Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Homology (biology)

View on Wikipedia

In biology, homology is similarity in anatomical structures or genes between organisms of different taxa due to shared ancestry, regardless of current functional differences. Evolutionary biology explains homologous structures as retained heredity from a common ancestor after having been subjected to adaptive modifications for different purposes as the result of natural selection.

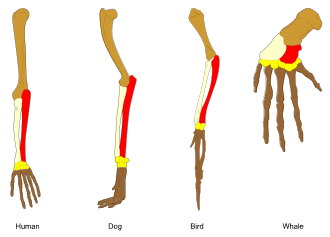

The term was first applied to biology in a non-evolutionary context by the anatomist Richard Owen in 1843. Homology was later explained by Charles Darwin's theory of evolution in 1859, but had been observed before this from Aristotle's biology onwards, and it was explicitly analysed by Pierre Belon in 1555. A common example of homologous structures is the forelimbs of vertebrates, where the wings of bats and birds, the arms of primates, the front flippers of whales, and the forelegs of four-legged vertebrates like horses and crocodilians are all derived from the same ancestral tetrapod structure.

In developmental biology, organs that developed in the embryo in the same manner and from similar origins, such as from matching primordia in successive segments of the same animal, are serially homologous. Examples include the legs of a centipede, the maxillary and labial palps of an insect, and the spinous processes of successive vertebrae in a vertebrate's backbone.

Sequence homology between protein or DNA sequences is similarly defined in terms of shared ancestry. Two segments of DNA can have shared ancestry because of either a speciation event (orthologs) or a duplication event (paralogs). Homology among proteins or DNA is inferred from their sequence similarity. Significant similarity is strong evidence that two sequences are related by divergent evolution from a common ancestor. Alignments of multiple sequences are used to discover the homologous regions.

Homology remains controversial in animal behaviour, but there is suggestive evidence that, for example, dominance hierarchies are homologous across the primates.

History

[edit]

Homology was noticed by Aristotle (c. 350 BC),[1] and was explicitly analysed by Pierre Belon in his 1555 Book of Birds, where he systematically compared the skeletons of birds and humans. The pattern of similarity was interpreted as part of the static great chain of being through the mediaeval and early modern periods: it was not then seen as implying evolutionary change. In the German Naturphilosophie tradition, homology was of special interest as demonstrating unity in nature.[1][2] In 1790, Goethe stated his foliar theory in his essay "Metamorphosis of Plants", showing that flower parts are derived from leaves.[3] The serial homology of limbs was described late in the 18th century. The French zoologist Étienne Geoffroy Saint-Hilaire showed in 1818 in his theorie d'analogue ("theory of homologues") that structures were shared between fishes, reptiles, birds and mammals.[4] When Geoffroy went further and sought homologies between Georges Cuvier's embranchements, such as vertebrates and molluscs, his claims triggered the 1830 Cuvier–Geoffroy debate. Geoffroy stated the principle of connections, namely that what is important is the relative position of different structures and their connections to each other.[2]

The embryologist Karl Ernst von Baer stated what are now called von Baer's laws in 1828, noting that related animals begin their development as similar embryos and then diverge: thus, animals in the same family are more closely related and diverge later than animals which are only in the same order and have fewer homologies. Von Baer's theory recognises that each taxon (such as a family) has distinctive shared features, and that embryonic development parallels the taxonomic hierarchy: not the same as recapitulation theory.[2] The term "homology" was first used in biology by the anatomist Richard Owen in 1843 when studying the similarities of vertebrate fins and limbs, defining it as the "same organ in different animals under every variety of form and function",[5] and contrasting it with the matching term "analogy" which he used to describe different structures with the same function. Owen codified three main criteria for determining if features were homologous: position, development and composition. In 1859, Charles Darwin explained homologous structures as meaning that the organisms concerned shared a body plan from a common ancestor, and that taxa were branches of a single tree of life.[1][2][6]

Definition

[edit]The word homology, coined in about 1656, is derived from the Greek ὁμόλογος homologos from ὁμός homos 'same' and λόγος logos 'relation'.[7][8][a]

Similar biological structures or sequences in different taxa are homologous if they are derived from a common ancestor. Homology thus implies divergent evolution. For example, many insects (such as dragonflies) possess two pairs of flying wings. In beetles, the first pair of wings has evolved into a pair of hard wing covers,[11] while in Dipteran flies the second pair of wings has evolved into small halteres used for balance.[b][12]

Similarly, the forelimbs of ancestral vertebrates have evolved into the front flippers of whales, the wings of birds, the running forelegs of dogs, deer and horses, the short forelegs of frogs and lizards, and the grasping hands of primates including humans. The same major forearm bones (humerus, radius and ulna[c]) are found in fossils of lobe-finned fish such as Eusthenopteron.[13]

Homology vs. analogy

[edit]

The opposite of homologous organs are analogous organs which do similar jobs in two taxa that were not present in their most recent common ancestor but, rather, evolved separately. For example, the wings of insects and birds evolved independently in widely separated groups, and converged functionally to support powered flight, so they are analogous. Similarly, the wings of a sycamore maple seed and the wings of a bird are analogous but not homologous, as they develop from quite different structures.[14][15] A structure can be homologous at one level, but only analogous at another. Pterosaur, bird and bat wings are analogous as wings, but homologous as forelimbs because the organ served as a forearm (not a wing) in the last common ancestor of tetrapods, and evolved in different ways in the three groups. Thus, in the pterosaurs, the "wing" involves both the forelimb and the hindlimb.[16] Analogy is called homoplasy in cladistics, and convergent or parallel evolution in evolutionary biology.[17][18]

In cladistics

[edit]Specialised terms are used in taxonomic research. Primary homology is a researcher's initial hypothesis based on similar structure or anatomical connections, suggesting that a character state in two or more taxa share is shared due to common ancestry. Primary homology may be conceptually broken down further: we may consider all of the states of the same character as "homologous" parts of a single, unspecified, transformation series. This has been referred to as topographical correspondence. For example, in an aligned DNA sequence matrix, all of the A, G, C, T or implied gaps at a given nucleotide site are homologous in this way. Character state identity is the hypothesis that the particular condition in two or more taxa is "the same" as far as our character coding scheme is concerned. Thus, two Adenines at the same aligned nucleotide site are hypothesized to be homologous unless that hypothesis is subsequently contradicted by other evidence. Secondary homology is implied by parsimony analysis, where a character state that arises only once on a tree is taken to be homologous.[19][20] As implied in this definition, many cladists consider secondary homology to be synonymous with synapomorphy, a shared derived character or trait state that distinguishes a clade from other organisms.[21][22][23]

Shared ancestral character states, symplesiomorphies, represent either synapomorphies of a more inclusive group, or complementary states (often absences) that unite no natural group of organisms. For example, the presence of wings is a synapomorphy for pterygote insects, but a symplesiomorphy for holometabolous insects. Absence of wings in non-pterygote insects and other organisms is a complementary symplesiomorphy that unites no group (for example, absence of wings provides no evidence of common ancestry of silverfish, spiders and annelid worms). On the other hand, absence (or secondary loss) of wings is a synapomorphy for fleas. Patterns such as these lead many cladists to consider the concept of homology and the concept of synapomorphy to be equivalent.[23][24] Some cladists follow the pre-cladistic definition of homology of Haas and Simpson,[25] and view both synapomorphies and symplesiomorphies as homologous character states.[26]

In different taxa

[edit]

Homologies provide the fundamental basis for all biological classification, although some may be highly counter-intuitive. For example, deep homologies like the pax6 genes that control the development of the eyes of vertebrates and arthropods were unexpected, as the organs are anatomically dissimilar and appeared to have evolved entirely independently.[27][28]

In arthropods

[edit]The embryonic body segments (somites) of different arthropod taxa have diverged from a simple body plan with many similar appendages which are serially homologous, into a variety of body plans with fewer segments equipped with specialised appendages.[29] The homologies between these have been discovered by comparing genes in evolutionary developmental biology.[27]

| Somite (body segment) |

Trilobite (Trilobitomorpha)

|

Spider (Chelicerata)

|

Centipede (Myriapoda) |

Insect (Hexapoda)

|

Shrimp (Crustacea)

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | antennae | chelicerae (jaws and fangs) | antennae | antennae | 1st antennae |

| 2 | 1st legs | pedipalps | - | - | 2nd antennae |

| 3 | 2nd legs | 1st legs | mandibles | mandibles | mandibles (jaws) |

| 4 | 3rd legs | 2nd legs | 1st maxillae | 1st maxillae | 1st maxillae |

| 5 | 4th legs | 3rd legs | 2nd maxillae | 2nd maxillae | 2nd maxillae |

| 6 | 5th legs | 4th legs | collum (no legs) | 1st legs | 1st legs |

| 7 | 6th legs | - | 1st legs | 2nd legs | 2nd legs |

| 8 | 7th legs | - | 2nd legs | 3rd legs | 3rd legs |

| 9 | 8th legs | - | 3rd legs | - | 4th legs |

| 10 | 9th legs | - | 4th legs | - | 5th legs |

Among insects, the stinger of the female honey bee is a modified ovipositor, homologous with ovipositors in other insects such as the Orthoptera, Hemiptera and those Hymenoptera without stingers.[30]

In mammals

[edit]The three small bones in the middle ear of mammals including humans, the malleus, incus and stapes, are today used to transmit sound from the eardrum to the inner ear. The malleus and incus develop in the embryo from structures that form jaw bones (the quadrate and the articular) in lizards, and in fossils of lizard-like ancestors of mammals. Both lines of evidence show that these bones are homologous, sharing a common ancestor.[31]

Among the many homologies in mammal reproductive systems, ovaries and testicles are homologous.[32]

Rudimentary organs such as the human tailbone, now much reduced from their functional state, are readily understood as signs of evolution, the explanation being that they were cut down by natural selection from functioning organs when their functions were no longer needed, but make no sense at all if species are considered to be fixed. The tailbone is homologous to the tails of other primates.[33]

In plants

[edit]Leaves, stems and roots

[edit]In many plants, defensive or storage structures are made by modifications of the development of primary leaves, stems and roots. Leaves are variously modified from photosynthetic structures to form the insect-trapping pitchers of pitcher plants, the insect-trapping jaws of the Venus flytrap, and the spines of cacti, all homologous.[34]

| Primary organs | Defensive structures | Storage structures |

|---|---|---|

| Leaves | Spines | Swollen leaves (e.g. succulents) |

| Stems | Thorns | Tubers (e.g. potato), rhizomes (e.g. ginger), fleshy stems (e.g. cacti) |

| Roots | - | Root tubers (e.g. sweet potato), taproot (e.g. carrot) |

Certain compound leaves of flowering plants are partially homologous both to leaves and shoots, because their development has evolved from a genetic mosaic of leaf and shoot development.[35][36]

-

One pinnate leaf of European ash

-

Detail of palm leaf

-

The very large leaves of the banana, Musa acuminata

-

Insect-trapping leaf of a Venus flytrap

-

Insect-trapping leaf of pitcher plant

Flower parts

[edit]

The four types of flower parts, namely carpels, stamens, petals and sepals, are homologous with and derived from leaves, as Goethe correctly noted in 1790. The development of these parts through a pattern of gene expression in the growing zones (meristems) is described by the ABC model of flower development. Each of the four types of flower parts is serially repeated in concentric whorls, controlled by a small number of genes acting in various combinations. Thus, A genes working alone result in sepal formation; A and B together produce petals; B and C together create stamens; C alone produces carpels. When none of the genes are active, leaves are formed. Two more groups of genes, D to form ovules and E for the floral whorls, complete the model. The genes are evidently ancient, as old as the flowering plants themselves.[3]

Developmental biology

[edit]

Developmental biology can identify homologous structures that arose from the same tissue in embryogenesis. For example, adult snakes have no legs, but their early embryos have limb-buds for hind legs, which are soon lost as the embryos develop. The implication that the ancestors of snakes had hind legs is confirmed by fossil evidence: the Cretaceous snake Pachyrhachis problematicus had hind legs complete with hip bones (ilium, pubis, ischium), thigh bone (femur), leg bones (tibia, fibula) and foot bones (calcaneum, astragalus) as in tetrapods with legs today.[37]

Sequence homology

[edit]

As with anatomical structures, sequence homology between protein or DNA sequences is defined in terms of shared ancestry. Two segments of DNA can have shared ancestry because of either a speciation event (orthologs) or a duplication event (paralogs). Homology among proteins or DNA is typically inferred from their sequence similarity. Significant similarity is strong evidence that two sequences are related by divergent evolution of a common ancestor. Alignments of multiple sequences are used to indicate which regions of each sequence are homologous.[39]

Homologous sequences are orthologous if they are descended from the same ancestral sequence separated by a speciation event: when a species diverges into two separate species, the copies of a single gene in the two resulting species are said to be orthologous. The term "ortholog" was coined in 1970 by the molecular evolutionist Walter Fitch.[40]

Homologous sequences are paralogous if they were created by a duplication event within the genome. For gene duplication events, if a gene in an organism is duplicated, the two copies are paralogous. They can shape the structure of whole genomes and thus explain genome evolution to a large extent. Examples include the Homeobox (Hox) genes in animals. These genes not only underwent gene duplications within chromosomes but also whole genome duplications. As a result, Hox genes in most vertebrates are spread across multiple chromosomes: the HoxA–D clusters are the best studied.[41]

Some sequences are homologous, but they have diverged so much that their sequence similarity is not sufficient to establish homology. However, many proteins have retained very similar structures, and structural alignment can be used to demonstrate their homology.[42]

In behaviour

[edit]It has been suggested that some behaviours might be homologous, based either on sharing across related taxa or on common origins of the behaviour in an individual's development; however, the notion of homologous behavior remains controversial,[43] largely because behavior is more prone to multiple realizability than other biological traits. For example, D. W. Rajecki and Randall C. Flanery, using data on humans and on nonhuman primates, argue that patterns of behaviour in dominance hierarchies are homologous across the primates.[44]

As with morphological features or DNA, shared similarity in behavior provides evidence for common ancestry.[45] The hypothesis that a behavioral character is not homologous should be based on an incongruent distribution of that character with respect to other features that are presumed to reflect the true pattern of relationships. This is an application of Willi Hennig's[46] auxiliary principle.

Notes

[edit]- ^ The alternative terms "homogeny" and "homogenous" were also used in the late 1800s and early 1900s. However, these terms are now archaic in biology, and the term "homogenous" is now generally found as a misspelling of the term "homogeneous" which refers to the uniformity of a mixture.[9][10]

- ^ If the two pairs of wings are considered as interchangeable, homologous structures, this may be described as a parallel reduction in the number of wings, but otherwise the two changes are each divergent changes in one pair of wings.

- ^ These are coloured in the lead image: humerus brown, radius pale buff, ulna red.

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b c d Panchen, A. L. (1999). "Homology — History of a Concept". Novartis Foundation Symposium 222 - Homology. Novartis Foundation Symposia. Vol. 222. pp. 5–18, discussion 18–23. doi:10.1002/9780470515655.ch2. ISBN 978-0-470-51565-5. PMID 10332750.

- ^ a b c d Brigandt, Ingo (23 November 2011). "Essay: Homology". The Embryo Project Encyclopedia.

- ^ a b Dornelas, Marcelo Carnier; Dornelas, Odair (2005). "From leaf to flower: Revisiting Goethe's concepts on the ¨metamorphosis¨ of plants". Brazilian Journal of Plant Physiology. 17 (4): 335–344. doi:10.1590/S1677-04202005000400001.

- ^ Geoffroy Saint-Hilaire, Étienne (1818). Philosophie anatomique. Vol. 1: Des organes respiratoires sous le rapport de la détermination et de l'identité de leurs piecès osseuses. Vol. 1. Paris: J. B. Baillière.

- ^ Owen, Richard (1843). Lectures on the Comparative Anatomy and Physiology of the Invertebrate Animals, Delivered at the Royal College of Surgeons in 1843. Longman, Brown, Green, and Longmans. pp. 374, 379.

- ^ Sommer, R. J. (July 2008). "Homology and the hierarchy of biological systems". BioEssays. 30 (7): 653–658. doi:10.1002/bies.20776. PMID 18536034.

- ^ Bower, Frederick Orpen (1906). "Plant Morphology". Congress of Arts and Science: Universal Exposition, St. Louis, 1904. Houghton, Mifflin. p. 64.

- ^ Williams, David Malcolm; Forey, Peter L. (2004). Milestones in Systematics. CRC Press. p. 198. ISBN 978-0-415-28032-7.

- ^ "homogeneous, adj.". OED Online. March 2016. Oxford University Press. http://www.oed.com/view/Entry/88045? (accessed 9 April 2016).

- ^ "homogenous, adj.". OED Online. March 2016. Oxford University Press. http://www.oed.com/view/Entry/88055? (accessed 9 April 2016).

- ^ Wagner, Günter P. (2014). Homology, Genes, and Evolutionary Innovation. Princeton University Press. pp. 53–54. ISBN 978-1-4008-5146-1.

elytra have very little similarity with typical wings, but are clearly homologous to forewings. Hence butterflies, flies, and beetles all have two pairs of dorsal appendages that are homologous among species.

- ^ Lipshitz, Howard D. (2012). Genes, Development and Cancer: The Life and Work of Edward B. Lewis. Springer. p. 240. ISBN 978-1-4419-8981-9.

For example, wing and haltere are homologous, yet widely divergent, organs that normally arise as dorsal appendages of the second thoracic (T2) and third thoracic (T3) segments, respectively.

- ^ "Homology: Legs and Limbs". UC Berkeley. Retrieved 15 December 2016.

- ^ "Secret Found to Flight of 'Helicopter Seeds'". LiveScience. 11 June 2009. Retrieved 2 March 2017.

- ^ Lentink, D.; Dickson, W. B.; van Leeuwen, J. L.; Dickinson, M. H. (12 June 2009). "Leading-Edge Vortices Elevate Lift of Autorotating Plant Seeds" (PDF). Science. 324 (5933): 1438–1440. Bibcode:2009Sci...324.1438L. doi:10.1126/science.1174196. PMID 19520959. S2CID 12216605.

- ^ Scotland, R. W. (2010). "Deep homology: A view from systematics". BioEssays. 32 (5): 438–449. doi:10.1002/bies.200900175. PMID 20394064. S2CID 205469918.

- ^ Cf. Butler, A. B.: Homology and Homoplasty. In: Squire, Larry R. (Ed.): Encyclopedia of Neuroscience, Academic Press, 2009, pp. 1195–1199.

- ^ "Homologous structure vs. analogous structure: What is the difference?". Archived from the original on 17 August 2017. Retrieved 27 September 2016.

- ^ de Pinna, M. C. C. (1991). "Concepts and Tests of homology in the cladistic paradigm". Cladistics. 7 (4): 367–394. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.487.2259. doi:10.1111/j.1096-0031.1991.tb00045.x. S2CID 3551391.

- ^ Brower, Andrew V. Z.; Schawaroch, V. (1996). "Three steps of homology assessment". Cladistics. 12 (3): 265–272. doi:10.1111/j.1096-0031.1996.tb00014.x. PMID 34920625. S2CID 85385271.

- ^ Page, Roderick D.M.; Holmes, Edward C. (2009). Molecular Evolution: A Phylogenetic Approach. John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 978-1-4443-1336-9.

- ^ Brower, Andrew V. Z.; de Pinna, Mario C. C. (24 May 2012). "Homology and errors". Cladistics. 28 (5): 529–538. doi:10.1111/j.1096-0031.2012.00398.x. PMID 34844384. S2CID 86806203.

- ^ a b Brower, Andrew V. Z.; de Pinna, Mario C. C. (2014). "About Nothing". Cladistics. 30 (3): 330–336. doi:10.1111/cla.12050. PMID 34788975. S2CID 221550586.

- ^ Patterson, C. (1982). "Morphological characters and homology". In K. A. Joysey; A. E. Friday (eds.). Problems of Phylogenetic Reconstruction. London and New York: Academic Press. pp. 21–74.

- ^ Haas, O. and G. G. Simpson. 1946. Analysis of some phylogenetic terms, with attempts at redefinition. Proc. Amer. Phil. Soc. 90:319-349.

- ^ Nixon, K. C.; Carpenter, J. M. (2011). "On homology". Cladistics. 28 (2): 160–169. doi:10.1111/j.1096-0031.2011.00371.x. PMID 34861754. S2CID 221582887.

- ^ a b Brusca, R. C.; Brusca, G. J. (1990). Invertebrates. Sinauer Associates. p. 669.

- ^ Carroll, Sean B. (2006). Endless Forms Most Beautiful. Weidenfeld & Nicolson. pp. 28, 66–69. ISBN 978-0-297-85094-6.

- ^ Hall, Brian (2008). Homology. John Wiley. p. 29. ISBN 978-0-470-51566-2.

- ^ Shing, H.; Erickson, E. H. (1982). "Some ultrastructure of the honeybee (Apis mellifera L.) sting". Apidologie. 13 (3): 203–213. doi:10.1051/apido:19820301.

- ^ "Homology: From jaws to ears — an unusual example of a homology". UC Berkeley. Retrieved 15 December 2016.

- ^ Hyde, Janet Shibley; DeLamater, John D. (June 2010). "Chapter 5" (PDF). Understanding Human Sexuality (11th ed.). New York: McGraw-Hill. p. 103. ISBN 978-0-07-338282-1.

- ^ Larson, Edward J. (2004). Evolution: The Remarkable History of Scientific Theory. Modern Library. p. 112. ISBN 978-0-679-64288-6.

- ^ "Homology: Leave it to the plants". University of California at Berkeley. Retrieved 7 May 2017.

- ^ Sattler, R. (1984). "Homology — a continuing challenge". Systematic Botany. 9 (4): 382–394. Bibcode:1984SysBo...9..382S. doi:10.2307/2418787. JSTOR 2418787.

- ^ Sattler, R. (1994). "Homology, homeosis, and process morphology in plants". In Hall, Brian Keith (ed.). Homology: the hierarchical basis of comparative biology. Academic Press. pp. 423–75. ISBN 978-0-12-319583-8.

- ^ "Homologies: developmental biology". UC Berkeley. Retrieved 15 December 2016.

- ^ "Clustal FAQ #Symbols". Clustal. Archived from the original on 24 October 2016. Retrieved 8 December 2014.

- ^ Koonin, E. V. (2005). "Orthologs, Paralogs, and Evolutionary Genomics". Annual Review of Genetics. 39: 309–38. doi:10.1146/annurev.genet.39.073003.114725. PMID 16285863.

- ^ Fitch, W. M. (June 1970). "Distinguishing homologous from analogous proteins". Systematic Zoology. 19 (2): 99–113. doi:10.2307/2412448. JSTOR 2412448. PMID 5449325.

- ^ Zakany, Jozsef; Duboule, Denis (2007). "The role of Hox genes during vertebrate limb development". Current Opinion in Genetics & Development. 17 (4): 359–366. doi:10.1016/j.gde.2007.05.011. ISSN 0959-437X. PMID 17644373.

- ^ Holm, Liisa; Laiho, Aleksi; Törönen, Petri; Salgado, Marco (23 November 2022). "DALI shines a light on remote homologs: one hundred discoveries". Protein Science. 32 (1) e4519. doi:10.1002/pro.4519. ISSN 0961-8368. PMC 9793968. PMID 36419248.

- ^ Moore, David S. (2013). "Importing the homology concept from biology into developmental psychology". Developmental Psychobiology. 55 (1): 13–21. doi:10.1002/dev.21015. PMID 22711075.

- ^ Rajecki, D. W.; Flanery, Randall C. (2013). Lamb, M. E.; Brown, A. L. (eds.). Social Conflict and Dominance in Children: a Case for a Primate Homology. Taylor and Francis. p. 125. ISBN 978-1-135-83123-3.

Finally, much recent information on children's and nonhuman primates' behavior in groups, a conjunction of hard human data and hard nonhuman primate data, lends credence to our comparison. Our conclusion is that, based on their agreement in several unusual characteristics, dominance patterns are homologous in primates. This agreement of unusual characteristics is found at several levels, including fine motor movement, gross motor movement, and behavior at the group level.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - ^ Wenzel, John W. 1992. Behavioral homology and phylogeny. Annual Review of Ecology and Systematics 23:361-381

- ^ Hennig, W. 1966. Phylogenetic Systematics. University of Illinois Press

Further reading

[edit]- Brigandt, Ingo (2011) "Essay: Homology." In: The Embryo Project Encyclopedia. ISSN 1940-5030. http://embryo.asu.edu/handle/10776/1754

- Carroll, Sean B. (2006). Endless Forms Most Beautiful. New York: W.W. Norton & Co. ISBN 978-0-297-85094-6.

- Carroll, Sean B. (2006). The making of the fittest: DNA and the ultimate forensic record of evolution. New York: W.W. Norton & Co. ISBN 978-0-393-06163-5.

- DePinna, M.C. (1991). "Concepts and tests of homology in the cladistic paradigm". Cladistics. 7 (4): 367–94. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.487.2259. doi:10.1111/j.1096-0031.1991.tb00045.x. S2CID 3551391.

- Dewey, C.N.; Pachter, L. (April 2006). "Evolution at the nucleotide level: the problem of multiple whole-genome alignment". Human Molecular Genetics. 15 (Spec No 1): R51 – R56. doi:10.1093/hmg/ddl056. PMID 16651369.

- Fitch, W.M. (May 2000). "Homology a personal view on some of the problems". Trends in Genetics. 16 (5): 227–31. doi:10.1016/S0168-9525(00)02005-9. PMID 10782117.

- Gegenbaur, G. (1898). Vergleichende Anatomie der Wirbelthiere ... Leipzig.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Haeckel, Еrnst (1866). Generelle Morphologie der Organismen. Bd 1-2. Вerlin.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location (link) CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Kuzniar, A.; van Ham, R.C.; Pongor, S.; Leunissen, J.A. (November 2008). "The quest for orthologs: finding the corresponding gene across genomes". Trends Genet. 24 (11): 539–551. doi:10.1016/j.tig.2008.08.009. PMID 18819722.

- Mindell, D.P.; Meyer, A. (2001). "Homology evolving" (PDF). Trends in Ecology and Evolution. 16 (8): 434–40. Bibcode:2001TEcoE..16..434M. doi:10.1016/S0169-5347(01)02206-6. Archived from the original (PDF) on 27 June 2010.

- Owen, Richard (1847). On the archetype and homologies of the vertebrate skeleton. London: John van Voorst, Paternoster Row.

External links

[edit] Media related to Homology at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Homology at Wikimedia Commons