Recent from talks

All channels

Be the first to start a discussion here.

Be the first to start a discussion here.

Be the first to start a discussion here.

Be the first to start a discussion here.

Welcome to the community hub built to collect knowledge and have discussions related to List of geometers.

Nothing was collected or created yet.

List of geometers

View on Wikipediafrom Wikipedia

| Geometry |

|---|

|

| Geometers |

A geometer is a mathematician whose area of study is the historical aspects that define geometry, instead of the analytical geometric studies conducted by geometricians.

Some notable geometers and their main fields of work, chronologically listed, are:

1000 BCE to 1 BCE

[edit]- Baudhayana (fl. c. 800 BC) – Euclidean geometry

- Manava (c. 750 BC–690 BC) – Euclidean geometry

- Thales of Miletus (c. 624 BC – c. 546 BC) – Euclidean geometry

- Pythagoras (c. 570 BC – c. 495 BC) – Euclidean geometry, Pythagorean theorem

- Zeno of Elea (c. 490 BC – c. 430 BC) – Euclidean geometry

- Hippocrates of Chios (born c. 470 – 410 BC) – first systematically organized Stoicheia – Elements (geometry textbook)

- Mozi (c. 468 BC – c. 391 BC)

- Plato (427–347 BC)

- Theaetetus (c. 417 BC – 369 BC)

- Autolycus of Pitane (360–c. 290 BC) – astronomy, spherical geometry

- Euclid (fl. 300 BC) – Elements, Euclidean geometry (sometimes called the "father of geometry")

- Apollonius of Perga (c. 262 BC – c. 190 BC) – Euclidean geometry, conic sections

- Archimedes (c. 287 BC – c. 212 BC) – Euclidean geometry

- Eratosthenes (c. 276 BC – c. 195/194 BC) – Euclidean geometry

- Katyayana (c. 3rd century BC) – Euclidean geometry

1–1300 AD

[edit]- Hero of Alexandria (c. AD 10–70) – Euclidean geometry

- Pappus of Alexandria (c. AD 290–c. 350) – Euclidean geometry, projective geometry

- Hypatia of Alexandria (c. AD 370–c. 415) – Euclidean geometry

- Brahmagupta (597–668) – Euclidean geometry, cyclic quadrilaterals

- Vergilius of Salzburg (c.700–784) – Irish bishop of Aghaboe, Ossory and later Salzburg, Austria; antipodes, and astronomy

- Al-Abbās ibn Said al-Jawharī (c. 800–c. 860)

- Thabit ibn Qurra (826–901) – analytic geometry, non-Euclidean geometry, conic sections

- Abu'l-Wáfa (940–998) – spherical geometry, spherical triangles

- Ibn al-Haytham (965–c. 1040)

- Omar Khayyam (1048–1131) – algebraic geometry, conic sections

- Ibn Maḍāʾ (1116–1196)

1301–1800 AD

[edit] Leonardo da Vinci |

Johannes Kepler |

Girard Desargues |

René Descartes |

Blaise Pascal |

Isaac Newton |

Leonhard Euler |

Carl Gauss |

August Möbius |

Nikolai Lobachevsky |

John Playfair |

Jakob Steiner |

- Piero della Francesca (1415–1492)

- Leonardo da Vinci (1452–1519) – Euclidean geometry

- Jyesthadeva (c. 1500 – c. 1610) – Euclidean geometry, cyclic quadrilaterals

- Marin Getaldić (1568–1626)

- Jacques-François Le Poivre (1652–1710) – projective geometry

- Johannes Kepler (1571–1630) – (used geometric ideas in astronomical work)

- Edmund Gunter (1581–1686)

- Girard Desargues (1591–1661) – projective geometry; Desargues' theorem

- René Descartes (1596–1650) – invented the methodology of analytic geometry, also called Cartesian geometry after him

- Pierre de Fermat (1607–1665) – analytic geometry

- Blaise Pascal (1623–1662) – projective geometry

- Christiaan Huygens (1629–1695) – evolute

- Giordano Vitale (1633–1711)

- Philippe de La Hire (1640–1718) – projective geometry

- Isaac Newton (1642–1727) – 3rd-degree algebraic curve

- Giovanni Ceva (1647–1734) – Euclidean geometry

- Johann Jacob Heber (1666–1727) – surveyor and geometer

- Giovanni Gerolamo Saccheri (1667–1733) – non-Euclidean geometry

- Leonhard Euler (1707–1783)

- Tobias Mayer (1723–1762)

- Johann Heinrich Lambert (1728–1777) – non-Euclidean geometry

- Gaspard Monge (1746–1818) – descriptive geometry

- John Playfair (1748–1819) – Euclidean geometry

- Lazare Nicolas Marguerite Carnot (1753–1823) – projective geometry

- Joseph Diaz Gergonne (1771–1859) – projective geometry; Gergonne point

- Carl Friedrich Gauss (1777–1855) – Theorema Egregium

- Louis Poinsot (1777–1859)

- Siméon Denis Poisson (1781–1840)

- Jean-Victor Poncelet (1788–1867) – projective geometry

- Augustin-Louis Cauchy (1789–1857)

- August Ferdinand Möbius (1790–1868) – Euclidean geometry

- Nikolai Ivanovich Lobachevsky (1792–1856) – hyperbolic geometry, a non-Euclidean geometry

- Michel Chasles (1793–1880) – projective geometry

- Germinal Dandelin (1794–1847) – Dandelin spheres in conic sections

- Jakob Steiner (1796–1863) – champion of synthetic geometry methodology, projective geometry, Euclidean geometry

1801–1900 AD

[edit] Julius Plücker |

Arthur Cayley |

Bernhard Riemann |

Richard Dedekind |

Max Noether |

Felix Klein |

Hermann Minkowski |

Henri Poincaré |

Evgraf Fedorov |

- Karl Wilhelm Feuerbach (1800–1834) – Euclidean geometry

- Julius Plücker (1801–1868)

- János Bolyai (1802–1860) – hyperbolic geometry, a non-Euclidean geometry

- Christian Heinrich von Nagel (1803–1882) – Euclidean geometry

- Johann Benedict Listing (1808–1882) – topology

- Hermann Günther Grassmann (1809–1877) – exterior algebra

- Ludwig Otto Hesse (1811–1874) – algebraic invariants and geometry

- Ludwig Schlafli (1814–1895) – Regular 4-polytope

- Pierre Ossian Bonnet (1819–1892) – differential geometry

- Arthur Cayley (1821–1895)

- Joseph Bertrand (1822–1900)

- Delfino Codazzi (1824–1873) – differential geometry

- Bernhard Riemann (1826–1866) – elliptic geometry (a non-Euclidean geometry) and Riemannian geometry

- Julius Wilhelm Richard Dedekind (1831–1916)

- Ludwig Burmester (1840–1927) – theory of linkages

- Edmund Hess (1843–1903)

- Albert Victor Bäcklund (1845–1922)

- Max Noether (1844–1921) – algebraic geometry

- Henri Brocard (1845–1922) – Brocard points

- William Kingdon Clifford (1845–1879) – geometric algebra

- Pieter Hendrik Schoute (1846–1923)

- Felix Klein (1849–1925)

- Sofia Vasilyevna Kovalevskaya (1850–1891)

- Evgraf Fedorov (1853–1919)

- Henri Poincaré (1854–1912)

- Luigi Bianchi (1856–1928) – differential geometry

- Alicia Boole Stott (1860–1940)

- Hermann Minkowski (1864–1909) – non-Euclidean geometry

- Henry Frederick Baker (1866–1956) – algebraic geometry

- Élie Cartan (1869–1951)

- Dmitri Egorov (1869–1931) – differential geometry

- Veniamin Kagan (1869–1953)

- Raoul Bricard (1870–1944) – descriptive geometry

- Ernst Steinitz (1871–1928) – Steinitz's theorem

- Marcel Grossmann (1878–1936)

- Oswald Veblen (1880–1960) – projective geometry, differential geometry

- Nathan Altshiller Court (1881–1968) – author of College Geometry

- Emmy Noether (1882–1935) – algebraic topology

- Harry Clinton Gossard (1884–1954)

- Arthur Rosenthal (1887–1959)

- Helmut Hasse (1898–1979) – algebraic geometry

1901–present

[edit]H. S. M. Coxeter |

Ernst Witt |

Benoit Mandelbrot |

Branko Grünbaum |

Michael Atiyah |

J. H. Conway |

William Thurston |

Mikhail Gromov |

George W. Hart |

Shing-Tung Yau |

Károly Bezdek |

Grigori Perelman |

Denis Auroux |

- William Vallance Douglas Hodge (1903–1975)

- Patrick du Val (1903–1987)

- Beniamino Segre (1903–1977) – combinatorial geometry

- J. C. P. Miller (1906–1981)

- André Weil (1906–1998) – Algebraic geometry

- H. S. M. Coxeter (1907–2003) – theory of polytopes, non-Euclidean geometry, projective geometry

- J. A. Todd (1908–1994)

- Daniel Pedoe (1910–1998)

- Shiing-Shen Chern (1911–2004) – differential geometry

- Ernst Witt (1911–1991)

- Rafael Artzy (1912–2006)

- Aleksandr Danilovich Aleksandrov (1912–1999)

- László Fejes Tóth (1915–2005)

- Edwin Evariste Moise (1918–1998)

- Aleksei Pogorelov (1919–2002) – differential geometry

- Magnus Wenninger (1919–2017) – polyhedron models

- Jean-Louis Koszul (1921–2018)

- Isaak Yaglom (1921–1988)

- Eugenio Calabi (1923–2023)

- Benoit Mandelbrot (1924–2010) – fractal geometry

- Katsumi Nomizu (1924–2008) – affine differential geometry

- Michael S. Longuet-Higgins (1925–2016)

- John Leech (1926–1992)

- Alexander Grothendieck (1928–2014) – algebraic geometry

- Branko Grünbaum (1929–2018) – discrete geometry

- Michael Atiyah (1929–2019)

- Lev Semenovich Pontryagin (1908–1988)

- Geoffrey Colin Shephard (1927–2016)

- Norman W. Johnson (1930–2017)

- John Milnor (1931–)

- Roger Penrose (1931–)

- Yuri Manin (1937–2023) – algebraic geometry and diophantine geometry

- Vladimir Arnold (1937–2010) – algebraic geometry

- Ernest Vinberg (1937–2020)

- J. H. Conway (1937–2020) – sphere packing, recreational geometry

- Robin Hartshorne (1938–) – geometry, algebraic geometry

- Phillip Griffiths (1938–) – algebraic geometry, differential geometry

- Enrico Bombieri (1940–) – algebraic geometry

- Robert Williams (1942–)

- Peter McMullen (1942–)

- Richard S. Hamilton (1943–2024) – differential geometry, Ricci flow, Poincaré conjecture

- Mikhail Gromov (1943–)

- Rudy Rucker (1946–)

- William Thurston (1946–2012)

- Shing-Tung Yau (1949–)

- Michael Freedman (1951–)

- Egon Schulte (1955–) – polytopes

- George W. Hart (1955–) – sculptor

- Károly Bezdek (1955–) – discrete geometry, sphere packing, Euclidean geometry, non-Euclidean geometry

- Simon Donaldson (1957–)

- Kenji Fukaya (1959–) – symplectic geometry

- Yong-Geun Oh (1961–)

- Toshiyuki Kobayashi (1962–)

- Hiraku Nakajima (1962–) – representation theory and geometry

- Hwang Jun-Muk (1963–) – algebraic geometry, differential geometry

- Grigori Perelman (1966–) – Poincaré conjecture

- Maryam Mirzakhani (1977–2017)

- Denis Auroux (1977–)

Geometers in art

[edit] God as architect of the world, 1220–1230, from Bible moralisée |

Kepler's Platonic solid model of planetary spacing in the Solar System from Mysterium Cosmographicum (1596) |

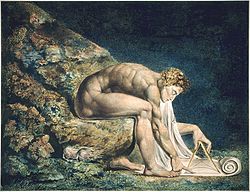

The Ancient of Days, 1794, by William Blake, with the compass as a symbol for divine order |

Newton (1795), by William Blake; here, Newton is depicted critically as a "divine geometer".[2] |

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Bill Casselman. "One of the Oldest Extant Diagrams from Euclid". University of British Columbia. Retrieved 2008-09-26.

- ^ "Newton, object 1 (Butlin 306) "Newton"". William Blake Archive. September 25, 2013.

List of geometers

View on Grokipediafrom Grokipedia

Introduction

Defining Geometers

A geometer is a mathematician specializing in geometry, the branch of mathematics that investigates the properties, measurements, and spatial relations of points, lines, angles, surfaces, solids, and their higher-dimensional counterparts, primarily through deductive reasoning and axiomatic methods.[14] This specialization encompasses diverse approaches, including Euclidean geometry, which relies on flat space and straight lines; non-Euclidean geometries, such as hyperbolic or elliptic systems that challenge parallel postulates; projective geometry, focusing on transformations preserving incidence; and differential geometry, which applies calculus to curved spaces.[14] Unlike broader mathematical pursuits, geometers prioritize rigorous proofs derived from undefined terms and postulates to establish theorems about spatial configurations.[15] The term "geometer" originates from the ancient Greek words geo (earth) and metron (measure), reflecting its roots in practical land measurement and surveying.[16] In ancient Egypt, early practitioners—often called "rope stretchers" or harpedonaptai—used knotted ropes to measure fields after annual Nile floods, developing empirical techniques for areas and volumes that laid foundational geometric knowledge.[17] This practical art evolved through Babylonian and Egyptian influences into the axiomatic framework of Greek mathematics, where figures like Euclid formalized geometry as a deductive science in works such as the Elements, transforming surveyors' tools into abstract theory. By the Hellenistic period, geometers like Apollonius of Perga advanced conic sections, bridging concrete applications with theoretical inquiry. Over centuries, the role expanded to modern abstract theorists exploring multidimensional spaces and topological properties, yet retaining the core emphasis on spatial deduction.[14] While "geometer" and "geometrician" are often synonymous, denoting specialists in geometric study, the former historically emphasizes foundational and theoretical aspects rooted in axiomatic deduction, whereas the latter can extend to applied contexts like computational geometry involving algorithmic implementations for spatial problems.[18] Geometers traditionally distinguish themselves by focusing on pure mathematical structures over numerical computation, prioritizing conceptual proofs over practical software tools.[19] Key prerequisites for geometric study include mastery of axioms—self-evident truths assumed without proof—and postulates, which are specific assumptions about spatial constructions, serving as the bedrock for deductive proofs.[15] These elements enable geometers to build theorems logically, as seen in Euclid's use of five postulates to define Euclidean space, ensuring consistency and universality in spatial reasoning.[14] Without such foundations, geometric inquiry devolves into mere measurement, underscoring the geometer's commitment to logical rigor over empirical observation alone.[20]Historical Context

Geometry originated in ancient civilizations as a practical tool for land measurement and construction. In Mesopotamia around 2000 BCE, Babylonian scribes applied geometric methods to calculate areas and volumes for agriculture and architecture, using clay tablets that recorded problems involving circles, rectangles, and pyramids. Similarly, in ancient Egypt, geometry served surveying needs after Nile floods, with the Rhind Papyrus (c. 1650 BCE) containing problems on computing areas of fields and volumes of granaries, approximating π as 256/81 for circular calculations. These empirical approaches focused on real-world applications rather than abstract proofs.[21][22][23] Around 600 BCE, the Greek axiomatic revolution transformed geometry from empirical practices to a deductive science, emphasizing logical proofs from self-evident axioms. This shift, initiated in Ionia, prioritized rigorous demonstration over measurement, laying the foundation for systematic geometry as seen in foundational texts like Euclid's Elements. During the medieval period (500–1500 CE), geometry was preserved and expanded through translations in the Byzantine and Islamic worlds; scholars in Baghdad's House of Wisdom rendered Greek works, including Euclid's, into Arabic, fostering advancements in spherical geometry and optics while integrating it with astronomy.[23][24][25] The Renaissance (c. 1400–1600 CE) revived geometry in Europe via Latin translations of Arabic texts, intertwining it with art through perspective techniques and with emerging sciences like mechanics. This period marked geometry's broader application in navigation and engineering. In the 19th century, modern diversification emerged with non-Euclidean geometries, challenging Euclid's parallel postulate and revealing multiple consistent spatial frameworks, such as hyperbolic geometry developed independently in the 1820s–1830s. The 20th century introduced computational tools, enabling algorithmic solutions to geometric problems in computer graphics and optimization, transforming the field into a computational discipline.[26][27] In the 21st century, geometry intersects with physics through concepts like Calabi–Yau manifolds in string theory, which model extra dimensions to unify quantum mechanics and gravity. Additionally, AI-driven tools, such as proof assistants, automate theorem verification and discovery in geometric reasoning, accelerating research in complex structures.[28][29][30]Chronological Lists

Ancient Geometers (c. 2000 BCE – 500 CE)

The foundations of deductive geometry were laid in ancient civilizations, particularly in Egypt and Greece, where practical measurements evolved into systematic theorems. Ahmes, an Egyptian scribe active around 1650 BCE, documented early geometric applications in the Rhind Mathematical Papyrus, a key source for understanding ancient Egyptian mathematics that includes problems on calculating areas of circles (approximating π as 256/81) and triangles using practical methods like proportions.[31][32] In Greece, Thales of Miletus (c. 624–546 BCE) pioneered the use of deductive reasoning in geometry, marking a shift from empirical practices to proofs based on axioms. He established theorems such as the intercept theorem, which states that a line parallel to one side of a triangle divides the other two sides proportionally, and properties of circles, including that the angle in a semicircle is a right angle (Thales's theorem).[33][34] Pythagoras (c. 570–495 BCE) and his followers advanced geometric theory through the Pythagorean theorem, which asserts that in a right-angled triangle, the square of the hypotenuse equals the sum of the squares of the other two sides (). Their investigations into geometric constructions also revealed irrational numbers, such as as the hypotenuse of an isosceles right triangle with unit legs, challenging the notion that all lengths could be expressed as rational ratios.[35][36] Hippocrates of Chios (c. 470–410 BCE) contributed to the study of curved figures by achieving the quadrature of lunes—regions bounded by circular arcs—demonstrating that certain lunes have areas equal to rectilinear figures like triangles, using properties of semicircles and Pythagorean theorem applications. His work represented an early systematic approach to squaring the circle, though it ultimately fell short of a general solution.[37] Euclid (c. 300 BCE) synthesized prior knowledge in his monumental Elements, a 13-book treatise covering plane and solid geometry, from basic constructions to advanced topics like circles and polyhedra. Books I–IV focus on plane geometry, including proofs of triangle congruence (side-angle-side, angle-side-angle, and side-side-side criteria) and similarity via parallel lines and proportional segments.[15][38][39] Archimedes (c. 287–212 BCE) developed sophisticated methods for determining areas and volumes, such as the sphere's volume formula and surface area , derived through mechanical balancing and the method of exhaustion—a precursor to integral calculus that approximates curves with inscribed and circumscribed polygons to bound areas precisely. His techniques in works like On the Sphere and Cylinder extended Eudoxus's exhaustion method to irregular figures.[40][41] Apollonius of Perga (c. 240–190 BCE) advanced the theory of conic sections in his eight-book Conics, defining and analyzing ellipses, parabolas, and hyperbolas as plane intersections with cones, including focal properties and equations in terms of diameters and ordinates. He coined the terms "ellipse" (from the deficiency relative to a circle), "parabola" (application), and "hyperbola" (excess), building on earlier work by Menaechmus and Euclid.[42][43] Heron of Alexandria (c. 10–70 CE) provided practical geometric tools in Metrica, including the formula for the area of a triangle with sides , , : where , applicable to any triangle without height measurements. His contributions extended to geometric mechanics, integrating geometry with devices like the aeolipile and catoptrics for reflections in mirrors.[44][45] Ptolemy (c. 100–170 CE) applied geometry to astronomy in the Almagest, developing spherical geometry for celestial mappings, including theorems on great circles and spherical triangles. He compiled chord tables for a circle of radius 60, enabling trigonometric computations equivalent to sine values up to three sexagesimal places, essential for solving spherical problems like eclipse predictions.[46][47] Hypatia of Alexandria (c. 370–415 CE) served as a crucial link in preserving Hellenistic geometry; she edited and commented on Apollonius's Conics, clarifying the properties of conic sections such as ellipses, parabolas, and hyperbolas derived from plane sections of cones, which advanced early algebraic geometry. Her work on Diophantus's Arithmetica further connected arithmetic problems to geometric constructions, ensuring these texts endured through Byzantine and Islamic transmissions.[48][49]Medieval Geometers (500 – 1500 CE)

The medieval period (500–1500 CE) marked a pivotal era in the history of geometry, characterized by the preservation and expansion of ancient Greek knowledge in the Islamic world, where scholars translated, commented upon, and innovated beyond works by Euclid, Apollonius, and Ptolemy. This intellectual activity, centered in institutions like the House of Wisdom in Baghdad, facilitated the integration of geometry with algebra and astronomy, influencing fields from architecture to calendrical science. In Europe, geometry saw a slower revival through Latin translations of Arabic texts, bridging the gap to the Renaissance and laying groundwork for later advancements.[50] In the Islamic Golden Age, Muhammad ibn Musa al-Khwarizmi (c. 780–850 CE) revolutionized geometric problem-solving in his Kitab al-Jabr wa al-Muqabala (The Compendious Book on Calculation by Completion and Balancing), where he provided visual, geometric solutions to quadratic equations, classifying them into six types and demonstrating methods like completing the square through diagrams of squares and rectangles. For instance, to solve , he halved the coefficient of to form a square side of length 5, added its area (25) to balance the equation, and used geometric subtraction to find roots and , emphasizing area manipulations over symbolic algebra.[51][52] Omar Khayyam (1048–1131 CE) extended this synthesis by solving cubic equations geometrically in his Treatise on Demonstration of Problems of Algebra, employing intersections of conic sections to find positive roots; he addressed 14 types of cubics, such as , by constructing a semicircle, a line segment, and a hyperbola whose intersection yielded the solution length. His approach, developed around 1070 in Samarkand, integrated conic properties from Apollonius with algebraic challenges, also informing his geometric approximations for calendar reforms in the Jalali calendar.[53][54] Bhaskara II (1114–1185 CE), an Indian mathematician-astronomer, contributed to plane geometry in his Lilavati (a section of the Siddhanta Shiromani), where he proved variants of the Pythagorean theorem using geometric dissections and similarities, such as arranging triangles to demonstrate without algebraic notation. He also advanced the study of cyclic quadrilaterals, building on Brahmagupta's formula for their area () by providing proofs and applications to mensuration problems, enhancing practical geometry for surveying and architecture.[55][56] Leonardo Fibonacci (c. 1170–1250 CE), an Italian mathematician, bridged Islamic and European geometry in Liber Abaci (1202), introducing Hindu-Arabic numerals to the West and applying them to geometric series and proportions in problems involving areas, volumes, and commercial measurements. His text included geometric constructions for irrational numbers like using circles and lines, and explored series sums geometrically, such as the infinite series for polygonal numbers, fostering arithmetic-geometry links in medieval Europe.[57] Jordanus de Nemore (c. 1220 CE), a European scholar, pioneered arithmetical geometry in mechanics through treatises like De ratione ponderis, where he analyzed levers and statics using proportional reasoning and geometric models of weights on inclined planes, deriving formulas for equilibrium (e.g., ) via virtual displacements and pyramid volumes. His work represented an early fusion of Euclidean geometry with physical applications, influencing later statics.[58] Nasir al-Din al-Tusi (1201–1274 CE), a Persian polymath, advanced spherical geometry in his planetary models at the Maragha Observatory, refining Ptolemy's system with the "Tusi couple"—a geometric device using two circles to produce linear motion from circular ones, eliminating equants for more accurate epicycles. He also applied polyhedral geometry to architectural designs, such as hospital layouts incorporating regular polyhedra for structural symmetry, and commented extensively on Euclid's Elements to preserve and clarify Greek geometric foundations.[50][59]Early Modern Geometers (1501 – 1800 CE)

The Early Modern period marked a renaissance in geometry, blending artistic intuition with rigorous analysis and laying the groundwork for analytic and projective methods that transformed the field. Geometers during this era, spanning the Renaissance to the Enlightenment, integrated algebraic techniques, perspective principles, and mechanical insights, often driven by advancements in art, engineering, and natural philosophy. Key figures advanced coordinate systems, projective theorems, and variational principles, enabling precise descriptions of curves, conics, and polyhedra while bridging geometry with emerging calculus.[60] Leonardo da Vinci (1452–1519) contributed to polyhedral projections and perspective geometry through his illustrations for Luca Pacioli’s Divina proportione (1509), where he depicted complex polyhedra using geometric solids to explore proportional forms in art and engineering.[61] His studies of perspective, influenced by Piero della Francesca’s On Perspective in Painting, applied optical and geometric principles to create realistic spatial representations in works like The Last Supper, merging artistic composition with engineering designs for architecture and military fortifications.[61] Da Vinci also devised mechanical methods for squaring the circle and explored optics geometrically, proposing concave mirrors for magnifying planetary images in the Codex Arundel (c. 1513), which anticipated telescopic applications.[61] Girard Desargues (1591–1661) pioneered projective geometry with theorems emphasizing perspective and conic sections, notably Desargues' theorem, which states that if two triangles are in perspective from a point, the intersections of corresponding sides are collinear.[62] This result, first published in his 1639 pamphlet Brouillon project d'une atteinte aux événements des rencontres d'un cône avec un plan, analyzed the intersections of cones and planes to generate conics, providing a unified framework for ellipses, parabolas, and hyperbolas beyond Euclidean metrics.[62] Desargues' work influenced later projective developments by focusing on invariance under projection, though his ideas were initially overlooked until revived in the 19th century.[62] René Descartes (1596–1650) revolutionized geometry by inventing coordinate geometry in La Géométrie (1637), an appendix to Discours de la méthode, where he introduced the Cartesian plane with perpendicular x and y axes to link algebraic equations directly to geometric figures.[8] This analytic approach allowed solving geometric problems—such as finding tangents to curves—through algebraic manipulation, representing points as ordered pairs and curves as equations like .[8] Descartes' method systematized the classification of curves by degree, enabling the algebraic description of conics and higher-order forms, though he prioritized solvable problems and dismissed more complex ones as "mechanical."[8] Blaise Pascal (1623–1662) advanced projective geometry with Pascal's theorem, which asserts that for a hexagon inscribed in a conic section, the intersections of opposite sides are collinear, as detailed in his 1639 essay Essai pour les coniques.[63] Presented at age 16 to Marin Mersenne's circle, this "mystic hexagon" theorem generalized properties of conics under projection, building on Desargues' ideas and applying them to circles and ellipses.[63] Pascal's unfinished treatise Génération des coniques (c. 1648, reconstructed from notes by Leibniz) explored conic generation via rotating lines and central projections, emphasizing invariance in projective transformations.[63] Isaac Newton (1643–1727) employed geometric fluxions—an early form of calculus—to analyze curves and conic sections, as outlined in De Methodis Serierum et Fluxionum (written 1671, published 1736), where fluxions represented instantaneous rates of change for finding tangents and areas under curves.[64] In Philosophiæ Naturalis Principia Mathematica (1687), Newton geometrically proved that inverse-square forces produce conic orbits, such as ellipses for planetary motion, linking Kepler's laws to gravitational geometry in Book 1, Lemma 21–22.[64] His synthetic geometric style in the Principia favored diagrams over algebra, using fluxions to classify cubic curves in Enumeratio Linearum Tertii Ordinis (1704).[64] Leonhard Euler (1707–1783) formulated Euler's polyhedron formula, , relating vertices (), edges (), and faces () for convex polyhedra, introduced in a 1752 letter to Christian Goldbach and published in Elementa doctrinae solidorum (1758).[9] This topological invariant bridged polyhedral geometry to graph theory, as seen in his 1736 solution to the Seven Bridges of Königsberg problem, which required even-degree vertices for Eulerian paths in geometric networks.[9] Euler's geometric works, including Introductio in analysin infinitorum (1748), also advanced analytic geometry by classifying curves and surfaces, with applications to mechanics in Mechanica (1736–1737).[9] Johann Heinrich Lambert (1728–1777) introduced hyperbolic functions (sinh, cosh, tanh) independently in 1761 for geometric calculations involving non-Euclidean surfaces, as part of his trigonometric studies in Theorie der Parallellinien (1766).[65] He provided the first rigorous proof of π's irrationality in a 1761 memoir to the Berlin Academy (published 1768), using continued fractions and geometric properties of tangents, showing that tan(π/4) = 1 implies π/4 is irrational since rational angles yield algebraic tangents.[65] Lambert's geometric approach extended to hyperbolic geometry, exploring parallel lines on curved surfaces and anticipating non-Euclidean metrics.[65] Joseph-Louis Lagrange (1736–1813) developed variational geometry in mechanics through the calculus of variations, solving the tautochrone problem in 1754 and generalizing Euler's methods in 1756 papers for the Turin Academy.[66] In Mécanique Analytique (1788), he reformulated Newtonian mechanics analytically, using variational principles like least action to derive equations of motion for geometric paths in configuration space, minimizing functionals such as .[66] Lagrange's approach eliminated geometric diagrams in favor of algebraic coordinates, emphasizing generalized coordinates for rigid body motions and celestial orbits.[66]19th Century Geometers (1801 – 1900 CE)

The 19th century marked a revolutionary period in geometry, shifting from Euclidean foundations to non-Euclidean and algebraic frameworks that challenged absolute space and introduced curved manifolds. Geometers during this era developed tools to describe hyperbolic and elliptic geometries, laying groundwork for modern differential geometry and topology. Key figures explored alternatives to Euclid's parallel postulate, quantified curvature intrinsically, and classified geometries via group actions, influencing physics and pure mathematics profoundly. Carl Friedrich Gauss (1777–1855) pioneered intrinsic geometry with his concept of Gaussian curvature, introduced in the 1827 paper "Disquisitiones generales circa superficies curvas," where he proved the Theorema egregium: the Gaussian curvature at a point on a surface is an intrinsic property, invariant under isometries and determinable solely from distance measurements within the surface. This theorem decoupled curvature from extrinsic embedding in Euclidean space, hinting at non-Euclidean possibilities without explicitly publishing them due to caution. Gauss's work on the arithmetic-geometric mean also connected elliptic integrals to geometric forms, advancing conformal mappings. Nikolai Lobachevsky (1792–1856) independently developed hyperbolic geometry, publishing "On the Principles of Geometry" in 1829, where he replaced Euclid's parallel postulate with the axiom that through a point not on a line, multiple parallels can be drawn. This led to a consistent geometry with negative curvature, where the sum of angles in a triangle is less than 180 degrees, verified through trigonometric relations like cosh(c) = (cosh(a)cosh(b) - cos(γ))/sinh(a)sinh(b) for sides a, b, c and angle γ. His Kazan University lectures and 1835–1838 papers in German further disseminated these ideas, establishing hyperbolic trigonometry as a viable alternative to Euclidean norms. János Bolyai (1802–1860), working independently, formulated a non-Euclidean geometry in his 1832 "Appendix" to his father Farkas's Tentamen, asserting an absolute geometry where the parallel postulate is unnecessary and introducing hyperbolic metrics with infinitely many parallels. Bolyai's system equated Euclidean geometry to a special case of his broader framework, using axioms to derive properties like the area of a circle being proportional to its squared radius times a constant greater than π. His unpublished letters to Gauss in 1823 reveal early insights, though the Appendix remained underappreciated until republished in the 1890s. August Möbius (1790–1868) contributed to projective and topological geometry through Möbius transformations, detailed in his 1827 "Der barycentrische Calcül," which describe conformal mappings of the plane to itself via fractional linear transformations az + b / cz + d, preserving angles and circular arcs. He also introduced the Möbius strip in 1858, a one-sided surface formed by twisting and joining a rectangle's ends, demonstrating non-orientable topology in three dimensions and influencing knot theory. Möbius's barycentric coordinates unified point, line, and plane representations in projective space. Arthur Cayley (1821–1895) advanced algebraic geometry with Cayley-Klein metrics, outlined in his 1878 "A Memoir on the Theory of the Metrical Geometry of the Euclidean and Non-Euclidean," which embed non-Euclidean spaces into projective frameworks using quadratic forms to define distances. These metrics generalized Euclidean, hyperbolic, and elliptic geometries via polarity and absolute conics, enabling unified treatments. Cayley's 1858 work on matrices applied them to linear transformations in geometry, such as rotations and similarities. Bernhard Riemann (1826–1866) revolutionized differential geometry in his 1854 habilitation lecture "Über die Hypothesen, welche der Geometrie zu Grunde liegen," defining the Riemannian metric ds² = g_{ij} dx^i dx^j, where g_{ij} is a positive-definite metric tensor varying smoothly on a manifold, allowing intrinsic measurement of lengths, angles, and curvatures on abstract spaces. This framework encompassed Euclidean geometry as a flat case and enabled elliptic geometries with positive curvature, generalizing surfaces to higher dimensions. Riemann's ideas on complex manifolds also bridged geometry and analysis. James Joseph Sylvester (1814–1897) integrated matrix theory into geometry through his 1850 paper "Addition to the Fourth and Seventh Books of Euclid," applying matrices to represent conic sections and quadratic forms, facilitating transformations in projective geometry. His development of the discriminant for binary forms in 1851 classified singular curves geometrically, and with Cayley, he co-founded invariant theory, quantifying symmetries in algebraic varieties. Sylvester's graph theory precursors modeled geometric configurations like linkages. Felix Klein (1849–1925) proposed the Erlangen program in his 1872 inaugural address "Vergleichende Betrachtungen über neuere geometrische Forschungen," classifying geometries by their underlying symmetry groups: Euclidean by similarities, projective by collineations, and affine by affinities, with non-Euclidean variants via appropriate subgroups. This group-theoretic unification highlighted transformations preserving incidence or metrics, influencing modern geometry. Klein's 1884 "Lectures on the Ikosahedron" applied it to regular polyhedra. Henri Poincaré (1854–1912) advanced non-Euclidean geometry with Fuchsian groups, introduced in his 1882 papers "Sur les fonctions fuchsiennes," which are discrete subgroups of PSL(2,ℝ) acting on the hyperbolic plane, generating automorphic functions invariant under tessellations. These groups tiled the Poincaré disk model, providing uniformization for Riemann surfaces and insights into modular forms. His 1883 "Mémoire sur les courbes planes ce qu'on s'appelle groupement par feuilletage" explored topological implications, foreshadowing qualitative dynamics.20th Century Geometers (1901 – 2000 CE)

The 20th century marked a transformative era in geometry, where mathematicians integrated classical geometric principles with emerging fields such as topology, abstract algebra, and theoretical physics, fostering interdisciplinary advancements that reshaped the foundations of mathematics and its applications. Geometers of this period developed axiomatic systems, symmetry theories, and classifications that not only resolved longstanding problems but also influenced quantum mechanics, relativity, and computational modeling. Key figures advanced non-Euclidean and higher-dimensional structures, emphasizing rigorous proofs and novel invariants to explore the intrinsic properties of spaces.- David Hilbert (1862–1943): Hilbert formalized the foundations of geometry through a set of 21 axioms that provided a complete and consistent basis for Euclidean geometry, addressing gaps in Euclid's original postulates by incorporating incidence, order, congruence, parallelism, and continuity.[67] These axioms enabled the rigorous analysis of geometric constructions and influenced the development of modern axiomatic mathematics. In 1900, Hilbert presented 23 unsolved problems at the International Congress of Mathematicians, several of which—such as the foundations of geometry—spurred advancements in algebraic geometry and topology by challenging mathematicians to unify disparate geometric traditions.[68]

- Hermann Weyl (1885–1955): Weyl pioneered gauge theory in 1918 as an extension of general relativity, introducing local symmetries in spacetime that unified gravity and electromagnetism through infinitesimal scale transformations, laying the groundwork for modern particle physics.[69] His work on symmetric geometries, including the classification of compact Lie groups and their representations, bridged differential geometry with group theory, providing tools for analyzing symmetric spaces in both pure mathematics and quantum field theory.[70]

- H.S.M. Coxeter (1907–2003): Coxeter systematized the study of regular polytopes in higher dimensions through his 1948 book Regular Polytopes, classifying all finite regular polytopes in Euclidean spaces up to dimension four and extending Schläfli's work to non-Euclidean geometries.[71] He introduced Coxeter groups as reflection groups generated by mirrors, which describe the symmetry groups of these polytopes and tessellations, integrating combinatorial algebra with geometric visualization and influencing crystallography and computer graphics.[72]

- Emmy Noether (1882–1935): Noether's 1918 theorem established a profound link between continuous symmetries of geometric systems—such as invariances under translations, rotations, or scaling in Lagrangian mechanics—and corresponding conservation laws, like momentum, angular momentum, and energy, providing a geometric foundation for classical and relativistic physics.[73] In geometric contexts, the theorem applies to variational problems on manifolds, where symmetries of the action integral yield conserved quantities that underpin the structure of differential equations in curved spaces, influencing fields from general relativity to algebraic topology.[74] Her work emphasized the role of invariance groups in unifying geometric and physical laws, with applications to Noether currents that quantify charge conservation in gauge theories.

- Benoit Mandelbrot (1924–2010): Mandelbrot introduced the Mandelbrot set in 1980 as the iconic boundary of the Julia set for the quadratic map in the complex plane, revealing intricate self-similar structures that challenged traditional notions of dimension and smoothness in geometry.[75] He defined fractal dimension as , where is the number of self-similar copies at scale factor , quantifying the roughness of irregular shapes like coastlines or natural forms and integrating geometric measure theory with chaos and dynamical systems.[76]

- John von Neumann (1903–1957): Von Neumann developed geometric operator theory in the 1930s through his work on rings of operators in Hilbert space, introducing von Neumann algebras as self-adjoint operator algebras that capture the spectral properties of quantum observables in infinite-dimensional geometric settings.[77] His spectral theorem for normal operators extended geometric intuitions from finite matrices to unbounded spaces, providing a framework for measuring geometric invariants like distances and angles in abstract Hilbert geometries, with profound impacts on functional analysis and quantum mechanics.[78]

- Shiing-Shen Chern (1911–2004): Chern defined Chern classes in 1940s as topological invariants in the cohomology ring of complex manifolds, constructed via the curvature form of connections on vector bundles, which measure obstructions to flatness in differential geometry.[79] These classes unified de Rham cohomology with characteristic classes, enabling the computation of Euler characteristics and signatures for manifolds, and became essential in algebraic geometry for studying bundles over projective spaces.[80]

- William Thurston (1946–2012): Thurston formulated the geometrization conjecture in the 1970s, positing that every compact 3-manifold decomposes uniquely into pieces admitting one of eight geometric structures—such as Euclidean, hyperbolic, or spherical—via a canonical hierarchy of tori and spheres, integrating low-dimensional topology with Riemannian geometry.[81] This conjecture classifies 3-manifolds by their geometric invariants, resolving the Poincaré conjecture as a special case and providing a blueprint for understanding the topology of 3-dimensional spaces through uniformization and orbifold theorems.[82]