Recent from talks

Contribute something

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Anti-Japanese sentiment

View on WikipediaThis article has multiple issues. Please help improve it or discuss these issues on the talk page. (Learn how and when to remove these messages)

|

| Country polled | Positive | Negative | Neutral | Pos − neg |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3 | -53 | |||

| 25 | 3 | |||

| 5 | 47 | |||

| 42 | 18 | |||

| 38 | 28 | |||

| 39 | 29 | |||

| 19 | 31 | |||

| 19 | 33 | |||

| 5 | 35 | |||

| 18 | 36 | |||

| 20 | 36 | |||

| 37 | 37 | |||

| 26 | 40 | |||

| 12 | 42 | |||

| 5 | 53 | |||

| 15 | 55 | |||

| 5 | 61 | |||

| 11 | 65 |

| Country polled | Favorable | Unfavorable | Neutral | Fav − Unfav |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 6 | -86 | |||

| 1 | -55 | |||

| 42 | 44 | |||

| 4 | 60 | |||

| 6 | 62 | |||

| 9 | 67 | |||

| 14 | 74 |

| Country polled | Positive | Negative | Neutral | Pos − Neg |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 11 | -53 | |||

| 42 | -10 | |||

| 51 | 19 | |||

| 42 | 24 | |||

| 48 | 26 | |||

| 16 | 26 | |||

| 44 | 30 | |||

| 16 | 32 | |||

| 17 | 33 | |||

| 34 | 34 | |||

| 14 | 34 | |||

| 24 | 38 | |||

| 34 | 38 | |||

| 19 | 41 | |||

| 8 | 43 | |||

| 12 | 48 | |||

| 16 | 48 | |||

| 18 | 50 | |||

| 21 | 51 | |||

| 17 | 51 | |||

| 13 | 51 | |||

| 20 | 52 | |||

| 26 | 54 | |||

| 28 | 58 | |||

| 4 | 72 | |||

| 8 | 78 |

Anti-Japanese sentiment (also called Japanophobia, Nipponophobia[4] and anti-Japanism) is the fear or dislike of Japan or Japanese culture. Anti-Japanese sentiment can take many forms, from antipathy toward Japan as a country to racist hatred of Japanese people.

Overview

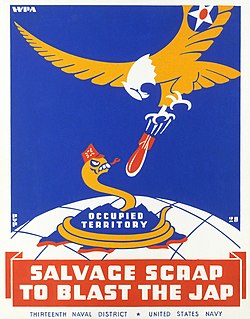

[edit]Anti-Japanese sentiments range from animosity towards the Japanese government's actions during the Second Sino-Japanese War and World War II, to disdain for Japanese culture, or to racism against the Japanese people. Sentiments of dehumanization have been fueled by the anti-Japanese propaganda of the Allied governments in World War II; this propaganda was often of a racially disparaging character. Anti-Japanese sentiment may be strongest in Korea and China,[5][6][7][8] due to atrocities committed by the Imperial Japanese military.[9]

In the past, anti-Japanese sentiment contained innuendos of Japanese people as barbaric. Following the Meiji Restoration of 1868, Japan was intent to adopt Western ways in an attempt to join the West as an industrialized imperial power, but a lack of acceptance of the Japanese in the West complicated integration and assimilation. Japanese culture was viewed with suspicion and even disdain.[citation needed]

While passions have settled somewhat since Imperial Japan's surrender in the Pacific War theater of World War II, tempers continue to flare on occasion over the widespread perception that the Japanese government has made insufficient penance for their past atrocities, or has sought to whitewash the history of these events.[10] Today, though the Japanese government has effected some compensatory measures, anti-Japanese sentiment continues based on historical and nationalist animosities linked to Imperial Japanese military aggression and atrocities. Japan's delay in clearing more than 700,000 (according to the Japanese Government[11]) pieces of life-threatening and environment contaminating chemical weapons buried in China at the end of World War II is another cause of anti-Japanese sentiment. [citation needed]

Periodically, individuals within Japan spur external criticism. Former Prime Minister Junichiro Koizumi was heavily criticized by South Korea and China for annually paying his respects to the war dead at Yasukuni Shrine, which enshrines all those who fought and died for Imperial Japan as part of the Axis Powers during World War II, including 1,068 convicted war criminals. Right-wing nationalist groups have produced history textbooks whitewashing Japanese atrocities,[12] and the recurring controversies over these books occasionally attract hostile foreign attention.[citation needed]

Some anti-Japanese sentiment originates from business practices used by some Japanese companies, such as dumping.[citation needed]

By region

[edit]Brazil

[edit]Like the elites in Argentina and Uruguay, the Brazilian elite wanted to racially whiten the country's population during the 19th and 20th centuries. The country's governments always encouraged European immigration, but non-white immigration was always greeted with considerable opposition. The communities of Japanese immigrants were seen as an obstacle to the whitening of Brazil and they were also seen, among other concerns, as being particularly tendentious because they formed ghettos and they also practiced endogamy at a high rate. Oliveira Viana, a Brazilian jurist, historian, and sociologist, described the Japanese immigrants as follows: "They (Japanese) are like sulfur: insoluble." The Brazilian magazine O Malho in its edition of 5 December 1908, issued a charge of Japanese immigrants with the following legend: "The government of São Paulo is stubborn. After the failure of the first Japanese immigration, it contracted 3,000 yellow people. It insists on giving Brazil a race diametrically opposite to ours."[13] On 22 October 1923, Representative Fidélis Reis produced a bill on the entry of immigrants, whose fifth article was as follows: "The entry of settlers from the black race into Brazil is prohibited. For Asian [immigrants] there will be allowed each year a number equal to 5% of those residing in the country...."[14]

Years before World War II, the government of President Getúlio Vargas initiated a process of forced assimilation of people of immigrant origin in Brazil. In 1933, a constitutional amendment was approved by a large majority and established immigration quotas without mentioning race or nationality and prohibited the population concentration of immigrants. According to the text, Brazil could not receive more than 2% of the total number of entrants of each nationality that had been received in the last 50 years. Only the Portuguese were excluded. The measures did not affect the immigration of Europeans such as Italians and Spaniards, who had already entered in large numbers and whose migratory flow was downward. However, immigration quotas, which remained in force until the 1980s, restricted Japanese immigration, as well as Korean and Chinese immigration.[15][13][16]

When Brazil sided with the Allies and declared war on Japan in 1942, all communication with Japan was cut off, the entry of new Japanese immigrants was forbidden, and many restrictions affected the Japanese Brazilians. Japanese newspapers and teaching the Japanese language in schools were banned, which left Portuguese as the only option for Japanese descendants. As many Japanese immigrants could not understand Portuguese, it became exceedingly difficult for them to obtain any extra-communal information.[17] In 1939, research of Estrada de Ferro Noroeste do Brasil in São Paulo showed that 87.7% of Japanese Brazilians read newspapers in the Japanese language, a much higher literacy rate than the general populace at the time.[13] Japanese Brazilians could not travel without safe conduct issued by the police, Japanese schools were closed, and radio receivers were confiscated to prevent transmissions on shortwave from Japan. The goods of Japanese companies were confiscated and several companies of Japanese origin had interventions by the government. Japanese Brazilians were prohibited from driving motor vehicles, and the drivers employed by the Japanese had to have permission from the police. Thousands of Japanese immigrants were arrested or deported from Brazil on suspicion of espionage.[13] On 10 July 1943, approximately 10,000 Japanese and German and Italian immigrants who lived in Santos had 24 hours to move away from the Brazilian coast. The police acted without any notice. About 90% of the people displaced were Japanese. To reside in coastal areas, the Japanese had to have a safe conduct.[13] In 1942, the Japanese community that introduced the cultivation of pepper in Tomé-Açu, in Pará, was virtually turned into a "concentration camp". This time, the Brazilian ambassador in Washington, DC, Carlos Martins Pereira e Sousa, encouraged the government of Brazil to transfer all Japanese Brazilians to "internment camps" without the need for legal support, just as was done with the Japanese residents in the United States. However, no suspicion of activities of the Japanese against "national security" was ever confirmed.[13]

Even after the war ended, anti-Japanese sentiment persisted in Brazil. After the war, Shindo Renmei, a terrorist organization formed by Japanese immigrants that murdered Japanese-Brazilians who believed in Japanese surrender, was founded. The violent acts committed by this organization increased anti-Japanese sentiment in Brazil and caused several violent conflicts between Brazilians and Japanese-Brazilians.[13] During the National Constituent Assembly of 1946, the representative of Rio de Janeiro Miguel Couto Filho proposed an amendment to the Constitution saying "It is prohibited the entry of Japanese immigrants of any age and any origin in the country." In the final vote, a tie with 99 votes in favour and 99 against. Senator Fernando de Melo Viana, who chaired the session of the Constituent Assembly, had the casting vote and rejected the constitutional amendment. By only one vote, the immigration of Japanese people to Brazil was not prohibited by the Brazilian Constitution of 1946.[13]

In the second half of the 2010s, a certain anti-Japanese feeling has grown in Brazil. The former Brazilian president, Jair Bolsonaro, was accused of making statements considered discriminatory against Japanese people, which generated repercussions in the press and in the Japanese-Brazilian community,[18][19] which is considered the largest in the world outside of Japan.[20] In addition, in 2020, possibly as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic, some incidents of xenophobia and abuse were reported to Japanese-Brazilians in cities such as São Paulo and Rio de Janeiro.[21][22][23][24]

According to a 2017 BBC World Service survey, 70% of Brazilians view Japan's influence positively, with 15% expressing a negative view, making Brazil one of the most pro-Japanese countries in South America.[1]

Canada

[edit]Like other countries to which the Japanese immigrated in significant numbers, anti-Japanese sentiment in Canada was strongest during the 20th century, with the formation of anti-immigration organizations such as the Asiatic Exclusion League in response to Japanese and other Asian immigration. Anti-Japanese and anti-Chinese riots also frequently broke out such one in early 1900s Vancouver. During World War II, Japanese Canadians were interned like their American counterparts. Financial compensation for surviving internees was finally paid in 1988 by the Brian Mulroney government.[25]

China

[edit]

Anti-Japanese sentiment is felt very strongly in China, and distrust, hostility and negative feelings towards Japan and the Japanese people and culture is widespread in China. Anti-Japanese sentiment is a phenomenon that mostly dates back to modern times (since 1868). Like many Western powers during the era of imperialism, Imperial Japan negotiated treaties that often resulted in the annexation of land from China towards the end of the Qing dynasty. Dissatisfaction with Japanese settlements and the Twenty-One Demands by the Japanese government led to a serious boycott of Japanese products in China.

Today, bitterness persists in China[26] over the atrocities of the Second Sino-Japanese War and Japan's postwar actions, particularly the perceived lack of a straightforward acknowledgment of such atrocities, the Japanese government's employment of known war criminals, and Japanese historic revisionism in textbooks. In elementary school, children are taught about Japanese war crimes in detail. For example, thousands of children are brought to the Museum of the War of Chinese People's Resistance Against Japanese Aggression in Beijing by their elementary schools and required to view photos of war atrocities, such as exhibits of records of the Japanese military forcing Chinese workers into wartime labor,[27] the Nanjing Massacre,[28] and the issues of comfort women.[29] After viewing the museum, the children's hatred of the Japanese people was reported to significantly increase. Despite the time that has passed since the end of the war, discussions about Japanese conduct during it can still evoke powerful emotions today, partly because most Japanese are aware of what happened during it although their society has never engaged in the type of introspection which has been common in Germany after the Holocaust.[30] Hence, the usage of Japanese military symbols is still controversial in China, such as the incident in which the Chinese pop singer Zhao Wei was seen wearing a Rising Sun Flag while she was dressed for a fashion magazine photo shoot in 2001.[31] Huge responses were seen on the Internet, a public letter demanding a public apology was also circulated by a Nanjing Massacre survivor, and the singer was even attacked.[32] According to a 2017 BBC World Service Poll, only 22% of Chinese people view Japan's influence positively, and 75% express a negative view, making China the most anti-Japanese nation in the world.[1] Online hate speech against the Japanese is common on Chinese social media.[33]

Anti-Japanese sentiment can also be seen in war films and anime that are currently being produced and broadcast in Mainland China. More than 200 anti-Japanese films were produced in China in 2012 alone.[34] In one particular situation involving a more moderate anti-Japanese war film, the government of China banned the 2000 fictional film, Devils on the Doorstep because it depicted a Japanese soldier being friendly with Chinese villagers. While Lycoris Recoil considered too violent in Southeast Asia since the assassination of Shinzo Abe.[35]

France

[edit]Japan's public service broadcaster, NHK, provides a list of overseas safety risks for traveling, and in early 2020, it listed anti-Japanese discrimination as a safety risk on travel to France and some other European countries, possibly because of fears over the COVID-19 pandemic and other factors.[36] Signs of rising anti-Japanese sentiment in France include an increase in anti-Japanese incidents reported by Japanese nationals, such as being mocked on the street and refused taxi service, and least one Japanese restaurant has been vandalized.[37][38][39] A group of Japanese students on a study tour in Paris received abuse by locals.[40] Another group of Japanese citizens was targeted by acid attacks, which prompted the Japanese embassy as well as the foreign ministry to issue a warning to Japanese nationals in France, urging caution.[41][42] Due to rising discrimination, a Japanese TV announcer in Paris said it's best not to speak Japanese in public or wear a Japanese costume like a kimono.[43]

Germany

[edit]According to the Japanese foreign ministry, anti-Japanese sentiment and discrimination has been rising in Germany, especially recently when the COVID-19 pandemic began affecting the country.[44]

Media sources have reported a rise in anti-Japanese sentiment in Germany, with some Japanese residents saying suspicion and contempt towards them have increased noticeably.[45] In line with those sentiments, there have been a rising number of anti-Japanese incidents such as at least one major football club kicking out all Japanese fans from their stadium over fears of the coronavirus, locals throwing raw eggs at Japanese people's homes and a general increase in the level of harassment toward Japanese residents.[46][47][48]

Indonesia

[edit]In a press release, the embassy of Japan in Indonesia stated that incidents of discrimination and harassment of Japanese people had increased, and they were possibly partly related to the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020, and it also announced that it had set up a help center in order to assist Japanese residents in dealing with those incidents.[49] In general, there have been reports of widespread anti-Japanese discrimination and harassment in the country, with hotels, stores, restaurants, taxi services and more refusing Japanese customers and many Japanese people were no longer allowed in meetings and conferences. The embassy of Japan has also received at least a dozen reports of harassment toward Japanese people in just a few days.[50][51] According to the Ministry of Foreign Affairs (Japan), anti-Japanese sentiment and discrimination has been rising in Indonesia.[44]

Japan

[edit]Korea

[edit]

The issue of anti-Japanese sentiment in Korea is complex and multifaceted. Anti-Japanese attitudes in the Korean Peninsula can be traced as far back as the Japanese pirate raids and the Japanese invasions of Korea (1592–1598), but they are largely a product of the Japanese occupation of Korea which lasted from 1910 to 1945 and the subsequent revisionism of history textbooks which have been used by Japan's educational system since World War II.

Today, issues of Japanese history textbook controversies, Japanese policy regarding the war, and geographic disputes between the two countries perpetuate that sentiment, and the issues often incur huge disputes between Japanese and South Korean Internet users.[52] South Korea, together with Mainland China, may be considered as among the most intensely anti-Japanese societies in the world.[53] Among all the countries that participated in BBC World Service Poll in 2007 and 2009, South Korea and the People's Republic of China were the only ones whose majorities rated Japan negatively.[54][55]

Peru

[edit]Anti-Japanese sentiment in Peru started during 20th century as part of a general anti-Asiatic sentiment after Chinese immigration in Perú, because Japanese and Chinese people were catalogued as a "yellow menace" that deteriorate the race and invaded Peruvian territory. Politicians and intellectuals tried to generate repudiation against Asians through publications such as bulletins and articles in newspapers and pamphlets that ridiculed them, even inciting the Peruvian people to attack Peruvian-Japanese citizens and their businesses.[56] Peruvian worker protests led to the creation of an Anti-Asian Association in 1917 and the abolition of contract migration in 1923.[57]

Then, the pre-war times were especially difficult for Japanese immigrants, coming to influence the Peruvian government itself (with the deportations of Japanese to concentration camps in the United States during World War II, specially to the country's only family internment camp in Crystal City, Texas). Although there had been ongoing tensions between non-Japanese and Japanese Peruvians, the situation was drastically exacerbated by the war.[58] The economic success of Japanese farmers and businessmen in niche but visible sectors, the significant amount of remittances sent back to Japan, the fear that Japanese were taking jobs from the locals and a growing trade imbalance between Japan and Peru were motives to implement legislation in order to curb Japanese immigration into its borders.[57] Like In 1937, in which Peruvian government passed a decree revoking citizenship rights of Peruvians who had Japanese ancestry, followed by a second decree making it even more difficult to maintain citizenship, the results of which included stigmatization of Japanese immigrants as "bestial", "untrustworthy", "militaristic,". and "unfairly" competing with Peruvians for wages.[58] These contributed to increasing nationalism and anti-Japanese sentiment which worsened alongside the depressed and unstable Peruvian economy.[57]

Fueled by legislative discrimination and media campaigns, a massive race riot (referred to as the "Saqueo") began on May 13, 1940, and lasted for three days. During the riots Japanese Peruvians were attacked and their homes and businesses destroyed.[59] There were damaged over 600 Japanese residences and businesses in Lima, resulting in dozens of injuries and one Japanese death. Not only was it the “worst rioting in Peruvian history,” but it was also the first to target a racial group (because Peruvians mostly discriminate by social class, but doesn't had a tradition of discrimination by race).[57] Despite its massive scale, the saqueo was underreported, a reflection of public sentiment towards the Japanese population at the time.[59]

The deportees were viewed as a threat to both Peru and the United States before and after the bombing of Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941, being registered pressure from the United States, which was an influence for Peruvians’ “anti-Japanese attitude” against their own citizens.[60] The deportation of Japanese Peruvians to the United States also involved expropriation without compensation of their property and other assets in Peru.[61] As noted in a 1943 memorandum, Raymond Ickes of the Central and South American division of the Alien Enemy Control Unit had observed that many ethnic Japanese had been sent to the United States "... merely because the Peruvians wanted their businesses and not because there was any adverse evidence against them."[62]

During post-war, decreased anti-Japanese sentiment on Peruvian society, specially after 1960 (when Japan started to develop closer relations with Peru and their Nikkei community). However, there was a light revival of those sentiments after the government of Alberto Fujimori, a Peruvian-Japanese who was involved in Corruption in Peru, which generated antipathy against Japan in Peruvian circles.[63] This revival of the sentiment was so intense that were concerned by the Japan government, after Alberto Fujimori's arrest and trial, the Japanese embassy in Peru and the local media have received frequent telephone calls threatening to harm Japanese-Peruvians, Japanese businesses in Peru, the installations of the embassy and its staff.[64]

Philippines

[edit]

Anti-Japanese sentiment in the Philippines can be traced back to the Japanese occupation of the country during World War II and its aftermath. An estimated 1 million Filipinos out of a wartime population of 17 million were killed during the war, and many more Filipinos were injured. Nearly every Filipino family was affected by the war on some level. Most notably, in the city of Mapanique, survivors have recounted the Japanese occupation during which Filipino men were massacred and dozens of women were herded in order to be used as comfort women. Today, the Philippines has peaceful relations with Japan. In addition, Filipinos are generally not as offended as Chinese or Koreans are by the claim from some quarters that the atrocities are given little, if any, attention in Japanese classrooms. This feeling exists as a result of the huge amount of Japanese aid which was sent to the country during the 1960s and 1970s.[65]

The Davao Region, in Mindanao, had a large community of Japanese immigrants which acted as a fifth column by welcoming the Japanese invaders during the war. The Japanese were hated by the Moro Muslims and the Chinese.[66] The Moro juramentadoss performed suicide attacks against the Japanese, and no Moro juramentado ever attacked the Chinese, who were not considered enemies of the Moro, unlike the Japanese.[67][68][69][70]

According to a 2011 BBC World Service Poll, 84% of Filipinos view Japan's influence positively, with 12% expressing a negative view, making Philippines one of the most pro-Japanese countries in the world.[3]

Singapore

[edit]The older generation of Singaporeans have some resentment towards Japan due to their experiences in World War II when Singapore was under Japanese Occupation but because of developing good economical ties with them, Singapore is currently having a positive relationship with Japan.[71]

Taiwan

[edit]Due to Japan's various oppression and enslavement of Taiwan during World War II and the dispute over the Senkaku Islands, anti-Japanese sentiment in Taiwan is very common, and most Taiwanese people have a negative impression of Japan.[72] However, according to other surveys, Taiwan's anti-Japanese sentiment is seen as much weaker or relatively favorable compared to South Korea, which was affected by the same Japanese colonialism.[73][74] Anti-Japanese sentiment appears weaker in Taiwan than anti-Chinese (especially anti-PRC) sentiment.[75]

The Kuomintang (KMT) victory in 2008 was followed by a boating accident resulting in Taiwanese deaths, which caused recent tensions. Taiwanese officials began speaking out on the historical territory disputes regarding the Diaoyutai/Senkaku Islands, which resulted in an increase in at least perceived anti-Japanese sentiment.[76]

Thailand

[edit]Anti-Japanese sentiment was widespread among Thai pro-democracy student protesters in the 1970s. Demonstrators viewed the entry of Japanese companies into the country, invited by the Thai military, as an economic invasion.[77]

Russian Empire and Soviet Union

[edit]In the Russian Empire, the Imperial Japanese victory during the Russo-Japanese War in 1905 halted Russia's ambitions in the East and led to a loss of prestige. During the later Russian Civil War, Japan was part of the Allied interventionist forces that helped to occupy Vladivostok until October 1922 with a puppet government under Grigorii Semenov. At the end of World War II during the Soviet-Japanese War in August 1945, the Red Army accepted the surrender of nearly 600,000 Japanese POWs after Emperor Hirohito announced the Japanese surrender on 15 August; 473,000 of them were repatriated, 55,000 of them had died in Soviet captivity, and the fate of the others is unknown. Presumably, many of them were deported to China or North Korea and forced to serve as laborers and soldiers.[78] The Kuril Islands dispute is a source of contemporary anti-Japanese sentiment in Russia.[citation needed]

United Kingdom

[edit]In the 1902, the United Kingdom signed a formal military alliance with Japan. However, the alliance was especially discontinued in 1923, and by the 1930s, bilateral ties became strained when Britain opposed Japan's military expansion. During World War II, British anti-Japanese propaganda, much like its American counterpart, featured content that grotesquely exaggerated physical features of Japanese people, if not outright depicting them as animals such as spiders.[79] Post-war, much anti-Japanese sentiment in Britain was focused on the treatment of British POWs (See The Bridge on the River Kwai).

United States

[edit]Pre-20th century

[edit]In the United States, anti-Japanese sentiment had its beginnings long before World War II. As early as the late 19th century, Asian immigrants were subjected to racial prejudice in the United States. Laws were passed which openly discriminated against Asians and sometimes, they particularly discriminated against Japanese. Many of these laws stated that Asians could not become US citizens and they also stated that Asians could not be granted basic rights such as the right to own land. These laws were greatly detrimental to the newly arrived immigrants because they denied them the right to own land and forced many of them who were farmers to become migrant workers. Some cite the formation of the Asiatic Exclusion League as the start of the anti-Japanese movement in California.[80]

Early 20th century

[edit]

Anti-Japanese racism and the belief in the Yellow Peril in California intensified after the Japanese victory over the Russian Empire during the Russo-Japanese War. On 11 October 1906, the San Francisco, California Board of Education passed a regulation in which children of Japanese descent would be required to attend racially-segregated separate schools. Japanese immigrants then made up approximately 1% of the population of California, and many of them had come under the treaty in 1894 which had assured free immigration from Japan.

The Japanese invasion of Manchuria, China, in 1931 and was roundly criticized in the US. In addition, efforts by citizens outraged at Japanese atrocities, such as the Nanking Massacre, led to calls for American economic intervention to encourage Japan to leave China. The calls played a role in shaping American foreign policy. As more and more unfavorable reports of Japanese actions came to the attention of the American government, embargoes on oil and other supplies were placed on Japan out of concern for the Chinese people and for the American interests in the Pacific. Furthermore, European-Americans became very pro-China and anti-Japan, an example being a grassroots campaign for women to stop buying silk stockings because the material was procured from Japan through its colonies.

When the Second Sino-Japanese War broke out in 1937, Western public opinion was decidedly pro-China, with eyewitness reports by Western journalists on atrocities committed against Chinese civilians further strengthening anti-Japanese sentiments. African-American sentiments could be quite different than the mainstream and included organizations like the Pacific Movement of the Eastern World (PMEW), which promised equality and land distribution under Japanese rule. The PMEW had thousands of members hopefully preparing for liberation from white supremacy with the arrival of the Japanese Imperial Army.

World War II

[edit]

The most profound cause of anti-Japanese sentiment outside of Asia started by the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor, which propelled the United States into World War II. The Americans were unified by the attack to fight the Empire of Japan and its allies: the German Reich and the Kingdom of Italy.

The surprise attack on Pearl Harbor without a declaration of war was commonly regarded as an act of treachery and cowardice. After the attack, many non-governmental "Jap hunting licenses" were circulated around the country. Life magazine published an article on how to tell the difference between Japanese and Chinese by describing the shapes of their noses and the statures of their bodies.[81] Additionally, Japanese conduct during the war did little to quell anti-Japanese sentiment. The flames of outrage were fanned by the treatment of American and other prisoners-of-war (POWs). The Japanese military's outrages included the murder of POWs, the use of POWs as slave laborers by Japanese industries, the Bataan Death March, the kamikaze attacks on Allied ships, the atrocities which were committed on Wake Island, and other atrocities which were committed elsewhere.[citation needed]

The US historian James J. Weingartner attributes the very low number of Japanese in US POW compounds to two key factors: a Japanese reluctance to surrender and a widespread American "conviction that the Japanese were 'animals' or 'subhuman' and unworthy of the normal treatment accorded to POWs."[82] The latter reasoning is supported by Niall Ferguson: "Allied troops often saw the Japanese in the same way that Germans regarded Russians [sic] — as Untermenschen."[83] Weingartner believed that to explain why merely 604 Japanese captives were alive in Allied POW camps by October 1944.[84] Ulrich Straus, a US Japanologist, wrote that frontline troops intensely hated Japanese military personnel and were "not easily persuaded" to take or protect prisoners, as they believed that Allied personnel who surrendered got "no mercy" from the Japanese.[85]

Allied soldiers believed that Japanese soldiers were inclined to feign surrender in order to launch surprise attacks.[85] Therefore, according to Straus, "[s]enior officers opposed the taking of prisoners[,] on the grounds that it needlessly exposed American troops to risks...."[85]

An estimated 112,000 to 120,000 Japanese migrants and Japanese Americans from the West Coast were interned regardless of their attitude to the US or to Japan. They were held for the duration of the war in the Continental US. Only a few members of the large Japanese population of Hawaii were relocated in spite of the proximity to vital military areas.[citation needed]

A 1944 opinion poll found that 13% of the US public supported the genocide of all Japanese.[86][87] Daniel Goldhagen wrote in his book, "So it is no surprise that Americans perpetrated and supported mass slaughters - Tokyo's firebombing and then nuclear incinerations - in the name of saving American lives, and of giving the Japanese what they richly deserved."[88]

Decision to drop the atomic bombs

[edit]

Weingartner argued that there was a common cause between the mutilation of Japanese war dead and the decision to bomb Hiroshima and Nagasaki.[89] According to Weingartner, both of these decisions were partially the result of the dehumanization of the enemy: "The widespread image of the Japanese as sub-human constituted an emotional context which provided another justification for decisions which resulted in the death of hundreds of thousands."[90] Two days after the Nagasaki bomb, US President Harry Truman stated: "The only language they seem to understand is the one we have been using to bombard them. When you have to deal with a beast you have to treat him like a beast. It is most regrettable but nevertheless true."[84][91]

Postwar

[edit]In the 1970s and the 1980s, the waning fortunes of heavy industry in the United States prompted layoffs and hiring slowdowns just as counterpart businesses in Japan were making major inroads into US markets. That was most visible than in the automobile industry whose lethargic Big Three (General Motors, Ford, and Chrysler) watched as their former customers bought Japanese imports from Honda, Subaru, Mazda, and Nissan because of the 1973 oil crisis and the 1979 energy crisis. (When Japanese automakers were establishing their inroads into the US and Canada. Isuzu, Mazda, and Mitsubishi had joint partnerships with a Big Three manufacturer (GM, Ford, and Chrysler) in which its products were sold as captives). Anti-Japanese sentiment was reflected in opinion polling at the time as well as in media portrayals.[92] Extreme manifestations of anti-Japanese sentiment were occasional public destruction of Japanese cars and in the 1982 murder of Vincent Chin, a Chinese-American who was beaten to death after he had been mistaken for being Japanese.[citation needed]

Anti-Japanese sentiments were intentionally incited by US politicians as part of partisan politics designed to attack the Reagan presidency.[93]

Other highly-symbolic deals, including the sale of famous American commercial and cultural symbols such as Columbia Records, Columbia Pictures, 7-Eleven, and the Rockefeller Center building to Japanese firms, further fanned anti-Japanese sentiment.

Popular culture of the period reflected American's growing distrust of Japan.[citation needed] Futuristic period pieces such as Back to the Future Part II and RoboCop 3 frequently showed Americans as working precariously under Japanese superiors. The film Blade Runner showed a futuristic Los Angeles clearly under Japanese domination, with a Japanese majority population and culture, perhaps[original research?] a reference to the alternate world presented in the novel The Man in the High Castle by Philip K. Dick, the same author on which the film was based in which Japan had won World War II. Criticism was also lobbied in many novels of the day. The author Michael Crichton wrote Rising Sun, a murder mystery (later made into a feature film) involving Japanese businessmen in the US. Likewise, in Tom Clancy's book, Debt of Honor, Clancy implies that Japan's prosperity was caused primarily to unequal trading terms and portrayed Japan's business leaders acting in a power-hungry cabal.[citation needed]

As argued by Marie Thorsten, however, Japanophobia was mixed with Japanophilia during Japan's peak moments of economic dominance in the 1980s. The fear of Japan became a rallying point for techno-nationalism, the imperative to be first in the world in mathematics, science, and other quantifiable measures of national strength necessary to boost technological and economic supremacy. Notorious "Japan-bashing" took place alongside the image of Japan as superhuman, which mimicked in some ways the image of the Soviet Union after it launched the first Sputnik satellite in 1957, and both events turned the spotlight on American education.[citation needed]

US bureaucrats purposely pushed that analogy. In 1982, Ernest Boyer, a former US Commissioner of Education, publicly declared, "What we need is another Sputnik" to reboot American education, and he said that "maybe what we should do is get the Japanese to put a Toyota into orbit."[94] Japan was both a threat and a model for human resource development in education and the workforce, which merged with the image of Asian-Americans as the "model minority."[citation needed]

Both the animosity and the superhumanizing peaked in the 1980s, when the term "Japan bashing" became popular, but had largely faded by the late 1990s. Japan's waning economic fortunes in the 1990s, now known as the Lost Decade, coupled with an upsurge in the US economy as the Internet took off, largely crowded anti-Japanese sentiment out of the popular media.[citation needed]

Yasukuni Shrine

[edit]The Yasukuni Shrine is a Shinto shrine in Tokyo, Japan. It is the resting place of thousands of not only Japanese soldiers, but also Korean and Taiwanese soldiers killed in various wars, mostly in World War II. The shrine includes 13 Class A criminals such as Hideki Tojo and Kōki Hirota, who were convicted and executed for their roles in the Japanese invasions of China, Korea, and other parts of East Asia after the remission to them under the Treaty of San Francisco. A total of 1,068 convicted war criminals are enshrined at the Yasukuni Shrine.[citation needed]

In recent years, the Yasukuni Shrine has become a sticking point in the relations of Japan and its neighbours. The enshrinement of war criminals has greatly angered the people of various countries invaded by Imperial Japan. In addition, the shrine published a pamphlet stating that "[war] was necessary in order for us to protect the independence of Japan and to prosper together with our Asian neighbors" and that the war criminals were "cruelly and unjustly tried as war criminals by a sham-like tribunal of the Allied forces". While it is true that the fairness of these trials is disputed among jurists and historians in the West as well as in Japan, the former Prime Minister of Japan, Junichiro Koizumi, has visited the shrine five times; every visit caused immense uproar in China and South Korea. His successor, Shinzo Abe, was also a regular visitor of Yasukuni. Some Japanese politicians have responded by saying that the shrine, as well as visits to it, is protected by the constitutional right of freedom of religion. Yasuo Fukuda, chosen Prime Minister in September 2007, promised "not to visit" Yasukuni.[95]

Derogatory terms

[edit]There are a variety of derogatory terms referring to Japan. Many of these terms are viewed as racist. However, these terms do not necessarily refer to the Japanese race as a whole; they can also refer to specific policies, or specific time periods in history.

In English

[edit]- Especially prevalent during World War II, the word "Jap" (short for Japanese) or "Nip" (short for Nippon, Japanese for "Japan" or Nipponjin for "Japanese person") has been used mostly in America, Great Britain, Canada, Australia, New Zealand, and Singapore as a derogatory word for the Japanese throughout the 19th and the 20th century when they came to Western countries, mostly the United States in large numbers. During WW2, some in the United States Marine Corps tried to combine the word Japs with apes to create a new description, Japes, for the Japanese, although this slur never became popular.

- The word Japanazi has also been used in English language media, a combination of the words "Japan" and "Nazi" (after Nazi Germany) as a derogatory word to insult Japan and the Axis powers in general.

In Chinese

[edit]- Riben guizi (Chinese: 日本鬼子; Cantonese: Yaatboon gwaizi; Mandarin: Rìběn guǐzi) – literally "Japanese devils" or "Japanese monsters". This is used mostly in the context of the Second Sino-Japanese War, when Japan invaded and occupied large areas of China. This is the title of a Japanese documentary on Japanese war crimes during WWII. Recently, some Japanese have taken the slur and reversed the negative connotations by transforming it into a cute female personification named Hinomoto Oniko, which is an alternate reading in Japanese.

- Wokou (Chinese: 倭寇; pinyin: wōkòu; Jyutping: wo1 kau3; Cantonese Yale: wō kau) – originally referred to Japanese pirates and armed sea merchants who raided the Chinese coastline during the Ming dynasty. The term was adopted during the Second Sino-Japanese War to refer to invading Japanese forces (similarly to Germans being called "Huns" In France and Britain). The word is today sometimes used to refer to all Japanese people in extremely negative contexts.

- Xiao Riben (Chinese: 小日本; pinyin: xiǎo Rìběn) – literally "puny Japan(ese)", or literally "little Japan(ese)". This term is very common (Google Search returns 21,000,000 results as of August 2007).[needs update] The term can be used to refer to either Japan or individual Japanese people.

- Riben zai (Chinese: 日本仔; pinyin: rì běn zǎi; Jyutping: jat6 bun2 zai2; Cantonese Yale: yaht bún jái) – this is the most common term in use by Cantonese speaking Chinese, having similar meaning to the English word "Jap". The term literally translates to "Japanese kid". This term has become so common that it has little impact and does not seem to be too derogatory compared to other words below.

- Wo (Chinese: 倭; pinyin: wō) – this was an ancient Chinese name for Japan, but was also adopted by the Japanese. Today, its usage in Mandarin is usually intended to give a negative connotation. The character is said to also mean "dwarf", although that meaning was not apparent when the name was first used. See Wa.

- Riben gou (Chinese: 日本狗; pinyin: Rìběn gǒu; Jyutping: jat6 bun2 gau2; Cantonese Yale: yaht bún gáu) – "Japanese dogs". The word is used to refer to all Japanese people in extremely negative contexts.

- Da jiaopen zu (Chinese: 大腳盆族; pinyin: dà jiǎopén zú) – "big foot-basin race". Ethnic slur towards Japanese used predominantly by Northern Chinese, mainly those from the city of Tianjin.

- Huang jun (Chinese: 黃軍; pinyin: huáng jūn) – "Yellow Army", a pun on "皇軍" (homophone huáng jūn, "Imperial Army"), used during World War II to represent Imperial Japanese soldiers due to the colour of the uniform. Today, it is used negatively against all Japanese. Since the stereotype of Japanese soldiers are commonly portrayed in war-related TV series in China as short men, with a toothbrush moustache (and sometimes round glasses, in the case of higher ranks), huang jun is also often used to pull jokes on Chinese people with these characteristics, and thus "appear like" Japanese soldiers. Also, since the colour of yellow is often associated with pornography in modern Chinese, it is also a mockery of the Japanese forcing women into prostitution during World War II.

- Zi wei dui (Chinese: 自慰隊; pinyin: zì wèi duì; Jyutping: zi6 wai3 deoi6; Cantonese Yale: jih wai deuih) – a pun on the homophone "自衛隊" (same pronunciation, "self-defense forces", see Japan Self-Defense Forces), the definition of "慰" (Cantonese: wai3; pinyin: wèi) used is "to comfort". This phrase is used to refer to Japanese (whose military force is known as "自衛隊") being stereotypically hypersexual, as "自慰隊" means "self-comforting forces", referring to masturbation.

- Ga zai / Ga mui (Chinese: 㗎仔 / 㗎妹; Jyutping: gaa4 zai2 / gaa4 mui1; Cantonese Yale: gàh jái / gàh mūi) – used only by Cantonese speakers to call Japanese men / young girls. "㗎" (gaa4) came from the frequent use of simple vowels (-a in this case) in Japanese language. "仔" (zai2) means "little boy(s)", with relations to the stereotype of short Japanese men. "妹" (mui1) means "young girl(s)" (the speaker usually uses a lustful tone), with relations to the stereotype of disrespect to females in Japanese society. Sometimes, ga is used as an adjective to avoid using the proper word "Japanese".

- Law bak tau (Chinese: 蘿蔔頭; pinyin: luo bo tou; Jyutping: lo4 baak6 tau4; Cantonese Yale: lòh baahk tàuh) – "daikon head". Commonly used by the older people in the Cantonese-speaking world to call Japanese men.

In Korean

[edit]- Jjokbari (Korean: 쪽발이) – translates as "a person with cloven hoof-like feet".[96] This term is the most frequently used and strongest ethnic slur used by Koreans to refer to Japanese. Refers to the traditional Japanese footwear of geta or tabi, both of which feature a gap between the big toe and the other four toes. The term compares Japanese to pigs. The term is also used by ethnic Koreans in Japan.[97]

- Seom-nara won-sung-i (Korean: 섬나라 원숭이) – literally "island country monkey", more often translated as simply "island monkey". Common derogatory term comparing Japanese to the Japanese macaque native to Japan.

- Wae-in (Korean: 왜인; Hanja: 倭人) – translates as "small Japanese person", although used with strong derogatory connotations. The term refers to the ancient name of Yamato Japan, Wae, on the basis of the stereotype that Japanese people were small (see Wa).

- Wae-nom (Korean: 왜놈; Hanja: 倭놈) – translates as "small Japanese bastard". It is used more frequently by older Korean generations, derived from the Japanese invasions of Korea (1592–1598).

- Wae-gu (Korean: 왜구; Hanja: 倭寇) – originally referred to Japanese pirates, who frequently invaded Korea. The word is today used to refer to all Japanese people in an extremely negative context.

In Filipino

[edit]- Sakang is a Filipino insult meaning bow-legged, mainly directed towards Japanese people.

In Portuguese

[edit]- Japa is a term used in Brazil to refer to Japanese immigrants and their descendants many times accepted by the Japanese community, not analogous to English Jap.[98]

Other

[edit]- Corona – There have been strong indications that the word "corona", from the coronavirus (referring specifically to the COVID-19 pandemic), has become a relatively common slur toward Japanese people in several Arabic-speaking countries, with the Japanese embassy in Egypt acknowledging that "corona" had become one of the most common slurs at least in that country,[99] as well as incidents against Japanese aid workers in Palestine involving the slur.[100] In Jordan, Japanese people were chased by locals yelling "corona".[101] Outside of the Arabic-speaking world, France has also emerged as a notable country where use of the slur toward Japanese has become common, with targets of the slur ranging from Japanese study tours to Japanese restaurants and Japanese actresses working for French companies such as Louis Vuitton.[99][102][103]

See also

[edit]- Kàngrì (抗日)

- Senkaku Islands

- Japanese war crimes

- 2012 China anti-Japanese demonstrations

- Internment of Japanese Americans

- Internment of Japanese Canadians

- Tanaka Memorial

- Second Sino-Japanese War

- China–Japan relations

- Japan–Russia relations

- Japan–Korea disputes

- Japan–North Korea relations

- Japan–South Korea relations

- Anti-Chinese sentiment

- Anti-Korean sentiment

- Anti-Vietnamese sentiment

- Anti-Japanese propaganda

- Japan–United States relations

- Pacific War

- Anti-Japanese sentiment in the United States

- John P. Irish (1843–1923), fought against anti-Japanese sentiment in California

- Japanese racial equality proposal, 1919

- Racism

- Stereotypes of East Asians in the United States

- Tatarophobia

- United States Executive Order 9066

- Yellow Peril

- Yoshihiro Hattori

References

[edit]- ^ a b c "2017 BBC World Service poll" (PDF). BBC World Service. p. 20. Archived from the original (PDF) on 30 July 2017.

- ^ "Japanese Public's Mood Rebounding, Abe Highly Popular". Pew Research Center. 11 July 2013. Archived from the original on 14 July 2013.

- ^ a b "Positive Views of Brazil on the Rise in 2011 BBC Country Rating Poll" (PDF). BBC World Service. 7 March 2011. p. 10. Archived from the original (PDF) on 25 June 2021.

- ^ Emmott 1993

- ^ "World Publics Think China Will Catch Up With the US—and That's Okay". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 16 July 2011. Retrieved 7 March 2010.

- ^ "Global Poll Finds Iran Viewed Negatively – Europe and Japan Viewed Most Positively". World Public Opinion.org. Archived from the original on 9 April 2006. Retrieved 7 March 2010.

- ^ "Poll: Israel and Iran Share Most Negative Ratings in Global Poll". BBC World Service. 2007. Archived from the original on 30 March 2008. Retrieved 13 April 2008.

- ^ "24-Nation Pew Global Attitudes Survey" (PDF). The Pew Global Attitudes Project. 12 June 2008. Archived from the original (PDF) on 4 July 2008. Retrieved 28 June 2008.

- ^ "China's Bloody Century". Hawaii.edu. Retrieved 21 July 2013.

- ^ "Scarred by history: The Rape of Nanjing". BBC News. 11 April 2005. Retrieved 13 April 2008.

- ^ "Budget for the Destruction of Abandoned Chemical Weapons in China". Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Japan. 24 December 1999. Archived from the original on 25 June 2008. Retrieved 28 June 2008.

- ^ "China Says Japanese Textbooks Distort History". pbs.org Newshour. 13 April 2005. Archived from the original on 14 April 2005. Retrieved 13 April 2008.

- ^ a b c d e f g h SUZUKI Jr, Matinas. História da discriminação brasileira contra os japoneses sai do limbo in Folha de S.Paulo, 20 de abril de 2008 (visitado em 17 de agosto de 2008)

- ^ RIOS, Roger Raupp. Text excerpted from a judicial sentence concerning crime of racism. Archived 8 August 2007 at the Wayback Machine Federal Justice of 10ª Vara da Circunscrição Judiciária de Porto Alegre, 16 November 2001 (Accessed 10 September 2008)

- ^ Memória da Imigração Japonesa Archived 10 May 2013 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ de Souza Rodrigues, Julia; Caballero Lois, Cecilia. "Uma análise da imigração (in) desejável a partir da legislação brasileira: promoção, restrição e seleção na política imigratória".

- ^ Itu.com.br. "A Imigração Japonesa em Itu – Itu.com.br". itu.com.br. Archived from the original on 6 January 2017. Retrieved 4 May 2018.

- ^ Arcanjo, Daniela; Tavares, Joelmir (26 January 2020). "Ofensa a japoneses amplia rol de declarações preconceituosas de Bolsonaro". Folha de S.Paulo (in Brazilian Portuguese). Retrieved 11 June 2021.

- ^ "Em programa de TV, Bolsonaro faz piada homofóbica e sobre asiáticos". Poder360 (in Brazilian Portuguese). 23 April 2021. Retrieved 11 June 2021.

- ^ "The Japan Times". Archived from the original on 12 January 2015. Retrieved 6 April 2020.

- ^ "Coronavirus outbreak stokes anti-Asian bigotry worldwide". 18 February 2020.

- ^ "Coronavírus no Brasil acende alerta para preconceito contra asiáticos | ND". 18 March 2020.

- ^ "Leonardo Sakamoto - Surto de coronavírus lembra racismo e xenofobia contra orientais no Brasil".

- ^ "Mulher borrifa álcool em jovem: "Você é o coronavírus"". Marie Claire (in Brazilian Portuguese). 19 March 2020. Retrieved 29 March 2021.

- ^ Corporation., Canadian Broadcasting (2006). CBC archives. the internment of the Japanese Canadians. Canadian Broadcasting Corp. OCLC 439710706.

- ^ "China and Japan: Seven decades of bitterness". BBC News, 13 February 2014, accessed 14 April 2014

- ^ "[1] Archived 16 April 2014 at the Wayback Machine"

- ^ "People visit Museum of War of Chinese People's Resistance Against Japanese Aggression in Beijing". Xinhuanet, 27 February 2014, accessed 14 April 2014

- ^ Thompson, David (12 January 2025). "The Comfort Women Narrative: How Social Media Amplifies Emotionally Charged, Anti-Japanese Content Over Balanced Research". International Business Times. Retrieved 4 March 2025.

- ^ Matthew Forney (10 December 2005). "Why China Loves to Hate Japan". Time. Retrieved 25 October 2008.

- ^ "Chinese Pop Singer Under Fire for Japan War Flag Dress". China.org, 13 December 2001., accessed 14 April 2014

- ^ "Chinese Media". Lee Chin-Chuan, 2003., accessed 14 April 2014

- ^ Yuan, Li (4 July 2024). "Is Xenophobia on Chinese Social Media Teaching Real-World Hate?". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 24 September 2024. Retrieved 26 September 2024.

- ^ Lague, David (25 May 2013). "Special Report: Why China's film makers love to hate Japan". Reuters. Retrieved 19 October 2013.

- ^ Forney, Matthew (10 December 2005). "Why China Bashes Japan". Time. Archived from the original on 14 December 2005. Retrieved 19 October 2013.

- ^ "海外安全情報 – ラジオ日本". NHK. Archived from the original on 25 February 2020. Retrieved 25 February 2020.

- ^ "日本人女性に「ウイルス!」と暴言 志らくが不快感「どこの国でもこういうのが出てくる」(ENCOUNT)". Yahoo!ニュース (in Japanese). Retrieved 6 February 2020.

- ^ "「マスクをしたアジア人は恐怖」新型ウィルスに対するフランス人の対応は差別か自己防衛か". FNN.jpプライムオンライン (in Japanese). 2 February 2020. Archived from the original on 4 February 2020. Retrieved 6 February 2020.

- ^ "'Coronavirus' sprayed on Japanese restaurant in Paris". The Straits Times. 22 February 2020. Retrieved 25 February 2020.

- ^ "Coronavirus outbreak stokes anti-Asian bigotry worldwide". The Japan Times Online. 18 February 2020. ISSN 0447-5763. Archived from the original on 18 February 2020. Retrieved 18 February 2020.

- ^ "Japanese Man Attacked With Acid in Paris, Sparks Warning to Japanese Community". news.yahoo.com. 18 February 2021. Retrieved 23 February 2021.

- ^ "Japanese citizen injured in Paris acid attack". Japan Today. 22 February 2021. Retrieved 23 February 2021.

- ^ "パリ在住の中村江里子、長女も電話で「日本語で話さないで」コロナ禍アジア人差別実感(デイリースポーツ)". Yahoo!ニュース (in Japanese). Archived from the original on 24 March 2021. Retrieved 27 March 2021.

- ^ a b "「複数国で日本人差別」 外務省、新型コロナ巡り". 日本経済新聞 電子版 (in Japanese). 18 March 2020. Retrieved 11 April 2020.

- ^ "新型コロナウイルス 世界に広がる東洋人嫌悪". Newsweek日本版 (in Japanese). 4 February 2020. Retrieved 11 March 2020.

- ^ "'This is racism': Japanese fans kicked out of football match over coronavirus fears". au.sports.yahoo.com. 3 March 2020. Retrieved 11 March 2020.

- ^ "いよいよドイツもパニックか 買い占めにアジア人差別 日本人も被害に". Newsweek日本版 (in Japanese). 4 March 2020. Retrieved 11 March 2020.

- ^ "ぜんじろう「日本人が全部買い占めてる」欧州でデマ". www.msn.com. Retrieved 11 March 2020.

- ^ "新型肺炎に関するセミナーの実施". www.id.emb-japan.go.jp. Retrieved 10 March 2020.

- ^ "「感染源」日本人に冷視線 入店や乗車拒否 インドネシア(時事通信)". Yahoo!ニュース (in Japanese). Archived from the original on 12 March 2020. Retrieved 10 March 2020.

- ^ "「日本人が感染源」 インドネシアで邦人にハラスメント:朝日新聞デジタル". 朝日新聞デジタル (in Japanese). 9 March 2020. Retrieved 10 March 2020.

- ^ "Munhwa Newspaper (in Korean)". Retrieved 8 May 2008.

- ^ Chun Chang-hyeop (전창협); Hong Seung-wan(홍승완) (8 May 2008). "60th Anniversary of Independence. Half of 20s view Japan as a distant neighbor. [오늘 광복60년 20대 절반 日 여전히 먼나라]". Herald media(헤럴드 경제) (in Korean). Retrieved 29 April 2012.

- ^ "Israel and Iran Share Most Negative Ratings in Global Poll" (PDF). BBC World service poll. March 2007. p. 9. Archived from the original (PDF) on 5 October 2007. Retrieved 29 April 2012.

The two exceptions to this positive reputation for Japan continue to be neighbours China and South Korea, where majorities rate it quite negatively. Views are somewhat less negative in China compared to a year ago (71%[2006] down to 63%[2007] negative) and slightly more negative in South Korea (54%[2006] to 58%[2007] negative).

- ^ "BBC World Service Poll: Global Views of Countries, Questionnaire and Methodology" (PDF). Program on International Policy Attitudes(PIPA). February 2006. p. 9. Archived from the original (PDF) on 29 March 2012. Retrieved 29 April 2012.

- ^ "Jiritsu じりつ: La Liga Anti-Asiática (Lima, 1917)". Jiritsu じりつ. 7 May 2019. Retrieved 10 May 2023.

- ^ a b c d Hua, Lillian (6 June 2021). "Adios to Justice: Japanese Peruvians, National Formations, and the Politics of Legal Redress". The Yale Review of International Studies. Retrieved 10 May 2023.

- ^ a b DuMontier (2018). Between Menace and Model Citizen: Lima's Japanese Peruvians, 1936–1963 (Doctor of Philosophy thesis). University of Arizona.

- ^ a b DuMontier (2018). Between Menace and Model Citizen: Lima's Japanese Peruvians, 1936–1963 (Doctor of Philosophy thesis). University of Arizona.

- ^ "The Lesser Known Japanese Internment · Narratives of World War II in the Pacific · Bell Library Exhibits". library.tamucc.edu. Retrieved 10 May 2023.

- ^ Barnhart, Edward N. "Japanese Internees from Peru," Pacific Historical Review. 31:2, 169–178 (May 1962).

- ^ Weglyn, Michi Nishiura (1976). Years of Infamy: The Untold Story of America's Concentration Camps. New York: William Morrow & Company. p. 64. ISBN 978-0688079963.

- ^ Berrios, Ruben (1 January 2005). "Peru and Japan: an uneasy relationship". Canadian Journal of Latin American and Caribbean Studies. 30 (59): 93–130.

- ^ "Japan Concerned about Anti-Japan Sentiment in Peru Over Fujimori". Al Bawaba. Retrieved 10 May 2023.

- ^ Conde, Carlos H. (13 August 2005). "Letter from the Philippines: Long afterward, war still wears onFilipinos". The New York Times.

- ^ Herbert curtis (13 January 1942). "Japanese Infiltration Into Mindanao". The Vancouver Sun. p. 4. Retrieved 16 May 2014.

- ^ Filipino Heritage: The Spanish colonial period (late 19th century). Manila: Lahing Pilipino Pub. 1978. p. 1702.

- ^ Filipinas. Vol. 11. Filipinas Pub. 2002.Issues 117–128

- ^ Peter G. Gowing (1988). Understanding Islam and Muslims in the Philippines. New Day Publishers. p. 56. ISBN 978-971-10-0386-9.

- ^ Bijdragen tot de taal-, land- en volkenkunde van Nederlandsch-Indië. Vol. 129. M. Nijhoff. 1973. p. 111.

- ^ Liu, Joseph Woon Keong (2020). "Constructions of Japan and the Japanese : War, memory and foreign policy in Singapore".

- ^ Cheung, Han. "Taiwan in Time: The rehabilitation of Eastern gouache". Taipei Times. Retrieved 6 February 2021.

- ^ Shinichi Ichimura (29 June 2013). Political Economy of Japanese and Asian Development. Springer Japan. p. 49.

- ^ "台湾が「親日」で、韓国が「反日」な理由" [The reason why Taiwan is 'pro-Japanese' and Korea is 'anti-Japanese']. HuffPost (in Japanese). 11 November 2013.

- ^ "Why Taiwanese are pro-Japan but anti-China". ThinkChina. 19 October 2020.

- ^ Various, Editorials. The Yomiuri Shimbun, 18 June 2008. (in Japanese), accessed 8 July 2008 Archived 20 March 2014 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Pro-democracy protests lead to anti-Japan movement: Saha Group chairman's story (17)". Nikkei Asia. Retrieved 25 July 2022.

- ^ "Russia Acknowledges Sending Japanese Prisoners of War to North Korea". Mosnews.com. 1 April 2005. Archived from the original on 13 November 2006. Retrieved 23 February 2007.

- ^ Archives, The National (10 August 2020). "The National Archives - Depicting Japan in British propaganda of the Second World War". The National Archives blog. Retrieved 25 July 2022.

- ^ Brian Niiya (1993). Japanese American History: An A-to-Z Reference from 1868 to the Present (illustrated ed.). Verlag für die Deutsche Wirtschaft AG. pp. M1 37, 103–104. ISBN 978-0-8160-2680-7.

- ^ Luce, Henry, ed. (22 December 1941). "How to tell Japs from the Chinese". Life. Vol. 11, no. 25. Chicago: Time Inc. pp. 81–82. Retrieved 19 February 2010.

- ^ Weingartner 1992, p. 55

- ^ Ferguson, Niall (2004). "Prisoner Taking and Prisoner Killing in the Age of Total War: Towards a Political Economy of Military Defeat". War in History. 11 (2): 148–192. doi:10.1191/0968344504wh291oa. JSTOR 26061867. S2CID 159610355.

- ^ a b Weingartner 1992, p. 54

- ^ a b c Straus, Ulrich (2003). The Anguish Of Surrender: Japanese POWs of World War II (excerpts). Seattle: University of Washington Press. p. 116. ISBN 978-0-295-98336-3.

- ^ Bagby 1999, p. 135

- ^ N. Feraru (17 May 1950). "Public Opinion Polls on Japan". Far Eastern Survey. 19 (10). Institute of Pacific Relations: 101–103. doi:10.2307/3023943. JSTOR 3023943.

- ^ Goldhagen, Daniel Jonah (2009). Worse Than War: Genocide, Eliminationism, and the Ongoing Assault on Humanity. PublicAffairs. p. 201. ISBN 978-0-7867-4656-9.

- ^ Weingartner 1992, pp. 55–56

- ^ Weingartner 1992, p. 67

- ^ Weingardner further attributed the Truman quote to Ronald Schaffer.Schaffer 1985, p. 171

- ^ Heale, M. J. (2009). "Anatomy of a Scare: Yellow Peril Politics in America, 1980–1993". Journal of American Studies. 43 (1): 19–47. doi:10.1017/S0021875809006033. ISSN 1469-5154. S2CID 145252539.

- ^ .Heale, M (2009). "Anatomy of a Scare: Yellow Peril Politics in America, 1980–1993". Journal of American Studies. 43 (1): 19–47. doi:10.1017/S0021875809006033. JSTOR 40464347. S2CID 145252539.

- ^ Thorsten 2012, p. 150n1

- ^ Blaine Harden, "Party Elder To Be Japan's New Premier", Washington Post, 24 September 2007

- ^ "Definition of Jjokbari". Naver Korean Dictionary.

a derogatory term for Japanese. It refers to Japanese traditional footwear Geta, which separates the thumb toe and the other four toes. [일본 사람을 낮잡아 이르는 말. 엄지발가락과 나머지 발가락들을 가르는 게다를 신는다는 데서 온 말이다.]

- ^ Constantine 1992

- ^ Ito, Carol (12 March 2020). "Meu nome não é japa: o preconceito amarelo". Trip (in Brazilian Portuguese). Retrieved 23 March 2021.

- ^ a b "Coronavirus outbreak stokes anti-Asian bigotry worldwide". The Japan Times Online. 18 February 2020. ISSN 0447-5763. Retrieved 9 March 2020.

- ^ "As coronavirus spreads, fear of discrimination rises". NHK WORLD. Retrieved 9 March 2020.

- ^ "海外安全情報 – ラジオ日本 – NHKワールド – 日本語". NHK WORLD (in Japanese). Archived from the original on 11 March 2020. Retrieved 11 March 2020.

- ^ "'Coronavirus' sprayed on Japanese restaurant in Paris". The Straits Times. 22 February 2020. Retrieved 9 March 2020.

- ^ "Anti-Asian hate, the new outbreak threatening the world". Nikkei Asian Review. Retrieved 9 March 2020.

Bibliography

[edit]- Bagby, Wesley Marvin (1999). America's International Relations Since World War I. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-512389-1.

- Chang, Maria Hsia, and Robert P. Barker. "Victor's justice and Japan's amnesia: The Tokyo war crimes trial reconsidered." East Asia: An International Quarterly 19.4 (2001): 55.

- Constantine, Peter (1992). Japanese Street Slang. Weatherhill. ISBN 0-8348-0250-3.

- Corbett, P. Scott. In the eye of a Hurricane: Americans in Japanese custody during World War II (Routledge, 2007).

- Dower, John. War without mercy: Race and power in the Pacific War (Pantheon, 2012).

- Emmott, Bill (1993). Japanophobia: The Myth of the Invincible Japanese. Times Books. ISBN 0-8129-1907-6.

- Futamura, Madoka. War crimes tribunals and transitional justice: The Tokyo trial and the Nuremberg legacy (Routledge, 2007). online

- MacArthur, Brian. Surviving the Sword: Prisoners of the Japanese in the Far East, 1942-45 (Random House, 2005).

- Maga, Timothy P. Judgment at Tokyo: the Japanese war crimes trials (University Press of Kentucky, 2001).

- Monahan, Evelyn, and Rosemary Neidel-Greenlee. All this hell: US nurses imprisoned by the Japanese (University Press of Kentucky, 2000).

- Navarro, Anthony V. (12 October 2000). "A Critical Comparison Between Japanese and American Propaganda during World War II".

- Nie, Jing-Bao. "The United States cover-up of Japanese wartime medical atrocities: Complicity committed in the national interest and two proposals for contemporary action." American Journal of Bioethics 6.3 (2006): W21-W33.

- Roces, Alfredo R. (1978). Filipino Heritage: The Spanish colonial period (late 19th century). Vol. 7 of Filipino Heritage: The Making of a Nation. Lahing Pilipino Pub. ; [Manila]. Retrieved 10 March 2014.

- Schaffer, Ronald (1985). Wings of Judgement: American Bombing in World War II. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Tanaka, Yuki, and John W. Dower. Hidden horrors: Japanese war crimes in World War II (Routledge, 2019).

- Thorsten, Marie (2012). Superhuman Japan. Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-41426-5.

- Totani, Yuma. The Tokyo War Crimes Trial: The Pursuit of Justice in the Wake of World War II (Harvard University Asia Center Publications Program, 2008) online review

- Tsuchiya, Takashi. "The imperial Japanese experiments in China." in The Oxford textbook of clinical research ethics (2008) pp: 31-45.

- Twomey, Christina. "Double displacement: Western women's return home from Japanese internment in the Second World War." Gender & History 21.3 (2009): 670-684. focus on British women

- Weingartner, James J. (February 1992). "Trophies of War: U.S. Troops and the Mutilation of Japanese War Dead, 1941–1945". Pacific Historical Review. 61 (1): 53–67. doi:10.2307/3640788. ISSN 0030-8684. JSTOR 3640788. S2CID 159919957.

- Yap, Felicia. "Prisoners of war and civilian internees of the Japanese in British Asia: the similarities and contrasts of experience." Journal of Contemporary History 47.2 (2012): 317-346.

- Filipinas, Volume 11, Issues 117-128. Filipinas Pub. 2002. Retrieved 10 March 2014.

- Bijdragen tot de taal-, land- en volkenkunde van Nederlandsch-Indië, Volume 129. Contributor Koninklijk Instituut voor Taal-, Land- en Volkenkunde (Netherlands). M. Nijhoff. 1973. Retrieved 10 March 2014.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: others (link)

External links

[edit]- China's angry young focus their hatred on old enemy

- The Impact of Asian-Pacific Migration on U.S. Immigration Policy

- Kahn, Joseph. China Is Pushing and Scripting Anti-Japanese Protests. The New York Times. 15 April 2005

Anti-Japanese sentiment

View on GrokipediaConceptual Foundations

Definition and Scope

Anti-Japanese sentiment refers to prejudice, hostility, or discriminatory actions directed against individuals of Japanese descent, Japanese nationals, or the Japanese nation as a whole, often manifesting as negative stereotypes, exclusionary policies, or violence rooted in perceived threats or historical animosities.[10] This differs from broader xenophobia by its specific focus on Japanese identity, including portrayals of Japanese people as collectively militaristic, deceitful, or economically predatory, which have been perpetuated through wartime propaganda and unresolved grievances. Such sentiment typically exceeds factual assessment of government actions, incorporating irrational generalizations about an entire ethnic group. The scope of anti-Japanese sentiment spans multiple continents and eras, with roots traceable to Japan's Meiji-era industrialization and imperial ambitions in the late 19th century, which provoked fears in neighboring Asian states and Western powers.[11] It intensified globally during World War II, where Allied nations interned over 120,000 Japanese Americans in the United States from 1942 to 1945, citing security risks unsubstantiated by intelligence, amid widespread public support for exclusion driven by racial fears.[12] Postwar, it persisted in East Asia through state-sponsored narratives emphasizing Japan's wartime atrocities, such as the 1937 Nanjing Massacre, fueling periodic outbursts like China's 2012 protests over the Senkaku/Diaoyu Islands dispute, which involved attacks on Japanese businesses and vehicles, causing damages estimated at over 10 billion yuan.[13] In Western contexts, economic manifestations emerged in the 1980s U.S. "Japan bashing," where perceptions of unfair trade practices led to congressional hearings and cultural depictions of Japan as a ruthless competitor, correlating with a 20-30% decline in Japanese car imports due to consumer boycotts.[14] While less prevalent today in the West, residual forms appear in media or online discourse, whereas in Asia, territorial frictions and educational curricula sustain higher levels, with surveys indicating 80-90% unfavorable views of Japan among Chinese and South Korean publics as of 2020.[15] This global variance underscores how local histories shape its intensity, from institutional policies to mob violence, without conflating it with justified opposition to specific Japanese foreign policies.Distinction from Legitimate Criticism of Japanese Policies

Criticism of Japanese policies becomes anti-Japanese sentiment when it shifts from evidence-based evaluation of specific governmental or institutional actions to irrational generalizations attributing inherent negative traits—such as deceitfulness, aggression, or cultural inferiority—to Japanese people as an ethnic group.[16] Legitimate criticism, by contrast, remains targeted, empirical, and open to counterarguments, focusing on measurable outcomes like economic data, environmental impacts, or human rights records without invoking stereotypes rooted in historical animus. This boundary is evident in analyses of 1980s U.S.-Japan trade disputes, where factual concerns over Japan's $50 billion annual trade surplus with the U.S. in 1987—driven by non-tariff barriers and currency undervaluation—degenerated into ethnic slurs like "yellow peril" rhetoric when critics extrapolated policy choices to innate national character.[16] One domain of legitimate policy critique involves Japan's whaling practices, which have persisted despite a 1986 International Whaling Commission (IWC) moratorium on commercial hunting. In 2019, Japan withdrew from the IWC to resume commercial whaling in its exclusive economic zone, catching species like minke whales, a move decried by conservationists for lacking sufficient scientific justification and undermining global biodiversity efforts, as the program's prior "scientific" hunts yielded data deemed redundant by the International Court of Justice in 2014.[17][18] Australia's government, for instance, expressed "deep disappointment" in 2024 over Japan's expansion to include vulnerable fin whales, citing risks to endangered populations without evidence of sustainable management.[19] Such objections rest on verifiable data from marine population surveys and treaty obligations, not cultural disdain for Japanese traditions. Japan's immigration framework provides another example, where restrictive policies—such as indefinite detention of asylum seekers and low refugee acceptance rates (just 202 granted in 2022 out of 10,375 applications)—have been faulted for exacerbating demographic decline, with the working-age population shrinking by 0.8 million annually amid a fertility rate of 1.26 births per woman in 2023.[20][21] Human rights organizations highlight systemic failures, including poor detention conditions leading to deaths, as violations of international standards under the UN Refugee Convention, which Japan ratified in 1981.[22] These critiques emphasize policy-induced labor shortages, projected to reduce GDP growth by 0.5-1% yearly without reform, rather than portraying Japanese society as innately exclusionary.[23] Debates over historical accountability, particularly government-approved textbooks that minimize wartime events like the Nanjing Massacre (estimated 200,000-300,000 deaths in 1937-1938 per multiple eyewitness accounts), illustrate the line's fragility.[24] Criticisms target specific omissions—such as downplaying forced labor in Korea or comfort women systems affecting up to 200,000 women—as impediments to regional trust, backed by declassified Allied records and survivor testimonies, without denying Japan's post-1945 democratization or economic contributions.[25] When such discourse invokes perpetual "Japanese militarism" as an ethnic destiny, echoing wartime propaganda, it veers into prejudice, as seen in sporadic East Asian protests conflating policy with collective guilt. Maintaining the distinction fosters accountability: empirical policy scrutiny has prompted shifts, like Japan's 2018 immigration expansion to admit 345,000 foreign workers over five years, addressing causal labor gaps without ethnic animus.[26]Historical Origins and Causes

Pre-Imperial Era Instances

Instances of antagonism toward Japan predating its modern imperial expansion emerged primarily in East Asia due to maritime raids and military incursions. During the 14th to 16th centuries, wokou—raiders often of Japanese origin, sometimes allied with Chinese outlaws—conducted repeated coastal attacks on Ming China, devastating regions along the southeastern seaboard and prompting defensive fortifications and military campaigns by Chinese authorities.[27] These incursions, peaking in the Jiajing era (1521–1567), involved plundering villages, enslaving inhabitants, and disrupting trade, fostering perceptions of Japanese as predatory seafaring threats in Chinese historical records.[28] Similar wokou activities plagued Joseon Korea, where raids exacerbated border insecurities and contributed to enduring narratives of Japanese aggression in Korean chronicles.[28] The scale of destruction—estimated to have affected thousands of coastal settlements—instilled localized hostility, though interactions remained limited by Japan's internal fragmentation and Korea's tributary relations with China. A more acute episode unfolded with Toyotomi Hideyoshi's invasions of Korea (1592–1598), launched as a stepping stone for continental conquest. Japanese forces, numbering over 150,000 in the initial wave, rapidly overran much of the peninsula, committing widespread atrocities including mass executions, village burnings, and cultural looting, such as the seizure of royal archives and artisans.[29] These actions, resisted fiercely by Korean naval and Ming Chinese reinforcements, resulted in hundreds of thousands of Korean deaths and deepened generational resentment, evident in Joseon-era literature and memorials portraying the invaders as barbaric.[30] The failed campaigns, culminating in Hideyoshi's death in 1598, did not erase the trauma, which persisted in Korean collective memory independent of later colonial rule.[31] Beyond East Asia, pre-19th-century European encounters with Japan were minimal and trade-oriented, yielding no documented widespread prejudice; Portuguese and Dutch traders from the 1540s onward viewed Japan pragmatically as a commercial partner rather than a target of enmity.[32] Thus, pre-imperial anti-Japanese sentiment was regionally confined, rooted in tangible depredations rather than ideological or racial abstractions.Imperial Expansion and Atrocities (1894-1945)

Japan's victory in the First Sino-Japanese War (1894–1895) marked the onset of its imperial expansion in East Asia, resulting in the Treaty of Shimonoseki, which ceded Taiwan, the Pescadores Islands, and the Liaodong Peninsula to Japan, while affirming Japanese dominance over Korea.[33] During the campaign, Japanese forces committed atrocities, including the Port Arthur Massacre in November 1894, where thousands of Chinese soldiers and civilians were killed after the city's fall, contributing to early anti-Japanese resentment amid reports of excessive brutality beyond military necessity. This war transformed perceptions of Japan from a victim of Western imperialism to an aggressor, fostering lasting bitterness in China over territorial losses and perceived humiliations.[34] The Russo-Japanese War (1904–1905) further solidified Japan's regional power, with victories securing influence in southern Manchuria and Korea, culminating in the 1910 annexation of Korea as a colony.[35] Japanese colonial administration in Korea suppressed Korean culture, language, and independence movements, enforcing assimilation policies and exploiting resources, which bred widespread resentment among Koreans, evident in uprisings like the 1919 March First Movement where thousands protested against Japanese rule.[36] Harsh suppression, including mass arrests and executions, intensified anti-Japanese sentiment, framing Japan as an oppressive occupier rather than a modernizer.[37] The Manchurian Incident of September 18, 1931, involved a staged explosion on the Japanese-controlled South Manchuria Railway, providing pretext for the Kwantung Army's invasion and occupation of Manchuria, leading to the puppet state of Manchukuo in 1932.[38] This aggression sparked massive anti-Japanese boycotts and protests across China, with economic sanctions and volunteer armies forming in response, heightening nationalist fervor against Japanese expansionism.[39] The invasion displaced populations and involved reprisals against Chinese resistors, deepening regional animus toward Japan as an unprovoked conqueror.[40] The Second Sino-Japanese War erupted in July 1937 following the Marco Polo Bridge Incident, escalating into full-scale invasion with atrocities like the Nanjing Massacre (December 1937–January 1938), where Japanese troops systematically killed Chinese civilians and disarmed soldiers, looted, and raped on a massive scale. Credible estimates place the death toll at 40,000 to over 200,000, based on contemporaneous accounts and post-war tribunals, though exact figures remain disputed due to incomplete records and denialist claims. Throughout the war, Japanese forces conducted scorched-earth campaigns, killing millions of Chinese civilians through bombings, mass executions, and forced labor, embedding profound hatred rooted in direct experiences of brutality.[41] Japan's entry into World War II via the Pacific expansion from 1941 onward amplified atrocities across Asia-Pacific, including the Bataan Death March in April 1942, where 75,000 American and Filipino prisoners endured forced marches with inadequate food and water, resulting in 5,000 to 18,000 deaths from exhaustion, starvation, and executions.[41] In occupied territories, programs like Unit 731 conducted lethal human experiments on thousands of prisoners, including vivisections and biological weapons tests, primarily on Chinese and Allied captives, while the comfort women system forcibly recruited up to 200,000 women from Korea, China, and Southeast Asia for sexual slavery.[42] These systematic violations, documented in Allied trials and survivor testimonies, cemented anti-Japanese sentiment as a visceral response to unrepentant militarism and dehumanization.[41]Economic and Immigration-Related Factors in the West