Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Logic

View on Wikipedia

Logic is the study of correct reasoning. It includes both formal and informal logic. Formal logic is the study of deductively valid inferences or logical truths. It examines how conclusions follow from premises based on the structure of arguments alone, independent of their topic and content. Informal logic is associated with informal fallacies, critical thinking, and argumentation theory. Informal logic examines arguments expressed in natural language whereas formal logic uses formal language. When used as a countable noun, the term "a logic" refers to a specific logical formal system that articulates a proof system. Logic plays a central role in many fields, such as philosophy, mathematics, computer science, and linguistics.

Logic studies arguments, which consist of a set of premises that leads to a conclusion. An example is the argument from the premises "it's Sunday" and "if it's Sunday then I don't have to work" leading to the conclusion "I don't have to work."[1] Premises and conclusions express propositions or claims that can be true or false. An important feature of propositions is their internal structure. For example, complex propositions are made up of simpler propositions linked by logical vocabulary like (and) or (if...then). Simple propositions also have parts, like "Sunday" or "work" in the example. The truth of a proposition usually depends on the meanings of all of its parts. However, this is not the case for logically true propositions. They are true only because of their logical structure independent of the specific meanings of the individual parts.

Arguments can be either correct or incorrect. An argument is correct if its premises support its conclusion. Deductive arguments have the strongest form of support: if their premises are true then their conclusion must also be true. This is not the case for ampliative arguments, which arrive at genuinely new information not found in the premises. Many arguments in everyday discourse and the sciences are ampliative arguments. They are divided into inductive and abductive arguments. Inductive arguments are statistical generalizations, such as inferring that all ravens are black based on many individual observations of black ravens.[2] Abductive arguments are inferences to the best explanation, for example, when a doctor concludes that a patient has a certain disease which explains the symptoms they suffer.[3] Arguments that fall short of the standards of correct reasoning often embody fallacies. Systems of logic are theoretical frameworks for assessing the correctness of arguments.

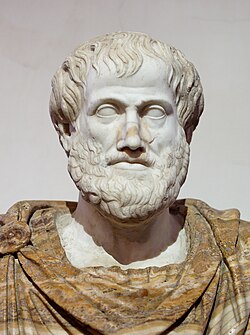

Logic has been studied since antiquity. Early approaches include Aristotelian logic, Stoic logic, Nyaya, and Mohism. Aristotelian logic focuses on reasoning in the form of syllogisms. It was considered the main system of logic in the Western world until it was replaced by modern formal logic, which has its roots in the work of late 19th-century mathematicians such as Gottlob Frege. Today, the most commonly used system is classical logic. It consists of propositional logic and first-order logic. Propositional logic only considers logical relations between full propositions. First-order logic also takes the internal parts of propositions into account, like predicates and quantifiers. Extended logics accept the basic intuitions behind classical logic and apply it to other fields, such as metaphysics, ethics, and epistemology. Deviant logics, on the other hand, reject certain classical intuitions and provide alternative explanations of the basic laws of logic.

Definition

[edit]The word "logic" originates from the Greek word logos, which has a variety of translations, such as reason, discourse, or language.[4] Logic is traditionally defined as the study of the laws of thought or correct reasoning,[5] and is usually understood in terms of inferences or arguments. Reasoning is the activity of drawing inferences. Arguments are the outward expression of inferences.[6] An argument is a set of premises together with a conclusion. Logic is interested in whether arguments are correct, i.e. whether their premises support the conclusion.[7] These general characterizations apply to logic in the widest sense, i.e., to both formal and informal logic since they are both concerned with assessing the correctness of arguments.[8] Formal logic is the traditionally dominant field, and some logicians restrict logic to formal logic.[9]

Formal logic

[edit]Formal logic (also known as symbolic logic) is widely used in mathematical logic. It uses a formal approach to study reasoning: it replaces concrete expressions with abstract symbols to examine the logical form of arguments independent of their concrete content. In this sense, it is topic-neutral since it is only concerned with the abstract structure of arguments and not with their concrete content.[10]

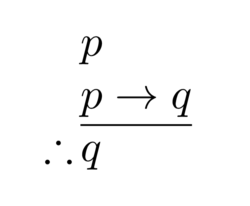

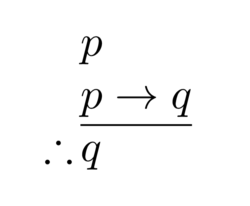

Formal logic is interested in deductively valid arguments, for which the truth of their premises ensures the truth of their conclusion. This means that it is impossible for the premises to be true and the conclusion to be false.[11] For valid arguments, the logical structure that leads from the premises to the conclusion follows a pattern called a rule of inference.[12] For example, modus ponens is a rule of inference according to which all arguments of the form "(1) p, (2) if p then q, (3) therefore q" are valid, independent of what the terms p and q stand for.[13] In this sense, formal logic can be defined as the science of valid inferences. An alternative definition sees logic as the study of logical truths.[14] A proposition is logically true if its truth depends only on the logical vocabulary used in it. This means that it is true in all possible worlds and under all interpretations of its non-logical terms, like the claim "either it is raining, or it is not".[15] These two definitions of formal logic are not identical, but they are closely related. For example, if the inference from p to q is deductively valid then the claim "if p then q" is a logical truth.[16]

Formal logic uses formal languages to express, analyze, and clarify arguments.[17] They normally have a very limited vocabulary and exact syntactic rules. These rules specify how their symbols can be combined to construct sentences, so-called well-formed formulas.[18] This simplicity and exactness of formal logic make it capable of formulating precise rules of inference. They determine whether a given argument is valid.[19] Because of the reliance on formal language, natural language arguments cannot be studied directly. Instead, they need to be translated into formal language before their validity can be assessed.[20]

The term "logic" can also be used in a slightly different sense as a countable noun. In this sense, a logic is a logical formal system. Distinct logics differ from each other concerning the rules of inference they accept as valid and the formal languages used to express them.[21] Starting in the late 19th century, many new formal systems have been proposed. There are disagreements about what makes a formal system a logic.[22] For example, it has been suggested that only logically complete systems, like first-order logic, qualify as logics. For such reasons, some theorists deny that higher-order logics are logics in the strict sense.[23]

Informal logic

[edit]When understood in a wide sense, logic encompasses both formal and informal logic.[24] Informal logic uses non-formal criteria and standards to analyze and assess the correctness of arguments. Its main focus is on everyday discourse.[25] Its development was prompted by difficulties in applying the insights of formal logic to natural language arguments.[26] In this regard, it considers problems that formal logic on its own is unable to address.[27] Both provide criteria for assessing the correctness of arguments and distinguishing them from fallacies.[28]

Many characterizations of informal logic have been suggested but there is no general agreement on its precise definition.[29] The most literal approach sees the terms "formal" and "informal" as applying to the language used to express arguments. On this view, informal logic studies arguments that are in informal or natural language.[30] Formal logic can only examine them indirectly by translating them first into a formal language while informal logic investigates them in their original form.[31] On this view, the argument "Birds fly. Tweety is a bird. Therefore, Tweety flies." belongs to natural language and is examined by informal logic. But the formal translation "(1) ; (2) ; (3) " is studied by formal logic.[32] The study of natural language arguments comes with various difficulties. For example, natural language expressions are often ambiguous, vague, and context-dependent.[33] Another approach defines informal logic in a wide sense as the normative study of the standards, criteria, and procedures of argumentation. In this sense, it includes questions about the role of rationality, critical thinking, and the psychology of argumentation.[34]

Another characterization identifies informal logic with the study of non-deductive arguments. In this way, it contrasts with deductive reasoning examined by formal logic.[35] Non-deductive arguments make their conclusion probable but do not ensure that it is true. An example is the inductive argument from the empirical observation that "all ravens I have seen so far are black" to the conclusion "all ravens are black".[36]

A further approach is to define informal logic as the study of informal fallacies.[37] Informal fallacies are incorrect arguments in which errors are present in the content and the context of the argument.[38] A false dilemma, for example, involves an error of content by excluding viable options. This is the case in the fallacy "you are either with us or against us; you are not with us; therefore, you are against us".[39] Some theorists state that formal logic studies the general form of arguments while informal logic studies particular instances of arguments. Another approach is to hold that formal logic only considers the role of logical constants for correct inferences while informal logic also takes the meaning of substantive concepts into account. Further approaches focus on the discussion of logical topics with or without formal devices and on the role of epistemology for the assessment of arguments.[40]

Basic concepts

[edit]Premises, conclusions, and truth

[edit]Premises and conclusions

[edit]Premises and conclusions are the basic parts of inferences or arguments and therefore play a central role in logic. In the case of a valid inference or a correct argument, the conclusion follows from the premises, or in other words, the premises support the conclusion.[41] For instance, the premises "Mars is red" and "Mars is a planet" support the conclusion "Mars is a red planet". For most types of logic, it is accepted that premises and conclusions have to be truth-bearers.[41][a] This means that they have a truth value: they are either true or false. Contemporary philosophy generally sees them either as propositions or as sentences.[43] Propositions are the denotations of sentences and are usually seen as abstract objects.[44] For example, the English sentence "the tree is green" is different from the German sentence "der Baum ist grün" but both express the same proposition.[45]

Propositional theories of premises and conclusions are often criticized because they rely on abstract objects. For instance, philosophical naturalists usually reject the existence of abstract objects. Other arguments concern the challenges involved in specifying the identity criteria of propositions.[43] These objections are avoided by seeing premises and conclusions not as propositions but as sentences, i.e. as concrete linguistic objects like the symbols displayed on a page of a book. But this approach comes with new problems of its own: sentences are often context-dependent and ambiguous, meaning an argument's validity would not only depend on its parts but also on its context and on how it is interpreted.[46] Another approach is to understand premises and conclusions in psychological terms as thoughts or judgments. This position is known as psychologism. It was discussed at length around the turn of the 20th century but it is not widely accepted today.[47]

Internal structure

[edit]Premises and conclusions have an internal structure. As propositions or sentences, they can be either simple or complex.[48] A complex proposition has other propositions as its constituents, which are linked to each other through propositional connectives like "and" or "if...then". Simple propositions, on the other hand, do not have propositional parts. But they can also be conceived as having an internal structure: they are made up of subpropositional parts, like singular terms and predicates.[49][48] For example, the simple proposition "Mars is red" can be formed by applying the predicate "red" to the singular term "Mars". In contrast, the complex proposition "Mars is red and Venus is white" is made up of two simple propositions connected by the propositional connective "and".[49]

Whether a proposition is true depends, at least in part, on its constituents. For complex propositions formed using truth-functional propositional connectives, their truth only depends on the truth values of their parts.[49][50] But this relation is more complicated in the case of simple propositions and their subpropositional parts. These subpropositional parts have meanings of their own, like referring to objects or classes of objects.[51] Whether the simple proposition they form is true depends on their relation to reality, i.e. what the objects they refer to are like. This topic is studied by theories of reference.[52]

Logical truth

[edit]Some complex propositions are true independently of the substantive meanings of their parts.[53] In classical logic, for example, the complex proposition "either Mars is red or Mars is not red" is true independent of whether its parts, like the simple proposition "Mars is red", are true or false. In such cases, the truth is called a logical truth: a proposition is logically true if its truth depends only on the logical vocabulary used in it.[54] This means that it is true under all interpretations of its non-logical terms. In some modal logics, this means that the proposition is true in all possible worlds.[55] Some theorists define logic as the study of logical truths.[16]

Truth tables

[edit]Truth tables can be used to show how logical connectives work or how the truth values of complex propositions depends on their parts. They have a column for each input variable. Each row corresponds to one possible combination of the truth values these variables can take; for truth tables presented in the English literature, the symbols "T" and "F" or "1" and "0" are commonly used as abbreviations for the truth values "true" and "false".[56] The first columns present all the possible truth-value combinations for the input variables. Entries in the other columns present the truth values of the corresponding expressions as determined by the input values. For example, the expression "" uses the logical connective (and). It could be used to express a sentence like "yesterday was Sunday and the weather was good". It is only true if both of its input variables, ("yesterday was Sunday") and ("the weather was good"), are true. In all other cases, the expression as a whole is false. Other important logical connectives are (not), (or), (if...then), and (Sheffer stroke).[57] Given the conditional proposition , one can form truth tables of its converse , its inverse (), and its contrapositive (). Truth tables can also be defined for more complex expressions that use several propositional connectives.[58]

| p | q | p ∧ q | p ∨ q | p → q | ¬p → ¬q | p q |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| T | T | T | T | T | T | F |

| T | F | F | T | F | T | T |

| F | T | F | T | T | F | T |

| F | F | F | F | T | T | T |

Arguments and inferences

[edit]Logic is commonly defined in terms of arguments or inferences as the study of their correctness.[59] An argument is a set of premises together with a conclusion.[60] An inference is the process of reasoning from these premises to the conclusion.[43] But these terms are often used interchangeably in logic. Arguments are correct or incorrect depending on whether their premises support their conclusion. Premises and conclusions, on the other hand, are true or false depending on whether they are in accord with reality. In formal logic, a sound argument is an argument that is both correct and has only true premises.[61] Sometimes a distinction is made between simple and complex arguments. A complex argument is made up of a chain of simple arguments. This means that the conclusion of one argument acts as a premise of later arguments. For a complex argument to be successful, each link of the chain has to be successful.[43]

Arguments and inferences are either correct or incorrect. If they are correct then their premises support their conclusion. In the incorrect case, this support is missing. It can take different forms corresponding to the different types of reasoning.[62] The strongest form of support corresponds to deductive reasoning. But even arguments that are not deductively valid may still be good arguments because their premises offer non-deductive support to their conclusions. For such cases, the term ampliative or inductive reasoning is used.[63] Deductive arguments are associated with formal logic in contrast to the relation between ampliative arguments and informal logic.[64]

Deductive

[edit]A deductively valid argument is one whose premises guarantee the truth of its conclusion.[11] For instance, the argument "(1) all frogs are amphibians; (2) no cats are amphibians; (3) therefore no cats are frogs" is deductively valid. For deductive validity, it does not matter whether the premises or the conclusion are actually true. So the argument "(1) all frogs are mammals; (2) no cats are mammals; (3) therefore no cats are frogs" is also valid because the conclusion follows necessarily from the premises.[65]

According to an influential view by Alfred Tarski, deductive arguments have three essential features: (1) they are formal, i.e. they depend only on the form of the premises and the conclusion; (2) they are a priori, i.e. no sense experience is needed to determine whether they obtain; (3) they are modal, i.e. that they hold by logical necessity for the given propositions, independent of any other circumstances.[66]

Because of the first feature, the focus on formality, deductive inference is usually identified with rules of inference.[67] Rules of inference specify the form of the premises and the conclusion: how they have to be structured for the inference to be valid. Arguments that do not follow any rule of inference are deductively invalid.[68] The modus ponens is a prominent rule of inference. It has the form "p; if p, then q; therefore q".[69] Knowing that it has just rained () and that after rain the streets are wet (), one can use modus ponens to deduce that the streets are wet ().[70]

The third feature can be expressed by stating that deductively valid inferences are truth-preserving: it is impossible for the premises to be true and the conclusion to be false.[71] Because of this feature, it is often asserted that deductive inferences are uninformative since the conclusion cannot arrive at new information not already present in the premises.[72] But this point is not always accepted since it would mean, for example, that most of mathematics is uninformative. A different characterization distinguishes between surface and depth information. The surface information of a sentence is the information it presents explicitly. Depth information is the totality of the information contained in the sentence, both explicitly and implicitly. According to this view, deductive inferences are uninformative on the depth level. But they can be highly informative on the surface level by making implicit information explicit. This happens, for example, in mathematical proofs.[73]

Ampliative

[edit]Ampliative arguments are arguments whose conclusions contain additional information not found in their premises. In this regard, they are more interesting since they contain information on the depth level and the thinker may learn something genuinely new. But this feature comes with a certain cost: the premises support the conclusion in the sense that they make its truth more likely but they do not ensure its truth.[74] This means that the conclusion of an ampliative argument may be false even though all its premises are true. This characteristic is closely related to non-monotonicity and defeasibility: it may be necessary to retract an earlier conclusion upon receiving new information or in light of new inferences drawn.[75] Ampliative reasoning plays a central role in many arguments found in everyday discourse and the sciences. Ampliative arguments are not automatically incorrect. Instead, they just follow different standards of correctness. The support they provide for their conclusion usually comes in degrees. This means that strong ampliative arguments make their conclusion very likely while weak ones are less certain. As a consequence, the line between correct and incorrect arguments is blurry in some cases, such as when the premises offer weak but non-negligible support. This contrasts with deductive arguments, which are either valid or invalid with nothing in-between.[76]

The terminology used to categorize ampliative arguments is inconsistent. Some authors, like James Hawthorne, use the term "induction" to cover all forms of non-deductive arguments.[77] But in a more narrow sense, induction is only one type of ampliative argument alongside abductive arguments.[78] Some philosophers, like Leo Groarke, also allow conductive arguments[b] as another type.[79] In this narrow sense, induction is often defined as a form of statistical generalization.[80] In this case, the premises of an inductive argument are many individual observations that all show a certain pattern. The conclusion then is a general law that this pattern always obtains.[81] In this sense, one may infer that "all elephants are gray" based on one's past observations of the color of elephants.[78] A closely related form of inductive inference has as its conclusion not a general law but one more specific instance, as when it is inferred that an elephant one has not seen yet is also gray.[81] Some theorists, like Igor Douven, stipulate that inductive inferences rest only on statistical considerations. This way, they can be distinguished from abductive inference.[78]

Abductive inference may or may not take statistical observations into consideration. In either case, the premises offer support for the conclusion because the conclusion is the best explanation of why the premises are true.[82] In this sense, abduction is also called the inference to the best explanation.[83] For example, given the premise that there is a plate with breadcrumbs in the kitchen in the early morning, one may infer the conclusion that one's house-mate had a midnight snack and was too tired to clean the table. This conclusion is justified because it is the best explanation of the current state of the kitchen.[78] For abduction, it is not sufficient that the conclusion explains the premises. For example, the conclusion that a burglar broke into the house last night, got hungry on the job, and had a midnight snack, would also explain the state of the kitchen. But this conclusion is not justified because it is not the best or most likely explanation.[82][83]

Fallacies

[edit]Not all arguments live up to the standards of correct reasoning. When they do not, they are usually referred to as fallacies. Their central aspect is not that their conclusion is false but that there is some flaw with the reasoning leading to this conclusion.[84] So the argument "it is sunny today; therefore spiders have eight legs" is fallacious even though the conclusion is true. Some theorists, like John Stuart Mill, give a more restrictive definition of fallacies by additionally requiring that they appear to be correct.[85] This way, genuine fallacies can be distinguished from mere mistakes of reasoning due to carelessness. This explains why people tend to commit fallacies: because they have an alluring element that seduces people into committing and accepting them.[86] However, this reference to appearances is controversial because it belongs to the field of psychology, not logic, and because appearances may be different for different people.[87]

Fallacies are usually divided into formal and informal fallacies.[38] For formal fallacies, the source of the error is found in the form of the argument. For example, denying the antecedent is one type of formal fallacy, as in "if Othello is a bachelor, then he is male; Othello is not a bachelor; therefore Othello is not male".[88] But most fallacies fall into the category of informal fallacies, of which a great variety is discussed in the academic literature. The source of their error is usually found in the content or the context of the argument.[89] Informal fallacies are sometimes categorized as fallacies of ambiguity, fallacies of presumption, or fallacies of relevance. For fallacies of ambiguity, the ambiguity and vagueness of natural language are responsible for their flaw, as in "feathers are light; what is light cannot be dark; therefore feathers cannot be dark".[90] Fallacies of presumption have a wrong or unjustified premise but may be valid otherwise.[91] In the case of fallacies of relevance, the premises do not support the conclusion because they are not relevant to it.[92]

Definitory and strategic rules

[edit]The main focus of most logicians is to study the criteria according to which an argument is correct or incorrect. A fallacy is committed if these criteria are violated. In the case of formal logic, they are known as rules of inference.[93] They are definitory rules, which determine whether an inference is correct or which inferences are allowed. Definitory rules contrast with strategic rules. Strategic rules specify which inferential moves are necessary to reach a given conclusion based on a set of premises. This distinction does not just apply to logic but also to games. In chess, for example, the definitory rules dictate that bishops may only move diagonally. The strategic rules, on the other hand, describe how the allowed moves may be used to win a game, for instance, by controlling the center and by defending one's king.[94] It has been argued that logicians should give more emphasis to strategic rules since they are highly relevant for effective reasoning.[93]

Formal systems

[edit]A formal system of logic consists of a formal language together with a set of axioms and a proof system used to draw inferences from these axioms.[95] In logic, axioms are statements that are accepted without proof. They are used to justify other statements.[96] Some theorists also include a semantics that specifies how the expressions of the formal language relate to real objects.[97] Starting in the late 19th century, many new formal systems have been proposed.[98]

A formal language consists of an alphabet and syntactic rules. The alphabet is the set of basic symbols used in expressions. The syntactic rules determine how these symbols may be arranged to result in well-formed formulas.[99] For instance, the syntactic rules of propositional logic determine that "" is a well-formed formula but "" is not since the logical conjunction requires terms on both sides.[100]

A proof system is a collection of rules to construct formal proofs. It is a tool to arrive at conclusions from a set of axioms. Rules in a proof system are defined in terms of the syntactic form of formulas independent of their specific content. For instance, the classical rule of conjunction introduction states that follows from the premises and . Such rules can be applied sequentially, giving a mechanical procedure for generating conclusions from premises. There are different types of proof systems including natural deduction and sequent calculi.[101]

A semantics is a system for mapping expressions of a formal language to their denotations. In many systems of logic, denotations are truth values. For instance, the semantics for classical propositional logic assigns the formula the denotation "true" whenever and are true. From the semantic point of view, a premise entails a conclusion if the conclusion is true whenever the premise is true.[102]

A system of logic is sound when its proof system cannot derive a conclusion from a set of premises unless it is semantically entailed by them. In other words, its proof system cannot lead to false conclusions, as defined by the semantics. A system is complete when its proof system can derive every conclusion that is semantically entailed by its premises. In other words, its proof system can lead to any true conclusion, as defined by the semantics. Thus, soundness and completeness together describe a system whose notions of validity and entailment line up perfectly.[103]

Systems of logic

[edit]Systems of logic are theoretical frameworks for assessing the correctness of reasoning and arguments. For over two thousand years, Aristotelian logic was treated as the canon of logic in the Western world,[104] but modern developments in this field have led to a vast proliferation of logical systems.[105] One prominent categorization divides modern formal logical systems into classical logic, extended logics, and deviant logics.[106]

Aristotelian

[edit]Aristotelian logic encompasses a great variety of topics. They include metaphysical theses about ontological categories and problems of scientific explanation. But in a more narrow sense, it is identical to term logic or syllogistics. A syllogism is a form of argument involving three propositions: two premises and a conclusion. Each proposition has three essential parts: a subject, a predicate, and a copula connecting the subject to the predicate.[107] For example, the proposition "Socrates is wise" is made up of the subject "Socrates", the predicate "wise", and the copula "is".[108] The subject and the predicate are the terms of the proposition. Aristotelian logic does not contain complex propositions made up of simple propositions. It differs in this aspect from propositional logic, in which any two propositions can be linked using a logical connective like "and" to form a new complex proposition.[109]

In Aristotelian logic, the subject can be universal, particular, indefinite, or singular. For example, the term "all humans" is a universal subject in the proposition "all humans are mortal". A similar proposition could be formed by replacing it with the particular term "some humans", the indefinite term "a human", or the singular term "Socrates".[110]

Aristotelian logic only includes predicates for simple properties of entities. But it lacks predicates corresponding to relations between entities.[111] The predicate can be linked to the subject in two ways: either by affirming it or by denying it.[112] For example, the proposition "Socrates is not a cat" involves the denial of the predicate "cat" to the subject "Socrates". Using combinations of subjects and predicates, a great variety of propositions and syllogisms can be formed. Syllogisms are characterized by the fact that the premises are linked to each other and to the conclusion by sharing one term in each case.[113] Thus, these three propositions contain three terms, referred to as major term, minor term, and middle term.[114] The central aspect of Aristotelian logic involves classifying all possible syllogisms into valid and invalid arguments according to how the propositions are formed.[112][115] For example, the syllogism "all men are mortal; Socrates is a man; therefore Socrates is mortal" is valid. The syllogism "all cats are mortal; Socrates is mortal; therefore Socrates is a cat", on the other hand, is invalid.[116]

Classical

[edit]Classical logic is distinct from traditional or Aristotelian logic. It encompasses propositional logic and first-order logic. It is "classical" in the sense that it is based on basic logical intuitions shared by most logicians.[117] These intuitions include the law of excluded middle, the double negation elimination, the principle of explosion, and the bivalence of truth.[118] It was originally developed to analyze mathematical arguments and was only later applied to other fields as well. Because of this focus on mathematics, it does not include logical vocabulary relevant to many other topics of philosophical importance. Examples of concepts it overlooks are the contrast between necessity and possibility and the problem of ethical obligation and permission. Similarly, it does not address the relations between past, present, and future.[119] Such issues are addressed by extended logics. They build on the basic intuitions of classical logic and expand it by introducing new logical vocabulary. This way, the exact logical approach is applied to fields like ethics or epistemology that lie beyond the scope of mathematics.[120]

Propositional logic

[edit]Propositional logic comprises formal systems in which formulae are built from atomic propositions using logical connectives. For instance, propositional logic represents the conjunction of two atomic propositions and as the complex formula . Unlike predicate logic where terms and predicates are the smallest units, propositional logic takes full propositions with truth values as its most basic component.[121] Thus, propositional logics can only represent logical relationships that arise from the way complex propositions are built from simpler ones. But it cannot represent inferences that result from the inner structure of a proposition.[122]

First-order logic

[edit]

First-order logic includes the same propositional connectives as propositional logic but differs from it because it articulates the internal structure of propositions. This happens through devices such as singular terms, which refer to particular objects, predicates, which refer to properties and relations, and quantifiers, which treat notions like "some" and "all".[123] For example, to express the proposition "this raven is black", one may use the predicate for the property "black" and the singular term referring to the raven to form the expression . To express that some objects are black, the existential quantifier is combined with the variable to form the proposition . First-order logic contains various rules of inference that determine how expressions articulated this way can form valid arguments, for example, that one may infer from .[124]

Extended

[edit]Extended logics are logical systems that accept the basic principles of classical logic. They introduce additional symbols and principles to apply it to fields like metaphysics, ethics, and epistemology.[125]

Modal logic

[edit]Modal logic is an extension of classical logic. In its original form, sometimes called "alethic modal logic", it introduces two new symbols: expresses that something is possible while expresses that something is necessary.[126] For example, if the formula stands for the sentence "Socrates is a banker" then the formula articulates the sentence "It is possible that Socrates is a banker".[127] To include these symbols in the logical formalism, modal logic introduces new rules of inference that govern what role they play in inferences. One rule of inference states that, if something is necessary, then it is also possible. This means that follows from . Another principle states that if a proposition is necessary then its negation is impossible and vice versa. This means that is equivalent to .[128]

Other forms of modal logic introduce similar symbols but associate different meanings with them to apply modal logic to other fields. For example, deontic logic concerns the field of ethics and introduces symbols to express the ideas of obligation and permission, i.e. to describe whether an agent has to perform a certain action or is allowed to perform it.[129] The modal operators in temporal modal logic articulate temporal relations. They can be used to express, for example, that something happened at one time or that something is happening all the time.[129] In epistemology, epistemic modal logic is used to represent the ideas of knowing something in contrast to merely believing it to be the case.[130]

Higher order logic

[edit]Higher-order logics extend classical logic not by using modal operators but by introducing new forms of quantification.[131] Quantifiers correspond to terms like "all" or "some". In classical first-order logic, quantifiers are only applied to individuals. The formula "" (some apples are sweet) is an example of the existential quantifier "" applied to the individual variable "". In higher-order logics, quantification is also allowed over predicates. This increases its expressive power. For example, to express the idea that Mary and John share some qualities, one could use the formula "". In this case, the existential quantifier is applied to the predicate variable "".[132] The added expressive power is especially useful for mathematics since it allows for more succinct formulations of mathematical theories.[43] But it has drawbacks in regard to its meta-logical properties and ontological implications, which is why first-order logic is still more commonly used.[133]

Deviant

[edit]Deviant logics are logical systems that reject some of the basic intuitions of classical logic. Because of this, they are usually seen not as its supplements but as its rivals. Deviant logical systems differ from each other either because they reject different classical intuitions or because they propose different alternatives to the same issue.[134]

Intuitionistic logic is a restricted version of classical logic.[135] It uses the same symbols but excludes some rules of inference. For example, according to the law of double negation elimination, if a sentence is not not true, then it is true. This means that follows from . This is a valid rule of inference in classical logic but it is invalid in intuitionistic logic. Another classical principle not part of intuitionistic logic is the law of excluded middle. It states that for every sentence, either it or its negation is true. This means that every proposition of the form is true.[135] These deviations from classical logic are based on the idea that truth is established by verification using a proof. Intuitionistic logic is especially prominent in the field of constructive mathematics, which emphasizes the need to find or construct a specific example to prove its existence.[136]

Multi-valued logics depart from classicality by rejecting the principle of bivalence, which requires all propositions to be either true or false. For instance, Jan Łukasiewicz and Stephen Cole Kleene both proposed ternary logics which have a third truth value representing that a statement's truth value is indeterminate.[137] These logics have been applied in the field of linguistics. Fuzzy logics are multivalued logics that have an infinite number of "degrees of truth", represented by a real number between 0 and 1.[138]

Paraconsistent logics are logical systems that can deal with contradictions. They are formulated to avoid the principle of explosion: for them, it is not the case that anything follows from a contradiction.[139] They are often motivated by dialetheism, the view that contradictions are real or that reality itself is contradictory. Graham Priest is an influential contemporary proponent of this position and similar views have been ascribed to Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel.[140]

Informal

[edit]Informal logic is usually carried out in a less systematic way. It often focuses on more specific issues, like investigating a particular type of fallacy or studying a certain aspect of argumentation. Nonetheless, some frameworks of informal logic have also been presented that try to provide a systematic characterization of the correctness of arguments.[141]

The pragmatic or dialogical approach to informal logic sees arguments as speech acts and not merely as a set of premises together with a conclusion.[142] As speech acts, they occur in a certain context, like a dialogue, which affects the standards of right and wrong arguments.[143] A prominent version by Douglas N. Walton understands a dialogue as a game between two players. The initial position of each player is characterized by the propositions to which they are committed and the conclusion they intend to prove. Dialogues are games of persuasion: each player has the goal of convincing the opponent of their own conclusion.[144] This is achieved by making arguments: arguments are the moves of the game.[145] They affect to which propositions the players are committed. A winning move is a successful argument that takes the opponent's commitments as premises and shows how one's own conclusion follows from them. This is usually not possible straight away. For this reason, it is normally necessary to formulate a sequence of arguments as intermediary steps, each of which brings the opponent a little closer to one's intended conclusion. Besides these positive arguments leading one closer to victory, there are also negative arguments preventing the opponent's victory by denying their conclusion.[144] Whether an argument is correct depends on whether it promotes the progress of the dialogue. Fallacies, on the other hand, are violations of the standards of proper argumentative rules.[146] These standards also depend on the type of dialogue. For example, the standards governing the scientific discourse differ from the standards in business negotiations.[147]

The epistemic approach to informal logic, on the other hand, focuses on the epistemic role of arguments.[148] It is based on the idea that arguments aim to increase our knowledge. They achieve this by linking justified beliefs to beliefs that are not yet justified.[149] Correct arguments succeed at expanding knowledge while fallacies are epistemic failures: they do not justify the belief in their conclusion.[150] For example, the fallacy of begging the question is a fallacy because it fails to provide independent justification for its conclusion, even though it is deductively valid.[151] In this sense, logical normativity consists in epistemic success or rationality.[149] The Bayesian approach is one example of an epistemic approach.[152] Central to Bayesianism is not just whether the agent believes something but the degree to which they believe it, the so-called credence. Degrees of belief are seen as subjective probabilities in the believed proposition, i.e. how certain the agent is that the proposition is true.[153] On this view, reasoning can be interpreted as a process of changing one's credences, often in reaction to new incoming information.[154] Correct reasoning and the arguments it is based on follow the laws of probability, for example, the principle of conditionalization. Bad or irrational reasoning, on the other hand, violates these laws.[155]

Areas of research

[edit]Logic is studied in various fields. In many cases, this is done by applying its formal method to specific topics outside its scope, like to ethics or computer science.[156] In other cases, logic itself is made the subject of research in another discipline. This can happen in diverse ways. For instance, it can involve investigating the philosophical assumptions linked to the basic concepts used by logicians. Other ways include interpreting and analyzing logic through mathematical structures as well as studying and comparing abstract properties of formal logical systems.[157]

Philosophy of logic and philosophical logic

[edit]Philosophy of logic is the philosophical discipline studying the scope and nature of logic.[59] It examines many presuppositions implicit in logic, like how to define its basic concepts or the metaphysical assumptions associated with them.[158] It is also concerned with how to classify logical systems and considers the ontological commitments they incur.[159] Philosophical logic is one of the areas within the philosophy of logic. It studies the application of logical methods to philosophical problems in fields like metaphysics, ethics, and epistemology.[160] This application usually happens in the form of extended or deviant logical systems.[161]

Metalogic

[edit]Metalogic is the field of inquiry studying the properties of formal logical systems. For example, when a new formal system is developed, metalogicians may study it to determine which formulas can be proven in it. They may also study whether an algorithm could be developed to find a proof for each formula and whether every provable formula in it is a tautology. Finally, they may compare it to other logical systems to understand its distinctive features. A key issue in metalogic concerns the relation between syntax and semantics. The syntactic rules of a formal system determine how to deduce conclusions from premises, i.e. how to formulate proofs. The semantics of a formal system governs which sentences are true and which ones are false. This determines the validity of arguments since, for valid arguments, it is impossible for the premises to be true and the conclusion to be false. The relation between syntax and semantics concerns issues like whether every valid argument is provable and whether every provable argument is valid. Metalogicians also study whether logical systems are complete, sound, and consistent. They are interested in whether the systems are decidable and what expressive power they have. Metalogicians usually rely heavily on abstract mathematical reasoning when examining and formulating metalogical proofs. This way, they aim to arrive at precise and general conclusions on these topics.[162]

Mathematical logic

[edit]

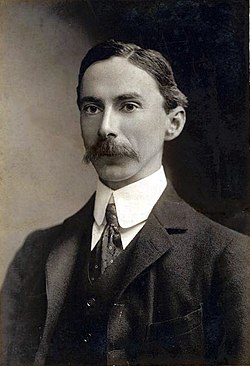

The term "mathematical logic" is sometimes used as a synonym of "formal logic". But in a more restricted sense, it refers to the study of logic within mathematics. Major subareas include model theory, proof theory, set theory, and computability theory.[164] Research in mathematical logic commonly addresses the mathematical properties of formal systems of logic. However, it can also include attempts to use logic to analyze mathematical reasoning or to establish logic-based foundations of mathematics.[165] The latter was a major concern in early 20th-century mathematical logic, which pursued the program of logicism pioneered by philosopher-logicians such as Gottlob Frege, Alfred North Whitehead, and Bertrand Russell. Mathematical theories were supposed to be logical tautologies, and their program was to show this by means of a reduction of mathematics to logic. Many attempts to realize this program failed, from the crippling of Frege's project in his Grundgesetze by Russell's paradox, to the defeat of Hilbert's program by Gödel's incompleteness theorems.[166]

Set theory originated in the study of the infinite by Georg Cantor, and it has been the source of many of the most challenging and important issues in mathematical logic. They include Cantor's theorem, the status of the Axiom of Choice, the question of the independence of the continuum hypothesis, and the modern debate on large cardinal axioms.[167]

Computability theory is the branch of mathematical logic that studies effective procedures to solve calculation problems. One of its main goals is to understand whether it is possible to solve a given problem using an algorithm. For instance, given a certain claim about the positive integers, it examines whether an algorithm can be found to determine if this claim is true. Computability theory uses various theoretical tools and models, such as Turing machines, to explore this type of issue.[168]

Computational logic

[edit]

Computational logic is the branch of logic and computer science that studies how to implement mathematical reasoning and logical formalisms using computers. This includes, for example, automatic theorem provers, which employ rules of inference to construct a proof step by step from a set of premises to the intended conclusion without human intervention.[169] Logic programming languages are designed specifically to express facts using logical formulas and to draw inferences from these facts. For example, Prolog is a logic programming language based on predicate logic.[170] Computer scientists also apply concepts from logic to problems in computing. The works of Claude Shannon were influential in this regard. He showed how Boolean logic can be used to understand and implement computer circuits.[171] This can be achieved using electronic logic gates, i.e. electronic circuits with one or more inputs and usually one output. The truth values of propositions are represented by voltage levels. In this way, logic functions can be simulated by applying the corresponding voltages to the inputs of the circuit and determining the value of the function by measuring the voltage of the output.[172]

Formal semantics of natural language

[edit]Formal semantics is a subfield of logic, linguistics, and the philosophy of language. The discipline of semantics studies the meaning of language. Formal semantics uses formal tools from the fields of symbolic logic and mathematics to give precise theories of the meaning of natural language expressions. It understands meaning usually in relation to truth conditions, i.e. it examines in which situations a sentence would be true or false. One of its central methodological assumptions is the principle of compositionality. It states that the meaning of a complex expression is determined by the meanings of its parts and how they are combined. For example, the meaning of the verb phrase "walk and sing" depends on the meanings of the individual expressions "walk" and "sing". Many theories in formal semantics rely on model theory. This means that they employ set theory to construct a model and then interpret the meanings of expression in relation to the elements in this model. For example, the term "walk" may be interpreted as the set of all individuals in the model that share the property of walking. Early influential theorists in this field were Richard Montague and Barbara Partee, who focused their analysis on the English language.[173]

Epistemology of logic

[edit]The epistemology of logic studies how one knows that an argument is valid or that a proposition is logically true.[174] This includes questions like how to justify that modus ponens is a valid rule of inference or that contradictions are false.[175] The traditionally dominant view is that this form of logical understanding belongs to knowledge a priori.[176] In this regard, it is often argued that the mind has a special faculty to examine relations between pure ideas and that this faculty is also responsible for apprehending logical truths.[177] A similar approach understands the rules of logic in terms of linguistic conventions. On this view, the laws of logic are trivial since they are true by definition: they just express the meanings of the logical vocabulary.[178]

Some theorists, like Hilary Putnam and Penelope Maddy, object to the view that logic is knowable a priori. They hold instead that logical truths depend on the empirical world. This is usually combined with the claim that the laws of logic express universal regularities found in the structural features of the world. According to this view, they may be explored by studying general patterns of the fundamental sciences. For example, it has been argued that certain insights of quantum mechanics refute the principle of distributivity in classical logic, which states that the formula is equivalent to . This claim can be used as an empirical argument for the thesis that quantum logic is the correct logical system and should replace classical logic.[179]

History

[edit]Logic was developed independently in several cultures during antiquity. One major early contributor was Aristotle, who developed term logic in his Organon and Prior Analytics.[183] He was responsible for the introduction of the hypothetical syllogism[184] and temporal modal logic.[185] Further innovations include inductive logic[186] as well as the discussion of new logical concepts such as terms, predicables, syllogisms, and propositions. Aristotelian logic was highly regarded in classical and medieval times, both in Europe and the Middle East. It remained in wide use in the West until the early 19th century.[187] It has now been superseded by later work, though many of its key insights are still present in modern systems of logic.[188]

Ibn Sina (Avicenna) was the founder of Avicennian logic, which replaced Aristotelian logic as the dominant system of logic in the Islamic world.[189] It influenced Western medieval writers such as Albertus Magnus and William of Ockham.[190] Ibn Sina wrote on the hypothetical syllogism[191] and on the propositional calculus.[192] He developed an original "temporally modalized" syllogistic theory, involving temporal logic and modal logic.[193] He also made use of inductive logic, such as his methods of agreement, difference, and concomitant variation, which are critical to the scientific method.[191] Fakhr al-Din al-Razi was another influential Muslim logician. He criticized Aristotelian syllogistics and formulated an early system of inductive logic, foreshadowing the system of inductive logic developed by John Stuart Mill.[194]

During the Middle Ages, many translations and interpretations of Aristotelian logic were made. The works of Boethius were particularly influential. Besides translating Aristotle's work into Latin, he also produced textbooks on logic.[195] Later, the works of Islamic philosophers such as Ibn Sina and Ibn Rushd (Averroes) were drawn on. This expanded the range of ancient works available to medieval Christian scholars since more Greek work was available to Muslim scholars that had been preserved in Latin commentaries. In 1323, William of Ockham's influential Summa Logicae was released. It is a comprehensive treatise on logic that discusses many basic concepts of logic and provides a systematic exposition of types of propositions and their truth conditions.[196]

In Chinese philosophy, the School of Names and Mohism were particularly influential. The School of Names focused on the use of language and on paradoxes. For example, Gongsun Long proposed the white horse paradox, which defends the thesis that a white horse is not a horse. The school of Mohism also acknowledged the importance of language for logic and tried to relate the ideas in these fields to the realm of ethics.[197]

In India, the study of logic was primarily pursued by the schools of Nyaya, Buddhism, and Jainism. It was not treated as a separate academic discipline and discussions of its topics usually happened in the context of epistemology and theories of dialogue or argumentation.[198] In Nyaya, inference is understood as a source of knowledge (pramāṇa). It follows the perception of an object and tries to arrive at conclusions, for example, about the cause of this object.[199] A similar emphasis on the relation to epistemology is also found in Buddhist and Jainist schools of logic, where inference is used to expand the knowledge gained through other sources.[200] Some of the later theories of Nyaya, belonging to the Navya-Nyāya school, resemble modern forms of logic, such as Gottlob Frege's distinction between sense and reference and his definition of number.[201]

The syllogistic logic developed by Aristotle predominated in the West until the mid-19th century, when interest in the foundations of mathematics stimulated the development of modern symbolic logic.[202] Many see Gottlob Frege's Begriffsschrift as the birthplace of modern logic. Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz's idea of a universal formal language is often considered a forerunner. Other pioneers were George Boole, who invented Boolean algebra as a mathematical system of logic, and Charles Peirce, who developed the logic of relatives. Alfred North Whitehead and Bertrand Russell, in turn, condensed many of these insights in their work Principia Mathematica. Modern logic introduced novel concepts, such as functions, quantifiers, and relational predicates. A hallmark of modern symbolic logic is its use of formal language to precisely codify its insights. In this regard, it departs from earlier logicians, who relied mainly on natural language.[203] Of particular influence was the development of first-order logic, which is usually treated as the standard system of modern logic.[204] Its analytical generality allowed the formalization of mathematics and drove the investigation of set theory. It also made Alfred Tarski's approach to model theory possible and provided the foundation of modern mathematical logic.[205]

See also

[edit]- Glossary of logic

- Outline of logic – Overview of and topical guide to logic

- Critical thinking – Analysis of facts to form a judgment

- List of logic journals

- List of logic symbols – List of symbols used to express logical relations

- List of logicians

- Logic puzzle – Puzzle deriving from the mathematics field of deduction

- Logical reasoning – Process of drawing correct inferences

- Logos – Concept in philosophy, religion, rhetoric, and psychology

- Vector logic

References

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ However, there are some forms of logic, like imperative logic, where this may not be the case.[42]

- ^ Conductive arguments present reasons in favor of a conclusion without claiming that the reasons are strong enough to decisively support the conclusion.

Citations

[edit]- ^ Velleman 2006, pp. 8, 103.

- ^ Vickers 2022.

- ^ Nunes 2011, pp. 2066–2069.

- ^ Pépin 2004, Logos; Online Etymology Staff.

- ^ Hintikka 2019, lead section, §Nature and varieties of logic.

- ^ Hintikka 2019, §Nature and varieties of logic; Haack 1978, pp. 1–10, Philosophy of logics; Schlesinger, Keren-Portnoy & Parush 2001, p. 220.

- ^ Hintikka & Sandu 2006, p. 13; Audi 1999b, Philosophy of logic; McKeon.

- ^ Blair & Johnson 2000, pp. 93–95; Craig 1996, Formal and informal logic.

- ^ Craig 1996, Formal and informal logic; Barnes 2007, p. 274; Planty-Bonjour 2012, p. 62; Rini 2010, p. 26.

- ^ MacFarlane 2017; Corkum 2015, pp. 753–767; Blair & Johnson 2000, pp. 93–95; Magnus 2005, pp. 12–14, 1.6 Formal languages.

- ^ a b McKeon; Craig 1996, Formal and informal logic.

- ^ Hintikka & Sandu 2006, p. 13.

- ^ Magnus 2005, Proofs, p. 102.

- ^ Hintikka & Sandu 2006, pp. 13–16; Makridis 2022, pp. 1–2; Runco & Pritzker 1999, p. 155.

- ^ Gómez-Torrente 2019; Magnus 2005, 1.5 Other logical notions, p. 10.

- ^ a b Hintikka & Sandu 2006, p. 16.

- ^ Honderich 2005, logic, informal; Craig 1996, Formal and informal logic; Johnson 1999, pp. 265–268.

- ^ Craig 1996, Formal languages and systems; Simpson 2008, p. 14.

- ^ Craig 1996, Formal languages and systems.

- ^ Hintikka & Sandu 2006, pp. 22–23; Magnus 2005, pp. 8–9, 1.4 Deductive validity; Johnson 1999, p. 267.

- ^ Haack 1978, pp. 1–2, 4, Philosophy of logics; Hintikka & Sandu 2006, pp. 16–17; Jacquette 2006, Introduction: Philosophy of logic today, pp. 1–12.

- ^ Haack 1978, pp. 1–2, 4, Philosophy of logics; Jacquette 2006, pp. 1–12, Introduction: Philosophy of logic today.

- ^ Haack 1978, pp. 5–7, 9, Philosophy of logics; Hintikka & Sandu 2006, pp. 31–32; Haack 1996, pp. 229–230.

- ^ Haack 1978, pp. 1–10, Philosophy of logics; Groarke 2021, lead section; 1.1 Formal and Informal Logic.

- ^ Johnson 2014, pp. 228–229.

- ^ Groarke 2021, lead section; 1. History; Audi 1999a, Informal logic; Johnson 1999, pp. 265–274.

- ^ Craig 1996, Formal and informal logic; Johnson 1999, p. 267.

- ^ Blair & Johnson 2000, pp. 93–97; Craig 1996, Formal and informal logic.

- ^ Johnson 1999, pp. 265–270; van Eemeren et al., pp. 1–45, Informal Logic.

- ^ Groarke 2021, 1.1 Formal and Informal Logic; Audi 1999a, Informal logic; Honderich 2005, logic, informal.

- ^ Blair & Johnson 2000, pp. 93–107; Groarke 2021, lead section; 1.1 Formal and Informal Logic; van Eemeren et al., p. 169.

- ^ Oaksford & Chater 2007, p. 47.

- ^ Craig 1996, Formal and informal logic; Walton 1987, pp. 2–3, 6–8, 1. A new model of argument; Engel 1982, pp. 59–92, 2. The medium of language.

- ^ Blair & Johnson 1987, pp. 147–151.

- ^ Falikowski & Mills 2022, p. 98; Weddle 2011, pp. 383–388, 36. Informal logic and the eductive-inductive distinction; Blair 2011, p. 47.

- ^ Vickers 2022; Nunes 2011, pp. 2066–2069, Logical Reasoning and Learning.

- ^ Johnson 2014, p. 181; Johnson 1999, p. 267; Blair & Johnson 1987, pp. 147–151.

- ^ a b Vleet 2010, pp. ix–x, Introduction; Dowden; Stump.

- ^ Maltby, Day & Macaskill 2007, p. 564; Dowden.

- ^ Craig 1996, Formal and informal logic; Johnson 1999, pp. 265–270.

- ^ a b Audi 1999b, Philosophy of logic; Honderich 2005, philosophical logic.

- ^ Haack 1974, p. 51.

- ^ a b c d e Audi 1999b, Philosophy of logic.

- ^ Falguera, Martínez-Vidal & Rosen 2021; Tondl 2012, p. 111.

- ^ Olkowski & Pirovolakis 2019, pp. 65–66.

- ^ Audi 1999b, Philosophy of logic; Pietroski 2021.

- ^ Audi 1999b, Philosophy of logic; Kusch 2020; Rush 2014, pp. 1–10, 189–190.

- ^ a b King 2019; Pickel 2020, pp. 2991–3006.

- ^ a b c Honderich 2005, philosophical logic.

- ^ Pickel 2020, pp. 2991–3006.

- ^ Honderich 2005, philosophical logic; Craig 1996, Philosophy of logic; Michaelson & Reimer 2019.

- ^ Michaelson & Reimer 2019.

- ^ Hintikka 2019, §Nature and varieties of logic; MacFarlane 2017.

- ^ Gómez-Torrente 2019; MacFarlane 2017; Honderich 2005, philosophical logic.

- ^ Gómez-Torrente 2019; Jago 2014, p. 41.

- ^ Magnus 2005, pp. 35–38, 3. Truth tables; Angell 1964, p. 164; Hall & O'Donnell 2000, p. 48.

- ^ Magnus 2005, pp. 35–45, 3. Truth tables; Angell 1964, p. 164.

- ^ Tarski 1994, p. 40.

- ^ a b Hintikka 2019, lead section, §Nature and varieties of logic; Audi 1999b, Philosophy of logic.

- ^ Blackburn 2008, argument; Stairs 2017, p. 343.

- ^ Copi, Cohen & Rodych 2019, p. 30.

- ^ Hintikka & Sandu 2006, p. 20; Backmann 2019, pp. 235–255; IEP Staff.

- ^ Hintikka & Sandu 2006, p. 16; Backmann 2019, pp. 235–255; IEP Staff.

- ^ Groarke 2021, 1.1 Formal and Informal Logic; Weddle 2011, pp. 383–388, 36. Informal logic and the eductive-inductive distinction; van Eemeren & Garssen 2009, p. 191.

- ^ Evans 2005, 8. Deductive Reasoning, p. 169.

- ^ McKeon.

- ^ Hintikka & Sandu 2006, pp. 13–14.

- ^ Hintikka & Sandu 2006, pp. 13–14; Blackburn 2016, rule of inference.

- ^ Blackburn 2016, rule of inference.

- ^ Dick & Müller 2017, p. 157.

- ^ Hintikka & Sandu 2006, p. 13; Backmann 2019, pp. 235–255; Douven 2021.

- ^ Hintikka & Sandu 2006, p. 14; D'Agostino & Floridi 2009, pp. 271–315.

- ^ Hintikka & Sandu 2006, p. 14; Sagüillo 2014, pp. 75–88; Hintikka 1970, pp. 135–152.

- ^ Hintikka & Sandu 2006, pp. 13–16; Backmann 2019, pp. 235–255; IEP Staff.

- ^ Rocci 2017, p. 26; Hintikka & Sandu 2006, pp. 13, 16; Douven 2021.

- ^ IEP Staff; Douven 2021; Hawthorne 2021.

- ^ IEP Staff; Hawthorne 2021; Wilbanks 2010, pp. 107–124.

- ^ a b c d Douven 2021.

- ^ Groarke 2021, 4.1 AV Criteria; Possin 2016, pp. 563–593.

- ^ Scott & Marshall 2009, Analytic induction; Houde & Camacho 2003, Induction.

- ^ a b Borchert 2006b, Induction.

- ^ a b Douven 2021; Koslowski 2017, Abductive reasoning and explanation.

- ^ a b Cummings 2010, Abduction, p. 1.

- ^ Hansen 2020; Chatfield 2017, p. 194.

- ^ Walton 1987, p. 7, 1. A new model of argument; Hansen 2020.

- ^ Hansen 2020.

- ^ Hansen 2020; Walton 1987, p. 63, 3. Logic of propositions.

- ^ Sternberg; Stone 2012, pp. 327–356.

- ^ Walton 1987, pp. 2–4, 1. A new model of argument; Dowden; Hansen 2020.

- ^ Engel 1982, pp. 59–92, 2. The medium of language; Mackie 1967; Stump.

- ^ Stump; Engel 1982, pp. 143–212, 4. Fallacies of presumption.

- ^ Stump; Mackie 1967.

- ^ a b Hintikka & Sandu 2006, p. 20.

- ^ Hintikka & Sandu 2006, p. 20; Pedemonte 2018, pp. 1–17; Hintikka 2023.

- ^ Kulik & Fridman 2017, p. 74; Cook 2009, p. 124.

- ^ Flotyński 2020, p. 39; Berlemann & Mangold 2009, p. 194.

- ^ Gensler 2006, p. xliii; Font & Jansana 2017, p. 8.

- ^ Haack 1978, pp. 1–10, Philosophy of logics; Hintikka & Sandu 2006, pp. 31–32; Jacquette 2006, pp. 1–12, Introduction: Philosophy of logic today.

- ^ Moore & Carling 1982, p. 53; Enderton 2001, pp. 12–13, Sentential Logic.

- ^ Lepore & Cumming 2012, p. 5.

- ^ Wasilewska 2018, pp. 145–146; Rathjen & Sieg 2022.

- ^ Sider 2010, pp. 34–42; Shapiro & Kouri Kissel 2022; Bimbó 2016, pp. 8–9.

- ^ Restall & Standefer 2023, p. 91; Enderton 2001, pp. 131–146, Chapter 2.5; van Dalen 1994, Chapter 1.5.

- ^ Jacquette 2006, pp. 1–12, Introduction: Philosophy of logic today; Smith 2022; Groarke.

- ^ Haack 1996, 1. 'Alternative' in 'Alternative Logic'.

- ^ Haack 1978, pp. 1–10, Philosophy of logics; Haack 1996, 1. 'Alternative' in 'Alternative Logic'; Wolf 1978, pp. 327–340.

- ^ Smith 2022; Groarke; Bobzien 2020.

- ^ a b Groarke.

- ^ Smith 2022; Magnus 2005, 2.2 Connectives.

- ^ Smith 2022; Bobzien 2020; Hintikka & Spade, Aristotle.

- ^ Westerståhl 1989, pp. 577–585.

- ^ a b Smith 2022; Groarke.

- ^ Smith 2022; Hurley 2015, 4. Categorical Syllogisms; Copi, Cohen & Rodych 2019, 6. Categorical Syllogisms.

- ^ Groarke; Hurley 2015, 4. Categorical Syllogisms; Copi, Cohen & Rodych 2019, 6. Categorical Syllogisms.

- ^ Hurley 2015, 4. Categorical Syllogisms.

- ^ Spriggs 2012, pp. 20–22.

- ^ Hintikka 2019, §Nature and varieties of logic, §Alternative logics; Hintikka & Sandu 2006, pp. 27–28; Bäck 2016, p. 317.

- ^ Shapiro & Kouri Kissel 2022.

- ^ Burgess 2009, 1. Classical logic.

- ^ Jacquette 2006, pp. 1–12, Introduction: Philosophy of logic today; Borchert 2006c, Logic, Non-Classical; Goble 2001, Introduction.

- ^ Brody 2006, pp. 535–536.

- ^ Klement 1995b.

- ^ Shapiro & Kouri Kissel 2022; Honderich 2005, philosophical logic; Michaelson & Reimer 2019.

- ^ Nolt 2021; Magnus 2005, 4 Quantified logic.

- ^ Bunnin & Yu 2009, p. 179; Garson 2023, Introduction.

- ^ Garson 2023; Sadegh-Zadeh 2015, p. 983.

- ^ Fitch 2014, p. 17.

- ^ Garson 2023; Carnielli & Pizzi 2008, p. 3; Benthem.

- ^ a b Garson 2023.

- ^ Rendsvig & Symons 2021.

- ^ Audi 1999b, Philosophy of logic; Väänänen 2021; Ketland 2005, Second Order Logic.

- ^ Audi 1999b, Philosophy of logic; Väänänen 2021; Daintith & Wright 2008, Predicate calculus.

- ^ Audi 1999b, Philosophy of logic; Ketland 2005, Second Order Logic.

- ^ Haack 1996, 1. 'Alternative' in 'Alternative Logic'; Wolf 1978, pp. 327–340.

- ^ a b Moschovakis 2022; Borchert 2006c, Logic, Non-Classical.

- ^ Borchert 2006c, Logic, Non-Classical; Bridges et al. 2023, pp. 73–74; Friend 2014, p. 101.

- ^ Sider 2010, Chapter 3.4; Gamut 1991, 5.5; Zegarelli 2010, p. 30.

- ^ Hájek 2006.

- ^ Borchert 2006c, Logic, Non-Classical; Priest, Tanaka & Weber 2018; Weber.

- ^ Priest, Tanaka & Weber 2018; Weber; Haack 1996, Introduction.

- ^ Hansen 2020; Korb 2004, pp. 41–42, 48; Ritola 2008, p. 335.

- ^ Hansen 2020; Korb 2004, pp. 43–44; Ritola 2008, p. 335.

- ^ Walton 1987, pp. 2–3, 1. A new model of argument; Ritola 2008, p. 335.

- ^ a b Walton 1987, pp. 3–4, 18–22, 1. A new model of argument.

- ^ Walton 1987, pp. 3–4, 11, 18, 1. A new model of argument; Ritola 2008, p. 335.

- ^ Hansen 2020; Walton 1987, pp. 3–4, 18–22, 3. Logic of propositions.

- ^ Ritola 2008, p. 335.

- ^ Hansen 2020; Korb 2004, pp. 43, 54–55.

- ^ a b Siegel & Biro 1997, pp. 277–292.

- ^ Hansen 2020; Korb 2004, pp. 41–70.

- ^ Mackie 1967; Siegel & Biro 1997, pp. 277–292.

- ^ Hansen 2020; Moore & Cromby 2016, p. 60.

- ^ Olsson 2018, pp. 431–442, Bayesian Epistemology; Hájek & Lin 2017, pp. 207–232; Hartmann & Sprenger 2010, pp. 609–620, Bayesian Epistemology.

- ^ Shermer 2022, p. 136.

- ^ Korb 2004, pp. 41–42, 44–46; Hájek & Lin 2017, pp. 207–232; Talbott 2016.

- ^ Hintikka 2019, §Logic and other disciplines; Haack 1978, pp. 1–10, Philosophy of logics.

- ^ Hintikka 2019, lead section, §Features and problems of logic; Gödel 1984, pp. 447–469, Russell's mathematical logic; Monk 1976, pp. 1–9, Introduction.

- ^ Jacquette 2006, pp. 1–12, Introduction: Philosophy of logic today.

- ^ Hintikka 2019, §Problems of ontology.

- ^ Jacquette 2006, pp. 1–12, Introduction: Philosophy of logic today; Burgess 2009, 1. Classical logic.

- ^ Goble 2001, Introduction; Hintikka & Sandu 2006, pp. 31–32.

- ^ Gensler 2006, pp. xliii–xliv; Sider 2010, pp. 4–6; Schagrin.

- ^ Irvine 2022.

- ^ Li 2010, p. ix; Rautenberg 2010, p. 15; Quine 1981, p. 1; Stolyar 1984, p. 2.

- ^ Stolyar 1984, pp. 3–6.

- ^ Hintikka & Spade, Gödel's incompleteness theorems; Linsky 2011, p. 4; Richardson 1998, p. 15.

- ^ Bagaria 2021; Cunningham.

- ^ Borchert 2006a, Computability Theory; Leary & Kristiansen 2015, p. 195.

- ^ Paulson 2018, pp. 1–14; Castaño 2018, p. 2; Wile, Goss & Roesner 2005, p. 447.

- ^ Clocksin & Mellish 2003, pp. 237–238, 252–255, 257, The Relation of Prolog to Logic; Daintith & Wright 2008, Logic Programming Languages.

- ^ O'Regan 2016, p. 49; Calderbank & Sloane 2001, p. 768.

- ^ Daintith & Wright 2008, Logic Gate.

- ^ Janssen & Zimmermann 2021, pp. 3–4; Partee 2016; King 2009, pp. 557–558; Aloni & Dekker 2016, pp. 22–23.

- ^ Warren 2020, 6. The Epistemology of Logic; Schechter.

- ^ Warren 2020, 6. The Epistemology of Logic.

- ^ Schechter.

- ^ Gómez-Torrente 2019.

- ^ Warren 2020, 6. The Epistemology of Logic; Gómez-Torrente 2019; Warren 2020, 1. What is Conventionalism.

- ^ Chua 2017, pp. 631–636; Wilce 2021; Putnam 1969, pp. 216–241.

- ^ Lagerlund 2018.

- ^ Spade & Panaccio 2019.

- ^ Haaparanta 2009, pp. 4–6, 1. Introduction; Hintikka & Spade, Modern logic, Logic since 1900.

- ^ Kline 1972, "A major achievement of Aristotle was the founding of the science of logic", p. 53; Łukasiewicz 1957, p. 7; Liu & Guo 2023, p. 15.

- ^ Lear 1980, p. 34.

- ^ Knuuttila 1980, p. 71; Fisher, Gabbay & Vila 2005, p. 119.

- ^ Berman 2009, p. 133.

- ^ Frede; Groarke.

- ^ Ewald 2019; Smith 2022.

- ^ Hasse 2008; Lagerlund 2018.

- ^ Washell 1973, pp. 445–450; Kneale & Kneale 1962, pp. 229, 266.

- ^ a b Goodman 2003, p. 155.

- ^ Goodman 1992, p. 188.

- ^ Hintikka & Spade, Arabic Logic.

- ^ Iqbal 2013, pp. 99–115, The Spirit of Muslim Culture.

- ^ Marenbon 2021, Introduction; 3. The Logical Text-Books; Hintikka & Spade.

- ^ Hintikka & Spade; Hasse 2008; Spade & Panaccio 2019.

- ^ Willman 2022; Rošker 2015, pp. 301–309.

- ^ Sarukkai & Chakraborty 2022, pp. 117–118.

- ^ Dasti, Lead section; 1b. Inference; Mills 2018, p. 121.

- ^ Emmanuel 2015, pp. 320–322; Vidyabhusana 1988, p. 221.

- ^ Chakrabarti 1976, pp. 554–563.

- ^ Groarke; Haaparanta 2009, pp. 3–5, 1. Introduction.

- ^ Haaparanta 2009, pp. 4–6; Hintikka & Spade, Modern logic, Logic since 1900.

- ^ Ewald 2019.

- ^ Ewald 2019; Schreiner 2021, p. 22.

Bibliography

[edit]- Aloni, Maria; Dekker, Paul (7 July 2016). The Cambridge Handbook of Formal Semantics. Cambridge University Press. pp. 22–23. ISBN 978-1-316-55273-5.

- Angell, Richard B. (1964). Reasoning and Logic. Ardent Media. p. 164. OCLC 375322.

- Audi, Robert (1999a). "Informal logic". The Cambridge Dictionary of Philosophy. Cambridge University Press. p. 435. ISBN 978-1-107-64379-6. Archived from the original on 14 April 2021. Retrieved 29 December 2021.

- Audi, Robert (1999b). "Philosophy of logic". The Cambridge Dictionary of Philosophy. Cambridge University Press. pp. 679–681. ISBN 978-1-107-64379-6. Archived from the original on 14 April 2021. Retrieved 29 December 2021.

- Backmann, Marius (1 June 2019). "Varieties of Justification—How (Not) to Solve the Problem of Induction". Acta Analytica. 34 (2): 235–255. doi:10.1007/s12136-018-0371-6. ISSN 1874-6349. S2CID 125767384.

- Bagaria, Joan (2021). "Set Theory". The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Metaphysics Research Lab, Stanford University. Retrieved 23 September 2022.

- Barnes, Jonathan (25 January 2007). Truth, etc.: Six Lectures on Ancient Logic. Clarendon Press. p. 274. ISBN 978-0-19-151574-3.

- Benthem, Johan van. "Modal Logic: Contemporary View: 1. Modal Notions and Reasoning Patterns: a First Pass". Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Retrieved 11 March 2023.

- Berlemann, Lars; Mangold, Stefan (10 July 2009). Cognitive Radio and Dynamic Spectrum Access. John Wiley & Sons. p. 194. ISBN 978-0-470-75443-6.

- Berman, Harold J. (1 July 2009). Law and Revolution, the Formation of the Western Legal Tradition. Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0-674-02085-6.

- Bimbó, Katalin (2 April 2016). J. Michael Dunn on Information Based Logics. Springer. pp. 8–9. ISBN 978-3-319-29300-4.

- Blackburn, Simon (1 January 2008). "argument". The Oxford Dictionary of Philosophy. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-954143-0. Archived from the original on 8 January 2022. Retrieved 8 January 2022.

- Blackburn, Simon (24 March 2016). "rule of inference". The Oxford Dictionary of Philosophy. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-954143-0. Archived from the original on 8 January 2022. Retrieved 8 January 2022.

- Blair, J. Anthony; Johnson, Ralph H. (1987). "The Current State of Informal Logic". Informal Logic. 9 (2): 147–151. doi:10.22329/il.v9i2.2671. Archived from the original on 30 December 2021. Retrieved 2 January 2022.

- Blair, J. Anthony; Johnson, Ralph H. (2000). "Informal Logic: An Overview". Informal Logic. 20 (2): 93–107. doi:10.22329/il.v20i2.2262. Archived from the original on 9 December 2021. Retrieved 29 December 2021.

- Blair, J. Anthony (20 October 2011). Groundwork in the Theory of Argumentation: Selected Papers of J. Anthony Blair. Springer Science & Business Media. p. 47. ISBN 978-94-007-2363-4.

- Bobzien, Susanne (2020). "Ancient Logic: 2. Aristotle". The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Metaphysics Research Lab, Stanford University. Archived from the original on 28 August 2018. Retrieved 3 January 2022.

- Borchert, Donald, ed. (2006a). "Computability Theory". Macmillan Encyclopedia of Philosophy Volume 2 (2nd ed.). Macmillan. pp. 372–390. ISBN 978-0-02-865782-0.

- Borchert, Donald (2006b). "Induction". Macmillan Encyclopedia of Philosophy Volume 4 (2nd ed.). Macmillan. pp. 635–648. ISBN 978-0-02-865784-4. Archived from the original on 12 January 2021. Retrieved 4 January 2022.

- Borchert, Donald (2006c). "Logic, Non-Classical". Macmillan Encyclopedia of Philosophy Volume 5 (2nd ed.). Macmillan. pp. 485–492. ISBN 978-0-02-865785-1. Archived from the original on 12 January 2021. Retrieved 4 January 2022.

- Bridges, Douglas; Ishihara, Hajime; Rathjen, Michael; Schwichtenberg, Helmut (30 April 2023). Handbook of Constructive Mathematics. Cambridge University Press. pp. 73–74. ISBN 978-1-316-51086-5.

- Brody, Boruch A. (2006). Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Vol. 5. Donald M. Borchert (2nd ed.). Thomson Gale/Macmillan Reference US. pp. 535–536. ISBN 978-0-02-865780-6. OCLC 61151356.

The two most important types of logical calculi are propositional (or sentential) calculi and functional (or predicate) calculi. A propositional calculus is a system containing propositional variables and connectives (some also contain propositional constants) but not individual or functional variables or constants. In the extended propositional calculus, quantifiers whose operator variables are propositional variables are added.

- Bunnin, Nicholas; Yu, Jiyuan (27 January 2009). The Blackwell Dictionary of Western Philosophy. John Wiley & Sons. p. 179. ISBN 978-1-4051-9112-8.

- Burgess, John P. (2009). "1. Classical logic". Philosophical Logic. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. pp. 1–12. ISBN 978-0-691-15633-0. Archived from the original on 16 December 2021. Retrieved 4 January 2022.

- Bäck, Allan T. (2016). Aristotle's Theory of Predication. Brill. p. 317. ISBN 978-90-04-32109-0.

- Calderbank, Robert; Sloane, Neil J. A. (April 2001). "Claude Shannon (1916–2001)". Nature. 410 (6830): 768. doi:10.1038/35071223. ISSN 1476-4687. PMID 11298432. S2CID 4402158.

- Carnielli, Walter; Pizzi, Claudio (2008). Modalities and Multimodalities. Springer Science & Business Media. p. 3. ISBN 978-1-4020-8590-1.

- Castaño, Arnaldo Pérez (23 May 2018). Practical Artificial Intelligence: Machine Learning, Bots, and Agent Solutions Using C#. Apress. p. 2. ISBN 978-1-4842-3357-3.

- Chakrabarti, Kisor Kumar (June 1976). "Some Comparisons Between Frege's Logic and Navya-Nyaya Logic". Philosophy and Phenomenological Research. 36 (4): 554–563. doi:10.2307/2106873. JSTOR 2106873.

- Chatfield, Tom (2017). Critical Thinking: Your Guide to Effective Argument, Successful Analysis and Independent Study. Sage. p. 194. ISBN 978-1-5264-1877-7.

- Chua, Eugene (2017). "An Empirical Route to Logical 'Conventionalism'". Logic, Rationality, and Interaction. Lecture Notes in Computer Science. Vol. 10455. pp. 631–636. doi:10.1007/978-3-662-55665-8_43. ISBN 978-3-662-55664-1.

- Clocksin, William F.; Mellish, Christopher S. (2003). "The Relation of Prolog to Logic". Programming in Prolog: Using the ISO Standard. Springer. pp. 237–257. doi:10.1007/978-3-642-55481-0_10. ISBN 978-3-642-55481-0.

- Cook, Roy T. (2009). Dictionary of Philosophical Logic. Edinburgh University Press. p. 124. ISBN 978-0-7486-3197-1.

- Copi, Irving M.; Cohen, Carl; Rodych, Victor (2019). Introduction to Logic. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-351-38697-5.

- Corkum, Philip (2015). "Generality and Logical Constancy". Revista Portuguesa de Filosofia. 71 (4): 753–767. doi:10.17990/rpf/2015_71_4_0753. ISSN 0870-5283. JSTOR 43744657.