Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Art of the United Kingdom

View on Wikipedia

The art of the United Kingdom refers to all forms of visual art in or associated with the country since the formation of the Kingdom of Great Britain in 1707 and encompasses English art, Scottish art, Welsh art and Irish art, and forms part of Western art history. During the 18th century, Britain began to reclaim the leading place England had previously played in European art during the Middle Ages, being especially strong in portraiture and landscape art.

Increased British prosperity at the time led to a greatly increased production of both fine art and the decorative arts, the latter often being exported. The Romantic period resulted from very diverse talents, including the painters William Blake, J. M. W. Turner, John Constable and Samuel Palmer. The Victorian period saw a great diversity of art, and a far bigger quantity created than before. Much Victorian art is now out of critical favour, with interest concentrated on the Pre-Raphaelites and the innovative movements at the end of the 18th century.

The training of artists, which had long been neglected, began to improve in the 18th century through private and government initiatives, and greatly expanded in the 19th century. Public exhibitions and the later opening of museums brought art to a wider public, especially in London. In the 19th century publicly displayed religious art once again became popular after a virtual absence since the Reformation, and, as in other countries, movements such as the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood and the Glasgow School contended with established Academic art.

The British contribution to early Modernist art was relatively small, but since World War II British artists have made a considerable impact on Contemporary art, especially with figurative work, and Britain remains a key centre of an increasingly globalised art world.[citation needed]

Background

[edit]

The oldest surviving British art includes Stonehenge from around 2600 BC, and tin and gold works of art produced by the Beaker people from around 2150 BC. The La Tène style of Celtic art reached the British Isles rather late, no earlier than about 400 BC, and developed a particular "Insular Celtic" style seen in objects such as the Battersea Shield, and a number of bronze mirror-backs decorated with intricate patterns of curves, spirals and trumpet-shapes. Only in the British Isles can Celtic decorative style be seen to have survived throughout the Roman period, as shown in objects like the Staffordshire Moorlands Pan and the resurgence of Celtic motifs, now blended with Germanic interlace and Mediterranean elements, in Christian Insular art. This had a brief but spectacular flowering in all the countries that now form the United Kingdom in the 7th and 8th centuries, in works such as the Book of Kells and Book of Lindisfarne. The Insular style was influential across Northern Europe, and especially so in later Anglo-Saxon art, although this received new Continental influences.

The English contribution to Romanesque art and Gothic art was considerable, especially in illuminated manuscripts and monumental sculpture for churches, though the other countries were now essentially provincial, and in the 15th century Britain struggled to keep up with developments in painting on the Continent. A few examples of top-quality English painting on walls or panel from before 1500 have survived, including the Westminster Retable, The Wilton Diptych and some survivals from paintings in Westminster Abbey and the Palace of Westminster.[1]

The Protestant Reformations of England and Scotland were especially destructive of existing religious art, and the production of new work virtually ceased. The Artists of the Tudor Court were mostly imported from Europe, setting a pattern that would continue until the 18th century. The portraiture of Elizabeth I ignored contemporary European Renaissance models to create iconic images that border on naive art. The portraitists Hans Holbein and Anthony van Dyck were the most distinguished and influential of a large number of artists who spent extended periods in Britain, generally eclipsing local talents like Nicolas Hilliard, the painter of portrait miniatures, Robert Peake the elder, William Larkin, William Dobson, and John Michael Wright, a Scot who mostly worked in London.[2]

Landscape painting was as yet little developed in Britain at the time of the Union, but a tradition of marine art had been established by the father and son both called Willem van de Velde, who had been the leading Dutch maritime painters until they moved to London in 1673, in the middle of the Third Anglo-Dutch War.[3]

History

[edit]Early 18th century

[edit]

The so-called Acts of Union 1707 came in the middle of the long period of domination in London of Sir Godfrey Kneller, a German portraitist who had eventually succeeded as principal court painter the Dutch Sir Peter Lely, whose style he had adopted for his enormous and formulaic output, of greatly varying quality, which was itself repeated by an army of lesser painters. His counterpart in Edinburgh, Sir John Baptist Medina, born in Brussels to Spanish parents, had died just before the Union took place, and was one of the last batch of Scottish knights to be created. Medina had first worked in London, but in mid-career moved to the less competitive environment of Edinburgh, where he dominated portraiture of the Scottish elite. However, after the Union the movement was to be all in the other direction, and Scottish aristocrats resigned themselves to paying more to have their portraits painted in London, even if by Scottish painters such as Medina's pupil William Aikman, who moved down in 1723, or Allan Ramsay.[4]

There was an alternative, more direct, tradition in British portraiture to that of Lely and Kneller, tracing back to William Dobson and the German or Dutch Gerard Soest, who trained John Riley, to whom only a few works are firmly attributed and who in turn trained Jonathan Richardson, a fine artist who trained Thomas Hudson who trained Joshua Reynolds and Joseph Wright of Derby. Richardson also trained the most notable Irish portraitist of the period, Charles Jervas who enjoyed social and financial success in London despite his clear limitations as an artist.[5]

An exception to the dominance of the "lower genres" of painting was Sir James Thornhill (1675/76–1734) who was the first and last significant English painter of huge Baroque allegorical decorative schemes, and the first native painter to be knighted. His best-known work is at Greenwich Hospital, Blenheim Palace and the cupola of Saint Paul's Cathedral, London. His drawings show a taste for strongly drawn realism in the direction his son-in-law William Hogarth was to pursue, but this is largely overridden in the finished works, and for Greenwich he took to heart his careful list of "Objections that will arise from the plain representation of the King's landing as it was in fact and in the modern way and dress" and painted a conventional Baroque glorification.[6] Like Hogarth, he played the nationalist card in promoting himself, and eventually beat Sebastiano Ricci to enough commissions that in 1716 he and his team retreated to France, Giovanni Antonio Pellegrini having already left in 1713. Once the other leading foreign painters of allegoric schemes, Antonio Verrio and Louis Laguerre, had died in 1707 and 1721 respectively, Thornhill had the field to himself, although by the end of his life commissions for grand schemes had dried up from changes in taste.[7]

From 1714 the new Hanoverian dynasty conducted a far less ostentatious court, and largely withdrew from patronage of the arts, other than the necessary portraits. Fortunately, the booming British economy was able to supply aristocratic and mercantile wealth to replace the court, above all in London.[8]

William Hogarth was a great presence in the second quarter of the century, whose art was successful in achieving a particular English character, with vividly moralistic scenes of contemporary life, full of both satire and pathos, attuned to the tastes and prejudices of the Protestant middle-class, who bought the engraved versions of his paintings in huge numbers. Other subjects were only issued as prints, and Hogarth was both the first significant British printmaker, and still the best known. Many works were series of four or more scenes, of which the best known are: A Harlot's Progress and A Rake's Progress from the 1730s and Marriage à-la-mode from the mid-1740s. In fact, although he only once briefly left England and his own propaganda asserted his Englishness and often attacked the Old Masters, his background in printmaking, more closely aware of Continental art than most British painting, and apparently his ability to quickly absorb lessons from other painters, meant that he was more aware of, and made more use of, Continental art than most of his contemporaries.

Like many later painters Hogarth wanted above all to achieve success at history painting in the Grand Manner, but his few attempts were not successful and are now little regarded. His portraits were mostly of middle-class sitters shown with an apparent realism that reflected both sympathy and flattery, and included some in the fashionable form of the conversation piece, recently introduced from France by Philippe Mercier, which was to remain a favourite in Britain, taken up by artists such as Francis Hayman, though usually abandoned once an artist could get good single figure commissions.[9]

There was a recognition that, even more than the rest of Europe given the lack of British artists, the training of artists needed to be extended beyond the workshop of established masters, and various attempts were made to set up academies, starting with Kneller in 1711, with the help of Pellegrini, in Great Queen Street. The academy was taken over by Thornhill in 1716, but seems to have become inactive by the time John Vanderbank and Louis Chéron set up their own academy in 1720. This did not last long, and in 1724/5 Thornhill tried again in his own house, with little success. Hogarth inherited the equipment for this, and used it to start the St. Martin's Lane Academy in 1735, which was the most enduring, eventually being absorbed by the Royal Academy in 1768. Hogarth also helped solve the problem of a lack of exhibition venues in London, arranging for shows at the Foundling Hospital from 1746.[10]

The Scottish portraitist Allan Ramsay worked in Edinburgh before moving to London by 1739. He made visits of three years to Italy at the beginning and end of his career, and anticipated Joshua Reynolds in bringing a more relaxed version of "Grand Manner" to British portraiture, combined with very sensitive handling in his best work, which is generally agreed to have been of female sitters. His main London rival in the mid-century, until Reynolds made his reputation, was Reynold's master, the stodgy Thomas Hudson.[11]

John Wootton, active from about 1714 to his death in 1765, was the leading sporting painter of his day, based in the capital of English horse racing at Newmarket, and producing large numbers of portraits of horses and also battle scenes and conversation pieces with a hunting or riding setting. He had begun life as a page to the family of the Dukes of Beaufort, who in the 1720s sent him to Rome, where he acquired a classicising landscape style based on that of Gaspard Dughet and Claude, which he used in some pure landscape paintings, as well as views of country houses and equine subjects. This introduced an alternative to the various Dutch and Flemish artists who had previously set the prevailing landscape style in Britain, and through intermediary artists such as George Lambert, the first British painter to base a career on landscape subjects, was to greatly influence other British artists such as Gainsborough.[12] Samuel Scott was the best of the native marine and townscape artists, though in the latter specialisation he could not match the visiting Canaletto, who was in England from nine years from 1746, and whose Venetian views were a favourite souvenir of the Grand Tour.[13]

-

Sir John Rushout, 4th Baronet, by Godfrey Kneller, 1716

-

William Hogarth, Marriage A-la-Mode (Hogarth), c. 1743-45

The antiquary and engraver George Vertue was a figure in the London art scene for most of the period, and his copious notebooks were adapted and published in the 1760s by Horace Walpole as Some Anecdotes of Painting in England, which remains a principal source for the period.[14]

From his arrival in London in 1720, the Flemish sculptor John Michael Rysbrack was the leader in his field until the arrival in 1730 of Louis-François Roubiliac who had a Rococo style which was highly effective in busts and small figures, though by the following decade he was also commissioned for larger works. He also produced models for the Chelsea porcelain factory founded in 1743, a private enterprise which sought to compete with Continental factories mostly established by rulers. Roubiliac's style formed that of the leading native sculptor Sir Henry Cheere, and his brother John who specialised in statues for gardens.[15]

The strong London silversmithing trade was dominated by the descendants of Huguenot refugees like Paul de Lamerie, Paul Crespin, Nicholas Sprimont, and the Courtauld family, as well as Georges Wickes. Orders were received from as far away as the courts of Russia and Portugal, though English styles were still led by Paris.[16] The manufacture of silk at Spitalfields in London was also a traditional Huguenot business, but from the late 1720s silk design was dominated by the surprising figure of Anna Maria Garthwaite, a parson's daughter from Lincolnshire who emerged at the age of 40 as a designer of largely floral patterns in Rococo styles.[17]

Unlike in France and Germany, the English adoption of the Rococo style was patchy rather than whole-hearted, and there was resistance to it on nationalist grounds, led by Richard Boyle, 3rd Earl of Burlington and William Kent, who promoted styles in interior design and furniture to match the Palladianism of the architecture they produced together, also beginning the influential British tradition of the landscape garden,[18] according to Nikolaus Pevsner "the most influential of all English innovations in art".[19] The French-born engraver Hubert-François Gravelot, in London from 1732 to 1745, was a key figure in importing Rococo taste in book illustrations and ornament prints for craftsmen to follow.[20]

Late 18th century

[edit]In the modern popular mind, English art from about 1750–1790 — today referred to as the "classical age" of English painting — was dominated by Sir Joshua Reynolds (1723–1792), George Stubbs (1724–1806), Thomas Gainsborough (1727–1788) and Joseph Wright of Derby (1734–1797). At the time Reynolds was considered the dominant figure, Gainsborough was very highly reputed, but Stubbs was seen as a mere painter of animals and viewed as far a less significant figure than many other painters that are today little-known or forgotten. The period saw continued rising prosperity for Britain and British artists: "By the 1780s English painters were among the wealthiest men in the country, their names familiar to newspaper readers, their quarrels and cabals the talk of the town, their subjects known to everyone from the displays in the print-shop windows", according to Gerald Reitlinger.[21]

Reynolds returned from a long visit to Italy in 1753, and very quickly established a reputation as the most fashionable London portraitist, and before long as a formidable figure in society;, the public leader of the arts in Britain. He had studied both classical and modern Italian art, and his compositions discreetly re-use models seen on his travels. He could convey a wide range of moods and emotions, whether heroic military men or very young women, and often to unite background and figure in a dramatic way.[22]

The Society for the encouragement of Arts, Manufactures & Commerce had been founded in 1754, principally to provide a location for exhibitions. In 1761 Reynolds was a leader in founding the rival Society of Artists of Great Britain, where the artists had more control. This continued until 1791, despite the founding of the Royal Academy of Arts in 1768, which immediately became both the most important exhibiting organisation and the most important school in London. Reynolds was its first President, holding the office until his death in 1792. His published Discourses, first delivered to the students, were regarded as the first major writing on art in English, and set out the aspiration for a style to match the classical grandeur of classical sculpture and High Renaissance painting.[23]

After the academy was established, Reynolds' portraits became more overly classicising, and often more distant, until in the late 1770s he returned to a more intimate style, perhaps influenced by the success of Thomas Gainsborough,[24] who only settled in London in 1773, after working in Ipswich and then Bath. While Reynolds' practice of aristocratic portraits seem exactly matched to his talents, Gainsborough, if not forced to follow the market for his work, might well have developed as a pure landscape painter, or a portraitist in the informal style of many of his portraits of his family. He continued to paint pure landscapes, largely for pleasure until his later years; full recognition of his landscapes came only in the 20th century. His main influences were French in his portraits and Dutch in his landscapes, rather than Italian, and he is famous for the brilliant light touch of his brushwork.[25]

George Romney also became prominent in about 1770 and was active until 1799, though with a falling-off in his last years. His portraits are mostly characterful but flattering images of dignified society figures, but he developed an obsession with the flighty young Emma Hamilton from 1781, painting her about sixty times in more extravagant poses.[26] His work was especially sought after by American collectors in the early 20th century and many are now in American museums.[27] By the end of the period this generation had been succeeded by younger portraitists including John Hoppner, Sir William Beechey and the young Gilbert Stuart, who only realised his mature style after he returned to America.[28]

The Welsh painter Richard Wilson returned to London from seven years in Italy in 1757, and over the next two decades developed a "sublime" landscape style adapting the Franco-Italian tradition of Claude and Gaspard Dughet to British subjects. Though much admired, like those of Gainsborough his landscapes were hard to sell, and he sometimes resorted, as Reynolds complained, to the common stratagem of turning them into history paintings by adding a few small figures, which doubled their price to about £80.[29] He continued to paint scenes set in Italy, as well as England and Wales, and his death in 1782 came just as large numbers of artists began to travel to Wales, and later the Lake District and Scotland in search of mountainous views, both for oil paintings and watercolours which were now starting their long period of popularity in Britain, both with professionals and amateurs. Paul Sandby, Francis Towne, John Warwick Smith, and John Robert Cozens were among the leading specialist painters and the clergyman and amateur artist William Gilpin was an important writer who stimulated the popularity of amateur painting of the picturesque, while the works of Alexander Cozens recommended forming random ink blots into landscape compositions—even Constable tried this technique.[30]

History painting in the grand manner continued to be the most prestigious form of art, though not the easiest to sell, and Reynolds made several attempts at it, as unsuccessful as Hogarth's. The unheroic nature of modern dress was seen as a major obstacle in the depiction of contemporary scenes, and the Scottish gentleman-artist and art dealer Gavin Hamilton preferred classical scenes as well as painting some based on his Eastern travels, where his European figures by-passed the problem by wearing Arab dress. He spent most of his adult life based in Rome and had at least as much influence on Neo-Classicism in Europe as in Britain. The Irishman James Barry was an influence on Blake but had a difficult career, and spent years on his cycle The Progress of Human Culture in the Great Room of the Royal Society of Arts. The most successful history painters, who were not afraid of buttons and wigs, were both Americans settled in London: Benjamin West and John Singleton Copley, though one of his most successful works Watson and the Shark (1778) was able to mostly avoid them, showing a rescue from drowning.

Smaller scale subjects from literature were also popular, pioneered by Francis Hayman, one of the first to paint scenes from Shakespeare, and Joseph Highmore, with a series illustrating the novel Pamela. At the end of the period the Boydell Shakespeare Gallery was an ambitious project for paintings, and prints after them, illustrating "the Bard", as he had now become, while exposing the limitations of contemporary English history painting.[31] Joseph Wright of Derby was mainly a portrait painter who also was one of the first artists to depict the Industrial Revolution, as well as developing a cross between the conversation piece and history painting in works like An Experiment on a Bird in the Air Pump (1768) and A Philosopher Lecturing on the Orrery (c. 1766), which like many of his works are lit only by candlelight, giving a strong chiaroscuro effect.[32]

Paintings recording scenes from the theatre were another subgenre, painted by the German Johann Zoffany among others. Zoffany painted portraits and conversation pieces, who also spent over two years in India, painting the English nabobs and local scenes, and the expanding British Empire played an increasing role in British art.[33] Training in art was considered a useful skill in the military for sketch maps and plans, and many British officers made the first Western images, often in watercolour, of scenes and places around the world. In India, the Company style developed as a hybrid form between Western and Indian art, produced by Indians for a British market.

Thomas Rowlandson produced watercolours and prints satirising British life, but mostly avoided politics. The master of the political caricature, sold individually by print shops (often acting as publishers also), either hand-coloured or plain, was James Gillray.[34] The emphasis on portrait-painting in British art was not entirely due to the vanity of the sitters. There was a large collector's market for portrait prints, mostly reproductions of paintings, which were often mounted in albums. From the mid-century there was a great growth in the expensive but more effective reproductions in mezzotint, of portraits and other paintings, with special demand from collectors for early proof states "before letter" (that is, before the inscriptions were added), which the printmakers obligingly printed off in growing numbers.[35]

This period marked one of the high points in British decorative arts. Around the mid-century many porcelain factories opened, including Bow in London, and in the provinces Lowestoft, Worcester, Royal Crown Derby, Liverpool, and Wedgwood, with Spode following in 1767. Most were started as small concerns, with some lasting only a few decades while others still survive today. By the end of the period British porcelain services were being commissioned by foreign royalty and the British manufacturers were especially adept at pursuing the rapidly expanding international middle-class market, developing bone china and transfer-printed wares as well as hand-painted true porcelain.[36]

The three leading furniture makers, Thomas Chippendale (1718–1779), Thomas Sheraton (1751–1806) and George Hepplewhite (1727?–1786) had varied styles and have achieved the lasting fame they have mainly as the authors of pattern books used by other makers in Britain and abroad. In fact it is far from clear if the last two named ever ran actual workshops, though Chippendale certainly was successful in this and in what we now call interior design; unlike France Britain had abandoned its guild system, and Chippendale was able to employ specialists in all the crafts needed to complete a redecoration.[37] During the period Rococo and Chinoiserie gave way to Neo-Classicism, with the Scottish architect and interior designer Robert Adam (1728–1792) leading the new style.

-

Sir Joshua Reynolds, Self-portrait, aged about 24 c. 1747-9

-

George Stubbs, Whistlejacket, c. 1762

-

The children of Granville Leveson-Gower, 1st Marquess of Stafford (1776–7)]

-

Sir Joshua Reynolds, The Ladies Waldegrave, 1780–81

-

Sir Joshua Reynolds, The Age of Innocence, 1785–88

19th century and the Romantics

[edit]

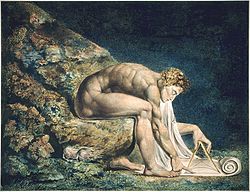

The late 18th century and the early 19th century characterised by the Romantic movement in British art includes Joseph Wright of Derby, James Ward, Samuel Palmer, Richard Parkes Bonington, John Martin and was perhaps the most radical period in British art, also producing William Blake (1757–1827), John Constable (1776–1837) and J. M. W. Turner (1775–1851), the later two being arguably the most internationally influential of all British artists.[38][39] Turner's style, based on the Italianate tradition although he never saw Italy until in his forties, passed through considerable changes before his final wild, almost abstract, landscapes that explored the effects of light, and were a profound influence on the Impressionists and other later movements.[40] Constable normally painted pure landscapes with at most a few genre figures, in a style based on Northern European traditions, but, like Turner, his "six-footers" were intended to make as striking an impact as any history painting.[41] They were carefully prepared using studies and full-size oil sketches,[42] whereas Turner was notorious for finishing his exhibition pieces when they were already hanging for show, freely adjusting them to dominate the surrounding works in the tightly packed hangs of the day.[43]

Blake's visionary style was a minority taste in his lifetime, but influenced the younger group of "Ancients" of Samuel Palmer, John Linnell, Edward Calvert and George Richmond, who gathered in the country at Shoreham, Kent in the 1820s, producing intense and lyrical pastoral idylls in conditions of some poverty. They went on to more conventional artistic careers and Palmer's early work was entirely forgotten until the early 20th century.[44] Blake and Palmer became a significant influence on modernist artists of the 20th century seen (among others) in the painting of British artists such as Dora Carrington,[45] Paul Nash and Graham Sutherland.[46] Blake also had an enormous influence on the beat poets of the 1950s and the counterculture of the 1960s.[47]

Thomas Lawrence was already a leading portraitist by the start of the 20th century, and able to give a Romantic dash to his portraits of high society, and the leaders of Europe gathered at the Congress of Vienna after the Napoleonic Wars. Henry Raeburn was the most significant portraitist since the Union to remain based in Edinburgh throughout his career, an indication of increasing Scottish prosperity.[48] But David Wilkie took the traditional road south, achieving great success with subjects of country life and hybrid genre and history scenes such as The Chelsea Pensioners reading the Waterloo Dispatch (1822).[49]

John Flaxman was the most thorough-going neo-classical English artist. Beginning as a sculptor, he became best known for his many spare "outline drawings" of classical scenes, often illustrating literature, which were reproduced as prints. These imitated the effects of the classical-style reliefs he also produced. The German-Swiss Henry Fuseli also produced work in a linear graphic style, but his narrative scenes, often from English literature, were intensely Romantic and highly dramatic.[50]

-

William Blake, Newton, 1805

-

John Constable, The White Horse, 1819

-

J. M. W. Turner, The Slave Ship, 1840

-

J. M. W. Turner, The Rigi, 1842

Victorian art

[edit]

The Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood (PRB) achieved considerable influence after its foundation in 1848 with paintings that concentrated on religious, literary, and genre subjects executed in a colourful and minutely detailed style, rejecting the loose painterly brushwork of the tradition represented by "Sir Sloshua" Reynolds. PRB artists included John Everett Millais, William Holman Hunt, Dante Gabriel Rossetti, and Ford Madox Brown (never officially a member), and figures such as Edward Burne-Jones and John William Waterhouse were later much influenced by aspects of their ideas, as was the designer William Morris. Morris advocated a return to hand-craftsmanship in the decorative arts over the industrial manufacture that was rapidly being applied to all crafts. His efforts to make beautiful objects affordable (or even free) for everyone led to his wallpaper and tile designs defining the Victorian aesthetic and instigating the Arts and Crafts movement.

The Pre-Raphaelites, like Turner, were supported by the authoritative art critic John Ruskin, himself a fine amateur artist. For all their technical innovation, they were both traditional and Victorian in their adherence to the history painting as the highest form of art, and their subject matter was thoroughly in tune with Victorian taste, and indeed "everything that the publishers of steel engravings welcomed",[51] enabling them to merge easily into the mainstream in their later careers.[52]

While the Pre-Raphaelites had a turbulent and divided reception, the most popular and expensive painters of the period included Edwin Landseer, who specialised in sentimental animal subjects, which were favourites of Queen Victoria and Prince Albert. In the later part of the century artists could earn large sums from selling the reproduction rights of their paintings to print publishers, and works of Landseer, especially his Monarch of the Glen (1851), a portrait of a Highland stag, were among the most popular. Like Millais' Bubbles (1886) it was used on packaging and advertisements for decades, for brands of whisky and soap respectively.[53]

During the late Victorian era in Britain the academic paintings, some enormously large, of Lord Leighton and the Dutch-born Lawrence Alma-Tadema were enormously popular, both often featuring lightly clad beauties in exotic or classical settings, while the allegorical works of G. F. Watts matched the Victorian sense of high purpose. The classical ladies of Edward Poynter and Albert Moore wore more clothes and met with rather less success. William Powell Frith painted highly detailed scenes of social life, typically including all classes of society, that include comic and moral elements and have an acknowledged debt to Hogarth, though tellingly different from his work.[54]

For all such artists the Royal Academy Summer Exhibition was an essential platform, reviewed at huge length in the press, which often alternated ridicule and extravagant praise in discussing works. The ultimate, and very rare, accolade was when a rail had to be put in front of a painting to protect it from the eager crowd; up to 1874 this had only happened to Wilkie's Chelsea Pensioners, Frith's The Derby Day and Salon d'Or, Homburg and Luke Filde's The Casual Ward (see below).[55] A great number of artists laboured year after year in the hope of a hit there, often working in manners to which their talent was not really suited, a trope exemplified by the suicide in 1846 of Benjamin Haydon, a friend of Keats and Dickens and a better writer than painter, leaving his blood splashed over his unfinished King Alfred and the First British Jury.[56]

British history was a very common subject, with the Middle Ages, Elizabeth I, Mary, Queen of Scots and the English Civil War especially popular sources for subjects. Many painters mentioned elsewhere painted historical subjects, including Millais (The Boyhood of Raleigh and many others), Ford Madox Brown (Cromwell on his Farm), David Wilkie, Watts and Frith, and West, Bonington and Turner in earlier decades. The London-based Irishman Daniel Maclise and Charles West Cope painted scenes for the new Palace of Westminster. Lady Jane Grey was, like Mary Queen of Scots, a female whose sufferings attracted many painters, though none quite matched The Execution of Lady Jane Grey, one of many British historical subjects by the Frenchman Paul Delaroche.[57] Painters prided themselves on the increasing accuracy of their period settings in terms of costume and objects, studying the collections of the new Victoria and Albert Museum and books, and scorning the breezy approximations of earlier generations of artists.[58]

Victorian painting developed the Hogarthian social subject, packed with moralising detail, and the tradition of illustrating scenes from literature, into a range of types of genre painting, many with only a few figures, others large and crowded scenes like Frith's best-known works. Holman Hunt's The Awakening Conscience (1853) and Augustus Egg's set of Past and Present (1858) are of the first type, both dealing with "Fallen woman", a perennial Victorian concern. As Peter Conrad points out, these were paintings designed to be read like novels, whose meaning emerged after the viewer had done the work of deciphering it.[59] Other "anecdotal" scenes were lighter in mood, tending towards being captionless Punch cartoons.

Towards the end of the 19th century the problem picture left the details of the narrative action deliberately ambiguous, inviting the viewer to speculate on it using the evidence in front of them, but not supplying a final answer (artists learned to smile enigmatically when asked). This sometimes provoked discussion on sensitive social issues, typically involving women, that might have been hard to raise directly. They were enormously popular; newspapers ran competitions for readers to supply the meaning of the painting.[60]

Many artists participated in the revival of original artistic printmaking usually known as the etching revival, although prints in many other techniques were also made. This began in the 1850s and continued until the fallout from the 1929 Wall Street Crash brought about a collapse in the very high prices that the most fashionable artists had been achieving.

British Orientalism, though not as common as in France at the same period, had many specialists, including John Frederick Lewis, who lived for nine years in Cairo, David Roberts, a Scot who made lithographs of his travels in the Middle East and Italy, the nonsense writer Edward Lear, a continual traveller who reached as far as Ceylon, and Richard Dadd. Holman Hunt also travelled to Palestine to obtain authentic settings for his Biblical pictures. The Frenchman James Tissot, who fled to London after the fall of the Paris Commune, divided his time between scenes of high society social events and a huge series of Biblical illustrations, made in watercolour for reproductive publication.[61] Frederick Goodall specialised in scenes of Ancient Egypt.

Larger paintings concerned with the social conditions of the poor tended to concentrate on rural scenes, so that the misery of the human figures was at least offset by a landscape. Painters of these included Frederick Walker, Luke Fildes (although he made his name in 1874 with Applicants for Admission to a Casual Ward- see above), Frank Holl, George Clausen, and the German Hubert von Herkomer.[64]

William Bell Scott, a friend of the Rossettis, painted historical scenes and other types of work, but was also one of the few artists to depict scenes from heavy industry. His memoirs are a useful source for the period, and he was one of several artists to be employed for a period in the greatly expanded system of government art schools, which were driven by the administrator Henry Cole (the inventor of the Christmas card) and employed Richard Redgrave, Edward Poynter, Richard Burchett, the Scottish designer Christopher Dresser and many others. Burchett was headmaster of the "South Kensington Schools", now the Royal College of Art, which gradually replaced the Royal Academy School as the leading British art school, though around the start of the 20th century the Slade School of Fine Art produced many of the forward-looking artists.[65]

The Royal Academy was initially by no means as conservative and restrictive as the Paris Salon, and the Pre-Raphaelites had most of their submissions for exhibition accepted, although like everyone else they complained about the positions their paintings were given. They were especially welcomed at the Liverpool Academy of Arts, one of the largest regional exhibiting organisations; the Royal Scottish Academy was founded in 1826 and opened its grand new building in the 1850s. There were alternative London locations like the British Institution, and as the conservatism of the Royal Academy gradually increased, despite the efforts of Lord Leighton when President, new spaces opened, notably the Grosvenor Gallery in Bond Street, from 1877, which became the home of the Aesthetic Movement. The New English Art Club exhibited from 1885 many artists with Impressionist tendencies, initially using the Egyptian Hall, opposite the Royal Academy, which also hosted many exhibitions of foreign art. The American portrait painter John Singer Sargent (1856–1925), spent most of his working career in Europe and he maintained his studio in London (where he died) from 1886 to 1907.

Alfred Sisley, who was French by birth but had British nationality, painted in France as one of the Impressionists; Walter Sickert and Philip Wilson Steer at the start of their careers were also strongly influenced, but despite the dealer Paul Durand-Ruel bringing many exhibitions to London, the movement made little impact in England until decades later.[66] Some members of the Newlyn School of landscapes and genre scenes adopted a quasi-Impressionist technique while others used realist or more traditional levels of finish.

The late 19th century also saw the Decadent movement in France and the British Aesthetic movement. The British-based American painter James Abbott McNeill Whistler, Aubrey Beardsley, and the former Pre-Raphaelites Dante Gabriel Rossetti, and Edward Burne-Jones are associated with those movements, with late Burne-Jones and Beardsley both being admired abroad and representing the nearest British approach to European Symbolism.[67] In 1877 James McNeill Whistler sued the art critic John Ruskin for libel after the critic condemned his painting Nocturne in Black and Gold: The Falling Rocket. Ruskin accused Whistler of "ask[ing] two hundred guineas for throwing a pot of paint in the public's face."[62][63] The jury reached a verdict in favour of Whistler but awarded him only a single farthing in nominal damages, and the court costs were split.[68] The cost of the case, together with huge debts from building his residence ("The White House" in Tite Street, Chelsea, designed with E. W. Godwin, 1877–8), bankrupted Whistler by May 1879,[69] resulting in an auction of his work, collections, and house. Stansky[70] notes the irony that the Fine Art Society of London, which had organised a collection to pay for Ruskin's legal costs, supported him in etching "the stones of Venice" (and in exhibiting the series in 1883) which helped recoup Whistler's costs.

Scottish art was now regaining an adequate home market, allowing it to develop a distinctive character, of which the "Glasgow Boys" were one expression, straddling Impressionism in painting, and Art Nouveau, Japonism and the Celtic Revival in design, with the architect and designer Charles Rennie Mackintosh now their best-known member. Painters included Thomas Millie Dow, George Henry, Joseph Crawhall and James Guthrie.

New printing technology brought a great expansion in book illustration with illustrations for children's books providing much of the best remembered work of the period. Specialized artists included Randolph Caldecott, Walter Crane, Kate Greenaway and, from 1902, Beatrix Potter.

The experience of military, political and economic power from the rise of the British Empire, led to a very specific drive in artistic technique, taste and sensibility in the United Kingdom.[71] British people used their art "to illustrate their knowledge and command of the natural world", whilst the permanent settlers in British North America, Australasia, and South Africa "embarked upon a search for distinctive artistic expression appropriate to their sense of national identity".[71] The empire has been "at the centre, rather than in the margins, of the history of British art".[72]

The enormous variety and massive production of the various forms of British decorative art during the period are too complex to be easily summarised. Victorian taste, until the various movements of the last decades, such as Arts and Crafts, is generally poorly regarded today, but much fine work was produced, and much money made. Both William Burges and Augustus Pugin were architects committed to the Gothic Revival, who expanded into designing furniture, metalwork, tiles and objects in other media. There was an enormous boom in re-Gothicising the fittings of medieval churches, and fitting out new ones in the style, especially with stained glass, an industry revived from effective extinction. The revival of furniture painted with images was a particular feature at the top end of the market.[73]

From its opening in 1875 the London department store Liberty & Co. was especially associated with imported Far Eastern decorative items and British goods in the new styles of the end of the 19th century. Charles Voysey was an architect who also did much design work in textiles, wallpaper furniture and other media, bringing the Arts and Crafts movement into Art Nouveau and beyond; he continued to design into the 1920s.[74] A. H. Mackmurdo was a similar figure.

20th century

[edit]

In many respects, the Victorian era continued until the outbreak of World War I in 1914, and the Royal Academy became increasingly ossified; the unmistakably late Victorian figure of Frank Dicksee was appointed president in 1924. In photography Pictorialism aimed to achieve artistic indeed painterly effects; The Linked Ring contained the leading practitioners. The American John Singer Sargent was the most successful London portraitist at the start of the 20th century, with John Lavery, Augustus John and William Orpen rising figures. John's sister Gwen John lived in France, and her intimate portraits were relatively little appreciated until decades after her death. British attitudes to modern art were "polarized" at the end of the 19th century.[75] Modernist movements were both cherished and vilified by artists and critics; Impressionism was initially regarded by "many conservative critics" as a "subversive foreign influence", but became "fully assimilated" into British art during the early-20th century.[75] The Irish artist Jack Butler Yeats (1871–1957), was based in Dublin, at once a romantic painter, a symbolist and an expressionist.

Vorticism was a brief coming together of a number of Modernist artists in the years immediately before 1914; members included Wyndham Lewis, the sculptor Sir Jacob Epstein, David Bomberg, Malcolm Arbuthnot, Lawrence Atkinson, the American photographer Alvin Langdon Coburn, Frederick Etchells, the French sculptor Henri Gaudier-Brzeska, Cuthbert Hamilton, Christopher Nevinson, William Roberts, Edward Wadsworth, Jessica Dismorr, Helen Saunders, and Dorothy Shakespear. The early 20th century also includes The Sitwells artistic circle and the Bloomsbury Group, a group of mostly English writers, intellectuals, philosophers and artists, including painter Dora Carrington, painter and art critic Roger Fry, art critic Clive Bell, painter Vanessa Bell, painter Duncan Grant among others. Although very fashionable at the time, their work in the visual arts looks less impressive today.[76] British modernism was to remain somewhat tentative until after World War II, though figures such as Ben Nicholson kept in touch with European developments.

Walter Sickert and the Camden Town Group developed an English style of Impressionism and Post-Impressionism with a strong strand of social documentary, including Harold Gilman, Spencer Frederick Gore, Charles Ginner, Robert Bevan, Malcolm Drummond and Lucien Pissarro (the son of French Impressionist painter Camille Pissarro).[77] Where their colouring is often notoriously drab, the Scottish Colourists indeed mostly used bright light and colour; some, like Samuel Peploe and John Duncan Fergusson, were living in France to find suitable subjects.[78] They were initially inspired by Sir William McTaggart (1835–1910), a Scottish landscape painter associated with Impressionism.

The reaction to the horrors of the First World War prompted a return to pastoral subjects as represented by Paul Nash and Eric Ravilious, mainly a printmaker. Stanley Spencer painted mystical works, as well as landscapes, and the sculptor, printmaker and typographer Eric Gill produced elegant simple forms in a style related to Art Deco. The Euston Road School was a group of "progressive" realists of the late 1930s, including the influential teacher William Coldstream. Surrealism, with artists including John Tunnard and the Birmingham Surrealists, was briefly popular in the 1930s, influencing Roland Penrose and Henry Moore. Stanley William Hayter was a British painter and printmaker associated in the 1930s with Surrealism and from 1940 onward with Abstract Expressionism.[79] In 1927 Hayter founded the legendary Atelier 17 studio in Paris. Since his death in 1988, it has been known as Atelier Contrepoint. Hayter became one of the most influential printmakers of the 20th century.[80] Fashionable portraitists included Meredith Frampton in a hard-faced Art Deco classicism, Augustus John, and Sir Alfred Munnings if horses were involved. Munnings was President of the Royal Academy 1944–1949 and led a jeering hostility to Modernism. The photographers of the period include Bill Brandt, Angus McBean and the diarist Cecil Beaton.

Henry Moore emerged after World War II as Britain's leading sculptor, promoted alongside Victor Pasmore, William Scott and Barbara Hepworth by the Festival of Britain. The "London School" of figurative painters including Francis Bacon, Lucian Freud, Frank Auerbach, Leon Kossoff, and Michael Andrews have received widespread international recognition,[81] while other painters such as John Minton and John Craxton are characterised as Neo-Romantics. Graham Sutherland, the Romantic landscapist John Piper (a prolific and popular lithographer), the sculptor Elisabeth Frink, and the industrial townscapes of L.S. Lowry also contributed to the strong figurative presence in post-war British art.

According to William Grimes of The New York Times "Lucien Freud and his contemporaries transformed figure painting in the 20th century. In paintings like Girl With a White Dog (1951-52), Freud put the pictorial language of traditional European painting in the service of an anti-romantic, confrontational style of portraiture that stripped bare the sitter’s social facade. Ordinary people — many of them his friends — stared wide-eyed from the canvas, vulnerable to the artist’s ruthless inspection."[82] In 1952 at the 26th Venice Biennale a group of young British sculptors including Kenneth Armitage, Reg Butler, Lynn Chadwick, William Turnbull and Eduardo Paolozzi, exhibited works that demonstrated anti-monumental, expressionism.[83] Scottish painter Alan Davie created a large body of abstract paintings during the 1950s that synthesize and reflect his interest in mythology and zen.[84] Abstract art became prominent during the 1950s with Ben Nicholson, Terry Frost, Peter Lanyon and Patrick Heron, who were part of the St Ives school in Cornwall.[85] In 1958, along with Kenneth Armitage and William Hayter, William Scott was chosen by the British Council for the British Pavilion at the XXIX Venice Biennale.

In the 1950s, the London-based Independent Group formed; from which pop art emerged in 1956 with the exhibition at the Institute of Contemporary Arts This Is Tomorrow, as a British reaction to abstract expressionism.[86] The International Group was the topic of a two-day, international conference at the Tate Britain in March 2007. The Independent Group is regarded as the precursor to the Pop Art movement in Britain and the United States.[86][87] The This is Tomorrow show featured Scottish artist Eduardo Paolozzi, Richard Hamilton, and artist John McHale amongst others, and the group included the influential art critic Lawrence Alloway as well.[88]

In the 1960s, Sir Anthony Caro became a leading figure of British sculpture[89] along with a younger generation of abstract artists including Isaac Witkin,[90] Phillip King and William G. Tucker.[91] John Hoyland,[92] Howard Hodgkin, John Walker, Ian Stephenson,[93][94] Robyn Denny, John Plumb[95] and William Tillyer[96] were British painters who emerged at that time and who reflected the new international style of Color Field painting.[97] During the 1960s another group of British artists offered a radical alternative to more conventional artmaking and they included Bruce McLean, Barry Flanagan, Richard Long and Gilbert and George. British pop art painters David Hockney, Patrick Caulfield, Derek Boshier, Peter Phillips, Peter Blake (best known for the cover-art for Sgt. Pepper's Lonely Hearts Club Band), Gerald Laing, the sculptor Allen Jones were part of the sixties art scene as was the British-based American painter R. B. Kitaj. Photorealism in the hands of Malcolm Morley (who was awarded the first Turner Prize in 1984) emerged in the 1960s as well as the op-art of Bridget Riley.[98] Michael Craig-Martin was an influential teacher of some of the Young British Artists and is known for the conceptual work, An Oak Tree (1973).[99]

-

John Duncan Fergusson, People and Sails at Royan, 1910

-

Roger Fry, River with Poplars, c. 1912

-

Spencer Gore of the Camden Town Group, Gauguins and Connoisseurs at the Stafford Gallery, 1911

-

James Bolivar Manson, Lucien Pissarro Reading c. 1913

-

David Bomberg, The Mud Bath, 1914

-

Paul Nash, The Ypres Salient at Night, 1917–18, he painted some of the most powerful images of World War I by an English artist.[100]

-

Dora Carrington, Portrait of E. M. Forster, 1924–1925

-

Henry Moore, Two Piece Reclining Figure No. 5, Bronze, 1963–1964

-

Sir Anthony Caro, Black Cover Flat (1974)

Contemporary art

[edit]

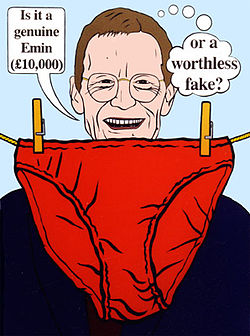

Post-modern, contemporary British art, particularly that of the Young British Artists, has been said to be "characterised by a fundamental concern with material culture ... perceived as a post-imperial cultural anxiety".[101] The annual Turner Prize, founded in 1984 and organised by the Tate, has developed as a highly publicised showcase for contemporary British art. Among the beneficiaries have been several members of the Young British Artists (YBA) movement, which includes Damien Hirst, Rachel Whiteread, and Tracey Emin, who rose to prominence after the Freeze exhibition of 1988, with the backing of Charles Saatchi and achieved international recognition with their version of conceptual art. This often featured installations, notably Hirst's vitrine containing a preserved shark. The Tate gallery and eventually the Royal Academy also gave them exposure. The influence of Saatchi's generous and wide-ranging patronage was to become a matter of some controversy, as was that of Jay Jopling, the most influential London gallerist.[citation needed]

The Sensation exhibition of works from the Saatchi Collection was controversial in both the UK and the US, though in different ways. At the Royal Academy press-generated controversy centred on Myra, a very large image of the murderer Myra Hindley by Marcus Harvey, but when the show travelled to New York City, opening at the Brooklyn Museum in late 1999, it was met with intense protest about The Holy Virgin Mary by Chris Ofili, which had not provoked this reaction in London. While the press reported that the piece was smeared with elephant dung, although Ofili's work in fact showed a carefully rendered black Madonna decorated with a resin-covered lump of elephant dung. The figure is also surrounded by small collage images of female genitalia from pornographic magazines; these seemed from a distance to be the traditional cherubim. Among other criticism, New York Mayor Rudolph Giuliani, who had seen the work in the catalogue but not in the show, called it "sick stuff" and threatened to withdraw the annual $7 million City Hall grant from the Brooklyn Museum hosting the show, because "You don't have a right to government subsidy for desecrating somebody else's religion."[102]

In 1999, the Stuckists figurative painting group which includes Billy Childish and Charles Thomson was founded as a reaction to the YBAs.[103] In 2004, the Walker Art Gallery staged The Stuckists Punk Victorian, the first national museum exhibition of the Stuckist art movement.[104] The Federation of British Artists hosts shows of traditional figurative painting.[105] Jack Vettriano and Beryl Cook have widespread popularity, but not establishment recognition.[106][107][108] Banksy made a reputation with street graffiti and is now a highly valued mainstream artist.[109]

Antony Gormley produces sculptures, mostly in metal and based on the human figure, which include the 20 metres (66 ft) high Angel of the North near Gateshead, one of the first of a number of very large public sculptures produced in the 2000s, Another Place, and Event Horizon. The Indian-born sculptor Anish Kapoor has public works around the world, including Cloud Gate in Chicago and Sky Mirror in various locations; like much of his work these use curved mirror-like steel surfaces. The environmental sculptures of British land artist Andy Goldsworthy have been created in many locations around the world. Using natural found materials they are often very ephemeral, and are recorded in photographs of which several collections in book form have been published.[110] Grayson Perry works in various media, including ceramics. Whilst leading printmakers include Norman Ackroyd, Elizabeth Blackadder, Barbara Rae and Richard Spare.

See also

[edit]- Art of Birmingham

- Bristol School

- List of artists from Northern Ireland

- List of Scottish artists

- List of Welsh artists

- Art UK

- Courtauld Institute of Art

- Dulwich Picture Gallery

- National Portrait Gallery

- Tate Britain

- Walker Art Gallery

- Whitechapel Art Gallery

- The Priseman Seabrook Collection

- British Marine Art (Romantic Era)

- List of equestrian statues in the United Kingdom

- List of Turner Prize winners and nominees

- London Art Fair

References

[edit]- ^ Strong (1999), 9–120, or see the references at the linked articles

- ^ Waterhouse, Chapters 1-6

- ^ Waterhouse, 152

- ^ Waterhouse, 138–139; 151; 163

- ^ Waterhouse, 135–138; 147–150

- ^ Waterhouse, 131–133. The "objections" included that it was a dark night, the boat was small, the king not smartly dressed, and many of the nobles who accompanied him were by then out of favour.

- ^ Waterhouse, 132–133; Pevsner, 29–30

- ^ Strong (1999), 358-361

- ^ Waterhouse, 165; 168–179

- ^ Waterhouse, 164–165

- ^ Waterhouse, 200-210

- ^ Waterhouse, 155–156

- ^ Waterhouse, 153–154, 157–160

- ^ Waterhouse, 163–164

- ^ Snowdin, 278-287, and see Index.

- ^ Snodin, 100–106

- ^ Snodin, 214-215

- ^ Strong (1999), Chapter 24

- ^ Pevsner, 172

- ^ Snodin, 15–17; 29–31 and throughout.

- ^ Reitlinger, 58 (quote), 59-75

- ^ Waterhouse, 217-230

- ^ Waterhouse, 164–165, 225–227, and see Index.

- ^ Waterhouse, 227-230

- ^ Waterhouse, Chapter 18; Piper, 54-56; Mellon, 82

- ^ Waterhouse, 306-311

- ^ Piper, 84; Reitlinger, 434-437 with the remarkable numbers

- ^ Waterhouse, 311-316

- ^ Reitlinger, 74-75; Waterhouse, 232-241

- ^ Pevsner, 159

- ^ Strong (1999), 478-479; Waterhouse, Chapter 20

- ^ Egerton, 332-342; Waterhouse, 285-289

- ^ Waterhouse, 315-322

- ^ Waterhouse, 327-329

- ^ Griffiths, 49, Chapter 6

- ^ snowdin, 236–242

- ^ Snodin, 154–157

- ^ Stephen Adams, The Telegraph, September 22, 2009, JMW Turner's feud with John Constable unveiled at Tate Britain Retrieved 9 December 2010

- ^ Jack Malvern, The Sunday Times, September 22, 2009, Tate Britain exhibition revives Turner and Constable’s old rivalry[dead link] Retrieved 9 December 2010

- ^ "J.M.W. Turner, the Original Artist-Curator – Look Closer". Tate.

- ^ Constable's Great Landscapes: The Six-Foot Paintings, National Gallery of Art, Washington, DC Retrieved 9 December 2010

- ^ Pevsner, 161–164; Mellon, 134; Tate 2006 Constable exhibition Tate Britain feature.

- ^ Piper, 116

- ^ Piper, 127–129

- ^ Dictionary of women artists Retrieved 8 December 2010

- ^ Shirley Dent and Jason Whittaker. Radical Blake: Influence and Afterlife from 1827. Houndmills: Palgrave, 2002.

- ^ Neil Spencer, The Guardian, October 2000, Into the Mystic, an homage to the written work of William Blake. Retrieved 8 December 2010

- ^ Piper, 96-98; Waterhouse, 330

- ^ Piper, 135

- ^ Piper, 84

- ^ Reitlinger, 97

- ^ Piper, 139–146; Wilson, 79–81

- ^ Piper, 149; Strong (1999), 540–541; Reitlinger, 97–99, 148–151 and elsewhere; he has detail throughout on reproduction rights.

- ^ Wilson, 85; Bills, Mark, Frith and the Influence of Hogarth, in William Powell Frith: painting the Victorian age, by Mark Bills & Vivien Knight, Yale University Press, 2006, ISBN 0-300-12190-3, ISBN 978-0-300-12190-2

- ^ Reitlinger, 157; Wilson, 85; Frith's Salon d'Or, Homburg (1871), now Providence, Rhode Island, is Frith's last great panorama, of the gambling at Homburg [1].

- ^ Piper, 131

- ^ Strong (1978), throughout. See Appendix I for a revealing full listing of pictures shown at the RA 1769–1904, analysed by subject

- ^ Strong (1978), 47-73

- ^ Conrad, Peter. The Victorian Treasure House

- ^ Fletcher, throughout

- ^ Piper, 148–151

- ^ a b Whistler versus Ruskin, Princeton edu. Archived 16 June 2010 at the Wayback Machine Retrieved 13 June 2010

- ^ a b [2] Archived 12 January 2012 at the Wayback Machine, from the Tate, retrieved 12 April 2009

- ^ Wilson, 89-91; Rosenthal, 144, 160–162; Reitlinger, 156–157

- ^ Frayling, 12-64

- ^ Hamilton, 57-62; Wilson, 97-99

- ^ Hamilton, 146–148

- ^ Peters, Lisa N., James McNeil Whistler, pp. 51-52, ISBN 1-880908-70-0.

- ^ "See The Correspondence of James McNeill Whistler". Archived from the original on 20 September 2008.

- ^ Peter Stansky's review of Linda Merill's A Pot of Paint: Aesthetics on Trial in Whistler v. Ruskin in the Journal of Interdisciplinary History, Vol. 24, No. 3 (Winter, 1994), pp. 536-537 [3]

- ^ a b McKenzie, John, Art and Empire, britishempire.co.uk, retrieved 24 October 2008

- ^ Barringer et al 2007, p. 3.

- ^ Gothic Revival Feature from the Victoria and Albert Museum

- ^ Voysey wallpaper, V&A Museum

- ^ a b Jenkins et al 2005, p. 5.

- ^ Wilson, 127–129; Mellon, 182–186

- ^ Camden Town Group, Tate Retrieved 7 December 2010

- ^ Scottish Colourists, Tate Retrieved 14 December 2010

- ^ "Stanley William Hayter (1901 − 1989)". Art Collection. British Council. Archived from the original on 15 July 2010. Retrieved 5 October 2010.

- ^ Brenson, Michael (6 May 1988). "Stanley William Hayter, 86, Dies; Painter Taught Miró and Pollock". The New York Times. Retrieved 18 October 2008.

- ^ Walker, 219-225

- ^ "Lucian Freud, Figurative Painter Who Redefined Portraiture, Is Dead at 88". The New York Times. 21 July 2011.

- ^ "The Bronze Age Archived 5 January 2012 at the UK Government Web Archive". Tate Magazine, Issue 6, 2008. Retrieved on 9 December 2010.

- ^ Alan Davie, Tate Retrieved 15 December 2010

- ^ Walker, 211-217

- ^ a b Livingstone, M., (1990), Pop Art: A Continuing History, New York: Harry N. Abrams, Inc.

- ^ Arnason, H., History of Modern Art: Painting, Sculpture, Architecture, New York: Harry N. Abrams, Inc. 1968.

- ^ This is Tomorrow 1956 catalog Archived 10 July 2010 at the Wayback Machine Retrieved 9 December 2010

- ^ Anthony Caro Exhibition 2005, Tate Britain Retrieved 9 December 2010

- ^ May 2006, Sunday Times obituary Retrieved 9 December 2010

- ^ ISC Lifetime Achievements Award in Sculpture Retrieved 9 December 2010

- ^ tate.org.uk Archived 11 January 2012 at the Wayback Machine Retrieved 9 December 2010

- ^ Ian Stephenson Biography Archived 16 December 2010 at the Wayback Machine New Art Centre Retrieved 9 December 2010

- ^ Ian Stephenson 1934 - 2000 Tate website Retrieved 9 December 2010

- ^ Tate Collection Retrieved 9 December 2010

- ^ William Tillyer Retrieved 15 January 2018]

- ^ "Colorscope: Abstract Painting 1960–1979". Santa Barbara Museum of Art. 2010. Archived from the original on 3 July 2010. Retrieved 9 December 2010.

- ^ Tate Biography Retrieved December 2010

- ^ Irish Museum of Modern Art Website Archived 21 May 2009 at the Wayback Machine Retrieved 9 December 2010

- ^ Gough, Paul (2010). A Terrible Beauty: British Artists in the First World War. pp. 127–164.

- ^ Barringer et al 2007, p. 17.

- ^ "Sensation sparks New York storm", BBC, 23 September 1999. Retrieved 17 October 2008.

- ^ Cassidy, Sarah. "Stuckists, scourge of BritArt, put on their own exhibition", The Independent, 23 August 2006. Retrieved 6 July 2008.

- ^ Moss, Richard. "Stuckist's Punk Victorian gatecrashes Walker's Biennial, Culture24, 17 September 2004. Retrieved 3 December 2009.

- ^ "Major new £25,000 Threadneedle art prize announced to rival Turner Prize", 24 Hour Museum, 5 September 2007. Retrieved 7 July 2008.

- ^ Smith, David. "He's our favourite artist. So why do the galleries hate him so much?", The Observer, 11 January 2004. Retrieved 7 July 2008.

- ^ Campbell, Duncan. "Beryl Cook, artist who painted with a smile, dies", The Guardian, 29 May 2008. Retrieved 7 July 2008.

- ^ "Painter Beryl Cook dies aged 81" BBC, 28 May 2008. Retrieved 7 July 2008.

- ^ Reynolds, Nigel. "Banksy's graffiti art sells for half a million", The Daily Telegraph, 25 October 2007. Retrieved 7 July 2008.

- ^ Adams, Tim (11 March 2007). "The Interview: Andy Goldsworthy". The Observer – via www.theguardian.com.

Sources

[edit]- Barringer, T. J.; Quilley, Geoff; Fordham, Douglas (2007), Art and the British Empire, Manchester University Press, ISBN 978-0-7190-7392-2

- Egerton, Judy, National Gallery Catalogues (new series): The British School, 1998, ISBN 1-85709-170-1

- Fletcher, Pamela, Narrating Modernity: The British Problem Picture, 1895–1914, Ashgate, 2003

- Frayling, Christopher, The Royal College of Art, One Hundred and Fifty Years of Art and Design, 1987, Barrie & Jenkins, London, ISBN 0-7126-1820-1

- Griffiths, Antony (ed), Landmarks in Print Collecting: Connoisseurs and Donors at the British Museum since 1753, 1996, British Museum Press, ISBN 0-7141-2609-8

- Hamilton, George Heard, Painting and Sculpture in Europe, 1880-1940 (Pelican History of Art), Yale University Press, revised 3rd edn. 1983 ISBN 0-14-056129-3

- Hughes, Henry Meyric and Gijs van Tuyl (eds.), Blast to Freeze: British Art in the 20th Century, 2003, Hatje Cantz, ISBN 3-7757-1248-8

- Jenkins, Adrian; Marshall, Francis; Winch, Dinah; Morris, David (2005). Creative Tension: British Art 1900-1950. Paul Holberton. ISBN 978-1-903470-28-2.

- "Mellon": Warner, Malcolm and Alexander, Julia Marciari, This Other Eden, British Paintings from the Paul Mellon Collection at Yale, Yale Center for British Art/Art Exhibitions Australia, 1998

- Parkinson, Ronald, Victoria and Albert Museum, Catalogue of British Oil Paintings, 1820–1860, 1990, HMSO, ISBN 0-11-290463-7

- Pevsner, Nikolaus. The Englishness of English Art, Penguin, 1964 edn.

- Piper, David, Painting in England, 1500–1880, Penguin, 1965 edn.

- Reitlinger, Gerald; The Economics of Taste, Vol I: The Rise and Fall of Picture Prices 1760-1960, Barrie and Rockliffe, London, 1961

- Rosenthal, Michael, British Landscape Painting, 1982, Phaidon Press, London

- Snodin, Michael (ed). Rococo; Art and Design in Hogarth's England, 1984, Trefoil Books/Victoria and Albert Museum, ISBN 0-86294-046-X

- "Strong (1978)": Strong, Roy: And when did you last see your father? The Victorian Painter and British History, 1978, Thames and Hudson, ISBN 0-500-27132-1 (Recreating the past .... in US; Painting the Past ... in 2004 edition)

- "Strong (1999)": Strong, Roy: The Spirit of Britain, 1999, Hutchison, London, ISBN 1-85681-534-X

- Waterhouse, Ellis, Painting in Britain, 1530–1790, 4th Edn, 1978, Penguin Books (now Yale History of Art series), ISBN 0-300-05319-3

- Wilson, Simon; Tate Gallery, An Illustrated Companion, 1990, Tate Gallery, ISBN 9781854370587

- Andrew Wilton & Anne Lyles, The Great Age of British Watercolours, 1750–1880, 1993, Prestel, ISBN 3-7913-1254-5

External links

[edit]Art of the United Kingdom

View on GrokipediaArt of the United Kingdom encompasses the visual arts—primarily painting, sculpture, and printmaking—produced within England, Scotland, Wales, and [Northern Ireland](/page/Northern Ireland), with historical roots in prehistoric and medieval periods but distinctive development from the 16th century onward, marked by a predominance of portraiture due to aristocratic patronage and the post-Reformation absence of grand religious commissions.[1][2] This tradition, initially reliant on foreign artists like Hans Holbein the Younger, evolved into a native school in the 18th century through figures such as William Hogarth, who pioneered satirical genre scenes critiquing social morals, and portraitists Joshua Reynolds and Thomas Gainsborough, who elevated empirical observation and imaginative composition.[3][2] The 19th century saw a landscape revolution led by J.M.W. Turner and John Constable, whose works captured atmospheric effects and natural realism, reflecting Britain's industrial transformation and Romantic emphasis on empirical study of light and form, while the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood reacted against academic conventions with meticulous detail and medieval-inspired themes.[2] The founding of the Royal Academy of Arts in 1768 institutionalized training and exhibitions, fostering national identity amid continental influences, though British art retained a characteristically insular, observation-driven quality distinct from the history painting traditions of Italy or France.[3] In the 20th century, movements like Vorticism and the Young British Artists introduced abstraction and conceptual provocation, with sculptors such as Henry Moore emphasizing organic forms derived from direct carving techniques.[2] Defining achievements include the empirical rigor in rendering nature and human character, contributing disproportionately to global portraiture and landscape genres despite limited early patronage for monumental works.[4][5]

Ancient and Medieval Foundations

Prehistoric and Celtic Art

Prehistoric art in Britain dates back to the Upper Paleolithic period, with evidence of engraved designs on cave walls at sites such as Creswell Crags in Derbyshire, where animal depictions including ibex and horses have been dated to approximately 13,000–11,000 years ago using uranium-thorium dating methods.[6] These markings represent the earliest known artistic expressions in the British Isles, created by mobile hunter-gatherer groups during the late Ice Age, though such cave art is rarer in Britain compared to continental Europe due to fewer suitable limestone caves.[7] In the Mesolithic period (c. 9600–4000 BC), artistic production shifted toward portable objects amid post-glacial recolonization by forests and wetlands. A notable example is the engraved shale pendant from Star Carr in North Yorkshire, dated to around 11,000 years ago via radiocarbon analysis of associated antler fragments, featuring zigzag and dotted motifs possibly symbolizing landscape features or ritual significance.[8] Bone and antler tools occasionally bear incised patterns, but overall, Mesolithic art remains sparse, reflecting small, nomadic populations focused on survival rather than monumental expression.[9] The Neolithic era (c. 4000–2500 BC) saw a proliferation of rock art and megalithic carvings, coinciding with the adoption of farming and communal monument-building. Cup-and-ring marks—concentric circles, spirals, and grooves—adorn bedrock outcrops across northern England, Scotland, and Wales, with concentrations in areas like Northumberland and Kilmartin Glen, Argyll, where over 1,000 motifs have been documented, often aligned with astronomical events or territorial markers.[10] At the Ness of Brodgar in Orkney, incised stone slabs from temple-like structures reveal geometric patterns and possible animal forms, representing the largest Neolithic art assemblage in Britain and suggesting elite ritual contexts.[11] Stonehenge's sarsen stones bear axe-head petroglyphs from c. 2500 BC, linking art to emerging metallurgy and trade networks.[12] Bronze Age art (c. 2500–800 BC) emphasized metalworking, driven by tin-copper alloy innovations and Wessex culture's elite hoards. Gold lunulae and amber necklaces from Ireland-influenced burials feature incised zigzags and solar motifs, while bronze artifacts like the cauldrons from Barnsley Park and riveted horns from Irton exhibit embossed decorations symbolizing feasting and status.[13] Beaker pottery, introduced c. 2400 BC by steppe-derived migrants who largely replaced local populations per ancient DNA studies, displays zoned incised patterns reflecting continental influences.[14] Rock art persisted, with animal carvings in Scotland dated 4000–5000 years old via contextual stratigraphy, indicating continuity in symbolic practices amid climatic shifts.[15] Celtic art in Britain, associated with the Iron Age (c. 800 BC–AD 43), manifested primarily in La Tène-style metalwork, evolving from Hallstatt continental prototypes around 500 BC through trade and migration. Curvilinear motifs—swirling tendrils, palmettes, and stylized animals—adorned bronze shields, sword scabbards, and torcs, as seen in the Snettisham Hoard of over 150 gold torcs from Norfolk, radiocarbon-dated to 100–50 BC, showcasing filigree and granulation techniques for elite display.[16] Weapons like the Waterloo Helmet (c. 150–50 BC), with repoussé boar crests, and the Battersea Shield (c. 350–50 BC), featuring enamel inlays and swirling bosses, highlight martial and watery deposition rituals, with enameling techniques likely diffused from the Mediterranean.[17] This insular Celtic style, distinct from core European La Tène by emphasizing symmetry and abstraction, persisted in hillfort contexts like Maiden Castle, reflecting tribal hierarchies without centralized states, as evidenced by limited figural sculpture focused on heads symbolizing ancestry or divinity.[18] Such artifacts, often from weapon hoards, underscore a worldview integrating art with warfare and cosmology, predating Roman conquest.[19]Roman and Early Christian Influences

Roman Britain, from the Claudian invasion in AD 43 to the province's abandonment around AD 410, witnessed the imposition of Mediterranean artistic conventions on indigenous Celtic traditions, resulting in hybrid forms evident in surviving mosaics, sculptures, and frescoes primarily from elite villas and urban centers. Mosaics, crafted from tesserae of stone, glass, and ceramic, adorned hypocaust-heated floors and symbolized wealth and cultural aspiration; approximately 800 examples have been documented across the province, peaking in the 3rd and 4th centuries.[20] These often portrayed classical deities, hunting scenes, or geometric motifs adapted to local tastes, as seen in the Dolphin mosaic at Fishbourne Roman Palace (West Sussex, constructed c. AD 75 with mosaics added by the 2nd century) and the expansive Orpheus pavement at Bignor Roman Villa (Sussex, 3rd-4th century), where mythological narratives underscored villa owners' Romanized identity.[21] [22] Sculpture, executed in local limestones and sandstones or imported marbles, emphasized portraiture, divine iconography, and commemorative reliefs, frequently merging Roman verism with Celtic abstraction in facial features and drapery. Key survivals include the bronze equestrian statue of the Emperor Hadrian from Catterick (North Yorkshire, c. AD 120-130), capturing imperial authority, and the pedimental Gorgon head from Bath's temple complex (Somerset, c. AD 50-100), a protective apotropaic figure blending Graeco-Roman and provincial styles.[21] Funerary monuments, such as the stele of the cavalryman Genialis from Cirencester (c. AD 100-150), further illustrate military patronage of art, with inscriptions and carvings reflecting continental influences.[23] Early Christian motifs emerged in the 4th century amid the religion's dissemination through urban and villa elites, repurposing Roman media for symbolic expression without wholesale rejection of pagan forms—a pragmatic adaptation driven by Christianity's minority status until Edict of Milan tolerances post-AD 313. The Hinton St Mary mosaic (Dorset, mid-4th century), unearthed in 1963, contains Britain's earliest identifiable Christ portrait—a youthful, beardless head within a roundel, encircled by chi-rho christograms and flanked by bichon friezes—indicating elite Christian patronage in a rural villa setting.[24] Complementarily, Lullingstone Roman Villa (Kent, late 4th century) preserves wall paintings in a dedicated upper-room oratory, featuring multiple chi-rho overlays on red grounds and orant (praying) female figures in tunics, marking the sole surviving Romano-British Christian fresco ensemble and evidencing domestic worship spaces.[25] These artifacts, transitional in nature, prefigure post-Roman insular developments while highlighting art's role in signaling emerging religious allegiances amid provincial decline.[26]Anglo-Saxon, Norman, and Gothic Developments

Anglo-Saxon art, spanning from the 5th to the 11th century, primarily survives in metalwork, illuminated manuscripts, and stone sculpture, reflecting a fusion of Germanic pagan traditions and later Christian influences following the conversion around the 7th century. Early examples feature intricate interlace patterns, zoomorphic motifs, and geometric designs in jewelry and weaponry, as seen in the Sutton Hoo ship burial (c. 625 CE), which yielded gold shoulder-clasps and purse lids adorned with cloisonné garnets and stylized animal interlace symbolizing status and possibly protective rituals. After Christianization, art shifted toward religious themes, with high crosses like the 8th-century Bewcastle Cross in Cumbria displaying carved runes, biblical scenes, and vine scroll motifs blending Insular and continental styles, evidencing monastic workshops' role in cultural transmission.[27] Illuminated manuscripts, such as the Lindisfarne Gospels (c. 715–720 CE) produced at the Northumbrian monastery, exemplify carpet pages of abstract knotwork and evangelist portraits, where dense patterning served didactic and meditative purposes in spreading literacy and theology.[28] The Norman Conquest of 1066 introduced Romanesque styles from Normandy, emphasizing massive stone architecture for fortification and ecclesiastical dominance, as in the White Tower of the Tower of London (completed c. 1100), with its thick walls and rounded arches prioritizing defensive solidity over ornament. Sculpture and textiles reflected this shift, with the Bayeux Tapestry (c. 1070s)—a 70-meter embroidered linen depicting the Conquest's events, including Halley's Comet sighting in 1066—employing narrative friezes, figures in Norman attire, and Latin tituli to propagandize William's claim, likely crafted by English needleworkers under Norman patronage.[29] Church portals, such as those at Durham Cathedral (begun 1093), featured robust tympana with Christ in Majesty and apocalyptic beasts, adapting Carolingian models to assert feudal order and deter rebellion through visual intimidation.[30] Gothic developments emerged in England around the mid-12th century, evolving from Romanesque through innovations like pointed arches and rib vaults that enabled taller, lighter structures and larger windows for illuminating interiors with stained glass. The choir of Canterbury Cathedral, rebuilt after a 1174 fire by French architect William of Sens, introduced Early English Gothic lancet windows and Purbeck marble shafts, distributing weight to allow ethereal height symbolizing divine aspiration.[31] By the 13th century, Decorated Gothic flourished with intricate tracery and naturalistic foliage, as in Lincoln Cathedral's Angel Choir (c. 1256–1280), featuring 28 carved angels and screen walls that balanced structural engineering with sculptural exuberance funded by wool trade wealth.[32] Perpendicular Gothic, distinctly English from the late 14th century, emphasized verticality and fan vaults, exemplified by the cloisters of Gloucester Cathedral (c. 1351–1412), where rectilinear panels and uniform ribs reflected Perpendicular phase's geometric rationalism and crown patronage under Edward III, prioritizing uniformity over continental flamboyance.[33] These advancements, driven by monastic orders and royal endowments, integrated art with architecture to foster communal piety amid feudal consolidation.[34]Early Modern Developments

Tudor Renaissance and Portraiture