Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Organism

View on Wikipedia

An organism is any living thing that functions as an individual.[1] Such a definition raises more problems than it solves, not least because the concept of an individual is also difficult. Several criteria, few of which are widely accepted, have been proposed to define what constitutes an organism. Among the most common is that an organism has autonomous reproduction, growth, and metabolism. This would exclude viruses, even though they evolve like organisms.

Other problematic cases include colonial organisms; a colony of eusocial insects is organised adaptively, and has germ-soma specialisation, with some insects reproducing, others not, like cells in an animal's body. The body of a siphonophore, a jelly-like marine animal, is composed of organism-like zooids, but the whole structure looks and functions much like an animal such as a jellyfish, the parts collaborating to provide the functions of the colonial organism.

The evolutionary biologists David Queller and Joan Strassmann state that "organismality", the qualities or attributes that define an entity as an organism, has evolved socially as groups of simpler units (from cells upwards) came to cooperate without conflicts. They propose that cooperation should be used as the "defining trait" of an organism. This would treat many types of collaboration, including the fungus/alga partnership of different species in a lichen, or the permanent sexual partnership of an anglerfish, as an organism.

Etymology

[edit]The term "organism" (from the Ancient Greek ὀργανισμός, derived from órganon, meaning 'instrument, implement, tool', 'organ of sense', or 'apprehension')[2][3] first appeared in the English language in the 1660s with the now-obsolete meaning of an organic structure or organization.[3] It is related to the verb "organize".[3] In his 1790 Critique of Judgment, Immanuel Kant defined an organism as "both an organized and a self-organizing being".[4][5]

Whether criteria exist, or are needed

[edit]

Among the criteria that have been proposed for being an organism are:

- autonomous reproduction, growth, and metabolism[7]

- noncompartmentability – structure cannot be divided without losing functionality.[6] Richard Dawkins stated this as "the quality of being sufficiently heterogeneous in form to be rendered non-functional if cut in half".[8] However, many organisms can be cut into pieces which then grow into whole organisms.[8]

- individuality – the entity has simultaneous holdings of genetic uniqueness, genetic homogeneity and autonomy[9]

- an immune response, separating self from foreign[10]

- "anti-entropy", the ability to maintain order, a concept first proposed by Erwin Schrödinger;[11] or in another form, that Claude Shannon's information theory can be used to identify organisms as capable of self-maintaining their information content[12]

Other scientists think that the concept of the organism is inadequate in biology;[13] that the concept of individuality is problematic;[14] and from a philosophical point of view, question whether such a definition is necessary.[15][16][8]

Problematic cases include colonial organisms: for instance, a colony of eusocial insects fulfills criteria such as adaptive organisation and germ-soma specialisation.[17] If so, the same argument, or a criterion of high co-operation and low conflict, would include some mutualistic (e.g. lichens) and sexual partnerships (e.g. anglerfish) as organisms.[18] If group selection occurs, then a group could be viewed as a superorganism, optimized by group adaptation.[19]

Another view is that attributes like autonomy, genetic homogeneity and genetic uniqueness should be examined separately, rather than requiring that an organism possess all of them. On this view, there are multiple dimensions to biological individuality, resulting in several types of organism.[20]

Organisms at differing levels of biological organisation

[edit]

Differing levels of biological organisation give rise to potentially different understandings of the nature of organisms. A unicellular organism is a microorganism such as a protist, bacterium, or archaean, composed of a single cell, which may contain functional structures called organelles.[22] A multicellular organism such as an animal, plant, fungus, or alga is composed of many cells, often specialised.[22] A colonial organism such as a siphonophore is a being which functions as an individual but is composed of communicating individuals.[8] A superorganism is a colony, such as of ants, consisting of many individuals working together as a single functional or social unit.[23][17] A mutualism is a partnership of two or more species which each provide some of the needs of the other. A lichen consists of fungi and algae or cyanobacteria, with a bacterial microbiome; together, they are able to flourish as a kind of organism, the components having different functions, in habitats such as dry rocks where neither could grow alone.[18][21] The evolutionary biologists David Queller and Joan Strassmann state that "organismality" has evolved socially, as groups of simpler units (from cells upwards) came to cooperate without conflicts. They propose that cooperation should be used as the "defining trait" of an organism.[18]

| Level | Example | Composition | Metabolism, growth, reproduction |

Co-operation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Virus | Tobacco mosaic virus | Nucleic acid, protein | No | No metabolism, so not living, not an organism, say many biologists;[7] but they evolve, their genes collaborating to manipulate the host[18] |

| Unicellular organism | Paramecium | One cell, with organelles e.g. cilia for specific functions | Yes | Inter-cellular (inter-organismal) signalling[22] |

| Swarming protistan | Dictyostelium (cellular slime mould) | Unicellular amoebae | Yes | Free-living unicellular amoebae for most of lifetime; swarm and aggregate to a multicellular slug, cells specialising to form a dead stalk and a fruiting body[18] |

| Multicellular organism | Mushroom-forming fungus | Cells, grouped into organs for specific functions (e.g. reproduction) | Yes | Cell specialisation, communication[22] |

| Permanent sexual partnership | Anglerfish | Male and female permanently fastened together | Yes | Male provides male gametes; female provides all other functions[18] |

| Mutualism | Lichen | Organisms of different species | Yes | Fungus provides structure, absorbs water and minerals; alga photosynthesises[18] |

| Joined colony | Siphonophore | Zooids joined together | Yes | Organism specialisation; inter-organism signalling[8] |

| Superorganism | Ant colony | Individuals living together | Yes | Organism specialisation (many ants do not reproduce); inter-organism signalling[23] |

Samuel Díaz‐Muñoz and colleagues (2016) accept Queller and Strassmann's view that organismality can be measured wholly by degrees of cooperation and of conflict. They state that this situates organisms in evolutionary time, so that organismality is context dependent. They suggest that highly integrated life forms, which are not context dependent, may evolve through context-dependent stages towards complete unification.[24]

Boundary cases

[edit]Viruses

[edit]

Viruses are not typically considered to be organisms, because they are incapable of autonomous reproduction, growth, metabolism, or homeostasis. Although viruses have a few enzymes and molecules like those in living organisms, they have no metabolism of their own; they cannot synthesize the organic compounds from which they are formed. In this sense, they are similar to inanimate matter.[7] Viruses have their own genes, and they evolve. Thus, an argument that viruses should be classed as living organisms is their ability to undergo evolution and replicate through self-assembly. However, some scientists argue that viruses neither evolve nor self-reproduce. Instead, viruses are evolved by their host cells, meaning that there was co-evolution of viruses and host cells. If host cells did not exist, viral evolution would be impossible. As for reproduction, viruses rely on hosts' machinery to replicate. The discovery of viruses with genes coding for energy metabolism and protein synthesis fuelled the debate about whether viruses are living organisms, but the genes have a cellular origin. Most likely, they were acquired through horizontal gene transfer from viral hosts.[7]

| Capability | Cellular organism | Virus |

|---|---|---|

| Metabolism | Yes | No, rely entirely on host cell |

| Growth | Yes | No, just self-assembly |

| Reproduction | Yes | No, rely entirely on host cell |

| Store genetic information about themselves | DNA | DNA or RNA |

| Able to evolve | Yes: mutation, recombination, natural selection | Yes: high mutation rate, natural selection |

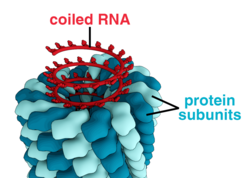

Evolutionary emergence of organisms

[edit]The RNA world is a hypothetical stage in the evolutionary history of life on Earth during which self-replicating RNA molecules reproduced before the evolution of DNA and proteins.[25] According to this hypothesis "organisms" emerged when RNA chains began to self-replicate, initiating the three mechanisms of Darwinian selection: heritability, variation of type and differential reproductive output. The fitness of an RNA replicator (its per capita rate of increase) would presumably have been a function of its intrinsic adaptive capacities, determined by its nucleotide sequence, and the availability of external resources.[26][27] The three primary adaptive capacities of these early "organisms" may have been: (1) replication with moderate fidelity, giving rise to both heritability while allowing variation of type, (2) resistance to decay, and (3) acquisition of and processing of resources[26][27] The capacities of these "organisms" would have functioned by means of the folded configurations of the RNA replicators resulting from their nucleotide sequences.

Organism-like colonies

[edit]

The philosopher Jack A. Wilson examines some boundary cases to demonstrate that the concept of organism is not sharply defined.[8] In his view, sponges, lichens, siphonophores, slime moulds, and eusocial colonies such as those of ants or naked molerats, all lie in the boundary zone between being definite colonies and definite organisms (or superorganisms).[8]

| Function | Colonial siphonophore | Jellyfish |

|---|---|---|

| Buoyancy | Top of colony is gas-filled | Jelly |

| Propulsion | Nectophores co-ordinate to pump water | Body pulsates to pump water |

| Feeding | Palpons and gastrozooids ingest prey, feed other zooids | Tentacles trap prey, pass it to mouth |

| Functional structure | Single functional individual | Single functional individual |

| Composition | Many zooids, possibly individuals | Many cells |

Synthetic organisms

[edit]

Scientists and bio-engineers are experimenting with different types of synthetic organism, from chimaeras composed of cells from two or more species, cyborgs including electromechanical limbs, hybrots containing both electronic and biological elements, and other combinations of systems that have variously evolved and been designed.[28]

An evolved organism takes its form by the partially understood mechanisms of evolutionary developmental biology, in which the genome directs an elaborated series of interactions to produce successively more elaborate structures. The existence of chimaeras and hybrids demonstrates that these mechanisms are "intelligently" robust in the face of radically altered circumstances at all levels from molecular to organismal.[28]

Synthetic organisms already take diverse forms, and their diversity will increase. What they all have in common is a teleonomic or goal-seeking behaviour that enables them to correct errors of many kinds so as to achieve whatever result they are designed for. Such behaviour is reminiscent of intelligent action by organisms; intelligence is seen as an embodied form of cognition.[28]

References

[edit]- ^ Mosby's Dictionary of Medicine, Nursing and Health Professions (10th ed.). St. Louis, Missouri: Elsevier. 2017. p. 1281. ISBN 978-0-3232-2205-1.

- ^ ὄργανον. Liddell, Henry George; Scott, Robert; A Greek–English Lexicon at the Perseus Project

- ^ a b c "organism (n.)". Online Etymology Dictionary. Retrieved 11 April 2024.

- ^ Kant, Immanuel (1790). Critique of Judgment. Lagarde und Friederich. §65 5:374.

- ^ Huneman, Philippe (2017). "Kant's Concept of Organism Revisited: A Framework for a Possible Synthesis between Developmentalism and Adaptationism?". The Monist. 100 (3): 373–390. doi:10.1093/monist/onx016. JSTOR 26370801.

- ^ a b Rosen, Robert (September 1958). "A relational theory of biological systems". The Bulletin of Mathematical Biophysics. 20 (3): 245–260. doi:10.1007/BF02478302. ISSN 0007-4985.

- ^ a b c d e Moreira, D.; López-García, P.N. (April 2009). "Ten reasons to exclude viruses from the tree of life". Nature Reviews Microbiology. 7 (4): 306–311. doi:10.1038/nrmicro2108. PMID 19270719. S2CID 3907750.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Wilson, Jack A. (2000). "Ontological butchery: organism concepts and biological generalizations". Philosophy of Science. 67: 301–311. doi:10.1086/392827. JSTOR 188676. S2CID 84168536.

- ^ Santelices, Bernabé (April 1999). "How many kinds of individual are there?". Trends in Ecology & Evolution. 14 (4): 152–155. doi:10.1016/S0169-5347(98)01519-5. PMID 10322523.

- ^ Pradeu, T. (2010). "What is an organism? An immunological answer". History and Philosophy of the Life Sciences. 32 (2–3): 247–267. PMID 21162370.

- ^ Bailly, Francis; Longo, Giuseppe (2009). "Biological Organization and Anti-entropy". Journal of Biological Systems. 17 (1): 63–96. doi:10.1142/S0218339009002715. ISSN 0218-3390.

- ^ Piast, Radosław W. (June 2019). "Shannon's information, Bernal's biopoiesis and Bernoulli distribution as pillars for building a definition of life". Journal of Theoretical Biology. 470: 101–107. Bibcode:2019JThBi.470..101P. doi:10.1016/j.jtbi.2019.03.009. PMID 30876803. S2CID 80625250.

- ^ Bateson, Patrick (February 2005). "The return of the whole organism". Journal of Biosciences. 30 (1): 31–39. doi:10.1007/BF02705148. PMID 15824439. S2CID 26656790.

- ^ Clarke, E. (2010). "The problem of biological individuality". Biological Theory. 5 (4): 312–325. doi:10.1162/BIOT_a_00068. S2CID 28501709.

- ^ Pepper, J.W.; Herron, M.D. (November 2008). "Does biology need an organism concept?". Biological Reviews of the Cambridge Philosophical Society. 83 (4): 621–627. doi:10.1111/j.1469-185X.2008.00057.x. PMID 18947335. S2CID 4942890.

- ^ Wilson, R. (2007). "The biological notion of individual". Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy.

- ^ a b Folse, H.J., III; Roughgarden, J. (December 2010). "What is an individual organism? A multilevel selection perspective". The Quarterly Review of Biology. 85 (4): 447–472. doi:10.1086/656905. PMID 21243964. S2CID 19816447.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b c d e f g h Queller, David C.; Strassmann, Joan E. (November 2009). "Beyond society: the evolution of organismality". Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London. Series B, Biological Sciences. 364 (1533): 3143–3155. doi:10.1098/rstb.2009.0095. PMC 2781869. PMID 19805423.

- ^ Gardner, A.; Grafen, A. (April 2009). "Capturing the superorganism: a formal theory of group adaptation". Journal of Evolutionary Biology. 22 (4): 659–671. doi:10.1111/j.1420-9101.2008.01681.x. PMID 19210588. S2CID 8413751.

- ^ Santelices, B. (April 1999). "How many kinds of individual are there?". Trends in Ecology & Evolution. 14 (4): 152–155. doi:10.1016/s0169-5347(98)01519-5. PMID 10322523.

- ^ a b Lücking, Robert; Leavitt, Steven D.; Hawksworth, David L. (2021). "Species in lichen-forming fungi: balancing between conceptual and practical considerations, and between phenotype and phylogenomics". Fungal Diversity. 109 (1): 99–154. doi:10.1007/s13225-021-00477-7.

- ^ a b c d Hine, R.S. (2008). A Dictionary of Biology (6th ed.). Oxford: Oxford University Press. p. 461. ISBN 978-0-19-920462-5.

- ^ a b Kelly, Kevin (1994). Out of control: the new biology of machines, social systems and the economic world. Boston: Addison-Wesley. pp. 98. ISBN 978-0-201-48340-6.

- ^ Díaz-Muñoz, Samuel L.; Boddy, Amy M.; Dantas, Gautam; Waters, Christopher M.; Bronstein, Judith L. (2016). "Contextual organismality: Beyond pattern to process in the emergence of organisms". Evolution. 70 (12): 2669–2677. doi:10.1111/evo.13078. ISSN 0014-3820. PMC 5132100. PMID 27704542.

- ^ Johnson, Mark (9 March 2024). "'Monumental' experiment suggests how life on Earth may have started". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on 9 March 2024. Retrieved 10 March 2024

- ^ a b Bernstein, H., Byerly, H. C., Hopf, F. A., Michod, R. A., & Vemulapalli, G. K. (1983). The Darwinian Dynamic. The Quarterly Review of Biology, 58(2), 185–207. http://www.jstor.org/stable/2828805

- ^ a b Michod, R.E. Darwinian Dynamics: Evolutionary transitions in fitness and individuality. Copyright 1999 Princeton University Press, Princeton, New Jersey ISBN 0-691-02699-8

- ^ a b c Clawson, Wesley P.; Levin, Michael (1 January 2023). "Endless forms most beautiful 2.0: teleonomy and the bioengineering of chimaeric and synthetic organisms". Biological Journal of the Linnean Society. 138 (1): 141. doi:10.1093/biolinnean/blac116. ISSN 0024-4066.

External links

[edit]- "The Tree of Life". Tree of Life Web Project.

- "Indexing the world's known species". Species 2000. Archived from the original on 3 March 2016. Retrieved 13 September 2004.