Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Influenza

View on Wikipedia

| Influenza | |

|---|---|

| Other names | flu, grippe (French for flu) |

| |

| Influenza virus | |

| Specialty | Infectious disease |

| Symptoms | Fever, runny nose, sore throat, muscle pain, headache, coughing, fatigue |

| Usual onset | 1–4 days after exposure |

| Duration | 2–8 days |

| Causes | Influenza A, B, and C viruses |

| Prevention | Hand washing, flu vaccines |

| Medication | Antiviral drugs such as oseltamivir |

| Frequency | 1 billion cases of seasonal influenza per year[1] |

| Deaths | 290,000–650,000 deaths per year[1] |

Influenza, commonly known as the flu, is an infectious disease caused by influenza viruses. Symptoms range from mild to severe and often include fever, runny nose, sore throat, muscle pain, headache, coughing, and fatigue. These symptoms begin one to four (typically two) days after exposure to the virus and last for about two to eight days. Diarrhea and vomiting can occur, particularly in children. Influenza may progress to pneumonia from the virus or a subsequent bacterial infection. Other complications include acute respiratory distress syndrome, meningitis, encephalitis, and worsening of pre-existing health problems such as asthma and cardiovascular disease.

There are four types of influenza virus: types A, B, C, and D. Aquatic birds are the primary source of influenza A virus (IAV), which is also widespread in various mammals, including humans and pigs. Influenza B virus (IBV) and influenza C virus (ICV) primarily infect humans, and influenza D virus (IDV) is found in cattle and pigs. Influenza A virus and influenza B virus circulate in humans and cause seasonal epidemics, and influenza C virus causes a mild infection, primarily in children. Influenza D virus can infect humans but is not known to cause illness. In humans, influenza viruses are primarily transmitted through respiratory droplets from coughing and sneezing. Transmission through aerosols and surfaces contaminated by the virus also occur.

Frequent hand washing and covering one's mouth and nose when coughing and sneezing reduce transmission, as does wearing a mask. Annual vaccination can help to provide protection against influenza. Influenza viruses, particularly influenza A virus, evolve quickly, so flu vaccines are updated regularly to match which influenza strains are in circulation. Vaccines provide protection against influenza A virus subtypes H1N1 and H3N2 and one or two influenza B virus subtypes. Influenza infection is diagnosed with laboratory methods such as antibody or antigen tests and a polymerase chain reaction (PCR) to identify viral nucleic acid. The disease can be treated with supportive measures and, in severe cases, with antiviral drugs such as oseltamivir. In healthy individuals, influenza is typically self-limiting and rarely fatal, but it can be deadly in high-risk groups.

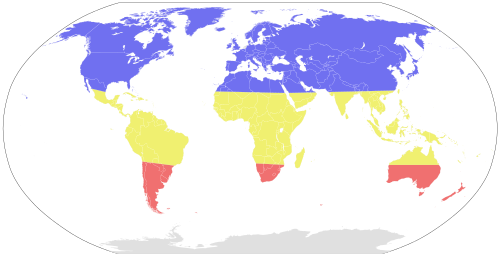

In a typical year, five to 15 percent of the population contracts influenza. There are 3 to 5 million severe cases annually, with up to 650,000 respiratory-related deaths globally each year. Deaths most commonly occur in high-risk groups, including young children, the elderly, and people with chronic health conditions. In temperate regions, the number of influenza cases peaks during winter, whereas in the tropics, influenza can occur year-round. Since the late 1800s, pandemic outbreaks of novel influenza strains have occurred every 10 to 50 years. Five flu pandemics have occurred since 1900: the Spanish flu from 1918 to 1920, which was the most severe; the Asian flu in 1957; the Hong Kong flu in 1968; the Russian flu in 1977; and the swine flu pandemic in 2009.

Signs and symptoms

[edit]

The symptoms of influenza are similar to those of a cold, although usually more severe and less likely to include a runny nose.[5][6] The time between exposure to the virus and development of symptoms (the incubation period) is one to four days, most commonly one to two days. Many infections are asymptomatic.[7] The onset of symptoms is sudden, and initial symptoms are predominately non-specific, including fever, chills, headaches, muscle pain, malaise, loss of appetite, lack of energy, and confusion. These are usually accompanied by respiratory symptoms such as a dry cough, sore or dry throat, hoarse voice, and a stuffy or runny nose. Coughing is the most common symptom.[8] Gastrointestinal symptoms may also occur, including nausea, vomiting, diarrhea,[9] and gastroenteritis,[10] especially in children. The standard influenza symptoms typically last for two to eight days.[11] Some studies suggest influenza can cause long-lasting symptoms in a similar way to long COVID.[12][13][14]

Symptomatic infections are usually mild and limited to the upper respiratory tract, but progression to pneumonia is relatively common. Pneumonia may be caused by the primary viral infection or a secondary bacterial infection. Primary pneumonia is characterized by rapid progression of fever, cough, labored breathing, and low oxygen levels that cause bluish skin. It is especially common among those who have an underlying cardiovascular disease such as rheumatic heart disease. Secondary pneumonia typically has a period of improvement in symptoms for one to three weeks[15] followed by recurrent fever, sputum production, and fluid buildup in the lungs,[8] but can also occur just a few days after influenza symptoms appear.[15] About a third of primary pneumonia cases are followed by secondary pneumonia, which is most frequently caused by the bacteria Streptococcus pneumoniae and Staphylococcus aureus.[7][8]

Virology

[edit]Types of virus

[edit]

Influenza viruses comprise four species, each the sole member of its own genus. The four influenza genera comprise four of the seven genera in the family Orthomyxoviridae. They are:[8][16]

- Influenza A virus, genus Alphainfluenzavirus

- Influenza B virus, genus Betainfluenzavirus

- Influenza C virus, genus Gammainfluenzavirus

- Influenza D virus, genus Deltainfluenzavirus

Influenza A virus is responsible for most cases of severe illness as well as seasonal epidemics and occasional pandemics. It infects people of all ages but tends to cause severe illness disproportionately in the elderly, the very young, and those with chronic health issues. Birds are the primary reservoir of influenza A virus, especially aquatic birds such as ducks, geese, shorebirds, and gulls,[17][18] but the virus also circulates among mammals, including pigs, horses, and marine mammals.

Subtypes of Influenza A are defined by the combination of the antigenic viral proteins haemagglutinin (H) and neuraminidase (N) in the viral envelope; for example, "H1N1" designates an IAV subtype that has a type-1 hemagglutinin (H) protein and a type-1 neuraminidase (N) protein.[19] Almost all possible combinations of H (1 through 16) and N (1 through 11) have been isolated from wild birds.[20][21] In addition H17, H18, N10 and N11 have been found in bats.[22][21] The influenza A virus subtypes in circulation among humans are H1N1 and H3N2.[23]

Influenza B virus mainly infects humans but has been identified in seals, horses, dogs, and pigs.[21] Influenza B virus does not have subtypes like influenza A virus but has two antigenically distinct lineages, termed the B/Victoria/2/1987-like and B/Yamagata/16/1988-like lineages,[8] or simply (B/)Victoria(-like) and (B/)Yamagata(-like).[21][23] Both lineages are in circulation in humans,[8] disproportionately affecting children.[9] However, the B/Yamagata lineage might have become extinct in 2020/2021 due to COVID-19 pandemic measures.[24] Influenza B viruses contribute to seasonal epidemics alongside influenza A viruses but have never been associated with a pandemic.[21]

Influenza C virus, like influenza B virus, is primarily found in humans, though it has been detected in pigs, feral dogs, dromedary camels, cattle, and dogs.[10][21] Influenza C virus infection primarily affects children and is usually asymptomatic[8][9] or has mild cold-like symptoms, though more severe symptoms such as gastroenteritis and pneumonia can occur.[10] Unlike influenza A virus and influenza B virus, influenza C virus has not been a major focus of research pertaining to antiviral drugs, vaccines, and other measures against influenza.[21] Influenza C virus is subclassified into six genetic/antigenic lineages.[10][25]

Influenza D virus has been isolated from pigs and cattle, the latter being the natural reservoir. Infection has also been observed in humans, horses, dromedary camels, and small ruminants such as goats and sheep.[21][25] Influenza D virus is distantly related to influenza C virus. While cattle workers have occasionally tested positive to prior influenza D virus infection, it is not known to cause disease in humans.[8][9][10] Influenza C virus and influenza D virus experience a slower rate of antigenic evolution than influenza A virus and influenza B virus. Because of this antigenic stability, relatively few novel lineages emerge.[25]

Influenza virus nomenclature

[edit]

Every year, millions of influenza virus samples are analysed to monitor changes in the virus' antigenic properties, and to inform the development of vaccines.[26]

To unambiguously describe a specific isolate of virus, researchers use the internationally accepted influenza virus nomenclature,[27] which describes, among other things, the species of animal from which the virus was isolated, and the place and year of collection. As an example – "A/chicken/Nakorn-Patom/Thailand/CU-K2/04(H5N1)":

- "A" stands for the genus of influenza (A, B, C or D).

- "chicken" is the animal species the isolate was found in (note: human isolates lack this component term and are thus identified as human isolates by default)

- "Nakorn-Patom/Thailand" is the place this specific virus was isolated

- "CU-K2" is the laboratory reference number that identifies it from other influenza viruses isolated at the same place and year

- "04" represents the year of isolation 2004

- "H5" stands for the fifth of several known types of the protein hemagglutinin.

- "N1" stands for the first of several known types of the protein neuraminidase.[28]

The nomenclature for influenza B, C and D, which are less variable, is simpler. Examples are B/Santiago/29615/2020 and C/Minnesota/10/2015.[28]

Genome and structure

[edit]

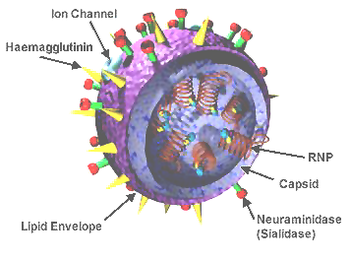

Influenza viruses have a negative-sense, single-stranded RNA genome that is segmented. The negative sense of the genome means it can be used as a template to synthesize messenger RNA (mRNA).[7] Influenza A virus and influenza B virus have eight genome segments that encode 10 major proteins. Influenza C virus and influenza D virus have seven genome segments that encode nine major proteins.[10]

Three segments encode three subunits of an RNA-dependent RNA polymerase (RdRp) complex: PB1, a transcriptase, PB2, which recognizes 5' caps, and PA (P3 for influenza C virus and influenza D virus), an endonuclease.[29] The M1 matrix protein and M2 proton channel share a segment, as do the non-structural protein (NS1) and the nuclear export protein (NEP).[8] For influenza A virus and influenza B virus, hemagglutinin (HA) and neuraminidase (NA) are encoded on one segment each, whereas influenza C virus and influenza D virus encode a hemagglutinin-esterase fusion (HEF) protein on one segment that merges the functions of HA and NA. The final genome segment encodes the viral nucleoprotein (NP).[29] Influenza viruses also encode various accessory proteins, such as PB1-F2 and PA-X, that are expressed through alternative open reading frames[8][30] and which are important in host defense suppression, virulence, and pathogenicity.[31]

The virus particle, called a virion, is pleomorphic and varies between being filamentous, bacilliform, or spherical in shape. Clinical isolates tend to be pleomorphic, whereas strains adapted to laboratory growth typically produce spherical virions. Filamentous virions are about 250 nanometers (nm) by 80 nm, bacilliform 120–250 by 95 nm, and spherical 120 nm in diameter.[32]

The core of the virion comprises one copy of each segment of the genome bound to NP nucleoproteins in separate ribonucleoprotein (RNP) complexes for each segment. There is a copy of the RdRp, all subunits included, bound to each RNP. The genetic material is encapsulated by a layer of M1 matrix protein which provides structural reinforcement to the outer layer, the viral envelope.[33] The envelope comprises a lipid bilayer membrane incorporating HA and NA (or HEF[25]) proteins extending outward from its exterior surface. HA and HEF[25] proteins have a distinct "head" and "stalk" structure. M2 proteins form proton channels through the viral envelope that are required for viral entry and exit. Influenza B viruses contain a surface protein named NB that is anchored in the envelope, but its function is unknown.[8]

Life cycle

[edit]

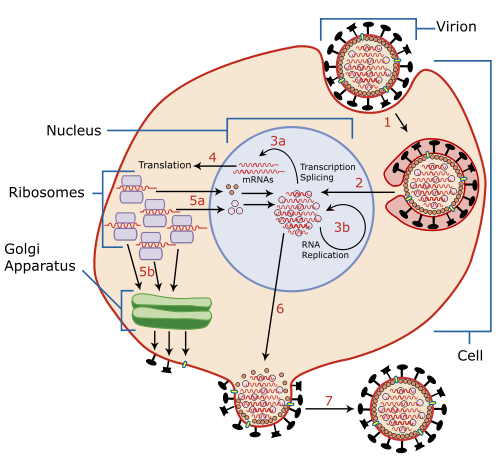

The viral life cycle begins by binding to a target cell. Binding is mediated by the viral HA proteins on the surface of the envelope, which bind to cells that contain sialic acid receptors on the surface of the cell membrane.[8][17][33] For N1 subtypes with the "G147R" mutation and N2 subtypes, the NA protein can initiate entry. Prior to binding, NA proteins promote access to target cells by degrading mucus, which helps to remove extracellular decoy receptors that would impede access to target cells.[33] After binding, the virus is internalized into the cell by an endosome that contains the virion inside it. The endosome is acidified by cellular vATPase[30] to have lower pH, which triggers a conformational change in HA that allows fusion of the viral envelope with the endosomal membrane.[31] At the same time, hydrogen ions diffuse into the virion through M2 ion channels, disrupting internal protein-protein interactions to release RNPs into the host cell's cytosol. The M1 protein shell surrounding RNPs is degraded, fully uncoating RNPs in the cytosol.[30][33]

RNPs are then imported into the nucleus with the help of viral localization signals. There, the viral RNA polymerase transcribes mRNA using the genomic negative-sense strand as a template. The polymerase snatches 5' caps for viral mRNA from cellular RNA to prime mRNA synthesis and the 3'-end of mRNA is polyadenylated at the end of transcription.[29] Once viral mRNA is transcribed, it is exported out of the nucleus and translated by host ribosomes in a cap-dependent manner to synthesize viral proteins.[30] RdRp also synthesizes complementary positive-sense strands of the viral genome in a complementary RNP complex which are then used as templates by viral polymerases to synthesize copies of the negative-sense genome.[8][33] During these processes, RdRps of avian influenza viruses (AIVs) function optimally at a higher temperature than mammalian influenza viruses.[11]

Newly synthesized viral polymerase subunits and NP proteins are imported to the nucleus to further increase the rate of viral replication and form RNPs.[29] HA, NA, and M2 proteins are trafficked with the aid of M1 and NEP proteins[31] to the cell membrane through the Golgi apparatus[29] and inserted into the cell's membrane. Viral non-structural proteins including NS1, PB1-F2, and PA-X regulate host cellular processes to disable antiviral responses.[8][31][33] PB1-F2 also interacts with PB1 to keep polymerases in the nucleus longer.[18] M1 and NEP proteins localize to the nucleus during the later stages of infection, bind to viral RNPs and mediate their export to the cytoplasm where they migrate to the cell membrane with the aid of recycled endosomes and are bundled into the segments of the genome.[8][33]

Progeny viruses leave the cell by budding from the cell membrane, which is initiated by the accumulation of M1 proteins at the cytoplasmic side of the membrane. The viral genome is incorporated inside a viral envelope derived from portions of the cell membrane that have HA, NA, and M2 proteins. At the end of budding, HA proteins remain attached to cellular sialic acid until they are cleaved by the sialidase activity of NA proteins. The virion is then released from the cell. The sialidase activity of NA also cleaves any sialic acid residues from the viral surface, which helps prevent newly assembled viruses from aggregating near the cell surface and improving infectivity.[8][33] Similar to other aspects of influenza replication, optimal NA activity is temperature- and pH-dependent.[11] Ultimately, presence of large quantities of viral RNA in the cell triggers apoptosis (programmed cell death), which is initiated by cellular factors to restrict viral replication.[30]

Antigenic drift and shift

[edit]

Two key processes that influenza viruses evolve through are antigenic drift and antigenic shift. Antigenic drift is when an influenza virus' antigens change due to the gradual accumulation of mutations in the antigen's (HA or NA) gene.[17] This can occur in response to evolutionary pressure exerted by the host immune response. Antigenic drift is especially common for the HA protein, in which just a few amino acid changes in the head region can constitute antigenic drift.[23][25] The result is the production of novel strains that can evade pre-existing antibody-mediated immunity.[8][9] Antigenic drift occurs in all influenza species but is slower in B than A and slowest in C and D.[25] Antigenic drift is a major cause of seasonal influenza,[34] and requires that flu vaccines be updated annually. HA is the main component of inactivated vaccines, so surveillance monitors antigenic drift of this antigen among circulating strains. Antigenic evolution of influenza viruses of humans appears to be faster than in swine and equines. In wild birds, within-subtype antigenic variation appears to be limited but has been observed in poultry.[8][9]

Antigenic shift is a sudden, drastic change in an influenza virus' antigen, usually HA. During antigenic shift, antigenically different strains that infect the same cell can reassort genome segments with each other, producing hybrid progeny. Since all influenza viruses have segmented genomes, all are capable of reassortment.[10][25] Antigenic shift only occurs among influenza viruses of the same genus[29] and most commonly occurs among influenza A viruses. In particular, reassortment is very common in AIVs, creating a large diversity of influenza viruses in birds, but is uncommon in human, equine, and canine lineages.[35] Pigs, bats, and quails have receptors for both mammalian and avian influenza A viruses, so they are potential "mixing vessels" for reassortment.[21] If an animal strain reassorts with a human strain,[23] then a novel strain can emerge that is capable of human-to-human transmission. This has caused pandemics, but only a limited number, so it is difficult to predict when the next will happen.[8][9] The Global Influenza Surveillance and Response System of the World Health Organization (GISRS) tests several millions of specimens annually to monitor the spread and evolution of influenza viruses.[36][26]

Mechanism

[edit]Transmission

[edit]People who are infected can transmit influenza viruses through breathing, talking, coughing, and sneezing, which spread respiratory droplets and aerosols that contain virus particles into the air. A person susceptible to infection can contract influenza by coming into contact with these particles.[15][37] Respiratory droplets are relatively large and travel less than two meters before falling onto nearby surfaces. Aerosols are smaller and remain suspended in the air longer, so they take longer to settle and can travel further.[37][38] Inhalation of aerosols can lead to infection,[39] but most transmission is in the area about two meters around an infected person via respiratory droplets[7] that come into contact with mucosa of the upper respiratory tract.[39] Transmission through contact with a person, bodily fluids, or intermediate objects (fomites) can also occur,[7][37] since influenza viruses can survive for hours on non-porous surfaces.[38] If one's hands are contaminated, then touching one's face can cause infection.[40]

Influenza is usually transmissible from one day before the onset of symptoms to 5–7 days after.[9] In healthy adults, the virus is shed for up to 3–5 days. In children and the immunocompromised, the virus may be transmissible for several weeks.[7] Children ages 2–17 are considered to be the primary and most efficient spreaders of influenza.[8][9] Children who have not had multiple prior exposures to influenza viruses shed the virus at greater quantities and for a longer duration than other children.[8] People at risk of exposure to influenza include health care workers, social care workers, and those who live with or care for people vulnerable to influenza. In long-term care facilities, the flu can spread rapidly.[9] A variety of factors likely encourage influenza transmission, including lower temperature, lower absolute and relative humidity, less ultraviolet radiation from the sun,[39][41] and crowding.[37] Influenza viruses that infect the upper respiratory tract like H1N1 tend to be more mild but more transmissible, whereas those that infect the lower respiratory tract like H5N1 tend to cause more severe illness but are less contagious.[7]

Pathophysiology

[edit]

In humans, influenza viruses first cause infection by infecting epithelial cells in the respiratory tract. Illness during infection is primarily the result of lung inflammation and compromise caused by epithelial cell infection and death, combined with inflammation caused by the immune system's response to infection. Non-respiratory organs can become involved, but the mechanisms by which influenza is involved in these cases are unknown. Severe respiratory illness can be caused by multiple, non-exclusive mechanisms, including obstruction of the airways, loss of alveolar structure, loss of lung epithelial integrity due to epithelial cell infection and death, and degradation of the extracellular matrix that maintains lung structure. In particular, alveolar cell infection appears to drive severe symptoms since this results in impaired gas exchange and enables viruses to infect endothelial cells, which produce large quantities of pro-inflammatory cytokines.[15]

Pneumonia caused by influenza viruses is characterized by high levels of viral replication in the lower respiratory tract, accompanied by a strong pro-inflammatory response called a cytokine storm.[8] Infection with H5N1 or H7N9 especially produces high levels of pro-inflammatory cytokines.[17] In bacterial infections, early depletion of macrophages during influenza creates a favorable environment in the lungs for bacterial growth since these white blood cells are important in responding to bacterial infection. Host mechanisms to encourage tissue repair may inadvertently allow bacterial infection. Infection also induces production of systemic glucocorticoids that can reduce inflammation to preserve tissue integrity but allow increased bacterial growth.[15]

The pathophysiology of influenza is significantly influenced by which receptors influenza viruses bind to during entry into cells. Mammalian influenza viruses preferentially bind to sialic acids connected to the rest of the oligosaccharide by an α-2,6 link, most commonly found in various respiratory cells,[8][17][33] such as respiratory and retinal epithelial cells.[30] AIVs prefer sialic acids with an α-2,3 linkage, which are most common in birds in gastrointestinal epithelial cells[8][17][33] and in humans in the lower respiratory tract.[43] Cleavage of the HA protein into HA1, the binding subunit, and HA2, the fusion subunit, is performed by different proteases, affecting which cells can be infected. For mammalian influenza viruses and low pathogenic AIVs, cleavage is extracellular, which limits infection to cells that have the appropriate proteases, whereas for highly pathogenic AIVs, cleavage is intracellular and performed by ubiquitous proteases, which allows for infection of a greater variety of cells, thereby contributing to more severe disease.[8][35][44]

Immunology

[edit]Cells possess sensors to detect viral RNA, which can then induce interferon production. Interferons mediate expression of antiviral proteins and proteins that recruit immune cells to the infection site, and they notify nearby uninfected cells of infection. Some infected cells release pro-inflammatory cytokines that recruit immune cells to the site of infection. Immune cells control viral infection by killing infected cells and phagocytizing viral particles and apoptotic cells. An exacerbated immune response can harm the host organism through a cytokine storm.[8][11][30] To counter the immune response, influenza viruses encode various non-structural proteins, including NS1, NEP, PB1-F2, and PA-X, that are involved in curtailing the host immune response by suppressing interferon production and host gene expression.[8][31]

B cells, a type of white blood cell, produce antibodies that bind to influenza antigens HA and NA (or HEF[25]) and other proteins to a lesser degree. Once bound to these proteins, antibodies block virions from binding to cellular receptors, neutralizing the virus. In humans, a sizeable antibody response occurs about one week after viral exposure.[45] This antibody response is typically robust and long-lasting, especially for influenza C virus and influenza D virus.[8][25] People exposed to a certain strain in childhood still possess antibodies to that strain at a reasonable level later in life, which can provide some protection to related strains.[8] There is, however, an "original antigenic sin", in which the first HA subtype a person is exposed to influences the antibody-based immune response to future infections and vaccines.[23]

Prevention

[edit]Vaccination

[edit]

Annual vaccination is the primary and most effective way to prevent influenza and influenza-associated complications, especially for high-risk groups.[7][8][46] Vaccines against the flu are trivalent or quadrivalent, providing protection against an H1N1 strain, an H3N2 strain, and one or two influenza B virus strains corresponding to the two influenza B virus lineages.[7][23] Two types of vaccines are in use: inactivated vaccines that contain "killed" (i.e. inactivated) viruses and live attenuated influenza vaccines (LAIVs) that contain weakened viruses.[8] There are three types of inactivated vaccines: whole virus, split virus, in which the virus is disrupted by a detergent, and subunit, which only contains the viral antigens HA and NA.[47] Most flu vaccines are inactivated and administered via intramuscular injection. LAIVs are sprayed into the nasal cavity.[8]

Vaccination recommendations vary by country. Some recommend vaccination for all people above a certain age, such as 6 months,[46] whereas other countries limit recommendations to high-risk groups.[8][9] Young infants cannot receive flu vaccines for safety reasons, but they can inherit passive immunity from their mother if vaccinated during pregnancy.[48] Influenza vaccination helps to reduce the probability of reassortment.[11]

In general, influenza vaccines are only effective if there is an antigenic match between vaccine strains and circulating strains.[7][23] Most commercially available flu vaccines are manufactured by propagation of influenza viruses in embryonated chicken eggs, taking 6–8 months.[23] Flu seasons are different in the northern and southern hemisphere, so the WHO meets twice a year, once for each hemisphere, to discuss which strains should be included based on observation from HA inhibition assays.[7][33] Other manufacturing methods include an MDCK cell culture-based inactivated vaccine and a recombinant subunit vaccine manufactured from baculovirus overexpression in insect cells.[23][49]

Antiviral chemoprophylaxis

[edit]Influenza can be prevented or reduced in severity by post-exposure prophylaxis with the antiviral drugs oseltamivir, which can be taken orally by those at least three months old, and zanamivir, which can be inhaled by those above seven years. Chemoprophylaxis is most useful for individuals at high risk for complications and those who cannot receive the flu vaccine.[7] Post-exposure chemoprophylaxis is only recommended if oseltamivir is taken within 48 hours of contact with a confirmed or suspected case and zanamivir within 36 hours.[7][9] It is recommended for people who have yet to receive a vaccine for the current flu season, who have been vaccinated less than two week since contact, if there is a significant mismatch between vaccine and circulating strains, or during an outbreak in a closed setting regardless of vaccination history.[9]

Infection control

[edit]These are the main ways that influenza spreads

- by direct transmission (when an infected person sneezes mucus directly into the eyes, nose or mouth of another person);

- the airborne route (when someone inhales the aerosols produced by an infected person coughing, sneezing or spitting);

- through hand-to-eye, hand-to-nose, or hand-to-mouth transmission, either from contaminated surfaces or from direct personal contact such as a hand-shake.

When vaccines and antiviral medications are limited, non-pharmaceutical interventions are essential to reduce transmission and spread. The lack of controlled studies and rigorous evidence of the effectiveness of some measures has hampered planning decisions and recommendations. Nevertheless, strategies endorsed by experts for all phases of flu outbreaks include hand and respiratory hygiene, self-isolation by symptomatic individuals and the use of face masks by them and their caregivers, surface disinfection, rapid testing and diagnosis, and contact tracing. In some cases, other forms of social distancing including school closures and travel restrictions are recommended.[50]

Reasonably effective ways to reduce the transmission of influenza include good personal health and hygiene habits such as: not touching the eyes, nose or mouth;[51] frequent hand washing (with soap and water, or with alcohol-based hand rubs);[52] covering coughs and sneezes with a tissue or sleeve; avoiding close contact with sick people; and staying home when sick. Avoiding spitting is also recommended.[50] Although face masks might help prevent transmission when caring for the sick,[53][54] there is mixed evidence on beneficial effects in the community.[50][55] Smoking raises the risk of contracting influenza, as well as producing more severe disease symptoms.[56][57]

Since influenza spreads through both aerosols and contact with contaminated surfaces, surface sanitizing may help prevent some infections.[58] Alcohol is an effective sanitizer against influenza viruses, while quaternary ammonium compounds can be used with alcohol so that the sanitizing effect lasts for longer.[59] In hospitals, quaternary ammonium compounds and bleach are used to sanitize rooms or equipment that have been occupied by people with influenza symptoms.[59] At home, this can be done effectively with a diluted chlorine bleach.[60]

Since influenza viruses circulate in animals such as birds and pigs, prevention of transmission from these animals is important. Water treatment, indoor raising of animals, quarantining sick animals, vaccination, and biosecurity are the primary measures used. Placing poultry houses and piggeries on high ground away from high-density farms, backyard farms, live poultry markets, and bodies of water helps to minimize contact with wild birds.[8] Closure of live poultry markets appears to the most effective measure[17] and has shown to be effective at controlling the spread of H5N1, H7N9, and H9N2.[18] Other biosecurity measures include cleaning and disinfecting facilities and vehicles, banning visits to poultry farms, not bringing birds intended for slaughter back to farms,[61] changing clothes, disinfecting foot baths, and treating food and water.[8]

If live poultry markets are not closed, then "clean days" when unsold poultry is removed and facilities are disinfected and "no carry-over" policies to eliminate infectious material before new poultry arrive can be used to reduce the spread of influenza viruses. If a novel influenza viruses has breached the aforementioned biosecurity measures, then rapid detection to stamp it out via quarantining, decontamination, and culling may be necessary to prevent the virus from becoming endemic.[8] Vaccines exist for avian H5, H7, and H9 subtypes that are used in some countries.[17] In China, for example, vaccination of domestic birds against H7N9 successfully limited its spread, indicating that vaccination may be an effective strategy[35] if used in combination with other measures to limit transmission.[8] In pigs and horses, management of influenza is dependent on vaccination with biosecurity.[8]

Diagnosis

[edit]

Diagnosis based on symptoms is fairly accurate in otherwise healthy people during seasonal epidemics and should be suspected in cases of pneumonia, acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS), sepsis, or if encephalitis, myocarditis, or breakdown of muscle tissue occur.[15] Because influenza is similar to other viral respiratory tract illnesses, laboratory diagnosis is necessary for confirmation. Common sample collection methods for testing include nasal and throat swabs.[8] Samples may be taken from the lower respiratory tract if infection has cleared the upper but not lower respiratory tract. Influenza testing is recommended for anyone hospitalized with symptoms resembling influenza during flu season or who is connected to an influenza case. For severe cases, earlier diagnosis improves patient outcome.[46] Diagnostic methods that can identify influenza include viral cultures, antibody- and antigen-detecting tests, and nucleic acid-based tests.[62]

Viruses can be grown in a culture of mammalian cells or embryonated eggs for 3–10 days to monitor cytopathic effect. Final confirmation can then be done via antibody staining, hemadsorption using red blood cells, or immunofluorescence microscopy. Shell vial cultures, which can identify infection via immunostaining before a cytopathic effect appears, are more sensitive than traditional cultures with results in 1–3 days.[8][46][62] Cultures can be used to characterize novel viruses, observe sensitivity to antiviral drugs, and monitor antigenic drift, but they are relatively slow and require specialized skills and equipment.[8]

Serological assays can be used to detect an antibody response to influenza after natural infection or vaccination. Common serological assays include hemagglutination inhibition assays that detect HA-specific antibodies, virus neutralization assays that check whether antibodies have neutralized the virus, and enzyme-linked immunoabsorbant assays. These methods tend to be relatively inexpensive and fast but are less reliable than nucleic-acid based tests.[8][62]

Direct fluorescent or immunofluorescent antibody (DFA/IFA) tests involve staining respiratory epithelial cells in samples with fluorescently-labeled influenza-specific antibodies, followed by examination under a fluorescent microscope. They can differentiate between influenza A virus and influenza B virus but can not subtype influenza A virus.[62] Rapid influenza diagnostic tests (RIDTs) are a simple way of obtaining assay results, are low cost, and produce results in less than 30 minutes, so they are commonly used, but they can not distinguish between influenza A virus and influenza B virus or between influenza A virus subtypes and are not as sensitive as nucleic-acid based tests.[8][62]

Nucleic acid-based tests (NATs) amplify and detect viral nucleic acid. Most of these tests take a few hours,[62] but rapid molecular assays are as fast as RIDTs.[46] Among NATs, reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) is the most traditional and considered the gold standard for diagnosing influenza[62] because it is fast and can subtype influenza A virus, but it is relatively expensive and more prone to false-positives than cultures.[8] Other NATs that have been used include loop-mediated isothermal amplification-based assays, simple amplification-based assays, and nucleic acid sequence-based amplification. Nucleic acid sequencing methods can identify infection by obtaining the nucleic acid sequence of viral samples to identify the virus and antiviral drug resistance. The traditional method is Sanger sequencing, but it has been largely replaced by next-generation methods that have greater sequencing speed and throughput.[62]

Management

[edit]Treatment in cases of mild or moderate illness is supportive and includes anti-fever medications such as acetaminophen and ibuprofen,[63] adequate fluid intake to avoid dehydration, and rest.[9] Cough drops and throat sprays may be beneficial for sore throat. It is recommended to avoid alcohol and tobacco use while ill.[63] Aspirin is not recommended to treat influenza in children due to an elevated risk of developing Reye syndrome.[64] Corticosteroids are not recommended except when treating septic shock or an underlying medical condition, such as chronic obstructive pulmonary disease or asthma exacerbation, since they are associated with increased mortality.[46][65] If a secondary bacterial infection occurs, then antibiotics may be necessary.[9]

Antivirals

[edit]| Drug | Route of administration | Approved age of use |

|---|---|---|

| Oseltamivir | Oral | At least two weeks old |

| Zanamivir | Inhalation | At least five years old |

| Peramivir | Intravenous injection | At least 18 years old |

| Laninamivir | Inhalation[8] | 40 milligrams (mg) dose for people at least 10 years old, 20 mg for those under 10[66] |

| Baloxavir marboxil | Oral[38] | At least 12 years old[46] |

Antiviral drugs are primarily used to treat severely ill patients, especially those with compromised immune systems. Antivirals are most effective when started in the first 48 hours after symptoms appear. Later administration may still be beneficial for those who have underlying immune defects, those with more severe symptoms, or those who have a higher risk of developing complications if these individuals are still shedding the virus. Antiviral treatment is also recommended if a person is hospitalized with suspected influenza instead of waiting for test results to return and if symptoms are worsening.[8][46] Most antiviral drugs against influenza fall into two categories: neuraminidase (NA) inhibitors and M2 inhibitors.[11] Baloxavir marboxil is a notable exception, which targets the endonuclease activity of the viral RNA polymerase and can be used as an alternative to NA and M2 inhibitors for influenza A virus and influenza B virus.[7][17][38]

NA inhibitors target the enzymatic activity of NA receptors, mimicking the binding of sialic acid in the active site of NA on influenza A virus and influenza B virus virions[8] so that viral release from infected cells and the rate of viral replication are impaired.[9] NA inhibitors include oseltamivir, which is consumed orally in a prodrug form and converted to its active form in the liver, and zanamivir, which is a powder that is inhaled nasally. Oseltamivir and zanamivir are effective for prophylaxis and post-exposure prophylaxis, and research overall indicates that NA inhibitors are effective at reducing rates of complications, hospitalization, and mortality[8] and the duration of illness.[11][46][38] Additionally, the earlier NA inhibitors are provided, the better the outcome,[38] though late administration can still be beneficial in severe cases.[8][46] Other NA inhibitors include laninamivir[8] and peramivir, the latter of which can be used as an alternative to oseltamivir for people who cannot tolerate or absorb it.[46]

The adamantanes amantadine and rimantadine are orally administered drugs that block the influenza virus' M2 ion channel,[8] preventing viral uncoating.[38] These drugs are only functional against influenza A virus[46] but are no longer recommended for use because of widespread resistance to them among influenza A viruses.[38] Adamantane resistance first emerged in H3N2 in 2003, becoming worldwide by 2008. Oseltamivir resistance is no longer widespread because the 2009 pandemic H1N1 strain (H1N1 pdm09), which is resistant to adamantanes, seemingly replaced resistant strains in circulation. Since the 2009 pandemic, oseltamivir resistance has mainly been observed in patients undergoing therapy,[8] especially the immunocompromised and young children.[38] Oseltamivir resistance is usually reported in H1N1, but has been reported in H3N2 and influenza B viruss less commonly.[8] Because of this, oseltamivir is recommended as the first drug of choice for immunocompetent people, whereas for the immunocompromised, oseltamivir is recommended against H3N2 and influenza B virus and zanamivir against H1N1 pdm09. Zanamivir resistance is observed less frequently, and resistance to peramivir and baloxavir marboxil is possible.[38]

Prognosis

[edit]In healthy individuals, influenza infection is usually self-limiting and rarely fatal.[7][9] Symptoms usually last for 2–8 days.[11] Influenza can cause people to miss work or school, and it is associated with decreased job performance and, in older adults, reduced independence. Fatigue and malaise may last for several weeks after recovery, and healthy adults may experience pulmonary abnormalities that can take several weeks to resolve. Complications and mortality primarily occur in high-risk populations and those who are hospitalized. Severe disease and mortality are usually attributable to pneumonia from the primary viral infection or a secondary bacterial infection,[8][9] which can progress to ARDS.[11]

Other respiratory complications that may occur include sinusitis, bronchitis, bronchiolitis, excess fluid buildup in the lungs, and exacerbation of chronic bronchitis and asthma. Middle ear infection and croup may occur, most commonly in children.[7][8] Secondary S. aureus infection has been observed, primarily in children, to cause toxic shock syndrome after influenza, with hypotension, fever, and reddening and peeling of the skin.[8] Complications affecting the cardiovascular system are rare and include pericarditis, fulminant myocarditis with a fast, slow, or irregular heartbeat, and exacerbation of pre-existing cardiovascular disease.[7][9] Inflammation or swelling of muscles accompanied by muscle tissue breaking down occurs rarely, usually in children, which presents as extreme tenderness and muscle pain in the legs and a reluctance to walk for 2–3 days.[8][9][15]

Influenza can affect pregnancy, including causing smaller neonatal size, increased risk of premature birth, and an increased risk of child death shortly before or after birth.[9] Neurological complications have been associated with influenza on rare occasions, including aseptic meningitis, encephalitis, disseminated encephalomyelitis, transverse myelitis, and Guillain–Barré syndrome.[15] Additionally, febrile seizures and Reye syndrome can occur, most commonly in children.[8][9] Influenza-associated encephalopathy can occur directly from central nervous system infection from the presence of the virus in blood and presents as sudden onset of fever with convulsions, followed by rapid progression to coma.[7] An atypical form of encephalitis called encephalitis lethargica, characterized by headache, drowsiness, and coma, may rarely occur sometime after infection.[8] In survivors of influenza-associated encephalopathy, neurological defects may occur.[7] Primarily in children, in severe cases the immune system may rarely dramatically overproduce white blood cells that release cytokines, causing severe inflammation.[7]

People who are at least 65 years of age,[9] due to a weakened immune system from aging or a chronic illness, are a high-risk group for developing complications, as are children less than one year of age and children who have not been previously exposed to influenza viruses multiple times. Pregnant women are at an elevated risk, which increases by trimester[8] and lasts up to two weeks after childbirth.[9][46] Obesity, in particular a body mass index greater than 35–40, is associated with greater amounts of viral replication, increased severity of secondary bacterial infection, and reduced vaccination efficacy. People who have underlying health conditions are also considered at-risk, including those who have congenital or chronic heart problems or lung (e.g. asthma), kidney, liver, blood, neurological, or metabolic (e.g. diabetes) disorders,[7][8][9] as are people who are immunocompromised from chemotherapy, asplenia, prolonged steroid treatment, splenic dysfunction, or HIV infection.[9] Tobacco use, including past use, places a person at risk.[46] The role of genetics in influenza is not well researched,[8] but it may be a factor in influenza mortality.[11]

Epidemiology

[edit]

Influenza is typically characterized by seasonal epidemics and sporadic pandemics. Most of the burden of influenza is a result of flu seasons caused by influenza A virus and influenza B virus. Among influenza A virus subtypes, H1N1 and H3N2 circulate in humans and are responsible for seasonal influenza. Cases disproportionately occur in children, but most severe causes are among the elderly, the very young,[8] and the immunocompromised.[38] In a typical year, influenza viruses infect 5–15% of the global population,[33][62] causing 3–5 million cases of severe illness annually[8][23] and accounting for 290,000–650,000 deaths each year due to respiratory illness.[33][38][68] 5–10% of adults and 20–30% of children contract influenza each year.[21] The reported number of influenza cases is usually much lower than the actual number.[8][48]

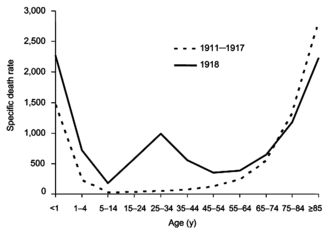

During seasonal epidemics, it is estimated that about 80% of otherwise healthy people who have a cough or sore throat have the flu.[8] Approximately 30–40% of people hospitalized for influenza develop pneumonia, and about 5% of all severe pneumonia cases in hospitals are due to influenza, which is also the most common cause of ARDS in adults. In children, influenza and respiratory syncytial virus are the two most common causes of ARDS.[15] About 3–5% of children each year develop otitis media due to influenza.[7] Adults who develop organ failure from influenza and children who have PIM scores and acute renal failure have higher rates of mortality.[15] During seasonal influenza, mortality is concentrated in the very young and the elderly, whereas during flu pandemics, young adults are often affected at a high rate.[11]

In temperate regions, the number of influenza cases varies from season to season. Lower vitamin D levels, presumably due to less sunlight,[41] lower humidity, lower temperature, and minor changes in virus proteins caused by antigenic drift contribute to annual epidemics that peak during the winter season. In the northern hemisphere, this is from October to May (more narrowly December to April[11]), and in the southern hemisphere, this is from May to October (more narrowly June to September[11]). There are therefore two distinct influenza seasons every year in temperate regions, one in the northern hemisphere and one in the southern hemisphere.[8][9][23] In tropical and subtropical regions, seasonality is more complex and appears to be affected by various climatic factors such as minimum temperature, hours of sunshine, maximum rainfall, and high humidity.[8][69] Influenza may therefore occur year-round in these regions.[11] Influenza epidemics in modern times have the tendency to start in the eastern or southern hemisphere,[69] with Asia being a key reservoir.[11]

Influenza A virus and influenza B virus co-circulate, so have the same patterns of transmission.[8] The seasonality of influenza C virus, however, is poorly understood. Influenza C virus infection is most common in children under the age of two, and by adulthood most people have been exposed to it. Influenza C virus-associated hospitalization most commonly occurs in children under the age of three and is frequently accompanied by co-infection with another virus or a bacterium, which may increase the severity of disease. When considering all hospitalizations for respiratory illness among young children, influenza C virus appears to account for only a small percentage of such cases. Large outbreaks of influenza C virus infection can occur, so incidence varies significantly.[10]

Outbreaks of influenza caused by novel influenza viruses are common.[29] Depending on the level of pre-existing immunity in the population, novel influenza viruses can spread rapidly and cause pandemics with millions of deaths. These pandemics, in contrast to seasonal influenza, are caused by antigenic shifts involving animal influenza viruses. To date, all known flu pandemics have been caused by influenza A viruses, and they follow the same pattern of spreading from an origin point to the rest of the world over the course of multiple waves in a year.[8][9][46] Pandemic strains tend to be associated with higher rates of pneumonia in otherwise healthy individuals.[15] Generally after each influenza pandemic, the pandemic strain continues to circulate as the cause of seasonal influenza, replacing prior strains.[8] From 1700 to 1889, influenza pandemics occurred about once every 50–60 years. Since then, pandemics have occurred about once every 10–50 years, so they may be getting more frequent over time.[69]

History

[edit]

The first influenza epidemic may have occurred around 6000 BC in China,[71] and possible descriptions of influenza exist in Greek writings from the 5th century BC.[69][72] In both 1173–1174 AD and 1387 AD, epidemics occurred across Europe that were named "influenza". Whether these epidemics or others were caused by influenza is unclear since there was then no consistent naming pattern for epidemic respiratory diseases, and "influenza" did not become clearly associated with respiratory disease until centuries later.[73] Influenza may have been brought to the Americas as early as 1493, when an epidemic disease resembling influenza killed most of the population of the Antilles.[74][75]

The first convincing record of an influenza pandemic was in 1510. It began in East Asia before spreading to North Africa and then Europe.[76] Following the pandemic, seasonal influenza occurred, with subsequent pandemics in 1557 and 1580.[73] The flu pandemic in 1557 was potentially the first time influenza was connected to miscarriage and death of pregnant women.[77] The 1580 influenza pandemic originated in Asia during summer, spread to Africa, then Europe, and finally America.[69] By the end of the 16th century, influenza was beginning to become understood as a specific, recognizable disease with epidemic and endemic forms.[73] In 1648, it was discovered that horses also experience influenza.[76]

Influenza data after 1700 is more accurate, so it is easier to identify flu pandemics after this point.[78] The first flu pandemic of the 18th century started in 1729 in Russia in spring, spreading worldwide over the course of three years with distinct waves, the later ones being more lethal. Another flu pandemic occurred in 1781–1782, starting in China in autumn.[69] From this pandemic, influenza became associated with sudden outbreaks of febrile illness.[78] The next flu pandemic was from 1830 to 1833, beginning in China in winter. This pandemic had a high attack rate, but the mortality rate was low.[34][69]

A minor influenza pandemic occurred from 1847 to 1851 at the same time as the third cholera pandemic and was the first flu pandemic to occur with vital statistics being recorded, so influenza mortality was clearly recorded for the first time.[78] Fowl plague (now recognised as highly pathogenic avian influenza) was recognized in 1878[78] and was soon linked to transmission to humans.[76] By the time of the 1889 pandemic, which may have been caused by an H2N2 strain,[79] the flu had become an easily recognizable disease.[76]

The microbial agent responsible for influenza was incorrectly identified in 1892 by R. F. J. Pfeiffer as the bacteria species Haemophilus influenzae, which retains "influenza" in its name.[76][78] From 1901 to 1903, Italian and Austrian researchers were able to show that avian influenza, then called "fowl plague",[35] was caused by a microscopic agent smaller than bacteria by using filters with pores too small for bacteria to pass through. The fundamental differences between viruses and bacteria, however, were not yet fully understood.[78]

From 1918 to 1920, the Spanish flu pandemic became the most devastating influenza pandemic and one of the deadliest pandemics in history. The pandemic, caused by an H1N1 strain of influenza A,[78] likely began in the United States before spreading worldwide via soldiers during and after the First World War. The initial wave in the first half of 1918 was relatively minor and resembled past flu pandemics, but the second wave later that year had a much higher mortality rate.[69] A third wave with lower mortality occurred in many places a few months after the second.[34] By the end of 1920, it is estimated that about a third[11] to half of all people in the world had been infected, with tens of millions of deaths, disproportionately young adults.[69] During the 1918 pandemic, the respiratory route of transmission was clearly identified[34] and influenza was shown to be caused by a "filter passer", not a bacterium, but there remained a lack of agreement about influenza's cause for another decade and research on influenza declined.[78] After the pandemic, H1N1 circulated in humans in seasonal form[8] until the next pandemic.[78]

In 1931, Richard Shope published three papers identifying a virus as the cause of swine influenza, a then newly recognized disease among pigs that was characterized during the second wave of the 1918 pandemic.[77][78] Shope's research reinvigorated research on human influenza, and many advances in virology, serology, immunology, experimental animal models, vaccinology, and immunotherapy have since arisen from influenza research.[78] Just two years after influenza viruses were discovered, in 1933, influenza A virus was identified as the agent responsible for human influenza.[77][81] Subtypes of influenza A virus were discovered throughout the 1930s,[78] and influenza B virus was discovered in 1940.[21]

During the Second World War, the US government worked on developing inactivated vaccines for influenza, resulting in the first influenza vaccine being licensed in 1945 in the United States.[8] Influenza C virus was discovered two years later in 1947.[21] In 1955, avian influenza was confirmed to be caused by influenza A virus.[35] Four influenza pandemics have occurred since WWII. The first of these was the Asian flu from 1957 to 1958, caused by an H2N2 strain[8][82] and beginning in China's Yunnan province. The number of deaths probably exceeded one million, mostly among the very young and very old.[69] This was the first flu pandemic to occur in the presence of a global surveillance system and laboratories able to study the novel influenza virus.[34] After the pandemic, H2N2 was the influenza A virus subtype responsible for seasonal influenza.[8] The first antiviral drug against influenza, amantadine, was approved in 1966, with additional antiviral drugs being used since the 1990s.[38]

In 1968, H3N2 was introduced into humans through a rearrangement between an avian H3N2 strain and an H2N2 strain that was circulating in humans. The novel H3N2 strain emerged in Hong Kong and spread worldwide, causing the Hong Kong flu pandemic, which resulted in 500,000–2,000,000 deaths. This was the first pandemic to spread significantly by air travel.[33][34] H2N2 and H3N2 co-circulated after the pandemic until 1971 when H2N2 waned in prevalence and was completely replaced by H3N2.[33] In 1977, H1N1 reemerged in humans, possibly after it was released from a freezer in a laboratory accident, and caused a pseudo-pandemic.[34][78] This H1N1 strain was antigenically similar to the H1N1 strains that circulated prior to 1957. Since 1977, both H1N1 and H3N2 have circulated in humans as part of seasonal influenza.[8] In 1980, the classification system used to subtype influenza viruses was introduced.[83]

At some point, influenza B virus diverged into two strains, named the B/Victoria-like and B/Yamagata-like lineages, both of which have been circulating in humans since 1983.[21]

In 1996, a highly pathogenic H5N1 subtype of influenza A was detected in geese in Guangdong, China[35] and a year later emerged in poultry in Hong Kong, gradually spreading worldwide from there. A small H5N1 outbreak in humans in Hong Kong occurred then,[44] and sporadic human cases have occurred since 1997, carrying a high case fatality rate.[17][62]

The most recent flu pandemic was the 2009 swine flu pandemic, which originated in Mexico and resulted in hundreds of thousands of deaths.[34] It was caused by a novel H1N1 strain that was a reassortment of human, swine, and avian influenza viruses.[18][38] The 2009 pandemic had the effect of replacing prior H1N1 strains in circulation with the novel strain but not any other influenza viruses. Consequently, H1N1, H3N2, and both influenza B virus lineages have been in circulation in seasonal form since the 2009 pandemic.[8][34][35]

In 2011, influenza D virus was discovered in pigs in Oklahoma, USA, and cattle were later identified as the primary reservoir of influenza D virus.[10][21]

In the same year,[62] avian H7N9 was detected in China and began to cause human infections in 2013, starting in Shanghai and Anhui and remaining mostly in China. Highly pathogenic H7N9 emerged sometime in 2016 and has occasionally infected humans incidentally. Other avian influenza viruses have less commonly infected humans since the 1990s, including H5N1, H5N5, H5N6, H5N8, H6N1, H7N2, H7N7, and H10N7, and have begun to spread throughout much of the world since the 2010s.[17] Future flu pandemics, which may be caused by an influenza virus of avian origin,[35] are viewed as almost inevitable, and increased globalization has made it easier for a pandemic virus to spread,[34] so there are continual efforts to prepare for future pandemics[77] and improve the prevention and treatment of influenza.[8]

Etymology

[edit]The word influenza comes from the Italian word influenza, from medieval Latin influentia, originally meaning 'visitation' or 'influence'. Terms such as influenza di freddo, meaning 'influence of the cold', and influenza di stelle, meaning 'influence of the stars' are attested from the 14th century. The latter referred to the disease's cause, which at the time was ascribed by some to unfavorable astrological conditions. As early as 1504, influenza began to mean a 'visitation' or 'outbreak' of any disease affecting many people in a single place at once. During an outbreak of influenza in 1743 that started in Italy and spread throughout Europe, the word reached the English language and was anglicized in pronunciation. Since the mid-1800s, influenza has also been used to refer to severe colds.[84][85][86] The shortened form of the word, "flu", is first attested in 1839 as flue with the spelling flu confirmed in 1893.[87] Other names that have been used for influenza include epidemic catarrh, la grippe from French, sweating sickness, and, especially when referring to the 1918 pandemic strain, Spanish fever.[88]

In animals

[edit]Birds

[edit]Aquatic birds such as ducks, geese, shorebirds, and gulls are the primary reservoir of influenza A viruses (IAVs).[17][18]

Because of the impact of avian influenza on economically important chicken farms, a classification system was devised in 1981 which divided avian virus strains as either highly pathogenic (and therefore potentially requiring vigorous control measures) or low pathogenic. The test for this is based solely on the effect on chickens – a virus strain is highly pathogenic avian influenza (HPAI) if 75% or more of chickens die after being deliberately infected with it. The alternative classification is low pathogenic avian influenza (LPAI) which produces mild or no symptoms.[89] This classification system has since been modified to take into account the structure of the virus' haemagglutinin protein.[90] At the genetic level, an AIV can be identified as an HPAI virus if it has a multibasic cleavage site in the HA protein, which contains additional residues in the HA gene.[18][35] Other species of birds, especially water birds, can become infected with HPAI virus without experiencing severe symptoms and can spread the infection over large distances; the exact symptoms depend on the species of bird and the strain of virus.[89] Classification of an avian virus strain as HPAI or LPAI does not predict how serious the disease might be if it infects humans or other mammals.[89][91]

Symptoms of HPAI infection in chickens include lack of energy and appetite, decreased egg production, soft-shelled or misshapen eggs, swelling of the head, comb, wattles, and hocks, purple discoloration of wattles, combs, and legs, nasal discharge, coughing, sneezing, incoordination, and diarrhea; birds infected with an HPAI virus may also die suddenly without any signs of infection.[61] Notable HPAI viruses include influenza A (H5N1) and A (H7N9). HPAI viruses have been a major disease burden in the 21st century, resulting in the death of large numbers of birds. In H7N9's case, some circulating strains were originally low pathogenic but became high pathogenic by mutating to acquire the HA multibasic cleavage site. Avian H9N2 is also of concern because although it is low pathogenic, it is a common donor of genes to H5N1 and H7N9 during reassortment.[8]

Migratory birds can spread influenza across long distances. An example of this was when an H5N1 strain in 2005 infected birds at Qinghai Lake, China, which is a stopover and breeding site for many migratory birds, subsequently spreading the virus to more than 20 countries across Asia, Europe, and the Middle East.[17][35] AIVs can be transmitted from wild birds to domestic free-range ducks and in turn to poultry through contaminated water, aerosols, and fomites.[8] Ducks therefore act as key intermediates between wild and domestic birds.[35] Transmission to poultry typically occurs in backyard farming and live animal markets where multiple species interact with each other. From there, AIVs can spread to poultry farms in the absence of adequate biosecurity. Among poultry, HPAI transmission occurs through aerosols and contaminated feces,[8] cages, feed, and dead animals.[17] Back-transmission of HPAI viruses from poultry to wild birds has occurred and is implicated in mass die-offs and intercontinental spread.[18]

AIVs have occasionally infected humans through aerosols, fomites, and contaminated water.[8] Direction transmission from wild birds is rare.[35] Instead, most transmission involves domestic poultry, mainly chickens, ducks, and geese but also a variety of other birds such as guinea fowl, partridge, pheasants, and quails.[18] The primary risk factor for infection with AIVs is exposure to birds in farms and live poultry markets.[17] Typically, infection with an AIV has an incubation period of 3–5 days but can be up to 9 days. H5N1 and H7N9 cause severe lower respiratory tract illness, whereas other AIVs such as H9N2 cause a more mild upper respiratory tract illness, commonly with conjunctivitis.[8] Limited transmission of avian H2, H5-7, H9, and H10 subtypes from one person to another through respiratory droplets, aerosols, and fomites has occurred, but sustained human-to-human transmission of AIVs has not occurred.[8][23]

Pigs

[edit]

Influenza in pigs is a respiratory disease similar to influenza in humans and is found worldwide. Asymptomatic infections are common. Symptoms typically appear 1–3 days after infection and include fever, lethargy, anorexia, weight loss, labored breathing, coughing, sneezing, and nasal discharge. In sows, pregnancy may be aborted. Complications include secondary infections and potentially fatal bronchopneumonia. Pigs become contagious within a day of infection and typically spread the virus for 7–10 days, which can spread rapidly within a herd. Pigs usually recover within 3–7 days after symptoms appear. Prevention and control measures include inactivated vaccines and culling infected herds. Influenza A virus subtypes H1N1, H1N2, and H3N2 are usually responsible for swine flu.[92]

Some influenza A viruses can be transmitted via aerosols from pigs to humans and vice versa.[8] Pigs, along with bats and quails,[21] are recognized as a mixing vessel of influenza viruses because they have both α-2,3 and α-2,6 sialic acid receptors in their respiratory tract. Because of that, both avian and mammalian influenza viruses can infect pigs. If co-infection occurs, reassortment is possible.[18] A notable example of this was the reassortment of a swine, avian, and human influenza virus that caused the 2009 flu pandemic.[18][38] Spillover events from humans to pigs appear to be more common than from pigs to humans.[18]

Other animals

[edit]Influenza viruses have been found in many other animals, including cattle, horses, dogs, cats, and marine mammals. Nearly all influenza A viruses are apparently descended from ancestral viruses in birds. The exception are bat influenza-like viruses, which have an uncertain origin. These bat viruses have HA and NA subtypes H17, H18, N10, and N11. H17N10 and H18N11 are unable to reassort with other influenza A viruses, but they are still able to replicate in other mammals.[8]

Equine influenza A viruses include H7N7 and two lineages[8] of H3N8. H7N7, however, has not been detected in horses since the late 1970s,[29] so it may have become extinct in horses.[18] H3N8 in equines spreads via aerosols and causes respiratory illness.[8] Equine H3N8 preferentially binds to α-2,3 sialic acids, so horses are usually considered dead-end hosts, but transmission to dogs and camels has occurred, raising concerns that horses may be mixing vessels for reassortment. In canines, the only influenza A viruses in circulation are equine-derived H3N8 and avian-derived H3N2. Canine H3N8 has not been observed to reassort with other subtypes. H3N2 has a much broader host range and can reassort with H1N1 and H5N1. An isolated case of H6N1, likely from a chicken, was found infecting a dog, so other AIVs may emerge in canines.[18]

A wide range of other mammals have been affected by avian influenza A viruses, generally due to eating birds which had been infected.[93] There have been instances where transmission of the disease between mammals, including seals and cows, may have occurred.[94][95][29] Various mutations have been identified that are associated with AIVs adapting to mammals. Since HA proteins vary in which sialic acids they bind to, mutations in the HA receptor binding site can allow AIVs to infect mammals. Other mutations include mutations affecting which sialic acids NA proteins cleave and a mutation in the PB2 polymerase subunit that improves tolerance of lower temperatures in mammalian respiratory tracts and enhances RNP assembly by stabilizing NP and PB2 binding.[18]

Influenza B virus is mainly found in humans but has also been detected in pigs, dogs, horses, and seals.[21] Likewise, influenza C virus primarily infects humans but has been observed in pigs, dogs, cattle, and dromedary camels.[10][21] Influenza D virus causes an influenza-like illness in pigs but its impact in its natural reservoir, cattle, is relatively unknown. It may cause respiratory disease resembling human influenza on its own, or it may be part of a bovine respiratory disease (BRD) complex with other pathogens during co-infection. BRD is a concern for the cattle industry, so influenza D virus' possible involvement in BRD has led to research on vaccines for cattle that can provide protection against influenza D virus.[21][25] Two antigenic lineages are in circulation: D/swine/Oklahoma/1334/2011 (D/OK) and D/bovine/Oklahoma/660/2013 (D/660).[21]

References

[edit]- ^ a b "Influenza (seasonal)". World Health Organization. 28 February 2025. Retrieved 28 June 2025.

- ^ "Flu Symptoms & Diagnosis". U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). 10 July 2019. Archived from the original on 27 December 2019. Retrieved 24 January 2020.

- ^ "Flu Symptoms & Complications". U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). 26 February 2019. Archived from the original on 1 August 2020. Retrieved 6 July 2019.

- ^ Call SA, Vollenweider MA, Hornung CA, Simel DL, McKinney WP (February 2005). "Does this patient have influenza?". JAMA. 293 (8): 987–997. doi:10.1001/jama.293.8.987. PMID 15728170.

- ^ Allan GM, Arroll B (February 2014). "Prevention and treatment of the common cold: making sense of the evidence". CMAJ. 186 (3): 190–199. doi:10.1503/cmaj.121442. PMC 3928210. PMID 24468694.

- ^ "Cold Versus Flu". 11 August 2016. Archived from the original on 6 January 2017. Retrieved 5 January 2017.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v Dharmapalan D (October 2020). "Influenza". Indian Journal of Pediatrics. 87 (10): 828–832. doi:10.1007/s12098-020-03214-1. PMC 7091034. PMID 32048225.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z aa ab ac ad ae af ag ah ai aj ak al am an ao ap aq ar as at au av aw ax ay az ba bb bc bd be bf bg bh bi bj bk bl bm bn bo bp bq br bs bt bu bv bw bx by bz ca cb cc cd ce cf cg ch ci cj Krammer F, Smith GJ, Fouchier RA, Peiris M, Kedzierska K, Doherty PC, et al. (June 2018). "Influenza". Nature Reviews. Disease Primers. 4 (1) 3. doi:10.1038/s41572-018-0002-y. PMC 7097467. PMID 29955068.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z aa ab Ghebrehewet S, MacPherson P, Ho A (December 2016). "Influenza". BMJ. 355 i6258. doi:10.1136/bmj.i6258. PMC 5141587. PMID 27927672.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Sederdahl BK, Williams JV (January 2020). "Epidemiology and Clinical Characteristics of Influenza C Virus". Viruses. 12 (1): 89. doi:10.3390/v12010089. PMC 7019359. PMID 31941041.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q Peteranderl C, Herold S, Schmoldt C (August 2016). "Human Influenza Virus Infections". Seminars in Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine. 37 (4): 487–500. doi:10.1055/s-0036-1584801. PMC 7174870. PMID 27486731.

- ^ Triggle N (28 September 2021). "People also suffer 'long flu', study shows". BBC News Online. Archived from the original on 25 March 2022. Retrieved 10 June 2024.

- ^ Sauerwein K (14 December 2023). "'Long flu' has emerged as a consequence similar to long COVID". Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis (Press release). Archived from the original on 10 June 2024. Retrieved 10 June 2024.

- ^ Xie Y, Choi T, Al-Aly Z (March 2024). "Long-term outcomes following hospital admission for COVID-19 versus seasonal influenza: a cohort study". The Lancet. Infectious Diseases. 24 (3): 239–255. doi:10.1016/S1473-3099(23)00684-9. PMID 38104583.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Kalil AC, Thomas PG (July 2019). "Influenza virus-related critical illness: pathophysiology and epidemiology". Critical Care. 23 (1) 258. doi:10.1186/s13054-019-2539-x. PMC 6642581. PMID 31324202.

- ^ "Virus Taxonomy: 2019 Release". International Committee on Taxonomy of Viruses. Archived from the original on 20 March 2020. Retrieved 9 March 2021.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o Li YT, Linster M, Mendenhall IH, Su YC, Smith GJ (December 2019). "Avian influenza viruses in humans: lessons from past outbreaks". British Medical Bulletin. 132 (1): 81–95. doi:10.1093/bmb/ldz036. PMC 6992886. PMID 31848585.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n Joseph U, Su YC, Vijaykrishna D, Smith GJ (January 2017). "The ecology and adaptive evolution of influenza A interspecies transmission". Influenza and Other Respiratory Viruses. 11 (1): 74–84. doi:10.1111/irv.12412. PMC 5155642. PMID 27426214.

- ^ CDC (1 February 2024). "Influenza Type A Viruses". Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Retrieved 3 May 2024.

- ^ "FluGlobalNet – Avian Influenza". science.vla.gov.uk. Retrieved 5 June 2024.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s Asha K, Kumar B (February 2019). "Emerging Influenza D Virus Threat: What We Know so Far!". Journal of Clinical Medicine. 8 (2): 192. doi:10.3390/jcm8020192. PMC 6406440. PMID 30764577.

- ^ "Influenza A Subtypes and the Species Affected | Seasonal Influenza (Flu) | CDC". Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 17 June 2024. Retrieved 18 June 2024.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l Sautto GA, Kirchenbaum GA, Ross TM (January 2018). "Towards a universal influenza vaccine: different approaches for one goal". Virology Journal. 15 (1) 17. doi:10.1186/s12985-017-0918-y. PMC 5785881. PMID 29370862.

- ^ Koutsakos M, Wheatley AK, Laurie K, Kent SJ, Rockman S (December 2021). "Influenza lineage extinction during the COVID-19 pandemic?". Nature Reviews. Microbiology. 19 (12): 741–742. doi:10.1038/s41579-021-00642-4. PMC 8477979. PMID 34584246.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Su S, Fu X, Li G, Kerlin F, Veit M (November 2017). "Novel Influenza D virus: Epidemiology, pathology, evolution and biological characteristics". Virulence. 8 (8): 1580–1591. doi:10.1080/21505594.2017.1365216. PMC 5810478. PMID 28812422.

- ^ a b "70 years of GISRS – the Global Influenza Surveillance & Response System". World Health Organization. 19 September 2022. Retrieved 13 June 2024.

- ^ "A revision of the system of nomenclature for influenza viruses: a WHO Memorandum". Bull World Health Organ. 58 (4): 585–591. 1980. PMC 2395936. PMID 6969132.

This Memorandum was drafted by the signatories listed on page 590 on the occasion of a meeting held in Geneva in February 1980.

- ^ a b Technical note: Influenza virus nomenclature. Pan American Health Organization (Report). 22 November 2022. Archived from the original on 10 August 2023. Retrieved 27 May 2024.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i McCauley JW, Hongo S, Kaverin NV, Kochs G, Lamb RA, Matrosovich MN, et al. (2011). "Orthomyxoviridae". International Committee on Taxonomy of Viruses. Archived from the original on 8 August 2022. Retrieved 9 March 2021.

- ^ a b c d e f g Shim JM, Kim J, Tenson T, Min JY, Kainov DE (August 2017). "Influenza Virus Infection, Interferon Response, Viral Counter-Response, and Apoptosis". Viruses. 9 (8): 223. doi:10.3390/v9080223. PMC 5580480. PMID 28805681.

- ^ a b c d e Hao W, Wang L, Li S (October 2020). "Roles of the Non-Structural Proteins of Influenza A Virus". Pathogens. 9 (10): 812. doi:10.3390/pathogens9100812. PMC 7600879. PMID 33023047.

- ^ Dadonaite B, Vijayakrishnan S, Fodor E, Bhella D, Hutchinson EC (August 2016). "Filamentous influenza viruses". The Journal of General Virology. 97 (8): 1755–1764. doi:10.1099/jgv.0.000535. PMC 5935222. PMID 27365089.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o Allen JD, Ross TM (2018). "H3N2 influenza viruses in humans: Viral mechanisms, evolution, and evaluation". Human Vaccines & Immunotherapeutics. 14 (8): 1840–1847. doi:10.1080/21645515.2018.1462639. PMC 6149781. PMID 29641358.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Saunders-Hastings PR, Krewski D (December 2016). "Reviewing the History of Pandemic Influenza: Understanding Patterns of Emergence and Transmission". Pathogens. 5 (4): 66. doi:10.3390/pathogens5040066. PMC 5198166. PMID 27929449.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l Lycett SJ, Duchatel F, Digard P (June 2019). "A brief history of bird flu". Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London. Series B, Biological Sciences. 374 (1775) 20180257. doi:10.1098/rstb.2018.0257. PMC 6553608. PMID 31056053.

- ^ Broor S, Campbell H, Hirve S, Hague S, Jackson S, Moen A, et al. (November 2020). "Leveraging the Global Influenza Surveillance and Response System for global respiratory syncytial virus surveillance-opportunities and challenges". Influenza and Other Respiratory Viruses. 14 (6): 622–629. doi:10.1111/irv.12672. PMC 7578328. PMID 31444997.

This article incorporates text available under the CC BY 4.0 license.

This article incorporates text available under the CC BY 4.0 license.

- ^ a b c d Kutter JS, Spronken MI, Fraaij PL, Fouchier RA, Herfst S (February 2018). "Transmission routes of respiratory viruses among humans". Current Opinion in Virology. 28: 142–151. doi:10.1016/j.coviro.2018.01.001. PMC 7102683. PMID 29452994.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o Lampejo T (July 2020). "Influenza and antiviral resistance: an overview". European Journal of Clinical Microbiology & Infectious Diseases. 39 (7): 1201–1208. doi:10.1007/s10096-020-03840-9. PMC 7223162. PMID 32056049.

- ^ a b c Killingley B, Nguyen-Van-Tam J (September 2013). "Routes of influenza transmission". Influenza and Other Respiratory Viruses. 7 (Suppl 2): 42–51. doi:10.1111/irv.12080. PMC 5909391. PMID 24034483.

- ^ Weber TP, Stilianakis NI (November 2008). "Inactivation of influenza A viruses in the environment and modes of transmission: a critical review". The Journal of Infection. 57 (5): 361–373. doi:10.1016/j.jinf.2008.08.013. PMC 7112701. PMID 18848358.

- ^ a b Moriyama M, Hugentobler WJ, Iwasaki A (September 2020). "Seasonality of Respiratory Viral Infections" (PDF). Annual Review of Virology. 7 (1): 83–101. doi:10.1146/annurev-virology-012420-022445. PMID 32196426.

- ^ Yoo E (February 2014). "Conformation and Linkage Studies of Specific Oligosaccharides Related to H1N1, H5N1, and Human Flu for Developing the Second Tamiflu". Biomolecules & Therapeutics. 22 (2): 93–99. doi:10.4062/biomolther.2014.005. PMC 3975476. PMID 24753813.

- ^ Shao W, Li X, Goraya MU, Wang S, Chen JL (August 2017). "Evolution of Influenza A Virus by Mutation and Re-Assortment". International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 18 (8): 1650. doi:10.3390/ijms18081650. PMC 5578040. PMID 28783091.

- ^ a b Steinhauer DA (May 1999). "Role of hemagglutinin cleavage for the pathogenicity of influenza virus". Virology. 258 (1): 1–20. doi:10.1006/viro.1999.9716. PMID 10329563.

- ^ Einav T, Gentles LE, Bloom JD (July 2020). "SnapShot: Influenza by the Numbers". Cell. 182 (2): 532–532.e1. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2020.05.004. PMID 32707094. S2CID 220715148.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o Chow EJ, Doyle JD, Uyeki TM (June 2019). "Influenza virus-related critical illness: prevention, diagnosis, treatment". Critical Care. 23 (1) 214. doi:10.1186/s13054-019-2491-9. PMC 6563376. PMID 31189475.

- ^ Tregoning JS, Russell RF, Kinnear E (March 2018). "Adjuvanted influenza vaccines". Human Vaccines & Immunotherapeutics. 14 (3): 550–564. doi:10.1080/21645515.2017.1415684. PMC 5861793. PMID 29232151.