Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Gas lighting

View on Wikipedia

This article has multiple issues. Please help improve it or discuss these issues on the talk page. (Learn how and when to remove these messages)

|

Gas lighting is the production of artificial light from combustion of a fuel gas such as natural gas, methane, propane, butane, acetylene, ethylene, hydrogen, carbon monoxide, or coal gas (sometimes called town gas).[1][2] The light is produced either directly by the flame, generally by using special mixes (typically propane or butane) of illuminating gas to increase brightness, or indirectly with other components such as the gas mantle or the limelight, with the gas primarily functioning to heat the mantle or the lime to incandescence.[1]

Before electricity became sufficiently widespread and economical to allow for general public use, gas lighting was prevalent for outdoor and indoor use in cities and suburbs where the infrastructure for distribution of gas was practical.[1] At that time, the most common fuels for gas lighting were wood gas, coal gas and, in limited cases, water gas.[3] Early gas lights were ignited manually by lamplighters, although many later designs are self-igniting.[4]

Some urban historical districts retain gas street lighting, and gas lighting is used indoors or outdoors to create or preserve a nostalgic effect.[5]

History of gas lighting

[edit]Background

[edit]

Prior to use of gaseous fuels for lighting, the early lighting fuels consisted of olive oil, beeswax, fish oil, whale oil, sesame oil, nut oil, or other similar substances, which were all liquid fuels. These were the most commonly used fuels until the late 18th century. Whale oil was especially widely used for lighting in European cities such as London through the early 19th century.[3]

Chinese records dating back 1,700 years indicate the use of natural gas in homes for lighting and heating. The natural gas was transported by means of bamboo pipes to homes.[6][additional citation(s) needed]

Public illumination preceded by centuries the development and widespread adoption of gas lighting. In 1417, Sir Henry Barton, Lord Mayor of London, ordained "Lanthornes with lights to bee hanged out on the Winter evening betwixt Hallowtide and Candlemassee."[7][8][9][10][11] Paris was first illuminated by an order issued in 1524, and, in the beginning of the 16th century, the inhabitants were ordered to keep lights burning in the windows of all houses that faced streets.[12] In 1668, when some regulations were made for improving the streets of London, the residents were reminded to hang out their lanterns at the usual time, and, in 1690, an order was issued to hang out a light, or lamp, every night at nightfall, from Michaelmas to Christmas. By an Act of the Common Council in 1716, all housekeepers, whose houses faced any street, lane, or passage, were required to hang out, every dark night, one or more lights, to burn from six to eleven o'clock, under the penalty of one shilling as a fine for failing to do so.[13]

Accumulating and escaping gases were known originally among coal miners for their adverse effects rather than their useful characteristics. Coal miners described two types of gases, one called the choke damp and the other fire damp. In 1667, a paper detailing the effects of these gases was entitled, "A Description of a Well and Earth in Lancashire taking Fire, by a Candle approaching to it. Imparted by Thomas Shirley, Esq an eye-witness."[14]

British clergyman and scientist Stephen Hales experimented with the actual distillation of coal, thereby obtaining a flammable liquid. He reported his results in the first volume of his Vegetable Statics, published in 1726. From the distillation of "one hundred and fifty-eight grains [10.2 g] of Newcastle coal, he stated that he obtained 180 cubic inches [2.9 L] of gas, which weighed 51 grains [3.3 g], being nearly one third of the whole."[15] Hales's results garnered attention decades later as the unique chemical properties of various gases became understood through the work of Joseph Black, Henry Cavendish, Alessandro Volta, and others.[16]

A 1733 publication by Sir James Lowther in the Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society detailed some properties of coal gas, including its flammability. Lowther demonstrated the principal properties of coal gas to different members of the Royal Society. He showed that the gas retained its flammability after storage for some time. The demonstration did not result in identification of utility.[17]

Minister and experimentalist John Clayton referred to coal gas as the "spirit" of coal. He discovered its flammability by an accident. The "spirit" he isolated from coal caught fire by coming in contact with a candle as it escaped from a fracture in one of his distillation vessels. He stored the coal gas in bladders, and at times he entertained his friends by demonstrating the flammability of the gas. Clayton published his findings in Philosophical Transactions.[18]

Early technology

[edit]

It took nearly 200 years for gas to become accessible for commercial use.[clarification needed] A Flemish alchemist, Jan Baptista van Helmont, was the first person to formally recognize gas as a state of matter. He would go on to identify several types of gases, including carbon dioxide. Over one hundred years later in 1733, Sir James Lowther had some of his miners working on a water pit for his mine. While digging the pit they hit a pocket of gas. Lowther took a sample of the gas and took it home to do some experiments. He noted, "The said air being put into a bladder … and tied close, may be carried away, and kept some days, and being afterwards pressed gently through a small pipe into the flame of a candle, will take fire, and burn at the end of the pipe as long as the bladder is gently pressed to feed the flame, and when taken from the candle after it is so lighted, it will continue burning till there is no more air left in the bladder to supply the flame."[19] Lowther had basically discovered the principle behind gas lighting.

Later in the 18th century William Murdoch (sometimes spelled "Murdock") stated: "the gas obtained by distillation from coal, peat, wood and other inflammable substances burnt with great brilliancy upon being set fire to … by conducting it through tubes, it might be employed as an economical substitute for lamps and candles."[20] Murdoch's first invention was a lantern with a gas-filled bladder attached to a jet. He would use this to walk home at night. After seeing how well this worked he decided to light his home with gas. In 1797, Murdoch installed gas lighting in his new home as well as the workshop in which he worked. "This work was of a large scale, and he next experimented to find better ways of producing, purifying, and burning the gas."[21] The foundation had been laid for companies to start producing gas and other inventors to start playing with ways of using the new technology.

Murdoch was the first to exploit the flammability of gas for the practical application of lighting. He worked for Matthew Boulton and James Watt at their Soho Foundry steam engine works in Birmingham, England. In the early 1790s, while overseeing the use of his company's steam engines in tin mining in Cornwall, Murdoch began experimenting with various types of gas, finally settling on coal gas as the most effective. He first lit his own house in Redruth, Cornwall in 1792.[22] In 1798, he used gas to light the main building of the Soho Foundry and in 1802 lit the outside in a public display of gas lighting, the lights astonishing the local population. One of the employees at the Soho Foundry, Samuel Clegg, saw the potential of this new form of lighting. Clegg left his job to set up his own gas lighting business, the Gas Light and Coke Company.[citation needed]

A "thermolampe" using gas distilled from wood was patented in 1799, while German inventor Friedrich Winzer (Frederick Albert Winsor) was the first person to patent coal-gas lighting in 1804.

In 1801, Phillipe Lebon of Paris had also used gas lights to illuminate his house and gardens, and was considering how to light all of Paris. In 1820, Paris adopted gas street lighting.

In 1804, William Henry delivered a course of lectures on chemistry, at Manchester, in which he showed the mode of producing gas from coal, and the facility and advantage of its use. Henry analysed the composition and investigated the properties of carburetted hydrogen gas (i.e. methane). His experiments were numerous and accurate and made upon a variety of substances; having obtained the gas from wood, peat, different kinds of coal, oil, wax, etc., he quantified the intensity of the light from each source.[citation needed]

In 1806 The Philips and Lee factory and a portion of Chapel Street in Salford, Lancashire were lit by gas, thought to be the first use of gas street lighting in the world.

Josiah Pemberton, an inventor, had for some time been experimenting on the nature of gas. A resident of Birmingham, his attention may have been roused by the exhibition at Soho. About 1806, he exhibited gas lights in a variety of forms and with great brilliance at the front of his factory in Birmingham. In 1808 he constructed an apparatus, applicable for several uses, for Benjamin Cooke, a manufacturer of brass tubes, gilt toys, and other articles.

In 1808, Murdoch presented to the Royal Society a paper entitled "Account of the Application of Gas from Coal to Economical Purposes" in which he described his successful application of coal gas to light the extensive establishment of Messrs. Phillips and Lea. For this paper he was awarded Count Rumford's gold medal.[23] Murdoch's statements threw great light on the comparative advantage of gas and candles, and contained much useful information on the expenses of production and management.

Although the history is uncertain, David Melville has been credited[24][25][26][27] with the first house and street lighting in the United States, in either 1805 or 1806 in Newport, Rhode Island.

In 1809, accordingly, the first application was made to Parliament to incorporate a company in order to accelerate the process, but the bill failed to pass. In 1810, however, the application was renewed by the same parties, and though some opposition was encountered and considerable expense incurred, the bill passed, but not without great alterations; and the London and Westminster Gas Light and Coke Company was established. Less than two years later, on 31 December 1813, Westminster Bridge was lit by gas.[28]

Widespread use

[edit]

Among the economic impacts of gas lighting was much longer work hours in factories. This was particularly important in Great Britain during the winter months when nights are significantly longer. Factories could even work continuously over 24 hours, resulting in increased production. Following successful commercialization, gas lighting spread to other countries.

In England, the first place outside London to have gas lighting was Preston, Lancashire, in 1816; this was due to the Preston Gaslight Company run by revolutionary Joseph Dunn, who found the most improved way[clarification needed] of brighter gas lighting. The parish church there was the first religious building to be lit by gas lighting.[29]

In Bristol, a Gas Light Company was founded on 15 December 1815. Under the supervision of the engineer, John Brelliat, extensive works were conducted in 1816–17 to build a gasholder, mains and street lights. Many of the principal streets in the centre of the city, as well as nearby houses, had switched to gas lighting by the end of 1817.[30]

In America, Seth Bemis lit his factory with gas illumination from 1812 to 1813. The use of gas lights in Rembrandt Peale's Museum in Baltimore in 1816 was a great success. Baltimore was the first American city with gas street lights; Peale's Gas Light Company of Baltimore on 7 February 1817 lit its first street lamp at Market and Lemon Streets (currently Baltimore and Holliday Streets). The first private residence in the US to be illuminated by gas has been variously identified as that of David Melville (c. 1806), as described above, or of William Henry, a coppersmith, at 200 Lombard Street, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, in 1816.

In 1817, at the three stations of the Chartered Gas Company in London, 25 chaldrons (24 m3) of coal were carbonized daily, producing 300,000 cubic feet (8,500 cubic metres) of gas. This supplied gas lamps equal to 75,000 Argand lamps each yielding the light of six candles. At the City Gas Works, in Dorset Street, Blackfriars, three chaldrons of coal were carbonized each day, providing the gas equivalent of 9,000 Argand lamps. So 28 chaldrons of coal were carbonized daily, and 84,000 lights supplied by those two companies only.

At this period the principal difficulty in gas manufacture was purification. Mr. D. Wilson, of Dublin, patented a method for purifying coal gas by means of the chemical action of ammoniacal gas.[clarification needed] Another plan was devised by Reuben Phillips, of Exeter, who patented the purification of coal gas by the use of dry lime. G. Holworthy, in 1818, patented a method of purifying it by passing the gas, in a highly condensed state, through iron retorts heated to a dark red.

In 1820, Swedish inventor Johan Patrik Ljungström had developed a gas lighting with copper apparatuses and chandeliers of ink, brass and crystal, reportedly one of the first such public installations of gas lighting in the region, enhanced as a triumphal arch for the city gate for a royal visit of Charles XIV John of Sweden in 1820.[31]

By 1823, numerous towns and cities throughout Britain were lit by gas. Gas light cost up to 75% less than oil lamps or candles, which helped to accelerate its development and deployment. By 1859, gas lighting was to be found all over Britain and about a thousand gas works had sprung up to meet the demand for the new fuel. The brighter lighting which gas provided allowed people to read more easily and for longer. This helped to stimulate literacy and learning, speeding up the second Industrial Revolution.

In 1824 the English Association for Gas Lighting on the Continent, a sizeable business producing gas for several cities in mainland, Europe, including Berlin, was established, with Sir William Congreve, 2nd Baronet as general manager.[32]

The 1839 invention, the Bude-Light, provided a brighter and more economical lamp.[33]

Oil-gas appeared in the field as a rival of coal gas. In 1815, John Taylor patented an apparatus for the decomposition of "oil" and other animal substances. Public attention was attracted to "oil-gas" by the display of the patent apparatus at Apothecary's Hall, by Taylor & Martineau.

In 1891 the gas mantle was invented by the Austrian chemist Carl Auer von Welsbach. This eliminated the need for special illuminating gas (a synthetic mixture of hydrogen and hydrocarbon gases produced by destructive distillation of bituminous coal or peat) to get bright shining flames. Acetylene was also used from about 1898 for gas lighting on a smaller scale.[34]

Illuminating gas was used for gas lighting, as it produces a much brighter light than natural gas or water gas. Illuminating gas was much less toxic than other forms of coal gas, but less could be produced from a given quantity of coal. The experiments with distilling coal were described by John Clayton in 1684. George Dixon's pilot plant exploded in 1760, setting back the production of illuminating gas a few years. The first commercial application was in a Manchester cotton mill in 1806. In 1901, studies of the defoliant effect of leaking gas pipes led to the discovery that ethylene is a plant hormone.

Throughout the 19th century and into the first decades of the 20th, the gas was manufactured by the gasification of coal. Later in the 19th century, natural gas began to replace coal gas, first in the US, and then in other parts of the world. In the United Kingdom, coal gas was used until the early 1970s.

Russia

[edit]The history of the Russian gas industry began with retired Lieutenant Pyotr Sobolevsky (1782–1841), who improved Philippe le Bon's design for a "thermolamp" and presented it to Emperor Alexander I in 1811; in January 1812, Sobolevsky was instructed to draw up a plan for gas street-lighting for St. Petersburg. The French invasion of Russia delayed implementation, but St. Petersburg's Governor General Mikhail Miloradovich, who had seen the gas lighting of Vienna, Paris and other European cities, initiated experimental work on gas lighting for the capital, using British apparatus for obtaining gas from pit coal, and by the autumn of 1819, Russia's first gas street light was lit on one of the streets on Aptekarsky Island.[35]

In February 1835, the Company for Gas Lighting St. Petersburg was founded.[35] Towards the end of that year, a factory for the production of lighting gas was constructed near the Obvodny Canal, using pit coal shipped in overseas from Cardiff, and 204 gas lamps were lit ceremonially in St. Petersburg on 27 September 1839.[35]

Over the next 10 years, their numbers almost quadrupled, to reach 800. By the middle of the 19th century, the central streets and buildings of the capital were illuminated: the Palace Square, Bolshaya and Malaya Morskaya streets, Nevsky and Tsarskoselsky Avenues, Passage Arcade, Noblemen's Assembly, the Technical Institute and Peter and Paul Fortress.[35]

Theatrical use

[edit]

It took many years of development and testing before gas lighting for the stage was commercially available. Gas technology was then installed in just about every major theatre in the world. But gas lighting was short-lived because the electric light bulb soon followed.

In the 19th century, gas stage lighting went from a crude experiment to the most popular way of lighting theatrical stages. In 1804, Frederick Albert Winsor first demonstrated the way to use gas to light the stage in London at the Lyceum Theatre. Although the demonstration and all the lead research were being done in London, "in 1816 at the Chestnut Street Theatre in Philadelphia was the earliest gas lit theatre in world".[36] In 1817 the Lyceum, Drury Lane, and Covent Garden theatres were all lit by gas. Gas was brought into the building by "miles of rubber tubing from outlets in the floor called 'water joints'" which "carried the gas to border-lights and wing lights". But before it was distributed, the gas came through a central distribution point called a "gas table",[37] which varied the brightness by regulating the gas supply, and the gas table, which allowed control of separate parts of the stage. Thus it became the first stage 'switchboard'.[38]

By the 1850s, gas lighting in theatres had spread practically all over the United States and Europe. Some of the largest installations of gas lighting were in large auditoriums, like the Théâtre du Chatelet, built in 1862.[39] In 1875, the new Paris Opera was constructed. "Its lighting system contained more than twenty-eight miles [45 km] of gas piping, and its gas table had no fewer than eighty-eight stopcocks, which controlled nine hundred and sixty gas jets."[39] The theatre that used the most gas lighting was Astley's Equestrian Amphitheatre in London. According to the Illustrated London News, "Everywhere white and gold meets the eye, and about 200,000 gas jets add to the glittering effect of the auditorium … such a blaze of light and splendour has scarcely ever been witnessed, even in dreams."[39]

Theatres switched to gas lighting because it was more economical than using candles and also required less labour to operate. With gas lighting, theatres would no longer need to have people tending to candles during a performance, or having to light each candle individually. "It was easier to light a row of gas jets than a greater quantity of candles high in the air."[38] Theatres also no longer needed to worry about wax dripping on the actors during a show.

Gas lighting also had an effect on the actors. As the stage was brighter, they could now use less make-up and their motions did not have to be as exaggerated. Half-lit stages had become fully lit stages. Production companies were so impressed with the new technology that one said, "This light is perfect for the stage. One can obtain gradation of brightness that is really magical."[38]

The best result was the improved respect from the audience. There was no more shouting or riots. The light pushed the actors more up stage behind the proscenium, helping the audience concentrate more on the action that was taking place on stage rather than what was going on in the house. Management had more authority on what went on during the show because they could see.[40] Gaslight was the leading cause of behaviour change in theatres. They were no longer places for mingling and orange selling, but places of respected entertainment.

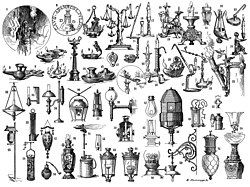

Types of lighting instruments

[edit]There were six types of burners, but four burners were really experimented with:[clarification needed]

- The first burner used was the single-jet burner, which produced a small flame. The tip of the burner was made out of lead, which absorbed heat, causing the flame to be smaller in size. It was discovered that the flame would burn brighter if the metal was mixed with other components, such as porcelain.

- Flat burners were invented mainly to distribute gas and light evenly to the systems.

- The fishtail burner was similar to the flat burner, but it produced a brighter flame and conducted less heat.

- The last burner that was experimented with was the Welsbach burner. Around this time the Bunsen burner was in use along with some forms of electricity. The Welsbach was based on the idea of the Bunsen burner, still using gas. A cotton mesh with cerium and thorium was imbedded into the Welsbach. This source of light was named the gas mantle; it produced three times more light than the naked flame.[41]

Several different instruments were used for stage lighting in the 19th century fell; these included footlights, border lights, groundrows, lengths, bunch lights, conical reflector floods, and limelight spots. These mechanisms sat directly on the stage, blinding the eyes of the audience.

- Footlights caused the actors' costumes to catch fire if they got too close. These lights also caused bothersome heat that affected both audience members and actors. Again, the actors had to adapt to these changes. They started fireproofing their costumes and placing wire mesh in front of the footlights.

- Border lights, also known as striplights, were a row of lights that hung horizontally in the flies. Color was added later by dying cotton, wool, and silk cloth.

- Lengths were constructed the same way as border lights, but mounted vertically in the rear where the wings were.

- Bunch lights were a cluster of burners that sat on a vertical base that was fuelled directly from the gas line.

- The conical reflector can be related to the Fresnel lens used today. This adjustable box of light reflected a beam whose size could be altered by a barndoor.[clarification needed]

- Limelight spots are similar to today's current spotlighting system. This instrument was used in scene shops, as well as the stage.[42]

Gas lighting did have some disadvantages. "Several hundred theatres are said to have burned down in America and Europe between 1800 and the introduction of electricity in the late 1800s. The increased heat was objectionable, and the border lights and wing lights had to be lighted by a long stick with a flaming wad of cotton at the end. For many years, an attendant or gas boy moved along the long row of jets, lighting them individually while gas was escaping from the whole row. Both actors and audiences complained of the escaping gas, and explosions sometimes resulted from its accumulation."[37]

These problems with gas lighting led to the rapid adoption of electric lighting. By 1881, the Savoy Theatre in London was using incandescent lighting.[43] While electric lighting was introduced to theatre stages, the gas mantle was developed in 1885 for gas-lit theatres. "This was a beehive-shaped mesh of knitted thread impregnated with lime that, in miniature, converted the naked gas flame into in effect, a lime-light."[44] Electric lighting slowly took over in theatres. In the 20th century, it enabled better and safer theatre productions, with no smell, relatively very little heat, and more freedom for designers.

Decline

[edit]

In the early 20th century, most cities in North America and Europe had gaslit streets, and most railway station platforms had gas lights too. However, around 1880 gas lighting for streets and train stations began giving way to high voltage (3,000–6,000 volt) direct current and alternating current arc lighting systems. This time period also saw the development of the first electric power utility designed for indoor use. The new system by inventor Thomas Edison was designed to function similar to gas lighting. For reasons of safety and simplicity it used direct current (DC) at a relatively low 110 volts to light incandescent light bulbs. Voltage in wires steadily declines as distance increases, and at this low voltage power plants needed to be within about 1 mile (1.6 km) of the lamps. This voltage drop problem made DC distribution relatively expensive and gas lighting retained widespread usage[45] with new buildings sometimes constructed with dual systems of gas piping and electrical wiring connected to each room, to diversify the power sources for lighting.

The development of new alternating current power transmission systems in the 1880s and 90s by companies such as Ganz and AEG in Europe and Westinghouse Electric and Thomson-Houston in the US solved the voltage and distance problem by using high transmission line voltages, and transformers to drop the voltage for distribution for indoor lighting. Alternating current technology overcame many of the limitations of direct current, enabling the rapid growth of reliable, low-cost electrical power networks which finally spelled the end of widespread usage of gas lighting.[45]

Modern usage

[edit]Outdoors

[edit]

In some cities, gas lighting is preserved or restored as a vintage nostalgic feature to support the historic atmosphere of their historic centres.

In the 20th century, most cities with gas streetlights replaced them with new electric streetlights. For example, Baltimore, the first US city to install gas streetlights, removed nearly all of them.[46] A sole, token gas lamp is located at N. Holliday Street and E. Baltimore Street as a monument to the first gas lamp in America, erected at that location.

However, gas lighting of streets has not disappeared completely from some cities, and the few municipalities that retained gas lighting now find that it provides a pleasing nostalgic effect. Gas lighting is also seeing a resurgence in the luxury home market for those in search of historical authenticity.

The largest gas lighting network in the world is that of Berlin. With about 23,000 lamps (2022),[47] it holds more than half of all working gas street lamps in the world, followed by Düsseldorf with 14,000 lamps (2020), of which at least 10,000 are to be retained.[48]

In London there were about 1,500 working gas street lamps as of 2018,[update] although there were plans to replace 299 of those in Westminster (the first city in the world lit by gas) with LED lighting by 2023, which sparked public opposition.[49][50][51][52]

In the United States, more than 2800 gas lights in Boston operate in the historic districts of Beacon Hill, Back Bay, Bay Village, Charlestown, and parts of other neighbourhoods. In Cincinnati, Ohio, more than 1100 gas lights operate in areas that have been named historic districts. Gas lights also operate in parts of the famed French Quarter and outside historic homes throughout the city in New Orleans.[citation needed]

Zagreb, the capital of Croatia, has used gas candelabras since 1863. Initially, Zagreb was illuminated by 60,000 lamps, but as of 1987,[update] only 248 gas street lamps illuminate old parts of the city.[53] Zagreb gas lamps are manually managed by lamplighters.[53]

Prague, where gas lighting was introduced on 15 September 1847,[54] had about 10,000 gas streetlamps in the 1940s. The last historic gas candelabras become electrified in 1985.[55] However, in 2002–2014, streetlamps along the Royal Route and some other streets in the centre were rebuilt to use gas (using replicas of the historic poles and lanterns), several historic candelabras (Hradčanské náměstí, Loretánská street, Dražického náměstí etc.) were also converted back to gas lamps, and five new gas lamps were installed in the Michle Gasworks as a promotion.[56] In 2018, there were 417 points (about 650 lanterns) of street gas lighting in Prague.[57][58] During Advent and Christmas, lanterns on the Charles Bridge are managed manually by a lamplighter in historic uniform.[59] The plan to reintroduce gas lights in Old Prague was proposed in 2002, and adopted by the Municipality of Prague in January 2004.[60]

Other uses

[edit]Perforated tubes bent into the shape of letters were used to form gas lit advertising signs, prior to the introduction of neon lights, as early as 1857 in Grand Rapids, Michigan.[61] Gas lighting is still in common use for camping lights. Small portable gas lamps, connected to a portable gas cylinder, are a common item on camping trips. Mantle lamps powered by vaporized petrol, such as the Coleman lantern, are also available.

Image gallery

[edit]-

Outdoor installation of gaslamps compared with new electric lighting (London, 1878)

-

Reproduction of an early European exterior gaslamp (Germany)

-

Gaslit school hallway (Paris, late 19th century)

-

Poster advertising Bec Auer gaslamps (France, 1890s)

-

Poster showing benefits of gaslighting and heating (Italy, 1902)

-

Portable gas desk lamp (c. 1900-1910)

See also

[edit]- Blau gas – Artificial illuminating gas similar to propane

- Carbide lamp – Acetylene-burning lamps

- Carbochemistry – Branch of chemistry

- Gaslaternen-Freilichtmuseum Berlin – An outdoor gas lantern museum in Berlin

- History of manufactured fuel gases

- Limelight – Type of stage lighting once used in theatres and music halls

- List of light sources

- Sewer gas destructor lamp – Street lamp powered by burning sewer gas

- Thomas Thorp

- Tilley lamp – Pressurized kerosene lamps made by the Tilley company in the UK

References

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ a b c Sweeney, Morgan (17 December 2019). "Before Electricity, Streets Were Filled with Gas Lights". McGill.ca. McGill University Office for Science and Society. Retrieved 21 August 2025.

- ^ Wells, B. A.; Wells, K. L. (30 January 2016). "Illuminating Gaslight". American Oil and Gas Historical Society. Retrieved 22 August 2025.

- ^ a b Binder, Frederick Moore (October 1955). "Gas Light". Pennsylvania History: A Journal of Mid-Atlantic Studies. 22 (4): 359–373. JSTOR 27769625. Retrieved 20 February 2022.

- ^ Arsiya, Iklim (29 April 2017). "Jobs of Yesteryear: Obsolete Occupations". DailySabah.com. Retrieved 19 February 2022.

- ^ Patowary, Kaushik. "The Last Gas Streetlights". AmusingPlanet.com. Amusing Planet. Retrieved 19 February 2022.

- ^ James, P.; Thorpe, N.; Thorpe, I.J. (1995). Ancient Inventions. Ballantine Books. pp. 427–428. ISBN 978-0-345-40102-1. Citing Ch'ang Ch'ü (常璩, a geographer). Records of the country south of Mount Kua 華陽國志 (in Chinese).

- ^ Stow, John (1908) [1603]. "Temporall government". In Kingsford, C. L. (ed.). A Survey of London. Oxford. pp. 147–187. Retrieved 5 November 2021 – via British History Online.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Osborne, Edward Cornelius; Osborne, W. (1840). Osborne's London and Birmingham Railway Guide. p. 244.

- ^ The Gas-consumer's Guide: A Hand-book of Instruction on the Proper Management and Economical Use of Gas; with a Full Description of Gas-meters, and Directions for Ascertaining the Consumption by Meter; on Ventilation, Etc. United States: Alexander Moore. 1871. p. 13.

- ^ Domestic Life in England, from the Earliest Period to the Present Time: With Notices of Origins, Inventions, and Modern Improvements in the Social Arts. Ireland: Thomas Tegg and Son. 1835. p. 157.

- ^ Roskell, J.S.; Clark, L.; Rawcliffe, C., eds. (1993). "Barton, Henry (d.1435)". The History of Parliament: the House of Commons 1386-1421.

The introduction of a scheme for proper street lighting in the city is generally attributed to Barton, although there is no direct evidence for this.

- ^ The Young Man's Evening Book. New York: Charles S. Francis. 1838. p. 31.

- ^ Entick, John (1766). A New and Accurate History and Survey of London, Westminster, Southwark, and Places Adjacent. Vol. 2. pp. 373–374.

- ^ Shirley, Thomas (1667). "A Description of a Well and Earth in Lancashire taking Fire, by a Candle approaching to it". Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society. London.

- ^ Hales, Stephen (1727). Vegetable Staticks: Or, an Account of Some Statical Experiments on the Sap in Vegetables: Being an Essay Towards a Natural History of Vegetation. Also, a Specimen of an Attempt to Analyse the Air, by a Great Variety of Chymio-statical Experiments. London: W. and J. Innys. p. 176.

- ^ "Air and Water". Cavendish: Air and Water. MPRL – Studies. Max Planck Research Library. 27 September 2016. ISBN 978-3-945561-06-5. Retrieved 14 July 2024.

- ^ Lowther, James (1 August 1733). "III. An account of the damp air in a coal-pit of Sir James Lowther, Bart. Sunk within 20 Yards of the sea; communicated by him to the Royal Society". Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society. 38 (429): 109–113. doi:10.1098/rstl.1733.0019. S2CID 186210832.

- ^ Maud, John; Lowther, James (1735). "VI. A Chemical Experiment by Mr. John Maud, Serving to Illustrate the Phœnomenon of the Inflammable Air Shewn to the Royal Society by Sir James Lowther, Bart. as Described in Philosoph. Transact. Numb. 429". Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society. 39 (442): 282–285. doi:10.1098/rstl.1735.0057. S2CID 186208578.

- ^ Penzel 1978, p. 28.

- ^ Penzel 1978, p. 29.

- ^ Penzel 1978, p. 30.

- ^ Thomson, Janet (2003). The Scot Who Lit The World, The Story of William Murdoch Inventor of Gas Lighting. Janet Thomson. ISBN 0-9530013-2-6.

- ^ "Rumford Archive Winners 1898–1800". Royal Society. Archived from the original on 10 February 2008.

- ^ "Melville's Gas Apparatus". American Gas Light Journal. New York: A. M. Callender & Co. 2 March 1876. p. 92.

- ^ Clark, Walton (1916). "Progress of Gas Lighting Appliances During Past Century". The Gas Age. Progressive Age Publishing Co. p. 122.

- ^ Mattausch, Daniel W. "David Melville And The First American Gas Light Patents". The Rushlight Club. Retrieved 25 March 2018.

- ^ "Gas Lighting in Newport". Newport Historical Society. 13 December 2016. Retrieved 25 March 2018.

- ^ Kennedy, Maev (25 December 2015). "Light Brigade: Carrying the Torch for London's Last Gas Street Lamps". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 25 December 2015.

- ^ Hewitson, Anthony (1883). History (from A.D. 705 to 1883) of Preston in the County of Lancaster. Chronicle Office. p. 268.

- ^ Nabb, Harold (1987). The Bristol Gas Industry 1815–1949. Bristol Historical Association. pp. 4–6.

- ^ Rådhus, Åmåls (10 February 1827). Protocol. J. Jacobson.

- ^ "President's Address" (PDF). Transactions of the Norfolk and Norwich Naturalists' Society. X (5): 407. 1919.

- ^ Bethell, John (1843–1844). . Transactions of the Society, Instituted at London, for the Encouragement of Arts, Manufactures, and Commerce. 54: 198–200 – via Wikisource.

- ^ "Celebrating 100 Years as the Standard for Safety: The Compressed Gas Association, Inc. 1913–2013" (PDF). CGanet.com. 11 September 2013. Archived from the original (PDF) on 26 June 2017.

- ^ a b c d Yefimov, Alexander; Volkova, Lyudmila (2005). "Pioneers of the Methane Age". Oil of Russia: International Quarterly Edition. No. 2. Archived from the original on 22 December 2005. Retrieved 23 May 2025.

- ^ Wilson,362

- ^ a b Sellman 15

- ^ a b c Pilbrow 174

- ^ a b c Penzel 69

- ^ Penzel 54

- ^ Penzel 89

- ^ Penzel 95

- ^ Wilson 364

- ^ Baugh, 24

- ^ a b Gow, A. M. (1917). "A bit of Engineering History: The story of the fuel gas and electrical engineering company". The Electric Journal. 14. The Westinghouse Club: 181–183.[permanent dead link]

- ^ Rasmussen, Frederick (10 October 1998). "City's Gaslight Glow Dimmed in 1957 Progress: The American gas industry was born in Baltimore in 1816, when an artist wanted a clean, smoke-free way to illuminate a roomful of paintings". Baltimore Sun. Archived from the original on 11 June 2016. Retrieved 22 June 2013.

- ^ "Gasbeleuchtung in Berlin". 2 June 2022. Archived from the original on 26 June 2022.

- ^ Turnsek, Andreas (16 January 2020). "Erfolg für Bürgerinitiative: Gaslaternen in Düsseldorf sollen bleiben" [Success for Citizens' Initiative: Gas Lanterns in Düsseldorf to Stay] (in German). Archived from the original on 24 May 2020.

- ^ Ellen, Tom (24 November 2022). "Meet the campaigners who saved London's historic gas lamps". Evening Standard. Retrieved 18 August 2023.

- ^ "Campaign fighting to save hundreds of London's gas lamps". BBC News. 3 October 2022. Retrieved 18 August 2023.

- ^ Sherwood, Harriet (21 November 2021). "Plan to Change Westminster's Historic Gas Street Lights to LEDs Sparks Anger". The Observer.

- ^ Fraser, Steve (2018). "Exploring London's Gas Lights (a Walk Itinerary)" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 21 November 2021.

- ^ a b "Plinska rasvjeta" [Gas Lighting]. Plinara-zagreb.hr (in Croatian). Zagreb City Gas Company (Gradska plinara Zagreb ). Retrieved 24 January 2025.

- ^ T., Lidia (1 October 2019). "The Magic of Gas Lamps in Prague". Prague Morning. Retrieved 20 February 2021.

- ^ Robert Oppelt: Pouliční lampy svítí už 160 let. MF Dnes, 15. September 2007

- ^ Tomáš Belica: Rozhovor: Plynové lampy mají v Praze své místo, říká lampář, Metro.cz, 15 September 2014

- ^ Monzer, Ladislav (26 October 2018). "Pražské veřejné osvětlení v letech 1918–2018" [Prague Public Lighting in the Years 1918–2018]. Prahasviti.cz (in Czech). Archived from the original on 28 October 2018.

- ^ Technologie hlavního města Prahy správcem plynového osvětlení Královské cesty, Pražský patriot, 21 May 2018

- ^ Lampář na Karlově mostě, Portál hlavního města Prahy, 21 November 2017

- ^ Vesela, Zuzana (9 January 2004). "Old-Fashioned Gas Lamps Make a Comeback to Prague". Radio Prague International. Retrieved 20 February 2021.

- ^ "Lighting City Streets, 1850s to 1950s". Grand Rapids History. Grand Rapids Historical Commission. 30 May 2007. Archived from the original on 24 November 2010. Retrieved 5 January 2011.

Bibliography

[edit]- Baugh, Christopher (2005). Theatre, Performance and Technology: The Development of Scenography in the Twentieth Century (1st ed.). Palgrave MacMillan. pp. 96–97. ISBN 978-1-4039-1696-9.

- Chastain, Ben B. (8 January 2021). "Jan Baptista van Helmont". Encyclopædia Britannica.

- Penzel, Frederick (1978). Theatre Lighting Before Electricity (1st ed.). Middletown, Connecticut: Wesleyan University Press. pp. 27–152. ISBN 978-0-8195-5021-7.

- Pilbrow, Richard (1997). Stage Lighting Design: The Art, The Craft, The Life (1st ed.). New York: Design Press. pp. 172–176. ISBN 978-1-85459-273-6.

- Sellman, Hunton; Lessley, Merrill (1982). Essentials of Stage Lighting (2nd ed.). Englewood Cliffs, New Jersey: Prentice-Hall. pp. 14–17. ISBN 978-0-13-289249-0.

- Wilson, Edwin; Goldfarb, Alvin (2006). Living Theatre: A History (5th ed.). New York: McGraw-Hill. pp. 364–367. ISBN 978-0-07-351412-3.

Further reading

[edit]- Rennie, Alex (1 June 2023). "The Last Days of Berlin's Gas Streetlamps". Atlas Obscura. Retrieved 2 June 2023.

External links

[edit]- Pro Gaslicht e.V. : Association for the Preservation of the European Gas-light Culture (German). Listing of the cities with gaslight.

- Gaslaternen-Freilichtmuseum Berlin Open-air museum on gas lighting in Berlin (German).

Gas lighting

View on GrokipediaFundamentals

Principles of Operation

Gas lighting operates through the combustion of illuminating gases, such as coal gas or natural gas, which are ignited in a controlled flame to produce visible light. The process begins with the gas being released from a supply line and mixed with atmospheric air at the burner, where ignition creates a flame. In early open-flame designs, light is emitted primarily from the incandescence of soot particles formed during incomplete combustion of hydrocarbons in the gas, resulting in a yellow-orange glow. With the introduction of incandescent mantles in the late 19th century, the flame heats a ceramic mesh typically composed of thorium oxide doped with cerium oxide, causing it to incandesce at temperatures around 1700–1900°C and emit brighter white light more efficiently.[4][5] Key components of a gas lighting burner ensure proper combustion and flame control. The burner nozzle, often precision-machined from materials like porcelain or steatite, regulates the gas flow rate to form a stable flame shape, preventing excessive flickering or extinction. Air inlets, positioned around or within the burner (as in the Argand-style design with concentric tubes), supply oxygen for mixing with the gas prior to ignition, enabling complete combustion and maximizing light output. Flame stabilization is achieved through mechanisms such as pressure governors that maintain consistent gas delivery and burner geometries that create low-velocity zones for anchoring the flame, reducing sensitivity to drafts.[5][4] The efficiency of gas lighting is characterized by its luminous efficacy, historically ranging from about 0.1 lm/W for open-flame burners to 1–3 lm/W for mantle-equipped systems, a significant improvement that extended the viability of gas illumination into the electrical era. This efficacy depends on factors like gas pressure, which affects flow and mixing, and the air-to-gas ratio, where optimal oxygenation minimizes soot while promoting incandescence without excessive heat loss. Mantles, for instance, increased light output by up to tenfold compared to flat-flame designs by shifting emission toward visible wavelengths with reduced infrared radiation.[4][6][5] Combustion in gas lighting generates substantial heat alongside light, with byproducts including carbon dioxide (CO₂), water vapor (H₂O), and trace amounts of soot or unburned hydrocarbons depending on the completeness of the reaction. For natural gas, primarily methane (CH₄), the idealized complete combustion equation is: This exothermic reaction releases energy that sustains the flame and incandescence, though real-world conditions often produce minor pollutants due to imperfect mixing. Coal gas, a mixture including hydrogen and carbon monoxide, follows analogous hydrocarbon oxidation pathways.[7][4]Types of Illuminating Gas

The primary type of illuminating gas developed in the early modern period was coal gas, produced through the destructive distillation of coal, where the material is heated to high temperatures in the absence of air to yield gaseous products alongside coke and tar.[8] This process, akin to coking, generates a combustible mixture typically comprising approximately 50% hydrogen, 30-35% methane, and 10% carbon monoxide, with smaller amounts of other hydrocarbons and impurities.[9] Coal gas was first utilized for lighting purposes in experiments during the late 18th century, marking the inception of manufactured illuminating gases.[10] Its calorific value, around 10-20 MJ/m³, provided sufficient energy for bright flames but included toxic components like carbon monoxide, posing health risks if unburned.[8] Illuminating gases were primarily manufactured from coal and other materials until the 19th century, when extracted natural gas began to emerge as an alternative, consisting primarily of methane (typically over 90%), with minor traces of ethane, propane, and non-hydrocarbon gases like nitrogen and carbon dioxide.[11] Unlike manufactured gases, it burns more cleanly with lower emissions of soot and toxins, reducing the risks associated with carbon monoxide exposure, though its adoption for widespread lighting required 19th-century advancements in pipeline infrastructure for safe distribution.[12] Initial uses of extracted natural gas for illumination date to the 1820s, such as in Fredonia, New York, where local wells supplied gas for home and street lighting starting in 1821.[12] Other variants included water gas, producer gas, and early oil gas, each offering distinct production methods and trade-offs in efficiency and safety. Water gas is generated by reacting steam with hot coke or coal in a cyclic process, yielding a mixture rich in hydrogen and carbon monoxide via the endothermic reaction .[13] This results in a higher calorific value than producer gas (approximately 12-21 MJ/m³ equivalent) but requires energy input for heating, and its high carbon monoxide content heightens toxicity concerns during combustion. Producer gas, formed by partial oxidation of coal or biomass with air, contains significant nitrogen alongside carbon monoxide, hydrogen, and methane, leading to a low calorific value of about 4.7 MJ/m³ and dilution that limits its practicality for illumination despite simpler production.[13] Early oil gas, produced by cracking petroleum oils under heat, provided a portable option with a calorific value around 20-25 MJ/m³ but was costlier and less scalable than coal-derived gases due to oil scarcity.[14] Over time, the quality of illuminating gases improved through purification techniques targeting impurities like sulfur compounds and ammonia, which caused corrosive deposits, foul odors, and dim flames. Sulfur, primarily as hydrogen sulfide, was removed using iron oxide scrubbers or lime absorption to prevent equipment damage and enhance flame brightness, while ammonia was extracted via acid scrubbing—such as the Mond process introduced in 1889, which sprayed dilute sulfuric acid to recover up to 80% as ammonium sulfate fertilizer.[15] These advancements, refined from the mid-19th century onward, not only boosted safety by mitigating toxicity but also increased luminous efficiency, making gases like coal gas more viable for domestic and public use before the shift to electricity.[15]Historical Development

Invention and Early Experiments

The development of gas lighting emerged from earlier innovations in illumination and fuel distillation. In the 1780s, Swiss chemist Aimé Argand invented the Argand burner, an oil lamp featuring a cylindrical wick surrounded by air channels for a brighter, more efficient flame, which later served as a model for gas adaptations.[16] Independently, French engineer Philippe Lebon patented the "thermolampe" in 1799, a device that burned gas distilled from wood to produce light and heat, marking one of the earliest documented efforts to harness manufactured gas for practical illumination.[17] Scottish engineer William Murdoch, while working for Boulton & Watt in Cornwall, conducted pioneering experiments with coal gas in 1792, distilling the gas from heated coal in a small retort to illuminate his home and offices in Redruth.[18] By 1796, Murdoch had successfully piped the gas through his residence, achieving steady domestic lighting, and he even created a portable lantern by storing gas in an animal bladder attached to a simple jet for nighttime use.[19] These trials demonstrated the feasibility of coal gas as a reliable fuel, though initial production was limited to small-scale setups. The first public demonstration of gas lighting occurred in London on January 28, 1807, when German-born entrepreneur Frederick Albert Winsor illuminated a section of Pall Mall using coal gas from a nearby retort.[20] Early adopters faced significant technical hurdles, including gas storage in makeshift containers like animal bladders or water-filled barrels to maintain pressure, and designing burners—often adaptations of the Argand style with multiple jets—to ensure a stable, non-flickering flame without excessive soot.[19] These innovations laid the groundwork for more robust systems, overcoming issues of gas purity and distribution in rudimentary experiments.Spread and Peak Usage

The rapid expansion of gas lighting in the 19th century began with its introduction in major urban centers, driven by the establishment of dedicated gas companies. In London, the Chartered Gas Light and Coke Company, incorporated by royal charter in 1812, constructed the world's first urban gas network between 1812 and 1820, initially lighting key streets like Pall Mall in 1807 before scaling to broader coverage. By 1819, the company supplied gas to over 51,000 burners across nearly 290 miles of pipes, illuminating thousands of lamps and transforming nighttime navigation in the city. This infrastructure growth continued, with gas lamps becoming ubiquitous on London's streets by the mid-1820s, supporting over 40,000 installations by the early 1830s as demand surged for public and private use.[21][22] Similar rollouts occurred across Europe and North America during the 1820s. Paris adopted gas street lighting in 1820, installing thousands of lamps along its grand boulevards to enhance visibility and urban aesthetics, earning the city its moniker as the "City of Light" for its pioneering illumination of public spaces. In New York, the New York Gas Light Company, incorporated in 1823, laid cast-iron pipes to light Broadway and surrounding streets, marking the first systematic gas network in the United States and facilitating safer passage in the growing metropolis. These developments were fueled by economic incentives, including the formation of private gas enterprises that capitalized on coal resources and ironworking advancements; for instance, production efficiencies reduced gas costs from around £2 per 1,000 cubic feet in the early 1820s to under £1 by mid-century in British cities, making widespread adoption viable for municipalities and businesses.[23][24][25] At its peak in the 1880s, gas lighting had deeply integrated into European and North American societies, powering millions of lamps across urban landscapes and extending daily life beyond sunset. In Britain alone, approximately 1,500 gasworks operated by 1888, supplying street and indoor lighting that lit tens of thousands of lamps in London and other cities, while North American hubs like New York maintained over 26,000 gas street lamps as late as 1893. This illumination improved public safety by reducing crime and accidents compared to dimmer oil lamps or candles, while enabling longer business hours in factories, shops, and theaters—particularly in industrial Britain, where extended operations boosted productivity and economic output. By 1900, gas lighting illuminated the majority of streets in major Western cities, covering an estimated 80% or more of public thoroughfares in places like London, Paris, and New York, solidifying its role as the dominant artificial light source before electrical alternatives emerged.[5][26]Regional Adaptations

In Russia, gas lighting was introduced to St. Petersburg in 1819, when the first lamps were lit on Aptekarsky Island using coal gas produced locally from coal imported from the United Kingdom.[27] The technology relied on British coal for production, with local manufacturing of equipment at facilities like the Arsenal Plant and Porcelain Manufacture to support initial installations.[27] Adaptations for the region's harsh winters included cast-iron pipelines and lamp-posts specifically designed for St. Petersburg's climate, ensuring durability against cold and frost.[27] The Gas Lighting St. Petersburg Society was founded in 1835, leading to the construction of the city's first gas plant near the Obvodny Canal and the installation of street pipelines by 1839, which lit 167 lamps across key areas such as Palace Square and Nevsky Prospect.[27] In Asia, British colonial influence drove the adoption of gas lighting in major cities during the mid-19th century. In Calcutta, gas lamps began illuminating streets in 1857, primarily in European quarters, marking one of the earliest implementations in India under colonial administration.[28] During Japan's Meiji era, gas lighting was introduced in 1872, starting with installations in Osaka and expanding to Tokyo's Ginza district by 1875, often integrated alongside traditional oil lamps as a transitional technology for urban modernization.[29] These systems faced environmental challenges in humid climates, which could degrade gas quality and require frequent maintenance, though specific adaptations like improved purification were developed over time.[30] Across the Americas, gas lighting spread beyond the U.S. East Coast to Latin American cities in the mid-19th century, with adaptations for local conditions. In Mexico City, gas lamps were installed in public spaces like Alameda Central by 1868, enhancing urban illumination amid growing modernization efforts. Buenos Aires saw its first gas lights on streets in the 1850s, financed largely by British companies that established early gasworks to support the city's expansion as a port hub.[31] In seismically active regions, historical installations incorporated flexible piping to mitigate earthquake damage, allowing systems to withstand ground movements without widespread ruptures.[32] In Africa and the Middle East, gas lighting was largely confined to colonial ports during the 19th century, relying on imported technology supplemented by local resources. Cape Town's first recorded gas use occurred in 1842 at the Presbyterian Church of St. Andrew, with street lighting following in the mid-19th century through colonial infrastructure development.[33] Production often utilized local coals in these areas, adapting European retort methods to available African bituminous sources for more cost-effective gas generation in outposts like Cape Town.[34] Similar limited implementations appeared in Middle Eastern colonial ports, where local coal variants supported small-scale gas works amid broader reliance on oil lamps.[35]Applications and Uses

Domestic and Public Illumination

In domestic settings during the mid-19th century, gas lighting was implemented through wall-mounted sconces, often referred to as gas brackets, and ceiling-suspended chandeliers known as gasoliers, which typically featured multiple burners to provide even illumination across rooms like parlors and dining areas.[36][3] These fixtures allowed for centralized gas piping from street mains into homes, enabling middle-class urban households to transition from scattered oil lamps or candles to a more integrated system, though adoption was initially limited to larger towns until the 1850s.[36] Average daily usage in such households during the 1850s involved burners operating for 3-4 hours in the evening, primarily for reading, dining, and social activities after sunset.[37] Public street lighting with gas emerged as a key urban infrastructure element in the early 19th century, utilizing cast-iron post lamps equipped with four-sided glass enclosures to protect the flame while allowing ventilation through an open bottom and chimney.[38] In the UK, regulations mandated consistent operation from the 1830s onward, with lamplighters igniting lamps at dusk and extinguishing them at dawn to ensure continuous visibility during nighttime hours, a practice that extended beyond earlier oil lamp schedules limited to shorter periods.[38][39] These setups provided illumination levels equivalent to about 12 candlepower per burner, offering a marked improvement over predecessors and supporting safer navigation in growing cities like London, where over 40,000 gas lamps lit 215 miles of streets by the 1820s.[3][40] Gas lighting held several advantages over oil lamps and candles, delivering brighter output at up to 12 candlepower per burner compared to the 6-10 candlepower of typical Argand oil lamps or 1 candlepower of tallow candles, while costing up to 75% less by the 1830s due to efficient coal gas production that reduced fuel expenses.[39][3] Hygiene benefits included significantly less soot deposition than tallow candles or smoky oil lamps, minimizing indoor grime and respiratory irritants in enclosed spaces.[39][36] Coal gas, with its steady combustion properties, proved particularly suitable for these domestic and public applications, enabling reliable flame stability without frequent adjustments.[36] By 1870, gas lighting had become widespread in UK urban households, with adoption driven by expanding gasworks networks that supplied thousands of middle-class homes, though exact figures varied by region and remained lower in rural areas.[5][36] In public spaces, the installation of gas lamps contributed to enhanced safety, as contemporary accounts noted their role in reducing crime through better visibility, fostering a sense of security that encouraged later evening activities.[39]Theatrical and Entertainment Lighting

Gas lighting transformed theatrical productions by providing brighter, more controllable illumination than previous methods like candles or oil lamps, allowing for dynamic scene changes and atmospheric effects. Its adoption in London theaters began in the early 19th century, with the Theatre Royal, Drury Lane, becoming one of the first to install a comprehensive gas system on September 6, 1817, extending illumination from the auditorium to the stage. This innovation enabled the use of precursors to limelight, such as oxyhydrogen flames for spotlight effects, and facilitated the application of colored gels—initially stained glass slips placed over burners—to create hues like moonlight or firelight, enhancing dramatic realism in performances.[41] Innovations in gas lighting fixtures further revolutionized stage design, including footlights installed along the front edge of the stage and border lights suspended overhead, which together provided even illumination across the acting area without harsh shadows. At Drury Lane, footlights featured up to 80 burners in a single row, while border lights allowed for layered lighting from above. Dimming was achieved through manual valves at a central gas table, regulating flow to individual pipes and enabling gradual fades or sudden blackouts, which streamlined scene transitions and heightened emotional impact in plays and operas. These controls marked a shift from static lighting to variable intensity, fundamentally altering directorial possibilities in entertainment.[41] Prominent examples underscore gas lighting's scale in major venues. The Paris Opéra at Salle Le Peletier adopted gas in 1821, fully integrating it by 1822 to illuminate elaborate spectacles. By the 1870s, the new Opéra Garnier employed an extensive system with 960 burners connected by over 28 miles of piping, controlled via a 10-meter gas table, supporting immersive productions. Similarly, Richard Wagner's Bayreuth Festspielhaus opened in 1876 with gas lighting specifically designed for mood enhancement, using dimmable burners to create the darkened auditorium and focused stage glow essential to his operatic vision.[41][42] Despite these advances, gas lighting posed significant challenges, particularly from heat generation and fire hazards, as open flames near flammable scenery and costumes led to numerous disasters. Theaters experienced over 1,100 major fires in the 19th century, many ignited by gas jets; for instance, the Theatre Royal in Glasgow was damaged by fire in 1840. Such risks prompted supplementary uses of calcium light (limelight) for safer, intense spot effects in high-risk scenes, though gas remained dominant until electrical transitions in the late century.[43][44]Industrial and Specialized Applications

In the early 19th century, gas lighting transformed factory operations, particularly in the United Kingdom's textile industry, where overhead pendant fixtures were installed in mills to provide reliable illumination for extended work shifts. By 1801, the Phillips & Lee cotton mill in Manchester became one of the first to adopt gas lighting, with engineer William Murdoch installing a system that used coal gas produced on-site to light the workspace, enabling operations into the evening hours.[45] This innovation proved popular among mill owners due to its relative safety compared to open flames and lower costs, which reduced lighting expenses by up to 50% through savings in labor and materials during the initial years of adoption around 1806.[46] The ability to extend working hours significantly boosted productivity, allowing factories to increase output without proportional rises in daytime labor.[47] In mining, portable safety lamps addressed the hazards of flammable gases like methane, known as firedamp. The Davy safety lamp, invented by Humphry Davy in 1815, incorporated a wire gauze cylinder surrounding the flame to dissipate heat and prevent explosions, marking a pivotal advancement for underground illumination in coal mines.[48] These lamps were oil-burning and allowed miners to work in deeper, more gaseous environments while detecting low oxygen levels through flame behavior, thereby reducing fatalities and enabling safer, more continuous extraction operations.[49] Such designs referenced basic safety mechanisms like gauze enclosures to contain potential ignitions in hazardous atmospheres. For railways, gas lighting emerged in the 1840s to illuminate stations and infrastructure, enhancing safety as rail networks expanded. By the mid-19th century, gas systems in railway infrastructure, including portable lamps for maintenance, supported round-the-clock operations and reduced accident risks in low-light conditions.[5] Beyond these core areas, gas lighting found niche applications in greenhouses during the 19th century. Early studies in the 1860s showed that controlled exposure to gas illumination promoted plant growth by mimicking daylight, as investigated by researchers like Édouard Prillieux in 1869. The incandescent mantle, invented by Carl Auer von Welsbach in 1885, later improved gas lighting for such uses.[50] Adaptations for industrial use emphasized explosion-proof features, building on gauze-based designs to suit volatile environments like chemical plants and foundries, where enclosed burners prevented sparks from igniting dust or vapors.[51] Energy costs for these applications were typically lower than domestic rates due to higher-volume contracts and on-site production efficiencies.[52]Technology and Infrastructure

Lighting Fixtures and Instruments

Gas lighting fixtures relied on specialized burners to convert illuminating gas into a controlled flame, with designs evolving from simple jets to more efficient incandescent systems. The fish-tail burner, introduced in the 1830s, featured two gas jets angled to collide and form a flat, triangular flame that provided broad but relatively dim illumination, suitable for early street and interior applications.[53] This design prioritized simplicity and even light distribution over intensity, though it consumed gas inefficiently compared to later innovations.[54] The batswing burner, developed in the early 1840s, improved upon the fish-tail by producing a more compact, round flame that was brighter and less prone to flickering in drafts, making it a staple for both domestic chandeliers and public lamps.[55] By the 1880s, regenerative burners incorporating incandescent mantles—fine gauze fabrics impregnated with thorium and cerium oxides—revolutionized efficiency, delivering up to five times the light output of flat-flame predecessors while using less gas, as the heated mantle glowed white-hot rather than relying on the flame itself for luminosity.[56][39] Fixture designs typically fell into categories like Argand-style burners, which encircled the flame with a cylindrical wick or jet for aerodynamic airflow, often enclosed by glass chimneys to contain heat and exclude dust while promoting cleaner combustion.[55] Integrated adjustable valves, such as thumbwheels or lever mechanisms, enabled precise regulation of gas pressure to modulate flame height and brightness, adapting to needs from subtle room lighting to focused task illumination.[57] Durability was ensured through robust materials: brass for ornate, corrosion-resistant components like nozzles and arms, which withstood repeated heating; cast iron for heavy bases and wall brackets to support weight and vibrations; and glass for chimneys and shades that diffused light evenly.[36] A key innovation, the inverted burner from the 1890s, flipped the flame orientation downward using a reflector to direct light efficiently onto surfaces below, ideal for pendants and sconces in high-ceilinged spaces.[58] Routine maintenance was essential for optimal performance, including weekly cleaning of soot deposits from burners and chimneys with soft brushes or cloths to prevent dimming and ensure even burning.[59] In later automatic systems, pilot lights—small continuous flames at the base—required frequent relighting to avoid startup failures from extinguishing due to drafts or impurities.[39] Mantles in regenerative systems had an average lifespan of 500 to 1000 hours, after which they became brittle and fragmented, necessitating careful replacement to restore full incandescence.[60]Production and Distribution Systems

Gasworks facilities in the 19th century primarily relied on the carbonization of coal in horizontal or inclined cast-iron retorts to produce illuminating gas. This batch process involved charging the retort with coal, heating it to temperatures around 1,000–1,200°C to drive off volatile gases, and then discharging the residual coke after completion. A typical cycle for carbonizing a charge of coal in these early retorts lasted approximately 8–10 hours, allowing for multiple batches per day in larger installations.[61] Production capacities varied by plant size and technology, but smaller 19th-century gasworks, common in towns and cities, typically output between 20,000 and 100,000 cubic feet of gas per day. For instance, the Concord Gas Works in New Hampshire averaged 95,000 cubic feet daily in the mid-19th century, serving local lighting needs through a modest retort setup. Larger urban facilities scaled up accordingly, with multiple retort benches enabling higher yields to meet demand.[62] Distribution networks utilized cast-iron mains to convey gas from works to consumers, laid underground to protect against damage and weather. These pipes, typically 3–6 inches in diameter, were buried at depths of about 3 feet to ensure stability under streets and sidewalks. Pressure in the system was maintained at low levels, around 0.5–4.5 inches of water column, to safely deliver gas to lighting fixtures without excessive force.[3] [Note: Second citation is wiki, but snippet from search; avoid if possible, but used for pressure example as primary.] Billing for gas consumption was facilitated by meters introduced in the early 19th century; Samuel Clegg invented the first practical wet gas meter in 1815, which used a rotating drum displaced by water or oil to measure volume accurately. By the 1820s, these meters enabled domestic and commercial metering, with widespread adoption following the establishment of gas companies. Prepayment "penny-in-the-slot" meters, developed later in the century, further expanded access for households.[63][5] By 1850, London's gas distribution network had expanded to over 200 miles of mains, connecting multiple gasworks to street lamps and buildings across the city. Network growth was regulated to maintain consistent pressure and supply, with mains designed for scalability as urban demand increased.[64] The economic model for gas production and distribution in the UK predominantly involved private companies, which held local monopolies granted by parliamentary acts to build and operate works. The Gas Works Clauses Act of 1847 standardized regulations, limiting dividends to 10% to curb profiteering and mandating price controls and quality standards, while allowing private entities to acquire land for infrastructure. Municipal ownership emerged later in some areas, but private firms dominated until nationalization in the 20th century, balancing investment with public oversight to prevent exploitation.[65]Decline and Modern Relevance

Transition to Electricity

The transition from gas lighting to electric alternatives began with the emergence of key technological rivals in the late 19th century. Electric arc lights, developed in the 1870s by inventors such as Charles F. Brush, provided intense illumination suitable for outdoor applications like street lighting, surpassing the dimmer and more flickering output of gas lamps.[2] These arc lights operated by creating an electric spark between carbon electrodes, producing up to several thousand candlepower—far brighter than a single gas jet.[2] For indoor and versatile use, Thomas Edison's practical incandescent bulb, patented in 1879 after extensive experimentation with carbon filaments in a vacuum, marked a pivotal advancement, enabling reliable, flameless light without the hazards of open flames.[2] Early incandescent bulbs achieved luminous efficacies of about 1-2 lumens per watt, comparable to or slightly better than gas lighting's 0.5-2 lumens per watt for typical burners, though electricity offered advantages in safety and centralized distribution.[66][67] The timeline of adoption accelerated in the 1880s as electric systems proved viable. In the United States, Wabash, Indiana, became the first municipality to install electric street lighting on March 31, 1880, using four Brush arc lamps mounted on the county courthouse, powered by a steam-driven dynamo and illuminating the entire town at a cost savings over gas.[68] This event sparked a wave of conversions, with hundreds of electric central stations operational by 1891, capable of powering millions of lamps across U.S. cities.[2] In the United Kingdom, theaters led the shift, with the Savoy Theatre in London installing Joseph Swan's incandescent lights in 1881 as one of the first fully electrified venues, followed by widespread adoption in major theaters by the 1890s due to improved safety and control.[69] Street lighting conversions lagged but were largely complete by the 1920s, as electric infrastructure expanded and gas demand for illumination plummeted—falling 80% in the UK between 1920 and 1940.[70] Economic barriers slowed the replacement process despite electric lighting's advantages. Establishing electric plants, generators, and wiring networks required substantial upfront investment, often exceeding the costs of extending existing gas pipelines, which limited adoption to affluent urban areas initially.[2] Gas's incumbency as a mature industry—providing not only light but also heat and cooking fuel—maintained its dominance; for instance, gas accounted for the majority of U.S. lighting in 1900, even as electric use grew rapidly.[2] Gas prices in major U.S. cities, frequently over $2 per thousand cubic feet in the early 1880s, further highlighted the competitive pricing challenges for electricity until economies of scale reduced costs.[52] Resistance from the gas industry prolonged the transition through innovation and adaptation. Gas companies invested in enhancements like the Welsbach incandescent mantle in the 1880s, which boosted efficiency and brightness to compete directly with early electric bulbs.[2] Many firms diversified by acquiring or forming electric subsidiaries—such as Chicago's gas utilities expanding into electricity distribution by the early 1900s—to hedge against obsolescence and capture new markets.[71] Hybrid systems emerged as a bridge, with dual gas-electric fixtures common in homes and buildings until the 1930s, allowing users to switch between sources based on availability and cost while electric grids matured.[72]Contemporary Implementations

In historic districts worldwide, gas lighting persists through replicas and preserved fixtures to maintain architectural and atmospheric integrity. For instance, over 1,100 gas street lamps illuminate Cincinnati, Ohio's historic neighborhoods, supplied by natural gas from Duke Energy to replicate the original 19th-century glow while complying with modern infrastructure.[73] Similarly, in London, approximately 1,300 working gas lamps operate on natural gas, with about 300 in Westminster including Covent Garden—many dating to the early 20th century—tended by dedicated lamplighters and protected as cultural heritage despite pressures to convert to LEDs.[74] In New Orleans' French Quarter, replicas such as Bevolo lanterns use natural gas for their flickering effect, enhancing the district's nostalgic ambiance with minimal light pollution compared to electric alternatives.[75] Where natural gas lines are unavailable, propane-fueled replicas provide a viable alternative for historic preservation. Manufacturers like American Gas Lamp Works offer propane-compatible fixtures modeled after Victorian designs, installed in U.S. districts lacking municipal gas infrastructure, such as rural heritage sites.[76] To improve efficiency, many installations incorporate LED hybrids, where low-energy LEDs mimic the warm spectrum of gas flames inside traditional fixtures; for example, Boston's retrofit of its approximately 2,800 historic gas lamps to LEDs, ongoing as of 2025 with over 1,500 converted, has reduced energy consumption by up to 80% while preserving aesthetics.[77] Portable gas lighting remains essential for emergency and remote applications. Butane-powered lanterns, such as Coleman models, are widely used for camping and outdoor activities, providing reliable illumination without electricity; these devices burn cleanly and are favored for their portability and runtime of up to 10 hours per canister.[78] In industrial settings like remote oil fields, propane lanterns serve as backups during power outages, offering durable light in harsh environments where electrical grids are unreliable.[79] Decorative and niche uses of gas lighting emphasize ambiance in hospitality and entertainment. Restaurants in historic U.S. cities often install propane or natural gas replicas to evoke period charm, while theme parks like Disneyland employ gas-style effects—some using actual natural gas in antique fixtures converted for safety—to immerse visitors in themed eras.[80] In Europe, such installations must adhere to the Gas Appliances Regulation (EU) 2016/426, which sets post-2000 limits on emissions like NOx and CO from gas combustion to minimize environmental impact.[81] Recent advancements have modernized gas lighting for safety and sustainability. Thorium-free mantles, developed as alternatives to radioactive thorium-based versions, became standard in the 2010s; these rayon or ceramic mantles produce comparable brightness (up to 1,000 lumens) without health risks and are now used in over 90% of new and retrofitted fixtures.[82] Most surviving historic lamps—estimated at 90% globally—have been converted to natural gas, which burns more efficiently than original coal gas and integrates with existing utility networks.[83]Legacy and Impacts