Recent from talks

Contribute something

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Epigenetics

View on Wikipedia

Epigenetics is the study of changes in gene expression that occur without altering the DNA sequence.[1] The Greek prefix epi- (ἐπι- "over, outside of, around") in epigenetics implies features that are "on top of" or "in addition to" the traditional DNA-sequence-based mechanism of inheritance.[2] Epigenetics usually involves changes that persist through cell division, and affect the regulation of gene expression.[3] Such effects on cellular and physiological traits may result from environmental factors, or be part of normal development.

The term also refers to the mechanism behind these changes: functionally relevant alterations to the genome that do not involve mutations in the nucleotide sequence. Examples of mechanisms that produce such changes are DNA methylation and histone modification, each of which alters how genes are expressed without altering the underlying DNA sequence.[4] Further, non-coding RNA sequences have been shown to play a key role in the regulation of gene expression.[5] Gene expression can be controlled through the action of repressor proteins that attach to silencer regions of the DNA. These epigenetic changes may last through cell divisions for the duration of the cell's life, and may also last for multiple generations, even though they do not involve changes in the underlying DNA sequence of the organism;[6] instead, non-genetic factors cause the organism's genes to behave (or "express themselves") differently.[7]

One example of an epigenetic change in eukaryotic biology is the process of cellular differentiation. During morphogenesis, totipotent stem cells become the various pluripotent cell lines of the embryo, which in turn become fully differentiated cells. In other words, as a single fertilized egg cell – the zygote – continues to divide, the resulting daughter cells develop into the different cell types in an organism, including neurons, muscle cells, epithelium, endothelium of blood vessels, etc., by activating some genes while inhibiting the expression of others.[8]

Definitions

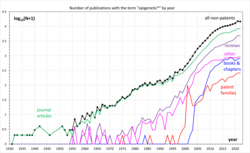

[edit]The term epigenesis has a generic meaning of "extra growth" that has been used in English since the 17th century.[9] In scientific publications, the term epigenetics started to appear in the 1930s (see Fig. on the right). However, its contemporary meaning emerged only in the 1990s.[10]

A definition of the concept of epigenetic trait as a "stably heritable phenotype resulting from changes in a chromosome without alterations in the DNA sequence" was formulated at a Cold Spring Harbor meeting in 2008,[11] although alternate definitions that include non-heritable traits are still being used widely.[12]

Waddington's canalisation, 1940s

[edit]The hypothesis of epigenetic changes affecting the expression of chromosomes was put forth by the Russian biologist Nikolai Koltsov.[13] From the generic meaning, and the associated adjective epigenetic, British embryologist C. H. Waddington coined the term epigenetics in 1942 as pertaining to epigenesis, in parallel to Valentin Haecker's 'phenogenetics' (Phänogenetik).[14] Epigenesis in the context of the biology of that period referred to the differentiation of cells from their initial totipotent state during embryonic development.[15]

When Waddington coined the term, the physical nature of genes and their role in heredity was not known. He used it instead as a conceptual model of how genetic components might interact with their surroundings to produce a phenotype; he used the phrase "epigenetic landscape" as a metaphor for biological development. Waddington held that cell fates were established during development in a process he called canalisation much as a marble rolls down to the point of lowest local elevation.[16] Waddington suggested visualising increasing irreversibility of cell type differentiation as ridges rising between the valleys where the marbles (analogous to cells) are travelling.[17]

In recent times, Waddington's notion of the epigenetic landscape has been rigorously formalized in the context of the systems dynamics state approach to the study of cell-fate.[18][19] Cell-fate determination is predicted to exhibit certain dynamics, such as attractor-convergence (the attractor can be an equilibrium point, limit cycle or strange attractor) or oscillatory.[19]

Contemporary

[edit]In 1990, Robin Holliday defined epigenetics as "the study of the mechanisms of temporal and spatial control of gene activity during the development of complex organisms."[20]

More recent usage of the word in biology follows stricter definitions. As defined by Arthur Riggs and colleagues, it is "the study of mitotically and/or meiotically heritable changes in gene function that cannot be explained by changes in DNA sequence."[21]

The term has also been used, however, to describe processes which have not been demonstrated to be heritable, such as some forms of histone modification. Consequently, there are attempts to redefine "epigenetics" in broader terms that would avoid the constraints of requiring heritability. For example, Adrian Bird defined epigenetics as "the structural adaptation of chromosomal regions so as to register, signal or perpetuate altered activity states."[6] This definition would be inclusive of transient modifications associated with DNA repair or cell-cycle phases as well as stable changes maintained across multiple cell generations, but exclude others such as templating of membrane architecture and prions unless they impinge on chromosome function. Such redefinitions however are not universally accepted and are still subject to debate.[22] The NIH "Roadmap Epigenomics Project", which ran from 2008 to 2017, uses the following definition: "For purposes of this program, epigenetics refers to both heritable changes in gene activity and expression (in the progeny of cells or of individuals) and also stable, long-term alterations in the transcriptional potential of a cell that are not necessarily heritable."[23] In 2008, a consensus definition of the epigenetic trait, a "stably heritable phenotype resulting from changes in a chromosome without alterations in the DNA sequence," was made at a Cold Spring Harbor meeting.[11]

The similarity of the word to "genetics" has generated many parallel usages. The "epigenome" is a parallel to the word "genome", referring to the overall epigenetic state of a cell, and epigenomics refers to global analyses of epigenetic changes across the entire genome.[12] The phrase "genetic code" has also been adapted – the "epigenetic code" has been used to describe the set of epigenetic features that create different phenotypes in different cells from the same underlying DNA sequence. Taken to its extreme, the "epigenetic code" could represent the total state of the cell, with the position of each molecule accounted for in an epigenomic map, a diagrammatic representation of the gene expression, DNA methylation and histone modification status of a particular genomic region. More typically, the term is used in reference to systematic efforts to measure specific, relevant forms of epigenetic information such as the histone code or DNA methylation patterns.[citation needed]

Mechanisms

[edit]Covalent modification of either DNA (e.g. cytosine methylation and hydroxymethylation) or of histone proteins (e.g. lysine acetylation, lysine and arginine methylation, serine and threonine phosphorylation, and lysine ubiquitination and sumoylation) play central roles in many types of epigenetic inheritance. Therefore, the word "epigenetics" is sometimes used as a synonym for these processes. However, this can be misleading. Chromatin remodeling is not always inherited, and not all epigenetic inheritance involves chromatin remodeling.[24] In 2019, a further lysine modification appeared in the scientific literature linking epigenetics modification to cell metabolism, i.e. lactylation.[25]

Because the phenotype of a cell or individual is affected by which of its genes are transcribed, heritable transcription states can give rise to epigenetic effects. There are several layers of regulation of gene expression. One way that genes are regulated is through the remodeling of chromatin. Chromatin is the complex of DNA and the histone proteins with which it associates. If the way that DNA is wrapped around the histones changes, gene expression can change as well. Chromatin remodeling is accomplished through two main mechanisms:

- The first way is post translational modification of the amino acids that make up histone proteins. Histone proteins are made up of long chains of amino acids. If the amino acids that are in the chain are changed, the shape of the histone might be modified. DNA is not completely unwound during replication. It is possible, then, that the modified histones may be carried into each new copy of the DNA. Once there, these histones may act as templates, initiating the surrounding new histones to be shaped in the new manner. By altering the shape of the histones around them, these modified histones would ensure that a lineage-specific transcription program is maintained after cell division.

- The second way is the addition of methyl groups to the DNA, mostly at CpG sites, to convert cytosine to 5-methylcytosine. 5-Methylcytosine performs much like a regular cytosine, pairing with a guanine in double-stranded DNA. However, when methylated cytosines are present in CpG sites in the promoter and enhancer regions of genes, the genes are often repressed.[26][27] When methylated cytosines are present in CpG sites in the gene body (in the coding region excluding the transcription start site) expression of the gene is often enhanced. Transcription of a gene usually depends on a transcription factor binding to a (10 base or less) recognition sequence at the enhancer that interacts with the promoter region of that gene (Gene expression#Enhancers, transcription factors, mediator complex and DNA loops in mammalian transcription).[28] About 22% of transcription factors are inhibited from binding when the recognition sequence has a methylated cytosine. In addition, presence of methylated cytosines at a promoter region can attract methyl-CpG-binding domain (MBD) proteins. All MBDs interact with nucleosome remodeling and histone deacetylase complexes, which leads to gene silencing. In addition, another covalent modification involving methylated cytosine is its demethylation by TET enzymes. Hundreds of such demethylations occur, for instance, during learning and memory forming events in neurons.[29][30]

There is frequently a reciprocal relationship between DNA methylation and histone lysine methylation.[31] For instance, the methyl binding domain protein MBD1, attracted to and associating with methylated cytosine in a DNA CpG site, can also associate with H3K9 methyltransferase activity to methylate histone 3 at lysine 9. On the other hand, DNA maintenance methylation by DNMT1 appears to partly rely on recognition of histone methylation on the nucleosome present at the DNA site to carry out cytosine methylation on newly synthesized DNA.[31] There is further crosstalk between DNA methylation carried out by DNMT3A and DNMT3B and histone methylation so that there is a correlation between the genome-wide distribution of DNA methylation and histone methylation.[32]

Mechanisms of heritability of histone state are not well understood; however, much is known about the mechanism of heritability of DNA methylation state during cell division and differentiation. Heritability of methylation state depends on certain enzymes (such as DNMT1) that have a higher affinity for 5-methylcytosine than for cytosine. If this enzyme reaches a "hemimethylated" portion of DNA (where 5-methylcytosine is in only one of the two DNA strands) the enzyme will methylate the other half. However, it is now known that DNMT1 physically interacts with the protein UHRF1. UHRF1 has been recently recognized as essential for DNMT1-mediated maintenance of DNA methylation. UHRF1 is the protein that specifically recognizes hemi-methylated DNA, therefore bringing DNMT1 to its substrate to maintain DNA methylation.[32]

Although histone modifications occur throughout the entire sequence, the unstructured N-termini of histones (called histone tails) are particularly highly modified. These modifications include acetylation, methylation, ubiquitylation, phosphorylation, sumoylation, ribosylation and citrullination. Acetylation is the most highly studied of these modifications. For example, acetylation of the K14 and K9 lysines of the tail of histone H3 by histone acetyltransferase enzymes (HATs) is generally related to transcriptional competence[34] (see Figure).

One mode of thinking is that this tendency of acetylation to be associated with "active" transcription is biophysical in nature. Because it normally has a positively charged nitrogen at its end, lysine can bind the negatively charged phosphates of the DNA backbone. The acetylation event converts the positively charged amine group on the side chain into a neutral amide linkage. This removes the positive charge, thus loosening the DNA from the histone. When this occurs, complexes like SWI/SNF and other transcriptional factors can bind to the DNA and allow transcription to occur. This is the "cis" model of the epigenetic function. In other words, changes to the histone tails have a direct effect on the DNA itself.[35]

Another model of epigenetic function is the "trans" model. In this model, changes to the histone tails act indirectly on the DNA. For example, lysine acetylation may create a binding site for chromatin-modifying enzymes (or transcription machinery as well). This chromatin remodeler can then cause changes to the state of the chromatin. Indeed, a bromodomain – a protein domain that specifically binds acetyl-lysine – is found in many enzymes that help activate transcription, including the SWI/SNF complex. It may be that acetylation acts in this and the previous way to aid in transcriptional activation.

The idea that modifications act as docking modules for related factors is borne out by histone methylation as well. Methylation of lysine 9 of histone H3 has long been associated with constitutively transcriptionally silent chromatin (constitutive heterochromatin) (see bottom Figure). It has been determined that a chromodomain (a domain that specifically binds methyl-lysine) in the transcriptionally repressive protein HP1 recruits HP1 to K9 methylated regions. One example that seems to refute this biophysical model for methylation is that tri-methylation of histone H3 at lysine 4 is strongly associated with (and required for full) transcriptional activation (see top Figure). Tri-methylation, in this case, would introduce a fixed positive charge on the tail.

It has been shown that the histone lysine methyltransferase (KMT) is responsible for this methylation activity in the pattern of histones H3 & H4. This enzyme utilizes a catalytically active site called the SET domain (Suppressor of variegation, Enhancer of Zeste, Trithorax). The SET domain is a 130-amino acid sequence involved in modulating gene activities. This domain has been demonstrated to bind to the histone tail and causes the methylation of the histone.[36]

Differing histone modifications are likely to function in differing ways; acetylation at one position is likely to function differently from acetylation at another position. Also, multiple modifications may occur at the same time, and these modifications may work together to change the behavior of the nucleosome. The idea that multiple dynamic modifications regulate gene transcription in a systematic and reproducible way is called the histone code, although the idea that histone state can be read linearly as a digital information carrier has been largely debunked. One of the best-understood systems that orchestrate chromatin-based silencing is the SIR protein based silencing of the yeast hidden mating-type loci HML and HMR.

DNA methylation

[edit]DNA methylation often occurs in repeated sequences, and helps to suppress the expression and movement of 'transposable elements':[37] Because 5-methylcytosine can spontaneously deaminate to thymidine(replacing nitrogen by oxygen), CpG sites are frequently mutated and have become rare in the genome, except at CpG islands where they typically remain unmethylated. Epigenetic changes of this type thus have the potential to direct increased frequencies of permanent genetic mutation. DNA methylation patterns are known to be established and modified in response to environmental factors by a complex interplay of at least three independent DNA methyltransferases, DNMT1, DNMT3A, and DNMT3B, the loss of any of which is lethal in mice.[38] DNMT1 is the most abundant methyltransferase in somatic cells,[39] localizes to replication foci,[40] has a 10–40-fold preference for hemimethylated DNA and interacts with the proliferating cell nuclear antigen (PCNA).[41]

By preferentially modifying hemimethylated DNA, DNMT1 transfers patterns of methylation to a newly synthesized strand after DNA replication, and therefore is often referred to as the 'maintenance' methyltransferase.[42] DNMT1 is essential for proper embryonic development, imprinting and X-inactivation.[38][43] To emphasize the difference of this molecular mechanism of inheritance from the canonical Watson-Crick base-pairing mechanism of transmission of genetic information, the term 'Epigenetic templating' was introduced.[44] Furthermore, in addition to the maintenance and transmission of methylated DNA states, the same principle could work in the maintenance and transmission of histone modifications and even cytoplasmic (structural) heritable states.[45]

RNA methylation

[edit]RNA methylation of N6-methyladenosine (m6A) as the most abundant eukaryotic RNA modification has recently been recognized as an important gene regulatory mechanism.[46]

In 2011, it was demonstrated that the methylation of mRNA plays a critical role in human energy homeostasis. The obesity-associated FTO gene is shown to be able to demethylate N6-methyladenosine in RNA.[47][48]

Histone modifications

[edit]Histones H3 and H4 can also be manipulated through demethylation using histone lysine demethylase (KDM). This recently identified enzyme has a catalytically active site called the Jumonji domain (JmjC). The demethylation occurs when JmjC utilizes multiple cofactors to hydroxylate the methyl group, thereby removing it. JmjC is capable of demethylating mono-, di-, and tri-methylated substrates.[49]

Chromosomal regions can adopt stable and heritable alternative states resulting in bistable gene expression without changes to the DNA sequence. Epigenetic control is often associated with alternative covalent modifications of histones.[50] The stability and heritability of states of larger chromosomal regions are suggested to involve positive feedback where modified nucleosomes recruit enzymes that similarly modify nearby nucleosomes.[51] A simplified stochastic model for this type of epigenetics is found here.[52][53]

It has been suggested that chromatin-based transcriptional regulation could be mediated by the effect of small RNAs. Small interfering RNAs can modulate transcriptional gene expression via epigenetic modulation of targeted promoters.[54]

RNA transcripts

[edit]Sometimes, a gene, once activated, transcribes a product that directly or indirectly sustains its own activity. For example, Hnf4 and MyoD enhance the transcription of many liver-specific and muscle-specific genes, respectively, including their own, through the transcription factor activity of the proteins they encode. RNA signalling includes differential recruitment of a hierarchy of generic chromatin modifying complexes and DNA methyltransferases to specific loci by RNAs during differentiation and development.[55] Other epigenetic changes are mediated by the production of different splice forms of RNA, or by formation of double-stranded RNA (RNAi). Descendants of the cell in which the gene was turned on will inherit this activity, even if the original stimulus for gene-activation is no longer present. These genes are often turned on or off by signal transduction, although in some systems where syncytia or gap junctions are important, RNA may spread directly to other cells or nuclei by diffusion. A large amount of RNA and protein is contributed to the zygote by the mother during oogenesis or via nurse cells, resulting in maternal effect phenotypes. A smaller quantity of sperm RNA is transmitted from the father, but there is recent evidence that this epigenetic information can lead to visible changes in several generations of offspring.[56]

MicroRNAs

[edit]MicroRNAs (miRNAs) are members of non-coding RNAs that range in size from 17 to 25 nucleotides. miRNAs regulate a large variety of biological functions in plants and animals.[57] So far, in 2013, about 2000 miRNAs have been discovered in humans and these can be found online in a miRNA database.[58] Each miRNA expressed in a cell may target about 100 to 200 messenger RNAs(mRNAs) that it downregulates.[59] Most of the downregulation of mRNAs occurs by causing the decay of the targeted mRNA, while some downregulation occurs at the level of translation into protein.[60]

It appears that about 60% of human protein coding genes are regulated by miRNAs.[61] Many miRNAs are epigenetically regulated. About 50% of miRNA genes are associated with CpG islands,[57] that may be repressed by epigenetic methylation. Transcription from methylated CpG islands is strongly and heritably repressed.[62] Other miRNAs are epigenetically regulated by either histone modifications or by combined DNA methylation and histone modification.[57]

sRNAs

[edit]sRNAs are small (50–250 nucleotides), highly structured, non-coding RNA fragments found in bacteria. They control gene expression including virulence genes in pathogens and are viewed as new targets in the fight against drug-resistant bacteria.[63] They play an important role in many biological processes, binding to mRNA and protein targets in prokaryotes. Their phylogenetic analyses, for example through sRNA–mRNA target interactions or protein binding properties, are used to build comprehensive databases.[64] sRNA-gene maps based on their targets in microbial genomes are also constructed.[65]

Long non-coding RNAs

[edit]Numerous investigations have demonstrated the pivotal involvement of long non-coding RNAs (lncRNAs) in the regulation of gene expression and chromosomal modifications, thereby exerting significant control over cellular differentiation. These long non-coding RNAs also contribute to genomic imprinting and the inactivation of the X chromosome.[66] In invertebrates such as social insects of honey bees, long non-coding RNAs are detected as a possible epigenetic mechanism via allele-specific genes underlying aggression via reciprocal crosses.[67]

Prions

[edit]Prions are infectious forms of proteins. In general, proteins fold into discrete units that perform distinct cellular functions, but some proteins are also capable of forming an infectious conformational state known as a prion. Although often viewed in the context of infectious disease, prions are more loosely defined by their ability to catalytically convert other native state versions of the same protein to an infectious conformational state. It is in this latter sense that they can be viewed as epigenetic agents capable of inducing a phenotypic change without a modification of the genome.[68]

Fungal prions are considered by some to be epigenetic because the infectious phenotype caused by the prion can be inherited without modification of the genome. PSI+ and URE3, discovered in yeast in 1965 and 1971, are the two best studied of this type of prion.[69][70] Prions can have a phenotypic effect through the sequestration of protein in aggregates, thereby reducing that protein's activity. In PSI+ cells, the loss of the Sup35 protein (which is involved in termination of translation) causes ribosomes to have a higher rate of read-through of stop codons, an effect that results in suppression of nonsense mutations in other genes.[71] The ability of Sup35 to form prions may be a conserved trait. It could confer an adaptive advantage by giving cells the ability to switch into a PSI+ state and express dormant genetic features normally terminated by stop codon mutations.[72][73][74][75]

Prion-based epigenetics has also been observed in Saccharomyces cerevisiae.[76]

Molecular basis

[edit]Epigenetic changes modify the activation of certain genes, but not the genetic code sequence of DNA.[77] The microstructure (not code) of DNA itself or the associated chromatin proteins may be modified, causing activation or silencing. This mechanism enables differentiated cells in a multicellular organism to express only the genes that are necessary for their own activity. Epigenetic changes are preserved when cells divide. Most epigenetic changes only occur within the course of one individual organism's lifetime; however, these epigenetic changes can be transmitted to the organism's offspring through a process called transgenerational epigenetic inheritance. Moreover, if gene inactivation occurs in a sperm or egg cell that results in fertilization, this epigenetic modification may also be transferred to the next generation.[78]

Specific epigenetic processes include paramutation, bookmarking, imprinting, gene silencing, X chromosome inactivation, position effect, DNA methylation reprogramming, transvection, maternal effects, the progress of carcinogenesis, many effects of teratogens, regulation of histone modifications and heterochromatin, and technical limitations affecting parthenogenesis and cloning.[79][80][81]

DNA damage

[edit]DNA damage can also cause epigenetic changes.[82][83][84] DNA damage is very frequent, occurring on average about 60,000 times a day per cell of the human body (see DNA damage (naturally occurring)). These damages are largely repaired, however, epigenetic changes can still remain at the site of DNA repair.[85] In particular, a double strand break in DNA can initiate unprogrammed epigenetic gene silencing both by causing DNA methylation as well as by promoting silencing types of histone modifications (chromatin remodeling - see next section).[86] In addition, the enzyme Parp1 (poly(ADP)-ribose polymerase) and its product poly(ADP)-ribose (PAR) accumulate at sites of DNA damage as part of the repair process.[87] This accumulation, in turn, directs recruitment and activation of the chromatin remodeling protein, ALC1, that can cause nucleosome remodeling.[88] Nucleosome remodeling has been found to cause, for instance, epigenetic silencing of DNA repair gene MLH1.[21][89] DNA damaging chemicals, such as benzene, hydroquinone, styrene, carbon tetrachloride and trichloroethylene, cause considerable hypomethylation of DNA, some through the activation of oxidative stress pathways.[90]

Foods are known to alter the epigenetics of rats on different diets.[91] Some food components epigenetically increase the levels of DNA repair enzymes such as MGMT and MLH1[92] and p53.[93] Other food components can reduce DNA damage, such as soy isoflavones. In one study, markers for oxidative stress, such as modified nucleotides that can result from DNA damage, were decreased by a 3-week diet supplemented with soy.[94] A decrease in oxidative DNA damage was also observed 2 h after consumption of anthocyanin-rich bilberry (Vaccinium myrtillius L.) pomace extract.[95]

DNA repair

[edit]Damage to DNA is very common and is constantly being repaired. Epigenetic alterations can accompany DNA repair of oxidative damage or double-strand breaks. In human cells, oxidative DNA damage occurs about 10,000 times a day and DNA double-strand breaks occur about 10 to 50 times a cell cycle in somatic replicating cells (see DNA damage (naturally occurring)). The selective advantage of DNA repair is to allow the cell to survive in the face of DNA damage. The selective advantage of epigenetic alterations that occur with DNA repair is not clear.[citation needed]

Repair of oxidative DNA damage can alter epigenetic markers

[edit]In the steady state (with endogenous damages occurring and being repaired), there are about 2,400 oxidatively damaged guanines that form 8-oxo-2'-deoxyguanosine (8-OHdG) in the average mammalian cell DNA.[96] 8-OHdG constitutes about 5% of the oxidative damages commonly present in DNA.[97] The oxidized guanines do not occur randomly among all guanines in DNA. There is a sequence preference for the guanine at a methylated CpG site (a cytosine followed by guanine along its 5' → 3' direction and where the cytosine is methylated (5-mCpG)).[98] A 5-mCpG site has the lowest ionization potential for guanine oxidation.[citation needed]

Oxidized guanine has mispairing potential and is mutagenic.[100] Oxoguanine glycosylase (OGG1) is the primary enzyme responsible for the excision of the oxidized guanine during DNA repair. OGG1 finds and binds to an 8-OHdG within a few seconds.[101] However, OGG1 does not immediately excise 8-OHdG. In HeLa cells half maximum removal of 8-OHdG occurs in 30 minutes,[102] and in irradiated mice, the 8-OHdGs induced in the mouse liver are removed with a half-life of 11 minutes.[97]

When OGG1 is present at an oxidized guanine within a methylated CpG site it recruits TET1 to the 8-OHdG lesion (see Figure). This allows TET1 to demethylate an adjacent methylated cytosine. Demethylation of cytosine is an epigenetic alteration.[citation needed]

As an example, when human mammary epithelial cells were treated with H2O2 for six hours, 8-OHdG increased about 3.5-fold in DNA and this caused about 80% demethylation of the 5-methylcytosines in the genome.[99] Demethylation of CpGs in a gene promoter by TET enzyme activity increases transcription of the gene into messenger RNA.[103] In cells treated with H2O2, one particular gene was examined, BACE1.[99] The methylation level of the BACE1 CpG island was reduced (an epigenetic alteration) and this allowed about 6.5 fold increase of expression of BACE1 messenger RNA.[citation needed]

While six-hour incubation with H2O2 causes considerable demethylation of 5-mCpG sites, shorter times of H2O2 incubation appear to promote other epigenetic alterations. Treatment of cells with H2O2 for 30 minutes causes the mismatch repair protein heterodimer MSH2-MSH6 to recruit DNA methyltransferase 1 (DNMT1) to sites of some kinds of oxidative DNA damage.[104] This could cause increased methylation of cytosines (epigenetic alterations) at these locations.

Jiang et al.[105] treated HEK 293 cells with agents causing oxidative DNA damage, (potassium bromate (KBrO3) or potassium chromate (K2CrO4)). Base excision repair (BER) of oxidative damage occurred with the DNA repair enzyme polymerase beta localizing to oxidized guanines. Polymerase beta is the main human polymerase in short-patch BER of oxidative DNA damage. Jiang et al.[105] also found that polymerase beta recruited the DNA methyltransferase protein DNMT3b to BER repair sites. They then evaluated the methylation pattern at the single nucleotide level in a small region of DNA including the promoter region and the early transcription region of the BRCA1 gene. Oxidative DNA damage from bromate modulated the DNA methylation pattern (caused epigenetic alterations) at CpG sites within the region of DNA studied. In untreated cells, CpGs located at −189, −134, −29, −19, +16, and +19 of the BRCA1 gene had methylated cytosines (where numbering is from the messenger RNA transcription start site, and negative numbers indicate nucleotides in the upstream promoter region). Bromate treatment-induced oxidation resulted in the loss of cytosine methylation at −189, −134, +16 and +19 while also leading to the formation of new methylation at the CpGs located at −80, −55, −21 and +8 after DNA repair was allowed.

Homologous recombinational repair alters epigenetic markers

[edit]At least four articles report the recruitment of DNA methyltransferase 1 (DNMT1) to sites of DNA double-strand breaks.[106][85][107][108] During homologous recombinational repair (HR) of the double-strand break, the involvement of DNMT1 causes the two repaired strands of DNA to have different levels of methylated cytosines. One strand becomes frequently methylated at about 21 CpG sites downstream of the repaired double-strand break. The other DNA strand loses methylation at about six CpG sites that were previously methylated downstream of the double-strand break, as well as losing methylation at about five CpG sites that were previously methylated upstream of the double-strand break. When the chromosome is replicated, this gives rise to one daughter chromosome that is heavily methylated downstream of the previous break site and one that is unmethylated in the region both upstream and downstream of the previous break site. With respect to the gene that was broken by the double-strand break, half of the progeny cells express that gene at a high level and in the other half of the progeny cells expression of that gene is repressed. When clones of these cells were maintained for three years, the new methylation patterns were maintained over that time period.[109]

In mice with a CRISPR-mediated homology-directed recombination insertion in their genome there were a large number of increased methylations of CpG sites within the double-strand break-associated insertion.[110]

Non-homologous end joining can cause some epigenetic marker alterations

[edit]Non-homologous end joining (NHEJ) repair of a double-strand break can cause a small number of demethylations of pre-existing cytosine DNA methylations downstream of the repaired double-strand break.[85] Further work by Allen et al.[111] showed that NHEJ of a DNA double-strand break in a cell could give rise to some progeny cells having repressed expression of the gene harboring the initial double-strand break and some progeny having high expression of that gene due to epigenetic alterations associated with NHEJ repair. The frequency of epigenetic alterations causing repression of a gene after an NHEJ repair of a DNA double-strand break in that gene may be about 0.9%.[107]

Techniques used to study epigenetics

[edit]Epigenetic research uses a wide range of molecular biological techniques to further understanding of epigenetic phenomena. These techniques include chromatin immunoprecipitation (together with its large-scale variants ChIP-on-chip and ChIP-Seq), fluorescent in situ hybridization, methylation-sensitive restriction enzymes, DNA adenine methyltransferase identification (DamID) and bisulfite sequencing.[112] Furthermore, the use of bioinformatics methods has a role in computational epigenetics.[112]

Chromatin Immunoprecipitation

[edit]Chromatin Immunoprecipitation (ChIP) has helped bridge the gap between DNA and epigenetic interactions.[113] With the use of ChIP, researchers are able to make findings in regards to gene regulation, transcription mechanisms, and chromatin structure.[113]

Fluorescent in situ hybridization

[edit]Fluorescent in situ hybridization (FISH) is very important to understand epigenetic mechanisms.[114] FISH can be used to find the location of genes on chromosomes, as well as finding noncoding RNAs.[114][115] FISH is predominantly used for detecting chromosomal abnormalities in humans.[115]

Methylation-sensitive restriction enzymes

[edit]Methylation sensitive restriction enzymes paired with PCR is a way to evaluate methylation in DNA - specifically the CpG sites.[116] If DNA is methylated, the restriction enzymes will not cleave the strand.[116] Contrarily, if the DNA is not methylated, the enzymes will cleave the strand and it will be amplified by PCR.[116]

Bisulfite sequencing

[edit]Bisulfite sequencing is another way to evaluate DNA methylation. Cytosine will be changed to uracil from being treated with sodium bisulfite, whereas methylated cytosines will not be affected.[116][117][118]

Nanopore sequencing

[edit]Certain sequencing methods, such as nanopore sequencing, allow sequencing of native DNA. Native (=unamplified) DNA retains the epigenetic modifications which would otherwise be lost during the amplification step. Nanopore basecaller models can distinguish between the signals obtained for epigenetically modified bases and unaltered based and provide an epigenetic profile in addition to the sequencing result.[119]

Structural inheritance

[edit]In ciliates such as Tetrahymena and Paramecium, genetically identical cells show heritable differences in the patterns of ciliary rows on their cell surface. Experimentally altered patterns can be transmitted to daughter cells. It seems existing structures act as templates for new structures. The mechanisms of such inheritance are unclear, but reasons exist to assume that multicellular organisms also use existing cell structures to assemble new ones.[120][121][122]

Nucleosome positioning

[edit]Eukaryotic genomes have numerous nucleosomes. Nucleosome position is not random, and determine the accessibility of DNA to regulatory proteins. Promoters active in different tissues have been shown to have different nucleosome positioning features.[123] This determines differences in gene expression and cell differentiation. It has been shown that at least some nucleosomes are retained in sperm cells (where most but not all histones are replaced by protamines). Thus nucleosome positioning is to some degree inheritable. Recent studies have uncovered connections between nucleosome positioning and other epigenetic factors, such as DNA methylation and hydroxymethylation.[124]

Histone variants

[edit]Different histone variants are incorporated into specific regions of the genome non-randomly. Their differential biochemical characteristics can affect genome functions via their roles in gene regulation,[125] and maintenance of chromosome structures.[126]

Genomic architecture

[edit]The three-dimensional configuration of the genome (the 3D genome) is complex, dynamic and crucial for regulating genomic function and nuclear processes such as DNA replication, transcription and DNA-damage repair.[127]

Functions and consequences

[edit]In the brain

[edit]Memory

[edit]Memory formation and maintenance are due to epigenetic alterations that cause the required dynamic changes in gene transcription that create and renew memory in neurons.[30]

An event can set off a chain of reactions that result in altered methylations of a large set of genes in neurons, which give a representation of the event, a memory.[30]

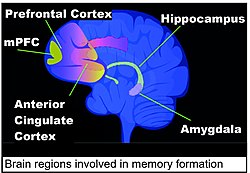

Areas of the brain important in the formation of memories include the hippocampus, medial prefrontal cortex (mPFC), anterior cingulate cortex and amygdala, as shown in the diagram of the human brain in this section.[128]

When a strong memory is created, as in a rat subjected to contextual fear conditioning (CFC), one of the earliest events to occur is that more than 100 DNA double-strand breaks are formed by topoisomerase IIB in neurons of the hippocampus and the medial prefrontal cortex (mPFC).[129] These double-strand breaks are at specific locations that allow activation of transcription of immediate early genes (IEGs) that are important in memory formation, allowing their expression in mRNA, with peak mRNA transcription at seven to ten minutes after CFC.[129][130]

Two important IEGs in memory formation are EGR1[131] and the alternative promoter variant of DNMT3A, DNMT3A2.[132] EGR1 protein binds to DNA at its binding motifs, 5′-GCGTGGGCG-3′ or 5′-GCGGGGGCGG-3', and there are about 12,000 genome locations at which EGR1 protein can bind.[133] EGR1 protein binds to DNA in gene promoter and enhancer regions. EGR1 recruits the demethylating enzyme TET1 to an association, and brings TET1 to about 600 locations on the genome where TET1 can then demethylate and activate the associated genes.[133]

The DNA methyltransferases DNMT3A1, DNMT3A2 and DNMT3B can all methylate cytosines (see image this section) at CpG sites in or near the promoters of genes. As shown by Manzo et al.,[134] these three DNA methyltransferases differ in their genomic binding locations and DNA methylation activity at different regulatory sites. Manzo et al. located 3,970 genome regions exclusively enriched for DNMT3A1, 3,838 regions for DNMT3A2 and 3,432 regions for DNMT3B. When DNMT3A2 is newly induced as an IEG (when neurons are activated), many new cytosine methylations occur, presumably in the target regions of DNMT3A2. Oliviera et al.[132] found that the neuronal activity-inducible IEG levels of Dnmt3a2 in the hippocampus determined the ability to form long-term memories.

Rats form long-term associative memories after contextual fear conditioning (CFC).[135] Duke et al.[29] found that 24 hours after CFC in rats, in hippocampus neurons, 2,097 genes (9.17% of the genes in the rat genome) had altered methylation. When newly methylated cytosines are present in CpG sites in the promoter regions of genes, the genes are often repressed, and when newly demethylated cytosines are present the genes may be activated.[136] After CFC, there were 1,048 genes with reduced mRNA expression and 564 genes with upregulated mRNA expression. Similarly, when mice undergo CFC, one hour later in the hippocampus region of the mouse brain there are 675 demethylated genes and 613 hypermethylated genes.[137] However, memories do not remain in the hippocampus, but after four or five weeks the memories are stored in the anterior cingulate cortex.[138] In the studies on mice after CFC, Halder et al.[137] showed that four weeks after CFC there were at least 1,000 differentially methylated genes and more than 1,000 differentially expressed genes in the anterior cingulate cortex, while at the same time the altered methylations in the hippocampus were reversed.

The epigenetic alteration of methylation after a new memory is established creates a different pool of nuclear mRNAs. As reviewed by Bernstein,[30] the epigenetically determined new mix of nuclear mRNAs are often packaged into neuronal granules, or messenger RNP, consisting of mRNA, small and large ribosomal subunits, translation initiation factors and RNA-binding proteins that regulate mRNA function. These neuronal granules are transported from the neuron nucleus and are directed, according to 3′ untranslated regions of the mRNA in the granules (their "zip codes"), to neuronal dendrites. Roughly 2,500 mRNAs may be localized to the dendrites of hippocampal pyramidal neurons and perhaps 450 transcripts are in excitatory presynaptic nerve terminals (dendritic spines). The altered assortments of transcripts (dependent on epigenetic alterations in the neuron nucleus) have different sensitivities in response to signals, which is the basis of altered synaptic plasticity. Altered synaptic plasticity is often considered the neurochemical foundation of learning and memory.

Aging

[edit]Epigenetics play a major role in brain aging and age-related cognitive decline, with relevance to life extension.[139][140][141][142][143]

Other and general

[edit]In adulthood, changes in the epigenome are important for various higher cognitive functions. Dysregulation of epigenetic mechanisms is implicated in neurodegenerative disorders and diseases. Epigenetic modifications in neurons are dynamic and reversible.[144] Epigenetic regulation impacts neuronal action, affecting learning, memory, and other cognitive processes.[145]

Early events, including during embryonic development, can influence development, cognition, and health outcomes through epigenetic mechanisms.[146]

Epigenetic mechanisms have been proposed as "a potential molecular mechanism for effects of endogenous hormones on the organization of developing brain circuits".[147]

Nutrients could interact with the epigenome to "protect or boost cognitive processes across the lifespan".[148][149]

A review suggests neurobiological effects of physical exercise via epigenetics seem "central to building an 'epigenetic memory' to influence long-term brain function and behavior" and may even be heritable.[150]

With the axo-ciliary synapse, there is communication between serotonergic axons and antenna-like primary cilia of CA1 pyramidal neurons that alters the neuron's epigenetic state in the nucleus via the signalling distinct from that at the plasma membrane (and longer-term).[151][152]

Epigenetics also play a major role in the brain evolution in and to humans.[153]

Development

[edit]Developmental epigenetics can be divided into predetermined and probabilistic epigenesis. Predetermined epigenesis is a unidirectional movement from structural development in DNA to the functional maturation of the protein. "Predetermined" here means that development is scripted and predictable. Probabilistic epigenesis on the other hand is a bidirectional structure-function development with experiences and external molding development.[154]

Somatic epigenetic inheritance, particularly through DNA and histone covalent modifications and nucleosome repositioning, is very important in the development of multicellular eukaryotic organisms.[124] The genome sequence is static (with some notable exceptions), but cells differentiate into many different types, which perform different functions, and respond differently to the environment and intercellular signaling. Thus, as individuals develop, morphogens activate or silence genes in an epigenetically heritable fashion, giving cells a memory. In mammals, most cells terminally differentiate, with only stem cells retaining the ability to differentiate into several cell types ("totipotency" and "multipotency"). In mammals, some stem cells continue producing newly differentiated cells throughout life, such as in neurogenesis, but mammals are not able to respond to loss of some tissues, for example, the inability to regenerate limbs, which some other animals are capable of. Epigenetic modifications regulate the transition from neural stem cells to glial progenitor cells (for example, differentiation into oligodendrocytes is regulated by the deacetylation and methylation of histones).[155] Unlike animals, plant cells do not terminally differentiate, remaining totipotent with the ability to give rise to a new individual plant. While plants do utilize many of the same epigenetic mechanisms as animals, such as chromatin remodeling, it has been hypothesized that some kinds of plant cells do not use or require "cellular memories", resetting their gene expression patterns using positional information from the environment and surrounding cells to determine their fate.[156]

Epigenetic changes can occur in response to environmental exposure – for example, maternal dietary supplementation with genistein (250 mg/kg) have epigenetic changes affecting expression of the agouti gene, which affects their fur color, weight, and propensity to develop cancer.[157][158][159] Ongoing research is focused on exploring the impact of other known teratogens, such as diabetic embryopathy, on methylation signatures.[160]

Controversial results from one study suggested that traumatic experiences might produce an epigenetic signal that is capable of being passed to future generations. Mice were trained, using foot shocks, to fear a cherry blossom odor. The investigators reported that the mouse offspring had an increased aversion to this specific odor.[161][162] They suggested epigenetic changes that increase gene expression, rather than in DNA itself, in a gene, M71, that governs the functioning of an odor receptor in the nose that responds specifically to this cherry blossom smell. There were physical changes that correlated with olfactory (smell) function in the brains of the trained mice and their descendants. Several criticisms were reported, including the study's low statistical power as evidence of some irregularity such as bias in reporting results.[163] Due to limits of sample size, there is a probability that an effect will not be demonstrated to within statistical significance even if it exists. The criticism suggested that the probability that all the experiments reported would show positive results if an identical protocol was followed, assuming the claimed effects exist, is merely 0.4%. The authors also did not indicate which mice were siblings, and treated all of the mice as statistically independent.[164] The original researchers pointed out negative results in the paper's appendix that the criticism omitted in its calculations, and undertook to track which mice were siblings in the future.[165]

Transgenerational

[edit]Epigenetic mechanisms were a necessary part of the evolutionary origin of cell differentiation.[166][need quotation to verify] Although epigenetics in multicellular organisms is generally thought to be a mechanism involved in differentiation, with epigenetic patterns "reset" when organisms reproduce, there have been some observations of transgenerational epigenetic inheritance (e.g., the phenomenon of paramutation observed in maize). Although most of these multigenerational epigenetic traits are gradually lost over several generations, the possibility remains that multigenerational epigenetics could be another aspect to evolution and adaptation. As mentioned above, some define epigenetics as heritable.

A sequestered germ line or Weismann barrier is specific to animals, and epigenetic inheritance is more common in plants and microbes. Eva Jablonka, Marion J. Lamb and Étienne Danchin have argued that these effects may require enhancements to the standard conceptual framework of the modern synthesis and have called for an extended evolutionary synthesis.[167][168][169] Other evolutionary biologists, such as John Maynard Smith, have incorporated epigenetic inheritance into population-genetics models[170] or are openly skeptical of the extended evolutionary synthesis (Michael Lynch).[171] Thomas Dickins and Qazi Rahman state that epigenetic mechanisms such as DNA methylation and histone modification are genetically inherited under the control of natural selection and therefore fit under the earlier "modern synthesis".[172]

Two important ways in which epigenetic inheritance can differ from traditional genetic inheritance, with important consequences for evolution, are:

- rates of epimutation can be much faster than rates of mutation[173]

- the epimutations are more easily reversible[174]

In plants, heritable DNA methylation mutations are 100,000 times more likely to occur compared to DNA mutations.[175] An epigenetically inherited element such as the PSI+ system can act as a "stop-gap", good enough for short-term adaptation that allows the lineage to survive for long enough for mutation and/or recombination to genetically assimilate the adaptive phenotypic change.[176] The existence of this possibility increases the evolvability of a species.

More than 100 cases of transgenerational epigenetic inheritance phenomena have been reported in a wide range of organisms, including prokaryotes, plants, and animals.[177] For instance, mourning-cloak butterflies will change color through hormone changes in response to experimentation of varying temperatures.[178]

The filamentous fungus Neurospora crassa is a prominent model system for understanding the control and function of cytosine methylation. In this organism, DNA methylation is associated with relics of a genome-defense system called RIP (repeat-induced point mutation) and silences gene expression by inhibiting transcription elongation.[179]

The yeast prion PSI is generated by a conformational change of a translation termination factor, which is then inherited by daughter cells. This can provide a survival advantage under adverse conditions, exemplifying epigenetic regulation which enables unicellular organisms to respond rapidly to environmental stress. Prions can be viewed as epigenetic agents capable of inducing a phenotypic change without modification of the genome.[180]

Direct detection of epigenetic marks in microorganisms is possible with single molecule real time sequencing, in which polymerase sensitivity allows for measuring methylation and other modifications as a DNA molecule is being sequenced.[181] Several projects have demonstrated the ability to collect genome-wide epigenetic data in bacteria.[182][183][184][185]

Epigenetics in bacteria

[edit]

While epigenetics is of fundamental importance in eukaryotes, especially metazoans, it plays a different role in bacteria.[186] Most importantly, eukaryotes use epigenetic mechanisms primarily to regulate gene expression which bacteria rarely do. However, bacteria make widespread use of postreplicative DNA methylation for the epigenetic control of DNA-protein interactions. Bacteria also use DNA adenine methylation (rather than DNA cytosine methylation) as an epigenetic signal. DNA adenine methylation is important in bacteria virulence in organisms such as Escherichia coli, Salmonella, Vibrio, Yersinia, Haemophilus, and Brucella. In Alphaproteobacteria, methylation of adenine regulates the cell cycle and couples gene transcription to DNA replication. In Gammaproteobacteria, adenine methylation provides signals for DNA replication, chromosome segregation, mismatch repair, packaging of bacteriophage, transposase activity and regulation of gene expression.[180][187] There exists a genetic switch controlling Streptococcus pneumoniae (the pneumococcus) that allows the bacterium to randomly change its characteristics into six alternative states that could pave the way to improved vaccines. Each form is randomly generated by a phase variable methylation system. The ability of the pneumococcus to cause deadly infections is different in each of these six states. Similar systems exist in other bacterial genera.[188] In Bacillota such as Clostridioides difficile, adenine methylation regulates sporulation, biofilm formation and host-adaptation.[189]

Medicine

[edit]Epigenetics has many and varied potential medical applications.[190]

Twins

[edit]Direct comparisons of identical twins constitute an optimal model for interrogating environmental epigenetics. In the case of humans with different environmental exposures, monozygotic (identical) twins were epigenetically indistinguishable during their early years, while older twins had remarkable differences in the overall content and genomic distribution of 5-methylcytosine DNA and histone acetylation.[10] The twin pairs who had spent less of their lifetime together and/or had greater differences in their medical histories were those who showed the largest differences in their levels of 5-methylcytosine DNA and acetylation of histones H3 and H4.[191]

Dizygotic (fraternal) and monozygotic (identical) twins show evidence of epigenetic influence in humans.[191][192][193] DNA sequence differences that would be abundant in a singleton-based study do not interfere with the analysis. Environmental differences can produce long-term epigenetic effects, and different developmental monozygotic twin subtypes may be different with respect to their susceptibility to be discordant from an epigenetic point of view.[194]

A high-throughput study, which denotes technology that looks at extensive genetic markers, focused on epigenetic differences between monozygotic twins to compare global and locus-specific changes in DNA methylation and histone modifications in a sample of 40 monozygotic twin pairs.[191] In this case, only healthy twin pairs were studied, but a wide range of ages was represented, between 3 and 74 years. One of the major conclusions from this study was that there is an age-dependent accumulation of epigenetic differences between the two siblings of twin pairs. This accumulation suggests the existence of epigenetic "drift". Epigenetic drift is the term given to epigenetic modifications as they occur as a direct function with age. While age is a known risk factor for many diseases, age-related methylation has been found to occur differentially at specific sites along the genome. Over time, this can result in measurable differences between biological and chronological age. Epigenetic changes have been found to be reflective of lifestyle and may act as functional biomarkers of disease before clinical threshold is reached.[195]

A more recent study, where 114 monozygotic twins and 80 dizygotic twins were analyzed for the DNA methylation status of around 6000 unique genomic regions, concluded that epigenetic similarity at the time of blastocyst splitting may also contribute to phenotypic similarities in monozygotic co-twins. This supports the notion that microenvironment at early stages of embryonic development can be quite important for the establishment of epigenetic marks.[192] Congenital genetic disease is well understood and it is clear that epigenetics can play a role, for example, in the case of Angelman syndrome and Prader–Willi syndrome. These are normal genetic diseases caused by gene deletions or inactivation of the genes but are unusually common because individuals are essentially hemizygous because of genomic imprinting, and therefore a single gene knock out is sufficient to cause the disease, where most cases would require both copies to be knocked out.[196]

Genomic imprinting

[edit]Some human disorders are associated with genomic imprinting, a phenomenon in mammals where the father and mother contribute different epigenetic patterns for specific genomic loci in their germ cells.[197] The best-known case of imprinting in human disorders is that of Angelman syndrome and Prader–Willi syndrome – both can be produced by the same genetic mutation, chromosome 15q partial deletion, and the particular syndrome that will develop depends on whether the mutation is inherited from the child's mother or from their father.[198]

In the Överkalix study, paternal (but not maternal) grandsons[199] of Swedish men who were exposed during preadolescence to famine in the 19th century were less likely to die of cardiovascular disease. If food was plentiful, then diabetes mortality in the grandchildren increased, suggesting that this was a transgenerational epigenetic inheritance.[200] The opposite effect was observed for females – the paternal (but not maternal) granddaughters of women who experienced famine while in the womb (and therefore while their eggs were being formed) lived shorter lives on average.[201]

Examples of drugs altering gene expression from epigenetic events

[edit]The use of beta-lactam antibiotics can alter glutamate receptor activity and the action of cyclosporine on multiple transcription factors. Additionally, lithium can impact autophagy of aberrant proteins, and opioid drugs via chronic use can increase the expression of genes associated with addictive phenotypes.[202]

Parental nutrition, in utero exposure to stress or endocrine disrupting chemicals,[203] male-induced maternal effects such as the attraction of differential mate quality, and maternal as well as paternal age, and offspring gender could all possibly influence whether a germline epimutation is ultimately expressed in offspring and the degree to which intergenerational inheritance remains stable throughout posterity.[204] However, whether and to what extent epigenetic effects can be transmitted across generations remains unclear, particularly in humans.[205][206]

Addiction

[edit]Addiction is a disorder of the brain's reward system which arises through transcriptional and neuroepigenetic mechanisms and occurs over time from chronically high levels of exposure to an addictive stimulus (e.g., morphine, cocaine, sexual intercourse, gambling).[207][208][209] Transgenerational epigenetic inheritance of addictive phenotypes has been noted to occur in preclinical studies.[210][211] However, robust evidence in support of the persistence of epigenetic effects across multiple generations has yet to be established in humans; for example, an epigenetic effect of prenatal exposure to smoking that is observed in great-grandchildren who had not been exposed.[205]

Research

[edit]The two forms of heritable information, namely genetic and epigenetic, are collectively called dual inheritance. Members of the APOBEC/AID family of cytosine deaminases may concurrently influence genetic and epigenetic inheritance using similar molecular mechanisms, and may be a point of crosstalk between these conceptually compartmentalized processes.[212]

Fluoroquinolone antibiotics induce epigenetic changes in mammalian cells through iron chelation. This leads to epigenetic effects through inhibition of α-ketoglutarate-dependent dioxygenases that require iron as a co-factor.[213]

Various pharmacological agents are applied for the production of induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSC) or maintain the embryonic stem cell (ESC) phenotypic via epigenetic approach. Adult stem cells like bone marrow stem cells have also shown a potential to differentiate into cardiac competent cells when treated with G9a histone methyltransferase inhibitor BIX01294.[214][215]

Cell plasticity, which is the adaptation of cells to stimuli without changes in their genetic code, requires epigenetic changes. These have been observed in cell plasticity in cancer cells during epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition[216] and also in immune cells, such as macrophages.[217] Interestingly, metabolic changes underlie these adaptations, since various metabolites play crucial roles in the chemistry of epigenetic marks. This includes for instance alpha-ketoglutarate, which is required for histone demethylation, and acetyl-Coenzyme A, which is required for histone acetylation.

Epigenome editing

[edit]Epigenetic regulation of gene expression that could be altered or used in epigenome editing are or include mRNA/lncRNA modification, DNA methylation modification and histone modification.[218][219][220]

CpG sites, SNPs and biological traits

[edit]Methylation is a widely characterized mechanism of genetic regulation that can determine biological traits. However, strong experimental evidences correlate methylation patterns in SNPs as an important additional feature for the classical activation/inhibition epigenetic dogma. Molecular interaction data, supported by colocalization analyses, identify multiple nuclear regulatory pathways, linking sequence variation to disturbances in DNA methylation and molecular and phenotypic variation.[221]

UBASH3B locus

[edit]UBASH3B encodes a protein with tyrosine phosphatase activity, which has been previously linked to advanced neoplasia.[222] SNP rs7115089 was identified as influencing DNA methylation and expression of this locus, as well as and Body Mass Index (BMI).[221] In fact, SNP rs7115089 is strongly associated with BMI[223] and with genetic variants linked to other cardiovascular and metabolic traits in GWASs.[224][225][226] New studies suggesting UBASH3B as a potential mediator of adiposity and cardiometabolic disease.[221] In addition, animal models demonstrated that UBASH3B expression is an indicator of caloric restriction that may drive programmed susceptibility to obesity and it is associated with other measures of adiposity in human peripherical blood.[227]

NFKBIE locus

[edit]SNP rs730775 is located in the first intron of NFKBIE and is a cis eQTL for NFKBIE in whole blood.[221] Nuclear factor (NF)-κB inhibitor ε (NFKBIE) directly inhibits NF-κB1 activity and is significantly co-expressed with NF-κB1, also, it is associated with rheumatoid arthritis.[228] Colocalization analysis supports that variants for the majority of the CpG sites in SNP rs730775 cause genetic variation at the NFKBIE locus which is suggestible linked to rheumatoid arthritis through trans acting regulation of DNA methylation by NF-κB.[221]

FADS1 locus

[edit]Fatty acid desaturase 1 (FADS1) is a key enzyme in the metabolism of fatty acids.[229] Moreover, rs174548 in the FADS1 gene shows increased correlation with DNA methylation in people with high abundance of CD8+ T cells.[221] SNP rs174548 is strongly associated with concentrations of arachidonic acid and other metabolites in fatty acid metabolism,[230][231] blood eosinophil counts.[232] and inflammatory diseases such as asthma.[233] Interaction results indicated a correlation between rs174548 and asthma, providing new insights about fatty acid metabolism in CD8+ T cells with immune phenotypes.[221]

Pseudoscience

[edit]As epigenetics is in the early stages of development as a science and is surrounded by sensationalism in the public media, David Gorski and geneticist Adam Rutherford have advised caution against the proliferation of false and pseudoscientific conclusions by new age authors making unfounded suggestions that a person's genes and health can be manipulated by mind control. Misuse of the scientific term by quack authors has produced misinformation among the general public.[2][234]

See also

[edit]- Baldwin effect

- Behavioral epigenetics

- Biological effects of radiation on the epigenome

- Computational epigenetics

- Contribution of epigenetic modifications to evolution

- DAnCER database (2010)

- Epigenesis (biology)

- Epigenetics in forensic science

- Epigenetics of autoimmune disorders

- Epiphenotyping

- Epigenetic therapy

- Epigenetics of neurodegenerative diseases

- Genetics

- Lamarckism

- Nutriepigenomics

- Position-effect variegation

- Preformationism

- Somatic epitype

- Synthetic genetic array

- Sleep epigenetics

- Transcriptional memory

- Transgenerational epigenetic inheritance

References

[edit]- ^ Dupont C, Armant DR, Brenner CA (September 2009). "Epigenetics: definition, mechanisms and clinical perspective". Seminars in Reproductive Medicine. 27 (5): 351–7. doi:10.1055/s-0029-1237423. PMC 2791696. PMID 19711245.

In the original sense of this definition, epigenetics referred to all molecular pathways modulating the expression of a genotype into a particular phenotype. Over the following years, with the rapid growth of genetics, the meaning of the word has gradually narrowed. Epigenetics has been defined and today is generally accepted as 'the study of changes in gene function that are mitotically and/or meiotically heritable and that do not entail a change in DNA sequence.'

- ^ a b Rutherford A (19 July 2015). "Beware the pseudo gene genies". The Guardian.

- ^ Deans C, Maggert KA (April 2015). "What do you mean, "epigenetic"?". Genetics. 199 (4): 887–896. doi:10.1534/genetics.114.173492. PMC 4391566. PMID 25855649.

- ^ Kanwal R, Gupta S (April 2012). "Epigenetic modifications in cancer". Clinical Genetics. 81 (4): 303–311. doi:10.1111/j.1399-0004.2011.01809.x. PMC 3590802. PMID 22082348.

- ^ Frías-Lasserre D, Villagra CA (2017). "The Importance of ncRNAs as Epigenetic Mechanisms in Phenotypic Variation and Organic Evolution". Frontiers in Microbiology. 8 2483. doi:10.3389/fmicb.2017.02483. PMC 5744636. PMID 29312192.

- ^ a b Bird A (May 2007). "Perceptions of epigenetics". Nature. 447 (7143): 396–398. Bibcode:2007Natur.447..396B. doi:10.1038/nature05913. PMID 17522671. S2CID 4357965.

- ^ Hunter P (1 May 2008). "What genes remember". Prospect Magazine. Archived from the original on 1 May 2008. Retrieved 26 July 2012.

- ^ Reik W (May 2007). "Stability and flexibility of epigenetic gene regulation in mammalian development". Nature. 447 (7143): 425–32. Bibcode:2007Natur.447..425R. doi:10.1038/nature05918. PMID 17522676. S2CID 11794102.

- ^ Oxford English Dictionary: "The word is used by W. Harvey, Exercitationes 1651, p. 148, and in the English Anatomical Exercitations 1653, p. 272. It is explained to mean 'partium super-exorientium additamentum', 'the additament of parts budding one out of another'."

- ^ a b Moore DS (2015). The Developing Genome: An Introduction to Behavioral Epigenetics. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-992235-2.[page needed]

- ^ a b Berger SL, Kouzarides T, Shiekhattar R, Shilatifard A (April 2009). "An operational definition of epigenetics". Genes & Development. 23 (7): 781–3. doi:10.1101/gad.1787609. PMC 3959995. PMID 19339683.

- ^ a b "Overview". NIH Roadmap Epigenomics Project. Archived from the original on 21 November 2019. Retrieved 7 December 2013.

- ^ Morange M. La tentative de Nikolai Koltzoff (Koltsov) de lier génétique, embryologie et chimie physique, J. Biosciences. 2011. V. 36. P. 211-214

- ^ Waddington CH (1942). "The epigenotype". Endeavour. 1: 18–20. "For the purpose of a study of inheritance, the relation between phenotypes and genotypes [...] is, from a wider biological point of view, of crucial importance, since it is the kernel of the whole problem of development."

- ^ See preformationism for historical background. Oxford English Dictionary: "the theory that the germ is brought into existence (by successive accretions), and not merely developed, in the process of reproduction. [...] The opposite theory was formerly known as the 'theory of evolution'; to avoid the ambiguity of this name, it is now spoken of chiefly as the 'theory of preformation', sometimes as that of 'encasement' or 'emboîtement'."

- ^ Waddington CH (2014). The Epigenetics of Birds. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-107-44047-0.[page needed]

- ^ Hall BK (January 2004). "In search of evolutionary developmental mechanisms: the 30-year gap between 1944 and 1974". Journal of Experimental Zoology Part B: Molecular and Developmental Evolution. 302 (1): 5–18. Bibcode:2004JEZ...302....5H. doi:10.1002/jez.b.20002. PMID 14760651.

- ^ Alvarez-Buylla ER, Chaos A, Aldana M, Benítez M, Cortes-Poza Y, Espinosa-Soto C, et al. (3 November 2008). "Floral morphogenesis: stochastic explorations of a gene network epigenetic landscape". PLOS ONE. 3 (11) e3626. Bibcode:2008PLoSO...3.3626A. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0003626. PMC 2572848. PMID 18978941.

- ^ a b Rabajante JF, Babierra AL (March 2015). "Branching and oscillations in the epigenetic landscape of cell-fate determination". Progress in Biophysics and Molecular Biology. 117 (2–3): 240–249. doi:10.1016/j.pbiomolbio.2015.01.006. PMID 25641423. S2CID 2579314.

- ^ Holliday R (January 1990). "DNA methylation and epigenetic inheritance". Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London. Series B, Biological Sciences. 326 (1235): 329–38. Bibcode:1990RSPTB.326..329H. doi:10.1098/rstb.1990.0015. PMID 1968668.

- ^ a b Riggs AD, Martienssen RA, Russo VE (1996). Epigenetic mechanisms of gene regulation. Plainview, NY: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press. pp. 1–4. ISBN 978-0-87969-490-6.[page needed]

- ^ Ledford H (October 2008). "Language: Disputed definitions". Nature. 455 (7216): 1023–8. doi:10.1038/4551023a. PMID 18948925.

- ^ Gibney ER, Nolan CM (July 2010). "Epigenetics and gene expression". Heredity. 105 (1): 4–13. Bibcode:2010Hered.105....4G. doi:10.1038/hdy.2010.54. PMID 20461105. S2CID 31611763.

- ^ Ptashne M (April 2007). "On the use of the word 'epigenetic'". Current Biology. 17 (7): R233-6. Bibcode:2007CBio...17.R233P. doi:10.1016/j.cub.2007.02.030. PMID 17407749. S2CID 17490277.

- ^ Zhang D, Tang Z, Huang H, Zhou G, Cui C, Weng Y, et al. (October 2019). "Metabolic regulation of gene expression by histone lactylation". Nature. 574 (7779): 575–580. Bibcode:2019Natur.574..575Z. doi:10.1038/s41586-019-1678-1. PMC 6818755. PMID 31645732.

- ^ Kumar S, Chinnusamy V, Mohapatra T (2018). "Epigenetics of Modified DNA Bases: 5-Methylcytosine and Beyond". Frontiers in Genetics. 9 640. doi:10.3389/fgene.2018.00640. PMC 6305559. PMID 30619465.

- ^ Greenberg MV, Bourc'his D (October 2019). "The diverse roles of DNA methylation in mammalian development and disease". Nature Reviews. Molecular Cell Biology. 20 (10): 590–607. doi:10.1038/s41580-019-0159-6. PMID 31399642. S2CID 199512037.

- ^ Spitz F, Furlong EE (September 2012). "Transcription factors: from enhancer binding to developmental control". Nat Rev Genet. 13 (9): 613–26. doi:10.1038/nrg3207. PMID 22868264. S2CID 205485256.

- ^ a b Duke CG, Kennedy AJ, Gavin CF, Day JJ, Sweatt JD (July 2017). "Experience-dependent epigenomic reorganization in the hippocampus". Learn Mem. 24 (7): 278–288. doi:10.1101/lm.045112.117. PMC 5473107. PMID 28620075.

- ^ a b c d Bernstein C (2022). "DNA Methylation and Establishing Memory". Epigenet Insights. 15 25168657211072499. doi:10.1177/25168657211072499. PMC 8793415. PMID 35098021.

- ^ a b Rose NR, Klose RJ (December 2014). "Understanding the relationship between DNA methylation and histone lysine methylation". Biochim Biophys Acta. 1839 (12): 1362–72. doi:10.1016/j.bbagrm.2014.02.007. PMC 4316174. PMID 24560929.

- ^ a b Li Y, Chen X, Lu C (May 2021). "The interplay between DNA and histone methylation: molecular mechanisms and disease implications". EMBO Rep. 22 (5) e51803. doi:10.15252/embr.202051803. PMC 8097341. PMID 33844406.

- ^ Bendandi A, Patelli AS, Diaspro A, Rocchia W (2020). "The role of histone tails in nucleosome stability: An electrostatic perspective". Comput Struct Biotechnol J. 18: 2799–2809. doi:10.1016/j.csbj.2020.09.034. PMC 7575852. PMID 33133421.

- ^ Stewart MD, Li J, Wong J (April 2005). "Relationship between histone H3 lysine 9 methylation, transcription repression, and heterochromatin protein 1 recruitment". Molecular and Cellular Biology. 25 (7): 2525–2538. doi:10.1128/MCB.25.7.2525-2538.2005. PMC 1061631. PMID 15767660.

- ^ Khan FA (2014). "Genetic disorders and gene therapy". Biotechnology in Medical Sciences. pp. 264–289. doi:10.1201/b16905-14. ISBN 978-0-429-17411-7.

- ^ Jenuwein T, Laible G, Dorn R, Reuter G (January 1998). "SET domain proteins modulate chromatin domains in eu- and heterochromatin". Cellular and Molecular Life Sciences. 54 (1): 80–93. doi:10.1007/s000180050127. PMC 11147257. PMID 9487389. S2CID 7769686.

- ^ Slotkin RK, Martienssen R (April 2007). "Transposable elements and the epigenetic regulation of the genome". Nature Reviews. Genetics. 8 (4): 272–85. doi:10.1038/nrg2072. PMID 17363976. S2CID 9719784.

- ^ a b Li E, Bestor TH, Jaenisch R (June 1992). "Targeted mutation of the DNA methyltransferase gene results in embryonic lethality". Cell. 69 (6): 915–26. doi:10.1016/0092-8674(92)90611-F. PMID 1606615. S2CID 19879601.

- ^ Robertson KD, Uzvolgyi E, Liang G, Talmadge C, Sumegi J, Gonzales FA, et al. (June 1999). "The human DNA methyltransferases (DNMTs) 1, 3a and 3b: coordinate mRNA expression in normal tissues and overexpression in tumors". Nucleic Acids Research. 27 (11): 2291–8. doi:10.1093/nar/27.11.2291. PMC 148793. PMID 10325416.

- ^ Leonhardt H, Page AW, Weier HU, Bestor TH (November 1992). "A targeting sequence directs DNA methyltransferase to sites of DNA replication in mammalian nuclei" (PDF). Cell. 71 (5): 865–73. doi:10.1016/0092-8674(92)90561-P. PMID 1423634. S2CID 5995820.

- ^ Chuang LS, Ian HI, Koh TW, Ng HH, Xu G, Li BF (September 1997). "Human DNA-(cytosine-5) methyltransferase-PCNA complex as a target for p21WAF1". Science. 277 (5334): 1996–2000. doi:10.1126/science.277.5334.1996. PMID 9302295.

- ^ Robertson KD, Wolffe AP (October 2000). "DNA methylation in health and disease". Nature Reviews. Genetics. 1 (1): 11–9. doi:10.1038/35049533. PMID 11262868. S2CID 1915808.

- ^ Li E, Beard C, Jaenisch R (November 1993). "Role for DNA methylation in genomic imprinting". Nature. 366 (6453): 362–5. Bibcode:1993Natur.366..362L. doi:10.1038/366362a0. PMID 8247133. S2CID 4311091.

- ^ Viens A, Mechold U, Brouillard F, Gilbert C, Leclerc P, Ogryzko V (July 2006). "Analysis of human histone H2AZ deposition in vivo argues against its direct role in epigenetic templating mechanisms". Molecular and Cellular Biology. 26 (14): 5325–35. doi:10.1128/MCB.00584-06. PMC 1592707. PMID 16809769.

- ^ Ogryzko VV (April 2008). "Erwin Schroedinger, Francis Crick and epigenetic stability". Biology Direct. 3: 15. doi:10.1186/1745-6150-3-15. PMC 2413215. PMID 18419815.

- ^ Barbieri I, Kouzarides T (June 2020). "Role of RNA modifications in cancer". Nature Reviews. Cancer. 20 (6): 303–322. doi:10.1038/s41568-020-0253-2. PMID 32300195.

- ^ Jia G, Fu Y, Zhao X, Dai Q, Zheng G, Yang Y, et al. (October 2011). "N6-methyladenosine in nuclear RNA is a major substrate of the obesity-associated FTO". Nature Chemical Biology. 7 (12): 885–7. doi:10.1038/nchembio.687. PMC 3218240. PMID 22002720.

- ^ "New research links common RNA modification to obesity". Physorg.com. Retrieved 26 July 2012.

- ^ Nottke A, Colaiácovo MP, Shi Y (March 2009). "Developmental roles of the histone lysine demethylases". Development. 136 (6): 879–89. doi:10.1242/dev.020966. PMC 2692332. PMID 19234061.

- ^ Rosenfeld JA, Wang Z, Schones DE, Zhao K, DeSalle R, Zhang MQ (March 2009). "Determination of enriched histone modifications in non-genic portions of the human genome". BMC Genomics. 10 143. doi:10.1186/1471-2164-10-143. PMC 2667539. PMID 19335899.

- ^ Sneppen K, Micheelsen MA, Dodd IB (15 April 2008). "Ultrasensitive gene regulation by positive feedback loops in nucleosome modification". Molecular Systems Biology. 4 (1) 182. doi:10.1038/msb.2008.21. PMC 2387233. PMID 18414483.

- ^ "Epigenetic cell memory". Cmol.nbi.dk. Archived from the original on 30 September 2011. Retrieved 26 July 2012.

- ^ Dodd IB, Micheelsen MA, Sneppen K, Thon G (May 2007). "Theoretical analysis of epigenetic cell memory by nucleosome modification". Cell. 129 (4): 813–22. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2007.02.053. PMID 17512413. S2CID 16091877.

- ^ Morris KL (2008). "Epigenetic Regulation of Gene Expression". RNA and the Regulation of Gene Expression: A Hidden Layer of Complexity. Norfolk, England: Caister Academic Press. ISBN 978-1-904455-25-7.[page needed]

- ^ Mattick JS, Amaral PP, Dinger ME, Mercer TR, Mehler MF (January 2009). "RNA regulation of epigenetic processes". BioEssays. 31 (1): 51–9. doi:10.1002/bies.080099. PMID 19154003. S2CID 19293469.

- ^ Choi CQ (25 May 2006). "RNA can be hereditary molecule". The Scientist. Archived from the original on 8 February 2007.

- ^ a b c Wang Z, Yao H, Lin S, Zhu X, Shen Z, Lu G, et al. (April 2013). "Transcriptional and epigenetic regulation of human microRNAs". Cancer Letters. 331 (1): 1–10. doi:10.1016/j.canlet.2012.12.006. PMID 23246373.

- ^ "Browse miRBase by species".

- ^ Lim LP, Lau NC, Garrett-Engele P, Grimson A, Schelter JM, Castle J, et al. (February 2005). "Microarray analysis shows that some microRNAs downregulate large numbers of target mRNAs". Nature. 433 (7027): 769–73. Bibcode:2005Natur.433..769L. doi:10.1038/nature03315. PMID 15685193. S2CID 4430576.