived from the original on January 6, 2009. Retrieved 31 August 2017.

- ^ "Nelson's Last Signal at Trafalgar". National Maritime Museum. Retrieved 12 September 2017.

- ^ "England's Pride and Glory". National Maritime Museum. Retrieved 12 September 2017.

- ^ "Erotic bliss shared by all at Shunga: Sex and Pleasure in Japanese Art". The Guardian. Retrieved 30 August 2017.

- ^ "History of the Painted Hall". Old Royal Naval College. Archived from the original on 11 July 2019. Retrieved 1 September 2017.

- ^ "Alexander Pope". Museum of Fine Arts, Boston. Retrieved 1 September 2017.

- ^ "Marriage A-la-Mode: 2, The Tête à Tête". National Gallery. Retrieved 1 September 2017.

- ^ "General James Wolfe (1727-1759) as a Young Man". National Trust-Quebec House. Retrieved 1 September 2017.

- ^ "Mr and Mrs Andrews". National Gallery. Retrieved 1 September 2017.

- ^ "Great Works: The James Family (1751) by Arthur Devis". The Independent. Retrieved 1 September 2017.

- ^ "Robert Clive and Mir Jafar after the Battle of Plassey, 1757". National Portrait Gallery, London. Retrieved 1 September 2017.

- ^ "Stubbs's equine masterpiece puts animal passion into the National". The Independent. Retrieved 11 September 2017.

- ^ "Warren Hastings". National Portrait Gallery, London. Retrieved 1 September 2017.

- ^ "An Experiment on a Bird in the Air Pump". National Gallery. Retrieved 2 September 2017.

- ^ "Emma Hamilton and George Romney". Walker Art Gallery. Retrieved 1 September 2017.

- ^ "Horatio Nelson". National Portrait Gallery, London. Retrieved 1 September 2017.

- ^ "Europe: a Prophecy". British Museum. Retrieved 11 September 2017.

- ^ "Henry John Temple, 3rd Viscount Palmerston". National Portrait Gallery, London. Retrieved 11 September 2017.

- ^ "Nelson in conflict with a Spanish launch, 3 July 1797". National Maritime Museum. Retrieved 12 September 2017.

- ^ "The Pilgrimage to Canterbury, 1806–7". Tate. Retrieved 11 September 2017.

- ^ "The Plumb-pudding in danger - or - State Epicures taking un Petit Souper by Gillray". British Library. Retrieved 2 September 2017.

- ^ "Saluting the R-ts bomb uncovered on his birth day August 12th. 1816". British Museum. Retrieved 2 September 2017.

- ^ "Portrait of Duke of Wellington". Waterloo 200. Archived from the original on September 25, 2016. Retrieved 2 September 2017.

- ^ "The Destruction of 'L'Orient' at the Battle of the Nile, 1 August 1798". National Maritime Museum. Retrieved 12 September 2017.

- ^ "Portrait of Lord Byron in Albanian Dress". British Library. Archived from the original on 28 March 2017. Retrieved 1 September 2017.

- ^ "The Fighting Temeraire". National Gallery. Retrieved 1 September 2017.

- ^ "Ophelia, 1851–2". Tate. Retrieved 2 September 2017.

- ^ "Our English Coasts, 1852 ('Strayed Sheep') 1852". Tate. Retrieved 10 September 2017.

- ^ "Oil Painting - The Last of England". Birmingham Museum and Art Gallery. Retrieved 2 September 2017.

- ^ "Charles Dickens". Victoria and Albert Museum. Retrieved 11 September 2017.

- ^ "What to say about... John Ruskin". The Guardian. Retrieved 2 September 2017.

- ^ "Charles George Gordon". National Portrait Gallery, London. Retrieved 2 September 2017.

- ^ "England's Pride and Glory". Art UK. Retrieved 13 September 2017.

- ^ "The Charge of the 21st Lancers at the Battle of Omdurman, 1898". National Army Museum. Retrieved 11 September 2017.

- ^ "New English Art Club". Tate. Retrieved 1 September 2017.

- ^ "Walter Richard Sickert: British artist". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 1 September 2017.

- ^ "Philip Wilson Steer: British artist". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 1 September 2017.

- ^ "The Archival Trail: Paul Nash the war artist". Tate. Retrieved 1 September 2017.

- ^ "Wyndham Lewis: a monster - and a master of portrait painting". The Daily Telegraph. Retrieved 1 September 2017.

- ^ "Why it's time you fell in love with Britain's battered post-war statues". The Daily Telegraph. Retrieved 1 September 2017.

- ^ "LS Lowry at Tate Britain: glimpses of a world beyond". The Guardian. Retrieved 1 September 2017.

- ^ "Not all modern art is trivial buffoonery". The Daily Telegraph. Retrieved 1 September 2017.

- ^ "He's our favourite artist. So why do the galleries hate him so much?". The Guardian. Retrieved 1 September 2017.

- ^ "Art in 2015: forget the Turner prize - this was the year the Old Masters became sexy". The Daily Telegraph. Retrieved 10 September 2017.

- ^ "Beryl Cook". The Daily Telegraph. Retrieved 10 September 2017.

- ^ "Stuck on the Turner Prize". Artnet. Retrieved 12 September 2017.

- ^ "Girls Running, Walberswick Pier; 1888–94". Tate. Retrieved 1 September 2017.

- ^ "Spencer GoreInez and Taki; 1910". Tate. Retrieved 12 September 2017.

- ^ "Harold Gilman: Leeds Market, c.1913". Tate. Retrieved 12 September 2017.

- ^ "Brighton Pierrots; 1915". Tate. Retrieved 1 September 2017.

- ^ "Mark Gertler: Merry-Go-Round, 1916". Tate. Retrieved 13 September 2017.

- ^ "We are Making a New World". Imperial War Museum. Retrieved 1 September 2017.

- ^ "Sappers at Work: Canadian Tunnelling Company, R14, St Eloi". Imperial War Museum. Retrieved 11 September 2017.

- ^ "A Battery Shelled". Imperial War Museum. Retrieved 1 September 2017.

- ^ "Patients waiting outside a first aid post in a factory". Canadian War Museum. Retrieved 1 September 2017.

- ^ "Recruit's progress: medical inspection". Canadian War Museum. Retrieved 1 September 2017.

- ^ "Shipbuilding on the Clyde: The Furnaces". Imperial War Museum. Retrieved 11 September 2017.

- ^ "'World's largest tapestry' at Coventry Cathedral repaired". BBC News. Retrieved 1 September 2017.

- ^ "Four-Square (Walk Through), 1966". Tate. Retrieved 12 September 2017.

- ^ "Henry Moore exhibition at Kew is a triumph". The Daily Telegraph. Retrieved 12 September 2017.

- ^ "The legacy game: Gormley isn't the first artist to worry about his place in history". The Guardian. Retrieved 12 September 2017.

- ^ "Supposing ... Subversive genius Banksy is actually rubbish". The Guardian. Retrieved 11 September 2017.

- ^ "Britain's best-loved artwork is a Banksy. That's proof of our stupidity". The Guardian. Retrieved 11 September 2017.

- ^ "Blood-swept lands: the story behind the Tower of London poppies tribute". The Guardian. Retrieved 1 September 2017.

English art

View on GrokipediaEnglish art encompasses the visual arts—primarily painting, sculpture, architecture, and decorative arts—produced within the geographic and cultural confines of England from prehistoric times to the contemporary era.[1]

Distinctive early contributions include Celtic knotwork patterns and Anglo-Saxon metalwork artifacts, such as those from the Sutton Hoo ship burial, alongside illuminated manuscripts like the Lindisfarne Gospels, which demonstrate technical mastery in interlace designs and figural representation influenced by both insular traditions and Mediterranean imports.[2]

The Norman Conquest introduced Romanesque styles in architecture and sculpture, evolving into Gothic forms in cathedrals like Salisbury, while the Tudor period emphasized portrait miniatures and panel paintings capturing the aristocracy's likenesses with meticulous detail.[3]

From the 18th century onward, English art gained prominence in landscape painting, with John Constable's naturalistic depictions of rural scenes, as in The Hay Wain, exemplifying a Romantic emphasis on empirical observation of light, atmosphere, and national topography over idealized classical motifs.[1]

Later developments featured the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood's rejection of academic conventions in favor of vivid, detail-oriented medieval-inspired works, and the Arts and Crafts movement's advocacy for handcraftsmanship amid industrialization, influencing global design principles.[1]

These traditions reflect England's historical insularity, which fostered unique syntheses of foreign influences with indigenous practicality, though art production often lagged behind continental innovations until the 18th century due to limited patronage outside royal and ecclesiastical circles.[4]

Prehistoric and Ancient Foundations

Prehistoric Artifacts and Engravings

The earliest known artistic expressions in England date to the Upper Paleolithic period, with engravings discovered in the limestone caves of Creswell Crags in Derbyshire. These include depictions of animals such as bison, horses, and ibex, executed through finger tracings and incisions on cave walls in Church Hole cave, dated to approximately 13,000–11,000 years before present via uranium-series dating of overlying carbonate deposits.[5][6][7] This parietal art represents the northernmost extent of Magdalenian-style cave art traditions associated with late Ice Age hunter-gatherers, confirmed through microscopic analysis revealing intentional scoring rather than natural erosion.[8] Mobiliary art from the same era includes portable engraved artifacts, such as a human rib bone incised with linear patterns from Gough's Cave in Somerset, dated to around 14,700–12,200 years ago based on radiocarbon analysis of associated faunal remains.[9] Additional finds comprise engraved fragments of hare tibiae and reindeer antler bâtons percés, worked with fine incisions possibly symbolizing abstract or ritual motifs, evidencing skilled craftsmanship among nomadic groups adapting to post-glacial environments.[9] These portable pieces, analyzed via high-resolution imaging, demonstrate continuity with continental European traditions but adapted to Britain's resource-scarce landscapes.[10] In the Mesolithic period, evidence shifts to engraved personal ornaments, exemplified by a shale pendant from Star Carr in North Yorkshire, dated to circa 11,000 years ago through radiocarbon dating of contextual organic materials.[11] This artifact features deliberate incisions forming geometric patterns, interpreted as intentional design via comparative petrological and microscopic examination, marking one of the earliest known decorative objects in Britain and suggesting emerging symbolic behaviors among post-glacial foragers.[11] Neolithic and Bronze Age engravings predominantly consist of petroglyphs on rock outcrops, particularly cup-and-ring motifs concentrated in northern England, such as in Northumberland and Yorkshire, dated to 3800–1500 BC via association with dated megalithic contexts and stylistic typology.[5][12] These abstract carvings, executed by pecking or hammering with stone tools, appear on prominent landscape features, potentially serving territorial or ceremonial functions as evidenced by their visibility and clustering near burial sites.[13] At Stonehenge in Wiltshire, sarsen stones bear over 200 prehistoric engravings, primarily of Bronze Age axe-heads (about 80% of motifs) and daggers, dated to around 2500–2000 BC through correlation with metal tool typologies and radiocarbon-dated antler picks used in construction.[14] Such motifs, analyzed through 3D scanning, reflect technological prowess and possibly ancestral commemoration, distinct from earlier abstract styles.[14]Roman and Sub-Roman Artistic Legacies

The Roman conquest of Britain in 43 AD introduced artistic forms derived from Mediterranean traditions, adapted to local materials and tastes, including mosaics, frescoes, and stone sculptures that emphasized mythological and imperial themes.[15] Provincial workshops produced these works, often blending Roman iconography—such as depictions of gods like Neptune or Bacchus—with Celtic motifs, resulting in hybrid styles evident in over 200 surviving villa mosaics by the 4th century AD.[16] [17] Urban centers like Londinium and Bath featured public sculptures, including bronze statues and marble altars, while military sites along Hadrian's Wall yielded inscribed reliefs and votive offerings reflecting soldier-artisans' contributions.[15] Mosaics, laid with tesserae of stone, glass, and shell, adorned hypocaust-heated floors in elite residences, showcasing geometric patterns, hunting scenes, and narrative panels; nearly 800 examples have been documented, with peak production in the 3rd and 4th centuries AD.[17] The Fishbourne Roman Palace, constructed around 75 AD near Chichester, contains the earliest known mosaics in Britain, including a Dionysus cupids panel from the late 1st century, indicating rapid adoption of luxury flooring techniques post-conquest.[18] Similarly, the Bignor Villa in West Sussex, occupied from circa 190 AD into the 5th century, preserves intricate 4th-century mosaics with Venus, gladiators, and the Rape of Ganymede, executed in fine opus vermiculatum style rivaling continental examples.[19] Wall paintings, though rarer due to perishability, survive in fragments at sites like Lullingstone Villa, depicting garden scenes and orant figures that influenced later decorative arts.[16] Sculpture in Britain favored local limestone and sandstone for funerary monuments, deities, and imperial dedications, with fewer marble imports than in core provinces; examples include the Bath Medusa roundel (1st century AD) and Mithras tauroctony reliefs from Temple of Mithras excavations.[15] Metalwork, such as the silver Mildenhall Treasure (4th century AD) with pagan banquet scenes, demonstrates continuity in silversmithing techniques blending Roman realism with abstract designs. Architectural legacies encompassed concrete foundations, arches, and hypocaust systems in public baths and villas, though wood-framed structures predominated in rural areas.[20] Following the Roman withdrawal in 410 AD, Sub-Roman Britain saw a sharp decline in large-scale artistic production amid economic contraction and invasions, with no new mosaics or monumental sculptures attested after circa 450 AD.[21] However, archaeological evidence indicates limited continuity in utilitarian arts: Roman-style fineware pottery persisted into the mid-5th century at sites like Tintagel, suggesting localized workshops maintained wheel-thrown techniques and stamped decorations.[21] Villas like Bignor remained occupied, with repairs to existing mosaics implying pragmatic reuse rather than innovation, while pewter vessels and fibulae retained Roman-inspired motifs into the 6th century, bridging to Anglo-Saxon metalworking.[19] This residual legacy, rooted in elite Romano-British enclaves, provided technical precedents for medieval stone carving and enameling, though overshadowed by incoming Germanic styles.[22]Medieval Developments

Anglo-Saxon Metalwork and Illuminated Manuscripts

Anglo-Saxon metalwork exemplifies advanced craftsmanship from the 5th to 11th centuries, primarily surviving in jewelry, weapons, and fittings buried with elites. Techniques included filigree wirework, granulation, cloisonné enameling, and inlays of garnets or niello, often drawing from Germanic Migration Period styles adapted with local innovations.[23]/11:_Medieval_Art/11.02:_Anglo_Saxon_Art) Early pieces featured animal interlace and mask motifs rooted in pagan symbolism, transitioning post-conversion around 600 AD to incorporate Christian crosses and figures.[24] The Sutton Hoo ship burial, excavated in 1939 near Woodbridge, Suffolk, yielded a 7th-century helmet, shoulder clasps, and purse cover of gold, garnets, and millefiori glass, reflecting elite status possibly linked to King Rædwald of East Anglia (d. c. 624–625).[25] These artifacts demonstrate cloisonné and interlocking beast patterns influenced by Scandinavian and continental Germanic traditions, with over 200 garnets sourced likely from India via trade routes.[23] Later, the 9th-century Alfred Jewel, found in 1693 at North Petherton, Somerset, features gold framing rock crystal over cloisonné enamel depicting a robed figure holding lotuses or sceptres, inscribed "Ælfred mec heht gewyrcan" (Alfred ordered me made), attributed to King Alfred the Great (r. 871–899) for scholarly use.[26] Illuminated manuscripts emerged with Christianization, blending Insular (Hiberno-Saxon) styles of intricate interlace, carpet pages, and zoomorphic forms using pigments like lapis lazuli, vermilion, and orpiment on vellum.[27] Produced in monastic scriptoria from the 7th century, they featured full-page evangelist portraits, symbolic creatures, and framed initials, influenced by Celtic knotwork and Mediterranean iconography via Irish missionaries.[27] The Book of Durrow, dated c. 700, contains the Vulgate Gospels with carpet pages in red, yellow, and green, exemplifying early Insular abstraction possibly from Iona or Northumbria.[28] The Lindisfarne Gospels, created c. 715–720 at Lindisfarne Priory, Northumberland, comprise 258 folios with vibrant miniatures, including author portraits and Eusebian canon tables, attributed to Eadfrith, bishop from 698–721.[27] Its hybrid style merges Celtic abstraction—evident in labyrinthine patterns and bird-beast hybrids—with Byzantine figural realism, using gold and silver inks for luminescence.[27] Later 10th–11th-century works, like the Benedictional of St. Æthelwold (c. 963–984), introduced fuller Carolingian-inspired narratives and acanthus borders, reflecting Winchester school revival amid monastic reform.[29] These manuscripts served liturgical and educational purposes, preserving texts amid Viking raids that dispersed many originals.[27]Norman Romanesque and Early Gothic Forms

The Norman Conquest of 1066 introduced Romanesque architecture to England on a grand scale, supplanting earlier Anglo-Saxon styles with robust stone structures emphasizing solidity and mass.[30] This Norman variant featured rounded arches, thick walls pierced by minimal windows, barrel or groin vaults, and decorative arcading, often adorned with sculpted motifs of beasts and interlacing patterns derived from continental influences.[31] Key exemplars include Durham Cathedral, begun in 1093, which exemplifies early rib vaulting innovations alongside traditional Romanesque heft, and Winchester Cathedral, initiated around 1079, showcasing elongated naves and transepts suited to monastic and episcopal functions.[32] These forms reflected the Normans' priorities of fortification-like durability and symbolic power, with over a century of predominant use in major ecclesiastical buildings post-Conquest.[33] By the late 12th century, English architecture transitioned toward Gothic elements, adapting French innovations like pointed arches and ribbed vaults to achieve greater height and light penetration while retaining Romanesque mass in hybrid forms.[34] The Early English Gothic phase, spanning roughly 1180 to 1275, emphasized lancet windows, stiff-leaf capitals, and dog-tooth ornamentation, as seen in Canterbury Cathedral's choir reconstruction from 1175 to 1184 following a fire, which introduced transitional pointed arches over a Romanesque base.[35] Lincoln Cathedral, commenced in 1192 after its predecessor's collapse, further advanced this style with its facade's layered arcading and interior's elongated proportions, prioritizing verticality without full flying buttresses.[36] Wells Cathedral, starting in the 1190s, integrated sculptural richness in its west front porches, blending continuity with Romanesque precedents in nave design.[35] This evolution stemmed from structural necessities—pointed arches distributing weight more efficiently than rounded ones—and cultural exchanges via clergy trained abroad, enabling taller clerestories and narrative stained glass, though English examples often moderated French exuberance for pragmatic stability.[37] Surviving sculpture, such as Durham's chapter house corbels depicting grotesque figures from around 1096, and Lincoln's angel choir screens from the early 13th century, underscore the era's integration of architectural form with figural art, prioritizing didactic symbolism over illusionism.[32] These developments laid groundwork for later Perpendicular Gothic, with Romanesque persistence in rural or monastic contexts into the 13th century.[38]Early Modern Period (16th-17th Centuries)

Tudor Portraiture and Courtly Influences

Tudor portraiture emerged as a dominant form in English art from the late 15th to early 17th centuries, serving primarily to assert royal authority and dynastic legitimacy following the Wars of the Roses. Monarchs like Henry VIII commissioned portraits to project power and stability, often employing foreign artists who introduced Netherlandish techniques emphasizing detailed realism and symbolic elements. These works departed from medieval conventions by prioritizing individualized likenesses over stylized religious iconography, reflecting the Renaissance humanist interest in the human form while adapting to courtly needs for propaganda and diplomacy.[39] Hans Holbein the Younger, a German painter who arrived in England around 1526 and settled permanently by 1532, became the preeminent court artist under Henry VIII. Appointed King's Painter in 1537 with an annual salary, Holbein produced over 150 surviving portrait drawings and paintings of the king, his wives, and courtiers, capturing psychological depth and physical presence through precise linear techniques and rich symbolism, such as codpieces signifying virility in Henry's images. His portraits, including the Whitehall Mural cartoon of circa 1537 depicting Henry with Jane Seymour, were designed for public display in palaces to reinforce the Tudor image of invincibility, influencing subsequent English portraiture by establishing a standard for unflattering accuracy over idealization. Holbein's role extended to diplomatic vetting, as seen in his 1539 portrait of Anne of Cleves, which Henry deemed too flattering yet proceeded with the marriage based on it.[40][41][42] Courtly influences shaped portraiture's evolution, with Tudor monarchs fostering a cosmopolitan environment by recruiting Flemish miniaturists like Lucas Horenbout, who arrived in 1525 and introduced the limner tradition of small-scale portraits on vellum for personal wear in lockets. Under Elizabeth I, English-born Nicholas Hilliard (1547–1619), trained as a goldsmith, advanced this medium, producing over 20 known miniatures of the queen from the 1570s onward, depicting her eternally youthful with elaborate jewelry and symbolic flora to embody eternal virginity and divine right. These intimate works, often 1-2 inches in height and painted in watercolor on ivory, circulated among courtiers to foster loyalty and were influenced by French limning techniques encountered during Hilliard's travels. Elizabeth's 1562 grant of a monopoly on miniature production underscored the court's control over artistic representation for political cohesion.[43][44] The reliance on imported talent highlighted England's nascent native artistic tradition, yet court patronage spurred stylistic innovations like frontal poses and emblematic backgrounds, blending Northern European precision with emerging Italianate grandeur. By the late Tudor era, portraits served not only monarchs but also nobility, with copies and versions proliferating for household display, as evidenced by workshop practices documented in inventories from the 1590s. This period laid foundational techniques for later English portraiture, prioritizing verisimilitude and status symbols amid the era's religious upheavals and succession anxieties.[45][46]Baroque Tendencies and Civil War Disruptions

The Baroque style, characterized by dramatic movement, rich detailing, and emotional intensity, began influencing English art in the early 17th century through continental imports and royal patronage. Under King Charles I, Flemish painter Anthony van Dyck served as principal court artist from 1632 until his death in 1641, introducing Baroque portraiture techniques such as fluid brushwork, elongated figures, and a sense of aristocratic grandeur that elevated English sitters to near-mythic status.[47][48] Van Dyck's works, including multiple portraits of Charles I—such as the equestrian Charles I in Three Positions (c. 1635)—emphasized the monarch's divine right through dynamic poses and luminous effects, profoundly shaping subsequent English portrait traditions for over a century.[49] This period saw limited native adoption of full Baroque exuberance, with English artists like William Dobson initially training under influences such as Van Dyck's studio, blending Flemish drama with local realism in preparatory sketches and smaller commissions.[50] The English Civil War (1642–1651) severely disrupted these emerging tendencies, fragmenting royal patronage and forcing artists into precarious wartime roles. With Van Dyck's death in 1641, Dobson emerged as Charles I's de facto court painter at the royalist stronghold in Oxford from 1642, producing around 60 known works—primarily portraits of soldiers, courtiers, and exiles—that captured the raw exigencies of conflict, such as in his Portrait of an Officer of the Royalist Army (c. 1644–1645), marked by somber tones and introspective gazes reflecting depleted resources.[51][52] Dobson's output declined amid military defeats; he died impoverished in 1646 at age 35, his career curtailed by the war's instability, which scattered royal collections and reduced commissions to survival-level endeavors.[50] Parliamentarian iconoclasm, intensified under Puritan influence, targeted perceived idolatrous images, leading to the destruction of altarpieces and royalist effigies, though documented losses were more pronounced in ecclesiastical contexts than secular portraiture.[53] Post-1649, following Charles I's execution, the dispersal of the royal art collection—comprising over 1,500 works seized and auctioned by Parliament—further stalled Baroque momentum, as elite buyers abroad absorbed many pieces, depriving England of continuity in stylistic development.[50] Native artists faced economic collapse, with painting shifting toward utilitarian or covert royalist propaganda, delaying fuller Baroque expression until the Restoration in 1660. This interregnum not only impoverished practitioners like Dobson but also fostered a cautious realism in surviving works, prioritizing endurance over ornamentation amid ideological purges.[54]Enlightenment Era (18th Century)

Portraiture Dominance and Grand Manner

In the eighteenth century, portraiture became the leading genre in English painting, fueled by patronage from the aristocracy and a rising mercantile elite who commissioned works to affirm social standing and personal legacy amid growing economic prosperity.[55][56] This dominance reflected a cultural emphasis on individualism and hierarchy, with portraits serving as tools for self-fashioning rather than history or landscape subjects, which remained secondary despite emerging interests. The Grand Manner style, adapted from continental history painting to elevate portraiture, characterized much of this output by prioritizing idealized forms drawn from classical antiquity and High Renaissance precedents over photographic realism.[57] Artists employed full-length compositions, dramatic poses, rich drapery, and symbolic accessories to convey moral virtue, intellectual depth, and nobility, abstracting from individual particulars to achieve a universal grandeur.[58] Sir Joshua Reynolds (1723–1792), the era's preeminent portraitist, systematized this approach as the first president of the Royal Academy of Arts, established in 1768, arguing in his Discourses on Art (delivered 1769–1790) that painters should generalize nature's imperfections to emulate ancient masters like Michelangelo and Raphael, thereby raising portraiture to high art.[59] Reynolds' method involved studio experimentation with pigments and varnishes to mimic old master effects, producing luminous, heroic depictions of sitters such as Commodore Augustus Keppel (1753–1754) or the Marquess of Rockingham (1766–1768), which solidified his commercial success—charging up to 200 guineas for full-lengths—and influenced contemporaries like Thomas Gainsborough, though the latter favored looser, more naturalistic "fancy portraits" integrated with landscape elements.[58] This stylistic tension underscored portraiture's adaptability, yet Reynolds' advocacy cemented the Grand Manner as the benchmark for aristocratic commissions, marking the "Golden Age of British portraiture" by the 1770s.[58] Gainsborough's rivalry, evident in works like Mr and Mrs Andrews (c. 1750), highlighted a parallel strain prioritizing conversational intimacy, but the Grand Manner's prestige endured due to its alignment with Enlightenment ideals of refined civility.[60]Satirical and Moralistic Art

In the 18th century, English satirical and moralistic art flourished through engravings and prints that critiqued social vices, moral decay, and political folly, making commentary accessible beyond elite patronage via affordable reproductions sold in urban print shops. William Hogarth (1697–1764) pioneered this genre with "modern moral subjects," narrative series warning of vice's consequences through sequential scenes of human downfall. His engravings, protected by the Copyright Act of 1735 which he lobbied for, depicted realistic London life to underscore causal links between indulgence and ruin, prioritizing empirical observation over idealized history painting.[61] Hogarth's A Harlot's Progress (engravings published 1732), based on destroyed paintings from 1731, comprises six plates tracing a naive country girl's seduction into prostitution, imprisonment, and death from venereal disease, highlighting urban corruption's rapid toll on the vulnerable.[61] Similarly, Gin Lane (1751), paired with Beer Street, graphically illustrates gin's societal devastation—infants neglected, madness, and suicide amid poverty—to advocate the Gin Act restricting cheap spirits, contrasting temperate prosperity with intemperance's chaos.[62] These works embedded didactic verses and details like discarded Bibles to enforce moral realism, influencing public reform efforts by evidencing vice's empirical outcomes rather than abstract virtue.[63] Building on Hogarth's foundation, James Gillray (1756–1815) elevated political caricature, producing nearly 1,000 etchings from the 1780s onward that lampooned monarchs, ministers, and foreign threats with exaggerated physiognomy and biting wit. His French Liberty, British Slavery (1792) juxtaposes revolutionary France's guillotines against England's parliamentary stability, satirizing Jacobin excess while defending constitutional monarchy through visual hyperbole grounded in current events.[64] Thomas Rowlandson (1756–1827), collaborating often with publisher Rudolph Ackermann, focused on social satire in over 10,000 drawings and prints depicting elite dissipation and urban absurdities, such as The Coffee House (c. 1790), where patrons gossip amid vices like gambling and lechery, exposing class hypocrisies via fluid, humorous lines.[65] These artists' output, disseminated in editions of hundreds at low cost, shaped public discourse by rendering complex causal critiques— from moral laxity to political intrigue—into consumable, evidence-based visual arguments, distinct from continental allegory.[66]Romantic and Victorian Periods (19th Century)

Landscape Innovations: Constable and Turner

John Constable (1776–1837) and J. M. W. Turner (1775–1851) transformed English landscape painting in the Romantic era by prioritizing direct engagement with nature over classical topoi, elevating the genre from ancillary status to a vehicle for personal and emotional expression. Constable, rooted in the Suffolk countryside, emphasized empirical observation and meteorological accuracy, producing detailed plein-air sketches that informed his studio compositions. Turner, conversely, explored light's dissolution of form through experimental color and brushwork, often infusing landscapes with historical or contemporary motifs to evoke sublime transience. Their innovations, showcased at Royal Academy exhibitions from the 1810s onward, challenged prevailing portraiture dominance and anticipated modernist abstraction.[67][68] Constable's method involved accumulating open-air studies over years, culminating in monumental "six-foot" canvases for Royal Academy display between 1819 and 1825, such as The Hay Wain (1821, oil on canvas, 130.2 × 185.4 cm), which depicts a mundane rural scene near Flatford Mill with vivid sky effects derived from on-site sketches and a full-scale preparatory oil.[69][70] He applied dabs of white paint to evoke flickering light across foliage and water, capturing transient cloud formations—over 100 studies from Hampstead in 1821–1822 alone—to convey nature's vitality without idealization.[71] This fidelity to "truth to nature" dignified everyday English scenery, influencing the Barbizon school's realism abroad while critiquing urban industrialization's encroachment.[72]

Turner's landscapes integrated watercolor-derived techniques into oils, layering transparent washes and reserving highlights to simulate atmospheric luminosity, as in his categorization of scenery into pastoral, mountainous, and marine types studied during European tours.[73] His vigorous, loose brushstrokes in later works, like those depicting steamships amid tempests, blurred boundaries between sea, sky, and vapor, prioritizing perceptual effects over delineation and prefiguring Impressionism's focus on evanescent light.[74] Dubbed the "painter of light" for brilliant color saturations in sunsets and seascapes, Turner embedded modern industrial elements—such as locomotives in Rain, Steam, and Speed (1844)—to register Britain's technological flux within nature's grandeur.[75][68] At Royal Academy varnishing days, their adjacent hangs fueled competition; Constable reportedly repositioned The Leaping Horse (1825) near Turner's Dido Building Carthage to rival its drama, underscoring divergent paths—Constable's precise naturalism versus Turner's chromatic intensity—yet shared commitment to landscape's autonomy.[67] Both artists' outputs, grounded in firsthand scrutiny rather than studio invention, substantiated Romantic valorization of individual genius and nature's causal forces, yielding enduring icons of English visual identity.[76]

![Ochre horse illustration from the Creswell Crags; 11000-13000 BC.[20]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/a/a4/Ochre_Horse.jpg/250px-Ochre_Horse.jpg)

![Stonehenge; 2600 BC.[21]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/f/fb/Stonehenge_Sunset_%281%29_-_geograph.org.uk_-_1626228.jpg/250px-Stonehenge_Sunset_%281%29_-_geograph.org.uk_-_1626228.jpg)

![Uffington White Horse; c. 1000 BC.[22]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/f/f3/Aerial_view_from_Paramotor_of_Uffington_White_Horse_-_geograph.org.uk_-_305467.jpg/250px-Aerial_view_from_Paramotor_of_Uffington_White_Horse_-_geograph.org.uk_-_305467.jpg)

![Winchester Hoard items; 75-25 BC.[23]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/a/aa/Winchester_Hoard_items.jpg/250px-Winchester_Hoard_items.jpg)

![Hinton St Mary Mosaic; 4th century AD.[24]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/e/e7/Hinton_St_Mary.jpg/250px-Hinton_St_Mary.jpg)

![Sutton Hoo helmet; c. 625.[39]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/7/77/Sutton.hoo.helmet.jpg/120px-Sutton.hoo.helmet.jpg)

![Lindisfarne Gospels; c. 700.[40]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/0/03/Lindisfarne_Gospels_folio_209v.jpg/120px-Lindisfarne_Gospels_folio_209v.jpg)

![Lichfield Gospels; c. 730.[41]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/8/8c/LichfieldGospelsEvangelist.jpg/120px-LichfieldGospelsEvangelist.jpg)

![Detail from the so-called Bayeux Tapestry; c. 1070s.[42]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/d/d5/Bayeux_Deense_bijl.jpg/250px-Bayeux_Deense_bijl.jpg)

![Mary Magdalen announcing the Resurrection, from the St. Albans Psalter; 1120–1145.[43]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/f/f4/Wga_12c_illuminated_manuscripts_Mary_Magdalen_announcing_the_resurrection.jpg/250px-Wga_12c_illuminated_manuscripts_Mary_Magdalen_announcing_the_resurrection.jpg)

![The Fitzwilliam Peterborough Psalter; before 1222.[44]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/a/a6/Peterborough_Psalter_c_1220-25_Mercy_and_Truth.jpg/250px-Peterborough_Psalter_c_1220-25_Mercy_and_Truth.jpg)

![The Westminster Retable; c. 1270s.[45]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/f/f7/Westminster_Retable.jpg/138px-Westminster_Retable.jpg)

![King Arthur in Matthew Paris's Flores Historiarum; 1306–1326.[46]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/2/22/StepanAngl.jpg/154px-StepanAngl.jpg)

![The Queen Mary Psalter; 1310–1320.[47]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/f/f8/Queen_Mary%27s_Psalter.jpg/120px-Queen_Mary%27s_Psalter.jpg)

![Becket's death in the Luttrell Psalter; 1320–1345.[48]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/3/30/SmrtBecketta.jpg/250px-SmrtBecketta.jpg)

![Gorleston Psalter; 14th century.[49]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/f/fd/Gorleston3.jpg/120px-Gorleston3.jpg)

![Tickhill Psalter; 14th century.[50]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/6/66/Tickhill.jpg/120px-Tickhill.jpg)

![The Wilton Diptych (right); c. 1395–1399.[51]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/9/9b/The_Wilton_Diptych_%28Right%29.jpg/120px-The_Wilton_Diptych_%28Right%29.jpg)

![Nottingham Alabaster of St Thomas Becket; 15th century.[52]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/2/21/StThomasEnthroned.jpg/250px-StThomasEnthroned.jpg)

![Stained glass at York Minster by John Thornton (fl. 1405–1433).[53]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/1/16/Seven_Churches_of_Asia_in_the_East_Window_at_York_Minster.jpg/250px-Seven_Churches_of_Asia_in_the_East_Window_at_York_Minster.jpg)

![Hoskins's miniature of Anne Boleyn (c. 1501–1536); n.d.[64]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/f/f3/AnneBoleyn56.jpg/250px-AnneBoleyn56.jpg)

![George Gower's sieve portrait of Elizabeth I; 1579.[65]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/d/db/George_Gower_Elizabeth_Sieve_Portrait_2.jpg/120px-George_Gower_Elizabeth_Sieve_Portrait_2.jpg)

![John Bettes the Younger's portrait of Elizabeth I; c. 1585.[66]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/2/20/Elizabeth_I_attrib_john_bettes_c1585_90.jpg/250px-Elizabeth_I_attrib_john_bettes_c1585_90.jpg)

![Nicholas Hilliard's Young Man Among Roses; 1587.[67]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/f/fa/Nicholas_Hilliard_-_Young_Man_Among_Roses_-_V%26A_P.163-1910.jpg/120px-Nicholas_Hilliard_-_Young_Man_Among_Roses_-_V%26A_P.163-1910.jpg)

![Isaac Oliver's A Young Man Seated Under a Tree; 1590–1595.[68]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/c/ca/Isaac_Oliver_d._%C3%84._002.jpg/120px-Isaac_Oliver_d._%C3%84._002.jpg)

![Detail of Robert Peake the Elder's procession portrait of Elizabeth I; c. 1601.[69]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/1/16/Elizabeth_I._Procession_portrait_%28detail%29.jpg/120px-Elizabeth_I._Procession_portrait_%28detail%29.jpg)

![The Chandos portrait of Shakespeare, attributed to John Taylor; 1600–1610.[70]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/3/3c/CHANDOS3.jpg/120px-CHANDOS3.jpg)

![William Larkin's portrait of Sir Francis Bacon; c. 1610.[71]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/f/ff/William_Larkin_Sir_Francis_Bacon_2.jpg/250px-William_Larkin_Sir_Francis_Bacon_2.jpg)

![Dobson's portrait of Charles II when Prince of Wales; 1644.[72]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/2/2c/Charles_II_when_Prince_of_Wales_by_William_Dobson%2C_1642.jpg/120px-Charles_II_when_Prince_of_Wales_by_William_Dobson%2C_1642.jpg)

![Edward Bower's King Charles I at his trial; 1648.[73]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/7/7f/Charles_I_at_his_trial.jpg/250px-Charles_I_at_his_trial.jpg)

![Robert Walker's portrait of diarist John Evelyn; 1648.[74]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/5/53/Walker%2C_Robert_John_-_Evelyn.jpg/120px-Walker%2C_Robert_John_-_Evelyn.jpg)

![John Michael Wright's portrait of Charles II; c. 1676.[75]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/b/bb/Charles_II_by_John_Michael_Wright.jpg/250px-Charles_II_by_John_Michael_Wright.jpg)

![John Greenhill's portrait of John Locke; c. 1672–1676.[76]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/4/4b/John_Locke_by_Greenhill.jpg/250px-John_Locke_by_Greenhill.jpg)

![Francis Barlow's Coursing the Hare; 1686.[77]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/b/b8/Coursing_the_Hare.JPG/120px-Coursing_the_Hare.JPG)

![John Riley's portrait of Samuel Pepys; c. 1690.[78]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/0/06/Samuel_Pepys_by_John_Riley_%28Yale_University_Art_Gallery%29.tif/lossy-page1-127px-Samuel_Pepys_by_John_Riley_%28Yale_University_Art_Gallery%29.tif.jpg)

![West wall of James Thornhill's Painted Hall at the Old Royal Naval College; 1707–1726.[106]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/4/45/The_west_wall_of_the_Painted_Hall_at_the_Old_Royal_Naval_College.jpg/250px-The_west_wall_of_the_Painted_Hall_at_the_Old_Royal_Naval_College.jpg)

![Richardson's portrait of Alexander Pope; c. 1736.[107]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/e/e2/Alexander_Pope_circa_1736.jpeg/250px-Alexander_Pope_circa_1736.jpeg)

![Hogarth's Marriage A-la-Mode: 2, The Tête à Tête; c. 1743.[108]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/8/8c/Marriage_A-la-Mode_2%2C_The_T%C3%AAte_%C3%A0_T%C3%AAte_-_William_Hogarth.jpg/250px-Marriage_A-la-Mode_2%2C_The_T%C3%AAte_%C3%A0_T%C3%AAte_-_William_Hogarth.jpg)

![Highmore's portrait of General James Wolfe; 1749.[109]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/a/aa/Major-General_James_Wolfe.jpg/250px-Major-General_James_Wolfe.jpg)

![Gainsborough's Mr and Mrs Andrews; c. 1750.[110]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/3/3a/Thomas_Gainsborough-Andrews.jpg/250px-Thomas_Gainsborough-Andrews.jpg)

![Arthur Devis's "conversation piece" portrait of the East India Company's Robert James and family; 1751.[111]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/3/32/Arthur_Devis_13.jpg/250px-Arthur_Devis_13.jpg)

![Francis Hayman's Robert Clive and Mir Jafar after the Battle of Plassey; 1757.[112]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/c/c4/Lord_Clive_meeting_with_Mir_Jafar_after_the_Battle_of_Plassey.jpg/250px-Lord_Clive_meeting_with_Mir_Jafar_after_the_Battle_of_Plassey.jpg)

![George Stubbs's Whistlejacket; c. 1762.[113]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/6/60/Whistlejacket_by_George_Stubbs_edit.jpg/250px-Whistlejacket_by_George_Stubbs_edit.jpg)

![Sir Joshua Reynolds's portrait of Warren Hastings; 1766–1768.[114]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/5/5f/Warren_Hastings_by_Joshua_Reynolds.jpg/250px-Warren_Hastings_by_Joshua_Reynolds.jpg)

![Joseph Wright of Derby's An Experiment on a Bird in the Air Pump; 1768.[115]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/7/73/Joseph_Wright_of_Derby_-_Experiment_with_the_Air_Pump_-_WGA25892.jpg/250px-Joseph_Wright_of_Derby_-_Experiment_with_the_Air_Pump_-_WGA25892.jpg)

![George Romney's Emma Hart in a Straw Hat; 1785.[116]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/8/8e/George_Romney_-_Emma_Hart_in_a_Straw_Hat.jpg/250px-George_Romney_-_Emma_Hart_in_a_Straw_Hat.jpg)

![Lemuel Francis Abbott's portrait of Vice-Admiral Horatio Nelson; 1797.[117]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/7/7a/Vice-Admiral_Horatio_Nelson%2C_1758-1805%2C_1st_Viscount_Nelson.jpg/250px-Vice-Admiral_Horatio_Nelson%2C_1758-1805%2C_1st_Viscount_Nelson.jpg)

![William Blake's The Ancient of Days, frontispiece to Europe a Prophecy; 1794.[118]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/3/31/Europe_a_Prophecy_copy_D_1794_British_Museum_object_1.jpg/120px-Europe_a_Prophecy_copy_D_1794_British_Museum_object_1.jpg)

![Thomas Heaphy's portrait of Palmerston; 1802.[119]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/0/03/Palmerston_1802.jpg/250px-Palmerston_1802.jpg)

![Richard Westall's Nelson in conflict with a Spanish launch, 3 July 1797; 1806.[120]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/6/6c/Nelson_at_Cadiz.jpg/250px-Nelson_at_Cadiz.jpg)

![Gillray's The Plumb-pudding in danger; 1805.[122]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/3/37/James_Gillray_-_The_Plum-Pudding_in_Danger_-_WGA08993.jpg/250px-James_Gillray_-_The_Plum-Pudding_in_Danger_-_WGA08993.jpg)

![Cruikshank's Saluting the Regent's Bomb; 1816.[123]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/9/99/Saluting_the_Regent%27s_Bomb.jpg/250px-Saluting_the_Regent%27s_Bomb.jpg)

![Lawrence's post-Waterloo Portrait of the Duke of Wellington; 1816.[124]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/d/d2/Sir_Arthur_Wellesley_Duke_of_Wellington.jpg/120px-Sir_Arthur_Wellesley_Duke_of_Wellington.jpg)

![George Arnald's The Destruction of 'L'Orient' at the Battle of the Nile, 1 August 1798; 1825–27.[125]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/0/0a/The_Battle_of_the_Nile.jpg/250px-The_Battle_of_the_Nile.jpg)

![Phillips's Lord Byron in Albanian Dress; c. 1835.[126]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/e/ee/Lord_Byron_in_Albanian_dress.jpg/250px-Lord_Byron_in_Albanian_dress.jpg)

![Turner's The Fighting Temeraire; 1839.[127]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/7/7b/Turner_temeraire.jpg/250px-Turner_temeraire.jpg)

![Millais's Ophelia; 1851–1852.[128]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/4/41/Ophelia_john_everett_millais.JPG/250px-Ophelia_john_everett_millais.JPG)

![Holman Hunt's Our English Coasts; 1852.[129]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/c/c3/Hunt_english_coasts.jpg/250px-Hunt_english_coasts.jpg)

![Ford Madox Brown's The Last of England; 1852–1855.[130]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/f/f4/Ford_Madox_Brown%2C_The_last_of_England.jpg/250px-Ford_Madox_Brown%2C_The_last_of_England.jpg)

![William Powell Frith's portrait of Dickens; 1859.[131]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/d/db/Charles_Dickens_by_Frith_1859.jpg/250px-Charles_Dickens_by_Frith_1859.jpg)

![John Ruskin, leading English art critic of the Victorian era; 1867.[132]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/c/c2/John_Ruskin_CDV_by_Elliott_%26_Fry%2C_1867.jpg/120px-John_Ruskin_CDV_by_Elliott_%26_Fry%2C_1867.jpg)