Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Historically black colleges and universities

View on Wikipedia

| Part of a series on |

| African Americans |

|---|

Historically Black colleges and universities (HBCUs) are institutions of higher education in the United States that were established before the Civil Rights Act of 1964 with the intention of serving African American students.[1] Most are in the Southern United States and were founded during the Reconstruction era (1865–1877) following the American Civil War.[2] Their original purpose was to provide education for African Americans in an era when most colleges and universities in the United States did not allow Black students to enroll.[3][4]

During the Reconstruction era, most historically Black colleges were founded by Protestant religious organizations. This changed in 1890 with the U.S. Congress' passage of the Second Morrill Act, which required segregated Southern states to provide African Americans with public higher education schools in order to receive the Act's benefits. Separately, during the latter 20th century, either after expanding their inclusion of Black people and African Americans into their institutions or gaining the status of minority-serving institution, some institutions came to be called predominantly Black institutions (PBIs).[5]

For a century after the abolition of American slavery in 1865, almost all colleges and universities in the Southern United States prohibited all African Americans from attending as required by Jim Crow laws in the South, while institutions in other parts of the country regularly employed quotas to limit admission of Black people.[6][7][8][9] HBCUs were established to provide more opportunities to African Americans and are largely responsible for establishing and expanding the African-American middle class.[10][11] In the 1950s and 1960s, legally enforced racial segregation in education was generally outlawed throughout the South (and anywhere else in the United States), and other non-discrimination policies were adopted.

There are 101 HBCUs[needs update] in the United States (of 121 institutions that existed during the 1930s),[12] representing three percent (3%) of the nation's colleges,[13] including public and private institutions.[14] 27 offer doctoral programs, 52 offer master's programs, 83 offer bachelor's degree programs, and 38 offer associate degrees.[15][16][17] HBCUs currently produce nearly 20% of all African American college graduates and 25% of African American STEM graduates.[18] Among the graduates of HBCUs are civil rights leader Martin Luther King Jr., United States Supreme Court justice Thurgood Marshall, American film director Spike Lee, former United States vice president Kamala Harris and the late American mathematician Katherine Johnson.

History

[edit]

Private institutions

[edit]HBCUs established prior to the American Civil War include Cheyney University of Pennsylvania in 1837,[19] University of the District of Columbia (then known as Miner School for Colored Girls) in 1851, and Lincoln University in 1854.[20] Wilberforce University was also established prior to the American Civil War.[21] The university was founded in 1856 via a collaboration between the African Methodist Episcopal Church of Ohio and the predominantly white Methodist Episcopal Church.[22]

HBCUs were controversial in their early years. At the 1847 National Convention of Colored People and Their Friends, the famed Black orators Frederick Douglass, Henry Highland Garnet, and Alexander Crummell debated the need for such institutions, with Crummell arguing that HBCUs were necessary to provide freedom from discrimination, and Douglass and Garnet arguing that self-segregation would harm the black community. A majority of the convention voted that HBCUs should be supported.[23][24]

Most HBCUs were established in the South after the American Civil War, often with the assistance of religious missionary organizations based in the North, especially the American Missionary Association. The Freedmen's Bureau played a major role in financing the new schools.[25][26]

Atlanta University – now Clark Atlanta University – was founded on September 19, 1865, as the first HBCU in the Southern United States. Atlanta University was the first graduate institution (sometimes shortened to grad school)[27] to award degrees to African Americans in the nation and the first to award bachelor's degrees to African Americans in the South; Clark College (1869) was the nation's first four-year liberal arts college to serve African-American students. The two consolidated in 1988 to form Clark Atlanta University.[28] Shaw University, founded December 1, 1865, was the second HBCU to be established in the South. The year 1865 also saw the foundation of Storer College (1865–1955) in Harper's Ferry, West Virginia.[2] Storer's former campus and buildings have since been incorporated into Harpers Ferry National Historical Park.[29]

Some of these universities eventually became public universities with assistance from the government.[30]

Public institutions

[edit]In 1862,[31] the federal government's Morrill Act provided for land grant colleges in each state. Educational institutions established under the Morrill Act in the North and West were open to Black Americans. But 17 states, almost all in the South, required their post-Civil war systems to be segregated and excluded Black students from their land grant colleges. In the 1870s, Mississippi, Virginia, and South Carolina each assigned one African American college land-grant status: Alcorn University, Hampton Institute, and Claflin University, respectively.[32] In response, Congress passed the second Morrill Act of 1890, also known as the Agricultural College Act of 1890, requiring states to establish a separate land grant college for Black students if they were being excluded from the existing land grant college. Many of the HBCUs were founded by states to satisfy the Second Morrill Act.[33] These land grant schools continue to receive annual federal funding for their research, extension, and outreach activities.[17]

Predominantly Black institutions

[edit]Predominantly Black colleges and universities (PBCUs) are those institutions with a 50% or greater enrollment of African American students. These colleges are not to be confused with historically Black colleges and universities (HBCUs). Like HBCUs, PBCUs serve large numbers of African American students. Whereas HBCUs refer to institutions of higher learning founded to educate the descendants of formerly enslaved Africans prior to 1964, PBCUs were not necessarily founded with a mission of educating African Americans.[34]

Sports

[edit]In the 1920s and 1930s, historically Black colleges developed a strong interest in athletics. Sports were expanding rapidly at state universities, but very few Black stars were recruited there. Race newspapers hailed athletic success as a demonstration of racial progress. Black schools hired coaches, recruited and featured stellar athletes, and set up their own leagues.[35][36]

Jewish refugees

[edit]In the 1930s, many Jewish intellectuals fleeing Europe after the rise of Hitler and anti-Jewish legislation in prewar Nazi Germany following Hitler's elevation to power emigrated to the United States and found work teaching in historically Black colleges.[37] In particular, 1933 was a challenging year for many Jewish academics who tried to escape increasingly oppressive Nazi policies,[38] particularly after legislation was passed stripping them of their positions at universities.[38] Jews looking outside of Germany could not find work in other European countries because of calamities like the Spanish Civil War and general antisemitism in Europe.[39][38] In the US, they hoped to continue their academic careers, but barring a scant few, found little acceptance in elite institutions in Depression-era America, which also had their own undercurrent of antisemitism.[37][40]

As a result of these phenomena, more than two-thirds of the faculty hired at many HBCUs from 1933 to 1945 had come to the United States to escape from Nazi Germany.[41] HBCUs believed the Jewish professors were valuable faculty that would help strengthen their institutions' credibility.[42] HBCUs had a firm belief in diversity and giving opportunity no matter the race, religion, or country of origin.[43] HBCUs were open to Jews because of their ideas of equal learning spaces. They sought to create an environment where all people felt welcome to study, including women.[43]

World War II

[edit]HBCUs made substantial contributions to the US war effort. One example is Tuskegee University in Alabama, where the Tuskegee Airmen trained and attended classes.[44][45]

Florida's Black junior colleges

[edit]After the landmark Brown v. Board of Education decision of 1954, the legislature of Florida, with support from various counties, opened eleven junior colleges serving the African American population. Their purpose was to show that separate but equal education was working in Florida. Prior to this, there had been only one junior college in Florida serving African Americans, Booker T. Washington Junior College, in Pensacola, founded in 1949. The new ones were Gibbs Junior College (1957), Roosevelt Junior College (1958), Volusia County Junior College (1958), Hampton Junior College (1958), Rosenwald Junior College (1958), Suwannee River Junior College (1959), Carver Junior College (1960), Collier-Blocker Junior College (1960), Lincoln Junior College (1960), Jackson Junior College (1961), and Johnson Junior College (1962).

The new junior colleges began as extensions of Black high schools. They used the same facilities and often the same faculty. Some built their own buildings after a few years. After the passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 mandated an end to school segregation, the colleges were all abruptly closed. Only a fraction of the students and faculty were able to transfer to the previously all-white junior colleges, where they found, at best, an indifferent reception.[46]

Since 1965

[edit]

A reauthorization of the Higher Education Act of 1965 established a program for direct federal grants to HBCUs, to support their academic, financial, and administrative capabilities.[47][48] Part B specifically provides for formula-based grants, calculated based on each institution's Pell grant eligible enrollment, graduation rate, and percentage of graduates who continue post-baccalaureate education in fields where African Americans are underrepresented. Some colleges with a predominantly Black student body are not classified as HBCUs because they were founded (or opened their doors to African Americans) after the implementation of the Sweatt v. Painter (1950) and Brown v. Board of Education (1954) rulings by the U.S. Supreme Court (the court decisions which outlawed racial segregation of public education facilities) and the Higher Education Act of 1965.

In 1980, Jimmy Carter signed an executive order to distribute adequate resources and funds to strengthen the nation's public and private HBCUs. His executive order created the White House Initiative on historically Black colleges and universities (WHIHBCU), which is a federally funded program that operates within the U.S. Department of Education.[49] In 1989, George H. W. Bush continued Carter's pioneering spirit by signing Executive Order 12677, which created the presidential advisory board on HBCUs, to counsel the government and the secretary on the future development of these organizations.[50]

Starting in 2001, directors of libraries of several HBCUs began discussions about ways to pool their resources and work collaboratively. In 2003, this partnership was formalized as the HBCU Library Alliance, "a consortium that supports the collaboration of information professionals dedicated to providing an array of resources designed to strengthen historically Black colleges and Universities and their constituents."[51]

In 2015, the Bipartisan Congressional Historically Black Colleges and Universities (HBCU) Caucus was established by U.S. Representatives Alma S. Adams and Bradley Byrne. The caucus advocates for HBCUs on Capitol Hill.[52] As of May 2022[update], there are over 100 elected politicians who are members of the caucus.[53]

Current status

[edit]

Each year, the U.S. Department of Education designates a week in the fall as "National HBCU Week." This week features conferences and events focused on discussing and celebrating HBCUs while also honoring notable scholars and alumni from these institutions.[54]

As of February 2025, Alabama has the most active HBCUs of any state, with 14.[55] North Carolina is second with 11.[56]

In February 2025, Howard University became the first HBCU to achieve Research One (R1) Carnegie Classification.[57]

In 2024, some HBCUs experienced a significant increase in applications and enrollment, largely driven by the Supreme Court's landmark decision in June 2023 to end race-based affirmative action at American colleges and universities.[58][59]

A 2024 study by the American Institute for Boys and Men revealed that Black men make up only 26% of HBCU students, down from 38% in 1976. The decline of Black men enrolled in college is also noticeable at non-HBCUs.[60]

In 2024, the United Negro College Fund released a study showing that HBCUs had a $16.5 billion positive impact on the nation's economy.[61]

In 2023, the average HBCU 6-year undergraduate graduation rate was 35% while the national average was 64%. Spelman College was the only HBCU above the national average at 74%.[62] Also in 2023, 73% of students attending HBCUs were Pell Grant eligible while the national average was 34%.[62][63] Talladega College had the highest percent of Pell Grant eligible students among HBCUs at 95%.[64]

Between 2020 and 2021, philanthropist MacKenzie Scott donated a historic $560 million in total to 23 public and private HBCUs, with most of her contributions setting donation records at the institutions she supported.[65]

In 2015, the share of Black students attending HBCUs had dropped to 9% of the total number of Black students enrolled in degree-granting institutions nationwide. This figure is a decline from the 13% of Black students who enrolled in an HBCU in 2000 and 17% who enrolled in 1980. This is a result of desegregation, rising incomes and increased access to financial aid, which has created more college options for Black students.[14][66]

The percentages of bachelor's and master's degrees awarded to Black students by HBCUs has decreased over time. HBCUs awarded 35% of the bachelor's degrees and 21% of the master's degrees earned by Black students in 1976–77, compared with the 14% and 6% respectively of bachelor's and master's degrees earned by Black students in 2014–15. Additionally, the percentage of Black doctoral degree recipients who received their degrees from HBCUs was lower in 2014–15 (12%) than in 1976–77 (14%).[67][68][69]

The number of total students enrolled at an HBCU rose by 32% between 1976 and 2015, from 223,000 to 293,000. Total enrollment in degree-granting institutions nationwide increased by 81%, from 11 million to 20 million, in the same period.[67]

Although HBCUs were originally founded to educate Black students, their diversity has increased over time. In 2015, students who were either White, Hispanic, Asian or Pacific Islander, or Native American made up 22% of total enrollment at HBCUs, compared with 15% in 1976.[70]

HBCUS may struggle to complete with predominantly White schools in recruiting high-achieving Black students. In an attempt to correct for racial disparities, many predominantly White institutions actively seek out and court high-achieving students of color. These schools may extend scholarships or other incentives to prospective students beyond what HBCUs can offer.[71]

Racial diversity post-2000

[edit]Following the enactment of Civil Rights laws in the 1960s, many educational institutions in the United States that receive federal funding adopted affirmative action to increase their racial diversity. Some historically Black colleges and universities now have non-Black majorities, including West Virginia State University and Bluefield State University, whose student bodies have had large White majorities since the mid-1960s.[14][72][73]

As many HBCUs have made a concerted effort to maintain enrollment levels and often offer relatively affordable tuition, the percentage of non–African-American enrollment has risen.[74][75][76][77] The following table highlights HBCUs with high non–African American enrollments:

| College name | State | Percentage | |

|---|---|---|---|

| African American |

Non-African American | ||

| Bluefield State University[79] | West Virginia | 8 | 92 |

| West Virginia State University[80] | West Virginia | 8 | 92 |

| Kentucky State University[81] | Kentucky | 46 | 54 |

| University of the District of Columbia[82] | District of Columbia | 59 | 41 |

| Delaware State University[83] | Delaware | 64 | 36 |

| Fayetteville State University[84] | North Carolina | 60 | 40 |

| Winston-Salem State University[85] | North Carolina | 71 | 29 |

| Elizabeth City State University[86] | North Carolina | 76 | 24 |

| Xavier University of Louisiana[87] | Louisiana | 70 | 30 |

| North Carolina A&T State University[88] | North Carolina | 80 | 20 |

| Lincoln University (Pennsylvania)[89] | Pennsylvania | 84 | 16 |

Other HBCUs with relatively high non–African American student populations

According to the U.S. News & World Report Best Colleges 2011 edition, the proportion of White American students at Langston University was 12%; at Shaw University, 12%; at Tennessee State University, 12%; at the University of Maryland Eastern Shore, 12%; and at North Carolina Central University, 10%. The U.S. News & World Report's statistical profiles indicate that several other HBCUs have relatively significant percentages of non–African American student populations consisting of Asian, Hispanic, white American, and foreign students.[90]

Special academic programs

[edit]HBCU libraries have formed the HBCU Library Alliance. Together with Cornell University, the alliance has a joint program to digitize HBCU collections. The project is funded by the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation.[91] Additionally, more historically Black colleges and universities are offering online education programs. As of November 23, 2010, nineteen historically Black colleges and universities offer online degree programs.[92]

Intercollegiate sports

[edit]NCAA Division I has two historically Black athletic conferences: Mid-Eastern Athletic Conference and Southwestern Athletic Conference. The top football teams from the conferences have played each other in postseason bowl games: the Pelican Bowl (1970s), the Heritage Bowl (1990s), and the Celebration Bowl (2015–present). These conferences are home to all Division I HBCUs except for Hampton University and Tennessee State University. Tennessee State has been a member of the Ohio Valley Conference since 1986, while Hampton left the MEAC in 2018 for the Big South Conference. In 2021, North Carolina A&T State University made the same conference move that Hampton made three years earlier (MEAC to Big South).[93] Both Hampton and North Carolina A&T later moved their athletic programs to the Colonial Athletic Association and its technically separate football league of CAA Football; Hampton joined both sides of the CAA in 2022,[94] while A&T joined the all-sports CAA in 2022 before joining CAA Football in 2023.[95]

The mostly HBCU Central Intercollegiate Athletic Association and Southern Intercollegiate Athletic Conference are part of the NCAA Division II, whereas the HBCU Gulf Coast Athletic Conference is part of the National Association of Intercollegiate Athletics.[96]

Notable HBCU alumni

[edit]This section contains an excessive or unencyclopedic gallery of images. (January 2025) |

HBCUs have a rich legacy of matriculating many leaders in the fields of business, law, science, education, military service, entertainment, art, and sports.

- Ralph Abernathy, civil rights activist, minister – Clark Atlanta University, Alabama State University

- Ed Bradley, first black White House correspondent for CBS News – Cheyney University of Pennsylvania

- Toni Braxton, Grammy-winning R&B artist with over 70 million records sold – Bowie State

- Edward Brooke, first African-American elected by popular vote to United States Senate and to serve as Massachusetts Attorney General – Howard University

- Roscoe Lee Browne, prolific actor and director – Lincoln University

- Stokely Carmichael, political organizer, Black Power theorist and Pan-Africanist activist – Howard University

- James Clyburn, US Congressman from South Carolina's 6th congressional district and Majority Whip of the 116th United States Congress – South Carolina State University

- Medgar Wiley Evers, civil rights leader – Alcorn State University

- NASA mathematician Katherine Johnson attended West Virginia State University.

- Althea Gibson, the first African American to win a Grand Slam title had a full athletic scholarship to Florida A&M University

- Nikki Giovanni, poet – Fisk University

- Alcee Hastings, US Congressman from Florida's 20th congressional district – Fisk University, Howard University, Florida A&M University

- Randy Jackson, original judge on American Idol – Southern University

- Lonnie Johnson, inventor, NASA engineer – Tuskegee University

- Tom Joyner, first African-American inducted into the National Radio Hall of Fame – Tuskegee University

- Reginald Lewis, first African-American to build and own a billion dollar company – Virginia State

- Claude McKay, poet, Tuskegee University

- Astronaut Ronald McNair graduated from North Carolina A&T State University.

- Rod Paige, first African-American to serve as the U.S. education chief – Jackson State University

- Walter Payton, considered one of the greatest running backs in NFL history – Jackson State University

- Anika Noni Rose, the original voice of the first African American Disney princess (Tiana) – Florida A&M University

- Jerry Rice, considered the greatest NFL wide receiver of all-time – Mississippi Valley State

- Stephen A. Smith, well-known sports journalist and television personality – Winston-Salem State University

- Megan Thee Stallion, Grammy-winning rapper and actress – Texas Southern

- Leon H. Sullivan, developer of the Sullivan Principles used to end apartheid in South Africa, attended West Virginia State University.

- Wanda Sykes, Emmy-winning comedian, novelist, writer, and actress – Hampton University

- André Leon Talley, first African-American editor-at-large of Vogue – Virginia State

- The Tuskegee Airmen were educated at Tuskegee University.

- Alice Walker, novelist and poet – Spelman College

- Ben Wallace, former 4-time NBA All-Star and NBA Defensive Player of the Year – Virginia Union University

- Doug Williams, first black NFL quarterback to win a Super Bowl – Grambling State

- Tramell Tillman, actor – Xavier University of Louisiana

-

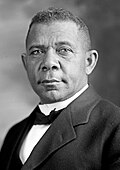

Booker T. Washington, educator, orator, and advisor (Hampton)

-

Toni Morrison, acclaimed novelist and Nobel laureate (Howard)

-

Jesse Jackson, minister and politician (North Carolina A&T)

-

Samuel L. Jackson, actor and film producer (Morehouse)

-

Oprah Winfrey, talk show host and media mogul (Tenn State)

-

Kamala Harris, Vice President of the United States (Howard)

-

Taraji P. Henson, actress (Howard)

-

Chadwick Boseman, actor and playwright (Howard)

-

Common, rapper and actor (Florida A&M)

-

Erykah Badu, singer, entrepreneur, and actress (Grambling State)

-

Lionel Richie, singer, songwriter, record producer, and TV personality (Tuskegee)

-

Stacey Abrams, voting rights leader, lawyer, and author (Spelman)

Modern presidential and federal support

[edit]Federal funding for HBCUs has notably increased in recent years. Proper federal support of HBCUs has become more of a key issue in modern U.S. presidential elections.[97]

In President Barack Obama's eight years in office, he invested more than $4 billion to HBCUs.[98]

In 2019, President Donald Trump signed a bipartisan bill that permanently invested more than $250 million a year to HBCUs.[99]

In 2021, President Joe Biden's first year in office, he invested a historic $5.8 billion to support HBCUs.[100] In 2022, Biden's administration announced an additional $2.7 billion through his American Rescue Plan.[101]

In 2025, President Donald Trump signed an executive order establishing the White House Initiative to Promote Excellence and Innovation at Historically Black Colleges and Universities (HBCUs). This initiative is housed within the Executive Office of the President and aims to enhance HBCUs' capacity to deliver a high-quality education.[102] In September 2025, Trump granted nearly $500 million in federal support to HBCUs.[103]

HBCU homecomings

[edit]Homecoming is a tradition at almost every American college and university, however homecoming has a more unique meaning at HBCUs. Homecoming plays a significant role in the culture and identity of HBCUs. The level of pageantry and local black community involvement (parade participation, business vendors, etc.) helps make HBCU homecomings more distinctive. Due to higher campus traffic and activity, classes at HBCUs are usually cancelled on Friday and Saturday of homecoming.[104] Millions of alumni, students, celebrity guests, and visitors attend HBCU homecomings every year. In addition to being a highly cherished tradition and festive week, homecomings generate strong revenue for many black owned businesses and HBCUs. Since 2021, the rise in violence at HBCU homecomings—primarily gun-related and most often perpetrated by individuals unaffiliated with HBCUs—has become a significant concern.[105][106][107][108][109]

See also

[edit]- Black Ivy League

- Colleges in the United States

- History of education in the Southern United States

- HBCU band

- HBCU Library Alliance

- Honda Campus All-Star Challenge

- Minority-serving institution

- National Museum of African American History and Culture

- Thurgood Marshall College Fund

- United Negro College Fund

References

[edit]- ^ 20 U.S. Code sec.1061, [1] Archived December 20, 2022, at the Wayback Machinehttps://USCode.house.gov For a compact overview of HBCU history, see Walter R. Allen, Joseph O. Jewell, Kimberly A. Griffin, & De'Sha S. Wolf, Historically Black Colleges and Universities: Honoring the Past, Engaging the Present, Touching the Future, 76 Journal of Negro Education, pp. 263–280 (2007).

- ^ a b Anderson, J.D. (1988). The Education of Blacks in the South, 1860–1935. University of North Carolina Press.

- ^ "White House Initiative on Historically Black Colleges and Universities". U.S. Department of Education. April 11, 2008. Archived from the original on October 5, 2015. Retrieved April 23, 2008.

- ^ Wooten, Melissa E. (2016). In the face of inequality. State Univ of New York Press. ISBN 978-1-4384-5690-4. OCLC 946968175.

- ^ Jones, Brandy. "Predominantly Black Institutions: Pathways to Black Student Educational Attainment" (PDF). Center for Minority Serving Institutions.

- ^ Harris, Leslie M. (March 26, 2015). "The Long, Ugly History of Racism at American Universities". The New Republic.

- ^ Marybeth Gasman, Envisioning Black Colleges: A History of the United Negro College Fund (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2007).

- ^ Marybeth Gasman and Felecia Commodore (eds.), Opportunities and Challenges at Historically Black Colleges and Universities (New York: Palgrave Press, 2014). ISBN 978-1-349-50267-7

- ^ Favors, J. (2020). Shelter in a time of storm: How Black colleges fostered generations of leadership and activism. Chapel Hill, North Carolina: The University of North Carolina Press. ISBN 978-1-4696-4833-0

- ^ "The story of historically black colleges in the US". BBC News. February 15, 2019.

- ^ "Despite Obstacles, Black Colleges Are Pipelines to the Middle Class, Study Finds. Here's Its List of the Best". The Chronicle of Higher Education. September 30, 2019. Retrieved February 15, 2022.

- ^ "Required Reading: what is a historically black college?". Student. January 21, 2019. Retrieved June 17, 2025.

- ^ "African Americans and College Education by the Numbers". UNCF. November 29, 2018. Retrieved July 17, 2021.

- ^ a b c "A look at historically black colleges and universities as Howard turns 150". Pewresearch.org. February 28, 2017. Retrieved October 25, 2017.

- ^ "Historically Black Colleges and Universities – American School Search". American-school-search.com. Retrieved October 25, 2017.

- ^ Marybeth Gasman, The Changing Face of Historically Black Colleges and Universities. Philadelphia: Penn Center for Minority Serving Institutions, University of Pennsylvania, 2013. [ISBN missing]

- ^ a b Casey Boland, Marybeth Gasman et al., Contemporary Public HBCUs: A Four State Comparison, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania: Penn Center for Minority Serving Institutions, University of Pennsylvania, Spring 2014. [ISBN missing]

- ^ "The Tide That Binds: Learning from Experience at HBCU's". November 8, 2022.

- ^ For detail of the university's early history from its origins as the Institute for Colored Youth, see Milton M. James, The Institute for Colored Youth, 21 Negro History Bulletin p. 83 (1958)

- ^ Initially chartered as the Ashmun Institute, it changed its name in 1866. It was the first degree-granting HBCU. See Lincoln University, "History". Archived from the original on May 31, 2019. Retrieved August 11, 2022.. See also Andrew E. Murray, The Founding of Lincoln University, 51 Journal of Presbyterian History p. 392 (1973).

- ^ Originally proposed as Ohio African University, the founders changed the name to Wilberforce University, to honor the English abolitionist William Wilberforce, before its corporate charter was granted. Frederick Alphonso McGinnis, A History and Interpretation of Wilberforce University p. 33 (1941). See also Charles Killian, Wilberforce University: The Reality of Bishop Payne's Dream, 34 Negro History Bulletin p. 83 (1971).

- ^ Marybeth Gasman, Envisioning Black Colleges: A History of the United Negro College Fund (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2007).ISBN 978-0-8018-8604-1

- ^ "Proceedings of the National Convention of Colored People and Their Friends; held in Troy, NY; on the 6th, 7th, 8th, and 9th of October, 1847 · Colored Conventions Project Digital Records". omeka.coloredconventions.org. Retrieved June 17, 2025.

- ^ "1847 National Convention of Colored People and Their Friends", Wikipedia, December 7, 2021, retrieved June 17, 2025

- ^ Robert C. Lieberman, "The Freedmen's Bureau and the politics of institutional structure." Social Science History 18.3 (1994): 405–437.

- ^ Ronald E. Butchart, "Freedmen's education during reconstruction." New Georgia Encyclopedia 13 (2016): 4–13 online.

- ^ "Graduate School Definition and Meaning". Top Hat. Retrieved June 17, 2025.

- ^ Carrillo, Karen Juanita (2012). African American History Day By Day – A Reference Guide To Events. Abc-Clio. ISBN 978-1-59884-361-3.

- ^ Roy, Lisa (December 18, 2013). "Storer College (1867–1956)". Retrieved December 4, 2020.

- ^ Ivory A. Toldson (2016). "The Funding Gap between Historically Black Colleges and Universities and Traditionally White Institutions Needs to be Addressed* (Editor's Commentary)". The Journal of Negro Education. 85 (2): 97. doi:10.7709/jnegroeducation.85.2.0097. JSTOR 10.7709/jnegroeducation.85.2.0097.

- ^ (7 U.S.C. § 301 et seq.)

- ^ John W. Davis, The Negro Land-Grant College, 2 Journal of Negro Education p. 312 (1933).

- ^ See generally, John W. Davis, The Negro Land-Grant College, 2 Journal of Negro Education (1933).

- ^ "Historically Black Colleges and Universities (HBCUs)", Encyclopedia of African American Education, 2455 Teller Road, Thousand Oaks California 91320 United States: SAGE Publications, Inc., 2010, doi:10.4135/9781412971966.n121, ISBN 978-1-4129-4050-4, retrieved June 17, 2025

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: location (link) - ^ Miller, Patrick B. (1995). "To "Bring the Race along Rapidly": Sport, Student Culture, and Educational Mission at Historically Black Colleges during the Interwar Years". History of Education Quarterly. 35 (2): 111–33. doi:10.2307/369629. ISSN 0018-2680. JSTOR 369629. S2CID 147170256.

- ^ Miller, Patrick B; Wiggins, David Kenneth, eds. (2004). Sport and the color line: black athletes and race relations in twentieth-century America. Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-94610-0. OCLC 53155353.

- ^ a b "Jewish Prof's and HBCU's – African American Registry". African American Registry. Retrieved October 23, 2018.

- ^ a b c Hoch, Paul K. (May 11, 1983). "The reception of central European refugee physicists of the 1930s: USSR, UK, US". Annals of Science. 40 (3): 217–46. doi:10.1080/00033798300200211. ISSN 0003-3790.

- ^ Gilligan, Heather (February 10, 2017). "After fleeing the Nazis, many Jewish refugee professors found homes at historically Black colleges". Timeline. Retrieved December 6, 2018.

- ^ Marybeth Gasman, "Scylla and Charybdis: Navigating the Waters of Academic Freedom at Fisk University during Charles S. Johnson's Administration (1946–1956)", American Educational Research Journal 36, no. 4 (1999): 739–58.

- ^ Willie, Charles Vert; Reddick, Richard J.; Brown, Ronald (2006). The Black College Mystique. Rowman & Littlefield. ISBN 978-0-7425-4617-2.

jewish refugees teaching in black colleges.

- ^ Foster, Lenoar (November 11, 2001). "The Not-So-Invisible Professors". Urban Education. 36 (5): 611–29. doi:10.1177/0042085901365006. ISSN 0042-0859. S2CID 145633996.

- ^ a b Jewell, Joseph O. (January 1, 2002). "To Set an Example: The Tradition of Diversity at Historically Black Colleges and Universities". Urban Education. 37 (1): 7–21. doi:10.1177/0042085902371002. S2CID 145115998.

- ^ "How HBCUs Contributed to the 1940s War Effort". Journal of Blacks in Higher Education. July 12, 2012.

- ^ Philo Hutcheson, Marybeth Gasman, and Kijua Sanders-McMurtry, "Race and Equality in the Academy: Rethinking Higher Education Actors and the Struggle for Equality in the Post-World War II Period", Journal of Higher Education 82, no. 2 (2011): 121–53

- ^ Smith, Walter L. (1994), The Magnificent Twelve: Florida's Black Junior Colleges, Winter Park, Florida: FOUR-G Publishers, ISBN 1-885066-01-5

- ^ 20 U.S.C. § 1062.

- ^ The Act, as amended, defines a "part B institution" as: "...any historically Black college or university that was established before 1964, whose principal mission was, and is, the education of black Americans, and that is accredited by a nationally recognized accrediting agency or association determined by the Secretary [of Education] to be a reliable authority as to the quality of training offered or is, according to such an agency or association, making reasonable progress toward accreditation." U.S. Department of Education (January 15, 2008). "HBCUs: A National Resource". White House Initiative on Historically Black Colleges and Universities. Archived from the original on May 13, 2008. Retrieved February 8, 2008.

20 U.S.C. § 1061. - ^ "About Us – White House Initiative on Historically Black Colleges and Universities". Sites.ed.gov. Retrieved August 24, 2016.

- ^ Gasman, Marybeth; Tudico, Christopher L. (2008). Historically Black Colleges and Universities: triumphs, troubles, and taboos (1st ed.). New York: Palgrave Macmillan. pp. 4–5. ISBN 978-0-230-61726-1.

- ^ "HBCU Library Alliance". Hbuclibraries.org. April 23, 2010. Retrieved May 15, 2010.

- ^ "Members of Congress Launch Bipartisan Congressional HBCU Caucus". Byrne.house.gov. April 28, 2015. Retrieved August 24, 2016.

- ^ "Bipartisan Historically Black Colleges and Universities (HBCU) Caucus". October 11, 2016.

- ^ "2015 HBCU Week Conference – White House Initiative on Historically Black Colleges and Universities". Sites.ed.gov. Retrieved August 24, 2016.

- ^ "Gov. Kay Ivey signs proclamation declaring October Alabama HBCU Month". October 13, 2022.

- ^ "Historically Black Colleges and Universities in N.C". Spectrumlocalnews.com. February 23, 2022. Retrieved August 4, 2022.

- ^ "Howard University Makes History as First HBCU to Achieve Top Research Status". February 13, 2025.

- ^ "Many HBCUs See a Surge In Enrollments". The Journal of Blacks in Higher Education. October 7, 2024.

- ^ "Enrollments Surge at HBCUS | Insight into Academia". October 11, 2024.

- ^ "HBCUs: Addressing the Decline in Black Male Enrollment | AIBM". American Institute for Boys and Men.

- ^ "Transforming Futures: The Economic Engine of HBCUs" (PDF).

- ^ a b Rivera, Heidi (November 15, 2023). "HBCU and MSI Facts and Statistics". Bankrate.

- ^ "Pell Grant Statistics [2023]: How Many Receive per Year".

- ^ "Analyzing Admissions and Financial Aid Practices at HBCUs". August 9, 2023.

- ^ "MacKenzie Scott Donated $560 Million to 23 HBCUs. These Are the Other Things They Have in Common". August 7, 2021.

- ^ Marybeth Gasman & Thai-Huy Nguyen, Making Black Scientists: A Call to Action. (Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press, 2019). ISBN 978-0-674-91658-6

- ^ a b "The NCES Fast Facts Tool provides quick answers to many education questions (National Center for Education Statistics)". Nces.ed.gov. Retrieved October 25, 2017.

- ^ Robert Nathenson, Andrés Castro Samayoa, & Marybeth Gasman, Moving Upward & Onward: Income Mobility and Historically Black Colleges and Universities, New Brunswick, New Jersey: Rutgers Center for Minority Serving Institutions, 2019. [ISBN missing]

- ^ William Casey Boland, Marybeth Gasman, Andrés Castro Samayoa, and DeShaun Bennett, "The Effect of Enrolling in Minority Serving Institutions on Earnings Compared to Non-Minority Serving Institutions: A College Scorecard Analysis", Research in Higher Education (2019).

- ^ "Digest of Education Statistics, 2016". Nces.ed.gov. Retrieved October 25, 2017.

- ^ Van Camp, D., Barden, J., Sloan, L.R., & Clarke, R.P. (2009). "Choosing an HBCU: An Opportunity to Pursue Racial Self-Development". The Journal of Negro Education, 78 (4), 457–468. ProQuest 222068417

- ^ Robert Palmer, Robert Shorette, and Marybeth Gasman (Eds.), Exploring Diversity at Historically Black Colleges and Universities: Implications for Policy and Practice (San Francisco: Jossey-Bass, 2014).ISBN 978-1-119-10843-6

- ^ Marybeth Gasman and Felecia Commodore (Eds.), Opportunities and Challenges at Historically Black Colleges and Universities (New York: Palgrave Press, 2014). ISBN 978-1-349-50267-7

- ^ "More Non-Black Students Attending HBCUs" Archived July 13, 2016, at the Wayback Machine. Newsone.com (2010-10-07). Retrieved on 2013-08-09.

- ^ "Why Black Colleges Might Be the Best Bargains". U.S. News & World Report. Retrieved August 24, 2016.

- ^ Marybeth Gasman, Andrés Castro Samayoa, & Michael Nettles (Eds.). The Return on Investment for Minority Serving Institutions. (San Francisco, California: Wiley Press, 2017). [ISBN missing]

- ^ Marybeth Gasman, Andrés Castro Samayoa, William Casey Boland, & Paola Esmieu (Eds.), Educational Challenges and Opportunities at Minority Serving Institutions (New York: Routledge Press, 2018) ISBN 978-1-138-57261-4.

- ^ "Apart No More? HBCUs Heading Into an Era of Change". hbcuconnect.com. Retrieved August 24, 2016.

- ^ "Bluefield State University : Student Profile Analysis: College Wide Summary: Fall Term 2017 Census" (PDF). Bluefieldstate.edu. Retrieved October 25, 2017.

- ^ "West Virginia State University: Office of Institutional Research and Assessment: 2015–2016 University Factbook" (PDF). Wvstateu.edu. Retrieved October 25, 2017.

- ^ "Kentucky State University: Statistics" (PDF). Kysu.edu. Retrieved October 25, 2017.

- ^ "University of the District of Columbia: Factbook" (PDF). Docs.udc.edu. Retrieved October 25, 2017.

- ^ "Delaware State University: Factbook" (PDF). Desu.edu. Retrieved October 25, 2017.

- ^ "Fayetteville State University: Fact Book: 2016–2017" (PDF). Uncfsu.edu. Retrieved October 25, 2017.

- ^ "Tableau Public". Public.tableau.com. Retrieved October 25, 2017.

- ^ "Elizabeth City State University: Factbook" (PDF). Ecsu.edu. Retrieved October 25, 2017.

- ^ U.S. News & World Report Best Colleges, 2011 ed. Directory p. 182

- ^ "NCAT IR – University Fast Facts". ir.ncat.edu. Retrieved October 25, 2017.

- ^ "Lincoln University: Factbook" (PDF). Lincoln.edu. Retrieved October 25, 2017.

- ^ U.S. News & World Report Best Colleges, 2011 ed. Directory p. 129

- ^ "HBCU Library Alliance – Cornell University Library Digitization Initiative Update" (PDF). Hbculigraries.org. 2006. Retrieved December 1, 2010.

- ^ "Modest Gains for Black Colleges Online". Insidehighered.com. 2010. Retrieved January 4, 2012.

- ^ "N.C. A&T Announces New Athletics Affiliation: Big South Conference". Ncat.edu. Retrieved December 4, 2020.

- ^ "CAA Welcomes Hampton University, Monmouth University and Stony Brook University as New Members" (Press release). Colonial Athletic Association. January 25, 2022. Retrieved January 25, 2022.

- ^ "CAA Welcomes North Carolina A&T as Newest Member of the Conference" (Press release). Colonial Athletic Association. February 22, 2022. Retrieved February 22, 2022.

- ^ "NAIA Conferences". Naia.org. Retrieved December 4, 2020.

- ^ Allen, Tony; Glover, Gelnda. "101 HBCUs get nearly 7 times less money than 1 other school. That must change". The Washington Post.

- ^ "Fact Sheet: Obama Administration Investments in Historically Black Colleges and Universities | National Center on Safe Supportive Learning Environments (NCSSLE)". safesupportivelearning.ed.gov.

- ^ "Trump signs bill restoring funding for black colleges". Associated Press. April 20, 2021.

- ^ The White House (December 17, 2021). "FACT SHEET: The Biden-Harris Administration's Historic Investments and Support for Historically Black Colleges and Universities". The White House. Archived from the original on October 25, 2022. Retrieved October 25, 2022.

- ^ "FACT SHEET: State-by-State Analysis of Record $2.7 Billion American Rescue Plan Investment in Historically Black Colleges and Universities". March 7, 2022.

- ^ "Fact Sheet: President Donald J. Trump Promotes Excellence and Innovation at HBCUs". April 23, 2025.

- ^ "U.S. Department of Education Makes Historic Grant Investments in Programs That Bolster Educational Outcomes | U.S. Department of Education". September 15, 2025.

- ^ "For the Culture: It's Time for HBCU Homecomings". October 6, 2019.

- ^ "Post-Shutdown HBCU Homecomings Bring Much-Needed Boosts to Revenues". US News & World Report. November 1, 2022. Retrieved April 4, 2023.

- ^ "Homecoming: A Celebration of HBCUs and Their Legacies". National Museum of African American History and Culture.

- ^ "3 HBCU Alums on What Makes Homecoming So Meaningful".

- ^ "Homecomings at HBCUs must be safe spaces for celebration, not targets of gun violence". November 16, 2024.

- ^ Suggs, Ernie. "Shootings at HBCU homecomings may change the way we view annual rite". The Atlanta Journal-Constitution.

Further reading

[edit]- Arnold, Bruce Makoto; Mitchell, Roland; Arnold, Noelle W. (2015). "Massified Illusions of Difference: Photography and the Mystique of the American Historically Black Colleges and Universities (HBCUs)". Journal of American Studies of Turkey. 41: 69–94. Retrieved September 3, 2019.

- Betsey, Charles L., ed. (2011). Historically black colleges and universities. Transaction Publishers. ISBN 978-1-4128-1219-1.

- Boonshoft, Mark. "Histories of Nineteenth-Century Education and the Civil War Era." Journal of the Civil War Era 12.2 (2022): 234–261.

- Brooks, F. Erik; Starks, Glenn L. (2011). Historically Black colleges and universities: an encyclopedia. Greenwood. ISBN 978-0-313-39416-4.

- Cohen, Rodney T. (2000). The Black Colleges of Atlanta (College History Series). Arcadia Pub. ISBN 978-0-7385-0554-1. Archived from the original on May 22, 2009. Retrieved January 14, 2020.

- Favors, Jelani M. (2019). Shelter in a Time of Storm: How Black Colleges Fostered Generations of Leadership and Activism. Chapel Hill, North Carolina: University of North Carolina Press. ISBN 978-1-4696-4833-0. OCLC 1048660765.

- Gasman, Marybeth; Tudico, Christopher L., eds. (2008). Historically Black colleges and universities: triumphs, troubles, and taboos (1st ed.). Palgrave Macmillan. ISBN 978-0-230-60273-1.

- Harris, Adam (2021). The State Must Provide: Why America's Colleges Have Always Been Unequal—and How to Set Them Right. New York: Ecco. ISBN 978-0-06-297648-2. OCLC 1204635631.

- Lovett, Bobby L. (2015). America's historically Black colleges & universities: a narrative history from the nineteenth century into the twenty-first century (First ed.). Mercer University Press. ISBN 978-0-88146-534-1.

- Mays, Benjamin E. (1960). "The Significance of the Negro Private and Church-Related College". The Journal of Negro Education. 29 (3): 245–51. doi:10.2307/2293639. ISSN 0022-2984. JSTOR 2293639.

- Minor, James T. (2008). "A Contemporary Perspective on the Role of Public HBCUs: Perspicacity from Mississippi". The Journal of Negro Education. 77 (4): 323–35. ISSN 0022-2984. JSTOR 25608702.

- One among the others (March 29, 2018). "Reflections of an HBCU Alumnus (Howard University)". Anuntoldstoryblog.

- Palmer, Robert T.; Hilton, Adriel A.; Fountaine, Tiffany P., eds. (2012). Black graduate education at historically Black colleges and universities trends, experiences, and outcomes. Information Age Pub. ISBN 978-1-61735-852-4.

- Provasnik, Stephen; Shafer, Linda L. (2004). "Historically Black Colleges and Universities, 1976 to 2001". National Center for Education Statistics. NCES 2004–062.

- Rascoe, Ayesha, ed. (2024). HBCU Made: A Celebration of the Black College Experience. Chapel Hill, North Carolina: Algonquin Books of Chapel Hill. ISBN 978-1-64375-386-7. OCLC 1378381766.

- Roebuck, Julian B.; Murty, Komanduri Srinivasa (1993). Historically black colleges and universities: their place in American higher education. Praeger. ISBN 978-0-275-94267-0.

- Wright, Stephanie R. (2008). "Self-Determination, Politics, and Gender on Georgia's Black College Campuses, 1875–1900". The Georgia Historical Quarterly. 92 (1): 93–119. ISSN 0016-8297. JSTOR 40585040.

Primary sources

[edit]- Negro Education: A Study of the Private and Higher Schools for Colored People in the United States. Bulletin, 1916, No. 38. Vol. I. Washington, D.C.: Bureau of Education, Department of the Interior. 1917.

- Negro Education: A Study of the Private and Higher Schools for Colored People in the United States. Bulletin, 1916, No. 39. Vol. II. Washington, D.C.: Bureau of Education, Department of the Interior. 1917.

External links

[edit]- National Center for Education Statistics' College Navigator information about HBCUs

- HBCU Sports history

- National Association for Equal Opportunity in Higher Education (NAFEO)—national membership association of all of the nation's HBCUs and Predominantly Black Institutions (PBIs)