Recent from talks

Contribute something

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Hussites

View on Wikipedia| Part of a series on |

| Protestantism |

|---|

|

|

|

The Hussites (Czech: Husité or Kališníci, "Chalice People"; Latin: Hussitae) were a Czech proto-Protestant Christian movement influenced by both the Byzantine Rite and John Wycliffe that followed the teachings of reformer Jan Hus (fl. 1401–1415), a part of the Bohemian Reformation.

The Czech lands had originally been Christianized by Byzantine Greek missionaries Saints Cyril and Methodius, who introduced the Byzantine Rite in the Old Church Slavonic liturgical language and the Byzantine tradition of Communion in both kinds administered by the holy spoon. Over the centuries that followed, however, the Roman Rite in Ecclesiastical Latin, which is less easily understood than Slavonic by native speakers of Old Czech, was imposed upon the Czech people despite considerable public resistance, by German-speaking bishops, beginning with Wiching, from the Holy Roman Empire. (See also Sázava Monastery).[1] As a cultural memory of both communion in both kinds and the Divine Liturgy in a language closer to the vernacular is believed to have survived well into the Renaissance, the ideas of Jan Hus and others like him swiftly gained a wide public following. After the trial and execution of Hus at the Council of Constance,[2] a series of crusades, civil wars, victories and compromises between various factions with different theological agendas broke out. At the end of the Hussite Wars (1420–1434), the now Catholic-supported Utraquist side came out victorious from protracted conflict against Jan Žižka and the Taborites, who embraced the more radical theological teachings of John Wycliffe and the Lollards, and became the dominant Hussite group in Bohemia.

Catholics and Utraquists were given legal equality in Bohemia after the religious peace of Kutná Hora in 1485. Bohemia and Moravia, or what is now the territory of the Czech Republic, remained majority Hussite for two centuries. Roman Catholicism was only reimposed by the Holy Roman Emperor Ferdinand II following the 1620 Battle of White Mountain and during the Thirty Years' War.

The Hussite tradition continues in the Moravian Church, Unity of the Brethren and, since the dissolution of Austria-Hungary, by the re-founded Czechoslovak Hussite Church.[3] The revived legacy of Saints Cyril and Methodius also continues in both the Orthodox Church in the Czech Lands and the Apostolic Exarchate of the Greek Catholic Church in the Czech Republic.

History

[edit]The Hussite movement began in the Kingdom of Bohemia and quickly spread throughout the remaining Lands of the Bohemian Crown, including Moravia and Silesia. It also made inroads into the northern parts of the Kingdom of Hungary (now Slovakia), but was rejected and gained infamy for the plundering behaviour of the Hussite soldiers.[4][5][6][7] There were also small temporary communities in Poland-Lithuania and Transylvania which moved to Bohemia after being confronted with religious intolerance. It was a regional movement that failed to expand farther. Hussites emerged as a majority Utraquist movement with a significant Taborite faction, and smaller regional ones that included Adamites, Orebites and Orphans.

Major Hussite theologians included Petr Chelčický and Jerome of Prague. A number of Czech national heroes were Hussite, including Jan Žižka, who led a fierce resistance to five consecutive crusades proclaimed on Hussite Bohemia by the Papacy. Hussites were one of the most important forerunners of the Protestant Reformation. This predominantly religious movement was propelled by social issues and strengthened Czech national awareness.

Hus's death

[edit]

The Council of Constance lured Jan Hus in with a letter of indemnity, then tried him for heresy and put him to death at the stake on 6 July 1415.[2]

The arrest of Hus in 1414 caused considerable resentment in Czech lands. The authorities of both countries appealed urgently and repeatedly to King Sigismund to release Jan Hus.

When news of his death at the Council of Constance arrived, disturbances broke out, directed primarily against the clergy and especially against the monks. Even the Archbishop narrowly escaped from the effects of this popular anger. The treatment of Hus was felt to be a disgrace inflicted upon the whole country and his death was seen as a criminal act. King Wenceslaus IV., prompted by his grudge against Sigismund, at first gave free vent to his indignation at the course of events in Constance. His wife openly favoured the friends of Hus. Avowed Hussites stood at the head of the government.

A league was formed by certain lords,[who?] who pledged themselves to protect the free preaching of the Gospel upon all their possessions and estates and to obey the power of the Bishops only where their orders accorded with the injunctions of the Bible. The university would arbitrate any disputed points. The entire Hussite nobility joined the league. Other than verbal protest of the council's treatment of Hus, there was little evidence of any actions taken by the nobility until 1417. At that point several of the lesser nobility and some barons, signatories of the 1415 protest letter, removed Catholic priests from their parishes, replacing them with priests willing to give communion in both wine and bread. The chalice of wine became the central identifying symbol of the Hussite movement.[8] If the king had joined, its resolutions would have received the sanction of the law; but he refused, and approached the newly formed Roman Catholic League of lords, whose members pledged themselves to support the king, the Catholic Church, and the council. The prospect of a civil war began to emerge.

Prior to becoming pope, Martin V, then known as Cardinal Otto of Colonna had attacked Hus with relentless severity. He energetically resumed the battle against Hus's teaching after the enactments of the Council of Constance. He wished to eradicate completely the doctrine of Hus, for which purpose the co-operation of King Wenceslaus had to be obtained.[citation needed] In 1418, Sigismund succeeded in winning his brother over to the standpoint of the council by pointing out the inevitability of a religious war if the heretics in Bohemia found further protection.[citation needed] Hussite statesmen and army leaders had to leave the country and Roman Catholic priests were reinstated. These measures caused a general commotion which hastened the death of King Wenceslaus by a paralytic stroke in 1419.[citation needed] His heir was Sigismund.

Hussite Wars (1419–1434)

[edit]

The news of the death of King Wenceslaus in 1419 produced a great commotion among the people of Prague. A revolution swept over the country: churches and monasteries were destroyed, and church property was seized by the Hussite nobility. It was then, and remained till much later, in question whether Bohemia was a hereditary or an elective monarchy, especially as the line through which Sigismund claimed the throne had accepted that the Kingdom of Bohemia was an elective monarchy elected by the nobles, and thus the regent of the kingdom (Čeněk of Wartenberg) also explicitly stated that Sigismund had not been elected as reason for Sigismund's claim to not be accepted. Sigismund could get possession of "his" kingdom only by force of arms. Pope Martin V called upon Catholics of the West to take up arms against the Hussites, declaring a crusade, and twelve years of warfare followed.

The Hussites initially campaigned defensively, but after 1427 they assumed the offensive. Apart from their religious aims, they fought for the national interests of the Czechs. The moderate and radical parties were united, and they not only repelled the attacks of the army of crusaders but crossed the borders into neighboring countries. On March 23, 1430, Joan of Arc dictated a letter[9] that threatened to lead a crusading army against the Hussites unless they returned to the Catholic faith, but her capture by English and Burgundian troops two months later would keep her from carrying out this threat.

Council of Basel and Compacta of Prague

[edit]Eventually, the opponents of the Hussites found themselves forced to consider an amicable settlement. The Hussites were sent an invitation to attend the ecumenical Council of Basel on October 15, 1431.[10] The discussions began on 10 January 1432, focusing chiefly on the four articles of Prague. No agreement emerged. After repeated negotiations between the Basel Council and Bohemia, a Bohemian–Moravian state assembly in Prague accepted the "Compactata" of Prague on 30 November 1433. The agreement granted communion in both kinds to all who desired it, but with the understanding that Christ was entirely present in each kind, though on the condition that the rest of the Hussite reforms would no longer be emphasised.[10] Free preaching was granted conditionally: the Church hierarchy had to approve and place priests, and the power of the bishop must be considered. The article which prohibited the secular power of the clergy was almost reversed.

The Taborites refused to conform. The Calixtines united with the Roman Catholics and destroyed the Taborites at the Battle of Lipany on 30 May 1434.[11] From that time, the Taborites lost their importance, though the Hussite movement would continue in Poland for another five years, until the Royalist forces of Poland defeated the Polish Hussites at the Battle of Grotniki. The state assembly of Jihlava in 1436 confirmed the "Compactata" and gave them the sanction of law. This accomplished the reconciliation of Bohemia with Rome and the Western Church, and at last Sigismund obtained possession of the Bohemian crown.[11] His reactionary measures caused a ferment in the whole country, but he died in 1437. The state assembly in Prague rejected Wyclif's doctrine of the Lord's Supper, which was obnoxious to the Utraquists, as heresy in 1444. Most of the Taborites now went over to the party of the Utraquists; the rest joined the "Brothers of the Law of Christ" (Latin: "Unitas Fratrum") (see history of the Moravian Church).

Hussite Bohemia, Luther and the Reformation (1434–1618)

[edit]

In 1462, Pope Pius II declared the "Compacta" null and void, prohibited communion in both kinds, and acknowledged King George of Podebrady as king on condition that he would promise an unconditional harmony with the Roman Church. This he refused, leading to the Bohemian–Hungarian War (1468–1478). His successor, King Vladislaus II, favored the Roman Catholics and proceeded against some zealous clergymen of the Calixtines. The troubles of the Utraquists increased from year to year. In 1485, at the Diet of Kutná Hora, an agreement was made between the Roman Catholics and Utraquists that lasted for thirty-one years. It was only later, at the Diet of 1512, that the equal rights of both religions were permanently established. The appearance of Martin Luther was hailed by the Utraquist clergy, and Luther himself was astonished to find so many points of agreement between the doctrines of Hus and his own. But not all Utraquists approved of the German Reformation; a schism arose among them, and a number of them returned to the Roman doctrine, while other elements had organised the "Unitas Fratrum" already in 1457.

Bohemian Revolt and harsh persecution under the Habsburgs (1618–1918)

[edit]Under Emperor Maximilian II, the Bohemian state assembly established the Confessio Bohemica, upon which Lutherans, Reformed, and Bohemian Brethren agreed. From that time forward Hussitism began to die out. After the Battle of White Mountain on 8 November 1620 the Roman Catholic Faith was re-established with vigour, which fundamentally changed the religious conditions of the Czech lands.

Leaders and members of Unitas Fratrum were forced to choose to either leave the southeastern principalities of what was the Holy Roman Empire (mainly Austria, Hungary, Bohemia, Moravia and parts of Germany and its states), or to practice their beliefs secretly. As a result, members were forced underground and dispersed across northwestern Europe. The largest remaining communities of the Brethren were located in Lissa (Leszno) in Poland, which had historically strong ties with the Czechs, and in small, isolated groups in Moravia. Some, among them Jan Amos Comenius, fled to western Europe, mainly the Low Countries. A settlement of Hussites in Herrnhut, Saxony, now Germany, in 1722 caused the emergence of the Moravian Church.

Post-Habsburg era and modern times (1918–present)

[edit]

In 1918, as a result of World War I, the Czech lands regained independence from Austria-Hungary controlled by the Habsburg monarchy as Czechoslovakia (due to Masaryk and Czechoslovak legions with Hussite tradition, in the name of the troops).[12]

Today, the Hussite tradition is represented in the Moravian Church, Unity of the Brethren, and Czechoslovak Hussite Church.[3][13]

Factions

[edit]This section needs additional citations for verification. (November 2017) |

Hussitism organised itself during the years 1415–1419. Hussites were not a unitary movement, but a diverse one with multiple factions that held different views and opposed each other in the Hussite Wars. From the beginning, there formed two parties, with a smaller number of people withdrawing from both parties around the pacifist Petr Chelčický, whose teachings would form the foundation of the Unitas Fratrum. Hussites can be divided into:

Moderates

[edit]The more conservative Hussites (the moderate party, or Utraquists), who followed Hus more closely, sought to conduct reform while leaving the whole hierarchical and liturgical order of the Church untouched.[14]

Their programme is contained in the Four Articles of Prague, which were written by Jacob of Mies and agreed upon in July 1420, promulgated in the Latin, Czech, and German languages. They can be summarised as follows: [15]

- Free preaching of the Word of God throughout the Kingdom of Bohemia and the Margravate of Moravia.

- Celebration of the communion under both kinds (bread and wine to priests and laity alike)

- The removal of secular power from the clergy.

- Secular punishment for mortal sins among clergy and laity alike.

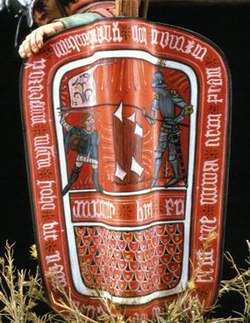

The views of the moderate Hussites were widely represented at the university and among the citizens of Prague; they were therefore called the Prague Party, but also Calixtines (Latin calix chalice) or Utraquists (Latin utraque both), because they emphasized the second article of Prague, and the chalice became their emblem.

Radicals

[edit]The more radical parties, the Taborites, Orebites and Orphans, identified itself more boldly with the doctrines of John Wycliffe, sharing his passionate hatred of the monastic clergy, and his desire to return the Church to its supposed condition during the time of the apostles. This required the removal of the existing hierarchy and the secularisation of ecclesiastical possessions. Above all they clung to Wycliffe's doctrine of the Lord's Supper, denying transubstantiation,[16] and this is the principal point by which they are distinguished from the moderate party, the Utraquists.

The radicals preached the "sufficientia legis Christi"—the divine law (i.e. the Bible) is the sole rule and canon for human society, not only in the church, but also in political and civil matters. They rejected therefore, as early as 1416, everything that they believed had no basis in the Bible, such as the veneration of saints and images, fasts, superfluous holidays, the oath, intercession for the dead, auricular Confession, indulgences, the sacraments of Confirmation and the Anointing of the Sick, and chose their own priests.

The radicals had their gathering-places all around the country. Their first armed assault fell on the small town of Ústí, on the river Lužnice, south of Prague (today's Sezimovo Ústí). However, as the place did not prove to be defensible, they settled in the remains of an older town upon a hill not far away and founded a new town, which they named Tábor (a play on words, as "Tábor" not only meant "camp" or "encampment" in Czech,[17] but is also the traditional name of the mountain on which Jesus was expected to return; see Mark 13); hence they were called Táborité (Taborites). They comprised the essential force of the radical Hussites.

Their aim was to destroy the enemies of the law of God, and to defend his kingdom (which had been expected to come in a short time) by the sword. Their end-of-world visions did not come true. In order to preserve their settlement and spread their ideology, they waged bloody wars; in the beginning they observed a strict regime, inflicting the severest punishment equally for murder, as for less severe faults as adultery, perjury, and usury, and also tried to apply rigid Biblical standards to the social order of the time. The Taborites usually had the support of the Orebites (later called Orphans), an eastern Bohemian sect of Hussitism based in Hradec Králové.

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Dvornik, F. (1964). "The Significance of the Missions of Cyril and Methodius". Slavic Review. 23 (2): 195–211. doi:10.2307/2492930. JSTOR 2492930. S2CID 163378481.

- ^ a b Oxford Dictionary of the Christian Church (Oxford University Press 2005 ISBN 978-0-19-280290-3), article "Constance, Council of"

- ^ a b Nĕmec, Ludvík "The Czechoslovak heresy and schism: the emergence of a national Czechoslovak church," American Philosophical Society, Philadelphia, 1975, ISBN 0-87169-651-7

- ^ Spiesz et al. 2006, p. 52.

- ^ Bartl 2002, p. 45.

- ^ Kirschbaum 2005, p. 48.

- ^ Spiesz et al. 2006, p. 53.

- ^ John Klassen, "The Nobility and the Making of the Hussite Revolution" (East European Quarterly/Columbia University Press, 1978)

- ^ "Joan of Arc's Letter to the Hussites (March 23, 1430)". archive.joan-of-arc.org.

- ^ a b Fudge, Thomas A. (1998). The magnificent ride : the first reformation in Hussite Bohemia. Internet Archive. Aldershot, Hants ; Brookfield, Vt. : Ashgate. ISBN 978-1-85928-372-1.

- ^ a b Malcolm Lambert (1992). Medieval heresy. Internet Archive. B. Blackwell. ISBN 978-0-631-17431-8.

- ^ PRECLÍK, Vratislav. Masaryk a legie (Masaryk and legions), váz. kniha, 219 str., vydalo nakladatelství Paris Karviná, Žižkova 2379 (734 01 Karviná) ve spolupráci s Masarykovým demokratickým hnutím (Masaryk Democratic Movement), 2019, ISBN 978-80-87173-47-3, pp. 17–25, 33–45, 70–76, 159–184, 187–199

- ^ Sheldon, Addison Erwin; Sellers, James Lee; Olson, James C. (1993). Nebraska History, Volume 74. Nebraska State Historical Society. p. 151.

- ^ "Utraquism’s faithfulness to the Prague Use of the Roman rite…(was) an intentional symbol of Utraquism’s self-understanding as a continuing part of the Western Catholic Church." Holeton, David R.; Vlhová-Wörner, Hana; Bílková, Milena (2007). "The Trope Gregorius presul meritis in Bohemian Tradition: Its Origins, Development, Liturgical Function and Illustration" (PDF). Bohemian Reformation and Religious Practice. 6: 215–246. Retrieved 18 November 2023.

- ^ "The Four Articles of Prague". John Hus: Apostle of Truth.

- ^ Cook, William R. (1973). "John Wyclif and Hussite Theology 1415–1436". Church History. 42 (3): 335–349. doi:10.2307/3164390. ISSN 0009-6407. JSTOR 3164390.

- ^ Profous, Antonín (1957). Místní jména v Čechách: Jejich vznik, původní význam a změny; part 4, S–Ž. Prague, Czechoslovakia: Czechoslovak Academy of Sciences.

Bibliography

[edit]- Michael Van Dussen and Pavel Soukup (eds.). 2020. A Companion to the Hussites. Brill.

- Kaminsky, H. (1967) A History of the Hussite Revolution University of California Press: Los Angeles.

- Fudge, Thomas A. (1998) The Magnificent Ride: The First Reformation in Hussite Bohemia, Ashgate.

- Fudge, Thomas A. (2002) The Crusade against Heretics in Bohemia, Ashgate.

- Ondřej, Brodu, "Traktát mistra Ondřeje z Brodu o původu husitů" (Latin: "Visiones Ioannis, archiepiscopi Pragensis, et earundem explicaciones, alias Tractatus de origine Hussitarum"), Muzem husitského revolučního hnutí, Tábor, 1980, OCLC 28333729 in (in Latin) with introduction in (in Czech)

- Mathies, Christiane, "Kurfürstenbund und Königtum in der Zeit der Hussitenkriege: die kurfürstliche Reichspolitik gegen Sigmund im Kraftzentrum Mittelrhein," Selbstverlag der Gesellschaft für Mittelrheinische Kirchengeschichte, Mainz, 1978, OCLC 05410832 in (in German)

- Bezold, Friedrich von, "König Sigmund und die Reichskriege gegen die Husiten," G. Olms, Hildesheim, 1978, ISBN 3-487-05967-3 in (in German)

- Denis, Ernest, "Huss et la Guerre des Hussites," AMS Press, New York, 1978, ISBN 0-404-16126-X in (in French)

- Klassen, John (1998) "Hus, the Hussites, and Bohemia" in New Cambridge Medieval History Cambridge University Press: Cambridge.

- Macek, Josef, "Jean Huss et les Traditions Hussites: XVe–XIXe siècles," Plon, Paris, 1973, OCLC 905875 in (in French)

External links

[edit]- "Hussites". A Dictionary of All Religions and Religious Denominations (4th ed.). 1784.

- "Hussites". New International Encyclopedia. 1905.

- Wilhelm, J. (1913). "Hussites". Catholic Encyclopedia.

- Hussite Museum, Tabor

Hussites

View on GrokipediaOrigins

Jan Hus and Early Reforms

Jan Hus, born around 1372 in Husinec in southern Bohemia to a poor peasant family, pursued education at the University of Prague, earning a master's degree in 1396.[3][4] Ordained as a priest circa 1400, he joined the university faculty and in 1402 became preacher at the newly established Bethlehem Chapel in Prague, a venue designed for vernacular preaching to accommodate up to 3,000 listeners.[3][5] There, Hus delivered sermons in Czech, emphasizing moral reform and scriptural fidelity over ritualistic excess, drawing crowds disillusioned by observable clerical abuses such as priests holding multiple benefices while neglecting pastoral duties.[3][6] Hus's early reform efforts targeted specific corrupt practices within the Bohemian church, including simony—the sale of ecclesiastical offices—and the peddling of indulgences, which he condemned in sermons as early as 1405 for fostering greed among clergy who funded personal vices like brothels and taverns with proceeds.[4][3] He also critiqued clerical immorality, such as violations of celibacy and fabricated miracles like fake communion wafers, arguing from observed realities in Prague that true salvation hinged on personal piety rather than payments or hierarchies claiming undue spiritual authority.[4][6] These teachings, rooted in empirical grievances against a church where German-dominated officials extracted tithes and dispensations without accountability, resonated amid broader Bohemian resentments toward foreign influence in ecclesiastical and academic institutions.[6][4] By the late 1400s, Hus garnered significant backing from Czech laity and nobility, who viewed his calls for apostolic poverty and national preaching as remedies to the German preponderance at Charles University and in church governance; over 2,000 attended chapel services defying a 1410 papal bull against him, supported by Queen Žofie and numerous nobles.[4][6] This support intensified after the 1409 Kutná Hora decree by King Wenceslas IV, which empowered Czech scholars and elevated Hus's influence, including a brief rectorship, positioning him as a leader in advocating lay access to scripture and clerical accountability.[6][3]Influences from Wycliffe and Bohemian Context

John Wycliffe's theological critiques penetrated Bohemia primarily through Bohemian students who attended Oxford University, where Wycliffe taught from the 1360s onward. These scholars returned with manuscripts challenging papal supremacy, advocating the primacy of scripture over church tradition, and questioning doctrines like transubstantiation.[7] By the late 14th century, Wycliffe's works fueled debates at the University of Prague, reinforcing indigenous reform sentiments originating under Emperor Charles IV.[8] Key ideas included the church's spiritual rather than temporal authority and predestination, which undermined the causal chain of papal indulgences and clerical wealth accumulation as means of salvation.[9] Encouraged by Queen Anne of Bohemia, who linked English and Bohemian courts after marrying Richard II in 1382, these transmissions accelerated.[10] Wycliffe's writings were selectively translated into Czech vernacular texts by the early 1400s, enabling wider lay access and amplifying critiques of ecclesiastical hierarchy divorced from biblical warrant.[11] Local Bohemian conditions exacerbated these imported ideas. The church controlled up to 50 percent of arable land by the early 15th century, deriving substantial income from tithes that burdened peasants and nobility alike, fostering resentment over unearned extraction without commensurate moral oversight.[12] Linguistic and cultural divides compounded this: many higher clergy, often German-speaking and reliant on Latin liturgy, appeared alien to Czech parishioners, prioritizing institutional wealth over vernacular spiritual guidance.[13] Pre-Hus reformers like Conrad of Waldhausen, preaching in Prague from 1364 to 1369, directly assailed clerical luxury, simony, and moral decay, urging a return to apostolic poverty.[14] His sermons, delivered in the Old Town's Teyn Church, highlighted empirical abuses—priests amassing fortunes while neglecting pastoral duties—setting a precedent for demands to realign church practices with scriptural imperatives rather than temporal power.[15] This convergence of external theology and domestic grievances created fertile ground for intensified reform advocacy, driven by causal pressures from misallocated resources eroding clerical legitimacy.Core Beliefs and Theology

Doctrinal Criticisms of the Catholic Church

The Hussites, led by Jan Hus, mounted scriptural and rational critiques against core Catholic doctrines, asserting the supremacy of the Bible over papal decrees and ecclesiastical traditions. In his 1413 treatise De Ecclesia, Hus defined the true church as the invisible assembly of predestined believers rather than the hierarchical institution under the pope, whom he labeled an "antichrist" if contradicting Christ's teachings.[16] He argued that obedience must follow Scripture above human authorities, citing Acts 5:29—"we must obey God rather than men"—to justify resistance to papal bulls not aligned with biblical precepts, such as bans on vernacular preaching.[16] This positioned papal infallibility as unbiblical, subordinating tradition and canon law solely to scriptural consonance.[16] Central to these criticisms was the rejection of indulgences as exploitative financial mechanisms lacking scriptural warrant, which Hus condemned for substituting monetary payments for genuine repentance and preying on the poor.[17] Influenced by John Wycliffe amid the Western Schism (1378–1417), where rival popes like John XXIII authorized indulgence campaigns in 1412, Hus viewed such practices as evidence of papal overreach, denying the pope's role as Christ's sole vicar and insisting Christ alone headed the church.[17] He extended this to simony—the sale of church offices—and clerical corruption, denouncing priests' moral failings like concubinage and absenteeism as disqualifying them from spiritual authority, prioritizing a priesthood of personal faith and ethical conduct over ritualistic hierarchy.[18] Hus's reforms advanced vernacular Bible access, promoting Czech translations to enable laypeople's direct engagement with Scripture, countering the church's monopolized interpretation that sustained doctrinal errors.[17] While critiquing sacramental withholding—such as denying the laity communion under both kinds as contrary to biblical precedent—he affirmed transubstantiation without radical repudiation, grounding debates in early church fathers and empirical alignment with scriptural realism over speculative philosophy.[19] These positions, rooted in first-hand scriptural exegesis over institutional precedent, exposed causal links between hierarchical entanglements and moral decay, fostering a theology of individual conscience accountable to divine law.[16]Utraquism and Sacramental Practices

Utraquism, derived from the Latin sub utraque specie (under both kinds), referred to the Hussite insistence that laypeople receive Holy Communion under both the species of bread and wine, rather than solely the bread as permitted by late medieval Catholic custom. This practice gained prominence after Jan Hus's execution, when Jakoubek of Stříbro (Jacobellus de Misa) advanced it as a scriptural imperative around 1414–1415, arguing it restored the fullness of Christ's institution at the Last Supper.[20][21] Unlike broader Hussite critiques of indulgences or simony, utraquism targeted a specific liturgical withholding, positing that denying the chalice to laity diminished the sacrament's efficacy and contradicted apostolic norms.[22] Hussites grounded utraquism in biblical texts, particularly John 6:53–54, where Jesus states, "Truly, truly, I say to you, unless you eat the flesh of the Son of man and drink his blood, you have no life in you," interpreting this as mandating reception of both elements for spiritual nourishment.[22] They further appealed to early Church Fathers and patristic evidence of lay communion under both kinds, such as descriptions in Cyril of Jerusalem's Catechetical Lectures, to claim a return to primitive purity unmarred by later medieval restrictions.[23] This stood in direct opposition to the Council of Constance's decree in its thirteenth session on 15 June 1415, which explicitly rejected lay access to the chalice, affirming the doctrine of concomitance—that Christ's full presence in either species sufficed—and citing risks of spillage or irreverence as practical justifications for the ban.[24] The chalice emerged as a potent symbol of egalitarian access to grace, embodying the Hussite view that all baptized believers, irrespective of clerical status, stood equally before God in sacramental life, thereby challenging perceived hierarchical privileges in the priesthood's exclusive handling of the wine.[25] In Bohemia, this emblem proliferated rapidly after 1415, appearing on seals, banners, and altars as utraquism spread among urban laity and priests, with estimates indicating over half of Prague's parishes adopting it by 1420 amid growing defiance of conciliar rulings.[26] Catholic critics countered that utraquism eroded the priestly mediation rooted in Old Testament typology, where blood rituals underscored sacrificial distinction, potentially blurring lay and ordained roles while ignoring concomitance's theological sufficiency.[24] Hussites rebutted such charges by affirming transubstantiation and priestly ordination, defending utraquism solely as a corrective to post-apostolic accretions, not a rejection of sacramental ontology, thus preserving core Catholic doctrines while prioritizing scriptural and patristic fidelity.[27][28]Radical Interpretations Among Extremists

The Taborites, a radical Hussite faction emerging around 1419, embraced chiliastic doctrines anticipating the imminent Last Judgment and establishment of Christ's earthly kingdom, interpreting biblical prophecies such as those in Revelation as signaling the destruction of corrupt ecclesiastical and secular powers.[29] This apocalyptic fervor, rooted in selective literal readings of Old and New Testament eschatology, causally spurred social upheavals by framing existing authorities as agents of the Antichrist, thereby justifying the repudiation of feudal oaths, tithes, and taxation systems as tools of satanic dominion.[30] Catholic chroniclers, including those aligned with papal crusading efforts, condemned these views as heretical distortions that incited anarchy, contrasting them with orthodox eschatology which deferred millennial fulfillment to the afterlife.[31] Such radical interpretations extended to sacramental practices, where extremists debated infant baptism's efficacy, advocating in isolated cases for adult believer's baptism to ensure conscious faith amid free will assertions against perceived predestinarian elements in Catholic doctrine.[32] While later Protestant critics likened these positions to Anabaptist precursors, empirical evidence indicates limited implementation among Taborites, confined to fringe groups like the Adamites rather than widespread rejection, with most retaining infant baptism albeit with heightened emphasis on personal regeneration. Defenders within the movement portrayed these debates as restorations of primitive Christianity, yet Catholic theologians at councils such as Basel decried them as Pelagian errors undermining sacramental grace.[33] Controversies arose from the Taborites' rigorous Old Testament literalism, which prompted accusations of Judaizing tendencies through emulation of Mosaic communalism and ritual purity laws, exacerbating anti-clerical violence against perceived "carnal" priests as false prophets.[34] Papal bulls and inquisitorial records from the 1420s framed this as a reversion to Jewish legalism, antithetical to New Testament fulfillment in Christ, though radical apologists countered that it represented zealous purification of a church infiltrated by Antichrist's deceits.[35] These theological extremes, while energizing resistance to perceived corruption, empirically correlated with internal disruptions, as chiliastic timelines failed to materialize, eroding cohesion by the mid-1420s.[30]Internal Factions

Utraquists and Moderate Reformers

The Utraquists constituted the moderate wing of the Hussite movement, primarily comprising university masters and clergy in Prague who advocated for ecclesiastical reforms centered on the restoration of communion in both kinds for the laity, known as sub utraque specie.[36] This practice, justified theologically by figures such as Jakoubek of Stříbro, drew from scriptural interpretations emphasizing Christ's institution of the Eucharist with both bread and wine, as described in the Gospels, and early patristic precedents before the medieval restriction to the host for lay recipients.[36] Jakoubek, a prominent disciple of Jan Hus, began promoting utraquism vigorously around 1414, arguing it as a scriptural mandate rather than an innovation, while Hus himself expressed caution during his lifetime.[1] Utraquist leaders, including Jakoubek, envisioned a reformed national church in Bohemia under the oversight of the king and local synods, retaining elements of hierarchical structure such as priestly ordination and ecclesiastical courts, but purging perceived abuses like simony and clerical immorality.[36] They opposed the radical social doctrines emerging among Taborite factions, particularly the advocacy for communal ownership of property and rejection of oaths, viewing these as deviations from apostolic order and potential sources of anarchy rather than fidelity to primitive Christianity.[4] This stance reflected a pragmatic approach prioritizing doctrinal purity in sacramental practice over wholesale societal restructuring, fostering alliances with Bohemian nobility who sought autonomy from papal interference without upending feudal hierarchies.[37] Intellectually, the Utraquists maintained continuity with Hus's critiques of indulgences and papal authority, systematizing them into demands like the Four Articles of Prague, but emphasized negotiated implementation over militant absolutism.[21] Jakoubek's writings, such as his 1420 affirmations on liturgical adiaphora—deeming non-essential ceremonies permissible if free from superstition—underscored a willingness to compromise on forms while insisting on core reforms.[36] Radicals accused them of opportunism for retaining aspects of Catholic governance, yet this moderation enabled the Utraquists to influence subsequent agreements like the Compactata, which secured legal recognition for utraquism in Bohemia by 1436.[38] Their focus on ecclesiastical renewal without iconoclasm or pacifist extremes positioned them as a stabilizing force amid factional tensions.[4]Taborites and Radical Communalists

The Taborites constituted the most militant radical wing of the Hussite movement, coalescing in southern Bohemia during late 1419 amid escalating religious fervor following the Defenestration of Prague. They established fortified hilltop settlements, notably at Tábor, drawing thousands of peasants, artisans, and disaffected clergy who sought to emulate the early Christian community described in Acts 2:44–45 by instituting communal ownership of property and abolishing private land holdings within their enclaves. Initial leadership included priestly figures such as Mikuláš of Husině, who advocated for these practices as a return to apostolic purity, with gold from local mines distributed collectively to sustain the group rather than accumulated for individual gain. This egalitarianism, however, was enforced through communal decrees rather than voluntary consensus, reflecting a rejection of feudal hierarchies that prioritized spiritual renewal over sustained social stability.[33][35] Theologically, Taborite extremism stemmed from chiliastic apocalypticism, interpreting biblical prophecies—particularly from Revelation and Daniel—as heralding an imminent divine kingdom that nullified secular oaths, including feudal loyalties and oaths of allegiance to lords or the crown. Early adherents, influenced by pre-Hus reformist ideas against swearing oaths or resisting evil violently, initially embraced non-violence and withdrawal from worldly corruption, envisioning Tábor as a "New Jerusalem" where lay preachers supplanted clerical authority and sacraments were simplified to utraquism extended toward rejection of transubstantiation in favor of symbolic presence. Yet this pacifist phase rapidly contradicted itself; unmet eschatological expectations by early 1420 prompted a pivot to armed self-defense and proselytizing expeditions, justified as purgative violence against Antichrist's agents in the Catholic hierarchy and feudal elites. Jan Žižka, a one-eyed nobleman who aligned with the Taborites around 1420 after Mikuláš's death, formalized this shift by organizing peasant-soldier armies into disciplined units, blending radical theology with pragmatic warfare tactics like wagon fortresses.[29][35][34] These contradictions— from chiliastic pacifism to offensive holy war—exposed causal tensions in Taborite ideology: apocalyptic egalitarianism, while rhetorically liberating peasants from serfdom, empirically fostered internal factionalism and external raids that plundered villages for supplies and coerced conversions, often involving the desecration of churches and destruction of religious icons deemed idolatrous. Catholic chroniclers, such as those aligned with Sigismund's court, portrayed Taborites as heretical revolutionaries whose communal experiments eroded feudal order, leading to widespread atrocities like forced baptisms and property seizures that alienated potential allies. Taborites, conversely, framed themselves as God's elect warriors purging corruption, yet this self-justification masked how unfulfilled millennial hopes bred betrayals, such as Žižka's disputes with Tábor's priests over military autonomy, prefiguring the faction's later defeat by moderate Utraquists at Lipany in 1434. Far from an unalloyed model of virtuous communalism, the Taborite blend of theological radicalism and social leveling prioritized destructive zeal over enduring cohesion, yielding short-term military successes but long-term ideological fragmentation.[39][40][29]Outbreak of Conflict

Execution of Hus and Defenestration of Prague

Jan Hus, a Czech priest and reformer, was summoned to the Council of Constance in late 1414 to defend his teachings against charges of heresy. Promised safe conduct by Holy Roman Emperor Sigismund, Hus arrived in November 1414 but was imprisoned shortly thereafter, despite the guarantee.[41][42] The council conducted trials from March to June 1415, condemning him for doctrines deemed heretical, including criticisms of papal authority and indulgences; Hus refused to recant. On July 6, 1415, he was degraded from priesthood and burned at the stake.[43] The execution violated the safe conduct empirically, though council apologists later argued no such protection applied to heretics under canon law.[44] News of Hus's death reached Prague by late July 1415, igniting riots against perceived Catholic overreach. Czech students and masters at Charles University staged protests, leading to the expulsion of German faculty and dominance by the Czech nation in university governance. In September 1415, 452 Bohemian and Moravian nobles signed a protest letter to the council, asserting Hus's orthodoxy and innocence, many adorning their seals with chalice symbols representing utraquism—the lay reception of communion in both kinds.[45] These events fueled national resentment, viewing the execution as an injustice against Czech interests and Sigismund's betrayal. Tensions escalated amid King Wenceslaus IV's weak rule and clerical abuses. On July 30, 1419, radical Hussite preacher Jan Želivský led a procession from Prague's Church of Our Lady of the Snows to the New Town Hall, where Catholic councillors had refused to release imprisoned Hussites. The mob stormed the building, seized seven (some accounts state up to thirteen) councillors, and defenestrated them from a high window; the victims died from the fall or subsequent beating by the crowd.[46][47] This violent rejection of royal and ecclesiastical authority symbolized Hussite defiance, precipitating open civil conflict in Bohemia and discrediting Sigismund's claims to the throne following Wenceslaus's death weeks later on August 16.[48]Formation of Hussite Alliances

Following the Defenestration of Prague on July 30, 1419, and King Wenceslaus IV's death on November 16, 1419, Queen Sophia of Bavaria assumed the role of regent in Bohemia, initially providing a stabilizing presence amid rising tensions. Sympathetic to reformist preaching influenced by Jan Hus, she had attended sermons at Bethlehem Chapel and offered protection to figures like Jakoubek of Stříbro, fostering an environment where moderate Hussite ideas gained traction among nobles and burghers. However, her employment of mercenaries to maintain order clashed with radical elements in November 1419, highlighting early fractures but also underscoring the ad-hoc alliances emerging between urban reformers, sympathetic clergy, and local lords to safeguard utraquist practices against external threats.[49][50] The impending claim of Sigismund, Wenceslaus's half-brother, to the Bohemian throne intensified organizational responses, particularly after Pope Martin V's crusade bull on March 1, 1420, which framed Hussites as heretics warranting extermination. Bohemian nobles, wary of Sigismund's complicity in Hus's 1415 execution and his alignment with papal forces, refused his coronation upon his arrival in Prague in June 1420, prompting the formation of defensive leagues uniting lords "sub una" (under one banner) with urban militias and rural sympathizers. These coalitions, distinct from later formalized factions, emphasized collective defense of Bohemian liberties and sacramental reforms, drawing on widespread discontent with ecclesiastical abuses.[51][52] Hussitism's appeal extended beyond Prague through itinerant preachers who disseminated utraquist doctrines, leading to verifiable expansion in rural Bohemia by early 1420, marked by the proliferation of chalice-emblazoned banners as symbols of communal adherence. Villages and smaller towns adopted these emblems, signaling alignment with the movement's core demand for lay communion in both kinds, which galvanized peasant and knightly support against perceived Catholic aggression. This grassroots spread reinforced the alliances' breadth, transforming localized protests into a proto-national resistance network.[53] Internally, early alliances grappled with the morality of violence; original Hussite thought, echoing Hus's emphasis on non-resistance to evil, leaned toward pacifism, prohibiting offensive warfare or harm to persecutors. Yet, escalating papal threats and Sigismund's military overtures compelled a doctrinal pivot toward justified self-defense, articulated by figures like Jakoubek as a biblical imperative against tyrannical oppression, allowing coalitions to arm without forsaking reformist ethics. This evolution, while contentious, solidified the alliances' resolve ahead of direct confrontations.[54][55]Hussite Wars and Military Campaigns

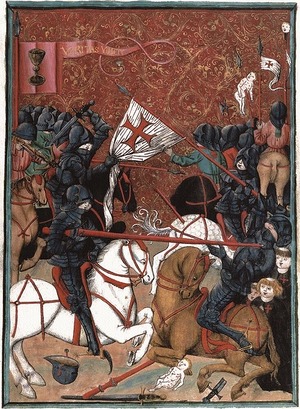

Key Battles and Defensive Innovations

Jan Žižka, a key Hussite commander, developed the wagenburg or wagon fort tactic, utilizing reinforced carts chained together to form a mobile fortress with loopholes for crossbows, handgonnes, and small cannons, enabling peasant infantry to withstand and counter cavalry assaults effectively.[56] This innovation shifted warfare toward combined arms, emphasizing disciplined infantry over knightly charges, with flails proving particularly lethal against armored foes due to their ability to concuss and unhorse knights.[57] The tabors' success stemmed from pragmatic integration of early gunpowder weapons and strict training, allowing outnumbered forces to repel superior numbers in open terrain.[58] The Battle of Sudoměř on 25 March 1420 exemplified these tactics' early efficacy; Žižka, leading a Hussite detachment en route to Tábor, repelled a larger Catholic force under John of Chlum, inflicting heavy casualties through defensive wagon formations and firepower despite being outnumbered.[59] This victory, the first pitched engagement of the Hussite Wars, preserved the movement's southern strongholds and validated Žižka's emphasis on mobility and fortification over traditional melee reliance.[55] At the Battle of Kutná Hora on 21 December 1421, Žižka's approximately 12,000 troops, including Taborite radicals, faced 30,000 German and Hungarian imperial forces; employing wagons both defensively and offensively, the Hussites shattered enemy lines, capturing the silver-rich city and routing Sigismund's allies.[58] These engagements contributed to the failure of five papal crusades, as wagon forts neutralized numerical and qualitative advantages, forcing crusaders into costly assaults against entrenched fire.[55] While effective, such tactics necessitated scorched-earth retreats to starve pursuers, involving village burnings that blurred defensive imperatives with punitive destruction.[56]Papal Crusades and Hussite Victories

In response to the execution of Jan Hus and the escalating unrest in Bohemia, Pope Martin V proclaimed the first crusade against the Hussites on March 1, 1420, via the bull Omnium Plasmatoris Domini, offering plenary indulgences to participants as incentives for a holy war against perceived heresy.[60][61] This initiated a series of five papal crusades spanning 1420 to 1431, framed by the papacy as a defensive imperative to eradicate doctrinal threats like utraquism and critiques of indulgences, drawing on precedents of anti-heretical campaigns but extending the crusade mechanism to internal European schism.[62] Despite mobilizing forces from across Europe under Holy Roman Emperor Sigismund, these expeditions suffered repeated logistical breakdowns, including poor coordination among disparate contingents from Germany, Hungary, and beyond, compounded by extended supply lines vulnerable to Bohemian terrain and seasonal disruptions.[63] Papal overreach manifested in optimistic recruitment via indulgences, yet causal failures stemmed from underestimating Hussite cohesion and overreliance on feudal levies prone to desertion, revealing the papacy's diminished capacity to enforce spiritual authority through military means post-Avignon and Schism.[64] The inaugural crusade culminated in defeat at Vítkov Hill on July 14, 1420, where approximately 100-200 Hussite defenders under Jan Žižka repelled an assault by Sigismund's 10,000-20,000 crusaders, leveraging the hill's steep elevation for defensive advantage and exploiting attacker disarray from fragmented command.[65] Morale collapse among the crusaders, fueled by Hussite resolve rooted in defensive interpretations of scripture against perceived papal corruption, underscored how ideological commitment offset numerical inferiority.[66] Similarly, the fifth crusade ended without engagement at Domažlice on August 14, 1431, as Cardinal Cesarini's multinational force of up to 100,000—plagued by prior setbacks and inadequate provisioning—dispersed in panic upon encountering Hussite wagon formations and hearing their choral hymns, interpreted by contemporaries as divine judgment signaling futility.[67] These empirical routs, absent decisive tactical clashes, highlighted terrain's role in amplifying crusader vulnerabilities and eroding enthusiasm, with desertions reaching critical levels due to unpaid troops and harsh marches.[68] Hussite countermeasures, including retaliatory raids into Austria and Silesia from 1425 onward, intensified controversies over aggression versus preemption; Catholic chroniclers decried these as barbaric incursions plundering monasteries and villages to sustain Bohemian resistance, while Hussite apologists justified them as necessary reprisals against encirclement, drawing on Old Testament models of defensive warfare against oppressors.[69] Such actions exacerbated fractures among German princes, many of whom withheld full commitment to Sigismund's campaigns due to rivalries and wariness of Bohemian destabilization spilling into their territories, exposing the Holy Roman Empire's political disunity as a limiter on papal ambitions.[70] The cumulative failures precipitated a tangible erosion of papal prestige, as repeated defeats without territorial gains undermined the crusade's aura of divine sanction, prompting secular rulers to prioritize pragmatic diplomacy over eschatological mobilization and foreshadowing conciliar challenges to curial supremacy.[71]Internal Divisions and Battle of Lipany

As the Hussite movement matured, profound ideological fissures emerged between the moderate Utraquists, who primarily sought communion in both kinds (sub utraque specie) and limited ecclesiastical reforms while preserving much of the Catholic framework, and the radical Taborites, who advocated communal property, rejection of oaths, and a more egalitarian reinterpretation of scripture that challenged hierarchical authority.[72][73] The Taborites' intransigence, rooted in apocalyptic expectations and refusal to countenance partial concessions during ongoing negotiations at the Council of Basel, increasingly alienated Utraquist nobles and urban leaders who favored pragmatic alliances to secure Bohemian autonomy.[74] This radical stance, which prioritized purist doctrinal adherence over strategic flexibility, fostered a causal dynamic where ideological purity precipitated isolation, as moderates perceived the Taborites' militancy—ironically evolved from early pacifist ideals of non-resistance to worldly powers—as a threat to sustainable reform.[72] These divisions culminated in open conflict in 1434, when Utraquist forces under Diviš Bořek of Miletínek allied with Catholic contingents to confront the Taborite army led by Prokop the Great (Prokop Holý).[73] On May 30, 1434, near Lipany in central Bohemia, approximately 40 kilometers east of Prague, the two sides clashed in a decisive engagement.[74][73] The Taborites, numbering around 10,000-12,000 infantry-heavy troops reliant on wagon-fort tactics, were outmaneuvered by the Utraquist-Catholic coalition's superior cavalry, which disrupted their defensive formations and triggered a rout.[74] Prokop the Great and Prokop the Lesser perished during a final stand at the wagons, while Taborite losses exceeded 1,000 killed in the melee, with the battlefield left strewn across roughly 1,500 fallen radicals in total.[73][74] The Lipany debacle marked the effective collapse of Taborite dominance, as surviving radicals scattered and their stronghold at Tábor entered a phase of rapid decline, evidenced by the execution of captured leaders and the dissolution of militant communes.[73] This empirical outcome underscored how the radicals' uncompromising posture had engineered their own marginalization, enabling moderates to pivot toward negotiated settlements unencumbered by extremist demands.[74] Historians debate the Taborites' legacy: some portray them as principled martyrs defending egalitarian ideals against co-optation, yet their trajectory—from scriptural pacifism to aggressive warfare—reveals an internal contradiction that amplified factional strife and invited defeat through avoidable escalation.[72][74]Resolution and Compromises

Council of Basel Negotiations

The Council of Basel, convened in 1431, extended a formal invitation to the Hussites on October 15 to participate in negotiations aimed at resolving the Bohemian schism, promising safe conduct to address historical grievances such as the violation of Jan Hus's safe-conduct privileges at the Council of Constance in 1415.[61] A Hussite delegation of fifteen members, including Utraquist leaders like Jan Rokycana, arrived in Basel on January 4, 1433, under these assurances, marking the first direct diplomatic engagement between the council and the reformers after years of crusades.[75] The envoys demanded explicit guarantees against arrest or execution, reflecting deep mistrust rooted in prior papal betrayals, which the council granted to facilitate dialogue amid ongoing military stalemate.[52] Debates commenced shortly after the delegation's arrival, centering on core Hussite tenets such as utraquism—the administration of communion in both kinds to the laity—and the primacy of scriptural authority over ecclesiastical tradition.[76] Hussite spokesmen argued that scripture, not conciliar or papal decrees, held ultimate normative power in doctrinal matters, citing biblical precedents for lay access to the chalice and rejecting traditions lacking explicit scriptural warrant as human accretions. Council theologians countered by defending tradition's coequal role with scripture, viewing Hussite scripturalism as selective and subversive to church unity, though some pragmatic fathers acknowledged the reformers' biblical erudition while insisting on orthodoxy's boundaries.[77] These sessions, spanning January to April 1433, exposed irreconcilable views: Hussites positioned themselves as conscience-bound defenders of apostolic practice, while conciliarists regarded utraquism as a gateway to broader heresy, yet procedural openness allowed public airing without immediate condemnation. Procedural tensions escalated as the Hussites refused to dispatch a larger embassy to Basel, citing persistent assassination fears and logistical burdens, prompting the council to propose relocating substantive talks to neutral Bohemian sites like Břežnov abbey near Prague for mutual security.[75] This shift, agreed upon after the initial delegation's departure in April 1433, reflected pragmatic concessions by the council to avert further bloodshed, interpreted by some contemporaries as capitulation to rebels rather than genuine reform, though others saw it as realistic diplomacy given Hussite military resilience.[61] Hussite intransigence on safe passage underscored their prioritization of personal security over expediency, framing negotiations as a defense of principled dissent against perceived Catholic duplicity, while council records portrayed the Bohemians as obstreperous yet biblically articulate, necessitating compromises to restore imperial authority under Sigismund.[52]Compactata of Prague and Partial Recognition

The Compactata of Prague, concluded on July 5, 1436, at Jihlava (Iglau), represented a negotiated settlement between Utraquist representatives and delegates from the Council of Basel, incorporating modified versions of the Four Articles of Prague originally formulated in 1420.[78] These articles permitted lay communion in both kinds (utraquism) exclusively within Bohemia and Moravia, allowed free preaching of the Gospel as interpreted by scripture, mandated punishment of mortal sins according to divine and human law without exemption for clergy, and addressed the restitution of ecclesiastical properties alienated during the wars, though with ambiguities favoring clerical retention.[2] The terms weakened radical demands by restricting utraquism geographically and subordinating it to conciliar oversight, reflecting empirical concessions to avert total schism while curbing Taborite extremism post-Lipany.[79] Emperor Sigismund ratified the Compactata shortly after their sealing, enabling his coronation as King of Bohemia on July 23, 1436, and temporarily stabilizing the realm by integrating moderate Hussites into the political order.[78] However, enforcement faltered due to resistance from neighboring bishops, who refused to ordain Utraquist clergy as stipulated, leading to ongoing disputes over ecclesiastical authority and priestly legitimacy.[80] Radical factions, including surviving Taborite elements, decried the agreements as a betrayal of Jan Hus's uncompromising stance against papal corruption, arguing that the compromises diluted core reforms like clerical disendowment and universal punishment of vices.[79] Causally, the Compactata fostered a semi-autonomous Utraquist Church that practiced limited utraquism under royal protection, preserving Hussite gains without precipitating broader European schism until later revocations; this arrangement endured legally until 1567, when Bohemian estates removed explicit endorsement from statutes amid rising confessional tensions.[81] The partial recognition underscored the pragmatic boundaries of religious radicalism, as military exhaustion and internal divisions compelled moderates to prioritize territorial integrity over ideological purity.[79]Later Developments and Persecution

Hussite Bohemia Under Native Rule

Following the Compactata of Basel in 1436, which granted Bohemians the right to communion sub utraque specie (in both kinds) as a concession to end the Hussite Wars, the kingdom entered a phase of relative stability under native governance, free from direct foreign monarchical control until 1526.[68] This period began with a regency dominated by Utraquist leaders, culminating in the election of George of Poděbrady as king on March 2, 1458, by the Bohemian estates, including even papal adherents who prioritized national unity over religious schism.[82] As a moderate Utraquist, George sought to implement a policy of religious coexistence, ruling over "two peoples"—Utraquists and Catholics—through pragmatic toleration that preserved the Compactata's provisions while avoiding radical Taborite extremism.[68] His administration emphasized empirical governance, fostering internal peace amid lingering noble rivalries, such as disputes with Hungarian king Matthias Corvinus, who invaded Bohemia in 1468 over succession claims but failed to dislodge George's authority.[83] George's reign (1458–1471) marked verifiable achievements in statecraft, including efforts to organize a Christian league against Ottoman expansion starting in 1462, which aimed to coordinate defensive alliances among European powers to counter Turkish incursions into the Balkans.[82] This initiative reflected causal priorities of collective security over doctrinal purity, though it faced papal opposition due to George's excommunication in 1466 for perceived Hussite sympathies.[83] Economically, Bohemia experienced recovery from the devastations of the prior wars, with agricultural output rebounding and trade networks stabilizing, as evidenced by increased silver mining and urban revitalization in Prague by the late 1460s.[82] Critiques of his rule highlight persistent noble feuds and compromises that diluted stricter Hussite reforms, such as accommodating Catholic rituals to secure papal reconciliation attempts, yet these measures empirically sustained a multi-confessional framework uncommon in contemporary Europe.[68] George's death in 1471 without a confirmed successor led to the election of Vladislas II Jagiellon in May 1471, marking the transition to Jagiellonian rule while upholding Utraquist privileges through alliances with George's supporters.[84] Under the Jagiellonians—Vladislas II (1471–1516) and his son Louis II (1516–1526)—Bohemia maintained native elective monarchy amid ongoing religious accommodations, with Utraquism serving as the de facto state confession alongside tolerated Catholic practices.[84] Vladislas, raised Catholic but reliant on Utraquist estates for revenue, continued George's policy of balanced toleration, convening diets that reinforced the Compactata despite fiscal weaknesses and border skirmishes with Hungary.[84] Doctrinal dilutions accelerated, as Jagiellonian courts increasingly favored Catholic clergy appointments and moderated Hussite liturgy to ease tensions with the Holy Roman Empire, reflecting pragmatic adaptations to external pressures rather than ideological rigor.[68] Economic indicators, including expanded mining yields and agricultural exports, underscored continued post-war stabilization, though noble factionalism persisted, limiting centralized reforms.[85] This era ended abruptly with Louis II's death at the Battle of Mohács on August 29, 1526, against Ottoman forces, paving the way for Habsburg ascendancy and eroding the native rule that had preserved Hussite gains for nearly a century.[84]Habsburg Suppression and Revolt of 1618

The Habsburg dynasty, having inherited the Bohemian crown in 1526 following the Jagiellon extinction, initially extended de facto tolerance to the kingdom's Protestant majority, including Utraquist Hussites whose communion in both kinds was enshrined in the 1436 Compactata of Basel.[86] This accommodation eroded under Holy Roman Emperor Ferdinand II (reigned 1619–1637), an ardent Counter-Reformation advocate who, upon his 1617 election as Bohemian king, pursued policies to curtail Protestant privileges, including interference in church closures and violations of the 1609 Letter of Majesty that had guaranteed religious freedoms to nobles and towns.[87] These measures, viewed by Habsburg supporters as necessary to consolidate imperial authority and combat perceived religious disorder, provoked Bohemian estates—predominantly Protestant, with deep Hussite roots—to resist, culminating in the Second Defenestration of Prague on May 23, 1618, when assembled nobles hurled two Catholic imperial governors and a scribe from a high window of Prague Castle, an act symbolizing defiance against Vienna's centralizing encroachments and echoing earlier Hussite protests.[88] The defenestration ignited the Bohemian Revolt, as Protestant estates deposed Ferdinand II and elected Elector Frederick V of the Palatinate as king, aligning Bohemia with the Protestant Union and escalating into the European Thirty Years' War.[89] Habsburg forces, bolstered by Bavarian and imperial troops under Johann Tserclaes, Count of Tilly, decisively crushed the rebel army at the Battle of White Mountain near Prague on November 8, 1620, inflicting heavy casualties and ending the uprising's military phase.[89] In the reprisals, Ferdinand II orchestrated trials that executed 27 revolt leaders—three nobles, seven knights, and 17 burghers—publicly on Prague's Old Town Square on June 21, 1621, with their bodies quartered and displayed to deter further resistance; Habsburg chroniclers framed these as justice for treason, while Bohemian accounts decried them as martyrdom for defending confessional liberties.[90] Post-White Mountain suppression accelerated re-Catholicization, with Ferdinand II's April 9, 1624, patent mandating Catholicism as the sole permissible faith in Bohemia, effectively nullifying the Compactata and Utraquist practices by banning non-Catholic worship and expelling Protestant clergy.[91] Jesuits, empowered as imperial educators and inquisitors, spearheaded forced conversions through schools, missions, and confiscations, targeting the nobility and urban elites; an estimated five-sixths of the Czech nobility fled into exile, alongside tens of thousands of intellectuals, craftsmen, and burghers, whose properties were seized and redistributed to loyal Catholics, fostering long-term resentment over the erosion of Bohemian autonomy and the infusion of foreign (often German) Catholic settlers.[86][89] This engineered demographic shift, rationalized by Habsburg apologists as restoring ecclesiastical order after a century of Hussite "schism," nonetheless entrenched cycles of ethnic and confessional grievance, as Protestant exiles propagated narratives of tyrannical overreach that undermined imperial legitimacy in Bohemian eyes.[87]Persistence in Exile and Underground

Following the Catholic victory at the Battle of White Mountain on November 8, 1620, which precipitated the re-Catholicization of Bohemia and Moravia, surviving members of the Unity of the Brethren—a radical Hussite offshoot emphasizing communal piety and scriptural authority—fled en masse to evade forced conversion or execution.[92] Approximately 30,000 Brethren emigrated, establishing exile communities in Leszno, Poland, under Polish-Lithuanian tolerance, and later in Prussian territories like East Prussia, where they preserved Hussite liturgical practices such as utraquism (communion in both kinds) amid diaspora isolation.[93] These exiles influenced emerging Pietist movements in Germany by the late 17th century, transmitting ascetic discipline and missionary zeal that later shaped transatlantic Protestant networks without assimilating fully into Lutheran structures.[94] Within Bohemia, non-emigrating Hussite sympathizers adopted a "hidden seed" strategy of clandestine survival from 1620 to roughly 1721, transmitting traditions through familial networks, coded hymns, and secret assemblies in rural areas, evading Habsburg inquisitions that executed or imprisoned thousands.[95] The chalice, emblematic of utraquist demands since the 1420s, persisted as an underground cultural marker, appearing in folk art, gravestone engravings, and vernacular symbols of resistance, signaling latent Hussite identity without overt provocation.[96] Habsburg policies oscillated between suppression and pragmatic concessions; Emperor Joseph II's Patent of Toleration, issued October 13, 1781, permitted limited Protestant worship for Lutherans and Calvinists in Bohemia, indirectly benefiting recatholicized Utraquist remnants by allowing private chapels and burials, though it excluded Anabaptist-like Brethren radicals and required state registration.[97] By the 19th century, Czech nationalism, intertwined with industrialization's urban dislocations and linguistic revivals, spurred renewed interest in Hussite heritage as a bulwark against Germanization, fostering scholarly editions of Hussite texts and public commemorations that reframed exile resilience as ethnic continuity rather than mere survival.[98] This revival, peaking amid the 1848 revolutions, integrated Hussite egalitarianism into proto-socialist critiques of Habsburg feudalism, sustaining underground networks until full legal emancipation in 1918, without restoring pre-1620 communal experiments.[99]Social and Political Impacts

Economic Reforms and Communalism Critiques

The Taborites, the radical faction of the Hussite movement centered in the southern Bohemian stronghold of Tábor founded in 1420, implemented a system of communal ownership encapsulated in the principle omnia sunt communia ("all things are common"), whereby private property was abolished and goods were held collectively.[100] Participants sold personal possessions and contributed wages, spoils from raids, and output from controlled assets like gold mines into communal funds for equal distribution based on need, forming a "communism of consumption" that prioritized sharing over individual accumulation. This experiment initially attracted dispossessed peasants and lower clergy by promising relief from feudal dues and serfdom, enabling short-term mobilization during the Hussite Wars (1419–1434), but lacked mechanisms for sustained production planning or incentives for labor, rendering it dependent on continuous plunder and requisitions.[100] Catholic contemporaries and chroniclers critiqued the Taborite system as tantamount to legalized theft, viewing the forcible seizure and collectivization of ecclesiastical and noble lands as a violation of natural property rights ordained by divine and customary law, rather than genuine reform.[101] Internally, the ideals clashed with practice, as factional raiding parties routinely looted non-adherents—contradicting the universal brotherhood espoused—while secessions by groups like the Adamites (expelled in 1421 after extreme practices) and pacifist Chelčický followers highlighted disillusionment and erosion of cohesion.[100] Empirical outcomes underscored unsustainability: the regime failed to integrate surrounding peasant communes through trade or mutual aid, resorting to coercive exactions that alienated potential supporters and provoked desertions amid resource shortages, culminating in the Taborites' decisive defeat at the Battle of Lipany on May 30, 1434, where approximately 13,000 of their 18,000 troops perished.[100][73] In the war's aftermath, temporary redistributions of confiscated lands to Hussite fighters gave way to the restoration of noble influence, as Utraquist moderates allied with Catholic forces to suppress radicals, thereby entrenching feudal hierarchies and limiting enduring egalitarian gains.[100][68] This reversion illustrated causal limits of enforced communalism without broader institutional buy-in, as noble estates, bolstered by post-war compromises like the Compactata of Basel (1436), reasserted control over agrarian resources previously disrupted by Taborite incursions.[100]National Identity and Anti-German Sentiment

The tensions over national representation at Charles University in Prague escalated in the early 15th century, culminating in King Wenceslaus IV's Decree of Kutná Hora on January 18, 1409. This decree restructured voting rights, granting the Bohemian (Czech) nation three votes while consolidating the remaining three nations—predominantly German-speaking Bavarians, Saxons, and Poles—into one collective vote, effectively shifting control from German-dominated faculties to Czech scholars.[102] Advised by Jan Hus, the measure addressed long-standing grievances where Czech students and masters, comprising a minority despite being the host nation's representatives, faced dominance by immigrant German academics who controlled key decisions and resources.[103] The decree prompted the mass exodus of over 1,000 German masters and students, intensifying ethnic divisions and framing university reform as a precursor to broader national awakening.[104] Hussite ideology increasingly intertwined religious reform with Czech ethnic identity, portraying the movement as a defense against German cultural and ecclesiastical hegemony in Bohemia, a multi-ethnic kingdom where Germans formed a significant urban and mining population—estimated at around 20-30% in border regions and cities like Prague by the early 1400s based on linguistic records and guild memberships.[105] Leaders like Jan Žižka invoked proto-nationalist rhetoric, decrying Sigismund of Luxembourg's crusades as invasions by a "German" king reliant on Teutonic allies, a label used propagandistically by opponents to exploit Bohemian resentments toward imperial interference.[106] Empirical evidence from contemporary chronicles documents targeted expulsions: following the 1419 Prague defenestration, radical Hussites ousted hundreds of German Catholic clergy and burghers from the city, confiscating properties and enforcing Czech-language dominance in administration, actions justified as purging foreign corruption but rooted in linguistic and immigration-based backlash against German settlers who had dominated trade since the 13th-century Ostsiedlung.[107] While these developments fostered a nascent Czech national consciousness—evident in Hussite manifestos like the 1420 Prague Manifesto appealing to "Bohemian" solidarity against external foes—critics, including moderate Utraquists and later historians, contend that the anti-German fervor devolved into xenophobic violence, undermining the universalist aspirations of Christian reform by prioritizing ethnic purity over doctrinal unity.[106] Such expulsions, affecting non-combatant German communities and exacerbating urban depopulation (Prague's population dropped by an estimated 20-30% between 1419 and 1421 per tax rolls), highlighted causal realism in how pre-existing linguistic cleavages, amplified by economic competition in German-held silver mines like Kutná Hora, propelled nationalism but at the cost of internecine strife that prolonged the wars.[107] This ethnic dimension, though instrumental in mobilizing peasant and burgher support, drew condemnation from papal bulls and Sigismund's envoys as heretical barbarism, revealing biases in imperial sources that equated Bohemian resistance with racial treason rather than legitimate self-defense.[105]Legacy and Influence

Precursor to the Protestant Reformation

Martin Luther encountered the writings of Jan Hus during the Leipzig Debate of July 1519, where he publicly declared, "I am a Hussite" in defense of certain articles condemned at the Council of Constance, affirming Hus's evangelical teachings as aligned with Scripture.[108] Luther further praised Hus as a martyr unjustly executed in 1415 for proclaiming gospel truths, rejecting the council's authority over divine word and sharing Hus's critique of papal supremacy.[109] This alignment extended to opposition against indulgences and simony, with Hus's sermons decrying clerical abuses prefiguring Luther's 1517 Ninety-Five Theses, though Luther initially sought internal reform while Hussites pursued broader defiance.[110] Doctrinal transmissions included the Hussite advocacy for utraquism—communion under both kinds—which Luther incorporated into Lutheran practice, viewing it as biblically mandated rather than a medieval innovation restricted by the Church.[108] While direct causation remains debated, the emphasis on lay access to Scripture echoed in Hussite promotion of vernacular preaching, paralleling Luther's insistence on sola scriptura without reliance on priestly mediation. John Calvin, though less explicitly referencing Hussites, adopted similar eucharistic reforms favoring both elements, reflecting a shared rejection of withholding the cup from laity as established in early Church practice.[111] The Hussite Wars from 1419 to 1434 empirically demonstrated laity-led resistance could withstand five papal crusades through defensive innovations like chained wagon formations, proving decentralized forces viable against imperial might and bolstering reformers' tactical confidence in defying ecclesiastical authority.[110] Yet, intra-movement schisms—pitting radical Taborites against pragmatic Utraquists—culminated in the Taborites' defeat at the Battle of Lipany in 1434, enabling compromises in the 1436 Compactata of Basel that retained some Catholic elements and diluted radical purity, cautioning against factionalism's erosive effects on reformist unity.[21]Modern Hussite Churches and Scholarship

The Czechoslovak Hussite Church was founded on January 8, 1920, in Prague by reformist clergy who seceded from the Roman Catholic Church amid post-World War I national awakening and demands for liturgical and doctrinal liberalization, including communion in both kinds, vernacular services, and openness to scientific inquiry.[112][113] This denomination, which adopted Jan Hus's name to invoke his critique of ecclesiastical corruption, initially grew to over 100,000 adherents but has since contracted to approximately 30,000 baptized members as of the early 21st century, reflecting broader trends of religious disaffiliation in the Czech Republic.[112] It maintains a progressive stance, permitting female ordination and same-sex blessings, which has drawn accusations of syncretism from more conservative Christian observers who argue it dilutes orthodox doctrine with modern cultural accommodations.[113] The Moravian Church, tracing its origins to the 15th-century Unity of the Brethren—a radical Hussite offshoot founded in 1457—experienced renewal in 1727 under Count Nikolaus von Zinzendorf, leading to a global diaspora with communities in North America, Africa, and beyond, totaling over 1 million members worldwide today.[114] Unlike the localized Czechoslovak Hussite Church, the Moravians emphasize pietistic evangelism and missionary work, sustaining Hussite legacies of communal living and Bible-centered reform outside Czech borders, though their Czech presence remains marginal amid secular pressures.[115] In historiography, 21st-century scholarship has increasingly scrutinized the limits of Hussite radicalism, portraying the movement as driven more by theological disputes over utraquism and anti-clericalism than by proto-modern economic egalitarianism, thereby challenging earlier 20th-century Marxist framings of the Hussite Wars as a class-based uprising against feudal lords.[116] Works such as the 2020 special issue on Hussite Reformation legacies highlight its exclusion from mainstream Protestant narratives due to internal factionalism and eventual compromise with Catholic authorities, rather than revolutionary permanence.[117] Jan Hus himself endures as a Czech national symbol of resistance to foreign domination, commemorated by monuments like the 1915 Prague statue and annual July 6 observances, though this cultural veneration outpaces active religious adherence.[118] Both modern Hussite bodies face empirical decline in the Czech Republic, where surveys indicate fewer than 10% of the population affiliates with any church, attributing this to historical anti-clericalism rooted in Hussitism, communist-era suppression, and pervasive secularism that prioritizes individual autonomy over institutional faith.[119][120] This contrasts with the movement's historical mobilizational power, underscoring how post-1989 liberalization accelerated dechurching without reviving Hussite-inspired communalism.[121]References

- https://en.wikisource.org/wiki/The_Hussite_Wars/Chapter_7